1. Introduction

Definition and Overview of 3D Printing 3D printing, or additive manufacturing (AM), refers to a family of processes where material is deposited layer-by-layer to create a 3D object based on a digital design. While initially developed for rapid prototyping, the technology has gained significant traction in industries like aerospace, healthcare, automotive, and defense due to its ability to produce complex and customized parts.

The term AM is often used to describe layer manufacturing, rapid manufacturing (RM), freeform

Fabrication, and rapid prototyping (RP) [

1]. This technology, initially developed for product visualization to speed up the design process hence the name rapid prototyping, has now advanced so far as to produce functional components. Some of the appealing qualities of additive manufacturing which have sparked research interest among industrialists and academics alike are the potential to process a wide selection of materials, tool-less fabrication requiring minimal to no post-processing, and close to zero lead times [

1,

2,

3]. It is because of these abilities AM has found extensive applications in aerospace [

4], biomedical [

5] automotive [

6], and many other sectors [

7]; [

2] the early version of 3D printing is to produce a fast prototype by speeding up the process in model development and shortening lead time between product development and market placement. The requirement to capture the market placement is significant to facilitate the product for not being outdated. In a fraction of time, the company able to produce prototype parts faster compared to conventional manufacturing methods, such as molding, forging, and milling [

8]. Few researchers believed that the product produce by AM is unique as well it can be produced in a short time which is surely able to mass customization [

3]. This is also considered as the growth of 3D printing where the changes in the uses of 3D printing in presenting the trend of new business model. In the meantime, 3D printing acknowledged as one of the fastest-growing fields in AM.

AM is capable of fabricating parts of various sizes from the micro-to macro-scale. However, the precision of the printed parts is dependent on the accuracy of the employed method and the scale of printing [

9]. For instance, micro-scale 3D printing poses challenges with the resolution, surface finish and layer bonding, which sometimes require post-processing techniques such as sintering [

10]. On the other hand, the limited materials available for 3D printing pose challenges in utilizing this technology in various industries. Hence, there is a need for developing suitable materials that can be used for 3D printing. Further developments are also needed to enhance the mechanical properties of 3D printed parts. Objectives of this literature review aims to explore the key advancements in metal 3D printing, examining its fundamental technologies, material properties, applications, challenges, and recent innovations [

11]. Additionally, this review will highlight the emerging trends and future opportunities within the realm of metal 3D printing (additive manufacturing).

1.1. The Central Focus of Current Research in 3D Printing Covers Numerous Disciplines

It reflecting its wide-ranging uses and multidisciplinary nature. Here are the primary attention areas in current research:

There is a broad range of topic areas that are now being investigated in 3D printing, which reflects the revolutionary potential of this technology across a variety of sectors and fields of study. Researchers are making significant progress in the field of

materials development [

12]. They are furthering the development of metal 3D printing using powders of titanium, aluminum, and stainless steel [

13,

14]. Additionally, they are investigating fiber-reinforced composites and developing biomaterials for use in

medical applications.

Sustainability is another primary priority, with attempts being made to produce materials that are both environmentally friendly and recyclable, with the goal of reducing the environmental imprint [

13]. Prosthetics, implants, bio printing tissues and organs, and the personalization of medication delivery systems are all examples of areas in which 3D printing is transforming the healthcare industry.

3D printing technology is being used by the aerospace and automotive sectors for the purpose of producing lightweight components, facilitating quick prototyping, and optimizing performance [

14].

Another developing field is

large-scale construction printing, which involves printing complete structures, such as buildings, bridges, and infrastructure, utilizing cutting-edge materials like as concrete [

15]. Significant shifts are taking place in the industrial manufacturing sector as a result of the introduction of 3D printing, which has the potential to streamline tooling, enable mass customization, and decentralize supply chains [

15,

16].

Advancement in Technological improvements in 3D printing are also noteworthy, including multi-material printing, hybrid processes, and quicker, more efficient printing techniques. The incorporation of 3D printing into STEM curriculum and skill development programs is becoming more common in

education and training. This is being done to ensure that a qualified workforce is available to handle this rapidly developing technology [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Research in the fields of

quality assurance and standardization are essential in order to guarantee the precision, uniformity, and certification of items that are manufactured using 3D printing [

18].

In industrial production,

automotive and aerospace applications, and future industries, underscoring its revolutionary influence on these domains [

19]. Through fast prototyping, 3D printing is allowing performance improvement, transforming the manufacturing of robust and lightweight components, and drastically cutting production timelines in the automotive and aerospace sectors. The capacity to construct intricate geometries and very durable, heat-resistant components that were previously difficult or impossible to make using conventional processes is advantageous to these sectors [

18,

20].

3D printing is making it easier to produce tooling, molds, and jigs in

industrial manufacturing while allowing for mass customization of one-of-a-kind or low-volume products. By encouraging decentralized production, cutting lead times, and cutting prices, it is revolutionizing supply chains. In the industrial sector, hybrid manufacturing procedures that combine traditional methods with 3D printing are further improving accuracy and efficiency [

21,

22].

With creative uses of 3D printing,

emerging areas are also gaining traction. 3D printing makes it possible to produce food products with unique textures, forms, and even nutritional values [

23,

24,

25]. In order to further wearable technology and smart gadgets, experts in electronics are investigating the incorporation of sensors and circuitry into 3D printed components. Cultural heritage is another fascinating field where historical relics are being preserved and rebuilt via 3D printing [

26,

27]. These developments show how adaptable 3D printing is and how it may change industries and open up new paths in a variety of sectors.

Table 1.

Using 3D printing in a variety of fields, its advantages, and its disadvantages:.

Table 1.

Using 3D printing in a variety of fields, its advantages, and its disadvantages:.

| No. |

Area |

Application |

Advantage |

Disadvantage |

Ref. |

| 1 |

Materials Development |

Development of advanced materials such as metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites. |

Enhanced material properties, customization, and compatibility with complex designs. |

High cost of advanced materials and limited recyclability of some materials. |

[28,29,30] |

| 2 |

Healthcare and Bio printing |

Prosthetics, implants, bio printing tissues/organs, and personalized medical devices. |

Patient-specific solutions, rapid prototyping, and reduced surgical costs. |

Regulatory hurdles, ethical concerns in bio printing, and limited scalability for mass production. |

[31,32,33,34] |

| 3 |

Aerospace and Automotive Applications |

Fabrication of lightweight, durable parts, rapid prototyping, and performance optimization. |

Reduced weight, increased fuel efficiency, and cost savings in prototyping. |

High initial setup costs and stringent quality control requirements. |

[35,36,37,38] |

| 4 |

Construction and Large-Scale Printing |

Printing buildings, bridges, and infrastructure components. |

Faster construction times, reduced material waste, and design flexibility. |

Limited material options, high equipment costs, and challenges with large-scale consistency. |

[39,40] |

| 5 |

Sustainability and Circular Economy |

Recycling of materials, use of sustainable inputs, and reducing the environmental footprint. |

Promotes eco-friendly practices, reduces waste, and supports a circular economy. |

Energy-intensive processes and difficulty in achieving full material recovery. |

[41,42] |

| 6 |

Industrial Manufacturing |

Tooling, jigs, molds, and custom part production. |

Decentralized manufacturing, faster lead times, and cost efficiency in low-volume production. |

Limited scalability for high-volume production and dependency on skilled labor. |

[43,44,45,46] |

| 7 |

Advancements in 3D Printing Technologies |

Multi-material printing, hybrid manufacturing, and high-speed printing systems. |

Enhanced efficiency, precision, and the ability to create complex geometries. |

High R&D costs and technological complexities. |

[47,48,49] |

| 8 |

Education and Training |

Incorporation of 3D printing in STEM education and workforce skill development. |

Hands-on learning, fostering innovation, and preparing a skilled workforce. |

High costs of equipment for educational institutions and a steep learning curve. |

[50,51,52] |

| 9 |

Quality Assurance and Standards |

Ensuring reliability, consistency, and compliance with industry standards. |

Improved product quality and safety. |

Time-consuming testing processes and lack of universal standards. |

[53,54,55] |

| 10 |

Emerging Fields |

Food printing, electronics with embedded sensors, and cultural heritage restoration. |

Opens new opportunities, supports niche markets, and promotes innovation. |

Limited market adoption, high cost of entry, and technical challenges. |

[56,57,58] |

2. Fundamentals of 3D Printing

In order to satisfy the unique requirements of many sectors, 3D printing materials development aims to advance and enhance the materials used in the additive manufacturing process. Because the materials have a direct impact on the caliber, functionality, and variety of uses of 3D printed goods, this field is very important [

27,

59].

3D printing materials development is a fascinating and rapidly developing topic that opens up new possibilities in manufacturing, healthcare, and other fields. Widespread adoption is still hampered by the expensive price of modern materials and the limited selection of choices for particular applications [

2,

60]. The potential of 3D printing will be increased by ongoing innovation in this field, making it a more practical option for a larger range of sectors [

61].

2.1. Metal 3D Printing Technologies

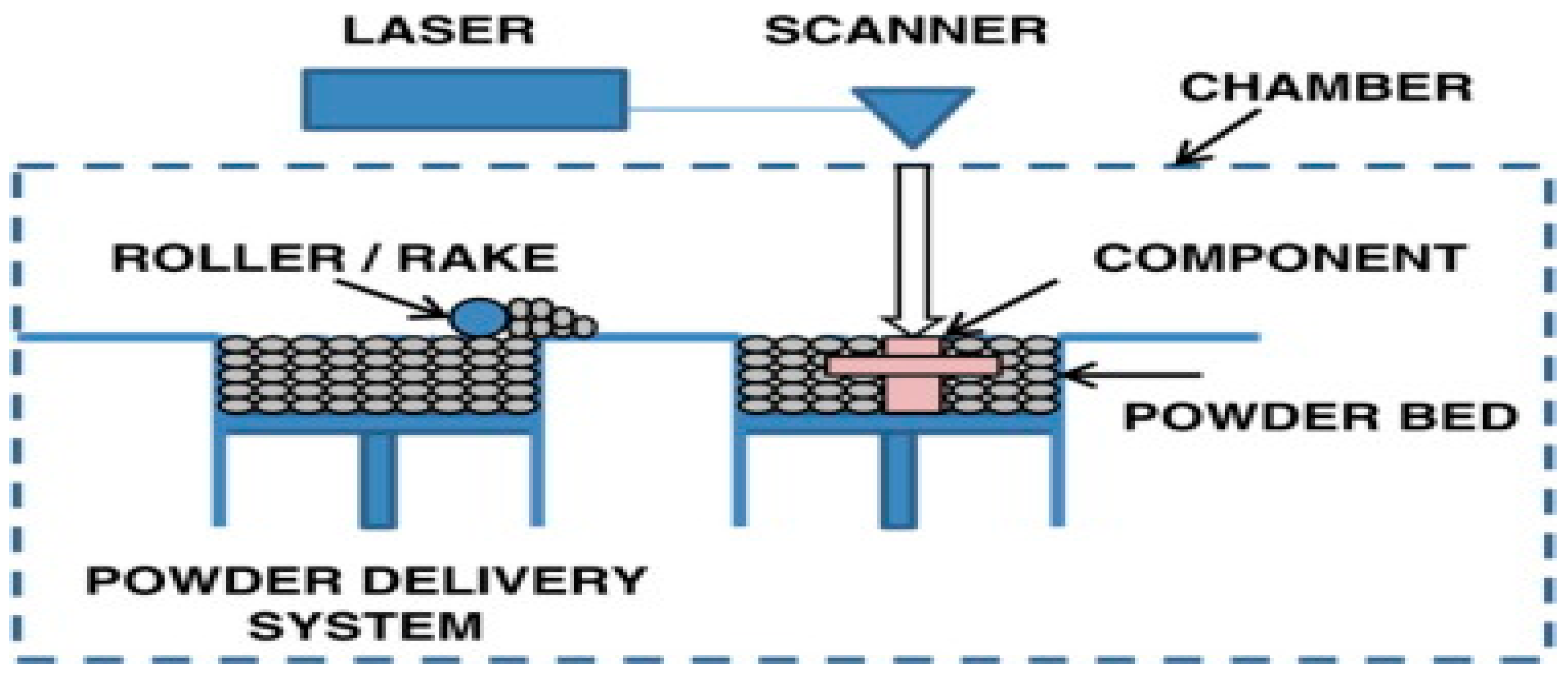

2.1.1. Powder Bed Fusion (PBF)

The PBF family includes methods like Selective Laser Melting (SLM), Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS), and Electron Beam Melting (EBM) [

62]. These methods utilize high-energy lasers or electron beams to selectively melt metal powders, creating solid parts layer-by-layer [

28,

29]. The versatility of PBF allows the production of highly complex geometries with high precision. However, it comes with challenges such as limited build size and the risk of residual stresses that affect part quality [

30].

Figure 1.

The PBF method's schematic diagram [

29].

Figure 1.

The PBF method's schematic diagram [

29].

