1. Introduction

Post-acidification is an undesirable phenomenon in fermented milk products, characterized by acidification outside the optimal pH range due to the activity of microflora [

1]. This process triggers an increase in the hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between protein molecules, hence, leading to: (i) the enlargement and aggregation of casein particles and (ii) partial restructuring of the protein network within the product [

2]. Consequently, post-acidification significantly reduces the shelf life of fermented dairy products.

The literature outlines several fundamental methods to prevent post-acidification, including adjusting the temperature during fermentation [

3,

4], modifying the acidity of the environment during fermentation [

5], incorporating pre- and probiotics [

6,

7], and altering the composition of the packaging materials [

8,

9]. Due to the limitations of the individual methods, they are often applied in combination. Currently, the most promising approach involves the use of various additives that do not compromise the taste or structure of the final product. However, as this area of research is relatively new [

1], the range of the thoroughly studied additives remains limited [

10,

11,

12]. Among these, additives, based on natural polymers, hold promise.

Chitosan, a natural amino polysaccharide, and its derivative systems are widely utilized in the food and biotechnological industries to mitigate post-acidification and extend the shelf life of fermented milk products [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Chitosan’s ability to form intermolecular complexes with milk proteins [

17,

18] plays a crucial role in the stabilization of the spatial protein network within milk [

19]. This stabilization addresses a key issue in the milk protein network, i.e., the structural disruption caused by ongoing post-acidification.

During the post-acidification, there is an increased growth of certain undesirable microorganisms, which are antagonized by lactic acid bacteria. The addition of pure chitosan enhances the activity of lactic acid bacteria, thereby slowing down the post-acidification process [

20,

21]. This increased activity of lactic acid bacteria suppresses the growth of spoilage-causing microflora. As highlighted in the literature [

22], the incorporation of chitosan nanoparticles into milk and fermented dairy products (e.g., cheese and yogurt), significantly inhibits the growth of pathogenic microflora, such as

E. coli and yeast, thereby mitigating the post-acidification scenario [

23]. Furthermore, chitosan can be employed as a matrix for immobilized enzymes [

24], capable of interacting with bifidobacteria, again leading to a decrease in acidity.

Metal ions can also impact the post-acidification processes, as demonstrated in recent studies [

25,

26]. Salts of Cu(II), Fe(II), and Zn(II) have been shown to influence these processes effectively. Additionally, the incorporation of trace amounts of Ag(I) into milk packaging has been proven to slow down post-acidification and suppress the growth of undesirable microflora [

27,

28]. While compounds based on Cu(II) and Ag(I) have been extensively studied, the potential of Mn(II) and its derivatives remains underexplored. Among the suitable metals, Mn(II) holds significant research interest due to its role in biological processes. For instance, Mn(II) is a key component of enzyme catalysts involved in oxidation-reduction reactions and plays a critical role in fermentation processes [

29,

30,

31]. The presence of Mn(II) ions in milk influences both the properties of the raw product and the activity of lactic acid bacteria [

32,

33]. Mn(II) inhibits the growth of yeast and mold, which are common contributors to the spoilage of fermented milk products. This antimicrobial effect is attributed to the absorption of small amounts of Mn(II) ions by the lactic acid bacteria, thereby enhancing their resistance to harmful molds and yeasts. Additionally, Mn(II) significantly increase the rate of milk fermentation. The addition of manganese salts is reported to reduce fermentation time by up to fivefold, thereby accelerating the production of fermented dairy products [

34].

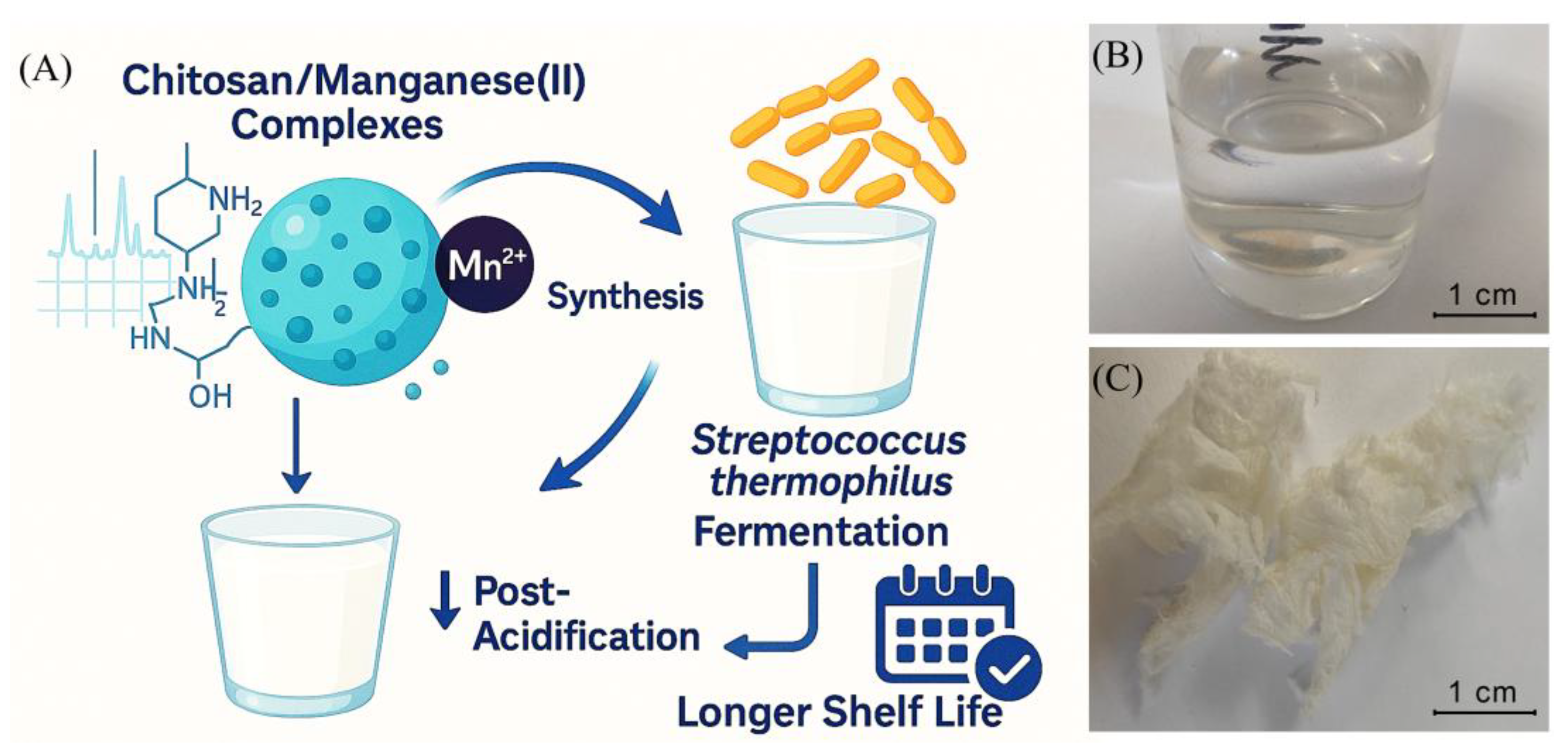

However, the literature currently lacks an evaluation of the effects of manganese salts and chitosan complexes with Mn(II) ions on both the fermentation and post-acidification processes. Herein, it is hypothesized that metal complexes based on chitosan and Mn(II) ions could effectively stimulate the milk fermentation process, thereby extending the shelf life of fermented dairy products. Additionally, it is proposed that these complexes have the potential to significantly slow down post-acidification, offering a promising approach to improving the quality and stability of fermented milk products (

Figure 1, A).

To test this hypothesis, a series of metal-containing systems based on chitosan and Mn(II) in various molar ratios (1:2, 1:1, and 2:1) was prepared. Their structure and properties were characterized using several physicochemical methods, including dynamic and electrophoretic light scattering, IR spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and thermal analysis. Additionally, the enzymatic activity of the synthesized complexes and their impact on the production of colony-forming units (CFUs) by Streptococcus thermophilus in milk was evaluated. Finally, the effect of these metal complexes on the post-acidification process was also assessed. The detailed findings of this study are presented and discussed in the following sections.

2. Materials and Methods

Chitosan of viscosity-average molecular weight 200 kDa and degree of acetylation 8% was purchased from Bioprogress (Moscow, Russia). Manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate was from Reachim. Other chemicals and solvents were also obtained from commercial sources and used as received without any further purification.

The apparent hydrodynamic radii and the ζ-potential of the nanoparticles in water were estimated at room temperature (about 25 °C) by using a Photocor Compact-Z instrument (Russia) at λ = 638 nm, θ = 90° for radii (10 scans, each one for 10 s) and θ = 20° for the ζ-potential (3 scans, each one for 60 s).

The pH was measured potentiometrically by using a PHS-3C device (China).

Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy measurements (ICP) were performed with a Leeman ICP-AES Prodigy XP spectrometer.

The IR spectroscopy was recorded on a Shimadzu IRSpirit at a wavenumber range of between 4000 to 400 cm−1.

An X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out on a Dron-7 X-ray diffractometer, using a 2θ angle interval from 5° to 50° with scanning step ∆2θ = 0.02° and exposure of 3 s per point. Cu Kα radiation (Ni filter) was used, which was subsequently decomposed into the Kα1 and Kα2 components during the processing of the spectra.

Differential thermal analysis (DTA) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) were performed on the SDT Q600 by using a heating rate of 10 °C/min in the temperature range from 30 °C to 600 °C.

For the preparation of chitosan/Mn(II) complexes, chitosan (0.025 g) was dissolved in 25 mL of 1% CH3COOH and stirred for 30 min with a mechanical stirrer. MnCl2×4H2O (0.1979 g) was dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water and stirred for 30 min to obtain a 0.2M solution. The Mn(II) salt solution was poured as a thin stream into the vigorously stirred solution of chitosan to obtain 1:2, 1:1, or 2:1 mono-mol/mol polymer/Mn2+ ratio solutions, and the resulting mixtures were intensely stirred for 5 min. The resultant suspensions were frozen and freeze-dried.

A whole milk purchased from Neva-Milk Company was used for the milk experiments. 1000 mL of the whole milk was poured into a flat-bottomed flask and 4.64 mg MnCl2×4H2O, 12.30 mg Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2), 8.12 mg Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1), or 6.13 mg Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) was added to the milk and stirred over 20 min under room temperature. Thus, different amounts of the samples to be tested which contain the same mass of Mn2+, i.e., 1.30 mg were added. The flasks were charged by Streptococcus thermophilus (St. thermophilus, 20 g per 1000 mL of the milk) and treated for 8 hours at 42°C for fermentation. For the pH monitoring, 50 mL of milk was taken at: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 hours of the fermentation experiment. When the pH value decreased to 4.60, the fermentation was considered complete. The remaining fermented milk was immediately cooled to stop the fermentation process and was used in further experiments.

