Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Amniotic Fluid (AF) Sludge and Its Constitution

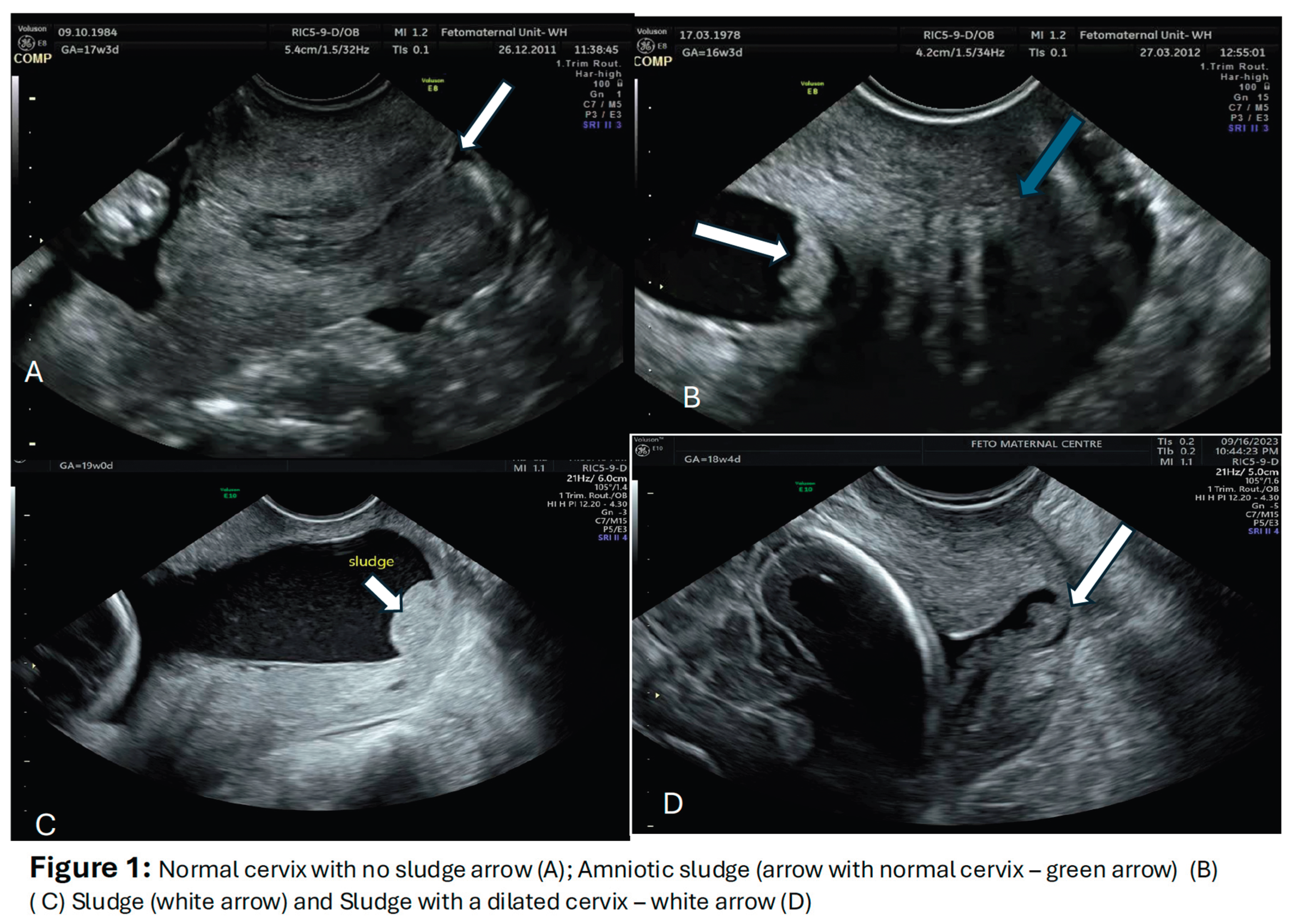

3. Imaging for the AF Sludge

4. The AF Sludge and Intra-Amniotic Infections

5. The AF Sludge and an Ultrasound Marker for Spontaneous Preterm Labour?

6. Will Treatment Improve Outcome?

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D. et al. Born too soon, - the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health 2013; 10(suppl 1):S2)-.

