Submitted:

07 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

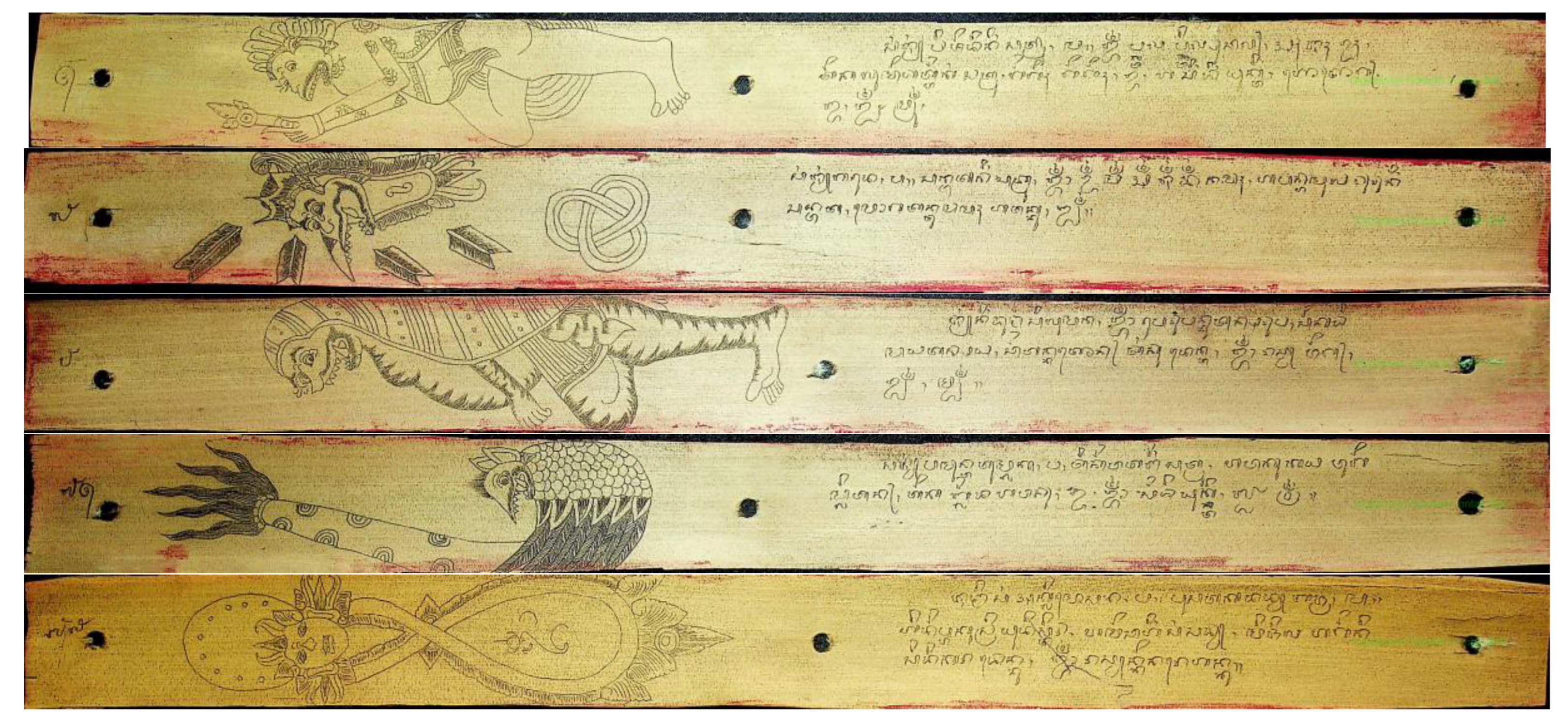

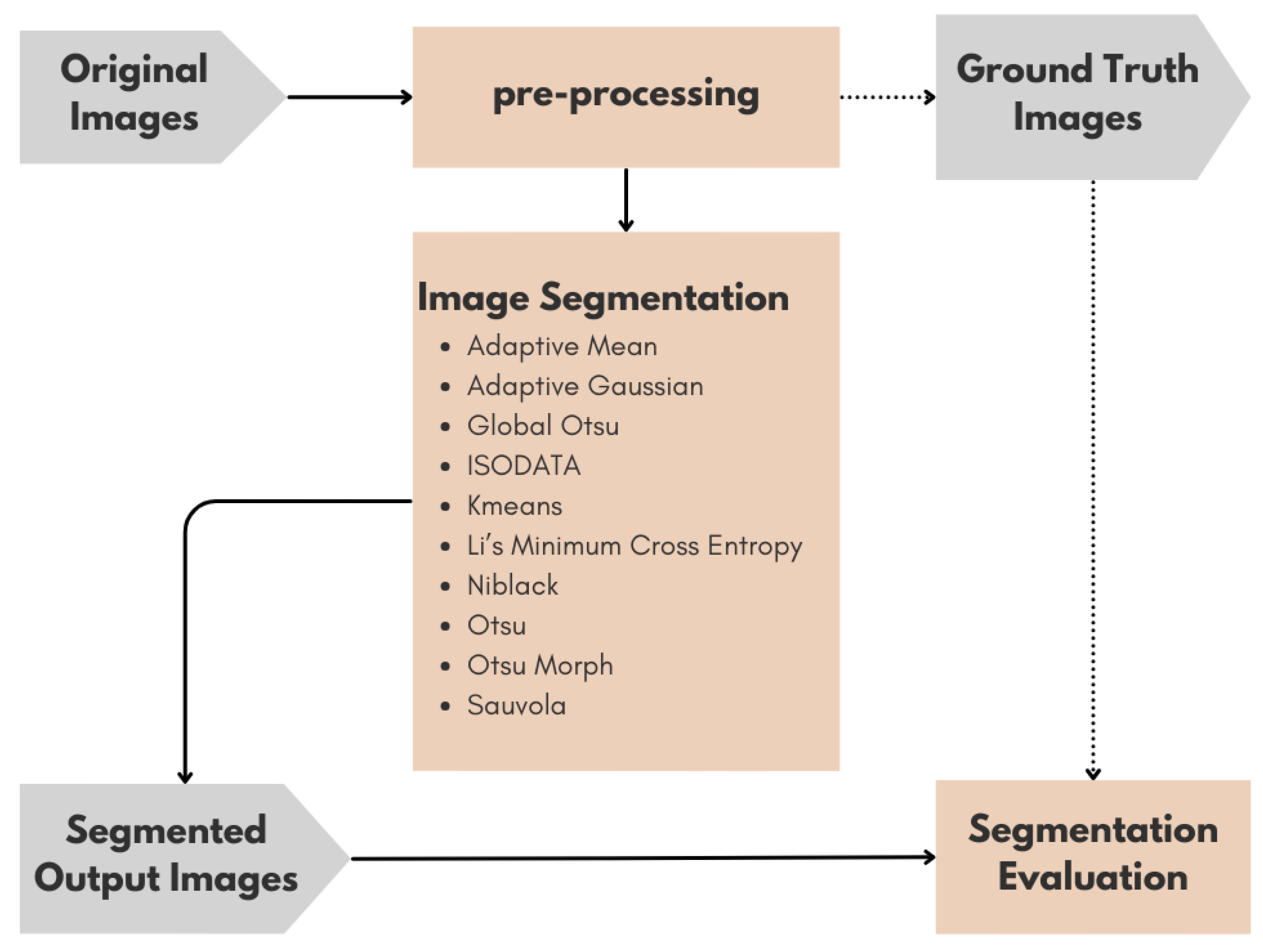

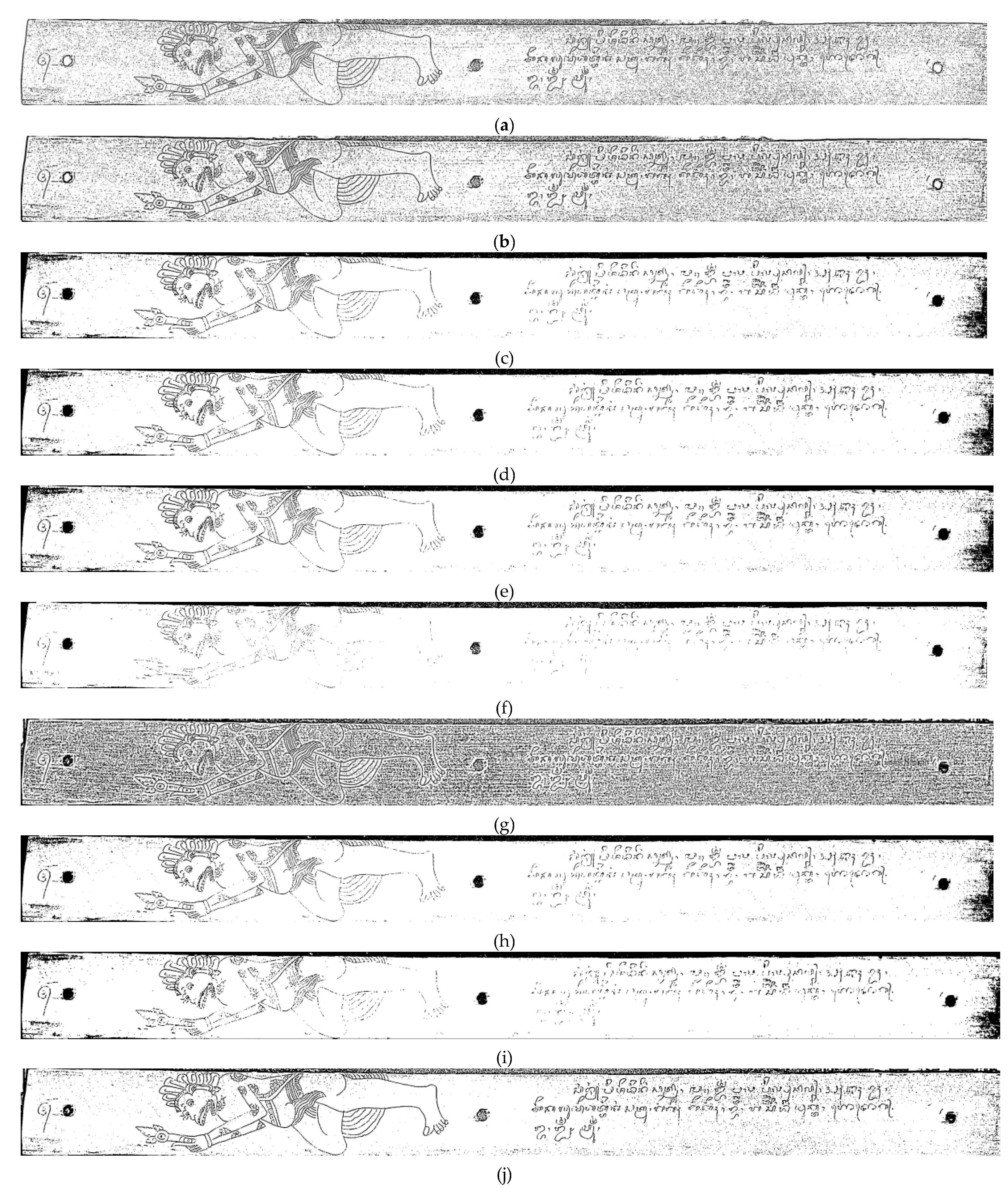

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preprocessing

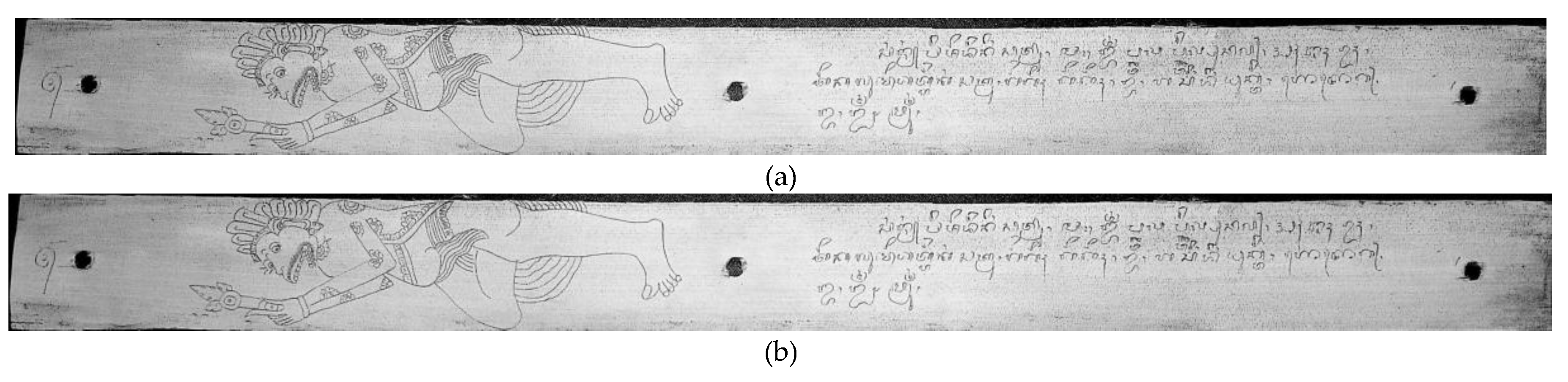

2.2. Thresholding Techniques

2.3. Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

2.3.1. Confusion Matrix-Based Metrics

2.3.2. Structure-Based Similarity Metrics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| MS-SSIM | Multi scale Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| FSIM | Feature Similarity Index Measure |

| ISODATA | Iterative Self-Organizing Data Analysis Technique |

| GMSD | Gradient Magnitude Similarity Deviation |

References

- Wilson, E.B.; Rice, J.M. Palm Leaf Manuscripts in South Asia [Post-doc and Student Scholarship]. Syracuse University; 2019.

