Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

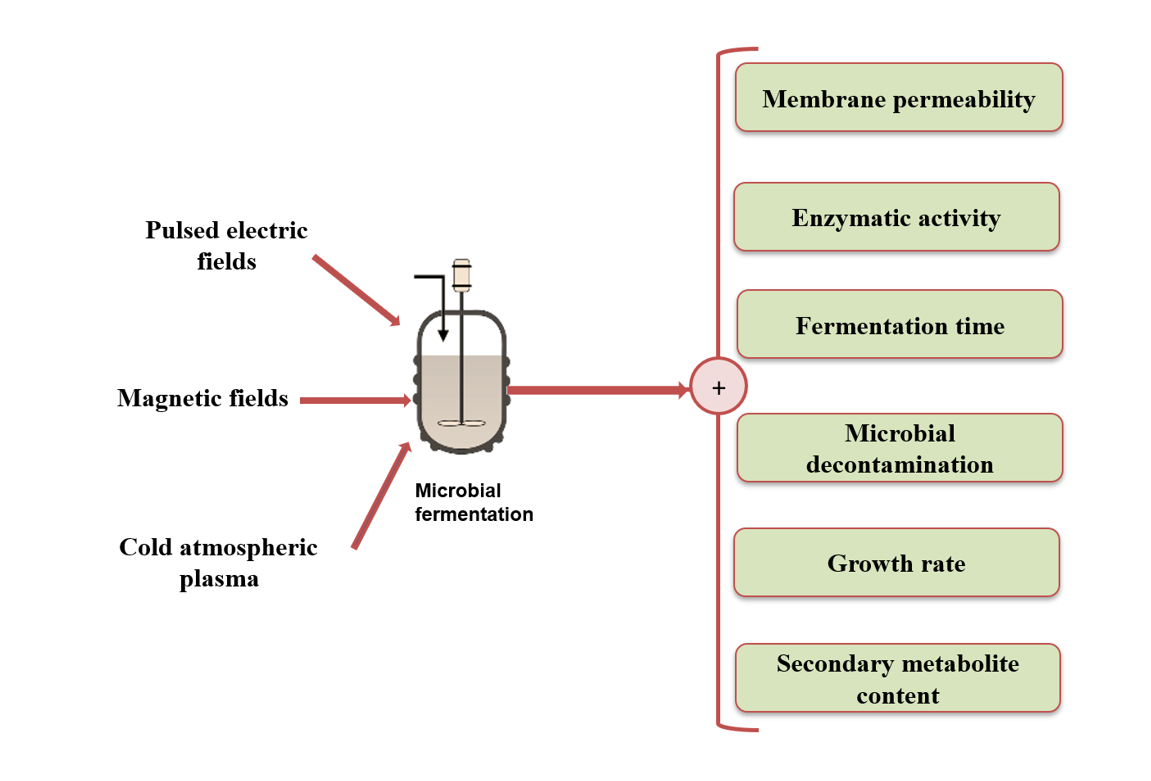

2. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) on Fermentation and Food Processing

