1. Introduction

Individual autonomy is widely acknowledged as a fundamental factor that fosters intrinsic motivation [

1] and supports mental health [

2]. As mobility is essential to exercising autonomy, the ability to move independently plays a vital role in enabling individuals to care for themselves, thereby significantly enhancing overall well-being [

3,

4]. However, the global prevalence of visual and mobility impairments is on the rise, primarily due to an aging population [

5,

6] and an increasing incidence of chronic diseases [

7,

8,

9]. These impairments directly compromise individual autonomy and adversely affect quality of life. To mitigate these challenges, there is an increasing demand for fully automated intelligent assistive systems that incorporate advanced object detection and safe navigation capabilities to support independent living.

Recognizing the need to improve the quality of life of individuals with visual and mobility impairments, researchers have developed semi-automated assistive systems. For instance, Mahadevaswamy et al.[

10] proposed a semi-automated wheelchair capable of operating in both manual and semi-automatic modes. In manual mode, the user navigates using hand controls, while in semi-automatic mode, the system assists navigation across challenging terrains such as inclines, declines, uneven surfaces, and muddy paths, thereby reducing physical effort via a joystick interface. Another system by Karim et al.[

11] employs an array of ultrasonic sensors to facilitate autonomous navigation. This system demonstrates a response time between 0.2 and 0.5 seconds, with an effective obstacle detection range of up to 30 cm. Similarly, the wheelchair developed by Hasan et al. [

12] integrates accelerometers and ultrasonic sensors for obstacle detection and safe navigation. It also includes a feature that enables a third party to remotely control the wheelchair in unsafe situations. Although these semi-automated systems have made notable contributions toward improving the mobility and independence of users, they still rely on human input. This dependency limits their suitability for individuals with severe impairments who are unable to control the system independently, and can cause physical fatigue in users with partial mobility, potentially exacerbating existing health conditions. Furthermore, a critical concern remains that the reliability and safety of these systems under malfunctioning or faulty conditions is not adequately addressed in the cited literature.

Understanding the limitations of semi-automated systems, recent research has increasingly focused on the development of fully automated sensor-based assistive technologies for individuals with visual and mobility impairments. Early navigation systems predominantly employed sensors such as ultrasonic modules [

13,

14], LiDAR [

15,

16], and infrared sensors [

17] to detect obstacles and architectural features such as doorways. These systems utilized range and depth data to identify flat vertical surfaces and open areas, often combined with geometric modeling to determine doorway boundaries. Although effective in controlled environments, these sensor-based systems face considerable challenges in real-world settings, including reduced accuracy in dynamic or cluttered environments, limited sensing range, and high sensitivity to environmental noise and interference [

18,

19,

20]. Furthermore, reliance on multiple sensors increases hardware complexity, cost, and power consumption, limiting their practicality and scalability [

21].

To address the hardware and scalability limitations of traditional sensor-based systems, recent research has increasingly shifted toward deep learning-based approaches that utilize monocular RGB input to detect and interpret structural features in indoor environments. Lecronsnier et al.[

22] introduced a deep learning framework aimed at enhancing indoor navigation for smart wheelchairs. Their system integrated the YOLOv3 algorithm[

23] for object detection with Intel RealSense sensors to provide depth perception. For robust 3D object tracking, the system employed the Simple Online Realtime Tracking (SORT) algorithm [

24], enabling accurate identification and tracking of key navigation elements such as doors and handles, thereby improving the semi-autonomous functionality of the wheelchair. Building on this direction, Zhang et al.[

25] proposed DSPP-YOLO, an enhanced YOLOv3-based architecture designed for detecting doors and windows in unfamiliar indoor environments. This model incorporated DenseNet blocks[

26] and spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) [

27] to improve multiscale feature extraction anused K-means for optimized anchor box generation. As a result, DSPP-YOLO achieved a 3.3% improvement in door detection accuracy and an 8. 8% increase in window detection, without additional computational cost. Similarly, Mochurad and Hladun [

28] developed a method based on a real-time neural network for the recognition of door handles using RGB-D cameras. Their approach used a MobileNetV2 backbone [

29] and a custom decoder, allowing the system to process up to 16 images per second. This facilitated robust recognition of various door handle designs in diverse environments, improving robotic interaction. With the growing need for lightweight and accurate real-time detection models, recent work has focused on YOLOv8 [

30] to enhance scene understanding in assistive navigation applications, including doorway recognition [

31,

32,

33]. However, many of these models prioritize object detection without adequately capturing contextual and structural cues [

19,

34,

35]. Specifically, while efficient, these architectures often lack mechanisms to emphasize salient features unique to structural elements like doors, an essential requirement for wheelchair navigation. Consequently, they may misclassify visually similar patterns as doorways, leading to navigation errors and potential safety risks for users.

Despite increasing interest in sensor and vision-based navigation systems, accurate doorway detection and navigational guidance for autonomous wheelchairs remain insufficiently addressed. To overcome these limitations, we propose a vision-based architecture that detects doors and guides wheelchair users through them using monocular RGB input. Our approach enhances the YOLOv8-seg backbone by incorporating spatial and channel-wise attention mechanisms through the CBAM [

36] and CGCAFusion [

37] to improve multiscale feature aggregation. To mitigate the absence of physical depth sensors, we introduce a lightweight RGB-based depth estimation head that infers spatial layouts directly from 2D images. This component is optimized for real-time inference in low-power embedded systems, making it suitable for deployment in assistive mobility devices. The core contributions of this work include:

Integration of a CBAM module within the YOLOv8 backbone to enhance spatial and channel-wise focus on structural features of doorways.

Implementation of a CGCAFusion module for multi-scale contextual refinement to improve accuracy in segmenting semantically similar regions.

Development of a lightweight dual head structure for simultaneous door segmentation and monocular depth estimation module (DEM).

Implementation of an Alignment Estimation Module (AEM) to correct door misalignment and provide real-time guidance to users.

2. Materials and Methods

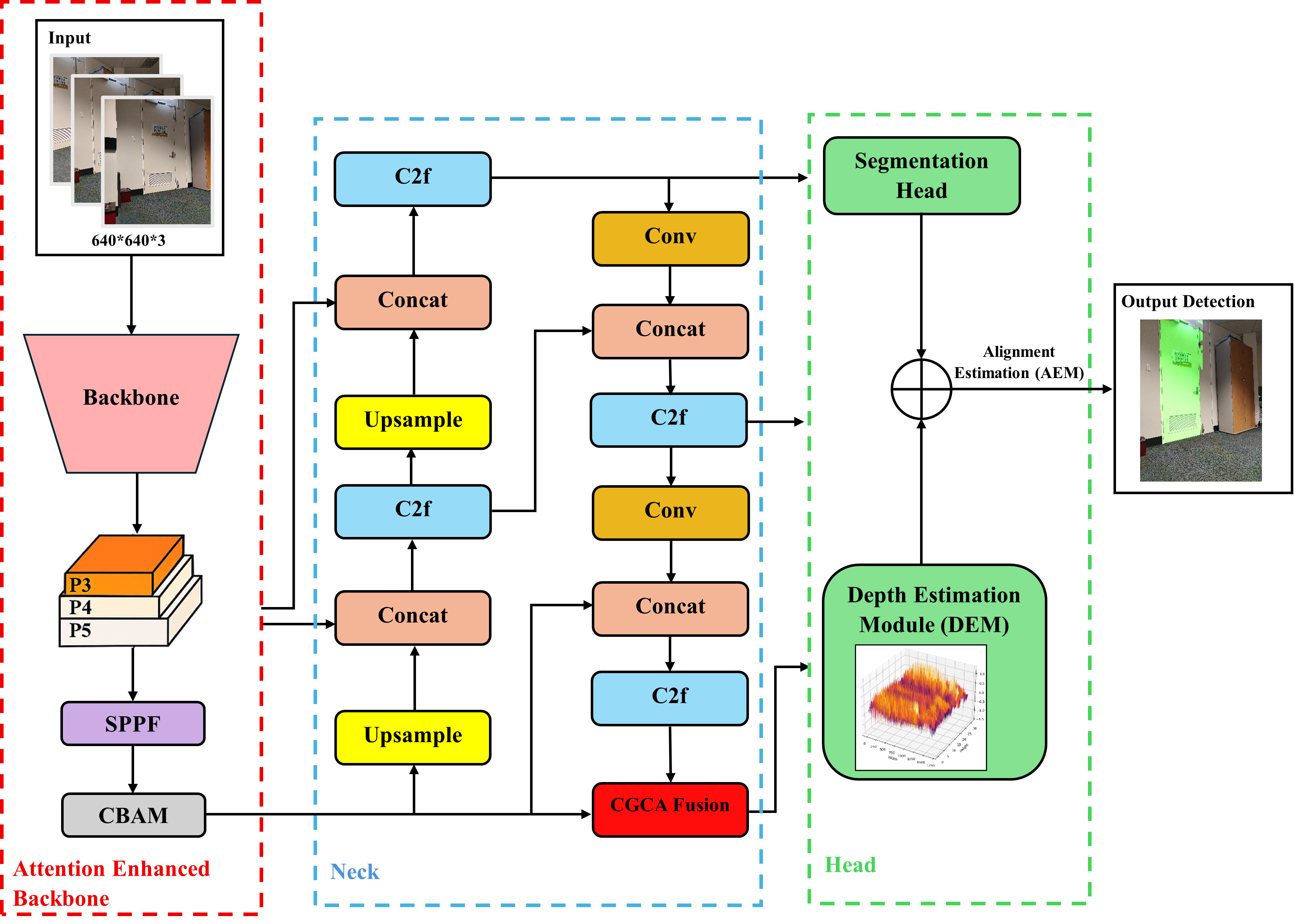

In this section, we describe the proposed model, named ’YOLOv8-seg-CA (context-aware)’ developed to support assistive wheelchair navigation by detecting doorways and providing navigational guidance from a video input. The overall architecture (

Figure 1) of our model consists of four sub modules:

- 1)

Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM): This sub module enhances the feature representation in the YOLOv8 backbone by applying channel and spatial attention, allowing the model to focus more effectively on salient regions associated with doorways, as detailed in

Section 2.2.