- World Health Organization, Children: improving survival and well-being, 8 Sep 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality, last accessed 23rd December 2024.

- Ahmed B, Abushama M, Konje JC. Prevention of spontaneous preterm delivery - an update on where we are today. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023 Dec;36(1):2183756. [CrossRef]

- Kinney & Rhoda 2019 - Lancet Global Health, Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e37–46.).

- Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, Landoulsi S, Jampathong N, Kongwattanakul K, Laopaiboon M, Lewis C, Rattanakanokchai S, Teng DN, Thinkhamrop J, Watananirun K, Zhang J, Zhou W, Gülmezoglu AM. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Jan;7(1):e37-e46. [CrossRef]

- Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010 Feb 11;362(6):529-35. [CrossRef]

- Preterm labour and birth. NICE Guideline (NG25). Published : 25 November 2015. Last updated : 10 June 2022.

- Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hiler SL, Eschenbach DA. The association of occult amniotic Fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome in women in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecolol 1992;79:351-357).

- Agrawal V, Hirsch E. Intrauterine infection and preterm labor. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Feb;17(1):12-9. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, Avila C, Mazor M, Callahan R, Sabo V, Athanassiadis AP, Hobbins JC. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intraamniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Sep;161(3):817-24. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and why preterm prevention programs have failed. Am J Public Health. 1996 Jun;86(6):781-3. [CrossRef]

- Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiyasit N, Yoon BH, Kim YM. Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;213(4 Suppl):S29-52. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Salafia CM, Athanassiadis AP, Hanaoka S, Mazor M, Sepulveda W, Bracken MB. The relationship between acute inflammatory lesions of the preterm placenta and amniotic fluid microbiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992 May;166(5):1382-8. [CrossRef]

- Lee SM, Park KH, Jung EY, Jang JA, Yoo HN. Frequency and clinical significance of short cervix in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 30;12(3):e0174657. [CrossRef]

- Kiefer DG, Keeler SM, Rust OA, Wayock CP, Vintzileos AM, Hanna N. Is midtrimester short cervix a sign of intraamniotic inflammation? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;200(4):374.e1-5. [CrossRef]

- Cassell GH, Davis RO, Waites KB, Brown MB, Marriott PA, Stagno S, Davis JK. Isolation of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum from amniotic fluid at 16-20 weeks of gestation: potential effect on outcome of pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 1983 Oct-Dec;10(4 Suppl):294-302.

- Daskalakis G, Psarris A, Koutras A, Fasoulakis Z, Prokopakis I, Varthaliti A, Karasmani C, Ntounis T, Domali E, Theodora M, Antsaklis P, Pappa KI, Papapanagiotou A. Maternal Infection and Preterm Birth: From Molecular Basis to Clinical Implications. Children (Basel). 2023 May 22;10(5):907. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, Chaemsaithong P, Gotsch F, Dong Z, Ahmed AI, Yoon BH, Hassan SS, Kim CJ, Korzeniewski SJ, Yeo L. A novel molecular microbiologic technique for the rapid diagnosis of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and intra-amniotic infection in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014 Apr;71(4):330-58. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza J, Gonçalves LF, Romero R, Nien JK, Stites S, Kim YM, Hassan S, Gomez R, Yoon BH, Chaiworapongsa T, Lee W, Mazor M. The prevalence and clinical significance of amniotic fluid 'sludge' in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Apr;25(4):346-52. [CrossRef]

- Benacerraf BR, Gatter MA, Ginsburgh F. Ultrasound diagnosis of meconium-stained amniotic fluid. AmJ Obstet Gynecol 1984;149:570–572. [CrossRef]

- DeVore GR, Platt LD. Ultrasound appearance of particulate matter in amniotic cavity: vernix or meconium? J Clin Ultrasound 1986;14:229–230.

