Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Factors in ASD

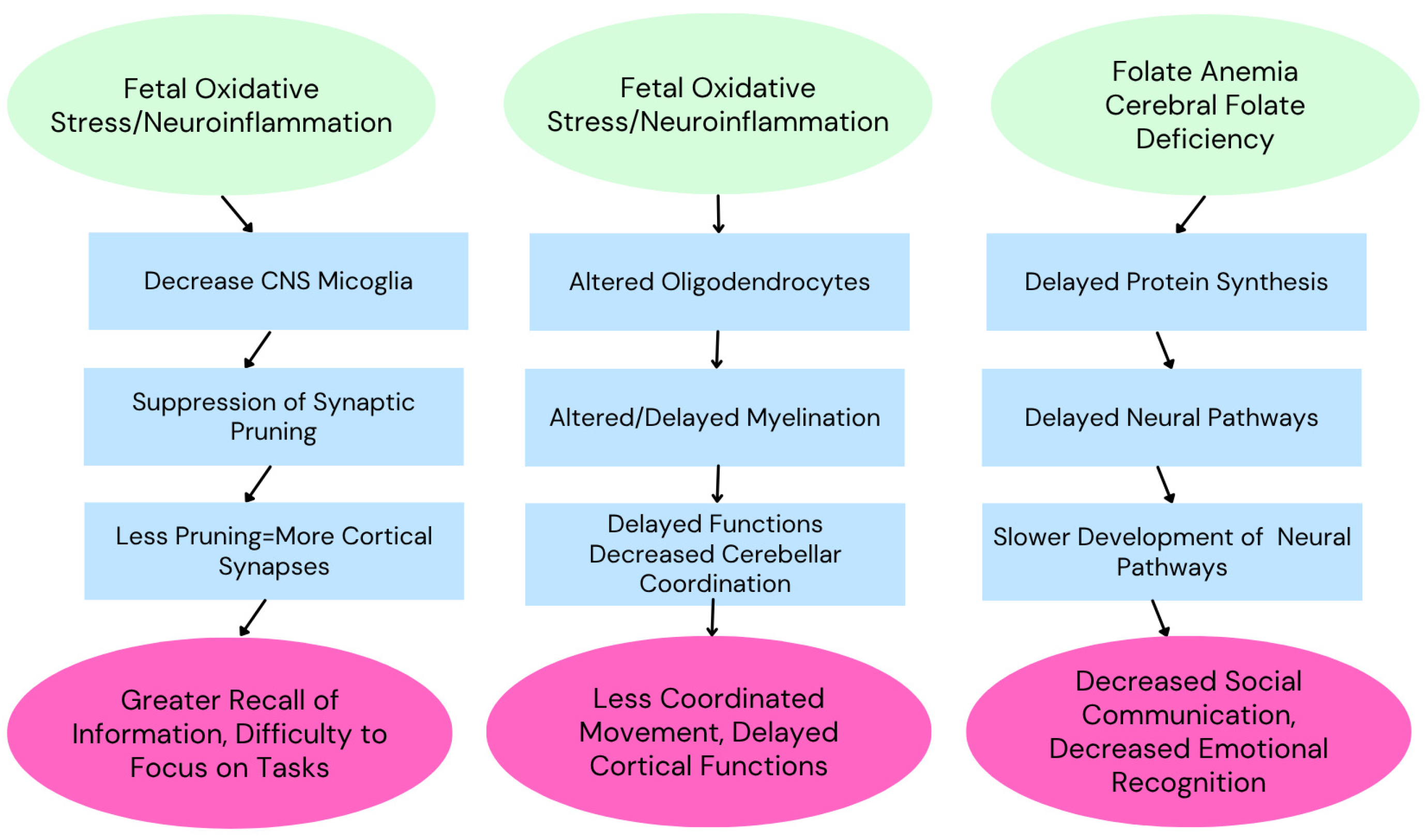

2.1. Cerebral Folate Deficiency

2.1.1. Folate Metabolism and Brain Development

2.1.2. Genetic Variants Impairing Folate Transport

2.1.3. Folate Receptor Alpha Autoantibodies (FRAAs)

2.1.4. Therapeutic Interventions

2.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

2.3. Synapse and Signaling Genes

2.4. Regulation, Cell Growth and Plasticity Genes

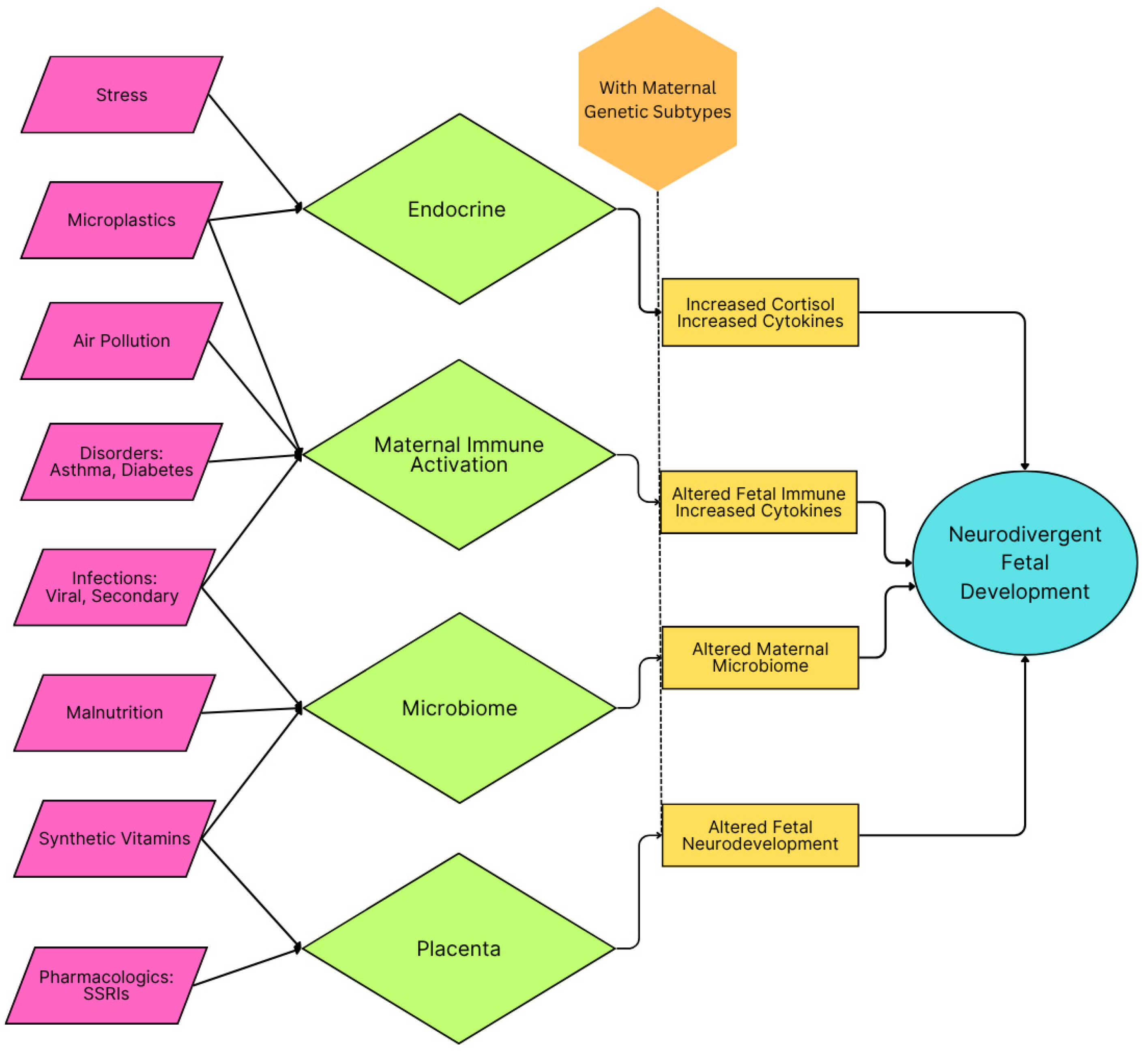

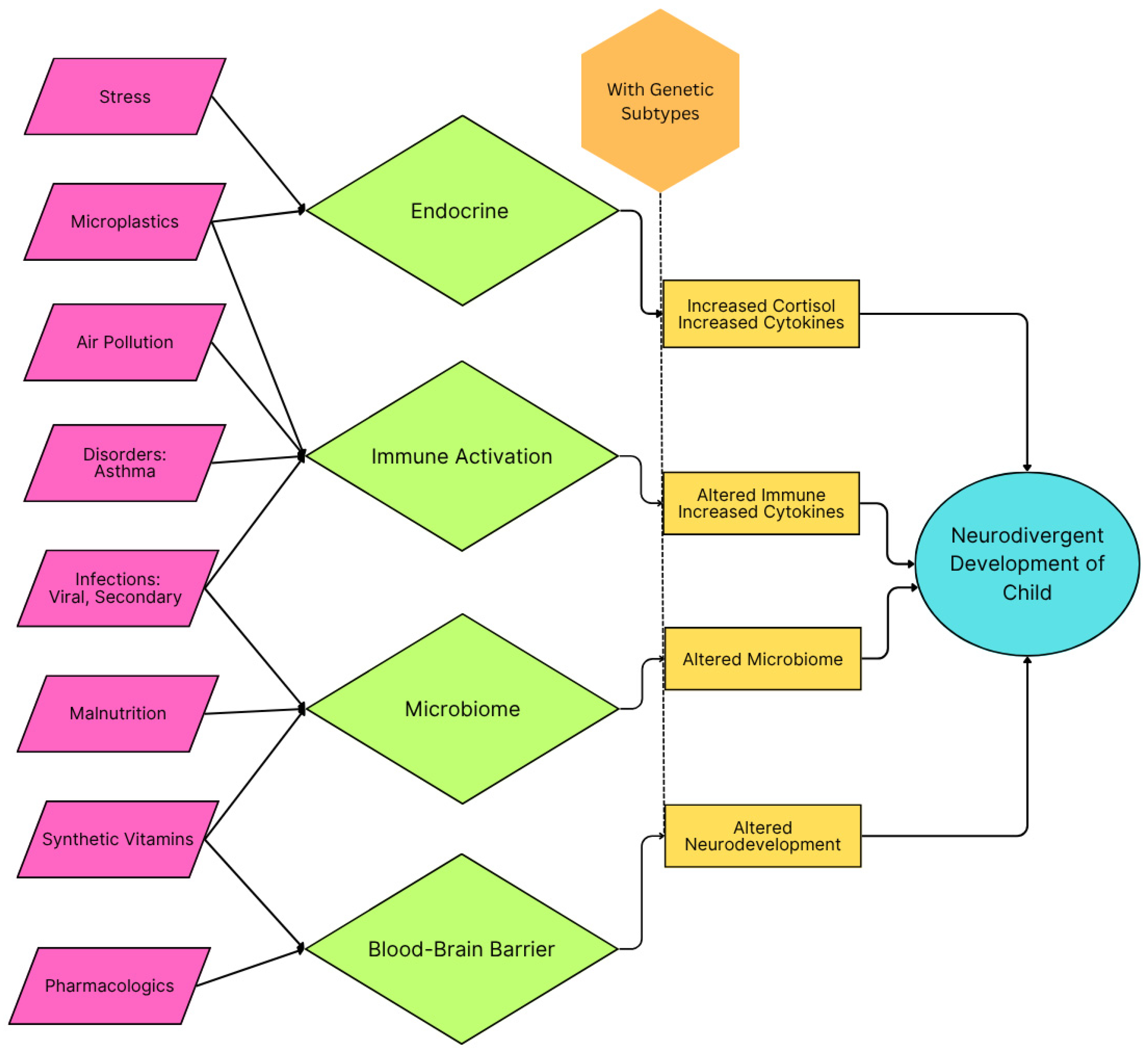

3. Inflammation During Critical Developmental Periods and ASD Risk

3.1. The Developing Brain and Vulnerability to Inflammation

