Teaching Points

When the A-TT is readily available, it can shift 500 cc of blood from each leg to the core in less than 20 seconds and block its re-entry.

The prompt auto-transfusion of the patient’s own fresh blood with intact clotting factors and oxygen carrying capacity increases core blood volume and restores blood pressure and myometrial perfusion.

Reversal of shock restores uterine tone and, together with Pitocin, help uterine smooth muscle to contract and expel the placenta, thereby resolving the postpartum haemorrhage.

2. Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) continues to be the leading life-threatening complication of labour and delivery [

1,

2,

3]. In developing countries 27% of pregnancy-related deaths (PRD) were due to PPH [

2] and in the US 8.8% of PRD were due to PPH [

3]. Access to advanced healthcare in the US is clearly the most important reason for this disparity. However, even within the US there are significant variations among geographies and ethnic populations with many deliveries taking place in less-well equipped community hospitals with lesser availability of obstetric experts, blood banks and are managed by family practitioners.

Over 70% of all PPH are caused by atony of the uterine muscle for a variety of aetiologies [

1]. Delayed delivery of the placenta or retention of a portion of the placenta can retard uterine contraction which facilitates bleeding from the villi. Uterine blood supply at the very end of pregnancy is as high as 600 cc per minute and bleeding can be massive. This can quickly lead to loss of 25% or more of the patient’s blood volume and development of haemorrhagic shock. The shock index (SI = Heart rate/systolic blood pressure) is widely used to assess the severity of haemorrhagic patients [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] and an SI value greater than 0.9 is usually taken as indicating shock. In the case described herewith, a PPH patient developed shock that was reversed by applying a novel auto-transfusion tourniquet (A-TT) device that quickly shifts about 500 cc of blood from each leg to the core; in this case one leg was enough. The relatively precipitous delivery took place in a rural California hospital where support facilities, e.g. obstetric specialist or blood bank, were not readily available. This case demonstrates how the use of simple and easy to use A-TT can reverse a situation that could have otherwise been fatal.

