1. Introduction

Euthyroid sick syndrome or low T

3 or non-thyroidal illness syndrome is a condition induced by severe illness in patients in which thyroid or hypothalamic and pituitary disease is absent [

1,

2]. It reflects an adaptation of the thyroid to severe disease [

2]. The condition was described in the 1970s, as it had been observed that a drop in thyroid hormone levels occurred in starvation and during illness. In a state of mild illness T

3 levels decreased but as illness duration and severity increased T4 levels decreased as well. This drop in thyroid hormone levels was observed in a variety of disease states. By contrast to hypothyroidism, decreased peripheral thyroid hormone levels were not followed by an increase in TSH levels. Following these early observations, various studies investigated alterations in thyroid hormone secretion observed during acute illness [

3]. However, the exact pathophysiology of euthyroid sick syndrome is still under investigation.

Various mechanisms are involved in the pathophysiology of euthyroid sick syndrome. Modulation of deiodinase activity, in particular upregulation of deiodinase type 1 (D1) and type 3 (D3) lead to decreased production of FT

3 and increased production of the inactive compound rT

3[

2], respectively [

4,

5]. Modulation of hypothalamic pituitary secretory activity i.e. decreased TRH secretion due to higher inhibitory signals, impaired pulsatile TSH lead to decreased TSH levels. Leptin levels decrease as the illness progresses and lead to decreased TRH secretion and thereby decreased TSH levels [

6]. Thyroid hormone binding to transport proteins is modulated and may lead to the profile of euthyroid sick syndrome [

2]. Modulated T

3 binding to its receptors may also contribute to its pathogenesis [

2].

Euthyroid sick syndrome may be observed in the context of various situations and disease states, including starvation [

7,

8,

9], patients in the intensive care unit [

3], patients undergoing cardiac operations [

10,

11], in the premature infant [

3,

12], in severely ill pediatric and adult patients requiring extracorporeal circulatory support [

13], in patients with hip fractures [

14], in patients with acute complications of diabetes mellitus such as diabetic ketoacidosis [

15], in renal failure [

16] as well as in severely ill patients suffering from various conditions but not cared for in the intensive care unit [

17]. Modulation of the secretory activity of the hypothalamic pituitary unit by circulating inflammatory cytokines occurs during acute illness may lead to the hormone profile of euthyroid sick syndrome. Modulation of deiodinase activity has been considered a major mechanism leading to decreased secretion of T

3 and FT

3 and augmented secretion of rT

3. RT

3 is a thyroid hormone product and is deprived of the major actions of thyroid hormones. Modulation of thyroid hormone metabolism during acute disease is also thought of as another mechanism involved in the pathophysiology of euthyroid sick syndrome. Modulation of the conjugation of circulating thyroid hormones with thyroid binding proteins and albumin is also a mechanism considered to contribute to its pathogenesis [

18].

Euthyroid sick syndrome is mainly characterized by the presence of low FT

3 which is not accompanied by a compensatory increase in TSH levels. By contrast TSH levels decrease. As the underlying disease state deteriorates low FT

4 levels may be observed [

19]. These alterations reflect the effect of severe illness on inflammatory mediator secretion which affects the neuroendocrine and endocrine axis [

20].

Euthyroid sick syndrome has been observed in various forms of severe illness. In particular, in acute coronary artery disease events severe euthyroid sick syndrome may be observed [

21,

22] and it is considered a marker of disease outcome, i.e. survival or death [

23]. In patients cared for in acute care it may also be observed and it is considered a prognostic indicator of disease outcome.

In infectious diseases euthyroid sick syndrome is also observed [

18]. The condition has been described in earlier years in pulmonary tuberculosis [

24], in severe meningococcal infection18 and in infection from the human immunodeficiency virus [

25]. Chow et al [

24] studied patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and estimated thyroid hormone secretion in a cohort of these patients. They observed euthyroid sick syndrome in 63% of their cohort and they found that a very low FT

3 at presentation was related to subsequent mortality. Post et al [

26] studied endocrine function in active tuberculosis patients and they found that 92% of the patients had euthyroid sick syndrome at presentation. Den Brinker et al [

18] studied euthyroid sick syndrome in pediatric patients with meningococcal sepsis. They found that all their pediatric patients with severe meningococcal infection had alterations in thyroid hormone levels indicating the diagnosis of non-thyroidal illness syndrome. Altered thyroid hormone levels were inversely related to disease duration and might be due to type 3 deiodinase (D3) induction. In addition, dopamine was found to suppress TSH levels. T4 and IL-6 levels were predictive of mortality. In the context of COVID-19 infection euthyroid sick syndrome has been reported [

27]. In these patients it was a marker of disease outcome. The relationship of euthyroid sick syndrome with death is described in the literature [

23,

28,

29,

30]. In particular, euthyroid sick syndrome was found to be a marker of adverse outcome in elderly patients who had surgery for emergency situations28, in cardiac insufficiency [

29], in coronary artery disease [

23,

30] and in patients in sepsis [

31].

The aim was to investigate euthyroid sick syndrome and its relationship with disease severity and prognosis in a group of patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

In a group of 63 patients admitted to hospital for severe COVID-19 infection TSH, FT

3, FT

4 and CRP levels were measured. Patients underwent evaluation and treatment for severe COVID-19 disease. The patients were classified in 4 groups, a group with uncompromised respiratory function {disease severity 1), a group with mild respiratory insufficiency (disease severity 2), a group with severe respiratory insufficiency (disease severity 3) and a group with severe respiratory insufficiency requiring intubation (disease severity 4) (

Table 1). Patients had either one, two or three comorbidities.

TSH, Free T3 (FT3) and Free T4 (FT4) levels were measured by the application of chemiluminescence immunoassay technology, in particular, by the application of ARCHITECT Immunoassays (Abbot Park IL). Chemiluminescence Immunoassay is a laboratory method applied to detect analytes in biological fluids by the generation of light via a chemical reaction between specific antibodies and labeled molecules.

TSH levels were assayed in serum by the application of the ARCHITECT TSH immunoassay (Abbott Park IL), a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay. The analytical sensitivity of the immunoassay was <0.0025 μIU/ml, the precision was <10% and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was <20%. The assay uses flexible protocols, known as Chemiflex. The assay is based on acridinium labeled conjugate and the detection of relative light units by an optical system.

