The landscape of higher education continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements, changing student demographics, and shifting workforce demands. Competency-based education (CBE) delivered through online platforms has emerged as a potentially transformative approach to addressing three critical challenges: student access, affordability, and labor market preparation.

These three elements form what is proposed as the "accessibility triad" in higher education—a framework that merits critical examination rather than unquestioned acceptance. This triad represents one perspective on educational value among many competing frameworks, each prioritizing different aspects of the higher education enterprise. When properly balanced, this triad offers a promising path forward for certain institutional models and student populations. When imbalanced, it can lead to disappointing outcomes for stakeholders involved.

The timeliness of this examination cannot be overstated. As higher education grapples with declining enrollments, persistent affordability challenges, and increasing skepticism about the return on educational investment, competency-based online models have gained renewed attention from institutional leaders, policymakers, and students. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated existing trends toward online learning modalities while simultaneously exposing significant disparities in digital access and self-directed learning readiness. Against this backdrop, critically analyzing the promises and limitations of CBE approaches provides essential guidance for institutional decision-making, policy development, and student choice. By moving beyond promotional rhetoric to examine empirical outcomes across diverse contexts and populations, this research contributes to more informed implementation of educational innovations that genuinely serve student needs rather than merely repackaging traditional approaches in technological wrappers.

This research brief examines how competency-based online education models respond to these challenges, the theoretical foundations underpinning their approaches, and practical applications drawn from institutional case studies—both successful implementations and those that have faced significant challenges. The aim is to provide a nuanced analysis that acknowledges both the transformative potential and the very real limitations of these educational models, while recognizing that these three dimensions represent particular values that may sometimes exist in tension with other important educational purposes.

Conceptualizing the Accessibility Triad: A Framework for Analysis

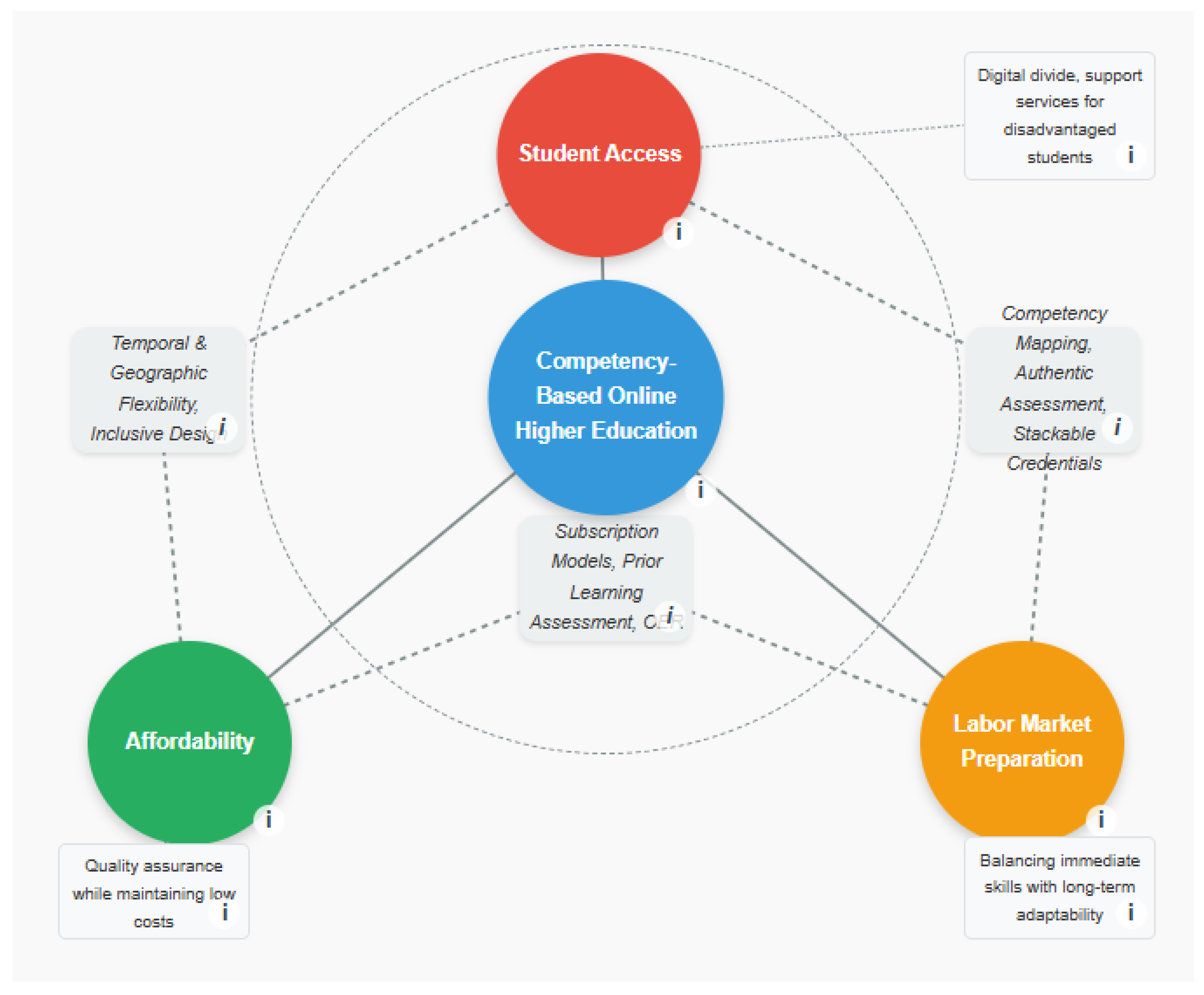

The complex interplay of access, affordability, and labor market preparation in competency-based online education can be visualized through what this paper terms the "accessibility triad" (

Figure 1). This conceptual framework illustrates how these three dimensions interact to shape educational outcomes for diverse student populations. Each dimension represents a distinct but interconnected challenge that CBE models attempt to address:

Access encompasses the temporal, geographic, and design considerations that determine who can participate in higher education. This dimension focuses on how educational models accommodate diverse life circumstances, learning needs, and technological capacities.

Affordability addresses the financial structures that enable or constrain educational participation, including direct costs, opportunity costs, and long-term economic returns on educational investment.

Labor Market Preparation concerns the alignment between educational outcomes and workforce needs, including competency definition, assessment design, credential recognition, and career progression pathways.

The model illustrates that optimal educational value emerges when these three dimensions are balanced and mutually reinforcing. When one dimension is prioritized at the expense of others, educational quality and outcomes suffer. For example, maximizing affordability without adequate attention to support services may reduce costs but undermine access for students needing additional assistance. Similarly, strong labor market alignment without attention to affordability may create high-quality but financially inaccessible programs.

As the subsequent analysis demonstrates, navigating this triad effectively requires thoughtful institutional design, adequate resources, and continuous evaluation. The model also acknowledges that these three dimensions, while critical, represent particular educational values that exist alongside other important purposes of higher education, including intellectual development, civic engagement, and personal growth.