2.1. Fundamental Aspects of Pulsed Electric Fields

2.2. Effect of PEF on Microbial Activity and Fermentation

2.2.1. Bacteria

2.2.2. Yeast and Mold

2.2.3. Microalgae

2.3. Use of Pulsed Electric Field for Fermented Foods

3. Effect of Magnetic Field on Fermentation

3.1. Fundamental Aspects of Magnetic Field

3.2. Application of Magnetic Field in Microbial Fermentation

3.2.1. Magnetic Fields on Bacteria

3.2.2. Effect of Magnetic Fields on Yeasts and Fungus

3.2.3. Effect of Magnetic Fields on Microalgae

Enhanced Biomass Concentration and Product Yield

Variable Effects Based on Growth Environment

4. Effect of cold Atmospheric Plasma on Fermentation

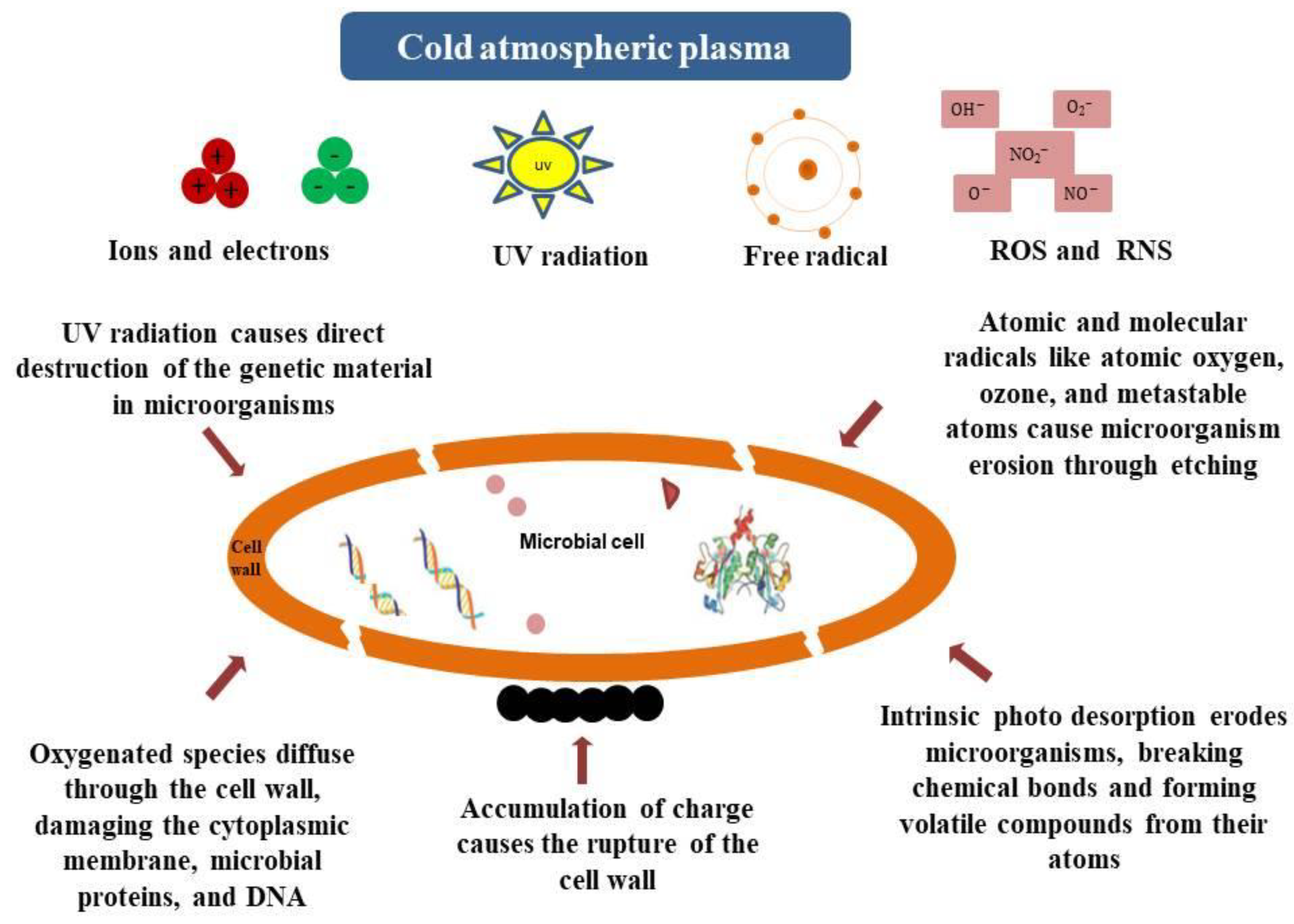

4.1. Fundamental Aspects of Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP)

4.2. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Combined with Fermentation

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PEF | Pulsed electric fields |

