1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), especially among infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals. Globally, RSV is estimated to cause approximately 33 million LRTIs annually in children under five years of age, leading to more than 3 million hospital admissions and around 100,000 deaths [

1]. In older adults (≥65 years) and patients with underlying cardiopulmonary or immunosuppressive conditions, RSV contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality, comparable to that seen with non-pandemic influenza [

2].

RSV infection displays a well-characterized seasonal distribution, with peak incidence during the colder months in temperate regions and during the rainy season in tropical climates. Transmission occurs primarily via respiratory droplets and fomites, and the high contagiousness of the virus leads to frequent outbreaks. Despite repeated exposures throughout life, RSV does not induce durable sterilizing immunity, making reinfections common, even in adulthood [

3].

Clinically, RSV infection presents along a spectrum. In infants and young children, it is the most common cause of bronchiolitis and viral pneumonia, with symptoms including cough, wheezing, hypoxemia, and respiratory distress [

4]. Severe cases may require hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care support. In older adults and individuals with chronic conditions, RSV can exacerbate underlying diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or congestive heart failure, leading to significant healthcare utilization [

5].

Recent advances have led to the approval of the first active immunization strategies against RSV, including vaccines targeting older adults and pregnant women to protect infants via transplacental antibody transfer [

6,

7,

8]. In addition, monoclonal antibodies with extended half-lives are now available for passive immunization of neonates during RSV season [

9]. These developments represent major milestones in RSV prevention after decades of research setbacks.

However, therapeutic options remain limited, as no broadly approved antiviral treatment exists, and current clinical management is mainly supportive. Moreover, severe disease is often driven not solely by viral replication, but by the host’s dysregulated immune response, characterized by excessive cytokine production, airway inflammation, and impaired resolution [

10]. RSV has evolved multiple strategies to modulate and evade innate and adaptive immunity, including suppression of type I interferon responses, alteration of dendritic cell function, and skewing of T helper cell responses toward a T helper type 2 cells (Th2)/ T helper type 17 cells (Th17) profile [

11].

Given this complexity, there is growing interest in immunomodulation as a therapeutic approach—either to enhance antiviral defenses in the early phase or to mitigate immune-mediated lung injury in severe cases. Investigating the mechanisms of immune activation and suppression during RSV infection is essential to guide rational development of host-directed therapies, vaccine adjuvants, and disease-modifying interventions.

2. Immune Response to RSV Infection

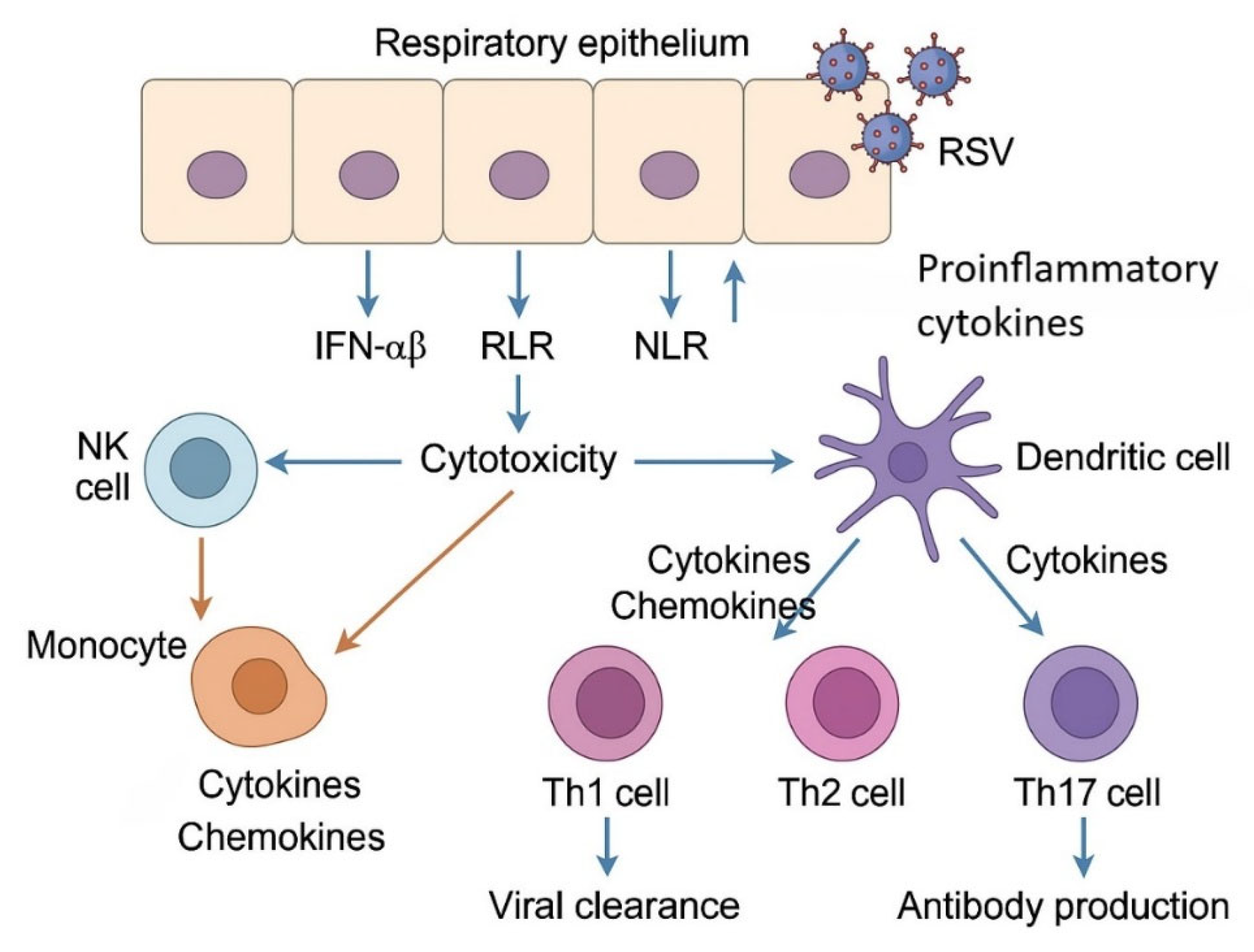

The immune response to RSV infection involves a complex interplay between innate and adaptive mechanisms (

Figure 1).

This diagram illustrates the initial immune recognition of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) by respiratory epithelial cells through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Activation leads to the production of type I interferons (IFN-α/β) and proinflammatory cytokines, which stimulate the recruitment and activation of natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Dendritic cells subsequently prime CD4+ T helper cells (Th1, Th2, Th17), promoting viral clearance, antibody production, and, in severe cases, inflammation. Th1 responses favor viral elimination, while Th2 and Th17 responses are associated with pathology and mucus hypersecretion.

2.1. Innate Immune Response

The innate immune system constitutes the first line of defense against RSV, playing a pivotal role in initial viral control and in shaping downstream adaptive immunity. Upon infection of airway epithelial cells, RSV is recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect viral RNA and replication intermediates. Among these, Toll-like receptors (TLRs)—particularly TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7—are instrumental in sensing RSV. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), TLR4 binds the RSV fusion (F) protein, and TLR7 detects single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) in endosomes [

12,

13]. Simultaneously, cytoplasmic retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors—RIG-I and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5)—bind viral RNA species in the cytosol and activate downstream signaling through mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), culminating in the activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7 (IRF3/7) [

14].

A key consequence of PRR activation is the induction of type I (IFN-α/β) and type III interferons (IFN-λ). These interferons orchestrate an antiviral state by upregulating interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) such as myxovirus resistance protein A (MxA), 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1), and interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), which inhibit viral replication, degrade viral RNA, and enhance antigen presentation [

13,

15]. Notably, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has evolved mechanisms to counteract these responses, primarily through its nonstructural proteins nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) and nonstructural protein 2 (NS2), which suppress type I interferon (IFN) production and signaling by targeting key transcription factors and degrading signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (STAT2) [

16].

Dendritic cells (DCs) are crucial sentinels that bridge innate and adaptive immunity. RSV-infected epithelial cells release cytokines and chemokines such as C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), which recruit dendritic cells (DCs) to the site of infection. Plasmacytoid DCs produce large quantities of type I IFNs, while conventional DCs internalize viral particles and migrate to lymph nodes to prime naive T cells [

17]. However, RSV has been shown to impair DC maturation and antigen presentation, contributing to suboptimal T cell activation [

18].

Macrophages, especially alveolar macrophages, contribute to early viral control by phagocytosing infected cells, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-1β], and producing reactive oxygen species. Their role is double-edged, as excessive activation may contribute to immunopathology [

19]. Similarly, neutrophils, which are rapidly recruited in large numbers to the lungs during RSV infection, release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and proteolytic enzymes (e.g., elastase, myeloperoxidase), which can damage airway tissues and exacerbate disease severity if not tightly regulated [

20].

Overall, the innate immune response to RSV is complex and tightly regulated, involving a balance between antiviral defense and inflammatory damage. While early activation of PRRs and IFNs is essential for viral clearance, RSV-induced modulation of innate pathways contributes to viral persistence and immunopathogenesis.

2.2. Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive immune response to RSV is critical for viral clearance and long-term immune memory but is also implicated in disease severity and immunopathology. Following innate immune activation, antigen-presenting cells, especially dendritic cells, migrate to regional lymph nodes where they activate naïve T and B lymphocytes, initiating the adaptive phase of the immune response.