The literature informing this analysis was systematically identified through a comprehensive search strategy encompassing peer-reviewed research, institutional reports, policy documents, and theoretical frameworks published between 2010 and 2023. Selection criteria prioritized empirical studies with robust methodologies, comparative analyses examining multiple institutional contexts, and theoretical works that explicitly addressed the intersection of competency frameworks with issues of access, affordability, and labor market outcomes. The review intentionally balanced literature from proponents of CBE models with critical perspectives, seeking to represent the full spectrum of evidence rather than selectively highlighting favorable outcomes. This methodological approach ensures that the analysis reflects the current state of knowledge while acknowledging the limitations and gaps in existing research.

Before examining the current landscape, it is important to situate competency-based education within its historical context. CBE is not a recent innovation but rather the latest iteration in a long history of educational approaches focused on demonstrated outcomes rather than time-based metrics.

The roots of competency-based approaches can be traced to several educational movements:

Mastery learning approaches developed by Benjamin Bloom in the 1960s emphasized allowing students sufficient time to achieve mastery of clearly defined objectives (Guskey, 2010)

Outcomes-based education movements of the 1980s and 1990s shifted focus from inputs to outputs in educational design (Spady, 1994)

Vocational competency frameworks emerged in workforce training contexts throughout the 20th century, particularly in technical fields (Hodge, 2007)

Behaviorist approaches to education in the mid-20th century emphasized observable, measurable learning outcomes (Mager, 1962)

The current incarnation of CBE in higher education represents an evolution of these approaches, influenced by technological capabilities, changing student demographics, and economic pressures facing both students and institutions. As Grant et al. (2018) note in their historical analysis, "Competency-based education has cycled through periods of popularity and criticism, with each iteration reflecting the dominant social concerns and technological capabilities of its era" (p. 27).

A critical limitation in discussions of CBE is the contested nature of "competency" itself. As Brightwell and Grant (2013) observe, "Despite decades of use in educational contexts, 'competency' remains an elusive concept with definitions varying significantly across disciplines, institutions, and national contexts" (p. 192). This definitional ambiguity creates challenges for implementation, assessment, and cross-institutional recognition.

Competencies can range from narrowly defined technical skills to complex capabilities involving integration of knowledge, skills, and dispositions. The breadth or narrowness of competency definitions significantly impacts program design and the educational experience of students. As Voorhees (2001) notes, narrowly defined competencies risk reducing education to a checklist of discrete skills, while broadly defined competencies present significant assessment challenges.

Before examining specific competency-based education models, it is essential to understand the broader higher education context that has driven interest in alternative educational approaches. Three interrelated challenges define the current landscape: changing student demographics that strain traditional access models, an affordability crisis that threatens educational equity, and persistent misalignment between educational outcomes and labor market demands. These challenges form the foundation of the accessibility triad and highlight why competency-based online education has gained traction as a potential solution. However, as the evidence demonstrates, these challenges manifest in complex ways that resist simple solutions. This section examines each dimension of the triad through empirical research, revealing both the genuine problems that CBE aims to address and the nuanced realities that complicate straightforward narratives about educational innovation.

Today's higher education students differ significantly from those of previous generations. The "traditional" 18-22-year-old residential student now represents less than a third of all undergraduates (Lumina Foundation, 2023). Instead, today's students are increasingly:

Older (average age 26)

Working while studying (over 60% work at least part-time)

Supporting dependents (nearly 25% are parents)

First-generation college students (approximately 33%)

Racially and ethnically diverse

These demographic realities create substantial barriers to accessing traditional campus-based education. Geographic limitations, rigid scheduling, and campus-focused support services often fail to accommodate the complex lives of today's learners (Fishman et al., 2022).

However, it would be an oversimplification to suggest that online CBE models automatically resolve access issues for all students. Demographic data from major CBE providers reveals significant disparities in who accesses these programs. For instance, Ortagus and Yang (2018) found that CBE students tend to be older and employed, but also more likely to come from higher socioeconomic backgrounds than community college students. This suggests that while CBE addresses certain access barriers, it may create or maintain others.

The financial burden of higher education has reached crisis proportions. Between 2000 and 2022, the average cost of tuition and fees at public four-year institutions increased by 178%, far outpacing inflation and wage growth (College Board, 2023). Consequently, outstanding student loan debt has surpassed $1.75 trillion, affecting over 45 million Americans (Federal Reserve, 2023).

This affordability crisis has resulted in:

Declining enrollment rates, particularly among low and middle-income students

Higher dropout rates due to financial pressures

Extended time-to-degree completion as students reduce course loads to manage costs

Significant debt burdens that delay life milestones and economic mobility

While CBE models offer promising approaches to cost reduction, independent research on actual cost savings shows mixed results. Empirical studies by Kelchen (2017) found that while some students realize significant savings through CBE models, others—particularly those who progress more slowly—may actually incur higher costs than in traditional programs. This highlights the importance of examining affordability claims with attention to differential impacts across student populations.

The third challenge involves the persistent skills gap between graduate capabilities and employer needs. Multiple surveys indicate employers find recent graduates lacking in critical workplace competencies. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers (2023), over 65% of employers report that recent graduates lack the specific skills needed for their roles, despite possessing theoretical knowledge.

This misalignment manifests in:

Extended onboarding and training periods for new graduates

Underemployment among recent graduates

Reluctance among employers to hire inexperienced graduates

Growing emphasis on alternative credentials and certifications

However, critiques by scholars such as Hora (2020) raise important questions about uncritically accepting employer-defined skill needs. Hora's research indicates that employer demands often reflect short-term needs rather than long-term capabilities, and that "skills gaps" may sometimes reflect unwillingness to provide appropriate training or compensation rather than actual educational deficiencies.

Rather than presenting theoretical frameworks as separate, parallel approaches, CBE is better understood through an integrated theoretical lens that acknowledges tensions and complementarities between different perspectives.

Competency-based education draws from constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes learning as an active process where students construct knowledge rather than passively receiving it (Jonassen, 2019). This connects with andragogy—the theory of adult learning developed by Malcolm Knowles (1984)—which emphasizes that adult learners:

Are self-directed

Bring existing knowledge and experience

Are goal-oriented and relevancy-focused

Learn best when information is immediately applicable

These theoretical foundations support the design of CBE programs that allow students to progress based on demonstrated mastery rather than seat time, applying existing knowledge while focusing on relevant skill development.

However, as Morcke et al. (2013) observe, tensions exist between constructivist views of knowledge as individually constructed and CBE's standardized competency frameworks. This tension requires acknowledgment in program design—how can standardized competencies accommodate personalized knowledge construction? Some CBE programs address this through varied assessment options and personalized learning pathways, while others emphasize standardization over personalization.

An extension of andragogy, heutagogical approaches emphasize learner autonomy and self-determined learning paths (Blaschke, 2021). This theoretical framework supports the flexible, self-paced nature of many CBE programs, allowing students to:

Determine their own learning paths

Set their own pace based on individual circumstances

Focus on areas requiring development while bypassing mastered content

Engage in metacognitive reflection about their learning process

Yet implementation research by Anderson (2021) reveals significant challenges in fully realizing heutagogical principles in practice. Students with limited prior educational success or from educational backgrounds emphasizing teacher direction often struggle with self-directed approaches. This creates an equity concern—CBE models may advantage students who already possess strong self-regulation skills, potentially widening achievement gaps.

