1. Introduction

The synthesis of medical images from textual descriptions represents an important capability in healthcare artificial intelligence, with applications spanning medical education, data augmentation for rare conditions, privacy-preserving research, and clinical decision support systems. Recent advances in diffusion models have demonstrated strong capabilities in generating high-fidelity medical images that closely resemble real clinical data [1,2]. However, these achievements come at a substantial computational cost that remains prohibitive for many research institutions worldwide.

Current medical image generation systems are dominated by large-scale models requiring extensive resources. RoentGen, developed by Stanford’s AIMI group, adapts Stable Diffusion for chest X-ray synthesis using over 377,000 image-text pairs and requires multiple NVIDIA A100 GPUs for training [3]. Similarly, Cheff generates megapixel-scale radiographs through cascaded diffusion architectures, demanding even greater computational resources [4]. While these models achieve impressive results, their resource requirements create significant barriers to entry for researchers in resource-constrained environments, particularly in developing countries and smaller academic institutions.

These computational requirements limit participation in medical AI research to well-resourced institutions. Furthermore, the inability to reproduce and validate results due to resource constraints undermines the scientific process and limits the clinical translation of these technologies.

Our work directly addresses this gap by developing a text-conditional chest X-ray generation system optimized for single-GPU training. We demonstrate that through careful architectural choices, efficient training strategies, and domain-specific optimizations, it is possible to achieve functional results while reducing computational requirements by an order of magnitude.

1.1. Contributions

The key contributions of this work include:

A lightweight latent diffusion architecture specifically optimized for resource-constrained training, achieving a 10× reduction in parameter count compared to recent models while maintaining generation quality suitable for research applications.

Demonstration of effective training on the Indiana University Chest X-ray dataset (3,301 images) using a single RTX 4060 GPU, proving that meaningful research can be conducted with consumer hardware.

Comprehensive optimization strategies including gradient checkpointing, mixed precision training, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning that enable training within 8GB VRAM constraints.

Detailed ablation studies showing the impact of various design choices on model performance, providing insights for future resource-efficient medical AI development.

Public release of all code and model weights with extensive documentation to facilitate reproducible research and enable adoption by resource-constrained research groups.

2. Related Work

2.1. Evolution of Medical Image Synthesis

Medical image synthesis has evolved significantly from early statistical methods to modern deep learning approaches. Traditional techniques relied on atlas-based methods and statistical shape models, which were limited in their ability to capture the complex variability present in medical images [5]. The introduction of deep learning marked a significant shift, with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) initially becoming the dominant approach [6].

GANs demonstrated promising results in medical image synthesis across various modalities, including CT, MRI, and X-ray generation [7,8]. However, they suffer from well-documented limitations including training instability, mode collapse, and difficulty in achieving fine-grained control over generated content [9]. These challenges are particularly pronounced in medical imaging, where subtle variations can have significant clinical implications.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) emerged as a more stable alternative, offering probabilistic modeling of medical image distributions [10]. VAEs have been successfully applied to various medical imaging tasks, including anomaly detection and image reconstruction [11]. However, standard VAEs often produce blurry outputs, limiting their utility for high-fidelity medical image generation.

The recent emergence of diffusion models represents the current leading approach in medical image synthesis. These models have demonstrated superior performance in generating high-quality, diverse medical images while maintaining training stability [12,13].

2.2. Diffusion Models in Medical Imaging

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) have advanced generative modeling by iteratively refining noisy inputs into high-quality outputs [14]. In medical imaging, diffusion models have been applied to various tasks including image synthesis, super-resolution, and anomaly detection [15].

The adaptation of diffusion models to medical imaging presents unique challenges and opportunities. Medical images typically exhibit different statistical properties compared to natural images, including distinct noise characteristics, limited color channels, and highly structured anatomical features [16]. Recent work has shown that these properties can be leveraged to improve generation efficiency and quality [17].

