1. Introduction

Some important physical problems, ranging from celestial mechanics to magnetized plasmas, naturally exhibit rich conservative invariants. These problems are often connected to geometric structures, which have garnered increasing interest in recent studies [

1,

2,

3]. Examples of such structures include Hamiltonian, volume-preserving, Poisson, contact, and integral-preserving systems. Among these, variational structures play a central role in modeling systems in various applications. The inverse variational principle [

4] provides the foundational approach for studying systems within the Lagrangian framework [

4,

5,

6]. Through Legendre transformations, the Hamiltonian and Lagrangian formulations are shown to be equivalent. In the variational framework, variational integrators are constructed by discretizing the Lagrangian. Numerical methods are then derived via the discrete Euler–Lagrange equations. Further details can be found in [

7] and the references therein. These numerical methods consistently demonstrate superior efficiency and stability. Such methods have been successfully applied to simulate various physical problems, including soliton wave equations [

8,

9], charged particle dynamics in electromagnetic fields [

10,

11,

12,

13], and kinetic models in plasma physics [

14,

15], among others.

In the theory of backward error analysis (or modified equations theory), a numerical method is interpreted as the exact solution of a nearby “modified” system. According to this theory, structure-preserving numerical methods satisfy modified equations that retain the same structure as the original system. This explains the superior behavior of structure-preserving numerical methods in long-term simulations [

16,

17,

18]. In [

19], the concept of modified equations has been extended to variational equations. This theory can be extended to analyze adaptive time-step variational integrators [

20] and Hamiltonian partial differential equations (PDEs) [

21,

22], broadening its applicability to a wider range of systems.

This paper focuses on second order ordinary differential systems. We establish the necessary and sufficient conditions for variational formulations of a class of systems. This framework naturally encompasses classical and relativistic dynamics, as well as the motion of charged particles under Lorentz forces. In this variational framework, variational integrators are constructed by discretizing the Lagrangian. To enhance computational efficiency, we introduce new variational integrators by splitting the Lagrangian. Through Legendre transformations, we prove that these methods are equivalent to composition methods. We use the Kepler problem as an example, where geometric integrators have been shown to perform well in long-term numerical simulations [

23,

24,

25,

26]. The Kepler system, a super-integrable system that models gravitational motion, involves conserved quantities such as energy, angular momentum, and the Laplace–Runge–Lenz (LRL) vector [

27]. We investigate the superior numerical performance of variational integrators in simulating the Kepler problem. In addition to energy and momentum, the LRL vector, a hidden conserved quantity [

28], governs orbital geometry. By Noether’s Theorem [

29], we show the variational symmetries for energy, momentum, and the LRL vector. Through the development of modified equations and modified Lagrangians, we understand the solution of variational integrators as exact solutions of the perturbed Kepler system. Using modified equation theory, we demonstrate that the modified Kepler equation remains integrable, ensuring bounded errors in preserving energy and momentum. However, the modified equation loses super-integrability, leading to a quasi-periodic orbit instead of a periodic one. We explicitly derive the modified Lagrangians for the symplectic Euler, Störmer—Verlet methods, and the newly derived variational integrators. Perturbation theory reveals the super-convergence of these new variational integrators in preserving the LRL vector.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes the necessary and sufficient conditions for describing second order systems within a variational framework.

Section 3 constructs variational discretizations by splitting the Lagrangian. The resulting numerical discretization is shown to be equivalent to the composition method. Using classical and relativistic Kepler systems as examples, we illustrate the numerical methods and present variational symmetries for energy, momentum, and the LRL vector.

Section 4 develops the theory of modified equations and modified Lagrangians. The recursive expressions for the Nyström methods is provided. For the Kepler problem, we also analyze the errors of the newly proposed variational integrators in conserving quantities. In

Section 5, we apply the newly derived variational integrators to solve the Kepler problem. The numerical results demonstrate the superior performance of these methods. We further analyze the numerical performance using the modified Lagrangian theory. Additionally, we apply the variational integrators to solve the relativistic Kepler system. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Variational Principle in Lagrangian Formalism

We begin this section by introducing the inverse variational methods presented in [

4,

5,

6]. Let

be a real Hilbert space with inner product

. Let

be an operator. The operator

N is called as

symmetric if

, where

is the adjonit operator defined by

for

. The

Fréchet derivative of

N at

, denoted

, is the linear operator satisfying

According to the Vainberg’s Theorem in [

4], we have

Theorem 1.

Let N be a operator defined on . If the Fréchet derivative of N is symmetric, i.e. , then there exists a functional S on , constructed as

such that , where the variational derivative is defined by , .

In this paper, we mainly focus on the variational description for the system of second order differential equations. Consider the systems governed by

where

is an

symmetric matrix.

Theorem 2.

System (2.1)

admits a variational formulation if and only if

hold for all .

Proof. Define

. The variational calculus gives

The adjoint of

is defined as

From the integration by parts, we have

Therefore,

According to Theorem 1, The system is variational if and only if (2.3) and (2.4) are identical. Comparing (2.3) and (2.4) leads to

The above equality holds for arbitrary

, thus the coefficients in terms

,

and

vanish. Since

M is symmetric, this implies exactly that

This completes the proof of the theorem. □

Assuming and f is linear in , we can rewrite the above theorem as follows.

Theorem 3.

For and , system (2.1)

is variational if and only if

where .

Proof. Since

M depends only on

, (2.2b) simplifies to (2.5a). The condition (2.2c) reduces to

In the above equality, the term on the right-hand side does not depend on

, so the coefficients of

vanish. □

Remark 1.

Define a differential two-form by . If (2.5a) and (2.5b) hold, then . By Poincaré’s lemma, there exists a one-form such that . This implies . Condition (2.5c) means that φ can be generated from a potential ϕ by .

In more classical applications, M is typically a constant matrix. In this case, for the system to be variational, we only need the conditions for the vector field f.

Theorem 4.

For constant symmetric M, system (2.1)

is variational iff

holds for .

Many important physical problem including some relativistic models can have the forms of Theorem 3. Consider the relativistic dynamics (such as a charged particle in a Coulomb potential)

where

is the Lorentz factor,

c is the speed of light. In the non-relativistic limit (

), this reduces to Newtonian mechanics

. It is evident that the velocity-dependent terms satisfy the symmetry conditions (2.2a) and (2.5c). This system admits the variational formulation with Lagrangian

.

It is well known that from Lagrangian framework it is more convenient to investigate the connections between conservation laws and symmetry properties of dynamical systems based on Noether theorem. The foundational framework requires introducing generalized vector fields and their action on variational principles [

6].

