1. Introduction

Skin is the largest organ of human body, which prevents from external injury and infections[

1]. Skin injury is often caused by trauma, surgery, infection, and diseases, such as diabetes. The natural healing process of skin injury is relatively slow and wound infection is often prone to occur. Thus, the discovery of bioactive components and explore its therapeutic mechanism is a hot topic of academic research[

2].

Skin injury repair and regeneration is a complex process, consisted of mainly four stages, including hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling[

3].The activation of various cells such as endothelial cells (ECs), fibroblasts, and macrophages, as well as the synchronous interaction of cytokines and growth factors, are involved[

4]. Angiogenesis is crucial in wound healing, as local injury-induced hypoxia and inflammatory factors stimulate EC proliferation and migration, gradually forming new epithelium, blood vessels, and granulation tissue. The newly formed capillary network provides oxygen, nutrients, and immune cells to the damaged tissue while facilitating the removal of metabolic waste, promoting wound healing[

5,

6,

7,

8].

Snail mucus has a long history of application in wound management. Current evidence suggests that snail mucus enhances fibroblast proliferation and migration, likely through the induction of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and other unidentified growth factors, thereby directly or indirectly accelerating wound closure[

9]. Furthermore, snail mucus-treated wounds demonstrate upregulated expression of angiogenic genes and enhanced matrix deposition, indicating its regulatory role in angiogenesis[

10] .

Our previous review on its chemicals found that snail mucus contains abundant natural collagen, allantoin, proteins, and glycosaminoglycans[

11]. Recent studies reported that the mucin and polysaccharides promoted the wound healing process via functioning as adhesive agent[

12,

13]. Dolashki.et al reported various peptides identified from snail mucus showing antimicrobial activities[

14].Despite these advances, the specific bioactive components and molecular mechanisms underlying snail mucus’s therapeutic effects remain poorly understood. Therefore, the present study aimed to screen snail mucus active peptides (SMAPs) for wound healing and explore its potential mechanism. The results will provide the basis the development of natural drugs to promote wound healing in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Snail Mucus Lyophilized Powder

Fresh adult Achatina fulica snails with a body mass of over 20 g each were provided by Qianfu Company (Jiaxing, China), repeatedly rinsed with tap and distilled water, and placed in a rotating drum to stimulate mucus secretion. The collected mucus was dissolved in ultrapure water, centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min, and filtered through a 0.45-μm aqueous membrane to remove impurities. The supernatant was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, lyophilized, and stored as a lyophilized powder.

2.2. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Snail Mucus

Lyophilized snail mucus powder (300 mg) was dissolved in 30 mL of 0.2 M disodium hydrogen phosphate-0.1 M citrate buffer (pH=6.8). Trypsin (6 mg, 2,500 U/mg activity) was added, and the mixture was incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, 10 mL of the reaction solution was heated at 100 °C for enzyme inactivation and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and then lyophilized to obtain a mixture containing snail mucus active peptides SMAP.

2.3. Screening and Synthesis of SMAP

The protein mixture of enzymatically hydrolyzed snail mucus was subjected to a standardized process of liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometry (Bruker timsTOF, USA) for proteomics studies and bioinformatics analysis.Then, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was used to annotate the function of the identified peptides. Peptides involved in the "Cell Growth and Death" regulatory pathway were selected and synthesized by Temic Biotech (Suzhou, China).The peptide was purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and verified by mass spectrometry for molecular weight consistency (molecular weight error <0.1 Da). Peptides were stored as lyophilized powder and stored at -20 ℃, named as EK-12.

2.4. Cell Culture and Proliferation Assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs,Zhong Sheng, Beijing, China) were thawed and cultured in an endothelial cell medium (ECM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were passaged at 80–90% confluence and maintained for subsequent experiments. EK-12 were dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to prepare drug solutions at concentrations of 10-3,000 μg/mL, using low (10-250 μg/mL) to high (500-3000 μg/mL) dose ranges to assess dose-dependent effects.

HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates (100 μL/well) and pre-cultured for 24 h in a 37 °C, 5% CO₂ incubator to ensure adhesion.Subsequently, the cells were then treated with SMAPs at varying concentrations or with a drug-free medium (control) for 24 h, with six replicates per group. After treatment, 10 μL of cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent was added to each well, followed by a 2-h incubation. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader to calculate cell viability.

