1. Introduction

Mangrove forests are among the world’s most critical ecosystems, especially in tropical and subtropical regions [

1]. Located at the interface between land and sea, mangroves provide vital ecosystem services such as coastal protection, biodiversity support, and carbon sequestration [

2,

3]. Their dense root systems help prevent erosion, mitigate storm surges, and serve as a frontline defense against sea-level rise and climate change impacts [

4]. Mangroves are also key habitats for numerous marine and terrestrial species. Their structural complexity offers nursery grounds for fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and shelter for birds and reptiles [

5]. This biodiversity supports coastal livelihoods and contributes to food security and local economies.

Recently, mangroves’ role in global climate mitigation has gained increased attention. Mangrove forests can store up to four times more carbon than other tropical forests [

6], with a significant portion concentrated in their biomass. Indonesia, as one of the world’s largest mangrove holders, stores around 3.14 billion metric tons of carbon in its mangrove ecosystems, making it a critical player in global climate strategies [

7]. Despite their ecological and economic value, mangroves are under threat globally. From 2000 to 2016, about 62% of global mangrove forests were lost, with Indonesia contributing a significant share of that decline [

8]. Key drivers include land conversion, aquaculture expansion, and unsustainable agriculture. Conservation and restoration have thus become urgent priorities where conservation and restoration have thus become urgent priorities [

9].

Effective conservation requires accurate and timely monitoring. Traditional methods such as field surveys and manual image interpretation are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and limited in scale [

10]. These limitations are especially problematic in vast mangrove regions like Indonesia [

11]. Recent advances in remote sensing and geospatial technologies have opened new possibilities for efficient and large-scale mangrove monitoring. High-resolution satellite imagery combined with machine learning (ML) techniques enables automated, scalable, and accurate analysis of mangrove extent and biomass [

12]. For example, [

13] demonstrated the use of satellite imagery to track mangrove cover changes in Peleng Island, Central Sulawesi, providing a solid foundation for conservation decisions.

One significant mangrove area in Indonesia is Sembilang National Park, South Sumatra. Despite its importance, this ecosystem has suffered major degradation. Between 2009 and 2017, primary mangrove forest area in the park decreased from 83,447 to 70,263 hectares—a loss of 13,184 hectares. This decline is driven by land use change, illegal logging, aquaculture, agriculture, and natural disturbances such as fires [

14] [

15].

This degradation contributes to biodiversity loss and reduces ecosystem services such as carbon storage and coastal protection [

16]. Regionally, Southeast Asia faces similar threats, often due to insufficient environmental enforcement[

17]. These challenges highlight the need for improved monitoring systems in protected areas like Sembilang.

Key issues in current mangrove monitoring include Low efficiency – Manual mapping methods are slow and resource-heavy, making it difficult to keep up with rapid land cover changes [

10], Limited accuracy – Manual interpretation can vary between analysts and is often affected by image resolution and coverage [

12] and Data integration challenges – Integrating multitemporal satellite data is difficult due to varying resolutions, cloud cover, and inconsistent vegetation index performance [

18], [

19], [

20]. To address these issues, this study proposes the development of a geospatial intelligence dashboard for automated mangrove mapping and monitoring using satellite data and machine learning algorithms. Prior research shows that machine learning, particularly Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), achieves high classification accuracy [

21,

22]. For instance, mapping mangroves in Cambodia with Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 using RF achieved over 90% accuracy.

Moreover,[

23] explored ML-based mangrove classification using combined optical and radar data in Guyana. Their results showed that combining Sentinel-1 (radar) with Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 (optical) achieved the highest overall accuracy (up to 95%). This study utilizes Random Forest (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) due to their strengths in analyzing high-dimensional remote sensing data. RF handles complex datasets and allows for feature importance ranking, making it ideal for selecting key vegetation indices like NDVI [

24,

25]. XGBoost, known for its predictive power and robustness, has been applied to estimate mangrove biomass under varying climate conditions [

12,

26]. The combination of satellite imagery and ML techniques enables accurate biomass estimation and carbon stock assessment, as demonstrated by [

27]. Additionally, multi-temporal data enhances the capability of monitoring change over time, which is vital for dynamic ecosystems like mangroves.

This research aims to develop an Open Sources-based interactive dashboard for mangrove monitoring in Sembilang National Park from 2019 to 2023. It uses Sentinel-2 and GEDI data accessed through Google Earth Engine and compares RF and XGBoost algorithms for automated classification and biomass estimation. The dashboard will visualize mangrove distribution, biomass levels, and land cover changes, supporting data-driven conservation planning. By integrating high-resolution data, machine learning, and interactive visualization tools, this study contributes a novel approach for improving mangrove monitoring efficiency, accuracy and accessibility, especially in resource-constrained environments like Indonesia's coastal zones.

2. Machine Learning and Remote Sensing for Mangrove Mapping and Monitoring

The integration of machine learning (ML) and remote sensing has significantly transformed how Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) is estimated in mangrove ecosystems. Traditional biomass assessments, often conducted through field measurements, provide valuable localized data but are generally constrained by their labor-intensive nature, high costs, and limited spatial coverage, especially in remote or extensive mangrove areas. With increasing urgency to monitor mangroves for climate mitigation and conservation, scalable, accurate, and efficient solutions are required. Remote sensing technologies, coupled with advanced ML algorithms, have become essential tools to fill this gap.

A broad literature review highlights numerous successful implementations of ML-based remote sensing methods for mangrove AGB mapping across various regions. These studies utilize a range of satellite platforms—including Sentinel-1 (radar), Sentinel-2 (optical), ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 (L-band SAR), and GEDI (LiDAR)—in combination with machine learning models such as Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN).

One significant example is the work of [

28] who mapped coastal mangrove forests across West Africa using an ensemble of ML algorithms (RF, GBM, and neural networks) with preprocessed Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data. Their study demonstrated the efficacy of ensemble models in capturing the heterogeneity of mangrove environments, especially when cross-validation and high-resolution training data are applied.

In another global-scale study, [

29] used Random Forest regression to estimate global mangrove AGB by combining field measurements, GLAS LiDAR data, vegetation indices (e.g., EVI), and topographic and climatic parameters. This work contributed to the development of a global 250-meter resolution mangrove AGB map, establishing a benchmark for future biomass modeling efforts. The fusion of GEDI LiDAR data with multi-source satellite observations has also shown promising results. For instance, [

30] fused GEDI with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery, digital elevation models, and land cover data to produce wall-to-wall AGB density maps for large areas in Australia and the United States. The study used gradient boosting with Bayesian optimization to fine-tune model parameters, significantly enhancing predictive accuracy.

In Southeast Asia, studies have emphasized regional applications of these techniques. [

12] employed XGBoost for AGB estimation in the Can Gio Biosphere Reserve in Vietnam. This was one of the first studies to use fused Sentinel-2 and ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 data with the XGBoost regression algorithm. The researchers evaluated model performance against alternative algorithms such as GBR, GPR, RF, and SVR, and achieved high levels of accuracy through careful feature engineering and model calibration. [

31] applied a Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) optimized with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to estimate mangrove AGB in the Beibu Gulf, China. The method outperformed other algorithms, including RF and XGBoost, by selecting optimal predictor combinations and maximizing generalization over a large validation dataset.

On the national scale, [

32] combined Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery with Suriname's national forest inventory data to map mangrove species and estimate biomass using RF and SVR. Their method successfully scaled biomass estimation efforts beyond local studies to broader national applications—critical for national reporting and climate commitments. In India, [

33] utilized multi-temporal Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data with an ensemble of RF, GBM, and XGBoost to estimate AGB in carbon-rich mangrove zones. Their analysis tested both date-specific and aggregated metrics, confirming the advantages of using time-series data for biomass monitoring in dynamic ecosystems. Further extending ML applications, [

23] integrated SAR and optical data with RF classifiers in Guyana to enhance coastal mangrove monitoring. Their study confirmed that combining radar and optical data significantly improves classification accuracy over single-data approaches [

34] developed models for tracking mangrove biomass change on Qi'ao Island, South China, using WorldView-2 imagery and digital surface models. Their Random Forest-based models revealed a 71.11% increase in biomass from 2010 to 2016, validating the importance of long-term, high-resolution imagery in capturing mangrove dynamics.

