Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessments

2.6. Effect Measures

3. Results

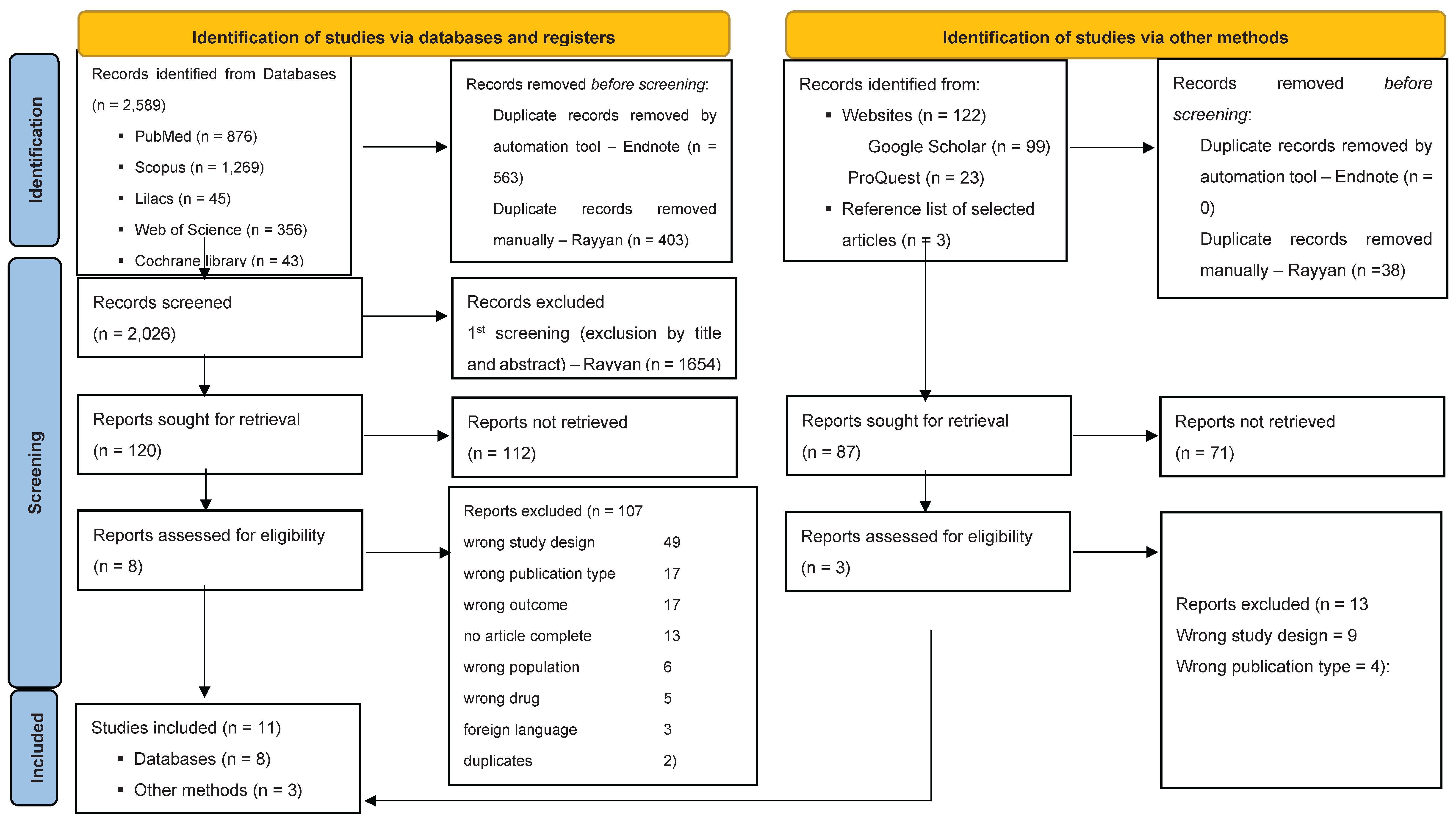

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

6.1. Recommendations for Future Primary Studies

Supplementary Materials

Protocol and registration

Acknowledgments

Funding

Competing Interests

Author Contributions

Ethical approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68(6):394-424. Epub 2018 Sep 12. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jul;70(4):313. [CrossRef]

- Caribé-Gomes F, Chimenos-Küstner E, López-López J, Finestres-Zubeldia F, Guix-Melcior B. Dental management of the complications of radio and chemotherapy in oral cancer. Med Oral. 2003 May-Jul;8(3):178-87. English, Spanish.

