1. Introduction

The emergence of neural networks has facilitated the development of artificial intelligence (AI), defined as the ability of machines to simulate human cognitive processes. With the advancement of neural networks, the tasks they address have become increasingly complex, often involving the handling of high-dimensional data to satisfy specific requirements. To enhance performance, deep neural networks have evolved to more accurately mimic human brain functions, leading to substantial increases in computational cost and training time [

1]. Typically,DNNs have many layers with fully-connected neurons, which contain most of the network parameters (i.e. the weighted connections), leading to a quadratic number of connections with respect to their number of neurons [

2].

To address this issue, the concept of sparse connected Multi-layer Perceptrons with evolutionary training was introduced. This algorithm, when compared to fully connected DNNs, can substantially reduce computational cost on a large scale. Moreover, with feature extraction, sparsely connected DNNs can maintain performance comparable to that of fully connected models.

However, this approach still demands considerable computational resources and time, which remains a limitation. Furthermore, the introduction of motif-based DNNs, which can retrain neurons using small structural groups (e.g., groups of three neurons), suggested the potential to surpass the performance of sparse connected DNNs and significantly enhance overall network efficiency. This paper aims to analyze and test motif-based DNNs, comparing their performance against benchmark models.

To provide a deeper understanding, the following sections will delve into the foundational aspects of these approaches.

As mentioned before, traditional neural networks are usually densely connected, meaning that each neuron is connected to every other neuron in the previous layer, resulting in a large number of parameters. Unlike normal DNNs models, SET helps introduce sparsity, reduce redundant parameters in the network, and improve computational efficiency. Through the evolutionary algorithm, SET can gradually optimize the weights so that many connections become irrelevant or zero [

2]. Therefore, SET is applied to improve training efficiency by optimizing the sparse structure of the model and reducing redundant parameters, which eventually can end in a reduction of the computational cost [

3].

To further improve the performance of the Deep Neural Network, feature engineering is considered as a critical step in the development of machine learning models, involving the selection, extraction, and transformation of raw data into meaningful features that enhance model performance [

4]. By enforcing sparsity in the neural network, SET effectively prunes less important connections, thereby implicitly selecting the most relevant features. As the evolutionary algorithm optimizes the network, connections that contribute insignificantly to the model’s performance are gradually set to zero, allowing the network to focus on the most informative features. If feature selection can be applied in this process, with some important features selected and remaining features dropped, the complexity of the network would be largely decreased and the quantified features would keep the original accuracy. Consequently, SET feature selection results in a streamlined model that is both computationally efficient and more accurate, leading to better overall performance [

3], and Neil Kichler has demonstrated the effectiveness and robustness of this algorithm in his studies, further validating its practical application and benefits [? ].

