1. Introduction

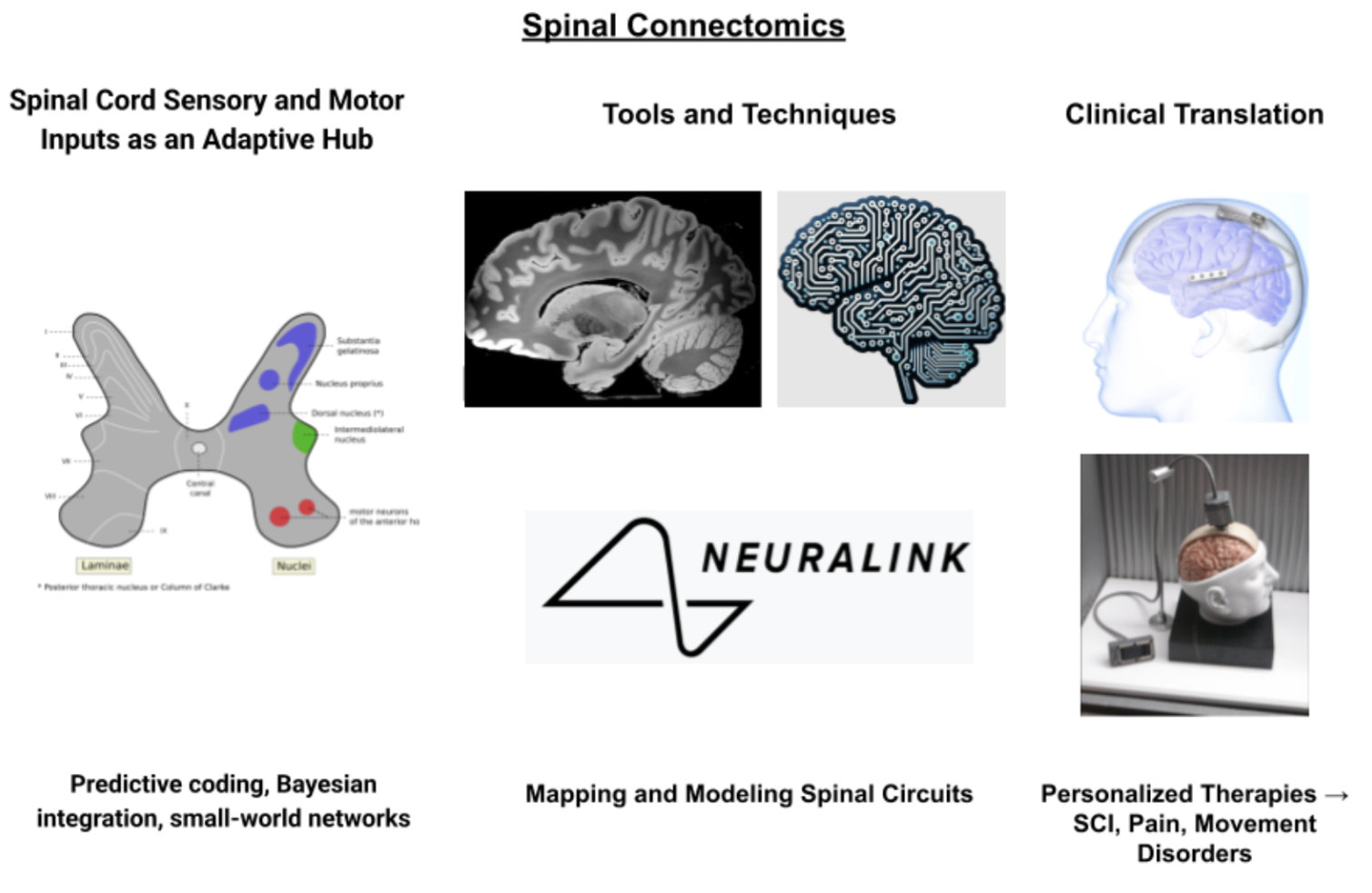

Recent developments in high-density electrophysiology, optogenetics, and brain-machine interface technologies have fundamentally changed our knowledge of spinal connectomics and neural integration mechanisms [

1]. The convergence of computational neuroscience, precision neuromodulation, and developing technologies like Neuralink in clarifying the intricate neural circuits controlling sensorimotor integration, motor control, and adaptive plasticity within spinal networks is investigated in this extensive review [

2]. Combining closed-loop neuromodulatory systems, artificial intelligence-driven discovery platforms, and multi-omics techniques marks a paradigm change toward individualized spinal interventions using both structural connectivity patterns and dynamic functional relationships [

3]. Modern studies show that spinal circuits implement predictive coding algorithms, Bayesian inference mechanisms, and context-dependent routing strategies that fundamentally change motor output based on environmental demands and behavioral context, so acting as sophisticated computational hubs rather than passive relay stations [

4,

5]. These results have significant ramifications for knowledge of neurodegenerative diseases, creation of next-generation neuroprosthetic technologies, and advancement of precision rehabilitation approaches for spinal cord injuries and associated disorders [

6].

2. Spinal Connectomics's Historical Development

2.1. From Reflex Arcs Through Computational Networks

Early twentieth-century neurophysiological studies establishing the classical reflex arc paradigm—where sensory afferents directly activated motor efferents through simple synaptic connections within spinal gray matter—generated the conceptual basis of spinal connectomics [

7]. Although fundamental for knowledge of basic spinal reflexes, this reductionist approach greatly understated the computational complexity of spinal neural networks [

8]. Sherrington and his colleagues pioneered research on complex polysynaptic pathways and reciprocal inhibition, but their findings were seen within a mostly linear, hierarchical model of neural processing [

9]. Mid-twentieth century electrophysiological recording methods started to show the great interconnectivity between spinal laminae, implying that spinal circuits had far higher integrated capacity than hitherto known [

10].

Systems neuroscience techniques emerged in the later half of the twentieth century and spurred a basic reconceptualization of spinal function from simple reflex pathways toward understanding spinal networks as dynamic computational systems [

11]. Groundbreaking studies using intracellular recording approaches showed that individual spinal interneurons obtained convergent inputs from several sensory modalities, so establishing the neuroanatomical substrate for multisensory integration within spinal circuits [

12]. These results exposed spinal networks using advanced algorithms for sensory fusion, error detection, and adaptive motor control, so subverting the accepted wisdom on modality-specific processing streams [

13,

14]. The finding of propriospinal neurons with great rostrocaudal connectivity underlined the distributed character of spinal computation by showing that motor patterns arise from coordinated activity across several spinal segments rather than from localized circuit modules [

15].

Modern developments in optogenetics, high-density electrophysiology, and viral tracking methods have transformed our capacity to map spinal connectomes with hitherto unheard-of accuracy, so exposing the organizing ideas controlling spinal network architecture [

16]. Molecularly unique interneuron populations with specialized connectivity patterns and functional roles in sensorimotor integration have been found by single-cell transcriptomic analyses [

17]. These molecular fingerprints match particular laminar distributions and projection targets, so offering a basis for knowledge of how genetic programs specify spinal circuit assembly during development [

18]. Moreover, the application of graph-theoretical analyses to spinal connectivity data reveals small-world network properties, hierarchical modular organization, and strong connectivity patterns that support effective information transfer while preserving network resilience against perturbations [

19].