2.5. Cell Scratch Test

HUVECs were seeded into 12-well plates at 2×10⁵ cells/well and cultured to 100% confluence. A sterile 200 μL pipette tip was used to create uniform scratches on the monolayer. After washing with PBS to remove detached cells and debris, experimental wells were treated with SMAPs at designated concentrations (1,000, 1,500,and 2,000 μg/mL), while were treated with a standard medium. Cell migration was monitored at 6, 12, and 24 h post-scratch using an inverted phase-contrast microscope. The cell migration rate was calculated as follows:

CM = cell migration rate;S₀ = initial scratch area; S = remaining scratch area at observation time.

2.6. Tube Formation Assay

Matrigel was thawed at 4 °C, diluted, and aliquoted (50 μL/well) into pre-chilled plates, avoiding bubble formation. The plates were incubated for 30–45 min at 37 °C to allow polymerization. HUVECs were trypsinized, resuspended in a medium containing SMAPs (1,500 μg/mL final concentration), and seeded onto the Matrigel-coated wells. The control groups were treated with a drug-free medium. Cells were cultured in a 37 °C, 5% CO₂ incubator, and tubular structures were imaged at 6, 12, and 24 h via microscopy. Tube network nodes were quantified using ImageJ software.

2.7. Pro-Wound Healing Assay of SMAPs

Healthy adult Kunming male mice (aged 7 weeks and weighing 30-45g) were obtained from Gema Gene Company (Suzhou,China,catered by license SYXK2024-0013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Center of Soochow University (approval no.2021-210044), and conducted per ARRIVE guidelines.

The mice were accommodated for 1 week, anesthetized, and subjected to dorsal hair removal using electric clippers and depilatory cream. The skin was disinfected with 75% ethanol, eighteen full-thickness circular wounds (1 cm diameter) were established on the dorsum in six mice ,which were randomly divided into the experimental and control groups and treated daily with 1,500 μg/mL SMAP or saline, respectively. The SMAP was fabricated a vaseline paste at 1,500 μg/mL and topically applied to mice where the control group was treated with vaseline. Wound areas were photographed on Days 0, 3, 7, 10 and 14 and quantified using ImageJ software,and the healing rate was calculated as follows:

HR=healing rate; S₀ = initial wound area; S = remaining wound area at observation time.