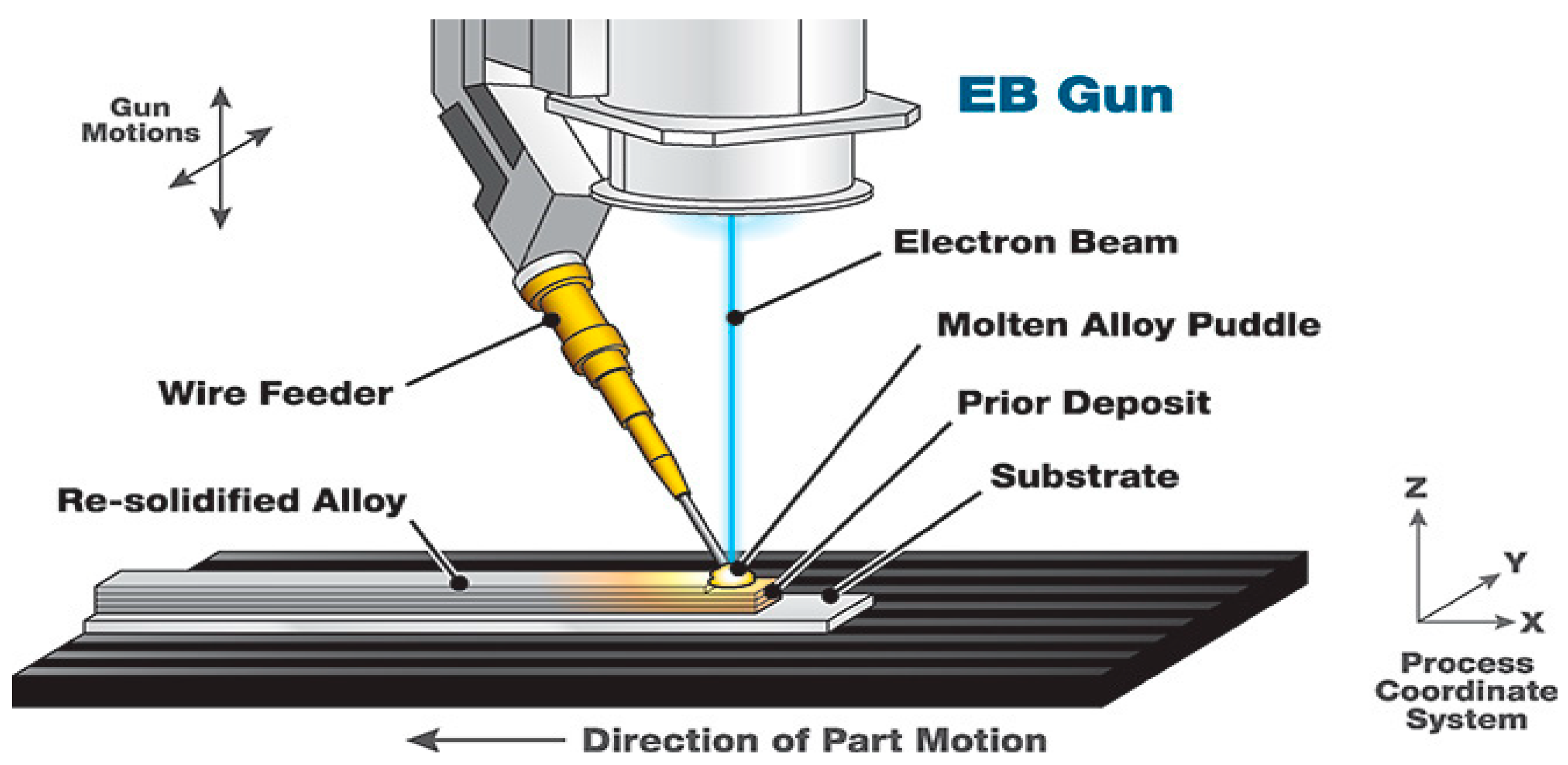

2.1.2. Directed Energy Deposition (DED)

DED methods, including Laser Metal Deposition (LMD) and Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing (EBAM), use a focused energy source (laser or electron beam) to melt metal powder or wire, which is deposited onto a substrate [

31]. These methods offer advantages in repairing and adding material to existing parts. DED allows for large-scale builds and provides excellent control over the material properties, but part resolution and surface finish may not match that of PBF techniques [

32,

33].

Figure 2.

The DED method's schematic diagram [

32].

Figure 2.

The DED method's schematic diagram [

32].

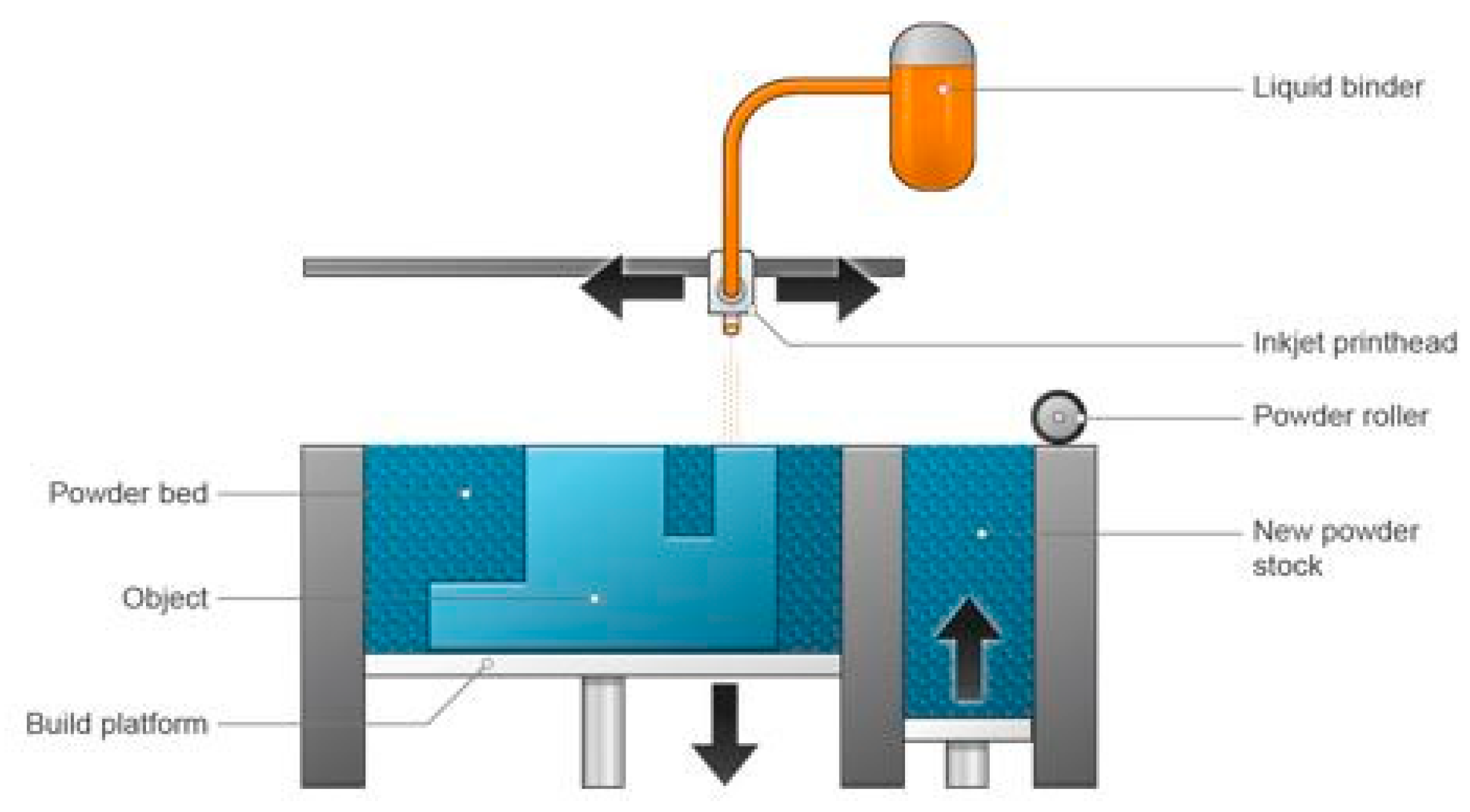

2.1.3. Binder Jetting

Binder jetting is a kind of Inkjet printing that has been tweaked. This method was first presented at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) [

35]. This method employs an inkjet to link things rather than lasers. It takes 2D inkjet printing technology and builds it up in layers to become a 3D model. This method involves the precise deposition of a liquid binder with the aid of a print head that moves along two axes [

63]. A 3D model is first imported into the printer's program, as is the case with all 3D printing processes [

36]. A dispenser is used to provide a consistent flow of powder, which is necessary for printing. The powder is placed in the dispenser before usage [

37]. Binder jetting uses a liquid binder to selectively bond metal powders, which are later sintered in a furnace to create a solid part. The main advantage of Binder Jetting is its high-speed manufacturing capabilities and the ability to use a wide range of metal powders, including stainless steel, bronze, and aluminum. However, parts produced through this method often require post-processing to achieve optimal mechanical properties [

38].

Figure 3.

The binder jetting method's schematic diagram [

37].

Figure 3.

The binder jetting method's schematic diagram [

37].

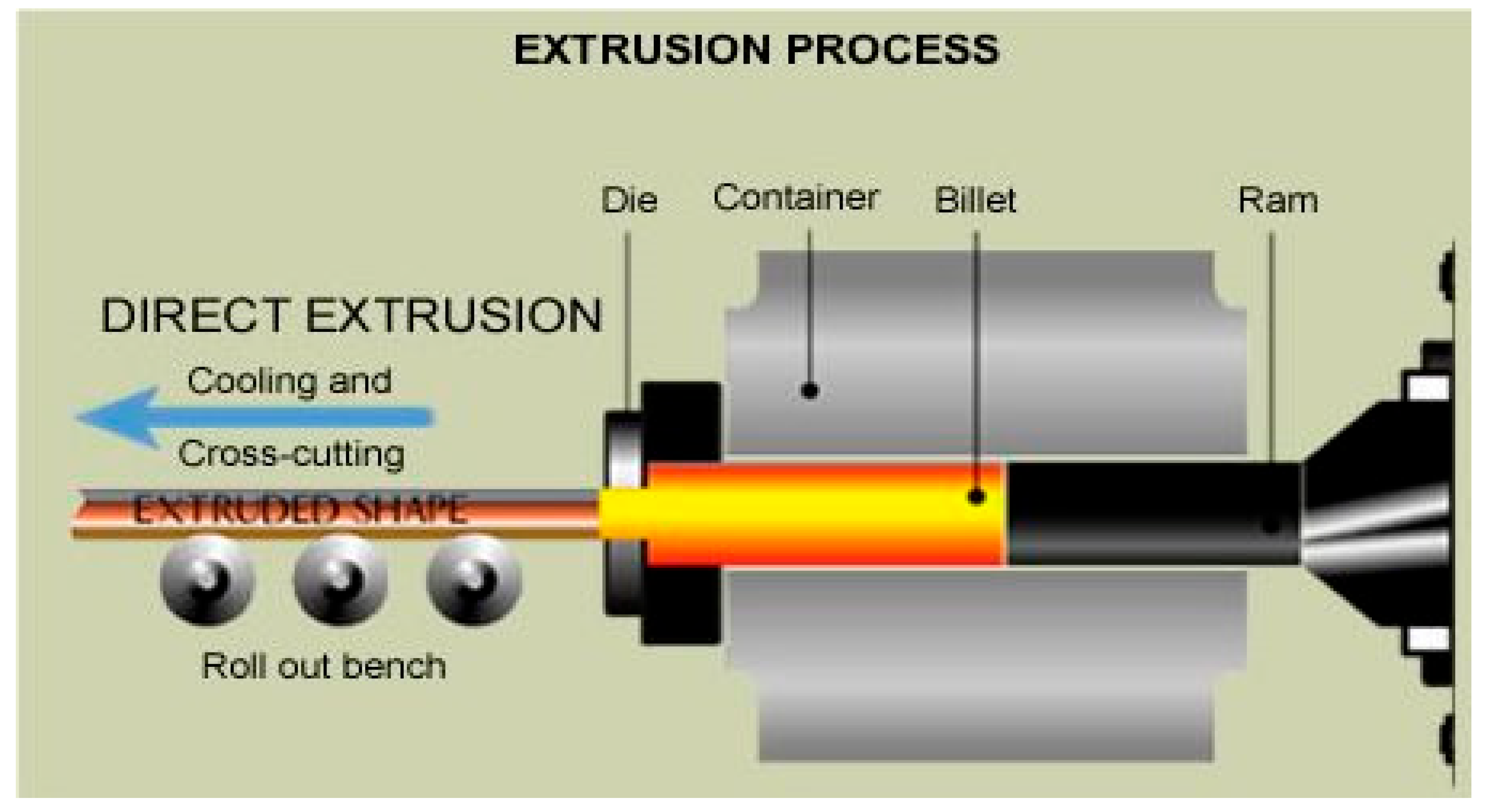

2.1.4. Material Extrusion

Similar to plastic extrusion in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), Metal Extrusion involves feeding a metal filament through a heated nozzle, where it is melted and deposited layer by layer [

64]. While this method is slower compared to others, it offers the advantage of lower equipment costs and is suited for prototyping and small-scale production [

65]. After the heating or melting procedure, the material or substance that flows through the nozzle equipped with a temperature control system will rapidly solidify upon its first contact with the air [

66]. After the deposition of the first layer, the stage is lowered to continue and complete the layer-by-layer formation of the 3D object [

64].

Figure 4.

The material extrusion method's schematic diagram [

65].

Figure 4.