2.2.1. T Cell Responses

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are essential for clearing RSV-infected cells, particularly in the lungs. These cells recognize viral peptides presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and exert antiviral effects through granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ production [

21]. However, excessive or poorly regulated CD8+ responses can also contribute to tissue damage and airway dysfunction, particularly during primary infection in neonates [

22].

CD4+ T helper cells orchestrate both cellular and humoral immune responses. RSV-specific CD4+ T cells differentiate into various subsets, including Th1, Th2, Th17, and regulatory T cells (Tregs), depending on the cytokine environment and co-stimulatory signals. Th1 cells promote viral clearance via IFN-γ and IL-2 production, while Th2-skewed responses—characterized by IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 secretion—are associated with allergic-type inflammation, eosinophilia, mucus overproduction, and enhanced disease [

23,

24].

The Th17 response, marked by IL-17A and IL-22 production, also contributes to inflammation, neutrophil recruitment, and epithelial barrier modulation in RSV infection. While beneficial for mucosal defense, Th17 activity may exacerbate immunopathology in severe disease [

25].

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) expressing Forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) are critical for limiting immune-mediated lung injury. RSV infection induces Treg expansion, which may prevent excessive inflammation; however, in severe disease, Treg function may be impaired or insufficient. The balance between effector T cells and Tregs is therefore a key determinant of disease outcome [

26,

27].

2.2.2. B Cell and Antibody Responses

B lymphocytes are activated via interaction with follicular helper T cells (Tfh) and differentiate into plasma cells that produce RSV-specific antibodies. Both mucosal IgA and serum IgG play roles in neutralizing the virus and limiting spread. Neutralizing antibodies target key epitopes on the F and attachment (G) glycoproteins of RSV [

28,

29]. High titers of maternal antibodies transferred via the placenta or provided passively are associated with protection in early infancy [

30].

However, RSV has developed mechanisms to impair humoral immunity. The G glycoprotein exhibits structural variability and functions as a decoy receptor for neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, RSV infection can lead to delayed or weak antibody affinity maturation and memory B cell formation, contributing to susceptibility to reinfection [

31].

2.2.3. Suppression of Interferon Signaling

RSV employs its nonstructural proteins, NS1 and NS2, to suppress the host’s IFN response, a central component of innate antiviral defense. NS1 has been shown to inhibit the activation of interferon-stimulated response elements (ISRE) and gamma-activated sequence (GAS) promoters, resulting in decreased expression of ISGs, including MxA, Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 18 (USP18), and ISG15. This suppression is mediated through interference with the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling cascade. Specifically, NS1 impairs STAT1 nuclear translocation by blocking its interaction with the import adapter Karyopherin Subunit Alpha 1 (KPNA1), thereby preventing the transcriptional induction of ISGs downstream of type I IFN receptors [

32].

In addition, both NS1 and NS2 facilitate the degradation of STAT2, a key transcription factor in type I IFN signaling [

33]. The removal of STAT2 by proteasomal degradation severely limits IFN-α/β responsiveness in infected cells and allows for unchecked viral replication during early infection. This degradation is especially effective in airway epithelial cells, where interferon responses are typically robust.

Together, these mechanisms enable RSV to establish early replication niches by blunting the antiviral state normally induced by IFNs. These findings underscore the importance of NS1 and NS2 as key viral immune evasion factors and potential targets for host-directed antiviral strategies [

32,

34].

2.2.4. Modulation of Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs)

RSV has evolved mechanisms to interfere with host PRRs, crucial components of the innate immune system responsible for detecting viral components and initiating antiviral responses. Key PRRs involved in RSV recognition include TLRs and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), such as RIG-I and MDA5.

2.2.4.1. Toll-like Receptors (TLRs)

TLRs, particularly TLR3 and TLR4, play significant roles in recognizing RSV. TLR3 detects double-stranded RNA, a replication intermediate of RSV, while TLR4 recognizes the RSV F protein. Activation of these receptors leads to the production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, RSV can modulate TLR signaling pathways to dampen the immune response. For instance, the RSV G protein has been shown to interfere with TLR4 signaling, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs, thereby facilitating viral persistence [

35,

36].

2.2.4.2. RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs): RIG-I and MDA5

RLRs, including RIG-I and MDA5, are cytoplasmic sensors that detect viral RNA. RIG-I primarily recognizes short double-stranded RNA with 5'-triphosphate ends, while MDA5 detects long double-stranded RNA. Upon recognition, these receptors initiate signaling cascades leading to the production of type I IFNs. RSV can inhibit RLR signaling pathways, thereby suppressing the host's antiviral responses. For example, RSV nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 can interfere with the activation of RIG-I and MDA5, leading to reduced IFN production [

37,

38,

39].

2.2.4.3. Glycoprotein G and CX3CR1 Interaction

The RSV G protein contains a CX3C chemokine motif that mimics the host chemokine fractalkine (CX3CL1), allowing it to bind to the CX3CR1 receptor on immune cells. This interaction can impair the migration and function of CX3CR1-expressing immune cells, such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, thereby modulating the immune response to RSV infection [

40,

41].

2.2.4.4. Inhibition of Dendritic Cell Function

DCs are central to the orchestration of antiviral immunity, acting as key antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that bridge innate and adaptive immune responses. Upon RSV infection, dendritic cells are recruited to the respiratory mucosa, where they capture viral antigens and migrate to draining lymph nodes to prime naïve T cells. However, RSV actively interferes with the function, phenotype, and migration of DCs to suppress effective immune activation [

42,

43].

RSV-infected DCs display impaired maturation, characterized by decreased expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86, and CD83, as well as reduced MHC class II expression [

44]. This immature phenotype leads to inadequate T cell priming and a suboptimal adaptive immune response. Additionally, RSV infection reduces the ability of DCs to secrete IL-12, a cytokine essential for polarizing T cells toward a Th1 antiviral phenotype [

45]. This contributes to the characteristic Th2 bias observed in RSV infection, which is associated with enhanced pathology.

Mechanistically, RSV can alter the expression of C-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7), the chemokine receptor that governs DC migration from peripheral tissues to secondary lymphoid organs. Downregulation of CCR7 expression or altered responsiveness to its ligands [C-C motif chemokine ligand 19 (CCL19) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 21 (CCL21)], results in impaired trafficking of infected DCs to lymph nodes, delaying or weakening the initiation of the adaptive response [

46].

Moreover, RSV-infected DCs may exhibit enhanced expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), an immune checkpoint molecule that engages programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on T cells and contributes to T cell exhaustion and reduced cytokine production [

47]. This further limits T cell proliferation and effector function, allowing viral persistence.

The impairment of DC function represents a crucial immune evasion mechanism, particularly in infants and neonates, whose DCs already exhibit reduced responsiveness due to developmental immaturity. RSV thus exploits both viral and host-derived factors to attenuate DC-mediated immunity, facilitating reinfection and prolonged inflammation.

2.2.4.5. T Cell Dysregulation and Skewing

The outcome of RSV infection is critically influenced by the quality and polarization of the T cell response. While effective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses are required for viral clearance, RSV is known to induce dysregulated T cell immunity, leading to inadequate viral control or excessive inflammation.

A hallmark of RSV infection, particularly in infants, is the skewing of CD4+ T cells toward a Th2 phenotype, characterized by overproduction of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. This Th2-biased response is associated with eosinophilic inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and enhanced disease severity [

48]. The phenomenon was classically illustrated in infants who received a formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine and subsequently developed vaccine-enhanced disease, marked by severe Th2-mediated pathology upon natural infection [

49].

In addition to Th2 dominance, Th17 responses, defined by IL-17A and IL-22 production, are also upregulated in severe RSV cases. While IL-17 can enhance mucosal defense and neutrophil recruitment, uncontrolled Th17 activity contributes to airway hyperreactivity and epithelial damage [

25]. The combination of Th2 and Th17 cytokines forms a non-protective inflammatory milieu that exacerbates lung injury without effectively clearing the virus.

Simultaneously, RSV manipulates T cell function via immune checkpoint pathways. Infected antigen-presenting cells upregulate PD-L1, which interacts with PD-1 on activated T cells, leading to T cell exhaustion, reduced proliferation, and diminished cytokine secretion [

42]. These exhausted T cells exhibit impaired cytotoxicity and memory formation, especially in the CD8+ compartment.

Furthermore, RSV disrupts the balance between effector T cells and Tregs. While Tregs expressing FOXP3 are expanded during infection to suppress excessive inflammation, their suppressive capacity may be inadequate or transient, especially in infants [

26]. This imbalance permits both ineffective viral clearance and unchecked inflammation, further complicating disease resolution.

2.2.4.6. Impairment of Humoral Immunity

The humoral immune response plays a pivotal role in neutralizing RSV and preventing reinfection. However, RSV has evolved several strategies to impair B cell function, evade neutralizing antibodies, and limit long-term protective immunity.

A central mechanism of humoral evasion is the secretion of the soluble form of the G glycoprotein. This secreted decoy mimics the membrane-bound G protein and binds circulating neutralizing antibodies, thereby reducing their availability to engage infectious virions [

50]. In addition, the G protein’s CX3C motif, which structurally mimics the host chemokine fractalkine, interferes with immune cell trafficking and modulates the local cytokine environment, further dampening effective B cell activation [

51].