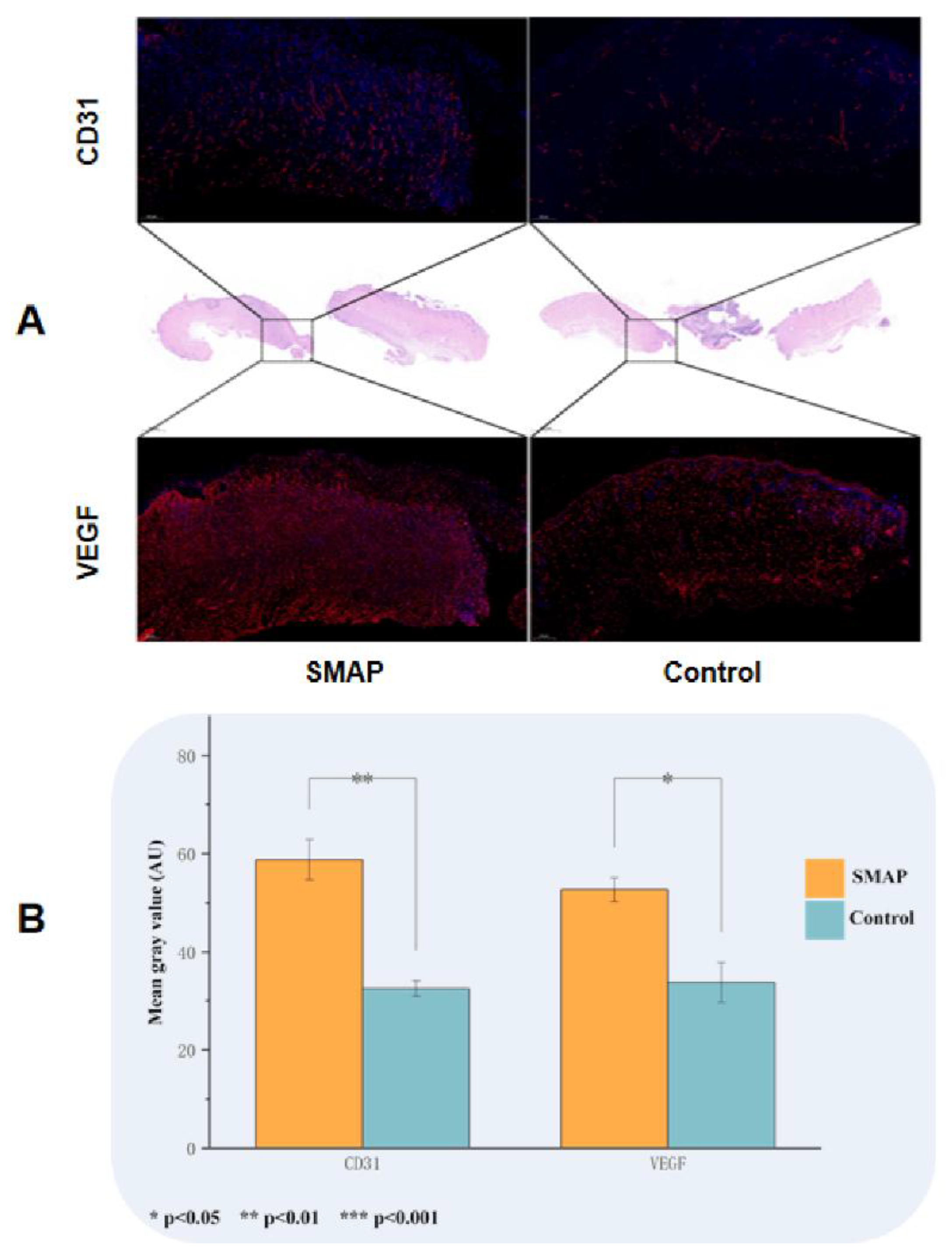

2.8. Histopathological Examination

Post-euthanasia, wound tissues were excised, rinsed in saline, and fixed in paraffin. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histological evaluation. Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (endothelial marker) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was performed to assess microvascular density and angiogenesis.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed via SPSS 27.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (normal distribution) or median (interquartile range, IQR) (non-normal distribution). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage) (n%). Group comparisons utilized independent samples t-test (continuous data) or Chi-Square test (categorical data). Graphs were generated using Origin 2024, with error bars denoting SD or SEM. Statistical significance was denoted as:*(*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Screening and Synthesis of SMAPs

The proteins were isolated from snail mucus and subjected to trypsin digestion to SMAPs. Through a standardized proteomics study process, 621 candidate peptides were identified from SMAPs and they were functionally annotated, as shown in

Figure 1A. Eighty-eight peptides were identified to be involved in basic Cellular Processes, and 12 peptides were further screened to be directly involved in the regulation of "Cell Growth and Death" pathways. Because small-molecular peptides are readily transported across the membrane and have relatively high bioavailability, a molecular weight threshold of <3,000 Da was set as the screening threshold. From the 12 target peptides, EK-12 (N-terminal sequence: EAFDDAISELEK,

Figure 1B) with a molecular weight of 1366.2Da was selected. It was synthesized by solid-phase peptides synthesis method and purified by HPLC (C18 column, acetonitrile/water gradient elution), and the purity was ≧ 98%. The sequence of synthesized EK-12 was confirmed by MS/MS analysis(

Figure 1).

