1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is the ability of microorganisms to withstand the effects of antimicrobial agents, which may exist inherently or be acquired. Microorganisms develop robust mechanisms over time via Darwinian selection to avoid being destroyed by toxic substances. This phenomenon can emerge when viruses, parasites, fungi, and bacteria undergo mutations in their genetic sequence, potentially resulting in resistance to one or multiple antimicrobial reagents [

1]. The treatment of multi-drug-resistant microorganisms, also known as “superbugs,” is a unique challenge actively working to be resolved by scientists [

2]. Bacteria with antimicrobial resistance have been identified in drinking water, soil, food products, the sea, and surprisingly even in Antarctica. The widespread use of antimicrobials across various sectors is the leading cause of antimicrobial resistance globally [

3].

Antimicrobial resistance poses a major risk to human health worldwide. A predictive statistical model found that 4.95 million deaths in 2019 were caused by antimicrobial resistance. The UK government funded a review estimating that 10 million deaths could result per year due to antibiotic resistance by 2050 [

2]. AMR is most frequently encountered by individuals in settings with limited access to resources [

4].

The economic burden of antimicrobial resistance is substantial. The majority of studies show that healthcare costs in patients with infections resistant to antibiotics are higher than the care for patients due to extended illness duration, prolonged length of hospital stay, additional diagnostic testing and need for more expensive medications [

5,

6]. According to the CDC, treating six of the most alarming antimicrobial resistance threats results in an accumulation of healthcare costs of over

$4.6 billion each year in the United States [

5,

7]. Antimicrobial resistance is projected to reduce global GDP by 1.1% [

8]. A study of 76 countries discovered that antibiotic consumption increased by 65% between the years 2000 and 2015. This increase may have been attributable to lower-income countries [

9]. Despite being underrecognized, socioeconomic factors contribute significantly to the spread of AMR. Several socioeconomic factors are believed to have a strong association with antimicrobial resistance, including but not limited to a lack of healthcare expenditure, along with poor infrastructure and governance [

10].

This exploration aims to thoroughly examine the extent to which socioeconomic factors play a role in the rapid proliferation of antimicrobial resistance worldwide. By exploring the intersection of economic, social, and healthcare-related elements, we will uncover how these factors influence the development of resistant strains. Through a comprehensive review of existing literature, we will assess the role of socioeconomic factors in exacerbating antimicrobial resistance, concentrating on the poorest regions.

2. Background

Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms are the two methods used by bacteria to develop the ability to withstand antibiotics. Intrinsic resistance is independent of antibiotic exposure and is found universally within certain bacterial genomes. It is a chromosomally mediated mechanism of resistance and is predictable based on an organism’s identity [

11]. The second mechanism of antimicrobial resistance is the acquired form. This entails the process by which a bacterium can become resistant to an antibiotic to which it was formerly susceptible. There is a likelihood that this newly acquired resistance was either via mutated genetic sequences or the uptake of foreign DNA plasmids from an organism which possessed an intrinsic resistance to the antimicrobial [

12]. There are two methods by which bacteria can acquire resistance to antimicrobials. The first is horizontal gene transfer, in which bacteria transfer DNA from one bacterium to another. The second is the rapid reproduction of bacteria, causing evolutionary shifts and natural selection over time to favor bacteria which have resistance [

13].

A multitude of factors including vaccination rates, variations in healthcare systems, along with risks associated with tourism, population densities, migration, and sanitation practices can spread resistance among humans [

14]. While antibiotic use was once considered the most critical point in the development of antimicrobial resistance, recent research highlights the significant influence of socioeconomic factors in its global proliferation.

2.1. Significance of AMR

Antimicrobial resistance is an emerging global health crisis as it jeopardizes the effectiveness of antimicrobial drugs and poses extreme challenges for healthcare systems. Despite past improvements in healthcare to enhance life expectancy, the capability of bacteria to resist the effects of antimicrobials has hindered the operations of global health systems. Resistant microorganisms in both the community and healthcare settings reduce survival rates, particularly in the case of infections acquired in the healthcare setting such as neonatal sepsis. As a result, drug-resistant infections limit the benefits of cancer treatments, surgeries, and transplants [

15].

AMR poses major hurdles for countries all around the globe to overcome. Immediate attention and action are necessary to hinder the growing spread of AMR. Both higher-income and low-middle income countries are susceptible to the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance worldwide. The increasing misuse of antimicrobial agents has caused a rapid acceleration of the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Formulating methods to mitigate the impacts of antimicrobial resistance will be crucial as time goes on. Data published in December 2019 has indicated that over 2.8 million individuals in the United States contract drug-resistant infections annually, leading to 35,000 deaths and an even greater number of hospitalizations [

16]. Healthcare-associated infections cost the US healthcare system between 28 and 45 billion dollars annually [

17].

2.2. Causes of AMR

Bacteria inhabiting soil, despite mostly being nonpathogenic, are frequently exposed to different chemicals and are gradually able to develop mechanisms to interact with other microbes to defend themselves against threats [

18]. Gene transfer is a key factor in the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Bacteria reproduce quickly, which gives them the ability to undergo evolutionary changes through spontaneous genetic mutations that can emerge in short periods of time. De-novo mutations, which are genetic variants appearing for the first time in a family tree, contribute significantly to the spread of antimicrobial resistance, often through plasmids that mediate the acquisition of resistance genes [

10]. AMR can proliferate due to uncontrollable horizontal gene transfer, a method in which circular plasmid DNA is shared between microbes, affecting the microbiota of microorganisms. Additionally, when resistant pathogenic microorganisms develop in one location, frequent travel and inadequate hygiene can upregulate their spread [

19]. In clinical settings, antimicrobial resistance can still be acquired when bacteria that were formerly susceptible to antibiotics develop resistance over time, complicating treatment options [

12].