A

generalized vector field is given by

where

contain x and all the derivatives of

x and

denote its characteristic. The

infinite prolongation of

is defined as

where

denotes

j-th order time derivatives.

Definition 1.

A generalized vector field is called a variational symmetry

for the functional if there exists a function such that

Given a differential system

, if there exists

satisfying

then

Q is called the characteristic of the nontrivial conservation law

.

Theorem 5 (Noether’s theorem). A generalized vector field is a variational symmetry if and only if its characteristic Q is also the characteristic of a conservation law along the solution of Euler–Lagrange equations.

When the system is perturbed, the following proposition holds.

Proposition 1.

Given a Lagrangian L, let and P denote its variational symmetry and the corresponding conserved quantity, respectively. Under the perturbed Lagrangian , P along solutions of satisfies

where is the the Euler operator.

Proof. By Theorem 5, it gives

. For the solution of the perturbed system

, we have

Substitution yields

. □

3. Discrete Lagrangian Mechanics

Variational integrators preserve geometric structures by discretizing Hamilton’s principle. For foundational theory, see [

7]. Consider a uniform time grid

with coordinates

. The discrete Hamilton’s principle is to find the trajectories

extremizing the discrete action functional

Here,

is the discretization of

L, given by

. Its adjoint, denoted by

, is defined as

. The discrete solution

satisfies the discrete Euler—Lagrange equations

Consider the system

with Lagrangian

. We discretize the Lagrangian to obtain the variational integrators. By splitting the potential

as

, we present the following discrete Lagrangian. A first order variational integrator uses the discrete Lagrangian

where

,

is the

N-dimensional vector with the

j-th element being 1.

Theorem 6.

The discrete Lagrangian is of order 1. Moreover, the discrete Euler–Lagrange equations for (3.3)

generate

It coincides with the composition method

where represents the subsystem, and is the corresponding numerical discretization, given by

Proof. Using the Taylor expansion at an arbitrary

, we have

Substituting these into (3.3), it is easy to known that the discrete Lagrangian has first order accuracy.

Introduce the discrete Legendre transformation

the discrete Euler–Lagrange equation gives

From (3.4) and (3.5), we can derive

This is exactly the composition method

. □

The discrete Lagrangian of higher order variational integrators can be constructed by combining

and its adjoint

By the discrete Euler–Lagrange equation, these provide the higher order variational integrators.

Theorem 7.

The variational integrators from (3.7) and (3.8) are equivalent to and , respectively.

Proof. The corresponding discrete Euler–Lagrange equation for (3.7) gives

Introduce the discrete Legendre transformation,

From (3.9b), we know

Combine (3.10) and (3.11), we can prove that

. □

As follows, we take the Kepler problem as example to illustrate the new derived variational methods of first and second order.

Kepler problem. The Kepler problem describes the motion of two bodies attracting each other. We focus on the 2-dimensional Kepler problem in the following text. If one body is placed at the origin, and

x represents the position of the other body, their dynamics are governed by the following system

where

. It is obvious that the Kepler problem (3.12) satisfies Theorem 4, and its Lagrangian is given by

The Kepler problem (3.12) has three conserved quantities: energy, angular momentum, and the Laplace–Runge–Lenz (LRL) vector. When the initial energy , the solution orbit of the Kepler problem is elliptic, such as the motion of one astronomical body moving around another. In this case, the LRL vector determines the orientation and shape of the elliptical orbit. The magnitude equals the orbital eccentricity e, and the vector points along the major axis of the orbit.

Proposition 2.

For the 2D Kepler system (3.12), the following quantities are conserved

Energy ,

Angular Momentum ,

LRL Vector .

Introducing the polar coordinates

, the Kepler’s Three Laws [

28] are exhibited.

Proposition 3 (Kepler’s Three Laws). For bound orbits (negative energy) in the 2D Kepler problem, we have

The inverse of the radial distance is given by ;

The period of the orbit is ;

The areal velocity is conserved, i.e., .

where a and b represent the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the orbit, is the eccentricity.

Based on Noether’s theorem, for the two-dimensional Kepler problem (3.12), we derive the variational symmetries corresponding to the three conservative quantities expressed in Proposition 2.

Proposition 4. The variational symmetries associated with the energy, angular momentum, and the LRL vector are as follows:

,

,

, .

Proof. Taking

gives the following equality for energy conservation

Suppose the generalized vector field

. By Theorem 5,

is exactly the variational symmetry of the energy. The other variational symmetries follow analogously from their conservation laws. □

Splitting

as

, we construct the first order and second order discrete Lagrangians. The first order Lagrangian (3.3) yields the variational integrator through the discrete Euler–Lagrange equations

The second order Lagrangians (3.8) generates the numerical methods

Relativistic Kepler Problems. Considering the relativistic Kepler systems in (2.7) with the potential

. By the proper time

and relativistic momentum

, we reformulate system (2.7) as

where

. Let

and

, where ’·’ denotes differentiation with respect to

. By Theorem 4, we learn that the system (3.16) admits a variational formulation with Lagrangian

where

and

. The system (3.16) has two Hamiltonian formulations. Defining

, the system (3.16) admits the standard Hamiltonian form

where

and the Hamiltonian

is non-separable. Introducing

transforms the system into a

K-symplectic [

1,

3] formulation:

where

with

. In the formulation (3.18), the Hamiltonian becomes separable

By decomposing this Hamiltonian into

parts, we derive the

K-symplectic subsystems.

The subsystem

has the exact solution, which is

For

,

, the solution of

i-th subsystem is

We obtain the

K-symplectic method by composing the exact solution of the subsystem.

Theorem 8.

The discrete Lagrangian for (3.16)

generates the variational integrator

This is equivalent to the K-symplectic method (3.19)

.

Proof. Introducing the following transformations

with

, yields

Reformulating (3.21) leads to

which are exactly the

K-symplectic methods (3.19). □

4. Modified Equations for Variational Integrator

We begin this section by introducing the concept of modified equations presented in [

19] for second order systems

Definition 2.

For system (4.1)

, denote the method by . Its modified equation is a formal second order differential equation

satisfying for all n.

Expanding the difference equation

around

gives

Introducing

, it follows from (4.2) that

Taking the derivative of the above equality with respect to

t gives

Substituting the higher derivatives

into the terms

in (4.3), we obtain the following theorem by comparing the coefficients of

h on both sides of (4.3).

Theorem 9.

The coefficients in the modified equations (4.2) are uniquely determined recursively by f, , …, , , …, , and their derivatives.

