Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

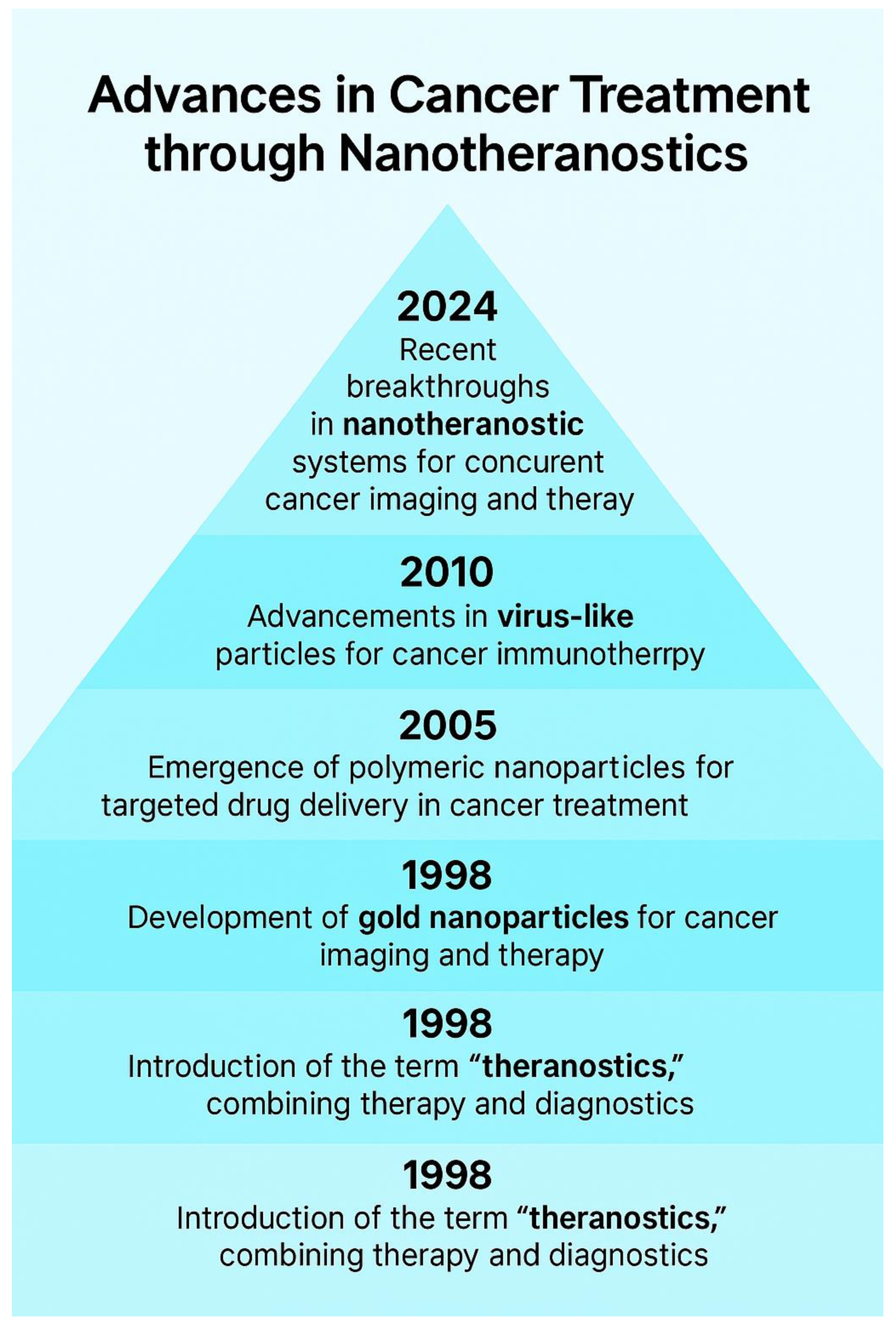

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Cancer Treatment Challenges

1.2. Nanotheranostics as a Promising Approach

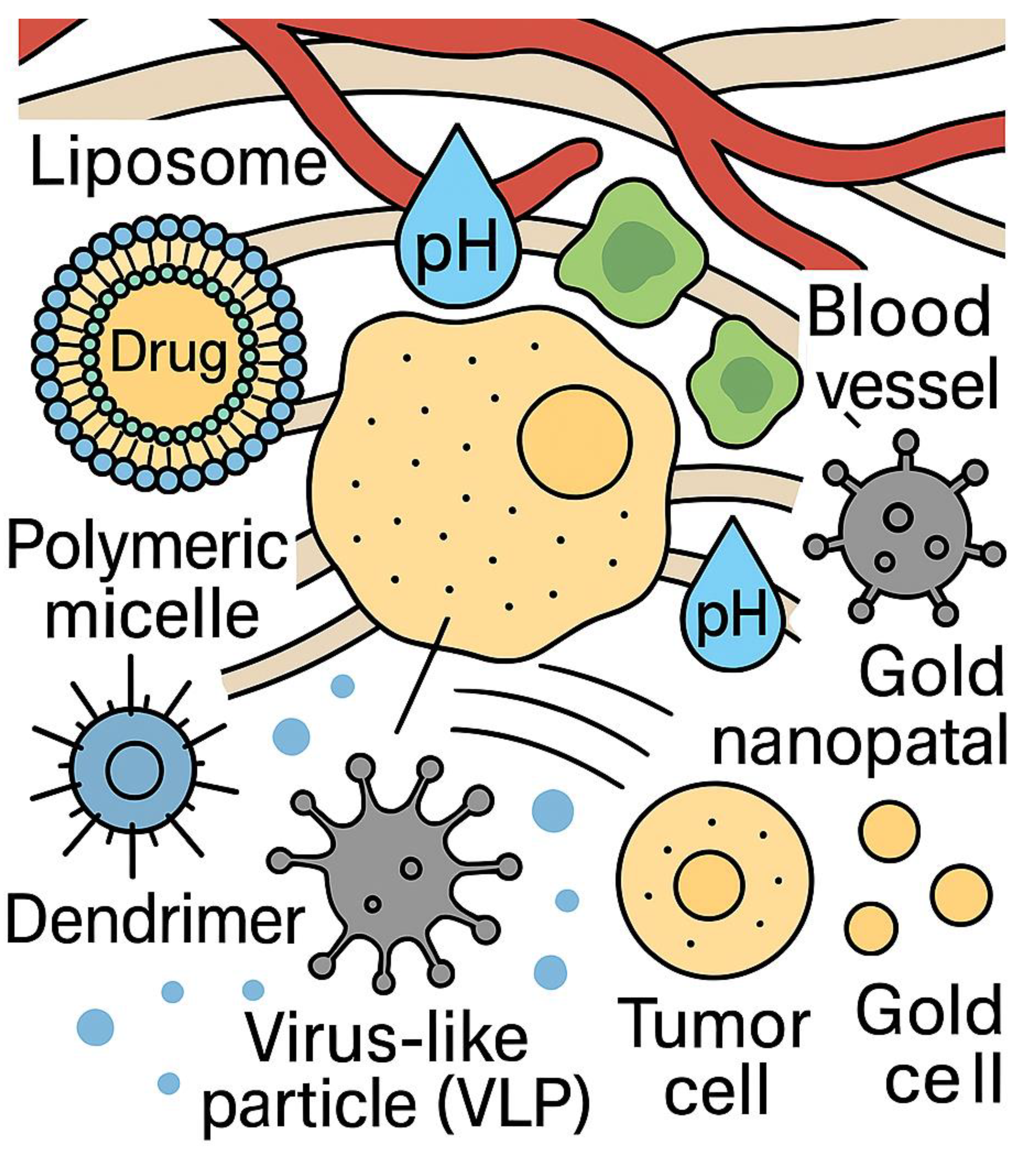

2.1. Significance of Nanotheranostics

2.2. Role of Nanoparticles in Enhancing Treatment Efficacy

3. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTC) and Cancer Biomarkers (CB)

3.1. Importance of CTCs in Cancer Diagnosis and Monitoring

3.2. Utilization of Cancer Biomarkers for Personalized Treatment Strategies

4. Integration of Cancer Treatment with Conventional Therapies

4.1. Enhancement of Radiotherapy Through Nanotechnology

4.2. Synergistic Effects of Nanoparticles with Chemotherapeutic Agents

4.3. Role of Nanoparticles in Improving Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Outcomes

4.3.1. Improved Solubility and Bioavailability

4.3.2. Targeted Delivery

4.3.3. Enhanced Tumor Penetration

4.3.4. Overcoming Hypoxia

4.3.5. Controlled Release and Activation

4.3.6. Combination Therapies

4.4. Application of Chromophore-Assisted Light Inactivation (CALI) in Targeted Cancer Cell Destruction

4.4.1. Advantages of CALI in Cancer Treatment

4.4.2. Challenges and Future Directions

5. Emerging Therapies in Cancer Treatment

5.1. Immunotherapy

5.1.1. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

5.1.2. CAR-T Cell Therapy

5.2. Targeted Therapy

5.2.1. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs)