- Khadijah, U.L.S.; Winoto, Y.; Shuhidan, S.M.; Anwar, R.K.; Lusiana, E. Community Participation in Preserving the History of Heritage Tourism Sites. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development. 2024 Jan 18;12(1):e2504. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, D.; Sankar, D. An Overview of Character Recognition from Palm Leaf Manuscripts. In: 2023 3rd International Conference on Smart Data Intelligence (ICSMDI). IEEE; 2023. p. 265–72. [CrossRef]

- Krithiga, R.; Varsini, S. ; Joshua. R.G.; Kumar, C.U.O. Ancient Character Recognition: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access. 2023;1–1. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, D.A.S.; Arsa, D.M.S.; Putri, G.A.A.; Setiawati, N.L.P.L.S. Ensembling Deep Convolutional Neural Neworks For Balinese Handwritten Character Recognition. ASEAN Engineering Journal. 2023 Aug 30;13(3):133–9. [CrossRef]

- Bannigidad, P.; Sajjan, S.P. Restoration of Ancient Kannada Handwritten Palm Leaf Manuscripts Using Image Enhancement Techniques. In 2023. p. 101–9. [CrossRef]

- Khafidlin, K. Ancient Manuscript Preservation of Museum Ranggawarsita Library Collection Semarang Central Java. Daluang: Journal of Library and Information Science. 2021 May 31;1(1):52. [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, S.U.; Maheswari, P.U.; Aakaash, G.R.S. An intelligent character segmentation system coupled with deep learning based recognition for the digitization of ancient Tamil palm leaf manuscripts. Herit Sci. 2024 Oct 1;12(1):342. [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Yu, C.; Han, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Revealing the Mechanism of Ink Flaking from Surfaces of Palm Leaves (Corypha umbraculifera). Langmuir. 2024 Mar 26;40(12):6375–83. [CrossRef]