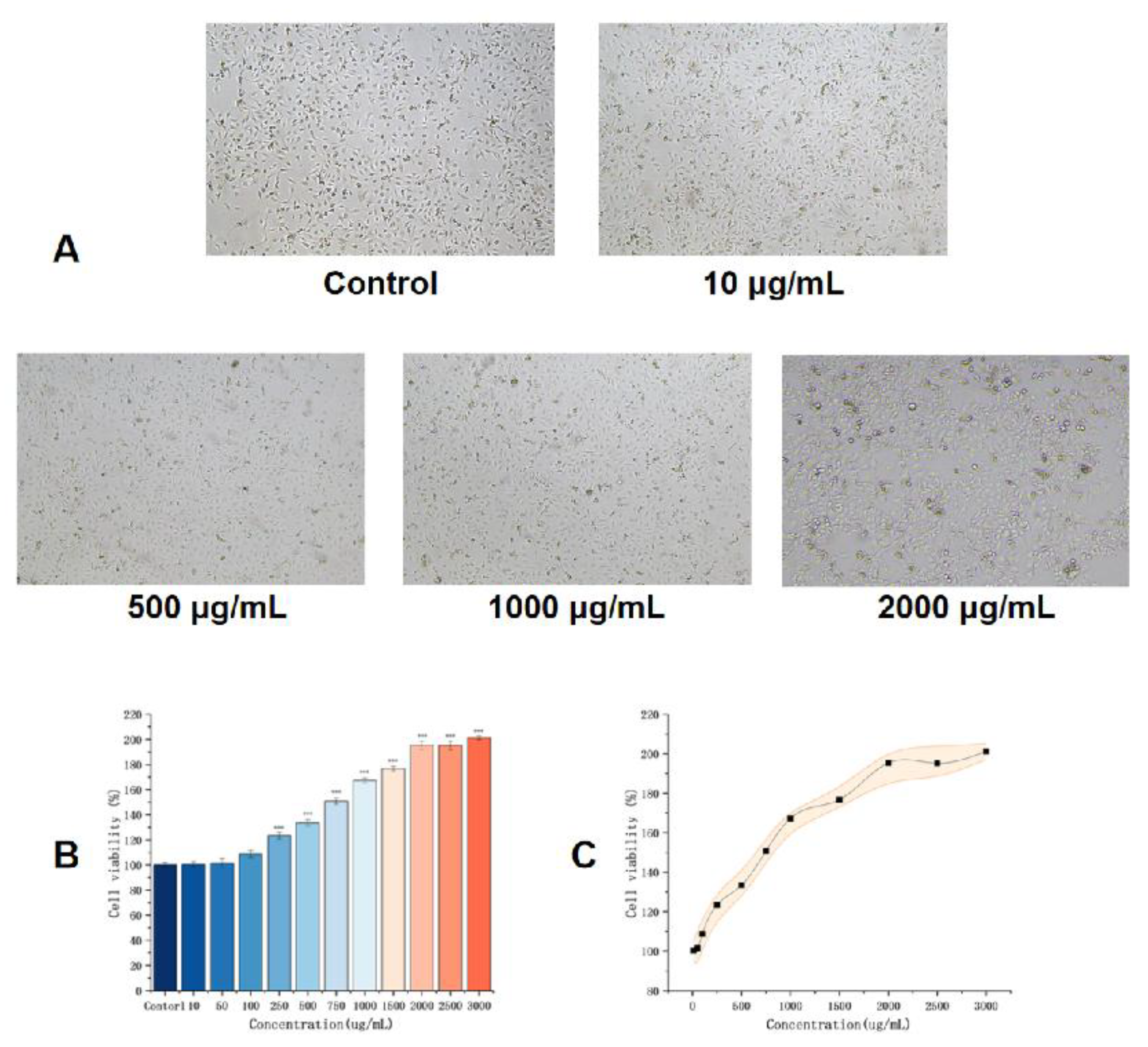

3.2. Effects of EK-12 on Cell Proliferation

Compared with that in the control group, the CCK-8 assay (absorbance at 450 nm) showed that the proliferative activity of HUVECs under each SMAP in the experimental group was significantly increased, and the difference was statistically significant (

P<0.01).This proliferative effect was concentration-dependent and significantly increased with increasing EK12 concentration (

P< 0.01). Notably, at 1,500 μg/mL EK-12, the proliferative ability stopped increasing with the concentration, and there was no statistically significant difference between 1,500 and 3,000 μg/mL (P>0.05), indicating that the proliferative effect plateaued at 1,500 μg/mL (

Figure 2).

