1. Introduction

The efficient detection of pathogenic microorganisms is critical in various fields. Traditional methods based on microbial culture, while effective, require long incubation periods and specialized laboratories. Alternatively, optical sensors offer rapid, portable, and specific detection, making them a promising solution for on-site applications [

1,

2].

The detection of pathogenic bacteria in clinical, food, or environmental samples is essential for infection control, outbreak prevention, and food safety assurance. In this context, optical sensors have revolutionized diagnostic microbiology by offering viable alternatives to traditional culturing methods, which, although specific, often require between 24 and 72 hours to produce results [

3].

Optical sensors identify bacterial presence by detecting variations in optical parameters, such as absorbance, transmittance, reflectance, fluorescence, or visible color change, triggered by microbial metabolism [

4]. These sensors are known for their high sensitivity, rapid detection capabilities, compact form factors, and, in many cases, portability [

5].

In particular, fiber optic biosensors allow the detection of changes in the surrounding medium through variations in light intensity, refraction, or wavelength [

6]. Combining this technology with colorimetric detection, where bacterial presence induces color changes in the medium, enables the development of low-cost, highly sensitive, and visually interpretable devices [

7,

8].

This work explores the theoretical basis and preliminary design of an optical sensor for bacterial detection using color change as the primary transduction mechanism.

2. Theoretical Framework

Conventional microbiological culture-based techniques, while accurate, require extended incubation times and specialized handling. In response to these limitations, optical sensors—particularly optical biosensors—have emerged as promising tools for bacterial detection due to their high sensitivity, specificity, miniaturization capabilities, and potential for in situ implementation [

1,

2].

Fiber-optic sensors operate by detecting changes in optical parameters such as intensity, phase, polarization, wavelength, or refractive index when light interacts with a target [

6]. These changes can be induced by alterations in the sensor’s immediate environment, either due to the direct presence of bacteria or their metabolic by-products. In colorimetric systems in particular, sensors respond to visible optical transformation that are associated with biochemical processes, such as medium acidification or the degradation of indicator compounds [

7,

8].

Physical Principles of Optical Sensors for Bacterial Detection

Optical sensors function based on photometry, spectroscopy, or interferometry. Essentially, a light source (e.g., LED or tungsten halogen lamp) emits light through a sample enclosed in an optically accessible medium. A detector (photodiode, spectrometer, CCD, or digital camera) captures the light signal transmitted or reflected by the sample, quantifying changes over time or across specific wavelengths [

5,

9].

Key parameters include:

- Wavelength range: Typically within the visible spectrum (400–700 nm) or UV-Vis for greater spectral resolution.

- Interaction type: Direct transmittance, differential absorbance, or diffuse reflectance.

- Temporal resolution: From seconds to several hours.

- Optical configuration: Linear setup, fiber optics, integrated spectroscopy, or digital imaging [

10].

Optical Biosensors: Principles and Advantages

Fiber-optic biosensors can be classified according to their detection principle. Intensity-based sensors are the simplest and most robust, detecting the attenuation or amplification of light transmitted through the fiber due to optical interactions with the surrounding medium [

6]. This type of sensor has been used to monitor bacterial growth in real time by tracking refractive index changes in the medium, as demonstrated by Soares et al. [

15] with E. coli in a liquid medium.

More sophisticated approaches utilize phenomena such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), in which an electromagnetic wave resonates with electrons on a metal-coated fiber surface, altering the optical signal in the presence of bacteria or specific biomarkers [

16,

17]. These sensors have demonstrated high sensitivity in complex matrices such as food and biological fluids.

Practically speaking, optical biosensors offer multiple advantages over conventional methods: they enable online analysis, are compatible with hostile or contaminated environments, do not require additional biological labels, and can be easily miniaturized for point-of-care applications [

11].

Colorimetric Detection of Bacterial by Products

An alternative approach to direct bacterial detection involves identifying metabolic products that cause optical changes in the medium. For instance, several studies have incorporated biomimetic membranes or reactive matrices containing tetrazolium salts or redox indicators that undergo visible color changes upon reduction by active bacterial enzymes [

8,

20]. This type of visual signal can be quantitatively correlated with bacterial concentration and thus used as a reliable proxy for microbial contamination.

Zhao et al. [

12] demonstrated a glucose-metabolism-based technique in which bacterial activity enzymatically transforms glucose, triggering a measurable color change implemented in a paper-based reactive matrix [

18,

19]. These systems are particularly attractive due to their low cost, portability, and adaptability.

Mannitol Salt Agar and Detection of Staphylococcus aureus

Mannitol salt agar (MSA) is a selective and differential medium widely used to isolate Staphylococcus aureus. It contains a high concentration of NaCl (7.5%), which inhibits the growth of non-halotolerant organisms, and mannitol as a fermentable carbohydrate. S. aureus ferments mannitol, producing acid that lowers the pH and causes the phenol red indicator to shift from red to yellow [

28].

This chromogenic shift, easily visible to the naked eye, is ideal for quantitative optical sensing, allowing the design of devices that detect S. aureus presence significantly faster than conventional culturing methods [

29].

Types of Optical Sensors for Bacterial Detection

Transmittance-Based Sensors: These sensors quantify the amount of light passing through a culture medium. Zhu et al. [

30] developed a system using a halogen-tungsten light source and a photodetector within a closed vial containing MSA, achieving detection of S. aureus in approximately 150 minutes.