- Mosel DD, Bauer RL, Lynch DP, Hwang ST. Oral complications in the treatment of cancer patients. Oral Dis. 2011;17:550-9.

- Epstein, JB., Hong, C., Logan, RM., Barasch, A., Gordon, SM., Oberlee-Edwards, L. A systematic review of orofacial pain in patients receiving cancer therapy. Support Care Cancer, 2012; 18:1023–1031.

- Burlage, FR., Coppes, RP., Meertens, H., Stokman, MA., & Vissink, A. Parotid and submandibular/sublingual salivary flow during high dose radiotherapy. Radiation Oncology, 2001; 61:271–274.

- Almståhl, A., Finizia, C., Carlén, A., Fagerberg-Mohlin, B., & Alstad, T. Explorative study on mucosal and major salivary secretion rates, caries and plaque microflora in head and neck cancer patients. International Journal of Dental Hygiene, 2018; 16:450–458.

- Moon, DH., Moon, SH., Wang, K., Weissler, MC., Hackman, TG., Zanation, A. M. Incidence of, and risk factors for, mandibular osteoradionecrosis in patients with oral cavity and oropharynx cancers. Oral Oncology, 2017; 72:98–103.

- Pauli, N., Johnson, J., Finizia, C., Andréll, P. The incidence of trismus and long-term impact on health-related quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Acta Oncologica, 2013; 52:1137–1145.

- De Sanctis, V., Bossi, P., Sanguineti, G., Trippa, F., Ferrari, D., Bacigalupo, A. Mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and systemic therapies: Literature review and consensus statements. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 2016; 100:147–166.

- Jensen, S. B., Jarvis, V., Zadik, Y., Barasch, A., Ariyawardana, A., Hovan, A. Systematic review of miscellaneous agents for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer, 2013; 21:3223–3232.

- Lanzós, I., Herrera, D., Lanzós, E., Sanz, M. A critical assessment of oral care protocols for patients under radiation therapy in the regional University Hospital Network of Madrid. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry, Spain, 2015; 27: 613–621.

- Nuñez-Aguilar J, Fernández-Olavarría A, Oliveros-López LG, Torres-Lagares D, Serrera-Figallo MA, Gutiérrez-Corrales A, Gutiérrez-Pérez JL. Evolution of oral health in oral cancer patients with and without dental treatment in place: Before, during and after cancer treatment. J Clin Exp Dent. 2018; 1,10(2):158-165. [CrossRef]

- Niewald M, Fleckenstein J, Mang K, Holtmann H, Spitzer WJ, Rübe C. Dental status, dental rehabilitation procedures, demographic and oncological data as potential risk factors for infected osteoradionecrosis of the lower jaw after radiotherapy for oral neoplasms: a retrospective evaluation. Radiat Oncol. 2013 Oct 2;8:227. [CrossRef]

- Bueno AC, Ferreira RC, Barbosa FI, Jham BC, Magalhães CS, Moreira AN. Periodontal care in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013 Apr; 21(4):969-75.

- Regezi JA, Courtney RM, Kerr DA. Dental management of patients irradiated for oral cancer. Cancer 1976; 38: 994- 1000.

- Stokman MA, Burlage FR, Spijkervet FK. The effect of a calcium phosphate mouth rinse on (chemo) radiation induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012 Aug;10(3):175-80. [CrossRef]

- Kazemian A, Kamian S, Aghili M, Hashemi FA, Haddad P. Benzydamine for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancers: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009 Mar;18(2):174-8. [CrossRef]

- Satheeshkumar PS, Chamba MS, Balan A, Sreelatha KT, Bhatathiri VN, Bose T. Effectiveness of triclosan in the management of radiation-induced oral mucositis: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010 Oct-Dec;6(4):466-72.