Although antimicrobial agents have been an integral part of modern medicine for the last 80 years, AMR dates back much further in history. Interestingly, AMR existed well before antimicrobials were identified, synthesized and commercialized. Bacteria isolated from glacial waters estimated to be 2,000 years old have demonstrated resistance to Ampicillin [

20]. Sediment DNA dating back to 30,000 years ago has revealed a cluster of genes that encode for resistance to tetracycline, glycopeptide, and β-lactam antibiotics [

21].

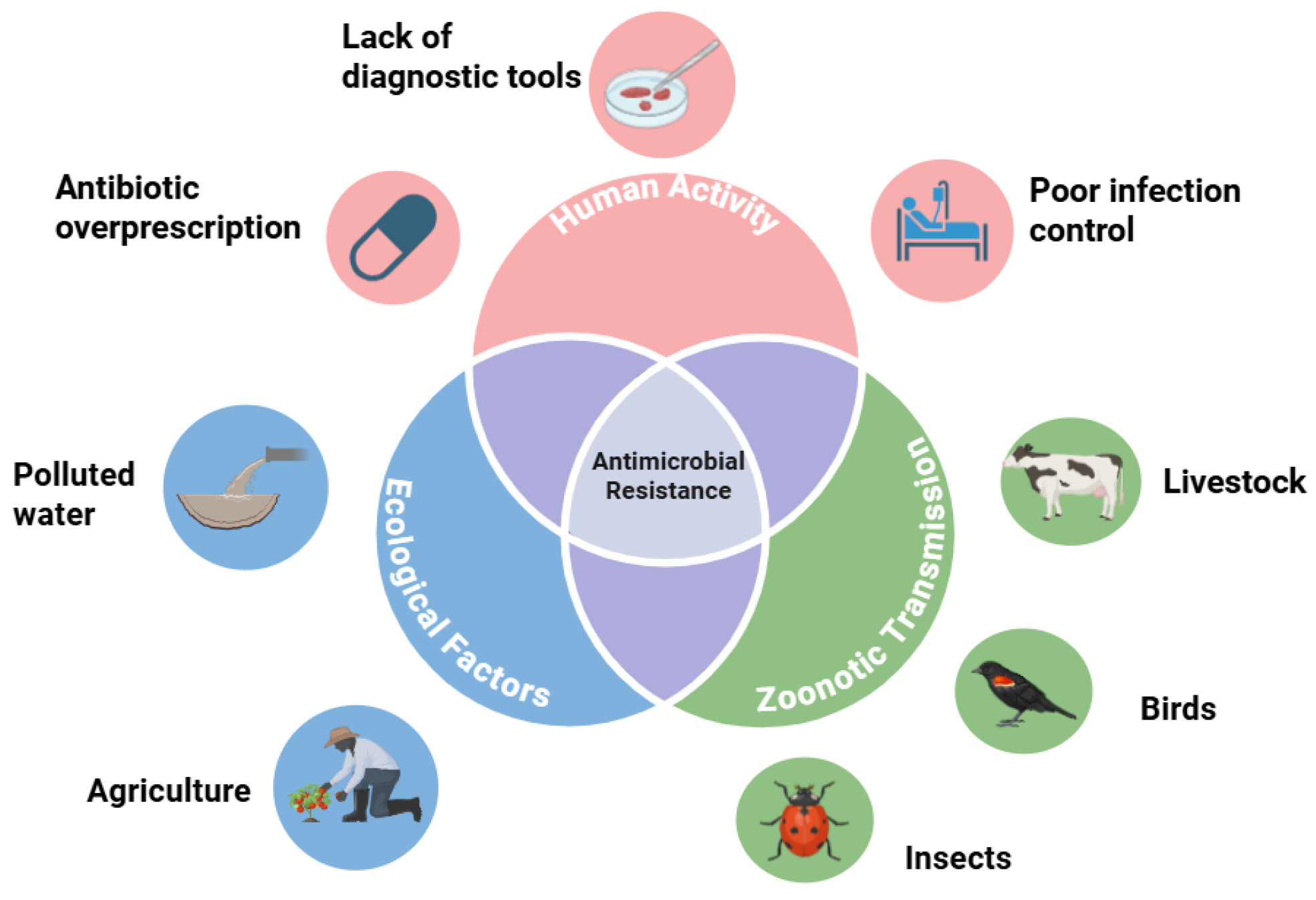

Figure 1.

Drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Countries of lower socioeconomic status struggle with human-mediated transmission of antimicrobial resistance, especially in settings of limited healthcare access and diagnostic capacities. Zoonosis to and from humans and other species upregulates the spread of AMR. Polluted water and substandard agricultural practices function as revervoirs for environmental dissemination. Figure created using BioRender.com.

Figure 1.

Drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Countries of lower socioeconomic status struggle with human-mediated transmission of antimicrobial resistance, especially in settings of limited healthcare access and diagnostic capacities. Zoonosis to and from humans and other species upregulates the spread of AMR. Polluted water and substandard agricultural practices function as revervoirs for environmental dissemination. Figure created using BioRender.com.

Antimicrobial resistance contagion, which is the spread of bacterial strains resistant to antimicrobial formulas, can spread via an assortment of vectors. The biological transmission of these antimicrobial-resistant strains can be traced to interactions between birds, insects, humans, water, and agriculture [

10]. Hence, combatting the threat of antimicrobial resistance requires a comprehensive One Health approach. The environment should be considered as having an underappreciated role in the proliferation of AMR. Yet, it is essential to understand that antibiotic consumption is increasing around the world.