5.2.2. Monoclonal Antibodies

5.2.3. Small Molecule Inhibitors

5.3. Gene Therapy

5.3.1. CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

5.3.2. Tumor-Suppressor Gene Restoration

5.3.3. Challenges and Future Directions

5.4. Epigenetic Therapy

5.4.1. Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors

5.4.2. DNA Methyltransferase (DNMT) Inhibitors

5.4.3. Challenges and Future Directions

5.5. Oncolytic Virus Therapy

5.5.1. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC)

5.5.2. Mechanisms of Action

5.5.3. Challenges and Future Directions

5.7. Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

5.7.1. Mechanism of Action

5.7.2. Examples of Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

5.7.4. Challenges and Future Directions

5.8. Stem Cell Therapy

5.8.1. Applications in Cancer Treatment

5.8.2. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Challenges and Future Directions

6.1. Current Limitations in Nanotheranostics Application

6.2. Future Research Opportunities and Potential Breakthroughs

6.2.1. Emerging Research Areas

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doroshaw, D.B.; Bhalla, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Sholl, L.M.; Kerr, K.M.; Gnjatic, S.; Wistuba, I.I.; Rimm, D.L.; Tsao, M.S.; Hirsch, F.R. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmeri, M.; Mehnert, J.; Silk, A.W.; Jabbour, S.K.; Ganesan, S.; Popli, P.; Riedlinger, G.; Stephenson, R.; de Meritens, A.B.; Leiser, A.; Mayer, T. Real-world application of tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-high) and microsatellite instability (MSI) confirms their utility as immunotherapy biomarkers. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randrian, V.; Evrard, C.; Tougeron, D. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancers: carcinogenesis, neo-antigens, immuno-resistance, and emerging therapies. Cancers 2021, 13, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, R.I.; Chen, K.; Usmani, A.; Chua, C.; Harris, P.K.; Binkley, M.S.; Azad, T.D.; Dudley, J.C.; Chaudhuri, A.A. Detection of solid tumor molecular residual disease (MRD) using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 23, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Xiang, Y. Circulating tumor DNA: a noninvasive biomarker for tracking ovarian cancer. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Zhu, W.; Guan, Y.; Yang, L.; Xia, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Yi, Z.; Qian, H.; Yi, X. ctDNA dynamics: a novel indicator to track resistance in metastatic breast cancer treated with anti-HER2 therapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, T.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, R.; Wu, X.; Yan, J.; Shao, Y.W.; Shao, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, X. Monitoring treatment efficacy and resistance in breast cancer patients via circulating tumor DNA genomic profiling. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2020, 8, e1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddowes, E.; Sammut, S.J.; Gao, M.; Caldas, C. Predicting treatment resistance and relapse through circulating DNA. Breast 2017, 34, S31–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoda, M. Potential alternatives to conventional cancer therapeutic approaches: the way forward. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Karapetyan, L.; Kirkwood, J.M. Immunotherapy in melanoma: recent advances and future directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; Crown, J. A personalized approach to cancer treatment: How biomarkers can help. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 1770–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, J.S.; Teng, M.W.L.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Allison, J.P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 2015, 348, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Xu, L.; Yi, M.; Yu, S.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Novel immune checkpoint targets: Moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Niu, M.; Xu, L.; Luo, S.; Wu, K. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xi, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhang, R. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe, R.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1440–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, T.M.; Han, J.Y.; et al. Phase III study of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in EGFR- or ALK-rearranged NSCLC. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 42, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Pluzanski, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science 2015, 348, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghaei, H.; Gettinger, S.; Vokes, E.E.; et al. Five-year outcomes from the randomized, phase III trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Larkin, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Powles, T.; Duran, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammers, H.J.; Plimack, E.R.; Infante, J.R.; et al. Nivolumab for previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 812–822. [Google Scholar]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Long-term survival results for nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in melanoma: 5-year follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litchfield, K.; Reading, J.L.; Puttick, C.; et al. Meta-analysis of tumor heterogeneity in checkpoint blockade-treated cancers. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 693. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, L.Q.M.; Haddad, R.; Gupta, S.; et al. Antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Xue, M.; et al. The role of PD-L1 in tumor-induced immune suppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3248–3260. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiehchen, D.; Espinoza, M.; Romanowski, M.; et al. The expanding role of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in lung cancer treatment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 520–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival benefit from checkpoint blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Borcoman, E.; Nandikolla, A.; Long, G.; Goel, S.; Janku, F.; Lazar, A.; Le Tourneau, C. Tumor mutational burden as a biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Cristescu, R.; Aurora-Garg, D.; Albright, A.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Furness, A.J.S.; Rosenthal, R.; et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016, 351, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; et al. The mutational landscape of lung cancer and its impact on sensitivity to PD-1 blockade. Science 2015, 348, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for global precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, A.M.; Kato, S.; Bazhenova, L.; et al. Tumor mutation burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Frampton, G.M.; Rioth, M.J.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies markers of response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and immune evasion in cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.L.; Pike, L.R.G.; Royce, T.J.; Mahal, B.A.; Loeffler, J.S. Genomic determinants of radiation therapy response. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Palucka, K.; Coussens, L.M. The immune system and cancer: Partners in crime? Science 2016, 354, 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disis, M.L.; Slota, M.; Stanton, S.E. T cell-based cancer immunity: The science behind clinical discovery. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1105. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.K.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Chamoto, K.; Zheng, S.; et al. Impact of tumor mutational burden on cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, P.S.; Karanikas, V.; Evers, S. The evolving paradigm of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Kallberg, E.; Feng, X.; et al. T-cell responses and immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Wargo, J.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Reuben, A.; Sharma, P. Monitoring immune responses in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerratana, L.; Basile, D.; Buono, G.; et al. Tumor microenvironment and immune evasion in cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 99, 102258. [Google Scholar]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat cancer by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Understanding immune cell dynamics in cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Fearon, D.T. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, Y.; Wu, H. The tumor microenvironment in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The impact of immune cell reprogramming in cancer therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Ruffell, B. Immunoediting and the role of the immune microenvironment in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Benci, J.L.; Johnson, L.R.; Choa, R.; et al. Tumor adaptation to immunotherapy. Nature 2022, 603, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Garris, C.S.; Luke, J.J.; Denduluri, N.; et al. The evolving role of immunotherapy in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 490–509. [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie, M.F.; Pollack, J.L.; Tanqueco, R.L.; et al. Tumor immune evasion mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, G.L.; Gladney, W.L. Immune escape mechanisms in cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Shuen, T.Z.; Toh, T.B.; et al. Tumor immunology and immune resistance mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2018, 422, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; et al. The role of tumor microenvironment in immune suppression. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; et al. The tumor microenvironment and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancers 2023, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor-intrinsic oncogenic pathways influencing immune recognition and response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, S.J.; Cremasco, V.; Astarita, J.L. Immunological pathways driving tumor progression and response to therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Immune evasion in tumors: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: A blueprint for designing effective immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 704–721. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulk, J.; Verdegaal, E.M.E.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Future perspectives. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 635–650. [Google Scholar]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with microsatellite instability–high advanced colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2616–2628. [Google Scholar]