2.2. Integration of Downstream Control Systems

Seeing the spinal cord as an autonomous reflex generator toward understanding it as an integral component of distributed sensorimotor control networks changed when one realized that spinal circuits receive extensive descending input from supraspinal centers [

20]. Early anatomical studies revealed that corticospinal, reticulospinal, vestibulospinal, and rubrospinal tracts—among other major descending paths—converged onto overlapping populations of spinal interneurons [

21]. This anatomical convergence proposed that spinal circuits act as integration hubs whereby many sources of descending command signals are weighted and combined with local sensory feedback to produce context-appropriate motor outputs [

22]. By means of advanced stimulation approaches, researchers were able to investigate the functional relevance of these descending inputs and show that supraspinal systems can dynamically reconfigure spinal network properties by means of neuromodulatory mechanisms [

23].

Further studies found that descending control systems use hierarchical predictive coding techniques, in which spinal circuits compute prediction errors and update motor programs while higher-order motor areas produce predictions about expected sensory consequences of motor commands [

24,

25]. This paradigm positioned spinal networks as active participants in predictive motor control rather than passive receivers of descending commands [

26]. Oscillatory coupling between cortical and spinal networks gave proof for dynamic communication channels allowing real-time coordination of motor planning and execution [

27]. While gamma-band activity (30–90 Hz) seems to communicate prediction error signals in the ascending direction, beta-band oscillations (15–30 Hz) emerged as especially important carriers of predictive signals from motor cortex to spinal circuits [

28].

The dynamic character of spinal computation was underlined by the identification of state-dependent modulation of spinal excitability by brainstem neuromodulatory systems [

29]. Strong effects on spinal network properties were found from serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic projections from brainstem nuclei, so changing the gain of sensory transmission, modifying the threshold for motor neuron activation, and affecting the temporal dynamics of spinal oscillations [

30]. These neuromodulating systems help the nervous system to adjust spinal processing to various behavioral settings, including locomotion, postural control, or expert motor performance [

31]. Understanding pathological diseases and designing focused therapeutic interventions depends much on the realization that neuromodulatory state greatly affects spinal connectome function [

32].

2.3. Emergence of Computational Models

Understanding the ideas guiding spinal connectome function and neural integration mechanisms was much advanced by the development of biologically realistic computational models of spinal networks [

33]. Using rather simplified network architectures with limited biological detail, early modeling attempts concentrated on reproducing fundamental reflex responses and basic motor patterns [

34]. Computational models changed to incorporate progressively complex representations of spinal circuit organization, including anatomically realistic connectivity matrices, biophysically detailed neuron models, and dynamic synaptic mechanisms, as experimental approaches developed and more detailed connectivity data became available [

35]. These models let scientists investigate the effects of various connectivity patterns for network behavior and test hypotheses about network function that would be experimentally intractable [

36].

Modern computational models of spinal networks use artificial neural network architectures and machine learning algorithms to replicate the intricate nonlinear dynamics seen in experimental preparations [

37]. Deep learning techniques have shown especially useful for simulating the hierarchical organization of spinal processing, so allowing the creation of models able to learn optimal control policies for various motor tasks [

38]. These models have shown how complex algorithms for motor control—including optimal feedback control, adaptive filtering, and predictive coding—may be implemented by spinal networks under appropriate conditions [

39,

40]. By including reinforcement learning ideas into spinal network models, one can gain understanding of how spinal circuits might change their connectivity patterns depending on experience and how maladaptive learning processes might lead to pathogenic conditions [

41].

By means of network theory and graph-theoretical analyses applied to spinal connectome data, basic organizing concepts guiding effective information processing in spinal networks have been revealed [

42]. High local clustering combined with short path lengths between distant nodes defines small-world network properties that seem to maximize the trade-off between local specialization and global integration in spinal circuits [

43]. While preserving flexibility to dynamically reconfigure network connectivity depending on task demands, modular organization helps to separate several functional subsystems [

44]. These organizational ideas have significant consequences for comprehending how spinal networks adapt to damage or disease processes and retain strong function despite continuous perturbations [

45].

3. Neuroanatological Basis of Spinal Connectomics

3.1. Microcircuit Architectonics and Laminar Organization

Rexed's classical anatomical system defines the laminar arrangement of spinal gray matter, which offers the basic architectural framework for comprehending spinal connectome organization and the application of neural integration mechanisms [

46]. Different populations of interneurons with specialized morphological, physiological, and connectivity characteristics allow each lamina to enable particular computational activities within the larger spinal network [

47]. Mostly nociceptive-specific cells with small receptive fields, lamina I neurons project directly to supraspinal targets including the parabrachial nucleus, periaqueductal gray, and thalamus and serve as the main entrance point for high-threshold sensory information [

48]. These projection neurons use sparse coding techniques to minimize metabolic costs and avoid saturation of ascending paths while yet allowing effective transmission of nociceptive signals [

49].

Particularly laminae IV-VI, the deeper laminae of the dorsal horn contain multireceptive interneurons and wide-dynamic-range (WDR) neurons, which are the main sites of multisensory integration in spinal circuits [

50]. Low-threshold mechanoreceptors, proprioceptors, and nociceptors among other sensory modalities provide convergent inputs to these neurons that help them to generate integrated representations of somatosensory state [

51]. Advanced electrophysiological methods have shown that WDR neurons implement sophisticated nonlinear integration algorithms that weight various sensory inputs depending on their dependability and behavioral relevance [

52].

Premotor interneurons and motor neurons that convert integrated sensory data into motor commands abound in the intermediate zone and ventral horn [

53]. Functional specialized interneuron populations with unique connectivity patterns and roles in motor control have been revealed by recent developments in optogenetic technologies and viral tracing [

54]. While propriospinal neurons give the anatomical substrate for inter-segmental coordination and the generation of complex motor patterns, commissural interneurons coordinate bilateral motor activity and ensure appropriate left-right coordination during locomotion [

55]. New understanding of the organizing concepts controlling spinal circuit assembly has come from the identification of genetically defined interneuron populations with particular developmental origins and molecular signatures [

56].

3.2. Intersegmental Integration and Propriospinal Networks

Crucially important for spinal connectome architecture, propriospinal networks provide the anatomical and functional basis for coordinating motor activity across several spinal segments and help to produce intricate, whole-body motor patterns [

57]. Interneurons with long-range axonal projections spanning several spinal segments make distributed circuits able to integrate sensory data and motor commands across the whole spinal axis in these networks [

58]. Whereas long propriospinal neurons coordinate global motor patterns including locomotion, postural adjustments, and reaching movements, short propriospinal neurons, with projections spanning 1-3 segments, primarily mediate local reflexes and fine-tune motor output within limited body regions [

59].

Different motor behaviors' biomechanical constraints and coordination needs are reflected in the functional organization of propriospinal networks [

60]. Coordinating upper limb movements and preserving head-neck stability during challenging motor tasks depend on cervical propriospinal neurons in major part [

61]. By receiving convergent inputs from several sensory modalities—including vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive signals—these neurons can implement advanced algorithms for preserving postural stability while allowing for flexible limb movements [

62]. Specialized for coordination of locomotor patterns and balance maintenance during dynamic activities, lumbar propriospinal networks’ connectivity patterns allow them to produce the fundamental locomotor rhythm by including sensory feedback, so modifying motor patterns to meet environmental demands [

63].

With the ability to reorganize their connectivity patterns in response to experience, injury, or disease, advanced neuroanatomical techniques have exposed that propriospinal networks show amazing plasticity throughout life [

64]. Multiple processes control this plasticity: activity-dependent synaptic changes, structural plasticity involving dendritic remodeling and synaptogenesis, and neuroactive factor and neuromodulatory system modulation of network excitability [

65]. Understanding recovery mechanisms after spinal cord injury and developing focused rehabilitation plans that leverage the inherent plasticity of these circuits depends on realizing that propriospinal networks can undergo significant reorganization [

66].