Several methodologies also demonstrate the effectiveness of Google Earth Engine (GEE) as a platform for scalable ML-based mangrove analysis. [

28] for example, evaluated RF and CART models in West Africa using Sentinel-2 data and GEE, showing consistent performance across multiple test iterations. Similarly, [

35] used RF on GEE with Sentinel data to achieve classification accuracy exceeding 93%, emphasizing the accessibility and repeatability of cloud-based processing. Finally, [

36] improved forest AGB estimation by integrating multi-sensor L-band and C-band SAR data with multi-temporal GEDI LiDAR. Their RF model utilized more than 21,000 GEDI footprints and kriging interpolation of canopy height, demonstrating that the synergy of SAR and LiDAR can significantly enhance AGB retrieval in dense tropical forests.

For Indonesia specifically, where mangrove degradation poses a major threat to carbon stocks and coastal resilience, the application of these technologies represents a critical opportunity. The insights drawn from these studies guide future efforts in implementing machine learning-driven biomass mapping at both national and sub-national levels. Leveraging platforms like Google Earth Engine and combining satellite data with field validation can offer robust, efficient, and actionable information to support sustainable mangrove ecosystem management. [

37] Mapped mangrove above-ground carbon in Komodo National Park, Indonesia, using machine learning models (RF, SVM, and XGBoost) integrated with Sentinel-1A, Sentinel-2B, and DEM data. Their approach combined field data with satellite-derived features, demonstrating the potential of hybrid modeling in complex tropical landscapes [

38] explored the use of Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF) classifiers for mangrove forest mapping in Sembilang National Park. Using Landsat-7 and Landsat-8 imagery, they calculated indices such as NDMI and NDSI, confirming the suitability of RF for classifying mangrove cover with high reliability in coastal regions. [

27]. conducted a study in Indonesia utilizing a stacked ensemble of ML models (Deep Learning, RF, GLM, XGBoost, GBM) for estimating mangrove species abundance using Landsat data. The use of 20-fold cross-validation and ensemble blending helped improve model generalizability and reliability, especially for carbon stock estimation in the context of carbon trading

Taken together, these studies show a strong global and regional trend toward adopting machine learning and remote sensing as the standard approach for mangrove AGB mapping. The fusion of diverse datasets—optical, radar, and LiDAR—combined with advanced ML techniques like XGBoost and ensemble modeling, has consistently delivered high-accuracy and scalable biomass estimates. Such methods are increasingly important for supporting carbon accounting, REDD+ initiatives, conservation planning, and climate adaptation strategies.

3. Methodology

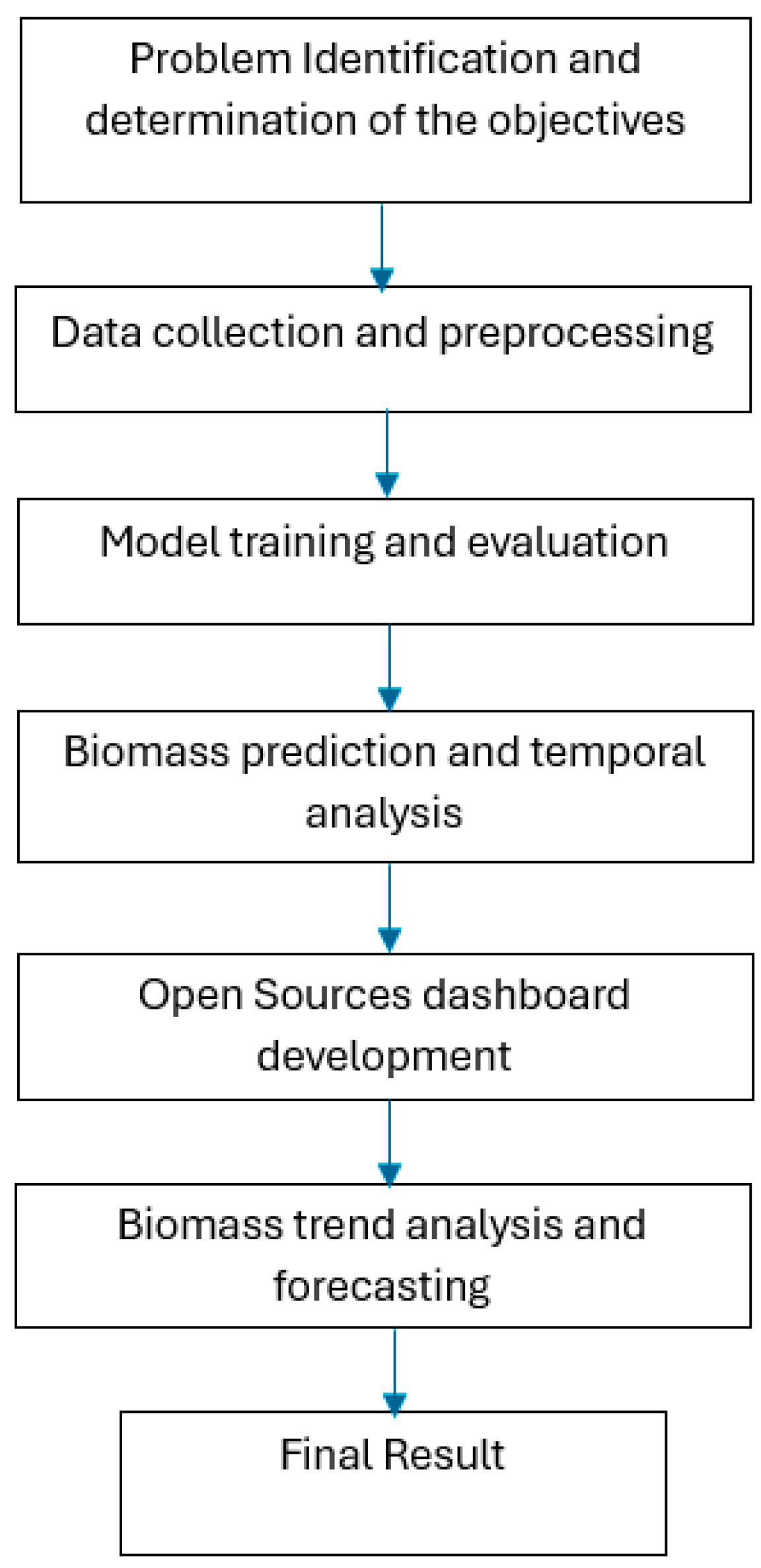

This study integrates remote sensing and machine learning (ML) techniques to develop an automated system for mapping and monitoring above-ground biomass (AGB) in mangrove forests. The research focuses on the Sembilang National Park in South Sumatra, Indonesia, over the period of 2019–2023. The methodology encompasses six main stages: (1) data collection and preprocessing, (2) model training and evaluation, (3) biomass prediction and temporal analysis, (4) Open Sources dashboard development, and (5) biomass trend analysis and forecasting.

Figure 1.

The Stages of mangrove monitoring using machine learning and Remote Sensing Data.

Figure 1.

The Stages of mangrove monitoring using machine learning and Remote Sensing Data.

