1. Introduction

For the first time, in a few hundred years, five megatrends are concurrently impacting the world: climate change, demographic shifts, technological disruption, fracturing world, and social instability. As moving into the future, organizations must strategically consider each area. In fact, demographic shifts and urbanization have had a big contribution to the excessive use of primary energy and the massive emissions of dioxide of carbon (CO

2) which have led to energy depletion, global warming, and climate change. Nowadays, investigations are developing various energy production, energy storage, and renewable energy technologies worldwide [

1].

Energy production, which consists mainly of burning fossil fuels, accounts for around three-quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions. Besides, energy production is not only the largest driver of climate change but also burning fossil fuels as well as biomass has come at a large cost to human health: at least five million deaths are attributed to air pollution each year [

2]. In addition, projections indicate that CO

2 emissions could increase by more than 50% by 2050 [

3]. Among the most energy consumer sectors is the building sector. In fact, it accounted for 30% and 26 % of the world's final energy consumption and global carbon emissions, respectively, making it one of the largest energy-consuming sectors [

4,

5,

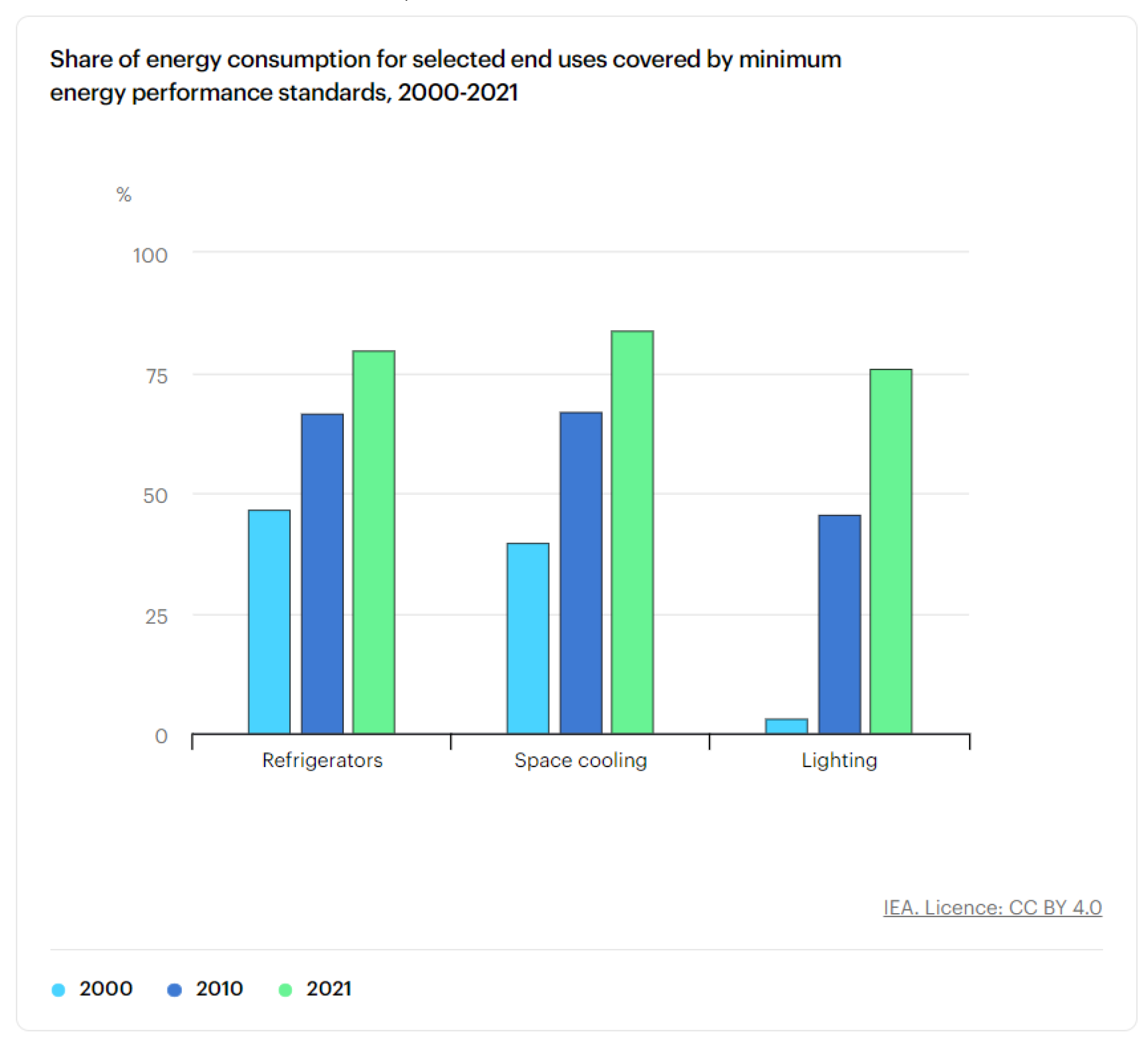

6]. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 1 [

5], systems essentially heating, ventilation, and air conditioning in buildings (HVAC) as well as lighting accounted for up to 60 % of the total building’s energy consumption and this percentage is on a rise through the years [

1,

7,

8]. In particular, the energy demand for cooling is projected to increase in 2040 and 2060, driven by growing need for indoor comfort and climate change [

9].

According to the 2022 Outlook of the International Energy Agency (IEA) [

10], it was predicted that worldwide building’s energy consumption will increment by an average of 1.5 % per year between 2012 and 2040 [

11]. This trend is expected to accelerate over 2025-2027 due to growing energy demand from data centers and digital networks in the building sector [

4]. Besides, one-third of global energy and process-related CO

2 emissions were generated from direct and indirect emissions of the building sector causing a large carbon footprint. 10 Gt of both source of emissions were from building operations, registering an increase of 2% compared to 2019 and 5% compared to 2020, and distributed as follows; 8% are a result of the use of fossil fuels in buildings, 19% are from the generation of electricity, heat and cool for buildings and 6% are from the manufacture of cement, steel, and aluminium for the construction operation which has risen by 34% between 2010 and 2021 [

5,

12].

Thus, the transition toward more sustainable, cleaner efficient and renewable energy technologies in the building sector remains a necessity through seeking potential solutions to get on track with Net Zero Emissions in Building (ZEB) by 2050. Therefore, the next few years will be crucial considering implementing the necessary measures both in new and existing buildings to reach the zero-carbon-ready target as soon as 2030 [