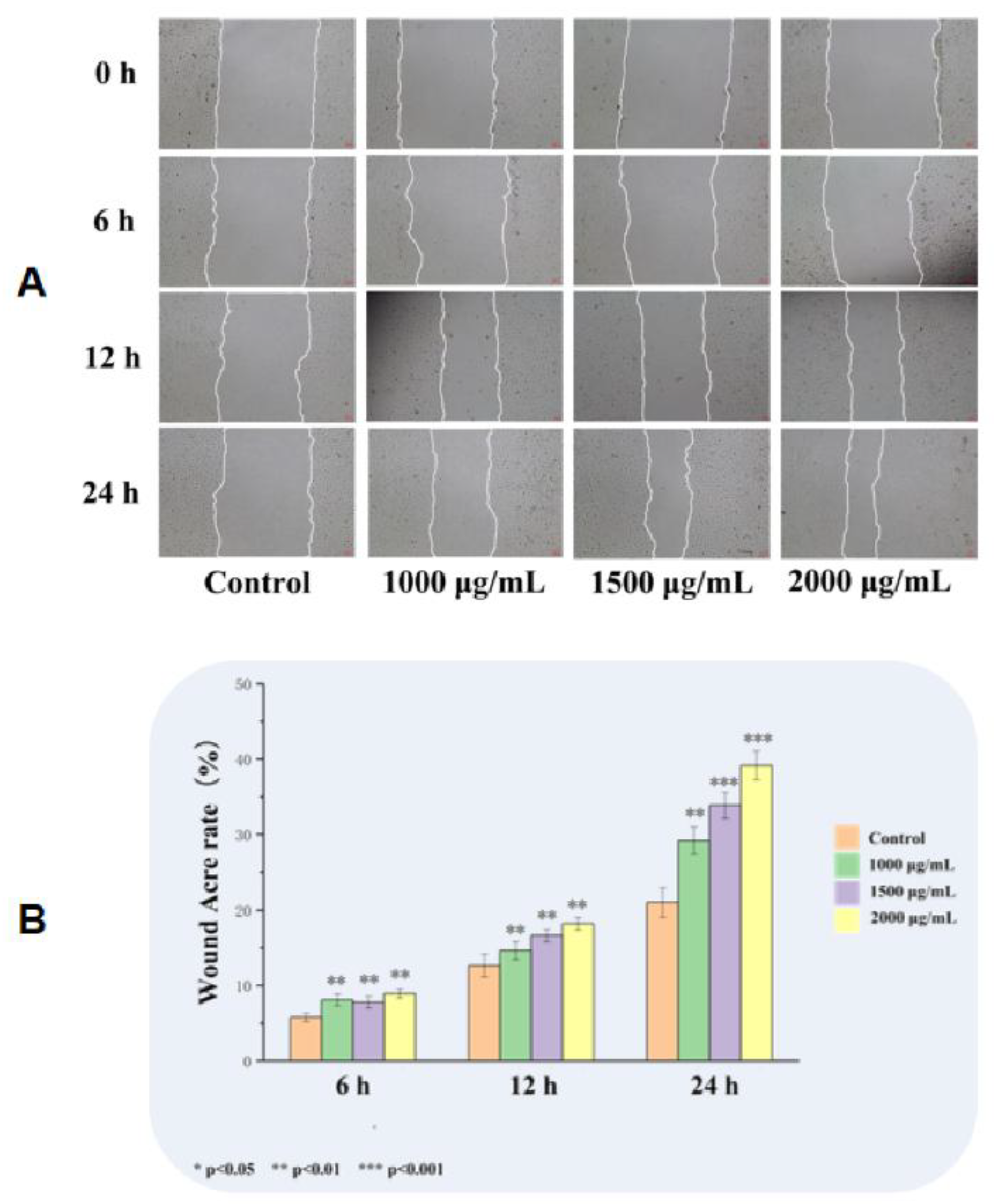

3.3. Effects of EK12 on Cell Migration

Based on CCK-8 results, EK12 at 1,000, 1,500, and 2,000 μg/mL were selected for cell scratch assays. All concentrations significantly increased HUVECs migration rates compared that in the control group at 6,12, and 24 h post-scratch (

P < 0.001), with concentrations greater than 1,500 μg/mL exerting a more significant effect; however, the 1,500 and 2,000 μg/mL groups showed no significant differences (

P> 0.05) (

Figure 3).