Theorem 9 provides a recursive relation for calculating the coefficients of modified equations. We illustrate this by applying the Nyström methods [

2] to (4.1), which results in

Theorem 10.

For the Nyström methods (4.5)

, the coefficients of modified equation can be achieved by

where is an elementary differential, as described in [2].

Proof. Using (4.5a) and (4.5b) to eliminate the intermediate variable

v yields the scheme

From (4.5a) and (4.5c), we derive

Expanding the left-hand side of (4.6) about

gives

Similarly,

and

on the right term can be expanded about

up to

, as

Substituting (4.8) and the higher derivatives (4.4) into the right-hand side of (4.6) and comparing the coefficients of the term

yields recursive formulas.

thus completing the proof. □

Remark 2. Generally, the system of modified equations represents a formal divergent series. However, for linear second order systems, we are able to obtain a convergent modified series. Further details can be found in Appendix A.

It is well-known that the system (3.2) has a variational description. However, not all numerical discretizations of this system are variational. A method is variational if and only if its modified equation (4.2) maintains variational structure. By Theorem 4, this requires the coefficients

to satisfy

This implies the existence of formal Lagrangian which is called as the

modified Lagrangian denoted by

.

Definition 3.

The modified Lagrangian is a formal series

whose Euler–Lagrange equations

have the solution matching the variational integrator .

An alternative definition of modified Lagrangian can be found in [

19], that is

where

. Differentiating (4.10) w.r.t to

yields

where boundary terms vanish.

Expand the discrete Lagrangian

at

, it reads

where

x denote

,

contains

x and its derivatives. By Lemma 1 in [

19], the discrete action functional over the interval

can be expressed as

where

are Bernoulli numbers with

,

and

. From (4.10), it follows that

Solving

implicitly from the modified Euler–Lagrange equation (4.9) and substituting it into (4.12), we can eliminate

and its higher order derivatives in the right-hand side of (4.12). According to Proposition 6 in [

19], the term

only depends on

x and its

j order derivatives

. Comparing the coefficients of the term

on both sides of (4.12), we obtain

Recursively, we can derive the modified Lagrangian as a formal series corresponding to the time step

h.

For the system (3.2), the Störmer–Verlet method originates from the discrete Lagrangian

As presented in [

19], its second order modified Lagrangian

yields the following modified Euler–Lagrange equation

The symplectic Euler method corresponds to the first order discrete Lagrangian

The discrete Lagrangians (4.13) and (4.16) are weak equivalence [

7] as their corresponding variational integrators are the same as

Theorem 11.

For the discrete Lagrangian (4.16)

, its third order modified Lagrangian is

with corresponding Euler–Lagrange equation

Proof. Expanding (4.16) around

, we obtain

Applying the modified Lagrangian construction (4.12)

It is evident that

which implies that the terms in

vanish. Substituting

into (4.18) yields (4.17). The Euler–Lagrange equation follows from

□

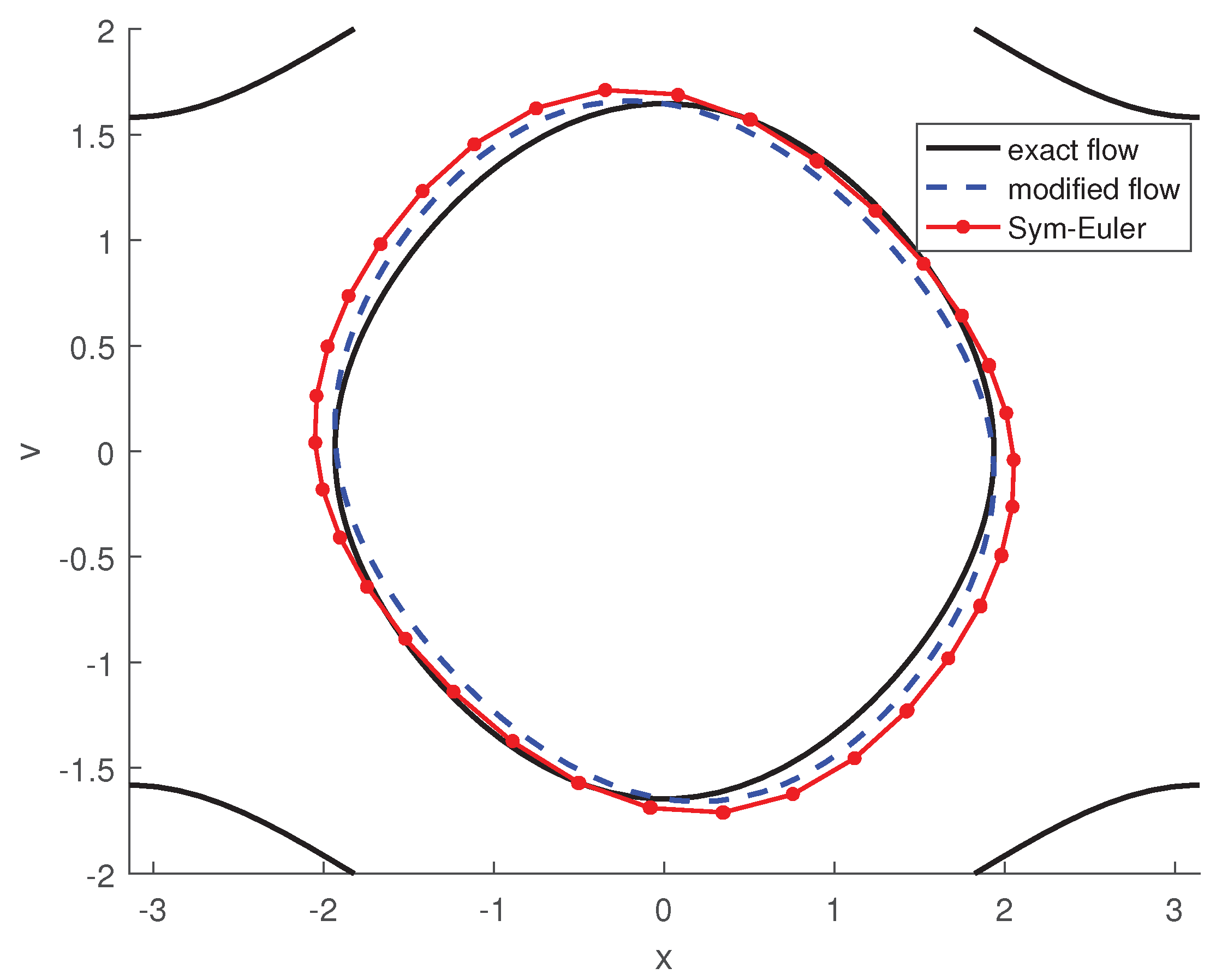

We illustrate the solutions of truncated modified equations using the pendulum problem. For this, let

in (4.1). The modified Lagrangian gives the corresponding modified Hamiltonian via the Legendre transformation. Denote the

k-th order truncated Lagrangian by

and the corresponding Hamiltonian by

. For

, the modified Hamiltonian corresponding to

is given by

which matches the result in [

2]. In

Figure 1, we show the numerical solution using the symplectic Euler method from (4.16), along with the exact flow of the pendulum problem, represented by the contour plot of the Hamiltonian. The contour plot of (4.20) shows the exact flow of the modified pendulum problem at first order. The initial conditions are