From an economic perspective, CBE models navigate between human capital theory—which views education as directly building productive capacity—and signaling theory, which suggests education primarily signals underlying abilities to employers (Becker, 1993; Spence, 1973).

CBE attempts to bridge these theoretical perspectives by:

Developing specific, measurable competencies directly tied to workplace skills (human capital)

Providing transparent evidence of those competencies for employer evaluation (signaling)

Creating alternative credentials that verify specific capabilities rather than generalized degrees

However, research by Davidson (2019) suggests limitations in this approach. While CBE credentials may effectively signal skills to employers in technically-oriented fields with clearly defined competencies, they often lack the broader signaling value of traditional degrees in fields where "competency" is more ambiguous. This highlights the differential value of CBE approaches across disciplinary contexts.

A significant gap in many CBE discussions is attention to power dynamics in determining which competencies are valued and how they are assessed. Drawing on Foucauldian analysis of power/knowledge in educational assessment (Torrance, 2007), researchers must examine who defines competencies, whose interests are served, and how these definitions privilege certain forms of knowledge over others.

Research by Montenegro and Jankowski (2020) demonstrates how seemingly neutral competency statements often embed cultural assumptions and priorities that can disadvantage students from non-dominant groups. This critical perspective highlights the need for inclusive processes in competency development and validation, involving diverse stakeholders including students from underrepresented populations.

Online CBE programs fundamentally reimagine when and where learning occurs. Western Governors University (WGU), one of the pioneers in this space, enables students to access course materials and assessments 24/7, eliminating the geographic and scheduling barriers that traditionally limit access (Nodine & Johnstone, 2022). This flexibility is particularly important for:

Rural students without proximity to physical campuses

Working adults with variable schedules

Students with caregiving responsibilities

Military personnel and others with frequent relocations

The University of Wisconsin Flexible Option similarly structures its programs to accommodate life circumstances that make traditional programs inaccessible, reporting that over 70% of its students would not be pursuing degrees without this flexibility (University of Wisconsin System, 2022).

However, research by Xu and Xu (2019) reveals important limitations in access outcomes. Their analysis of national data shows that while online education has expanded access for some populations (particularly working adults in urban areas), it has been less successful in reaching rural students with limited broadband access and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This "digital divide" remains a significant barrier, with approximately 15% of American households lacking broadband internet access (Pew Research Center, 2023).

Leading CBE institutions are incorporating universal design principles to enhance accessibility for diverse learners. Southern New Hampshire University's (SNHU) competency-based programs employ multiple modalities for content delivery and assessment, accommodating different learning styles and abilities (Matthews et al., 2023). Such approaches include:

Multiple content formats (text, video, audio, interactive)

Varied assessment approaches beyond traditional testing

Built-in accessibility features (screen reader compatibility, captioning, etc.)

Cultural inclusivity in examples, case studies, and applications

Despite these efforts, independent research by Wood et al. (2021) found persistent accessibility gaps in many online CBE programs, particularly for students with disabilities. Their evaluation of 12 major online CBE platforms revealed that only 3 fully met accessibility standards, with the remainder having significant barriers for users with visual, auditory, or motor impairments. This highlights the gap between accessibility intentions and implementation realities.

While successful models dominate the literature, examining failed initiatives provides valuable insights. Queensborough Community College's attempted CBE program for first-generation students was discontinued after two years due to retention challenges and technical barriers (Rivera & Matthews, 2021). Key lessons included:

Insufficient onboarding and digital literacy support

Inadequate broadband access among target populations

Misalignment between self-directed learning expectations and student preparation

Limited personal support and community-building components

Similarly, Brandman University (now UMass Global) scaled back several CBE initiatives after finding that their initial models worked well for experienced professionals but created significant challenges for first-generation students and those with limited prior higher education experience (Johnson & Rodríguez, 2021).

The theoretical promise of expanded educational access through competency-based education requires empirical validation through examination of actual implementation outcomes. This section moves beyond conceptual frameworks to analyze how CBE models have operationalized access in practice, drawing on evidence from both successful implementations and discontinued initiatives. By examining specific approaches to temporal flexibility, geographic constraints, and inclusive design, a more nuanced understanding emerges of when and for whom CBE effectively expands educational participation. The analysis intentionally highlights both innovative successes and instructive failures, recognizing that advancement in the field requires critical examination of limitations alongside celebration of achievements. While technology-enabled flexibility addresses certain access barriers, the evidence reveals it simultaneously introduces new challenges that require thoughtful institutional responses—particularly for students from historically underserved populations who may experience the "digital divide" most acutely.

Several successful CBE programs have moved away from per-credit pricing to subscription-based models. WGU's flat-rate tuition allows students to complete as many competencies as possible within a six-month term for approximately $3,500−$4,500 (depending on the program). This creates economic incentives for:

Accelerated completion for students with prior knowledge or capacity for intensive study

Predictable costs that facilitate financial planning

Elimination of costs associated with courses covering already-mastered material

Research by Desrochers and Staisloff (2021) indicates that the average WGU graduate saves approximately 16,000−30,000 compared to traditional institutions, with faster completion times further reducing opportunity costs.

However, a more critical analysis by Kelchen (2019) reveals significant variation in actual cost savings. His longitudinal study of 1,500 CBE students found that while the top quartile of students (in terms of completion pace) realized substantial savings, students in the bottom quartile actually paid more than they would have in traditional credit-hour programs due to slower progression through competencies. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between potential and actual affordability benefits across different student populations.

CBE programs typically emphasize rigorous prior learning assessment (PLA), allowing students to receive credit for competencies gained through work experience, military service, or other educational experiences. Capella University's FlexPath program reports that students who utilize PLA complete their degrees on average 9-12 months faster than those who don't, representing significant cost savings (Capella University, 2023).

The Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL) found that students who receive PLA credits are 2.5 times more likely to complete their degrees and save an average of 6,000−6,000-6,000−10,000 in tuition costs (Klein-Collins & Olson, 2022).

Implementation research by Stevens et al. (2020), however, identified significant equity concerns in PLA utilization. Their study of PLA across 28 institutions found that white students and those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds were significantly more likely to both request and receive PLA credits than students of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This suggests that without proactive outreach and support, PLA processes may unintentionally reproduce existing educational inequities.

Innovative CBE providers are disaggregating traditional bundled services, allowing students to pay only for what they need. For example:

Northern Arizona University's Personalized Learning program separates mentoring, assessment, and instructional services, reducing costs for self-directed learners

Brandman University (now UMass Global) utilizes open educational resources to eliminate textbook costs, saving students an average of $1,200 per year

College for America (part of SNHU) leverages employer partnerships to subsidize tuition costs

However, Springer's (2021) cost analysis revealed that many unbundled models shift rather than eliminate costs. While direct institutional costs may decrease, students often face increased "hidden costs" for technology, reliable internet access, and support services previously included in bundled models. Additionally, Svinicki and McKeachie (2020) note that the development costs for high-quality CBE programs often exceed those of traditional courses, creating tension between institutional economics and student affordability.