The material extrusion method's schematic diagram [

65].

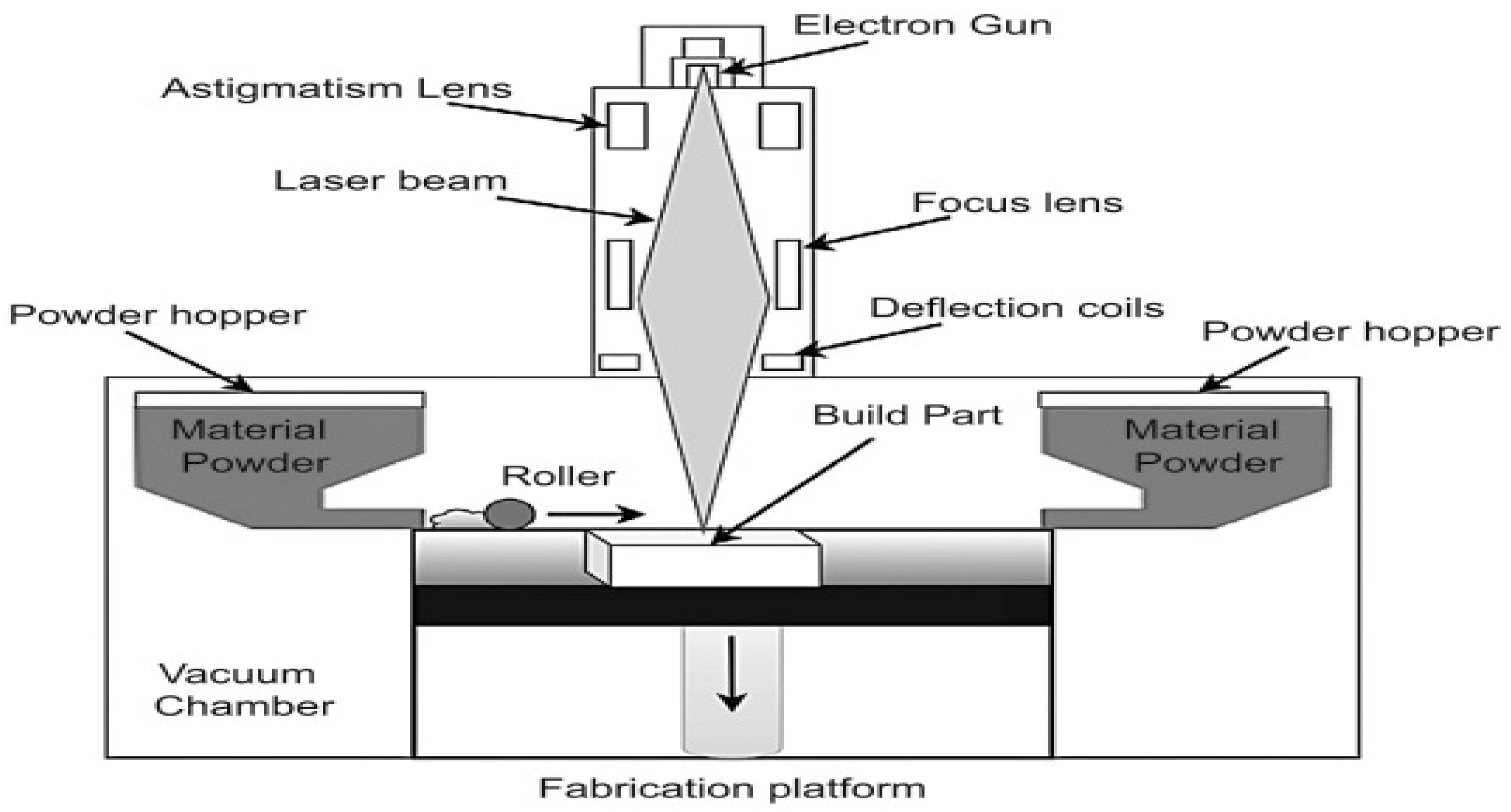

2.1.5. Electron Beam Melting (EBM)

In the 1990s, researchers at the University of Sweden developed the electron beam melting process. It is similarly similar to an SLS method based on powder technology but the laser scanner is replaced with an electron beam of 4 KW to generate fully dense part [

39]. Due to nature of laser sintering process the porosity cannot easily be avoided. When an electron travelling at half the speed of light hits a powder surface, it induces kinetic energy, which causes the powder to melt. For conductive material, in general, the electron beam is more energy-efficient than a laser. Powder-based machine and a part is manufactured on an EBM. The part is designed in a 3D CAD program or produced from a patient’s CT-scan. As described in introduction the part is saved in STL file format and uploads in machine. The part is constructed layer-by layer up by melting metal powder with the EBM method [

67]. The outcome is a 3D metal part with a functioning section, which can be directly employed in operation. The pieces are produced in a vacuum and to increase material qualities and restrict internal stresses the temperature in a vacuum chamber is kept at roughly 1000

oC. A layer of powder metal is put over the powder bed or platform which is placed in chamber of a vacuum. A metal powder is preheated to decrease the residual stress concentration in finished part which prevents the distortion. The electron beam [

40] cannon used to selectively sinter the warmed metal powder by reducing the speed or raising the beam power. The electrons released from electron beam are heated over 2500

oC and with half the speed of light these electrons are driven through the anode. A magnetic lens brings the beam into focus, while another magnetic field controls the deflection of the beam [

68]. After this the focused electron beams impacts the powder bed, kinetic energy is developed and transferred into the heat energy which is utilized to melts the metal powder. By adjusting the quantity of electrons in beam the power is controlled. To acquire properly defined hardening of fabricated item the cooling should be managed [

69]. As with other processes, the pieces require some final machining following production. The processing of part in a vacuum offers a clean environment that improves metal properties. After completing the one layer the powder bed platform is lowered and new layer of metal powder is spread by roller mechanism, the same roller is used to level the powder bed [

70]. This process will continue till the complete three dimensional pieces is being created. The upshot of this process is manufacturing of entirely dene component. The finished part is utilized to generate prototypes, models, molds, tools, patterns and even the part can be directly employed in a fully functional operation [

39,

40].

Figure 5.

The EBM method's schematic diagram [

71].

Figure 5.

The EBM method's schematic diagram [

71].

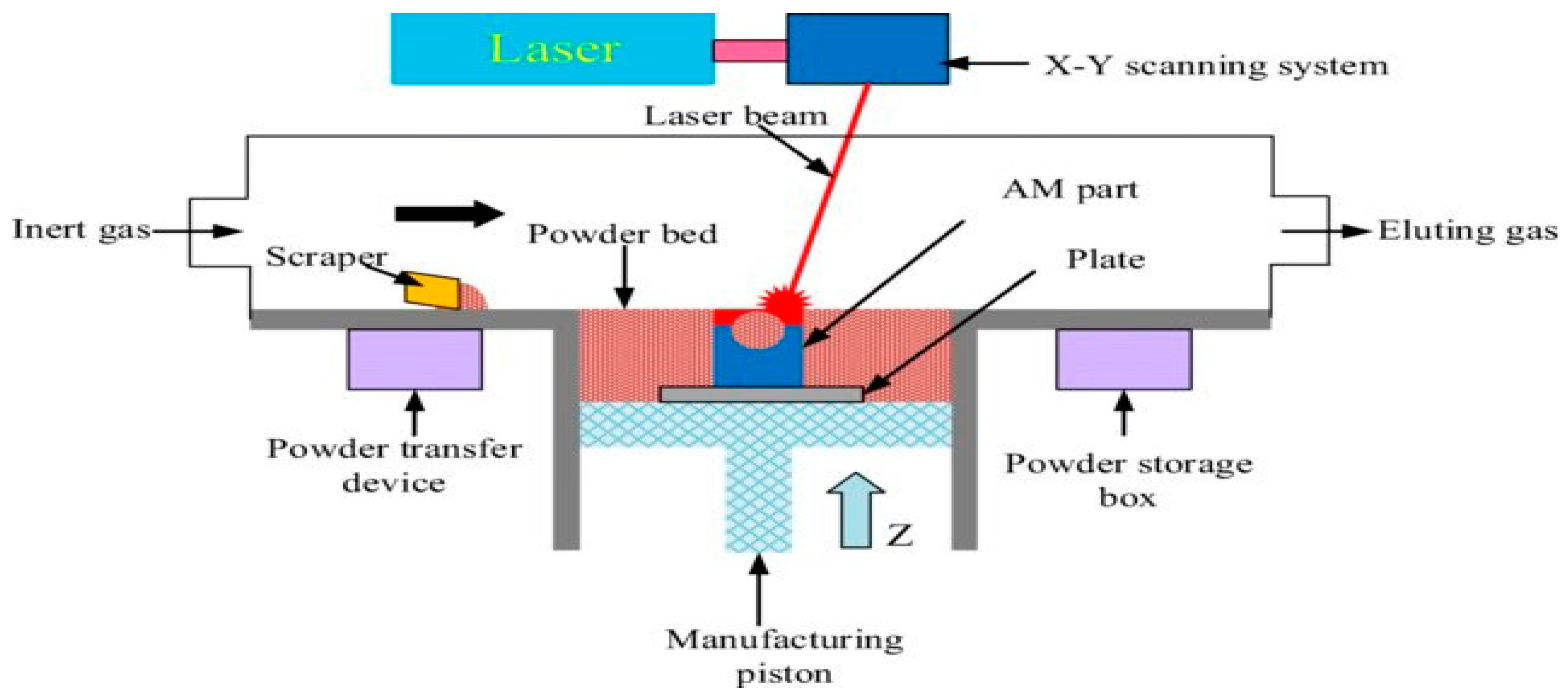

2.1.6. Selective Laser Melting (SLM)

This technology involves the fusion of both metallic and non-metallic particles. This fusion is achieved by melting a binding agent or a metal having a lower melting point [

41]. On the other hand, SLM utilizes a high-powered laser with a limited focus to melt metal particles completely at a rapid rate. SLM demands a larger power density compared to SLS [

42]. Although SLM-produced parts offer robust mechanical qualities, they can typically generate considerable internal stresses caused by the heat gradients that arise during manufacture [

72]. Consequently, additional heat treatment is frequently necessary to reduce these strains.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the selective laser melting (SLM) system [

42].

Figure 6.

Schematic of the selective laser melting (SLM) system [

42].

Table 1.

Materials, Application, Benefits and Drawbacks in metal 3D printing technology.

Table 1.

Materials, Application, Benefits and Drawbacks in metal 3D printing technology.

| No. |

Method |

Materials |

Application |

Benefits |

Drawbacks |

Ref. |

| 1 |

Powder Bed Fusion (PBF |

Metal powders (e.g., titanium, aluminum, stainless steel) |

Aerospace, medical implants, tooling |

High precision, excellent surface finish, complex geometries |

High cost, slow production, requires fine metal powders |

[28,29,30] |

| 2 |

Directed Energy Deposition (DED) |

Metal powders or wires |

Repairing parts, large-scale manufacturing |

High build speed, ability to repair and add to existing parts |

Rough surface finish, limited detail, requires extensive post-processing |

[31,32,33] |

| 3 |

Binder Jetting |

Metal powders with binders |

Prototypes, lightweight parts |

Low cost, fast production, scalable to large parts Low cost, fast production, scalable to large parts |

Requires sintering, weaker mechanical properties compared to other methods |

[35,36,37,38] |

| 4 |

Electron Beam Melting (EBM) |

Metal powders (e.g., titanium, cobalt-chrome) |

Aerospace, medical implants |

High strength parts, no residual stresses due to vacuum process |

Limited material options, expensive equipment |

[9,39,40,73] |

| 5 |

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) |

Metal powders (e.g., stainless steel, Inconel) |

Aerospace, automotive, medical |

High density parts, fine detail, customizable properties |

High energy use, expensive, sensitive to process parameters |

[41,42,56,74] |

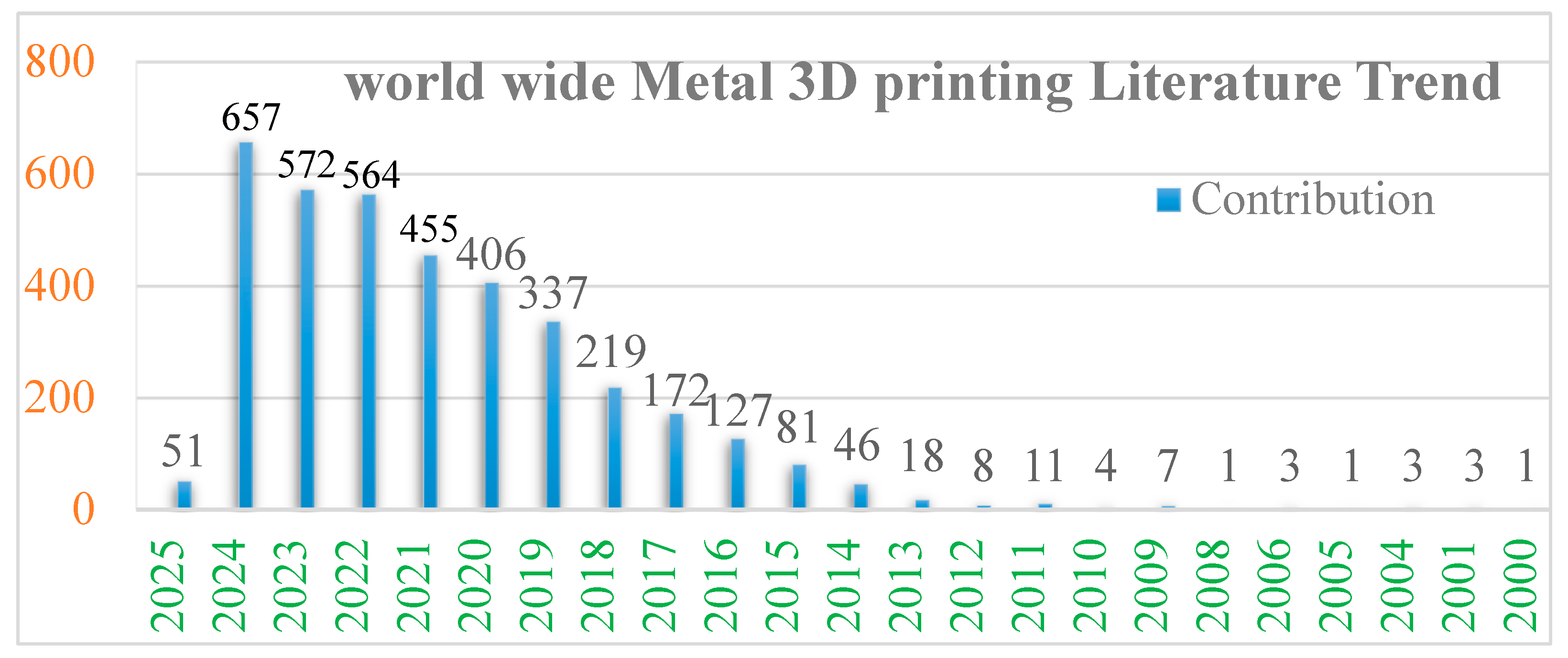

Figure 7.