- Samaranayake LP, Robertson AG, MacFarlane TW, Hunter IP, MacFarlane G, Soutar DS, Ferguson MM. The effect of chlorhexidine and benzydamine mouthwashes on mucositis induced by therapeutic irradiation. Clin Radiol. 1988 May;39(3):291-4. [CrossRef]

- Epstein JB, Silverman S Jr, Paggiarino DA, Crockett S, Schubert MM, Senzer NN, Lockhart PB, Gallagher MJ, Peterson DE, Leveque FG. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis: results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cancer. 2001 Aug 15;92(4):875-85.

- Leenstra JL, Miller RC, Qin R, Martenson JA, Dornfeld KJ, Bearden JD, Puri DR, Stella PJ, Mazurczak MA, Klish MD, Novotny PJ, Foote RL, Loprinzi CL. Doxepin rinse versus placebo in the treatment of acute oral mucositis pain in patients receiving head and neck radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a phase III, randomized, double-blind trial (NCCTG-N09C6 [Alliance]). J Clin Oncol. 2014 May 20;32(15):1571-7. Epub 2014 Apr 14. [CrossRef]

- Sio TT, Le-Rademacher JG, Leenstra JL, Loprinzi CL, Rine G, Curtis A, Singh AK, Martenson JA Jr, Novotny PJ, Tan AD, Qin R, Ko SJ, Reiter PL, Miller RC. Effect of Doxepin Mouthwash or Diphenhydramine-Lidocaine-Antacid Mouthwash vs. Placebo on Radiotherapy-Related Oral Mucositis Pain: The Alliance A221304 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Apr 16;321(15):1481-1490. [CrossRef]

- Epstein JB, Güneri P, Barasch A. Appropriate and necessary oral care for people with cancer: guidance to obtain the right oral and dental care at the right time. Support Care Cancer. 2014 Jul;22(7):1981-8. Epub 2014 Mar 28. [CrossRef]

- Huang BS, Wu SC, Lin CY, Fan KH, Chang JT, Chen SC. The effectiveness of a saline mouth rinse regimen and education programme on radiation-induced oral mucositis and quality of life in oral cavity cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018 Mar;27(2).

- Bonnaure-Mallet M, Bunetel L, Tricot-Doleux S, Guérin J, Bergeron C, LeGall E. Oral complications during treatment of malignant diseases in childhood: effects of tooth brushing. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34:1588–91.

- Meurman JH, Grönroos L. Oral and dental health care of oral cancer patients: hyposalivation, caries and infections. Oral Oncol. 2010 Jun; 46(6):464-7. Epub 2010 Mar 21. [CrossRef]

- Antunes H, Ferreira E, Faria L, Schirmer M, Rodrigues PC, Small I, et al. Streptococcal bacteraemia in patients submitted to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the role of tooth brushing and use of chlorhexidine. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010; 15:303–9.

- Autio-Gold J. The role of chlorhexidine in caries prevention. Oper Dent 2008; 33:710–6.

- Hancock PJ, Epstein JB, Sadler GR. Oral and dental management related to radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003 Oct;69(9):585-90.

- Foote RL, Loprinizi CL, Frank AR, O’Fallon JR, Gulavita S, Twefik HH, and others. Randomized trial of a chlorhexidine mouthwash for alleviation of radiation-induced mucositis. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12(12):2630–3.

- Laine P, Meurman JH, Murtomaa H, Lindqvist C, Torkko H, Pyrhönen S, et al. One-year trial of the effect of rinsing with an amine fluoride–stannous– fluoride-containing mouthwash on gingival index scores and salivary microbial counts in lymphoma patients receiving cytostatic drugs. J Clin Periodontol 1993; 20:628–34.

- Sudoh Y, Cahoon EE, Gerner P, Wang GK. Tricyclic antidepressants as long-acting local anesthetics. Pain. 2003;103(1-2):49-55. [CrossRef]

- Epstein JB, Chin EA, Jacobson JJ, Rishiraj B, Le N. The relationships among fluoride, cariogenic oral flora, and salivary flow rate during radiation therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998; 86:286–92.

- Meyerowitz C, Watson 2nd GE. The efficacy of an intraoral fluoride-releasing system in irradiated head and neck cancer patients: a preliminary study. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129:1252–9.

- Epstein JB, van der Meij EH, Lunn R, Stevenson-Moore P. Effects of compliance with fluoride gel application on caries and caries risk in patients after radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996; 82:268–75.