5,

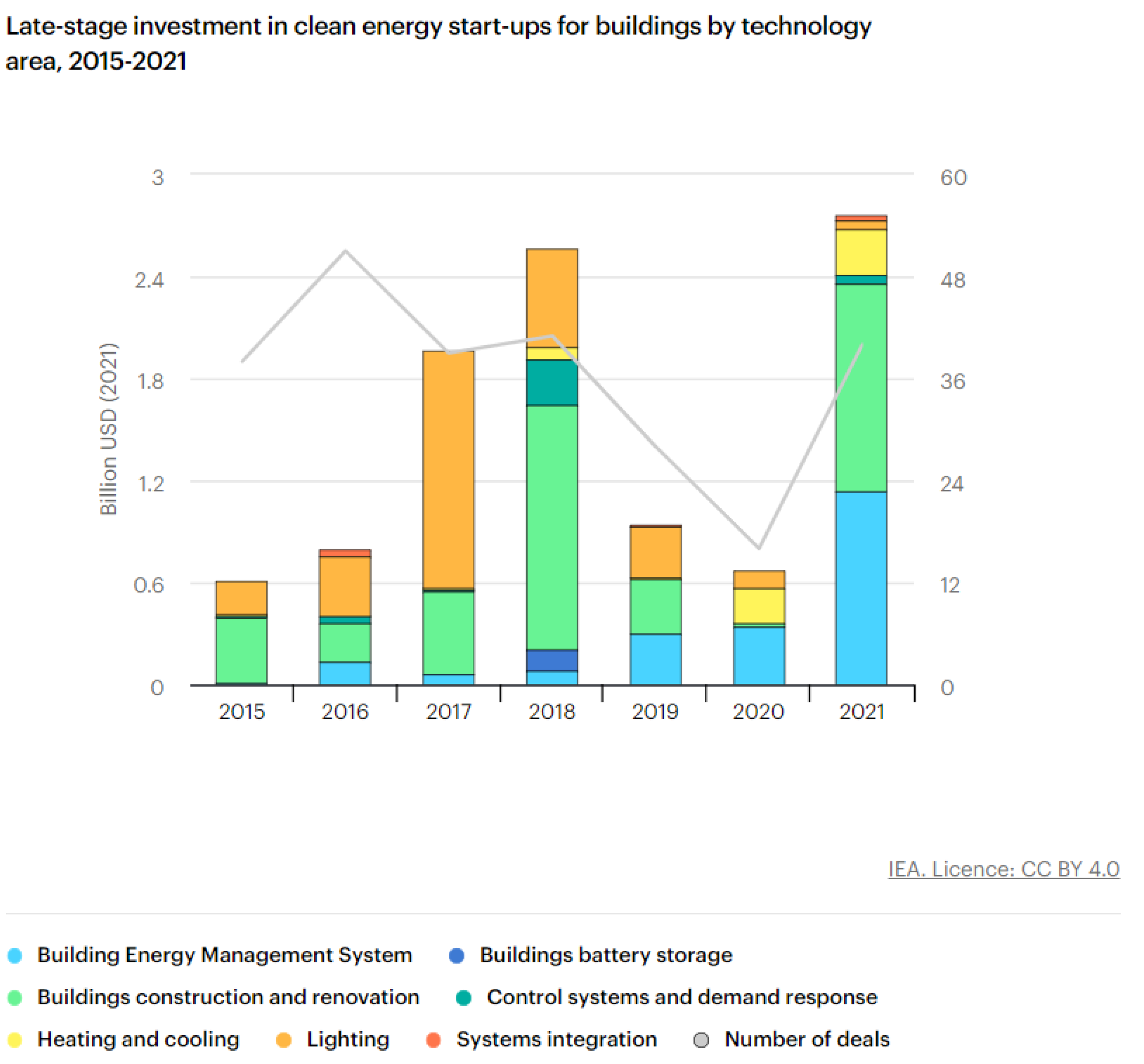

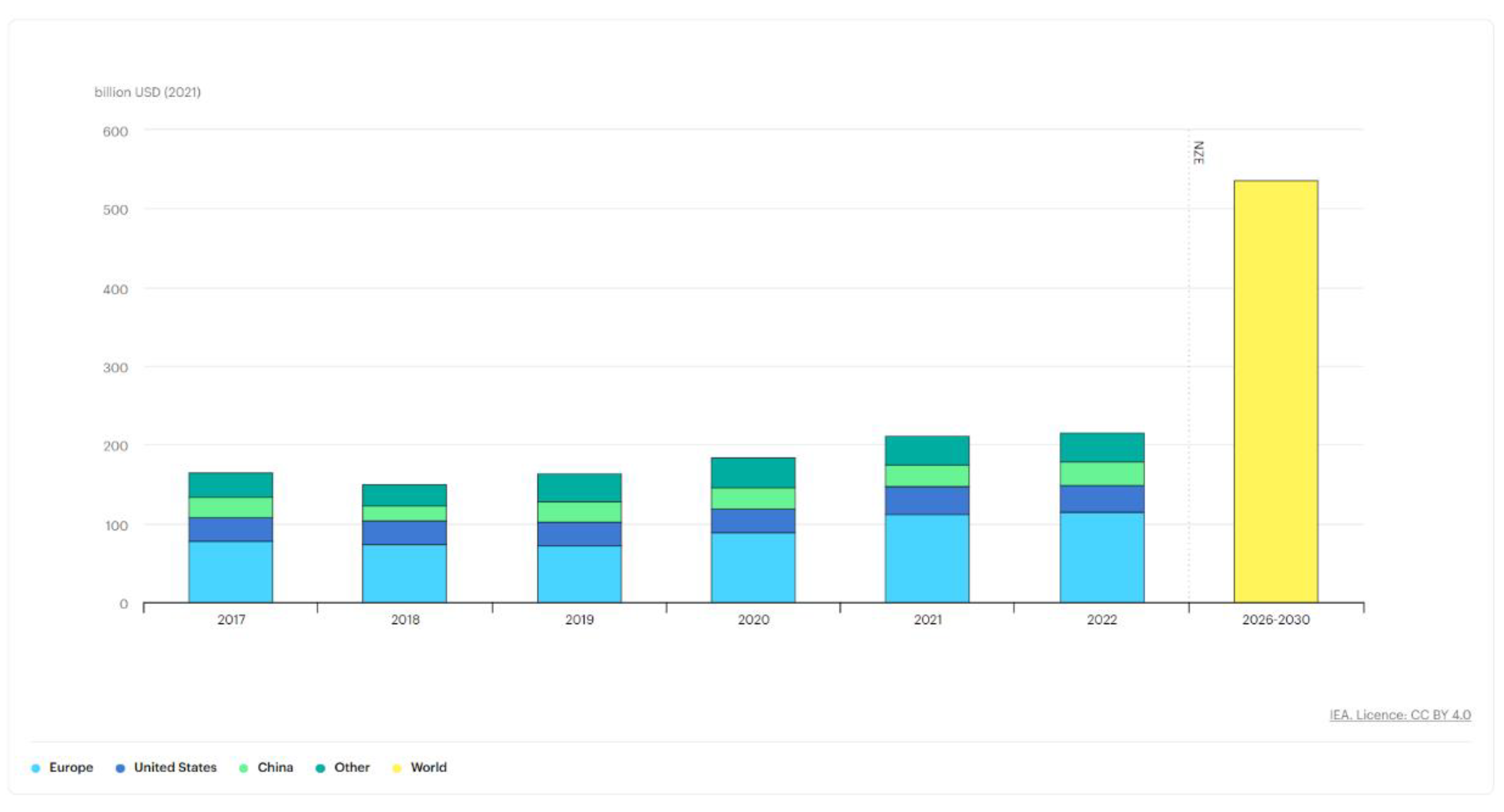

7]. As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, this alarming situation made many countries act and start to invest on the clean green sector (15% increase in 2021). As a result, over 1828 related policies and strategies, and scenarios worldwide have been suggested to reach the desired target by 2030 [

13] and meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. In this context, the UK adopted the “Clean Growth Strategy” which is expected to lead to an improvement by 25% in the energy efficiency of businesses and industries, China adopted the “13th Five-Year Plan” which will produce a drop of 15% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of used energy. EU states, as well, adopted the “2030 Energy Strategy” which will induce a 32.5% improvement in the building energy efficiency [

14,

15,

16].

2. Thermal Energy Storage Technology (TES)

Various investigations on renewable energy-based systems have been elaborated and tested to reduce heat/cool peak load each in their field of expertise. Among, Hmida et al. [

17] investigated the use of Photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) system to produce heat, cool and electricity for buildings. The authors concluded that the PVT (Photovoltaic Thermal) double pass collector can reach an annual electrical power of up to 194.58 kWh/m2 and a thermal power of 811.37 kWh/m2. In comparison, a conventional PV system produces about 194,76 kWh/m2 per year in electricity alone. This significant additional thermal contribution makes the PVT system very advantageous for heating and cooling applications in buildings. Yuan et al. [

18] suggested the use of biomass to produce heat during the winter season. They found that the energy consumption is reduced significantly throughout the heating season. Chen et al. [

19] recommended the use of wind turbines considering that their system has produced 1960 kW, 336.1 kW, 183.3 kW of power, heating and cooling, respectively. Others, like Ruan et al. [

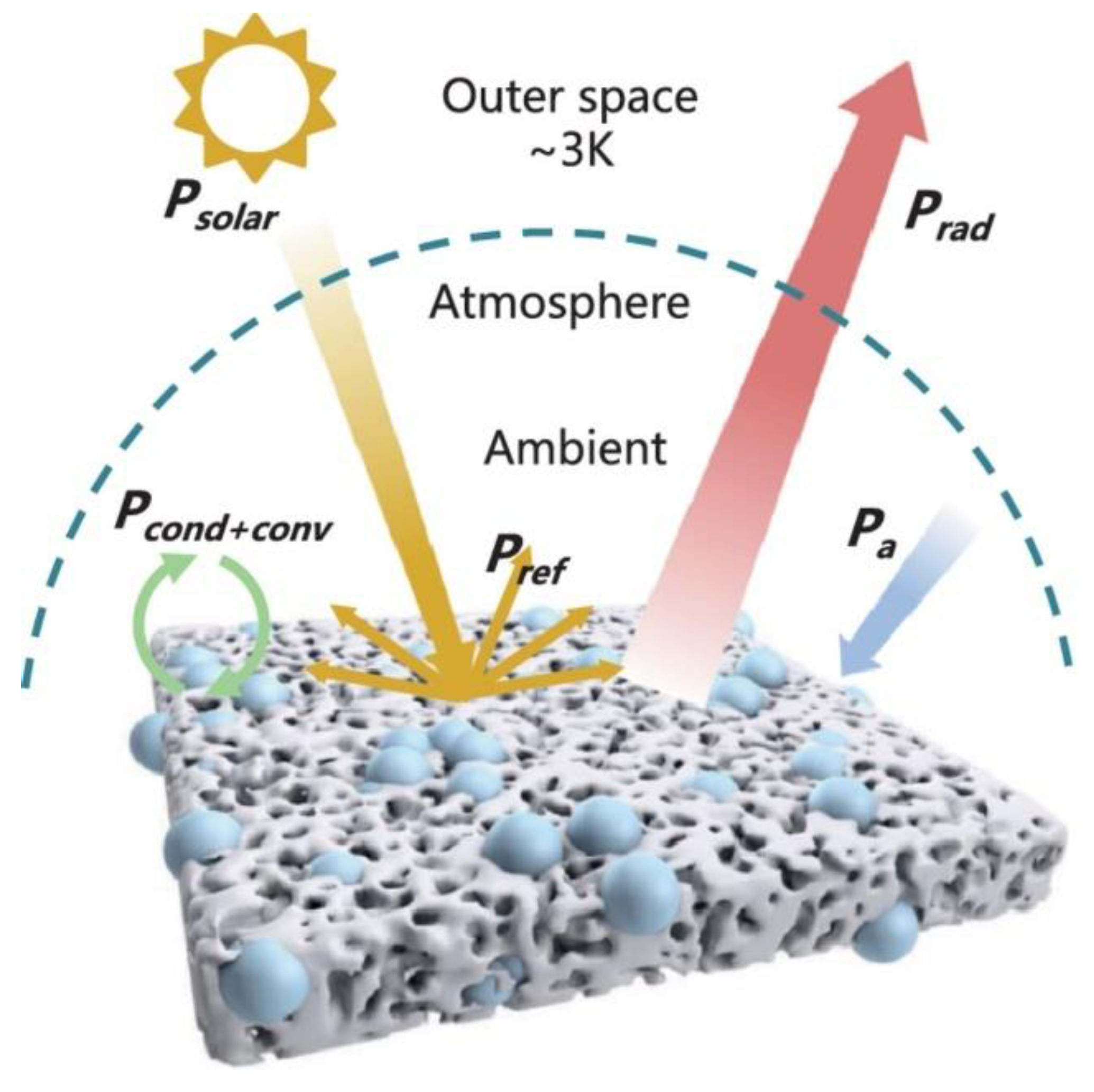

20] and Huang et al. [

21] developed a white reflective paint, that reflects 98% of the sunlight which will enable the building to use up to 40 % less air-conditioning during the summer season (

Figure 4).

Yet, for commercial applications, the cost has always been an issue. Thus, researchers have chosen new ways to achieve higher comfort levels and efficiency through the application of advanced techniques, such as active [

22] and passive measures [

16,

25,

26]. Passive systems such as thermal mass integration in buildings, rely on natural heat storage and release without external energy input, while active systems including air conditioning and evaporative cooling require mechanical or electrical assistance to enhance heat transfer.

Among the most tested passive technologies to reduce the peak of heating/cooling loads and to store energy is the integration of the solar thermal energy storage technology (TES) [

7,

27,

28]. Incorporating TES technologies in buildings reduces peak demand by 20-40%, lowers energy usage by 14%, cuts energy cost by 10-20%, and decrease emission by 5% [

27] .

Three types of TES technologies have been widely investigated, they can be grouped into sensible heat storage, latent heat storage as well as thermochemical heat storage, as detailed in

Table 1. Sensible and latent heat storage are the most used technologies in building envelopes because of their safety characteristics and ease of use [

28]. Furthermore, for the same storage volume, latent heat storage systems (LHS) offer a higher energy storage density than sensitive heat storage systems (SHS) because a large amount of energy is absorbed or released during the phase change at constant temperature. Thus, LHS can improve system efficiency while maintaining a stable target temperature [

29].

Researchers have paid attention to Phase Change Materials (PCM) based on latent heat energy storage as a solution to overcome the energy crisis problems, and environmental pollution and to ensure human thermal comfort. PCMs are utilized to effectively store energy and manage temperature variation, maintaining them in a specific range. This capability allows for enhanced thermal regulation and improved energy efficiency in various applications.

3. Operational Processes of Phase Change Materials (PCMs)

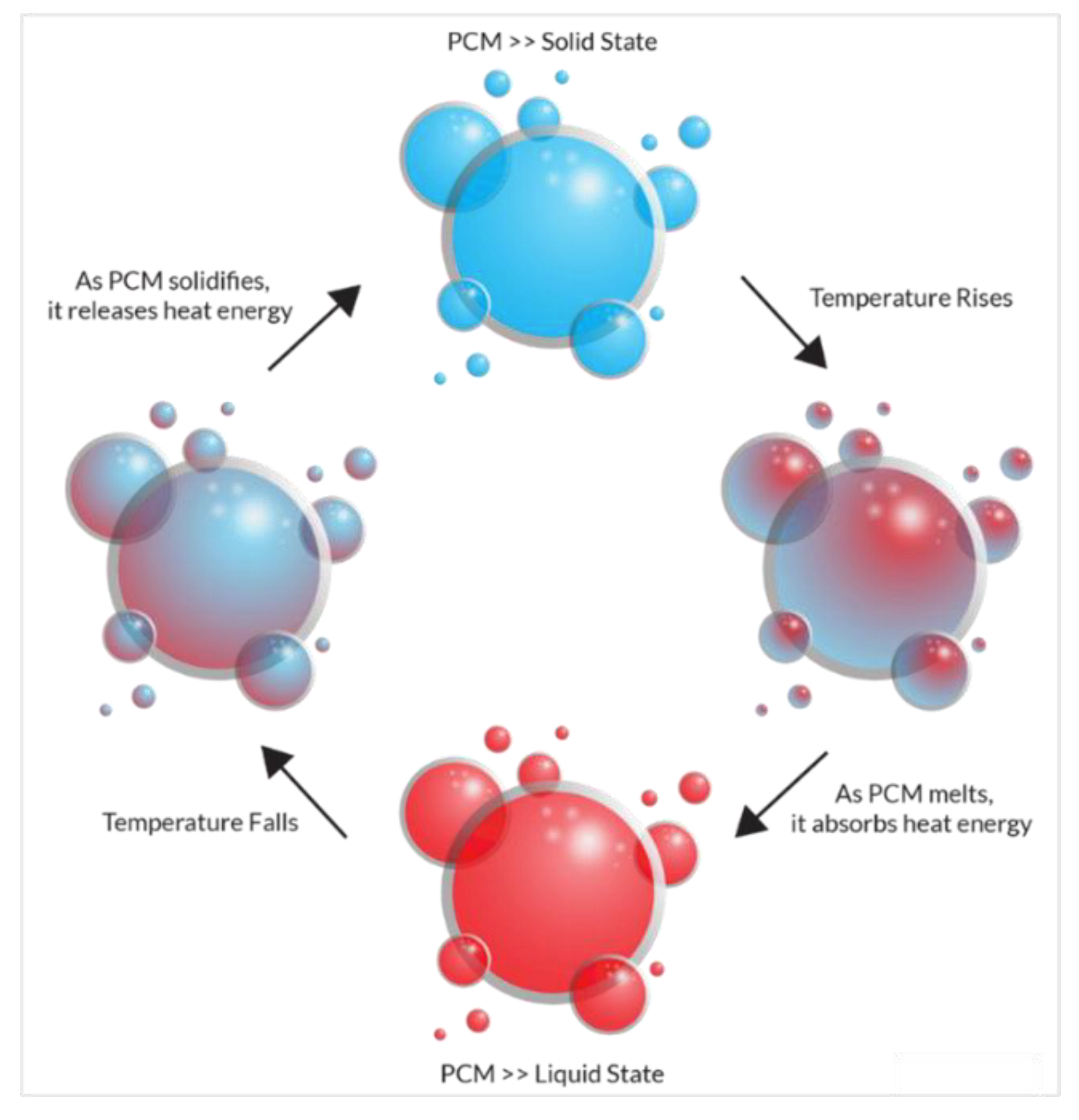

The latent TES system (LTES) with phase change materials (PCM) stores and releases thermal energy by phase transition which can be in the form of Solid-Liquid (S-L), Liquid–Gas (L-G) or Solid–Solid (S-S) transformation during a charge and discharge cycles [34-36].