Hubs for Sensorimotor Integration

The existence of integration hubs—essential nodes for sensorimotor processing within spinal connectomes—has been exposed by the identification of particular anatomical sites where sensory and motor systems converge [

67]. High connectivity, receiving inputs from several sensory modalities and projecting to many motor targets, helps these hubs to influence several facets of motor control concurrently [

68]. Found in the deep dorsal horn and intermediate zone, the nucleus proprius is one of the most crucial integration centers in spinal circuits [

69]. This area is positioned to compute integrated representations of body state and motor intention by means of convergent inputs from proprioceptors, cutaneous mechanoreceptors, and descending motor paths [

70].

Another class of integration hub with specialized connectivity patterns optimized for producing coordinated motor patterns are the central pattern generator networks regulating rhythmic motor behaviors [

71]. These networks are intrinsically oscillatory, which helps them to produce rhythmic output even in the absence of sensory input; yet, they remain quite sensitive to sensory feedback and descending commands [

72]. The half-center oscillator model offers a framework for understanding how these networks create alternating patterns of activity [

73]. By means of modular organization of central pattern generators, the nervous system can produce a varied repertoire of motor behaviors while preserving the efficiency of dedicated circuits for often used patterns [

74].

Recent developments in high-resolution anatomical methods have exposed exact laminar and columnar arrangement of sensorimotor integration hubs reflecting their functional specialization [

75]. Different kinds of sensory inputs terminate in different laminar zones, allowing the separation of many kinds of sensory data prior to integration [

76]. Hub neurons' projection patterns preserve this laminar organization; different functional classes project to different targets within motor control circuits [

77]. The awareness of this exact anatomical arrangement has given fresh understanding on how spinal circuits might simultaneously process several sources of sensory data while preserving the specificity needed for exact motor control [

78].

4. Computational Systems for Spinal Processing

4.1. Error Calculation and Predictive Coding

Predictive coding algorithms implemented in spinal networks constitute a basic computational mechanism allowing sensorimotor integration and adaptive motor control [

79]. This framework suggests that descending motor commands carry predictive signals about the expected sensory consequences of motor actions, while spinal circuits compute prediction errors by contrasting these top-down predictions with actual sensory feedback [

80]. The anatomical substrate for this computation is the convergence of descending corticospinal and brainstem projections onto the same populations of spinal interneurons that receive main sensory afferents [

81]. Advanced electrophysiological studies show that spinal neurons show enhanced responses to unexpected sensory events while displaying lowered responses to predicted sensory inputs [

82].

Further proof for hierarchical predictive coding mechanisms comes from the spectral qualities of oscillatory activity in spinal circuits [

83]. While gamma-band activity (30–90 Hz) signals supraspinal centers, beta-band oscillations (15–30 Hz) in descending paths seem to carry predictive signals from higher-order motor areas to spinal circuits [

84]. This spectral asymmetry makes it possible to maximize the information content of neural transmissions by means of effective communication protocols minimizing interference between predictive and error signals [

85]. These oscillations' precisely coordinated temporal dynamics with motor action's phases imply that predictive coding runs on several timescales to maximize motor control across various behavioral environments [

86].

Many facets of spinal circuit operation, including the modulation of reflexes by motor intention, the adaptation of motor patterns to environmental perturbations, and the evolution of motor learning, have been effectively replicated by computational models implementing predictive coding concepts [

87,

88]. By means of experience, hierarchical predictive coding models have shown that spinal circuits can learn optimal control policies by means of accumulated history of prediction errors, so modifying their predictive models [

89]. This learning mechanism offers a possible reason for the amazing adaptability of motor control systems and their ability to sustain function despite continuous changes in body mechanics and environmental conditions [

90].

4.2. Bayesian Uncertainty Quantification and Integration

By means of complex Bayesian integration mechanisms, spinal circuits account for the uncertainty related to every source of information and enable best combination of sensory information from several modalities [

91]. Postural control systems especially show this computational framework since spinal networks must combine vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive signals that might give contradicting information about body orientation and stability [

92]. Experimental studies have shown that spinal circuits dynamically change the relative contributions of several sensory modalities depending on their signal-to-noise ratios and contextual dependability, so implementing dependability-based weighting schemes [

93].

The Multisensory Correlation Detector (MCD) model shows how temporal correlation analysis can be applied to evaluate the dependability and coherence of multisensory signals by offering a particular instantiation of Bayesian integration principles inside spinal circuits [

94]. This model suggests that spinal interneurons compute cross-correlations between many sensory inputs, using the strength of these correlations as a gauge of signal dependability and causal relatedness [

95]. MCD algorithms implemented in spinal circuits allow strong sensorimotor integration even in the presence of sensory noise and contradicting information [

96].

Advanced computational models including Bayesian ideas have shown that spinal circuits can implement optimal control strategies considering both sensory uncertainty and motor noise [

97]. These models show that the nervous system can learn optimal control policies that minimize expected costs [

98]. By means of uncertainty quantification, the nervous system can make suitable trade-offs between speed and accuracy, so modifying motor strategies depending on the dependability of the available sensory data and the expenses related with motor errors [

99]. This framework suggests possible therapeutic targets for intervention by offering insights into pathological conditions in which sensory uncertainty is raised or motor noise is generated [

100].

4.3. Context Modulation and Adaptive Gain Control

Adaptive gain control systems implemented in spinal circuits allow dynamic modulation of sensory transmission and motor output depending on environmental constraints and behavioral context [

101]. Presynaptic inhibition of sensory terminals, postsynaptic gain modulation of interneurons, and neuromodulatory control of network excitability are among the several pathways these mechanisms use [

102]. A particularly complex type of gain control, presynaptic inhibition allows selective modulation of particular sensory inputs without influencing target neuron excitability generally [

103]. Specialized interneurons that create axo-axonal synapses with sensory terminals mediate this mechanism, so enabling exact control over the amount of transmitter produced by various types of sensory afferents [

104].

It is now clear that context-dependent gain control is implemented by neuromodulatory systems, a key component of spinal computational mechanisms [

105]. From brainstem nuclei, descending serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic projections modulate the excitability of spinal circuits in a state-dependent manner, so allowing the nervous system to adapt spinal processing to various behavioral settings [

106]. For example, serotonergic modulation increases central pattern generator network excitability during locomotion and simultaneously reduces presynaptic inhibition of cutaneous afferents, so filtering out possibly disruptive sensory signals [

107]. This coordinated modulation guarantees that locomotor patterns can be maintained despite continuous sensory perturbations, so preserving the capacity to react to behaviorally relevant stimuli [

108].

Adaptive gain control mechanisms in computational models have shown that these systems can maximize the trade-off between sensitivity and dynamic range, so enabling spinal circuits to react efficiently to both weak and strong stimuli [

109]. By means of homeostatic plasticity mechanisms, gain control systems are guaranteed to remain constant over time, so preventing runaway excitation or total suppression of circuit activity [

110]. Understanding how spinal circuits preserve optimal function over life and how they react to injury or disease processes depends critically on the realization that gain control systems can themselves undergo plasticity and adaptation.