3.2. Categories of Inflammation

3.2.1. Viral Infections

3.2.2. Air Pollution & Maternal Asthma

3.2.3. Maternal Immune Activation

3.2.4. Microplastics

3.2.5. Malnutrition

3.2.6. Emotional Stress

3.2.7. Pharmaceuticals

3.2.8. Maternal Disorders, Diabetes

3.2.9. Synthetic Vitamins

3.2.10. Vaccines

3.2.11. Microbiome and Metabolic Disorders

3.3. Mechanistic Insights

3.4. Therapeutic Interventions

4. Integrative Perspective: Gene-Environment Interactions in ASD

4.1. Synergistic Effects

4.2. Epigenetic Modifications

4.3. Implications for Prevention and Treatment

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| FRα | Folate Receptor alpha |

| RFC | Reduced Folate Carrier |

| FRAA | Folate Receptor Auto Antibody |

| CFD | Cerebral Folate Deficiency |

| MIA | Maternal Immune Activation |

| SSRI | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor |

References

- Shaw KA. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2025;74. [CrossRef]

- Gogate A, Kaur K, Khalil R, et al. The genetic landscape of autism spectrum disorder in an ancestrally diverse cohort. Npj Genomic Med. 2024;9(1):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Havdahl A, Niarchou M, Starnawska A, Uddin M, van der Merwe C, Warrier V. Genetic contributions to autism spectrum disorder. Psychol Med. 51(13):2260-2273. [CrossRef]