RSV also limits germinal center (GC) formation in secondary lymphoid tissues. It has been shown that RSV-infected mice and human infants exhibit impaired GC responses, with reduced numbers of Tfh cells and suboptimal B cell proliferation, affinity maturation, and class-switch recombination [

52]. As a result, the antibody repertoire generated during primary infection is often of low affinity, short-lived, and skewed toward non-neutralizing epitopes.

Moreover, RSV infection interferes with memory B cell generation. Even in previously infected individuals, reinfections are common, and the neutralizing antibody titers wane rapidly. RSV can induce the apoptosis of activated B cells and reduce the survival signals necessary for memory cell maintenance, such as IL-21 and B-cell Activating Factor (BAFF) [

31]. These deficiencies explain the lack of sterilizing immunity after natural infection and complicate vaccine design.

Finally, RSV has been shown to modulate the function of plasmablasts and antibody-secreting cells, altering their trafficking patterns and cytokine responsiveness. In severe cases, this contributes not only to insufficient viral neutralization but also to persistent inflammation mediated by immune complexes and complement activation.

Altogether, these strategies enable RSV to escape antibody-mediated immunity and establish recurrent infections, underscoring the need for interventions that can preserve or restore effective B cell responses.

3. Immunopathology and Host Damage

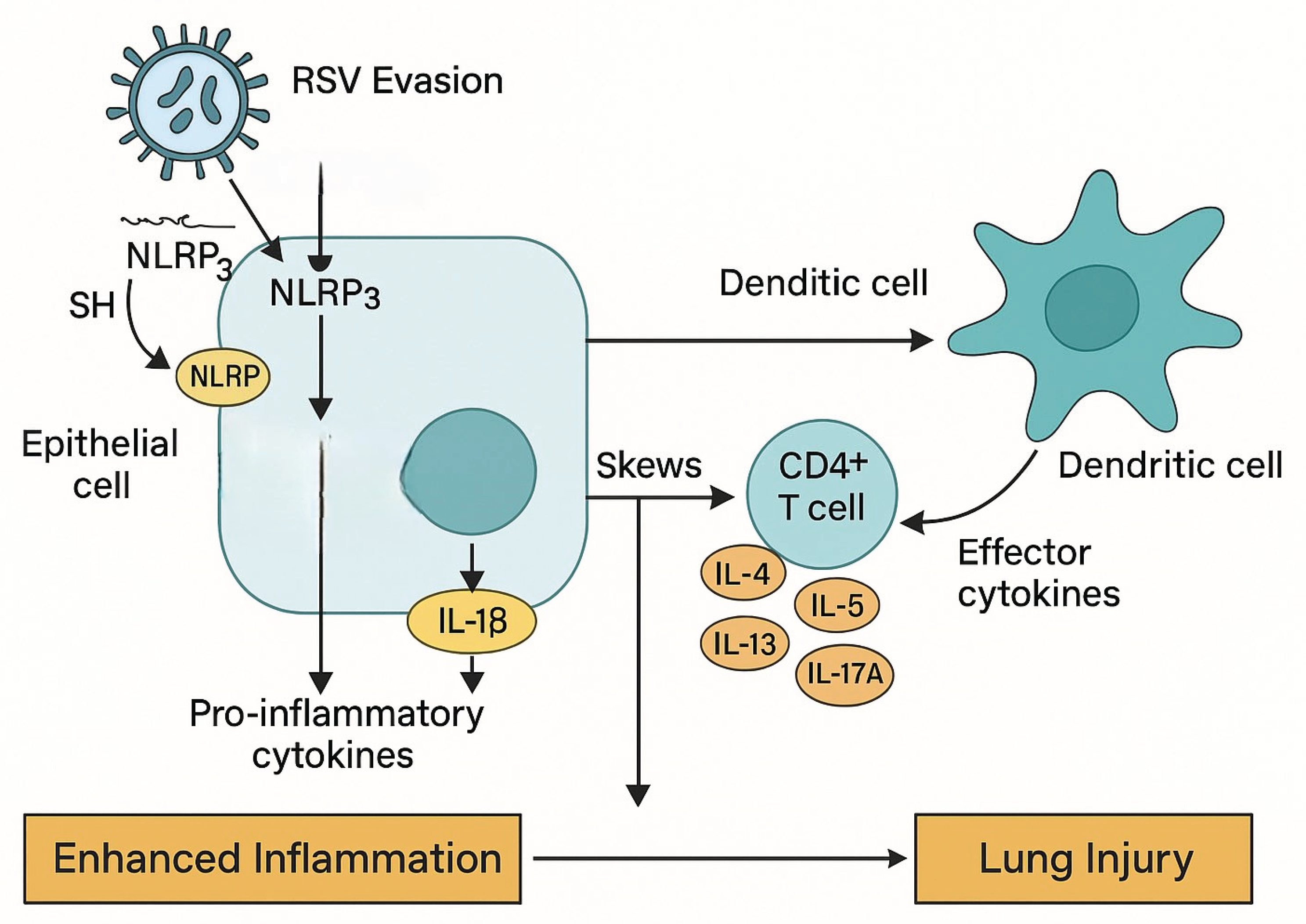

RSV-induced lung injury results from both viral replication and immune-mediated damage through a variety of mechanisms (

Figure 2).

RSV uses multiple strategies to evade host immunity and induce lung injury. The nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 suppress type I interferon responses and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in airway epithelial cells, leading to IL-1β release and enhanced inflammation. Additionally, RSV impairs dendritic cell function, preventing proper T cell priming. CD4+ T cells are skewed toward Th2 and Th17 phenotypes, producing cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17A) that drive eosinophilic inflammation, mucus production, and tissue damage. These processes culminate in enhanced inflammation and long-term lung injury.

3.1. Role of the Immune Response in Lung Injury

While the immune system plays a vital role in the clearance of RSV, dysregulated or excessive immune activation can lead to significant pulmonary injury, particularly in infants and elderly patients. RSV-associated bronchiolitis and pneumonia are frequently not the result of uncontrolled viral replication alone but are also driven by host-derived immunopathological processes.

A key contributor to lung damage is the hyperactivation of innate immune cells, particularly neutrophils, which dominate the cellular infiltrates in the lower respiratory tract during acute RSV infection [

53]. Although neutrophils assist in viral clearance, they also release reactive oxygen species (ROS), proteolytic enzymes, and NETs, which can damage the airway epithelium, promote mucus hypersecretion, and impair gas exchange [

54].

In parallel, monocytes and alveolar macrophages secrete large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, which amplify local inflammation and contribute to vascular leakage, edema, and airway obstruction [

13]. These cytokines also upregulate adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, promoting further immune cell infiltration and worsening the inflammatory cycle.

The adaptive immune response, especially Th2- and Th17-skewed CD4+ T cell responses, contributes to chronic inflammation and tissue remodeling. Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 enhance eosinophilic inflammation and mucus production, while IL-17 from Th17 cells promotes neutrophil recruitment and epithelial barrier dysfunction [

25]. These responses can be protective under tightly regulated conditions but become pathogenic when exaggerated or prolonged.

Histopathological studies of severe RSV cases reveal extensive airway epithelial sloughing, submucosal edema, peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltration, and mucus plugging — features that correlate more strongly with the magnitude of the host immune response than with viral load [

4,

55].

Notably, the age-dependent nature of immunopathology is a hallmark of RSV disease. Neonates and infants exhibit heightened Th2 bias and lower IFN responses, while older adults may experience immune senescence and delayed clearance, both of which predispose to lung injury via different mechanisms [

56].

3.2. Chronic Sequelae and Long-Term Impact of Immunopathology

Beyond acute bronchiolitis and pneumonia, RSV infection—particularly during early life—has been associated with long-term respiratory sequelae, including recurrent wheezing, asthma-like symptoms, and reduced pulmonary function. These outcomes are increasingly understood as consequences of immune-mediated injury and dysregulated repair mechanisms initiated during the acute phase of infection.

Epidemiological studies have shown that severe RSV bronchiolitis in infancy is a strong predictor of recurrent wheezing and asthma in childhood and adolescence [

57]. The underlying pathophysiology appears to involve persistent airway remodeling, initiated by immune-mediated epithelial damage, subepithelial fibrosis, and goblet cell hyperplasia during acute infection [

58]. These structural changes are driven by chronic Th2- and Th17-type inflammation, including the sustained activity of cytokines such as IL-13, IL-17A, and TGF-β, which promote mucus production and fibrosis.

The presence of neutrophil elastase, matrix metalloproteinases, and oxidative stress products in RSV-infected lungs contributes to extracellular matrix degradation and abnormal repair, predisposing the lung to increased airway hyperreactivity and reduced compliance [

25]. In addition, RSV infection may affect the epithelial–mesenchymal trophic unit, further altering developmental trajectories of the airways in infants [

59].

Furthermore, the immunological imprinting that occurs during RSV infection may lead to long-lived alterations in both the innate and adaptive immune compartments. For example, infants who experience severe RSV may develop memory T cell populations skewed toward Th2, which can be reactivated upon later exposures to RSV or other allergens, promoting asthma-like pathology [

60]. These immune imprints may also impair the host’s capacity to respond appropriately to subsequent respiratory infections.

