Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

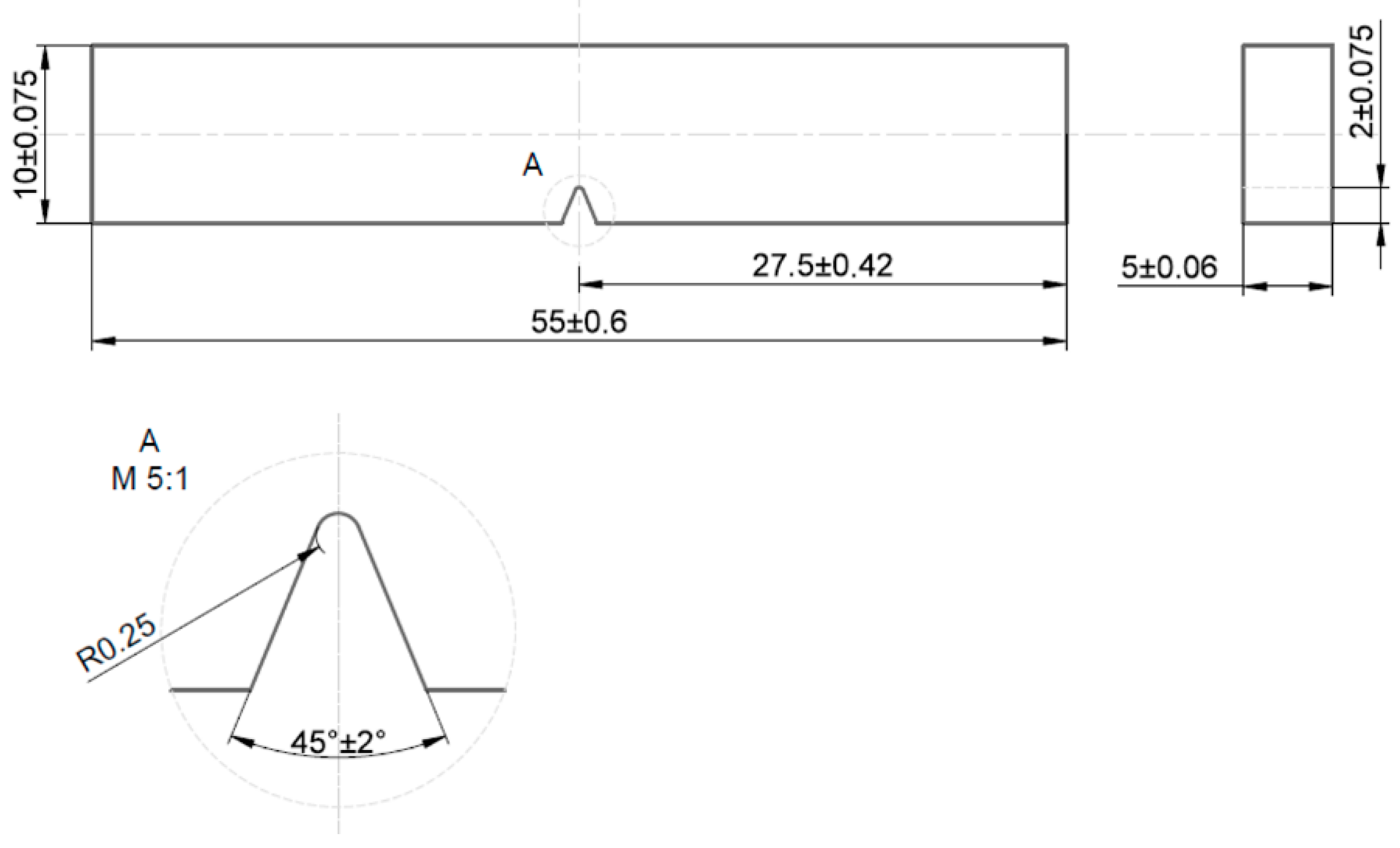

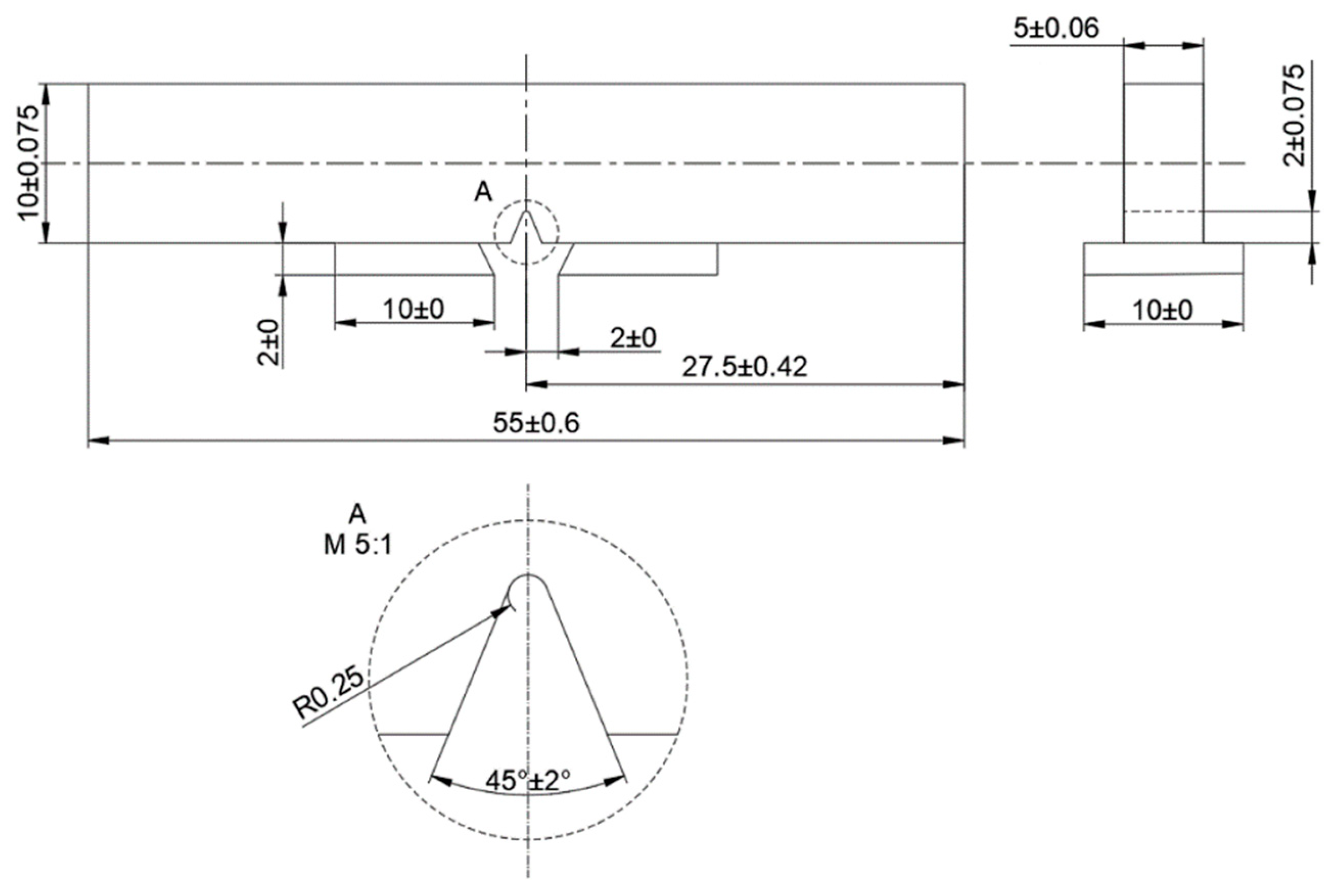

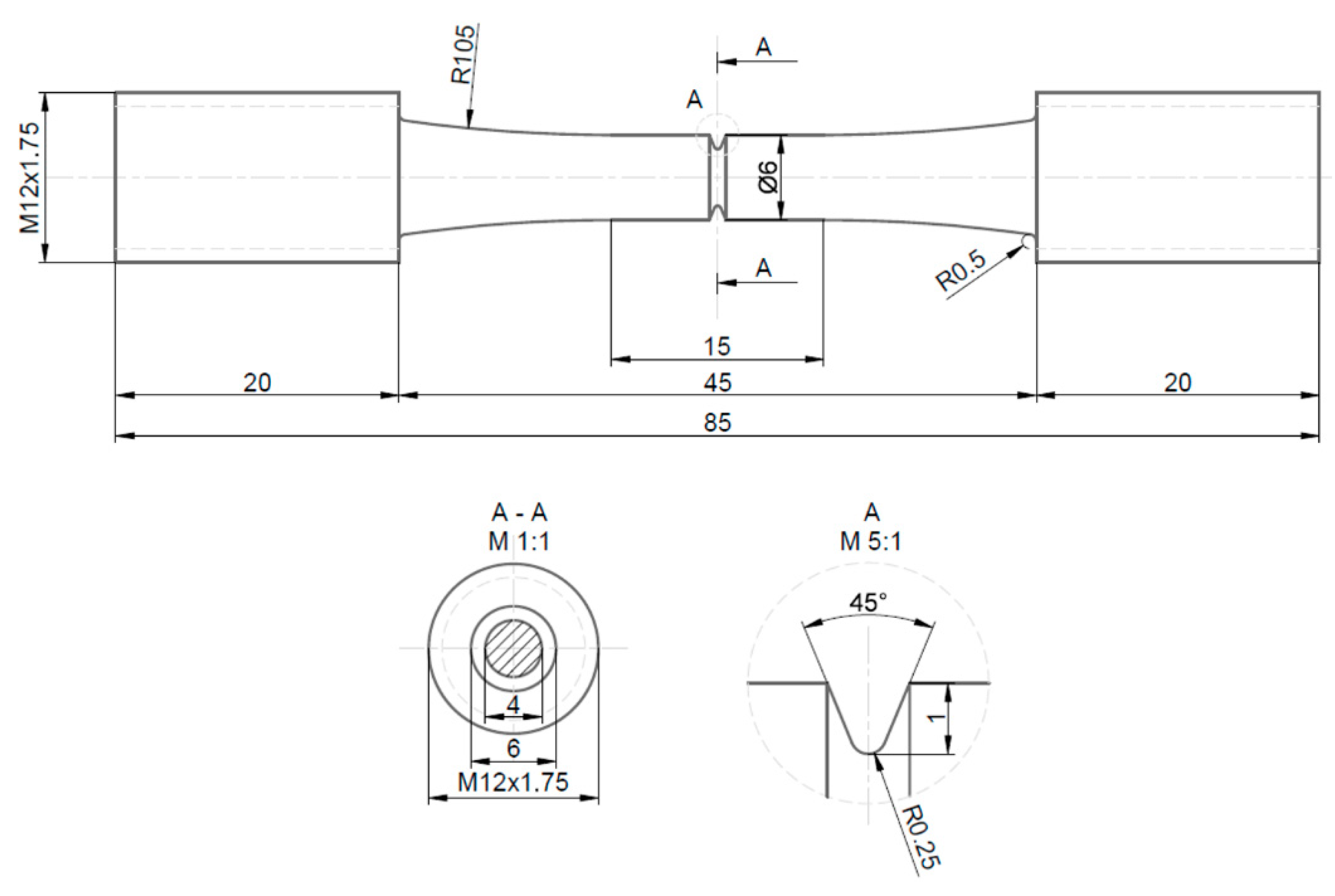

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