During the charging cycle, PCM absorbs heat energy and changes its phase from a solid state to a liquid state, the reaction being endothermic. When energy is needed and released, a restoration of the solid phase is elaborated which is the discharging process (

Figure 5), the reaction being exothermic. Due to the slighter change in volume, the phase change material S-L and S-S are the most favored [

29,

35].

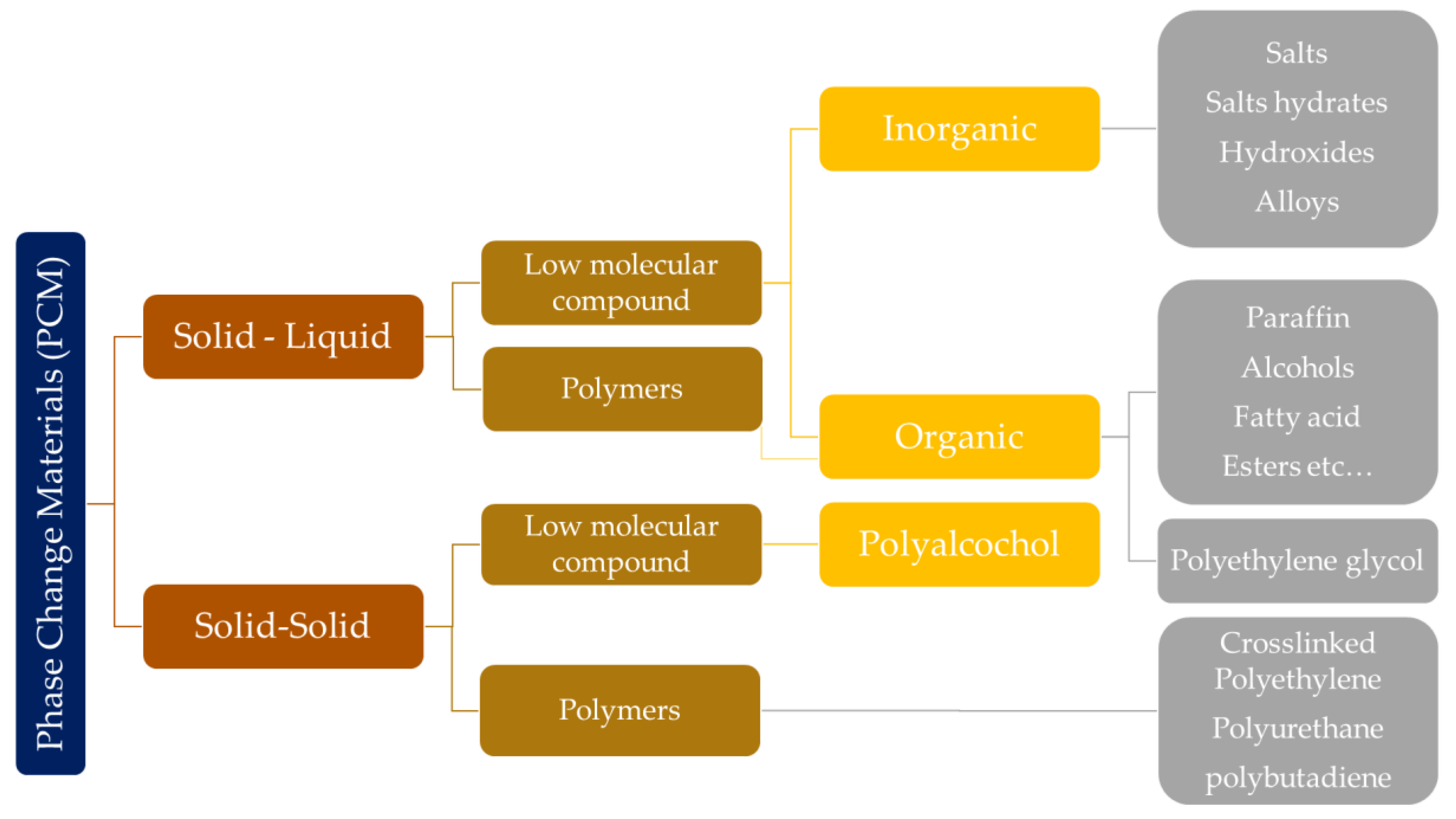

PCMs are classified based on their chemical composition as well as their temperature range, they are arranged into organic, inorganic, and eutectic materials.

Figure 6 provides the list of PCMs that are available in organic and inorganic forms [

35].

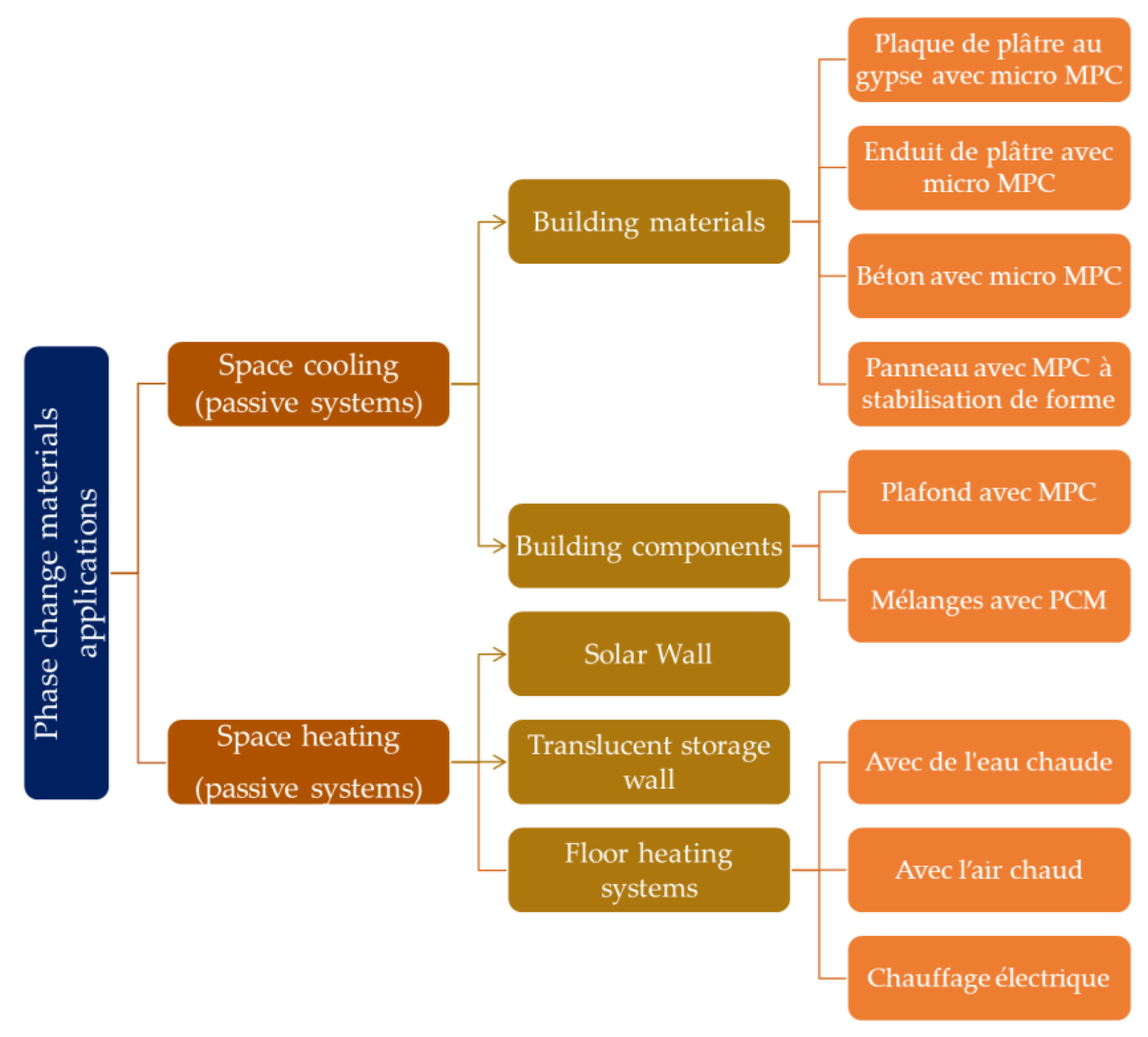

3.1. Integration of Phase Change Materials

Although, as depicted in

Figure 7, PCMs can be integrated into different parts of the buildings depending on the application. This includes PCM impregnated floor, roofing, wallboard bricks, ceiling, gypsum, window/façade, solar collectors, etc. [

39,

40,

41]. Meanwhile, Li et al. [

16] established a detailed illustration showcasing all possible PCM incorporation in a building (

Figure 8).

3.2. Fundamental properties of Phase Change Materials

Selecting the optimal PCM for a particular building application is indeed a challenging mission as each material has unique thermal properties that may or not suit various structure elements: roof, walls, windows, etc.

Table 2 highlights the advantages and the weaknesses of each type of PCM used for building applications [

31]. Organic PCM appears to be very promising due to their favorable melting temperature range and stability. Yet, it’s clear that enhancements are still needed especially in area like thermal conductivity and cost-effectiveness. One should consider the use of nanoparticles to improve the thermal conductivity and biobased PCM as a path to reach net-zero CO

2 emission particularly exciting, as these solutions hold potential for making phase change materials technology both efficient and sustainable. That said, balancing performance with affordability and environment impact will remain crucial as we refine these materials for widespread building applications.

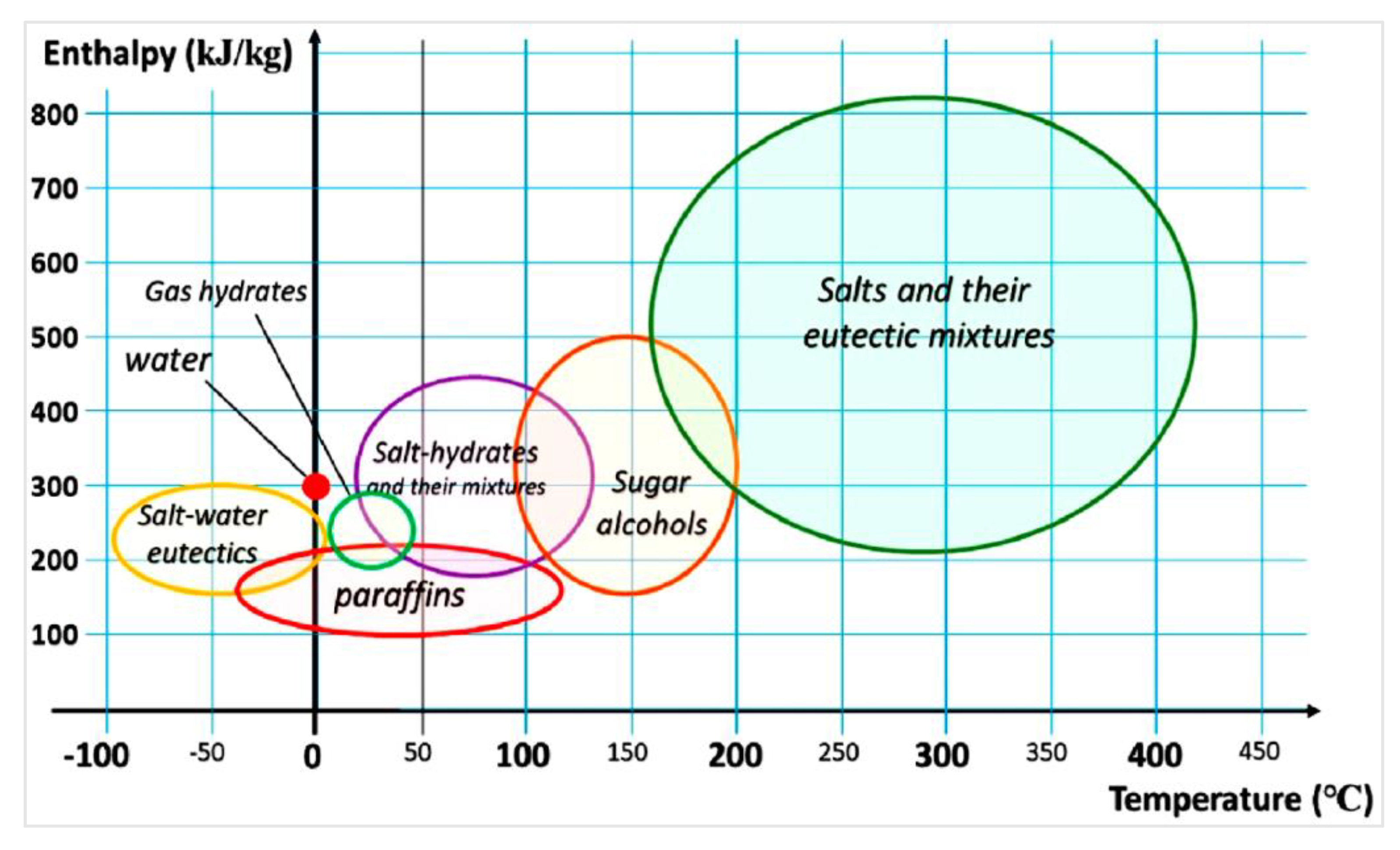

The appropriated PCM depends highly on the thermo-physical properties and the operating temperature range, in addition to the other desired characteristics. As depicted in

Figure 9, each form of PCM has a range of working temperatures making them more suitable for specific applications than others [

35].