It remains debated whether RSV plays a causal role in asthma development or simply unearths a pre-existing predisposition. However, animal models and human cohort studies support a mechanistic link between early-life RSV immunopathology and later airway disease, particularly in genetically or immunologically susceptible individuals [

61,

62].

3.3. Age-Dependent Differences in Immunopathology

The immunopathological manifestations of RSV infection vary significantly across the lifespan, with the most severe clinical outcomes seen in infants and older adults. These age-dependent differences reflect fundamental variations in immune system development, function, and regulation, which in turn shape the host's capacity to respond to RSV infection and repair tissue injury.

3.3.1. Infants and Young Children

In neonates and infants, the immune system is functionally immature. RSV infection in this age group is characterized by a predominant Th2-type immune response, reduced type I interferon production, and impaired cytotoxic T cell activity [

18]. These deficiencies contribute to inadequate viral clearance and excessive inflammation. In particular, alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells in neonates exhibit lower expression of co-stimulatory molecules and cytokines such as IL-12, leading to poor CD8+ T cell priming [

63,

64].

Moreover, neonates have a limited pool of tissue-resident memory T cells and a bias toward regulatory and tolerogenic immune pathways, likely an evolutionary adaptation to limit inflammation during early development. While this protects against overwhelming immune responses, it renders neonates more susceptible to viral replication and immunopathology mediated by non-protective inflammation, particularly involving Th2 and Th17 cytokines [

65].

The narrow airway caliber, high compliance of lung tissue, and relatively high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in infants also contribute mechanically and immunologically to the severity of bronchiolitis and airway obstruction [

66].

3.3.2. Older Adults

In contrast, older adults experience immune senescence, which affects both innate and adaptive immune compartments. Key features include reduced function of natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, and CD8+ effector memory T cells, as well as impaired interferon responses. These changes result in delayed viral clearance, higher viral loads, and prolonged inflammation [

67].

At the same time, chronic low-grade inflammation—commonly referred to as "inflammaging"—predisposes older adults to exaggerated responses to RSV, including cytokine overproduction and tissue damage, particularly in those with comorbidities like COPD or cardiovascular disease [

68]. The recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes may be less efficient but more damaging due to impaired resolution of inflammation.

Furthermore, antibody responses in older adults are typically weaker and less durable, with limited isotype switching and affinity maturation, compromising protection despite prior exposures [

69].

3.3.3. Implications

These contrasting immunopathological profiles in infants versus the elderly underscore the importance of age-specific approaches to RSV prevention and treatment. Strategies such as maternal immunization, monoclonal antibody prophylaxis for infants, and vaccination of older adults must consider the distinct immunological vulnerabilities of each population [

70].

3.4. Overproduction of Cytokines: Linking Immunopathology to Bronchiolitis and Airway Remodeling

One of the defining features of severe RSV infection is the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. While these mediators are essential for antiviral defense and leukocyte recruitment, their dysregulated release contributes to bronchiolitis, tissue injury, and long-term airway remodeling. RSV-infected airway epithelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells produce elevated levels of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF), along with chemokines including IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1α), CCL5, and CXCL10 [

71,

72,

73]. These molecules orchestrate a robust recruitment of neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and T lymphocytes into the airways.

Among these, IL-8 plays a pivotal role in neutrophil chemotaxis, and its elevated expression has been linked to the dense neutrophilic infiltrates observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of infants with RSV bronchiolitis [

20]. Although neutrophils are critical for limiting viral dissemination, their release of granule contents such as elastase and myeloperoxidase, as well as the formation of NETs, exacerbate epithelial injury and stimulate mucus hypersecretion [

20]. IL-6, a multifunctional cytokine, further amplifies inflammation by promoting acute-phase protein production, enhancing Th17 differentiation, and supporting B cell survival. Importantly, persistently high IL-6 levels have been associated with increased disease severity, prolonged hospitalization, and the need for respiratory support in RSV-infected infants [

73].

The downstream effects of this pro-inflammatory microenvironment include the development of bronchiolitis, which is histologically characterized by epithelial sloughing, mucus plugging, submucosal edema, and small airway obstruction. These changes correlate more strongly with host immune activation than with viral load, indicating a key role for immunopathology in disease progression [

74]. Furthermore, cytokine-mediated disruption of epithelial barrier integrity facilitates viral spread to deeper lung tissues and sustains the cycle of inflammation and injury [

75].

Prolonged inflammation in severe RSV cases leads to airway remodeling, a process that encompasses subepithelial fibrosis, goblet cell hyperplasia, and smooth muscle hypertrophy. IL-13 and IL-17, which are downstream products of Th2 and Th17 polarization respectively, contribute to mucus metaplasia, collagen deposition, and thickening of the airway wall [

76,

77]. These structural changes are particularly concerning infants, as they have been implicated in the development of chronic wheezing and asthma later in life, especially among those hospitalized with severe RSV bronchiolitis [

78].

Taken together, these findings highlight that the overproduction of cytokines represents a critical link between acute RSV infection and both short-term respiratory dysfunction and long-term airway disease. Targeting specific inflammatory pathways—such as those mediated by IL-6, IL-8, IL-13, or IL-17—may offer future therapeutic strategies to reduce immunopathology while preserving effective antiviral immunity.

4. Monoclonal Antibodies

4.1. Palivizumab

Palivizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the A antigenic site of the RSV F protein, thereby inhibiting viral entry into host cells. It is administered intramuscularly monthly during the RSV season and is approved for high-risk infants, including those born prematurely, with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease [

79].

The pivotal IMpact-RSV trial demonstrated that palivizumab prophylaxis reduced RSV-related hospitalizations by 55% in high-risk infants (10.6% in the placebo group vs. 4.8% in the palivizumab group; p<0.001) [

79]. Subsequent studies have corroborated its efficacy, reporting reductions in RSV-related hospitalizations ranging from 45% to 82% in various high-risk pediatric populations [

80].

Despite its demonstrated efficacy, the widespread use of palivizumab is limited by factors such as high cost, the need for multiple doses, and limited applicability to broader infant populations [

81].

4.2. Nirsevimab

Nirsevimab is a long-acting monoclonal antibody designed to provide passive immunity against RSV by targeting a conserved epitope on the prefusion conformation of the F protein. It incorporates YTE (M252Y/S254T/T256E) Fc modifications to extend its half-life, allowing for a single intramuscular dose to offer protection throughout the RSV season [

82].

In the phase 3 MELODY trial, a single dose of nirsevimab reduced the incidence of medically attended RSV-associated LRTIs by 74.5% compared to placebo in healthy late-preterm and term infants during their first RSV season [

82]. Furthermore, a pooled analysis of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies showed that prophylaxis with nirsevimab had an efficacy of 79.5% against medically attended RSV LRTIs [

83].

Real-world data have further supported these findings. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that nirsevimab was 83.2% effective in preventing hospitalization and 75.7% effective in reducing severe RSV cases among infants under one year of age [

84].

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved nirsevimab (marketed as Beyfortus) in July 2023 for the prevention of RSV lower respiratory tract disease in neonates and infants entering their first RSV season. Its single-dose regimen and broader efficacy profile position nirsevimab as a significant advancement in RSV prophylaxis, potentially offering a more practical and effective alternative to palivizumab [

85].

5. Cytokine Modulation and Anti-Inflammatory Agents

RSV infection often leads to an excessive inflammatory response, with marked overproduction of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β, which contribute significantly to lung injury and disease severity. Therapeutic modulation of this cytokine cascade has emerged as a potential approach to limit tissue damage and reduce RSV-related morbidity.

5.1. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone have potent anti-inflammatory effects and are known to inhibit the transcription of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, clinical trials in RSV bronchiolitis have shown inconsistent results. A Cochrane review concluded that corticosteroids do not significantly reduce hospital admissions or length of hospital stay in most infants with RSV bronchiolitis [

86]. Some studies suggested minor benefits in select subgroups but concerns about delayed viral clearance and immunosuppression remain [

87].

5.2. IL-6 Blockade

IL-6 is a key mediator of systemic inflammation and has been shown to correlate with RSV disease severity. In other viral infections such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), IL-6 blockade with tocilizumab has reduced hyperinflammation. Although not yet trialed in RSV, IL-6 inhibition is a rational target in severe RSV given the parallels in cytokine storm pathogenesis [

88]. Elevated IL-6 levels have been associated with worse outcomes in pediatric RSV [

89].

5.3. JAK Inhibitors

The JAK-STAT pathway is central to cytokine signaling for IL-6, IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, and others. Inhibitors such as baricitinib or ruxolitinib have been proposed to modulate this cascade. While clinical trials are lacking in RSV, preclinical models have demonstrated that JAK inhibition can dampen airway inflammation without abolishing antiviral responses [

90]. These agents are being explored in pediatric hyperinflammation syndromes and may represent a future avenue in severe RSV disease [

91].

5.4. IL-1 and NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition

RSV activates the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, leading to maturation and release of IL-1β, which enhances lung inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. Inhibition of NLRP3 using dapansutrile or blockade of IL-1 signaling via anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) has been effective in models of viral lung injury [

92]. While no RSV-specific trials have been conducted yet, these approaches are being investigated in related inflammatory diseases and viral ARDS [

93].

6. Small Molecule Antivirals and Host-Directed Therapies

The therapeutic landscape for RSV has expanded beyond prophylactic monoclonal antibodies to include small molecule antivirals and host-directed therapies. These approaches aim to directly inhibit viral replication or modulate host cellular pathways to mitigate infection severity.