- Kloor, M.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M. The immune biology of microsatellite-unstable cancers. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Frankel, W.L.; Martin, E.; et al. Screening for the Lynch syndrome using microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response to PD-1 blockade in metastatic colorectal cancer. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.M.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; et al. IL10-induced upregulation of TIM-3 in human T cells inhibits anti-tumor immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 990–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, K.G.; Tegeler, C.; Barlogie, B.; et al. Therapy resistance in immunotherapy-treated cancers. Blood 2018, 132, 967–978. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Tumor immune escape and resistance to checkpoint inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 442–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer and immune suppression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S.; Youn, J.I.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Tumor-induced immune suppression and therapeutic strategies. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.M.; Vétizou, M.; Daillère, R.; et al. Resistance to immunotherapy and novel strategies for overcoming it. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumors: A major classification scheme for response to immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; van der Kaaij, M.; van den Berg, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint blockade combined with radiation therapy in cancer treatment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 432. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, M.; Knebel, F.H.; Menshikh, A.; et al. The role of IFN-γ in overcoming tumor-induced immune suppression. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lauck, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Ruddy, M.; et al. Modulating immune cell exhaustion to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 695–712. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.J.; Comps-Agrar, L.; Hackney, J.; et al. Mechanisms of resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.C.; Bortolanza, P.; Martinez, E.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming and immune escape in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Rickert, K.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; et al. Immune escape mechanisms of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 234–247. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; et al. Immunotherapy resistance and strategies to overcome it. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 107, 102389. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, L.; Hotson, A.; Funk, J.O.; et al. TIGIT inhibition and immune responses in advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Gettinger, S.; Horn, L.; Gandhi, L.; et al. Atezolizumab in patients with previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2332–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Taube, J.M.; Anders, R.A.; Pardoll, D.M. Mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 413–426. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.J.; Gartner, J.J.; Horovitz-Fried, M.; et al. Isolation of neoantigen-specific T cell receptors from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Science 2015, 348, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Scheper, W.; Baumeister, S.H.; et al. Clonal selection and T cell response in immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 773–784. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Soria, J.C.; Kowanetz, M.; et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab in cancer patients. Nature 2014, 515, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Immunity 2017, 46, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, L.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hartmann, T.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Hellmann, M.D. Acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rabe, K.F. Precision medicine in lung cancer: Biomarkers and targeted therapies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 653–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; et al. The molecular landscape of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; et al. Clinical application of tumor mutational burden in immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Duran, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Pluzanski, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Pluzanski, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Long-term survival results for nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in melanoma: 5-year follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.Q.M.; Haddad, R.; Gupta, S.; et al. Antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Xue, M.; et al. The role of PD-L1 in tumor-induced immune suppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3248–3260. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiehchen, D.; Espinoza, M.; Romanowksi, M.; et al. The expanding role of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in lung cancer treatment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 520–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival benefit from checkpoint blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Borcoman, E.; Nandikolla, A.; Long, G.; et al. Tumor mutational burden as a biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Cristescu, R.; Aurora-Garg, D.; Albright, A.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Furness, A.J.S.; Rosenthal, R.; et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016, 351, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; et al. The mutational landscape of lung cancer and its impact on sensitivity to PD-1 blockade. Science 2015, 348, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for global precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, A.M.; Kato, S.; Bazhenova, L.; et al. Tumor mutation burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Frampton, G.M.; Rioth, M.J.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies markers of response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and immune evasion in cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, W.L.; Pike, L.R.G.; Royce, T.J.; et al. Genomic determinants of radiation therapy response. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Palucka, K.; Coussens, L.M. The immune system and cancer: Partners in crime? Science 2016, 354, 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disis, M.L.; Slota, M.; Stanton, S.E. T cell-based cancer immunity: The science behind clinical discovery. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1105. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.K.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 expression as a predictor of outcomes in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Chamoto, K.; Zheng, S.; et al. Impact of tumor mutational burden on cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, P.S.; Karanikas, V.; Evers, S. The evolving paradigm of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Kallberg, E.; Feng, X.; et al. T-cell responses and immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Wargo, J.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Reuben, A.; Sharma, P. Monitoring immune responses in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerratana, L.; Basile, D.; Buono, G.; et al. Tumor microenvironment and immune evasion in cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 99, 102258. [Google Scholar]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat cancer by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Understanding immune cell dynamics in cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Fearon, D.T. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, Y.; Wu, H. The tumor microenvironment in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The impact of immune cell reprogramming in cancer therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Ruffell, B. Immunoediting and the role of the immune microenvironment in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Benci, J.L.; Johnson, L.R.; Choa, R.; et al. Tumor adaptation to immunotherapy. Nature 2022, 603, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Garris, C.S.; Luke, J.J.; Denduluri, N.; et al. The evolving role of immunotherapy in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 490–509. [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie, M.F.; Pollack, J.L.; Tanqueco, R.L.; et al. Tumor immune evasion mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, G.L.; Gladney, W.L. Immune escape mechanisms in cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shuen, T.Z.; Toh, T.B.; et al. Tumor immunology and immune resistance mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2018, 422, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; et al. The role of tumor microenvironment in immune suppression. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; et al. The tumor microenvironment and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancers 2023, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor-intrinsic oncogenic pathways influencing immune recognition and response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, S.J.; Cremasco, V.; Astarita, J.L. Immunological pathways driving tumor progression and response to therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Immune evasion in tumors: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: A blueprint for designing effective immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 704–721. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulk, J.; Verdegaal, E.M.E.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Future perspectives. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 635–650. [Google Scholar]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with microsatellite instability–high advanced colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2616–2628. [Google Scholar]