Before any application, a thermo-physical test should be elaborated to ensure the suitability of the chosen PCM in the building under study. Different technologies can be used but the most widely adopted method is the Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC). It can provide the PCM’s melting and solidification temperatures, the specific heat, the enthalpies, and the heat storage capacity.

Table 3 yields the thermal properties of PCMs commonly used in building applications [

35]. Meanwhile,

Table 4 depicts the most used Paraffin and fatty acids for cooling and heating purposes. It can be resumed that for cooling applications in buildings, integrated PCMs should have a melting temperature that varies between 19ºC and 28ºC, whereas it should be between 28ºC to 40ºC for heating applications [

28]. Furthermore, other conditions should be considered like weather conditions, especially for changeable climate locations, the building structure, the insulation degree, the ventilation degree, the inner recesses, the occupancy profile and people number, the direct solar radiation, the heating profile, etc. [

38,

43].

Based on the phase transition temperature, fatty acids are proven to be suitable as PCMs for different applications at both low and medium temperatures. Hence, for low phase transition temperatures, ranging between -20°C and 5°C, PCMs are particularly effective for commercial and domestic refrigeration applications. In the range between 5°C and 40°C, PCMs can be used for both passive and active cooling and heating applications [

43]. However, while fatty acids demonstrate promising thermal properties, challenges such supercooling, phase segregation and low thermal conductivity may limit their long-term efficiency and performance.

3.3. Advanced Incorporation Techniques for Phase Change Materials

The incorporation of PCMs into building envelopes contributes to thermal comfort improvement and energy management by reducing heat peak and indoor temperature fluctuation owing to its storage density which is higher than that of standard walls by 5-10 times, leading to reduce electricity costs [

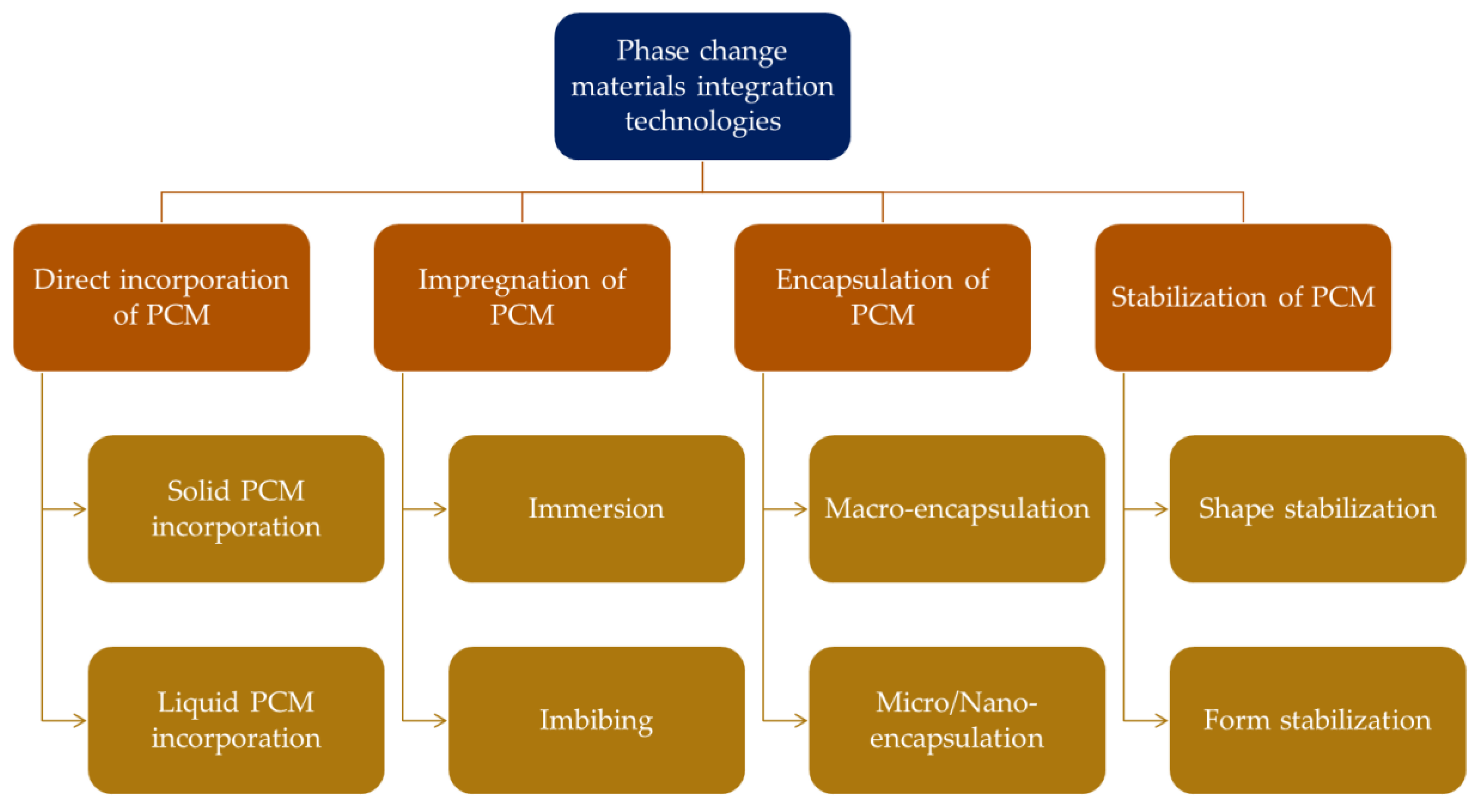

44]. Practically, as depicted in

Figure 10 four integration methodologies of PCMs into building envelope elements are available, they are as follows direct incorporation, impregnation, encapsulation, and stabilization [

33,

46,

47,

48].

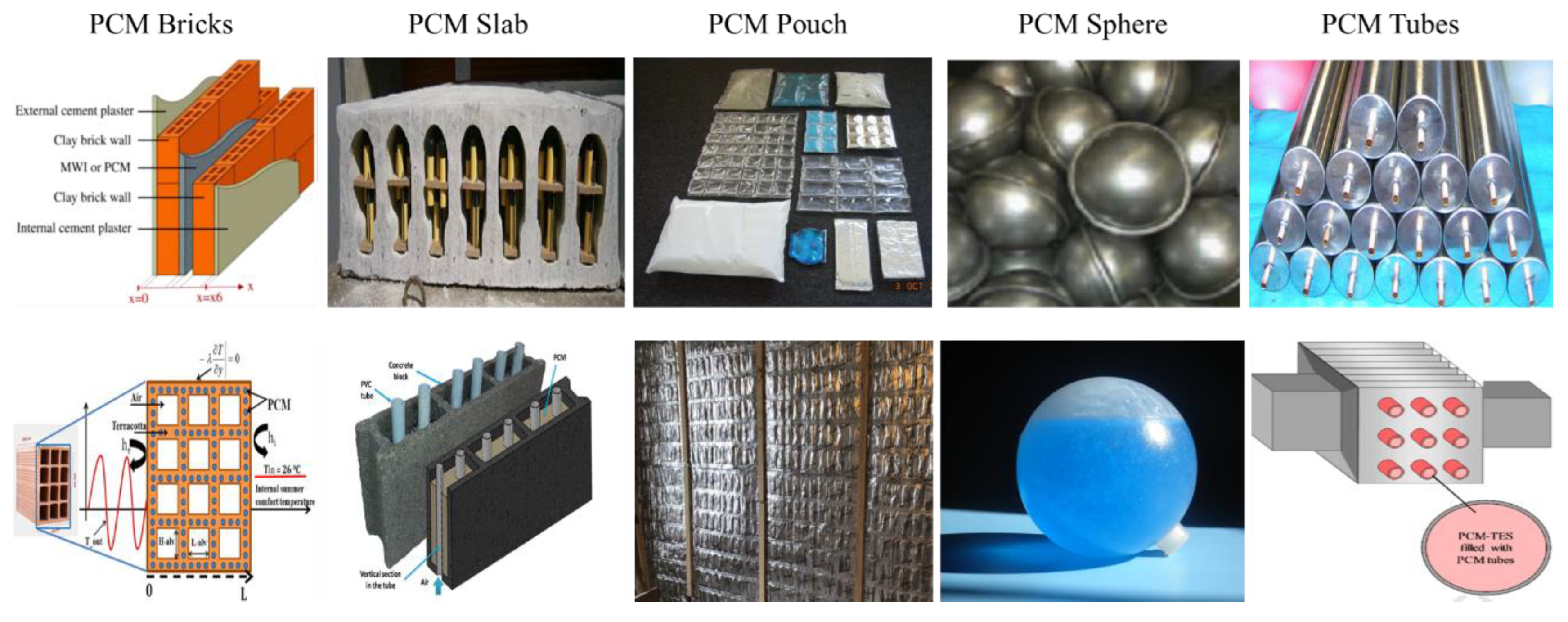

Figure 11 shows that PCMs can be integrated into porous construction materials like bricks or building blocks, or in metal or plastic containers through macro-encapsulation [

33,

47,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. In some applications, PCMs can be filled in brick cavities or added in one or more separate layers to the wall with the proper encapsulation. In this case, Mukram and Daniel [

31] investigated various method to incorporate PCMs into the building structure, including PCM as a separate layer, inserting them into brick cavities, and integrating them in the cement mortar for making concrete or for plastering. They concluded that, for optimal thermal performance, PCM layer should be placed closer to the heat source. However, while this approach contributes to enhance heat absorption it also raises concerns about structural integrity, potential leakage, long-term durability and compatibility with traditional building components. Thus, further studies that balance thermal regulation with material stability for more effective PCMs are needed.

Phase change materials can be incorporated into various applications using different chemical and physical methods to enhance their efficiency and adaptability. They can be integrated by microencapsulation and direct incorporation or shape stabilization [

33,

38,

56].