. In

Figure 1, the solid line represents the exact solution of the pendulum, while the dotted lines correspond to the symplectic Euler method and the exact solution of the modified pendulum. The results show that the modified pendulum problem provides better agreement between the numerical solution and the exact solution. As we include more terms in the truncation, we expect further improvement. However, since the modified equations are not convergent, there is an optimal truncation level based on asymptotic expansion theory.

For the newly presented variational integrators from (3.3) and (3.8), the modified Lagrangians are established in the following theorem.

Theorem 12.

For the first order discrete Lagrangian (3.3)

, its modified Lagrangian truncated to order 2 can be formulated as

The corresponding Euler–Lagrange equation takes the following form:

For the second order discrete Lagrangian (3.8)

, the second truncation of the modified Lagrangian is given by

The corresponding Euler–Lagrange equation can be expressed as

where

Proof. Without loss of generality, we compute the modified Lagrangian of second truncation for the discrete Lagrangian (3.8). Expand (3.8) about

, we derive

Substitute

into (4.12), we obtain

We apply

to eliminate term

in (4.25), this leads to (4.23). With the modified Lagrangian (4.23), the direct calculation provides the modified equation (4.24). □

As discussed earlier, the variational integrator can be interpreted as the exact solution to the modified equations. Consequently, the conservative properties of numerical methods are linked to their modified Lagrangian. Through backward error analysis [

2], it is expected that variational integrators can preserve energy and angular momentum over long-time integration. For the Kepler problem, known as super-integrable, we present the following theorem to characterize the preservation of the LRL vector.

Theorem 13.

For the perturbed Kepler problem, let its Lagrangian be . Assume the initial orbits are aligned with the -axis to , then the variation of the LRL vector over one period satisfies

and the change in the angle ω relative to the x-axis is given by

Here, are the LRL characteristics shown in Proposition 4, T is the orbital period, and denotes the T-period average.

Proof. Under the assumption of the proposition, we have

and

. According to Proposition 1, it follows that

where

and

x are the solutions of the perturbed and unperturbed Euler—Lagrange systems, respectively. Differentiating

and

yields

Therefore, we obtain

Integrating both sides of the above equalities w.r.t

t over one period proves the theorem. □

By the theory of modified Lagrangian, the variational integrators yield the perturbed Lagrangian. In the following, we present the error estimates of the LRL vector for the Störmer–Verlet methods, the symplectic Euler methods, and the variational integrators in (3.14) and (3.15). Moreover, we prove that the eccentricity for the Störmer–Verlet method exhibits super-convergence, extending the precession analysis of angle from [

30].

Theorem 14.

Under the condition of Theorem 13, for the Störmer-Verlet from (4.13)

, the eccentricity error satisfies

Proof. In Theorem 13, setting

and

leads to

As verified in [

30], we know that

Due to the periodicity of the Kepler solution, the term

vanishes. In polar coordinates, where

and

, we compute the time average of

over one period, which vanish for

. Specifically,

Consequently, it follows from (4.29) that

which completes the proof. □

Theorem 15.

Under the condition of Theorem 13, for the symplectic Euler method from (4.16), the errors in eccentricity and the angle of the LRL vector over one period are of order 2.

Proof. For the discrete Lagrangian (4.16), its modified Lagrangian is given in Theorem 11. Setting

and

, the modified Lagrangian can be written as

From Theorem 13, we have

Noting that

, it follows that

□

For the newly constructed discrete Lagrangians (3.3), we set and with . The following theorem establishes that the corresponding variational integrators (3.14) derived from (3.3) exhibit super-convergence both in preserving the eccentricity and the angle of the LRL vector.

Theorem 16.

Under the condition of Theorem 13, for the first order discrete Lagrangian (3.3) with and , , the errors of the variational integrator (3.14) in eccentricity and the angle of the LRL vector are both of order 2.

Proof. For the discrete Lagrangian (3.3), the modified Lagrangian is given in Theorem 12 as

Define

Since

, it follows that

By Theorem 13, the error in eccentricity is given by

Similarly, the error in the angle of the LRL vector is

In polar coordinates, where

and

with

corresponding to the positive

axis, we apply Kepler’s laws. The integral average of

over one period is computed as

Similarly, we find

Combining the above results, we conclude

□

5. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we present numerical experiments to evaluate the results obtained using the newly constructed variational integrators introduced in

section 2. We compute the classical and relativistic Kepler systems.

Kepler problem is an important dynamical system that is super-integrable with three conserved quantities. As shown in

section 2, the system is variational, and its variational integrators can be constructed by splitting the potential

. In this section, we implement the first order variational integrator (3.14) (VI-1) and the second order variational integrator (3.15) (VI-2) by taking

.