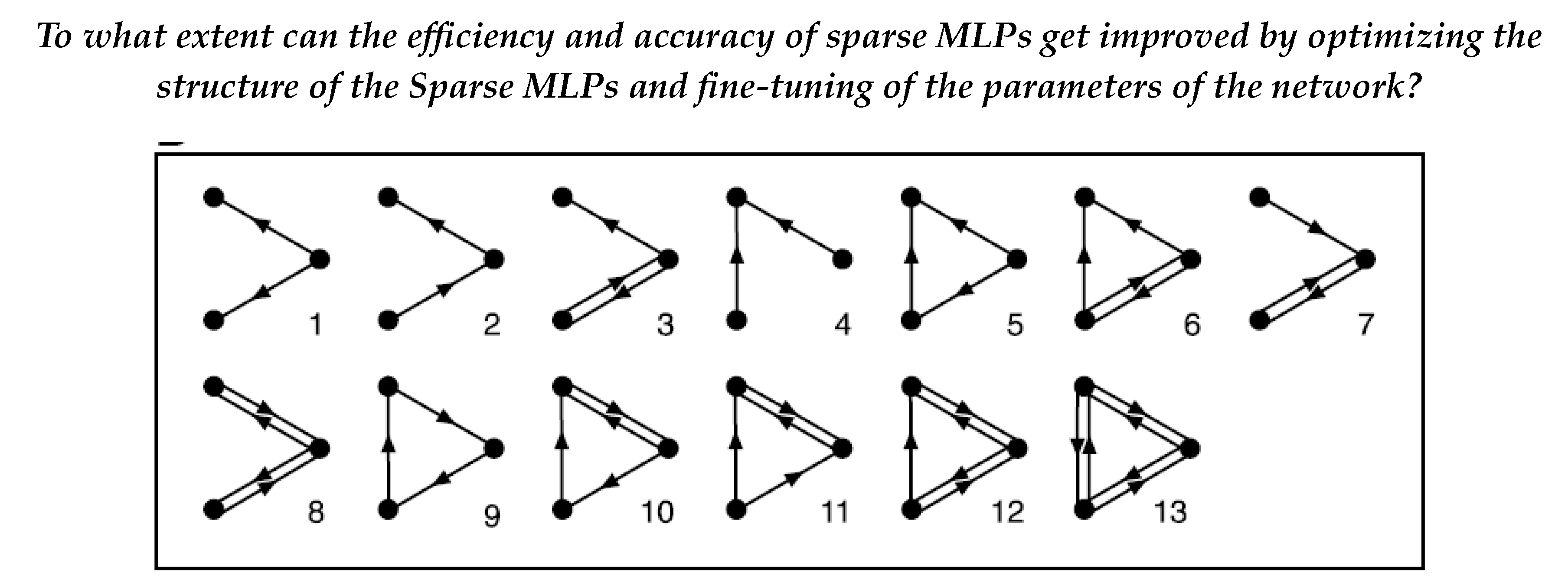

Network motifs are significant, recurring patterns of connections within complex networks. They reveal fundamental structural and functional insights in systems like gene regulation, ecological food webs, neural networks, and engineering designs. By comparing the occurrence of these motifs in real versus randomized networks, researchers can identify key patterns that help to understand and optimize various natural and engineered systems.

As mentioned before, the SET updates new random weights when the weights of the connections are negative or insignificant (close to or equal to zero) which to some extent lead to some computation burden [

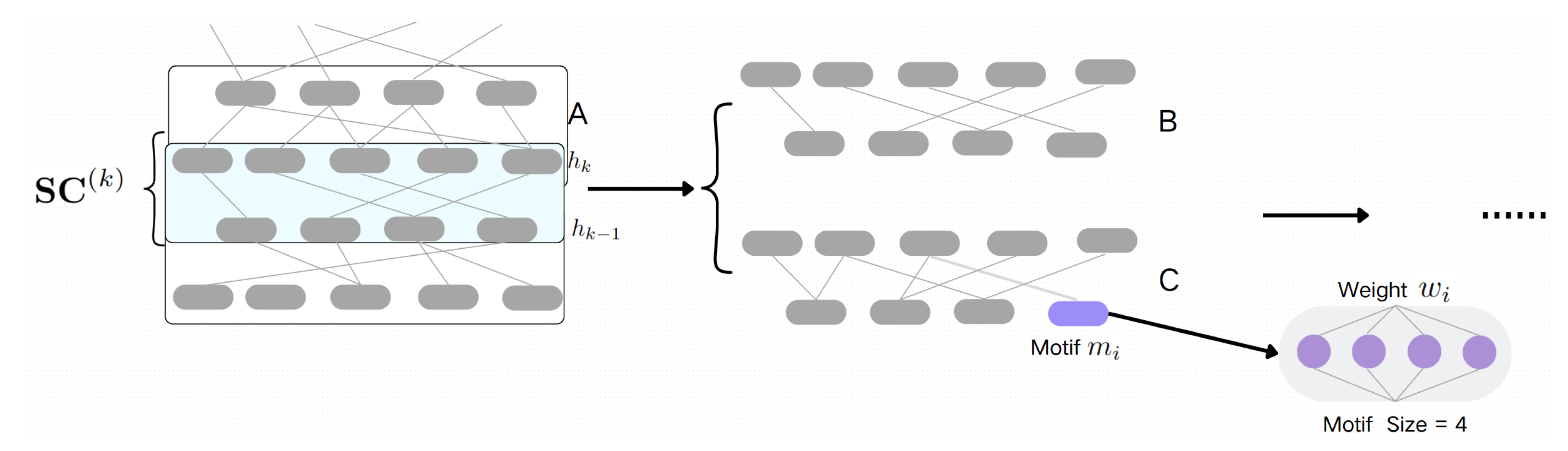

5]. Based on the concept of motif and SET, a structurally sparse MLPs is proposed. The motif-based structural optimization gave an idea of renewing the weights by establishing a topology which can largely improve the efficiency (shown in

Figure 1) [

6,

7].