Looking beyond U.S. examples provides valuable insights into alternative affordability approaches. Australia's competency-based vocational education system employs income-contingent loan repayment models that tie repayment to post-graduation income levels, reducing financial risk for students (Norton & Cherastidtham, 2018). Similarly, European competence frameworks often integrate with public funding models to reduce direct student costs while maintaining quality standards (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, 2020).

These international models suggest possibilities for combining CBE approaches with more robust public funding mechanisms to address affordability without placing the entire financial burden on students—an approach largely absent from U.S. implementations.

The third dimension of the accessibility triad—labor market preparation—represents perhaps the most emphasized but empirically contested aspect of competency-based education. This section examines how CBE programs attempt to bridge the gap between educational outcomes and employer needs through various methodological approaches. While labor market alignment serves as a central justification for competency-based models, research reveals significant complexity in both implementation methods and actual outcomes. The analysis below explores four key aspects of labor market alignment: competency mapping methodologies, authentic assessment approaches, microcredential innovations, and longitudinal career impacts. By juxtaposing institutional practices with critical research findings, this section illuminates both the genuine innovations in workplace preparation and the persistent challenges in defining, measuring, and validating competencies that meaningfully transfer to diverse employment contexts. Particularly significant is the emerging evidence that labor market outcomes may vary substantially across demographic groups and disciplinary contexts, suggesting the need for more nuanced approaches to credential design and validation.

Effective CBE programs begin with systematic competency mapping processes that align educational outcomes with workforce needs. Texas A&M University-Commerce's competency-based Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences program developed its competency framework through extensive consultation with regional employers, resulting in 93% of graduates securing relevant employment within six months of graduation (Klein-Collins et al., 2021).

Similar approaches at Salt Lake Community College involve:

Regular industry advisory boards to validate competencies

Analysis of job postings and skill requirements

Partnerships with industry certification bodies

Feedback loops from employer satisfaction data

Critical research by Hora et al. (2021) raises important methodological questions about these alignment processes. Their analysis of competency development methods across 18 institutions revealed significant limitations in how employer input is gathered and interpreted. Most notably, they found that:

Employer representatives in advisory roles typically come from larger companies, potentially missing needs of small and medium enterprises

Job posting analysis often reflects aspirational rather than essential skills

Competency statements frequently emphasize technical skills over less measurable but equally important capabilities

Few programs systematically validate competency frameworks with employees actually performing the work

These methodological limitations suggest the need for more robust, inclusive approaches to competency definition that capture diverse workplace realities.

A distinctive feature of quality CBE programs is their emphasis on authentic assessment—evaluations that mirror real-world tasks and problems. Northeastern University's Experiential Network connects students in competency-based programs with real organizational projects, resulting in portfolio artifacts that demonstrate applied capabilities (Northeastern University, 2023).

This approach produces:

Evidence of practical application rather than theoretical knowledge alone

Artifacts that graduates can present to potential employers

Development of metacognitive skills through reflection on performance

Networking opportunities through project-based engagement with organizations

Research by Ewell (2020) provides empirical support for authentic assessment approaches, finding that graduates of programs emphasizing portfolio development secured initial employment an average of 2.8 months faster than comparable graduates from traditional programs. However, his longitudinal analysis also noted that this advantage diminished over time, suggesting that portfolio approaches primarily influence initial employment rather than long-term career trajectories.

The most innovative CBE programs are embracing modular design through microcredentials and stackable pathways. Institutions like edX MicroMasters and Coursera's MasterTrack offer competency-based credentials that:

Can be completed in 3-9 months, providing quicker labor market entry points

Stack toward full degrees, allowing incremental progress

Provide discrete, verifiable skills that have immediate workplace value

Allow for specialization and customization based on career goals

Research by Credential Engine (2023) indicates that employers increasingly value these targeted credentials, with 68% of HR professionals reporting that they view microcredentials as valuable signals of specific competencies.

However, research by Carnevale et al. (2022) on credential market outcomes reveals important limitations. Their analysis of employment outcomes for microcredential holders found substantial variation by field, credential provider, and demographic characteristics. Specifically:

Microcredentials in technical fields showed stronger labor market returns than those in non-technical areas

Credentials from established institutions outperformed those from newer providers regardless of content

White and Asian credential holders saw significantly higher wage premiums than Black and Hispanic holders of identical credentials

Microcredentials rarely substituted for degrees in hiring decisions, functioning instead as supplements

These findings suggest that while microcredentials may enhance labor market outcomes in certain contexts, they are not a universal solution to employment challenges and may interact with existing patterns of labor market inequality.

A significant gap in current research is the limited longitudinal data on career trajectories of CBE graduates. While short-term employment outcomes are relatively well-documented, few studies follow graduates beyond 3-5 years. The longitudinal research that does exist, such as Bevans' (2021) ten-year follow-up study of early CBE graduates, suggests complex outcomes:

Initially higher employment rates but converging with traditional graduates by year 5

Lower initial salaries but faster early-career growth rates

More frequent job changes, both lateral and promotional

Higher rates of entrepreneurship and independent contracting

These patterns suggest that CBE graduates may experience different career development trajectories than traditional graduates—neither clearly better nor worse, but following distinct patterns that merit further investigation through robust longitudinal research.

While previous sections have examined the potential benefits and evidence-based practices in competency-based online education, a comprehensive analysis requires equal attention to the significant challenges and limitations that affect implementation. This section addresses four critical areas that often receive insufficient attention in discussions of CBE models: regulatory and quality assurance frameworks, technological access inequities, student support requirements, and faculty labor implications. These interrelated challenges reveal that CBE's theoretical promises often encounter practical barriers that require substantial institutional resources and structural adaptations to overcome. Rather than positioning these challenges as merely operational hurdles, this section frames them as fundamental considerations that should inform institutional decision-making about whether and how to implement competency-based approaches. By examining these limitations directly, the analysis contributes to a more balanced understanding of when CBE models may be appropriate and what supporting structures are necessary for their successful implementation.

Traditional accreditation models struggle to evaluate CBE programs effectively. The focus on inputs (faculty credentials, contact hours) rather than outcomes creates barriers for innovative models. While efforts like the Competency-Based Education Network (C-BEN) are developing quality frameworks, regulatory hurdles remain significant (Lurie & Garrett, 2023).

Recent developments in regulatory approaches show promising evolution. The Department of Education's 2022 guidance on direct assessment programs provided clearer pathways for CBE approval, while the 2021 EQUIP (Educational Quality through Innovative Partnerships) experimental sites initiative created opportunities for non-traditional providers to access federal financial aid through partnerships with accredited institutions (U.S. Department of Education, 2022).

However, as Brittingham (2020) notes in her analysis of accreditation innovation, significant tensions remain between the standardization necessary for quality assurance and the flexibility central to CBE models. The regional accreditors vary substantially in their approaches to CBE evaluation, creating inconsistent standards and potentially limiting program development in certain regions.