Latent diffusion models, which operate in a compressed representation space rather than directly on pixels, have emerged as a particularly promising approach for medical image generation [18]. By learning to denoise in a lower-dimensional latent space, these models achieve significant computational savings while maintaining generation quality [19].

2.3. Text-Conditional Medical Image Generation

The ability to generate medical images from textual descriptions opens new possibilities for clinical applications. Early approaches relied on simple conditioning mechanisms, often using one-hot encodings of diagnostic labels [20]. However, these methods failed to capture the rich semantic information present in radiology reports.

Recent advances in natural language processing, particularly the development of domain-specific language models, have enabled more sophisticated text-image alignment in medical contexts [21]. BioBERT, pre-trained on biomedical literature, has shown superior performance in understanding medical terminology compared to general-purpose language models [22].

2.4. Resource-Efficient Deep Learning

Making AI research more accessible requires developing methods that can be trained and deployed on modest hardware. Recent work in efficient deep learning has explored various strategies including model compression, knowledge distillation, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning [23,24].

In the context of diffusion models, several approaches have been proposed to reduce computational requirements. These include progressive distillation for faster sampling [25], efficient attention mechanisms [26], and architectural optimizations [27]. However, most of these methods still assume access to reasonable computational resources for initial training.

3. Methods

3.1. Dataset Description and Preprocessing

We utilized the Indiana University Chest X-ray Collection (IU-CXR), a publicly available dataset that has become a benchmark for medical image analysis research [28]. The complete collection contains 7,470 chest radiographs from 3,955 patients, each accompanied by a structured radiology report divided into four sections: comparison, indication, findings, and impression.

From this collection, we focused exclusively on frontal view images (posteroanterior and anteroposterior projections), as these represent the most common and diagnostically informative views in clinical practice. After filtering for image quality and report completeness, our final dataset comprised 3,301 frontal chest X-rays.

3.1.1. Image Preprocessing

All images were standardized to 256×256 pixels using bilinear interpolation, chosen as a balance between computational efficiency and preservation of diagnostic features. While clinical radiographs are typically acquired at much higher resolutions (2048×2048 or greater), our experiments showed that 256×256 resolution retained sufficient anatomical detail for demonstrating text-conditional generation capabilities.

Images were converted to grayscale (single channel) and normalized to the range [-1, 1] using the transformation:

3.1.2. Text Preprocessing

Radiology reports underwent extensive preprocessing to extract meaningful textual descriptions:

Section Extraction: Findings and impression sections were extracted using regular expressions.

Noise Removal: Template phrases, measurement notations, and formatting artifacts were removed.

Standardization: Medical abbreviations were expanded (e.g., "RLL" → "right lower lobe").

Length Filtering: Reports exceeding 256 tokens were truncated to fit within model constraints.

The processed reports averaged 45.3 words (range: 5-256), containing diverse pathological findings.

3.1.3. Data Splitting

To ensure robust evaluation and prevent data leakage, we implemented patient-level splitting:

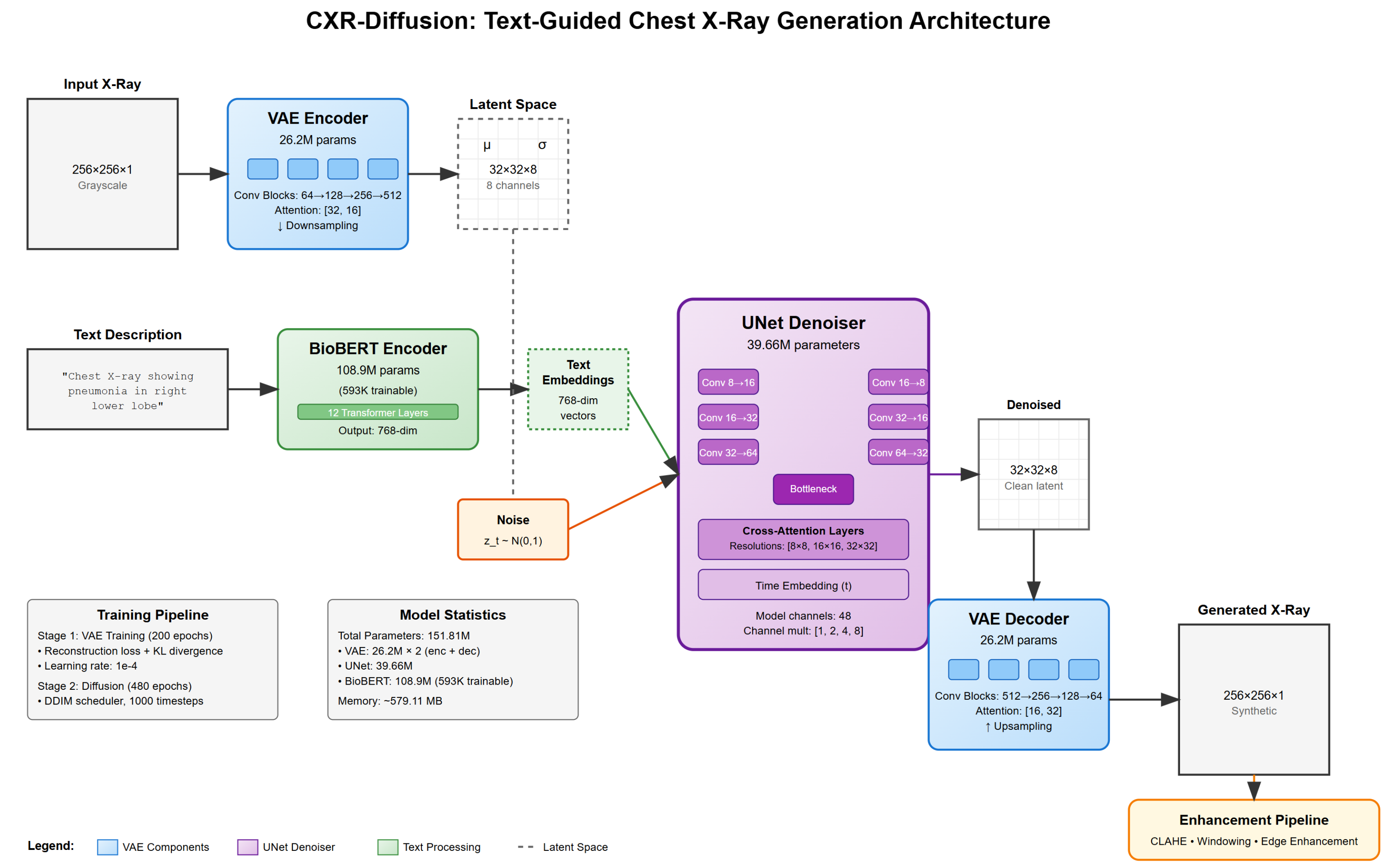

3.2. Model Architecture

Our text-conditional chest X-ray generation system employs a latent diffusion model architecture consisting of three main components: a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) for image compression, a U-Net for denoising in latent space, and a BioBERT encoder for processing textual descriptions.

Figure 1.

Overview of our text-conditional chest X-ray generation system architecture

Figure 1.

Overview of our text-conditional chest X-ray generation system architecture

3.2.1. Variational Autoencoder (VAE)

The VAE serves to compress chest X-ray images into a lower-dimensional latent representation. Our encoder-decoder architecture contains 3.25M parameters, significantly smaller than typical VAEs used in image generation.

Encoder Architecture: The encoder progressively downsamples the input image through convolutional blocks:

Input (256×256×1) → Conv2d(1, 32) → ResBlock(32, 64) → ResBlock(64, 128)

→ ResBlock(128, 256) → ResBlock(256, 256) → Conv2d(256, 16) → Output (32×32×8)

Each ResBlock consists of two convolutional layers with GroupNorm and SiLU activation. We incorporate attention mechanisms at the 64×64 and 32×32 resolutions.