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

Sentinel-2 imagery was used to derive spectral information relevant for mangrove vegetation analysis, such as NDMI and MNDWI indices. Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) data was used as the reference for estimating above-ground biomass, providing lidar-based structural information. All data acquisition and preprocessing were conducted using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. The workflow included: Region of Interest (ROI) definition: The Sembilang National Park was geographically delineated to define the analysis area. Image filtering: Sentinel-2 collections were filtered based on date range and cloud cover score. Median composites were generated to obtain cloud-free imagery for each target year and NDMI and MNDWI indices were computed to enhance mangrove classification. Mangrove cover classification with thresholding techniques were applied to identify mangrove areas, and data integration and Sentinel-2 imagery and GEDI biomass data were spatially and temporally aligned. The data were exported in two formats: GeoTIFF for spatial visualization CSV for training machine learning models.

3.2. Machine Learning Model Development

Two robust regression-based ML algorithms Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting (GB) were selected. Data were split into training (91%) and testing (9%) sets. For both RF and GB, models were trained using key features extracted from the satellite data, including spectral bands and vegetation indices. Key parameters include the number of trees (n_estimators) and maximum depth (max_depth) have been used as RF model parameter and the number of trees, learning rate, and depth as parameter in GB. Feature Importance Analysis After training, each model underwent feature importance analysis to assess the relative contribution of each input feature to the AGB prediction.

3.3. Model Evaluation and Biomass Prediction

The models were evaluated using R² score (coefficient of determination) to quantify the fit between predicted and actual biomass values. Scatter plots used to visualize prediction accuracy against GEDI reference values. Annual Biomass Mapping: Trained models were applied to the Sentinel-2 composites for each year (2019–2023). The result was a set of annual AGB maps, providing insight into spatial and temporal variations in mangrove biomass.

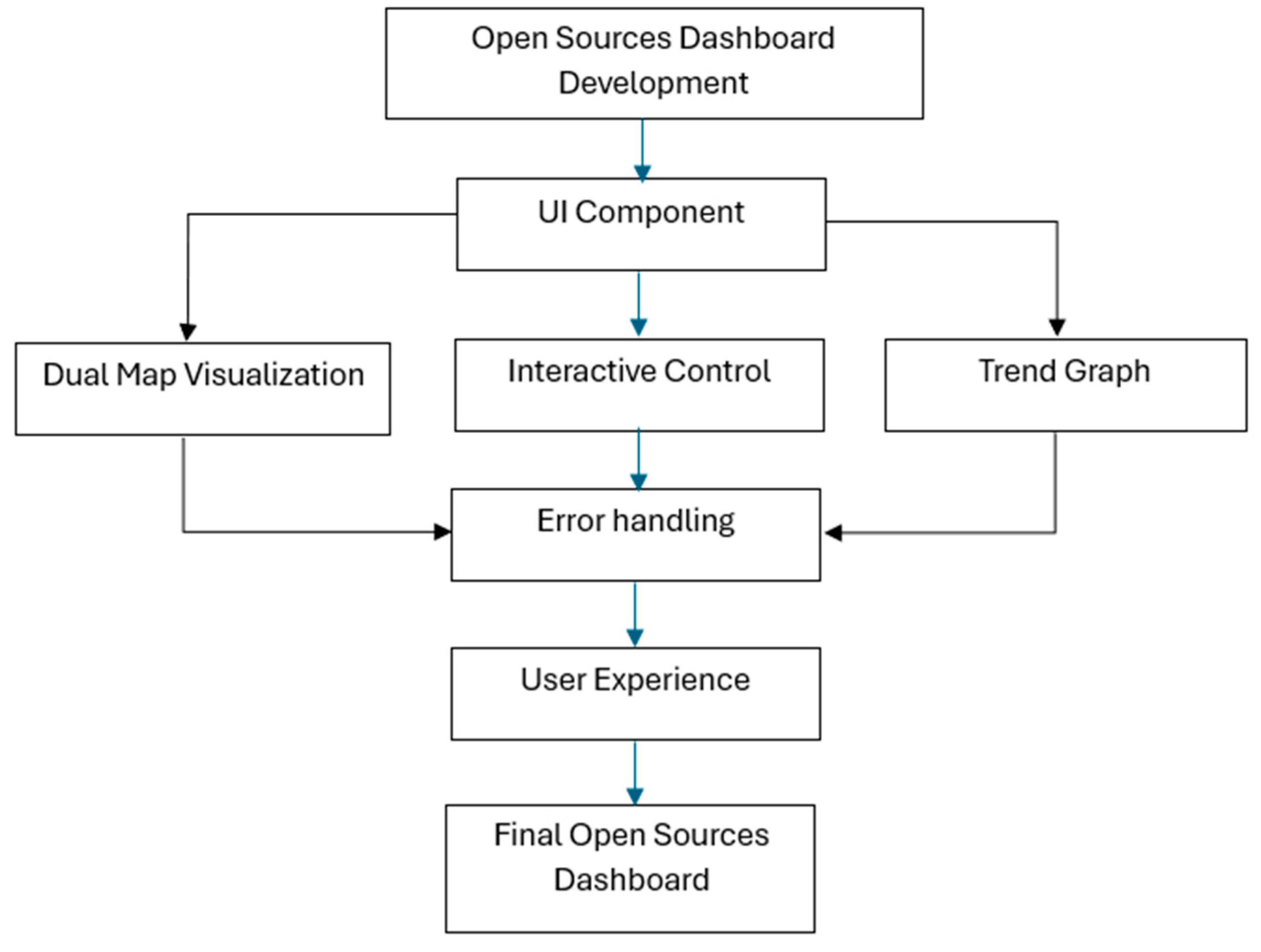

3.4. Open Sources Dashboard Development

A user-friendly web-based dashboard was developed using Streamlit, aimed at supporting decision-making for mangrove monitoring and conservation. Development Process of the dashboard followed the waterfall software development life cycle (SDLC) model. The model including problem identification (Monitoring mangrove dynamics in Sembilang National Park), requirement analysis and system design data flow diagrams (DFDs) and wireframes (via Figma) were created), implementation (The system was coded using Python, integrating the trained ML models), and testing (Functionality was tested using black box testing, and evaluation was based on Shneiderman’s 8 Golden Rules). The dashboard includes Dual Map View (Side-by-side maps for comparing different years using Folium), Interactive Controls (Sidebar widgets for selecting year, parameters, and map layers), Trend Graphs (Temporal visualizations of biomass change using Plotly), and Download Options (Export of GeoTIFF and CSV outputs, including AGB, mangrove extent, scatter plot data, and 2024 predictions).

3.5. Biomass Trend Analysis and Forecasting

To extend the utility of the system, a prediction module was implemented. Two analysis layers were integrated: ML-based biomass estimation using RF and GB models Linear regression-based trend analysis to forecast future conditions. Analysis components include Biomass Calculation (aggregates total AGB values for each year), Area Change Detection (Quantifies changes in mangrove extent across the study period), and Forecasting for Year 2024 (Projects AGB and mangrove area using linear regression based on past trends). For the output visualization AGB include trend plots, Percentage change in mangrove cover, Forecasted biomass maps has been implemented.

Figure 2.

The Stages of user-friendly web-based dashboard using Streamlit.

Figure 2.

The Stages of user-friendly web-based dashboard using Streamlit.