- 2)

Content-Guided Convolutional Attention Fusion Module (CGCAFusion): This sub module is responsible for dynamically building contextual relationships based on input feature content using a content-guided convolutional attention mechanism, improving structural segmentation performance in cluttered indoor scenes, as detailed in

Section 2.3.

- 3)

Depth Estimation Module (DEM): The objective of this sub module is to predict relative depth information from RGB inputs, eliminating the need for external depth sensors while providing spatial context to support alignment estimation (

Section 2.4).

- 4)

Alignment Estimation Module (AEM): The final sub module is designed to compute the lateral offset of the detected doorway with respect to the image center to suggest directional guidance (e.g., move left, right, or stay centered) for wheelchair navigation, as described in

Section 2.5.

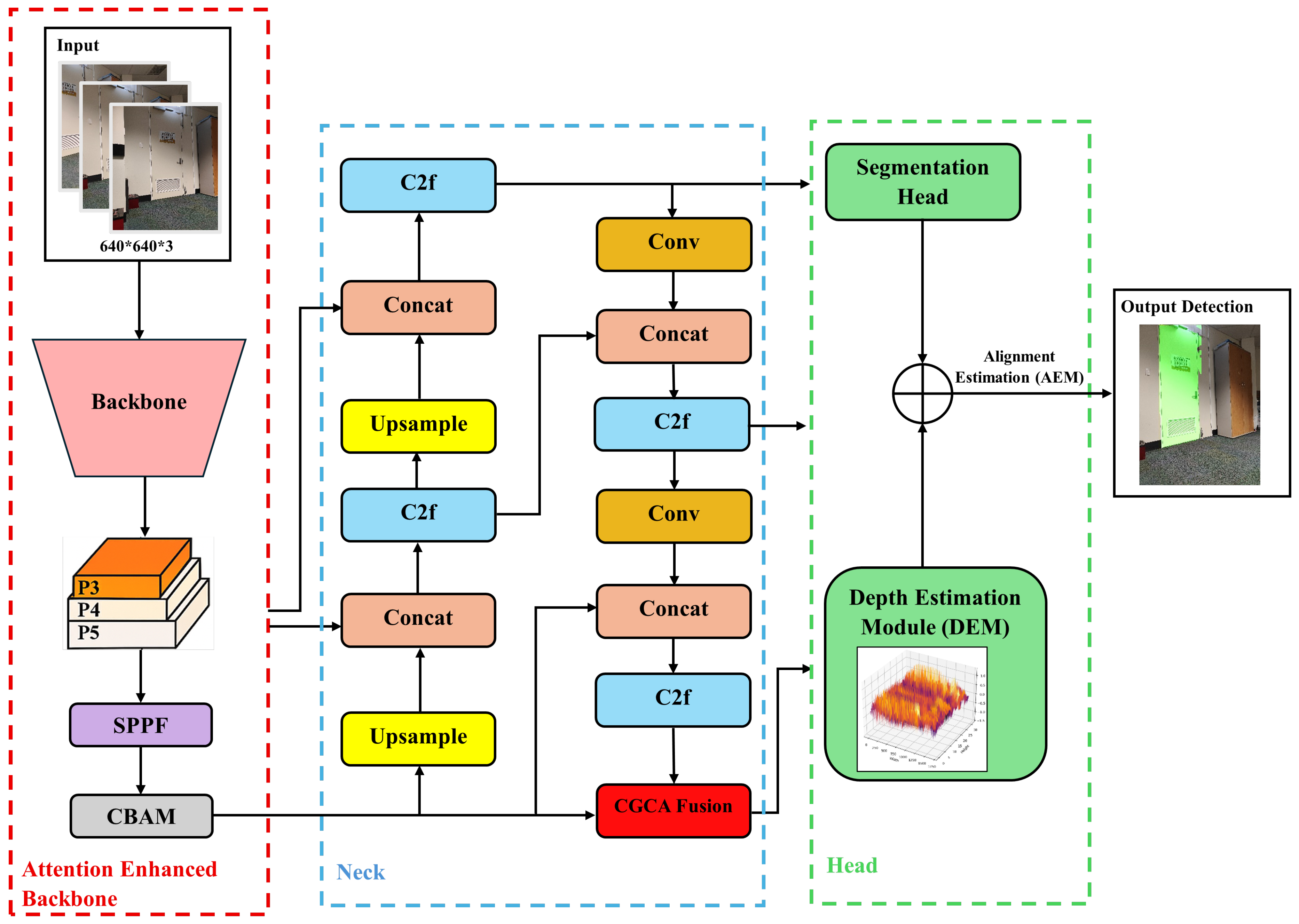

2.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this study is based on the DeepDoorsv2 dataset [

38], originally designed to support semantic segmentation and object detection of door structures in indoor environments. The dataset consists of high-resolution RGB images captured in diverse conditions, including varying lighting, occlusions, viewing angles, and architectural layouts. To ensure variability, the images include single and double doors, open and closed configurations, and challenging real-world backgrounds.

The dataset has a total of 3000 segmented RGB door images with 1000 closed, semi-open, and open doors each in 480 x 640 pixels. The pixel values 192,224,192 correspond to door/door frame, and 0,0,0 corresponds to background. In addition to DeepDoorsv2, we collected a supplementary set of 100 custom indoor doorway images to reflect everyday navigation scenarios. The total dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1.5:1.5 ratio.

Figure 2(a) illustrates sample images and the corresponding mask of a closed, semi-open, and open door, respectively.

Figure 2(b) shows a correlogram of the normalized bounding box attributes (x, y, width, height) in the dataset. The diagonal plots show individual distributions, while the off-diagonal plots show pairwise density relationships. This confirms that most of the doors are centered in the image and follow consistent geometric proportions.