6.1. Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs)

6.1.1. Ribavirin

Ribavirin, a guanosine analog, remains the only antiviral approved for RSV treatment. It inhibits viral RNA synthesis and capping. However, its clinical use is limited due to concerns about efficacy, toxicity, and cost [

94].

6.1.2. Presatovir (GS-5806)

Presatovir is an oral fusion inhibitor targeting the RSV F protein, preventing viral entry into host cells. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled human challenge trial, DeVincenzo et al. [

95] evaluated the efficacy of

GS-5806 (Presatovir)—an oral RSV entry inhibitor—in healthy adults experimentally infected with RSV. Participants were assigned to seven dosing cohorts and received GS-5806 or placebo following confirmed RSV infection or five days post-inoculation. The study demonstrated that GS-5806 significantly reduced viral load (adjusted mean AUC: 250.7 vs. 757.7 log₁₀ PFUe·h/mL;

P<0.001), total mucus production (6.9 g vs. 15.1 g;

P=0.03), and symptom scores (

P=0.005) compared to placebo. Although some adverse events such as transient neutropenia and elevated alanine aminotransferase were more frequent in the treatment group, the drug was generally well tolerated. These findings indicate that GS-5806 can effectively reduce RSV replication and symptom severity in a controlled setting, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent against RSV.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2b study [

96] involving 60 hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients with confirmed RSV lower respiratory tract infection across 17 centers, participants received oral Presatovir 200 mg or placebo every four days for five total doses. The primary endpoint—the time-weighted average change in nasal RSV viral load through day 9—showed no significant difference between the Presatovir and placebo groups (–1.12 vs –1.09 log₁₀ copies/mL; P = 0.94). Secondary outcomes, including supplemental oxygen–free days, incidence of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, and all-cause mortality, also did not differ significantly between arms. Adverse event rates were similar in both groups (80% vs 79%), and resistance-associated substitutions in the RSV fusion protein emerged in 6 of 29 Presatovir-treated patients. The trial concluded that, despite acceptable safety and tolerability, Presatovir did not confer clinical or virologic benefits in this immunocompromised population

6.1.3. Lumicitabine (ALS-8176)

Lumicitabine, a nucleoside analog, inhibits the RSV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. While early studies showed promise, subsequent trials revealed limited efficacy, leading to discontinuation of its development for RSV [

97].

6.1.4. Ziresovir (AK0529)

Ziresovir is a small molecule RSV fusion inhibitor. A phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluated ziresovir in 1–24-month-old children hospitalized with RSV infection, showing that a 5-day oral course significantly improved clinical symptoms (as measured by the Wang bronchiolitis score) by day 3 compared to placebo. Ziresovir also led to a greater reduction in RSV viral load by day 5 (−2.5 vs −1.9 log₁₀ copies/mL), with particularly notable benefits in infants ≤6 months old and those with more severe disease. The treatment was generally well tolerated, with adverse events comparable to placebo and no major safety concerns, supporting ziresovir’s potential as an effective antiviral therapy for RSV bronchiolitis in young children [

98]. Another phase 3 double-blind trial evaluated ziresovir in infants aged ≤6 months hospitalized with confirmed RSV across 28 hospitals in China, showing that a 5-day oral course led to a significantly greater improvement in Wang bronchiolitis clinical scores by day 3 (−3.5 vs −2.2; difference −1.2, p = 0.0004) compared to placebo, with treatment-emergent drug-related adverse events occurring in 18% versus 11% but no serious drug-related events or deaths Moreover, follow-up up to February 4, 2024, suggested durable benefit and a favorable safety profile, reinforcing ziresovir’s clinical potential in this vulnerable age group [

99].

6.1.5. Lonafarnib

Lonafarnib, a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, has demonstrated antiviral activity against RSV by disrupting prenylation processes essential for viral replication. Preclinical studies have shown its efficacy in inhibiting RSV replication in vitro [

100].

6.2. Host-Directed Therapies

6.2.1. Interferon Therapy

RSV evades host immunity in part by suppressing type I and III IFN responses. Administration of exogenous IFN-α or IFN-λ has been shown in vitro and in mouse models to reduce viral load and limit pathology [

101]. However, their clinical utility is constrained by concerns over inflammation and delivery route, and no approved interferon-based therapies currently exist for RSV.

6.2.2. Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) Agonists and Antagonists

TLRs are essential sensors in the antiviral immune response. TLR7/8 agonists, such as imiquimod and resiquimod, activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells and enhance type I IFN production, which suppresses RSV replication in vitro [

100]. Conversely, TLR4 antagonists have been proposed to limit excessive inflammation driven by RSV F protein–TLR4 interaction, especially in severe disease [

102].

6.2.3. Microbiome-Targeted Immunomodulation

The composition of the respiratory and gut microbiota significantly influences host responses to RSV. Infants with severe bronchiolitis often exhibit reduced abundance of commensal genera such as

Corynebacterium and

Dolosigranulum, and increased presence of

Haemophilus and

Streptococcus [

103]. These findings suggest that microbiome-modulating interventions, such as probiotics or microbial metabolite therapies, could potentially reduce disease severity and promote immune balance [

104].

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Balancing Viral Clearance and Immunopathology

A core challenge in RSV immunotherapy is achieving a balance between effective viral clearance and minimizing immune-mediated lung damage. Robust immune activation is necessary to eliminate the virus, yet excessive cytokine production and cellular infiltration, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and T cells, can exacerbate bronchiolitis and contribute to long-term airway remodeling [

71,

105]. Recent reviews underscore that RSV immunopathology results from this delicate equilibrium: too little response allows viral persistence, while too much triggers immunopathology [

105,

106]. Emerging host-directed immunotherapeutic strategies—such as targeted inhibitors of specific cytokines or modulation of innate signaling pathways—show promise in tailoring responses based on individual immune profiles, aiming to preserve antiviral immunity while limiting tissue damage [

107].

7.2. Age- and Comorbidity-Specific Modulation

Immunopathology in RSV infection differs markedly across age groups and comorbid populations. In neonates and young infants, immune responses are skewed toward Th2 and Th17 polarization, accompanied by limited type I interferon production and immature cytotoxic responses, predisposing them to severe bronchiolitis and long-term sequelae [

108,

109]. In contrast, elderly individuals often exhibit immunosenescence, characterized by reduced T cell functionality, impaired memory responses, and a baseline of chronic low-grade inflammation, which together impair viral clearance and contribute to prolonged illness [

110,

111]. Additionally, individuals with underlying comorbidities—such as chronic lung disease, prematurity, or congenital heart disease—demonstrate increased susceptibility to severe RSV outcomes due to both structural and immunological vulnerabilities [

112,

113]. These distinct immunological profiles highlight the need for age-adapted immunotherapies and comorbidity-aware vaccine strategies that can optimize both efficacy and safety across diverse risk groups [

114,

115].

7.3. Long-Term Immunity and Reinfection

Natural RSV infection provides only partial and short-lived immunity, which allows reinfections to occur throughout life, even in individuals previously exposed. This limited protection is largely attributed to the poor durability of humoral immune responses, driven in part by impaired memory B cell formation, suboptimal antibody affinity maturation, and immune evasion by the virus [

28,

31]. Consequently, reinfection is common across all age groups, particularly in infants and older adults. These challenges underscore the need for innovative strategies that promote durable immune imprinting, especially in early life. Approaches such as maternal vaccination, infant immunoprophylaxis (e.g., with long-acting monoclonal antibodies), and booster vaccine schedules must be assessed not only for their ability to confer acute protection during high-risk periods but also for their impact on long-term immune memory and modulation of RSV disease trajectory [

30,

116,

117]. A better understanding of how different immunization strategies shape lifelong immunity will be critical for informing public health policy and vaccine deployment.

7.4. Emerging Technologies

Recent advances in vaccinology have introduced innovative approaches for the prevention and treatment of RSV infection. Among these, mRNA vaccines—particularly those encoding the stabilized prefusion F protein—have garnered attention due to their rapid adaptability, strong immunogenicity, and encouraging safety and efficacy profiles in both animal models and early-phase human trials [

118]. In parallel, nanoparticle-based delivery systems have been developed to enable the co-delivery of antigens and adjuvants, thereby improving mucosal targeting and enhancing cellular immune responses [

119,

120]. Moreover, the integration of systems vaccinology and single-cell transcriptomics has opened new avenues for dissecting the immune response at high resolution, allowing the identification of molecular signatures predictive of protective or pathogenic outcomes [

121]. These tools hold promise for improving patient stratification and guiding the design of personalized immunotherapeutic strategies.