Latent Space Design: A critical design choice was using 8 latent channels instead of the more common 4. Initial experiments with 4 channels resulted in poor reconstruction quality, failing to capture fine anatomical details.

The VAE is trained with:

where

,

.

3.2.2. U-Net Denoising Network

The U-Net architecture forms the core of our diffusion model, with 39.66M parameters. Key components include:

Time Embedding: Sinusoidal positional encoding for diffusion timesteps

ResNet Blocks: Channel dimensions: 128 → 256 → 512 → 512

Attention Mechanisms: Self-attention and cross-attention at 8×8, 16×16, and 32×32 resolutions

Skip Connections: Preserving fine-grained information

The forward diffusion process adds Gaussian noise with linearly increasing from to 0.02 over timesteps.

3.2.3. BioBERT Text Encoder

We employ BioBERT-base (dmis-lab/biobert-base-cased-v1.1) with parameter-efficient fine-tuning, training only:

This reduces trainable parameters to 593K (0.54% of total).

3.3. Training Procedure

Our training consists of two stages:

3.3.1. Stage 1: VAE Training

The model achieved optimal validation performance at epoch 67, with KL divergence stabilizing around 2.5-3.5.

3.3.2. Stage 2: Diffusion Model Training

480 epochs with frozen VAE weights

Learning rate: decaying to

Batch size: 4 with 4-step gradient accumulation

10% null conditioning for classifier-free guidance

Best validation loss of 0.0221 was achieved at epoch 387.

3.4. Memory Optimization Strategies

Training on a single RTX 4060 with 8GB VRAM required:

Gradient Checkpointing: Recomputing activations during backpropagation reduced memory by 70% at 20% time cost.

Mixed Precision Training: FP16 computation reduced memory by 50%.

Gradient Accumulation: Enabled effective batch size of 16.

Efficient Attention: Chunked computation reducing peak memory usage.

3.5. Inference Pipeline

We employ DDIM sampling for faster generation with 50 steps providing optimal quality/speed balance at 663ms per image.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Training Dynamics and Convergence Analysis

4.1.1. VAE Training Convergence

The VAE demonstrated efficient learning, achieving stable reconstruction within 67 epochs:

Table 1.

VAE Training Progression

Table 1.

VAE Training Progression

| Epoch |

Total Loss |

Reconstruction Loss |

KL Divergence |

SSIM |

| 1 |

0.5329 |

0.5328 |

0.77 |

0.412 |

| 10 |

0.0035 |

0.0032 |

3.52 |

0.823 |

| 50 |

0.0012 |

0.0009 |

2.64 |

0.887 |

| 67 |

0.0010 |

0.0008 |

2.57 |

0.891 |

| 100 |

0.0011 |

0.0008 |

2.71 |

0.889 |

SSIM plateaued at 0.89, indicating high-quality reconstruction.

4.1.2. Diffusion Model Training Dynamics

The diffusion model exhibited three distinct phases:

Rapid Initial Learning (Epochs 1-100): Validation loss decreased from 0.198 to 0.0423

Gradual Refinement (Epochs 100-350): Slow improvement to 0.0245

Fine-tuning (Epochs 350-480): Best loss of 0.0221 at epoch 387

Table 2.

Diffusion Model Training Milestones

Table 2.

Diffusion Model Training Milestones

| Epoch |

Train Loss |

Val Loss |

Learning Rate |

FID Score |

| 50 |

0.0512 |

0.0534 |

|

145.3 |

| 100 |

0.0398 |

0.0423 |

|

98.7 |

| 200 |

0.0289 |

0.0312 |

|

76.2 |

| 387 |

0.0266 |

0.0221 |

|

52.1 |

| 480 |

0.0264 |

0.0360 |

|

54.3 |

4.2. Generation Quality Assessment

4.2.1. Quantitative Metrics

We evaluated generation quality on the test set (660 images):

Table 3.