- Kloor, M.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M. The immune biology of microsatellite-unstable cancers. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Frankel, W.L.; Martin, E.; et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome using microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response to PD-1 blockade in metastatic colorectal cancer. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.M.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; et al. IL-10-induced upregulation of TIM-3 in human T cells inhibits anti-tumor immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 990–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, K.G.; Tegeler, C.; Barlogie, B.; et al. Therapy resistance in immunotherapy-treated cancers. Blood 2018, 132, 967–978. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Tumor immune escape and resistance to checkpoint inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 442–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer and immune suppression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraj, S.; Youn, J.I.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Tumor-induced immune suppression and therapeutic strategies. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.M.; Vétizou, M.; Daillère, R.; et al. Resistance to immunotherapy and novel strategies for overcoming it. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumors: A major classification scheme for response to immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; van der Kaaij, M.; van den Berg, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint blockade combined with radiation therapy in cancer treatment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 432. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, M.; Knebel, F.H.; Menshikh, A.; et al. The role of IFN-γ in overcoming tumor-induced immune suppression. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lauck, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Ruddy, M.; et al. Modulating immune cell exhaustion to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 695–712. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.J.; Comps-Agrar, L.; Hackney, J.; et al. Mechanisms of resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.C.; Bortolanza, P.; Martinez, E.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming and immune escape in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Rickert, K.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; et al. Immune escape mechanisms of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 234–247. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; et al. Immunotherapy resistance and strategies to overcome it. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 107, 102389. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, L.; Hotson, A.; Funk, J.O.; et al. Anti-TIGIT therapy in advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Gettinger, S.; Horn, L.; Gandhi, L.; et al. Atezolizumab in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2332–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Taube, J.M.; Anders, R.A.; Pardoll, D.M. Mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.J.; Gartner, J.J.; Horovitz-Fried, M.; et al. Identifying neoantigen-specific T cell receptors in tumor infiltration. Science 2015, 348, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Scheper, W.; Baumeister, S.H.; et al. Clonal selection and T cell response in immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 773–784. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Soria, J.C.; Kowanetz, M.; et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab in cancer patients. Nature 2014, 515, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Immunity 2017, 46, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, L.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hartmann, T.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Hellmann, M.D. Acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rabe, K.F. Precision medicine in lung cancer: Biomarkers and targeted therapies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; et al. The molecular landscape of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; et al. Clinical application of tumor mutational burden in immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Pluzanski, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; et al. Long-term survival results for nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in melanoma: 5-year follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.Q.M.; Haddad, R.; Gupta, S.; et al. Antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Xue, M.; et al. The role of PD-L1 in tumor-induced immune suppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3248–3260. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiehchen, D.; Espinoza, M.; Romanowksi, M.; et al. The expanding role of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in lung cancer treatment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 520–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival benefit from checkpoint blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Borcoman, E.; Nandikolla, A.; Long, G.; et al. Tumor mutational burden as a biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Cristescu, R.; Aurora-Garg, D.; Albright, A.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Furness, A.J.S.; Rosenthal, R.; et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016, 351, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; et al. The mutational landscape of lung cancer and its impact on sensitivity to PD-1 blockade. Science 2015, 348, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, T.A.; Yarchoan, M.; Jaffee, E.; et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: Utility for global precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, A.M.; Kato, S.; Bazhenova, L.; et al. Tumor mutation burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2598–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Frampton, G.M.; Rioth, M.J.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identifies markers of response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and immune evasion in cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.L.; Pike, L.R.G.; Royce, T.J.; et al. Genomic determinants of radiation therapy response. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Palucka, K.; Coussens, L.M. The immune system and cancer: Partners in crime? Science 2016, 354, 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disis, M.L.; Slota, M.; Stanton, S.E. T cell-based cancer immunity: The science behind clinical discovery. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1105. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.K.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 expression as a predictor of outcomes in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Chamoto, K.; Zheng, S.; et al. Impact of tumor mutational burden on cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 731–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, P.S.; Karanikas, V.; Evers, S. The evolving paradigm of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Kallberg, E.; Feng, X.; et al. T-cell responses and immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Wargo, J.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Reuben, A.; Sharma, P. Monitoring immune responses in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerratana, L.; Basile, D.; Buono, G.; et al. Tumor microenvironment and immune evasion in cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 99, 102258. [Google Scholar]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat cancer by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Understanding immune cell dynamics in cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Fearon, D.T. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 512–522. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, Y.; Wu, H. The tumor microenvironment in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.C.; Duffy, C.R.; Allison, J.P. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The impact of immune cell reprogramming in cancer therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo, D.G.; Ruffell, B. Immunoediting and the role of the immune microenvironment in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Benci, J.L.; Johnson, L.R.; Choa, R.; et al. Tumor adaptation to immunotherapy. Nature 2022, 603, 160–167. [Google Scholar]