- Sepulveda WH, Quiroz VH. Sonographic detection of echogenic amniotic fluid and its clinical significance. J Perinat Med 1989;17:333–335.

- Sherer DM, Abramowicz JS, Smith SA, Woods JR Jr. Sonographically homogeneous echogenic amniotic fluid in detecting meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78:819–822.

- Vohra N, Rochelson B, Smith-Levitin M. Three-dimensional sonographic findings in congenital (harlequin) ichthyosis. J Ultrasound Med 2003;22:737–739. [CrossRef]

- Bujold E, Pasquier JC, Simoneau J, Arpin MH, Duperron L, Morency AM, Audibert F. Intra-amniotic sludge, short cervix, and risk of preterm delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006 Mar;28(3):198-202. [CrossRef]

- Adanir I, Ozyuncu O, Gokmen Karasu AF, Onderoglu LS. Amniotic fluid "sludge"; prevalence and clinical significance of it in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018 Jan;31(2):135-140. [CrossRef]

- Parulekar SG. Ultrasonographic demonstration of floating Ultrasonographic demonstration of floating particles in amniotic fluid. J Ultrasound Med 1983; 2: 107–110.

- Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Romero R, Gonçalves LF, Nien JK, Soto E, Khalek N, Camacho N, Hendler I, Mittal P, Friel LA, Gotsch F, Erez O, Than NG, Mazaki-Tovi S, Schoen ML, Hassan SS. Clinical significance of the presence of amniotic fluid 'sludge' in asymptomatic patients at high risk for spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Oct;30(5):706-14. [CrossRef]

- Bearfield C, Davenport ES, Sivapathasundaram V, Allaker RP. Possible association between amniotic fluid microorganism infection and microflora in the mouth. BJOG. 2002; 109(5):527– 33.

- Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in the Amniotic Cavity of Women with Intra-Amniotic Infection: A New Mechanism of Host Defense. Reprod Sci. 2017; 24(8):1139-1153. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Lopez N, Romero R, Garsia-Flores V , et al. Amniotic fluid neutrophils can phagocytize bacteria: A mechanism for microbial killing in the amniotic cavity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017; 78(4):. [CrossRef]

- Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010; 10(12):826–37. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of sterile intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014; 72(5):458–74. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Miranda J, Chaemsaithong P, et al. Sterile and microbial-associated intra- amniotic inflammation in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Sterile intra- amniotic inflammation in asymptomatic patients with a sonographic short cervix: prevalence and clinical significance. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, Nhan-Chang CL, Erez O, Kim CJ, Khalek N, Mittal P, Goncalves LF, Schaudinn C, Hassan SS, Costerton JW. What is amniotic fluid 'sludge'? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Oct;30(5):793-8. [CrossRef]

- Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms.Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15:167–193. [PubMed: 11932229]. [CrossRef]

- Costerton W, Veeh R, Shirtliff M, Pasmore M, Post C, Ehrlich G. The application of biofilm science to the study and control of chronic bacterial infections. J Clin Invest 2003;112:1466–1477. [CrossRef]

- Donlan RM. Role of biofilms in antimicrobial resistance. ASAIO J 2000;46:S47–S52. [CrossRef]

- Jensen ET, Kharazmi A, Lam K, Costerton JW, Hoiby N. Human polymorphonuclear leukocyte response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in biofilms. Infect Immun 1990;58:2383–2385. [CrossRef]

- Jensen ET, Kharazmi A, Hoiby N, Costerton JW. Some bacterial parameters influencing theneutrophil oxidative burst response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. APMIS 1992;100:727–733. [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka AR, Mattar R, Kawanami TE, França MS, Rolo LC, Nomura RM, Araujo Júnior E, Nardozza LM, Moron AF. Amniotic fluid "sludge" is an independent risk factor for preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(1):120-5. [CrossRef]

- Romero R , Kusanovic JP, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, Nhan-Chang CL. Erez O, Kim CJ, Khalek N, Mittal P, Goncalves LF, Schaudinn C, Hassan SS, Costerton JW. What is amniotic fluid sludge? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;30:793-398.