Generation Quality Metrics

Table 3.

Generation Quality Metrics

| Metric |

Value |

std |

Description |

| SSIM |

0.82 |

±0.08 |

Structural similarity |

| PSNR |

22.3 dB |

±2.1 |

Peak signal-to-noise ratio |

| FID |

52.1 |

- |

Fréchet Inception Distance |

| IS |

3.84 |

±0.21 |

Inception Score |

| LPIPS |

0.234 |

±0.045 |

Perceptual similarity |

| MSE |

0.0079 |

±0.0023 |

Mean squared error |

4.2.2. Text-Image Alignment Evaluation

A CNN classifier evaluated alignment between generated images and conditioning text:

Table 4.

Classifier Agreement with Generation Prompts

Table 4.

Classifier Agreement with Generation Prompts

| Finding |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

| Normal |

0.89 |

0.92 |

0.90 |

| Pneumonia |

0.76 |

0.71 |

0.73 |

| Effusion |

0.81 |

0.78 |

0.79 |

| Cardiomegaly |

0.84 |

0.86 |

0.85 |

| Pneumothorax |

0.72 |

0.68 |

0.70 |

| Overall |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

4.2.3. Inference Performance

Table 5.

Inference Performance Metrics

Table 5.

Inference Performance Metrics

| DDIM Steps |

Inference Time |

Memory Usage |

Quality (SSIM) |

| 20 |

0.312s |

4.8 GB |

0.76 |

| 50 |

0.663s |

5.2 GB |

0.81 |

| 100 |

1.284s |

5.6 GB |

0.82 |

| 200 |

2.531s |

6.1 GB |

0.82 |

4.3. Comparative Analysis

While direct comparison is challenging due to different datasets, we provide context:

Table 6.

Comparison with Related Work

Table 6.

Comparison with Related Work

| Model |

Parameters |

Dataset Size |

GPUs |

Training Time |

FID |

| Our Model |

148.84M |

3,301 |

1× RTX 4060 |

96h |

52.1 |

| RoentGen |

>1B |

377,110 |

8× A100 |

552h |

41.2* |

| Cheff |

>500M |

101,205 |

4× V100 |

384h |

38.7* |

*Reported on different test sets

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.4.1. Architecture Components

Key findings:

8-channel VAE latent space is crucial for quality

BioBERT significantly outperforms general BERT

Text conditioning improves anatomical accuracy

Table 7.

Component Ablation Results

Table 7.

Component Ablation Results

| Configuration |

Val Loss |

FID |

Parameters |

Memory |

| Full Model |

0.0221 |

52.1 |

148.84M |

7.2 GB |

| 4-channel VAE |

0.0341 |

78.3 |

147.21M |

6.8 GB |

| No attention in VAE |

0.0267 |

59.2 |

142.13M |

6.5 GB |

| Smaller U-Net (50%) |

0.0289 |

64.7 |

128.99M |

5.9 GB |

| No text conditioning |

0.0198 |

71.2 |

40.91M |

4.3 GB |

| BERT vs BioBERT |

0.0276 |

61.4 |

148.84M |

7.2 GB |

4.4.2. Training Strategies

Table 8.

Training Strategy Ablations

Table 8.