2.3. Global Increase in Antibiotic Consumption

Surveillance data on national antibiotic use is crucial for tracking trends, comparing countries, establishing baselines for reduction efforts, and analyzing the link between use and resistance over time. Antibiotic consumption is exponentially increasing all around the world, especially in low and middle-income countries. A study projected that global antibiotic consumption will increase by 200% in 2030 compared to 2015 [

9]. It is estimated that approximately 50% of antimicrobials in healthcare are considered to be unnecessary [

22].

2.4. Demographic Susceptibility

The health burden caused by antimicrobial resistance is heavily related to the income of the country. Low and low-middle income countries tend to carry the largest AMR burden. Western Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia exhibit the greatest antimicrobial resistance, with a death rate due to AMR in 2019 of 27.3 per 100,000 and 21.5 per 100,000 respectively [

23]. This is significantly higher than in Western Europe, where the death rate attributed to AMR was 11.7 per 100,000. However, it should be noted that a multitude of socioeconomic factors result in the proliferation of AMR.

3. Socioeconomic Factors Contributing to Antimicrobial Resistance

3.1. Challenges in Low and Low-Middle Income Countries

There is significant evidence pointing to variations within higher and lower-income countries when it comes to residual active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) found in nature. The manufacturing activities of active pharmaceutical ingredients lead to residues via industrial waste discharge, which is prevalent in the riverine environment [

24]. While many higher-income countries can monitor their waste streams for capture and treatment, this practice is not as commonplace in low and low-middle income countries. In the Hyderabad region of India, water from lakes and areas downstream from treatment plants was found to have abnormally high levels of API residue when compared with levels commonly detected in North America and Europe [

6]. Additionally, it has been reported that the API market in Asia is expanding at twice the rate of G7 countries [

25]. While approximately 78% of the global population lives in Africa and Asia, only around 16% live in North America and Europe. This becomes a concern as the global pharmaceutical manufacturing base shifts to Asia and other low-income regions of the world.

Additionally, another factor contributing to the spread of AMR is poor sewer connectivity in LMICs. A lack of sewer connectivity in low-income countries leads to the release of a bulk of APIs into the environment, promoting a high degree of antimicrobial resistance. Even in urban areas, some lower-income countries in southern Asia have less than 30% sewer connectivity. Indonesia and Vietnam only have 2 and 4 percent sewer connectivity, respectively, largely as a result of their dependence on septic systems [

26]. In high-income countries, over 90% of the population is linked by sewers, highlighting how a lack of sewer connectivity in poorer regions can facilitate the growth of AMR.

In certain countries, the absence of wastewater treatment facilities results in contamination of surface and groundwater resources [

27]. A study on New Delhi’s sewer treatment plants found only 50% of capacity was utilized, and effluent frequently failed fecal coliform standards [

28]. According to a study published in 2009, only 22% of daily sewage was treated in 71 Indian cities, while 78% of the untreated sewage had to be discharged into large bodies of water [

29]. As a result, these large bodies of water become environmental reservoirs for antimicrobial resistance.

In many poorer regions of the world, most antimicrobials can be ordered without prescription, also referred to as self-medication [

30]. Additionally, overprescription due to perceived patient demand becomes an unresolved issue in lower-income countries. The pressure applied by pharmaceutical companies has unseen impacts on the prescription practices of medical providers [

31].