- Garris, C.S.; Luke, J.J.; Denduluri, N.; et al. The evolving role of immunotherapy in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 490–509. [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie, M.F.; Pollack, J.L.; Tanqueco, R.L.; et al. Tumor immune evasion mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, G.L.; Gladney, W.L. Immune escape mechanisms in cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shuen, T.Z.; Toh, T.B.; et al. Tumor immunology and immune resistance mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2018, 422, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; et al. The role of tumor microenvironment in immune suppression. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; et al. The tumor microenvironment and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancers 2023, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor-intrinsic oncogenic pathways influencing immune recognition and response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, S.J.; Cremasco, V.; Astarita, J.L. Immunological pathways driving tumor progression and response to therapy. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; et al. Immune evasion in tumors: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: A blueprint for designing effective immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 704–721. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulk, J.; Verdegaal, E.M.E.; de Miranda, N.F.C.C. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Future perspectives. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 635–650. [Google Scholar]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with microsatellite instability–high advanced colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2616–2628. [Google Scholar]

- Kloor, M.; von Knebel Doeberitz, M. The immune biology of microsatellite-unstable cancers. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Frankel, W.L.; Martin, E.; et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome using microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Durham, J.N.; Smith, K.N.; et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response to PD-1 blockade in metastatic colorectal cancer. Science 2017, 357, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauvin, J.M.; Pagliano, O.; Fourcade, J.; et al. IL-10-induced upregulation of TIM-3 in human T cells inhibits anti-tumor immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 990–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, K.G.; Tegeler, C.; Barlogie, B.; et al. Therapy resistance in immunotherapy-treated cancers. Blood 2018, 132, 967–978. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Tumor immune escape and resistance to checkpoint inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 442–455. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer and immune suppression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S.; Youn, J.I.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Tumor-induced immune suppression and therapeutic strategies. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.M.; Vétizou, M.; Daillère, R.; et al. Resistance to immunotherapy and novel strategies for overcoming it. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Spranger, S.; Bao, R.; Gajewski, T.F. T cell-inflamed versus non-T cell-inflamed tumors: A major classification scheme for response to immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, M.E.; van der Kaaij, M.; van den Berg, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint blockade combined with radiation therapy in cancer treatment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 432. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, M.; Knebel, F.H.; Menshikh, A.; et al. The role of IFN-γ in overcoming tumor-induced immune suppression. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lauck, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Ruddy, M.; et al. Modulating immune cell exhaustion to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 695–712. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.J.; Comps-Agrar, L.; Hackney, J.; et al. Mechanisms of resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.C.; Bortolanza, P.; Martinez, E.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming and immune escape in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Rickert, K.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; et al. Immune escape mechanisms of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 234–247. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; et al. Immunotherapy resistance and strategies to overcome it. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 107, 102389. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, L.; Hotson, A.; Funk, J.O.; et al. Anti-TIGIT therapy in advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Gettinger, S.; Horn, L.; Gandhi, L.; et al. Atezolizumab in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2332–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Nathanson, T.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, S.L.; Taube, J.M.; Anders, R.A.; Pardoll, D.M. Mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, C.J.; Gartner, J.J.; Horovitz-Fried, M.; et al. Identifying neoantigen-specific T cell receptors in tumor infiltration. Science 2015, 348, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Scheper, W.; Baumeister, S.H.; et al. Clonal selection and T cell response in immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 773–784. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.S.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Soria, J.C.; Kowanetz, M.; et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab in cancer patients. Nature 2014, 515, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Immunity 2017, 46, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Gajewski, T.F. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, L.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hartmann, T.; et al. Tumor mutational burden and response to immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Hellmann, M.D. Acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rabe, K.F. Precision medicine in lung cancer: Biomarkers and targeted therapies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; et al. The molecular landscape of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; et al. Clinical application of tumor mutational burden in immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, P.C.; Harview, C.L.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014, 515, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, S.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Dranoff, G.; Sharpe, A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Durán, I.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellmann, M.D.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Pluzanski, A.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).