- Fu JM, Satterstrom FK, Peng M, et al. Rare coding variation provides insight into the genetic architecture and phenotypic context of autism. Nat Genet. 2022;54(9):1320-1331. [CrossRef]

- Khachadourian V, Mahjani B, Sandin S, et al. Comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder and their etiologies. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13(1):71. [CrossRef]

- Rolland T, Cliquet F, Anney RJL, et al. Phenotypic effects of genetic variants associated with autism. Nat Med. 2023;29(7):1671-1680. [CrossRef]

- Manoli DS, State MW. Autism Spectrum Disorder Genetics and the Search for Pathological Mechanisms. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(1):30-38. [CrossRef]

- Wan L, Yang G, Yan Z. Identification of a molecular network regulated by multiple ASD high risk genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2024;33(13):1176-1185. [CrossRef]

- Jourdon A, Wu F, Mariani J, et al. Modeling idiopathic autism in forebrain organoids reveals an imbalance of excitatory cortical neuron subtypes during early neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(9):1505-1515. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub G. Neurodevelopment of Autism: Critical Periods, Stress and Nutrition. Cells. 2024;13(23):1968. [CrossRef]

- Qiu S, Qiu Y, Li Y, Cong X. Genetics of autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):249. [CrossRef]

- Ramaekers VT, Sequeira JM, Blau N, Quadros EV. A milk-free diet downregulates folate receptor autoimmunity in cerebral folate deficiency syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(5):346-352. [CrossRef]

- Frye RE, Slattery J, Delhey L, et al. Folinic acid improves verbal communication in children with autism and language impairment: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(2):247-256. [CrossRef]

- Renard E, Leheup B, Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Oussalah A, Quadros EV, Guéant JL. Folinic acid improves the score of Autism in the EFFET placebo-controlled randomized trial. Biochimie. 2020;173:57-61. [CrossRef]

- Panda PK, Sharawat IK, Saha S, Gupta D, Palayullakandi A, Meena K. Efficacy of oral folinic acid supplementation in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183(11):4827-4835. [CrossRef]

- Soetedjo F, Kristijanto JA, Durry F. Folinic acid and autism spectrum disorder in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of two double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials. AcTion Aceh Nutr J. 2025;10:194. [CrossRef]

- Frye RE, McCarty PJ, Werner BA, Rose S, Scheck AC. Bioenergetic signatures of neurodevelopmental regression. Front Physiol. 2024;15:1306038. [CrossRef]

- Frye RE. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Unique Abnormalities and Targeted Treatments. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2020;35:100829. [CrossRef]

- Gevezova M, Ivanov Z, Pacheva I, et al. Bioenergetic and Inflammatory Alterations in Regressed and Non-Regressed Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(15):8211. [CrossRef]

- Scott O, Shi D, Andriashek D, Clark B, Goez HR. Clinical clues for autoimmunity and neuroinflammation in patients with autistic regression. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(9):947-951. [CrossRef]

- The Mystery of Regressive Autism—Mental Health. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.enotalone.com/article/mental-health/the-mystery-of-regressive-autism-r20878/.

- Betancur C, Buxbaum JD. SHANK3 haploinsufficiency: a “common” but underdiagnosed highly penetrant monogenic cause of autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459(7246):569-573. [CrossRef]

- Jamain S, Quach H, Betancur C, et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):27-29. [CrossRef]

- Sanders SJ, Campbell AJ, Cottrell JR, et al. Progress in Understanding and Treating SCN2A-Mediated Disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2018;41(7):442-456. [CrossRef]

- Trifonova EA, Mustafin ZS, Lashin SA, Kochetov AV. Abnormal mTOR Activity in Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric and MIA-Associated Autism Spectrum Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):967. [CrossRef]

- Curatolo P, Moavero R, Vries PJ de. Neurological and neuropsychiatric aspects of tuberous sclerosis complex. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(7):733-745. [CrossRef]

- Panwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, et al. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):1-25. [CrossRef]

- Bernier R, Golzio C, Xiong B, et al. Disruptive CHD8 Mutations Define a Subtype of Autism Early in Development. Cell. 2014;158(2):263-276. [CrossRef]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):185-188. [CrossRef]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X Syndrome: Loss of Local mRNA Regulation Alters Synaptic Development and Function. Neuron. 2008;60(2):201-214. [CrossRef]

- Yenkoyan K, Mkhitaryan M, Bjørklund G. Environmental Risk Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review. Curr Med Chem. 2024;31(17):2345-2360. [CrossRef]