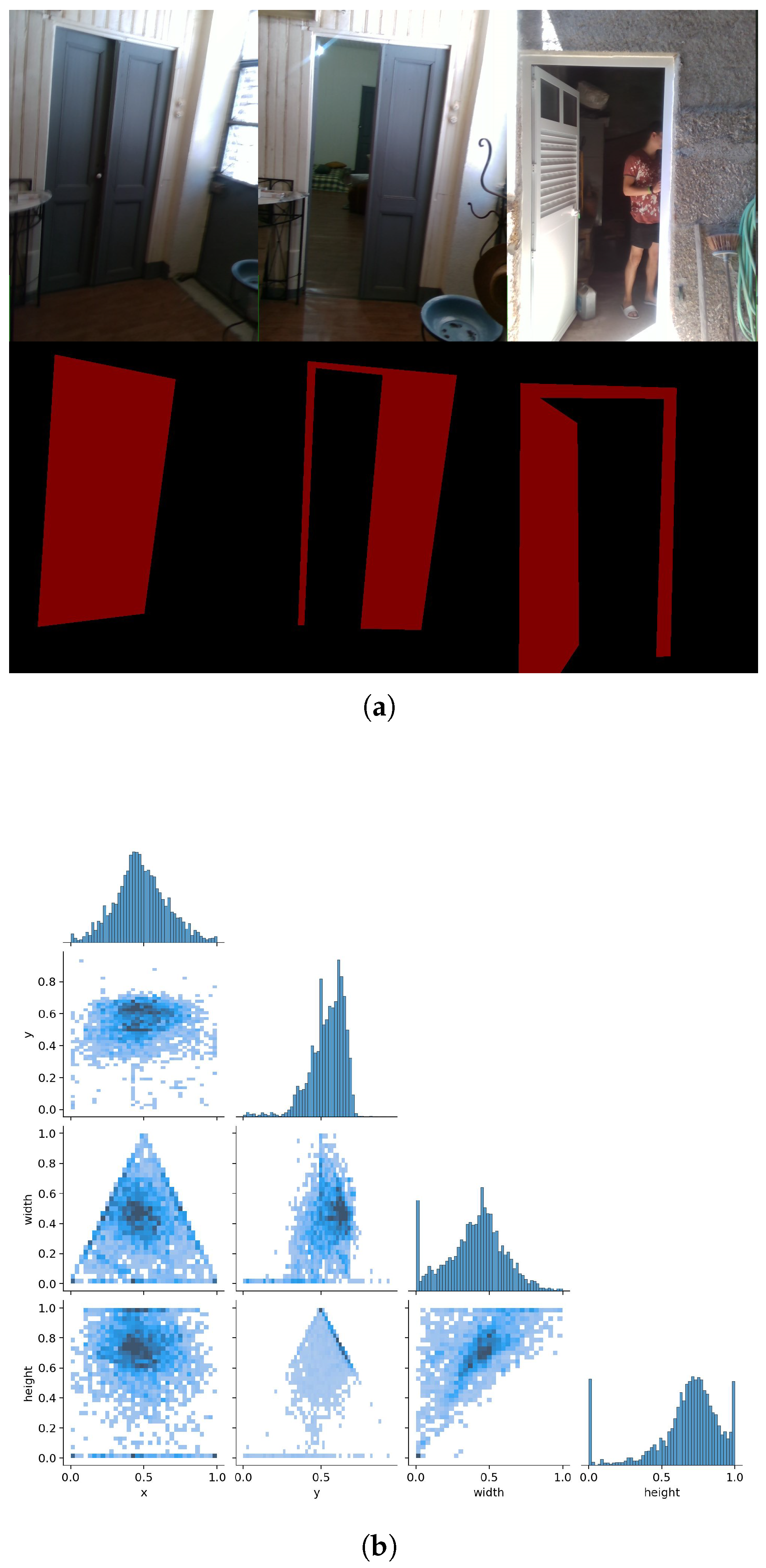

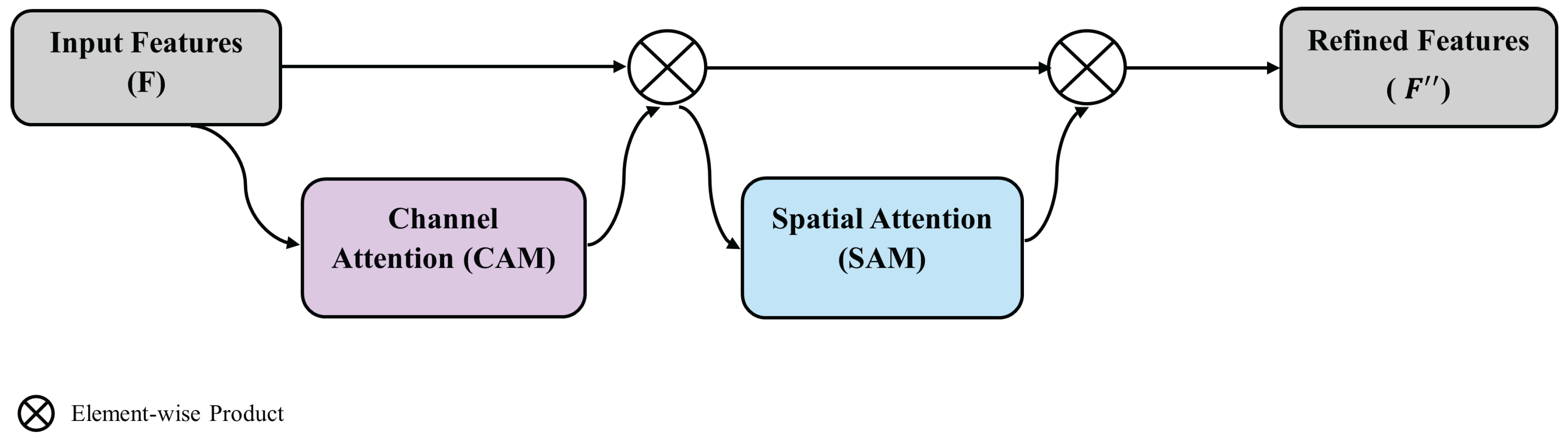

2.2. Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

CBAM was first introduced by Woo et al. in 2018 [

36]. The overall architecture of CBAM is illustrated in

Figure 3. We integrate this CBAM module immediately after the SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling - Fast) layer at the end of the YOLOv8 backbone to enhance the focus of the network on informative spatial and semantic features specific to doorway structures. CBAM is a lightweight and effective attention mechanism that sequentially applies channel attention and spatial attention to the feature map (see

Figure 4), refining its representational quality before feature fusion.

Let be the input feature map output from SPPF. CBAM refines this feature map through two sequential submodules:

- 1)

Channel Attention Module (CAM): This module infers channel-wise importance using both global average pooling (GAP) and global max pooling (GMP), followed by a shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP) [

39] (Equations (

1) and (

2)).

where

,

denotes the sigmoid function, and ⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication.

- 2)

Spatial Attention Module (SAM): This module generates a spatial attention map based on the average and max projections across the channel dimension (Equations (

3) and (

4)).

where

and

represents a convolutional kernel size of

.

The final refined feature map is then passed for further multi-scale fusion. By inserting CBAM at this stage, we allow the network to selectively emphasize features that are structurally and semantically relevant to door detection, improving segmentation accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

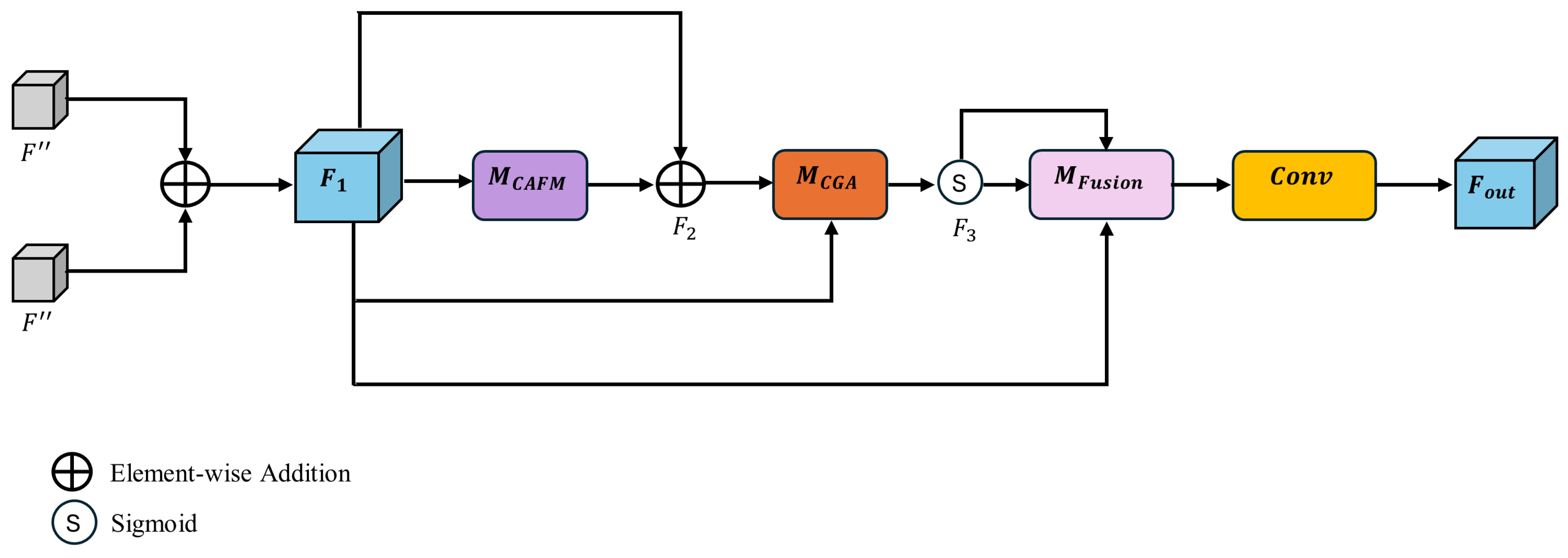

2.3. Content Guided Convolutional Attention Fusion Module (CGCAFusion)

To address the limitations of conventional fusion methods [

40,

41,

42,

43] in detecting structurally small and complex objects such as doorframes, we adopt the CGCAFusion module [

37]. This is a content-guided convolutional attention mechanism designed to enhance both local and global feature modeling with low computational overhead. This mechanism is particularly beneficial for real-time doorway detection in resource-constrained environments.

The module introduces a two-branch fusion strategy (See

Figure 5):

CGA (Content-Guided Attention) [

44]: A coarse-to-fine spatial attention mechanism that refines each feature channel by learning spatial saliency within channels.

CAFM (Convolutional Attention Fusion Module) [

45]: A simplified transformer-inspired structure that extracts global features using self-attention while preserving local features via depthwise convolutions.

The model achieves multimodal feature fusion by dynamically adjusting attention weights according to the input content, enabling fine-grained focus on doorway edges and suppressing irrelevant features.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, given two input tensors

(output from CBAM module), their corresponding elements are first aggregated (Equation (

5)).

where, ⊕ denotes element-wise addition.

The combined feature

is then passed through the CAFM module

to capture global and local relationships (Equation (

6)).

where, ⊕ denotes element-wise addition.

The output

is refined by the CGA module

, which applies spatial, channel, and pixel-level attention to further emphasize critical regions (Equation (

7)).

where, denotes the sigmoid function.

The fusion process concludes with the fusion module

, which performs weighted summation and dimensionality alignment via 1×1 convolution, yielding the final fused output (Equation (

8)).

where, ⊕ denotes element-wise addition.

This output effectively balances global semantic context with local detail, ensuring enhanced segmentation of door structures even under challenging lighting or cluttered backgrounds.

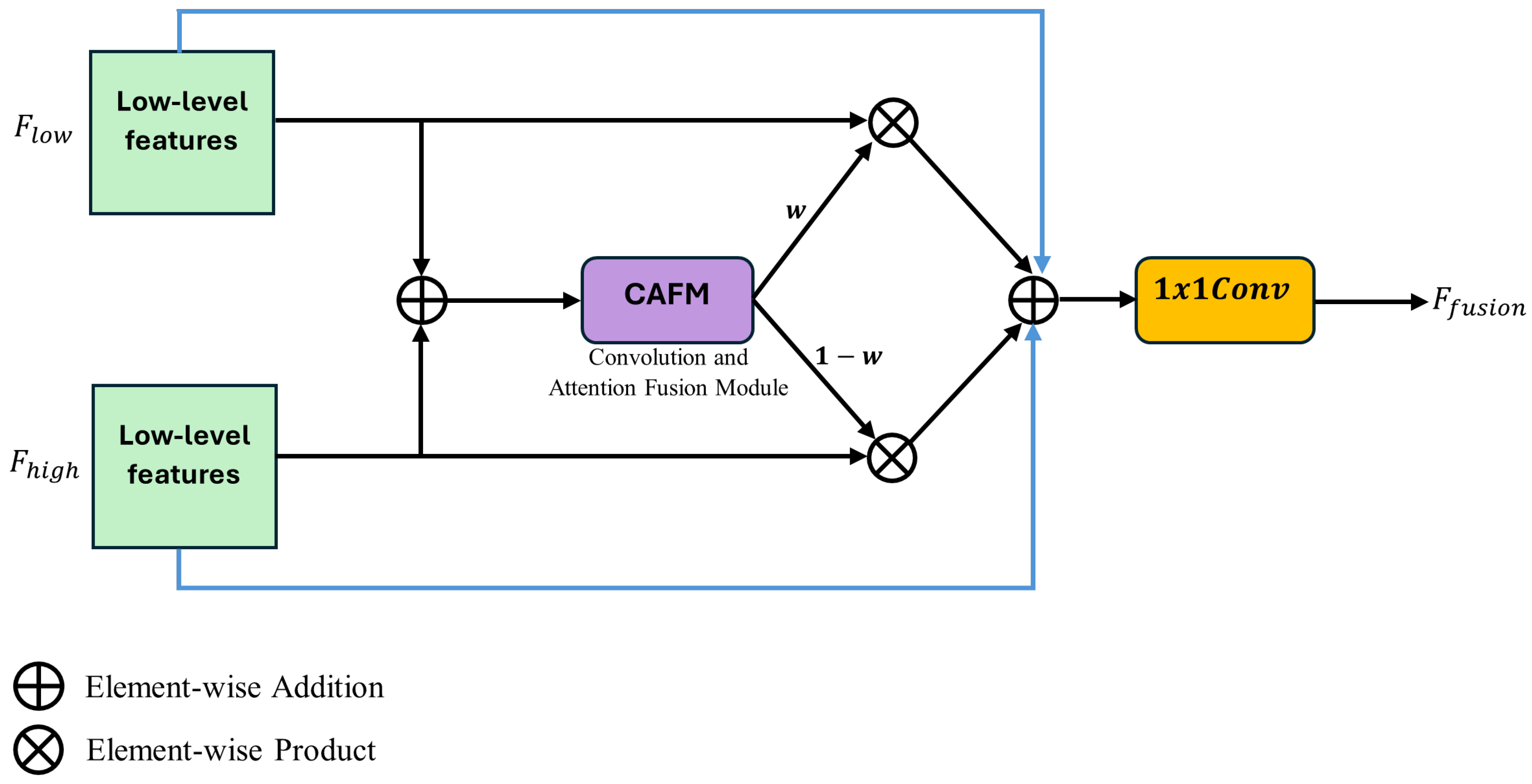

Simultaneously, the pixel attention module dynamically modulates feature importance (low-level and high-level features), guiding the model to concentrate on the most relevant regions within the image. This refined fusion strategy (See

Figure 6) substantially enhances the model’s accuracy and efficiency in real-time detection and segmentation applications (Equation (

9)).

where,

denotes low-level features,

denotes high-level features, and

w denotes feature weights.