- Mourad Ouzzani, Hossam Hammady, Zbys Fedorowicz, and Ahmed Elmagarmid. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews (2016) 5:210. [CrossRef]

- Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Mu P (2020) Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. [CrossRef]

- Lalla RV, Bowen J, Barasch A, Elting L, Epstein J, Keefe DM, McGuire DB, Migliorati C, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Peterson DE, Raber-Durlacher JE, Sonis ST, Elad S; Mucositis Guidelines Leadership Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO). MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer. 2014 May 15;120(10):1453-61. [CrossRef]

- Elad S, Cheng KKF, Lalla RV, Yarom N, Hong C, Logan RM, Bowen J, Gibson R, Saunders DP, Zadik Y, Ariyawardana A, Correa ME, Ranna V, Bossi P; Mucositis Guidelines Leadership Group of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO). MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer. 2020 Oct 1;126(19):4423-4431. [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2021) Head and neck cancers (Version3.2021). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation OPEN ACCESS. BMJ. [CrossRef]

- Cuzzullin MC, Pérez-de-Oliveira, Normando AGC, Santos-Silva AR, Prado-Ribeiro, AC (2021) Basic oral care in cancer patients: a systematic review. In: PROSPERO CRD42022319455 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022319455.

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 372:n160–n160. [CrossRef]

|

Trial design and identification |

- Identification as randomized clinical trial and description of the trial design. - Provide the medical center where the patients were treated. |

|---|---|

|

Ethics and registration |

- Provide Center or city ethics committee - Ensure that the trial is registered in a publicly-accessible trials register database |

|

Population |

- Describe oncological treatment patients are being submitted (such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, stem cell transplant). - Detail the eligibility criteria and sample size. - Define the control group: placebo, different protocols or another reference treatment. - Include procedures for randomization, patients’ allocation and patient-blinding. |

|

Oral care intervention |

- Specific description of the oral care procedure, such as toothbrush used, mouth rising used and concentration, prophylaxis, dental floss type, fluor application - The moment performed said procedures, before, during or after the oncological treatment - Duration taken and technique to perform the procedures |

| Author, year | Condition | Moment of the dental intervention | Dental intervention | Main Results | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein, 2001 Kazemian, 2009 |

Mucositis Mucositis |

Before, during and after the oncologic treatment Before and during the oncologic treatment |

Benzydamine (to rinse 1.5 mg/mL benzydamine [15mL] for 2 minutes, 4 – 8 times daily before and during RT, and for 2 weeks after completion of RT and a Control group - placebo (excipients included approximately 10% alcohol by volume, menthol, peppermint oil, clove oil, and other flavoring agents). Benzydamine (to rinse with 15 ml of 0.15% for 2 min, 4 times a day from the first day of RT to the end of the treatment.) |

Benzydamine produced a 26.3% reduction in mean mucositis compared with placebo for the overall 0 –5000-cGy interval (P 5=0.009). Subjects receiving conventional RT with or without chemotherapy, the mean of mucositis scores showed a 30% reduction in erythema and ulceration with benzydamine over the cumulative RT interval of 0 –5000 cGy compared with placebo (P 5=0.006). Also, benzydamine produced statistically significant reductions in mucositis in the highest two RT intervals compared with placebo: 36% in the 2500 –3750-cGy interval (P=. 0.001) and 25.3% in the 3750 –5000-cGy interval (P 5 0.006). In addition, a prophylactic effect of benzydamine on oral mucositis was significant, mucositis scores in oropharyngeal areas at risk for ulceration in both treatment groups remained in the 0 –1 range (no ulceration) at cumulative RT exposures of 3750 and 5000 cGy. Smoking before and during RT (P= 0.008), chemoradiation (P = 0.002), and receiving benzydamine (P = 0.001) significantly affected the grade of mucositis at the end of the treatment. Benzydamine produced a statistically significant reduction in mucositis during RT. There was a statistically significant difference in the grade 3 mucositis in the two groups, which was 43.6% (n = 17) in the benzydamine group and 78.6% (n = 33) in the placebo group (P = 0.001). Grade 3 mucositis was 2.6 times more frequent in the placebo group (relative risk = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.38–5). Smoking cigarettes significantly reduced the incidence of mucositis grade 3 (P = 0.01; relative risk = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.29–0.81). Also, chemoradiation significantly increased the incidence of this parameter. |