3.3.1. Direct Incorporation Methods of Phase Change Materials

Direct integration of PCMs into building materials (e.g., concrete, cement mortar, or gypsum) is considered the simplest, easiest, and cost-effective integration technique. Feldman et al. [

55] proved that adding directly 21-22% organic PCMs to gypsum sheets with some additives significantly enhanced energy storage up to 10 times compared to conventional gypsum wallboard. However, the main drawback of this technique is the risk of PCM leakage and degradation of mechanical properties of the building’s materials especially it was noticed that due to leakage the chances of fire were increased [

31,

44,

45,

56]. To address such drawbacks, Sun et al. [

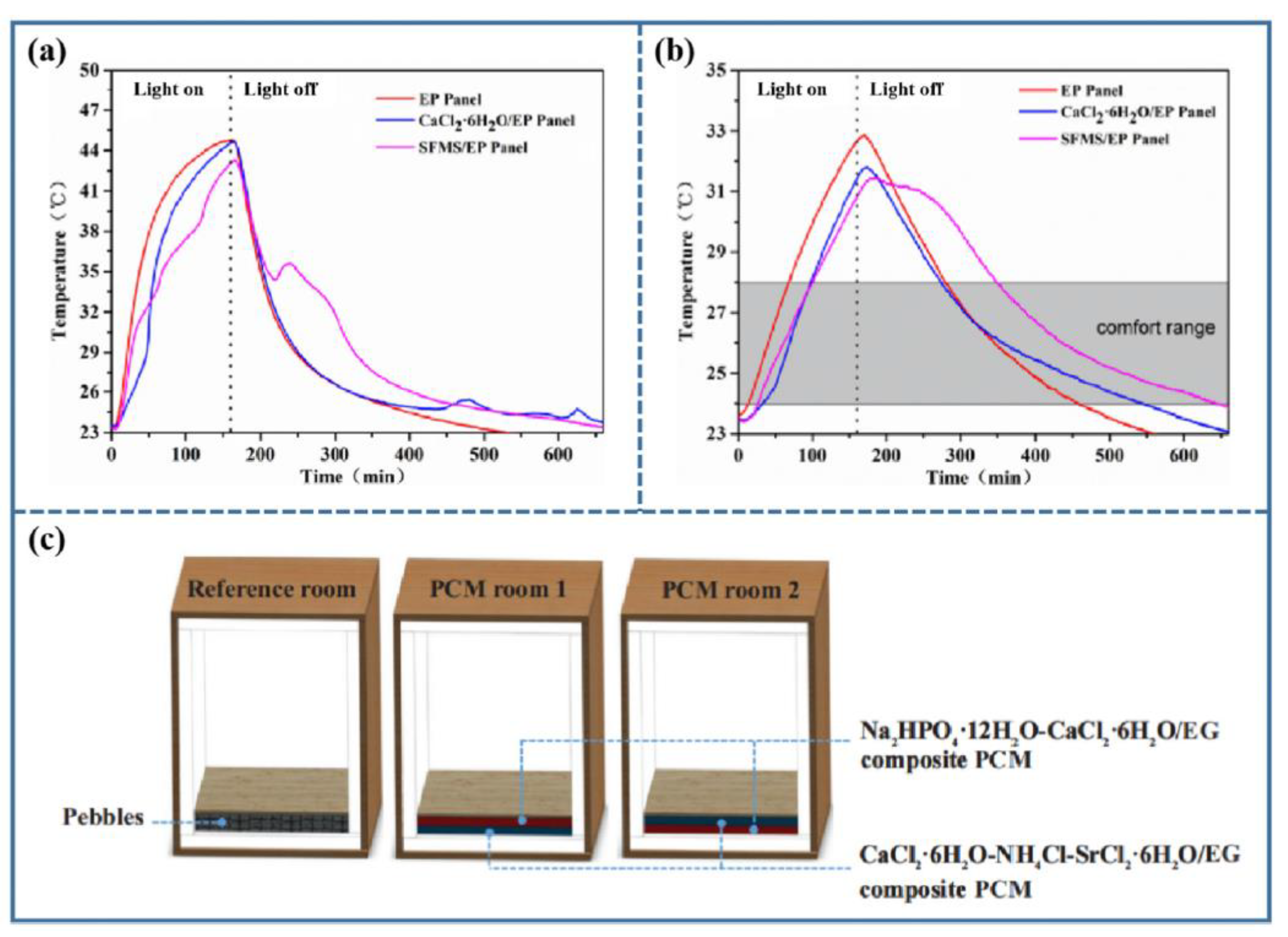

57] explored a double-layer radiant floor system integrating Na

2HPO

4⋅12H

2O and CaCl

2⋅6H

2O composite PCM as high and low-temperature layers, respectively (

Figure 12). They concluded that due to the incorporation of the PCM layer in the test room, the thermal comfort was significantly improved [

1].

Also, Antar et al. [

28] conducted a numerical simulation using ANSYS 2020 to examine the thermal behavior of a building wall under different weather conditions where multitype of PCMs and placements were tested. The highest thermal performance was obtained using RT-35HC at an optimal position of 1.5cm from both sides of the wall. Besides, they registered a 3.4ºC decrease in the indoor wall temperature and a 66 % reduction in the overall energy gain during the summer season.

Direct incorporation, despite its simplicity, compromise structural integrity while optimal placement requires precise engineering. These challenges raise concerns about long term durability and safety. Especially the fire risks and the leakage problems are also in question. Therefore, future research should enhance stabilization, encapsulation and fire resistance to make PCMs more practical solutions.

3.3.2. Impregnation Technique for PCM

In this technique, the building materials such as bricks, concrete, or gypsum board are dipped in a liquid PCM. As a result, the PCM is absorbed by capillarity (permeates the pores). Impregnation is still subject to the same risks as direct integration but is considered a more effective technique [

31,

44,

45,

59].

3.3.3. Encapsulation Technique for PCM

To overcome leakage and compatibility problems, encapsulation technique was developed, where PCM is enclosed or covered with a protective shell before incorporation to contain the liquid phase and hence isolated from the surroundings. To be compatible with the construction materials, the shell (or core) material must meet certain criteria like corrosion resistance, flexibility, and strength at the same time to prevent the leakage of molten PCM and the incorporation of impurities into the core system. Thus, the heat transfer area and thermal conductivity increase, and consequently an improvement of the PCM effectiveness is noticed. Despite the improvement registered in heat transfer efficiency and PCM performance, encapsulation induces also complexities such reduced thermal storage density, increased costs, and other challenges in large scale applications.

Based on the size, the capsules are referred to as macro-capsules (diameter larger than 1 mm) including Shells, tubes, panels, containers, and plastic bags [

60]; micro-capsules (diameter in the range of 1–1000μm) typically used in applications with temperature range of 10-80ºC, and nano-capsules or nano-spheres (diameter in the range of 1–1000nm) [

31,

44,

45] which were proven to offer higher thermal stability but faces degradation and fabrication issues.

3.3.4. Stabilization Techniques for Phase Change Materials

The shape-stabilized PCM (SSPCM) and the Foam-stabilized PCM (FSPCM) are two advanced methods developed to enhance PCM integration.

The SSPCMs are obtained by PCMs impregnation into porous matrices like Expanded Vermiculate (EV), Expanded Pearlite (EP), Expanded Graphite (EG), and carbon nanotubes. The capillary force, surface tension, and interactions between the PCMs and the matrix stabilize the material which prevent leakage issues during the phase change process. It is a preferred method because of its ability to maintain structural integrity over multiple cycles and improve thermal conductivity and storage.

The infiltration of the liquid/solid PCM can be elaborated through two different techniques: the two-step impregnation technique (direct impregnation or vacuum impregnation) or the one-step in situ synthesis technique. Studies showed that vacuum impregnation enhanced retention rate up to 50% compared to 30% in the non-vacuum treatment [

61].

The FSPCM, a newer approach, provides a complete retention of the PCM during melting process preventing leakage and allowing more types of PCMs to be retained. FSPCM can be obtained either by natural immersion method or vacuum incorporation. Although, the natural immersion technique is the easiest, but its low ability to retain stored thermal energy makes it less recommended compared to vacuum impregnation. FSPCM utilizes porous inorganic matrices viz; silica-based material, silica dioxide, clay materials diatomite, pearlite, etc. to contain the PCM while melting [

31,

44].

Despite their advantages in enhancing stability and thermal performance, both methods are relatively expensive, limiting their adoption in large scale applications. Thereby, the high material and processing costs raise concerns about their commercial viability.

Shohan et al. [

62] gathered the most relevant studies where PCMs were incorporated in various building materials including bricks, mortar and concrete. Their analysis as summarized in

Table 5, explore different integration methods such as encapsulation and immersion. Shohan et al. [

62] highlighted the range of transition temperature of each PCM as well and the most relevant conclusion of each study including thermal performance, efficiency and limitation on the materials in large-scale applications (

Table 5).

3.4. Change Materials: A Sustainable Approach for Heating and Cooling in Buildings

Phase change materials gained attention for thermal storage considering their ability to provide heat exchange with the environment, regulate indoor temperature fluctuations, and enable 24-hour energy supply from renewable sources [

32]. As summarized in

Table 6, their desirable characteristics such; availability, chemical stability, corrosion resistance, high durability, and higher heat storage capacity, made them a good alternative for energy efficient applications. Besides, the range of phase transition often align with the range of thermal comfort, and offers high energy density with a small storage volume [

1,

26,

28,

37,

63,

64].

For the cooling purpose, the PCMs can be integrated into various systems to enhance energy efficiency and reduce temperature fluctuation. In this matter, Chandel and Agarwal [

67] summarized the integration of PCM for cooling photovoltaic panels toward enhancing system efficiency and improving economic benefits. Maccarini et al. [

68] investigated a thermal plant configuration with a heat exchanger integrated with PCM, revealing that it could eliminate conventional cooling systems and reduce energy consumption by approximately 67%. Similarly, Garg et al. [

69] tested the PCM-incorporated heat exchanger in a rig chamber, registering a 50% reduction of heat gain and a decrease in average air temperature by over 6°C maintaining indoor temperature fluctuations stable. Saffari et al. [

70] investigated PCM-based cooling techniques in buildings. As expected, they found that the effectiveness of a specific PCM is highly dependent on the climatic conditions, its melting temperature and the occupants behavior. While Stritih et al. [

68] found that PCM-filled wall can significantly decrease the building energy consumption, supporting the goal of zero-energy buildings (ZEB). Meanwhile, Ahangari and Maerefat [

72] demonstrated that adding a layer of PCM enhanced the thermal comfort of the system by 27.39% in dry climate and 19.04% in semi-arid climate conditions of Iran based on the Fanger comfort model. Similarly, Ascione et al. [

70] evaluated the contribution of PCM integrated into various building components in reducing cooling demand in Mediterranean climates. A reduction up to 11.7% of the energy consumption during summertime has been found. Evola et al. [

71] assessed the effectiveness of PCMs in improving thermal comfort within lightweight structures during the summer season. They concluded that the organic PCMs are more appropriate for temperate climate regions than for hot Mediterranean climate regions. Jin et al. [

72] investigated the optimal placement of a thin layer in frame walls to increase thermal mass and reduce peak heat flux through the wall [

27]. All the previous research underscores that the effectiveness of PCMs is influenced by various factors including climatic conditions, PCM thickness, surface area and melting point, etc. Based on these findings, Pasupathy et Velraj [

78] and Kuznik et al. [

76] emphasize that an appropriate PCM should have a phase change temperature range aligning with indoor comfort zone, typically between 20°C and 28°C.

Canim et al. [

33] investigated the integration of PCM -paraffin wax- in pumice blocks with distinct percentage 5%, 10% and 15%. The optimum results in terms of total energy loads were found while using pumice blocks with 15%. It improved the indoor temperature fluctuations by 25% and the average wall time delay by 30%. Also, they registered a decrease in the maximum indoor temperature by 1.5ºC. They ultimately recommended pumice blocks containing PCM as valuable building material, highlighting its potential to significantly improve energy efficiency. Besides, the use of PCM in building components has shown a quite clear improvement in human thermal comfort but in most cases, the PCM layer was incorporated in the external wall of the building thus fewer data was available about the savings in the amount of cooling energy that can be achieved by using PCMs in a different part of the building [

64,

73].

To facilitate the selection of the proper PCM for a specific application, researchers gathered the main characteristics as presented in

Table 6.

4. Phase Change Materials: Addressing Drawbacks and Potential Enhancements

Depending on the solidification or melting PCM’s temperature, most research that studied the integration of one PCM layer faced the problem of suitability for only one specific season, i.e., for cooling or heating but not both. Thus, investigations are being carried out to find out solutions for both applications. Some researchers suggested the use of natural ventilation during the night to ensure the PCM discharging. Others have studied the concept of integrating two PCM layers in different parts of the building where each layer must meet the operating conditions of the suitable season.

Jin and Zhang [

75] proposed a new double-layered PCM incorporated in the building floor. They revealed that compared to a floor without PCM, the energy released by the building floor with PCM increased by 41.1% during heating and 37.9% during cooling at peak time.