4. Result

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

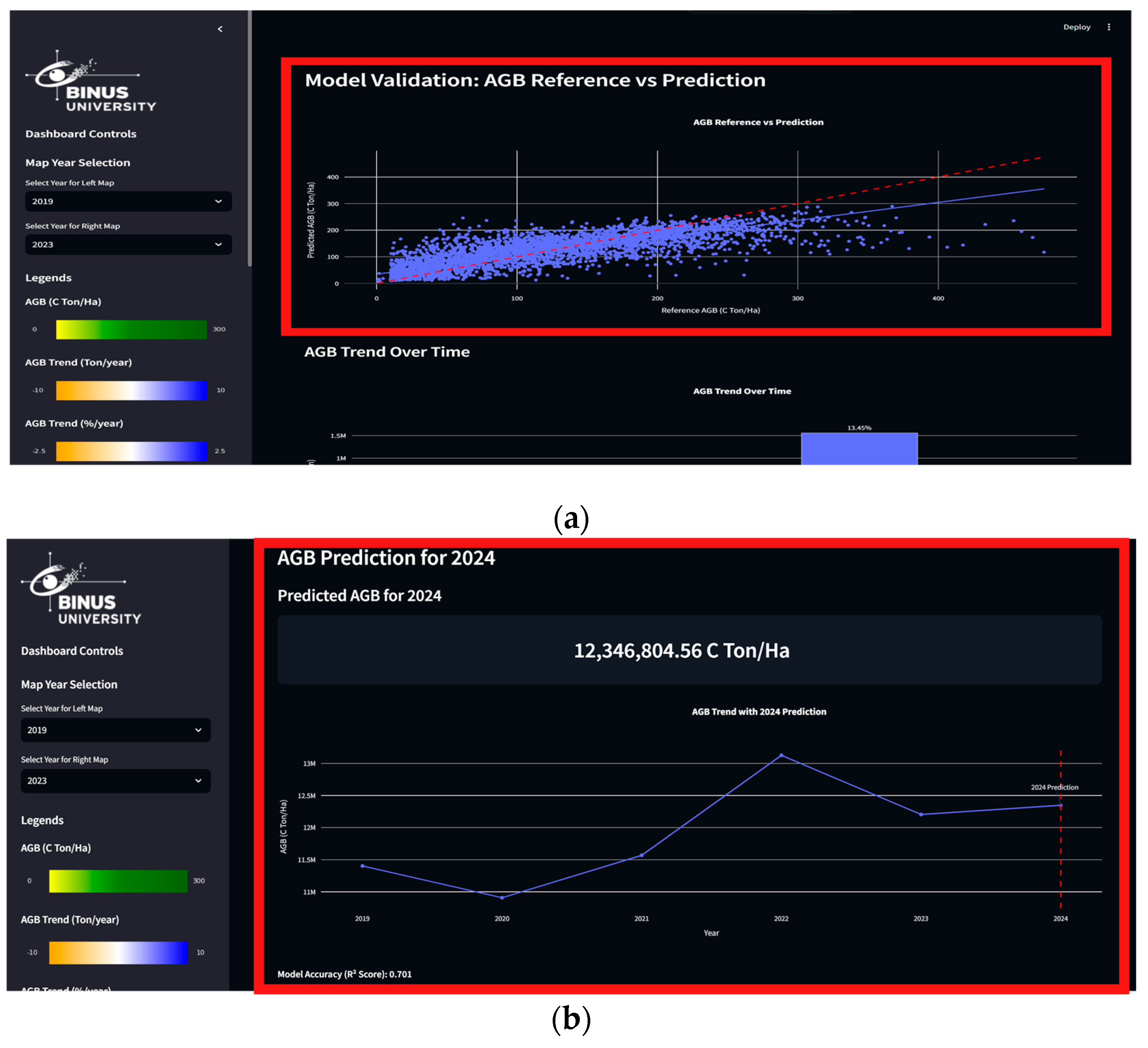

4.1. Model Training and Evaluation Result

This study developed a mangrove biomass estimation model using two machine learning algorithms: Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting (GB). The dataset was stratified and split into training (90%), testing (9%), and validation (1%) sets. Random Forest, configured with 50 decision trees, was optimized for maximum depth and minimum samples per leaf. Gradient Boosting used 300 trees with shrinkage (0.1), sampling rate (0.85), and max nodes (35). Both models were set to regression mode to predict continuous biomass values. RF outperformed GB with an R² score of 0.701 vs. 0.601, highlighting its robustness and better generalization.

Table 1.

Key Gradient Boosting Parameters.

Table 1.

Key Gradient Boosting Parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

| numberOfTrees |

300 |

Builds a robust ensemble |

| shrinkage |

0.1 |

Ensures smoother learning steps |

| samplingRate |

0.85 |

Improves prediction stability |

| maxNodes |

35 |

Captures complex data patterns |

Table 2.

R2 Score Comparison

Table 2.

R2 Score Comparison

| Algorithm |

R2 Score |

| Random Forest |

0.701 |

| Gradient Boosting |

0.601 |

4.2. Biomass Prediction and Temporal Analysis

The prediction system uses a linear regression approach to project biomass values for 2024. The prediction model considers the historical trend of the 2019-2023 data, with the implementation including the calculation of confidence intervals to provide a realistic prediction range. Prediction results are displayed in the form of easy-to-read metrics and trend graphs showing future projections.

Figure 3.

Visualization of Prediction System Using Line Chart.

Figure 3.

Visualization of Prediction System Using Line Chart.

Visualization of prediction results integrates historical data with predicted values, using dotted lines to distinguish between actual and projected data. The metrics display shows the predicted values in an easy-to-read format, with a calculation of the percentage change from last year to give context to the projections.