RGB Imaging and Computer Vision: Imaging systems capture periodic photographs of the culture surface and analyze them via RGB algorithms. Singh et al. (2022) applied machine learning to RGB image data to differentiate colonies of S. aureus, E. coli, and others with high accuracy [

31].

Optical Fiber Sensors: These sensors utilize optical fibers to detect changes in the refractive index or transmitted light intensity due to microbial activity. Suitable for in situ applications, these systems can be integrated into fluidic environments. Stewart et al. (2015) reported highly miniaturized and sensitive fiber-optic biosensors [

9].

LED and Photodiode Modules: These compact devices integrate light-emitting diodes and photodetectors. Jasim et al. (2018) designed a system for detecting S. aureus based on changes in light intensity, achieving detection limits below 10³ CFU/mL in under 2 hours [

33].

See accompanying table for a comparison of detection range, media, light sources, and sensor types [

30,

31,

32].

Table 1.

Comparison of optical bacteria detection sensors and their different technologies.

Table 1.

Comparison of optical bacteria detection sensors and their different technologies.

| Type of sensor |

Detection Time (min) |

Detection Limit (CFU/mL) |

Estimated Cost (USD) |

Portability |

| Transmittance |

150 |

1000.0 |

300 |

Medium |

| RGB + Ai |

90 |

500.0 |

500 |

High |

| Optical Fiber |

120 |

100.0 |

700 |

Medium |

| LED-Photodiode |

100 |

1000.0 |

150 |

High |

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

The development of fiber-optic bacterial sensors presents a tangible opportunity to enhance responses to epidemiological outbreaks, monitor water and food quality, and detect clinical infections rapidly. Applications range from disposable devices for surface analysis to integrated platforms for production lines or intensive care units [

11,

12,

13].

The closest applications for this type of sensors can be summarized as:

Clinical diagnostics: Early detection in hospitals to prevent nosocomial infections.

Food industry: Online contamination monitoring in processing environments.

Environmental surveillance: Field-deployable sensors for water quality analysis.

Telemedicine: Smartphone-integrated optical readers for remote diagnosis [

34].

Current challenges include improving selectivity against interferents, enhancing the stability of optically active materials, achieving electronic miniaturization for automated readout and interpretation, and conducting clinical or regulatory validation for widespread use.

The field is evolving toward hybrid systems that combine optical techniques with microfluidics, electrochemical biosensors, electrical signals, multiplexed biosensors, nanotechnology and autonomous systems connected to mobile devices or IoT networks [

11,

14]. Biodegradable sensors and artificial intelligence integration promise improved specificity and cost efficiency [

3,

31,

34].

In this paper, we present a novel method for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus using an optical setup that detects transmittance intensity changes at four different wavelengths and relates these intensity changes to the presence of Staphylococcus aureus.

5. Discussion

The optical sensor system developed in this study demonstrates remarkable performance in terms of sensitivity, response time, and practicality when compared to traditional microbiological methods and more complex biosensing alternatives. The system effectively detects the presence of

Staphylococcus aureus through the color change of mannitol salt agar (MSA), achieving positive detection in approximately 2–2.5 hours. This represents a 10-fold reduction in detection time compared to the conventional 24-hour incubation and observation required in standard culture-based methods [

28].

A key advantage of the system lies in its low reagent consumption. While standard Petri dishes typically require 20–40 mL of agar per assay, this device operates with only 250 µL per test, enabling a reduction in reactant use by at least 80 times. This not only translates to significant cost savings, but also aligns with sustainable laboratory practices, an increasingly relevant concern in global health systems [

10,

30].

In contrast to molecular detection methods such as PCR or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), this optical sensor set-up does not require sample lysis, nucleic acid extraction, thermal cycling, or expensive probes or enzymes. These characteristics, while delivering excellent specificity in PCR, greatly increase the cost and complexity of diagnostic infrastructure [

3,

5]. The current device eliminates these bottlenecks by relying entirely on observable metabolic changes (i.e., acid production from mannitol fermentation) to trigger an optical signal, thereby preserving simplicity and accessibility.

While other optical systems, such as those using spectrophotometry [

30], fiber-optic interferometry [

9], or RGB image classification [

31], have also achieved reduced detection times, these often require costly and delicate components (e.g., spectrometers, optical filters, high-resolution cameras, and computing units). Moreover, these setups can demand controlled lighting and precise positioning, which may not be feasible in field or decentralized settings [

31,

34].

The present work circumvents these challenges by adopting a structural innovation: rather than introducing new reagents or consumables, the detection system was miniaturized and optimized through changes in geometry and light path configuration. This structural shift preserves the biological basis of detection (color change in MSA) but allows for greater reproducibility, alignment tolerance, and potential for automation or parallel testing.