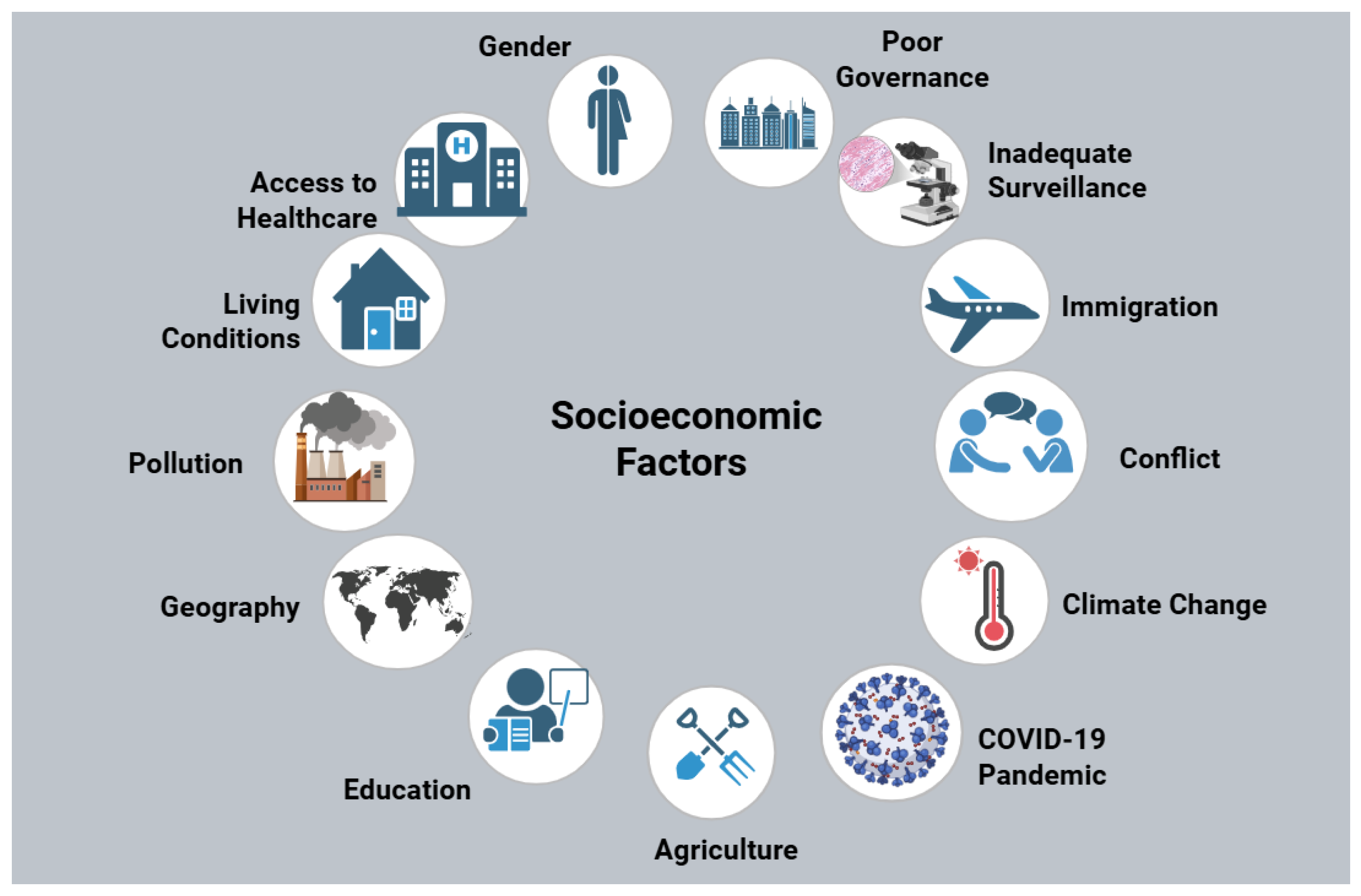

Figure 2.

Socioeconomic determinants contributing to AMR. The interplay of an assortment of socioeconomic factors is presented, including poor governance, inadequate surveillance, limited healthcare access, conflict, climate change, and education, resulting in the proliferation of drug-resistant microorganisms. The implementation of effective measures is necessary to mitigate entrenched socioeconomic disparities between countries worldwide. Figure created using BioRender.com.

Figure 2.

Socioeconomic determinants contributing to AMR. The interplay of an assortment of socioeconomic factors is presented, including poor governance, inadequate surveillance, limited healthcare access, conflict, climate change, and education, resulting in the proliferation of drug-resistant microorganisms. The implementation of effective measures is necessary to mitigate entrenched socioeconomic disparities between countries worldwide. Figure created using BioRender.com.

3.2. Living Conditions

Living conditions increase the risk of antimicrobial resistance. Poor water, sanitation, and hygiene practices can promote the risk of dissemination of infectious diseases and AMR genes [

32]. Household overcrowding is associated with increased antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance [

33,

34,

35]. In addition, those who are unhoused or incarcerated have greater susceptibility to AMR carriage [

36]. The insufficient living conditions of many LMICs contribute to greater AMR susceptibility.

3.3. Access to Healthcare

Limited access to healthcare is associated with an increase in self-medication with antibiotics [

37]. In resource-confined settings, a prolonged shortage of antibiotics may lead to AMR through selection of ineffective pharmaceuticals, suboptimal broad-spectrum antibiotics, and substandard antimicrobial practices [

38,

39]. Inadequate healthcare access proliferates AMR due to inappropriate antibiotic selection.

3.4. Gender

Several biological factors pertaining to women may expose them to greater risks of infections than their male counterparts. A study has shown that women have a 27% higher chance than men to receive an antimicrobial prescription [

40]. In the same study, it was found that women receive a 25% greater quantity of antibiotics compared to men. Some studies have also indicated that gender bias influences more antimicrobial prescribing to women than to men for the same illness [

41]. Understanding the intersection of gender disparity and socioeconomic factors is key, as women often face unique challenges in healthcare access, affordability, and cultural expectations.

3.5. Poor Governance and Limited Regulatory Frameworks

Lower standards of governance, evaluated via indicators like accountability, voice, rule of law, regulatory quality, and corruption control, have strong associations with increased antimicrobial usage and resistance rates [

10,

42]. A study which analyzed data from 43 countries in sub-Saharan Africa between 1996 and 2011 found that healthcare spending was significantly higher in countries that had better qualities of governance [

43]. Low and low-middle income countries may struggle to establish regulatory agencies that are willing to implement stricter standards to import, produce and distribute antimicrobials [

44]. Government bodies should encourage the public to raise awareness for improved policies, especially in LMICs which often exhibit unregulated antibiotic distribution and consumption.

3.6. Inadequate Surveillance Systems

Antimicrobial resistance surveillance is crucial in LMICs because of the prevalence of bacterial infections. However, LMICs generally lack the ability to maintain surveillance on the proliferation of antimicrobial resistance. Many LMICs do not possess adequate laboratories with the necessary resources to conduct comprehensive AMR testing. In addition, data collection methods tend to be inadequate, and standardized protocols are few and far between. Other limitations in low and low-middle income countries include an inability to practice standard laboratory techniques, insufficient use of microbiology services, and low representation [

45]. A shortage of skilled personnel prevents accurate and timely antimicrobial susceptibility testing [

46]. In many low and low-middle income countries, there is a lack of standardized reporting systems, which hinders the ability of researchers to gather data regarding the risks of antibiotic resistance [

4].

3.7. Immigration and Human Mobility

The movement of individuals across borders can elevate the spread of novel antimicrobial resistance genes internationally. Travelers are susceptible to acquiring resistant infections along their journeys, which can facilitate the spread of resistant strains into new countries [

47]. When studying causes of bacterial infections resistant to antibiotics, Chatterjee et al. discovered that travel abroad was responsible for 3% of AMR transmission in the studies examined [

48]. In a large meta-analysis, it was found that migration is associated with the development of antimicrobial resistance, as 25.4% of migrants examined carried or had AMR infections [

49]. Immigration resulting from poor socioeconomic conditions can therefore lead to mass movement of populations across borders, enhancing the ability of AMR infections to proliferate. Hence, immigration serves as a vector for AMR transmission.