While online CBE can expand access, it also requires reliable technology and internet connectivity. The digital divide remains a substantial barrier, with approximately 15% of American households lacking broadband internet access (Pew Research Center, 2023). This disproportionately affects rural, low-income, and minority students—the very populations CBE aims to serve.

Research by Whitehead et al. (2021) examining technology access among online CBE students found that:

23% of rural students reported unreliable internet as a major barrier to program completion

34% of students from households earning less than $30,000 annually relied primarily on mobile devices for coursework

28% of all CBE students reported sharing computing devices with other household members

Technical support needs were highest among first-generation students and those over 45

These findings highlight the need for multifaceted approaches to technology access, including lending programs for devices, subsidized internet access, mobile-optimized learning platforms, and low-bandwidth alternatives for course materials.

Self-paced learning requires strong self-regulation skills that many students, particularly those from disadvantaged educational backgrounds, may lack. Successful CBE programs invest heavily in coaching and support services, but these add costs that can undermine affordability goals. Data from the Department of Education (2022) indicates that completion rates in fully online CBE programs average 15-20 percentage points lower than comparable campus-based programs.

Case studies of programs with above-average persistence rates reveal common support elements:

Proactive coaching models with regular, scheduled check-ins rather than on-demand support

Structured onboarding experiences that develop self-direction skills before full program entry

Peer community development through cohort models and facilitated interaction

Progress visualization tools that enhance motivation and metacognitive awareness

Early alert systems that identify struggling students before they disengage

Research by Chen and Starobin (2019) found that these support elements had differential impacts across student populations. First-generation students benefited most from proactive coaching and structured milestones, while students with previous college experience showed stronger responses to peer community and progress visualization tools. This suggests the need for personalized support approaches rather than one-size-fits-all models.

A critical dimension often overlooked in CBE discussions is the profound impact on faculty roles, workload, and professional identity. Traditional faculty functions are typically disaggregated in CBE models, with separate roles for content development, assessment, coaching, and subject matter expertise (McGee, 2021).

Research by the American Association of University Professors (2022) examining faculty experiences in CBE programs revealed mixed perceptions:

62% reported increased job specialization and reduced autonomy

48% noted concerns about job security and the shift toward contingent positions

57% reported higher student loads but more focused interactions

41% expressed concerns about intellectual property rights for course materials

72% indicated the need for professional development in assessment design

These findings highlight the need to consider faculty implications alongside student outcomes when evaluating CBE models. As Kezar and Maxey (2018) argue, sustainable CBE implementation requires attention to academic labor conditions, professional development needs, and the preservation of meaningful faculty-student relationships despite changed structures.

The analysis of competency-based online education through the accessibility triad lens yields distinct implications for various stakeholder groups navigating the changing higher education landscape.

Institutional decision-makers considering CBE implementation must conduct realistic assessments of organizational readiness, including technological infrastructure, faculty capacity for transformed roles, and financial sustainability beyond initial implementation funding. The evidence suggests that successful CBE programs require substantial front-end investment in competency development, assessment design, and support systems—costs that may not be immediately offset by efficiency gains. Moreover, institutions must consider their specific student demographics when evaluating potential access benefits, as the data reveals differential outcomes across student populations. Rather than wholesale adoption of CBE models, institutional leaders might consider targeted implementation in programs where workforce alignment is most critical and competency definition most straightforward.

Prospective students evaluating CBE options should critically assess their own learning preferences, self-regulation skills, and technological capacity. The research clearly indicates that students with strong self-direction skills, prior professional experience, and robust technological access benefit most from these models. Students should seek transparency from institutions regarding actual completion rates, time-to-completion distributions (not just averages), and post-graduation outcomes disaggregated by demographic characteristics. Additionally, students should carefully evaluate subscription pricing models against their realistic completion timeline, recognizing that slower progression may eliminate projected cost savings.

Policy implications center on creating regulatory frameworks that ensure quality while enabling innovation. The current accreditation system, designed for credit-hour models, creates unnecessary barriers to CBE implementation while simultaneously failing to adequately assess quality dimensions unique to competency-based approaches. Policy makers should develop specialized quality metrics for CBE programs that focus on learning outcomes, equity in completion rates, and labor market outcomes while maintaining sufficient standardization for credential recognition and transfer. Additionally, public funding models should incentivize robust support systems for disadvantaged students rather than merely rewarding accelerated completion, which may exacerbate existing educational inequities.

This analysis reveals significant gaps in current CBE research that warrant further investigation. Particularly needed are longitudinal studies tracking CBE graduates' career trajectories beyond initial employment, comparative analyses of learning outcomes between traditional and CBE approaches using consistent assessment frameworks, and mixed-methods research examining how students from diverse backgrounds experience and navigate CBE environments. Researchers should also investigate the efficacy of specific support interventions in improving outcomes for historically underserved populations in CBE settings.

By addressing these implications thoughtfully, stakeholders can contribute to educational models that genuinely enhance access, affordability, and labor market preparation while avoiding the pitfalls of implementing technological solutions without addressing underlying structural challenges in higher education.

The triad of access, affordability, and labor market preparation requires careful balancing within broader educational values. Based on the research examined, institutions seeking to develop effective competency-based online education should consider the following integrated approach:

Design backward from workforce needs while maintaining academic integrity and transferable skills development. Employ inclusive, methodologically sound competency development processes that incorporate diverse stakeholder perspectives.

Build robust support infrastructures that provide personalized coaching and community-building, particularly for students from disadvantaged educational backgrounds. Recognize that support is not an add-on but a core component of successful CBE implementation.

Leverage technology purposefully to reduce costs while enhancing learning, not as an end in itself. Address digital divide issues proactively through multiple access pathways and resource provision.

Create transparent assessment frameworks that clearly demonstrate competency to both students and employers, while acknowledging the limitations of standardized competency definitions in capturing the full range of valuable learning.

Develop financial models that align incentives for both institutions and students, rewarding progress and completion while ensuring sustainability. Consider differential pricing approaches that account for varying support needs across student populations.

Attend to faculty implications by developing new models of professional development, appropriate workload measures, and meaningful roles within disaggregated instructional systems.

Embed equity considerations throughout program design, implementation, and evaluation, recognizing that CBE approaches may unintentionally reproduce existing inequities without intentional intervention.

To assist educational leaders and students in evaluating alignment with competency-based education approaches, a comprehensive self-assessment instrument has been developed (see Appendix A), which measures individual preferences across the three dimensions of the accessibility triad. This assessment tool underwent rigorous validation procedures to ensure reliability and validity across diverse populations (see Appendix B for detailed validation methodology), making it suitable for both research applications and practical decision-making contexts.

The most successful competency-based online programs recognize that access without support isn't opportunity, affordability without quality isn't value, and labor market preparation without broader educational development isn't sustainable. By thoughtfully integrating these principles, institutions can create educational models that serve the diverse needs of today's students while preparing them for tomorrow's workforce challenges.