- Yuadi, I.; Halim, Y.A.; Asyhari, A.T.; Nisa’, K.; Nazikhah, N.U.; Nihaya, U. Image Enhancement and Thresholding for Ancient Inscriptions in Trowulan Museum’s Collection Mojokerto, Indonesia. In: 2024 7th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE). IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, D.; Sankar, D. Enhancing Malayalam Palm Leaf Character Segmentation: An Improved Simplified Approach. SN Comput Sci. 2024 May 23;5(5):577. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, D.; Sankar, D. A Novel Complete Denoising Solution for Old Malayalam Palm Leaf Manuscripts. Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis. 2022 Mar 18;32(1):187–204. [CrossRef]

- Yuadi, I.; Nihaya, U.; Pratiwi, F.D. Digital Forensics to Identify Damaged Part of Palm Leaf Manuscript. In: 2023 6th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE). IEEE; 2023. p. 319–23. [CrossRef]

- Selvan, M.; Ramar, K. Development of optimized ensemble machine learning-based character segmentation framework for ancient Tamil palm leaf manuscripts. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2025 Apr;146:110235. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, E.; Burie, J.C.; Verbeek, F.J. Text line extraction strategy for palm leaf manuscripts. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2023 Oct;174:10–6. [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, F.; Suprapto, Y.K.; Yuniarno, E.M. Segmentation of Javanese Character in Ancient Manuscript using Connected Component Labeling. In: 2020 International Conference on Computer Engineering, Network, and Intelligent Multimedia (CENIM). IEEE; 2020. p. 412–7. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, Q.; Kou, R.; Huang, F.; Yang, B.; et al. Techniques and Challenges of Image Segmentation: A Review. Electronics (Basel). 2023 Mar 2;12(5):1199. [CrossRef]

- Pravesjit, S.; Seng, V. Segmentation of Background and Foreground for Ancient Lanna Archaic from Palm Leaf Manuscripts using Deep Learning. In: 2021 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunication Engineering. IEEE; 2021. p. 220–4. [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, J.N.; Saxena, I. Threshold Spaces: The Transitional Spaces Between Outside and Inside in Traditional Indian Dwellings. Heritage. 2024 Nov 27;7(12):6683–711. [CrossRef]

- Yuadi, I.; Yudistira, N.; Habiddin, H.; Nisa’, K. A Comparative Study of Image Processing Techniques for Javanese Ancient Manuscripts Enhancement. IEEE Access. 2025;13:36845–57. [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1979 Jan;9(1):62–6. [CrossRef]

- Sauvola, J.; Pietikäinen, M. Adaptive document image binarization. Pattern Recognition. 2000 Feb;33(2):225–36. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Lee, C.K. Minimum cross entropy thresholding. Pattern Recognition. 1993 Apr;26(4):617–25. [CrossRef]

- Kesiman, M.W.A.; Burie, J.C.; Ogier, J.M.; Grangé, P. Knowledge Representation and Phonological Rules for the Automatic Transliteration of Balinese Script on Palm Leaf Manuscript. Computación y Sistemas. 2018 Jan 1;21(4). [CrossRef]

- Niblack, W. An Introduction to Digital Image Processing. Birkeroed: Strandberg Publishing Company; 1985.

- Torres-Monsalve, A.F.; Velasco-Medina, J. Hardware implementation of ISODATA and Otsu thresholding algorithms. In: 2016 XXI Symposium on Signal Processing, Images and Artificial Vision (STSIVA). IEEE; 2016. p. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Jailingeswari, I.; Gopinathan, S. Tamil handwritten palm leaf manuscript dataset (THPLMD). Data Brief. 2024 Apr;53:110100. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, D.; Sankar, D. A Novel approach for Denoising palm leaf manuscripts using Image Gradient approximations. In: 2019 3rd International conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA). IEEE; 2019. p. 506–11. [CrossRef]

- Fred, A.L.; Kumar, S.N.; Haridhas, A.K.; Daniel, A.V.; Abisha, W. Evaluation of local thresholding techniques in Palm-leaf Manuscript images. International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering. 2018 Apr 30;6(4):124–31. [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, N.; Indu, S. Application of Gaussian as Edge Detector for Image Enhancement of Ancient Manuscripts. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2017 Aug;225:012149. [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, J.; Maheswari, P.U. Comparative Study: Enhancing Legibility of Ancient Indian Script Images from Diverse Stone Background Structures Using 34 Different Pre-Processing Methods. Herit Sci. 2024 Feb 20;12(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Siountri, K.; Anagnostopoulos, C.N. The Classification of Cultural Heritage Buildings in Athens Using Deep Learning Techniques. Heritage. 2023 Apr 13;6(4):3673–705. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Liao, H.; Nong, G.; Wei, W. MFFP-Net: Building Segmentation in Remote Sensing Images via Multi-Scale Feature Fusion and Foreground Perception Enhancement. Remote Sens (Basel). 2025 May 28;17(11):1875. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, H.; Ishibashi, R.; Meng, L. Deteriorated Characters Restoration for Early Japanese Books Using Enhanced CycleGAN. Heritage. 2023 May 14;6(5):4345–61. [CrossRef]

- Lontar Terumbalan. National Library of Indonesia. https://khastara.perpusnas.go.id/koleksi-digital/detail/?catId=1290335.