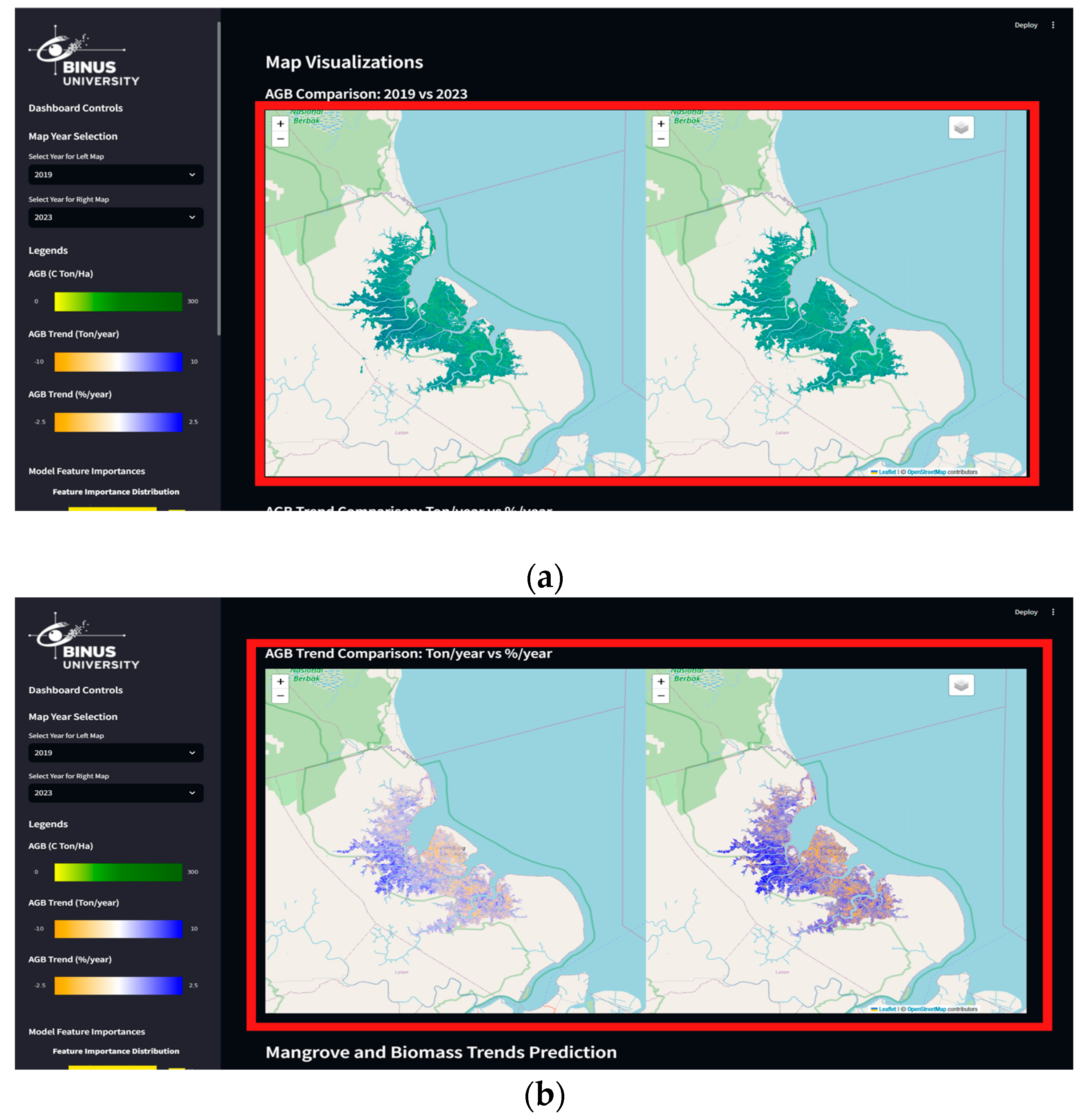

4.3. Biomass Trend Analysis and Forecasting

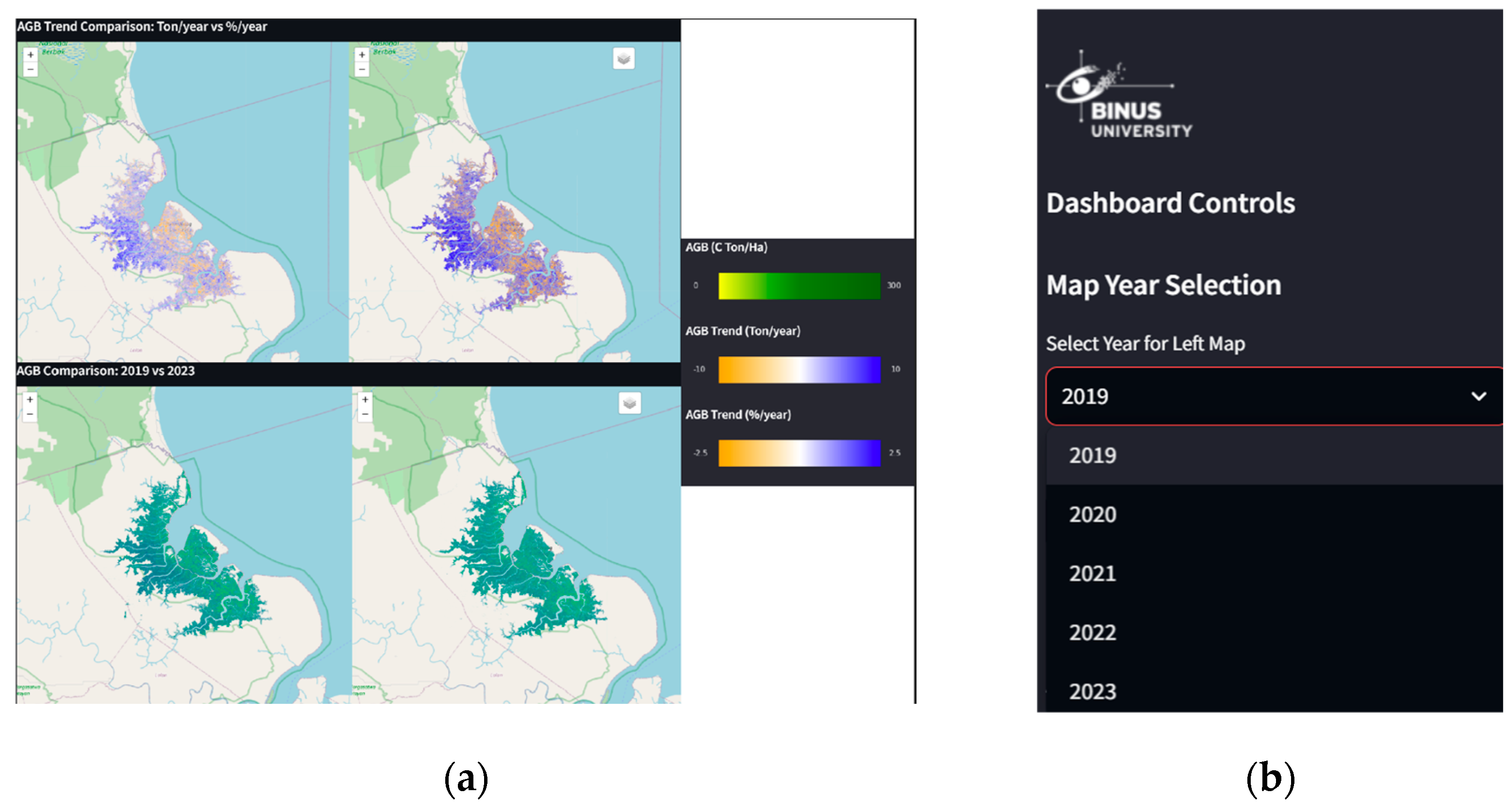

The map visualization system on the dashboard uses the DualMap component of the Folium library, which allows direct comparison between two time periods. The first map displays the AGB comparison between two user-selected years, with an interactive layer showing the distribution of mangrove biomass. The implementation includes a precise coordinate system for the Sembilang National Park region and responsive zoom controls.

The second map focuses on visualizing AGB trends, comparing changes in tonnes/year and percent/year. A custom colormap was implemented to clearly visualize changes, using an intuitive colour scheme to show increases and decreases. Layer controls allow users to enable or disable various visualization layers, providing flexibility in data analysis.

Figure 4.

AGB Map Visualization Year vs Year Comparison (a) and AGB Map Visualization Trend Comparison: Ton/Year vs %/Year (b).

Figure 4.

AGB Map Visualization Year vs Year Comparison (a) and AGB Map Visualization Trend Comparison: Ton/Year vs %/Year (b).