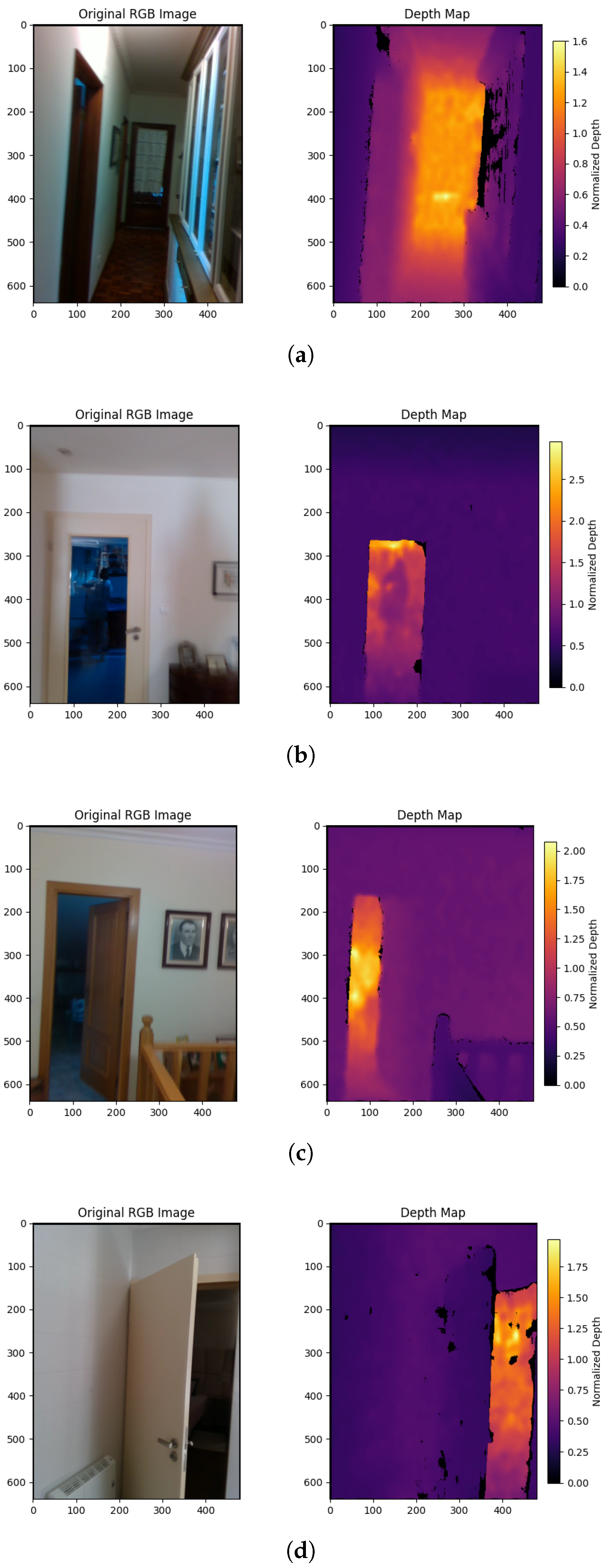

2.4. Depth Estimation Module (DEM)

One of the primary limitations in many existing doorway detection systems is their reliance on external depth sensors such as LiDAR to estimate object proximity. Even though these hardware-based solutions are effective, they increase system cost, complexity, and power consumption, making them less suitable for lightweight mobile platforms such as assistive wheelchairs.

To overcome the limitations of external depth sensors to estimate doorway proximity, we incorporate a lightweight Depth Estimation Module (DEM) that learns to predict relative depth directly from monocular RGB input by unsupervised learning. The module leverages the spatial and semantic features produced by CBAM (

Section 2.2) and CGCAFusion (

Section 2.3) to determine depth. The DEM takes as input the fused feature tensor

generated by the CGCAFusion module, which integrates multi-scale context. This tensor is processed by a shallow convolutional decoder composed of two stacked convolutional layers, batch normalization, and sigmoid activation (Equation (

10)).

The output

is a normalized depth map that captures relative distances within the scene (

Figure 7). This demonstrates that the DEM successfully captures the geometric layout of the environment. In particular, depth continuity is preserved across the doorway regions, while walls and obstacles are well separated in terms of depth gradients. This unsupervised DEM learns to associate visual indicators such as vertical edges, doorway shapes, and floor-wall intersections with depth through context-aware feature propagation.

During the evaluation of the model, we compared the predicted depth values with ground truth maps available in the DeepDoorsv2 dataset using metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE). These comparisons confirm the ability of the model to learn meaningful spatial depth without the need for additional hardware or supervision.

2.5. Alignment Estimation Module (AEM)

One of the key challenges in autonomous wheelchair navigation is not only detecting the presence of doors, but also assessing their relative position and orientation to ensure safe navigation. Traditional vision-based methods tend to stop at detection, lacking the capability to provide directional guidance, such as adjusting to the left or right for optimal alignment. This limitation can result in collisions or failed attempts to navigate through narrow doorways. To address this challenge, we propose an Alignment Estimation Module (AEM) that operates on the output of the segmentation mask to determine the horizontal offset between the doorway center and the center of the camera frame. This offset is used to issue directional guidance to either "Move Left", "Move Right", or "Aligned", based on a predefined tolerance margin.

Let

denote the horizontal center of the frame and

the horizontal center of the detected doorway (bounding box center). The offset is defined as:

A threshold

is used to decide alignment:

The output of the AEM provides interpretable visual guidance cues to the user or control system. By integrating AEM into our pipeline, we bridge the gap between static object detection and actionable mobility decisions, enabling intelligent guidance that is crucial for real-world assistive navigation.

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, we discuss the results obtained by assessing the constructed model in four main areas: structural attention enhancement through CBAM (

Section 3.1), improved precision and semantic fusion using CGCAFusion (

Section 3.2), performance of unsupervised DEM (

Section 3.3), and finally, evaluation of the model’s ability to provide accurate alignment estimation for intelligent guidance (

Section 3.4).

3.1. Structural Attention Enhancement through CBAM

In this section, we discuss the tests performed to evaluate the performance of the CBAM module in improving structural attention. We compared its performance with six state-of-the-art deep learning segmentation approaches: YOLOv5n-seg [

46], YOLOv5s-seg [

46], YOLOv7-seg [

47], YOLOv8n-seg [

48], YOLOv8s-seg [

48], and YOLOv8x-seg [

48].

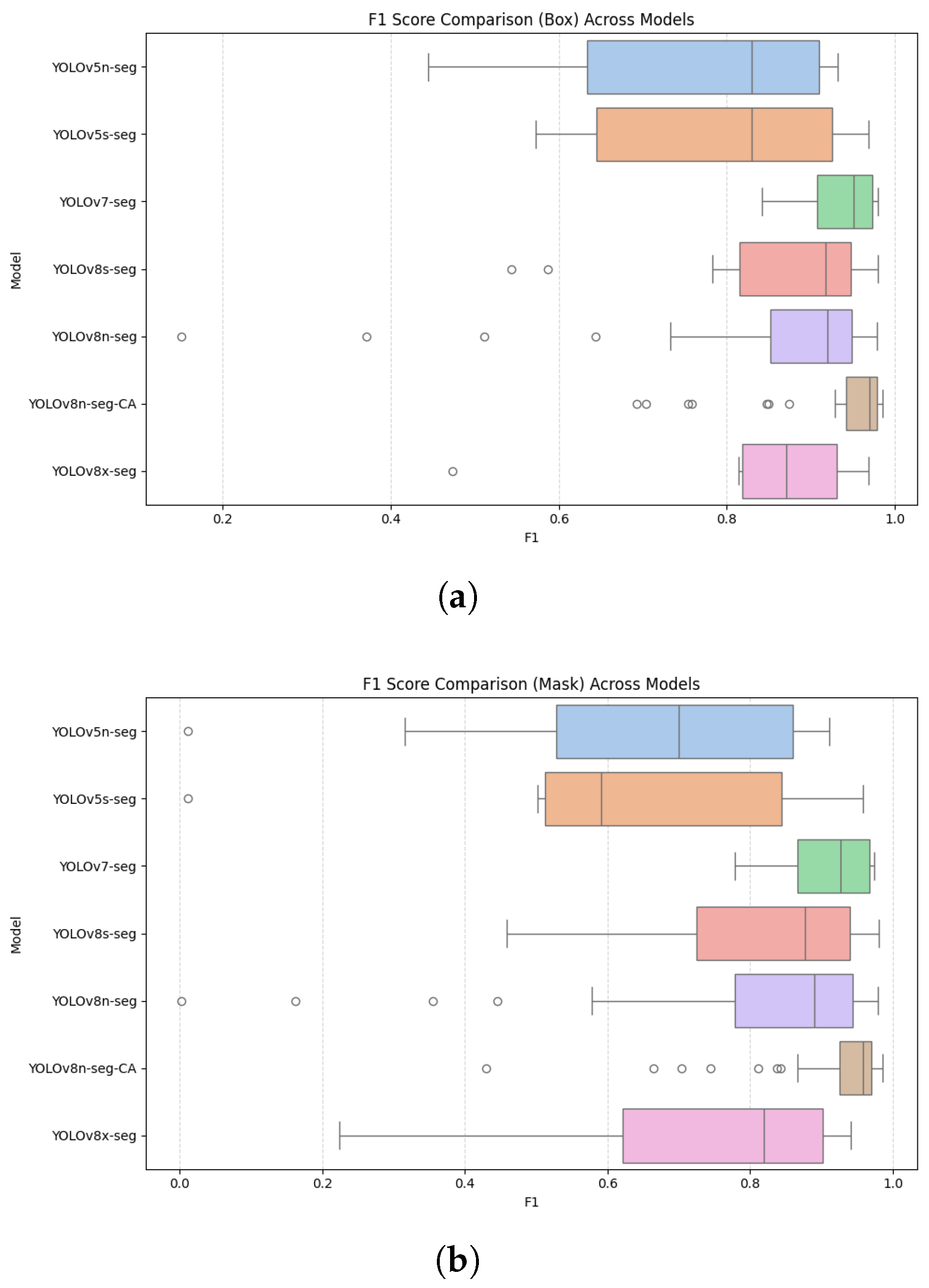

To evaluate the impact of CBAM on the focus of structural characteristics, we focused on two tests to evaluate its performance. Firstly, we compared the F1 scores of the outputs of the bounding box and the segmentation masks (