4.4. Synchronization and Network Dynamics

A basic computational mechanism allowing the generation of coherent motor patterns and flexible coordination of several motor systems is the coordinated dynamics of neural activity within spinal networks [

111]. With slow oscillations (< 10 Hz) coordinating large-scale motor patterns, intermediate frequencies (10-30 Hz) mediating intersegmental coordination, and fast oscillations (< 30-100 Hz) enabling exact timing of motor neuron recruitment, oscillatory activity at different frequency bands performs distinct functional roles within spinal circuits [

112]. While the amplitude of oscillations reflects the strength of network activation and the vigor of motor output, the phase relationships between oscillations in different spinal segments provide a mechanism for encoding temporal patterns essential for coordinated movement [

113].

While preserving the flexibility to reconfigure network connectivity depending on task demands, synchronizing mechanisms inside spinal networks help to coordinate activity across distributed circuit modules [

114]. Rapid synchronizing closely coupled neurons finds a substrate in gap junctions between interneurons, allowing functional assemblies to arise that can act as coherent computational units [

115]. Appropriate delays in chemical synapses help to mediate synchronisation across greater distances, so coordinating activity across several spinal segments [

116]. The degree of coordination in spinal networks is determined by the balance between synchronizing and desynchronizing influences; too much synchronizing causes pathological conditions including spasticity; too little synchronizing produces uncoordinated movement [

117].

Spinal circuits show complex dynamical behaviors including multistability, criticality, and chaotic dynamics according advanced computational models including realistic network connectivity and dynamics [

118]. Rich behavioral repertoire is made possible by these dynamical characteristics allow spinal networks to be stable and robust against perturbations [

119]. While critical dynamics enable ideal information processing and maximal responsiveness to inputs, the existence of several stable states within spinal networks provides a mechanism for motor memory and the storage of various motor patterns [

120]. Understanding how these systems preserve optimal function and how they might be disturbed by injury or disease depends critically on the realization that spinal networks operate near criticality [

121].

5. Advances in Methodology in Spinal Connectomics

5.1. High Density Electrophysiology and Laminar Recording

Our capacity to investigate the detailed microcircuit dynamics under spinal connectome function has been transformed by the development of ultra-high-density electrode arrays especially intended for spinal cord recording [

122]. With dense arrays of recording sites with micron-scale spacing that allow simultaneous monitoring of neural activity across many spinal laminae with hitherto unheard-of spatial resolution, the Neuropixels-Cord platform marks a major advance in this field [

123]. Advanced signal processing features of these devices enable real-time spike sorting and the identification of individual neurons inside the complex activity patterns of spinal networks [

124]. By means of local field potential gradient reconstruction and the identification of current sources and sinks within spinal gray matter, the high spatial density of recording sites helps to provide understanding of the biophysical mechanisms underlining network oscillations and synchronized activity [

125].

New analytical methods for understanding spinal connectome organization have been developed by means of advanced signal processing techniques applied to high-density spinal recordings [

126]. By means of temporal relationships, spike train analysis techniques can expose the functional connectivity between individual neurons, so enabling the reconstruction of effective connectivity networks from electrophysiological data [

127]. Transfer entropy measures and cross-correlation analysis offer complimentary methods for characterizing the information flow in spinal circuits and spotting directed interactions between neurons [

128]. Previously unnoticed patterns of neural activity and the discovery of functional cell types based on their activity patterns rather than anatomical features have been made possible by the development of machine learning algorithms for analysis of high-dimensional electrophysiological data [

129].

High-density electrophysiology combined with cutting-edge stimulation methods creates fresh opportunities for exploring causal relationships inside spinal circuits [

130]. Combining optogenetic stimulation of genetically defined cell populations with multi-site recording helps one to understand how activation of particular cell types affects the general network activity patterns [

131]. The methodical investigation of circuit connectivity and the identification of functional pathways inside spinal networks is made possible by electrical microstimulation with exactly controlled spatial and temporal parameters [

132]. Understanding the dynamic features of spinal circuits and developing therapeutic interventions depend much on the development of closed-loop stimulation protocols that change stimulation parameters depending on continuous neural activity [

133].

5.2. Advanced Imaging and Connectivity Mapping

Complementary to electrophysiology for tracking the activity of vast populations of spinal neurons with cellular resolution is multi-photon calcium imaging [

134]. Monitoring the activity of neurons difficult to reach with conventional electrodes—such as those found in deep laminae or those with complex dendritic arbors—this method is especially useful [

135]. By means of genetically engineered calcium indicators with enhanced kinetics and dynamic range, the temporal resolution of calcium imaging has been improved, so facilitating the identification of individual action potentials and measurement of exact spike timing relationships between neurons [

136]. Calcium imaging combined with genetic labeling methods lets one identify and monitor particular cell types in spinal circuits, so illuminating the functional roles of various neural populations [

137].

Unprecedented detail in the visualization of synaptic connectivity patterns made possible by the application of expansion microscopy and super-resolution imaging techniques to spinal tissue [

138]. These methods can expose the exact anatomical connections among several cell types and find the particular synaptic connections supporting functional interactions in spinal circuits [

139]. Automated image analysis algorithms have made it feasible to detect statistical correlations between anatomical and functional connectivity as well as to measure connectivity patterns over enormous amounts of tissue [

140]. Combining connectomic data from several methods—including electron microscopy, light microscopy, and physiological recordings—allows a whole picture of spinal circuit organization spanning several analytical levels [

141].

Refined viral tracing methods allow high specificity and temporal resolution to map functional connectivity within spinal circuits [

142]. While activity-dependent viral labeling systems can identify neurons active during particular behaviors, trans-synaptic viral tracers can show the anatomical paths linking several areas of the spinal cord and brain [

143]. By means of intersectional genetic approaches, viral tracers can be targeted to particular cell types defined by the expression of several genetic markers, so offering hitherto unheard-of specificity for circuit mapping studies [

144]. By means of viral tracing combined with functional imaging or electrophysiology, anatomical connectivity patterns can be correlated with functional relationships, so offering understanding of how anatomical structure either limits or promotes functional interactions [

145].

5.3. Computational Modeling and Simulation

Incorporating precise representations of cellular biophysics, synaptic dynamics, and network connectivity, biologically realistic computational models of spinal circuits have evolved progressively complexly [

146]. These models capture the complex integrative characteristics of spinal interneurons and motor neurons by means of morphologically and biophysically detailed neuron models [

147]. Realistic synaptic dynamics—including short-term plasticity, neuromodulation, and activity-dependent changes in synaptic strength—allows these models to replicate the complex temporal dynamics seen in experimental preparations [

148]. Simulating massive spinal networks with thousands of neurons and millions of synapses is now feasible thanks to the evolution of effective simulation algorithms and the availability of high-performance computing resources [

149].

Spinal connectome data analysis and the creation of predictive models of spinal circuit function have been subjected to increasingly use of machine learning techniques [

150]. In high-dimensional datasets, deep learning algorithms can detect intricate patterns that would be challenging to find with conventional analytical methods [

151]. While recurrent neural networks can describe the temporal dynamics of spinal circuit activity, convolutional neural networks have been successful in classifying cell types based on morphological features [

152]. New methods for comprehending the link between network structure and function in spinal circuits have been made possible by the evolution of graph neural networks especially intended for analyzing connectivity data [

153].

By means of data assimilation techniques, the integration of experimental data with computational models has made it possible to create hybrid models combining the predictive capability of computational approaches with the realism of experimental observations [

154]. These methods guarantee that models remain consistent with empirical data by means of constant updating of model parameters based on experimental observations, so guaranteeing insights into mechanisms that cannot be directly observed [

155]. Automated model fitting algorithms have made it feasible to methodically search vast parameter spaces and find model configurations that most fit experimental observations [

156]. By means of uncertainty quantification methods, one guarantees that model projections incorporate suitable confidence and dependability estimates [

157].