| MF | Magnetic fields |

| CAP | Cold atmospheric plasma |

References

- Tamang, J.P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W.H. Diversity of Microorganisms in Global Fermented Foods and Beverages. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Obadina, A.O.; Adebo, O.A.; Kayitesi, E. Fermented and Malted Millet Products in Africa: Expedition from Traditional/Ethnic Foods to Industrial Value-Added Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Adeboye, A.S.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Sobowale, S.S.; Ogundele, O.M.; Kayitesi, E. Advances in Fermentation Technology for Novel Food Products. In Innovations in Technologies for Fermented Food and Beverage Industries; Panda, S.K., Shetty, P.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; AL-Ansi, W.; Mahdi, A.A. Microbial Enzymes Produced by Fermentation and Their Applications in the Food Industry—A Review. Int. J. Agric. Innov. Res. 2019, 8, 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Banu, J.R.; Kumar, G.; Chattopadhyay, I. Management of Microbial Enzymes for Biofuels and Biogas Production by Using Metagenomic and Genome Editing Approaches. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rivero, C.; López-Gómez, J.P. Unlocking the Potential of Fermentation in Cosmetics: A Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Mathad, G.N.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Combinations of Emerging Technologies with Fermentation: Interaction Effects for Detoxification of Mycotoxins? Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Lu, M.; Shangguan, Y.; Liu, X. Mechanism of Dielectric Barrier Plasma Technology to Improve the Quantity and Quality of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Anaerobic Fermentation of Cyanobacteria. Waste Manag. 2023, 155, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jin, Y.; Yang, N.; Wei, L.; Xu, D.; Xu, X. Improving Microbial Production of Value-Added Products through the Intervention of Magnetic Fields. Bioresource Technology 2024, 393, 130087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, K.S.; Mason, T.J.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Kerry, J.P.; Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound Technology for Food Fermentation Applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, M.; Barba-Orellana, S.; Roselló-Soto, E.; Barba, F.J. Gamma Irradiation and Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation Technologies; Ojha, K.S., Tiwari, B.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Rastogi, N.K. High Pressure Processing for Food Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation Technologies; Ojha, K.S., Tiwari, B.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Arias, M.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Pulsed Electric Field and Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation. In Novel Food Fermentation Technologies; Ojha, K.S., Tiwari, B.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 85–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, J. Review of Cold Plasma Pretreatment Reinforces the Lignocellulose-Derived Aldehyde Inhibitors Tolerance and Bioethanol Fermentability for Zymomonas mobilis, by X. Xu. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, K.; Nabi, B.G.; Arshad, R.N.; Roobab, U.; Yaseen, B.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Aadil, R.M.; Ibrahim, S.A. Potential Impact of Ultrasound, Pulsed Electric Field, High-Pressure Processing and Microfludization against Thermal Treatments Preservation Regarding Sugarcane Juice (Saccharum officinarum). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 90, 106194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U.S.; Deshmukh, R.R. Non-Thermal Technologies for Food Processing. Front. Nutr. 8, 657090. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marszałek, K.; Woźniak, Ł.; Wiktor, A.; Szczepańska, J.; Skąpska, S.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Saraiva, J.A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J. Emerging Technologies and Their Mechanism of Action on Fermentation. In Fermentation. In Fermentation Processes; Koubaa, M., Barba, F.J., Roohinejad, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-de La Peña, M.; Miranda-Mejía, G.A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Recent Trends in Fermented Beverages Processing: The Use of Emerging Technologies. Beverages 2023, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklavčič, D. Network for Development of Electroporation-Based Technologies and Treatments: COST TD1104. J. Membr. Biol. 2012, 245, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Yadav, B.; Roopesh, M.S.; Jo, C. Cold Plasma for Effective Fungal and Mycotoxin Control in Foods: Mechanisms, Inactivation Effects, and Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckow, R.N.G.S.; Toepfl, S. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of Orange Juice: A Review on Microbial, Enzymatic, Nutritional, and Sensory Quality and Stability. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; López, N.; Saldaña, G.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Evaluation of Phenolic Extraction during Fermentation of Red Grapes Treated by a Continuous Pulsed Electric Fields Process at Pilot-Plant Scale. J. Food Eng. 2010, 98, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrić, D.; Barba, F.; Roohinejad, S.; Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Radojčin, M.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Pulsed Electric Fields as an Alternative to Thermal Processing for Preservation of Nutritive and Physicochemical Properties of Beverages: A Review. J. Food Process. Eng. 2018, 41, e12638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Pulsed Electric Fields as Pretreatment for Subsequent Food Process Operations. In Handbook of Electroporation; Miklavcic, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-D’Alessandro, L.; Carciochi, R. Fermentation Assisted by Pulsed Electric Field and Ultrasound: A Review. Fermentation 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Parniakov, O.; Pereira, S.A.; Wiktor, A.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Saraiva, J.A.; Raso, J.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; et al. Current Applications and New Opportunities for the Use of Pulsed Electric Fields in Food Science and Industry. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.J.; Lopes, R.P.; Koubaa, M.; Roohinejad, S.; Barba, F.J.; Delgadillo, I.; Saraiva, J.A. Fermentation at Non-Conventional Conditions in Food- and Bio-Sciences by the Application of Advanced Processing Technologies. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lye, H.S.; Karim, A.A.; Rusul, G.; Liong, M.T. Electroporation Enhances the Ability of Lactobacilli to Remove Cholesterol. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4820–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najim, N.; Aryana, K.J. A Mild Pulsed Electric Field Condition That Improves Acid Tolerance, Growth, and Protease Activity of Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-K and Lactobacillus delbrueckii Subspecies bulgaricus LB-12. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 3424–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohba, T.; Uemura, K.; Nabetani, H. Moderate Pulsed Electric Field Treatment Enhances Exopolysaccharide Production by Lactococcus lactis Subspecies cremoris. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral, M.; Pankiewicz, U.; Sujka, M.; Kowalski, R. Bioaccumulation of Zinc Ions in Lactobacillus rhamnosus B 442 Cells under Treatment of the Culture with Pulsed Electric Field. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanafusa, S.; Uhlig, E.; Uemura, K.; Gómez Galindo, F.; Håkansson, Å. The Effect of Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field on the Production of Metabolites from Lactic Acid Bacteria in Fermented Watermelon Juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 72, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.H.; Mohammed, H.; El-Gebaly, R.H.; Adam, M.; Ali, F.M. Pulsed Electric Field at Resonance Frequency Combat Klebsiella pneumoniae Biofilms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Jing, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X.; Sheng, Q.; Yue, T.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y. Inactivation Activity and Mechanism of High-Voltage Pulsed Electric Fields Combined with Antibacterial Agents against Alicyclobacillus spp. in Apple Juice. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 431, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fologea, D.; Vassu-Dimov, T.; Stoica, I.; Csutak, O.; Radu, M. Increase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Plating Efficiency after Treatment with Bipolar Electric Pulses. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1998, 46, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, J.R.; Turk, M.F.; Nonus, M.; Lebovka, N.I.; Zakhem, H.E.; Vorobiev, E. S. S. cerevisiae Fermentation Activity after Moderate Pulsed Electric Field Pre-Treatments. Bioelectrochem. 2015, 103, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiewicz, U.; Sujka, M.; Kowalski, R.; Mazurek, A.; Włodarczyk-Stasiak, M.; Jamroz, J. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) on Accumulation of Selenium and Zinc Ions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cells. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delso, C.; Berzosa, A.; Sanz, J.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed Electric Field Processing as an Alternative to Sulfites (SO2) for Controlling Saccharomyces cerevisiae Involved in the Fermentation of Chardonnay White Wine. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedurek, J. Influence of a Pulsed Electric Field on the Spores and Oxygen Consumption of Aspergillus niger and Its Citric Acid Production. Acta Biotechnol. 1999, 19, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Daccache, M.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Salameh, D.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Fermentation of Hanseniaspora sp. Yeast Isolated from Lebanese Apples. Yeast Isolated from Lebanese Apples. Food Res. Int. 129, 108840. [CrossRef]