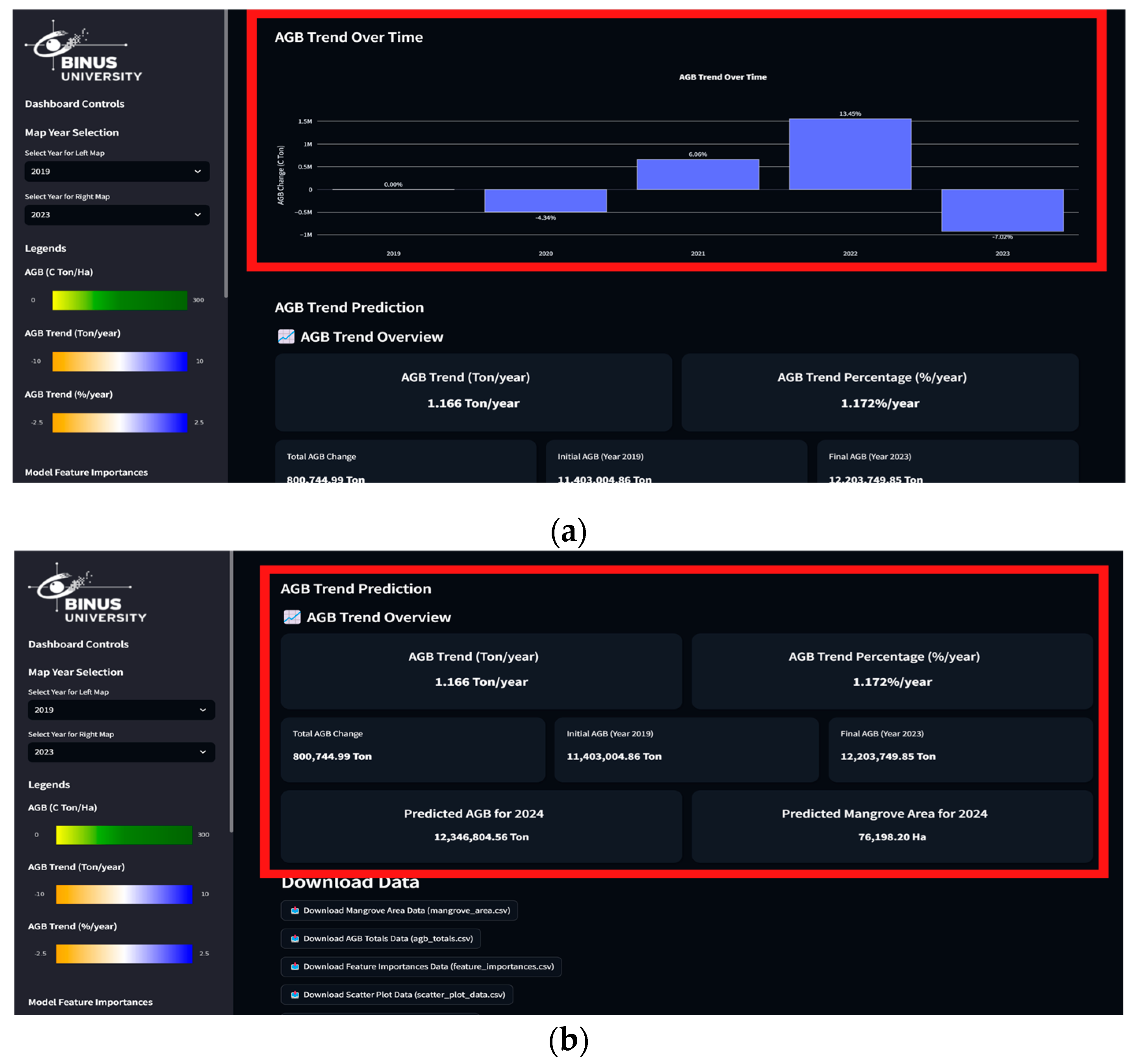

Visualization of the available data can also be used as a combination of bar charts implemented with the Plotly library. The mangrove area bar chart displays year-to-year changes in mangrove area, with value labels and colouring indicating the magnitude of change. The biomass (AGB) graph displays total biomass carbon in tonnes, with gradient colouring helping to visualize temporal trends. AGB Trend Overview is implemented as a comprehensive metrics dashboard, displaying key information on changes in mangrove biomass. The system uses a card-based layout with modern styling to display biomass trends in tonnes/year and percentage/year. Each card displays metrics in an easy-to-read format, with visual indicators to show the direction of change (

Figure 5a). Calculations can also display total biomass change over the observation period, initial and final biomass values, and average annual change. A significant change monitoring system was implemented to identify and flag changes that exceed a certain threshold. Predictions of mangrove biomass and area for 2024 were integrated in a card metrics format consistent with the overall design (

Figure 5b)

Figure 5.

Data Visualization of Mangrove and Biomass trend prediction using Bar Graphs (a) and total biomass change over the observation period (b)

Figure 5.

Data Visualization of Mangrove and Biomass trend prediction using Bar Graphs (a) and total biomass change over the observation period (b)

4.3. Dashboard Testing and Evaluation

Black box testing is conducted to evaluate the functionality of the dashboard without paying attention to the internal code structure. This test focuses on the expected input and output of each dashboard component. The following is a table of testing results.

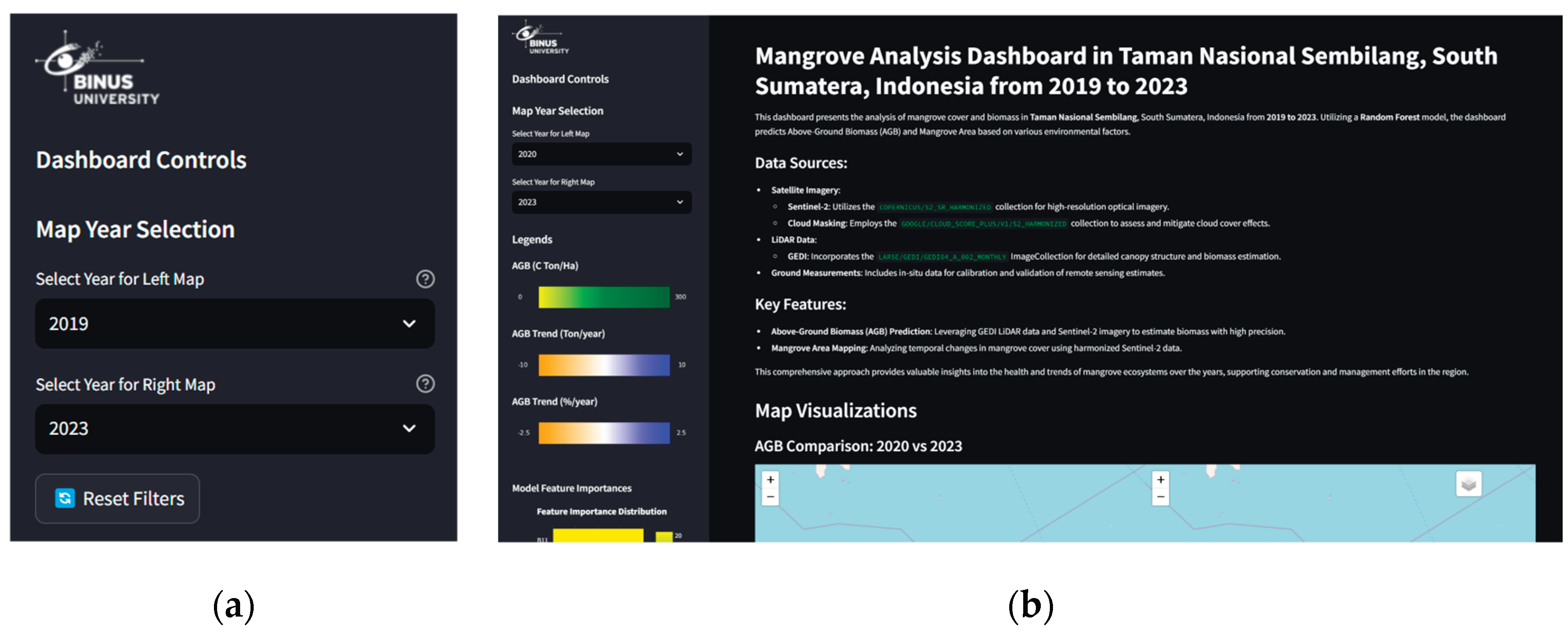

4.3.1. Strive for Consistency

Consistency in interface design ensures that users can understand and use the system without having to relearn each section. For example, the colour scheme used for biomass and AGB trends throughout the visualization’s elements, as well as the uniform sidebar layout for navigation (

Figure 6a). Consistency in interface design ensures that users can understand and use the system without having to relearn each section. For example, the colour scheme used for biomass and AGB trends throughout the visualization elements, as well as the uniform sidebar layout for navigation.

Figure 6.

Visualization of Biomass Colour Schemes and AGB Trends (a) and Visualization of the Dropdown Menu on the Left Panel (b).

Figure 6.

Visualization of Biomass Colour Schemes and AGB Trends (a) and Visualization of the Dropdown Menu on the Left Panel (b).

4.3.2. Enable Frequent Users to Use Shortcuts

The shortcut feature increases usage efficiency for frequent users. Dropdown menu for year selection allows users to quickly select and compare data without the need for repeated navigation (

Figure 6b)

4.3.3. Offering Informative Feedback

Clear feedback helps users understand the status of the system and the results of their actions. Loading indicators while data is being processed and real-time visualization changes after users select certain options provide immediate feedback (

Figure 7a).