The use of benzydamine 0.15% oral rinse is significant as a routine prophylactic in patients with head and neck carcinoma receiving a variety of RT regimens. Benzydamine 0.15% oral rinse was safe and well tolerated. It significantly reduced RT-induced mucositis, which also decreased the interruption of the treatment by the patients. The prophylactic usage of this local medication may decrease the mucosal complications of RT and therefore increase local tumor control. |

||

| Control group - Placebo | |||||||

|

Leenstra, 2014 Samarannayake, 1988 |

Mucositis Mucositis |

During the oncologic treatment During the oncologic treatment |

Doxepin (to rinse with a solution of doxepin 25mg, diluted to 5mL with 2.5 mL of sterile or distilled water. Control group - placebo rinse prepared in a similar manner) Both groups, the patients swished the solution in their mouth for 1minute, gargled, and expectorated. Chlorhexidine [to rinse with 15ml of 0.2% w/v aqueous chlorhexidine gluconate (Hibitane-ICI Pharmaceuticals) for 30 s twice daily] |

The mean mouth and throat pain reduction was greater for doxepin (-9.1) compared with placebo (-4.7; difference, -4.4; 95% CI, -6.7 to -2.1; P <.001). Crossover analysis of the two phases showed intrapatient changes of 4.1 for the doxepin-placebo arm and -2.8 for the placebo-doxepin arm; the treatment difference of doxepin versus placebo was -3.5. Which means an average mouth and throat pain score reduction of -2.0 (36.3%) from baseline for doxepin compared with -1.0 (18.9%) for placebo at 30 minutes after rinse (P =.0032). However, the crossover data in the second phase also confirmed that doxepin had more stinging and burning and worse taste and also caused more drowsiness (P =.0297). The yeast carriage rate was significantly higher than the coliform carriage rate in both groups (p < 0.05). The most common coliform found was Klebsiella pneumoniae. Patients using chlorhexidine presented less discomfort. The loss of weight in the control group was four times higher than the study group. The difference noted was highly significant (t=3.73; df = 22; P<0.01). |

Doxepin rinse is statistically significantly superior to a placebo in treating oral mucositis pain from head and neck radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. However, further study is warranted to fully elucidate the use of this doxepin rinse in this setting. Patients’ acceptance of chlorhexidine Is better than benzydamine but there is a little difference between the two mouthwashes both in controlling pain and mucositis or in the oral carriage of the microorganisms studied. |

||

| Benzydamine [to rinse with 15 ml of 0.15% w/v benzydamine hydrochloride ('Difflam', Carnegie Medical] |

|||||||

|

Satheeshkumar, 2010 |

Mucositis |

During the oncologic treatment |

Triclosan mouth rinse [to rinse with M/S Colgate Palmolive India Ltd (Colgate Plax) containing triclosan 0.03% W/V] |

From grade 2-3, there was no statistical difference between the study and control groups (P>0.05). One patient (8%) in the study group and 10 patients (83%) in the control group progressed on to grade 4 mucositis. The effect of treatment in control of severity of mucositis was tested statistically by Chi square test and was found significant at a very higher level (P<0.001). With regard to reversal of mucositis from grade 3 to grade 0, the study group had taken only a mean of 23.6 days in place of 36.5 days in the control group. The Students′ test was significant at 5% level (P<0.05). When considering the time taken for shifting from liquid to semisolid, it was 14.18 days in the study group and 27.17 days in the control group (P<0.05). The time taken to resume solid food from liquid was 25.1 days in the study group and 44.67 days in the control group respectively (P<0.01). |

The calcium phosphate mouth rinse seems to have no influence on the frequency, duration and severity of oral mucositis during CRT in patients with head and neck cancer. |

||

| Control group - Sodium bicarbonate (2 g of sodium bicarbonate powder) | |||||||

|

Sio, 2019 Stockman, 2012 |

Mucositis Mucositis |

During the oncologic treatment During the oncologic treatment |

Doxepin (92 patients to rinse with randomized to doxepin mouthwash [25 mg/5 mL water]; 91 patients to diphenhydramine-lidocaine-antacid; and 92 patients to placebo). Calcium phosphate (to rinse twice with 15 ml solution for 1 min, four times a day) |