Using the initial conditions

with

, and a time step of

, we perform numerical computations over

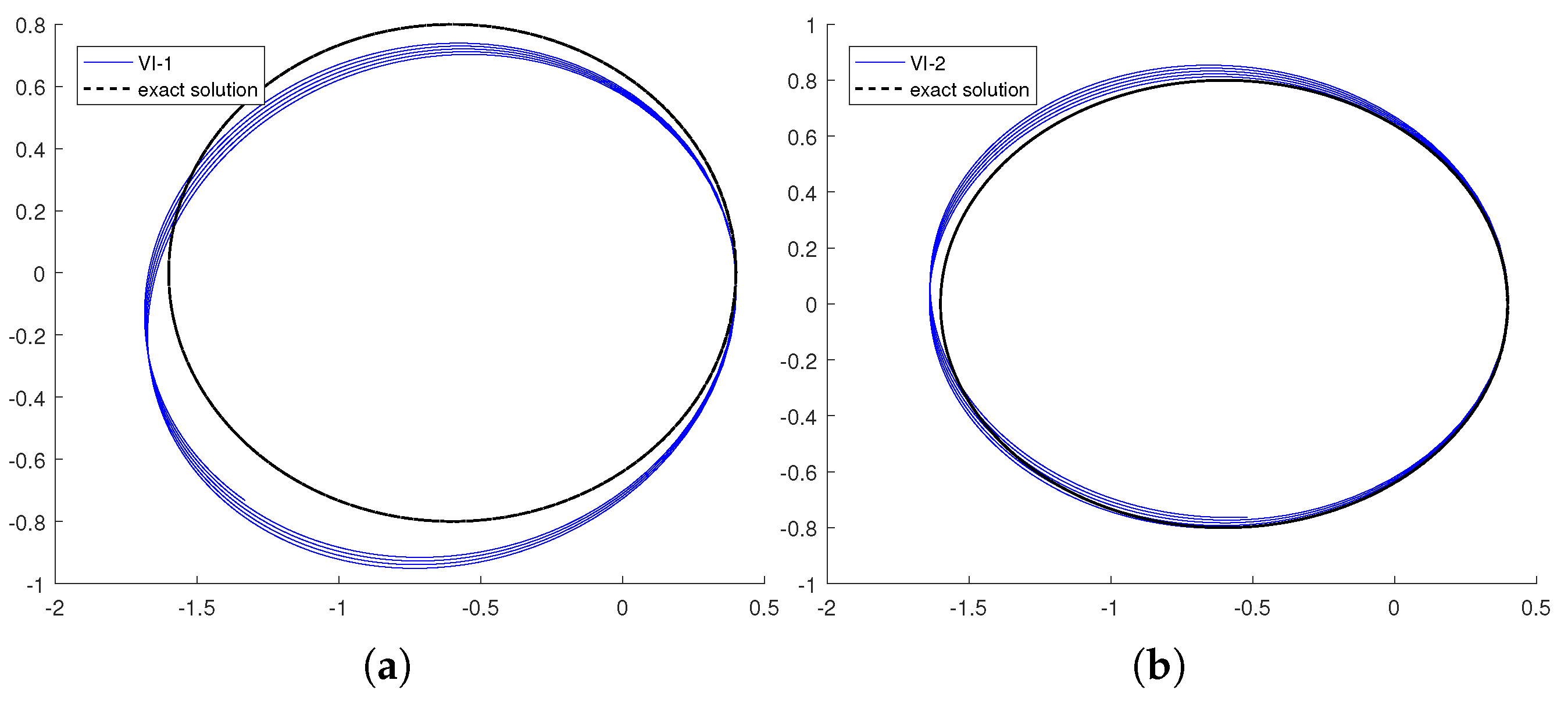

. For comparison, we also show results from the symplectic Euler method and Störmer—Verlet method. The numerical orbits computed by the four variational integrators are shown in

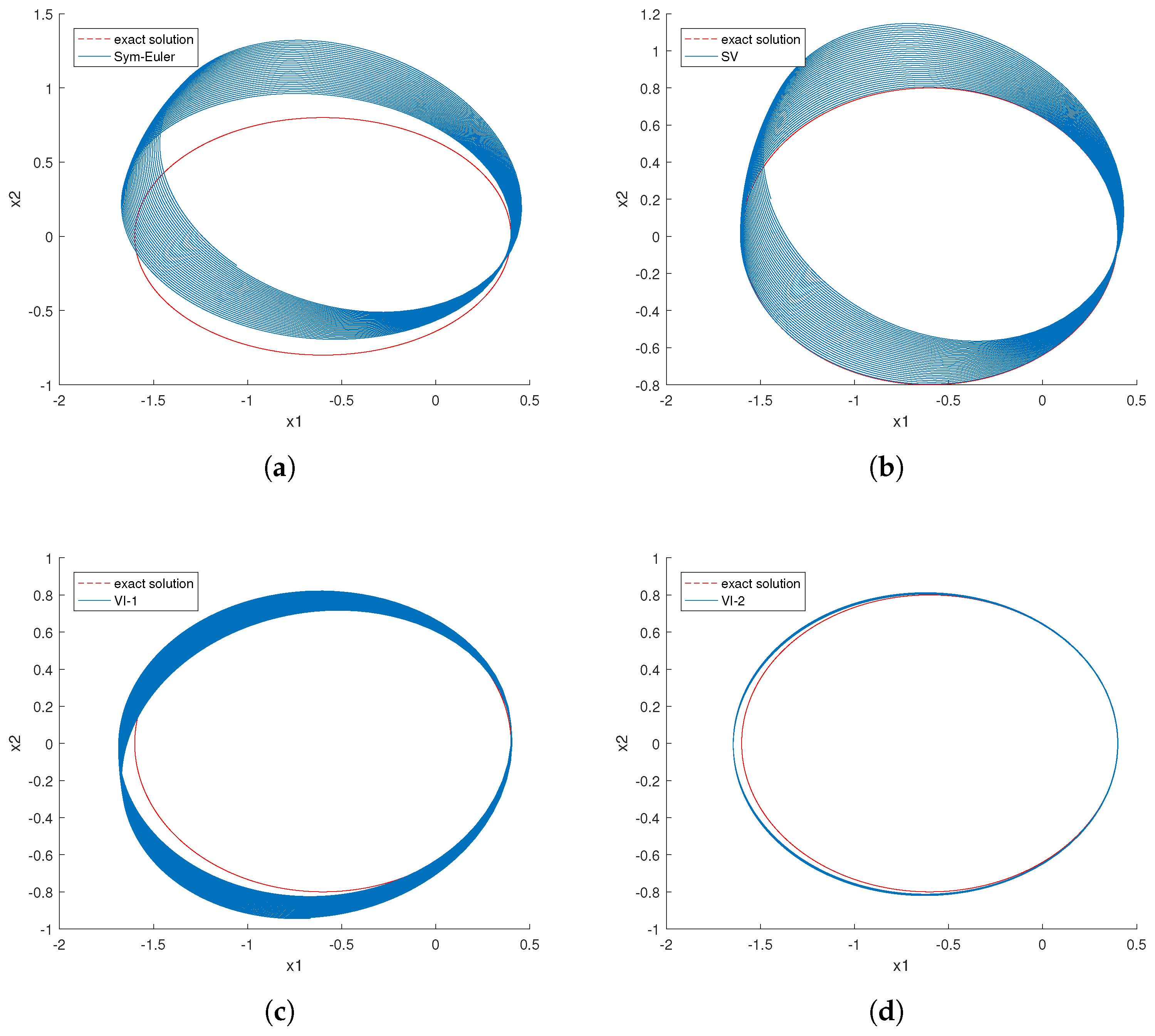

Figure 2. The orbit in the top-left corner is generated using the symplectic Euler method, while the top-right orbit is computed using the Störmer–Verlet method. The bottom-left and bottom-right orbits are simulated by the first and second order variational integrators (VI-1) and (VI-2), respectively. The background dotted line represents the exact orbit. It is clear that the numerical orbits on the top show a pronounced clockwise drift, while the two variational integrators provide better simulation results. Among the four methods, the orbit computed by the second order variational integrator (VI-2) exhibits the least numerical error.