For the post-acidification assessment, the cooled fermented milk was kept in a plastic, i.e., sterile plastic yogurt containers (1 portion was 85 mL) at 25°C. pH and the number of colony-forming units (CFU) of St. thermophilus monitoring were determined every 24 hours for one week. For the determination of the CFU, 25 mL of fermented milk was poured into 200 mL of 0.15% peptone water. Tenfold dilutions were used for the inoculation on a nutrient medium (tryptone, sucrose, yeast extract, potassium hydrophosphate, pH = 6.8). Colonies were counted after the incubation of the inoculations at 37°C for 24 hours.

The statistical significance of differences between the samples was determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by using the JMP 5.0.1 software (SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC, USA). The mean values, where appropriate, were compared by applying the Student’s t-test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of complexes

For the synthesis of chitosan/manganese complexes, a high molecular weight chitosan (200 kDa) was used. Since high molecular weight chitosans are insoluble in water, a 1% acetic acid was used as a solvent for the synthetic procedures was used. As a source of the metal center (Mn2+ ions), a highly water-soluble manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate was chosen. The polymer/Mn2+ ratio was 1:2, 1:1, or 2:1 mono-mol/mol.

All resultant chitosan-based complexes (named

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2),

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1), and

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1)), yielded transparent suspensions (

Figure 1, B). After the freeze-drying process, the complexes appeared as fine pale porous cotton-like materials (

Figure 1, C). The synthesized complexes are easily redispersed in water after the freeze-drying procedure. The resultant suspensions are stable for a month and then, they undergo a gradual coagulation process. The ICP analysis confirmed the quantitative content of manganese in the samples.

3.2. Dynamic and electrophoretic light scattering studies

The stability of the suspensions was largely determined by the size of dispersed microparticles and their zeta potential [

35]. Generally, a decrease in the hydrodynamic diameter of microparticles results in an increase in the stability of their suspensions [

36]. Zeta potential is an extremely important indicator of the stability of microparticles in a liquid medium. A high (ca. 25 mV and more) absolute value of the zeta potential determines increased stability of the colloidal system, i.e. micro-suspension [

37].

Herein, the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the prepared chitosan-based complexes were evaluated immediately after synthesis, after redispersion, and during 150 days of suspension in the dark at 5°C.

Analysis of the starting chitosan solution by dynamic light scattering, expectedly showed a rapidly changing pattern of polymodal size distribution with sharply-changing intensities and peak positions. This fact is not surprising and it is explained by changes in the sizes of macromolecular coils as a result of thermal motion due to pronounced segmental mobility, as well as molecular mass and compositional heterogeneity of chitosan [

38].

Almost immediately after mixing the chitosan and Mn(II) salt solutions, the situation changed dramatically,

viz: the unimodal size distribution with constancy of intensity and peak position was detected. These changes indicated the formation of chitosan-metal complexes. Thus, a few minutes after mixing, starting with chitosan and manganese chloride solutions, the reaction mixtures gave rise to microparticles with a hydrodynamic diameter of ca. 150 nm for

Chitosan + Mn2+ 1:2, ca. 274 nm for

Chitosan + Mn2+ 1:1, and ca. 174 nm for

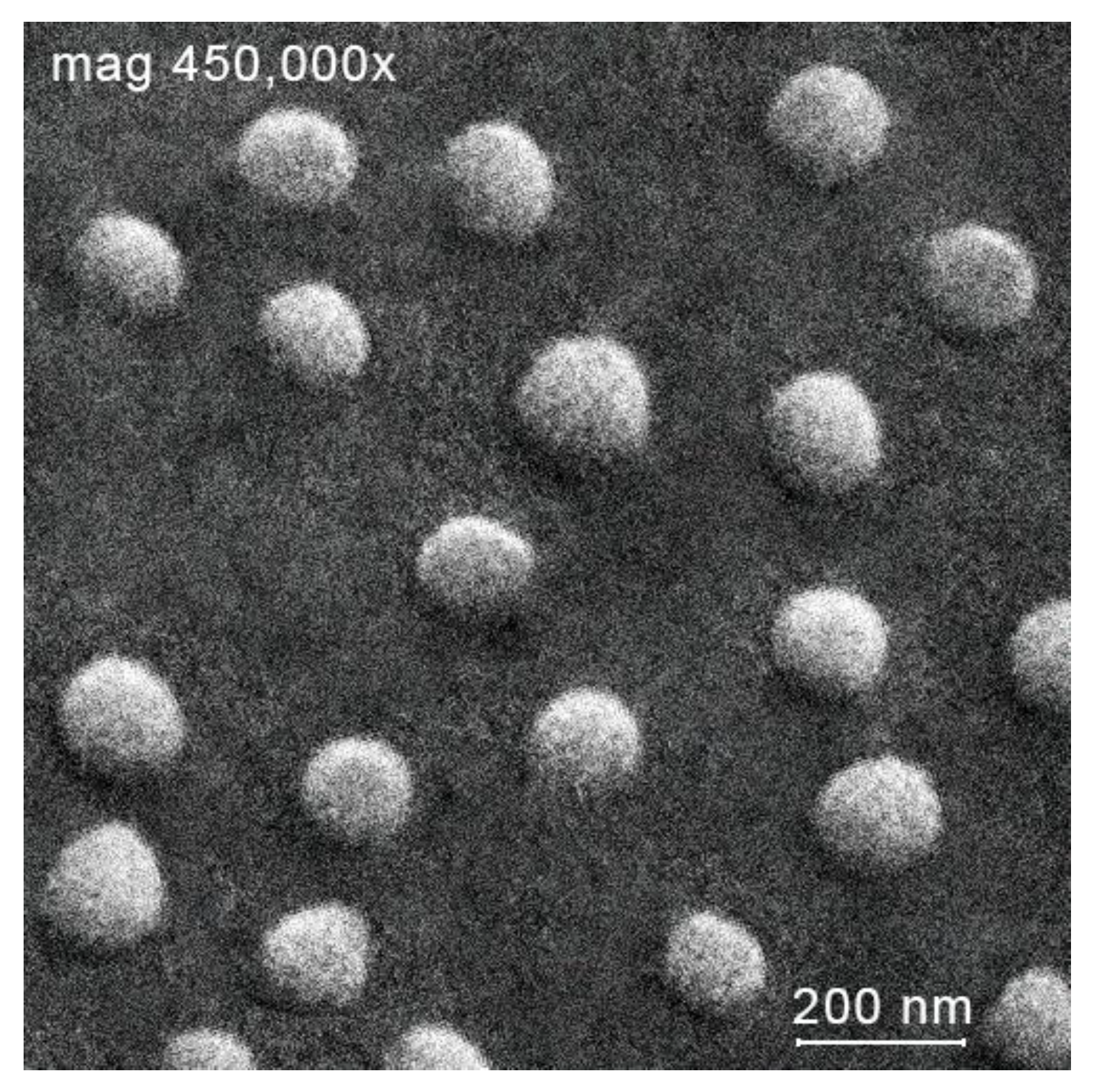

Chitosan + Mn2+ 2:1 with unimodal size distribution. Scanning electron microscopy (see example in

Figure 2) confirmed the unimodal distribution and showed the spherical shape of the resultant microparticles. All formed microparticles had a relatively high positive zeta potential value. (ca. 20 mV

for Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2), ca. 30 mV for

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1), and ca. 20 mV for

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1)). After lyophilization, the prepared microparticles completely recover their size, shape and zeta potential within 30 min, and this indicated their high re-dispersibility.

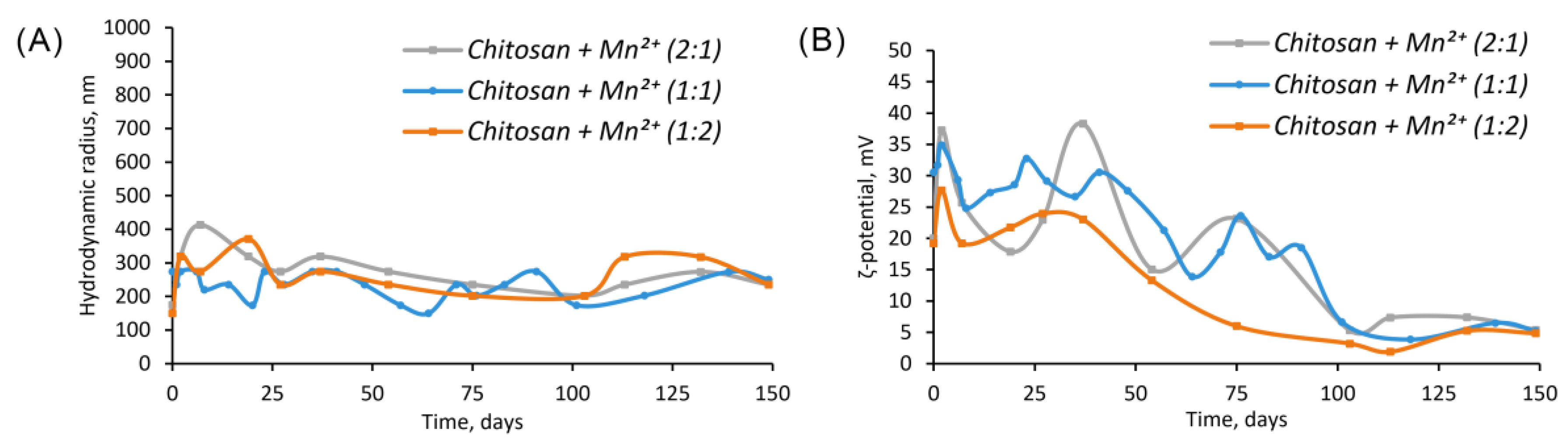

The value of the hydrodynamic radius was relatively constant and fluctuated around 273±64 nm (

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1)), 233±41 nm (

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1)) и 261±63 nm (

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2)) during the experiment (150 days,

Figure 3, A).

The zeta potential of the microparticles was more subjected to fluctuations than their sizes, the zeta potential of all microparticles of the complexes obtained, tended to change over time from 37 mV (2 days) to 5 mV (150 days) for

Chitosan + Mn2+ 2:1, from 35 mV (2 day) to 5 mV (150 day) for

Chitosan + Mn2+ 1:1, and from 37 mV (2 day) to 5 mV (150 day) for

Chitosan + Mn2+ 2:1 (

Figure 3, B).