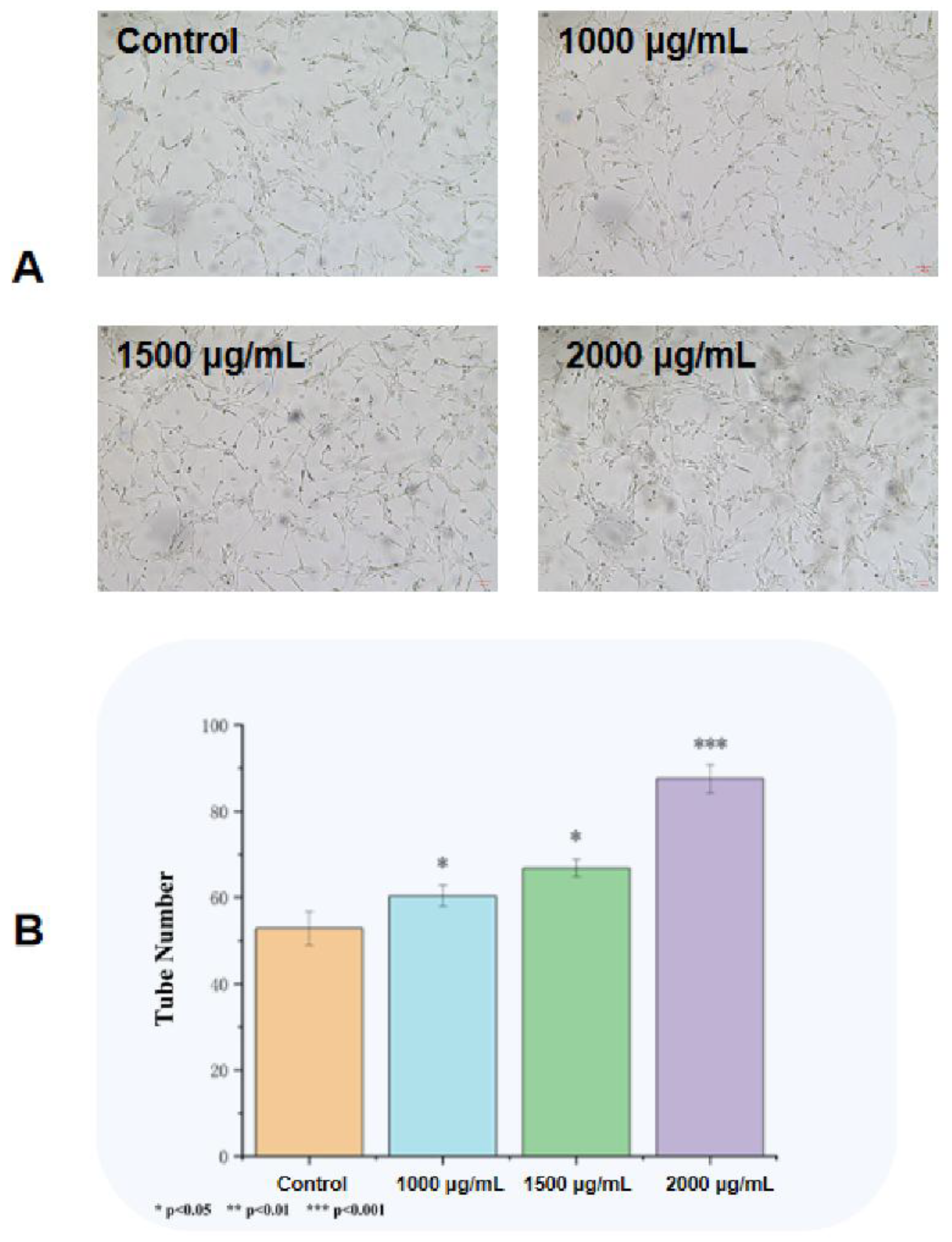

3.4. Effects on Tube Formation Capacity

Compared with the observation in saline control group, EK12 at 1,000, 1,500 and 2,000 μg/mL significantly increased the number of HUVECs forming tubular structures on Matrigel after 24 h in a concentration-dependent manner. However, there was no significant difference between the 1,500 μg/mL and 2,000 μg/mL concentration groups (

P> 0.05)(

Figure 4).