8. Conclusions

RSV represents a persistent global health challenge, not only because of its high transmissibility and recurrent infections, but also due to its ability to manipulate and dysregulate host immune responses. This review underscores that RSV pathogenesis is driven as much by viral factors as by the host's maladaptive immune activation, particularly excessive cytokine release, Th2/Th17 polarization, and impaired IFN signaling. The virus's immune evasion strategies—ranging from interferon suppression to dendritic cell dysfunction and antibody decoy mechanisms—contribute to viral persistence, immunopathology, and long-term respiratory sequelae. Age-specific vulnerabilities in infants and older adults further complicate disease outcomes and therapeutic approaches. Recent breakthroughs in monoclonal antibodies, vaccine development, and emerging immunomodulatory therapies targeting cytokine pathways, inflammasomes, and innate immune receptors offer new hope. However, future efforts must aim to refine these interventions to strike a delicate balance between effective viral clearance and mitigation of immune-mediated tissue damage. Tailoring strategies to age and risk profiles, while enhancing our understanding of RSV-host immune interactions, will be pivotal in reducing the burden of this complex and evolving pathogen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.E.G, V.C.P.; Formal analysis, V.E.G, V.C.P.; Investigation, V.E.G; Methodology, V.E.G, V.C.P.; Supervision, V.C.P.; Validation, V.C.P. Writing—original draft, V.E.G, Writing—review and editing, V.C.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Dovizio M, Veronesi C, Bartolini F, Cavaliere A, Grego S, Pagliaro R, Procacci C, Ubertazzo L, Bertizzolo L, Muzii B, Parisi S, Perrone V, Baraldi E, Bozzola E, Mosca F, Esposti LD. Clinical and economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus in children aged 0-5 years in Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2024 Mar 25;50(1):57. [CrossRef]

- Alfano F, Bigoni T, Caggiano FP, Papi A. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Older Adults: An Update. Drugs Aging. 2024 Jun;41(6):487-505. [CrossRef]

- Kaler J, Hussain A, Patel K, Hernandez T, Ray S. Respiratory Syncytial Virus: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathophysiology, and Manifestation. Cureus. 2023 Mar 18;15(3):e36342. [CrossRef]

- Welliver, R.C., 2003. Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. The Journal of Pediatrics, 143(5), pp.S112–S117. [CrossRef]

- Lee, N., Lui, G.C., Wong, K.T., Li, T.C., Tse, E.C., Chan, J.Y., Yu, J., Wong, S.S., Choi, K.W., Wong, R.Y. and Hui, D.S., 2020. High morbidity and mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(3), pp.500–507. [CrossRef]

- Falsey AR, Williams K, Gymnopoulou E, Bart S, Ervin J, Bastian AR, Menten J, De Paepe E, Vandenberghe S, Chan EKH, Sadoff J, Douoguih M, Callendret B, Comeaux CA, Heijnen E; CYPRESS Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of an Ad26.RSV.preF-RSV preF Protein Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023 Feb 16;388(7):609-620. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh EE, Pérez Marc G, Zareba AM, Falsey AR, Jiang Q, Patton M, Polack FP, Llapur C, Doreski PA, Ilangovan K, Rämet M, Fukushima Y, Hussen N, Bont LJ, Cardona J, DeHaan E, Castillo Villa G, Ingilizova M, Eiras D, Mikati T, Shah RN, Schneider K, Cooper D, Koury K, Lino MM, Anderson AS, Jansen KU, Swanson KA, Gurtman A, Gruber WC, Schmoele-Thoma B; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. Efficacy and Safety of a Bivalent RSV Prefusion F Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023 Apr 20;388(16):1465-1477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, Lee DG, Leroux-Roels I, Martinon-Torres F, Schwarz TF, van Zyl-Smit RN, Campora L, Dezutter N, de Schrevel N, Fissette L, David MP, Van der Wielen M, Kostanyan L, Hulstrøm V; AReSVi-006 Study Group. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(7):595-608. [CrossRef]

- Touati S, Debs A, Morin L, Jule L, Claude C, Tissieres P; PANDORA study group. Nirsevimab prophylaxis on pediatric intensive care hospitalization for severe acute bronchiolitis: a clinical and economic analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2025 Apr 26;15(1):56. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron HC, Tripp RA. Immunopathology of RSV: An Updated Review. Viruses. 2021 Dec 10;13(12):2478. [CrossRef]

- Villenave R, Shields MD, Power UF. Respiratory syncytial virus interaction with human airway epithelium. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21(5):238-44. [CrossRef]

- Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, Haynes LM, Jones LP, Tripp RA, Walsh EE, Freeman MW, Golenbock DT, Anderson LJ, Finberg RW. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(5):398-401. [CrossRef]

- Marr N, Turvey SE. Role of human TLR4 in respiratory syncytial virus-induced NF-κB activation, viral entry and replication. Innate Immun. 2012;18(6):856-65. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Jamaluddin M, Li K, Garofalo RP, Casola A, Brasier AR. Retinoic acid-inducible gene I mediates early antiviral response and Toll-like receptor 3 expression in respiratory syncytial virus-infected airway epithelial cells. J Virol. 2007;81(3):1401-11. [CrossRef]

- Okabayashi T, Kariwa H, Yokota S, Iki S, Indoh T, Yokosawa N, Takashima I, Tsutsumi H, Fujii N. Cytokine regulation in SARS coronavirus infection compared to other respiratory virus infections. J Med Virol. 2006 Apr;78(4):417-24. [CrossRef]

- Lo MS, Brazas RM, Holtzman MJ. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 mediate inhibition of Stat2 expression and alpha/beta interferon responsiveness. J Virol. 2005 Jul;79(14):9315-9. [CrossRef]

- Goritzka M, Makris S, Kausar F, Durant LR, Pereira C, Kumagai Y, Culley FJ, Mack M, Akira S, Johansson C. Alveolar macrophage-derived type I interferons orchestrate innate immunity to RSV through recruitment of antiviral monocytes. J Exp Med. 2015 May 4;212(5):699-714. [CrossRef]

- Ruckwardt TJ, Morabito KM, Graham BS. Immunological Lessons from Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine Development. Immunity. 2019;51(3):429-442. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, Rao L, Duo Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 May 22;8(1):207. [CrossRef]

- Sebina I, Phipps S. The Contribution of Neutrophils to the Pathogenesis of RSV Bronchiolitis. Viruses. 2020;12(8):808. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt ME, Varga SM. The CD8 T Cell Response to Respiratory Virus Infections. Front Immunol. 2018 Apr 9;9:678. [CrossRef]

- Ruckwardt TJ, Malloy AM, Morabito KM, Graham BS. Quantitative and qualitative deficits in neonatal lung-migratory dendritic cells impact the generation of the CD8+ T cell response. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(2):e1003934. [CrossRef]

- Openshaw PJ, Chiu C. Protective and dysregulated T cell immunity in RSV infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2013 Aug;3(4):468-74. [CrossRef]

- Monick MM, Powers LS, Hassan I, Groskreutz D, Yarovinsky TO, Barrett CW, Castilow EM, Tifrea D, Varga SM, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory syncytial virus synergizes with Th2 cytokines to induce optimal levels of TARC/CCL17. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1648-58. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee S, Lindell DM, Berlin AA, Morris SB, Shanley TP, Hershenson MB, Lukacs NW. IL-17-induced pulmonary pathogenesis during respiratory viral infection and exacerbation of allergic disease. Am J Pathol 2011;179(1):248-58. [CrossRef]

- Lee DC, Harker JA, Tregoning JS, Atabani SF, Johansson C, Schwarze J, Openshaw PJ. CD25+ natural regulatory T cells are critical in limiting innate and adaptive immunity and resolving disease following respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol. 2010;84(17):8790-8. [CrossRef]

- Jagger A, Shimojima Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Regulatory T cells and the immune aging process: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60(2):130-7. [CrossRef]

- Ngwuta JO, Chen M, Modjarrad K, Joyce MG, Kanekiyo M, Kumar A, Yassine HM, Moin SM, Killikelly AM, Chuang GY, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Rundlet EJ, Sastry M, Stewart-Jones GB, Yang Y, Zhang B, Nason MC, Capella C, Peeples ME, Ledgerwood JE, McLellan JS, Kwong PD, Graham BS. Prefusion F-specific antibodies determine the magnitude of RSV neutralizing activity in human sera. Sci Transl Med. 2015 Oct 14;7(309):309ra162. [CrossRef]

- Magro, M., Mas, V., Chappell, K., Vazquez, M., Cano, O., Luque, D., Terron, M.C., Melero, J.A. and Palomo, C., 2012. Neutralizing antibodies against the preactive form of respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein offer unique possibilities for clinical intervention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(8), pp.3089–3094. [CrossRef]

- Muňoz FM, Swamy GK, Hickman SP, Agrawal S, Piedra PA, Glenn GM, Patel N, August AM, Cho I, Fries L. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion (F) Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine in Healthy Third-Trimester Pregnant Women and Their Infants. J Infect Dis. 2019 ;220(11):1802-1815. [CrossRef]

- Habibi MS, Jozwik A, Makris S, Dunning J, Paras A, DeVincenzo JP, de Haan CA, Wrammert J, Openshaw PJ, Chiu C; Mechanisms of Severe Acute Influenza Consortium Investigators. Impaired Antibody-mediated Protection and Defective IgA B-Cell Memory in Experimental Infection of Adults with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 May 1;191(9):1040-9.