- Yuadi, I.; Koesbardiati, T.; Wicaksono, R.P.R.W.; Gurushankar, K.; Nisa’, K. Digital Forensic Analysis of Tooth Wear in Prehistoric and Modern Humans. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. 2025 Apr 3;53(1):145–54. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, Z. Crack Defect Detection Processing Algorithm and Method of MEMS Devices Based on Image Processing Technology. IEEE Access. 2023;11:126323–34. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.; Naik, B.; Pelusi, D. ; Das, AK, editors. Handbook of Computational Intelligence in Biomedical Engineering and Healthcare. Elsevier; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Islam, S. Methods in detection of median filtering in digital images: a survey. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023 Nov 26;82(28):43945–65. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, RC.; Woods, RE. Digital Image Processing. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Pearson Education; 2018.

- Justusson, B.I. Median Filtering: Statistical Properties. In: Two-Dimensional Digital Signal Prcessing II. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2006. p. 161–96. [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.R. The Role of Thresholding. Computer Vision. 2018;93–118. [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, K.; Siddiqi, I.; Faure, C.; Vincent, N. Comparison of Niblack Inspired Binarization Methods for Ancient Documents. In: Berkner K, Likforman-Sulem L, editors. 2009. p. 72470U. [CrossRef]

- Farid, S.; Ahmed, F. Application of Niblack’s method on images. In: 2009 International Conference on Emerging Technologies. IEEE; 2009. p. 280–6. [CrossRef]

- Trier, O.D.; Jain, A.K. Goal-directed evaluation of binarization methods. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1995;17(12):1191–201. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Tam, P.K.S. An iterative algorithm for minimum cross entropy thresholding. Pattern Recognit Lett. 1998 Jun;19(8):771–6. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Cadenbach, A.H.; Salimi, E. A Kullback–Leibler View of Maximum Entropy and Maximum Log-Probability Methods. Entropy. 2017 May 19;19(5):232. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lv, J. Minimum Cross-Entropy Transform of Risk Analysis. In: 2011 International Conference on Management and Service Science. IEEE; 2011. p. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Magid, A.; Rotman, S.R.; Weiss, A.M. Comments on Picture thresholding using an iterative selection method. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1990 Sep;20(5):1238–9. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, F.; Li, R. Improved K-means Algorithm Based on Threshold Value Radius. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2020 Jan 1;428(1):012001. [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Dutta, S.; Dey, N.; Dey, G.; Chakraborty, S.; Ray, R. Adaptive thresholding: A comparative study. In: 2014 International Conference on Control, Instrumentation, Communication and Computational Technologies (ICCICCT). IEEE; 2014. p. 1182–6. [CrossRef]

- Yazid, H.; Arof, H. Gradient based adaptive thresholding. J Vis Commun Image Represent. 2013 Oct;24(7):926–36. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.A.; Haroon, F. Adaptive Gaussian and Double Thresholding for Contour Detection and Character Recognition of Two-Dimensional Area Using Computer Vision. In: INTERACT 2023. Basel Switzerland: MDPI; 2023. p. 23. [CrossRef]

- Erwin.; Noorfizir, A.; Rachmatullah, M.N.; Saparudin.; Sulong G. Hybrid Multilevel Thresholding-Otsu and Morphology Operation for Retinal Blood Vessel Segmentation. Engineering Letters. 2020;28(1):180–91.

- Seidenthal, K.; Panjvani, K.; Chandnani, R.; Kochian, L.; Eramian, M. Iterative image segmentation of plant roots for high-throughput phenotyping. Sci Rep. 2022 Oct 4;12(1):16563. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2004 Apr;13(4):600–12. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, H.; Kuruoglu, E.E.; Zhou, W. Robust structural similarity index measure for images with non-Gaussian distortions. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2022 Nov;163:10–6. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, K.; Zhu, Z. Otsu Multi-Threshold Image Segmentation Based on Adaptive Double-Mutation Differential Evolution. Biomimetics. 2023 Sep 8;8(5):418. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Mou, X.; Zhang, D. FSIM: A Feature Similarity Index for Image Quality Assessment. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2011 Aug;20(8):2378–86. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Simoncelli, E.P.; Bovik, A.C. Multi-scale structural similarity for image quality assessment. In: Conference Record of the Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers. Pacific Grove, CA, United States: IEEE; 2003. p. 1398–402.

- Xue, W.; Zhang, L.; Mou, X. ; Bovik. A.C. Gradient Magnitude Similarity Deviation: A Highly Efficient Perceptual Image Quality Index. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2014 Feb;23(2):684–95. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.H.; Salehi, M.E. A Fast Fault-Tolerant Architecture for Sauvola Local Image Thresholding Algorithm Using Stochastic Computing. IEEE Trans Very Large Scale Integr VLSI Syst. 2016 Feb;24(2):808–12. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Cai, Z. Historical Document Image Binarization Based on Edge Contrast Information. In 2020. p. 614–28. [CrossRef]

- Saddami, K.; Afrah, P.; Mutiawani, V.; Arnia, F. A New Adaptive Thresholding Technique for Binarizing Ancient Document. In: 2018 Indonesian Association for Pattern Recognition International Conference (INAPR). IEEE; 2018. p. 57–61. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Liu, M. Research on Document Image Binarization: A Survey. In: 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT). IEEE; 2024. p. 457–62. [CrossRef]