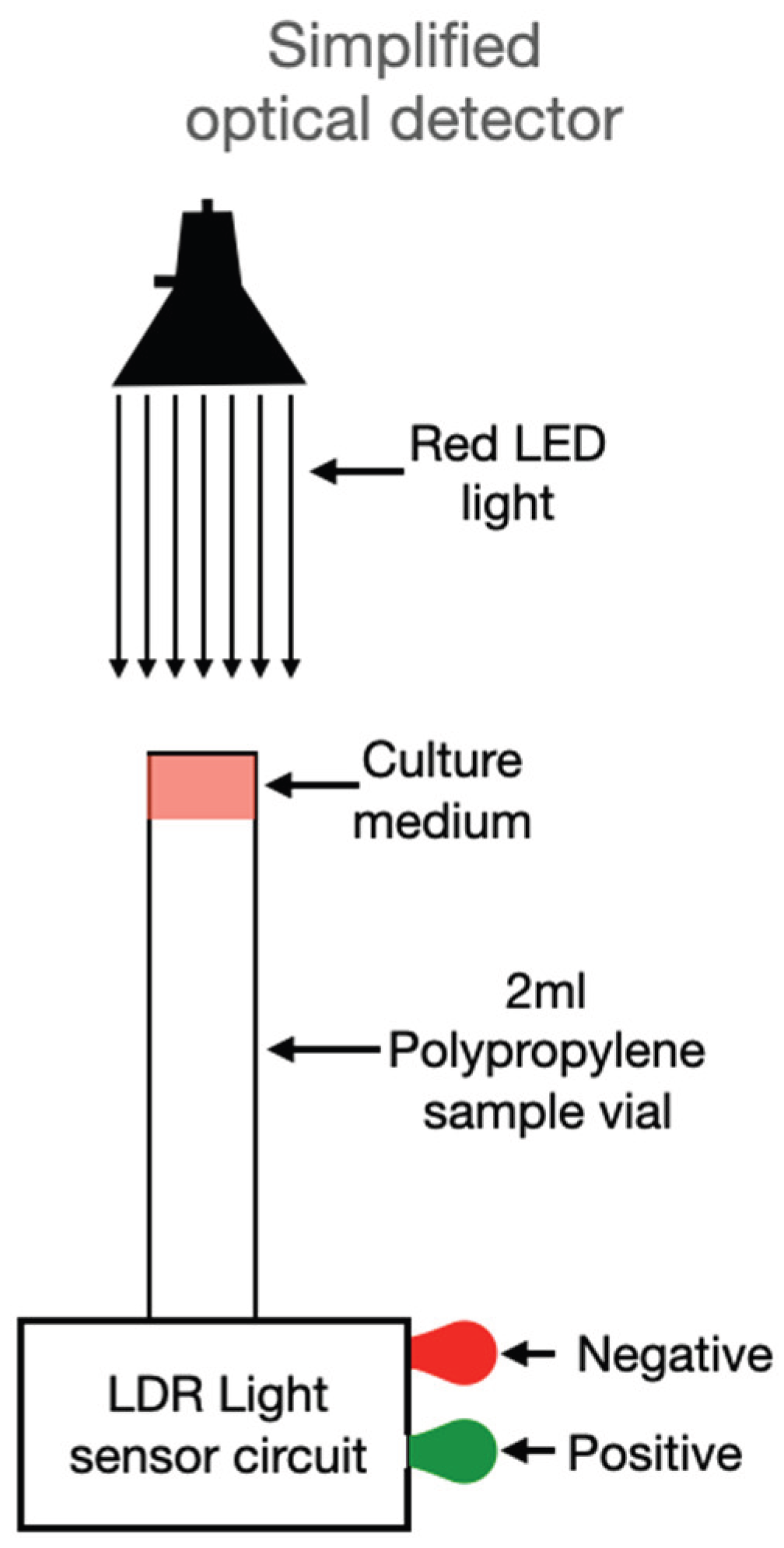

In its initial configuration, the device used a halogen–tungsten light source coupled with a spectrophotometer to quantify the transmittance change at specific wavelengths. Although accurate, this setup poses limitations for widespread use due to cost and bulk. However, based on the data obtained, a simplified version is proposed (

Figure 7), replacing the broadband light source with a red LED (650 nm), selected to match the absorbance shift of the phenol red indicator used in MSA. In place of a spectrophotometer, a light-dependent resistor (LDR) is used as an intensity detector. This sensor, connected to a basic analog circuit, takes a single measurement after 90 minutes and then monitors for consistent intensity increases over a 10–20 minute window. If a defined threshold is crossed, the system activates an optical or digital signal indicating the presence of

S. aureus.

This simplified architecture holds significant promise for mass deployment. Notably, the design can be manufactured using low-cost materials, powered by batteries or solar sources, and embedded in mobile or wearable diagnostic units. The detection logic is binary and does not require software interpretation, enabling use by non-specialized personnel—a critical requirement for deployment in remote or under-resourced areas.

When compared to fiber-optic sensors described by Stewart et al. [

9], which require delicate fiber tips and often show drift or fouling over time, this system offers greater robustness and lower maintenance. Similarly, when contrasted with the AI-enhanced imaging models of Singh et al. [

31], which provide high classification performance but demand camera calibration and processing hardware, this sensor stands out in portability and immediacy of results.

Furthermore, unlike surface plasmon resonance sensors [

32], which require metal coatings and nanostructured surfaces for refractive index modulation, the proposed system uses standard, transparent plastic or glass containers and does not rely on any surface engineering or immobilization chemistry, dramatically reducing barriers to implementation.

Importantly, the design maintains biosafety by allowing the sample to remain sealed throughout the detection process. This feature protects the environment and the operator from potential contamination, which is particularly relevant in settings where bacterial strains may be pathogenic or multidrug-resistant.

Additionally, the potential for multiplexing is evident: by adapting the wavelength of the light source and the detection algorithm, the system could be tuned to monitor various chromogenic or pH-sensitive media for other pathogens. The modularity of the design also makes it compatible with integration into existing laboratory incubators or portable microcontrollers for remote data collection, as suggested by López-Ruiz et al. [

34].