Graphical overview and trend in the literature used in the current study from Elsevier data-base.

Figure 7.

Graphical overview and trend in the literature used in the current study from Elsevier data-base.

The data on publications pertaining to metal 3D printing reveals that there has been a substantial rise in the number of references over the course of the years, notably in the most recent decade. Despite the fact that the year is still in its early stages, there have already been 51 publications in the year 2025. There was a significant increase to 657 publications in the year 2024, which marked the highest point of interest and involvement. When compared to 2023, which had 572 mentions, and 2022, which had 564 mentions, this was a huge increase. A total of 455 papers were published in the area of metal 3D printing in 2021, 406 publications were published in 2020, and 337 publications were published in 2019. According to these data, there has been a consistent rise in the amount of attention paid to the technology by both academic institutions and businesses [

75]. Going back even farther, the years 2018 and 2017 each had 219 and 172 mentions, respectively, demonstrating a distinct rising trend in comparison to the years that came before. The number of publications in the years 2016 and 2015 was 127 and 81, respectively, which represented a little rise in comparison to the years that came before. The 2014-2013 era witnessed fewer publications, with just 46 and 18 references, respectively, demonstrating that metal 3D printing was still in its early phases. Publications were much fewer in the years previous, with numbers ranging from 1 to 11 between 2001 and 2012, showing that the technology was in its infancy with limited applications and interest. This data demonstrates quite clearly how metal 3D printing has developed from a specialized technique into an area that is receiving a large amount of attention from both research and industry, especially in the most recent few years [

39,

40,

67].

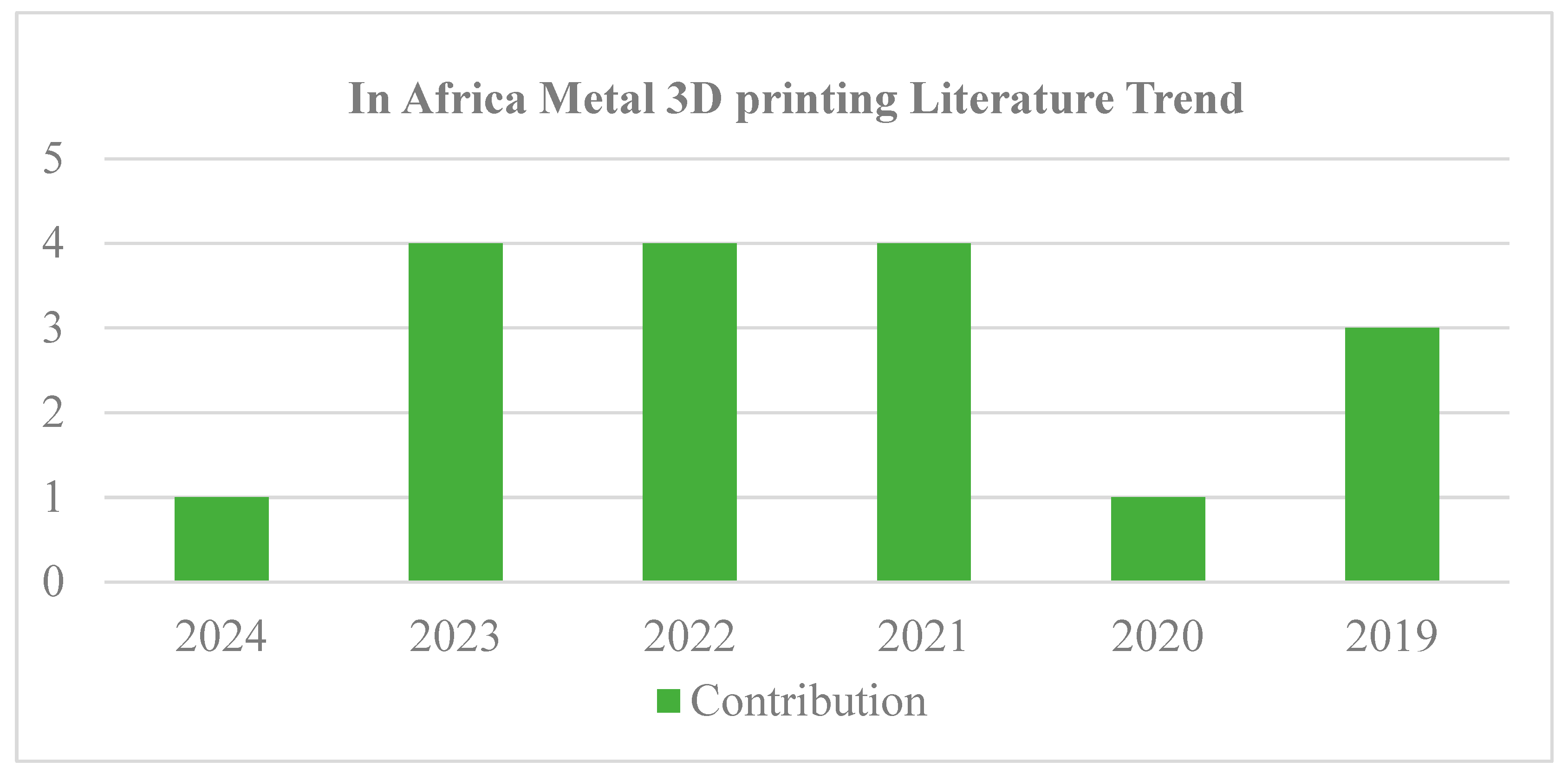

Figure 8.

African Metal 3D Printing Graphical overview from Elsevier data base.

Figure 8.

African Metal 3D Printing Graphical overview from Elsevier data base.

According to the publishing data on metal 3D printing in Africa, the level of activity is quite modest when compared to trends happening throughout the world. In the year 2024, there was just one publication that was associated with metal 3D printing, which indicates that there was very little attention paid to this topic during that year. In a similar vein, there was just one publication documented in the year 2020, which indicates that there was a minimal amount of study and application during that time period [

76]. On the other hand, the years 2021, 2022, and 2023 each had four publications, indicating that there was a minor rise in interest over the course of these three years. In the year 2019, there were three publications, which indicates that there was a moderate amount of activity at that time. Despite the fact that there is a certain amount of interest in metal 3D printing throughout Africa, the area is still in its early phases of growth in comparison to other regions. Over the last several years, there have been intermittent publications around the continent. According to the statistics, there is opportunity for substantial growth in the field of metal 3D printing in Africa, particularly in terms of research and development as well as opportunities for industrial applications [

77].

3. Materials Used in Metal 3D Printing

Titanium Alloys: Titanium is highly favored for aerospace, medical, and automotive applications due to its strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. Alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V are commonly used in metal 3D printing [

78]. However, titanium’s high cost and sensitivity to oxygen contamination during processing present challenges in its widespread adoption. Much attention. Trabecular bone structure is one of the examples that can be designed by 3DP, and the obtained Ti porous structures can improve the bioactivity of implant, enhance cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of osteoblasts [

7]. performed a systematic investigation about different aspects of 3D printed porous Ti-based materials that were produced by the EBM technique [

79]. The highly porous and well-interconnected pore architecture shows good mechanical properties with enhancements in biological activity, osteoblast adhesion, cell morphology, proliferation, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. Moreover, to produce a Ti-based porous structure by the EBM technique. designed a repeating array of titanium alloy unit-cells to mimic trabecular or cancellous bone structure [

80]. Toward this end, various kinds of unit cells mimicking the trabecular bone structure with different pore sizes and porosity were produced. The result shows that the capacity of load-bearing is dependent on the porosity; a higher porosity value leads to a reduction of the 3D printed porous structure manifested a 96% decrease in elastic modulus and strength values. AM manufactured porous titanium interbody cages are very useful in spine treatment, and they have desirable levels of biocompatibility that is beneficial for better bone ingrowth and fixation [

81]. A comparative in vivo study that utilized 3D printed titanium porous implants produced by Stryker on several mature sheep found that bone ingrowth on porous titanium alloy was superior to both PEEK and plasma spray-coated implants and the histo morphometric results showed better osteoblastic deposition on these implants [

11]. Furthermore, peri-implant osteogenesis and increased stability were observed in 3D printed titanium samples. The titanium porous materials can be further improved in different strategies. For instance, Song

et al. capitalized upon the varying macro architectures and surface topological morphology on SLM produced porous titanium for modulation [

82]. This dual modulation was initially carried out together with the utilization of a wide range of compressive strengths and subsequently by alkali treatment, heat treatment, and hydroxyapatite coating formation through electrochemical deposition. The

in vitro results indicated good cyto compatibility, improved osteon cell adhesion, and proliferation, while

in vivo experiments indicated superior tissue-materials interfaces in dual modulated samples [

83].

Aluminum Alloys: Aluminum is widely used in industries like aerospace and automotive due to its lightness and ease of machinability. 3D printing with aluminum allows for parts with complex internal structures that are both lightweight and strong. The development of aluminum alloys optimized for additive manufacturing, such as AlSi10Mg, has led to improved performance and material properties [

84].

Aluminum alloys (AAs) are in great demand in many sectors, including the automotive, aerospace, and aircraft industries. With advances in additive manufacturing (AM) techniques, process time and cost of building Al-based components can be greatly reduced. 1, 2 Options for fabricating complex geometries as one piece have opened up. The main conceptual fields of applications where AM of AAs would be disruptive include: Light weighting, Components with conformal cooling channels & High-cost AAs [

84].

Stainless Steel and Inconel: Stainless steel (e.g., 316L) and Inconel (e.g., Inconel 718) are durable materials known for their high temperature and corrosion resistance. These metals are frequently used in industries that require parts with high mechanical strength and resistance to extreme environments, such as aerospace and energy sectors [

85].

Emerging Materials: New alloy formulations tailored specifically for 3D printing are constantly being developed, such as high-strength nickel alloys and copper alloys. There are also ongoing efforts to combine metal with other materials (e.g., ceramics or composites) to produce parts with unique properties like enhanced thermal conductivity or wear resistance [

86].

Cobalt chromium (CoCr) alloys: significant importance and utilized extensively in high loaded areas. Nonetheless, the stress shielding effect and bone resorption are the major concerns when it comes to applications due to the high stiffness level of CoCr alloys [

87]. Smart design and structural modifications can help overcome these issues; one of the best options to reduce the stiffness mismatch in metal-alloy implants’ interface and the periphery natural bone tissue is designing the porous structures. In this regard, additively manufactured CoCr alloys have attracted much attention [

88]. produced a 3D printed CoCr alloy specimen with interconnected open-pore architecture and macro-geometry with EBM technology [

87]. The produced samples were implanted in adult sheep femora and the outcomes after 26 weeks revealed that the density of osteocyte was higher in the CoCr sample compared to that in Ti6Al4V, but the total bone-implant contact of Ti6Al4V was higher. Furthermore, the CoCr alloy does not significantly change the mineralized interfacial tissue composition compared to Ti6Al4V alloy. Overall, the results indicated the possibility of bone in growth in the interconnected porous structure of CoCr samples. In a different study [

87]. studied the micro-pore structure, biological response, and mechanical properties of CoCr alloy scaffolds that were produced by SLM and reported that the SLM techniques are capable of fabricating the CoCr cellular structures with graded beam thickness and the unit cells with pillar-octahedral shape and human bones share the similar mechanical properties and morphology [

87].