FT3 levels were assayed by the ARCHITECT FT3 assay (Abbott Park IL). The analytical sensitivity of the immunoassay was <1.0 pg/ml and the analytical specificity was <0.001%. The assay is based on acridinium labeled conjugate which is added to the reaction mixture.

FT4 levels were assayed by the ARCHITECT FT4 assay (Abbott Park IL). The analytical sensitivity of the immunoassay was <0.4 ng/dl and the precision was <10%. The assay is based on the inverse relationship between the amount of FT4 in the sample and the light units emitted during the reaction and detected by an optical system.

CRP was estimated by particle enhanced immunonephelometry (CardioPhase hsCRP, Siemens Helathcare Diagnostics, Camerley, UK), a method with a sensitivity and intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 0.175 mg/L with a CV of 7.6% at 0.41 mg/L, 2.7% at 14 mg/L and 2.0% at 14 mg/L, respectively.

All subjects included in the study did not have a known history of thyroid disease and were not taking any medication for thyroid disease.

Euthyroid disease was diagnosed if patients without a known history of thyroid disease had low FT3 levels in the presence of normal or low TSH levels.

The study had approval by the ethical committee of Asclepeion Hospital, Voula, Athens, Greece (approval number 15335, 24/11/2020). All the patients involved in the study gave their informed consent.

The statistical evaluation of the data generated in the study was performed by SPSS (IBP SPSS Statistics v27). Data are shown as mean±SD. For the statistical evaluation of qualitative data chi square test was performed. For the statistical evaluation of quantitative data ANOVA and linear regression analysis were performed.

Results

Euthyroid sick syndrome as assessed by low FT3 and normal or low TSH levels was observed in 36 of this cohort (57.1%), while 27 patients did not have such evidence.

Euthyroid sick syndrome was related to adverse outcome, i.e. non-survival or death (p<0.001, chi square test). Euthyroid sick syndrome was also related to disease severity (p<0.001, chi square test).

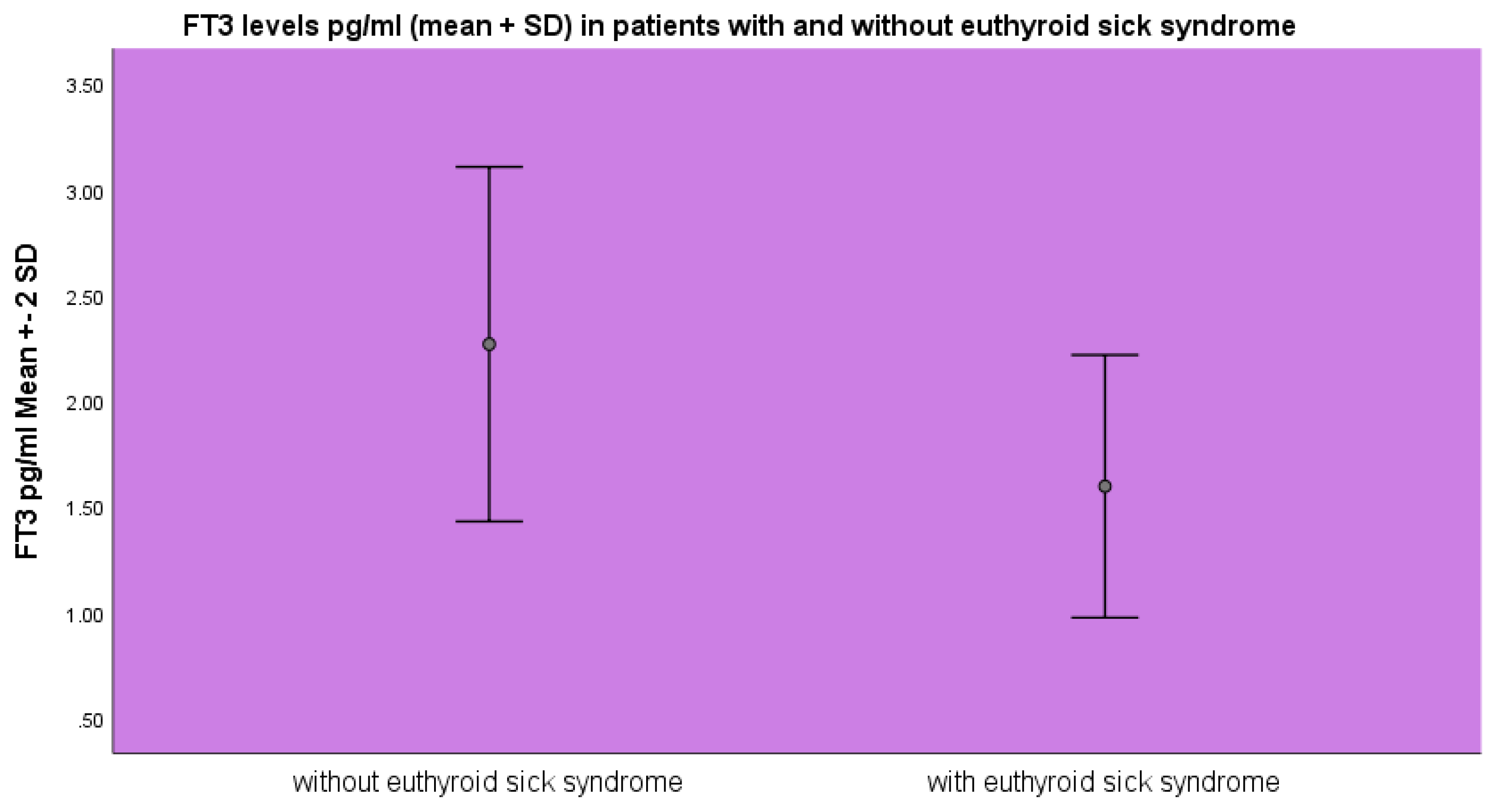

FT

3 levels were lower in the group of patients diagnosed with euthyroid sick syndrome 1.59±0.31 pg/ml as opposed to 2.26±0.31 pg/ml (mean ±SD) (p<0.001, ANOVA) as opposed to the patients without evidence of euthyroid sick syndrome (

Figure 1).