- Efstathiou C, Zhang Y, Kandwal S, Fayne D, Molloy EJ, Stevenson NJ. Respiratory syncytial virus NS1 inhibits anti-viral Interferon-α-induced JAK/STAT signaling, by limiting the nuclear translocation of STAT1. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1395809. [CrossRef]

- Lo MS, Brazas RM, Holtzman MJ. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural proteins NS1 and NS2 mediate inhibition of Stat2 expression and alpha/beta interferon responsiveness. J Virol. 2005;79(14):9315-9. [CrossRef]

- Hijano DR, Vu LD, Kauvar LM, Tripp RA, Polack FP, Cormier SA. Role of Type I Interferon (IFN) in the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Immune Response and Disease Severity. Front Immunol. 2019;10:566. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron HC, Tripp RA. Immunopathology of RSV: An Updated Review. Viruses. 2021;13(12):2478. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang Y, Liao H, Hu Y, Luo K, Hu S, Zhu H. Innate Immune Evasion by Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:865592. [CrossRef]

- Pei J, Wagner ND, Zou AJ, Chatterjee S, Borek D, Cole AR, Kim PJ, Basler CF, Otwinowski Z, Gross ML, Amarasinghe GK, Leung DW. Structural basis for IFN antagonism by human respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(10):e2020587118. [CrossRef]

- Ling Z, Tran KC, Teng MN. Human respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein NS2 antagonizes the activation of beta interferon transcription by interacting with RIG-I. J Virol. 2009 Apr;83(8):3734-42. [CrossRef]

- da Silva RP, Thomé BL, da Souza APD. Exploring the Immune Response against RSV and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(9):1223. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Fuentes S, Salgado-Aguayo A, Santos-Mendoza T, Sevilla-Reyes E. The Role of the CX3CR1-CX3CL1 Axis in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and the Triggered Immune Response. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Sep 11;25(18):9800. [CrossRef]

- Anderson J, Do LAH, van Kasteren PB, Licciardi PV. The role of respiratory syncytial virus G protein in immune cell infection and pathogenesis. EBioMedicine. 2024;107:105318. [CrossRef]

- Tognarelli EI, Bueno SM, González PA. Immune-Modulation by the Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Focus on Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:810. [CrossRef]

- Jang S, Smit J, Kallal LE, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus infection modifies and accelerates pulmonary disease via DC activation and migration. J Leukoc Biol. 2013 Jul;94(1):5-15. [CrossRef]

- McDermott DS, Weiss KA, Knudson CJ, Varga SM. Central role of dendritic cells in shaping the adaptive immune response during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Future Virol. 2011;6(8):963-973. [CrossRef]

- Jung HE, Kim TH, Lee HK. Contribution of Dendritic Cells in Protective Immunity against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Viruses. 2020;12(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Goritzka M, Makris S, Kausar F, Durant LR, Pereira C, Kumagai Y, Culley FJ, Mack M, Akira S, Johansson C. Alveolar macrophage-derived type I interferons orchestrate innate immunity to RSV through recruitment of antiviral monocytes. J Exp Med. 2015;212(5):699-714. [CrossRef]

- Telcian AG, Laza-Stanca V, Edwards MR, Harker JA, Wang H, Bartlett NW, Mallia P, Zdrenghea MT, Kebadze T, Coyle AJ, Openshaw PJ, Stanciu LA, Johnston SL. RSV-induced bronchial epithelial cell PD-L1 expression inhibits CD8+ T cell nonspecific antiviral activity. J Infect Dis. 2011 Jan 1;203(1):85-94. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee S, Lukacs NW. Association of IL-13 in respiratory syncytial virus-induced pulmonary disease: still a promising target. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010 Jun;8(6):617-21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Yang J, Zhao Y, Shan J, Wang L, Yang G, He S, Li E. RSV Infection in Neonatal Mice Induces Pulmonary Eosinophilia Responsible for Asthmatic Reaction. Front Immunol. 2022 Feb 2;13:817113. [CrossRef]

- Bukreyev A, Yang L, Fricke J, Cheng L, Ward JM, Murphy BR, Collins PL. The secreted form of respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein helps the virus evade antibody-mediated restriction of replication by acting as an antigen decoy and through effects on Fc receptor-bearing leukocytes. J Virol. 2008 Dec;82(24):12191-204. [CrossRef]

- Tripp RA, Jones LP, Haynes LM, Zheng H, Murphy PM, Anderson LJ. CX3C chemokine mimicry by respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein. Nat Immunol. 2001 Aug;2(8):732-8. [CrossRef]

- Russell CD, Unger SA, Walton M, Schwarze J. The Human Immune Response to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(2):481-502. [CrossRef]

- Geerdink RJ, Pillay J, Meyaard L, Bont L. Neutrophils in respiratory syncytial virus infection: A target for asthma prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Oct;136(4):838-47. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Inflammatory responses to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection and the development of immunomodulatory pharmacotherapeutics. Curr Med Chem 2012;19(10):1424-31. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JE, Gonzales RA, Olson SJ, Wright PF, Graham BS. The histopathology of fatal untreated human respiratory syncytial virus infection. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(1):108-19. [CrossRef]

- Graham BS. Biological challenges and technological opportunities for respiratory syncytial virus vaccine development. Immunol Rev. 2011;239(1):149-66. [CrossRef]

- Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 May;161(5):1501-7. [CrossRef]

- Lukacs NW, Moore ML, Rudd BD, Berlin AA, Collins RD, Olson SJ, Ho SB, Peebles RS Jr. Differential immune responses and pulmonary pathophysiology are induced by two different strains of respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(3):977-86. [CrossRef]

- Holtzman MJ, Byers DE, Alexander-Brett J, Wang X. The role of airway epithelial cells and innate immune cells in chronic respiratory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(10):686-98. [CrossRef]

- Knudson CJ, Varga SM. The relationship between respiratory syncytial virus and asthma. Vet Pathol. 2015 Jan;52(1):97-106. [CrossRef]

- Binns E, Tuckerman J, Licciardi PV, Wurzel D. Respiratory syncytial virus, recurrent wheeze and asthma: A narrative review of pathophysiology, prevention and future directions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022 Oct;58(10):1741-1746. [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Salazar C, Hasegawa K, Hartert TV. Progress in understanding whether respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy causes asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152(4):866-869. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha B, You D, Saravia J, Siefker DT, Jaligama S, Lee GI, Sallam AA, Harding JN, Cormier SA. IL-4Rα on dendritic cells in neonates and Th2 immunopathology in respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2017 Jul;102(1):153-161. [CrossRef]

- Drajac C, Laubreton D, Riffault S, Descamps D. Pulmonary Susceptibility of Neonates to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection: A Problem of Innate Immunity? J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:8734504. [CrossRef]

- Saghafian-Hedengren S, Sverremark-Ekström E, Nilsson A. T Cell Subsets During Early Life and Their Implication in the Treatment of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Front Immunol. 2021 Mar 4;12:582539. [CrossRef]

- Erickson EN, Bhakta RT, Tristram D, et al. Pediatric Bronchiolitis. [Updated 2025 Jan 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519506/.

- Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Understanding immunosenescence to improve responses to vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2013 May;14(5):428-36. [CrossRef]

- Shaw AC, Goldstein DR, Montgomery RR. Age-dependent dysregulation of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013 Dec;13(12):875-87. [CrossRef]

- Gray-Miceli D, Gray K, Sorenson MR, Holtzclaw BJ. Immunosenescence and Infectious Disease Risk Among Aging Adults: Management Strategies for FNPs to Identify Those at Greatest Risk. Advances in Family Practice Nursing. 2023;5(1):27–40. [CrossRef]

- Smits HH, Jochems SP. Diverging patterns in innate immunity against respiratory viruses during a lifetime: lessons from the young and the old. Eur Respir Rev. 2024 Jun 12;33(172):230266. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zeng R, Li C, Li N, Wei L, Cui Y. The role of cytokines and chemokines in severe respiratory syncytial virus infection and subsequent asthma. Cytokine. 2011 Jan;53(1):1-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noah TL, Ivins SS, Murphy P, Kazachkova I, Moats-Staats B, Henderson FW. Chemokines and inflammation in the nasal passages of infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Clin Immunol. 2002 Jul;104(1):86-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taveras J, Garcia-Maurino C, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Xu Z, Mertz S, Ye F, Chen P, Cohen SH, Cohen D, Peeples ME, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Type III Interferons, Viral Loads, Age, and Disease Severity in Young Children With Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. J Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 28;227(1):61-70. [CrossRef]

- Zhang G, Zhao B, Liu J. The Development of Animal Models for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection and Enhanced RSV Disease. Viruses. 2024;16(11):1701. [CrossRef]

- Bohmwald K, Gálvez NMS, Canedo-Marroquín G, Pizarro-Ortega MS, Andrade-Parra C, Gómez-Santander F, Kalergis AM. Contribution of Cytokines to Tissue Damage During Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Front Immunol. 2019; 18;10:452. [CrossRef]

- Tekkanat KK, Maassab HF, Cho DS, Lai JJ, John A, Berlin A, Kaplan MH, Lukacs NW. IL-13-induced airway hyperreactivity during respiratory syncytial virus infection is STAT6 dependent. J Immunol. 2001 Mar 1;166(5):3542-8. Erratum in: J Immunol. 2005 ;175(12):8442. [CrossRef]

- Newcomb DC, Boswell MG, Reiss S, Zhou W, Goleniewska K, Toki S, Harintho MT, Lukacs NW, Kolls JK, Peebles RS Jr. IL-17A inhibits airway reactivity induced by respiratory syncytial virus infection during allergic airway inflammation. Thorax. 2013;68(8):717-23. [CrossRef]

- Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, Lundberg F, Schmidt S, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):137-41. [CrossRef]

- Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3 Pt 1):531-7.