A month after the start of the experiment, a gradual weakening in turbidity and coagulation as a result of the monotonous destabilization of the complexes due to a decrease in the aggregate stability of the particles was observed. The aggregate stability, in turn, decreased due to a decrease in the absolute value of the ζ-potential (

Figure 3).

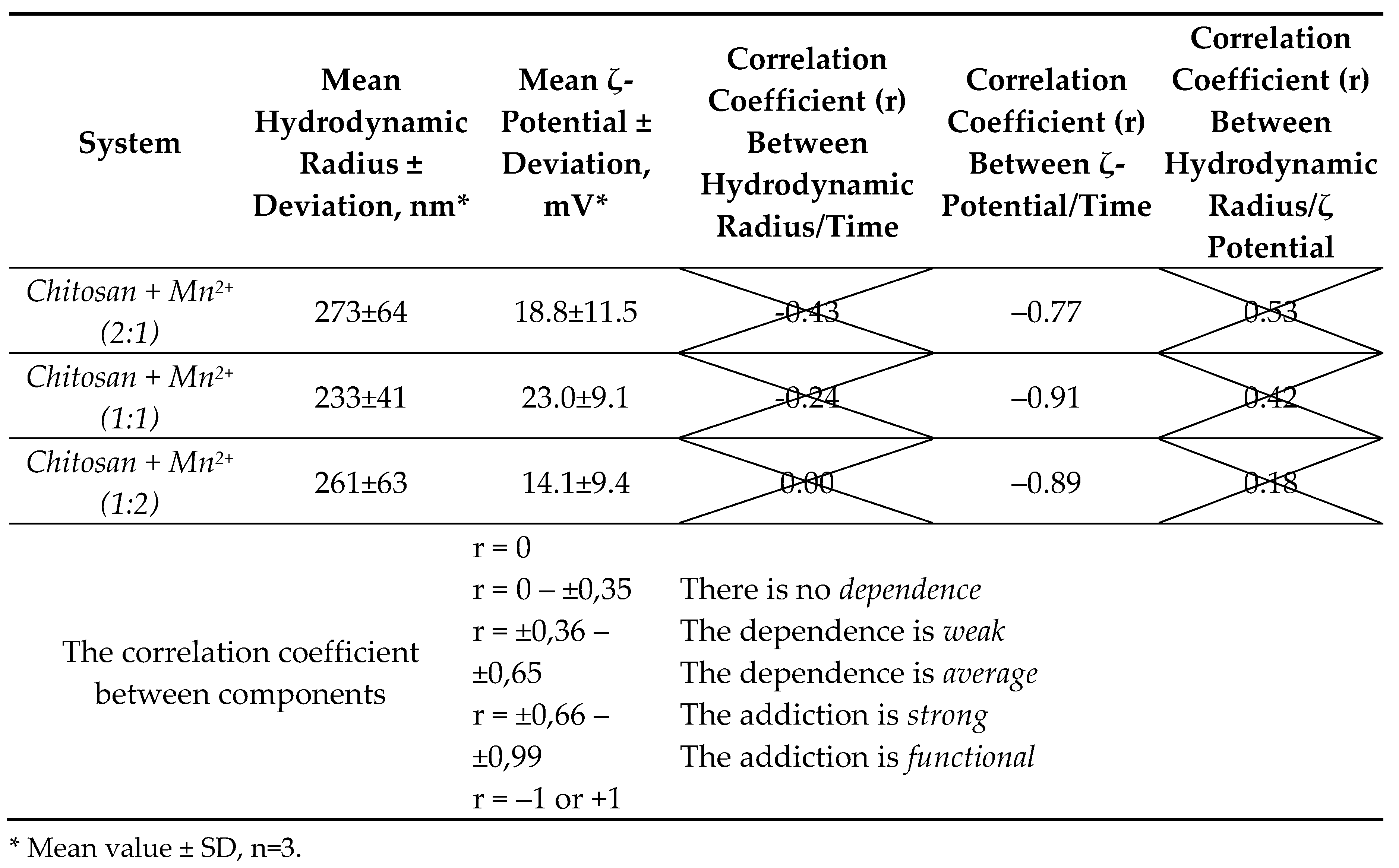

Table 1 summarizes the statistical and correlation analysis data for the components “hydrodynamic radius–time”, “ζ-potential–time” and “hydrodynamic radius–ζ-potential” over 150 days of the experiment.

Statistical and correlation analyses of experimental data showed that there is no relationship between the parameters: “hydrodynamic radius” and “time”, as well as the “hydrodynamic radius” and the “ζ-potential” for the microparticles of the synthesized complexes since the p-value is unreliable (p < 0.05) and poorly describes the nature of the relationship between these quantities. In addition, the correlation coefficients have a low value (r < 0.65). Statistically unreliable values of the correlation coefficient (crossed out in the table) at p < 0.05 for the obtained systems meant the absence of any statistically significant relationship between the parameters, which in turn also meant the impossibility for further mathematical processing and functional approximation.

On the contrary, there was a clear statistical dependence between the parameters: “ζ-potential” and “time”. All the microparticles of the synthesized complexes are described by a medium-strong inverse dependence, which indicated a statistically reliable decrease in the value of the ζ-potential over the post acidification time. A strong correlation dependence (r = ±0.66 – ±0.99) presupposes the possibility of approximating the value of the ζ-potential from time by a mathematical function.

The obtained results indicated that the synthesized systems were not in equilibrium. This can be explained by the rearrangements in the polymer chain of chitosan, for example, the processes of the gradual depolymerization of the macromolecule, reactions of a rare cross-linking, the partial oxidative destruction of chitosan, etc. The Mn(II) center, in turn, can also affect the stability of the polymer-metal systems (competitive interaction of the solvent molecules with the metal center, can change in the reactivity of the ligand [

39]).

The obtained systems are considered as potential extenders of the shelf life of products based on fermented milk (e.g. yogurts). The conventional shelf life of such products is between 7–10 days. The microparticles of the synthesized complexes were stable for at least a month, therefore, it is believed that they are appropriate for the intended purpose. However, since the complexes are non-equilibrium systems, they should be produced as a lyophilizate and re-dispersed immediately, before use.

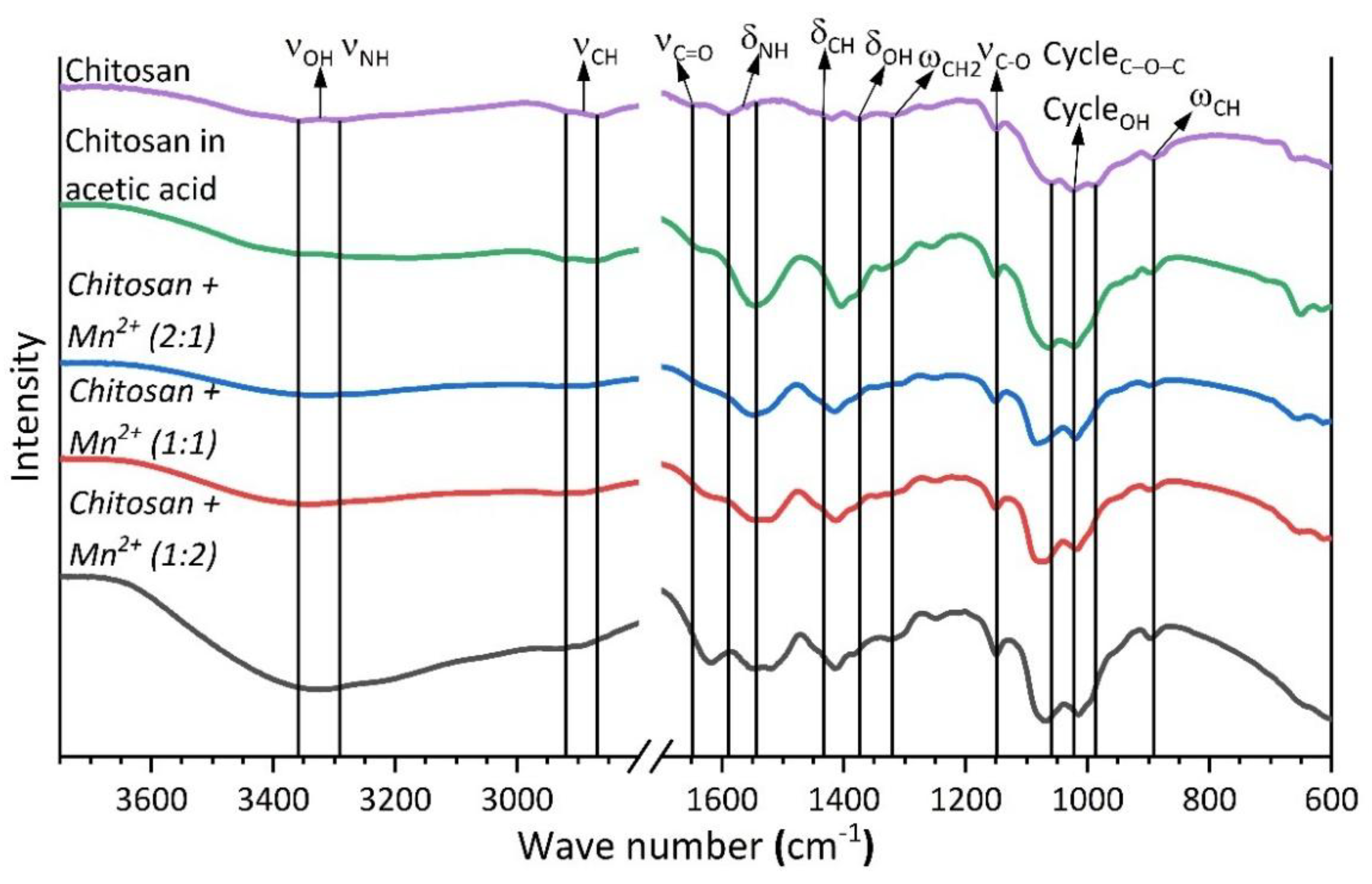

3.3. FTIR analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to further investigate the interactions between chitosan and the Mn(II) center in the complexes prepared. A set of previously published data [

39,

40,

41] was used to identify the absorption bands in the spectra obtained (

Figure 4). The wave numbers of the absorption maxima are presented in

Table 2.