3.8. Conflict

Conflict may hinder access to healthcare systems and the delivery of basic health services for those impacted. Specifically, conflict can damage infrastructure such as lab equipment in regions with already insufficient microbial testing facilities, preventing identification of drug-resistant pathogens [

50]. It may also cause disruptions in antibiotic stewardship practices, leading to unoptimized antibiotic choices and a decline in water, sanitation, and hygiene availability [

51]. Thus, prominent issues in LMICs only become exacerbated during conflict, especially in war-torn regions. As conflict is more likely to arise in countries of lower income, socioeconomic status intersects with the prevalence of AMR in these regions.

3.9. Climate Change

The World Health Organization has identified climate change as the most formidable health threat facing humanity, with 250,000 more deaths expected annually from 2030 to 2050 [

52]. Because of global warming, several microorganisms have crossed over to humans including

Salmonella, Vibrio cholerae and

Campylobacter. This is a result of increasing temperatures in water systems [

53]. There is growing evidence that climate change brings humans and animals closer together, increasing chance for zoonotic transmission of antimicrobial-resistant infections [

1]. In essence, the movement of animals due to climate has driven zoonotic infection rates of AMR. As a result, LMICs are burdened with mitigating climate change while simultaneously attempting to manage the resulting health effects with an already limited supply of resources.

3.10. COVID-19 Pandemic

Studies have found correlations between poverty and low-income households and an increased risk of COVID-19 [

54]. The COVID-19 pandemic has spread AMR due to elevated antibiotic usage and nosocomial drug-resistant infections [

55,

56]. On the contrary, the implementation of stricter regulations on travel worldwide and elective procedures in hospitals, along with increases in hand hygiene, may have reduced the spread of AMR in the short term. Nevertheless, in 2020, it is estimated that AMR led to a third as many deaths as COVID-19.

As nearly 70% of COVID-19 patients were given antimicrobials in outpatient or inpatient settings, this likely exacerbated AMR [

57,

58]. One particular instance of AMR emerging due to COVID-19 antibiotic use is chloroquine, an antimalarial drug; the frequent administration of this drug may encourage chloroquine resistance in non-

Plasmodium falciparum [

59].

Another aspect of inappropriate antibiotic prescription during the peak of the COVID-19 era may have been triggered by an overlap in symptomatology of COVID-19 and bacterial infections. A lack of adequate materials for testing can result in incorrect diagnoses of COVID-19 in LMICs, and subsequent prescription of antibiotic agents when they are unnecessary. Essentially, scarcity of resources in the healthcare system of LMICs upregulates the spread of AMR.

3.11. Agriculture

In many populated parts of the world, farming is associated with low socioeconomic status [

60]. Farmers are found to have disproportionately high rates of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections compared to the general population [

38,

61]. The use of antibiotics in agriculture is thought to have potentially exceeded antibiotic consumption by humans in 2010, when roughly 63,200 tons worth of antibiotic usage was found in livestock [

7]. Intensive agricultural practices have been shown to be drivers of antimicrobial resistance. More interestingly, conventionally farmed sites have been found to harbor more antimicrobial resistance genes than organically farmed sites. Agricultural chemicals and pollutants can inflict stress upon intensively farmed soils. These stressors may lead to cross-resistance in bacteria [

62,

63].

3.12. Education

Educational level has been proven to be a factor in terms of the proliferation of AMR. In a Japanese study, 6,982 participants were evaluated via a questionnaire, and it was determined that the strongest indicator of knowledge of antibiotics and AMR was educational level [

64]. Poor access to education has been linked to resistant

S. pneumoniae and

E. coli infections [

33]. Those with stronger education levels are able to better understand the risks of inappropriate antibiotic use and the emergence of AMR [

65]. However, there are studies refuting this claim. The authors of a meta-analysis claim that the misuse of antibiotics lacks a strong correlation to educational levels. This meta-analysis surprisingly found that individuals with higher education in Europe had 25% greater odds of antibiotic misuse [

66]. Hence, the connection between education and the optimal use of antibiotics is supported by significant evidence but still up in the air.

3.13. Geography

Non-prescription antibiotic use is well known to increase antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the community. In a large meta-analysis by Morgan et al., it was found that there was a clear connection between geographical location and non-prescription antibiotic use. This study found non-prescription antibiotic use to be 100% in Africa, 58% in Asia, and 3% in northern Europe [

67]. In a separate study, it was found that self-medication with antibiotics ranged from 19% to 82% in different Middle Eastern countries [

68]. Geographic location may be linked to socioeconomic status; the wealthiest regions tend to have the least nonprescription antibiotic use.

3.14. Pollution

Antibiotic resistance in bacteria can develop via mutations in the bacterial genome or by acquiring foreign DNA. Low quality infrastructure to manage human and animal waste streams can lead to an increase of residual antibiotics and fecal bacteria found in the environment [

30,

69]. China and India produce the most antibiotics but struggle to discard them properly, as ineffective waste management and excessive emission of antibiotics have been reported in both countries. A lack of resources in LMICs has exacerbated the uncontrolled deposition of antibiotic residues in nature [

70,

71]. Pollution in countries of all socioeconomic statuses can result in the prevalence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in marine habitats. Antibiotics and ARGs can be found in riverine runoff, wastewater treatment plants, sewage discharge, and aquaculture. Antibiotic spread into the environment can be attributed to environmental variables, such as heavy metals, organic pollutants, and nutrients. ARG dissemination can be affected by antibiotic residues, environmental factors, mobile genetic elements, and bacterial communities. A global proliferation of antibiotics and ARGs within marine environments poses an unseen threat to both marine and human life, not to mention the disruption they cause to microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles. Most antibiotics consumed by humans end up excreted in an unmetabolized form, especially in LMICs with limited wastewater processing facilities [

5]. It is crucial to garner public awareness to alter human behaviors to be able to limit disposal of unwanted antibiotics into natural habitats. In lower-income regions, there is a dire need for improved regulation of waste excreted into the environment which often contains unforeseen amounts of ARGs, enhancing AMR proliferation.

4. Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance is regarded as a worldwide threat to human health. The rise of antimicrobial resistance is a multifaceted global challenge influenced heavily by socioeconomic factors, particularly in LMICs. It presents a complex challenge for governments, healthcare systems, and medical professionals. Although the primary driver of AMR is consumption of antibiotics, socioeconomic factors play a largely unseen role in the proliferation of antimicrobial resistance [

72]. Key contributors include inadequate infrastructure, poor sanitation, and insufficient healthcare access, which promote the excessive and incorrect use of antibiotics. The environmental impact of pharmaceutical waste, especially from growing manufacturing bases in regions like Asia, further exacerbates the spread of AMR [

24]. Middle- and low-income communities are found to have higher rates of resistant bacterial colonization [

73]. The lack of regulatory frameworks, weak governance, poor laboratory practices, and ineffective surveillance systems hinder efforts to control antibiotic resistance in these regions, leading to an unchecked proliferation of resistant bacteria in the environment and the community.

Living conditions, access to healthcare, and educational disparities have a crucial role in shaping the global AMR landscape. Poor living conditions, overcrowding, and inadequate water and sanitation facilities in LMICs create breeding grounds for the spread of AMR genes [

33]. Limited healthcare access often drives self-medication, leading to inappropriate antibiotic use and furthering the development of resistant strains. Furthermore, gender inequalities and limited awareness regarding the appropriate use of antibiotics exacerbate the problem, as women are disproportionately prescribed antibiotics without medical necessity [

40]. Without targeted interventions to address these socioeconomic disparities, AMR will continue to present a formidable danger to global health.

In conclusion, socioeconomic factors significantly contribute to the proliferation of antimicrobial resistance in healthcare. Addressing AMR requires a holistic, coordinated approach that tackles the underlying socioeconomic drivers. Strengthening healthcare systems, improving water and sanitation infrastructure, and enforcing stricter regulations on antibiotic use are crucial steps toward mitigating the spread of resistance. Raising public awareness, promoting education on the responsible use of antibiotics, and implementing stronger surveillance systems in LMICs remain vital to combat the threat of AMR.

Author Contributions

Writing-original draft preparation, S.E.; writing-review and editing, S.E., A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Selim Eke would like to extend his appreciation to infectious disease expert Dr. Arnold Cua for editing and giving suggestions for the manuscript. He would like to express his appreciation for his father, Dr. Sancar Eke, in supporting the creation of the manuscript throughout the writing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Magnano San Lio, Roberta et al. “How Antimicrobial Resistance Is Linked to Climate Change: An Overview of Two Intertwined Global Challenges.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 20,3 1681. 17 Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Jim. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. May 2016.

- Holmes AH;Moore LS;Sundsfjord A;Steinbakk M;Regmi S;Karkey A;Guerin PJ;Piddock LJ; “Understanding the Mechanisms and Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance.” Lancet (London, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26603922/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):629-655. Epub 2022 Jan 19. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 1;400(10358):1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02653-2. PMID: 35065702; PMCID: PMC8841637. [CrossRef]

- “World Antimicrobial Awareness Week 2023.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, www.who.int/campaigns/world-amr-awareness-week/2023. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- “The Socioeconomic Drivers and Impacts of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): Implications for Policy and Research.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/the-socioeconomic-drivers-and-impacts-of-antimicrobial-resistance-(amr)-implications-for-policy-and-research. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- “Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future.” World Bank, World Bank Group, 2 May 2017, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/drug-resistant-infections-a-threat-to-our-economic-future.

- Angelis, Giulia de. (PDF) Burden of Antibiotic Resistant Gram Negative Bacterial ..., www.researchgate.net/publication/314173950_Burden_of_Antibiotic_Resistant_Gram_Negative_Bacterial_Infections_Evidence_and_Limits. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

- Klein EY;Van Boeckel TP;Martinez EM;Pant S;Gandra S;Levin SA;Goossens H;Laxminarayan R; “Global Increase and Geographic Convergence in Antibiotic Consumption between 2000 and 2015.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29581252/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Collignon P;Beggs JJ;Walsh TR;Gandra S;Laxminarayan R; “Anthropological and Socioeconomic Factors Contributing to Global Antimicrobial Resistance: A Univariate and Multivariable Analysis.” The Lancet. Planetary Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30177008/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Cox, G, and GD Wright. “Intrinsic Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms, Origins, Challenges and Solutions.” International Journal of Medical Microbiology : IJMM, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23499305/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Munita, J.M., and C.A. Arias. “Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance.” Microbiology Spectrum, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27227291/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Oz T;Guvenek A;Yildiz S;Karaboga E;Tamer YT;Mumcuyan N;Ozan VB;Senturk GH;Cokol M;Yeh P;Toprak E; “Strength of Selection Pressure Is an Important Parameter Contributing to the Complexity of Antibiotic Resistance Evolution.” Molecular Biology and Evolution, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24962091/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Turnidge, J, and K Christiansen. “Antibiotic Use and Resistance--Proving the Obvious.” Lancet (London, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15708081/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan R;Matsoso P;Pant S;Brower C;Røttingen JA;Klugman K;Davies S; “Access to Effective Antimicrobials: A Worldwide Challenge.” Lancet (London, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26603918/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- “2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Stone, Patricia W. “Economic Burden of Healthcare-Associated Infections: An American Perspective.” Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Oct. 2009, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2827870/. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L, and TR Zembower. “Antimicrobial Resistance.” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32891221/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Ashbolt NJ;Amézquita A;Backhaus T;Borriello P;Brandt KK;Collignon P;Coors A;Finley R;Gaze WH;Heberer T;Lawrence JR;Larsson DG;McEwen SA;Ryan JJ;Schönfeld J;Silley P;Snape JR;Van den Eede C;Topp E; “Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) for Environmental Development and Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance.” Environmental Health Perspectives, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23838256/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Dancer SJ, Shears P, Platt DJ. Isolation and characterization of coliforms from glacial ice and water in Canada’s High Arctic. J Appl Microbiol. 1997 May;82(5):597-609. PMID: 9172401. [CrossRef]