As higher education continues to navigate its evolving landscape, competency-based online models offer promising paths forward—but only if approached with critical thinking, evidence-based design, and unwavering commitment to student success in its broadest sense, while acknowledging that these models represent particular educational values that exist alongside other legitimate approaches to higher education.

The CBE Triad Self-Assessment is designed to help individuals evaluate their priorities and preferences related to competency-based online higher education. The assessment contains 15 questions across three dimensions: student access (5 questions), affordability (5 questions), and labor market preparation (5 questions).

When administering this assessment:

Randomize question order to prevent respondents from identifying which questions correspond to which dimension. This reduces potential response bias.

Provide clear instructions explaining that there are no right or wrong answers, only preferences that help determine educational model fit.

Use a consistent 5-point scale for all questions, with higher values (5) generally indicating stronger alignment with CBE models and lower values (1) indicating potential preference for traditional educational approaches.

Calculate dimension scores by summing responses within each category and converting to percentages (sum ÷ maximum possible score × 100).

Interpret results holistically, recognizing that high scores across multiple dimensions may indicate strong alignment with CBE models, while mixed scores suggest potential fit with hybrid approaches.

Provide personalized recommendations based on the pattern of responses across dimensions, not just individual dimension scores.

These questions assess the importance of flexibility, geographic accessibility, and learning environment adaptability.

- 1.

Scheduling Flexibility

Question: How important is having a flexible schedule when considering your education options?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I need to study at any time of day (5)

- ○

Very important - I prefer evening/weekend options (4)

- ○

Moderately important - Some flexibility is helpful (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I can generally adapt to schedules (2)

- ○

Not important - I prefer structured schedules (1)

- 2.

Geographic Constraints

Question: How significant are geographic limitations in your educational choices?Response Options:

Very significant - I cannot relocate or commute (5)

Significant - I'm limited to my immediate region (4)

Moderate - I can commute occasionally but not daily (3)

Slight - I prefer local options but can relocate if needed (2)

Not significant - I'm willing to relocate for education (1)

- 3.

Work/Life Impact on Attendance

Question: How much does your current work or family situation impact your ability to attend scheduled classes?Response Options:

- ○

Severely impacts - I have unpredictable or demanding responsibilities (5)

- ○

Significantly impacts - I have limited availability (4)

- ○

Moderately impacts - I can manage some scheduled commitments (3)

- ○

Slightly impacts - I have minor scheduling constraints (2)

- ○

Does not impact - I have flexibility for scheduled classes (1)

- 4.

Support Services Needs

Question: How important is having access to adaptive learning accommodations or support services?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I require specific accommodations (5)

- ○

Very important - I benefit significantly from support services (4)

- ○

Moderately important - I occasionally need additional support (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I rarely need accommodations (2)

- ○

Not important - I don't require specialized support (1)

- 5.

Digital Learning Comfort

Question: How comfortable are you with primarily digital learning environments?Response Options:

- ○

Very comfortable - I prefer digital learning (5)

- ○

Comfortable - I adapt well to online environments (4)

- ○

Moderately comfortable - I can manage digital learning (3)

- ○

Somewhat uncomfortable - I prefer some in-person elements (2)

- ○

Very uncomfortable - I strongly prefer in-person learning (1)

Dimension 2: Affordability

These questions evaluate cost sensitivity, time-to-completion priorities, and financial flexibility.

Question: How concerned are you about the total cost of your education?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely concerned - Cost is my primary consideration (5)

- ○

Very concerned - Cost is a major factor in my decision (4)

- ○

Moderately concerned - I balance cost with other factors (3)

- ○

Slightly concerned - I'm willing to pay more for quality (2)

- ○

Not concerned - I prioritize other factors over cost (1)

- 2.

Prior Learning Recognition

Question: How important is it to receive credit for skills and knowledge you already possess?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I want recognition for all prior learning (5)

- ○

Very important - I have substantial relevant experience (4)

- ○

Moderately important - I have some relevant experience (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I have limited relevant experience (2)

- ○

Not important - I prefer to start fresh (1)

Question: How quickly do you need to complete your education program?Response Options:

- ○

As quickly as possible - Time is a critical factor (5)

- ○

Relatively quickly - I prefer an accelerated timeline (4)

- ○

Standard pace - A traditional timeline is acceptable (3)

- ○

Somewhat relaxed pace - I prefer to take more time if needed (2)

- ○

No time pressure - I can take as long as necessary (1)

Question: How concerned are you about minimizing student loan debt?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely concerned - I want to avoid debt entirely (5)

- ○

Very concerned - I want to minimize debt as much as possible (4)

- ○

Moderately concerned - Some debt is acceptable (3)

- ○

Slightly concerned - I'm comfortable with reasonable debt (2)

- ○

Not concerned - Debt repayment is not a major concern (1)

- 5.

Support Services Value

Question: How willing are you to pay more for education that includes extensive support services?Response Options:

- ○

Very willing - Support services are worth the additional cost (1)

- ○

Somewhat willing - I value support but am price-sensitive (2)

- ○

Neutral - It depends on the specific services offered (3)

- ○

Somewhat unwilling - I prefer lower costs with fewer services (4)

- ○

Very unwilling - I prioritize lowest possible cost (5)

Dimension 3: Labor Market Preparation

These questions assess the importance of career relevance, skill development, and employment connections.

Question: How important is it that your education directly prepares you for specific job roles?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I want education that leads directly to employment (5)

- ○

Very important - Career preparation is a major priority (4)

- ○

Moderately important - I value both career skills and broader education (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I prefer broader education with some career elements (2)

- ○

Not important - I prioritize knowledge over job preparation (1)

- 2.

Industry Credential Value

Question: How important is earning industry-recognized credentials as part of your education?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - Industry credentials are essential (5)

- ○

Very important - I value credentials alongside my degree (4)

- ○

Moderately important - Some credentials would be beneficial (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I'm primarily focused on my degree (2)

- ○

Not important - The degree alone is sufficient (1)

Question: How important is developing a portfolio of work samples or projects during your education?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I need concrete evidence of my skills (5)

- ○

Very important - A portfolio would significantly help my career (4)

- ○

Moderately important - Some work samples would be valuable (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I'm more focused on theoretical knowledge (2)

- ○

Not important - I don't expect to need a portfolio (1)

Question: How important is it that your education includes direct connections with potential employers?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I want integrated employer partnerships (5)

- ○

Very important - Strong employer connections are valuable (4)

- ○

Moderately important - Some employer interaction is beneficial (3)

- ○

Slightly important - I prefer to focus on academics first (2)

- ○

Not important - I'll handle employer connections independently (1)

Question: How important is it that your education focuses on the most current industry practices?Response Options:

- ○

Extremely important - I need the most up-to-date skills (5)

- ○

Very important - Currency is a major priority (4)

- ○

Moderately important - A mix of foundational and current is ideal (3)

- ○

Slightly important - Foundational knowledge is more valuable (2)

- ○

Not important - I prioritize enduring concepts over trends (1)

Scoring and Interpretation

For each dimension, calculate the total score by summing the points from all five questions in that category. Convert to a percentage:

Dimension Percentage = (Sum of dimension responses ÷ 25) × 100

Interpretation guidelines:

80-100%: Very high alignment with this dimension of CBE

60-79%: Strong alignment

40-59%: Moderate alignment

20-39%: Limited alignment

0-19%: Minimal alignment

The overall pattern across dimensions provides insight into whether fully online CBE, hybrid models, or traditional education would best meet the individual's needs and preferences.