The coordination of chitosan to the Mn(II) center did not cause any noticeable change in the positions of the characteristic bands due to the vibrations of the C–O–C bonds of the pyranose ring and the ring-bound O–H groups (∆ 10 cm

-1). However, the interaction of chitosan with Mn

2+ resulted in a noticeable shift of the C=O group vibration band (∆ 30 cm

-1) and the vibration bands of the N–H and C–H bonds, and also the O–H bonds that are not bounded directly to the pyranose ring (∆ 5–15 cm

-1 for deformation vibrations, ∆ 50 cm

-1 for stretching vibrations of the N–H, O–H bonds, and ∆ 20 cm

-1 for stretching vibrations of the C–H bonds). These results indicated that the coordination of chitosan to the Mn(II) center through the C=O, N–H, and not bounded directly to the pyranose ring O–H functional groups [

42,

43,

44].

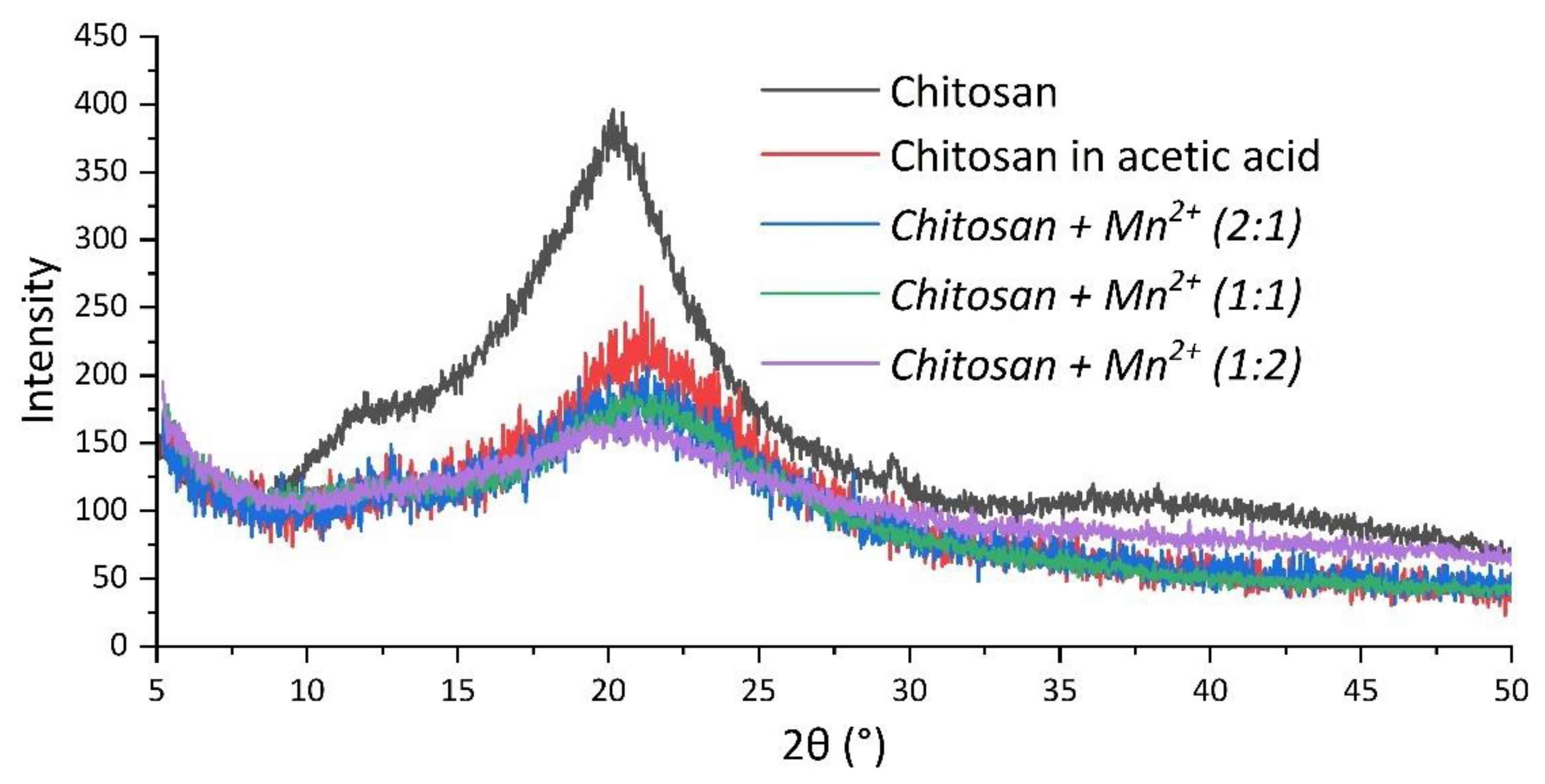

3.4. X-ray diffraction studies

The complexes were also characterized by the X-ray diffraction technique for structural analysis (powder diffraction). The diffraction patterns (

Figure 5) demonstrated the fact that the complexes, as well as the starting chitosan, were amorphous in nature.

The diffraction patterns also showed a change in the peak profile of chitosan in the sample after dissolution in acetic acid when compared to the starting polymer. A shift in the main peak of chitosan was observed, indicating a rearrangement of the polymer structure because of the formation of chitosan acetate [

45,

46]. After the interaction of chitosan with Mn(II) chloride, no peaks in the diffraction patterns of the complexes were observed, corresponding to the original salt. Thus, the obtained chitosan/manganese systems were homophase.