Tantalum: Tantalum is an inert material both in

in vivo and

in vitro condition and has low solubility and very low toxicity in its pure and oxide forms. This material has been clinically utilized since 1940 and its applications in implantation and diagnosis are growing [

87]. The characteristics of tantalum, which are similar to that of cancellous bone, enable its applications in orthopedic surgeries in the spine and hip, knee arthroplasty, and as bone graft substitutes [

87] studied this open-cell design with continuous dodecahedrons unit cells indicated enhanced volumetric porosity (70 – 80%), low Young’s modulus (~3 MPa), and improved frictional properties. Furthermore, it has good biocompatibility and can produce a self-passivating surface oxide layer which is beneficial for biological applications. Therefore, tantalum is an appropriate option for biomedical applications, and 3DP of tantalum would be a good way to further improve its features [

89]. In 2017, a Chinese research group performed.

Table 2.

Materials, Application, Benefits and Drawbacks in Materials Used in Metal 3D Printing.

Table 2.

Materials, Application, Benefits and Drawbacks in Materials Used in Metal 3D Printing.

| No |

Materials |

Applications |

Benefits |

Drawbacks |

Ref. |

| 1 |

Titanium Alloys |

Aerospace, medical implants |

Lightweight, high strength, corrosion resistance |

Expensive, challenging to process |

[7,79,82] |

| 2 |

Aluminum Alloys |

Automotive, aerospace, lightweight parts |

Lightweight, good thermal and electrical conductivity |

Lower strength compared to other alloys |

[31,32,33] |

| 3 |

Stainless Steel |

Tooling, medical devices, industrial parts |

High strength, corrosion resistance, biocompatibility |

Higher density, less suitable for lightweight parts |

[35,36,37,38] |

| 4 |

Cobalt-Chrome |

Medical implants, turbine blades |

Excellent wear and corrosion resistance, biocompatible |

Brittle, expensive |

[39,40] |

| 5 |

Inconel (Nickel Alloys) |

Aerospace, energy, high-temperature parts |

Heat resistance, corrosion resistance, strength |

High cost, challenging to machine |

[90,91] |

| 6 |

Copper Alloys |

Electronics, thermal applications |

Excellent thermal and electrical conductivity |

Reflectivity challenges with lasers, soft material |

[92,93] |

| 7 |

Tool Steels |

Molds, dies, and cutting tools |

High hardness, wear resistance |

Limited ductility, post-processing often required |

[94,95] |

4. Applications of Metal 3D Printing

4.1. Aerospace Industry

The aerospace sector was one of the first to adopt metal 3D printing, where weight reduction and the ability to manufacture complex geometries are essential [

96]. Components like turbine blades, fuel nozzles, and structural brackets are prime examples of parts fabricated using metal 3D printing. A notable example is GE Aviation’s LEAP engine fuel nozzle, which is produced using SLM and consists of complex internal cooling channels, improving fuel efficiency and performance [

97].

Figure 7.

The aerospace applicable area picture [

97].

Figure 7.

The aerospace applicable area picture [

97].

4.1.1. Process Optimization

Challenges in attaining constant repeatability and traceability owing to several distinct process factors that need fine-tuning. The trial-and-error approach for optimizing metal printing processes is inefficient, which results in high material costs and delays in the printing process [

98,

99].

4.1.2. Integration of AI

In order to improve accuracy, cut down on waste, and guarantee consistency in output, there is a pressing need for a more comprehensive integration of artificial intelligence for real-time monitoring and optimization [

100].

4.1.3. Material-Specific Issues

Because of the different thermal characteristics and solidification behaviors of metals, there are challenges involved in the management of printing processes that include several materials [

99].

4.1.4. Real-World Application Barriers

Only a limited capacity for scalability and quality control is available for aircraft components that must meet strict performance criteria and high reliability requirements [

100].

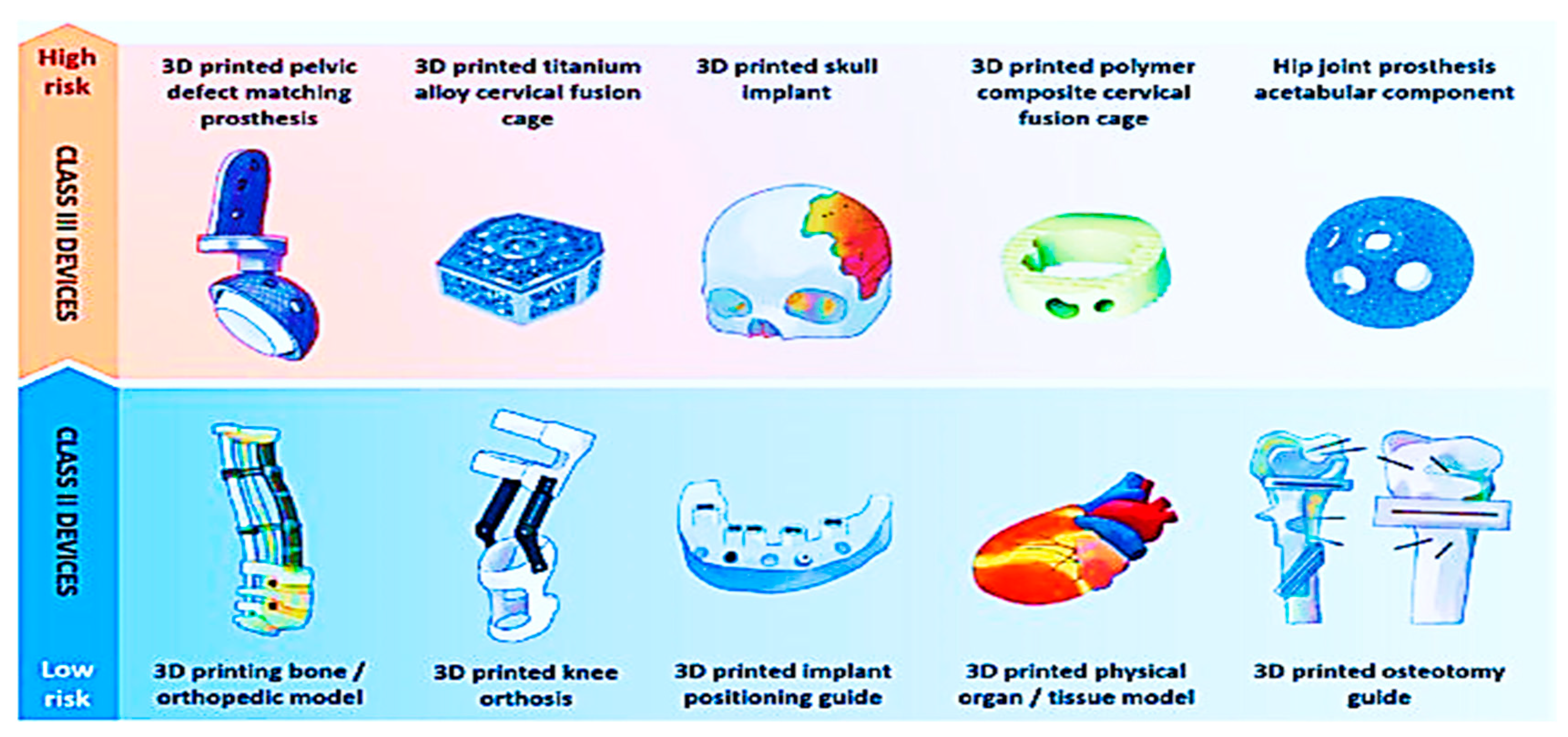

4.2. Medical and Healthcare

Metal 3D printing has transformed the medical field, particularly in the production of personalized implants and prosthetics. The ability to design patient-specific implants (e.g., for joint replacements) based on CT scans has reduced recovery time and improved patient outcomes [

101]. In addition, metal 3D printing is used in custom surgical instruments, dental implants, and anatomical models for pre-surgical planning. For example, 3D-printed titanium skull implants have been successfully used to replace portions of damaged skulls [

102].

4.2.1. Material Development:

There has been a limited amount of research conducted on biodegradable metal implants and its capacity to be optimized for controlled deterioration inside the human body. The need for materials that are both biocompatible and versatile, and that can easily interact with the biological systems that are already in place [

103].

4.2.2. Technological Challenges:

Improvement necessary in common 3D metal printing processes such as Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) and Directed Energy Deposition (DED) for improved mechanical and structural results. Optimization of implants employing sophisticated technologies like AI to fit load-bearing needs [

103].

4.2.3. Multi-material Integration:

Lack of advanced systems to create monolithic and multi material structures tailored for complex biomedical applications [

103].

Figure 8.

The picture of the healthcare and medically relevant area [

103].

Figure 8.

The picture of the healthcare and medically relevant area [

103].

4.3. Automotive Industry

The automotive sector is increasingly adopting metal 3D printing for both prototyping and production of end-use parts. Light weighting is a key driver in this industry, as metal 3D printing can produce intricate structures that traditional methods cannot [

104]. Companies like Ford and BMW are using metal 3D printing to manufacture functional parts like engine components, suspension elements, and prototypes for new designs [

105].

Figure 9.

The 3D printing automobile industry applicable area picture [

105].

Figure 9.

The 3D printing automobile industry applicable area picture [

105].

4.4. Tooling and Industrial Manufacturing

Metal 3D printing is revolutionizing tooling, enabling the production of custom tools and molds for injection molding and die-casting. For instance, 3D-printed conformal cooling channels in injection molds allow for more uniform cooling, which reduces cycle time and improves part quality. This is especially useful in industries where high precision and rapid turnaround times are required [

106,

107].

Figure 10.

The relevant area image for tooling and industrial manufacturing [

106].

Figure 10.

The relevant area image for tooling and industrial manufacturing [

106].

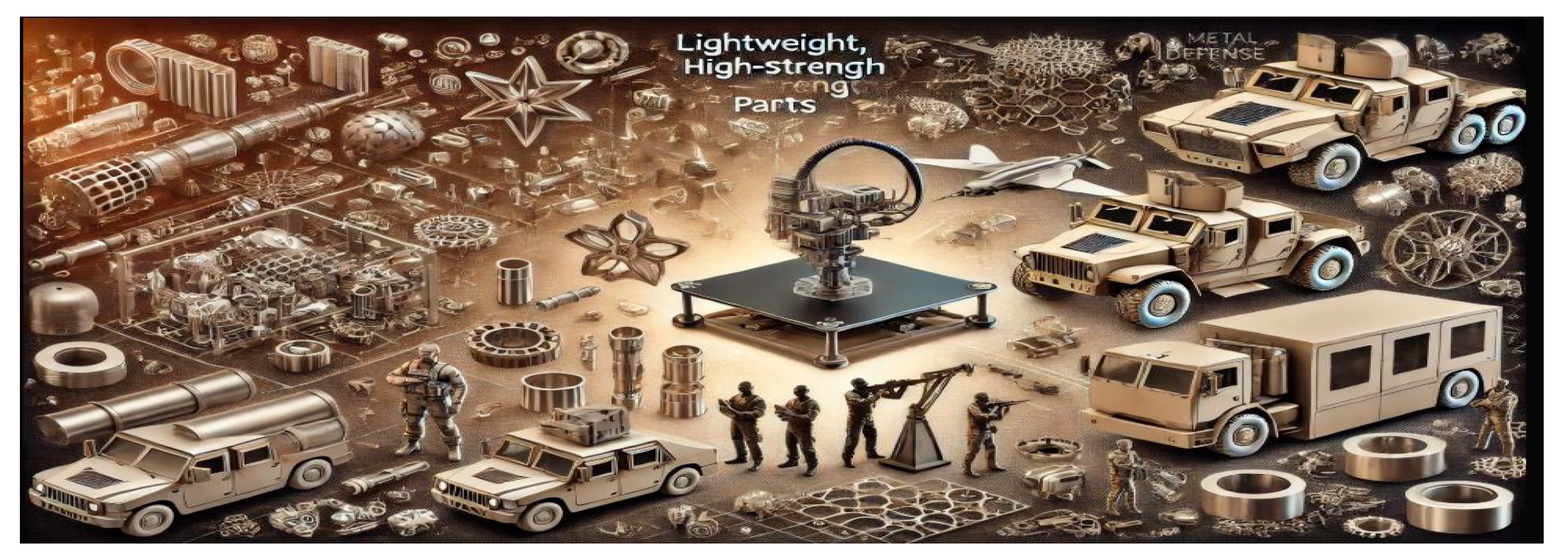

4.5. Defense and Military

In the defense sector, metal 3D printing is used to produce lightweight, high-strength components for weapons systems, vehicles, and drones [

108]. The ability to produce custom parts on demand significantly enhances military flexibility and reduces supply chain dependency. For example, the U.S. Navy has been using 3D printing to produce spare parts for ships, reducing the need for expensive and slow logistics [

109].

Figure 11.

The relevant area picture for defense and military [

109].

Figure 11.

The relevant area picture for defense and military [

109].