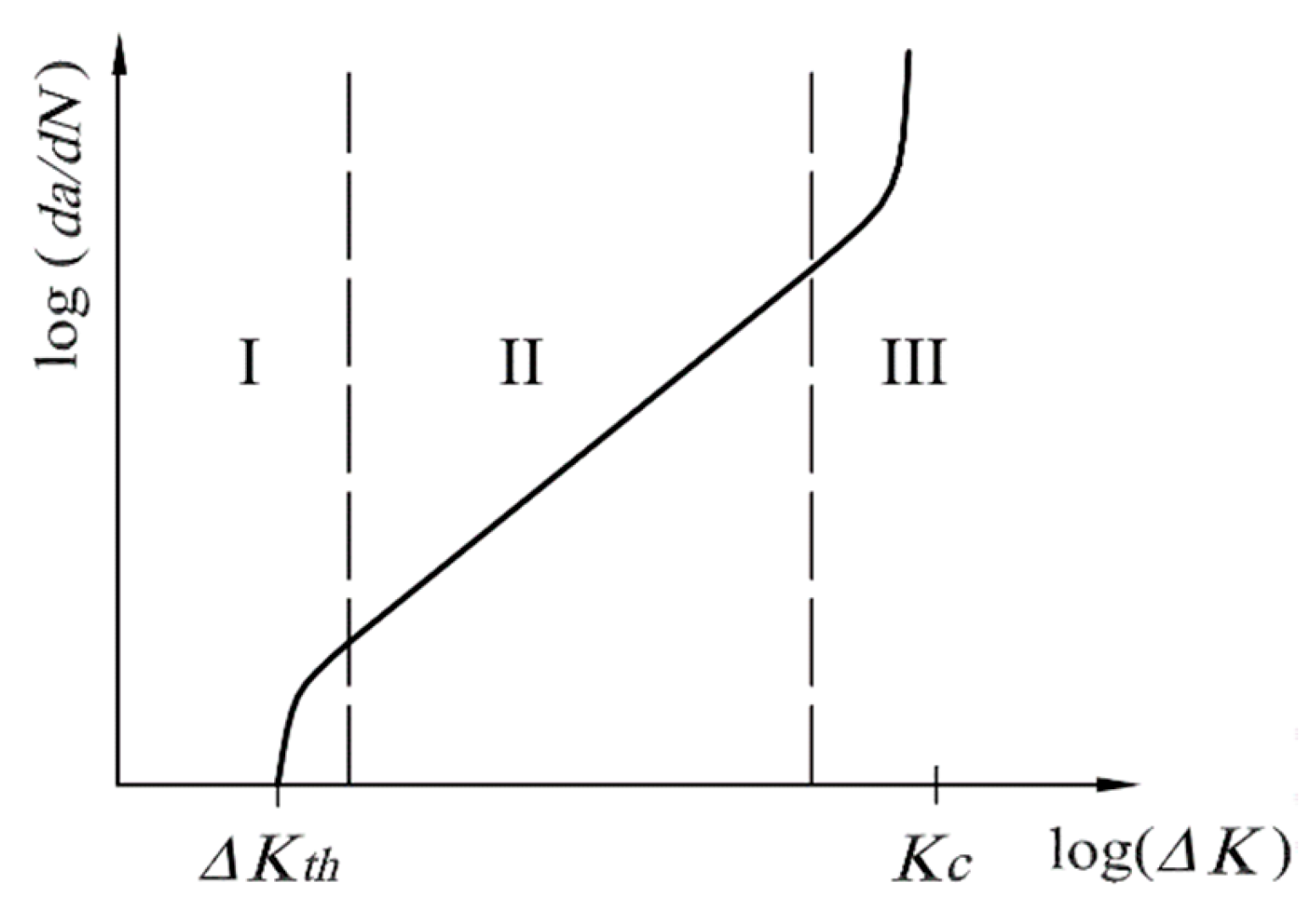

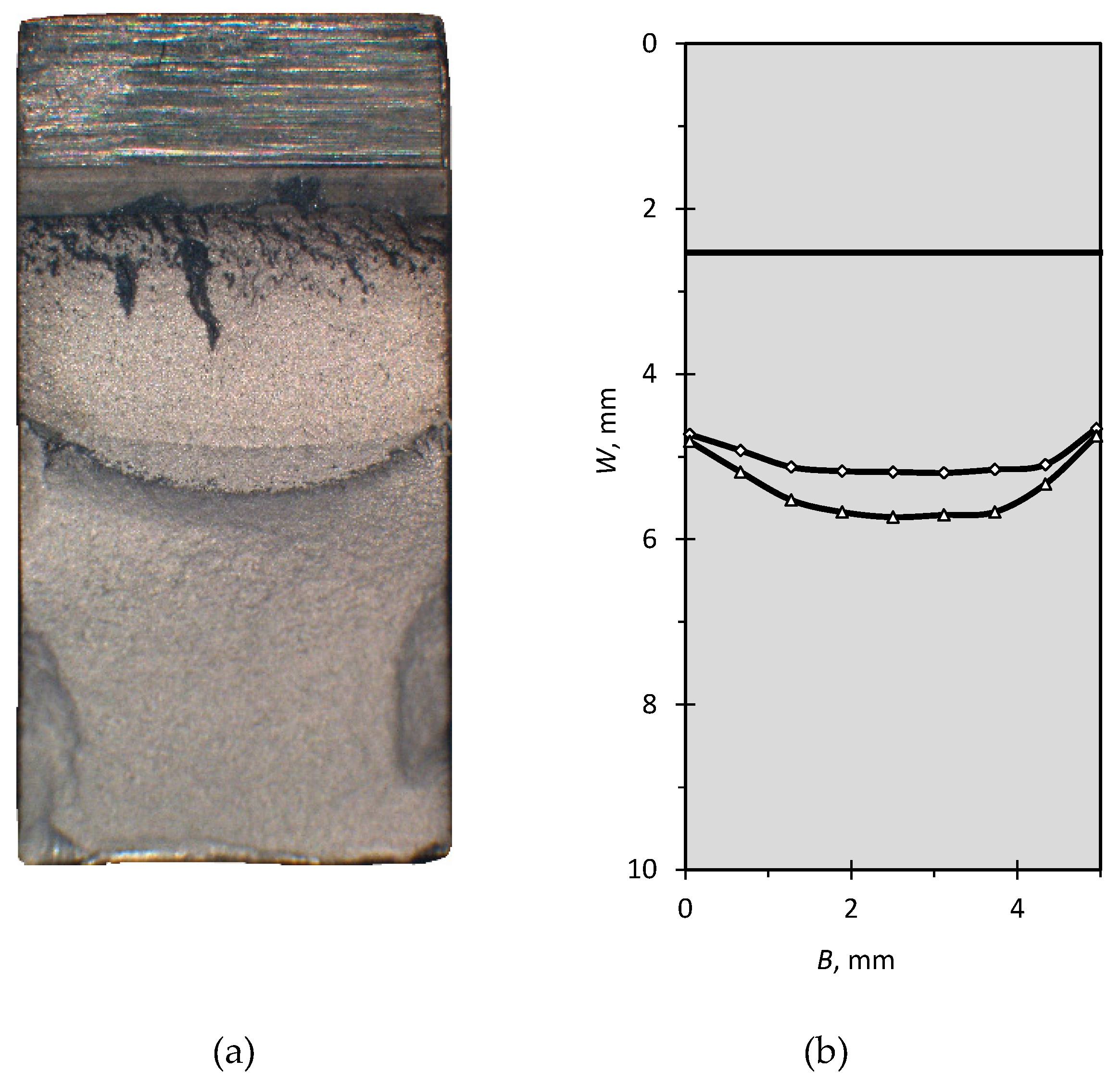

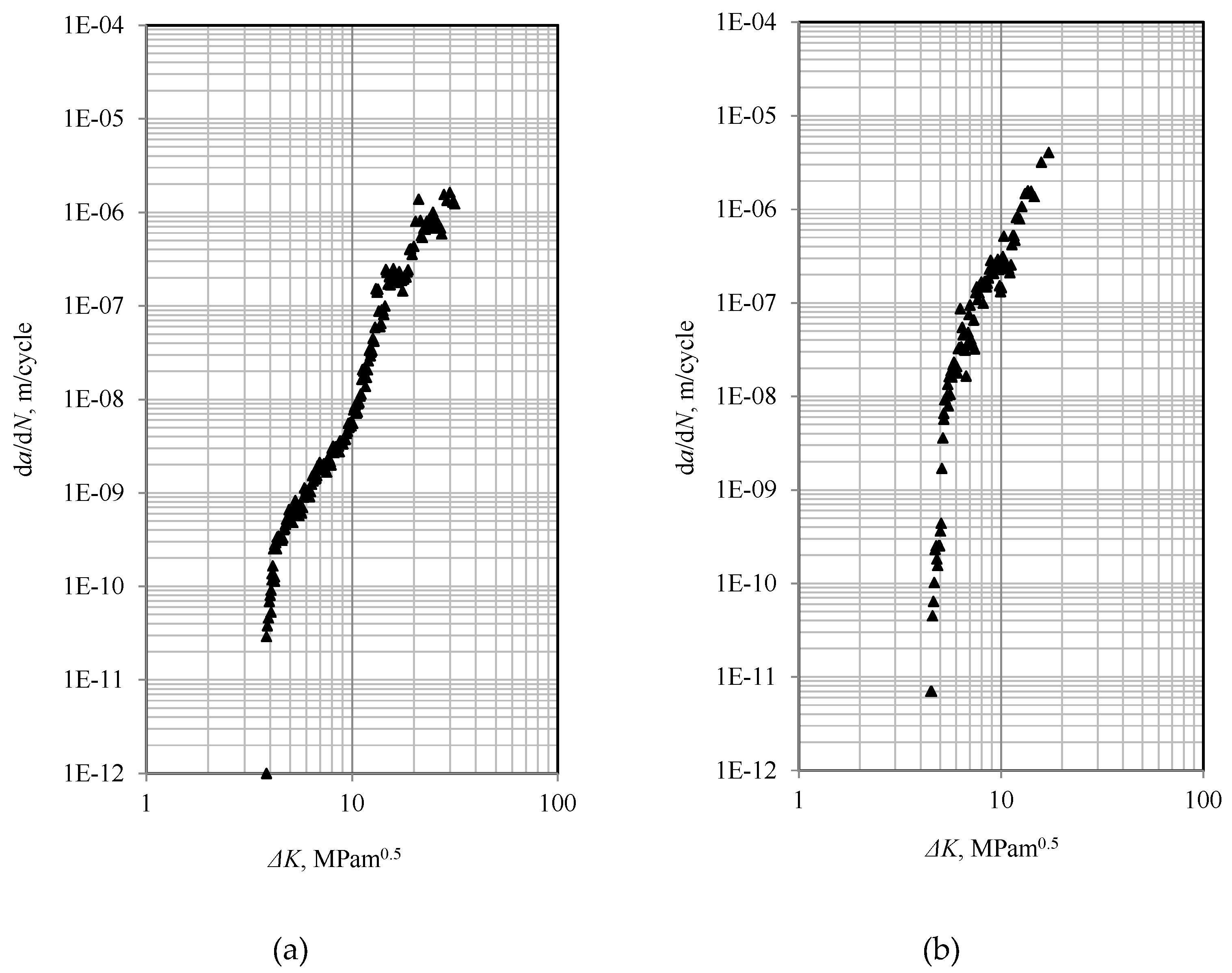

3.1. Threshold Stress Intensity Factor