In summary, this optical detection system:

Outperforms standard methods by reducing detection time from 24 h to under 3 h [

28,

30];

Minimizes resource consumption by reducing agar volume from 20–40 mL to 250 µL [

10];

Avoids the need for complex instruments like PCR thermocyclers or spectrometers [

3,

5,

30];

Simplifies user operation, with a plug-and-play detection module and sealed sample handling [

33];

Facilitates mass adoption through scalability, cost-efficiency, and minimal training requirements [

34].

Nevertheless, certain limitations remain. While the color change in MSA is highly indicative of

S. aureus, it is not exclusive, and false positives may occur with other mannitol-fermenting organisms [

28,

29]. Further refinement, such as wavelength discrimination or biochemical confirmation, could enhance specificity. Additionally, environmental conditions such as ambient light or temperature could influence measurements and should be controlled or compensated for in future iterations.

Ultimately, the presented results affirm that optical sensing coupled with colorimetric media offers a robust, scalable, and accessible alternative to both traditional culture and high-tech biosensor systems. It is a solution well aligned with the priorities of decentralized diagnostics, global health equity, and sustainable biomedical technology.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this research validate the efficiency, practicality, and cost-effectiveness of the proposed optical sensor for detecting

Staphylococcus aureus in mannitol salt agar (MSA). In contrast to high-complexity biosensors relying on molecular recognition elements like antibodies or nucleic acids [

3,

5], this sensor employs a straightforward physical principle—color change detection—which can be monitored optically. This simplicity translates into several key advantages.

First, the use of standard MSA media and conventional inoculation techniques ensures that laboratory personnel require no additional training to implement the sensor. This is in stark contrast with biosensors that demand sterile microfluidics, antibody conjugation, or microfabricated surfaces [

9,

32]. The ability to use traditional microbiological methods while integrating an optical readout streamlines the adoption process in clinical and field settings.

Second, the reduction of reagents by a factor of 125 represents a significant leap in sustainability and resource management. Traditional Petri dish cultures often use 30–40 mL of medium per test. The miniaturized system uses only 250 µL, which not only conserves reagents but also decreases waste generation and facilitates batch testing in small-volume formats such as microtubes or vials. This aligns with trends toward minimal sample and reagent consumption in modern diagnostic devices [

10,

31].

Third, time-to-detection is critically improved. The proposed prototype is not the fastest in terms of detection time since there are detection models functionalized with silver nanoparticles that have detection times as low as 20 minutes [

19], however standard agar-based tests may require overnight incubation to visualize bacterial colonies and color changes, typically 18–24 hours. The sensor proposed in this study achieves detection in 150 minutes or less, a time reduction of over 10-fold. This is comparable to or better than some real-time imaging techniques and certainly superior to most culture-based diagnostics. In outbreak scenarios or settings where rapid response is essential, this time saving could be decisive in initiating treatment or containment measures [

30,

34].

Fourth, the device’s architecture is minimalistic yet functional. Comprising an LED light source optimized for red wavelengths, a light-dependent resistor (LDR), and a basic electronic circuit, the system delivers binary optical outputs (signal/no signal). Unlike systems that require spectral analysis, digital imaging, or AI-driven classification [

31], this sensor provides immediate and interpretable results. Such simplicity enhances durability, reduces maintenance, and facilitates deployment in decentralized or mobile testing units.

In evaluating its performance alongside other optical sensors, such as fiber-optic configurations [

9], colorimetric camera systems [

34], or plasmonic biosensors [

32], the proposed device stands out for its affordability, ease of fabrication, and integrability with standard lab workflows. These characteristics make it an excellent candidate for scalable manufacturing and distribution, especially in low-resource regions.

Furthermore, the design supports future optimization. Integrating the sensor with wireless transmission modules or embedding it in automated incubators could support continuous monitoring. Multiplexing the sensor in array formats could enable parallel testing for multiple pathogens. Even the incorporation of smartphone-based light analysis, as suggested in emerging literature [

34], could add a layer of digital validation without compromising simplicity.

In conclusion, this study presents an optical detection system that redefines practical microbial diagnostics by uniting conventional microbiology with accessible sensing technology. It offers a high-impact tool for applications where speed, cost, and usability are essential, without compromising diagnostic accuracy. The approach also opens pathways for future sensor innovation, particularly in alignment with global health goals for decentralizing diagnostic tools and promoting sustainable laboratory practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S. and G.R.; methodology, A.A.S. and G.R.; validation, D.C., V.L. and J.P.P.-M.; formal analysis, A.A.S., G.R., and C.P.; investigation, G.R.; resources, A.A.S.; data curation, G.R. and A.C.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.S.; writing—review and editing, D.C., V.L., J.P.P.-M., and C.P.; supervision, A.A.S., G.R., and A.C.-F.; project administration, A.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