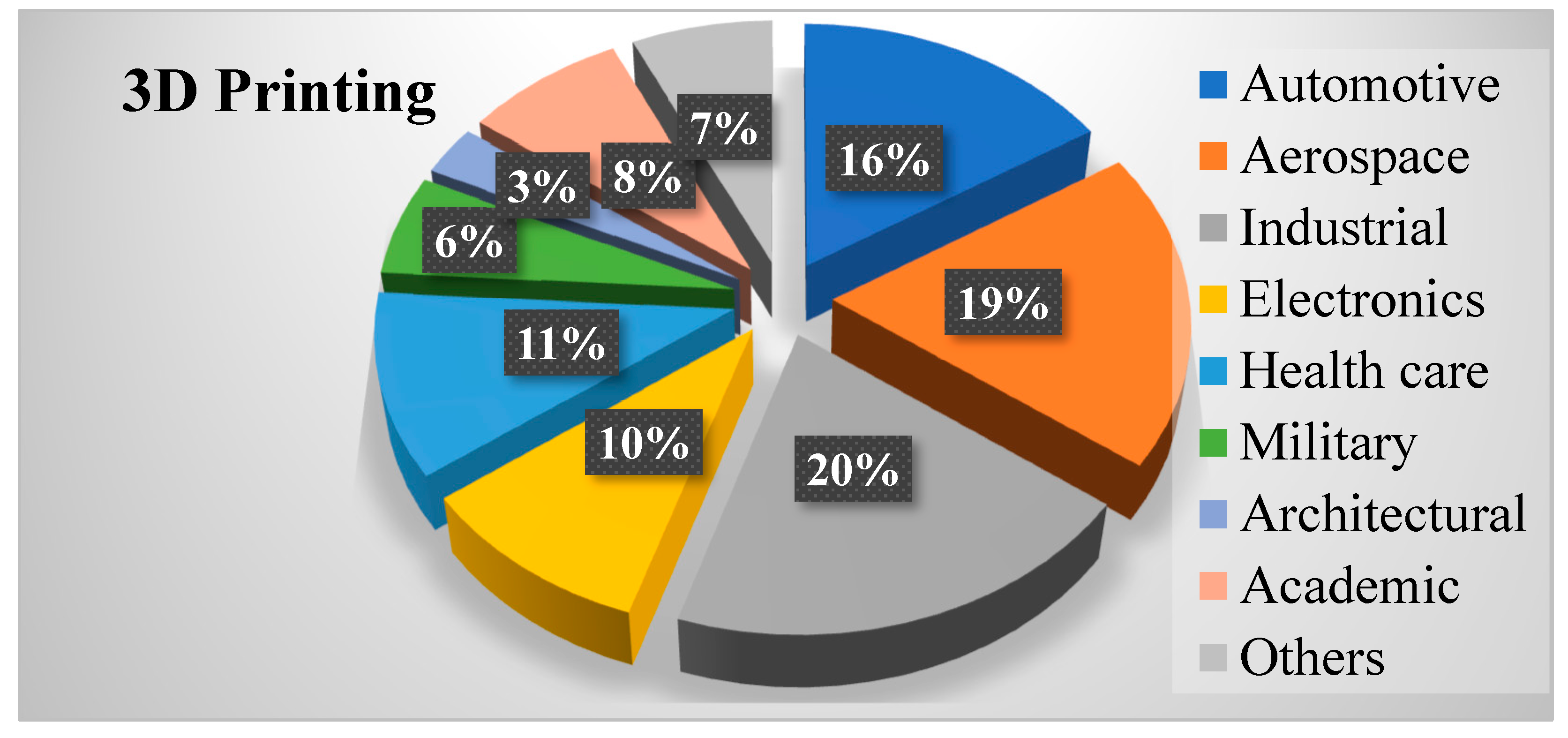

Figure 12.

Shows industries that use 3D printing [

110].

Figure 12.

Shows industries that use 3D printing [

110].

3D printing has found widespread use in a variety of sectors, including automotive, aerospace, biomedicine, and construction. The fast growth of 3D printing technology is projected to continue, with an emphasis on increasing efficiency and lowering prices [

111]. Industries want to reduce manufacturing costs, enabling the development of complex structures from a variety of materials, and extend 3D printing capabilities to obtain quicker and more exact results. These developments cover a broad spectrum of cost-cutting potential, including distribution and production lines, inventory management, and the finished product [

110].

Recent research and projections indicate that additive manufacturing (AM) is gaining traction and might reach a tipping point of general usage within the next decade. Increased investment in 3D printing technology is expected to significantly impact future supply chains. Manufacturing processes may transition from make-to-stock models in offshore or low-cost countries to on-demand manufacturing closer to the end user. This trend may simplify or even abolish existing global supply chains, affecting transportation, freight volumes, and inventory prices. As a result, it is critical to understand the possible impact of 3D printing technology on the transportation business [

110].

Figure 13.

A brief review of common AM techniques [

112].

Figure 13.

A brief review of common AM techniques [

112].

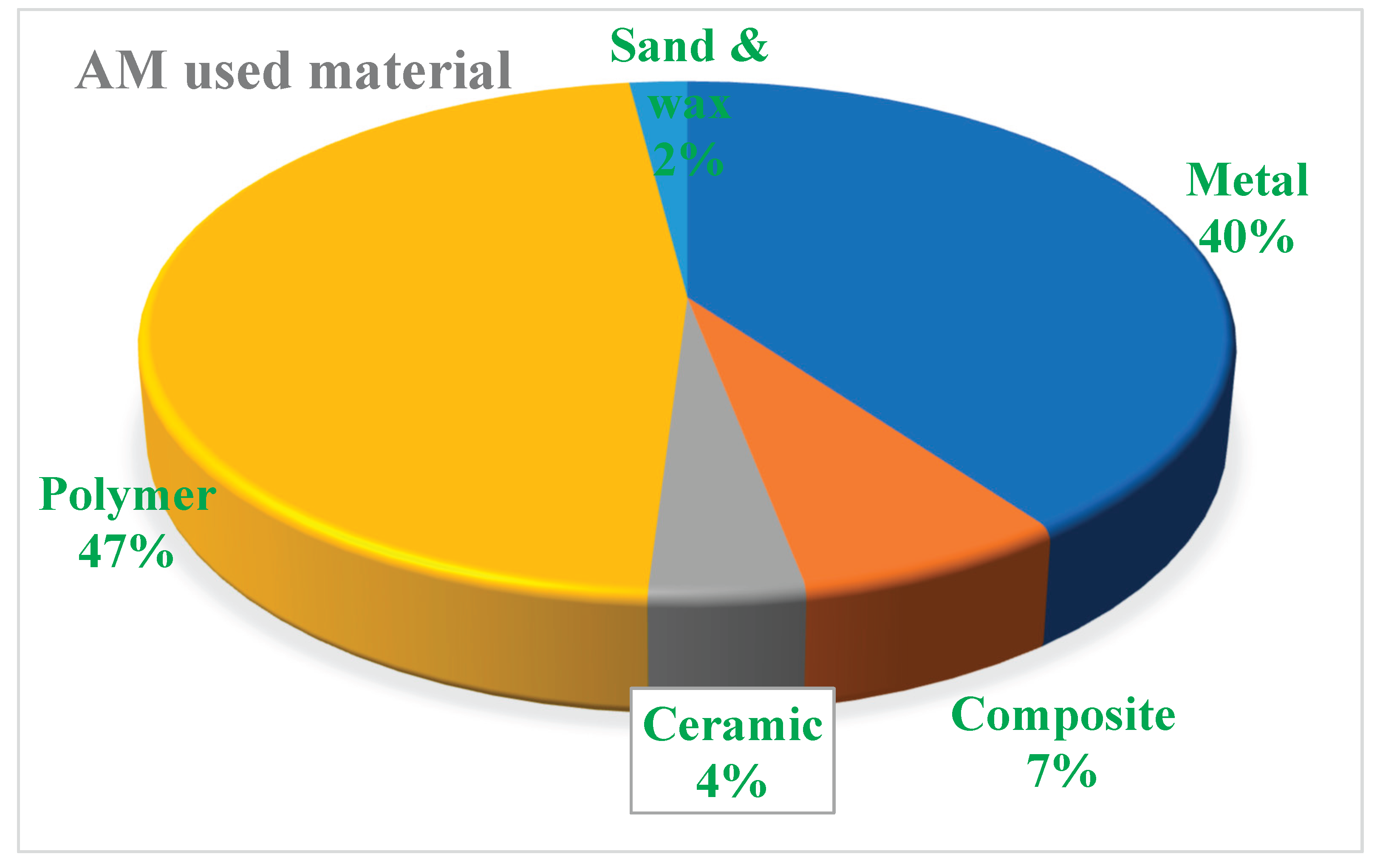

4.6. Contribution of Material Type in AM Techniques

Polymers (47%): Polymers make up the majority of the materials employed in published AM research, accounting for 47% of the total. This supremacy may be due to a broad range of polymer-based 3D printing processes, including fused deposition modelling (FDM), stereo lithography (SLA), and selective laser sintering. Polymers are popular because they are versatile, inexpensive, and suitable for prototyping, biological applications, and consumer items. Metals: 40% Metal-based AM accounts for 40% of all contributions, making it the second most important category. Metals are frequently utilized in high-performance applications, especially in aerospace, automotive, and medical sectors that need strength, endurance, and accuracy [

113]. Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), Directed Energy Deposition (DED), and Binder Jetting are some of the most common metal AM processes. The popularity of metal AM demonstrates its transformational influence on businesses that need sophisticated production capabilities. Composites (7%): Composite materials account for 7% of published research contributions. Composites are made up of multiple materials, such as fibers and polymers, to attain better mechanical qualities like strength-to-weight ratios [

114]. Their poor representation in research might be attributed to the intricacy of mixing materials during the 3D printing process, as well as the need for specialized equipment. Ceramics (4%): Ceramics are a less prevalent topic in AM, accounting for 4% of contributions. Ceramic-based additive manufacturing is utilized in applications that need high heat resistance, biocompatibility, or chemical stability, such as electronics, medical implants, and industrial equipment [

114,

115]. The limited use of ceramics may be due to processing problems such as brittleness and high sintering temperatures. Sand and Wax (2%). Sand and wax account for the lowest amount, at 2%. These materials are typically utilized for specialized applications like investment casting and mold fabrication. Sand-based AM is utilized for large-scale building and mold casting, while wax is mostly used to create patterns in lost-wax casting [

112].

5. Challenges in Metal 3D Printing

5.1. Material Properties and Strength

While metal 3D printing has made significant strides in material development, the mechanical properties of printed parts can still be inconsistent [

73,

113]. Issues like porosity, poor bonding between layers, and uneven microstructure can affect the strength and fatigue resistance of parts. Post-processing techniques like heat treatment and surface finishing are often required to improve the properties, adding complexity to the process [

116].

5.2. High Costs and Equipment Availability

Metal 3D printing systems are typically expensive, with costs ranging from tens of thousands to several million dollars. This upfront investment, coupled with the high cost of materials like metal powders, limits accessibility to smaller manufacturers or research labs. Additionally, many companies are still grappling with the cost-effectiveness of adopting this technology for mass production [

116,

117].

5.3. Post-Processing and Surface Finish

Parts produced through metal 3D printing often require extensive post-processing to meet industry standards for surface finish and mechanical properties. Techniques such as heat treatment, machining, and polishing are commonly used, which can increase both time and cost. Ensuring consistency in these processes remains a significant challenge in the adoption of metal 3D printing for production [

118,

119].

5.4. Certification and Standards

In industries like aerospace and medical devices, parts must adhere to rigorous certification standards. The lack of universally accepted standards for 3D printed metal parts complicates certification processes. Without clear guidelines, manufacturers and regulators face challenges in ensuring the safety, reliability, and quality of printed parts [

119,

120].

6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

6.1. Mass Production Potential

While currently focused on niche applications, there is a growing interest in using metal 3D printing for large-scale production. Researchers and manufacturers are working to improve the speed, scalability, and consistency of additive manufacturing to compete with traditional mass-production methods. This includes innovations such as multi-laser systems and continuous printing processes [

48].

6.2. Hybrid Manufacturing

Hybrid manufacturing, which combines 3D printing with traditional manufacturing techniques (e.g., CNC milling), is an exciting trend. This approach leverages the strengths of both methods, offering high precision and speed while allowing for the production of complex geometries [

121,

122].

6.3. AI and Machine Learning Integration

AI and machine learning are being integrated into metal 3D printing processes to optimize part designs, predict material behaviors, and improve quality control. These advancements are expected to reduce production costs, improve reliability, and enhance the overall efficiency of the manufacturing process [

101,

123].

7. Conclusion

Key Discoveries Summary: Metal 3D printing has gone from being an experimental technology to a widely used production process, and it has been used in a variety of industries. Some of its most important characteristics are the ability to create complex components, minimize material waste, and modify designs. However, there are still challenges such as certification, material properties, and cost. Metal additive manufacturing (AM) has evolved from a prototype tool into a game-changer in industrial production because to its revolutionary design flexibility, material efficiency, and customization capabilities. Metal 3D printing has revolutionized the aerospace, healthcare, and automotive sectors by making it possible to create complicated shapes that could not be made using old processes. Techniques like Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), Directed Energy Deposition (DED), Binder Jetting, and Electron Beam Melting (EBM) make this feasible.

Despite recent improvements, there are still several obstacles that remain, such as the requirement for standardized certification standards, material constraints, surface finish quality, and high production prices. However, due to continuous research and new trends like as AI-driven process optimization, hybrid manufacturing processes, and the development of revolutionary alloys, more scalable, cost-effective, and sustainable solutions are on the way. Improving precision, consistency, and overall efficiency by the use of AI, real-time monitoring, and advanced post-processing procedures may speed the mainstream usage of metal 3D printing for industrial production.