- D’Costa VM;King CE;Kalan L;Morar M;Sung WW;Schwarz C;Froese D;Zazula G;Calmels F;Debruyne R;Golding GB;Poinar HN;Wright GD; “Antibiotic Resistance Is Ancient.” Nature, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21881561/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/20705. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Ranjbar R, Alam M. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Evid Based Nurs. 2023 Jul 27:ebnurs-2022-103540. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37500506. [CrossRef]

- Fick J;Söderström H;Lindberg RH;Phan C;Tysklind M;Larsson DG; “Contamination of Surface, Ground, and Drinking Water from Pharmaceutical Production.” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19449981/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- A Rapid Assessment of SEPTAGE Management in Asia: Policies and Practices in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam, United States Agency for International Development, pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADS118.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

- Kookana RS, Drechsel P, Jamwal P, Vanderzalm J. Urbanisation and emerging economies: Issues and potential solutions for water and food security. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Aug 25;732:139057. Epub 2020 May 7. PMID: 32438167. [CrossRef]

- Rehman MS;Rashid N;Ashfaq M;Saif A;Ahmad N;Han JI; “Global Risk of Pharmaceutical Contamination from Highly Populated Developing Countries.” Chemosphere, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23535471/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Jamwal, P, et al. “Efficiency Evaluation of Sewage Treatment Plants with Different Technologies in Delhi (India).” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18575954/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S; Darbar S; Saha S; “Chapter 25 – Challenges in management of domestic wastewater for sustainable development.” Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research Volume 6, 2022, Pages 531-552, Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kookana, Rai S, et al. “Potential Ecological Footprints of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: An Examination of Risk Factors in Low-, Middle- and High-Income Countries.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 19 Nov. 2014, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4213596/.

- Radyowijati, A, and H Haak. “Improving Antibiotic Use in Low-Income Countries: An Overview of Evidence on Determinants.” Social Science & Medicine (1982), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12821020/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmeister ER;Harvey AP;Nadimpalli ML;Gallandat K;Ambelu A;Arnold BF;Brown J;Cumming O;Earl AM;Kang G;Kariuki S;Levy K;Pinto Jimenez CE;Swarthout JM;Trueba G;Tsukayama P;Worby CJ;Pickering AJ; “Evaluating the Relationship between Community Water and Sanitation Access and the Global Burden of Antibiotic Resistance: An Ecological Study.” The Lancet. Microbe, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37399829/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Alividza, Vivian, et al. “Investigating the Impact of Poverty on Colonization and Infection with Drug-Resistant Organisms in Humans: A Systematic Review.” Infectious Diseases of Poverty, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 17 Aug. 2018, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6097281/. [CrossRef]

- Bert, Fabrizio, et al. “Antibiotics Self Medication among Children: A Systematic Review.” Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 9 Nov. 2022, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9687075/. [CrossRef]

- Coope, Caroline, et al. “Identifying Key Influences on Antibiotic Use in China: A Systematic Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis.” BMJ Open, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 25 Mar. 2022, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8961142/. [CrossRef]

- Mitevska, E, et al. “The Prevalence, Risk, and Management of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Diverse Populations across Canada: A Systematic Review.” Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33805913/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Sulis, G, and S Gandra. “Access to Antibiotics: Not a Problem in Some Lmics.” The Lancet. Global Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33713631/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, A, et al. “Global Contributors to Antibiotic Resistance.” Journal of Global Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30814834/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Iskandar K;Molinier L;Hallit S;Sartelli M;Catena F;Coccolini F;Hardcastle TC;Roques C;Salameh P; “Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Transmissionin Low- and Middle-Income Countriesfrom a ‘One Health’ Perspective-A Review.” Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32630353/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Schröder W;Sommer H;Gladstone BP;Foschi F;Hellman J;Evengard B;Tacconelli E; “Gender Differences in Antibiotic Prescribing in the Community: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27040304/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Eggermont D;Smit MAM;Kwestroo GA;Verheij RA;Hek K;Kunst AE; “The Influence of Gender Concordance between General Practitioner and Patient on Antibiotic Prescribing for Sore Throat Symptoms: A Retrospective Study.” BMC Family Practice, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30447685/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Maugeri, Andrea, et al. “Socio-Economic, Governance and Health Indicators Shaping Antimicrobial Resistance: An Ecological Analysis of 30 European Countries.” Globalization and Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 24 Feb. 2023, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9951828/. [CrossRef]

- Makuta, I, and B O’Hare. “Quality of Governance, Public Spending on Health and Health Status in Sub Saharan Africa: A Panel Data Regression Analysis.” BMC Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26390867/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Iwu, CD, et al. “The Incidence of Antibiotic Resistance within and beyond the Agricultural Ecosystem: A Concern for Public Health.” MicrobiologyOpen, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32710495/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gandra S;Alvarez-Uria G;Turner P;Joshi J;Limmathurotsakul D;van Doorn HR; “Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Progress and Challenges in Eight South Asian and Southeast Asian Countries.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32522747/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Hoque, R, et al. Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance in Bangladesh: A ..., www.researchgate.net/publication/338845321_Tackling_antimicrobial_resistance_in_Bangladesh_A_scoping_review_of_policy_and_practice_in_human_animal_and_environment_sectors. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