4.3.4. Design Dialogs to Yield Closure

Every user interaction should have clear closure. Displaying a notification or visual change once the data has been successfully loaded, as well as a reset feature to return to the initial state, ensures that the user knows the task has been completed (

Figure 7b)

Figure 7.

Visualization of Loading Maps Indicator in Dashboard (a) and Visual Changes at the Turn of the Year (b).

Figure 7.

Visualization of Loading Maps Indicator in Dashboard (a) and Visual Changes at the Turn of the Year (b).

4.3.5. Offer Error Prevention and Simple Error Handling

This dashboard has not fully met the Offer Error Prevention and Simple Error Handling criteria in the 8 Golden Rules proposed by Ben Shneiderman. This is due to the data processing that is done exclusively in the backend, so that the dashboard only functions as a viewer that displays the final data without providing error prevention or handling mechanisms directly to the user. Although there is input validation on year selection to ensure only available years can be selected, as well as clear error messages in case of problems in data processing, these limitations reduce the dashboard's ability to provide interactive feedback or immediate solutions when errors occur. To improve compliance with this rule, further development could consider implementing features such as more comprehensive input validation on the frontend, as well as more informative and user-friendly error handling when problems occur during interaction with the dashboard.

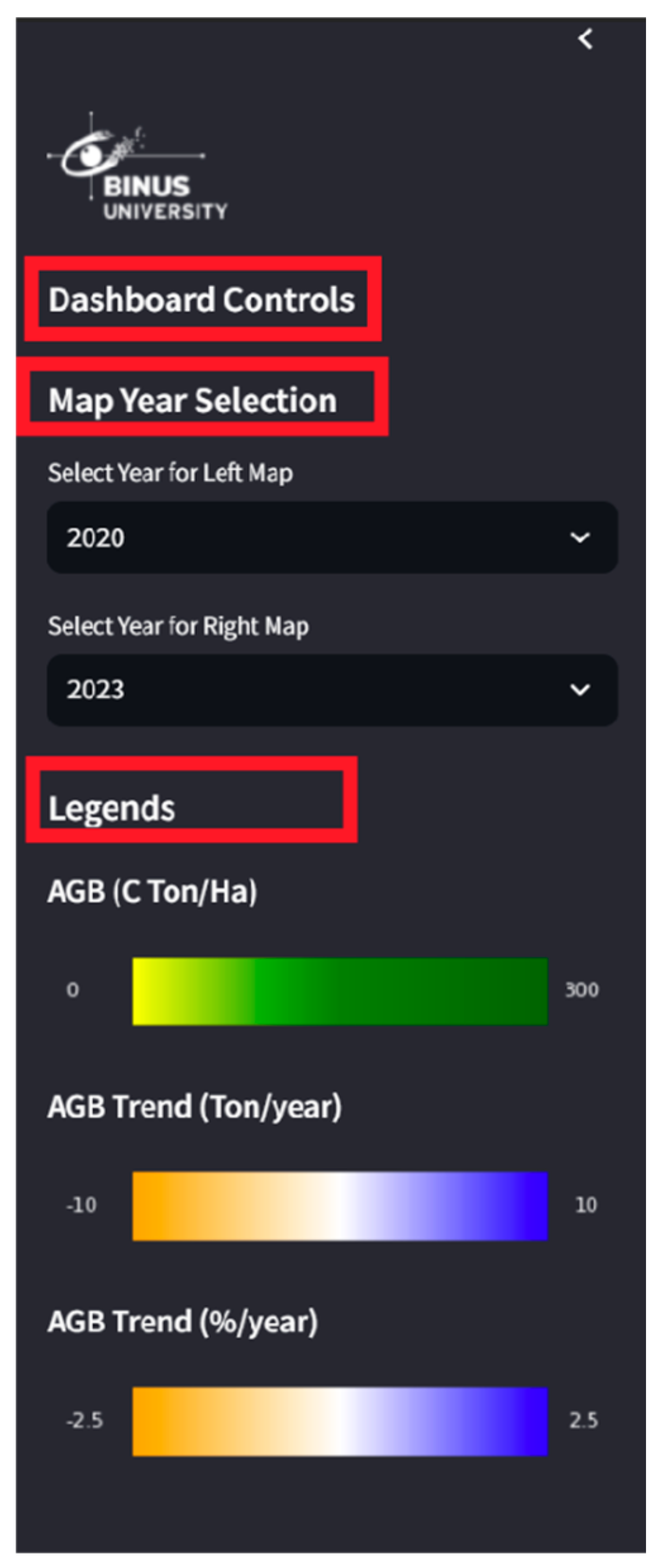

4.3.6. Permit Easy Reversal of Actions

Users can easily undo unwanted actions. The reset feature allows users to return filters and parameters to their initial state with a single click, providing flexibility in data exploration (

Figure 8a)

4.3.7. Support Internal Locus of Control

The user feels in full control of the interaction with the system. Easily accessible controls such as dropdown menus and layer controls allow users to specify the data they want to view and analyze (

Figure 8b)

Figure 8.

Button Reset Filters on Select Year (a) and Sidebar Visualization That Can Be Accessed Anytime (b).

Figure 8.

Button Reset Filters on Select Year (a) and Sidebar Visualization That Can Be Accessed Anytime (b).

4.3.8. Reduce Short-Term Memory Load

The interface design that does not overload the user's short-term memory makes it easy to navigate and understand. The use of clear labels and easy-to-understand legends, as well as the hierarchical organization of information, helps users remember and interpret data without having to rely on their short-term memory (

Figure 9)

Figure 9.

Easy to Understand Sidebar Naming.

Figure 9.

Easy to Understand Sidebar Naming.

5. Conclusions

An Open Sources geospatial intelligence dashboard has been successfully implemented by combining machine learning analysis capabilities and user-friendly design principles. The dashboard successfully integrates various data sources through Google Earth Engine (GEE) and is comprehensively displayed using Streamlit. The comprehensive and user-friendly nature of the dashboard is evidenced by the application of the 8 Golden Rules of Interface Design.

Results on machine learning algorithm performance comparison: Random Forest (RF) showed superior performance compared to Gradient Boosting (GB) for mangrove forest biomass mapping and estimation. This is evidenced by the R² score of RF, which reaches 0.701, higher than GB, which reaches 0.601.

A mangrove forest condition monitoring system has been successfully designed with automated satellite image processing and analysis capabilities. The integration of data from GEE and open sources Streamlit enables efficient processing of large-scale data, considering the availability of cloud-free satellite imagery. The developed open sources dashboard can provide temporal data analysis of mangrove forest condition, including biomass changes and predictions for the coming year, supporting more targeted data-driven decision-making in mangrove forest conservation and management efforts in Sembilang National Park Indonesia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.I. and J.V.K.; Formal analysis, E.I., J.V.K. and E.F.A.S.; Methodology, E.I.; Project administration, E.F.A.S.; Software, J.V.K.; Supervision, E.I.; Validation, E.I. and J.V.K.; Writing – original draft, E.I., J.V.K. and E.F.A.S.; Writing – review & editing, E.I. and E.F.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- P. CAHYANINGSIH, A. K. DEANOVA, C. M. PRISTIAWATI, Y. I. ULUMUDDIN, L. KUSUMAWATI, and A. D. SETYAWAN, “Review: Causes and impacts of anthropogenic activities on mangrove deforestation and degradation in Indonesia,” International Journal of Bonorowo Wetlands, vol. 12, no. 1, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- One Earth, “Mangroves: Nature’s resilient coastal guardians,” EIN: 85-2588841. Accessed: Jun. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.oneearth.org/what-are-mangroves/.