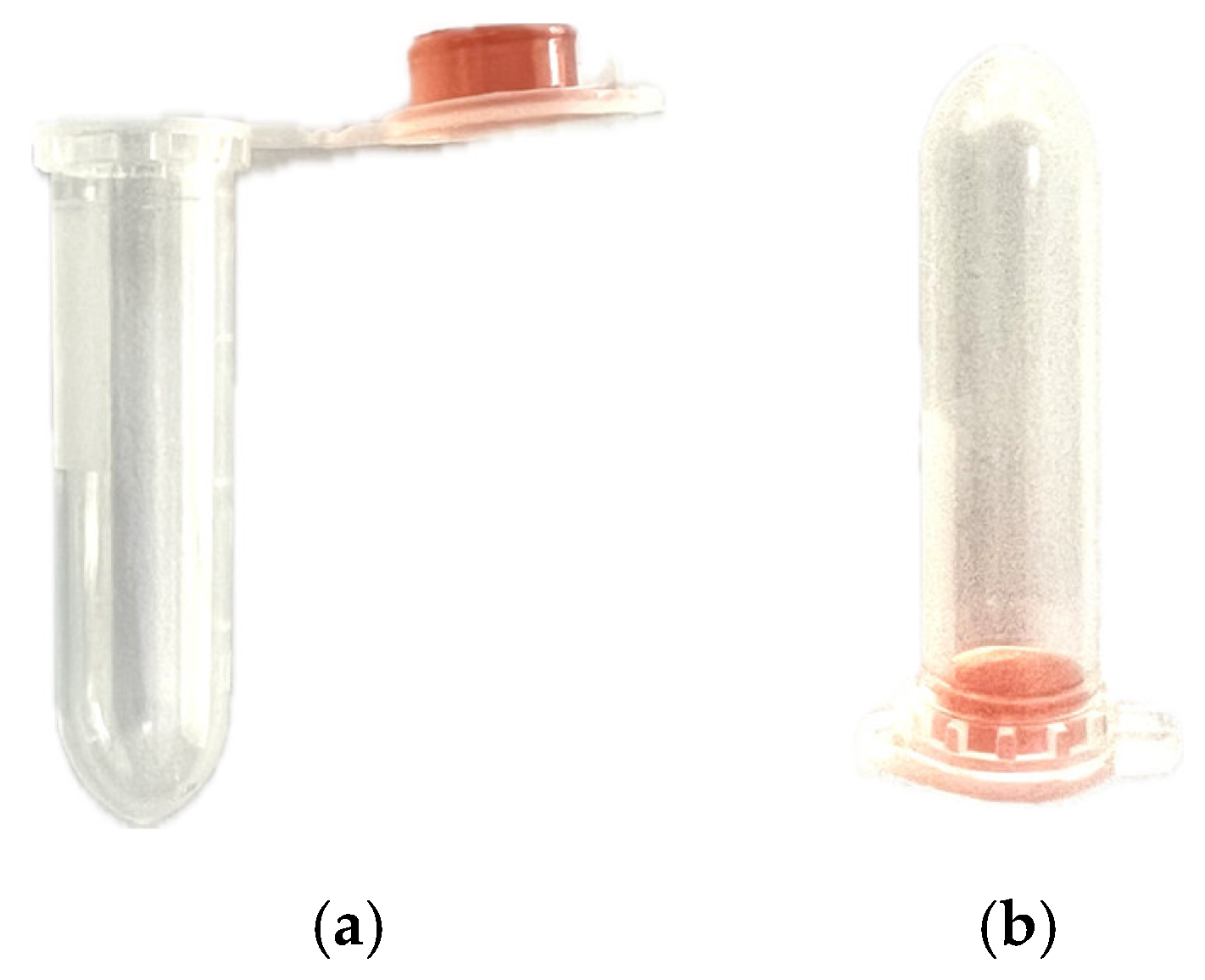

Figure 1.

Prototype configuration showing 250 µL of Mannitol Salt Agar contained in the cap of a 2 mL transparent polypropylene vial, a) open, b) closed.

Figure 1.

Prototype configuration showing 250 µL of Mannitol Salt Agar contained in the cap of a 2 mL transparent polypropylene vial, a) open, b) closed.