Mucositis pain during the first 4 hours decreased by 11.6 points in the doxepin mouthwash group, by 11.7 points in the diphenhydramine-lidocaine-antacid mouthwash group, and by 8.7 points in the placebo group. The between-group difference was 2.9 points (95% CI, 0.2-6.0; P = .02) for doxepin mouthwash vs. placebo and 3.0 points (95% CI, 0.1-5.9; P = .004) for diphenhydramine-lidocaine-antacid mouthwash vs. placebo. More drowsiness was reported with doxepin mouthwash vs. placebo (by 1.5 points [95% CI, 0-4.0]; P = .03), unpleasant taste (by 1.5 points [95% CI, 0-3.0]; P = .002), and stinging or burning (by 4.0 points [95% CI, 2.5-5.0]; P < .001). The mean weight loss after 6 weeks of radiation was 4.0 kg (SD 3.7) in the CP mouth rinse group and in the control group 3.5 kg (SD 3.1) (P = 0.7). Use of gastric tubes was necessary in 12 of the 25 patients in the CP mouth rinse group (55%) and in six of the 11 patients in the control group (48%) (P = 0.8). No significant difference was found for oral pain between both groups. |

The use of doxepin mouthwash or diphenhydramine-lidocaine-antacid mouthwash vs. placebo significantly reduced oral mucositis pain during the first 4 hours after administration. | ||

| Control group - salt/baking soda solution (1 tsp. of salt and 1 tsp. of baking soda in a liter of tap water) at least eight times a day to remove sticky saliva and debris. | The CP mouth rinse seems to have no influence on the frequency, duration and severity of oral mucositis during (chemo) radiation in patients with head and neck cancer. | ||||||

|

Bueno, 2013 |

Biofilm |

Prior to the oncologic treatment |

1. Oral hygiene instructions included instruction on brushing and interdental cleaning, 2. coronal scaling (using an ultrasonic instrument), and polishing, 3. a kit containing a toothbrush and toothpaste. 4. The patients were prescribed 1 % neutral fluoride solution to be used once daily; designed to prevent caries and postoperative sensitivity. The use of other mouthwashes was not allowed. |

1. Reduction in PD (probing depth) between the T0/T1 (p00.02) and T0/T2 (p00.00), 2. reduction in the frequency of PI (plaque index) and BOP (bleeding on probing) observed between the baseline assessment and 180 days after RT |

Patients undergoing RT to the head and neck region with or without CT do not show aggravations of their clinical periodontal status for up to 6 months after cancer treatment if they also receive periodontal therapy and maintenance. |

||

| During the oncologic treatment | 1. Coronal polishing, 2. Topical application of 1 % neutral fluoride gel, 3. Reinforcement of oral hygiene | ||||||

| After the oncologic treatment | 1. Coronal polishing, 2. Topical application of 1 % neutral fluoride gel, 3. Reinforcement of oral hygiene | ||||||

|

Nunez-Aguilar, 2018 |

Biofilm |

Prior to, during, and after the oncologic treatment |

1. Teaching of oral hygiene, treatment of fluoride and chlorhexidine, scaling and polishing, scaling and root planning, selective carvings, to prevent bedsores in the oral mucosa teeth with sharp edges billed, prosthetic review, fillings, dental extractions. 2. Teachings of oral hygiene, use of chlorhexidine and fluoride 3. Survey before the oncological treatment, after starting the treatment, and with 60% of the treatment complete |

20 patients (47.78%) indicated that they had not had sore gums during CRT in the experimental group against 35 (87.5%) in the control group; In the experimental group, 7 patients (17.07%) had not had bleeding gums during CRT, in the control group 35 patients had had bleeding gums; in the experimental group, 4 patients (9.75%) had ulcers during CRT, in the control group, 35 patients (87.5%). 7 patients (17.07%) in the experimental group stated that they had a toothache after CRT. In the control group, 23 patients (57.5%); 8 patients (19.51%) in the experimental group affirmed they had sore gums after CRT, in the control group 23 patients (57.5%); in the experimental group, 7 patients (17.07%), had bleeding gums after CRT, in the control group of 36 patients (87.80%). |