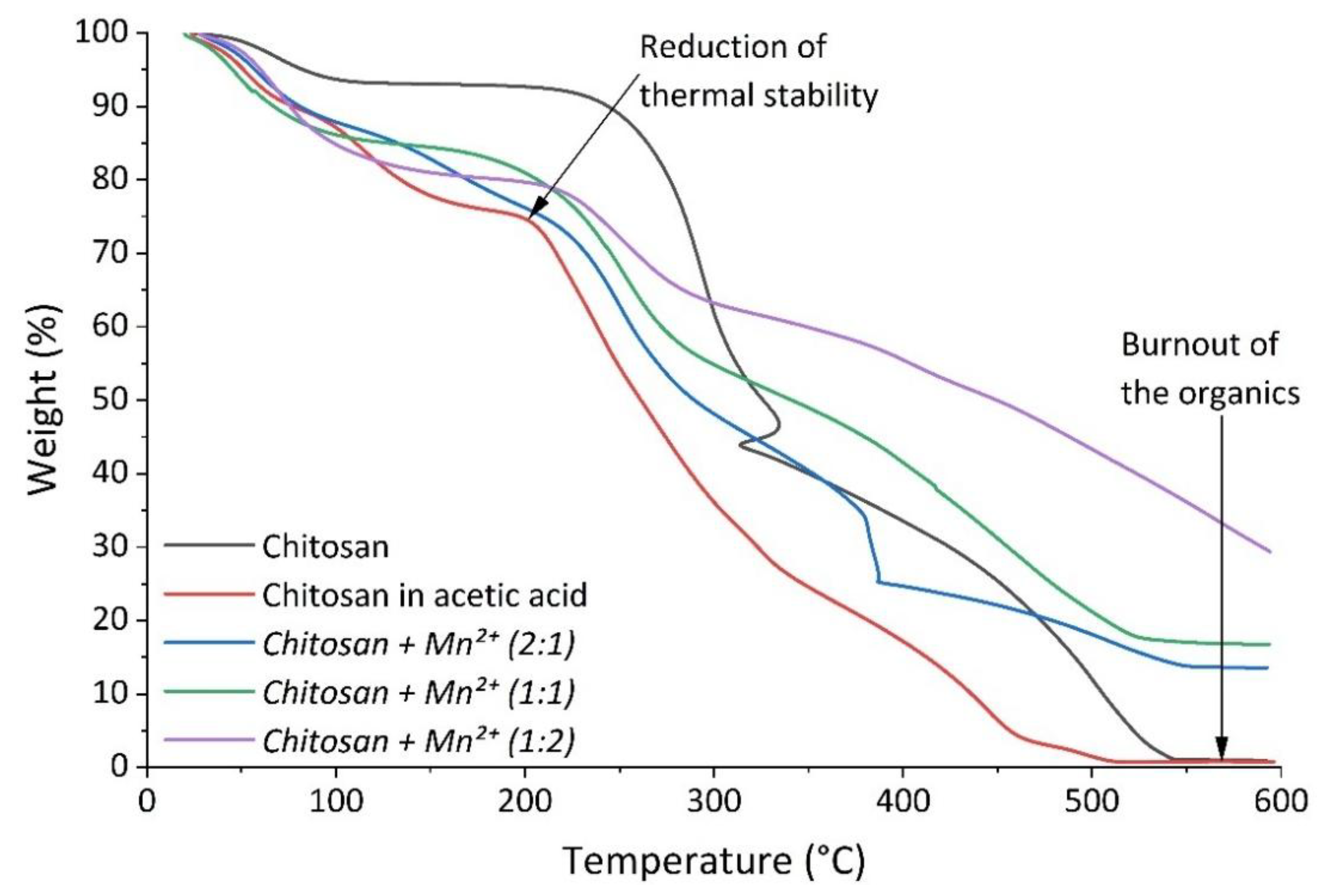

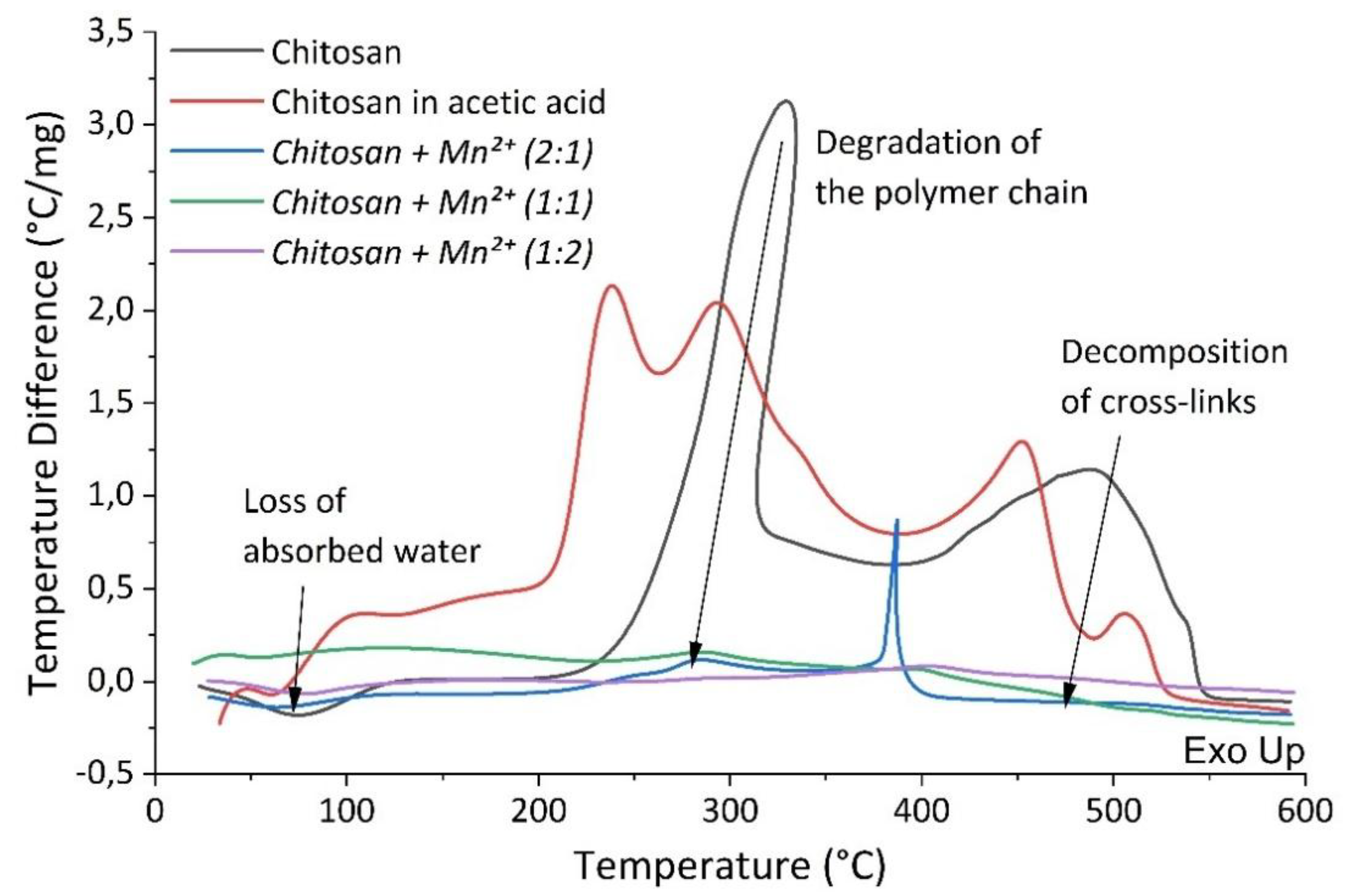

3.5. Differential thermal and thermogravimetric analysis

Differential thermal and thermogravimetric analysis were employed to study the thermal stability of the sample complexes and to evaluate the effect of the introduction of Mn

2+ ions into the polymer matrix. Thermograms of the synthesized complexes (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) showed that the decomposition of the chitosan moiety occurred in two main stages [

47,

48,

49,

50].

The first stage happened at a temperature of ~60°C and it was characterized by a mass loss of between 7% to 20%. This stage was accompanied by an endothermic effect due to the evaporation of water bound to the polymer matrix and/or coordinated to the Mn(II) center [

51].

Table 3 demonstrates a marked increase in water content in the complexes associated with an increase in manganese content. This was not surprising since the Mn(II) center prefers to coordinate to the so-called hard Lewis ligands, primarily H

2O.

The second stage begun at ca. 225 °C and continued up to 580 °C. This stage resulted in a mass loss of ~92% for Chitosan, ~73.29% for

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1), ~67.95% for

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1), and ~50.81% for

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2). This was associated with the gradual destruction of the polymer chain and the burning of its decay products. The destruction of chitosan was manifested by the cleavage of glycosidic bonds, then the resulting oligomers decomposed with the subsequent formation of acetic, butyric acids, as well as lower fatty acids [

48].

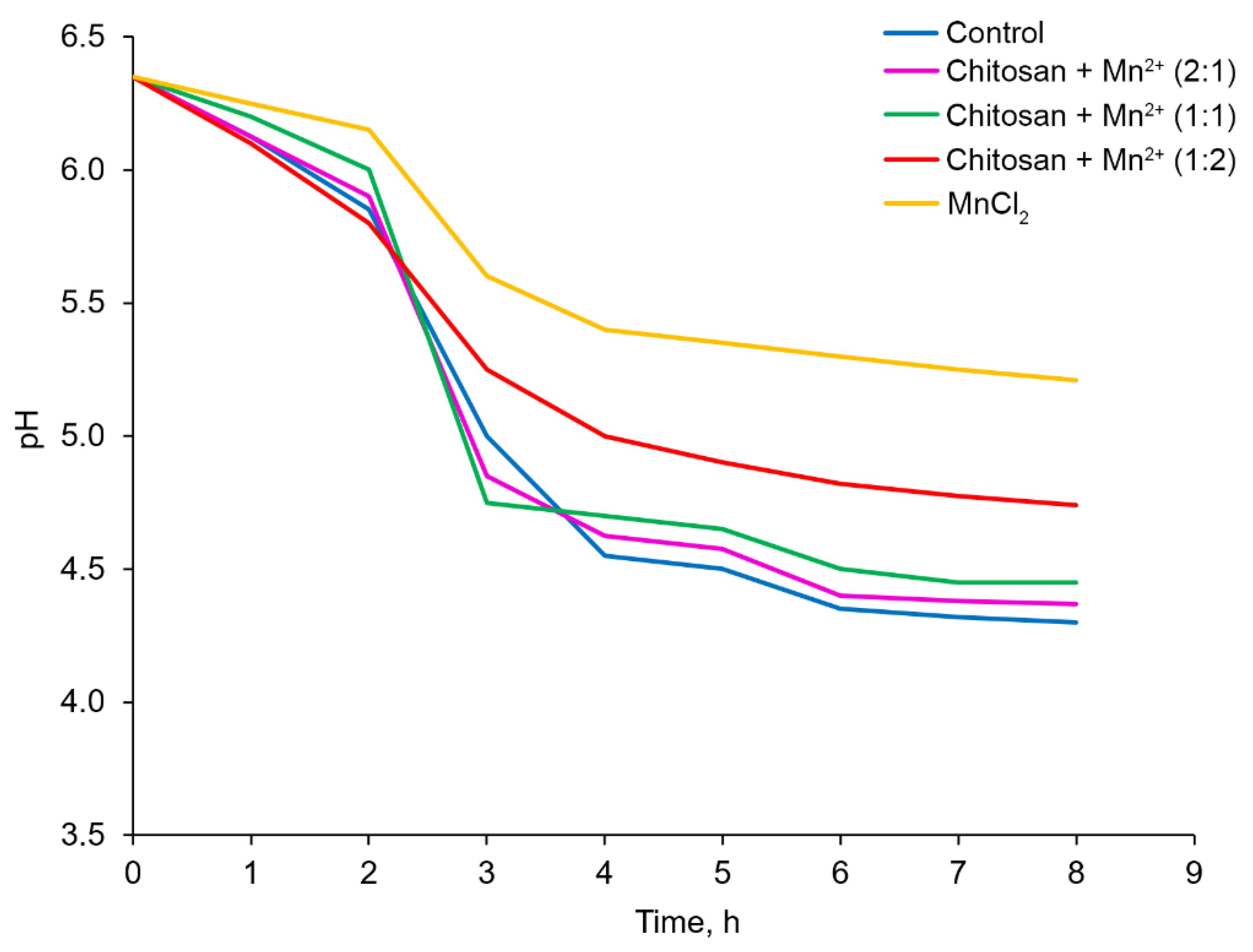

3.6. Fermentation kinetics and pH changes

At the first stage, the effect of the obtained Chitosan–Mn

2+ systems (

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1),

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1) and

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2)) on fermented milk pH changes and the fermentation kinetics were investigated. The effects of the synthesized systems with manganese chloride were compared. In the investigations, different masses of the tested samples containing the same amount (1.3 mg per 1000 mL of milk) of Mn

2+ cations were employed. In addition, a blank experiment which excluded the use of any additives were carried out. The rate and depth of pH changed dramatically depending on the type of additive used. The results of the experiment are shown in

Figure 8. The highest rate of the pH decrease was observed in the case of the control experiment, i.e. without any additives. Eight hours after the start of the fermentation experiment, the pH value reached 4.30. Mn(II) chloride caused the least acidification of milk in the same period of time (pH = 5.21). According to their ability to reduce the pH of fermented milk, the Chitosan–Mn

2+ systems were arranged in the following order:

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2) (pH after 9 hours 4.74) <

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:1) (pH after 8 hours 4.45) <

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) (pH after 8 hours 4.37). Since the amount of Mn(II) was the same in all the tested systems, the observed effect was related to the amount of chitosan: the greatest acidification of fermented milk was caused by the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (

2:1) system that contained the largest amount of chitosan (

Figure 8).