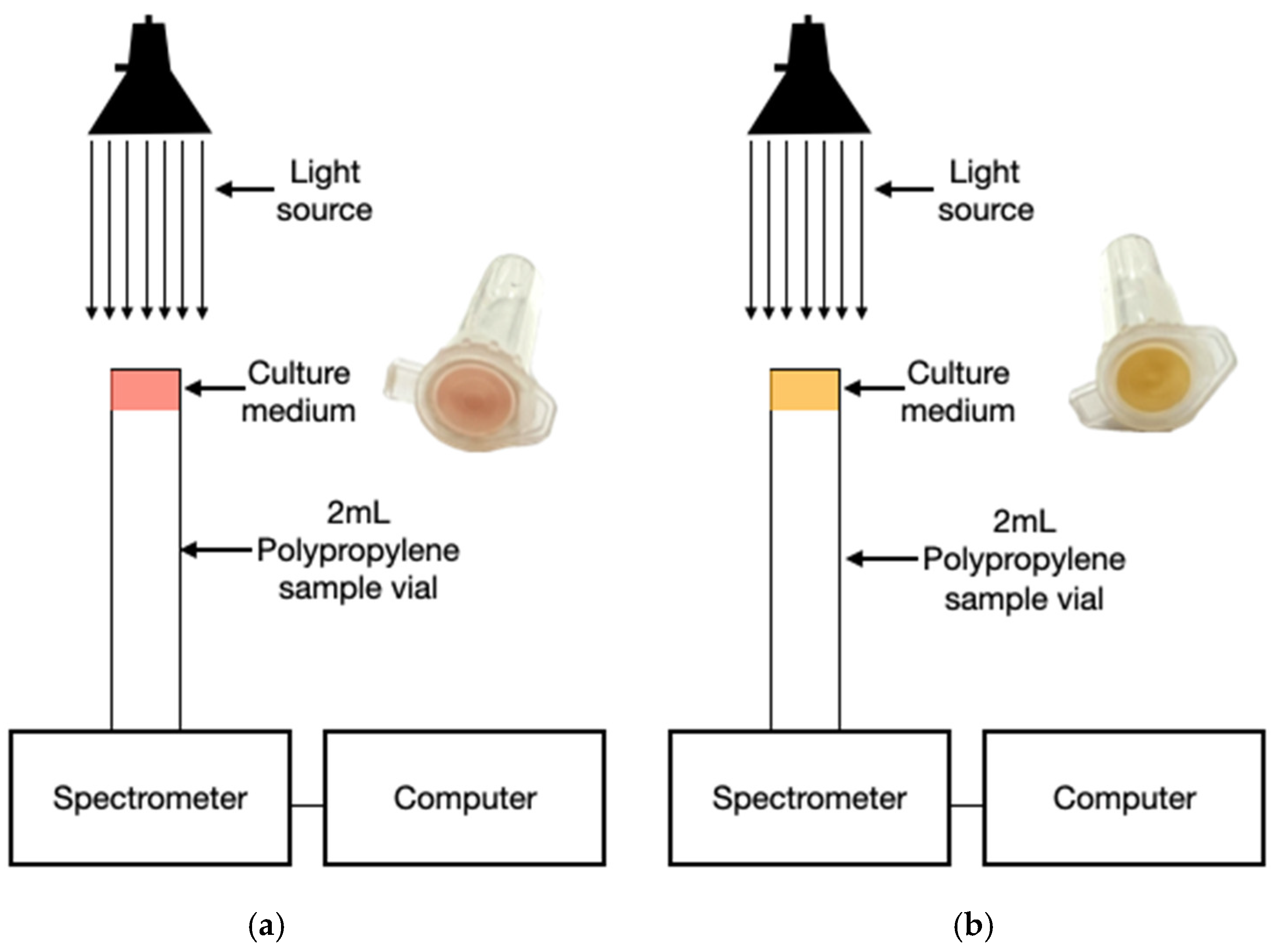

Figure 2.

Optical detection system during incubation. a) Inoculated MSA with initial red coloration (pH > 7.4); b) yellow coloration indicating acidification from mannitol fermentation (pH < 6.8).

Figure 2.

Optical detection system during incubation. a) Inoculated MSA with initial red coloration (pH > 7.4); b) yellow coloration indicating acidification from mannitol fermentation (pH < 6.8).