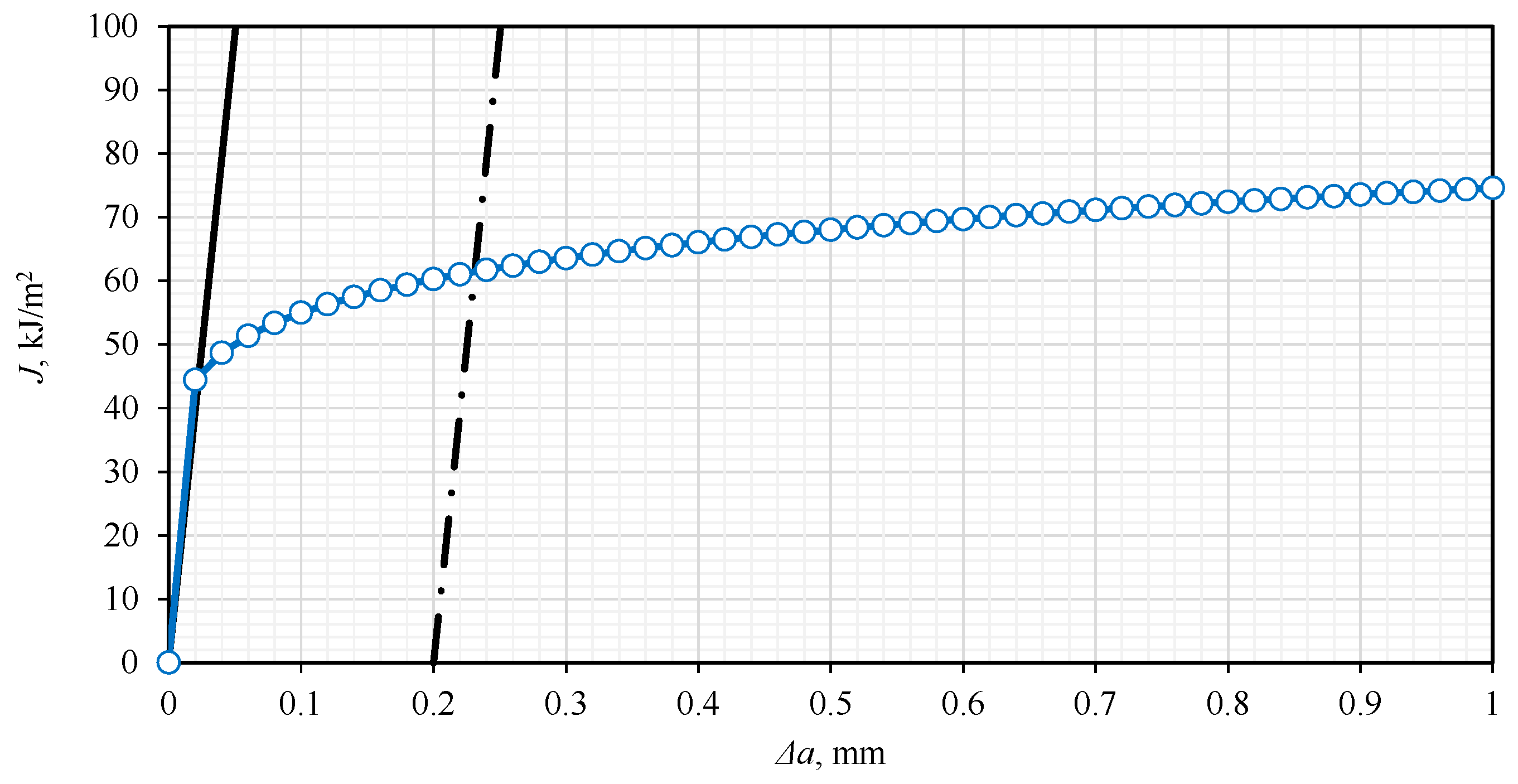

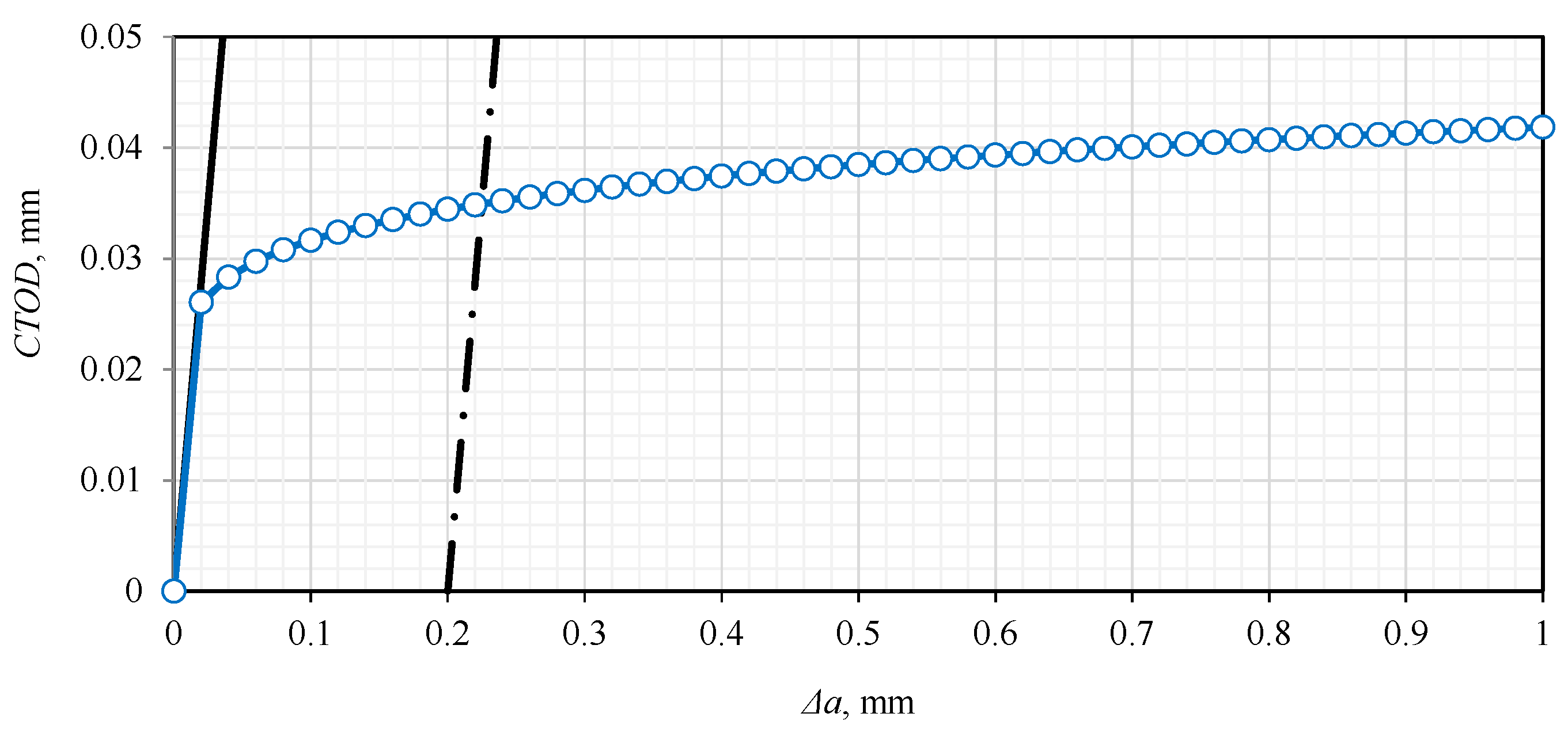

3.2. Fracture Toughness and Resistance Curves According to ASTM E1820 [17]

3.3. Fracture Toughness According to [19]

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| CMOD | Crack Mouth Opening Displacement |

| LLD | Load Line Displacement |

References

- C. Cosmin, I. Drstvensek, P. Berce, S. Prunean, S. Legutko, C. Popa and N. Balc, "Physical–Mechanical Characteristics and Microstructure of Ti6Al7Nb Lattice Structures Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting," Materials, vol. 13, no. 18, p. 4123, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Delshadmanesh, "Fatigue investigations of metallic biomaterials based on Ti-Nb and Co-Cr," 01 11 2018. Available online: https://repositum.tuwien.at/ handle/20.500.12708/7333. (Accessed 02 06 2025).