- N. Asari, M. N. Suratman, N. A. Mohd Ayob, and N. H. Abdul Hamid, “Mangrove as a Natural Barrier to Environmental Risks and Coastal Protection,” in Mangroves: Ecology, Biodiversity and Management, Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021, pp. 305–322. [CrossRef]

- N. C. . Duke and J.-W. van. Bochove, The importance of mangroves to people : a call to action. United Nations Environment Programme, 2014.

- H. Akram, S. Hussain, P. Mazumdar, K. O. Chua, T. E. Butt, and J. A. Harikrishna, “Mangrove Health: A Review of Functions, Threats, and Challenges Associated with Mangrove Management Practices,” Forests, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1698, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dinilhuda, A. A. Akbar, Jumiati, and H. Herawaty, “Potentials of mangrove ecosystem as storage of carbon for global warming mitigation,” Biodiversitas, vol. 21, no. 11, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Alongi et al., “Indonesia’s blue carbon: a globally significant and vulnerable sink for seagrass and mangrove carbon,” Wetl Ecol Manag, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 3–13, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Goldberg, D. Lagomasino, N. Thomas, and T. Fatoyinbo, “Global declines in human-driven mangrove loss,” Glob Chang Biol, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 5844–5855, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group, “Mangrove Conservation and Restoration: Protecting Indonesia’s ‘Climate Guardians.’” Accessed: Jun. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/07/26/mangrove-conservation-and-restoration-protecting-indonesia-climate-guardians.

- W. Heumann, “Satellite remote sensing of mangrove forests: Recent advances and future opportunities,” Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 87–108, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kuenzer, A. Bluemel, S. Gebhardt, T. V. Quoc, and S. Dech, “Remote Sensing of Mangrove Ecosystems: A Review,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 878–928, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Pham, N. Yokoya, D. Bui, K. Yoshino, and D. Friess, “Remote Sensing Approaches for Monitoring Mangrove Species, Structure, and Biomass: Opportunities and Challenges,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 11, no. 3, p. 230, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Malik, B. Kuncahyo, and N. Puspaningsih, “Dinamika Perubahan Tutupan Hutan Mangrove Sebagai Kawasan Lindung Menggunakan Citra Satelit di Pulau Peleng Sulawesi Tengah,” Journal of Tropical Silviculture, vol. 14, no. 03, pp. 183–190, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Purwanto and R. Ayuningtyas, “Neuroscience Approach In Understanding The Urban Spatial Form,” TEKNIK, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 25–35, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Darmawan, I. Carolita, and E. Ananta, “Identification of Oil Palm Plantation on Multiscatter and Resolution of SAR Data Using Variety of Classifications Algorithm (Case Study: Asahan District, North Sumatera Province),” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 500, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Zia Ulqodry, A. Agussalim, I. Widiastuti, R. Aryawati, and A. Eko Aprianto, “The Preliminary Assessment of Mangrove Status at Payung Island in Musi Estuary, Indonesia #,” May 2020. Accessed: Jun. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://seminar.bio.unsoed.ac.id/index.php/ICoMIRE/ICoMIRE-2019/paper/view/498.

- Richards and D. Friess, “Rates and drivers of mangrove deforestation in Southeast Asia, 2000-2012,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 2, pp. 344–349, Dec. 2015.

- Sukuryadi, H. I. Johari, Ibrahim, J. S. Adiansyah, and Nurhayati, “Assessing mangrove forest changes using vegetation index algorithm in southern west Lombok,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 1441, no. 1, p. 012002, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. DiGiacomo, R. Giannelli, B. Puckett, E. Smith, J. T. Ridge, and J. Davis, “Considerations and tradeoffs of UAS-based coastal wetland monitoring in the Southeastern United States,” Frontiers in Remote Sensing, vol. 3, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang et al., “A Comparison of Gaofen-2 and Sentinel-2 Imagery for Mapping Mangrove Forests Using Object-Oriented Analysis and Random Forest,” IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens, vol. 14, pp. 4185–4193, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tridawati, A. Armijon, F. Yanto, and T. C. Novianti, “Pemetaan Distribusi Hutan Mangrove Menggunakan Algoritma Machine Learning di Kawasan Hutan Mangrove Petengoran,” Jurnal Tekno Insentif, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 84–98, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Tieng, S. Sharma, R. A. MacKenzie, M. Venkattappa, N. K. Sasaki, and A. Collin, “Mapping mangrove forest cover using Landsat-8 imagery, Sentinel-2, Very High Resolution Images and Google Earth Engine algorithm for entire Cambodia,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 266, p. 012010, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Chan-Bagot et al., “Integrating SAR, Optical, and Machine Learning for Enhanced Coastal Mangrove Monitoring in Guyana,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 16, no. 3, p. 542, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, P. Setiani, and R. Sianturi, “Towards understanding climate change impacts: monitoring the vegetation dynamics of terrestrial national parks in Indonesia,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 18257, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, S. Liu, W. Feng, and G. Dauphin, “Feature Importance Ranking of Random Forest-Based End-to-End Learning Algorithm,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 15, no. 21, p. 5203, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Deb Burman and P. Das, “A Data-Driven Approach to Assess the Impact of Climate Change on a Tropical Mangrove in India,” J Geophys Res Biogeosci, vol. 129, no. 8, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Harsa, G. Winarso, K. T. Setiawan, and W. Asriningrum, “Satellite-based Mangrove species abundance estimate using Machine Learning ensemble,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 1276, no. 1, p. 012055, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., “Large-Scale High-Resolution Coastal Mangrove Forests Mapping Across West Africa With Machine Learning Ensemble and Satellite Big Data,” Front Earth Sci (Lausanne), vol. 8, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Hu, Y. Zhang, Y. Su, Y. Zheng, G. Lin, and Q. Guo, “Mapping the Global Mangrove Forest Aboveground Biomass Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 12, no. 10, p. 1690, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shendryk, “Fusing GEDI with earth observation data for large area aboveground biomass mapping,” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, vol. 115, p. 103108, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang et al., “Estimating mangrove above-ground biomass at Maowei Sea, Beibu Gulf of China using machine learning algorithm with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data,” Geocarto Int, vol. 37, no. 27, pp. 15778–15805, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Feyen, G. Wip, S. Crabbe, V. Wortel, S. P. Sari, and F. Van Coillie, “Mangrove Species Mapping and Above-Ground Biomass Estimation in Suriname Based on Fused Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Imagery and National Forest Inventory Data,” in 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, IEEE, Jul. 2021, pp. 6072–6075. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Ghosh, M. D. Behera, B. Jagadish, A. K. Das, and D. R. Mishra, “A novel approach for estimation of aboveground biomass of a carbon-rich mangrove site in India,” J Environ Manage, vol. 292, p. 112816, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Wu et al., “Comparison of machine-learning methods for above-ground biomass estimation based on Landsat imagery,” J Appl Remote Sens, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 035010, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanian, S. Zaghian, R. M. Asiyabi, M. Amani, A. Mohammadzadeh, and S. Jamali, “Mangrove Ecosystem Mapping Using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Satellite Images and Random Forest Algorithm in Google Earth Engine,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 13, no. 13, p. 2565, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Musthafa and G. Singh, “Improving Forest Above-Ground Biomass Retrieval Using Multi-Sensor L- and C- Band SAR Data and Multi-Temporal Spaceborne LiDAR Data,” Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, vol. 5, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Rijal, T. D. Pham, S. Noer’Aulia, M. I. Putera, and N. Saintilan, “Mapping Mangrove Above-Ground Carbon Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning Approach in Loh Buaya, Komodo National Park, Indonesia,” Forests, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 94, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Purwanto, K. Wikantika, A. Deliar, and S. Darmawan, “Decision Tree and Random Forest Classification Algorithms for Mangrove Forest Mapping in Sembilang National Park, Indonesia,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 15, no. 1, p. 16, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).