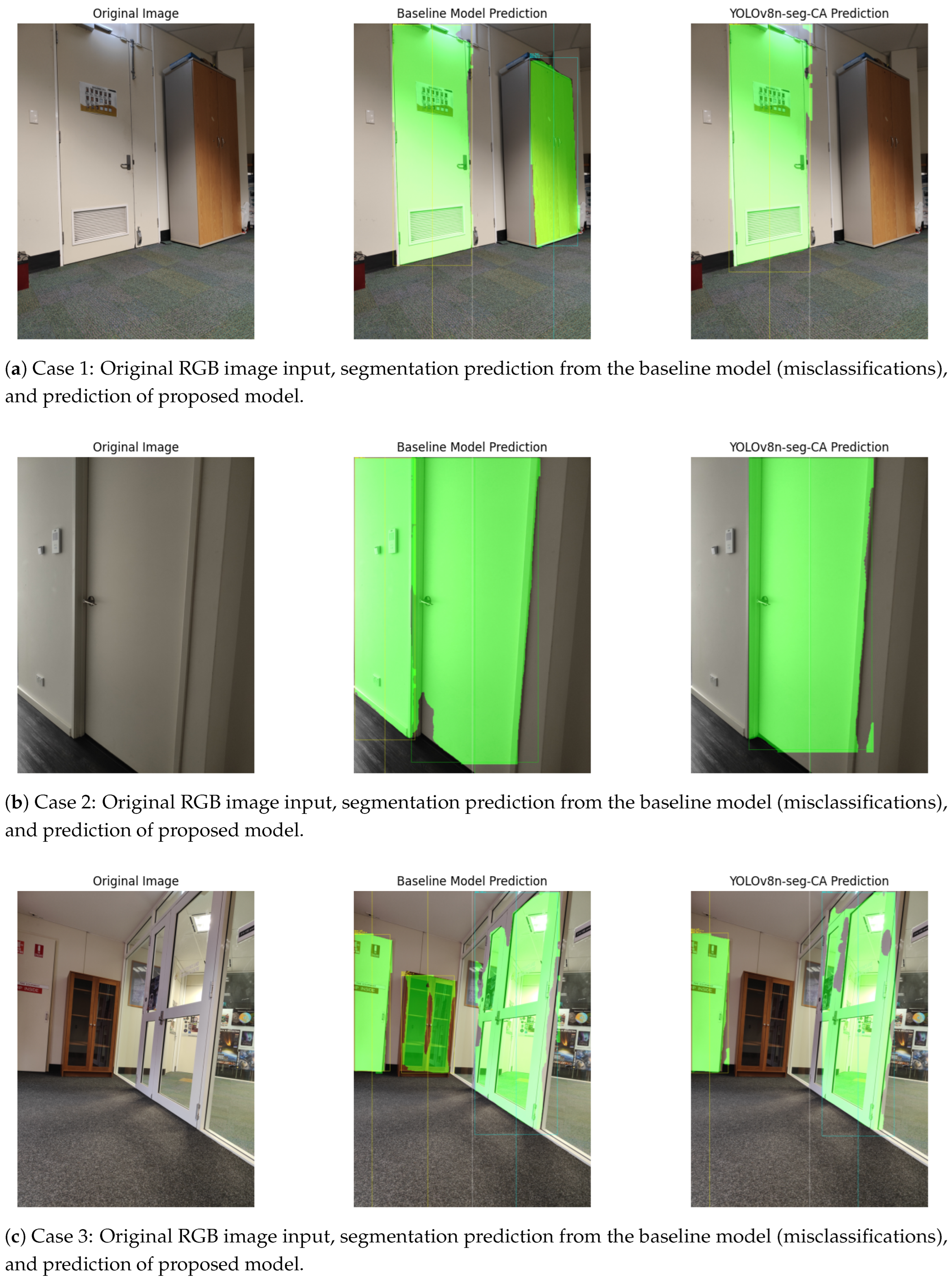

Figure 8). Secondly, we present qualitative results (

Figure 9) to illustrate how CBAM enhances spatial focus by suppressing false positives, compared to the baseline model.

The box plots of the F1 score comparisons (

Figure 8) clearly demonstrate that in both the bounding box and masks, the proposed model (YOLOv8n-seg-CA) consistently outperforms other deep learning models in both accuracy and stability. In particular, YOLOv8n-seg-CA achieves a higher median F1 score and exhibits tighter interquartile ranges, suggesting greater reliability under varied image conditions. Compared to YOLOv8n-seg, which demonstrates a wider dispersion and more outliers, the attention-enhanced version yields more concentrated and stable predictions.

Moreover, the presence of fewer outliers in YOLOv8n-seg-CA indicates robustness to extreme cases, such as partial occlusion or low contrast boundaries. This improvement is critical in wheelchair navigation, where false positives, such as misclassifying walls or furniture as doors, can compromise navigational safety.

The results of the qualitative analysis (

Figure 9) illustrate how CBAM enhances spatial focus by suppressing false positives. In particular, Figures a–c demonstrate three sample cases where baseline models misclassified flat wall surfaces and furniture as doors, which was correctly resolved in our model, highlighting its improved ability to capture the contextual and geometric signals of doorway structures.

Overall, these findings validate the effectiveness of CBAM in enabling the network to focus on meaningful structural cues such as doorway frames, edges, and contours, thus improving both detection precision and generalization.

3.2. Improved Precision and Semantic Fusion using CGCAFusion

In this section, to validate the effectiveness of the proposed CGCAFusion module, we evaluate its performance in terms of both detection accuracy and computational efficiency. We compared its performance with seven state-of-the-art segmentation approaches: Mask R-CNN [

49], YOLOv5n-seg [

46], YOLOv5s-seg [

46], YOLOv7-seg [

47], YOLOv8n-seg [

48], YOLOv8s-seg [

48], and YOLOv8x-seg [

48].

The study uses the YOLOv8n-seg model as the baseline network for improved training. The hyperparameter settings of the training process are outlined in

Table 1. The performance of the model was evaluated using main indicators such as the detection mean average precision mAP(Box), segmentation mean average precision mAP(Mask), parameters, FPS (Frames Per Second), model size, and inference time, as shown in

Table 2.

It is clearly seen that the improved model achieved an average detection and segmentation accuracy of 95.8%, which is 6.2% higher in mAP(Box) and 11% higher in mAP(Mask) compared to the baseline model. This indicates that our model outperforms most existing mainstream algorithms in both detection and segmentation accuracy. Secondly, the improved model achieves a size of 3.6 MB with 2.96 M parameters, an FPS of 1560, and an inference time of 0.42 ms, outperforming other state-of-the-art lightweight algorithms.