- Kerns, G.; Bauer, E.; Berg, H. Electrostimulation of Cellulase Fermentation by Pulsatile Electromagnetically Induced Currents. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1993, 32, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, A.; Barron, N.; McHale, L.; McHale, A.P. Increased Efficiency of Substrate Utilization by Exposure of the Thermotolerant Yeast Strain, Kluyveromyces marxianus IMB3 to Electric-Field Stimulation. Biotechnol. Tech. 1995, 9, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberkorn, I. Continuous Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field Treatments Foster the Upstream Performance of Chlorella vulgaris-Based Biorefinery Concepts. Bioresource Technology 2019, 293, 122029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, L.; Frey, W.; Gusbeth, C.; Ravaynia, P.S.; Mathys, A. Effect of Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field Treatment on Cell Proliferation of Microalgae. Bioresource Technology 2019, 271, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Corripio, G.; La Peña, M.M.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Guerrero-Beltrán, J.Á. Pulsed Electric Field Processing of a Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Fermented Beverage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 79, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Cabral, D.; Valdez-Fragoso, A.; Rocha-Guzman, N.E.; Moreno-Jimenez, M.R.; Gonzalez-Laredo, R.F.; Morales-Martinez, P.S.; Rojas-Contreras, J.A.; Mujica-Paz, H.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A. Effect of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF)-Treated Kombucha Analogues from Quercus obtusata Infusions on Bioactives and Microorganisms. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 34, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 47 Knirsch, M.C.; Alves Dos Santos, C.; Martins De Oliveira Soares Vicente, A.A.; Vessoni Penna, T.C. Ohmic Heating – A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darra, N.; Turk, M.F.; Ducasse, M.-A.; Grimi, N.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Changes in Polyphenol Profiles and Color Composition of Freshly Fermented Model Wine due to Pulsed Electric Field, Enzymes and Thermovinification PreTreatments. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, N.; Puértolas, E.; Condón, S.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields on the Extraction of Phenolic Compounds during the Fermentation of Must of Tempranillo Grapes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Ferrari, G.; Fruilo, M.; Pataro, G. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Vinification of Aglianico and Piedirosso Grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11606–11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; Barba, F.J. Electrotechnologies Applied to Valorization of By-Products from Food Industry: Main Findings, Energy and Economic Cost of Their Industrialization. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 100, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abca, E.E.; Akdemir Evrendilek, G. Processing of Red Wine by Pulsed Electric Fields with Respect to Quality Parameters: PEF Processing of Red Wine. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Mejía, G.A.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V.; Morales-de la Peña, M.; Martín-Belloso, O. Modulating Yogurt Fermentation Through Pulsed Electric Fields and Influence of Milk Fat Content. Foods 2025, 14, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, G.; Cebrián, G.; Abenoza, M.; Sánchez-Gimeno, C.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Assessing the Efficacy of PEF Treatments for Improving Polyphenol Extraction during Red Wine Vinifications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 39, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Zeng, X.A.; Ren, E.-F.; Xu, F.-Y.; Li, J.; Wang, M.-S.; Wang, R. Review of the Application of Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) Technology for Food Processing in China. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Y.; Yang, R.J.; Wu, L.; Zhao, W. Effects of Pulsed Electric Field on the Sterilization and Aging of Fermented Orange Vinegar. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2015, 36, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Yin, Y.G.; Fan, S.M.; Zhu, C.; Luo, G.C. GC–MS Analysis of Aroma Component Variation of Wine Treated by High Voltage Pulse Electric Field. Food Sci. 2006, 27, 654–657. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, R.B.; Wang, X.Q.; Luo, W.; Mo, M.B.; Wang, L.M.; et al. Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields on Phenols and Colour in Young Red Wine. Spectrosc. Spect. Anal. 2010, 30, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanos, P.; Warncke, M.C.; Ehrmann, M.A.; Hertel, C. Application of Mild Pulsed Electric Fields on Starter Culture Accelerates Yogurt Fermentation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.; Liong, M. Effect of Electroporation on Viability and Bioconversion of Isoflavones in Mannitol-Soymilk Fermented by Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Mejía, G.A.; Del Campo-Barba, S.T.M.; Arredondo-Ochoa, T.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V.; La Peña, M.M. Low-Intensity Pulsed Electric Fields Pre-Treatment on Yogurt Starter Culture: Effects on Fermentation Time and Quality Attributes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 95, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, D.H.; Jeon, B.Y.; Park, D.H. Effects of an Electric Pulse on Variation of Bacterial Community and Metabolite Production in Kimchi-Making Culture. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2013, 18, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Gu, H.L.; Ju, H.; Jeon, J.; Jeong, S.-H.; Lee, D.-U. Effects of Pulsed Electric Fields on Controlling Fermentation Rate of Brined Raphanus sativus. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 92, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miñano, H.L.A.; Silva, A.C.D.S.; Souto, S.; Costa, E.J.X. Magnetic Fields in Food Processing Perspectives, Applications and Action Models. Processes 2020, 8, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, F.; Hu, H.; Liu, S.; Han, J. Experimental Study on Freezing of Liquids under Static Magnetic Field. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 25, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, L.; Rodríguez, A.C.; Pérez-Mateos, M.; Sanz, P.D. Effects of Magnetic Fields on Freezing: Application to Biological Products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jin, Y.; Hong, T.; Yang, N.; Cui, B.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z. Effect of Static Magnetic Field on the Quality of Frozen Bread Dough. LWT 2022, 154, 112670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, T.; Yamane, Y.-I.; Watanabe, M.; Sasaki, K. Stimulation of Porphyrin Production by Application of an External Magnetic Field to a Photosynthetic Bacterium, Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003, 95, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, D.C.; Pérez, V.H.; Justo, O.R.; Alegre, R.M. Effect of the Extremely Low Frequency Magnetic Field on Nisin Production by Lactococcus lactis Subsp. Lactis Using Cheese Whey Permeate. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L.W.E.; Murugan, N.J.; Persinger, M.A. Bacterial Growth Rates are Influenced by Cellular Characteristics of Individual Species When Immersed in Electromagnetic Fields. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 172, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strašák, L.; Vetterl, V.; Šmarda, J. Effects of Low-Frequency Magnetic Fields on Bacteria Escherichia coli. Bioelectrochemistry 2002, 55, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wang, J.; Mei, Y.; Ge, L.; Qian, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; et al. Antibiofilm Mechanism of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Cold Plasma against Pichia manshurica. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 85, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sincak, M.; Turker, M.; Derman, Ü.C.; Alkan, G.; Budak, M.; Çakıroğulları, B. Exploring the Impact of Magnetic Fields on Biomass Production Efficiency under Aerobic and Anaerobic Batch Fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubanja, I.N.; Lončarević, B.; Lješević, M.; Beškoski, V.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Velikić, Z.; Stanisavljev, D. The Influence of Low-Frequency Magnetic Field Regions on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Respiration and Growth. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 143, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutmeyer, A.; Raman, R.; Murphy, P.; Pandey, S. Effect of Magnetic Field on the Fermentation Kinetics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2011, 2, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, R.; Mitsui, Y.; Yoshizaki, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Takamine, K.; Koyama, K. Controlling the Growth of Yeast by Culturing in High Magnetic Fields. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 586, 171193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerana, M.; Yu, N.-N.; Bae, S.-J.; Kim, I.; Kim, E.-S.; Ketya, W.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, N.-Y.; Park, G. Enhancement of Fungal Enzyme Production by Radio-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, G.F.; Perez, V.H.; Justo, O.R.; et al. Glycerol Bioconversion in Unconventional Magnetically Assisted Bioreactor Seeking Whole Cell Biocatalyst (Intracellular Lipase) Production. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 111, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H. Effect of Low-Intensity Magnetic Field on the Growth and Metabolite of Grifola frondosa in Submerged Fermentation and Its Possible Mechanisms. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deamici, K.M.; Cardias, B.B.; Costa, J.A.V.; Santos, L.O. Static Magnetic Fields in Culture of Chlorella fusca: Bioeffects on Growth and Biomass Composition. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asundi, S.; Rout, S.; Stephen, S.; Khandual, S.; Dutta, S.; Kumar, S. Parametric Study of the Effect of Increased Magnetic Field Exposure on Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris Growth and Bioactive Compound Production. Phycology 2024, 4, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.M.; Costa, J.A.V.; Da Rosa, A.P.C.; Santos, L.O. Growth Stimulation and Synthesis of Lipids, Pigments and Antioxidants with Magnetic Fields in Chlorella kessleri Cultivations. Bioresource Technology 2017, 244, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, R.; Jin, W.; Xi, T.; Yang, Q.; Han, S.-F.; Abomohra, A.E.-F. Effect of Static Magnetic Field on the Oxygen Production of Scenedesmus obliquus Cultivated in Municipal Wastewater. Water Res. 2015, 86, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, Z.; Gao, Y.; et al. Bioeffects of Static Magnetic Fields on the Growth and Metabolites of C. pyrenoidosa and T. obliquus. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 351, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Chen, X.; Zhu, F.; et al. Magnetic Field Intervention on Growth of the Filamentous Microalgae Tribonema sp. in Starch Wastewater for Algal Biomass Production and Nutrients Removal: Influence of Ambient Temperature and Operational Strategy. Bioresource Technology 2020, 303, 122884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Ran, Y.; Zhai, S.; Xia, Y. Cold Atmospheric Plasma: A Promising and Safe Therapeutic Strategy for Atopic Dermatitis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 184, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U.S.; Deshmukh, R.R. Non-Thermal Technologies for Food Processing. Front. Nutr. 8, 657090. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-P.; Kuo, T.