- Munivel, M. Enigo, VSF. Performance of Binarization Algorithms on Tamizhi Inscription Images: An Analysis. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing. 2024 May 31;23(5):1–29. [CrossRef]

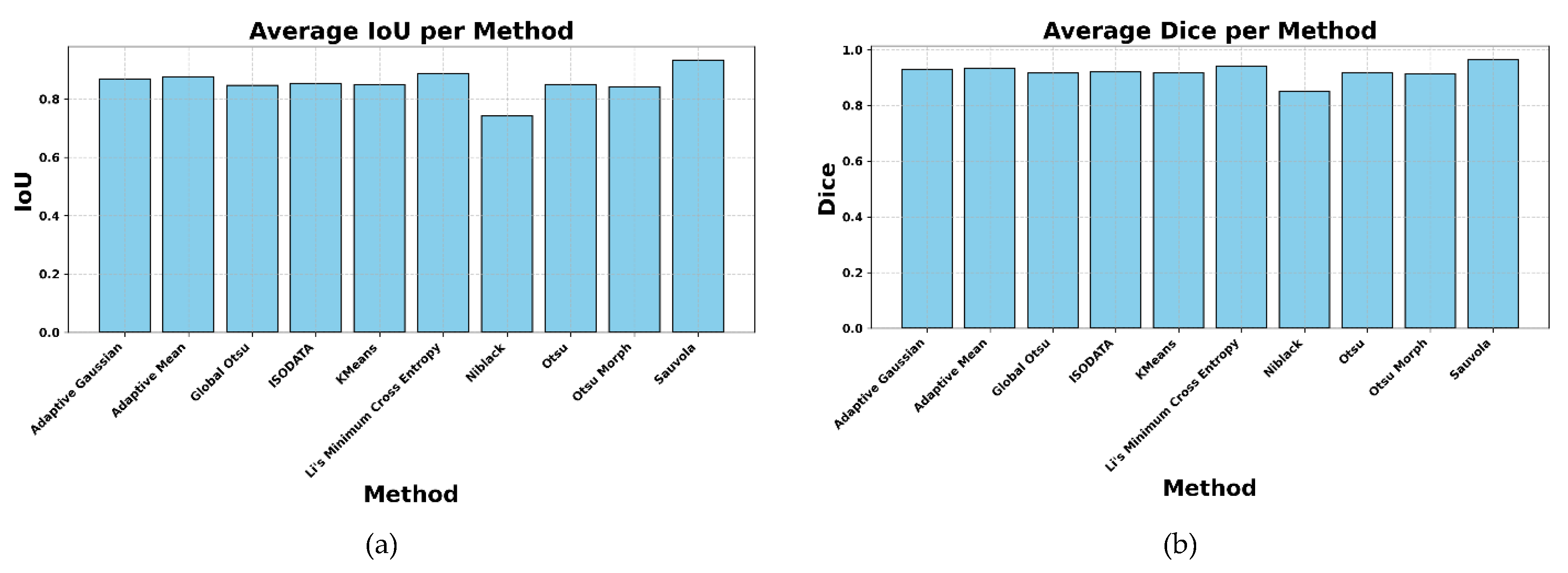