6. Brain-Machine Interactions and Neuralink Technologies

6.1. Signal Processing and Architectural Design of Neural Interfaces

With advanced brain-machine interface (BMI) technologies—best shown by Neuralink's integrated neural recording and stimulation platform—understanding and modification of spinal connectome function takes a radical turn [

158]. With 3072 individual recording sites arranged into ultra-thin polymer threads, Neuralink's flexible microelectrode arrays provide hitherto unheard-of access to neural signals from many spinal laminae simultaneously while reducing tissue damage and inflammatory reactions [

159]. These systems address one of the main difficulties in chronic neural recording applications by using biocompatible materials and advanced electrode coatings, so promoting long-term stability of the neural interface [

160]. Providing a complete solution for high-bandwidth neural monitoring, the miniaturized electronics package integrates sophisticated signal processing capabilities allowing real-time spike detection, feature extraction, and wireless data transmission [

161].

A key component of the Neuralink platform, the robotic surgical system created for exact electrode insertion allows electrode arrays to be placed precisely within designated spinal areas while preventing damage to blood vessels and important neural structures [

162]. To ensure ideal positioning for recording from specified cell populations, the system guides electrode insertion with micron-level accuracy using advanced computer vision algorithms and real-time imaging [

163]. The automated insertion process helps to systematically investigate several insertion techniques to maximize recording quality and lifetime by lowering variation between implantations [

164]. By lowering the tissue damage caused by electrode implantation, minimally invasive surgical techniques have improved the long-term biocompatibility of neural interfaces and so lower the risk of complications [

165].

Advanced machine learning methods are used in the signal processing algorithms built in Neuralink systems to extract relevant information from high-dimensional neural data streams [

166]. Stable single-unit recordings produced by real-time spike sorting systems help to identify and track individual neurons over extended recording periods, so supporting knowledge of the computational foundations under spinal circuit operation [

167]. By extracting motor intentions from population activity patterns, advanced decoding systems help to develop brain-activated prosthetic devices with hitherto unheard-of performance capacity [

168]. Closed-loop control algorithms let the system generate real-time feedback based on neural activity, so enabling therapeutic neuromodulation and neural plasticity induction [

169].

6.2. Two-Sided Neural Communication

Advanced BMI systems' bidirectional communication features allow both the recording of neural activity and the delivery of exactly controlled stimulation patterns to particular neural populations [

170]. Building closed-loop systems that can modify their behavior depending on continuous neural activity and give suitable feedback to the nervous system depends on this bidirectional capability [

171]. A significant progress in neural engineering has come from the creation of stimulation techniques capable of selectively activating various cell types within spinal circuits, so enabling the application of hitherto unattainable sophisticated neuromodulation techniques [

172]. Combining optogenetic techniques with electrical stimulation offers more freedom to target particular neural populations and reduce off-target consequences [

173].

By means of bidirectional BMI systems, new experimental paradigms for comprehending the causal relationships within spinal circuits have been made possible [

174]. By means of precisely timed stimulation patterns and monitoring the resultant changes in network activity, real-time perturbation experiments can test hypotheses regarding circuit function [

175]. By means of targeted stimulation and simultaneous recording from several sites, functional connectivity patterns can be mapped and important nodes within spinal networks can be identified [

176]. Understanding the dynamic characteristics of spinal circuits and optimizing therapeutic interventions depend much on the development of adaptive stimulation protocols that change stimulation parameters depending on continuous neural activity [

177].

After spinal cord damage and treating neurological diseases, the translocation of bidirectional BMI technologies to clinical uses has shown amazing promise for restoring function [

178]. By means of motor imagery alone, the Telepathy system has effectively enabled people with tetraplegia to control external devices, so proving the clinical viability of BMI approaches for bypassing damaged spinal circuits [

179]. Treating spinal cord injuries shows great potential with the development of closed-loop stimulation systems that can restore locomotor ability by synchronizing cortical activity with spinal stimulation [

180]. By means of sensory feedback systems coupled with motor BMIs, one can address one of the main constraints of present prosthetic technologies by restoring not only motor control but also somatosensory perception [

181].

6.3. Therapeutic Uses and Clinical Translation

For those with paralysis, the clinical use of sophisticated BMI technologies for spinal cord injuries has shown hitherto unheard-of success in restoring motor function and enhancing quality of life [

182]. Those with chronic spinal cord injuries have been able to regain voluntary control over paralyzed muscles and restore functional movement patterns using epidural electrical stimulation systems timed with cortical oscillations [

183]. By means of patient-specific stimulation protocols based on individual connectivity patterns and injury characteristics, the efficacy of these interventions has been enhanced and variability in treatment outcomes has been lowered [

184]. Combining rehabilitation training with BMI-enabled stimulation has shown synergistic results improving motor recovery beyond what could be obtained with either intervention alone [

185].

Another significant area of clinical translation is the use of BMI technologies to sensory restoration and pain management [

186]. New ways for treating chronic pain disorders resistant to traditional treatments are provided by closed-loop stimulation systems able to identify and stop pathological pain signals in real-time [

187]. By means of targeted neural stimulation, the development of sensory substitution systems capable of restoring touch and proprioceptive sensations offers chances for enhancing prosthetic control and so minimizing phantom limb pain in amputees [

188]. Bypassing damaged retinal circuits and directly activating visual cortex, the Blindsight system under development by Neuralink seeks to restore vision, so proving the general relevance of BMI approaches across many sensory modalities [

189].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms combined into clinical BMI systems have made it possible to create adaptive therapies able to maximize treatment parameters depending on individual patient reactions [

190]. These systems can learn ideal stimulation patterns for each patient and automatically modify therapy plans in response to changes in neural activity patterns or clinical results [

191]. By means of predictive models capable of forecasting treatment responses based on pre-intervention neural recordings, doctors can choose best treatment plans for particular patients [

192]. Closed-loop optimization algorithms with patient-reported outcome measures and objective functional assessments guarantees that treatment optimization is driven by clinically significant endpoints instead of only neural metrics [

193].

7. Molecular Mechanisms and Genetic Foundations

7.1. Spinal Circuit Assembly Transcriptual Regulation

Complex transcriptional regulatory networks controlling the expression of genes essential for neuronal development, connectivity, and function define the molecular processes guiding spinal circuit assembly and maintenance [

194]. Members of the Hox gene family among other homeodomain transcription factors are essential for defining the rostrocaudal identity of spinal neurons and providing the fundamental organizing framework of spinal circuits [

195]. Operating through hierarchical regulatory cascades that progressively refine cell fate decisions and create the molecular signals defining various class of spinal interneurons, these transcription factors define the regulatory logic controlling these networks [

196].

Recent developments in single-cell transcriptomics have exposed the amazing molecular variety of spinal interneuron populations and pointed out the transcriptional programs regulating their growth and operation [

197]. These studies have shown that there are several molecularly unique subtypes of spinal interneurons, each with particular patterns of gene expression corresponding with their functional characteristics and connectivity patterns [

198]. New tools for targeting and modifying particular interneuron subtypes have come from the identification of transcription factor combinations defining them in experimental settings [

199]. Transcriptional program temporal dynamics during development expose how cells progressively acquire their mature functional characteristics and build synaptic connections defining spinal circuit organization [

200].