By integrating digital design with real production, metal AM has the potential to change manufacturing in the future. With constant breakthroughs in materials, process control, and automation, the potential for additive manufacturing extends beyond existing applications, suggesting a significant change toward smarter, more flexible, and environmentally friendly production systems. This evaluation underscores the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to overcome present limits and unveil the full potential of metal 3D printing, cementing its role as a cornerstone of next-generation manufacturing.

7.1. Future Recommendations

Looking ahead, advancements in materials, process optimization, and hybrid manufacturing techniques will drive the continued growth of metal 3D printing. As technology matures, it is expected to play a transformative role in industries such as aerospace, automotive, and healthcare, reshaping traditional manufacturing processes and enabling new, innovative designs.

This expanded literature review provides a detailed exploration of metal 3D printing's current landscape, its applications, challenges, and future opportunities. By focusing on emerging technologies, material developments, and industry-specific needs, this review offers a comprehensive and unique perspective on the subject matter.

Author Contributions

Fasil Kebede Tesfaye’s Conceptualization; methodology; resources, writing—original draft preparation. And Abraham Debebe Woldeyohannes (PhD) writing—review and editing, supervision, and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research Review is not funded

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request to the interested researchers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to Addis Ababa Science and Technology University for utilizing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM |

Additive Manufacturing |

| RP |

Rapid Prototyping |

| RM |

Rapid Manufacturing |

| CAM |

Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CAE |

Computer-Aided Engineering |

| PBF |

Powder Bed Fusion |

| SLM |

Selective Laser Melting |

| DMLS |

Direct Metal Laser Sintering |

| EBM |

Electron Beam Melting |

| FDM |

Fused Deposition Modeling |

| SLS |

Selective Laser Sintering |

| DED |

Directed Energy Deposition |

| BJ |

Binder Jetting |

References

- T. Gao, X.-Z. Wang, H.-X. Gu, Y. Xu, X. Shen, and D.-R. Zhu, “Two 3D metal–organic frameworks with different topologies, thermal stabilities and magnetic properties,” CrystEngComm, vol. 14, no. 18, pp. 5905–5913, 2012.

- N. Guo and M. C. Leu, “Additive manufacturing: technology, applications and research needs,” Front. Mech. Eng., vol. 8, pp. 215–243, 2013.

- M. Vaezi, H. Seitz, and S. Yang, “A review on 3D micro-additive manufacturing technologies,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 67, pp. 1721–1754, 2013.

- A. Uriondo, M. Esperon-Miguez, and S. Perinpanayagam, “The present and future of additive manufacturing in the aerospace sector: A review of important aspects,” Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng., vol. 229, no. 11, pp. 2132–2147, 2015.

- J. Guo, J. Yang, Y.-Y. Liu, and J.-F. Ma, “Two novel 3D metal–organic frameworks based on two tetrahedral ligands: Syntheses, structures, photoluminescence and photocatalytic properties,” CrystEngComm, vol. 14, no. 20, pp. 6609–6617, 2012.

- S. C. Joshi and A. A. Sheikh, “3D printing in aerospace and its long-term sustainability,” Virtual Phys. Prototyp., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 175–185, 2015.

- X. Li, X.-Y. Ma, Y.-F. Feng, L. Wang, and C. Wang, “A novel composite scaffold consisted of porous titanium and chitosan sponge for load-bearing applications: Fabrication, characterization and cellular activity,” Compos. Sci. Technol., vol. 117, pp. 78–84, 2015.

- M. Chahal et al., “Personalized oncogenomic analysis of metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma: using whole-genome sequencing to inform clinical decision-making,” Mol. Case Stud., vol. 4, no. 2, p. a002626, 2018.

- N. A. Rosli, M. R. Alkahari, F. R. Ramli, S. Mat, and A. A. Yusof, “Influence of process parameters on dimensional accuracy in GMAW based additive manufacturing,” Proc. Mech. Eng. Res. Day 2019, vol. 2019, pp. 7–9, 2019.

- S. Attarilar, M. Ebrahimi, F. Djavanroodi, Y. Fu, L. Wang, and J. Yang, “3D printing technologies in metallic implants: a thematic review on the techniques and procedures,” Int. J. Bioprinting, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 306, 2020.

- P. Song et al., “Dual modulation of crystallinity and macro-/microstructures of 3D printed porous titanium implants to enhance stability and osseointegration,” J. Mater. Chem. B, vol. 7, no. 17, pp. 2865–2877, 2019.

- A. Al Rashid, S. A. Khan, S. G. Al-Ghamdi, and M. Koç, “Additive manufacturing of polymer nanocomposites: Needs and challenges in materials, processes, and applications,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 14, pp. 910–941, 2021.

- B. Blakey-Milner et al., “Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review,” Mater. Des., vol. 209, p. 110008, 2021.

- H. Bikas, A. K. Lianos, and P. Stavropoulos, “A design framework for additive manufacturing,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 103, pp. 3769–3783, 2019.

- F. W. Liou, “Rapid prototyping processes,” Rapid Prototyp. Eng. Appl. A toolbox prototype Dev., 2007.

- H. Alzyod and P. Ficzere, “Material-dependent effect of common printing parameters on residual stress and warpage deformation in 3D printing: A comprehensive finite element analysis study,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 13, p. 2893, 2023.

- M. Revilla-León and M. Özcan, “Additive manufacturing technologies used for processing polymers: current status and potential application in prosthetic dentistry,” J. Prosthodont., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 146–158, 2019.

- M. Revilla-León, M. Sadeghpour, and M. Özcan, “An update on applications of 3D printing technologies used for processing polymers used in implant dentistry,” Odontology, vol. 108, no. 3, pp. 331–338, 2020.

- B. Wang, S. J. Hu, L. Sun, and T. Freiheit, “Intelligent welding system technologies: State-of-the-art review and perspectives,” J. Manuf. Syst., vol. 56, pp. 373–391, 2020.

- C. Sun, Y. Wang, M. D. McMurtrey, N. D. Jerred, F. Liou, and J. Li, “Additive manufacturing for energy: A review,” Appl. Energy, vol. 282, p. 116041, 2021.

- K. R. Ryan, M. P. Down, and C. E. Banks, “Future of additive manufacturing: Overview of 4D and 3D printed smart and advanced materials and their applications,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 403, p. 126162, 2021.

- W. Tomal, D. Krok, A. Chachaj-Brekiesz, P. Lepcio, and J. Ortyl, “Harnessing light to create functional, three-dimensional polymeric materials: multitasking initiation systems as the critical key to success,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 48, p. 102447, 2021.

- S. Saleh Alghamdi, S. John, N. Roy Choudhury, and N. K. Dutta, “Additive manufacturing of polymer materials: Progress, promise and challenges,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 5, p. 753, 2021.

- P. S. Humnabad, R. Tarun, and I. Das, “An overview of direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) technology for metal 3D printing,” J. Mines, Met. Fuels, pp. 127–133, 2022.

- A. Shah, R. Aliyev, H. Zeidler, and S. Krinke, “A review of the recent developments and challenges in wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) process,” J. Manuf. Mater. Process., vol. 7, no. 3, p. 97, 2023.

- Al Rashid, S. A. Khan, S. G. Al-Ghamdi, and M. Koç, “Additive manufacturing: Technology, applications, markets, and opportunities for the built environment,” Autom. Constr., vol. 118, p. 103268, 2020.

- U. M. Dilberoglu, B. Gharehpapagh, U. Yaman, and M. Dolen, “The role of additive manufacturing in the era of industry 4.0,” Procedia Manuf., vol. 11, pp. 545–554, 2017.

- A. Chadha, M. I. Ul Haq, A. Raina, R. R. Singh, N. B. Penumarti, and M. S. Bishnoi, “Effect of fused deposition modelling process parameters on mechanical properties of 3D printed parts,” World J. Eng., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 550–559, 2019.

- M. I. U. Haq, A. Raina, M. J. Ghazali, M. Javaid, and A. Haleem, “Potential of 3D printing technologies in developing applications of polymeric nanocomposites,” Tribol. Polym. Polym. Compos. Ind. 4.0, pp. 193–210, 2021.

- L. Lü, J. Y. H. Fuh, Y. S. Wong, L. Lü, J. Y. H. Fuh, and Y. S. Wong, “Selective laser sintering,” Laser-induced Mater. Process. rapid Prototyp., pp. 89–142, 2001.

- H. K. Jayant and M. Arora, “Induction heating based 3D metal printing of eutectic alloy using vibrating nozzle,” in Advances in Additive Manufacturing, Modeling Systems and 3D Prototyping: Proceedings of the AHFE 2019 International Conference on Additive Manufacturing, Modeling Systems and 3D Prototyping, July 24-28, 2019, Washington DC, USA 10, Springer, 2020, pp. 71–80.

- A. Ramakrishnan and G. P. Dinda, “Direct laser metal deposition of Inconel 738,” Mater. Sci. Eng. A, vol. 740, pp. 1–13, 2019.

- Gibson, D. Rosen, B. Stucker, I. Gibson, D. Rosen, and B. Stucker, “Directed energy deposition processes,” Addit. Manuf. Technol. 3D printing, rapid prototyping, direct Digit. Manuf., pp. 245–268, 2015.

- M. Javaid and A. Haleem, “Additive manufacturing applications in medical cases: A literature based review,” Alexandria J. Med., vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 411–422, 2018.

- M. Li, W. Du, A. Elwany, Z. Pei, and C. Ma, “Metal binder jetting additive manufacturing: a literature review,” J. Manuf. Sci. Eng., vol. 142, no. 9, p. 90801, 2020.

- H. Chen and Y. F. Zhao, “Process parameters optimization for improving surface quality and manufacturing accuracy of binder jetting additive manufacturing process,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 527–538, 2016.

- I.Gibson et al., “Binder jetting,” Addit. Manuf. Technol., pp. 237–252, 2021.

- S. Waheed et al., “3D printed microfluidic devices: enablers and barriers,” Lab Chip, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 1993–2013, 2016.

- P. Wang, J. Song, M. L. S. Nai, and J. Wei, “Experimental analysis of additively manufactured component and design guidelines for lightweight structures: A case study using electron beam melting,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 33, p. 101088, 2020.

- L. E. Murr et al., “Metal fabrication by additive manufacturing using laser and electron beam melting technologies,” J. Mater. Sci. Technol., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2012.

- A. Jawahar and G. Maragathavalli, “Applications of 3D printing in dentistry–a review,” J. Pharm. Sci. Res., vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 1670–1675, 2019.

- M. Revilla-León and M. Özcan, “Additive manufacturing technologies used for 3D metal printing in dentistry,” Curr. Oral Heal. Reports, vol. 4, pp. 201–208, 2017.

- B.R. Hunde and A. D. Woldeyohannes, “Future prospects of computer-aided design (CAD)–A review from the perspective of artificial intelligence (AI), extended reality, and 3D printing,” Results Eng., vol. 14, p. 100478, 2022.

- M. Piazza and S. Alexander, “Additive manufacturing: a summary of the literature,” 2015.

- M. Jiménez, L. Romero, I. A. Domínguez, M. del M. Espinosa, and M. Domínguez, “Additive manufacturing technologies: an overview about 3D printing methods and future prospects,” Complexity, vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 9656938, 2019.

- S. T. Gobena and A. D. Woldeyohannes, “Comparative review on the application of smart material in additive manufacturing: 3D and 4D printing,” Discov. Appl. Sci., vol. 6, no. 7, p. 353, 2024.

- M. Srivastava, S. Rathee, V. Patel, A. Kumar, and P. G. Koppad, “A review of various materials for additive manufacturing: Recent trends and processing issues,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 21, pp. 2612–2641, 2022.

- S. F. Iftekar, A. Aabid, A. Amir, and M. Baig, “Advancements and limitations in 3D printing materials and technologies: a critical review,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 11, p. 2519, 2023.

- V. Mohanavel, K. S. A. Ali, K. Ranganathan, J. A. Jeffrey, M. M. Ravikumar, and S. Rajkumar, “The roles and applications of additive manufacturing in the aerospace and automobile sector,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 47, pp. 405–409, 2021.

- S. Dhakal, “The Roles and Applications of Additive Manufacturing Technology in the Aerospace Industry,” Int. J. Sci. Res. Multidiscip. Stud. Vol, vol. 9, no. 3, 2023.

- L. Amaya-Rivas et al., “Future trends of additive manufacturing in medical applications: An overview,” Heliyon, 2024.

- M. Rehman et al., “Additive manufacturing for biomedical applications: a review on classification, energy consumption, and its appreciable role since COVID-19 pandemic,” Prog. Addit. Manuf., vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 1007–1041, 2023.

- S. T. Gobena and A. D. Woldeyohannes, “Discover Applied Sciences,” Discover, vol. 6, p. 353, 2024.

- M. Salmi, “Additive manufacturing processes in medical applications,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 191, 2021.

- S. H. Khajavi, J. Partanen, and J. Holmström, “Additive manufacturing in the spare parts supply chain,” Comput. Ind., vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 50–63, 2014.

- Y. Wang et al., “Challenges and solutions for the additive manufacturing of biodegradable magnesium implants,” Engineering, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 1267–1275, 2020.

- A. Haleem and M. Javaid, “3D printed medical parts with different materials using additive manufacturing,” Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 215–223, 2020.