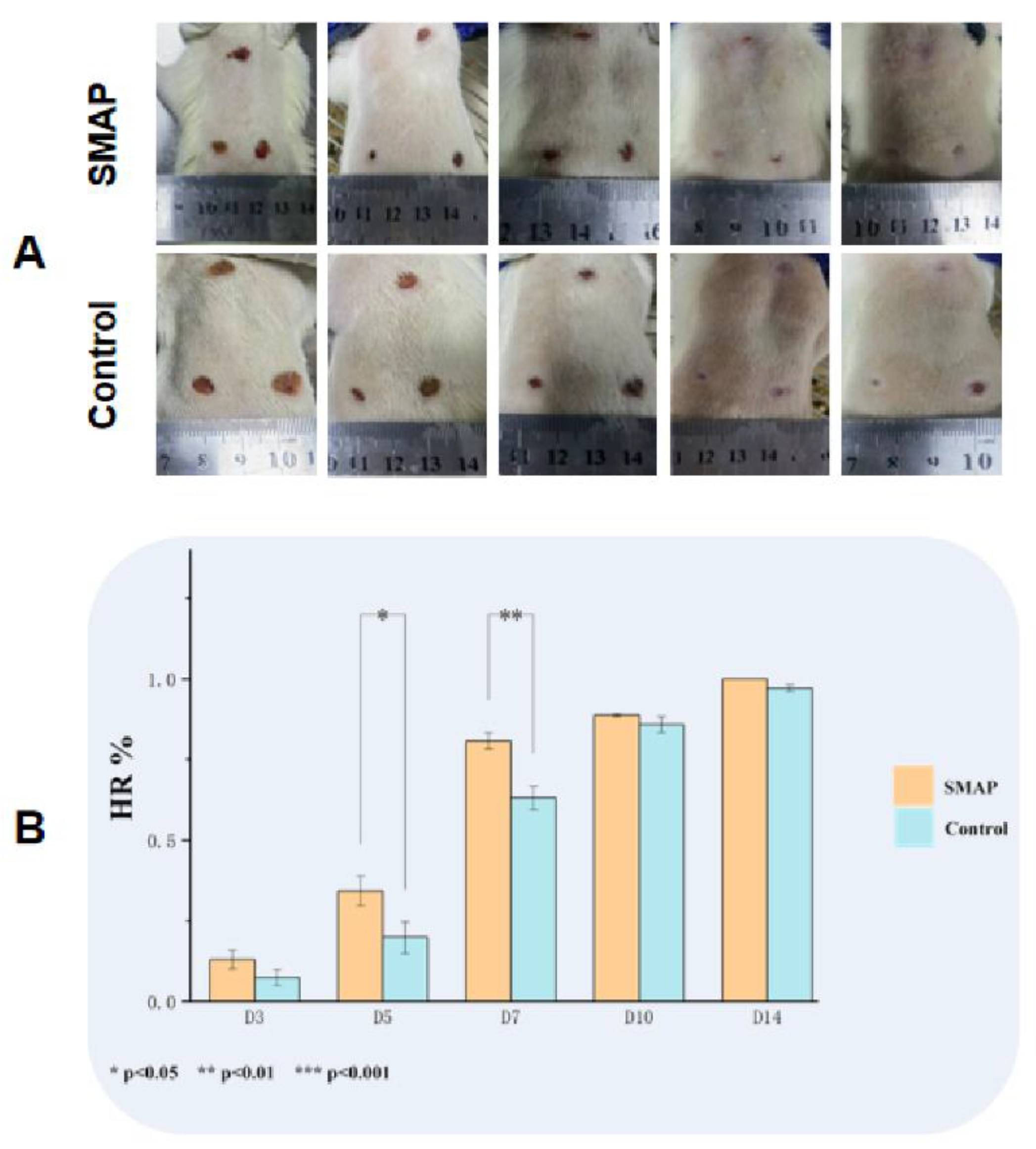

3.5. Effects on Wound Healing and Angiogenesis

The wounds in the EK12 groups healed completely within 14 days, and the healing speed was significantly faster than that in the control group (

Figure 5A-C). On day 7, the HR in the EK12 groups was significantly higher than that in the control group (

P < 0.01). Immunofluorescence analysis further revealed elevated expression of CD31 (endothelial marker) and VEGF (angiogenic factor) in SMAP-treated tissues, as evidenced by higher mean fluorescence intensity (

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01, respectively;

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

In chronic wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers, persistent inflammation, microcirculatory dysfunction, and impaired ECs activity collectively suppress angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling, significantly hindering healing[

14] . Thus, protecting ECs from apoptosis and promoting localized vascularization are pivotal strategies in wound management[

15]. Therefore, the present study used ECs for evaluating the effect of SMAP promoting wound healing.

Snail mucus has abundant active peptides that promote cell proliferation and antibacterial effects[

11,

16]. In this study, an active peptide derived from snail mucus was screened and synthesized for the first time, which significantly enhanced the proliferation, migration and tube formation of ECs. In vivo, EK-12 treatment upregulated VEGF and CD31 expression, facilitating collagen deposition and capillary network formation, which improved local blood perfusion and accelerated wound healing[

17].

Mechanistically, we hypothesized that EK-12 (EAFDDAISELEK) may activate cell surface receptors (e.g., VEGFR-2) through the synergistic action of multiple targets and trigger downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK. These pathways regulate cell cycle progression, survival, and angiogenesis, ultimately contributing to functional vascular network formation[

18,

19,

20]. These findings highlight SMAP’s potential as a therapeutic agent for ischemic ulcers. Furthermore, this study revealed that the ability of EK-12 to promote cell proliferation is concentration-dependent. Cellular proliferative and migratory activities increased with increasing EK-12 concentration. However, beyond a certain saturation concentration, cellular activity entered a plateau phase. This indicates that at this concentration, EK-12 may trigger a negative feedback mechanism regulating cell proliferation and/or reach a state of receptor binding saturation, leading to the cessation of increasing proliferative activity with additional concentration increases.

It is speculated that the snail mucus also contains various unidentified active peptide components and synergistic factors, which collaborate to promote wound healing[

13]. Future studies should focus on isolating and synthesizing other individual peptides, characterizing their biological functions, and elucidating their molecular mechanisms. These efforts may provide new insights into ischemic vascular disease treatment and regenerative medicine.