-C.; Wang, H.-T.; et al. Enhanced Bioethanol Production Using Atmospheric Cold Plasma-Assisted Detoxification of Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysate. Bioresource Technology 2020, 313, 123704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Gajula, V.P.; Mohapatra, S.; Singh, G.; Kar, S. Role of Cold Atmospheric Plasma in Microbial Inactivation and the Factors Affecting Its Efficacy. Health Sci. Rev. 2022, 4, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, I.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Kapusta, I.; Simeonov, V.; Stój, A.; Waśko, A.; Pawłat, J.; Polak-Berecka, M. The Impact of Cold Plasma on the Phenolic Composition and Biogenic Amine Content of Red Wine. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, I.; Simeonov, V.; Waśko, A.; Polak-Berecka, M. Comparison of the Effect of Cold Plasma with Conventional Preservation Methods on Red Wine Quality Using Chemometrics Analysis. Molecules 2022, 27, 7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Koubaa, M.; Roohinejad, S.; Juliano, P.; Alpas, H.; Inácio, R.S.; Saraiva, J.A.; Barba, F.J. Landmarks in the Historical Development of Twenty First Century Food Processing Technologies. Food Res. Int. 2017, 97, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabor, O.F.; Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; Obileke, K.; Anumudu, C.; Hart, A. A Cold Plasma Technology for Ensuring the Microbiological Safety and Quality of Foods. Food Eng. Rev. 2022, 14, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Mei, Y.; Hou, X.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Liao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Ge, L. Comparative Transcriptomic Insight into Orchestrating Mode of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Cold Plasma and Lactate in Synergistic Inactivation and Biofilm-Suppression of Pichia manshurica. Food Res. Int. 2024, 198, 115323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Ling, H.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Liang, S. Enhanced Expression of Alcohol Dehydrogenase I in Pichia pastoris Reduces the Content of Acetaldehyde in Wines. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-H.; Lv, X.; Pan, Y.; Sun, D.-W. Foodborne Bacterial Stress Responses to Exogenous Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Induced by Cold Plasma Treatments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, F.A.D.; Barboza, N.R.; Castro-Borges, W.; Guerra-Sá, R. Manganese Alters Expression of Proteins Involved in the Oxidative Stress of Meyerozyma guilliermondii. J. Proteomics 2019, 196, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elkaliny, N.E.; Darwish, O.A.; Ashraf, Y.; Ebrahim, R.A.; Das, S.P.; Yahya, G. Comprehensive Review for Aflatoxin Detoxification with Special Attention to Cold Plasma Treatment. Mycotoxin Res. 2025, 41, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarabbi, H.; Soltani, K.; Sangatash, M.M.; Yavarmanesh, M.; Shafafi Zenoozian, M. Reduction of Microbial Population of Fresh Vegetables (Carrot, White Radish) and Dried Fruits (Dried Fig, Dried Peach) Using Atmospheric Cold Plasma and Its Effect on Physicochemical Properties. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.; Barbeau, J.; Crevier, M.-C.; Pelletier, J.; Philip, N.; Saoudi, B. Plasma Sterilization. Methods and Mechanisms. Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, C.; Beier, O.; Horn, K.; Pfuch, A.; Tölke, T.; Schimanski, A. Antimicrobial Impact of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma on Medical Critical Yeasts and and Bacteria Cultures. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013, 27, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recek, N.; Zhou, R.; Teo, V.S.J.; Speight, R.E.; Mozetič, M.; Vesel, A.; Cvelbar, U.; Bazaka, K.; Ostrikov, K. Improved Fermentation Efficiency of S. cerevisiae by Changing Glycolytic Metabolic Pathways with Plasma Agitation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wang, P.; Guo, Y.; Dai, X.; Xiao, S.; Fang, Z.; Speight, R.; Thompson, R.; Cullen, P.; Ostrikov, K. Prussian Blue Analogue Nanoenzymes Mitigate Oxidative Stress and Boost Bio-Fermentation. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 19497–19505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, T.; Xiong, Y. A Novel Approach to Regulate Cell Membrane Permeability for ATP and NADH Formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Induced by Air Cold Plasma. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2017, 19, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Huang, Z.-L.; Li, G.; Zhao, H.-X.; Xing, X.-H.; Sun, W.-T.; Li, H.-P.; Gou, Z.-X.; Bao, C.-Y. Novel Mutation Breeding Method for Streptomyces avermitilis Using an Atmospheric Pressure Glow Discharge Plasma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-Y.; Xiu, Z.-L.; Li, S.; Hou, Y.-M.; Zhang, D.-J.; Ren, C.-S. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma as a Novel Approach for Improving 1,3-Propanediol Production in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, Q.; Dou, S.; Di, L.; Zhang, X. Parameter Optimization for Enhancement of Ethanol Yield by Atmospheric Pressure DBD-Treated Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2014, 16, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganisms | Treatment Parameters | Main Result | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Lactobacillus casei BT 1268, Lactobacillus bulgaricus FTCC 0411, Lactobacillus acidophilus BT 1088, Lactobacillus acidophilus FTCC 0291, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus FTDC 1311 | 2.5–7.5 kV/cm, 3–4.5 ms | PEF treatment enhanced cell membrane permeability, insuring more efficient transport of cholesterol from the fermentation medium into the cytoplasm | [28] | |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. Bulgaricus | 20 μs, 60 mL/min flow rate, 1 kV/cm, and PEF treatment temperature of 40.5°C. 3 μs is the positive square unipolar pulse width. |