Likewise, the work of Pasupathy and Velraj [

70] highlighted the value of using double-layer PCM in roof design. The mathematical model, based on the finite volume method, showed a significant improvement in thermal performance: a single layer of PCM reduced heat gain from 17 to 26%. In comparison, a double layer brought this reduction to 25-35% [

76]. However, adding a second layer of MCP had implied both additional cost and complexity in implementation. Also, Rehman et al. [

77], during their study, highlighted the effectiveness of multiple layers of phase change materials (PCM) in improving thermal comfort in buildings through conducting a numerical study on the integration of double-layer MCP into brick walls, simulating Islamabad weather conditions in January and June. By choosing PCM with melting temperatures of 29°C and 13°C, they demonstrated that this configuration improved thermal comfort throughout the year, compared to a single layer. Similarly, Almeida et al. [

78,

79] used the ESP-r simulator to model a building wall incorporating multiple layers of PCM. Their results confirmed that the addition of several layers improves the thermal performance of the building compared to a single layer.

Although these studies demonstrated a positive effect of multilayer PCM on thermal regulation, they remain limited to specific climatic conditions, numerical simulations, nature of the materials, and the configuration of the building. Further experimental validation is required to confirm these results in real-life conditions. In addition, the increased thickness of the roof may raise issues of architectural integration and compatibility with current building standards. Moreover, the economic impact and technical feasibility of such an approach are not discussed, although they are crucial for the adoption of this solution in the building sector. Finally, the long-term stability and resistance to repeated thermal cycles of PCMs must be closely examined to ensure the reliability and durability of this solution.

Besides, for thermal management applications in buildings, some researchers used commercially available PCMs, yet the desirable TES properties are not met for some materials during the incorporation, especially when considering the melting point, the leakage during the charging process, the volume changes, and the suitability of the PCM container with the wall material. To solve those problems, investigations were divided into two groups. The first group reported that these impediments can be overcome by mixing different materials in a certain proportion to obtain a composite PCM with good thermo-physical properties [

1,

31].

In this context, Sheikholeslami [

86] in his research on air conditioning machines that use porous medium, incorporated PCM to improve the material's conductivity. Thus, he used Paraffin (RT27) combined with nano-sized ZnO particles. He found that 37.15% of the required time has been reduced through the use of porous media.

Mehrizi et al. [

29] gathered the most relevant results where enhancements on building walls were elaborated using Bio-composite PCM. Results are shown in

Table 7.

The second group of investigations reported the use of double-layer PCM with composite to enhance thermal conductivity. In this regard, Sun et al. [

57] examined a radiant floor system using two hydrated salts (PCM) mixed with expanded graphite. The investigation was carried out for both winter and summer weather conditions. The heat storage layer in the floor systems was made from Na

2(HPO)4(H

2O)12-based composite with a melting temperature of 31.3ºC and the cold storage layer was made from CaCl

2•6(H

2O)-based composite with a melting temperature of 20.2ºC. They concluded that in comparison with the reference room, the radiant floor system reached 2.2 times longer thermal comfort duration during the winter season [

79].

5. Commonly Adopted Fundamental Assumptions in Leading Research Studies

These assumptions are commonly used in phase-change materials (PCM) studies [

79], but they have some limitations that can affect the accuracy of results:

This simplification is reasonable for many PCM’s, but it may be inaccurate for some materials that exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, especially near the melting point. A more detailed consideration of the rheology of CLPs could refine the models.

Natural convection plays an important role in the distribution of heat in a liquid phase PCM. By ignoring it, we may underestimate the heat transfer and therefore the real thermal performance of the system. This assumption may be acceptable for very thin layers of PCM but becomes problematic for larger thicknesses.

Although this assumption simplifies the calculations, it does not always reflect reality, especially if the envelope has a significant thermal resistance. In real-world applications, the nature of the encapsulation material can significantly influence thermal storage efficiency.

Changes in volume during solidification and melting can affect the structure and durability of the storage material. Their neglect could skew long-term performance predictions.

Thermal losses of the storage system (TES) can have a significant impact, especially on long-term storage efficiency. The integration of a thermal loss model would improve the representativeness of the simulations.

Although these assumptions simplify models and facilitate numerical simulations, they must be carefully justified in the specific conditions of each study. Experimental validation is essential to evaluate the impact of these approximations and ensure that simulation results remain reliable for real-world applications.

6. Ground-Breaking Insights and Practical Recommendations

Due to rapid population expansion and increasing energy demand, the energy crisis remains a major concern of modern society. Projections indicate that fossil fuels will continue to account for 70 to 80% of the world’s primary energy supply causing environmental issues like frequent disasters, iceberg melting, global warming, and climate change which are expected to worsen in the next few years. Various research methodologies are being promoted to tackle current environmental and energy challenges. Since the building sector is one of the most energy consumers accounting for 30% of the world’s energy production [

5], countries have implemented regulations aimed at enhancing energy efficiency in buildings and reducing the carbon footprint through developing low-carbon technologies [

62,

81] and involving bio-based products. One of the proposed solutions is to replace (or integrate) conventional materials with more efficient, eco-friendlier, and biodegradable materials [

82,

83].

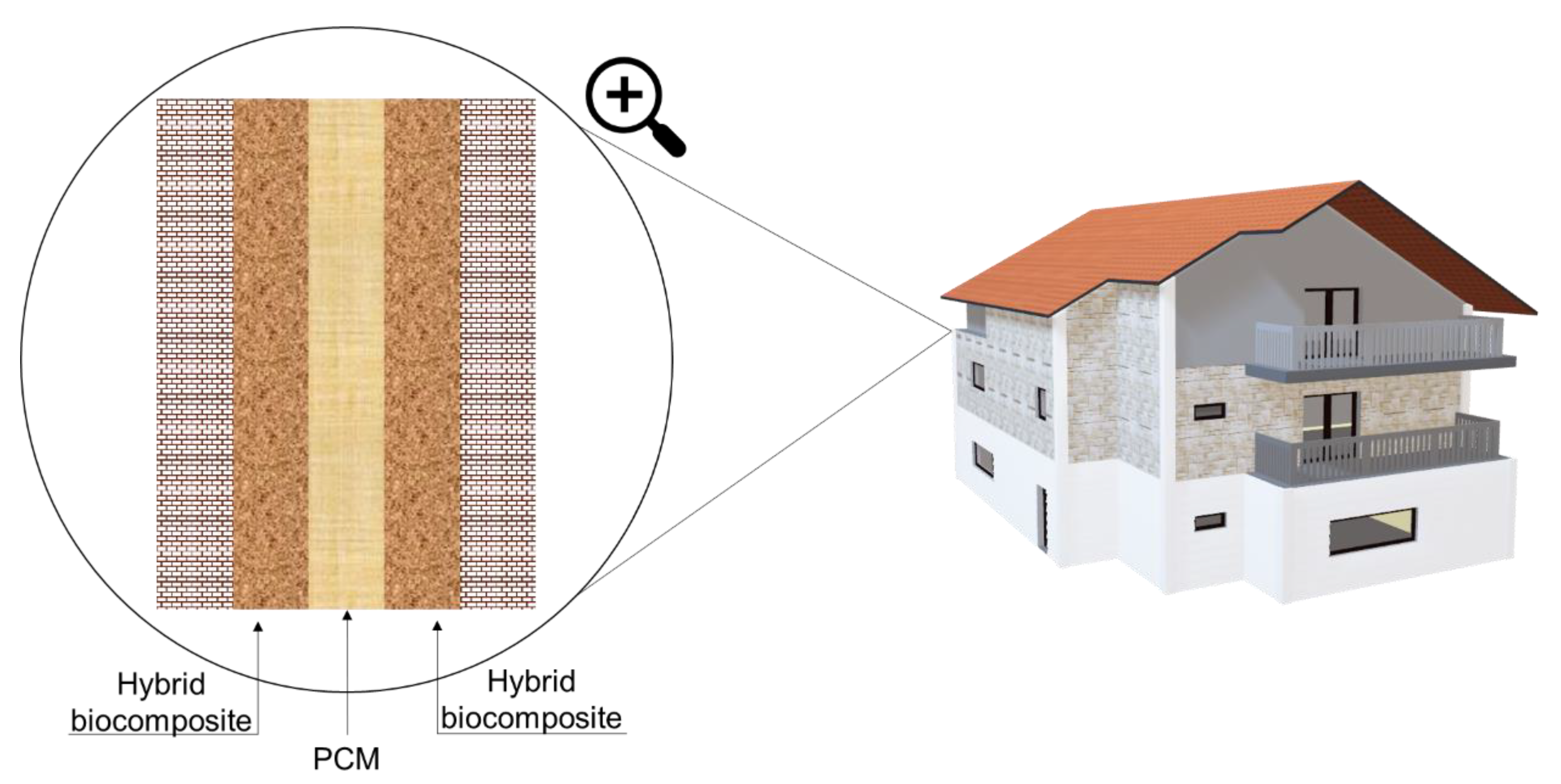

Thus, the authors of the present paper advocate a multi-layer design of walls in buildings, which is not limited to the traditional use of multiple layers of PCM or PCM combined with bio-composites. Instead, they suggest an innovative configuration consisting of a single layer of PCM sandwiched between two layers of hybrid bio-composite. This arrangement, illustrated in

Figure 13, is intended to improve the control of heat propagation through the wall structure.

The logic of this approach is in the complementary thermal and environmental benefits offered by PCM and bio-composites. The core layer of PCM functions as an efficient thermal energy buffer, storing and releasing latent heat during phase transitions to regulate indoor temperature. The bio-composite outer layers not only serve as structural and insulating elements but also contribute to environmental sustainability by using natural or recycled materials such as coffee grounds.

This multi-layer system should:

Improve thermal inertia of the wall, delay heat transfer, and stabilize indoor temperatures.

Improve energy efficiency, thereby reducing heating and cooling requirements.

Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reducing reliance on mechanical HVAC systems.

Promote waste recovery by incorporating organic by-products into building materials.

This approach is particularly relevant in the context of green building strategies and low-carbon building solutions.

6.1. Spent Coffee Grounds as PCM

Containing a considerable amount of fatty acids, spent coffee grounds (SCGs) attracted attention as bio-based phase change materials (PCM) that can be integrated into building walls, ceilings, or roofs.

Coffee stands as one of the largest agricultural commodities and enjoys widespread popularity as one of the most consumed beverages across the globe. It is integrated into mankind’s daily routine. In fact, more than 2.25 billion coffee cups are consumed every day worldwide which has resulted in an escalation of coffee production to satisfy the market demands. Coffee is considered a natural composite, containing crude fiber (lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose, poly-oligo- and mono-saccharides), lipids (free fatty acids triacylglycerides, and sterols), nitrogenous compounds and minerals [

84]. Freshly brewed coffee served in Cafés, restaurants, pubs, and coffee producers generates spent coffee grounds (SCGs) as a byproduct of the brewing process. Thus, it was found that 1 tonne of green coffee beans leads to obtaining between 550 and 670 kg of SCG which is usually sent to landfills, causing environmental issues [

43,

85]. Indeed, landfilling increases the risk of leaching active biochemicals into the environment. Considering the high organic content of SCGs, disposing of untreated excessive quantities of them could induce spontaneous combustion leading to high CO

2 and methane production and odor (from the fermentation process) emission [

43].

Yet, recent studies have shown that compared to conventional organic and inorganic PCMs, SCGs are promising green alternative bio-based PCMs. Oil extracted from SCG through different methods as supercritical fluid extraction, Soxhlet extraction, ultrasound-assisted extraction, and microwave-assisted extraction, proved to contain high value of Fatty acids (81.7%) which consist predominantly of linoleic, palmitic, stearic, and oleic acids, making coffee oil a good source of Bio-based PCM [

43,

84]. Fatty acids are considered among organic non-paraffin PCMs which are represented by the formula CH

3(CH

2)

2nCOOH and exhibit the greatest promise for applications due to their cost-effectiveness, biodegradability, and renewable nature. Compared with paraffins, fatty acids have excellent properties of phase change (solid–liquid) but they are about three times more expensive [

86].

As reported in

Table 8, the melting temperature of fatty acid ranges from -5.6°C to 79°C, and its latent heat varies between 102 kJ/kg and 212 kJ/kg [

86,

87]. In this matter, the Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) thermograms of the oil extracts (from SCG) elaborated by [

43] exhibited relatively broad melting and cooling curves, with a peak melting temperature (T

m) of 4.5 ± 0.72°C, and a peak freezing temperature (T

f) of -0.98 ± 0.59°C. Besides, the enthalpy was determined to be 51.15 ± 1.46 J/g. Additionally, the heat capacities of the coffee oil extracts were determined based on temperature variations for both phases solid (C

p,s (T)), and liquid (C

p,l (T)) phases. It was found that C

p,s (T) varied from 1.3 to 1.5 kJ/kg.K, meanwhile, C

p,l (T) was nearly temperature-independent, ranging from 1.8 to 1.9 kJ/kg.K. Further, to assess their thermal reliability and stability, coffee oil extracts were subjected to 100 melt/freeze cycles, the DSC curves displayed endothermic and exothermic peaks identical in shape to their uncycled counterparts, which indicated that coffee oil extracts were thermally stable with largely similar frequencies and intensities. The DSC outcomes for the coffee oil extracts support further explorations of coffee oil as a potential phase change material for thermal energy storage applications.