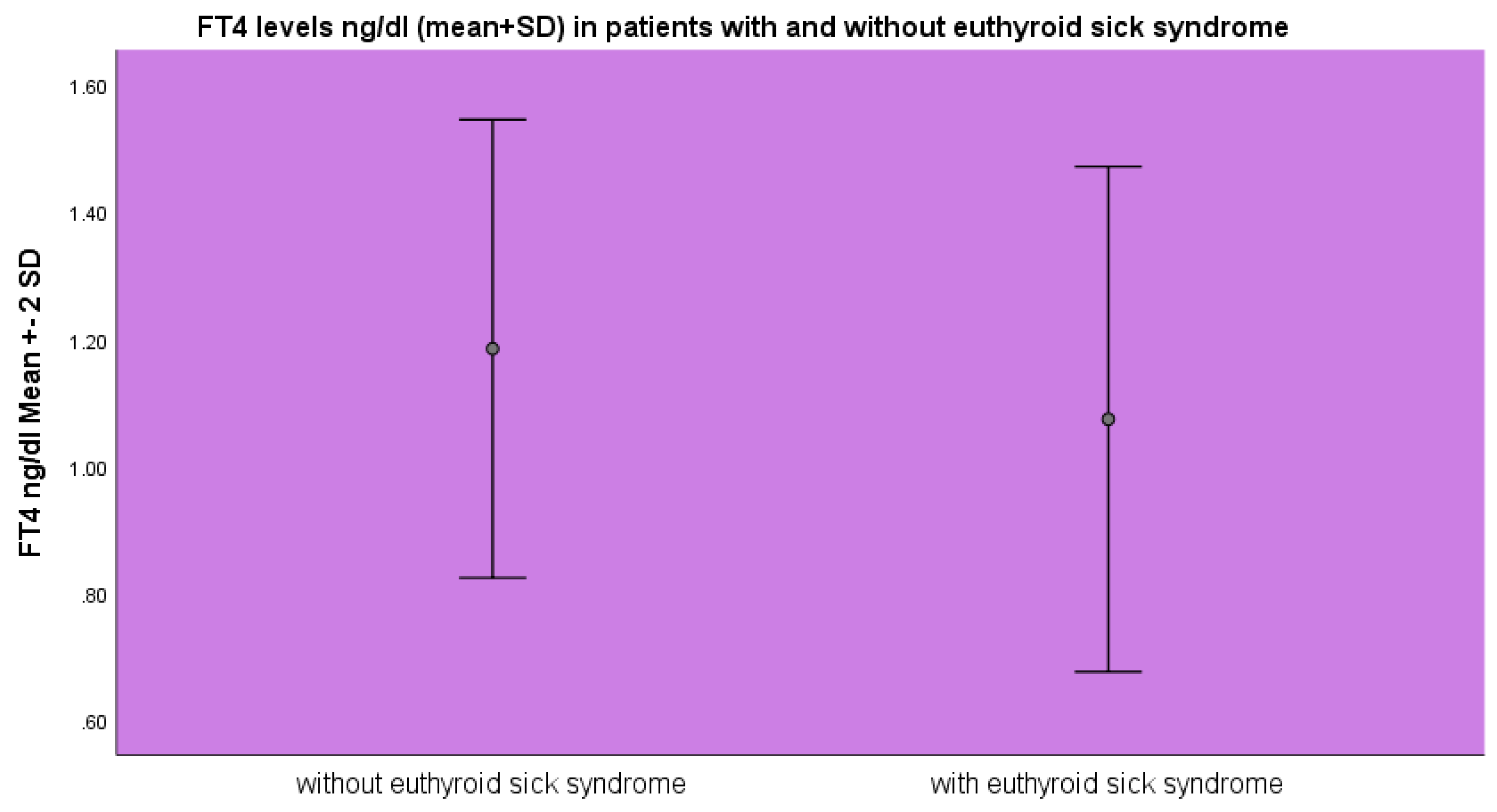

FT

4 levels were lower in the group of patients with euthyroid sick syndrome 1.07±0.19 ng/dl as opposed to 1.18±0.18 ng/dl (mean±SD, p<0.05 ANOVA) as opposed to the patients without euthyroid sick syndrome (

Figure 2).