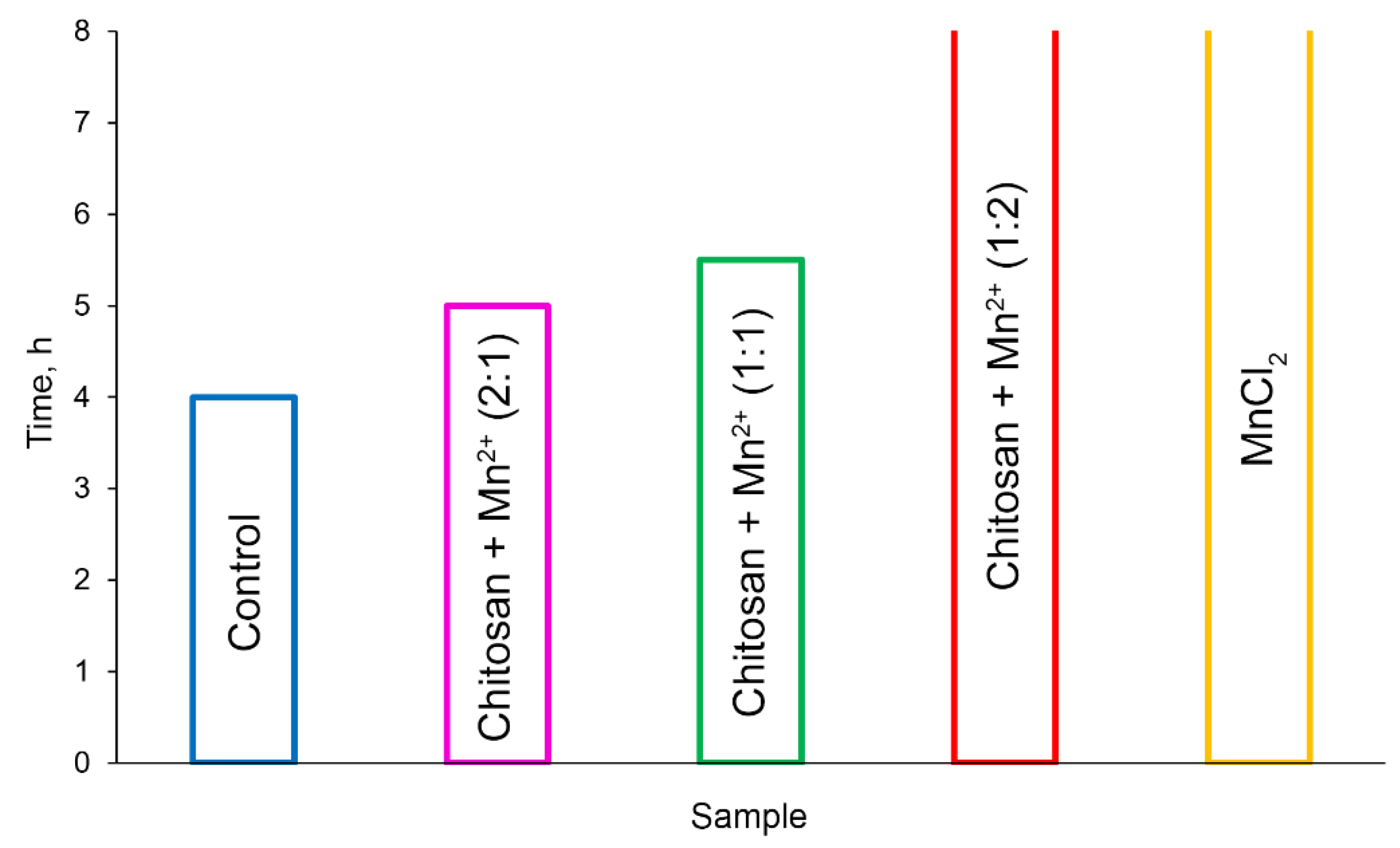

A similar pattern for the milk fermentation time was observed. The fermentation time was considered to be achieved when the pH reached 4.60 [

52,

53]. The fermentation time was found to be inversely proportional to the fermentation rate. The shortest fermentation time (

Figure 9) was observed in the control experiment and in the case of using the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system (4 hours and 5 hours, respectively).

Figure 9 displays the fact that the fermentation rate decreased with a decrease in the chitosan content in the system. For the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (1:2) system and the manganese chloride, the fermentation time was more than 8 hours.

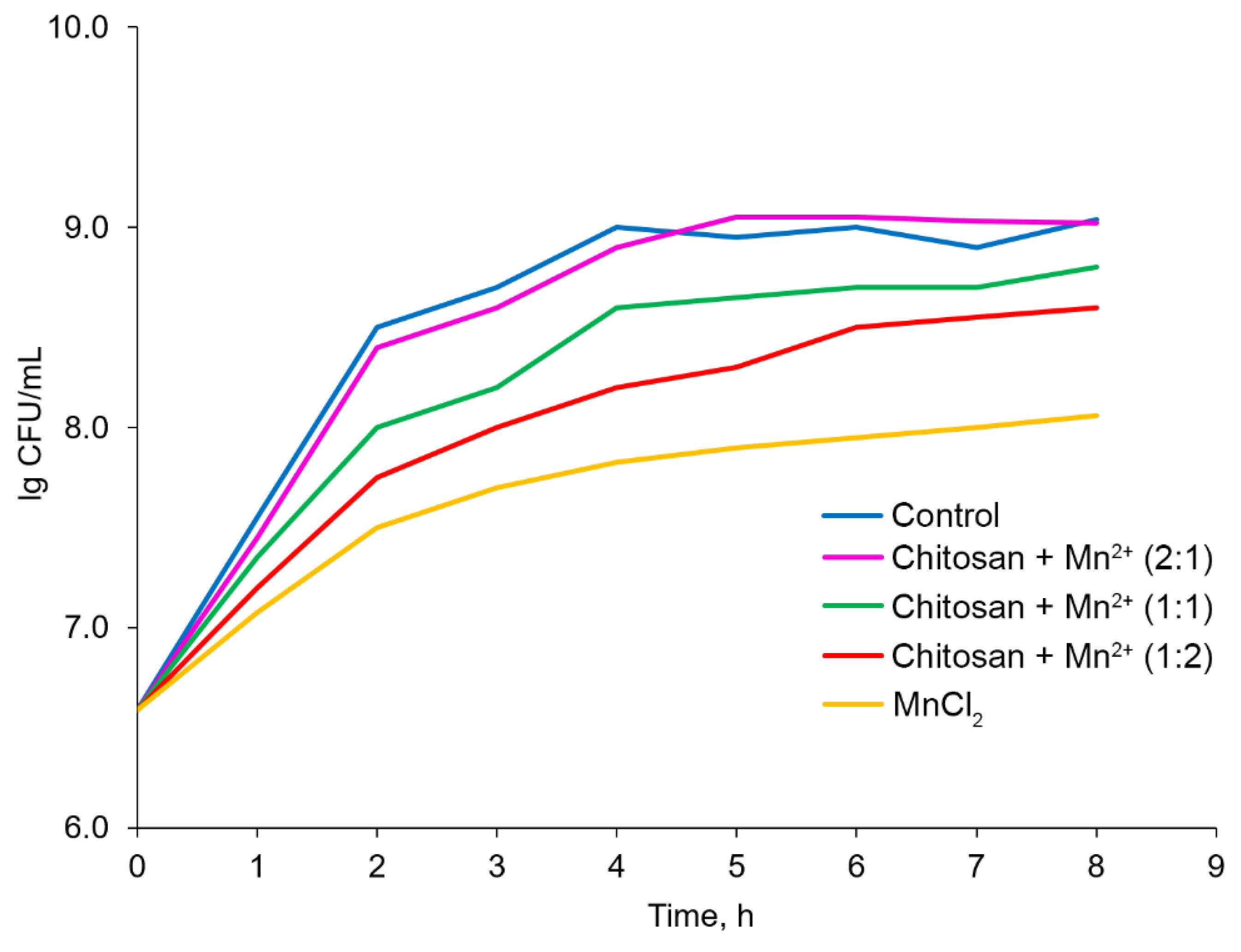

3.7. Dynamics of CFU number changes during fermentation

At the next stage, the ability of the additives to influence the number of colony-forming units (CFU) producing bacteria

St. thermophilus in the fermented milk in comparison with the control experiment (without any additives) was assessed. The initial number of CFU in milk was 3.93×10

6 CFU/ml. Over 8 hours of the experiment, the maximum increase in the number of CFU was achieved in the case of the control experiment; the number of CFU/ml increased to 1.12×10

9. The use of

Chitosan + Mn2+ 2:1 for fermentation led to a similar result (1.04×10

6 CFU/ml). At the same time, the graphical dependence of lg CFU on time under the influence of the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system was close to that for the control experiment; even though the analysis of variance did not reveal any significant differences between the trends of these two curves (

Figure 10). Mn(II) chloride recorded a pronounced inhibitory effect on the growth of producing bacteria. Under the action of MnCl

2, an increase in the CFU/ml value achieved was only up to 1.17×10

8, which was an order of magnitude less than in the case of the control experiment or

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system was achieved. The other tested Chitosan–Mn

2+ systems demonstrated intermediate positions. Their tendency to inhibit the growth of

St. thermophilus in fermented milk increased with decreasing chitosan content. Thus, the results obtained were consistent with those for changing the pH and fermentation time: the tested additives with the highest chitosan content, not only caused the greatest souring of milk with the highest fermentation rate but also determined the highest growth rate of

St. thermophilus. This result was consistent with the views that the fermentation kinetics was associated with the growth of

St. thermophilus [

54,

55].

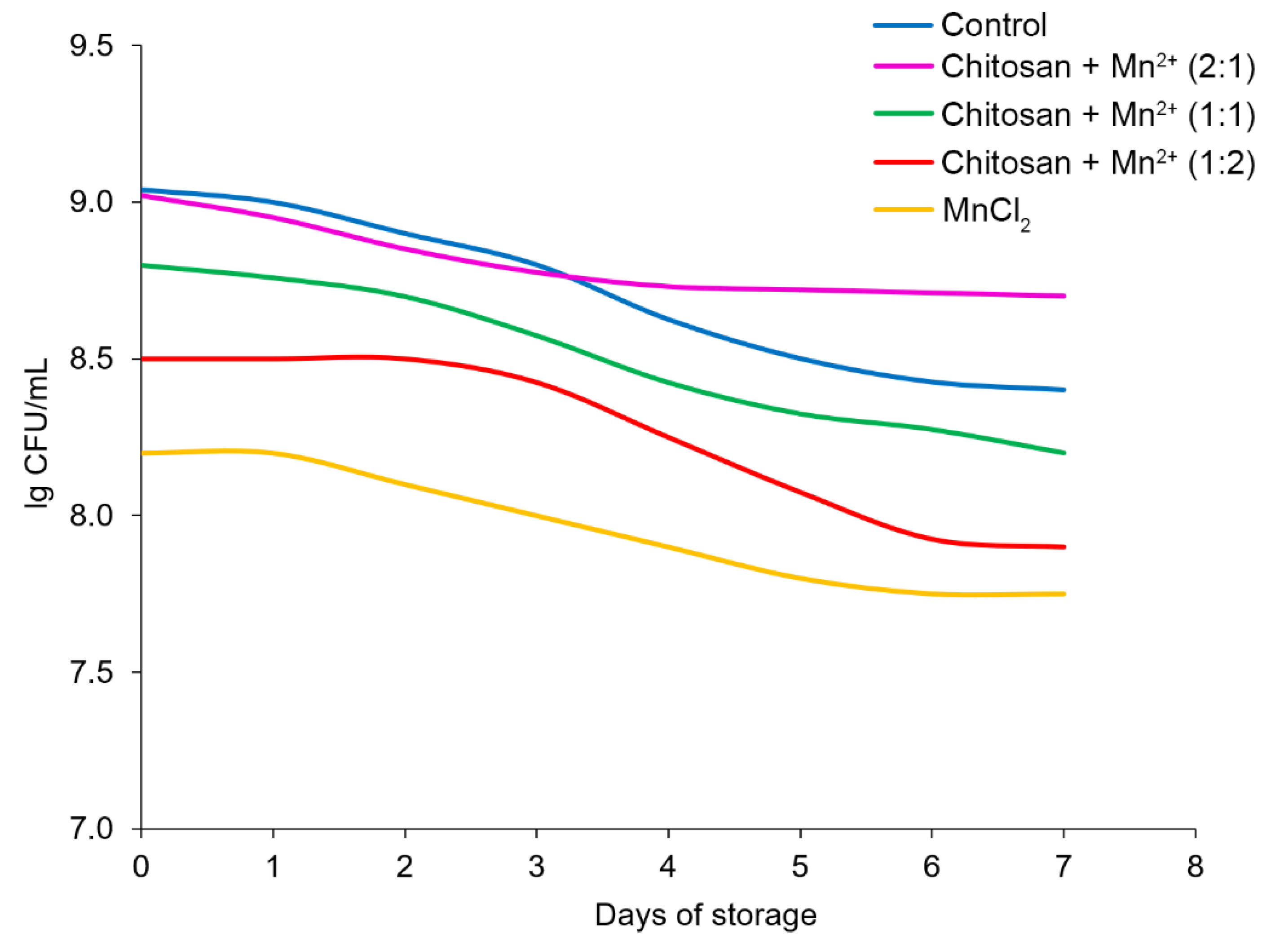

3.8. Dynamics of changes in the number of CFU and pH of the fermented product during storage

In the final stages of the experiments, the change in the pH and the number of CFU during the storage of fermented milk for 7 days monitored when conducting the experiments under thermostatted conditions at 25°C. The number of the CFU/ml, decreased during the experiment, but this trend was different for the tested samples, depending on the additive (