- Yoneda N, Yoneda S, Niimi H, Ito M, Fukuta K, Ueno T, Ito M, Shiozaki A, Kigawa M, Kitajima I, Saito S. Sludge reflects intra-amniotic inflammation with or without microorganisms. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018 Feb;79(2). [CrossRef]

- Kusanovic JP, Jung E, Romero R, Mittal Green P, Nhan-Chang CL, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Kim CJ, Gonçalves LF, Espinoza J, Mazaki-Tovi S, Chaiworapongsa T, Diaz-Primera R, Yeo L, Suksai M, Gotsch F, Hassan SS. Characterization of amniotic fluid sludge in preterm and term gestations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022 Dec;35(25):9770-9779. [CrossRef]

- Gill, N.; Romero, R.; Pacora, P.; Tarca, A.L.; Benshalom-Tirosh, N.; Pacora, P.; Kabiri, D.; Tirosh, D.; Jung, E.J.; Yeo, L.; et al. 467:Patients with Short Cervix and Amniotic Fluid Sludge Delivering ≤32 Weeks Have Stereotypic Inflammatory Signature. Am. J.Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, S312. [CrossRef]

- Paules C, Moreno E, Gonzales A, Fabre E, González de Agüero R, Oros D. Amniotic fluid sludge as a marker of intra-amniotic infection and histological chorioamnionitis in cervical insufficiency: a report of four cases and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(16):2681-4. [CrossRef]

- Ventura W, Nazario C, Ingar J, Huertas E, Limay O, Castillo W. Risk of impending preterm delivery associated with the presence of amniotic fluid sludge in women in preterm labor with intact membranes. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;30(2):116-21. [CrossRef]

- Himaya E, Rhalmi N, Girard M, Tétu A, Desgagné J, Abdous B, Gekas J, Giguère Y, Bujold E. Midtrimester intra-amniotic sludge and the risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Perinatol. 2011 Dec;28(10):815-20. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa JP, Ruiz CM, Medina TB, Rascin AG, del GalloJ, de la Fuente JL, Alonso MJT. Amniotic sludge and short cervix as inflammation and intraamniotic infection markers Obstet Gynecolo Int J 2017;7:00239. [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda WH, Quiroz VH. Sonographic detection of echogenic amniotic fluid and its clinical significance. J Perinat Med 1989; 17: 333–335.

- Sherer DM, Abramowicz JS, Smith SA, Woods JR, Jr. Sonographically homogeneous echogenic amniotic fluid in detecting meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 78:819–822.

- Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Ultrasonic features of intraamniotic ‘unidentified debris’ at 14–16 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1996; 7: 178–181. 2.

- Tsunoda Y, Fukami T, Yoneyama K, Kawabata I, Takeshita T. The presence of amniotic fluid sludge in pregnant women with a short cervix: an independent risk of preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Mar;33(6):920-923. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda S, Tanaka M, Kyozuka H, Suzuki S, Yamaguchi A, Nomura Y, Fujimori K. Association of amniotic fluid sludge with preterm labor and histologic chorioamnionitis in pregnant Japanese women with intact membranes: A retrospective study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020 Jan;46(1):87-92. [CrossRef]

- Pahlavan, F.; Niknejad, F.; Irani, S.; Niknejadi, M. Does Amniotic Fluid Sludge Result in Preterm Labor in Pregnancies after Assisted Reproduction Technology? A Nested Case—Control Study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 7153–7157. [CrossRef]

- Cuff RD, Carter E, Taam R, Bruner E, Patwardhan S, Newman RB, Chang EY, Sullivan SA. Effect of Antibiotic Treatment of Amniotic Fluid Sludge. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Feb;2(1):100073. [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka AR, Franca MS, Hamamoto TENK, Rolo LC, Mattar R, Moron AF. Antibiotic treatment for patients with amniotic fluid "sludge" to prevent spontaneous preterm birth: A historically controlled observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019 Sep;98(9):1157-1163. [CrossRef]

- Pustotina O. Effects of antibiotic therapy in women with the amniotic fluid "sludge" at 15-24 weeks of gestation on pregnancy outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Sep;33(17):3016-3027. [CrossRef]

- Jin W H, Ha Kim Y, Kim J W, Kim T Y, Kim A, Yang Y. Antibiotic treatment of amniotic fluid “sludge” in patients during the second or third trimester with uterine contraction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153(01):119–124.