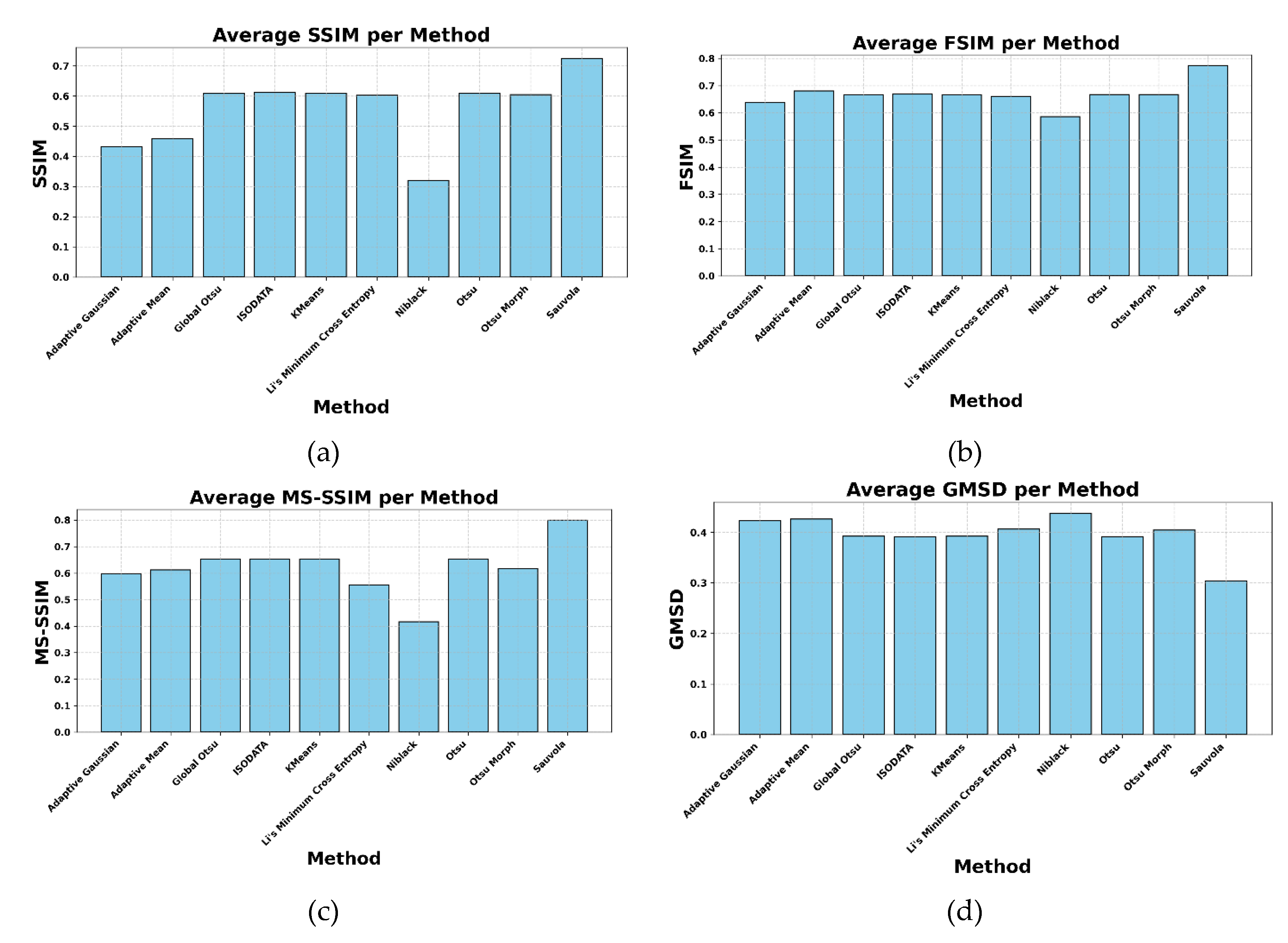

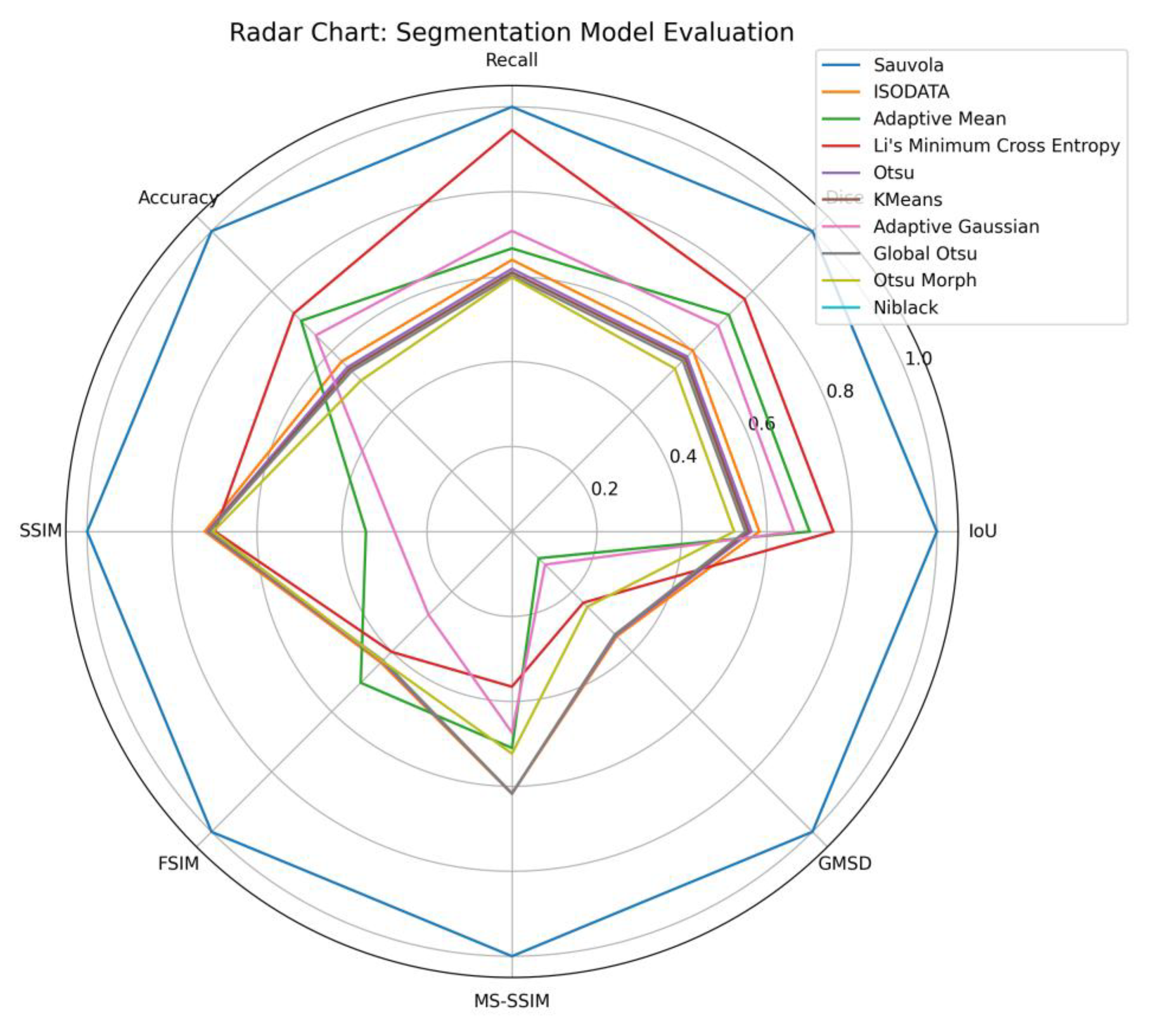

| Method | IoU | Dice | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Gaussian | 0.869 | 0.930 | 0.908 | 0.884 |