Figure 11). In the control experiment, the CFU/ml value decreased from ~10

9 to ~10

8.4, thereby demonstrating a pronounced and almost linear downward trend. Under the influence of the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system, a less pronounced tendency to decrease in the number of producing bacteria was observed and the CFU value decreased only from ~10

9 to 10

8.7, with the main decrease observed in the first 3 days of the experiment, and subsequently, the level of the

St. thermophilus remained relatively constant, with a tendency only to an insignificant monotonic decrease. In the case of the other additives, the level of the bacteria decreased significantly, and this effect was most pronounced for the so-called “pure” manganese chloride.

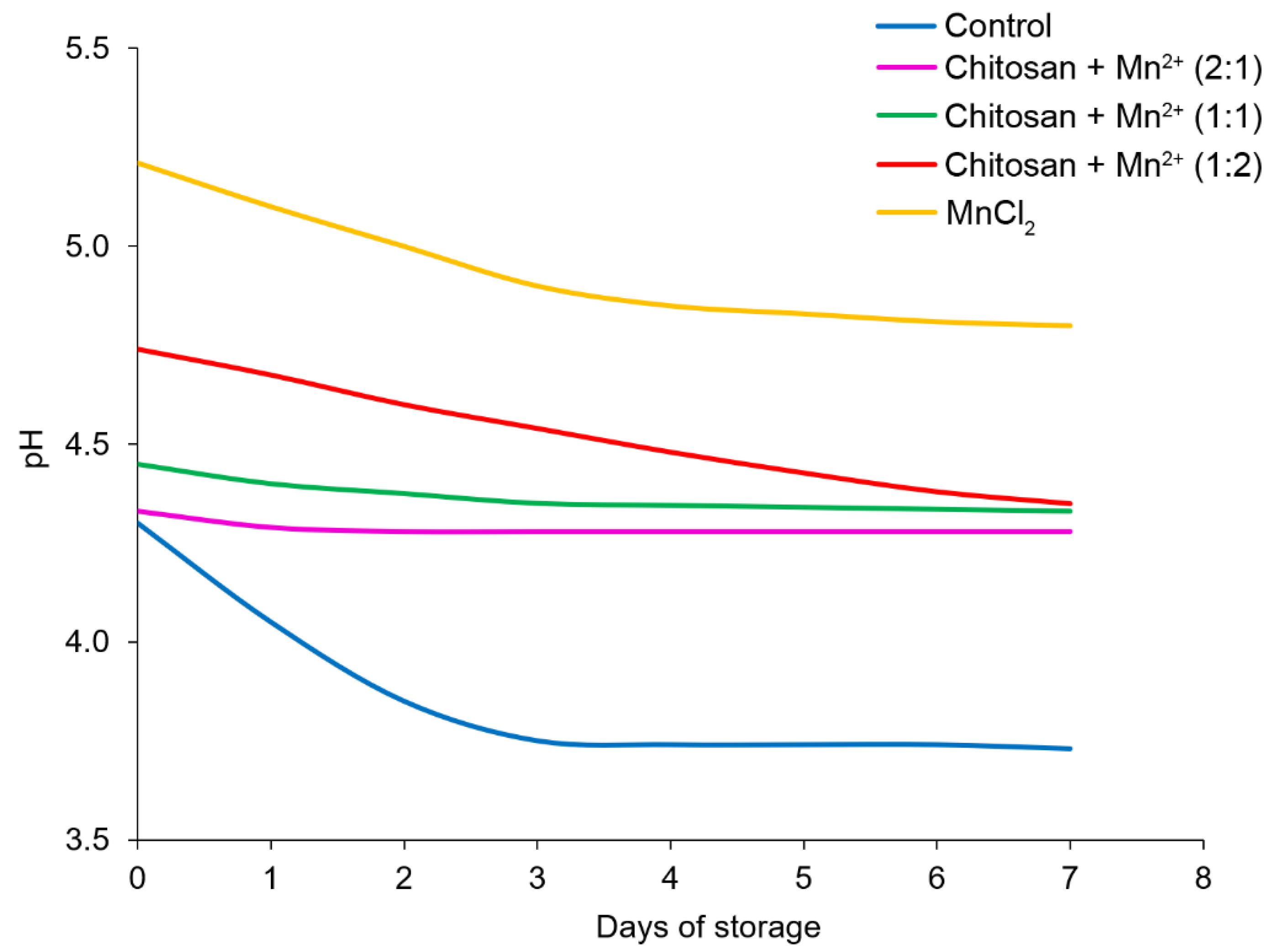

The patterns of the pH changed in the fermented milk, during storage were similar (

Figure 12). In all cases, a decrease in pH despite a decrease in the number of bacteria was observed. This effect can be explained by the growth of other microorganisms that caused the so-called “post-acidification” of the fermented milk, as well as a cascade of side biochemical reactions [

53].

A maximum post-acidification was observed in the control experiment. This resulted in the product becoming unsuitable on the 4th day of storage at 25 °C, since the pH of the product attained an undesirable value – below 4.4 [

53,

56,

57]. The best result was achieved by using the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system as an additive; the pH level was almost the same with a slight, but insignificant tendency to decrease. Thus, the fermented milk retained its shelf life by almost 2 times longer when compared to the control when using the

Chitosan + Mn2+ (2:1) system.

4. Conclusions

The results of this work can be considered from the following perspectives.

1) Development and Characterization of Nanoparticles:

The synthesis and fully characterization of nanoparticles based on chitosan and Mn(II) ions in various molar ratios: Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (1:2), Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (1:1), and Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (2:1) was successfully achieved;

These nanoparticles exhibited microscale sizes and that their zeta potential in aqueous medium progressively decreased indicating sedimentation instability;

XRD analysis confirmed that the nanoparticles were homophase systems. ICP analysis verified the quantitative manganese content, while IR spectroscopy and DTA-TG analysis demonstrated the coordination of Mn(II) to the chitosan matrix.

2) Stimulation of Milk Fermentation:

Among the tested systems, the Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (2:1) complex exhibited the ability to enhance the fermentation of the medium more effectively than the other ratios;

Thus, this system significantly reduced the milk fermentation time, demonstrating its efficiency in promoting faster fermentation.

3) Shelf-Life Assessment of Fermented Milk Products:

Over a 7-day storage period, the Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (2:1) system exhibited the least pronounced decline in colony-forming units (CFUs) of Streptococcus thermophilus;

The pH of the fermented milk products treated with this system remained nearly constant, with only a slight decrease, indicating enhanced stability;

Using the Chitosan + Mn²⁺ (2:1) system nearly doubled the shelf life of fermented milk products compared to the control.

Finally, the synthesized nanoparticles are promising candidates for further biological studies, both in vitro and in vivo. Ongoing research in our group aims to explore their broader biological applications and potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.N., L.V.N. and A.S.K.; methodology, A.A.N., D.I.S., G.Z.M. and A.A.K.; software, N.N.L. and I.S.K.; validation, A.V.K., R.M.M., E.R.S., O.C.A., G.J.A. and W.L.; formal analysis, N.N.L. and I.S.K.; investigation, G.Z.M. and A.V.K.; resources, A.G.T., I.S.K. and A.A.K.; data curation, A.R.E. and D.I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.N., L.V.N., D.I.S. and G.Z.M.; writing—review and editing, A.V.K., N.N.L., A.G.T., I.S.K., A.A.K., R.M.M., E.R.S., O.C.A., G.J.A., A.R.E., A.S.K. and W.L.; visualization, N.N.L.; supervision, A.G.T. and A.A.K.; project administration, A.S.K and W.L.; funding acquisition, I.S.K., A.S.K. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System, project № 021341-2-000, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32311530766, 32271422, W2431042, 32411540226), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232025A-09), Shanghai Frontiers Science Center of Advanced Textiles, Donghua University (24S10102、23S10115). The research was carried out with the support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (State Assignment No. FSSF-2025-0001) within the framework of the federal project “Development of technologies for controlled thermonuclear fusion and innovative plasma technologies”. The authors are grateful to the Belarusian Republican Foundation for Fundamental Research for supporting the Belarusian-Uzbek project “Ultrasonic synthesis of composites, based on chitosan and the layered double hydroxides for the sorption of environmental pollutants” (contract T25UZB-121). The authors also thank the State Committee on Science and Technology of the Republic of Belarus (a separate project “Ultrasonic synthesis of layered double hydroxides for medical purposes”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Deshwal, G. K.; Tiwari, S.; Kumar, A.; Raman, R. K.; Kadyan, S., Review on factors affecting and control of post-acidification in yoghurt and related products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 499-512. [CrossRef]

- Guenard-Lampron, V.; St-Gelais, D.; Villeneuve, S.; Turgeon, S. L., Short communication: Effect of stirring operations on changes in physical and rheological properties of nonfat yogurts during storage. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, (1), 210-214. [CrossRef]

- Tamime, A. Y.; Robinson, R. K., Microbiology of yoghurt and related starter cultures. In Tamime and Robinson’s Yoghurt, Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007; pp. 468-534.