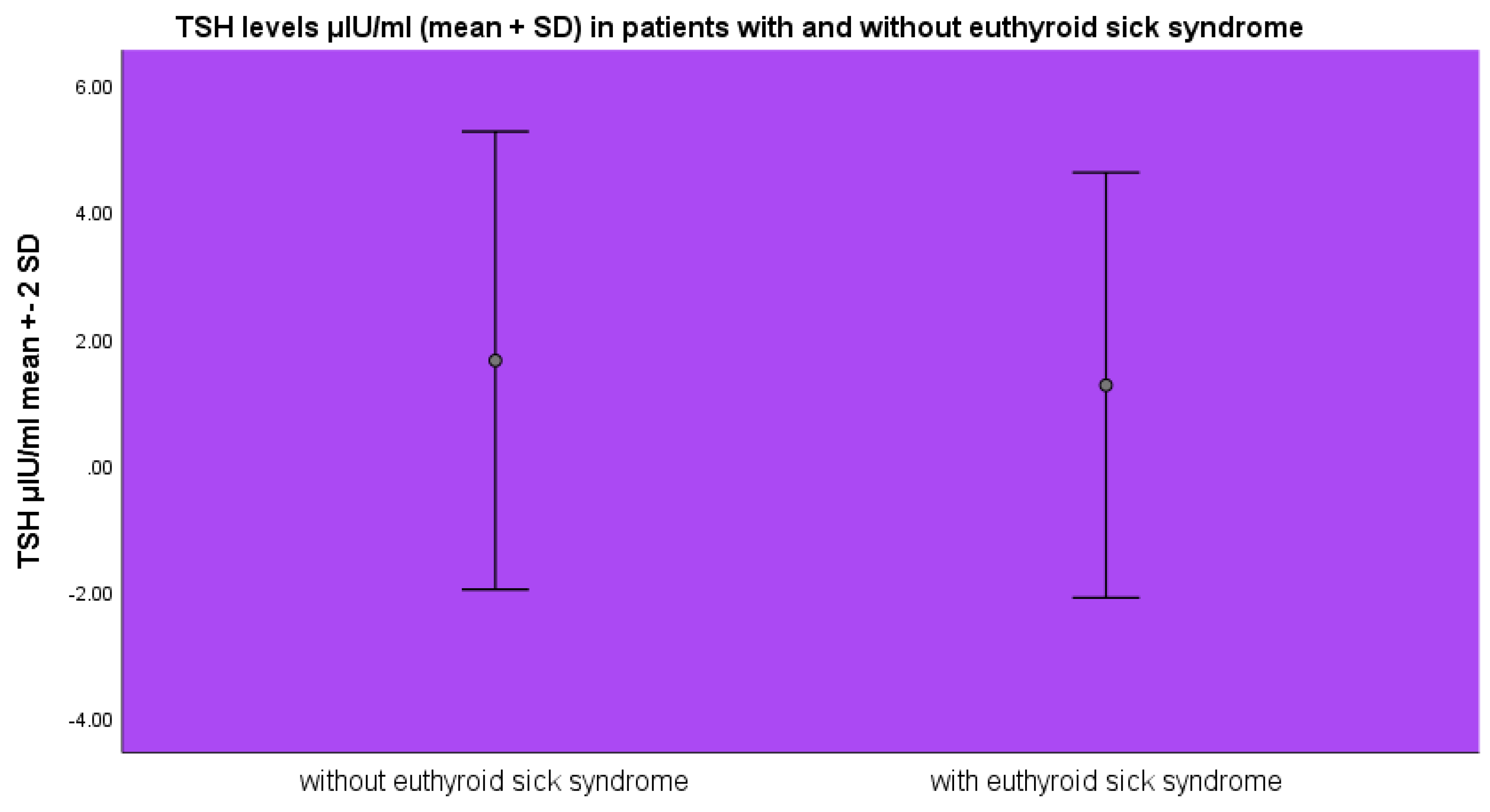

TSH levels were lower in the group of patients with euthyroid sick syndrome 1.26±1.68 μIU/ml as opposed to the patients without euthyroid sick syndrome 1.64±1.8 μIU/ml (mean±SD, p>0.05 ANOVA) (

Figure 3).

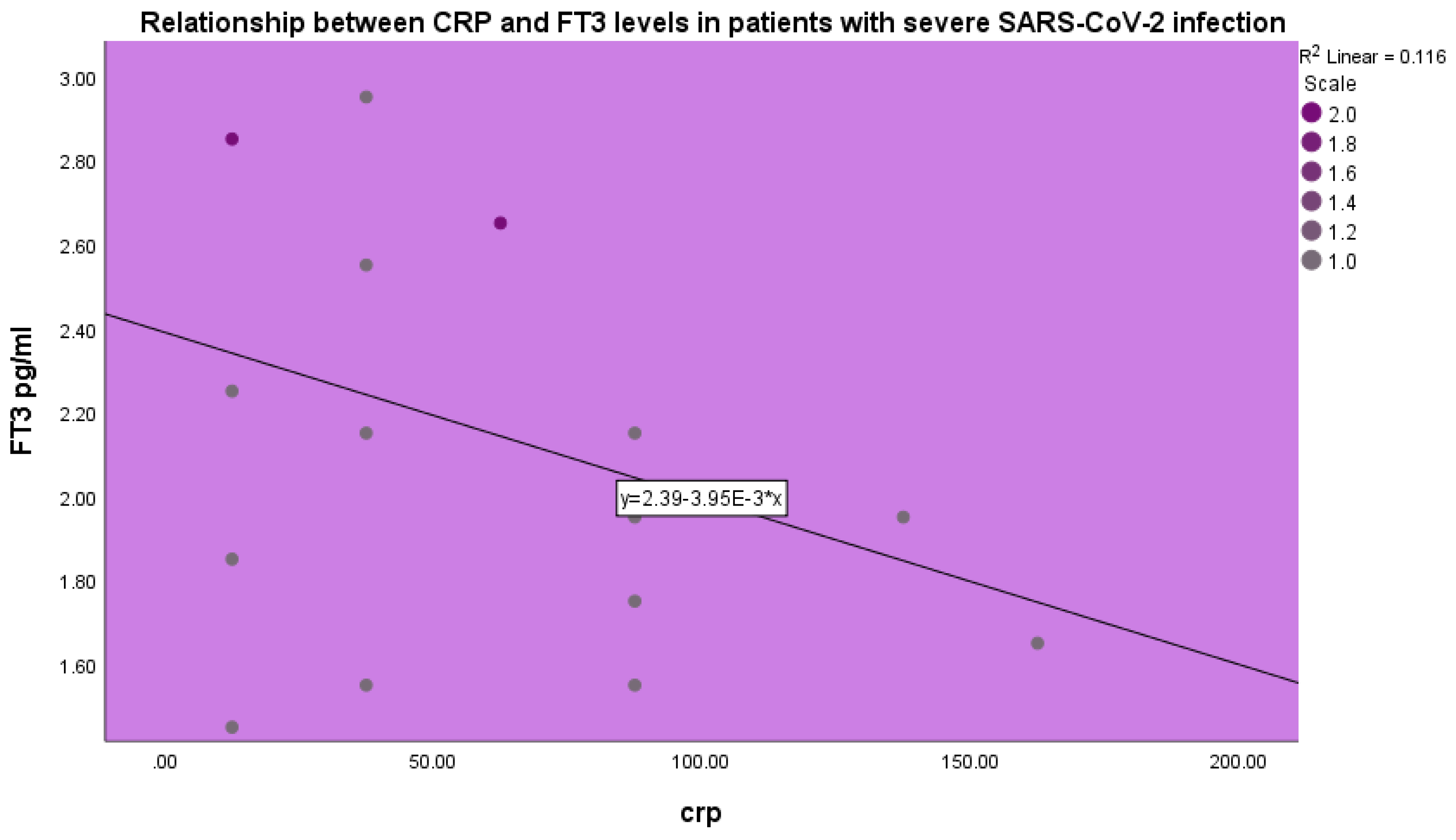

FT

3 levels were inversely related to CRP levels in patients with severe COVID-19 infection (p<0.001, beta coefficient of variation -0.34, linear regression analysis) (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Euthyroid sick syndrome or non-thyroidal illness syndrome presents the response of the organism to acute and severe illness [