When exposed to mild PEF conditions, Lb. acidophilus LA-K and Lb. bulgaricus LB-12 exhibited notably improved acid resistance, enhanced exponential phase growth, and increased protease activity relative to the untreated control. | [29] | ||

| Lactococcus cremoris | 200 pulses at 8 kV/cm for 1 second and for 4 h | The application of PEF resulted in a 32% increase in exopolysaccharide (EPS) yield with a single treatment for 1 second and a 94% increase with circular treatment for 4 h compared to the control | [30] | ||

| L. plantarum in MRS medium | E: 40–60 kV/cm, number of pulses: 100–600, Pulse width: 35 ns, f: 1–50 Hz, applied during the log growth phase of the bacteria |

The nsPEF treatment positively enhanced the metabolism of lactic acid bacteria. A 19% rise in L-lactic acid, a 6.8% increase in D-lactic acid, and a 15% increase in acetic acid were observed compared to the control. |

[32] | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Resonant frequency of 0.8 Hz, exposure time 60 min |

PEF inhibited the growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae, increased the sensitivity of bacteria to antibiotics targeting cell wall synthesis, protein function, β-lactamase activity and DNA replication. | [33] | ||

| Alicyclobacillus spp | 9.6 kV/cm, exposure time 20 min, 1000 Hz, 50% duty cycle | PEF reduced Alicyclobacillus spp. in apple juice by 1.89 to 4.76 log CFU/mL | [34] | ||

| Yeast and mold | Trichoderma reesei | 1.5 KV/cm | Cellulase activity and secretion were increased by increasing membrane permeability. | [41] | |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus IMB3 | 0.625–3.750 kV/cm 10 ms | Ethanol production from cellulose was enhanced by 40% through the application of PEF, ethanol production was boosted by an increased Electric Field, although the enhancement was not as significant as when using a specific intensity of 0.625 kV/cm | [42] | ||

| S. cerevisiae in YEPG medium | 0.5-1.5 kV/cm, bipolar square pulses of 20 μs, total length of pulse: 8 ms | Cell growth doubled with a field strength of 0.85 kV/cm. | [35] | ||

|

Aspergillus niger in Basal Medium |

0.57–2.85 kV/cm 1–20 ms pulse duration 0.1–10 Hz frequency |

The output of the citric acid synthesis process remained constant over a range of pulse durations from 1 to 20 ms. With an electric field strength of 2.854 kV/cm, the rose had the strongest electric field. the peak value was at a frequency of 1 Hz, which is 1.4 times higher than the control. |

[39] | ||

| S. cerevisiae suspension in water | 0.1 and 6 kV/cm Monopolar pulses 1000 pulses, 100 μs pulse duration 100 ms pulse repetition time 18 μs/cm conductivity |