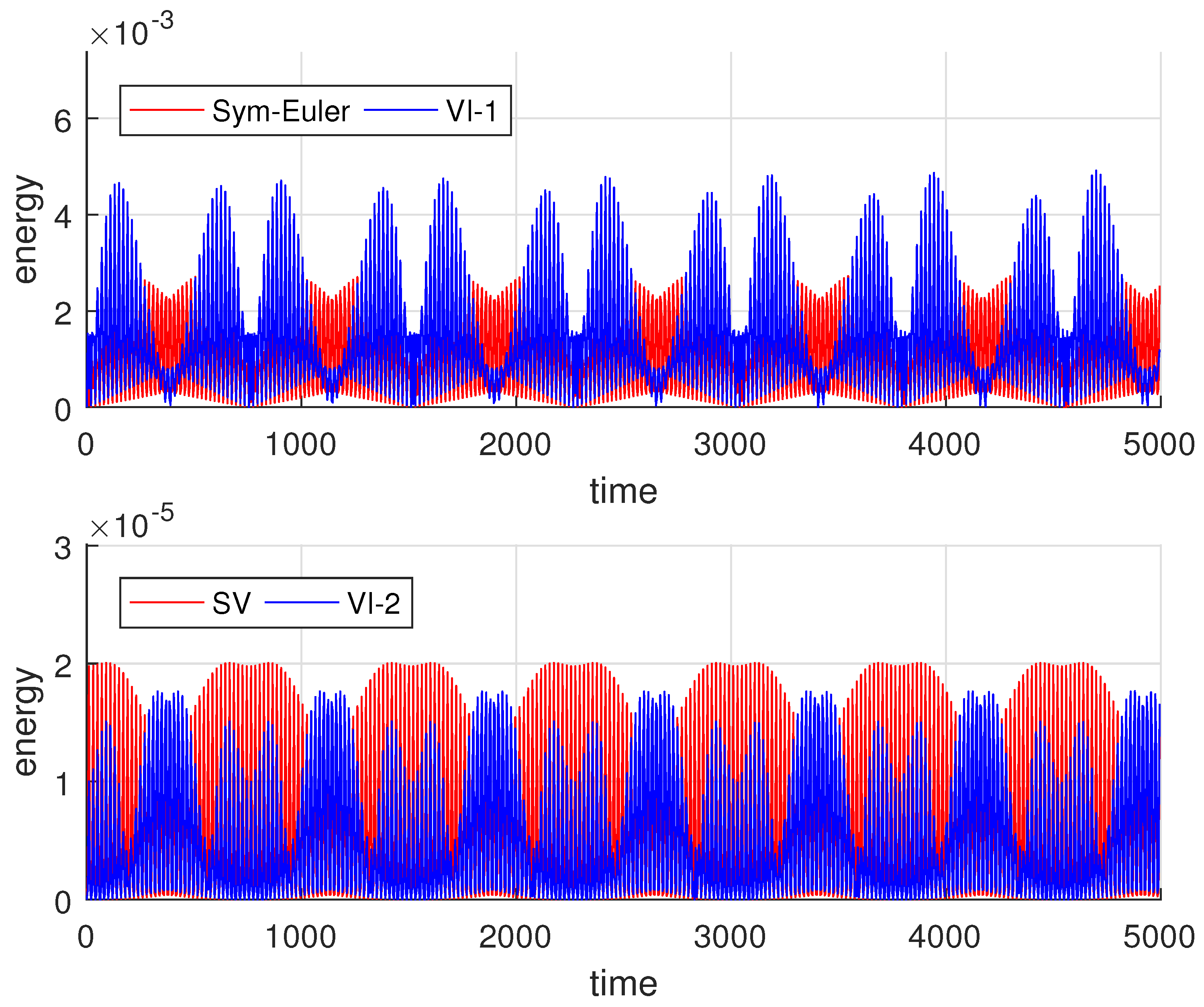

We now show the preservation of conservative quantities by the variational integrators. The initial conditions are

, and the step size is

. From

Figure 3, we observe that the numerical errors in energy can be bounded by all four variational integrators over the long term. For the Kepler system, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz (LRL) vector, which defines the orientation and shape of the orbit, is also a conserved quantity. We present the numerical results for both the norm of the vector (eccentricity) and the angle (which governs the orientation and shape of the elliptical orbit). As discussed in

Section 4, the solution of the variational integrator corresponds to the exact solution of the modified second order differential equation. While the original Kepler system is super-integrable, the modified system is not. However, through backward error analysis [

16,

18], we show that the modified system remains integrable under symplectic methods. Thus, all four numerical methods bound the energy and momentum. The energy errors for the four variational integrators are plotted in

Figure 3.