- M. Hein, D. Kokalj, N. F. Lopes Dias, D. Stangier, H. Oltmanns, S. Pramanik, M. Kietzmann, K.-P. Hoyer, J. Meißner, W. Tillman and M. Schaper, "Low Cycle Fatigue Performance of Additively Processed and Heat-Treated Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloy for Biomedical Applications," Metals, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 122, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Laskowska, B. Bałasz and W. Zawadka, "Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Built Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloys Produced by Selective Laser Melting Technology," Materials, vol. 17, no. 18, p. 4604, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gür, "Deformation Behaviour and Energy Absorption of 3D Printed Polymeric Gyroid Structures," Tehnički vjesnik - Technical Gazette, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 1582-1588, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Pinheiro, J. Gallego, C. Bolfarini, C. S. Kiminami and A. M. J. Junior, "Microstructural Evolution of Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloy During High Pressure Torsion," Materials Research, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 792-795, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Fellah, M. labaïZ, O. Assala, L. Dekhil, A. Taleb, H. Rezzag and I. Alain, "Tribological behavior of Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloys for Total Hip Prosthesis," Advances in Tribology, vol. 2014, p. 13, 21 07 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Squillaci, M. Neikter, T. Hansson, R. Pederson and J. Moverare, "Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated using powder bed fusion – laser beam additive manufacturing process: Effect of hot isostatic pressing," Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 931, p. 19, 06 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Sidambe, "Biocompatibility of Advanced Manufactured Titanium Implants—A Review," Materials, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 8168-8188, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Novak, F. Valjak, N. Bojčetić and M. Šercer, "Design Principle for Additive Manufacturing: Direct Metal Sintering," Tehnički vjesnik - Technical Gazette, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 937-944, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, Z. Pan, D. Ding, D. Cuiuri and H. Li, "Effects of Heat Accumulation on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Ti6Al4V Alloy Deposited by Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing," Additive Manufacturing, vol. 23, pp. 151-160, 08 2018. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization, ISO 148-1:2009. Metallic materials—Charpy pendulum impact test—Part 1: Test method, Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- D. Jelaska, "Osnovi mehanike loma, 2. Dio: širenje pukotine”. Available online: https://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/121375.Cl-MehLoma2.pdf. (accessed 02 06 2025).

- P. Paris and F. Erdogan, "A Critical Analysis of Crack Propagation Laws," Journal of Basic Engineering, vol. 85, no. 4, p. 6, 1963. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Anderson, Fracture Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications, Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2017.

- D. Broek, Elementary Engineering Fracture Mechanics, Dodrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1986. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International, ASTM E1820. Standard Test Method for Measurement of Fracture Toughness, West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, 2019.

- K. Schwalbe, B. Neal and J. Heerens, The GKSS Test Procedure for Determining the Fracture Behaviour of Materials, Geesthacht: GKSS Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH, 1994.

- N. Gubeljak, Mehanika loma, Maribor: Fakulteta za strojništvo, 2008.

- J. J. Lewandowski and M. Seifi, "Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Mechanical Properties," Annual Review of Materials Science, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 151-186, 07 2016. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International, ASTM E466-96. Standard Practice for Conducting Force Controlled Constant Amplitude Axial Fatigue Tests of Metallic Materials, West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, 2021.

- Riemer, S. Leuders, M. Thöne, H. A. Richard, T. Tröster and T. Niendorf, "On the fatigue crack growth behavior in 316L stainless steel manufactured by selective laser melting," Engineering Fracture Mechanics, vol. 120, pp. 15-25, 04 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Taherzadeh, K. Kelleci and S. Özer, "Biomechanical Effects of the Implant Designed for Posterior Dynamic Stabilization of the Lumbar Spine (L4-L5): A Finite Element Analysis Study," vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 193-199, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gelo I.; Kozak D.; Gubeljak N.; Vuherer T. Comparative Analysis of Fracture Mechanics Parameters for Wrought and SLM Produced Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloy. New trends in fatigue and fracture - NT2F19, Tucson, Arizona –USA, October 8-10, 2019.

|

ΔK, MPam0.5 |

da/dN, nm/cycle |

a, mm | N, - | R, - | ΔM, Nm | Mm, Nm |

| 20 | 0 | 2.12 | 367294 | 0.1 | 20.61 | 12.60 |

| 18.99 | 130.517 | 2.171 | 404365 | 0.1 | 19.31 | 11.80 |

| 18.76 | 122.77 | 2.184 | 404466 | 0.1 | 19.01 | 11.62 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 15 | 150.081 | 2.407 | 405952 | 0.1 | 14.35 | 8.77 |

| 14.84 | 155.135 | 2.418 | 406025 | 0.1 | 14.14 | 8.64 |

| 14.68 | 129.771 | 2.429 | 406108 | 0.1 | 13.95 | 8.53 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 10.02 | 87.253 | 2.811 | 411791 | 0.1 | 8.64 | 5.28 |

| 9.91 | 31.133 | 2.822 | 412137 | 0.1 | 8.52 | 5.21 |

| 9.81 | 42.583 | 2.832 | 412388 | 0.1 | 8.41 | 5.14 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 6.6 | 1.235 | 3.228 | 517276 | 0.1 | 5.11 | 3.12 |

| 6.53 | 0.901 | 3.238 | 528412 | 0.1 | 5.05 | 3.09 |

| 6.47 | 0.919 | 3.248 | 539289 | 0.1 | 4.99 | 3.05 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 4.55 | 0.205 | 3.599 | 1528913 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 1.96 |

| 4.51 | 0.194 | 3.609 | 1580407 | 0.1 | 3.16 | 1.93 |

| 4.46 | 0.16 | 3.619 | 1642995 | 0.1 | 3.12 | 1.91 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 3.88 | 0.038 | 3.762 | 3202639 | 0.1 | 2.61 | 1.60 |