The Competency-Based Education Triad Self-Assessment underwent a systematic development and validation process to ensure its reliability, validity, and utility for both research and practical applications. This appendix details the multi-phase validation procedures employed.

Phase 1: Conceptual Framework Development

The assessment's theoretical foundation was established through comprehensive literature review spanning five domains:

Competency-based education research (2010-2023)

Online learning accessibility studies

Higher education affordability literature

Labor market alignment in postsecondary education

Educational assessment design principles

A panel of seven subject matter experts (SMEs) including three researchers, two CBE program administrators, one policy analyst, and one adult learning specialist reviewed the conceptual framework. Using a modified Delphi technique, the panel evaluated whether the three dimensions (access, affordability, labor market preparation) adequately captured the critical factors influencing student decisions regarding CBE programs. After three rounds of review, consensus was reached on the three-dimensional structure with 93% agreement among experts.

Phase 2: Item Pool Generation and Content Validation

An initial pool of 42 items (14 per dimension) was developed based on the literature review and expert input. Items were written to reflect varying levels of alignment with CBE models across each dimension.

Content Validity Review Process:

- 1.

Expert Rating Panel: Nine content experts (different from the conceptual framework panel) independently rated each item on:

- ○

Relevance to the specified dimension (1-4 scale)

- ○

Clarity of wording (1-4 scale)

- ○

Potential bias or sensitivity concerns (open-ended feedback)

- 2.

Content Validity Index (CVI) Calculation: Following the procedure outlined by Lynn (1986), item-level CVIs and scale-level CVIs were calculated.

- ○

Individual item CVIs ranged from 0.67 to 1.00

- ○

Items with CVIs below 0.78 were either eliminated or substantially revised

- ○

The scale-level CVI was 0.87, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.80

- 3.

Cognitive Interviews: Ten individuals representing diverse educational backgrounds, ages, and demographics participated in think-aloud cognitive interviews while completing the assessment. This process identified items with unclear wording, ambiguous terminology, or response options that were not mutually exclusive.

- 4.

Item Refinement: Based on expert ratings and cognitive interviews, the item pool was refined to 28 items with strongest content validity evidence.

Phase 3: Pilot Testing and Psychometric Validation

The 28-item assessment was administered to a stratified random sample of 412 adults (ages 19-64) considering or currently enrolled in higher education programs. The sample demographics included:

58% female, 40% male, 2% non-binary/other

48% employed full-time, 23% employed part-time, 29% not currently employed

31% with no prior college, 42% with some college but no degree, 27% with associate degree or higher

Racial/ethnic distribution: 62% White, 18% Black, 13% Hispanic/Latino, 5% Asian, 2% other

Statistical Analyses

1. Item Analysis:

Item difficulty indices ranged from 0.32 to 0.78, indicating appropriate variation

Item discrimination indices (corrected item-total correlations) ranged from 0.41 to 0.76

Inter-item correlations were examined to identify redundancies

2. Dimensional Structure Analysis:

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using principal axis factoring with oblique rotation

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy: 0.84

Bartlett's test of sphericity: χ²(378) = 4,152.37, p < .001

Parallel analysis supported a three-factor solution explaining 62.3% of variance

Pattern matrix loadings confirmed most items loaded on their theorized dimensions

Five items with significant cross-loadings or weak primary loadings were eliminated

3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis:

The refined 23-item model was tested with CFA

Model fit indices: CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.058 (90% CI: 0.049-0.067), SRMR = 0.061

All items showed significant loadings on their respective factors (p < .001)

Modification indices suggested correlating error terms for two item pairs, which improved model fit

4. Reliability Analysis:

- ●

Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha):

- ○

Access dimension: α = 0.86

- ○

Affordability dimension: α = 0.83

- ○

Labor market preparation dimension: α = 0.89

- ○

Overall assessment: α = 0.82

- ●

Test-retest reliability (n=58, 3-week interval): r = 0.84

5. Convergent and Discriminant Validity:

- ●

Convergent validity was supported by moderate to strong correlations with established measures:

- ○

Access dimension correlated with the Barriers to Learning Scale (r = 0.72)

- ○

Affordability dimension correlated with the Financial Concerns in Education Scale (r = 0.68)

- ●

Labor market preparation dimension correlated with the Career Focus Inventory (r = 0.75)

- ○

Discriminant validity was supported by weak correlations with theoretically unrelated constructs:

- ○

All dimensions showed low correlations (r < 0.30) with the Academic Interest Scale

- ○

All dimensions showed low correlations (r < 0.25) with the General Self-Efficacy Scale

Phase 4: Final Item Selection and Cross-Validation

Based on comprehensive psychometric analysis, the final assessment was refined to 15 items (5 per dimension) with the strongest validity evidence. This version was cross-validated with a new sample of 285 participants with similar demographic characteristics to the pilot sample.

The 15-item version maintained strong psychometric properties:

Dimensional structure confirmed by CFA (CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.052)

Internal consistency: Access (α = 0.84), Affordability (α = 0.81), Labor market preparation (α = 0.87)

Test-retest reliability (2-week interval): r = 0.86

Phase 5: Predictive Validity Studies

Two studies examined the predictive validity of the assessment:

Study 1: Program Selection Prediction

203 prospective students completed the assessment and were followed for 6 months

Higher scores across all dimensions significantly predicted enrollment in CBE programs over traditional programs (logistic regression: χ²(3) = 48.32, p < .001)

The model correctly classified 76.4% of participants' eventual enrollment decisions

Study 2: Program Satisfaction Correlation

178 students enrolled in various higher education formats completed the assessment and a program satisfaction survey

Congruence between assessment results and actual program characteristics significantly predicted satisfaction (r = 0.63, p < .001)

Students whose educational format matched their highest-scoring dimension reported significantly higher satisfaction than those with mismatched formats (t(176) = 5.92, p < .001)

Limitations and Ongoing Validation

Despite rigorous development, several limitations should be acknowledged:

Self-Report Bias: As with all self-assessments, responses may be influenced by social desirability and limited self-awareness. Correlations with behavioral measures should be examined in future research.

Cultural Validation: While the validation sample was demographically diverse, more focused validation with specific cultural and linguistic groups is needed to ensure measurement invariance across populations.

Longitudinal Stability: The test-retest period was relatively short (2-3 weeks). Longer-term stability should be examined in future research.

Contextual Factors: The assessment focuses on individual preferences but does not capture contextual factors (institutional characteristics, geographic options) that may constrain choices regardless of preferences.

Ongoing validation efforts include:

Multi-institutional implementation studies

Examination of predictive validity for student persistence and completion

Development of culturally-adapted versions

Integration with other educational decision-making instruments

References

- American Association of University Professors. (2022). Faculty in competency-based education programs: Roles, experiences, and professional identity. AAUP Research Report Series.