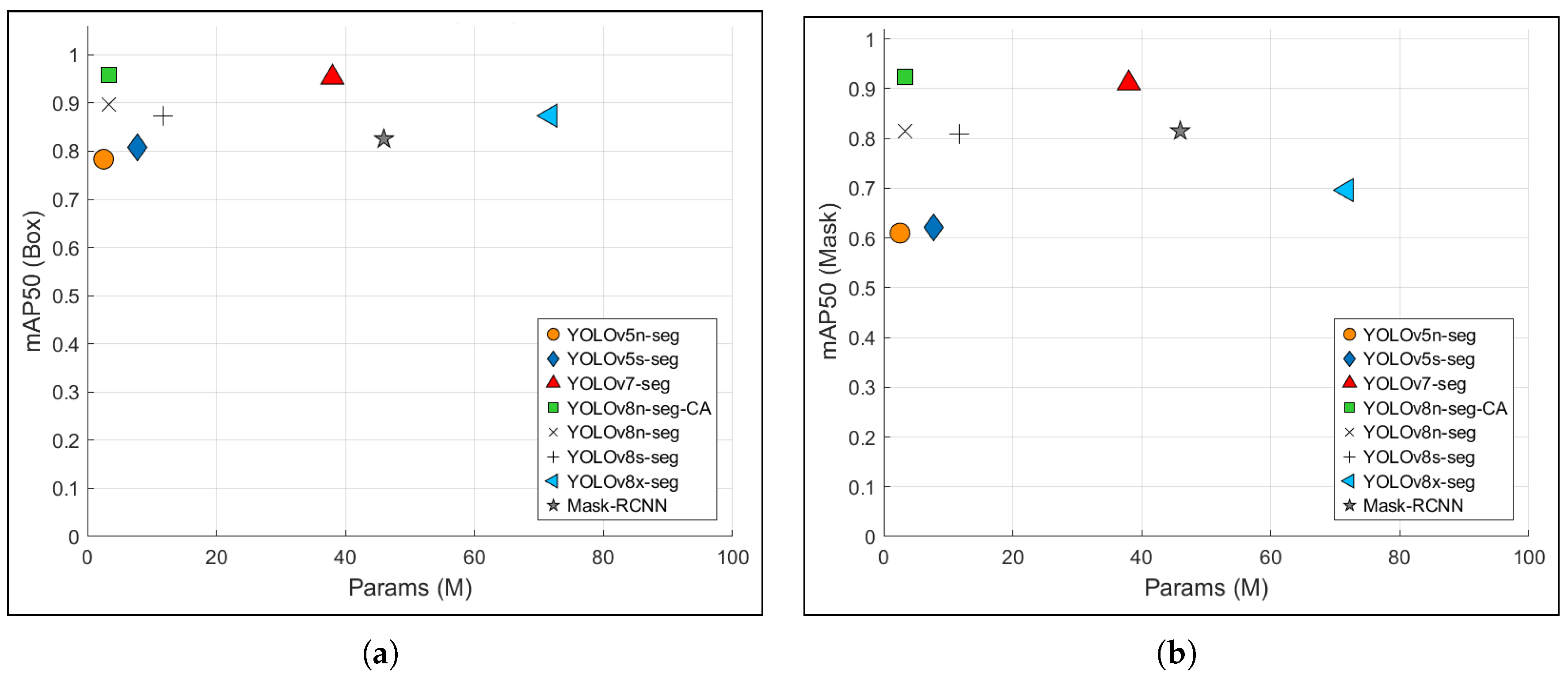

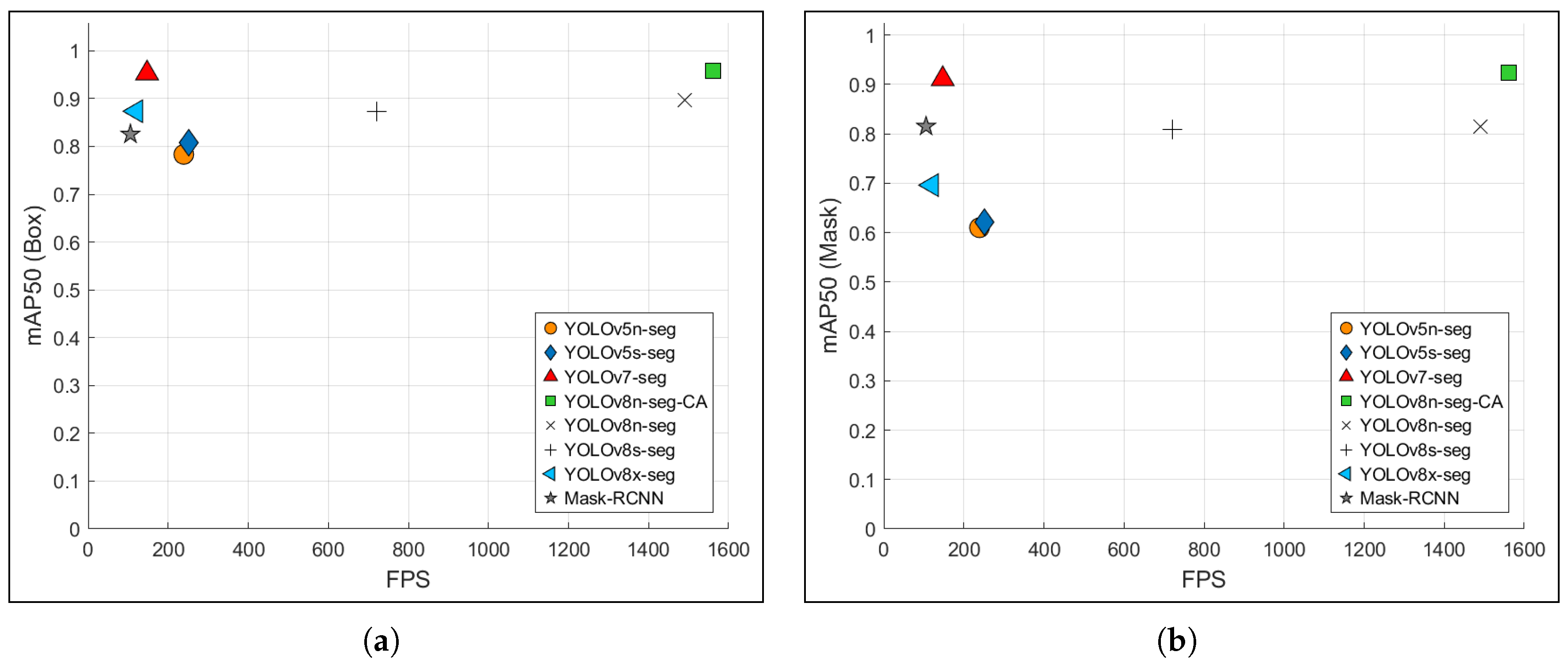

To further illustrate the trade-offs between accuracy and model complexity,

Figure 10 presents a marker plot of mean average precision (mAP50) vs. parameter count, and

Figure 11 demonstrates mAP50 vs. FPS across models. These plots demonstrate that the CGCAFusion module enables more accurate segmentation at a minimal cost to model size or speed. Even though larger models such as YOLOv8x-seg exhibit marginally higher accuracy, they do so at a significant cost in inference speed and memory usage. In contrast, our model remains well-suited for deployment in embedded devices without compromising detection quality.

Overall, it is evident that by fusing contextual information from low- and high-resolution feature maps with a global attention mechanism, CGCAFusion effectively enhances structural awareness while preserving real-time performance, which is a critical requirement in assistive applications such as wheelchair navigation.

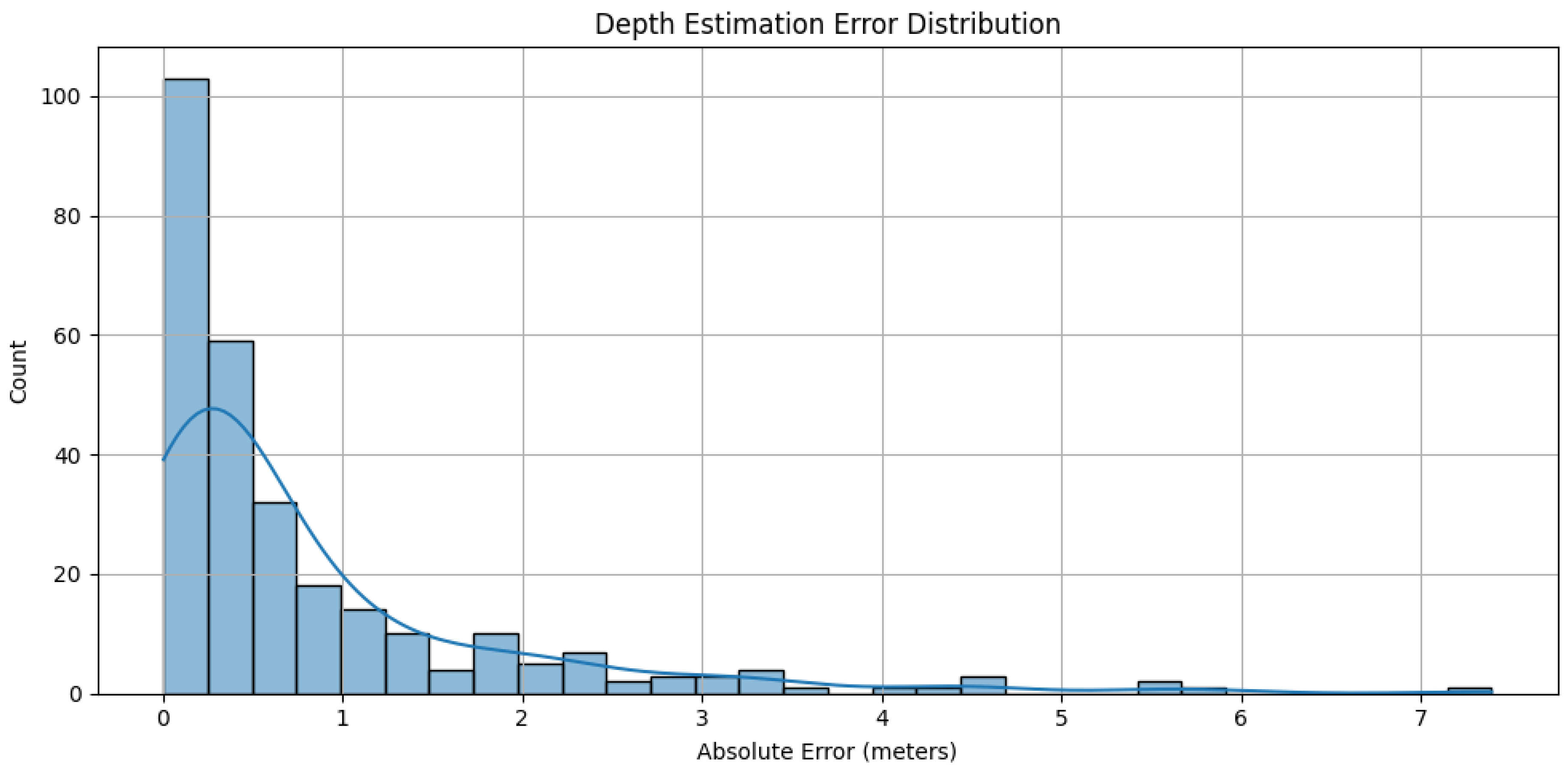

3.3. Performance of Unsupervised DEM

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed DEM, which generates relative depth maps from RGB images without additional hardware or supervision. Unlike conventional sensor-based methods, our approach operates in a fully unsupervised manner using only monocular visual inputs, making it lightweight and cost-effective for deployment on assistive platforms.

Figure 12 presents the distribution of absolute depth estimation errors across the test set. The error histogram exhibits a clear right-skewed profile with a sharp peak in the 0–0.5 meter range, indicating that most predicted depth values closely align with the ground truth values. While the distribution shows a long tail that extends to higher error values, these represent only a small fraction of the total predictions.

These results confirm that the DEM can effectively approximate spatial layout with minimal supervision and without reliance on specialized depth sensors. This performance is achieved through feature representations enriched by the CGCAFusion module, which captures semantic and structural depth cues such as vertical edges and floor-wall intersections. This allows DEM to deliver reliable depth estimates even in indoor scenes with occlusions and varying lighting conditions.