- Feltes TF, Cabalka AK, Meissner HC, Piazza FM, Carlin DA, Top FH Jr, Connor EM, Sondheimer HM; Cardiac Synagis Study Group. Palivizumab prophylaxis reduces hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):532-40. [CrossRef]

- Mac S, Sumner A, Duchesne-Belanger S, Stirling R, Tunis M, Sander B. Cost-effectiveness of Palivizumab for Respiratory Syncytial Virus: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2019 May;143(5):e20184064. [CrossRef]

- Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, Baca Cots M, Bosheva M, Madhi SA, Muller WJ, Zar HJ, Brooks D, Grenham A, Wählby Hamrén U, Mankad VS, Ren P, Takas T, Abram ME, Leach A, Griffin MP, Villafana T; MELODY Study Group. Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Healthy Late-Preterm and Term Infants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. [CrossRef]

- Simões EAF, Madhi SA, Muller WJ, Atanasova V, Bosheva M, Cabañas F, Baca Cots M, Domachowske JB, Garcia-Garcia ML, Grantina I, Nguyen KA, Zar HJ, Berglind A, Cummings C, Griffin MP, Takas T, Yuan Y, Wählby Hamrén U, Leach A, Villafana T. Efficacy of nirsevimab against respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in preterm and term infants, and pharmacokinetic extrapolation to infants with congenital heart disease and chronic lung disease: a pooled analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023 Mar;7(3):180-189. [CrossRef]

- Drysdale SB, Cathie K, Flamein F, Knuf M, Collins AM, Hill HC, Kaiser F, Cohen R, Pinquier D, Felter CT, Vassilouthis NC, Jin J, Bangert M, Mari K, Nteene R, Wague S, Roberts M, Tissières P, Royal S, Faust SN; HARMONIE Study Group. Nirsevimab for Prevention of Hospitalizations Due to RSV in Infants. N Engl J Med. 2023 Dec 28;389(26):2425-2435. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Early estimates of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness in preventing RSV-associated hospitalizations among infants—United States, October 2022–February 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(9), 225–229.

- Gadomski AM, Scribani MB. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(6):CD001266. [CrossRef]

- Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, Sullivan AF, Forgey T, Clark S, Espinola JA, Camargo CA Jr; MARC-30 Investigators. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Aug;166(8):700-6. [CrossRef]

- Rose-John S. Interleukin-6 Family Cytokines. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018;10(2):a028415. [CrossRef]

- McNamara PS, Ritson P, Selby A, Hart CA, Smyth RL. Bronchoalveolar lavage cellularity in infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(10):922-6. [CrossRef]

- Banuelos J, Lu NZ. A gradient of glucocorticoid sensitivity among helper T cell cytokines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;31:27-35. [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan SA, McInnes IB. JAK Inhibitors in Rheumatology: Implications for Paediatric Syndromes? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(12):83. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues TS, Zamboni DS. Inflammasome Activation by RNA Respiratory Viruses: Mechanisms, Viral Manipulation, and Therapeutic Insights. Immunol Rev. 2025 Mar;330(1):e70003. [CrossRef]

- Zeng J, Xie X, Feng XL, Xu L, Han JB, Yu D, Zou QC, Liu Q, Li X, Ma G, Li MH, Yao YG. Specific inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome suppresses immune overactivation and alleviates COVID-19 like pathology in mice. EBioMedicine. 20225:103803. [CrossRef]

- Ventre K, Randolph AG. Ribavirin for respiratory syncytial virus infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD000181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000181.pub3. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD000181. [CrossRef]

- DeVincenzo JP, Whitley RJ, Mackman RL, Scaglioni-Weinlich C, Harrison L, Farrell E, McBride S, Lambkin-Williams R, Jordan R, Xin Y, Ramanathan S, O'Riordan T, Lewis SA, Li X, Toback SL, Lin SL, Chien JW. Oral GS-5806 activity in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 21;371(8):711-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty FM, Chemaly RF, Mullane KM, Lee DG, Hirsch HH, Small CB, Bergeron A, Shoham S, Ljungman P, Waghmare A, Blanchard E, Kim YJ, McKevitt M, Porter DP, Jordan R, Guo Y, German P, Boeckh M, Watkins TR, Chien JW, Dadwal SS. A Phase 2b, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Study Evaluating Antiviral Effects, Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Presatovir in Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients with Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection of the Lower Respiratory Tract. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71(11):2787-2795. [CrossRef]

- DeVincenzo JP, McClure MW, Symons JA, Fathi H, Westland C, Chanda S, Lambkin-Williams R, Smith P, Zhang Q, Beigelman L, Blatt LM, Fry J. Activity of Oral ALS-008176 in a Respiratory Syncytial Virus Challenge Study. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2048-58. [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Shang Y, Yin Y, Zou Y, Xu Y, Zhong L, Zhang H, Zhang H, Zhao D, Shen T, Huang D, Chen Q, Yang Q, Yang Y, Dong X, Li L, Chen Z, Liu E, Deng L, Jiang W, Cheng H, Nong G, Wang X, Chen Y, Ding R, Zhou W, Zheng Y, Shen Z, Lu X, Hao C, Zhu X, Jia T, Wu Y, Zou G, Rito K, Wu JZ, Liu H, Ni X; AIRFLO Study Group. Ziresovir in Hospitalized Infants with Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(12):1096-1107. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Zhao W, Zhang X, Zhang L, Guo R, Huang H, Lin L, Liu F, Chen H, Shen F, Wu J, Huang X, Zhu X, Li F, Zou G, Chien J, Humphries M, Lu Q, Wu JZ, Zhao S, Liu H, Ni X; AIRFLO Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ziresovir in hospitalised infants aged 6 months or younger with respiratory syncytial virus infection in China: findings from a phase 3 randomised trial with 24-month follow-up. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2025 May;9(5):325-336. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Xue B, Liu F, Lu Y, Tang J, Yan M, Wu Q, Chen R, Zhou A, Liu L, Liu J, Qu C, Wu Q, Fu M, Zhong J, Dong J, Chen S, Wang F, Zhou Y, Zheng J, Peng W, Shang J, Chen X. Farnesyltransferase inhibitor lonafarnib suppresses respiratory syncytial virus infection by blocking conformational change of fusion glycoprotein. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024;9(1):144. [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon KM, Jordan R, Mawhorter ME, Noton SL, Powers JG, Fearns R, Cihlar T, Perron M. The Interferon Type I/III Response to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Airway Epithelial Cells Can Be Attenuated or Amplified by Antiviral Treatment. J Virol. 2015;90(4):1705-17. [CrossRef]

- Funchal GA, Jaeger N, Czepielewski RS, Machado MS, Muraro SP, Stein RT, Bonorino CB, Porto BN. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein promotes TLR-4-dependent neutrophil extracellular trap formation by human neutrophils. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 9;10(4):e0124082. [CrossRef]

- de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Huijskens EG, Wyllie AL, Biesbroek G, van den Bergh MR, Veenhoven RH, Wang X, Trzciński K, Bonten MJ, Rossen JW, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Dysbiosis of upper respiratory tract microbiota in elderly pneumonia patients. ISME J. 2016 Jan;10(1):97-108. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa K, Camargo CA Jr, Mansbach JM. Role of nasal microbiota and host response in infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection: Causal questions about respiratory outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(3):898-900. [CrossRef]

- Johansson C. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: an innate perspective. F1000Res. 2016;5:2898. [CrossRef]

- van Erp EA, Luytjes W, Ferwerda G, van Kasteren PB. Fc-Mediated Antibody Effector Functions During Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and Disease. Front Immunol. 2019 Mar 22;10:548. [CrossRef]

- Wallis RS, O'Garra A, Sher A, Wack A. Host-directed immunotherapy of viral and bacterial infections: past, present and future. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023 Feb;23(2):121-133. [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer ES, Marsland BJ. Impact of Early-Life Exposures on Immune Maturation and Susceptibility to Disease. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(11):684-696. [CrossRef]

- Norlander AE, Peebles RS Jr. Innate Type 2 Responses to Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Viruses. 2020;12(5):521. [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Hamilton RG, Weng NP, Xue QL, Bream JH, Li H, Tian J, Yeh SH, Resnick B, Xu X, Walston J, Fried LP, Leng SX. Frailty is associated with impairment of vaccine-induced antibody response and increase in post-vaccination influenza infection in community-dwelling older adults. Vaccine. 2011 Jul 12;29(31):5015-21. [CrossRef]

- Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly adults. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(7):577-87. [CrossRef]

- Resch B. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in High-risk Infants - an Update on Palivizumab Prophylaxis. Open Microbiol J. 2014;8:71-7. [CrossRef]

- Boyce TG, Mellen BG, Mitchel EF Jr, Wright PF, Griffin MR. Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in medicaid. J Pediatr. 2000;137(6):865-70. [CrossRef]

- Vekemans J, Moorthy V, Giersing B, Friede M, Hombach J, Arora N, Modjarrad K, Smith PG, Karron R, Graham B, Kaslow DC. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccine research and development: World Health Organization technological roadmap and preferred product characteristics. Vaccine. 2019 Nov 28;37(50):7394-7395. [CrossRef]

- Anderson LJ, Dormitzer PR, Nokes DJ, Rappuoli R, Roca A, Graham BS. Strategic priorities for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine development. Vaccine. 2013;31 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):B209-15. [CrossRef]