5. Conclusion

The present study has screened a snail mucus derived peptide, EK-12. The EK-12 was synthesized and its sequence was confirmed via MS/MS analysis which is EAFDDAISELEK. EK-12 significantly promoted endothelial cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and capillary network formation. EK-12 treatment had accelerated wound healing process on mice. The mechanism of EK-12 promoted wound healing was probably through multiple signaling pathways. These findings provide a scientific foundation for developing snail mucus-based therapeutics and offer a new approach to managing chronic wounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhang.X,Li.D and Zhu.J; methodology,Li.G and ZHu.K;software,Shi.Y,and H.B; validation, Z.X, and L.D.; formal analysis, H.X. and S.Y.; investigation, L.G.; resources,L.G. and Z.K.; data curation,L.G.and S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.; writing- review and editing, L.G. and Z.J.; visualization, H.X.; supervision, L.D.; project administration, Z.X.and L.D.; funding acquisition,Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Suzhou Science and Technology Bureau’s Science and Technology Program Fund (SZM2021008) ,and supported by the Gusu Talent Program of Suzhou Health Commission (GSWS2022118),and Healthcare Innovation Research Program (CXYJ2024B08).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional ethics review committee of the Medical Center of Soochow University (approval code: 2021-210044; approval date: 19 August 2021).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xu,C.;Wang,F.;Guan,S.;Wang, L. β-Glucans obtained from fungus for wound healing: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 327, 121662. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Yao, Z.; Gu, T.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, D. Study of the ability of polysaccharides isolated from Zizania latifolia to promote wound healing in mice via in vitro screening and in vivo evaluation. Food Chem 2025, 464 (Pt 3), 141810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian Dehkordi, A.; Mirahmadi Babaheydari, F.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Raeisi Dehkordi, S. Skin tissue engineering: Wound healing based on stem-cell-based therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshikazu, K.; Yuko, I. Molecular pathology of wound healing. Forensic Sci Int 2010, 15, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Teng, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, A. Modulation of macrophages by a phillyrin-loaded thermosensitive hydrogel promotes skin wound healing in mice. Cytokine 2024, 177, 156556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Sun, X.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.W.; Fu, X.; Leong, K.W. Advanced drug delivery systems and artificial skin grafts for skin wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 146, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, H.; Sorg, C.G.G. Skin wound healing: Of players, patterns, and processes. Eur Surg Res 2023, 64, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, S.; Grose, R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev 2003, 83, 835–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Gallorini, M.; Feghali, N.; Sampò, S.; Cataldi, A.; Zara, S. Snail slime extracted by a cruelty free method preserves viability and controls inflammation occurrence: A focus on fibroblasts. Molecules 2023, 28, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Deng, T.; Luo, L.; Lin, L.; Yang, L.; Tian, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wu, M. Bionic sulfated glycosaminoglycan-based hydrogel inspired by snail mucus promotes diabetic chronic wound healing via regulating macrophage polarization. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 281, 135708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, J.; Gu, T.; Ain, N.U.; Zhang, X.; Li, D. Extraction, structure, pharmacological activities and applications of polysaccharides and proteins isolated from snail mucus. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 258, 128878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, M.; Cerullo, A. R.; Parziale, J.; Achrak, E.; Sultana, S.; Ferd, J.; Samad, S.; Deng, W.; Braunschweig, A. B.; Holford, M. Advancing Discovery of Snail Mucins Function and Application. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, Volume 9 - 2021, Mini Review. [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Gao, D.; Song, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, L.; Tao, M.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, L.; Luo, L.; Zhou, A.; et al. A natural biological adhesive from snail mucus for wound repair. Nat Commun 2023, 14(1), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolashki, A.; Velkova, L.; Daskalova, E.; Zheleva, N.; Topalova, Y.; Atanasov, V.; Voelter, W.; Dolashka, P. Antimicrobial Activities of Different Fractions from Mucus of the Garden Snail Cornu aspersum. Biomedicines 2020, 8 (9). [CrossRef]

- Dasari, N.; Jiang, A.; Skochdopole, A.; Chung, J.; Reece, E.M.; Vorstenbosch, J.; Winocour, S. Updates in diabetic wound healing, inflammation, and scarring. Semin Plast Surg 2021, 35, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Cai, H.A.; Zhang, M.S.; Liao, R.Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, F.D. Ginsenoside Rg1 promoted the wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers via miR-489-3p/Sirt1 axis. J Pharmacol Sci 2021, 147, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Tian, Y.; Guo, R.; Shi, J.; Kwak, K.J.; Tong, Y.; Estania, A.P.; Hsu, W.H.; Liu, Y.; Hu, S.; et al. Extracellular vesicle-mediated VEGF-A mRNA delivery rescues ischaemic injury with low immunogenicity. Eur Heart J 2025, 46, 1662–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Huang, J.; Shi, J.; Shi, L.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, H. Ruyi Jinhuang Powder accelerated diabetic ulcer wound healing by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway of fibroblasts in vivo and in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol 2022, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, X.; Wang, F.; Tang, W.; Liu, Y.; Fu, L.; Liang, F.; Mo, Z. Inhibition of microRNA-139-5p improves fibroblasts viability and enhances wound repair in diabetic rats through AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun). Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2025, 18, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhang, T.; Cui, W.; Mao, C.; Xiao, D.; Lin, Y. Tetrahedral framework nucleic acids promote scarless healing of cutaneous wounds via the AKT-signaling pathway. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).