2,

3]. In a state of acute illness, a patient may present with reduced levels of T

3 and normal or decreased TSH levels. By contrast, the levels of plasma rT

3 increase and levels of plasma T

4 are low or low-normal. These thyroid hormone alterations are observed at all age groups, ranging from the neonatal age, childhood to adulthood and old age [

12]. Severity of the underlying condition is in correlation to the euthyroid sick syndrome phenotype. Although euthyroid sick syndrome was described several years ago the pathophysiology of the condition remains incompletely understood and has not been as yet completely clarified. The pathophysiology of the condition is multifactorial. In acute disease thyroid hormones are inactivated peripherally. These changes, which are observed in the circulation, may represent a beneficial adaptation to illness aiming to the reduction of energy consumption and may induce immune response activation. Peripheral inactivation of thyroid hormones leads to activation of the innate immune response in order to enable survival [

32]. In the case of more severe and prolonged illness in addition to peripheral thyroid hormone changes the thyroid hormone axis is centrally suppressed leading to a more severe euthyroid hormone sick phenotype. In severe, critical and prolonged disease the presence of centrally suppressed thyroid hormone axis leads to aggravation of the euthyroid sick syndrome phenotype [

33]. Euthyroid sick syndrome is found in patients suffering from infectious diseases. It has been observed in ill children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome [

34] and severe disease course.

Euthyroid sick syndrome has been observed in patients with infection from the COVID-19 virus [

27]. In a retrospective study performed at the Sheba Medical Center in Israel [

35] it was found that in a cohort of COVID-19 patients those with FT

3 levels in the lower tertile had significantly higher mortality, need for mechanical ventilation and finally need for specialized acute care. In a clinical study performed in Changsha, China it was observed that non-thyroidal illness syndrome was related with severe disease and inflammatory parameters in COVID-19 disease [

27]. In an observational study performed in London thyroid function was evaluated in patients with COVID-19 infection [

36]. Patients with COVID-19 infection had decreased FT

4 and TSH levels, in comparison to baseline historical levels of the same patients, where available. Levels of FT

4 and TSH increased in the survivors after recovery from the infection. In a retrospective study performed in Lodz, Poland amongst patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection it was found that euthyroid sick syndrome was related with higher inflammatory indices, longer hospitalization and the need for oxygen therapy or intubation as compared to those without euthyroid sick syndrome [

37]. In the aforementioned study mortality was higher in those suffering from euthyroid sick syndrome and <50% of lung parenchymal involvement on computer tomography. In a prospective study of one year duration, performed in Florence, Italy in patients hospitalized with mild COVID-19 infection it was found that euthyroid sick syndrome, as depicted by decreased FT

3 levels was independently associated with poor outcome and death [

38]. In the aforementioned study euthyroid sick syndrome was the most frequent thyroid disorder in a population of patients with mild COVID-19 infection and was an index of adverse outcome [

38]. In a study performed in Italy Baldelli et al [

39] evaluated thyroid hormone levels in COVID-19 patients, a group with pneumonia and a group with respiratory distress syndrome and a group of controls and found significantly decreased FT

3 and TSH levels in the patient groups, the lower levels found in the respiratory distress group. In a large retrospective study performed in Kroatia in severe COVID-19 patients low TSH was observed. Sciacchitano et al [

40] studied patients with COVID-19 infection and hematological malignancies during the initial episodes of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Rome, Italy and they found that low FT

3 levels were related with increased neutrophil count, reduced T lymphocyte subpopulations and augmented inflammation, tissue damage and coagulation status. In the study reported herein low FT

3 and TSH levels were observed in severe COVID-19 infection. We found that euthyroid sick syndrome in our group of patients was significantly correlated with adverse outcome, i.e. non-survival or death. In accordance with our findings, Iervasi et al [

41] noted that euthyroid sick syndrome is a strong predictor of death in patients with heart disease. Cerillo et al [

42] also found that low T

3 syndrome may be a strong predictor of death in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery. We found that in our group of severe SARS-CoV-2 disease patients the presence of euthyroid sick syndrome was significantly related to disease severity and adverse outcome.

The pathophysiology of euthyroid sick or non-thyroidal illness syndrome is multifactorial and multifaceted. Severe illness induces major alterations in the thyroid axis at the hypothalamic and pituitary level. The thyroid hormone axis is centrally downregulated and induces a decrease in thyroid hormone secretion [

43]. The negative feedback regulation of the thyroid axis is impaired leading to low TSH levels and simultaneously low peripheral thyroid hormone levels. In accordance, diminished TRH gene expression was observed in the paraventricular nucleus in autopsy samples of patients with euthyroid sick syndrome related to antemortem low plasma TSH. In euthyroid sick syndrome changes in deiodinases type 1, 2 and 3 are observed which lead to increased deiodinase 2 activity in the hypothalamus causing increased T

4 to T

3 conversion and decreased TRH mRNA expression. Thyroid hormones exert their action after their transportation into the cell, where they undergo deiodination, either outer or inner ring, via the action of deiodinases, which are enzymes containing selenocysteine and are of three types, type 1, 2 and 3 known as D1, D2 and D3, respectively. D1 deiodinates the inner and outer rings of T

4 and the outer ring of rT

3 and is localized in the liver, the kidney, the thyroid and the hypophysis. D2 deiodinates T

4 to produce T

3 and is found in the endoplasmic reticulum. D3 inactivates thyroid hormones by producing inactive rT

3 and rT

2. Inflammation may inhibit hypothalamic TRH secretion via increased D2 activity. Decreased hepatic D1 mRNA activity during illness may contribute to disease induced alterations in the levels of T

3 and rT

3[

5]. Euthyroid sick syndrome may be a manifestation of the acute phase response. Various inflammatory cytokines released during inflammation may alter thyroid secretion and hormone metabolism44. In particular, increased circulating interleukin-6[

45] and TNF-α[

46], released during the acute phase response reduce T

4 metabolism to T

3 leading to the euthyroid sick profile. In SARS-CoV-2 infection an inflammatory cytokine release syndrome, described as “cytokine storm” may be observed which may be related to disease severity and even death [

47,

48]. The term cytokine storm describes the release of inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory mediators during an infectious disease which is related to rapid disease progression and mortality [