- Giles ML, Krishnaswamy S, Metlapalli M, Roman A, Jin W, Li W, Mol BW, Sheehan P, Said J. Azithromycin treatment for short cervix with or without amniotic fluid sludge: A matched cohort study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2023 Jun;63(3):384-390. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs F, Boucoiran I, Picard A, Dube J, Wavrant S, Bujold E, Audibert F. Impact of amniotic fluid "sludge" on the risk of preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015 Jul;28(10):1176-80. [CrossRef]

- Yeo L, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Para R, Johnson J, Kmak D, Jung E, Yoon BH, Hsu CD. Resolution of acute cervical insufficiency after antibiotics in a case with amniotic fluid sludge. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022 Dec;35(25):5416-5426. [CrossRef]

- Sapantzoglou I, Pergialiotis V, Prokopakis I, Douligeris A, Stavros S, Panagopoulos P, Theodora M, Antsaklis P, Daskalakis G. Antibiotic therapy in patients with amniotic fluid sludge and risk of preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024 Feb;309(2):347-361. [CrossRef]

- Pannain GD, Pereira AMG, Rocha MLTLFD, Lopes RGC. Amniotic Sludge and Prematurity: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2023 Aug;45(8):e489-e498. [CrossRef]

- Luca ST, Săsăran V, Muntean M, Mărginean C. A Review of the Literature: Amniotic Fluid "Sludge"-Clinical Significance and Perinatal Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2024 Sep 7;13(17):5306. [CrossRef]

| Study details (authors and Year) | Type of study | Population studied and gestation at study | Method of investigation | Principal findings | Organisms isolated from culture/PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espinoza et al. 2005 [19] | Retrospective | 84 women in preterm labour at 20-35 weeks or 298 in term labour. | Amniocentesis of the preterm group (N=84) for culture. 19 had a sludge and 65 did not. Histological examination of chorion-amnion and placenta | Histological chorioamnionitis in those with and without sludge. 77.8% (14/18) vs 19% (11/58); p<0.001 and positive AF culture 33.3% (6/18) vs 2.5% (1/40); p=0.003 | Ureplasma urealyticum, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Candida albicans, Peptostreptococcus spp, Gardnerella vaginalis |

| Kusanovic et al. 2007 [28] | Retrospective case control | 281 asymptomatic women at 13-29 weeks with a short cervix | 66 had a sludge and 215 did not. Amniocentesis performed on 51 (23 with sludge and 28 without) for AF culture and WBC in AF of >50 cells/mm3 Histology of membranes and cord |

MIAC rates of 21.7% (5/23) in AF sludge vs 0% (0/28) in non-sludge group and 27.3% (6/23) vs 3.6% (1/28) for intra-amniotic inflammation | Urealasma urealyticum, Staphylococcus aureus and Fusobacterium nucleatum |

| Himaya et al. 2011 [49] | Prospective | 310 women undergoing karyotyping by amniocentesis at 14-24 weeks | Quantification of amniotic fluid concentration of MMP-8 (MMP-8), glucose and lactate from 310 women (94 with free floating particles; 19 with dense amniotic sludge and 200 with no particles/no sludge). CL normal in all cases except 1 with a CL of <15mm | No significant differences in MMP-8, lactate and glucose in the groups. No differences in markers of MIAC in all groups. Woman with CL<15mm had higher MMP-8, and lower glucose. 2 women who delivered <32 weeks had higher mean lactate | Staphylococcus warneri in one case |

| Ventura et al. 2011 [48] | Retrospective case control | 58 women in preterm labour at 22-34 weeks. |