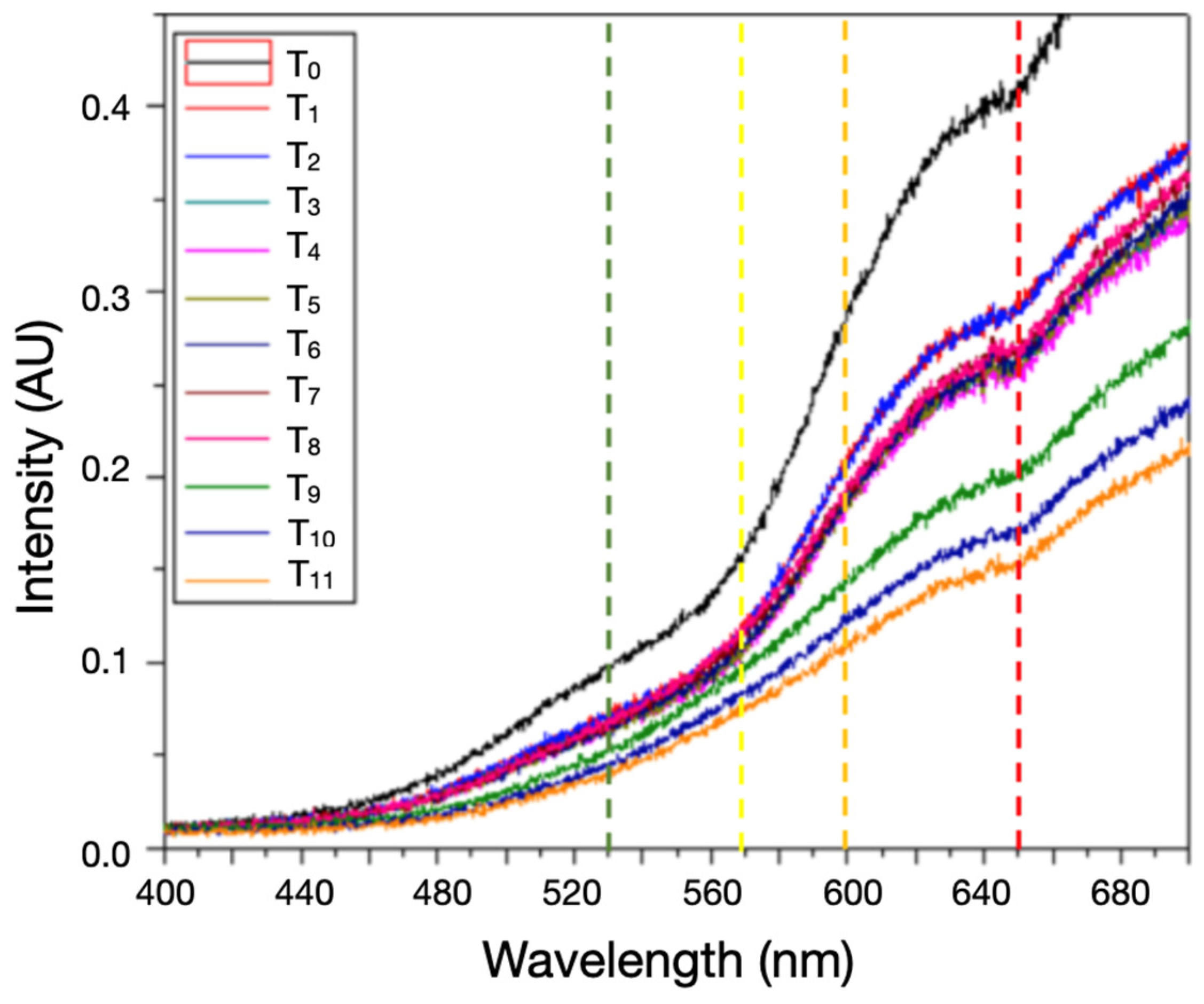

Figure 3.

Intensity transmission profiles varying over time during 330 minutes of time-lapse intensity measurement where T0=0 mins, T1=10 min, T2=10 min, T3=30 min, T4=60 min, T5=90 min, T6=110 min, T7=125 min, T8=140 min, T9=270 min, T10=305 min, T11=330 min, are the times of measurement.

Figure 3.

Intensity transmission profiles varying over time during 330 minutes of time-lapse intensity measurement where T0=0 mins, T1=10 min, T2=10 min, T3=30 min, T4=60 min, T5=90 min, T6=110 min, T7=125 min, T8=140 min, T9=270 min, T10=305 min, T11=330 min, are the times of measurement.

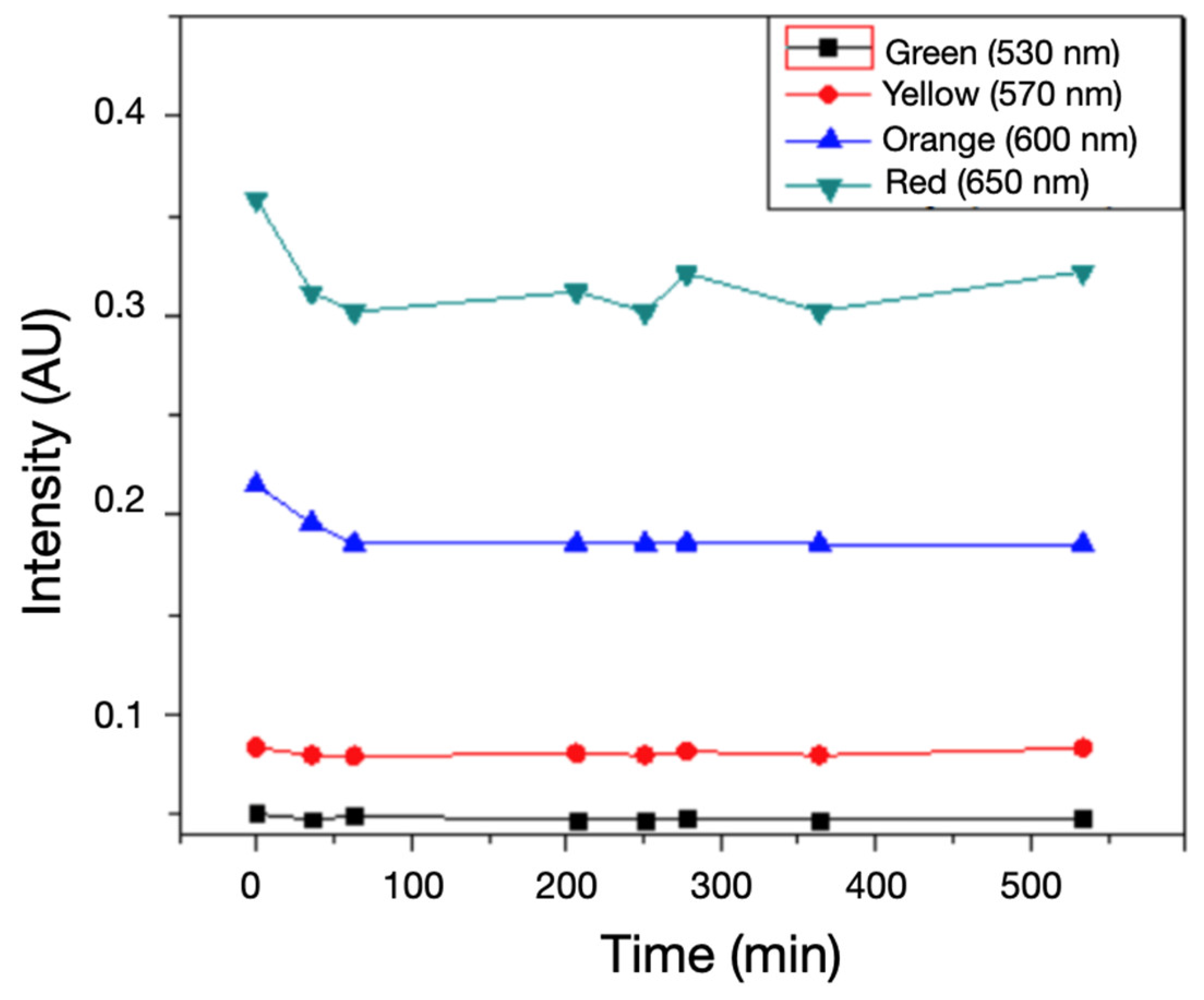

Figure 4.