- Wuerz, TC, et al. “Acquisition of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) Carriage after Exposure to Systemic Antimicrobials during Travel: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32755674/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee A;Modarai M;Naylor NR;Boyd SE;Atun R;Barlow J;Holmes AH;Johnson A;Robotham JV; “Quantifying Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance in Humans: A Systematic Review.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30172580/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Nellums LB;Thompson H;Holmes A;Castro-Sánchez E;Otter JA;Norredam M;Friedland JS;Hargreaves S; “Antimicrobial Resistance among Migrants in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29779917/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Pallett SJC;Boyd SE;O’Shea MK;Martin J;Jenkins DR;Hutley EJ; “The Contribution of Human Conflict to the Development of Antimicrobial Resistance.” Communications Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37880348/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Petrosillo, N, et al. “Ukraine War and Antimicrobial Resistance.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37084755/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “2021 Who Health and Climate Change Survey Report.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038509. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Omazic, Anna, et al. “Identifying Climate-Sensitive Infectious Diseases in Animals and Humans in Northern Regions.” Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 14 Nov. 2019, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6854619/. [CrossRef]

- Khanijahani A;Iezadi S;Gholipour K;Azami-Aghdash S;Naghibi D; “A Systematic Review of Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Covid-19.” International Journal for Equity in Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34819081/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Ukuhor, Hyacinth O. “The Interrelationships between Antimicrobial Resistance, Covid-19, Past, and Future Pandemics.” Journal of Infection and Public Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33341485/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Pitchforth, Emma, et al. “Global Action on Antimicrobial Resistance: Lessons from the History of Climate Change and Tobacco Control Policy.” Mendeley, 1 Jan. 1970, www.mendeley.com/catalogue/9326fea7-385d-363e-8ba6-3b45d705834b/. [CrossRef]

- Langford BJ;So M;Raybardhan S;Leung V;Soucy JR;Westwood D;Daneman N;MacFadden DR; “Antibiotic Prescribing in Patients with Covid-19: Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection : The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33418017/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

-

Isaric, isaric.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ISARIC-Clinical-Data-Report-20.11.2020.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

- Wootton JC, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, Magill AJ, Su XZ. Genetic diversity and chloroquine selective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002 Jul 18;418(6895):320-3. PMID: 12124623. [CrossRef]

- Emran SA;Krupnik TJ;Aravindakshan S;Kumar V;Pittelkow CM; “Factors Contributing to Farm-Level Productivity and Household Income Generation in Coastal Bangladesh’s Rice-Based Farming Systems.” PloS One, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34506515/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Chen, C-J, and Y-C Huang. “New Epidemiology of Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in Asia.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection : The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24888414/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Kaviani Rad, Abdullah, et al. “An Overview of Antibiotic Resistance and Abiotic Stresses Affecting Antimicrobial Resistance in Agricultural Soils.” MDPI, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 12 Apr. 2022, www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/8/4666.

- Bassitta R;Nottensteiner A;Bauer J;Straubinger RK;Hölzel CS; “Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes via Pig Manure from Organic and Conventional Farms in the Presence or Absence of Antibiotic Use.” Journal of Applied Microbiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35835564/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Tsuzuki S;Fujitsuka N;Horiuchi K;Ijichi S;Gu Y;Fujitomo Y;Takahashi R;Ohmagari N; “Factors Associated with Sufficient Knowledge of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Japanese General Population.” Scientific Reports, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32103110/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Anderson, Michael. “Challenges to Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance.” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, www.cambridge.org/core/books/challenges-to-tackling-antimicrobial-resistance/7A666C209981B53263C4B59C83A719E9. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Mallah, Narmeen, et al. “Education Level and Misuse of Antibiotics in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis.” Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 3 Feb. 2022, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8815169/. [CrossRef]

- Morgan DJ;Okeke IN;Laxminarayan R;Perencevich EN;Weisenberg S; “Non-Prescription Antimicrobial Use Worldwide: A Systematic Review.” The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21659004/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Alhomoud F;Aljamea Z;Almahasnah R;Alkhalifah K;Basalelah L;Alhomoud FK; “Self-Medication and Self-Prescription with Antibiotics in the Middle East-Do They Really Happen? A Systematic Review of the Prevalence, Possible Reasons, and Outcomes.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28111172/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Ahammad ZS;Sreekrishnan TR;Hands CL;Knapp CW;Graham DW; “Increased Waterborne BLANDM-1 Resistance Gene Abundances Associated with Seasonal Human Pilgrimages to the Upper Ganges River.” Environmental Science & Technology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24521347/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Larsson, DG Joakim. “Pollution from Drug Manufacturing: Review and Perspectives.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25405961/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bielen A;Šimatović A;Kosić-Vukšić J;Senta I;Ahel M;Babić S;Jurina T;González Plaza JJ;Milaković M;Udiković-Kolić N; “Negative Environmental Impacts of Antibiotic-Contaminated Effluents from Pharmaceutical Industries.” Water Research, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28923406/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Fridkin SK;Edwards JR;Courval JM;Hill H;Tenover FC;Lawton R;Gaynes RP;McGowan JE; ; “The Effect of Vancomycin and Third-Generation Cephalosporins on Prevalence of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in 126 U.S. Adult Intensive Care Units.” Annals of Internal Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11487484/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

- Neves, Felipe Piedade Gonçalves, et al. “Differences in Gram-Positive Bacterial Colonization and Antimicrobial Resistance among Children in a High Income Inequality Setting.” BMC Infectious Diseases, 15 June 2020, escholarship.org/uc/item/1644m60p. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).