3. Case Presentation

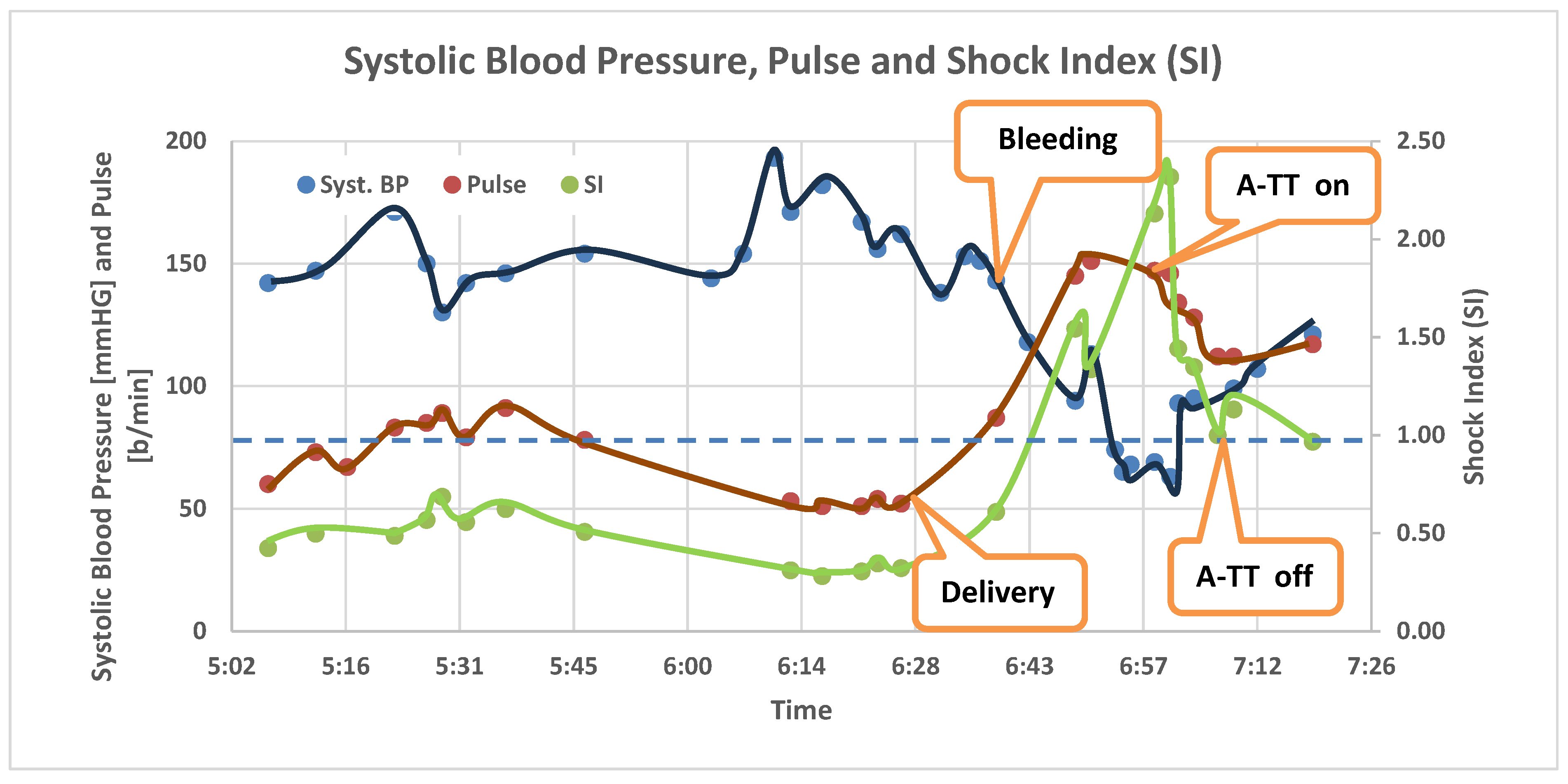

A 21 year old G1P0 patient presented to the Emergency Department (ED) of a rural Hospital in California High Desert in active labour. Rupture of membranes occurred at 22:45 and she arrived at the ED via ambulance in active labour and complete dilation at 5 am. Vital signs upon arrival were pulse of 60 bpm and blood pressure of 142/91 mmHg (SI=0.42) (see

Figure 1). A normal baby was born at 6:32 am, but the placenta was not immediately delivered. Blood pressure dropped sharply to 74/50 mmHg with heart rate of 145 bpm at 6:51 (SI=1.99) and further to 63/37 mmHg with heart rate of 147 bpm (SI = 2.3) at 7:01. Aggressive vaginal bleeding was noted and a second IV was started with Pitocin drip of 20mg/1000 cc. At this time the ED physician who was managing this delivery by default elected to place an auto-transfusion tourniquet (A-TT) on her leg. This device shifts the entire blood volume of the leg to the central circulation and blocks the return of the blood to the leg, whereby transfusing the patient with her own fresh blood. The application of the A-TT on a leg takes 10-20 seconds and approximately 500 cc are shifted from each leg. One minute after the A-TT application the pulse dropped to 134 and the BP increased to 93/58 mmHg (SI = 1.44); 5 minutes later the pulse was 112 bpm and BP was 112/71 mmHg (SI = 1.0). The blood pressure stabilized and remained above 100 mmHg systolic enabling the stepwise removal of the A-TT over a span of 10 minutes. At this point the uterus, which was atonic at the time of excessive bleeding, contracted, bleeding slowed, and the placenta was expelled. The volume of IV fluids with Pitocin was less than 500 cc at this time. Vital signs continued to be stable while awaiting blood, so no blood was given. The patient was airlifted with her healthy full-term baby to a Level 1 trauma centre and was discharged home the next day in good condition.

4. Discussion

Like with any severe haemorrhagic shock (SHS), prompt reversal of the deteriorating haemodynamic status of the PPH patient is critical for survival. In fact, basic research done in rodents in 1998 [

10] has shown an inverse linear relationship between blood flow to the uterus and uterine contractile activity. The authors concluded that “uterine smooth muscle is closely dependent upon its blood supply for maintaining both normal force production and metabolite levels. Consequently, even small decrements in flow may have deleterious functional effects”. This research emphasizes the criticality of restoring uterine blood supply in reversing uterine atony which is the natural and most effective way of stopping endometrial bleeding and expelling the placenta. The placenta delivery in this case was 23 minutes after delivery of the baby which is much longer than normal [

11] and is associated with a substantially increased incidence of PPH.

4.1. What is the Natural Course of Such Condition?

This is an obstetrical emergency. The uterus does not contract effectively until the placenta is delivered or removed. The open sinuses at the placental bed can bleed large amounts (1-2 litters) very rapidly if the uterus is atonic. Uterine contraction is the only effective physiological mechanism to stop the bleeding. This contraction is primarily by an intrinsic uterine mechanism that is not activated until the placenta is out. As such, treatment to support blood pressure with volume expansion is the first step with extrinsic Pitocin and Methergine being used to promote uterine contraction; blood and blood products in high rate via large bore venous catheters are often needed.