Profile of transmitted light intensity and its evolution over 330 minutes at specific wavelengths: green, yellow, orange and red.

Figure 4.

Profile of transmitted light intensity and its evolution over 330 minutes at specific wavelengths: green, yellow, orange and red.

Figure 5.

Control samples without bacterial inoculation maintained consistent spectral intensity, confirming the specificity of the signal change to bacterial metabolic activity.

Figure 5.

Control samples without bacterial inoculation maintained consistent spectral intensity, confirming the specificity of the signal change to bacterial metabolic activity.

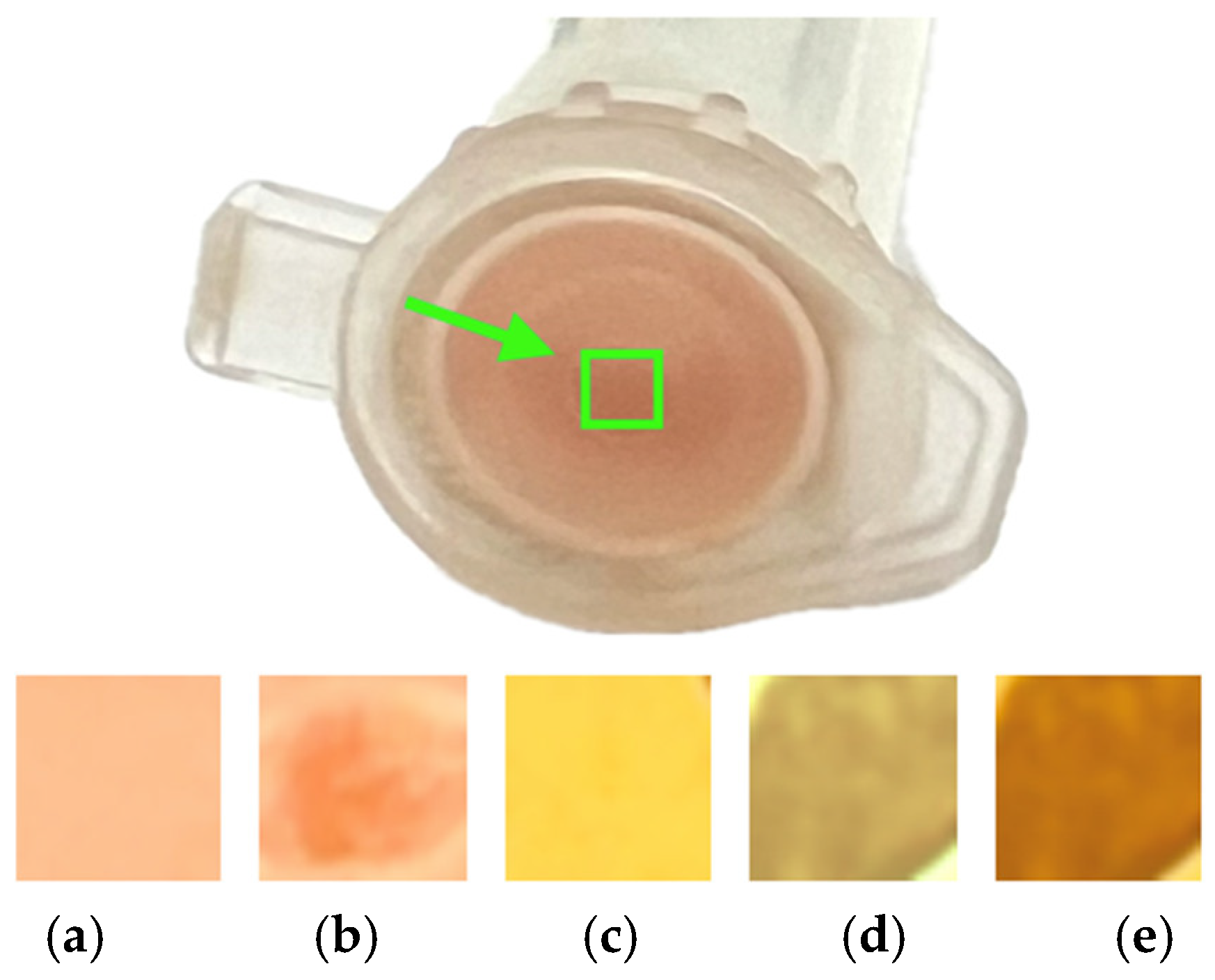

Figure 6.

Evolution of transmitted light through the inoculated ASM sample in the vial cap under observation in the enclosed area; initial red color a), attenuation of transmitted light b), ASM color change c), gradual decrease in transmitted light d), and e).

Figure 6.

Evolution of transmitted light through the inoculated ASM sample in the vial cap under observation in the enclosed area; initial red color a), attenuation of transmitted light b), ASM color change c), gradual decrease in transmitted light d), and e).

Figure 7.

Simplified detector setup, using a monochromatic light source and an LDR sensor to measure transmittance variation and identify S. aureus growth in MSA through automated signal detection.

Figure 7.

Simplified detector setup, using a monochromatic light source and an LDR sensor to measure transmittance variation and identify S. aureus growth in MSA through automated signal detection.