49]. The term was initially applied to describe graft versus host disease during allogeneic stem cell transplantation [

47]. Subsequently, the term cytokine storm was further elucidated and applied in various disease states as well as in sepsis [

50]. The aim of the immune system is the recognition of a foreign intruder in the organism and the formation of an inflammatory response in order to eliminate the foreign and possibly harmful agent. Its aim is also to support the repair of any damage induced by the foreign agent and in the end to return the organism to its initial basal condition. This response of the immune system is elaborated by cytokines, which are the means of communication of the immune cells between themselves as well as the coordination of various immune cells. There appears to be a complex system of regulatory processes which maintain an equlibrium between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and finally keep the immune response limited and balanced. If this balanced response of various mechanisms fails in one or more ways it may induce excessive immune activation and augmented cytokine production causing an inflammatory response which is not localized and may be systemic causing harm to the organism [

50]. The cytokine storm was shown to be characteristic of serious COVID-19 infection and it is characterized by augmented secretion of inflammatory cytokines and it is related to disease severity [

51]. The cytokine storm in COVID-19 disease is related to increased IL-6 and TNF-α expression [

52]. IL-6 is implicated in the pathogenesis of euthyroid sick syndrome [

53]. In acute myocardial infarction low FT

3, normal or low TSH and high IL-6 and its soluble receptor were observed. IL-6 elevation and euthyroid sick syndrome development were interconnected [

53]. Various data show a role of IL-6 in the interaction between thyroid axis and inflammatory mediators [

17]. In a clinical study, IL-6 levels were negatively correlated with FT3 and positively with rT

3[

43,

54]. It may thus be, that in the case of acute and serious SARS-CoV-2 disease the development of non-thyroidal illness syndrome may be linked to augmented inflammatory cytokine secretion [

55].

In our study we observed a negative correlation between CRP and FT

3 levels. CRP levels increase in acute infectious disease and are observed in acute COVID-19 infection [

56]. CRP levels characterize acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. CRP synthesis by the liver is induced by IL-6. Elevated CRP levels in acute SARS-CoV-2 infection are related to the cytokine storm and to disease severity [

56,

57]. Thus, in our study elevated CRP levels were found to be negatively related to FT

3 levels.

Treatment of euthyroid sick syndrome remains a hot topic generating discussion [

58]. Euthyroid sick syndrome may be considered an adaptive and energy preservation response [

17]. Various investigators have attempted to treat patients with euthyroid sick syndrome with thyroxine, with controversial results. Thyroxine administration in the acute care unit as an intravenous infusion normalized T

4 levels without affecting mortality [

59]. Various studies have examined the effect of therapeutic T

3 administration in adult patients with heart failure or coronary artery surgery. Other studies have shown promising whereas others less promising results [

60,

61]. T

3 administration for the preservation of organ function in brain dead donors has been attempted in order to preserve functionality in the organs to be transplanted [

62]. Combined treatment with GHRH, TRH and GnRH in male patients with critical disease has also been attempted [

63]. However, most researchers and clinicians agree that non-thyroidal illness syndrome should not be treated with thyroid drug administration [

64], as the syndrome improves in parallel with the underlying illness. Euthyroid sick syndrome or non-thyroidal illness syndrome represents a response to fasting in healthy individuals and is present in patients with acute severe illness [

65,

66]. However, euthyroid sick syndrome in the long term critically ill patients, where T

3, T

4 and TSH are low may represent a different facet of the disorder and may require treatment in order to prevent catabolic alterations within the organism [

33]. It is this particular group of patients that may benefit from treatment for euthyroid sick syndrome and may be the subjects to benefit from new or developing treatments for the disorder [

33,

63].

Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the world it became evident that the virus affected the thyroid gland as numerous cases of subacute thyroiditis were described in relationship with the infection [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Simultaneously, various cases of thyroiditis and autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis were described in association with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, new cases of Graves’ disease or exacerbation of previously stable Graves’ disease or Graves’ ophthalmopathy were described. Data emerged showcasing that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may be an autoimmune virus, i.e. a virus causing autoimmune diseases [

71]. The COVID-19 virus invades the thyroid gland via the ACE2 enzyme which the virus uses as a receptor and is expressed on thyroid cells. Prognosis of severe COVID-19 infection is a matter of interest in the current literature. Various indicators of severe disease and adverse outcome have been described, including vitamin D levels and kidney function parameters [

72,

73,

74]. Herein, we describe the association of severe SARS-CoV-2 disease with euthyroid sick or non-thyroidal illness syndrome. The presence of euthyroid sick syndrome was related to disease severity and death.