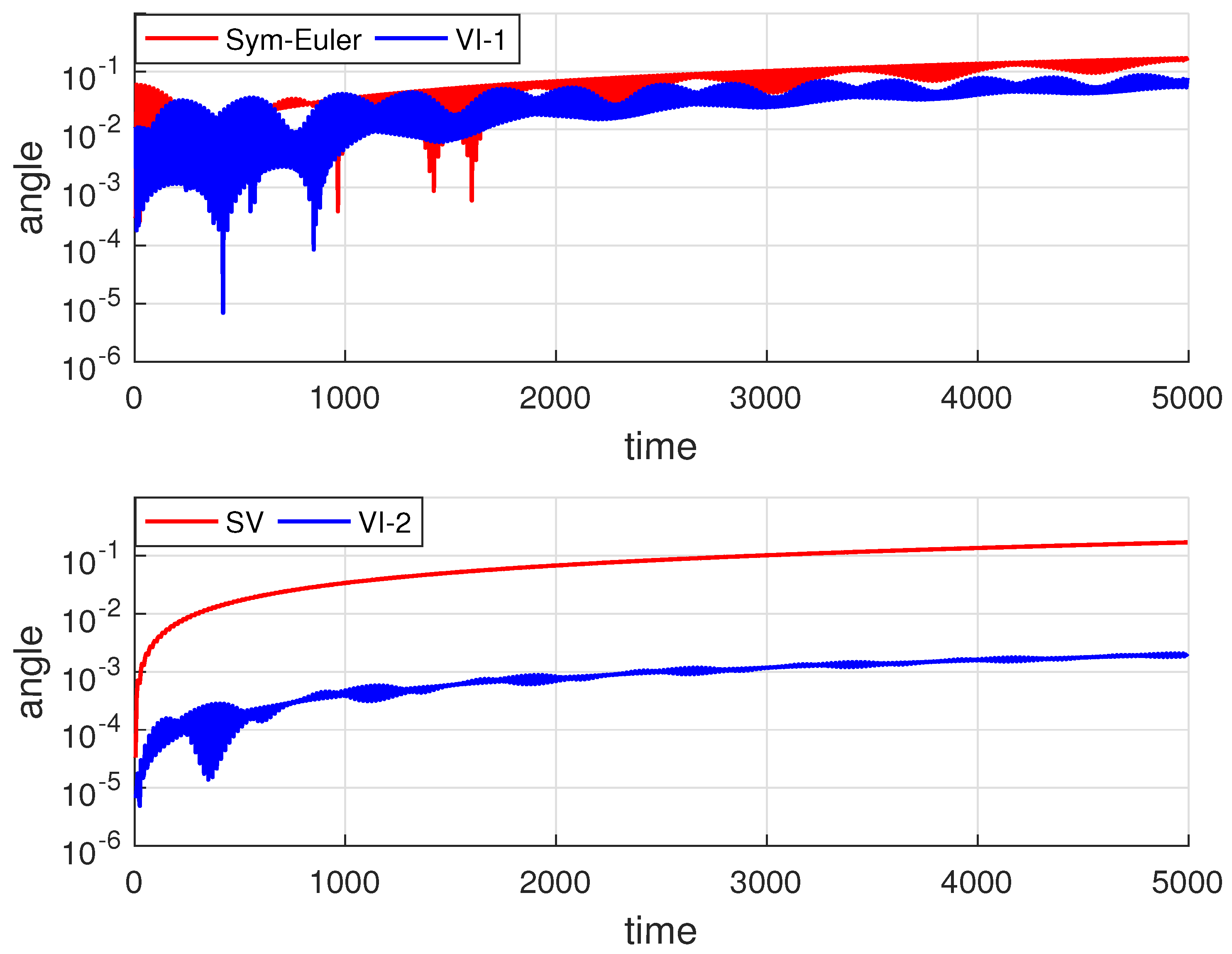

In

Figure 4 and

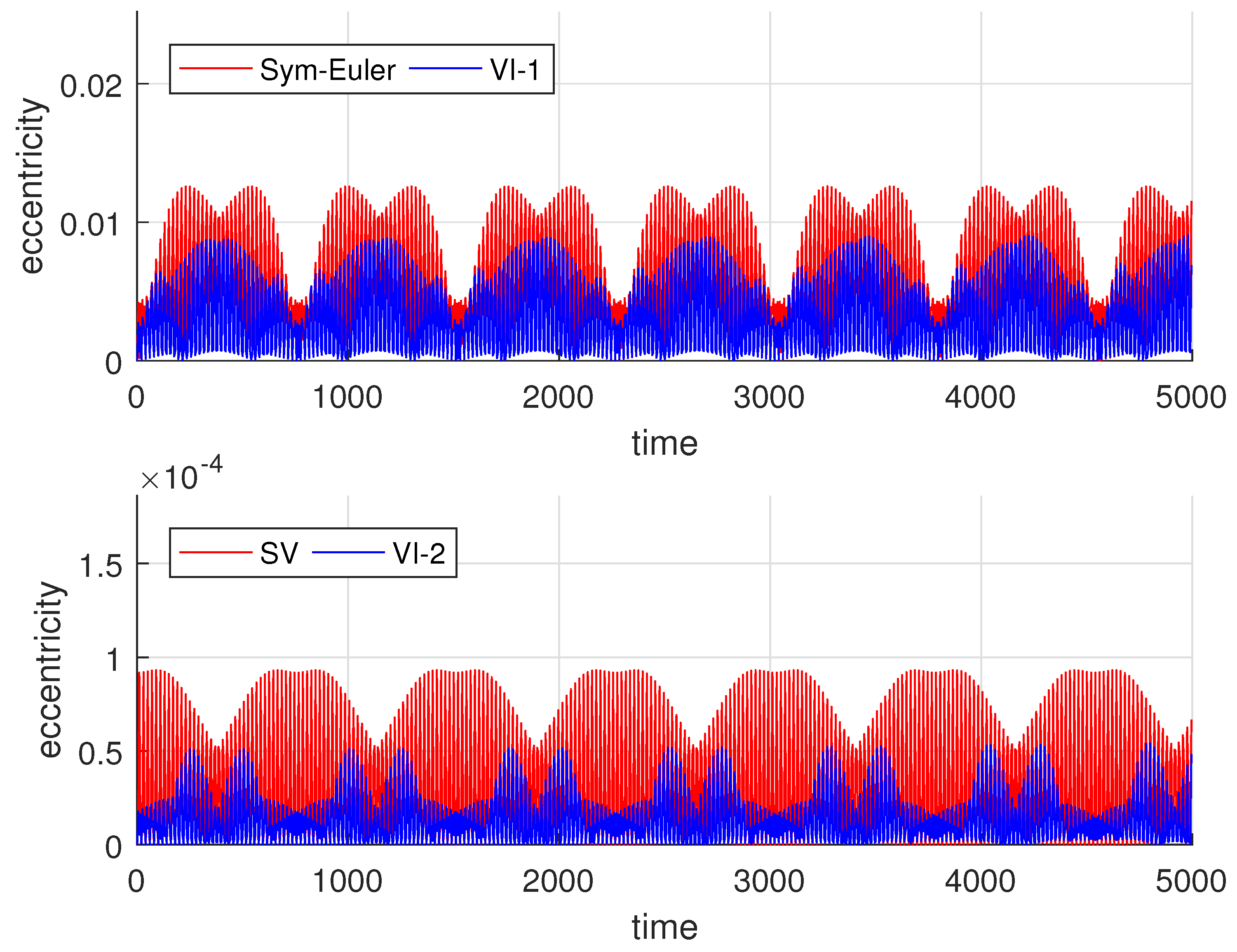

Figure 5, we compute the LRL vector using all four variational integrators. These figures show that the eccentricity error is bounded by all four methods, with the new variational integrators producing significantly smaller errors in both eccentricity and rotation angle.