4.2. What Are the Physiological Compensatory Mechanisms that Help Reverse the Course?

Maternal blood volume increases during pregnancy by up to 50% at term. As such, even loss of 2 liters of blood can be tolerated. The drop in blood pressure can reduce the bleeding to a degree. The sympathetic control constricts peripheral vessels and cause extreme compensatory tachycardia as seen in this case. Finally, once the uterus contracts, it auto-transfuses between 500 to 1000 cc of blood from the uterus into the central circulation, (not much different from the action of the A-TT).

4.3. What Are the Complications?

If exsanguination continues with no effective uterine contraction, the arterial supply to the uterus should be ligated, or a hysterectomy performed, but DIC is the dire fatal complication that may develop rapidly and irreversibly.

Based on the above, we can conclude that the placement of the A-TT on one leg in this patient provided a time bridge until the removal of the placenta finally facilitated the effective contraction of the uterus. As such, there were no complications of the severe blood loss and temporary tissue hypoperfusion. The pause after one A-TT was placed and the gradual removal of the device while monitoring the hemodynamic status of the patient were according to the A-TT product instructions. There were no side effects, and the patient was discharged the following day.

The A-TT technology, in the form of the HemaClear(R) is safely used in orthopaedic surgery to create a bloodless surgical field with over 600,000 cases done in the US and over 2.1 million cases globally in the last 20+ years. The A-TT is also in use in emergency medicine as HemaShock(R) for cases of severe shock and in cardiac arrest. This case report suggests that additional research should be done on its use in obstetric severe shock to validate its usefulness in larger population studies.

5. Conclusion

This case report demonstrates how the use of a low-cost and non-invasive mechanical device can quickly restore blood pressure and tissue perfusion, thereby promptly interrupting the vicious cycle caused by PPH where shock leads to hypoperfusion of the uterus which results in atony, further bleeding and deeper shock etc. The setting of this case in a rural hospital with lack of advanced resources, would have possibly led to the demise of the patient.

Acknowledgments and conflicts

Martin Pallares Perez MD – no reported COIs. David H Tang MD – no reported COIs, Prof. Noam Gavriely is an officer and stakeholder of OHK Medical Device Inc. Drs. Tang and Perez oversaw the management of the patient. Both made significant contributions to the authoring of this report. Prof. Gavriely analysed the data, researched the literature, and wrote the first draft of this manuscript.

References

- Bienstock, J.L.; Eke, A.C.; Hueppchen, N.A. Postpartum haemorrhage. New Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 1635–1645, Postpartum Hemorrhage - PMC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; et al. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Trends in pregnancy-related mortality in the United States: 1987-2017 (graph). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm.

- A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Blood Loss and Clinical Signs—PMC.

- Vandromme, M.J.; Griffin, R.L.; Kerby, J.D.; McGwin, G.; Rue, L.W.; et al. Identifying risk for massive transfusion in the relatively normotensive patient: Utility of the prehospital shock index. The Journal of trauma 2011, 70, 384–388, discussion 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkhahn, R.; Gaeta, T.; Terry, D.; Bove, J.; Tloczkowski, J. Shock index in diagnosing early acute hypovolemia. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2005, 23, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.M.; Braxton, C.C.; Kling-Smith, M.; Mahnken, J.D.; Carlton, E.; et al. Utility of the shock index in predicting mortality in traumatically injured patients. The Journal of trauma 2009, 67, 1426–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, S.; Barnhart, K.; Takacs, P. Use of the shock index to predict ruptured ectopic pregnancies. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: The official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2011, 112, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madar, H.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Sentilhes, L.; TRAAP Study Group. Shock index as a predictor of postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal delivery: Secondary analysis of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2024, 131, 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe-McDouall, J.; Harrison, N.; Wray, S. The in vivo relationship between blood flow, contractions, pH and metabolites in the rat uterus-European Journal of Physiology. Pflügers Arch 1998, 435, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolova, A.I.; Stout, M.J.; Tuuli, M.G.; López, J.D.; Macones, G.A.; Cahill, A.G. Duration of the Third Stage of Labor and Risk of Postpartum Haemorrhage—Abstract—Europe PMC. Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2016, 127, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).