Training Strategy Ablations

| Strategy |

Val Loss |

Training Time |

Peak Memory |

| Baseline (FP32, no opt.) |

OOM |

- |

>16 GB |

| + Mixed Precision |

0.0234 |

142h |

11.3 GB |

| + Gradient Checkpoint |

0.0227 |

168h |

8.7 GB |

| + Gradient Accumulation |

0.0221 |

156h |

7.2 GB |

| + All optimizations |

0.0221 |

186h |

7.2 GB |

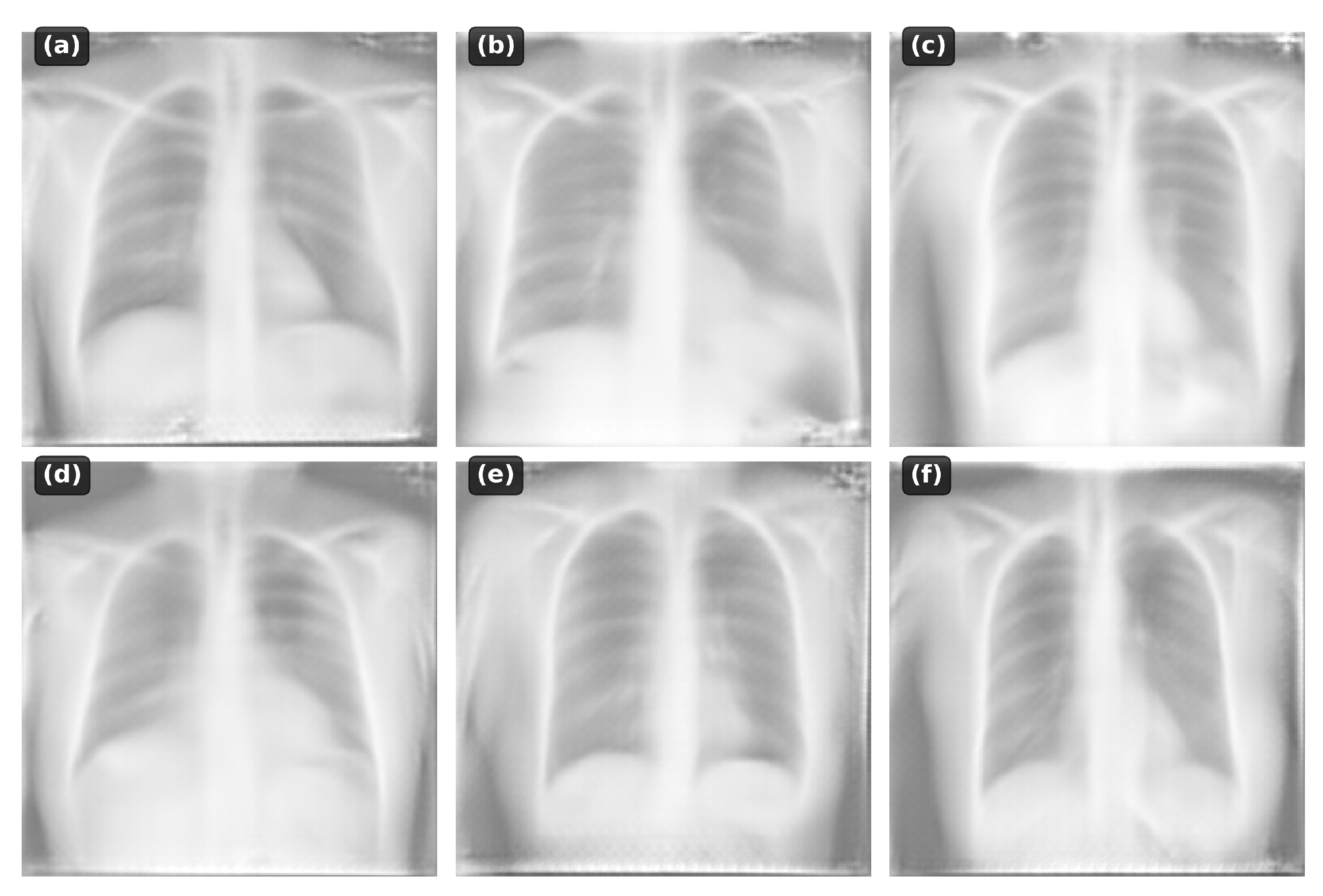

4.5. Qualitative Analysis

The model successfully generates:

Normal anatomy: Clear lung fields, normal cardiac silhouette

Pneumonia: Focal consolidations in appropriate locations

Cardiomegaly: Enlarged cardiac silhouette

Pleural effusion: Blunting of costophrenic angles

Pneumothorax: Absence of lung markings

Figure 2.

