Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

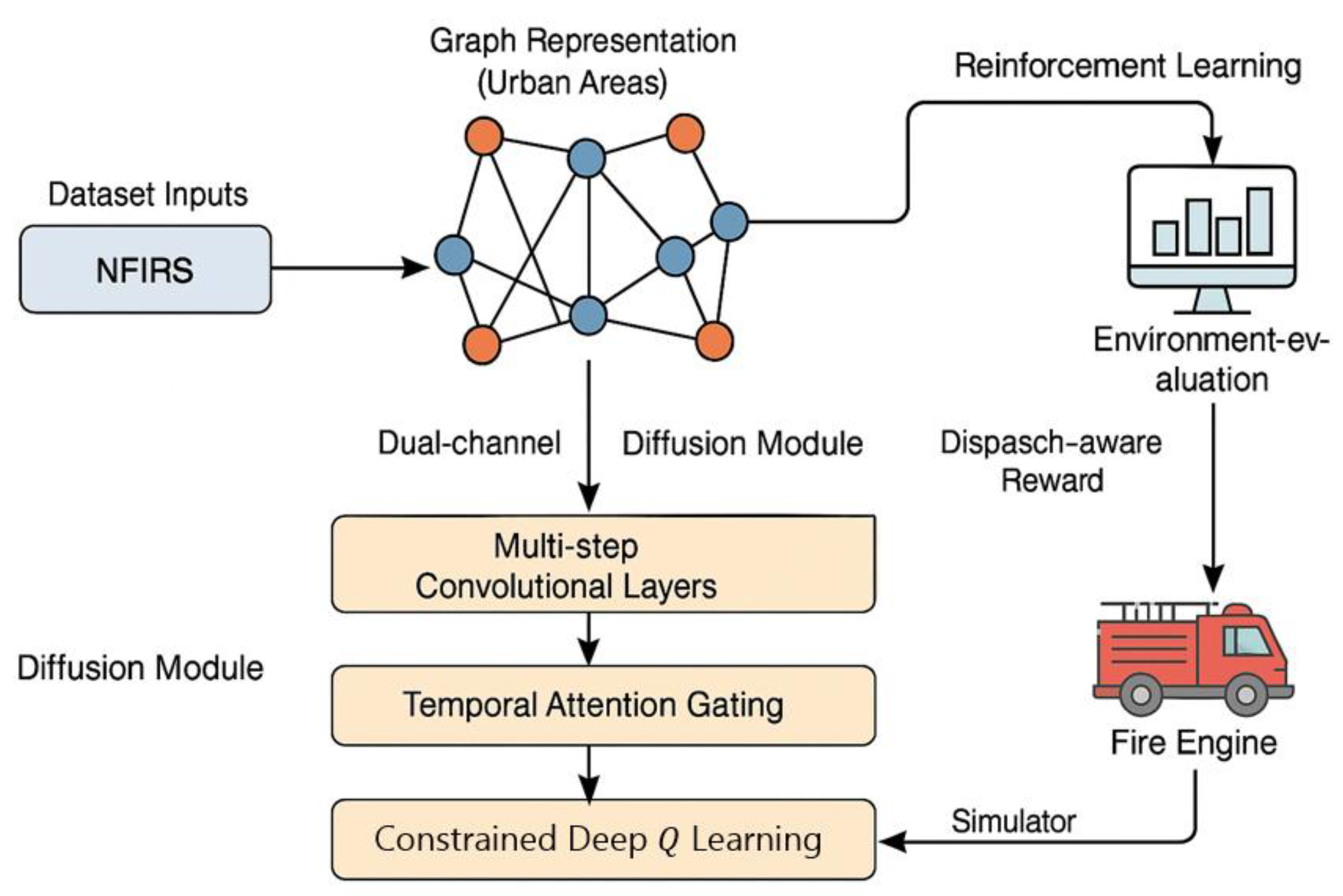

3. Methodologies

3.1. Model Construction and Proliferation Mechanisms

3.2. Scheduling Optimization Mechanism

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

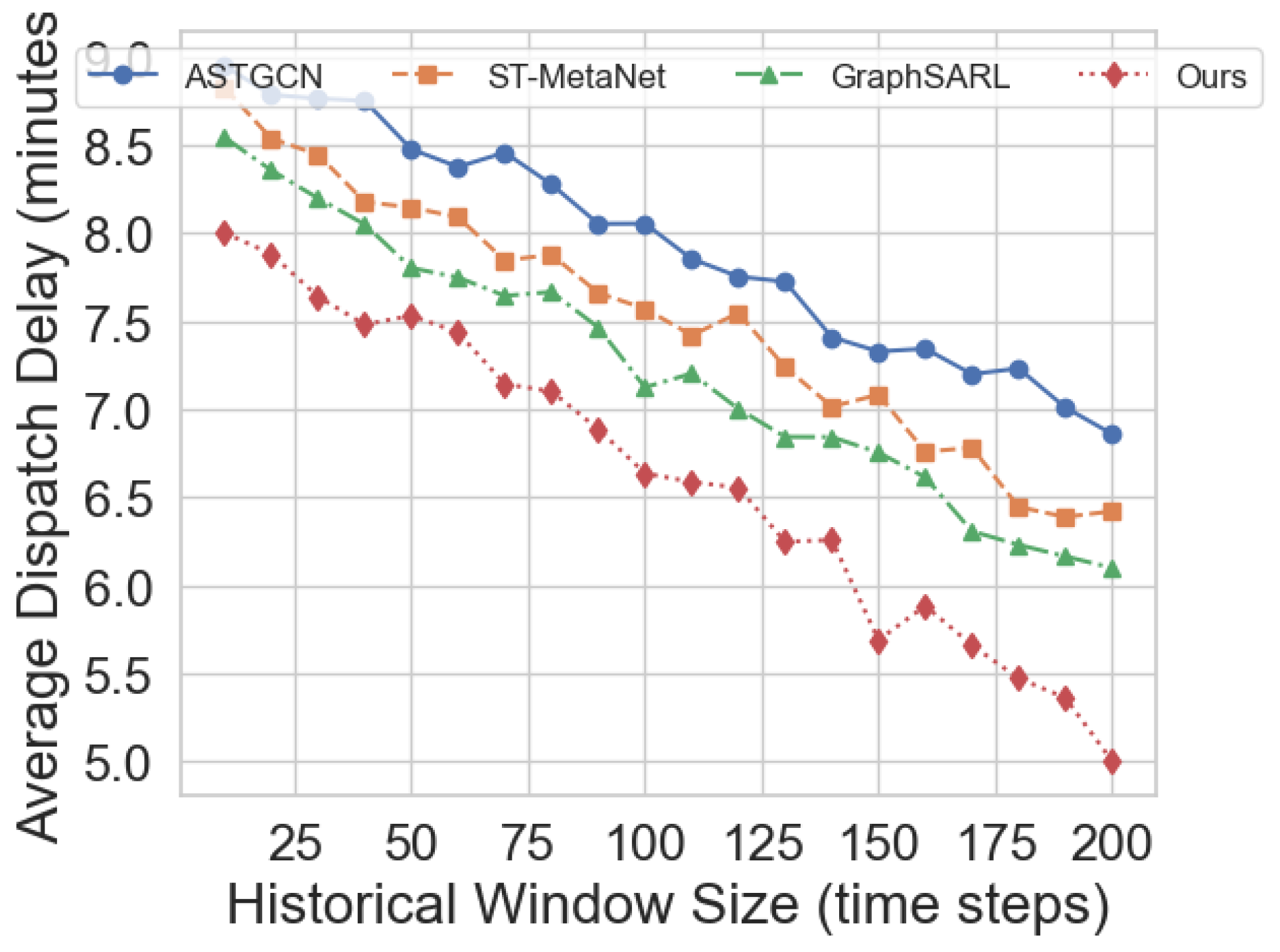

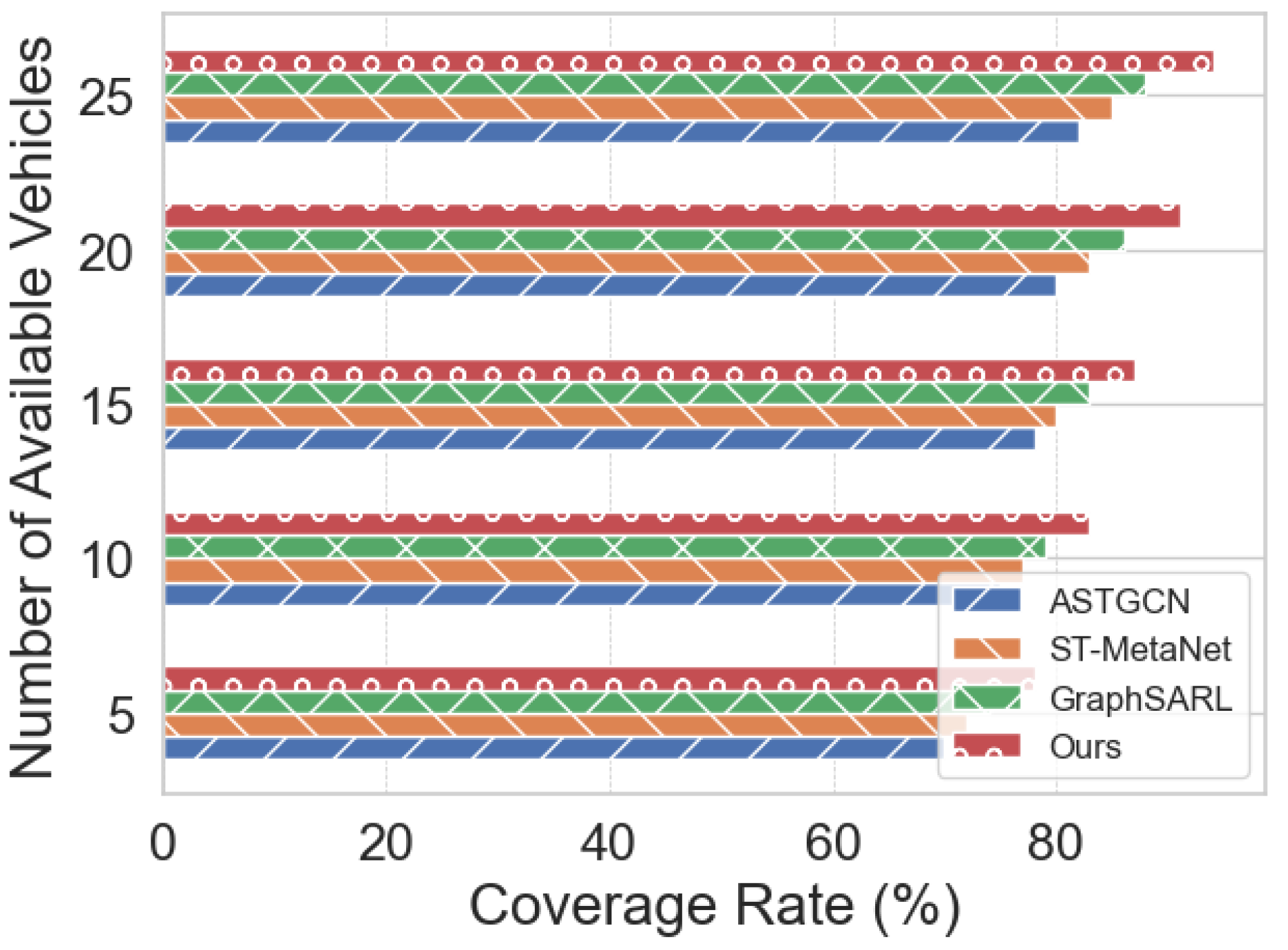

4.2. Experimental Analysis

5. Conclusion

References

- Momeni, M.; Soleimani, H.; Shahparvari, S.; Afshar-Nadjafi, B. Coordinated routing system for fire detection by patrolling trucks with drones. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Ren, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X. Multi-objective scheduling of priority-based rescue vehicles to extinguish forest fires using a multi-objective discrete gravitational search algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Design and Development of Comprehensive Collaborative Dispatching and Disposal System for Urban Frequent Emergency. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, S.; Jin, C. Research on Urban Fire Station Layout Planning Based on a Combined Model Method. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2023, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidich, Y.; Földes, D.; Galkin, A. Enhancing emergency response efficiency through advanced urban logistics: The role of driver psychophysiology and vehicle dynamics in mitigating socio-economic impacts. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. The impact of dynamic traffic conditions on the sustainability of urban fire service. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, B.R.; Khilar, P.M.; Swain, R.R. Fire Controlling Under Uncertainty in Urban Region Using Smart Vehicular Ad hoc Network. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 116, 2049–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, E.O.; Costa, D.G.; Peixoto, M.M. An optimization approach for emergency vehicles dispatching and traffic lights adjustments in response to emergencies in smart cities. Brazilian Symposium on Computing Systems Engineering 2021, 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Soleimaniamiri, S.; Li, X.; Xie, S. Joint location and assignment optimization of multi-type fire vehicles. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 37, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, C. A POIs Based Method for Location Optimization of Urban Fire Station: A Case Study in Zhengzhou City. Fire 2023, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, K.; Ardianto, R.; Wang, S. Examining fire service coverage and potential sites for fire station locations in Kathmandu, Nepal. Urban Informatics 2024, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).