- Anderson, T. (2021). Challenges in implementing heutagogical principles in online competency-based programs. Distance Education, 42(3), 383-401.

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Bevans, J. (2021). A decade after graduation: Career trajectories of competency-based education graduates. Journal of Education and Work, 34(5), 521-539.

- Blaschke, L. M. (2021). The theory of heutagogy and self-determined learning. In S. Hase & C. Kenyon (Eds.), Self-determined learning: Heutagogy in action (2nd ed., pp. 3-24). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. [CrossRef]

- Brightwell, A., & Grant, J. (2013). Competency-based training: Who benefits? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 89(1048), 107-110.

- Brittingham, B. (2020). Accreditation and innovation: Navigating regulatory challenges in higher education. Higher Education Policy, 33(2), 221-239.

- Capella University. (2023). FlexPath program outcomes and student success report. Capella University Press.

- Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., & Campbell, K. P. (2022). The market value of alternative credentials. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

- Chen, J., & Starobin, S. S. (2019). Measuring and examining general self-efficacy among community college students: A structural equation modeling approach. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 43(5), 353-370.

- College Board. (2023). Trends in college pricing 2023. College Board Publications.

- Credential Engine. (2023). Counting U.S. postsecondary and secondary credentials. Credential Engine.

- Davidson, C. N. (2019). The new education: How to revolutionize the university to prepare students for a world in flux. Basic Books.

- Desrochers, D. M., & Staisloff, R. L. (2021). The cost and economics of competency-based education. American Institutes for Research.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. (2020). European competence frameworks in education and training: Policy and implementation progress. CEDEFOP Reference Series.

- Ewell, P. T. (2020). Authentic assessment in higher education: Impact on employment outcomes and career progression. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(7), 982-997.

- Federal Reserve. (2023). Consumer credit – G.19: Student loans outstanding. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Fishman, R., Nguyen, S., & Ezeudu, C. (2022). The changing profile of college students: Demographics, enrollment patterns, and completion rates. New America Foundation.

- Grant, P., Little, A. W., & Samson, M. (2018). Historical perspectives on competency-based education. Higher Education, Policy, and Practice, 3(1), 15-33.

- Guskey, T. R. (2010). Lessons of mastery learning. Educational Leadership, 68(2), 52-57.

- Hodge, S. (2007). The origins of competency-based training. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 47(2), 179-209.

- Hora, M. T. (2020). Beyond the skills gap: How the vocationalist framing of higher education undermines student, employer, and societal interests. Journal of Education and Work, 33(4), 367-383.

- Hora, M. T., Benbow, R. J., & Smolarek, B. B. (2021). Critical perspectives on employer-aligned curriculum development processes in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 92(5), 783-809.

- Johnson, M., & Rodríguez, D. (2021). Lessons learned from discontinued competency-based programs: Challenges in implementation and scale. The Journal of Competency-Based Education, 6(2), 112-127.

- Jonassen, D. H. (2019). Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design (3rd ed.). Educational Technology Publications.

- Kelchen, R. (2017). The potential impacts of differential tuition across income groups and academic programs. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(5), 725-752.

- Kelchen, R. (2019). Does the Bennett Hypothesis hold in a competency-based environment? Evidence from Western Governors University. Journal of Human Capital, 13(3), 421-447.

- Kezar, A., & Maxey, D. (2018). The faculty role in high-impact practices: Building and sustaining structures to support. Peer Review, 20(2), 9-14.

- Klein-Collins, R., & Olson, R. (2022). Making the case for prior learning assessment: Research findings on PLA outcomes. Council for Adult and Experiential Learning.

- Klein-Collins, R., Palmer, I., & Nguyen, S. (2021). What we know about competency-based education: Research evidence and implications for policy and practice. Lumina Foundation.

- Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in action: Applying modern principles of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

- Lumina Foundation. (2023). Today's student: A portrait of college-going Americans. Lumina Foundation.

- Lurie, H., & Garrett, R. (2023). Deconstructing CBE: An assessment of institutional activity, goals, and challenges in higher education. Competency-Based Education Network.

- Lynn, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35(6), 382-385. [CrossRef]

- Mager, R. F. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives. Fearon Publishers.

- Matthews, K. E., Belward, S., & Thompson, K. (2023). Designing inclusive learning experiences in competency-based education. Journal of Competency-Based Education, 8(1), 12-26.

- McGee, P. (2021). Faculty perspectives on unbundling in higher education: A case study of faculty in a competency-based program. Innovative Higher Education, 46(2), 213-229.

- Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons' responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50(9), 741-749.

- Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2020). A new decade for assessment: Embedding equity into assessment praxis. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

- Morcke, A. M., Dornan, T., & Eika, B. (2013). Outcome (competency) based education: An exploration of its origins, theoretical basis, and empirical evidence. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(4), 851-863. [CrossRef]

- National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2023). Job outlook 2023. NACE.

- Nodine, T., & Johnstone, S. M. (2022). Competency-based education: A framework for measuring quality courses. Journal of Competency-Based Education, 7(2), 87-102.

- Northeastern University. (2023). Experiential Network outcomes report: Measuring the impact of project-based learning. Northeastern University Press.

- Norton, A., & Cherastidtham, I. (2018). Mapping Australian higher education 2018. Grattan Institute.

- Ortagus, J. C., & Yang, L. (2018). An examination of the influence of decreases in state appropriations on online enrollment at public universities. Research in Higher Education, 59(7), 847-865. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. (2023). Internet/broadband fact sheet. Pew Research Center.

- Rivera, J., & Matthews, J. (2021). Competency-based education at community colleges: Challenges in implementation and equity impact. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 45(11), 825-841.

- Spady, W. G. (1994). Outcome-based education: Critical issues and answers. American Association of School Administrators.

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355-374.

- Springer, P. J. (2021). Hidden costs in competency-based education: A longitudinal cost analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 43(2), 266-288.

- Stevens, K., Gerber, D., & Hendra, R. (2020). Prior learning assessment practices across higher education: Patterns of usage and equity outcomes. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(3), 377-392.

- Svinicki, M., & McKeachie, W. (2020). McKeachie's teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(3), 281-294.

- University of Wisconsin System. (2022). UW flexible option impact report: Five years of flexible education. University of Wisconsin Press.

- U.S. Department of Education. (2022). Outcome measures for distance and competency-based education programs. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Voorhees, R. A. (2001). Competency-based learning models: A necessary future. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2001(110), 5-13. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, B. M., Jensen, D. F. N., & Boschee, F. (2021). Digital inequality in higher education: Evidence from online competency-based programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 48, 100776.

- Willis, G. B. (2015). Analysis of the cognitive interview in questionnaire design. Oxford University Press.

- Wood, S. G., Smith, S. J., & Serianni, B. A. (2021). Accessibility in online courses: A review of accommodation designs and barriers. Journal of Special Education Technology, 36(2), 78-90.

- Xu, D., & Xu, Y. (2019). The promises and limits of online higher education: Understanding how distance education affects access, cost, and quality. American Enterprise Institute.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).