- Usui N, Kobayashi H, Shimada S. Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5487. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Du X, Zhang X, et al. Research trends of inflammation in autism spectrum disorders: a bibliometric analysis. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1534660. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub G. Neurodevelopment of Autism: Critical Periods, Stress and Nutrition. Cells. 2024;13(23):1968. [CrossRef]

- Ellul P, Maruani A, Vantalon V, et al. Maternal immune activation during pregnancy is associated with more difficulties in socio-adaptive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):17687. [CrossRef]

- Carter M, Casey S, O’Keeffe GW, Gibson L, Gallagher L, Murray DM. Maternal Immune Activation and Interleukin 17A in the Pathogenesis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder and Why It Matters in the COVID-19 Era. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:823096. [CrossRef]

- Yin H, Wang Z, Liu J, et al. Dysregulation of immune and metabolism pathways in maternal immune activation induces an increased risk of autism spectrum disorders. Life Sci. 2023;324:121734. [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi RA, Al-Jabri BA, Alsulami MA, Sabbagh HJ. Prenatal maternal stress and the severity of autism spectrum disorder: A cross-sectional study. Dev Psychobiol. 2023;65(2):e22369. [CrossRef]

- Tioleco N, Silberman AE, Stratigos K, et al. Prenatal maternal infection and risk for autism in offspring: A meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2021;14(6):1296-1316. [CrossRef]

- Nudel R, Thompson WK, Børglum AD, et al. Maternal pregnancy-related infections and autism spectrum disorder—the genetic perspective. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Brynge M, Sjöqvist H, Gardner RM, Lee BK, Dalman C, Karlsson H. Maternal infection during pregnancy and likelihood of autism and intellectual disability in children in Sweden: a negative control and sibling comparison cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(10):782-791. [CrossRef]

- Duque-Cartagena T, Dalla MDB, Mundstock E, et al. Environmental pollutants as risk factors for autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2388. [CrossRef]

- Phiri YVA, Canty T, Nobles C, Ring AM, Nie J, Mendola P. Neonatal intensive care admissions and exposure to satellite-derived air pollutants in the United States, 2018. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):420. [CrossRef]

- Bragg MG, Gorski-Steiner I, Song A, et al. Prenatal air pollution and children’s autism traits score: Examination of joint associations with maternal intake of vitamin D, methyl donors, and polyunsaturated fatty acids using mixture methods. Environ Epidemiol Phila Pa. 2024;8(4):e316. [CrossRef]

- Kang N, Sargsyan S, Chough I, et al. Dysregulated metabolic pathways associated with air pollution exposure and the risk of autism: Evidence from epidemiological studies. Environ Pollut Barking Essex 1987. 2024;361:124729. [CrossRef]

- Amnuaylojaroen T, Parasin N, Saokaew S. Exploring the association between early-life air pollution exposure and autism spectrum disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2024;125:108582. [CrossRef]

- Ritz B, Liew Z, Yan Q, et al. Air pollution and autism in Denmark. Environ Epidemiol. 2018;2(4):e028. [CrossRef]

- Ojha SK, Amal H. Air pollution: an emerging risk factor for autism spectrum disorder. Brain Med. 2024;1(1):31-34. [CrossRef]

- Dutheil F, Comptour A, Morlon R, et al. Autism spectrum disorder and air pollution: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut Barking Essex 1987. 2021;278:116856. [CrossRef]

- Carter SA, Rahman MM, Lin JC, et al. In utero exposure to near-roadway air pollution and autism spectrum disorder in children. Environ Int. 2022;158:106898. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan E, Malmqvist E, Rittner R, Gustafsson P, Källén K, Oudin A. Exposure to local, source-specific ambient air pollution during pregnancy and autism in children: a cohort study from southern Sweden. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3848. [CrossRef]

- Autism likelihood in infants born to mothers with asthma is associated with blood inflammatory gene biomarkers in pregnancy—ScienceDirect. Accessed May 20, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666354624001236.

- Gong T, Lundholm C, Rejnö G, et al. Parental asthma and risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring: A population and family-based case-control study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2019;49(6):883-891. [CrossRef]

- Neural Regeneration Research. Accessed May 20, 2025. https://journals.lww.com/nrronline/fulltext/2025/04000/evidence_supporting_the_relationship_between.26.aspx.