Overall, the DEM demonstrates sufficient precision for guiding alignment decisions and estimating doorway proximity, offering a practical and scalable solution for real-time assistive navigation without sensor-based depth input.

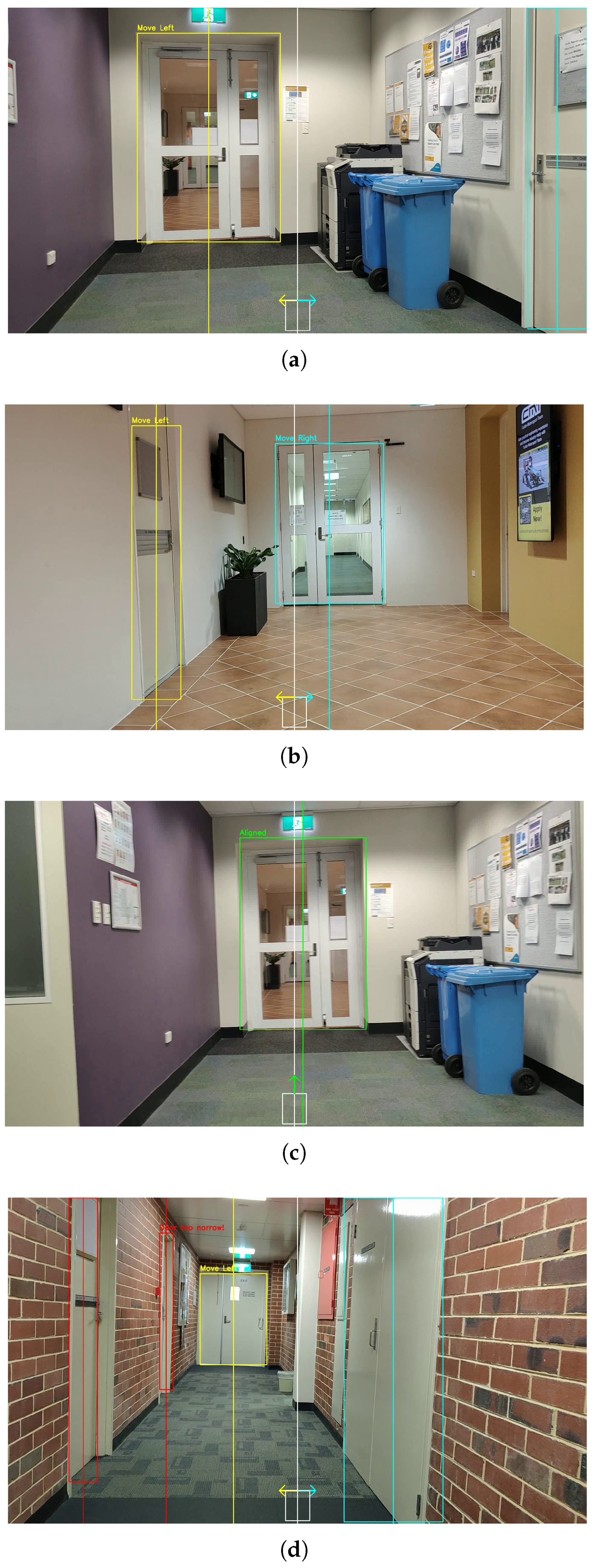

3.4. Accurate Alignment Estimation for Intelligent Guidance

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed AEM, which is designed to provide interpretable navigation cues by estimating the positional alignment of detected doorways relative to the center of the frame. This module enables the system to make actionable decisions such as “Move Left”, “Move Right”, or “Aligned”, which are essential to guide an assistive wheelchair safely and efficiently through constrained spaces.

To validate the effectiveness of AEM, we present four real-world visualizations that demonstrate the directional decision-making of the system in varied indoor environments. As shown in

Figure 13, the module provides discrete alignment decisions, "Move Left", "Move Right", "Aligned", or "Door Too Narrow" based on the relative location and geometry of detected doorways.

Figure 13(a) shows a slightly off-center door, with the left doorpost skewed toward the camera’s centerline. The AEM identifies this misalignment and suggests a “Move Left” adjustment to center the wheelchair. It is evident that the decision is consistent with the actual geometric layout and demonstrates the spatial awareness of the model.

Figure 13(b) illustrates a dual-door scenario where two distinct doorways are detected simultaneously. The AEM correctly evaluates their position with respect to the center of the frame, issuing a “Move Right” instruction for the centrally located door and “Move Left” for the side door. This confirms the module’s ability to disambiguate between multiple doors and provide appropriate direction guidance for each.

Figure 13(c) demonstrates an ideal alignment scenario where the detected door is well centered in the frame and the AEM outputs an “Aligned” message, indicating that no directional adjustment is necessary. In contrast,

Figure 13(d) represents detections of multiple doors in a complex hallway. A narrow door on the left is marked with the warning “Door Too Narrow” due to its insufficient width to allow safe passage. The larger exit door is detected correctly and the module recommends “Move Left” to better center the user.

Overall, the evaluation confirms the robustness of the AEM in issuing interpretable and context-sensitive guidance across varied geometries and lighting conditions. By incorporating spatial thresholds for both alignment and navigability, the module transforms detection into actionable feedback, which is critical for autonomous wheelchair assistance.

In summary, the combination of quantitative metrics and qualitative analyzes confirms the robustness and generalization of our proposed model in diverse indoor environments. The integration of attention mechanisms, semantic fusion, depth estimation, and alignment evaluation enables accurate and interpretable doorway detection, while providing real-time directional guidance. These findings have strong implications for assistive navigation, particularly in enhancing autonomy and safety for wheelchair users by enabling context-aware environmental understanding and decision making.

4. Conclusions

In this research, we propose an enhanced YOLOv8 segmentation model, named YOLOv8n-seg-CA (Context-Aware), designed to detect doorways and guide wheelchair navigation using only RGB input. The model integrates four key components: the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) for refined spatial and channel-wise feature attention, the Content-Guided Convolutional Attention Fusion module (CGCAFusion) for multi-scale semantic feature fusion, a lightweight Depth Estimation Module (DEM) for unsupervised monocular depth prediction, and an Alignment Estimation Module (AEM) that provides real-time directional feedback. Together, these modules improve the model’s ability to interpret complex indoor environments and deliver guidance in real-time—without the need for additional hardware such as LiDAR or depth sensors.

To assess the system’s effectiveness, we conducted extensive evaluations comparing our model with existing baselines. The results showed that YOLOv8n-seg-CA achieves higher segmentation accuracy, lower inference complexity, and enhanced spatial awareness. Qualitative analysis demonstrated the model’s robustness in detecting doorways and assessing safe passage. The system generates intuitive, context-aware commands such as “Move Left,” “Move Right,” or “Aligned,” to support user navigation. The DEM effectively predicted depth in the absence of ground truth, while the AEM translated spatial cues into actionable instructions, making the model particularly suited for unfamiliar or dynamically changing environments.

This vision-based approach offers a practical and scalable solution for assistive technologies. By eliminating the need for heavy or expensive sensor arrays, the proposed system supports lightweight deployment on mobile robotic platforms and smart wheelchairs. Its minimal hardware footprint promotes broader accessibility, especially in low-resource healthcare and rehabilitation settings.

Looking ahead, we plan to enhance the system’s autonomy by incorporating temporal decision smoothing and dynamic obstacle avoidance to better handle moving objects and cluttered environments. Future work will also focus on validating performance across more diverse datasets and real-world architectural settings, particularly those that reflect varying degrees of accessibility. Overall, this research lays a strong foundation for intelligent, vision-based assistive systems that promote safe and autonomous navigation, ultimately improving mobility and independence for individuals with mobility impairments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., N.W., A.W., N.A,. and I.M.; methodology, S.T.; software, S.T.; validation, S.T.; formal analysis, S.T.; resources, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, N.W., A.W., N.A., and I.M.; supervision, N.W., A.W., N.A., and I.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| CBAM |

Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CGCAFusion |

Content Guided Convolutional Attention Fusion Module |

| DEM |

Depth Estimation Module |

| AEM |

Alignment Estimation Module |

| CAM |

Channel Attention Module |

| GAP |

Global Average Pooling |

| GMP |

Global Max Pooling |

| MLP |

Multi-layer Perceptron |

| SAM |

Spatial Attention Module |

| CGA |

Content Guided Attention |

| CAFM |

Convolutional Attention Fusion Module |

| mAP |

Mean Average Precision |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

References

- Dickinson, L. Autonomy and motivation a literature review. System 1995, 23, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. Autonomy and mental health. In Ethical issues in mental health; Springer, 1991; pp. 103–126.