| Adaptive Mean | 0.876 | 0.934 | 0.899 | 0.892 |

| Global Otsu | 0.847 | 0.916 | 0.885 | 0.864 |

| ISODATA | 0.853 | 0.920 | 0.893 | 0.870 |

| Kmeans | 0.848 | 0.917 | 0.887 | 0.865 |

| Li’s Minimum Cross Entropy | 0.887 | 0.940 | 0.959 | 0.896 |

| Niblack | 0.741 | 0.851 | 0.755 | 0.775 |

| Otsu | 0.850 | 0.918 | 0.889 | 0.866 |

| Otsu Morph | 0.842 | 0.913 | 0.884 | 0.859 |

| Sauvola | 0.934 | 0.966 | 0.971 | 0.942 |

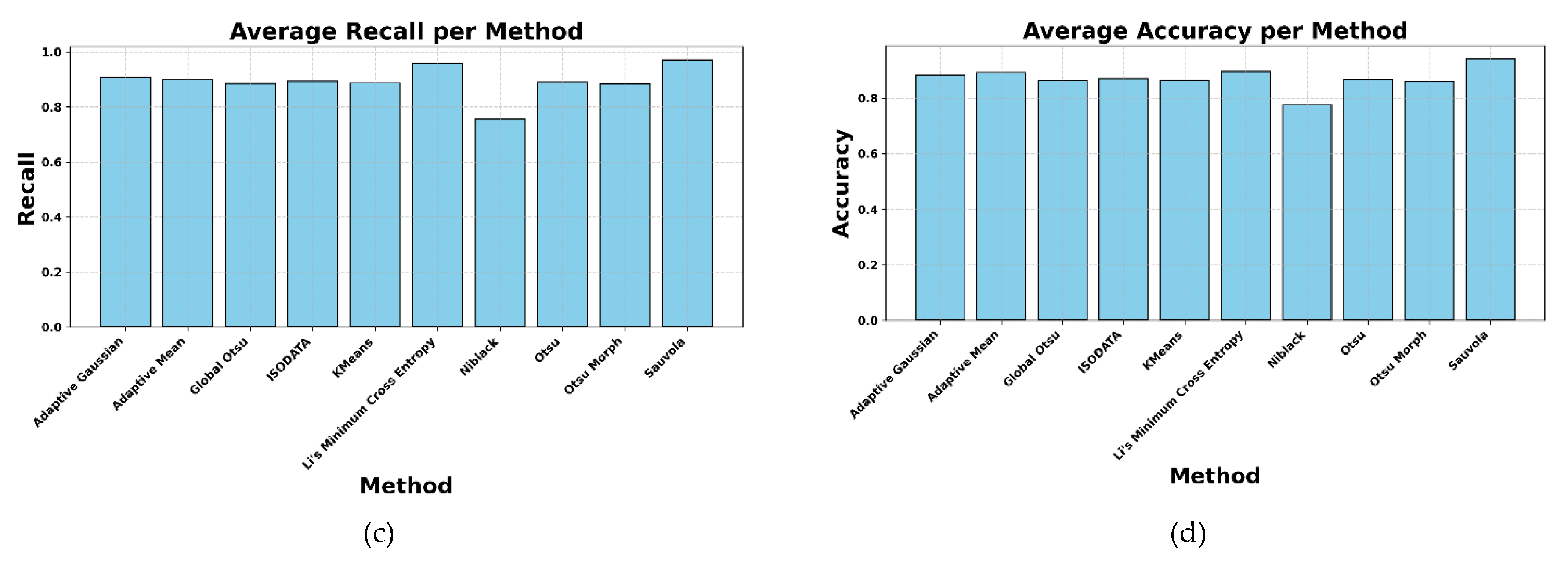

| Method | SSIM | FSIM | MS-SSIM | GMSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Gaussian | 0.432 | 0.638 | 0.598 | 0.423 |

| Adaptive Mean | 0.459 | 0.681 | 0.612 | 0.426 |

| Global Otsu | 0.608 | 0.667 | 0.653 | 0.392 |

| ISODATA | 0.613 | 0.668 | 0.653 | 0.391 |

| KMeans | 0.609 | 0.667 | 0.653 | 0.392 |

| Li’s Minimum Cross Entropy | 0.603 | 0.661 | 0.557 | 0.406 |

| Niblack | 0.320 | 0.586 | 0.416 | 0.438 |

| Otsu | 0.610 | 0.667 | 0.653 | 0.392 |

| Otsu Morph | 0.605 | 0.667 | 0.617 | 0.404 |

| Sauvola | 0.725 | 0.774 | 0.800 | 0.304 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).