- Liao J, Yan W, Zhang Y, et al. Associations of preconception air pollution exposure with growth trajectory in young children: A prospective cohort study. Environ Res. 2025;267:120665. [CrossRef]

- Gardner RM, Brynge M, Sjöqvist H, Dalman C, Karlsson H. Maternal Immune Activation and Autism in Offspring: What Is the Evidence for Causation? Biol Psychiatry. Published online November 2024:S0006322324017608. [CrossRef]

- Brynge M. Immune Dysregulation in Early Life and Risk of Autism. thesis. Karolinska Institutet; 2022. Accessed May 20, 2025. https://openarchive.ki.se/articles/thesis/Immune_dysregulation_in_early_life_and_risk_of_autism/26904367/1.

- McLellan J, Kim DHJ, Bruce M, Ramirez-Celis A, Van de Water J. Maternal Immune Dysregulation and Autism–Understanding the Role of Cytokines, Chemokines and Autoantibodies. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Agramonte M de los A, Noris García E, Fraga Guerra J, et al. Immune Dysregulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: What Do We Know about It? Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3033. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Kumar A, Kumar D, et al. Microplastics influencing aquatic environment and human health: A review of source, determination, distribution, removal, degradation, management strategy and future perspective. J Environ Manage. 2025;375:124249. [CrossRef]

- Thongkorn S, Kanlayaprasit S, Kasitipradit K, et al. Investigation of autism-related transcription factors underlying sex differences in the effects of bisphenol A on transcriptome profiles and synaptogenesis in the offspring hippocampus. Biol Sex Differ. 2023;14(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Parenti M, Schmidt RJ, Ozonoff S, et al. Maternal Serum and Placental Metabolomes in Association with Prenatal Phthalate Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in the MARBLES Cohort. Metabolites. 2022;12(9):829. [CrossRef]

- Parenti M, Slupsky CM. Disrupted Prenatal Metabolism May Explain the Etiology of Suboptimal Neurodevelopment: A Focus on Phthalates and Micronutrients and their Relationship to Autism Spectrum Disorder. Adv Nutr Bethesda Md. 2024;15(9):100279. [CrossRef]

- Symeonides C, Vacy K, Thomson S, et al. Male autism spectrum disorder is linked to brain aromatase disruption by prenatal BPA in multimodal investigations and 10HDA ameliorates the related mouse phenotype. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6367. [CrossRef]

- Stevens S, McPartland M, Bartosova Z, Skåland HS, Völker J, Wagner M. Plastic Food Packaging from Five Countries Contains Endocrine- and Metabolism-Disrupting Chemicals. Environ Sci Technol. 2024;58(11):4859-4871. [CrossRef]

- Su Z, Kong R, Huang C, et al. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics causes anxiety and depressive-like behavior and down-regulates EAAT2 expression in mice. Arch Toxicol. Published online February 28, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Pan D, Zhu Y, et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics chronic exposure cause zebrafish visual neurobehavior toxicity through TGFβ-crystallin axis. J Hazard Mater. 2025;492:138255. [CrossRef]

- Zaheer J, Kim H, Ko IO, et al. Pre/post-natal exposure to microplastic as a potential risk factor for autism spectrum disorder. Environ Int. 2022;161:107121. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Albornoz MC, García-Guáqueta DP, Velez-van-Meerbeke A, Talero-Gutiérrez C. Maternal Nutrition and Neurodevelopment: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3530. [CrossRef]

- Siracusano M, Riccioni A, Abate R, Benvenuto A, Curatolo P, Mazzone L. Vitamin D Deficiency and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(21):2460-2474. [CrossRef]

- Zwierz M, Suprunowicz M, Mrozek K, et al. Vitamin B12 and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients. 2025;17(7):1220. [CrossRef]

- Pancheva R, Toneva A, Bocheva Y, Georgieva M, Koleva K, Yankov I. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in children with cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorder: a comparative pilot study. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2024;66(6):787-794. [CrossRef]

- Stefanyshyn V, Stetsyuk R, Hrebeniuk O, et al. Analysis of the Association Between the SLC19A1 Genetic Variant (rs1051266) and Autism Spectrum Disorders, Cerebral Folate Deficiency, and Clinical and Laboratory Parameters. J Mol Neurosci MN. 2025;75(2):42. [CrossRef]

- Gusso D, Prauchner GRK, Rieder AS, Wyse ATS. Biological Pathways Associated with Vitamins in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurotox Res. 2023;41(6):730-740. [CrossRef]

- Kacimi FE, Ed-Day S, Didou L, et al. Narrative Review: The Effect of Vitamin A Deficiency on Gut Microbiota and Their Link with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Diet Suppl. 2024;21(1):116-134. [CrossRef]