5. Conclusions

The SARS-CoV-2 virus swept over humanity and caused mild and severe disease. It caused a mild infection as well as severe pneumonia that could be lethal. The development of the cytokine storm, i.e. an inflammatory cascade was related to severe disease and adverse outcome. From early observations it was shown that the virus may affect the thyroid gland and may induce subacute thyroiditis. Various cases of subacute thyroiditis were described in the literature. Later on it was shown that the virus may also cause thyroiditis, autoimmune thyroiditis, hypothyroidism and Graves’ disease or exacerbation of previously quiescent Graves’ disease or Graves’ ophthalmopathy. In the present study we have provided evidence that patients hospitalized for severe SARS-CoV-2 disease may present with euthyroid sick syndrome or non-thyroidal illness syndrome or low T3 syndrome. The cytokine storm observed in severe SARS-CoV-2 disease may be related to the development of euthyroid sick syndrome. Data presented herein indicate that euthyroid sick syndrome in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 disease may be related to disease severity and appears to be an indicator of adverse prognosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A., I.K.-A., P.A., Y.S.; methodology, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; software, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; validation, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; formal analysis, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; investigation, , L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; resources, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; data curation, , L.A., I.K.-A.,G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, , L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; writing—review and editing, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; visualization, L.A., I.K.-A., G.K., S.N., A.K., O.M., C.S., C.S., P.A., Y.S.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, P.A.; funding acquisition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Asclepeion Hospital, Voula, Athens, Greece (approval number 15335, 24/11/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at the data archives of Asclepeion Hospital, Voula, Athens, Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- McIver, B.; Gorman, C.A. Euthyroid sick syndrome: an overview. Thyroid. 1997, 7, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliers, E.; Boelen, A. An update on non-thyroidal illness syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021, 44, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliers, E.; Bianco, A.C.; Langouche, L.; Boelen, A. Thyroid function in critically ill patients. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, R.P.; Wouters, P.J.; Kaptein, E.; van Toor, H.; Visser, T.J.; Van den Berghe, G. Reduced activation and increased inactivation of thyroid hormone in tissues of critically ill patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88, 3202–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, R.P.; van der Geyten, S.; Wouters, P.J.; et al. Tissue thyroid hormone levels in critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90, 6498–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nillni, E.A.; Vaslet, C.; Harris, M.; Hollenberg, A.; Bjørbak, C.; Flier, J.S. Leptin regulates prothyrotropin-releasing hormone biosynthesis. Evidence for direct and indirect pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 36124–36133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, E.A.; Klibanski, A. Endocrine abnormalities in anorexia nervosa. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008, 4, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennemann, G.; Krenning, E.P. The kinetics of thyroid hormone transporters and their role in non-thyroidal illness and starvation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 21, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douyon, L.; Schteingart, D.E. Effect of obesity and starvation on thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and cortisol secretion. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002, 31, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, F.W., 2nd; Brown, P.S., Jr.; Weintraub, B.D.; Clark, R.E. Cardiopulmonary bypass and thyroid function: a "euthyroid sick syndrome". Ann Thorac Surg. 1991, 52, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, T.J.; Wechsler, A.S. Triiodothyronine in cardiac surgery. Thyroid. 1997, 7, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Farwell, A.P. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome. Compr Physiol. 2016, 6, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistal-Nuño, B. Euthyroid sick syndrome in paediatric and adult patients requiring extracorporeal circulatory support and the role of thyroid hormone supplementation: a review. Perfusion. 2021, 36, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauteruccio, M.; Vitiello, R.; Perisano, C.; Covino, M.; Sircana, G.; Piccirillo, N.; Pesare, E.; Ziranu, A.; Maccauro, G. Euthyroid sick syndrome in hip fractures: Evaluation of postoperative anemia. Injury. Aug 2020, 51 (Suppl. 3), S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.Y.; Yi, M.; Li, W.G.; Ye, H.Y.; Chen, Z.S.; Zhang, X.D. The prevalence, hospitalization outcomes and risk factors of euthyroid sick syndrome in patients with diabetic ketosis/ketoacidosis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023, 23, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, T.; Topaloglu, O.; Altunoglu, A.; Neselioglu, S.; Erel, O. Frequency of Euthyroid Sick Syndrome before and after renal transplantation in patients with end stage renal disease and its association with oxidative stress. Postgrad Med. 2022, 134, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, T.A.; Vagenakis, A.G.; Alevizaki, M. The nonthyroidal illness syndrome in the non-critically ill patient. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011, 41, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Brinker, M.; Joosten, K.F.; Visser, T.J.; et al. Euthyroid sick syndrome in meningococcal sepsis: the impact of peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism and binding proteins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90, 5613–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataoğlu, H.E.; Ahbab, S.; Serez, M.K.; et al. Prognostic significance of high free T4 and low free T3 levels in non-thyroidal illness syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2018, 57, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, J.; Sorg, O.; Horn, T.F.; et al. Inflammatory cytokines: putative regulators of neuronal and neuro-endocrine function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998, 26, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQahtani, A.; Alakkas, Z.; Althobaiti, F.; et al. Thyroid Dysfunction in Patients Admitted in Cardiac Care Unit: Prevalence, Characteristic and Hospitalization Outcomes. Int J Gen Med. 2021, 14, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, M.J.; Torpy, D.J. Thyroid Hormones in Critical Illness. Crit Care Clin. 2019, 35, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, W.; Dong, R.; Liu, N.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y. Predictors for euthyroid sick syndrome and its impact on in-hospital clinical outcomes in high-risk patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Perfusion. 2019, 34, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.C.; Mak, T.W.; Chan, C.H.; Cockram, C.S. Euthyroid sick syndrome in pulmonary tuberculosis before and after treatment. Ann Clin Biochem. 1995, 32 Pt 4, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, L.K.; Dutta, D.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Thyroid Dysfunction in Patients with HIV Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome: An Indian Perspective. J Thyroid Res. 2015, 2015, 517173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, F.A.; Soule, S.G.; Willcox, P.A.; Levitt, N.S. The spectrum of endocrine dysfunction in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994, 40, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome in Patients With COVID-19. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020, 11, 566439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvent, M.; Maestro, S.; Hernández, R.; et al. Euthyroid sick syndrome, associated endocrine abnormalities, and outcome in elderly patients undergoing emergency operation. Surgery. 1998, 123, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opasich, C.; Pacini, F.; Ambrosino, N.; et al. Sick euthyroid syndrome in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1996, 17, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, K.S.; Osmonov, D.; Toprak, E.; et al. Sick euthyroid syndrome is associated with poor prognosis in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous intervention. Cardiol J. 2014, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, R. [Related factors of euthyroid sick syndrome in patients with sepsis]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2024, 56, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langouche, L.; Jacobs, A.; Van den Berghe, G. Nonthyroidal Illness Syndrome Across the Ages. J Endocr Soc. 2019, 3, 2313–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berghe, G. Non-thyroidal illness in the ICU: a syndrome with different faces. Thyroid. 