The study elaborated by Jin et al. [

43] proved the utility of usually thrown Spent coffee grounds (SCG) as a future promising biobased PCM and its potential for thermal energy storage applications. But as reported previously, the weakness of this material is its low thermal conductivity. Thus, PCMs’ heat transfer properties can be improved through enhancement methods such as fins or heat pipes. Here, authors of the present paper suggest the exploration of multilayer technique using hybrid composite regarding their thermal characteristics.

6.2. Hybrid Composite

The term of hybrid composite typically refers to a matrix that is reinforced by at least two or more types of materials. This approach aims to enhance certain properties of the composite material and reduce production costs by incorporating less expensive reinforcement [

88]. In this context, Ben Hamou et al. [

89] explored the use of hemp fibres as reinforcements in the production of bio-based composite (thermoplastic composites). The increasing interest to such technique is due to serval factors, including the material’s abundance, the biodegradable nature, durability, thermal stability, and its application in aerospace and automotive industries, as well as recent use in the construction industry. Polypropylene (PP) is the most commonly used thermoplastic (matrix) in nature fiber composite regarding its low density, strong mechanical properties, dimensional stability, and high temperature resistance [

88]. Mutjé et al. [

90] investigated the polarity of PP and hemp fibers, and they concluded that hemp fibers and PP showed hydrophilic behaviour. Besides, they found that the surface morphology of hemp fibers improved fiber-matrix adhesion. Khoathane et al. [

91] studied the thermal and mechanical properties of hemp fiber reinforced 1-pentene/PP copolymer composites. Results showed that the thermal stability of the composite surpassed that of the fiber and the matrix when considered separately.

Thus, hemp fibers emerged as a strong contender to replace glass fiber due to their superior thermal and mechanical properties. Indeed, Ben Hamou et al. [

88] assessed the thermal and mechanical behaviour of hybrid hemp/wood fiber-reinforced composites compared to pure hemp fiber and pure wood fiber-reinforced composites. The DSC results are provided in

Table 9 where the melting temperature (Tm) and enthalpy (ΔHm), as well as the crystallization temperature (Tc) and enthalpy (ΔHc) were exhibited. Notably, the melting peak for the pure PP was observed at 165°C and remained significantly unchanged in the presence of hemp fibers. However, there was a significant increase in the Tc of PP matrix from 111°C to 121°C, which can be attributed to the nucleating ability of the fibers. This increase in the crystallization rate of hemp fiber-reinforced PP bio-composites further indicates the interfacial interaction between the surface of hemp fibers and PP molecular chains, using the coupling agent PP-g-MA [

88].

7. Outlook and Emerging Trends for Future Research

To further improve the energy performance of buildings, current research continues to explore advanced techniques for integrating PCM into various structural components. The focus is on optimizing thermal regulation, improving the sustainability of PCM, and developing bio-based or waste materials such as coffee grounds. Emerging trends also focus on multi-layer configurations, encapsulation methods, and adaptive thermal systems adapted to climate variability. However, several key factors must be considered to ensure their effectiveness:

MCPs are effective in a specific temperature range, which means that their performance is dependent on climatic conditions. Some PCMs are better suited to warm climates for passive cooling applications, while others are better suited to cold climates for heating solutions. It is therefore essential to choose a PCM with a transition temperature appropriate to the thermal needs of the building.

The efficiency of a PCM depends on several parameters, such as melting and solidification temperature ranges, thermal conductivity, durability and leak resistance. For example, materials used for passive cooling must have a phase change point that corresponds to the comfort temperatures in summer, whereas heating appliances must be able to absorb and return heat efficiently in winter.

One of the major challenges in using MCPs is to ensure a good heat transfer during the heat absorption and release phases. Poor heat distribution can reduce storage efficiency and lead to uneven thermal performance in the building.

PCMs can infiltrate adjacent building materials, resulting in thermal losses and structural degradation. To overcome this problem, the use of additives, encapsulation or bio-based composites can stabilize PCMs and improve their long-term durability.

To ensure efficient use in the building, PCMs must retain its thermal properties after many cycles of melting and solidification. Degradation over time could reduce their effectiveness, making their encapsulation and chemical stability crucial for sustainable application.

The low thermal conductivity of many PCMs is a limit to their heat storage and return capacity. To remedy this, various improvement solutions exist, such as the addition of fins, metal foams or heat pipes, in order to optimize the heat transfer and maximize the efficiency of PCMs.

The location of PCMs in the building structure plays a key role in their performance. To maximize thermal benefits, it is recommended that they be positioned near heat sources (such as sun-exposed surfaces in passive solar heating systems) or areas with high temperature fluctuations. This ensures efficient absorption and return of heat to regulate the indoor temperature.

The integration of PCMs in building materials represents an innovative and effective strategy to improve energy efficiency in buildings and reduce their reliance on conventional heating and cooling systems. However, the selection of PCMs, their location, stability, and improvement in thermal conductivity are essential aspects to ensure their long-term performance. Future advances in PCM composites, encapsulation, and thermal management will further optimize their use in the design of sustainable and energy-efficient buildings.

8. Conclusions

Energy security and environmental concerns are driving numerous research initiatives aimed at enhancing energy efficiency, reducing strain on energy infrastructure, and cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. One of the most notable areas of progress is the efficiency enhancement of building heating and cooling systems, achieved through advanced technologies as heat pumps, solar collectors, chimneys, and thermal energy storage (TES). One of the most promising TES technologies is the integration of phase change materials (PCMs), in different parts of the buildings including walls, floors, ceilings, etc.

This paper provides a summary of research conducted on various PCM applications, offering insights into different types of PCM, method of encapsulations, their respective weaknesses, and enhancement techniques using additives (such as bio-composite), while addressing environmental issues. The aim is to optimize the use of PCMs in building applications. Through this review, it can be concluded that the selection of the proper PCM for a particular application, whether cooling or heating, requires careful consideration. It depends on various factors such as occupancy profile, climate, PCM melting and freezing temperature ranges, thermal conductivity, durability, the building insulation properties, and compatibility with construction materials. Incompatibility may lead to leakage or inadequate performance when it comes to direct contact.

To improve PCM performance, several solutions were proposed. Among them, the authors suggest new approach involving the use a multilayered wall. This approach would combine two layers of hybrid bio-composite specifically hybrid hemp/wood fiber-reinforced composites with PP matrix along with a layer of PCM made from Spent Coffee Grounds (SCGs).

This review explores the potential of using coffee waste residues as a green and sustainable resource for thermal energy storage, addressing the environmental concerns when sending to landfills. Previous studies on valorizing Spent Coffee Grounds (SCGs) showed promising results, which indicated that coffee oil extracts from SCGs can serve as potential bio-based phase change materials. The extracts contain approximately 60–80 % fatty acids with a phase transition temperature of approximately 4.5 ± 0.72°C and latent heat values of 51.15 ± 1.46 kJ/kg as determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). FTIR and DSC analyses were conducted on coffee oil extracts following thermal cycling and demonstrated good thermal and chemical stability.

Author Contributions

Abir HMIDA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Fouad ERCHIQUI: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Abdelkader LAAFER: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Mahmoud BOUROUIS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, École de génie- Québec-Canada.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviations |

| DSC |

Differential Scanning Calorimeter |

| DTG |

Derivatives Thermogravimetric machine |

| EG |

Expanded Graphite |

| EP |

Expanded Pearlite |

| EV |

Expanded Vermiculate |

| FSPCM |

Foam stabilised PCM |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy instrument |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| HVAC |

heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| LHS |

Latent heat storage systems |

| LTES |

Latent Thermal Energy Storage |

| MUFA |

Monounsaturated Fatty Acids |

| PCM |

Phase Change Materials |

| PUFA |

Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PVT |

Photovoltaic-thermal system |

| SCG |

Spent Coffee Grounds |

| SDG |

Sustainable development goals |

| SFA |

Saturated Fatty Acids |

| SHS |

Sensible heat storage |

| SSPCM |

Shape stabilized PCM |

| TES |

Thermal Energy Storage |

| TG |

Thermogravimetric machine |

| ZEB |

Net Zero Emissions in Building |

| Nomenclature |

| Cp |

Specific heat capacity (kJ/kg.K) |

| K |

Thermal conductivity (W/m.K) |

| Tm |

Melting temperature(ºC) |

| W0 |

Weight of extracted oil (g) |

| Wd |

Weight of the dried SCGs (g) |

| α |

Thermal expansion coefficient |

| ΔH |

Latent Heat for fusion (kJ/kg) |

| ρ |

Density (kg/m³) |

References

- Chen Z, Zhang X, Ji J, Lv Y. A review of the application of hydrated salt phase change materials in building temperature control. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022, 56, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie H, Roser M, Rosado P. Energy. Our World in Data. Published online October 27, 2022. (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Kuczyński T, Staszczuk A, Gortych M. Comparison of heavy building envelopes and PCM: Impact on indoor temperature peaks and cooling energy use during heat events. Energy. 2025, 325, 136213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Electricity 2025 – Analysis. IEA. February 14, 2025. https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2025. (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- EIA. Buildings - Energy System. IEA. July 3, 2023. Accessed July 4, 20233. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings.

- Advances in Cold-Climate-Responsive Building Envelope Design: A Comprehensive Review. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/14/11/3486.

- Faraj K, Khaled M, Faraj J, Hachem F, Castelain C. Phase change material thermal energy storage systems for cooling applications in buildings: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2020, 119, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang YX, Shu ZY, Liu ZQ, Cai Y, Wang WW, Zhao FY. Transient cooling performance and parametric characteristic of active–passive coupling cooling system integrated air-conditioner, PV-PCM envelope, and ice storage. Energy and Buildings. 2025, 329, 115296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Zhao B, Yu J, Yin X, Chang WS, Guo H. Integrating phase-change materials to reduce overheating risk in residential buildings in cold regions of China. Construction and Building Materials. 2025, 475, 141153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Buildings - Energy System. IEA. 2023. Accessed June 24, 2024. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings.

- Xu X, Mumford T, Zou PXW. Life-cycle building information modelling (BIM) engaged framework for improving building energy performance. Energy and Buildings. 2021, 231, 110496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmunem AR, Samin PM, Sopian K, Hoseinzadeh S, Al-Jaber HA, Garcia DA. Waste chicken feathers integrated with phase change materials as new inner insulation envelope for buildings. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022, 56, 106130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Policy database – Data & Statistics. IEA. July 4, 2023. Accessed on 4 July 2023 . https://www.iea.org/policies.

- European Comission. 2030 climate & energy framework. , 2023. Accessed , 2023. https://climate.ec.europa. 19 September 2030.

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), National Energy Administration. China 13th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development (in Chinese) | Green Policy Platform. December 2016. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/national-documents/china-13th-five-year-plan-energy-development-chinese.

- Li Y, Nord N, Xiao Q, Tereshchenko T. Building heating applications with phase change material: A comprehensive review. Journal of Energy Storage. 2020, 31, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmida A, Slimani MEA, El Haj Assad M, Ben Ali O. Solar Photovoltaic Thermal Collector as a Cogeneration Energy System: Conception and Recent Development in the Mediterranean Region. In: The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Springer; 2023, 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Yuan P, Duanmu L, Wang Z, Gao S, Zheng H. Thermal performance of solar-biomass energy heating system coupled with thermal storage floor and radiators in northeast China. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2024, 236, 121458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Feng L, Li X, Zoghi M, Javaherdeh K. Exergy-economic analysis and multi-objective optimization of a multi-generation system based on efficient waste heat recovery of combined wind turbine and compressed CO2 energy storage system. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2023, 96, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitz, E. Can Extremely Reflective White Paint Save the Planet? Intelligencer. July 15, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2023/07/can-extremely-reflective-white-paint-save-the-planet.html.