PEF enhanced the efficiency of the fermentation process and promoted greater sugar utilization. Following fermentation, samples treated with PEF showed a 30% greater mass reduction compared to untreated ones, which required an additional 20 hours to reach a similar level of reduction. | [36] | ||

| S. cerevisiae | Optimized parameters 3 kV/cm, 10 μs pulse width, 1 Hz, Total exposure time 10 min |

PEF boosted the accumulation of selenium and zinc within yeast cells. | [37] | ||

| Hanseniaspora sp. Yeast in YPD medium | Intensity in the range 0.072–0.285 kV/cm during the fermentation (Lag, exponential, and log phases) |

The yeast Hanseniaspora sp. is stimulated by moderate PEF, which shortens the fermentation time and increased biomass production. When 285 V/cm was administered during the Lag and early exponential stage as well as the Log phase, the growth rate of the yeast reached its peak. | [40] | ||

| Microalgae | Arthrospira platensis | E: 10.5–19.97 kV/cm, number of pulses: 1.83–15.88, Pulse width: 25–100 ns, f: 3–20 Hz, treatment time: 0.61 s, Energy input: 217–507 J/Kg |

The highest biomass output was obtained with the longest pulse width of 100 ns. Through their effects on intracellular and plasma membrane dynamics, nsPEF treatments stimulate cell growth. | [43] | |

| Arthrospira platensis | pulses of 100 ns, energy input of 256 J/kg | The exponential phase (36h) was correlated with the rising influence of biomass growth | [44] | ||

| Fermented product | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Kombucha analogues | Desactivation of acetic acid bacteria within kombucha consortium | [46] |

| Wine | Enhanced hue saturation, anthocyanins and overall phenolic content elevation, Improved extraction of bioactive components, hightened flavonols and phenolics compounds, shortened fermentation duration, substitute method for hatting fermentation(as opposed to employing SO2) |

[48,49,50,51,52] |

| fermented pomegranate beverage | Reduction of Brettanomyces ssp microbial load in the PEF-treated beverages compared to thermally pasteurized equivalents. | [45] |

| Natural drinkable yogurt | Low fermentation time (42 min) | [53] |

| Microorganism | Plasma type and conditions | Obtained plasma effect | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

A high-frequency (1.7 MHz, 2–6 kV) plasma jet, Argon gas at 5 standard liters per minute, 65 W of electric power, Distance between samples and the jet nozzle 7 mm, Treatment duration (3 or 10 min) |

Faster growth of treated yeast, Improved production of secondary metabolites (ethanol, acetic acid, and glycerol) | The membrane permeability was improved by ROS and UV, Modulation of metabolic pathways in yeast cells, Increased hexokinase 2, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, Stimulation of glycolytic flux by NAD+ regeneration and ethanol production | [102] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae + Prussian blue analogues (PBAs) nanoparticles (NPs) | A high-frequency (1.7 MHz, 2–6 kV) plasma jet, Argon gas at 5 standard liters per minute, Distance between the jet nozzle and yeast colonies( 7 mm) | Incerease of cells absorption nad ethanol production | Enhanced cell permeability. Moderate plasma agitation induces enhancing cells' stress tolerance during fermentation, speeding nutrient uptake like glucose, and boosting enzyme activity in metabolic pathways. | [103] |

|

Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

Atmospheric DBD plasma 29V power supply 0.65A power current 3mm discharge gap between upper electrode and cell sample surface Exposure times: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 min | Modification of cofactor metabolism (ATP and NADH). Plasma membrane alteration Increased cytosolic Ca2+ in plasma-treated cells enhances microbial activity | The reactive species of plasma affect cell membrane potential and activate Ca2+ channels, leading to increased cytoplasmic calcium levels. Calcium supplementation boosts ATPase activity for proton motive force. Decreased ATP levels upregulate glycolytic enzymes, increasing NADH. Elevated NADH enhances ADH activity, promoting ethanol production. | [104] |

|

Streptomyces avermitilis |

Plasma jet at atmospheric pressure, feed gas (pure helium ), RF input power: 120 W, The plasma torch nozzle outlet and the sample plate were separated by 2 mm, the plasma jet temperature was <40°C | isignificant total (over 30%) and positive (approximately 21%) mutation rates, yielding a genetically stable strain G1-1 with high avermectin B1a productivity, thereby improving avermectin fermentation efficiency | The plasma treatment of the spores probably resulted in the metabolic network of the G1-1 mutant being completely altered or to develop several genetic mutation sites being created. | [105] |

|

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

Atmospheric DBD plasma in air at atmospheric pressure, 24kV, 20kHz, Discharge gap: 3mm between upper electrode and sample suspension surface | Kp-M2 produced 1,3-propanediol at higher concentrations than wild type in batch (19.9 vs 16.2 g/L) and fed-batch (76.7 vs 49.2 g/L) ---fermentations. | the enhanced production of 1,3-PD seen in Kp-M2 could be viewed as a mutation. | [106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).