| 3.84 | 0.029 | 3.772 | 3547316 | 0.1 | 2.58 | 1.58 |

| 3.84 | 0.001 | 3.774 | 6106690 | 0.1 | 2.58 | 1.58 |

|

ΔK, MPam0.5 |

da/dN, nm/cycle |

a, mm | N, - | R, - | ΔM, Nm | Mm, Nm |

| 13 | 0 | 2.011 | 12542 | 0.1 | 13.79 | 8.43 |

| 12.54 | 804.794 | 2.047 | 27878 | 0.1 | 13.17 | 8.05 |

| 12.34 | 618.045 | 2.063 | 27904 | 0.1 | 12.9 | 7.88 |

| 12.05 | 418.945 | 2.087 | 27949 | 0.1 | 12.53 | 7.66 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 9.34 | 93.277 | 2.267 | 30997 | 0.1 | 9.26 | 5.66 |

| 9.24 | 73.037 | 2.278 | 31148 | 0.1 | 9.13 | 5.58 |

| 9.14 | 47.136 | 2.289 | 31375 | 0.1 | 9.01 | 5.51 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 7.38 | 10.214 | 2.382 | 44671 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 4.34 |

| 7.3 | 14.362 | 2.392 | 45372 | 0.1 | 7.01 | 4.28 |

| 7.23 | 8.162 | 2.402 | 46611 | 0.1 | 6.92 | 4.23 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 5.42 | 1.392 | 2.691 | 185318 | 0.1 | 4.82 | 2.95 |

| 5.36 | 0.907 | 2.702 | 197320 | 0.1 | 4.75 | 2.9 |

| 5.31 | 0.801 | 2.712 | 209809 | 0.1 | 4.7 | 2.87 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 4.63 | 0.064 | 2.852 | 866415 | 0.1 | 3.95 | 2.41 |

| 4.58 | 0.045 | 2.862 | 1089085 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 2.38 |

| 4.53 | 0.001 | 2.872 | 2460570 | 0.1 | 3.85 | 2.35 |

| Production process | Kc, MPam0.5 |

| Drawing (specimen 1) | 84 |

| Drawing (specimen 2) | 83.5 |

| Selective Laser Melting | 21.9 |

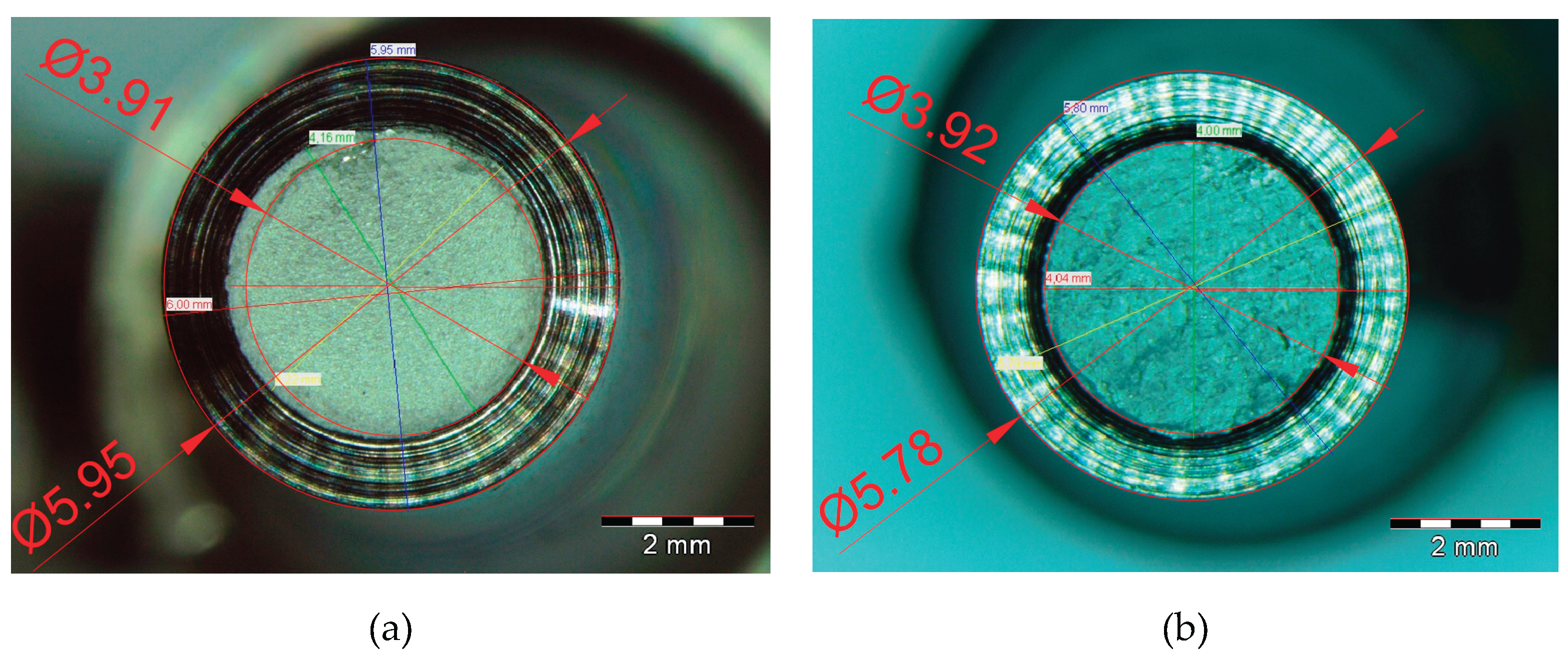

| Production process | F, N | D, mm | D, mm | Kc, MPam0.5 |

| Drawing | 23114 | 5.95 | 3.91 | 61.34 |

| Selective laser melting | 9468 | 5.78 | 3.92 | 24.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).