- Kacimi FE, Didou L, Ed Day S, et al. Gut microbiota, vitamin A deficiency and autism spectrum disorder: an interconnected trio—a systematic review. Nutr Neurosci. 2025;28(4):492-502. [CrossRef]

- Savino R, Medoro A, Ali S, Scapagnini G, Maes M, Davinelli S. The Emerging Role of Flavonoids in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3520. [CrossRef]

- Schimansky S, Jasim H, Pope L, et al. Nutritional blindness from avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder—recommendations for the early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of children at risk from restrictive eating. Arch Dis Child. 2024;109(3):181-187. [CrossRef]

- Panchawagh SJ, Kumar P, Srikumar S, et al. Role of Micronutrients in the Management of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J Med Spec. 2023;14(4):187-196. [CrossRef]

- Sumathi T, Manivasagam T, Thenmozhi AJ. The Role of Gluten in Autism. Adv Neurobiol. 2020;24:469-479. [CrossRef]

- Usui N, Kobayashi H, Shimada S. Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5487. [CrossRef]

- Woo T, King C, Ahmed NI, et al. microRNA as a Maternal Marker for Prenatal Stress-Associated ASD, Evidence from a Murine Model. J Pers Med. 2023;13(9):1412. [CrossRef]

- Love C, Sominsky L, O’Hely M, Berk M, Vuillermin P, Dawson SL. Prenatal environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder and their potential mechanisms. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):393. [CrossRef]

- Subashi E, Lemaire V, Petroni V, Pietropaolo S. The Impact of Mild Chronic Stress and Maternal Experience in the Fmr1 Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11398. [CrossRef]

- Ahmavaara K, Ayoub G. Stress and Folate Impact Neurodevelopmental Disorders. J Health Care Res. 2024;5(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Hoover DW, Kaufman J. Adverse childhood experiences in children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(2):128-132. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Garcia A, Park JJ, Toliver AA, Ramos L, Aizenman CD. Early Developmental Exposure to Fluoxetine and Citalopram Results in Different Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Neuroscience. 2021;467:110-121. [CrossRef]

- Bravo K, González-Ortiz M, Beltrán-Castillo S, Cáceres D, Eugenín J. Development of the Placenta and Brain Are Affected by Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Exposure During Critical Periods. In: Gonzalez-Ortiz M, ed. Advances in Maternal-Fetal Biomedicine: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Pregnancy Pathologies. Springer International Publishing; 2023:179-198. [CrossRef]

- Arzuaga AL, Teneqexhi P, Amodeo K, Larson JR, Ragozzino ME. Prenatal stress and fluoxetine exposure in BTBR and B6 mice differentially affects autism-like behaviors in adult male and female offspring. Physiol Behav. 2025;295:114891. [CrossRef]

- Arzuaga AL, Edmison DD, Mroczek J, Larson J, Ragozzino ME. Prenatal stress and fluoxetine exposure in mice differentially affect repetitive behaviors and synaptic plasticity in adult male and female offspring. Behav Brain Res. 2023;436:114114. [CrossRef]

- Lan Z, Tachibana RO, Kanno K. Chronic exposure of female mice to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during lactation induces vocal behavior deficits in pre-weaned offspring. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;230:173606. [CrossRef]

- Croen LA, Ames JL, Qian Y, et al. Inflammatory Conditions During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2024;4(1):39-50. [CrossRef]

- Ye W, Luo C, Zhou J, et al. Association between maternal diabetes and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 202 observational studies comprising 56·1 million pregnancies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;0(0). [CrossRef]

- Fardous AM, Heydari AR. Uncovering the Hidden Dangers and Molecular Mechanisms of Excess Folate: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(21):4699. [CrossRef]

- Miraglia N, Dehay E. Folate Supplementation in Fertility and Pregnancy: The Advantages of (6S)5-Methyltetrahydrofolate. Altern Ther Health Med. 2022;28(4):12-17.

- Xu X, Zhang Z, Lin Y, Xie H. Risk of Excess Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation in Offspring. Nutrients. 2024;16(5):755. [CrossRef]

- Ledowsky CJ, Schloss J, Steel A. Variations in folate prescriptions for patients with the MTHFR genetic polymorphisms: A case series study. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2023;10:100277. [CrossRef]

- Maguire G. Vaccine Induced Autoimmunity May Cause Autism and Neurological Disorders. Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2025;9(1):103-132.