Two groups - 16 with sludge and 42 without. Histological examination and Histological chorioamnionitis was based on the presence of inflammatory cells in the chorionic plate and/or chorioamniotic membranes. |

No difference in histological chorioamnionitis between those with and without sludge (18.8% vs 14.3; p=0.067) | Organisms not characterised |

| Paules et al. 2016 [47] | Case report at 21-24 weeks | 4 cases of cervical weakness and bulging membranes with an amniotic fluid sludge | Amniocentesis in 3/4 cases (one of the cases refused amniocentesis) | All had histological chorioamnionitis and 2 had funisitis | Fusobacterium nucleatum (in 2/3 cdases) |

| Pedregosa et al. 2017 [50] | Retrospective & Prospective | Asymptomatic/symptomatic women with a short CL <25mm at 16-32 weeks | Amniocentesis in 15 cases - 12 with sludge. PCR, culture, gram stain and WBC and glucose level Microbiological study of placenta, membranes and umbilical cord |

From 15 amnios, 8 had MIAC and 6 with sterile inflammation (without any isolated organism) and 1 negative 10 positive cultures of placenta, membranes & cord |

Genital mycoplasma (Ureaplasma urealyticium, Mycomplasma hominis - most common organisms |

| Yoneda et al. 2017 [44] | Retrospective | 105 women in preterm labour at 20-29 weeks | Amniocentesis from 105 women in preterm labour (19 with sludge and 86 without) for culture, PCR (Positive AF cultures -examined using a nucleotide sequence- based analysis of bacterial genome DNA or 16S rRNA metagenomics) and IL-8 and placental histology of placenta. |

Women with vs without sludge PCR - no difference 31.6% (6/19) vs 38.4% (33/86) P>0.05 Funisitis 31.6% (6/10) vs 23.2% (20/86), p=0.447 Histological chorioamnionitis 52.6%(10/19) vs 23.3% - P=0.01 IL-8 - 15.2ng/ml vs 5.8ng/ml; P=0.005 |

Streptococcus parvum, Streptococcus agalactiae, Ureaplasma parvum, Flavobacterium succinicans, Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| Gill et al. 2019 [46] | Cohort | 62 asymptomatic women with a short cervix (≤25mm) at 16-22 weeks | Amniocentesis for concentrations of 33 proteins and histological examination of chorioamnion. Cohort was divided into those who delivered ≤ 32 weeks (35) and those who delivered >32 weeks (27) and variables compared (>1.5fold change in protein concentration considered significant) |

Intra-amniotic inflammatory rate higher in <32 weeks group (31.4% vs 3.7%; p=0.008); acute histological chorioamnionitis greater (75% vs 32%; p=0.002); higher mean concentration of 8/13 proteins - with IL-8 showing the highest difference (4.1 fold) | No organisms investigated |

| Authors and Year of Study | Type of study | Population studied and gestation of study | Cervical assessment | Outcome -in terms of rates/risk of preterm birth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espinoza et al. 2005 [19] | Retrospective | Women recruited at 20-35 weeks who went into preterm labour (N=84) and delivered at term controls (N=298) Sludge present in 19 of the preterm cohort (i.e. 19/84) |

CL ≤ 25mm in all those with sludge (19) and 49/65 of those without | Risk of PTB significantly greater in those with sludge at 48 hours, 7 days of delivery from diagnosis and at 32 and 35 weeks: by 48 hrs - 42.9% vs 4.4% by 7 days - 71.4% vs 15.6% <32 weeks 75.0 vs 25.8% <35 weeks 92.9% vs 37.8% |

| Burjold et al. 2006 [25] | Retrospective | 89 women at risk of preterm birth recruited for cervical length measurement at 18-32 weeks’ gestation-14 with sludge and 75 without | CL significantly shorter in those with sludge - 34.0±10 in those with no sludge vs 23±11 and 16±14 in those with light and dense sludge | Spontaneous PTB in <34 weeks - 8/9 (88.9%) vs 5/75 (6.7%) in those with and without sludge |