- Huang J, Li M, Fan D. Core-shell particles for devising high-performance full-day radiative cooling paint. Applied Materials Today. 2021, 25, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy UT, Inalli M. Impacts of some building passive design parameters on heating demand for a cold region. Building and Environment. 2006, 41, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Huang G. Development of an integrated low-carbon heating system for outdoor swimming pools for winter application. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 111, 03031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Li X, Chang C, Ju H. Multi-objective passive design and climate effects for office buildings integrating phase change material (PCM) in a cold region of China. Journal of Energy Storage. 2024, 82, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao C, Yan S, Zhao X, Zhang N, Wu Y. Design optimization of a novel annular fin on a latent heat storage device for building heating. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 64, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlé T, Hebert RL, Nguyen GTM, Ledésert BA. A composite of cross-linked polyurethane as solid–solid phase change material and plaster for building application. Energy and Buildings. 2022, 262, 111945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi VV, Chopra K, Kalidasan B, et al. Phase change material based advance solar thermal energy storage systems for building heating and cooling applications: A prospective research approach. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 2021, 47, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anter AG, Sultan AA, Hegazi AA, El Bouz MA. Thermal performance and energy saving using phase change materials (PCM) integrated in building walls. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 67, 107568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrizi AA, Karimi-Maleh H, Naddafi M, Karimi F. Application of bio-based phase change materials for effective heat management. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 61, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao VD, Pilehvar S, Salas-Bringas C, et al. Thermal analysis of geopolymer concrete walls containing microencapsulated phase change materials for building applications. Solar Energy. 2019, 178, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukram TA, Daniel J. A review of novel methods and current developments of phase change materials in the building walls for cooling applications. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 2022, 49, 101709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmen Y, Chhiti Y, El Fiti M, Salihi M, Jama C. Eccentricity analysis of annular multi-tube storage unit with phase change material. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 64, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylam Canım D, Maçka Kalfa S. Development of a new pumice block with phase change material as a building envelope component. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 61, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon F, Ruiz-Valero L, Girard A, Galleguillos H. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of a PCM-Integrated Roof for Higher Thermal Performance of Buildings. J Therm Sci. 2024, 33, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inside, K. What are phase change materials? KulKote Inside. July 21, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://kulkote-inside.com/technical/what-are-pcms.

- Al-Yasiri Q, Szabó M. Incorporation of phase change materials into building envelope for thermal comfort and energy saving: A comprehensive analysis. Journal of Building Engineering. 2021, 36, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi U, Das D, Kashyap D, et al. Synthesis and comparative analysis of biochar based form-stable phase change materials for thermal management of buildings. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022, 55, 105801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis C, Cruickshank CA. Parametric analysis of phase change materials within cold climate buildings: Effects of implementation location and properties. Energy and Buildings. 2024, 303, 113822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal ASS, Bhutta SM, Mesum IU, et al. PCM-integrated windows for enhanced passive cooling: an experimental and numerical investigation. Heat Mass Transfer. 2025, 61, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Nord N, Xiao Q, Tereshchenko T. Building heating applications with phase change material: A comprehensive review. Journal of Energy Storage. 2020, 31, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakpour Y, Seyed-Yagoobi J. Evaporating Liquid Film Flow in the Presence of Micro-Encapsulated Phase Change Materials: A Numerical Study. Journal of Heat Transfer, 0215. [CrossRef]

- Nader NA, Bulshlaibi B, Jamil M, Suwaiyah M, Uzair M. Application of Phase-Change Materials in Buildings. American Journal of Energy Engineering. 2015, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Ong P, Leow Y, Yun Debbie Soo X, et al. Valorization of Spent coffee Grounds: A sustainable resource for Bio-based phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Waste Management. 2023, 157, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawadogo M, Duquesne M, Belarbi R, Hamami AEA, Godin A. Review on the Integration of Phase Change Materials in Building Envelopes for Passive Latent Heat Storage. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11, 9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharshir SW, Joseph A, Elsharkawy M, et al. Thermal energy storage using phase change materials in building applications: A review of the recent development. Energy and Buildings. 2023, 285, 112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laasri IA, Charai M, Es-sakali N, Mghazli MO, Outzourhit A. Evaluating passive PCM performance in building envelopes for semi-arid climate: Experimental and numerical insights on hysteresis, sub-cooling, and energy savings. Journal of Building Engineering. 2024, 98, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Klemeš JJ, Zhao P, Zeng M, Wang Q. Numerical study on 2-stage phase change heat sink for cooling of photovoltaic panel. Energy. 2022, 249, 123679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia C, Geng X, Liu F, Gao Y. Thermal behavior improvement of hollow sintered bricks integrated with both thermal insulation material (TIM) and Phase-Change Material (PCM). Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 2021, 25, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaouatni A, Martaj N, Bennacer R, Lachi M, El Omari M, El Ganaoui M. Thermal building control using active ventilated block integrating phase change material. Energy and Buildings. 2019, 187, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdaoui M, Hamdaoui S, Ait Msaad A, et al. Building bricks with phase change material (PCM): Thermal performances. Construction and Building Materials. 2021, 269, 121315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechouet A, Oualim EM, Mouhib T. Effect of mechanical ventilation on the improvement of the thermal performance of PCM-incorporated double external walls: A numerical investigation under different climatic conditions in Morocco. Journal of Energy Storage. 2021, 38, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro L, De Gracia A, Castell A, Álvarez S, Cabeza LF. Design of a Prefabricated Concrete Slab with PCM Inside the Hollows. Energy Procedia. 2014, 57, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerakumar C, Sreekumar A. Phase change material based cold thermal energy storage: Materials, techniques and applications – A review. International Journal of Refrigeration. 2016, 67, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao X, Wang Y, Luo K, Wang L, Liu X, Luan Y. Energy-Saving potential of radiative cooling and phase change materials in hot Climates: A numerical study. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2025, 268, 125971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman D, Banu D, Hawes D, Ghanbari E. Obtaining an energy storing building material by direct incorporation of an organic phase change material in gypsum wallboard. Solar Energy Materials. 1991, 22, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfy Kamel J, Mouris Mina E, Moneeb Elsabbagh AM. New graphical method for assessing the integration of phase change materials into building envelope. Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 2023, 14, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Zhang Y, Ling Z, Fang X, Zhang Z. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of double-layer PCM radiant floor system containing two types of inorganic composite PCMs. Energy and Buildings. 2020, 211, 109806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Zhang X, Ji J, Lv Y. A review of the application of hydrated salt phase change materials in building temperature control. Journal of Energy Storage. 2022, 56, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Alekhin VN, Hu W, Pu J. Adaptability Analysis of Hollow Bricks with Phase-Change Materials Considering Thermal Performance and Cold Climate. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/15/4/590.

- Hu Z, Li W, Yang C, et al. Thermal performance of an active casing pipe macro-encapsulated PCM wall for space cooling and heating of residential building in hot summer and cold winter region in China. Construction and Building Materials. 2024, 422, 135831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong SG, Jeon J, Lee JH, Kim S. Optimal preparation of PCM/diatomite composites for enhancing thermal properties. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer. 2013, 62, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohan AAA, Ganesan H, Alsulamy S, et al. Developments on energy-efficient buildings using phase change materials: a sustainable building solution. Clean Techn Environ Policy. 2024, 26, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Laasri I, Es-sakali N, Outzourhit A, Oualid Mghazli M. Investigation of the impact of phase change materials at different building envelope placements in a semi-arid climate. Materials Today: Proceedings, 12 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Karaoulis, A. Investigation of Energy Performance in Conventional and Lightweight Building Components with the use of Phase Change Materials (PCMS): Energy Savings in Summer Season. Procedia Environmental Sciences. 2017, 38, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel SS, Agarwal T. Review of cooling techniques using phase change materials for enhancing efficiency of photovoltaic power systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, 73, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg H, Pandey B, Saha SK, Singh S, Banerjee R. Design and analysis of PCM based radiant heat exchanger for thermal management of buildings. Energy and Buildings. 2018, 169, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari M, de Gracia A, Ushak S, Cabeza LF. Passive cooling of buildings with phase change materials using whole-building energy simulation tools: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, 80, 1239–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritih U, Tyagi VV, Stropnik R, Paksoy H, Haghighat F, Joybari MM. Integration of passive PCM technologies for net-zero energy buildings. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2018, 41, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangari M, Maerefat M. An innovative PCM system for thermal comfort improvement and energy demand reduction in building under different climate conditions. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2019, 44, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione F, Bianco N, De Masi RF, Mastellone M, Vanoli GP. Phase Change Materials for Reducing Cooling Energy Demand and Improving Indoor Comfort: A Step-by-Step Retrofit of a Mediterranean Educational Building. Energies. 2019, 12, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola G, Marletta L, Sicurella F. A methodology for investigating the effectiveness of PCM wallboards for summer thermal comfort in buildings. Building and Environment. 2013, 59, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Medina MA, Zhang X. Numerical analysis for the optimal location of a thin PCM layer in frame walls. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2016, 103, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Laasri I, Es-sakali N, Outzourhit A, Oualid Mghazli M. Investigation of the impact of phase change materials at different building envelope placements in a semi-arid climate. Materials Today: Proceedings, 12 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Souayfane F, Fardoun F, Biwole PH. Phase change materials (PCM) for cooling applications in buildings: A review. Energy and Buildings. 2016, 129, 396–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Zhang X. Thermal analysis of a double layer phase change material floor. Applied Thermal Engineering. 2011, 31, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy A, Velraj R. Effect of double layer phase change material in building roof for year round thermal management. Energy and Buildings. 2008, 40, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman AU, Sheikh SR, Kausar Z, Grimes M, McCormack SJ. Experimental Thermal Response Study of Multilayered, Encapsulated, PCM-Integrated Building Construction Materials. accessed on 21 April 2025 . https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/15/17/6356.

- Almeida F, Zhang D, Fung A, Leong W. Investigation of Multilayered Phase-Change-Material Modeling in ESP-R. International High Performance Buildings Conference, /: online . https, 1 January.

- Arfi O, Mezaache EH, Laouer A. Numerical investigation of double layered PCM building envelope during charging cycle for energy saving. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer. 2023, 144, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Efficacy of porous foam on discharging of phase change material with inclusion of hybrid nanomaterial. Journal of Energy Storage. 2023, 62, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Chen WH, Ho SH. Economic feasibility analysis and environmental impact assessment for the comparison of conventional and microwave torrefaction of spent coffee grounds. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2023, 168, 106652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan M, Indarti E, Bairwan RD, Khalil HPSA, Abdullah CK, Ahmad A. Enhancement micro filler spent coffee grounds in catalyst - chemically modified bast fibers reinforced biodegradable materials. Bioresource Technology Reports. 2024, 25, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood TD, Nawanir G, Mahmud F, Mohamad F, Ahmad MH, AbdulGhani A. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: New problem or solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry. 2022, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaya J, Prates Pereira A, Mills-Lamptey B, Benjamin J, Chuck CJ. Conceptualization of a spent coffee grounds biorefinery: A review of existing valorisation approaches. Food and Bioproducts Processing. 2019, 118, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladi M, Martins AA, Mata TM, et al. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Spent Coffee Grounds Oil Using Response Surface Methodology. Processes. 2021, 9, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma RK, Ganesan P, Tyagi VV, Metselaar HSC, Sandaran SC. Developments in organic solid–liquid phase change materials and their applications in thermal energy storage. Energy Conversion and Management. 2015, 95, 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarier N, Onder E. Organic phase change materials and their textile applications: An overview. Thermochimica Acta. 2012, 540, 7–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamou K, Kaddami H, Elisabete F, Erchiqui F. Synergistic association of wood /hemp fibers reinforcements on mechanical, physical and thermal properties of polypropylene-based hybrid composites. Industrial Crops and Products. 2023, 192, 116052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo AC, Mohanty AK, Misra M, Drzal LT. Chopped Industrial Hemp Fiber Reinforced Cellulosic Plastic Biocomposites: Thermomechanical and Morphological Properties. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2004, 43, 4883–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutjé P, Lòpez A, Vallejos ME, López JP, Vilaseca F. Full exploitation of Cannabis sativa as reinforcement/filler of thermoplastic composite materials. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing. 2007, 38, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoathane MC, Vorster OC, Sadiku ER. Hemp Fiber-Reinforced 1-Pentene/Polypropylene Copolymer: The Effect of Fiber Loading on the Mechanical and Thermal Characteristics of the Composites. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites. 2008, 27, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).