- Kristo, E.; Biliaderis, C. G.; Tzanetakis, N., Modelling of the acidification process and rheological properties of milk fermented with a yogurt starter culture using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2003, 83, (3), 437-446. [CrossRef]

- Donkor, O. N.; Henriksson, A.; Vasiljevic, T.; Shah, N. P., Effect of acidification on the activity of probiotics in yoghurt during cold storage. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, (10), 1181-1189. [CrossRef]

- Fenster, K.; Freeburg, B.; Hollard, C.; Wong, C.; Ronhave Laursen, R.; Ouwehand, A. C., The Production and Delivery of Probiotics: A Review of a Practical Approach. Microorganisms 2019, 7, (3), 83. [CrossRef]

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S. J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y., Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019, 8, (3), 92.

- Kumar, A.; Hussain, S. A.; Raju, P. N.; Singh, A. K.; Singh, R. R. B., Packaging material type affects the quality characteristics of Aloe- probiotic lassi during storage. Food Biosci. 2017, 19, 34-41. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A. G.; Castro, W. F.; Faria, J. A. F.; Bolini, H. M. A.; Celeghini, R. M. S.; Raices, R. S. L.; Oliveira, C. A. F.; Freitas, M. Q.; Conte Júnior, C. A.; Mársico, E. T., Stability of probiotic yogurt added with glucose oxidase in plastic materials with different permeability oxygen rates during the refrigerated storage. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, (2), 723-728. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. L.; Wang, X. L.; Liu, Z. P.; Sun, W. H.; Dai, Z. Y.; Ren, F. Z.; Mao, X. Y., Effect of α-lactalbumin hydrolysate-calcium complexes on the fermentation process and storage properties of yogurt. Lwt 2018, 88, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frías, J.; Gómez, R.; Vidal-Valverde, C., Influence of addition of raffinose family oligosaccharides on probiotic survival in fermented milk during refrigerated storage. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, (7), 768-774. [CrossRef]

- do Espírito Santo, A. P.; Perego, P.; Converti, A.; Oliveira, M. N., Influence of milk type and addition of passion fruit peel powder on fermentation kinetics, texture profile and bacterial viability in probiotic yoghurts. Lwt 2012, 47, (2), 393-399. [CrossRef]

- Varlamov, V. P.; Il’ina, A. V.; Shagdarova, B. T.; Lunkov, A. P.; Mysyakina, I. S., Chitin/Chitosan and Its Derivatives: Fundamental Problems and Practical Approaches. Biochem. (Mosc.) 2020, 85, (Suppl 1), S154-S176. [CrossRef]

- No, H. K.; Meyers, S. P.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Xu, Z., Applications of chitosan for improvement of quality and shelf life of foods: a review. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, (5), R87-R100. [CrossRef]

- El-Araby, A.; Janati, W.; Ullah, R.; Ercisli, S.; Errachidi, F., Chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and chitosan-based nanocomposites: eco-friendly materials for advanced applications (a review). Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1327426. [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, V. L.; Novinyuk, L. V., Chitosan Application in Food Technology: A Review of Rescent Advances. Food Syst. 2020, 3, (1), 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Alieva, L. R., Method of Obtaining Casein from Skim Milk using Oligochitosans. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2020, 8, (4), 331-334. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. C.; Chen, S. T.; Hsieh, J. F., Proteomic analysis of polysaccharide-milk protein interactions induced by chitosan. Molecules 2015, 20, (5), 7737-7749. [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M., Depolymerized Chitosan: A Novel Milk Protein Stabilizer. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, (6), 56. [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, D. S. W.; Kodithuwakku, K. A. H. T., Evaluation of Chitosan for Its Inhibitory Activity on Post-Acidification of Set Yoghurt Under Cold Storage for 20 Days. J. Chitin Chitosan Sci. 2014, 2, (1), 16-20. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Khanniri, E.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Khorshidian, N.; Mortazavian, A. M., Encapsulation of Heracleum persicum essential oil in chitosan nanoparticles and its application in yogurt. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1130425. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., Effect of chitosans and chitooligosaccharides on the processing and storage quality of foods of animal and aquatic origin. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 46, (1), 51-81. [CrossRef]

- Vela Gurovic, M. S.; Dello Staffolo, M.; Montero, M.; Debbaudt, A.; Albertengo, L.; Rodriguez, M. S., Chitooligosaccharides as novel ingredients of fermented foods. Food Funct. 2015, 6, (11), 3437-3443. [CrossRef]

- Afjeh, M. E. A.; Pourahmad, R.; Akbari-Adergani, B.; Azin, M., Use of Glucose Oxidase Immobilized on Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles in Probiotic Drinking Yogurt. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2019, 39, (1), 73-83. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Chitrakar, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Tian, H.; Li, C., Copper inhibits postacidification of yogurt and affects its flavor: A study based on the Cop operon. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, (2), 897-911. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, L.; Du, M.; Yi, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L., Effects of copper on the post acidification of fermented milk by St. thermophilus. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, (1), M25-M28.

- Braun, S.; Ilberg, V.; Blum, U.; Langowski, H. C., Nanosilver in dairy applications – Antimicrobial effects on Streptococcus thermophilus and chemical interactions. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2020, 73, (2), 376-383. [CrossRef]

- Duran, N.; Duran, M.; de Jesus, M. B.; Seabra, A. B.; Favaro, W. J.; Nakazato, G., Silver nanoparticles: A new view on mechanistic aspects on antimicrobial activity. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, (3), 789-799. [CrossRef]

- Cacho, J.; Castells, J. E.; Esteban, A.; Laguna, B.; Sagristá, N., Iron, Copper, and Manganese Influence on Wine Oxidation. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1995, 46, (3), 380-384. [CrossRef]

- Danilewicz, J. C., Chemistry of Manganese and Interaction with Iron and Copper in Wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, (4), 377-384. [CrossRef]

- Tariba, B., Metals in wine--impact on wine quality and health outcomes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 144, (1-3), 143-156. [CrossRef]

- Siedler, S.; Rau, M. H.; Bidstrup, S.; Vento, J. M.; Aunsbjerg, S. D.; Bosma, E. F.; McNair, L. M.; Beisel, C. L.; Neves, A. R., Competitive Exclusion Is a Major Bioprotective Mechanism of Lactobacilli against Fungal Spoilage in Fermented Milk Products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, (7), e02312-19. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Maktabdar, M., Lactic Acid Bacteria as Biopreservation Against Spoilage Molds in Dairy Products - A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 819684. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J. J.; Ahrens, M.; Smith, S., Effect of manganese on Lactobacillus casei fermentation to produce lactic acid from whey permeate. Process Biochem. 2001, 36, (7), 671-675. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Nishimura, Y.; Ikeda, M., Reactions of 1-alkylbenzimidazolium 3-imines with acetylenic-compounds and benzaldehyde. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1975, 12, (2), 225-230. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. J.; Walton, A.; Mazzeo, F. A., Suspension Stability ; Why Particle Size , Zeta Potential and Rheology are Important. Ann. T. Nord. Rheol. Soc. 2011, 20, 209-214.

- Belenkii, D.; Balakhanov, D.; Lesnikov, E., Measurement of the zeta potential. Brief review of the main methods. Analytics 2017, 34, (3), 82-89.

- Sustmann, R., A simple model for substituent effects in cycloaddition reactions. I. 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, (29), 2717-2720.

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, H., Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial activity of chitosan–Zn complex. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 56, (1), 21-26.

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Fan, L.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y., Chitosan-metal complexes as antimicrobial agent: Synthesis, characterization and Structure-activity study. Polym. Bull. 2005, 55, (1-2), 105-113.

- Nakamoto, K., Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S., 1986; p 536.

- Sustmann, R., A simple model for substituent effects in cycloaddition reactions. II. The diels-alder reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, (29), 2721-2724.

- Moyano, A.; Pericas, M. A.; Valenti, E., A theoretical-study on the mechanism of the thermal and the acid-catalyzed decarboxylation of 2-oxetanones (beta-lactones). J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, (3), 573-582. [CrossRef]

- Lecea, B.; Arrieta, A.; Roa, G.; Ugalde, J. M.; Cossio, F. P., Catalytic and solvent effects on the cycloaddition reaction between ketenes and carbonyl-compounds to form 2-oxetanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, (21), 9613-9619. [CrossRef]

- Ritthidej, G. C.; Phaechamud, T.; Koizumi, T., Moist heat treatment on physicochemical change of chitosan salt films. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 232, (1-2), 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M. Z. A.; Harun, M. K.; Ali, A. M. M.; Mohammat, M. F.; Hanafiah, M. A. K. M.; Ibrahim, S. C.; Mustaffa, M.; Darus, Z. M.; Latif, F., XRD and Surface Morphology Studies on Chitosan-Based Film Electrolytes. J. Appl. Sci. 2006, 6, (15), 3150-3154.

- Nieto, J. M.; Peniche-Covas, C.; Padro’n, G., Characterization of chitosan by pyrolysis-mass spectrometry, thermal analysis and differential scanning calorimetry. Thermochim. Acta 1991, 176, 63-68. [CrossRef]

- López, F. A.; Mercê, A. L. R.; Alguacil, F. J.; López-Delgado, A., A kinetic study on the thermal behaviour of chitosan. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 91, (2), 633-639. [CrossRef]

- de Britto, D.; Campana-Filho, S. P., Kinetics of the thermal degradation of chitosan. Thermochim. Acta 2007, 465, (1-2), 73-82.

- Wanjun, T.; Cunxin, W.; Donghua, C., Kinetic studies on the pyrolysis of chitin and chitosan. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2005, 87, (3), 389-394. [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, J.; Kaczmarek, H., Thermal treatment of chitosan in various conditions. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 80, (2), 394-400. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, A.; Acha, R.; Calleja, M. T.; Chiralt-Boix, A.; Wittig, E., Optimization and shelf life of a low-lactose yogurt with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, (7), 3536-3548. [CrossRef]

- Julijana, T.; Nikola, G.; Borche, M., Examination of pH, Titratable Acidity and Antioxidant Activity in Fermented Milk. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 6, (6), 326-333.

- Shene, C.; Canquil, N.; Bravo, S.; Rubilar, M., Production of the exopolysaccharides by Streptococcus thermophilus: effect of growth conditions on fermentation kinetics and intrinsic viscosity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, (3), 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, X.; Gai, Z., Milk fermentation by monocultures or co-cultures of Streptococcus thermophilus strains. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1097013. [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, T.; O’Mahony, J. A.; McCarthy, N. A., pH, the Fundamentals for Milk and Dairy Processing: A Review. Dairy 2023, 4, (3), 395-409. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, L.; Bulgaru, V.; Siminiuc, R., Effect of Temperature, pH and Amount of Enzyme Used in the Lactose Hydrolysis of Milk. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 12, (12), 1243-1254. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).