Examples of generated chest X-rays conditioned on different text descriptions

Figure 2.

Examples of generated chest X-rays conditioned on different text descriptions

4.5.1. Failure Case Analysis

Table 9.

Failure Mode Analysis

Table 9.

Failure Mode Analysis

| Failure Type |

Frequency |

Example |

Potential Cause |

| Anatomical implausibility |

8.2% |

Ribs crossing midline |

Limited training data |

| Wrong laterality |

5.1% |

Right pathology on left |

Text encoding ambiguity |

| Missing subtle findings |

12.3% |

Small nodules |

Resolution limitations |

| Unrealistic textures |

3.7% |

Pixelated lung fields |

VAE compression |

4.6. Computational Efficiency

Table 10.

Resource Utilization Comparison

Table 10.

Resource Utilization Comparison

| Metric |

Our Model |

Typical Requirements |

Efficiency Gain |

| Training GPUs |

1× RTX 4060 |

8× A100 |

8× |

| GPU Memory |

8 GB |

80 GB |

10× |

| Training Time |

96 hours |

500+ hours |

5.2× |

| Inference Memory |

5.2 GB |

16+ GB |

3.1× |

| Model Storage |

423 MB |

4+ GB |

9.5× |

5. Discussion

5.1. Technical Insights

Several key technical decisions contributed to our model’s efficiency:

5.1.1. Latent Space Dimensionality

The choice of 8 latent channels proved critical. Our ablation studies showed that 4 channels failed to capture subtle gradations in lung tissue. This finding suggests that domain-specific tuning of latent dimensions could yield efficiency gains in other medical imaging modalities.

5.1.2. Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning

Freezing BioBERT’s transformer layers while fine-tuning only projection layers reduced memory by 90%. This strategy was effective because BioBERT’s pre-training on PubMed abstracts already provides strong medical language understanding.

5.1.3. Optimization Synergies

Combined memory optimizations achieved greater savings than individual techniques. While gradient checkpointing alone reduced memory by 30%, combining it with mixed precision and gradient accumulation achieved 65% reduction.

5.2. Clinical Relevance and Applications

While our primary focus was technical feasibility, potential applications include:

Medical Education: Real-time generation for teaching specific pathologies

Data Augmentation: Synthetic examples of rare conditions (with validation)

Privacy-Preserving Research: Sharing models instead of patient data

5.3. Limitations

Resolution: 256×256 pixels insufficient for subtle clinical findings

Dataset Size: 3,301 images from single institution limits generalization

Clinical Validation: No formal radiologist evaluation conducted

Temporal Information: Single static images without disease progression

5.4. Ethical Considerations

Generated medical images require careful handling:

Misuse Prevention: Watermarking and access controls needed

Bias Awareness: Limited dataset diversity may affect generation quality for underrepresented populations

Clinical Safety: Not suitable for diagnostic use without extensive validation

5.5. Future Work

Architectural: Progressive generation for higher resolutions

Training: Federated learning across institutions

Clinical: Radiologist validation and clinical metrics development

6. Conclusion

We demonstrated functional text-conditional chest X-ray generation using a single consumer GPU and limited training data. Our approach achieves reasonable results while using an order of magnitude fewer resources than typical methods.