Activity-dependent transcriptional control has become clear as a fundamental mechanism for adjusting spinal circuit properties to environmental demands and behavioral needs [

201]. Rapidly induced by neural activity, immediate early genes like c-fos and Arc act as molecular markers of circuit activation and also drive changes in gene expression that might alter circuit properties [

202]. Experience-dependent changes of spinal circuit function are made possible by activity-dependent transcription factors such CREB and MEF2 integrating calcium signaling with transcriptional responses [

203]. Finding activity-regulated genes that control synaptic plasticity, ion channel expression, and neurotransmitter sensitivity has shed light on the molecular basis of spinal circuit adaptation and learning [

204].

7.2. Epigenetic Control and Circuit Plasticity

Control of gene expression within spinal circuits and mediation of long-term changes in circuit function depend critically on epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation [

205]. Established during development, DNA methylation patterns help to preserve cell type-specific gene expression programs and stop inappropriate activation of transcriptional programs in developed neurons [

206]. Long-term memory storage in spinal circuits is provided by the dynamic control of DNA methylation by DNA methyltransferases and demethylases, which permits activity-dependent changes in gene expression that can last for considerable times [

207]. The identification of particular genes whose expression is controlled by DNA methylation in spinal neurons has exposed possible targets for therapeutic interventions meant to increase circuit plasticity or stop pathological changes [

208].

Another crucial layer of epigenetic control guiding gene expression in spinal circuits is histone changes [

209]. Whereas repressive marks such H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 silence gene expression, activating marks such H3K4me3 and H3K27ac promote transcriptional activation [

210]. Fast changes in gene expression in response to neural activity or environmental stimuli are made possible by the dynamic control of histone modifications by chromatin-modifying enzymes [

211]. The identification of particular histone modifications changed in response to spinal cord damage or during motor learning has shed light on the molecular processes behind circuit plasticity and possible targets for improving recovery following damage [

212].

MicroRNAs and long non-coding RNAs are two examples of non-coding RNAs that rapidly growing class of regulating molecules control gene expression in spinal circuits [

213]. By binding to complementary sequences in target mRNAs and so encouraging their degradation or translational repression, microRNAs control gene expression post-transcriptionally [

214]. Specific microRNAs enriched in several types of spinal neurons have been identified to reveal cell type-specific regulating networks and possible therapeutic targets for modification [

215]. By means of several channels, including chromatin modification, transcriptional control, and post-transcriptional control.

Verb tense: indicative

mood: subjunctive

voice: active

person: third

7.3. Genetic Strategies for Circuit Modification

Sophisticated genetic tools for spinal circuit manipulation have transformed experimental methods for knowledge of circuit function and formulation of treatment strategies [

217]. Optogenetic methods provide hitherto unheard-of temporal and spatial resolution for probing circuit function and enable exact control of neural activity in genetically defined populations of neurons [

218]. Complex experimental paradigms involving the simultaneous control of several cell types within spinal circuits have been made possible by the development of light-activated ion channels and pumps with varied spectral properties and kinetics [

219]. Optogenetic manipulation combined with electrophysiological recording or behavioral analysis allows causal links between the activity of particular cell types and circuit function or behavior to be established [

220].

In environments where optical access is restricted and over longer timescales, chemogenetic techniques offer complimentary tools for altering neural activity [

221]. By means of otherwise inert chemical compounds, designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) enable the reversible activation or inhibition of particular neural populations [

222]. Different cellular responses including changes in excitability, neurotransmitter release, and intracellular signaling cascades can be implemented by means of DREADDs with varying G-protein coupling characteristics [

223]. By means of drug dosage adjustment, one can titrate the effects of chemogenetic manipulations, so offering flexibility for investigating dose-response relationships and optimizing therapeutic interventions [

224].

Precision manipulation of gene expression and the creation of new animal models for investigating circuit function and dysfunction have been made possible by the application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technologies to spinal circuit study [

225]. By means of conditional knockout animals with cell type-specific deletion of genes of interest, one can investigate gene function in particular neural populations without influencing other cell types [

226]. By means of CRISPR-based approaches for epigenome editing, gene expression can be manipulated without changing DNA sequences, so offering means for exploring the function of epigenetic control in circuits [

227]. Combining single-cell analysis methods with CRISPR technologies helps to methodically investigate gene function across many cell types within spinal circuits [

228].

8. Therapeutic Interventions and Clinical Applications

8.1. Spinal Cord Damage and Neurorehabilitation

Targeting particular mechanisms of circuit dysfunction and encouraging recovery by means of advanced knowledge of spinal connectome organization applied to the treatment of spinal cord injury has produced revolutionary therapeutic approaches [

229]. Modern rehabilitation techniques use ideas from spinal connectomics research, including the understanding that spinal circuits have major computational capacity below the level of damage and can be retrained to produce functional motor patterns [

230]. Using the inherent plasticity of spinal circuits and strengthening residual connections, activity-based training programs that offer intensive, task-specific practice have shown amazing success in fostering motor recovery [

231]. Highly controlled training paradigms that can routinely challenge spinal circuits while providing suitable support and safety have been made possible by the development of body-weight supported treadmill training and robotic-assisted rehabilitation devices [

232].

For improving motor recovery following spinal cord damage, combining epidural electrical stimulation with activity-based training has shown especially great promise [

233]. Recent clinical studies show that combined epidural stimulation with intensive rehabilitation training helps those with chronic, complete spinal cord injuries recover voluntary control over paralyzed muscles [

234]. These treatments seem to be successful depending on the activation of residual spinal circuits that, given suitable facilitation and training, can be recruited to produce functional motor patterns [

235].

The next frontier in spinal cord injury treatment is the creation of closed-loop neuromodulation systems able to adjust stimulation parameters depending on real-time feedback from neural or behavioral measurements [

236]. Based on the patient's performance or physiological state, these systems can automatically change stimulation intensity, frequency, and spatial patterns, so optimizing therapeutic effects and reducing side effects [

237]. By means of closed-loop systems and the integration of machine learning algorithms, treatment parameters can be continuously optimized and tailored therapy protocols for every patient can be developed [

238]. Advanced BMI technologies combined with closed-loop stimulation present chances for the creation of brain-controlled rehabilitation systems able to use voluntary motor intentions to guide therapeutic stimulation and improve recovery [

239].

8.2. Sensory Problems and Long-Term Pain

Using spinal connectomics concepts to grasp and treat chronic pain has exposed fresh therapeutic targets and treatment approaches [

240]. Maladaptive changes in spinal circuit function—including sensitization of nociceptive pathways, loss of inhibitory control, and aberrant processing of sensory data—often define chronic pain disorders [

241]. By means of the identification of particular circuit mechanisms underlying various forms of chronic pain, it is now possible to create focused treatments addressing the underlying causes of pain instead of only masking symptoms [

242]. Targeting particular laminae or cell types within the dorsal horn, spinal cord stimulation approaches have shown promise for treating chronic pain disorders resistant to conventional treatments [

243].

A major step forward in the treatment of chronic pain is the creation of closed-loop pain management systems able to identify and react to pain signals in real time [

244]. These devices automatically provide suitable therapeutic interventions and use sophisticated signal processing techniques to find pain neural signatures [

245]. While lowering the risk of tolerance and dependency connected with long-term medication use, the capacity to offer quick, automatic responses to pain signals helps more efficient pain management [

246]. Within closed-loop systems, the combination of several therapeutic modalities—including electrical stimulation, drug delivery, and behavioral interventions—opens doors for complete pain management strategies capable of addressing the several facets of chronic pain [

247].