- K.Chua, I. Khan, R. Malhotra, and D. Zhu, “Additive manufacturing and 3D printing of metallic biomaterials,” Eng. Regen., vol. 2, pp. 288–299, 2021.

- R. V. Pazhamannil and P. Govindan, “Current state and future scope of additive manufacturing technologies via vat photopolymerization,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 43, pp. 130–136, 2021.

- Y. Li, C. Su, and J. Zhu, “Comprehensive review of wire arc additive manufacturing: Hardware system, physical process, monitoring, property characterization, application and future prospects,” Results Eng., vol. 13, p. 100330, 2022.

- J.C. Ruiz-Morales et al., “Three dimensional printing of components and functional devices for energy and environmental applications,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 846–859, 2017.

- A. Berman et al., “Additively manufactured micro-lattice dielectrics for multiaxial capacitive sensors,” Sci. Adv., vol. 10, no. 40, p. eadq8866, 2024.

- E. Murr et al., “Fabrication of metal and alloy components by additive manufacturing: examples of 3D materials science,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 42–54, 2012.

- Rane and, M. Strano, “A comprehensive review of extrusion-based additive manufacturing processes for rapid production of metallic and ceramic parts,” Adv. Manuf., vol. 7, pp. 155–173, 2019.

- Q. Hamid et al., “Fabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds using precision extrusion deposition with an assisted cooling device,” Biofabrication, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 34109, 2011.

- Vaezi, G. Zhong, H. Kalami, and S. Yang, “Extrusion-based 3D printing technologies for 3D scaffold engineering,” in Functional 3D tissue engineering scaffolds, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 235–254.

- Galati and, L. Iuliano, “A literature review of powder-based electron beam melting focusing on numerical simulations,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 19, pp. 1–20, 2018.

- G. Prashar, H. Vasudev, and D. Bhuddhi, “Additive manufacturing: expanding 3D printing horizon in industry 4.0,” Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 2221–2235, 2023.

- Fidan, V. Naikwadi, S. Alkunte, R. Mishra, and K. Tantawi, “Energy efficiency in additive manufacturing: condensed review,” Technologies, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 21, 2024.

- F. A. Shah et al., “Long-term osseointegration of 3D printed CoCr constructs with an interconnected open-pore architecture prepared by electron beam melting,” Acta Biomater., vol. 36, pp. 296–309, 2016.

- A. K. Dutt, G. K. Bansal, S. Tripathy, K. Gopala Krishna, V. C. Srivastava, and S. Ghosh Chowdhury, “Optimization of selective laser melting (SLM) additive manufacturing process parameters of 316L austenitic stainless steel,” Trans. Indian Inst. Met., vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 335–345, 2023.

- H. Cai et al., “Dental materials applied to 3D and 4D printing technologies: a review,” Polymers (Basel)., vol. 15, no. 10, p. 2405, 2023.

- V. Korzhyk, V. Khaskin, O. Voitenko, V. Sydorets, and O. Dolianovskaia, “Welding technology in additive manufacturing processes of 3D objects,” in Materials Science Forum, Trans Tech Publ, 2017, pp. 121–130.

- M. Ding et al., “TIG–MIG hybrid welding of ferritic stainless steels and magnesium alloys with Cu interlayer of different thickness,” Mater. Des., vol. 88, pp. 375–383, 2015.

- T. Schonwetter and B. Van Wiele, “3D printing: Enabler of social entrepreneurship in Africa? The roles of FabLabs and low-cost 3D printers,” Cape Town, South Africa Open African Innov. Res. (Open AIR).[Google Sch., 2018.

- D.Aghimien, C. Aigbavboa, L. Aghimien, W. Thwala, and L. Ndlovu, “3D Printing for sustainable low-income housing in South Africa: A case for the urban poor,” J. Green Build., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 129–141, 2021.

- G. Olatunji, O. W. Osaghae, and N. Aderinto, “Exploring the transformative role of 3D printing in advancing medical education in Africa: a review,” Ann. Med. Surg., vol. 85, no. 10, pp. 4913–4919, 2023.

- J.Rydz, A. Šišková, and A. Andicsová Eckstein, “Scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy: topographic and dynamical surface studies of blends, composites, and hybrid functional materials for sustainable future,” Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 6871785, 2019.

- C.Zhang et al., “Mechanical behavior of a titanium alloy scaffold mimicking trabecular structure,” J. Orthop. Surg. Res., vol. 15, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- K.C. McGilvray et al., “Bony ingrowth potential of 3D-printed porous titanium alloy: a direct comparison of interbody cage materials in an in vivo ovine lumbar fusion model,” Spine J., vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 1250–1260, 2018.

- N.Shahrubudin, T. C. Lee, and R. Ramlan, “An overview on 3D printing technology: Technological, materials, and applications,” Procedia Manuf., vol. 35, pp. 1286–1296, 2019.

- S. Bose, D. Banerjee, A. Shivaram, S. Tarafder, and A. Bandyopadhyay, “Calcium phosphate coated 3D printed porous titanium with nanoscale surface modification for orthopedic and dental applications,” Mater. Des., vol. 151, pp. 102–112, 2018.

- R. Ranjan, D. Kumar, M. Kundu, and S. C. Moi, “A critical review on Classification of materials used in 3D printing process,” Mater. today Proc., vol. 61, pp. 43–49, 2022.

- Y. Ding, J. A. Muñiz-Lerma, M. Trask, S. Chou, A. Walker, and M. Brochu, “Microstructure and mechanical property considerations in additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys,” MRS Bull., vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 745–751, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Davis, “Metallic materials,” Handb. Mater. Med. devices, pp. 21–50, 2003.

- S. Attarilar, M. Ebrahimi, F. Djavanroodi, Y. Fu, L. Wang, and J. Yang, “3D printing technologies in metallic implants: a thematic review on the techniques and procedures,” Int. J. Bioprinting, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021.

- J. A. Semba, A. A. Mieloch, and J. D. Rybka, “Introduction to the state-of-the-art 3D bioprinting methods, design, and applications in orthopedics,” Bioprinting, vol. 18, p. e00070, 2020.

- N.Taniguchi et al., “Effect of pore size on bone ingrowth into porous titanium implants fabricated by additive manufacturing: An in vivo experiment,” Mater. Sci. Eng. C, vol. 59, pp. 690–701, 2016.

- T. Swetham, K. M. M. Reddy, A. Huggi, and M. N. Kumar, “A Critical Review on of 3D Printing Materials and Details of Materials used in FDM,” Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol, vol. 3, pp. 353–361, 2017.

- A. Muñoz and M. Costa, “Elucidating the mechanisms of nickel compound uptake: a review of particulate and nano-nickel endocytosis and toxicity,” Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., vol. 260, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2012.

- Q. Chen and G. A. Thouas, “Metallic implant biomaterials,” Mater. Sci. Eng. R Reports, vol. 87, pp. 1–57, 2015.

- S. S. Dimov, D. T. Pham, F. Lacan, and K. D. Dotchev, “Rapid tooling applications of the selective laser sintering process,” Assem. Autom., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 296–302, 2001.

- T. Wang et al., “Microplasma direct writing of a copper thin film in the atmospheric condition with a novel copper powder electrode,” Plasma Process. Polym., vol. 17, no. 8, p. 2000034, 2020.

- H. Ding, B. Zou, X. Wang, J. Liu, and L. Li, “Microstructure, mechanical properties and machinability of 316L stainless steel fabricated by direct energy deposition,” Int. J. Mech. Sci., vol. 243, p. 108046, 2023.

- S. L. Sing, C. F. Tey, J. H. K. Tan, S. Huang, and W. Y. Yeong, “3D printing of metals in rapid prototyping of biomaterials: Techniques in additive manufacturing,” in Rapid prototyping of biomaterials, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 17–40.

- L.E. Murr, “A metallographic review of 3D printing/additive manufacturing of metal and alloy products and components,” Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal., vol. 7, pp. 103–132, 2018.

- M.S. Karkun and S. Dharmalingam, “3D printing technology in aerospace industry–a review,” Int. J. Aviat. Aeronaut. Aerosp., vol. 9, no. 2, p. 4, 2022.

- C. Buchanan and L. Gardner, “Metal 3D printing in construction: A review of methods, research, applications, opportunities and challenges,” Eng. Struct., vol. 180, pp. 332–348, 2019.

- D.W. Martinez, M. T. Espino, H. M. Cascolan, J. L. Crisostomo, and J. R. C. Dizon, “A comprehensive review on the application of 3D printing in the aerospace industry,” Key Eng. Mater., vol. 913, pp. 27–34, 2022.

- D. Carou and D. Carou, “Aerospace transformation through industry 4.0 technologies,” Aerosp. Digit. A Transform. Through Key Ind. 4.0 Technol., pp. 17–46, 2021.

- G.D. Goh, S. L. Sing, and W. Y. Yeong, “A review on machine learning in 3D printing: applications, potential, and challenges,” Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 63–94, 2021.

- Y. W. Adugna, A. D. Akessa, and H. G. Lemu, “Overview study on challenges of additive manufacturing for a healthcare application,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, 2021, p. 12041.

- E. J. Hurst, “3D printing in healthcare: emerging applications,” J. Hosp. Librariansh., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 255–267, 2016.

- L. Tang, A. Saxena, and K. Younsi, “Prognostics and Health Management for Electrified Aircraft Propulsion: State of the Art and Challenges,” J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power, vol. 147, no. 4, 2025.

- Z. Wawryniuk, E. Brancewicz-Steinmetz, and J. Sawicki, “Revolutionizing transportation: An overview of 3D printing in aviation, automotive, and space industries,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 134, no. 7, pp. 3083–3105, 2024.

- S. J. Park, J. E. Lee, J. Park, N.-K. Lee, Y. Son, and S.-H. Park, “High-temperature 3D printing of polyetheretherketone products: Perspective on industrial manufacturing applications of super engineering plastics,” Mater. Des., vol. 211, p. 110163, 2021.

- D. T. Pham et al., “FLXIBLE TOOLING FOR MANUFACTURING 3D PANELS USING MULTI-POINT FORMING METHODLOGY,” in Manufacturing Engineering Centre, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, Conference Paper June, 2008.

- V. K. Tiwary, A. P, and V. R. Malik, “An overview on joining/welding as post-processing technique to circumvent the build volume limitation of an FDM-3D printer,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 808–821, 2021.

- J. E. Márquez-Díaz, “Benefits and challenges of military artificial intelligence in the field of defense,” Comput. y Sist., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 309–323, 2024.

- T. Wohlers, “Wohlers report 2017: 3D printing and additive manufacturing state of the industry: annual worldwide progress report,” (No Title), 2017.

- E. H. C. Fang and S. Kumar, “The trends and challenges of 3D printing,” Adv. Methodol. Technol. Eng. Environ. Sci., pp. 415–423, 2019.

- D. E. Mouzakis, “Advanced technologies in manufacturing 3D-layered structures for defense and aerospace,” Lamination-theory Appl., vol. 74331, 2018.

- Y. M. Zhang, Y.-P. Yang, W. Zhang, and S.-J. Na, “Advanced welding manufacturing: a brief analysis and review of challenges and solutions,” J. Manuf. Sci. Eng., vol. 142, no. 11, p. 110816, 2020.

- T. Jagadeesha, A. K. Gajakosh, A. Malladi, and L. Natrayan, “Advanced 3D Printing for Industrial Components: Welded Joint Analysis and Strength Assessment,” New Mater. Process. Manuf. Fabr. Process. Adv. Mater., pp. 287–297, 2024.

- Z. K. Wani and A. B. Abdullah, “A Review on metal 3D printing; 3D welding,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, 2020, p. 12015.

- M.Doshi, A. Mahale, S. K. Singh, and S. Deshmukh, “Printing parameters and materials affecting mechanical properties of FDM-3D printed Parts: Perspective and prospects,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 50, pp. 2269–2275, 2022.

- M. Irfan Ul Haq et al., “3D printing for development of medical equipment amidst coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic—review and advancements,” Res. Biomed. Eng., pp. 1–11, 2022.

- A. Kantaros, T. Ganetsos, F. I. T. Petrescu, L. M. Ungureanu, and I. S. Munteanu, “Post-Production Finishing Processes Utilized in 3D Printing Technologies,” Processes, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 595, 2024.

- E. Maleki, S. Bagherifard, M. Bandini, and M. Guagliano, “Surface post-treatments for metal additive manufacturing: Progress, challenges, and opportunities,” Addit. Manuf., vol. 37, p. 101619, 2021.

- Z. Chen, C. Han, M. Gao, S. Y. Kandukuri, and K. Zhou, “A review on qualification and certification for metal additive manufacturing,” Virtual Phys. Prototyp., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 382–405, 2022.

- U. M. Dilberoglu, B. Gharehpapagh, U. Yaman, and M. Dolen, “Current trends and research opportunities in hybrid additive manufacturing,” Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 113, pp. 623–648, 2021.

- B. A. Praveena, N. Lokesh, A. Buradi, N. Santhosh, B. L. Praveena, and R. Vignesh, “A comprehensive review of emerging additive manufacturing (3D printing technology): Methods, materials, applications, challenges, trends and future potential,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 52, pp. 1309–1313, 2022.

- Y. Pan and L. Zhang, “Roles of artificial intelligence in construction engineering and management: A critical review and future trends,” Autom. Constr., vol. 122, p. 103517, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).