- Sotelo-Orozco J, Schmidt RJ, Slupsky CM, Hertz-Picciotto I. Investigating the Urinary Metabolome in the First Year of Life and Its Association with Later Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder or Non-Typical Neurodevelopment in the MARBLES Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9454. [CrossRef]

- Parenti M, Shoff S, Sotelo-Orozco J, Hertz-Picciotto I, Slupsky CM. Metabolomics of mothers of children with autism, idiopathic developmental delay, and Down syndrome. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):31981. [CrossRef]

- Parenti M, Schmidt RJ, Tancredi DJ, Hertz-Picciotto I, Walker CK, Slupsky CM. Neurodevelopment and Metabolism in the Maternal-Placental-Fetal Unit. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(5):e2413399. [CrossRef]

- Merchak AR, Bolen ML, Tansey MG, Menees KB. Thinking outside the brain: Gut microbiome influence on innate immunity within neurodegenerative disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2024;21(6). [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary MR, Kain JN, Chen SY, et al. Pilot study of probiotic/colostrum supplementation on gut function in children with autism and gastrointestinal symptoms. PloS One. 2019;14(1):e0210064. [CrossRef]

- Dossaji Z, Khattak A, Tun KM, Hsu M, Batra K, Hong AS. Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplant on Behavioral and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Pediatric Autism: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms. 2023;11(3):806. [CrossRef]

- Zang Y, Lai X, Li C, Ding D, Wang Y, Zhu Y. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Various Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders-An Evidence Mapping Based on Quantified Evidence. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:5127157. [CrossRef]

- Lagod PP, Abdelli LS, Naser SA. An In Vivo Model of Propionic Acid-Rich Diet-Induced Gliosis and Neuro-Inflammation in Mice (FVB/N-Tg(GFAPGFP)14Mes/J): A Potential Link to Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(15):8093. [CrossRef]

- Retuerto M, Al-Shakhshir H, Herrada J, McCormick TS, Ghannoum MA. Analysis of Gut Bacterial and Fungal Microbiota in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Non-Autistic Siblings. Nutrients. 2024;16(17):3004. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Díaz J, Gómez-Fernández A, Chueca N, et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) with and without Mental Regression is Associated with Changes in the Fecal Microbiota. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):337. [CrossRef]

- Brister D, Rose S, Delhey L, et al. Metabolomic Signatures of Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Pers Med. 2022;12(10):1727. [CrossRef]

- Che X, Roy A, Bresnahan M, et al. Metabolomic analysis of maternal mid-gestation plasma and cord blood in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(6):2355-2369. [CrossRef]

- Vacy K, Thomson S, Moore A, et al. Cord blood lipid correlation network profiles are associated with subsequent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder symptoms at 2 years: a prospective birth cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2024;100:104949. [CrossRef]

- Nabetani M, Mukai T, Taguchi A. Cell Therapies for Autism Spectrum Disorder Based on New Pathophysiology: A Review. Cell Transplant. 2023;32:9636897231163217. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens AP, Hyötyläinen T, Petrone JR, et al. Infant microbes and metabolites point to childhood neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. 2024;187(8):1853-1873.e15. [CrossRef]

- Freitas BC, Beltrão-Braga PCB, Marchetto MC. Modeling Inflammation on Neurodevelopmental Disorders Using Pluripotent Stem Cells. Adv Neurobiol. 2020;25:207-218. [CrossRef]

- Tsukada T, Shimada H, Sakata-Haga H, Iizuka H, Hatta T. Molecular mechanisms underlying the models of neurodevelopmental disorders in maternal immune activation relevant to the placenta. Congenit Anom. 2019;59(3):81-87. [CrossRef]

- Frye RE, Rincon N, McCarty PJ, Brister D, Scheck AC, Rossignol DA. Biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Dis. 2024;197:106520. [CrossRef]

- Amini-Khoei H, Taei N, Dehkordi HT, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Ocimum basilicum L. Extract in Alleviating Autistic-Like Behaviors Induced by Maternal Separation Stress in Mice: Role of Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress. Phytother Res. 2025;39(1):64-76. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen V, Tang J, Oroudjev E, et al. Cytotoxic Effects of Bilberry Extract on MCF7-GFP-Tubulin Breast Cancer Cells. J Med Food. 2010;13(2):278-285. [CrossRef]

- Jessica Tang, Emin Oroudjev, Leslie Wilson, George Ayoub. Delphinidin and cyanidin exhibit antiproliferative and apoptotic effects in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Integr Cancer Sci Ther. 2015;2(1). [CrossRef]

- Lai M, Lee J, Chiu S, et al. A machine learning approach for retinal images analysis as an objective screening method for children with autism spectrum disorder. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100588. [CrossRef]

- Farooq MS, Tehseen R, Sabir M, Atal Z. Detection of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children and adults using machine learning. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9605. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).