- Mayo, N.E.; Mate, K.K.V. Quantifying Mobility in Quality of Life. In Quantifying Quality of Life: Incorporating Daily Life into Medicine; Wac, K., Wulfovich, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijering, L. Towards meaningful mobility: a research agenda for movement within and between places in later life. Ageing and Society 2021, 41, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.A.; White, R.A.; Flaxman, S.R.; Price, H.; Jonas, J.B.; Keeffe, J.; Leasher, J.; Naidoo, K.; Pesudovs, K.; Resnikoff, S.; et al. Global prevalence of vision impairment and blindness: magnitude and temporal trends, 1990–2010. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 2377–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, T.R.; Jong, M.; Naidoo, K.S.; Sankaridurg, P.; Naduvilath, T.J.; Ho, S.M.; Wong, T.Y.; Resnikoff, S. Global prevalence of visual impairment associated with myopic macular degeneration and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050: systematic review, meta-analysis and modelling. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2018, 102, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwa, K.; of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators, G.B.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2015, 743–800. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J.; Ahn, S.; Park, K.H. Burden of visual impairment and chronic diseases. JAMA ophthalmology 2016, 134, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresova, P.; Javanmardi, E.; Barakovic, S.; Barakovic Husic, J.; Tomsone, S.; Krejcar, O.; Kuca, K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age–a scoping review. BMC public health 2019, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevaswamy, U.; Rohith, M.; Arivazhagan, R. Development of a Semi-Automatic Wheelchair System for Improved Mobility and User Independence. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Automation, Computing and Renewable Systems (ICACRS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, S.; Que, B.; Que, J.; Reyes, L.; Lim, L.G.; Bandala, A.A.; Vicerra, R.R.P.; Dadios, E.P. Design, fabrication, and testing of a semi-autonomous wheelchair. In Proceedings of the 2017IEEE 9th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM). IEEE. 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.; Faisal, F.; Sabrin, S.; Tong, Z.; Hasan, M.; Debnath, D.; Hossain, M.S.; Siddique, A.H.; Alam, J. A Simplified Approach to Develop Low Cost Semi-Automated Prototype of a Wheelchair. InUniversity of Science and Technology Annual (USTA) 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.Y. Wheelchair navigation system for disabled and elderly people. Sensors 2016, 16, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.; Tewkesbury, G.; Stott, I.J.; Robinson, D. Simple expert systems to improve an ultrasonic sensor-system for a tele-operated mobile-robot. Sensor Review 2011, 31, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Duan, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, G.; Li, S.; Yu, Z. Research on distance transform and neural network lidar information sampling classification-based semantic segmentation of 2d indoor room maps. Sensors 2021, 21, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, V.; Shallari, I.; Carratù, M.; Laino, V.; Liguori, C. Design and Characterization of a Powered Wheelchair Autonomous Guidance System. Sensors 2024, 24, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perra, C.; Kumar, A.; Losito, M.; Pirino, P.; Moradpour, M.; Gatto, G. Monitoring Indoor People Presence in Buildings Using Low-Cost Infrared Sensor Array in Doorways. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Choudhury, B. Voice-activated wheelchair: An affordable solution for individuals with physical disabilities. Management Science Letters 2023, 13, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Choudhury, B.B. Autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance in smart robotic wheelchairs. Journal of Decision Analytics and Intelligent Computing 2024, 4, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ess, A.; Schindler, K.; Leibe, B.; Van Gool, L. Object detection and tracking for autonomous navigation in dynamic environments. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2010, 29, 1707–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, Z. Review of ultrasonic ranging methods and their current challenges. Micromachines 2022, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecrosnier, L.; Khemmar, R.; Ragot, N.; Decoux, B.; Rossi, R.; Kefi, N.; Ertaud, J.Y. Deep learning-based object detection, localisation and tracking for smart wheelchair healthcare mobility. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Luo, H.; Wang, Z.; Hui, B.; Chang, Z. The application of improved YOLO V3 in multi-scale target detection. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP). Ieee; 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Pang, M. Position detection of doors and windows based on dspp-yolo. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 10770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandola, F.; Moskewicz, M.; Karayev, S.; Girshick, R.; Darrell, T.; Keutzer, K. Densenet: Implementing efficient convnet descriptor pyramids. arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.1869, arXiv:1404.1869 2014.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochurad, L.; Hladun, Y. Neural network-based algorithm for door handle recognition using RGBD cameras. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Hussain, M. YOLOv5, YOLOv8 and YOLOv10: The Go-To Detectors for Real-time Vision, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2407.02988].

- Wei, L.; Tong, Y. Enhanced-YOLOv8: A new small target detection model. Digital Signal Processing 2024, 153, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Tyagi, R.; Dubey, P. Bridging the Perception Gap A YOLO V8 Powered Object Detection System for Enhanced Mobility of Visually Impaired Individuals. In Proceedings of the 2024 First International Conference on Technological Innovations and Advance Computing (TIACOMP); 2024; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Dinh, T.A.; Choi, M. Enhancing Driving Safety of Personal Mobility Vehicles Using On-Board Technologies. Applied Sciences 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proceedings of the IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennekoon, S.; Wedasingha, N.; Welhenge, A.; Abhayasinghe, N.; Murray Am, I. Advancing Object Detection: A Narrative Review of Evolving Techniques and Their Navigation Applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 50534–50555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp.

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, C. YOLOv8-seg-CP: a lightweight instance segmentation algorithm for chip pad based on improved YOLOv8-seg model. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 27716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramôa, J.; Lopes, V.; Alexandre, L.; Mogo, S. Real-time 2D–3D door detection and state classification on a low-power device. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, R.; Mostaghim, S.; Borgelt, C.; Braune, C.; Steinbrecher, M. Multi-layer perceptrons. In Computational intelligence: a methodological introduction; Springer, 2022; pp. 53–124.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 7132–7141.

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp.

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lau, R.W. Biformer: Vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 10323–10333.

- Xu, W.; Wan, Y. ELA: Efficient local attention for deep convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.01123, arXiv:2403.01123 2024.

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.M. DEA-Net: Single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. Hybrid convolutional and attention network for hyperspectral image denoising. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. YOLOv5 by Ultralytics, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 7464–7475.

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J.; Chaurasia, A. Ultralytics YOLO, 2023.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017; pp. 2961–2969.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the proposed YOLOv8-seg-CA (context-aware) model

Figure 1.

Architecture of the proposed YOLOv8-seg-CA (context-aware) model

Figure 2.

DeepDoorsv2 dataset [

38]: (

a) Sample dataset images of closed, semi-open, and open doors with their corresponding mask (

b) Correlogram of dataset distribution.

Figure 2.

DeepDoorsv2 dataset [

38]: (

a) Sample dataset images of closed, semi-open, and open doors with their corresponding mask (

b) Correlogram of dataset distribution.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of CBAM model

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of CBAM model

Figure 4.

Channel Attention Module and Spatial Attention Module of CBAM

Figure 4.

Channel Attention Module and Spatial Attention Module of CBAM

Figure 5.

Architecture of the CGCAFusion [

37].

Figure 5.

Architecture of the CGCAFusion [

37].

Figure 6.

Architecture of the Fusion Module [

37].

Figure 6.

Architecture of the Fusion Module [

37].

Figure 7.

Depth maps generated by DEM module (a) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of doorway, (b) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a open door, (c) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a semi-open door, and (d) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a semi-open door.

Figure 7.

Depth maps generated by DEM module (a) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of doorway, (b) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a open door, (c) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a semi-open door, and (d) Original RGB image (Left) and predicted normalized depth map (Right) of a semi-open door.

Figure 8.

The proposed model (YOLOv8n-seg-CA) demonstrates consistently high F1 scores with reduced variability compared to baseline methods: (a) F1 score comparison (bounding box) across different segmentation models. (b) F1 score comparison (mask) across different segmentation models.

Figure 8.

The proposed model (YOLOv8n-seg-CA) demonstrates consistently high F1 scores with reduced variability compared to baseline methods: (a) F1 score comparison (bounding box) across different segmentation models. (b) F1 score comparison (mask) across different segmentation models.

Figure 9.

Qualitative comparison of doorway segmentation between the original image, the baseline model, and YOLOv8n-seg-CA model. The enhanced model demonstrates improved boundary accuracy and reduces false positives: (a) Case 1 comparison. (b) Case 2 comparison. (c) Case 3 comparison.

Figure 9.

Qualitative comparison of doorway segmentation between the original image, the baseline model, and YOLOv8n-seg-CA model. The enhanced model demonstrates improved boundary accuracy and reduces false positives: (a) Case 1 comparison. (b) Case 2 comparison. (c) Case 3 comparison.

Figure 10.

Comparison of accuracy and parameters of different segmentation models: (a) Bounding Box. (b) Segmentation Mask.

Figure 10.

Comparison of accuracy and parameters of different segmentation models: (a) Bounding Box. (b) Segmentation Mask.

Figure 11.

Comparison of accuracy and frame rate (FPS) of different segmentation models: (a) Bounding Box. (b) Segmentation Mask.

Figure 11.

Comparison of accuracy and frame rate (FPS) of different segmentation models: (a) Bounding Box. (b) Segmentation Mask.

Figure 12.

Distribution of absolute depth estimation errors produced by the proposed DEM. The histogram shows that most predictions fall within a low error range (0–0.5 meters), with a right-skewed tail indicating occasional higher error outliers

Figure 12.

Distribution of absolute depth estimation errors produced by the proposed DEM. The histogram shows that most predictions fall within a low error range (0–0.5 meters), with a right-skewed tail indicating occasional higher error outliers

Figure 13.

Visual outputs of the proposed AEM across different indoor navigation scenarios. The module provides directional guidance (a) "Move Left", (b) "Move Left/Right" with multiple doors, (c) Alignment confirmation (“Aligned”), and (d) Passability checks (“Door too narrow!”).

Figure 13.

Visual outputs of the proposed AEM across different indoor navigation scenarios. The module provides directional guidance (a) "Move Left", (b) "Move Left/Right" with multiple doors, (c) Alignment confirmation (“Aligned”), and (d) Passability checks (“Door too narrow!”).

Table 1.

Hyperparameter settings.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter settings.

| Parameters |

Value |

| Epochs |

150 |

| Ir0 |

0.002 |

| Irf |

0.002 |

| Momentum |

0.9 |

| Batchsize |

16 |

| Cache |

False |

| Input image size |

640 x 640 |

| Optimizer |

AdamW |

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of segmentation models using metrics, mAP50 Box, Mask, Params, FPS, Model size, and Inference Time.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of segmentation models using metrics, mAP50 Box, Mask, Params, FPS, Model size, and Inference Time.

| Model |

mAP50 (Box) |

mAP50 (Mask) |

Params (M) |

FPS |

Model size (M) |

Inference time (ms) |

| Mask R-CNN |

0.825 |

0.814 |

45.96 |

105.7 |

346.52 |

9.33 |

| YOLOv5n-seg |

0.783 |

0.609 |

2.53 |

239 |

5.14 |

4.62 |

| YOLOv5s-seg |

0.808 |

0.621 |

7.74 |

252.1 |

15.6 |

4.26 |

| YOLOv7-seg |

0.953 |

0.911 |

37.98 |

147.23 |

78.1 |

6.9 |

| YOLOv8n-seg |

0.896 |

0.814 |

3.26 |

1490 |

6.45 |

0.64 |

| YOLOv8s-seg |

0.872 |

0.808 |

11.79 |

720 |

22.73 |

1.39 |

| YOLOv8x-seg |

0.873 |

0.696 |

71.75 |

120 |

137.26 |

8.62 |

| Proposed Model |

0.958 |

0.924 |

2.96 |

1560 |

3.6 |

0.42 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).