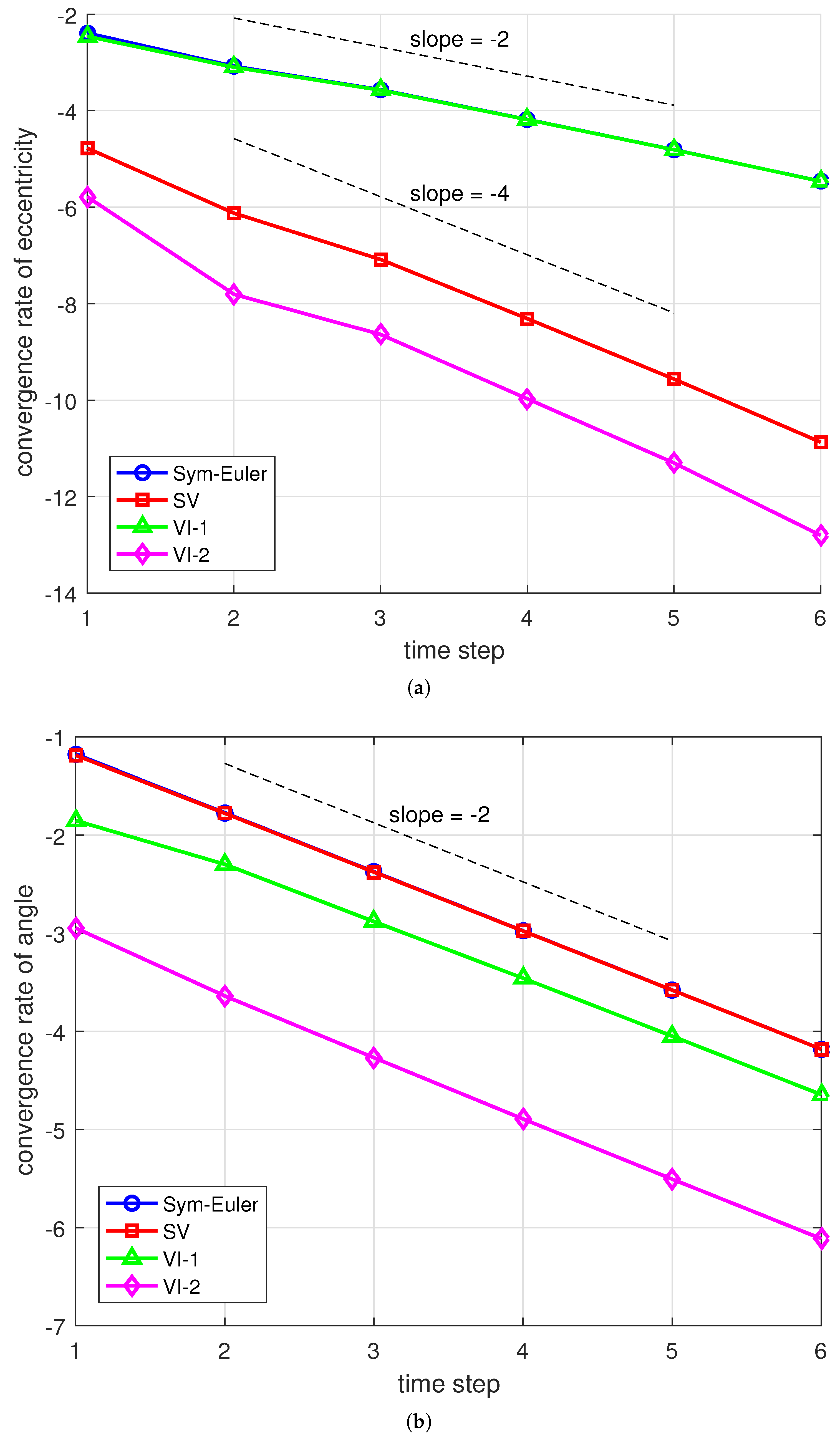

We also present the convergence rates for the eccentricity and angle of the LRL vector, illustrated in

Figure 6. To estimate the convergence order, we begin with

and compute results for time steps

, for

. The results are shown in a log-log plot. For the eccentricity error in

Figure 6(a), both the symplectic Euler method and the first order variational integrator exhibit second order convergence. Their error curves are nearly identical. The Störmer—Verlet method shows super-convergence of order 4, while the second order variational integrator also demonstrates super-convergence and produces smaller errors compared to the Störmer—Verlet method. In

Figure 6(b), we show the convergence rate for the angle error. All four methods exhibit a second order convergence rate, consistent with the theoretical estimates in

Section 4. The error curves for the symplectic Euler and Störmer—Verlet methods are nearly identical, but both the first and second order variational integrators show smaller errors in preserving the angle of the LRL vector. Among all four methods, the second order variational integrator achieves the smallest errors, demonstrating superior performance.

Relativistic Kepler System describes the motion of particles or bodies whose velocities are close to the speed of light. This system can be formulated by introducing proper time, with the Lagrangian given by

. The initial conditions are

, with a time step of

, and the computation spans

. In

Figure 7, we show the numerical orbits computed by the variational integrators (3.20) and (3.8). The numerical orbits computed by the two variational integrators show better performance qualitatively, confirming the structure-preserving nature of the newly proposed methods in relativistic spacetime.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we consider a class of second order systems in the form of (2.1), which can describe many important physical problems, including classical mechanics and relativistic plasma dynamics. For this class of systems, we derived the necessary and sufficient conditions for their variational formulation using the basic theory of inverse variational problems. We introduced a class of variational integrators by splitting the Lagrangian and proved that these numerical methods are equivalent to explicit symplectic compositions, ensuring efficient numerical computation. Remarkably, when the newly derived variational integrators are applied to the Kepler problem, we demonstrate better performance compared to the symplectic Euler and Störmer–Verlet methods. To analyze the numerical errors of the variational integrators in preserving conservative quantities, we developed the theory of modified Lagrangians and modified equations. The error estimates in preserving the LRL vector for the Kepler problem verify the numerical behavior. We also simulated the relativistic Kepler problem.

This framework can be extended to PDEs. Consider a nonlinear wave equation with rotational symmetry, assuming the equation has traveling wave solutions of the form

, where

and

. This reduces the wave equation to the following system of second order ODEs:

It can be easily verified that this system satisfies conditions (2.6a)-(2.6b). According to the theorem presented in this paper, this system admits a variational formulation when

. This extends the applicability of our approach to various mechanical and continuum problems and opens the door to developing the theory of modified equations for PDEs.