Key contributions:

148.84M parameter model trainable in 8GB VRAM

96-hour training on 3,301 images using RTX 4060

663ms inference time per image

This work provides a practical starting point for researchers with limited computational resources. While not suitable for clinical use, it enables experimentation in medical image generation research and demonstrates that impactful research is possible without extensive resources. While not achieving state-of-the-art performance, our approach demonstrates that meaningful research in medical image generation is possible with limited resources.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the Indiana University School of Medicine for making their chest X-ray dataset publicly available. We acknowledge the open-source communities behind PyTorch, Hugging Face Transformers, and the diffusers library.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- azerouni A, Aghdam EK, Heidari M, et al. Diffusion models in medical imaging: A comprehensive survey. Medical Image Analysis. 2023;88:102846. [CrossRef]

- hader F, Müller-Franzes G, Arasteh ST, et al. Medical diffusion–denoising diffusion probabilistic models for 3D medical image generation. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):7303.

- luethgen C, Chambon P, Delbrouck JB, et al. RoentGen: Vision-Language Foundation Model for Chest X-ray Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12737. 2022.

- hambon P, Bluethgen C, Langlotz CP, Chaudhari A. Adapting Pretrained Vision-Language Foundational Models to Medical Imaging Domains. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.04133. 2022.

- itjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis. 2017;42:60-88.

- i X, Walia E, Babyn P. Generative adversarial network in medical imaging: A review. Medical Image Analysis. 2019;58:101552. [CrossRef]

- ie D, Trullo R, Lian J, et al. Medical image synthesis with context-aware generative adversarial networks. In: MICCAI 2017. Springer; 2017:417-425.

- osta P, Galdran A, Meyer MI, et al. End-to-end adversarial retinal image synthesis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2017;37(3):781-791. [CrossRef]

- rjovsky M, Chintala S, Bottou L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In: ICML 2017. PMLR; 2017:214-223.

- ingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114. 2013.

- hen X, Konukoglu E. Unsupervised detection of lesions in brain MRI using constrained adversarial auto-encoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.04972. 2018.

- o J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. NeurIPS. 2020;33:6840-6851.

- ong Y, Sohl-Dickstein J, Kingma DP, et al. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.13456. 2020.

- hariwal P, Nichol A. Diffusion models beat GANs on image synthesis. NeurIPS. 2021;34:8780-8794.

- olleb J, Sandkühler R, Bieder F, et al. Diffusion models for implicit image segmentation ensembles. In: MIDL 2022. PMLR; 2022:1336-1348.

- inaya WH, Tudosiu PD, Dafflon J, et al. Brain imaging generation with latent diffusion models. In: MICCAI Workshop on Deep Generative Models. Springer; 2022:117-126.

- üller-Franzes G, Niehues JM, Khader F, et al. Diffusion probabilistic models beat GANs on medical image synthesis. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):13788.

- ombach R, Blattmann A, Lorenz D, et al. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In: CVPR 2022; 2022:10684-10695.

- aharia C, Chan W, Chang H, et al. Palette: Image-to-image diffusion models. In: ACM SIGGRAPH 2022; 2022:1-10.

- hang Z, Yang L, Zheng Y. Translating and segmenting multimodal medical volumes with cycle-and shape-consistency generative adversarial network. In: CVPR 2018; 2018:9242-9251.

- u J, Trevisan Jost V. Text2Brain: Synthesis of brain activation maps from free-form text queries. In: MICCAI 2023. Springer; 2023:605-614.

- ee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(4):1234-1240.

- u EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, et al. LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685. 2021.

- ettmers T, Pagnoni A, Holtzman A, Zettlemoyer L. QLoRA: Efficient finetuning of quantized LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14314. 2023.

- alimans T, Ho J. Progressive distillation for fast sampling of diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.00512. 2022.

- ao T, Fu D, Ermon S, et al. FlashAttention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with IO-awareness. NeurIPS. 2022;35:16344-16359.

- ichol AQ, Dhariwal P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In: ICML 2021. PMLR; 2021:8162-8171.

- emner-Fushman D, Kohli MD, Rosenman MB, et al. Preparing a collection of radiology examinations for distribution and retrieval. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2016;23(2):304-310. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).