By means of the modulation of expectation and prediction systems, the application of predictive coding concepts to pain management has exposed novel strategies for addressing chronic pain [

248]. Targeting maladaptive pain predictions and catastrophic thinking patterns, cognitive-behavioral treatments aiming at these have shown success in lowering pain intensity and enhancing functional results [

249]. New tools for retraining pain processing systems and lowering pain sensitivity are presented by the development of virtual reality-based interventions able to methodically control sensory predictions and expectations [

250]. Combining these cognitive strategies with neuromodulation methods offers chances to create thorough treatment plans addressing the psychological as well as the neurological features of chronic pain [

251].

8.3. Movement Disorders and Motor Control

Important new perspectives on the circuit mechanisms underlying disorders including spasticity, dystonia, and movement disorders linked with neurodegenerative diseases have come from the application of spinal connectomics research to understanding and therapy [

252]. Common effects of spinal cord injury and other neurological disorders, spasticity is the result of malfunction of inhibitory circuits in the spinal cord that typically control muscle tone and stop too strong reflex responses [

253]. Targeting therapy approaches that can restore inhibitory balance without compromising other aspects of motor performance has been made possible by the identification of particular interneuron populations affected in spasticity [

254]. Promising for lowering spasticity while maintaining voluntary motor control are advanced neuromodulation approaches able to specifically target inhibitory circuits [

255].

Advances in knowledge of the genetic and molecular basis of spinal circuit function have helped to enable the development of precision medicine approaches to movement disorder therapy [

256]. By means of specific genetic variants affecting ion channel function, neurotransmitter metabolism, or synaptic transmission, genetic testing helps to identify candidates for focused treatments addressing the fundamental molecular mechanisms [

257]. With the possibility to fix genetic flaws influencing spinal circuit performance, preclinical studies and early clinical trials of gene therapy approaches for treating movement disorders have shown promise [

258]. Combining pharmacogenomic methods with neuromodulation devices helps to maximize therapy plans depending on unique genetic profiles and drug metabolism properties [

259].

Closed-loop neuromodulation systems applied to treat movement disorders has shown notable benefits over traditional open-loop techniques [

260]. Real-time detection of aberrant movement patterns or physiological signals by these systems allows them to provide suitable therapeutic interventions to restore motor function [

261]. With better efficacy and less side effects, the creation of adaptive deep brain stimulation systems that change stimulation parameters depending on continuous neural activity shows promise for treating Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders [

262]. Combining spinal stimulation with supraspinal neuromodulation offers chances to create complete treatment plans capable of addressing movement disorders at several levels of the nervous system [

263].

9. Future Routes and New Technologies

9.1. Computer Discovery and Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques combined into spinal connectomics research is expected to hasten discovery and provide fresh understanding of the principles controlling spinal circuit operation [

264]. Complex patterns and relationships that would be difficult to find using conventional analytical methods can be identified by foundation models educated on vast datasets of neural activity, anatomical connectivity, and behavioral outcomes [

265]. These models guide experimental design, forecast the effects of particular interventions on circuit performance, and propose fresh therapeutic targets for research [

266]. Translating AI-driven discoveries into practical scientific knowledge and therapeutic interventions will depend on the development of interpretable AI systems capable of offering mechanical insights into their predictions [

267].

Deep learning techniques applied to the analysis of high-dimensional spinal connectome datasets have already started to expose hitherto undetectable organizing ideas and functional relationships [

268]. While recurrent neural networks can model the temporal dynamics of circuit activity and predict future states depending on current activity patterns, convolutional neural networks can identify spatial patterns in anatomical connectivity data that correspond with functional properties [

269]. Graph neural networks created especially to examine connectivity data can find significant spinal network nodes and paths and project the outcomes of focused treatments [

270]. Comprehensive models that capture the multi-scale character of spinal circuit organization and function are developed by means of the integration of several data modalities inside unified AI frameworks [

271].

Another exciting use of artificial intelligence to spinal connectomics research is the evolution of AI-assisted experimental design tools [

272]. These systems can forecast likely results, propose ideal experimental parameters, and find control conditions that will maximize the information content of tests [

273]. Combining automated data analysis pipelines with artificial intelligence-driven experimental design opens chances to build autonomous discovery systems capable of generating and testing hypotheses with minimum human involvement [

274]. More effective exploration of difficult experimental environments and accelerated discovery of new principles controlling spinal circuit function is made possible by the development of active learning techniques able to adaptively modify experimental protocols depending on ongoing results [

275].

9.2. Personalized Therapy and Precision Therapeutics

Advances in spinal connectomics research and precision medicine technologies will allow a significant frontier—personalized medicine approaches for spinal diseases—to be opened [

276]. Individual variations in spinal circuit organization, genetic background, and injury characteristics lead to the necessity of tailored treatment strategies able to solve the particular mechanisms of dysfunction in every patient [

277]. By means of patient-specific computational models derived from individual anatomical and functional data, the prediction of treatment responses and the optimization of therapeutic protocols for each individual will be made possible [

278]. Combining functional connectivity measures with multi-omics data—including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—will offer complete characterizations of each patient that can direct treatment choice and optimization [

279].

Precision medicine ideas applied to neuromodulation treatment have already shown notable benefits over conventional treatment approaches [

280]. Individual variations in anatomy, connectivity patterns, and stimulation responsiveness call for tailored stimulation plans best for every patient [

281]. The continuous improvement of treatment protocols and adaptation to changes in patient status over time is made possible by the development of closed-loop optimization algorithms able to automatically modify stimulation parameters depending on real-time feedback [

282]. Combining objective neural and behavioral assessments with patient-reported outcome measures guarantees that clinically significant endpoints reflecting the functional status and quality of life of the patient guide therapy optimization [

283].

Another crucial element of individualized medicine strategies is the creation of biomarkers to forecast treatment responses and track therapeutic advancement [

284]. Objective measurements of circuit function and dysfunction linked with clinical outcomes can come from neural biomarkers produced from electrophysiological recordings, imaging data, or molecular measurements [

285]. By means of predictive biomarkers that can predict treatment responses prior to intervention start, doctors can choose best treatment plans and steer clear of useless treatments [

286]. The creation of monitoring biomarkers able to track changes in circuit performance during treatment offers feedback for the optimization of therapeutic strategies and the identification of possible side effects prior to their clinical expression [

287].

9.3. Second-Generation Neural Interfaces

Next-generation neural interface technologies will allow more complex methods of spinal circuit function monitoring and modification [

288]. Larger populations of neurons with better signal quality and less tissue damage will be accessible from flexible, biocompatible electrode arrays with higher density and better long-term stability [

289]. By combining wireless power with data transmission features, percutaneous connections will be obsolete and mechanical complications will be less likely [

290]. Long-term monitoring and stimulation uses hitherto unattainable will be made possible by the development of completely implantable systems with extended battery life [

291].

Novel sensing modalities included into neural interfaces will give access to fresh kinds of data on spinal circuit operation [

292]. Using either intrinsic optical signals or genetically engineered indicators, optical sensors track neural activity and offer complimentary information to electrical recordings [

293]. Concerning neurotransmitter levels and other molecular signals reflecting circuit activity and neuromodulatory states, chemical sensors can offer insights [

294]. Multiple sensing modalities combined within unified interface platforms will offer thorough monitoring capabilities capable of capturing various facets of circuit operation and more whole characterizations of neural states [

295].

More complex therapeutic interventions will be made possible by the evolution of bidirectional neural interfaces with advanced stimulation capacity [

296]. Targeting various cell types and circuit mechanisms is made flexible by multi-modal stimulation systems able to provide electrical, optical, magnetic, and ultrasonic stimulation [

297]. Closed-loop stimulation methods that can adapt to continuous changes in circuit activity and patient status can be implemented by means of real-time feedback control [

298]. The simultaneous targeting of several circuit components and the application of sophisticated spatiotemporal stimulation patterns capable of either replicating natural activity patterns or generating new therapeutic effects are made possible by the development of distributed stimulation systems with many independent channels.