| Kusanovic et al. 2007 [28] | Retrospective case-control | 281 patients between 13 and 29 weeks-Sludge N=66, controls N=216 | Cervical length measured and groups into <5mm, <15mm, <25mm and >30mm | Sludge present in 69% (20/29), 49% (33/68), 35% (49/142) and 12% (12/99) respectively for CL<5mm, <15mm; <25mm & >30mm Spontaneous PTB - no sludge vs sludge - <28 weeks 9.4%vs 54.3%; <32 weeks 14.6% vs 60% & <35 weeks - 19.8% vs 42.3% Odd of SPTB if combined sludge and CL<25mm - 14.8for delivery <28 weeks and 9.9 for delivery <35 weeks |

| Ventura et al. 2011 [48] | Retrospective cohort | 58 women with threatened preterm labour at 22-34 weeks - 16 with amniotic fluid sludge and 42 without | Of the 16 with AFS, 75% had CL ≤25mm & 37.5% CL≤15mm |

SPTB greater in those with AFS 25% vs 2.4 within 48 hours 37.5% vs 11.9% within 7 days 75% vs 23.9% within 14 days USS to delivery interval 21.7+_30.1 vs 49.4+137.8 days |

| Hatanaka et al. 2016 [42] | Prospective cohort | 195 women at 16-26 weeks, 49 with sludge and 146 without | CL<25mm - 38.8% 19/49 (sludge) vs 17.5% (23/146) | Gestational age at delivery in sludge vs no sludge group - 35.8+_5.4 weeks vs 37.8+_3.6 weeks SPTB rates differed at up to <35 weeks (at<28 weeks - 12.2% vs 3.4%; at<32 weeks - 17.1% vs 5.1% & at<35 weeks 26.8% vs 8.5%) |

| Adanir et al. 2018 [26] | Prospective | 92 women at high risk of preterm delivery between 20-34 weeks';-18 with sludge and 74 without | CL≤25mm in 8/18 (sludge) vs 9/74 (no sludge) | SPTB rate of 66.7% in those with sludge vs 27% (20/74) in those without sludge |

| Tsunoda et al. 2020 [54] | Retrospective cohort | 110 patients at 14-30 weeks - TVS measurement of cervical length and sludge. 29 with sludge and 81 without | 29 delivered <34 weeks and 51<37 weeks. 16/29 and 21/51 had sludge. CL<20mm - 24/29 vs 33/51 and <15mm - 17/29 vs 21/51 | Risk of SPTB increased with the presence of AFS Odd ratio for delivery <35 weeks - 6.44 and <37 week - 4.46 |

| Yasuda et al. 2020 [55] | Retrospective | 54 women presenting in preterm labour at 22-36+6 weeks. Cervical length measured and sludge identified | Sludge present in 11 cases | AFS cohort delivered at 28.3±4.5 weeks vs 31.7±4.3 weeks |

| Pahlavan et al. 2022 [56] | Nested case control | 110 women who underwent ART in the form of IVF-ET - 63 with sludge and 67 without | CL<30mm in control group - 10.4% and 28.6% in the study groups | SPTB prevalence of 23.6% in case and 10.4% in control |

| Suff et al. 2023 [57] | retrospective cohort | 147 women - 54 with sludge and 93 without | Women with the sludge more likely to have a short CL (19mm vs 14mm) | Women with AFS + short CL, more likely to have a mid-trimester loss and delivery <24 weeks (RR 3.4; 95%CI 3.4-12-20.3) |

| Authors and year of study | Type of study | No of cases studied included | Antibiotic regimen and duration | Outcome (in terms of risk of preterm birth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuchs et al. 2014 [62] | Retrospective case control | 77 asymptomatic women at 15-32 weeks - 63 Rx and 14 untreated Cervical length measured |