Implementation of prevention protocols and the improvement in oral health among these patients is necessary. |

||

|

Niewald, 2013 |

Osteoradionecrosis |

Prior to the oncologic treatment |

1. Tooth extraction (followed up by an interval of at least 7– 10 days using soft diet, valid antibiosis and prosthodontic abstention) with primary tissue closure, 2. Endodontic treatment, 3. Removal of root remainders with primary tissue closure, 4. Conserving treatment |

11 patients (12%) were found to have developed infected osteoradionecrosis during follow-up. The one-year prevalence was 5%, the two- and three-year prevalence 15% - treated by conventionally fractionated RT applying doses of 50Gy (1 pat.), 60Gy (4 pats.), 64Gy (3 pats.), and 70Gy (3 pats.), respectively. 9/64 patients (14%) having been operated on had IORN compared to only 8% in the non-surgical patients. Oral mucositis grade II WHO was found in 47 patients (54%), grades III and IV in further 5 patients (6%, n = 87). Sialadenosis (dryness of mouth) was found in 72 patients (82%; grade: 22 patients (25%), grade 2: 38 patients (43%), grade 3: 12 patients (14%); n = 88). |

This meticulous dental care resulted in an incidence of IORN of 12%, all of them had undergone conventionally fractionated radiotherapy. It was very interesting to see that in the hyperfractionated group no IORN occurred at all. |

||

| During the oncologic treatment | Fluoridation was performed according to dental advice | We only conclude that a poor dental status, conventional fractionation and local tumor progression may enhance the risk of IORN. Meticulous dental care resulted in an incidence of IORN of 12%, all of them had undergone conventionally fractionated radiotherapy. In the hyperfractionated group no IORN occurred at all. Significant prognostic factors could not be found. | |||||

| After the oncologic treatment | 1. Patients were advised not to wear their dental prostheses up to 6–12 months after RT, 2. Tooth extraction with primary tissue closure, 3. Tooth extraction with primary tissue closure and conservative treatment, 4. Conservative treatment | ||||||

|

Regezi, 1976 |

Osteonecrosis, mucositis, dysgeusia, dysphagia |

Prior to the oncologic treatment |

1. Extraction of no salvageable teeth (teeth with gross dental caries, periapical pathology, advanced periodontal disease, and teeth supported by neoplasm). 2. Dental prophylaxis 3. Restorative dental procedures as needed 4. Initiation of oral hygiene regimen a. Tooth brush instruction with soft brushes, (patients were instructed to brush q.i.d. and to follow each brushing with oral lavage and fluoride rinse) b. Oral lavage instruction (1 liter warm water with 1 teaspoon each of NaCI and NaHC03) c. Sodium fluoride rinse instruction (1 teaspoon 3yo NaF held in mouth 1 minute, then expectorated). This rinse was discontinued during acute mucositis because of mucosal irritation. |

Oral hygiene status went from fair/poor at initial examination to good/fair after radiation therapy; Patients had normal healthy periodontium (25%), gingivitis (25%), and mild to moderate periodontitis (50%). Periodontal disease did not progress at a rate greater than would expect in a non-irradiated population. Teeth decay increased 20% following irradiation. All patients had mucositis, which became evident after 2 to 4 weeks of therapy (dysgeusia, dysphagia, dysorhexia, and pain). Overgrowth of Candida albicans was demonstrated in these patients. These symptoms subsided in 3 to 4 weeks after therapy. According to initiating factors, osteoradionecrosis was more frequent in posterior mandible due periapical/periodontal factor, and in mylohyoid ridge due trauma; according to the site, 50% occurred in the floor of mouth. After radiation therapy, it was necessary to extract teeth from 10 patients. |

It can be concluded from the data presented that the complications osteoradionecrosis, dental caries, and periodontal disease associated with radiation therapy for oral cancer can be reasonably well controlled using the regimen employed in this study. |

||

| During the oncologic treatment | 1. Weekly prophylaxis with fluoridated polishing paste 2. Prescriptions for pain relievers, dietary supplements, and antifungal or antibiotic agents when needed |

||||||

| After the oncologic treatment | 1. Oral and neck examination for detection of recurrent or new neoplastic diseases 2. Dental prophylaxis 3. Restoration dental procedures as needed 4. Reinforcement of the previously instituted oral hygiene regimen |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).