2014, 24, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastiggi, M.; Meneghel, A.; Gutierrez de Rubalcava Doblas, J.; et al. Prognostic role of euthyroid sick syndrome in MIS-C: results from a single-center observational study. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1217151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, Y.; Percik, R.; Oberman, B.; Yaffe, D.; Zimlichman, E.; Tirosh, A. Sick Euthyroid Syndrome on Presentation of Patients With COVID-19: A Potential Marker for Disease Severity. Endocr Pract. 2021, 27, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, B.; Tan, T.; Clarke, S.A.; et al. Thyroid Function Before, During, and After COVID-19. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 106, e803–e811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świstek, M.; Broncel, M.; Gorzelak-Pabiś, P.; Morawski, P.; Fabiś, M.; Woźniak, E. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome as a Prognostic Indicator of COVID-19 Pulmonary Involvement, Associated With Poorer Disease Prognosis and Increased Mortality. Endocr Pract. 2022, 28, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparano, C.; Zago, E.; Morettini, A.; et al. Euthyroid sick syndrome as an early surrogate marker of poor outcome in mild SARS-CoV-2 disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022, 45, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, R.; Nicastri, E.; Petrosillo, N.; et al. Thyroid dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021, 44, 2735–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacchitano, S.; De Vitis, C.; D'Ascanio, M.; et al. Gene signature and immune cell profiling by high-dimensional, single-cell analysis in COVID-19 patients, presenting Low T3 syndrome and coexistent hematological malignancies. J Transl Med. 2021, 19, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervasi, G.; Pingitore, A.; Landi, P.; et al. Low-T3 syndrome: a strong prognostic predictor of death in patients with heart disease. Circulation. 2003, 107, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerillo, A.G.; Storti, S.; Kallushi, E.; et al. The low triiodothyronine syndrome: a strong predictor of low cardiac output and death in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014, 97, 2089–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, A.; Kwakkel, J.; Fliers, E. Beyond low plasma T3: local thyroid hormone metabolism during inflammation and infection. Endocr Rev. 2011, 32, 670–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, E.M.; Kwakkel, J.; Eggels, L.; et al. NFκB signaling is essential for the lipopolysaccharide-induced increase of type 2 deiodinase in tanycytes. Endocrinology. 2014, 155, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajner, S.M.; Goemann, I.M.; Bueno, A.L.; Larsen, P.R.; Maia, A.L. IL-6 promotes nonthyroidal illness syndrome by blocking thyroxine activation while promoting thyroid hormone inactivation in human cells. J Clin Invest. 2011, 121, 1834–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feelders, R.A.; Swaak, A.J.; Romijn, J.A.; et al. Characteristics of recovery from the euthyroid sick syndrome induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha in cancer patients. Metabolism. 1999, 48, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanza, C.; Romenskaya, T.; Manetti, A.C.; et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: Immunopathogenesis and Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, B.; Mao, J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the `Cytokine Storm' in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020, 80, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousterman, B.G.; Swirski, F.K.; Weber, G.F. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulert, G.S.; Grom, A.A. Pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome and potential for cytokine- directed therapies. Annu Rev Med. 2015, 66, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Murakami, M. COVID-19: A New Virus, but a Familiar Receptor and Cytokine Release Syndrome. Immunity. 2020, 52, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Kanda, T.; Kotajima, N.; Kuwabara, A.; Fukumura, Y.; Kobayashi, I. Involvement of circulating interleukin-6 and its receptor in the development of euthyroid sick syndrome in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000, 143, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, A.; Platvoet-ter Schiphorst, M.C.; Bakker, O.; Wiersinga, W.M. The role of cytokines in the lipopolysaccharide-induced sick euthyroid syndrome in mice. J Endocrinol. 1995, 146, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, R.; Sharma, B.R.; Tuladhar, S.; et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ Triggers Inflammatory Cell Death, Tissue Damage, and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cytokine Shock Syndromes. Cell. 2021, 184, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.Y.; Yin, C.H.; Yao, Y.M. Update Advances on C-Reactive Protein in COVID-19 and Other Viral Infections. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 720363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molins, B.; Figueras-Roca, M.; Valero, O.; et al. C-reactive protein isoforms as prognostic markers of COVID-19 severity. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathatos, N.; Wartofsky, L. The euthyroid sick syndrome: is there a physiologic rationale for thyroid hormone treatment? J Endocrinol Invest. 2003, 26, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, G.A.; Hershman, J.M. Thyroxine therapy in patients with severe nonthyroidal illnesses and low serum thyroxine concentration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis-Jansson, S.L.; Argenziano, M.; Corwin, S.; et al. A randomized double-blind study of the effect of triiodothyronine on cardiac function and morbidity after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999, 117, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore, A.; Nicolini, G.; Kusmic, C.; Iervasi, G.; Grigolini, P.; Forini, F. Cardioprotection and thyroid hormones. Heart Fail Rev. 2016, 21, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goarin, J.P.; Cohen, S.; Riou, B.; et al. The effects of triiodothyronine on hemodynamic status and cardiac function in potential heart donors. Anesth Analg. 1996, 83, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, G. Growth hormone secretagogues in critical illness. Horm Res. 1999, 51 (Suppl. 3), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalena, L. The dilemma of non-thyroidal illness syndrome: to treat or not to treat? J Endocrinol Invest 2003, 12, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, A.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Fliers, E. Fasting-induced changes in the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Thyroid. 2008, 18, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, M.E.; de Jong, M.; Lim, C.F.; et al. Different regulation of thyroid hormone transport in liver and pituitary: its possible role in the maintenance of low T3 production during nonthyroidal illness and fasting in man. Thyroid. 1996, 6, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; O'Callaghan, K.; Sinclair, H.; et al. Risk factors, treatment and outcomes of subacute thyroiditis secondary to COVID-19: a systematic review. Intern Med J. 2022, 52, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Resuli, A.; Bezgal, M. Subacute Thyroiditis in COVID-19 Patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2022, 101, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabpour, S.; Heidari, F.; Karimi, E.; Ansari, R.; Tajdini, A. Subacute Thyroiditis in COVID-19 Patients. Eur Thyroid J. 2021, 9, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, K.; Odermatt, J.; Ziaka, M.; Rudovich, N. Subacute Thyroiditis Complicating COVID-19 Infection. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. © The Author(s) 2023. 2023, 11795476231181560.

- Dotan, A.; Muller, S.; Kanduc, D.; David, P.; Halpert, G.; Shoenfeld, Y. The SARS-CoV-2 as an instrumental trigger of autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2021, 20, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, D.; Lopes-Pacheco, M.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.C.; Pelosi, P.; Rocco, P.R.M. Laboratory Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 857573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de La Flor, J.C.; Gomez-Berrocal, A.; Marschall, A.; et al. The impact of the correction of hyponatremia during hospital admission on the prognosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Med Clin (Barc). 2022, 159, 12–18, Impacto de la corrección temprana de la hiponatremia en el pronóstico de la infección del síndrome respiratorio agudo grave del coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiodini, I.; Gatti, D.; Soranna, D.; et al. Vitamin D Status and SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19 Clinical Outcomes. Front Public Health. 2021, 9, 736665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).