Azithromycin 500 mg on day 1 and then 250 mg IV and oral for 4 days | Overall SPTB rates - 57% (36/63) vs 29% (4/14) , P=0.05 in the treated and untreated groups; PTB<28 weeks - 11.1%vs 28.6 P=0.1 PTB<32 weeks - 17.5%vs42.9% - P=0.07 PTB<34 weeks - 19.1% vs 57.1% P=0.006 Conclusion: Use of azithromycin reduced the risk of PTB <34 weeks |

| Hatanaka et al. 2019 [58] | Observational historical controlled | Cohort of 86 - 64 asymptomatic diagnosed with AFS at 16-26 weeks (divided into high and low risk) and 22 controls with AFS Cervical length measured |

Two groups High risk (CL<25mm/other risk factors) IV clindamycin+ ceftazolin for 5 days and then oral for 5 days Low risk CL>25mm Clindamycin (oral) + cephalexin for 7 days - low risk group |

Risk of SPTB <34 weeks in high-risk group - 13.2% vs 38.5% (P=0.047) in treated vs untreated No difference in SPTB rate at all gestations in both groups together (i.e. combined high and low risk - r=treated vs untreated) Conclusion: In high risk group, antibiotics reduce risk of SPTB <34 weeks |

| Cuff et al. 2020 [57] | Retrospective cohort | 97 asymptomatic women with AFS diagnosed at 15-25 weeks- 51 treated and 46 untreated CL measured in both groups |

Mixed treatment 46 Rx with oral Azithromycin x5 days 5 Rx with oral Moxifloxacin x 5 days |

Overall SPTB rate <37 weeks- 49.5% and 22.7% <28 weeks CL measurements same in treated and untreated groups SPTB <37 weeks - 53% vs 45.7% in treated vs untreated (P=0.47) SPTB <228 weeks - 21.6% vs 19.6% (P=0.81) Conclusion: Treatment made no difference in outcome |

| Pustotina 2019 [59] | Prospective | 29 asymptomatic women with AFS diagnosed at 14-24 weeks divided into three groups 14 with CL<25mm & symptomatic 7 with Cl >25mm and asymptomatic 8 with CL>25mm |

All 29 received Vaginal clindamycin and probiotics and plus 16- IV cefoperazone/sulbactam 8 - oral amoxicillin/clavulanate IV butoconazole to 18 Progesterone and indomethacin given to all those with CL<25mm |

Intravenous antibiotics prevented SPTB in all women with CL>25mm and. asymptotic women with CL<25mm and 70% in those with symptoms and CL<25mm Conclusion: Intravenous antibiotics delayed delivery or prevented SPTB |

| Jin et al. 2021 [60] | Retrospective cohort | 58 women at 15-32 weeks symptomatic women with intact membranes and AFS | IV Ceftriaxone 1 g daily, Clarithromycin 500 mg BD orally and metronidazole 500 mg tds - all for 4 weeks | AFS disappeared in 30/58 (51.7%) USS to delivery interval - 67.7+-35.7 days vs 28.4+-35.7 in those without AFS and with persisting AFS after treatment SPTB <28, <32 & <34 weeks was greater in the persistent group Conclusion: Antibiotics may cause AFS to disappear in women presenting in PTL and this is associated with improved outcome |

| Giles et al. 2023 [61] | Retrospective cohort | 374 asymptomatic high-risk women at 13-24 weeks and CL ≤ 15mm - 129 Rx and 245 not Rx Cervical cerclage. performed on >60% of cases and vaginal progesterone given to most |

Azithromycin - IV or oral or both for 7 days | SPTB rates - 51.2% vs 50.6% in the azithromycin and un-treated groups No difference in SPTB <28, <34 weeks and PPROM. Conclusion: The data do no support the routine use of azithromycin in women with a short cervix and AFS |

| Yeo et al 2021 [63] | Case report | Symptomatic woman presenting at 20+6 weeks and sludge - treatment started at 22 weeks | Short cervix, amniocentesis (sterile inflammation), 11 days treatment with IV ceftriaxone (1 gm daily), IV metronidazole 500 mg 8 hourly and oral Clarithromycin 500 mg daily for up | Short cervix progressively became normal and sludge disappeared. Elective delivery at 36+2 weeks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).