10. Conclusions

Precision medicine, advanced neural interface technologies, and spinal connectomics research taken together provide hitherto unheard-of possibilities for knowledge and treatment of nervous system diseases. Our knowledge of spinal function has been fundamentally changed and new therapeutic targets for intervention have been exposed by the realization that spinal circuits execute sophisticated computational algorithms including predictive coding, Bayesian integration, and adaptive gain control. Advanced imaging technologies, optogenetic manipulation tools, and high-density recording technologies have given the methodological basis for probing spinal circuit function with hitherto unheard-of accuracy and revealing the organizing principles controlling circuit assembly and plasticity.

Already showing amazing success in creating new treatments for spinal cord injury, chronic pain, and movement disorders, the clinical translation of spinal connectomics research. Brain-machine interface technologies combined with rehabilitation training have allowed those with paralysis to restore functional movement patterns and recover voluntary control over paralyzed muscles. Closed-loop neuromodulation systems have given fresh, more efficient methods for treating movement disorders and chronic pain that have less side effects than traditional treatments. By applying precision medicine ideas to these treatments, customized treatment plans addressing the particular mechanisms of dysfunction in individual patients have been developed.

Looking ahead, spinal connectomics research combined with artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques promises to speed discovery and provide fresh insights on the principles controlling spinal circuit operation. New tools for both research and therapeutic uses will come from the evolution of next-generation neural interfaces with enhanced monitoring and modulating power for neural activity. Personalized medicine approaches' ongoing development will help to create ever more complex and potent treatments catered to individual patient traits and needs. These advances taken together show a paradigm shift toward precision neurology that could revolutionize the treatment of neurological diseases and enhance the quality of life for millions of patients all around.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: RK, KS, PP, RJ, NZ; Data curation: CG, AK, PP; Formal analysis: KS, RJ, NZ; Investigation: RK, CG, AK, PP, SC, TK; Methodology: KS, RJ, PP, NZ; Project administration: PP, LC, NZ; Resources: SC, TK, LC; Software: RJ, NZ; Supervision: PP, LC, SC, TK, NZ; Validation: RK, KS, CG, AK; Writing - original draft: RK, KS, CG, PP; Writing - review & editing: PP, LC, SC, TK, NZ.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was waived.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Catherine Wang for providing us an APC waiver for this submission, which enabled this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Courtine, G.; Sofroniew, M. V. Spinal cord repair: advances in biology and technology. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, L. R.; Bacher, D.; Jarosiewicz, B. Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm. Nature 2012, 485, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greicius, M. D.; Krasnow, B.; Reiss, A. L. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K. J.; Shiner, T.; FitzGerald, T. Dopamine, affordance and active inference. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, C. A.; Boakye, M.; Morton, R. A. Recovery of over-ground walking after chronic motor complete spinal cord injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C. S. Reflex inhibition as a factor in the co-ordination of movements and postures. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 1913, 6, 251–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillner, S.; Wallén, P. Central pattern generators for locomotion, with special reference to vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1985, 8, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. G. The intrinsic factors in the act of progression in the mammal. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 1911, 84, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J. C.; Fatt, P.; Koketsu, K. Cholinergic and inhibitory synapses in a pathway from motor-axon collaterals to motoneurones. J. Physiol. 1954, 126, 524–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzi, E.; Cheung, V. C.; d'Avella, A. Combining modules for movement. Brain Res. Rev. 2008, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska, E.; Roberts, W. J. Synaptic actions of single interneurones mediating reciprocal Ia inhibition of motoneurones. J. Physiol. 1972, 222, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, P. S.; Smith, J. L. Neural and biomechanical control strategies for different forms of vertebrate hindlimb locomotion. Adv. Neurol. 1997, 74, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, S.; Dubuc, R.; Gossard, J. P. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 89–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J. R.; Graham, B. A.; Galea, M. P. The role of propriospinal neuronal networks in locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience 2011, 192, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alstermark, B.; Isa, T. Circuits for skilled reaching and grasping. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häring, M.; Zeisel, A.; Hochgerner, H. Neuronal atlas of the dorsal horn defines its architecture and links sensory input to transcriptional cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessell, T. M. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000, 1, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporns, O.; Tononi, G.; Kötter, R. The human connectome: a structural description of the human brain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2005, 1, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, R. N. Descending pathways in motor control. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 31, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, H. G.; Martin, G. F. Descending pathways to the spinal cord. Prog. Brain Res. 1982, 57, 1–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, T.; Prentice, S.; Schepens, B. Cortical and brainstem control of locomotion. Prog. Brain Res. 2004, 143, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, L. M.; Liu, J.; Hedlund, P. B. New developments in the control of locomotion: modulation of spinal circuits by supraspinal systems. Prog. Brain Res. 2008, 171, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R. A.; Shipp, S.; Friston, K. J. Predictions not commands: active inference in the motor system. Brain Struct. Funct. 2013, 218, 611–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpert, D. M.; Flanagan, J. R. Motor prediction. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, R729–R732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadmehr, R.; Krakauer, J. W. A computational neuroanatomy for motor control. Exp. Brain Res. 2008, 185, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoffelen, J. M.; Oostenveld, R.; Fries, P. Neuronal coherence as a mechanism of effective corticospinal interaction. Science 2005, 308, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilavik, B. E.; Zaepffel, M.; Brovelli, A. The ups and downs of beta oscillations in sensorimotor cortex. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 245, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckman, C. J.; Lee, R. H.; Brownstone, R. M. Hyperexcitable dendrites in motoneurons and their neuromodulatory control during motor behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B. L.; Fornal, C. A. Serotonin and motor activity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1997, 7, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultborn, H.; Nielsen, J. B. Spinal control of locomotion—from cat to man. Acta Physiol. 2007, 189, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viemari, J. C.; Ramirez, J. M. Norepinephrine differentially modulates different types of respiratory pacemaker neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 9280–9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijspeert, A. J. Central pattern generators for locomotion control in animals and robots: a review. Neural Netw. 2008, 21, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getting, P. A. Emerging principles governing the operation of neural networks. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1989, 12, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak, I. A.; Shevtsova, N. A.; Lafreniere-Roula, M. Modelling spinal circuitry involved in locomotor pattern generation: insights from deletions during fictive locomotion. J. Physiol. 2006, 577, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasmith, C.; Anderson, C. H. Neural engineering: computation, representation, and dynamics in neurobiological systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2004, 15, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussillo, D.; Abbott, L. F. Generating coherent patterns of activity from chaotic neural networks. Neuron 2009, 63, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorov, E.; Jordan, M. I. Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körding, K. P.; Wolpert, D. M. Bayesian integration in sensorimotor learning. Nature 2004, 427, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, D. W.; Wolpert, D. M. Computational mechanisms of sensorimotor control. Neuron 2011, 72, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, P.; Daw, N. D. Decision theory, reinforcement learning, and the brain. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2008, 8, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, D. J.; Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, D.; Lambiotte, R.; Bullmore, E. T. Modular and hierarchically modular organization of brain networks. Front. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinov, M.; Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 2010, 52, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rexed, B. The cytoarchitectonic organization of the spinal cord in the cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1952, 96, 414–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, A. J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A. D. Pain mechanisms: labeled lines versus convergence in central processing. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 26, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, S. A.; De Koninck, Y. Integration of developing and adult pain pathways. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 88, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]