The key research question is posed in this paper is:

Figure 1.

Motif-based Structural Sparse MLPs [

7].

Figure 1.

Motif-based Structural Sparse MLPs [

7].

2. Related Work

Sparse MLP models have demonstrated significant potential in reducing computational costs (e.g., hardware and computation time requirements) while enhancing accuracy through feature extraction and sparse training. This research uses the work of Mocanu et al. as a benchmark model for comparison [

3]. This section reviews the historical development of sparse neural networks. Subsequently, the key idea and algorithm of SET will be discussed. Lastly, the basic idea of structural optimization of Sparse MLPs will be introduced.

Y. LeCun et al. [

8] introduced the concept of network pruning in the paper "Optimal Brain Damage" in 1990. This approach calculated the contribution of each connection to the general network error and selectively removed some of the nodes which are considered less important. Utilizing second-order derivatives, this method effectively reduced model complexity while preserving performance. Therefore, this seminal work provided and was regarded as a theoretical basis for later pruning techniques. Based on the seminal paper, B. Hassibi et al. proposed the "Optimal Brain Surgeon" method in 1993, in which second-order derivatives was also used but offered a more precise method for pruning the weights by considering the Hessian matrix’s structure [

9]. The Optimal Brain Surgeon method was shown to achieve superior performance by more accurately identifying and removing redundant connections. This refinement was regarded as an important step forward in the efficiency of network pruning. In 2016, Han et al. introduced the concept of "Deep Compression", a concept which combines pruning, quantization, and Huffman encoding [

10]. This three-step method significantly reduces the storage requirements and computational cost of neural networks while maintaining the accuracy. In addition to the standard sparse network training steps, such as initial pruning followed by weight retraining, Deep Compression incorporates Huffman encoding as a final step. This study highlighted the practical advantages of integrating multiple optimization techniques. In 2018, Mocanu et al. introduced the idea of Sparse Evolutionary Training in their paper "Scalable Training of Artificial Neural Networks with Adaptive Sparse Connectivity Inspired by Network Science" [

3]. In this research, Erdős-Rényi graph initialization is used to create the initial sparse network and initialized the weights. By selectively adding, removing connections based on the deviation and performance, SET aims to maintain a high proportion of zero-valued connections while optimizing the model’s accuracy. The process of the SET algorithm is shown as

Figure 2. As mentioned above, this model will be taken as the benchmark mark to compare with the one in this research.

Based on the previous research work, the concept of "Dynamic Sparse Reparameterization" was given by J. Frankle et al which is a method continually adjusting the sparsity of network connections during training [

11]. By dynamically reparameterizing the network, this approach helps maintain a balance between performance and efficiency. This method stands out for its ability to adaptively optimize the network structure dynamically, leading to more efficient training processes. Based on the research of Mocanu et al., the paper ’Robustness of sparse MLPs for supervised feature selection’ by Kichler [? ] in 2021 combined with feature extraction with sparse multi-layer training method which promoted the development of research. With a certain proportion of features dropped, the performance of the neural network can still maintain as densely connected network.

The motif-base is concept referring to certain type of structural topology or network structure, which is usually used to describe a sub-network or a network pattern (shown in

Figure 3). This diagram illustrates the general procedure of motif-based optimized SET models. The DNNs model on the left are trained and retrained by individual nodes [

12]. Therefore, the weights between nodes are different from each other. However, for the motif-based model, the weights will be initialized and retrained by small groups with a specific size of nodes [

13]. By applying the motif-base structure, the efficiency of the network can be improved while maintaining the accuracy.

3. Methodology

To address the research questions related to the motif-based structural optimization of sparsely connected neural networks, this section provides a detailed illustration of the proposed approaches. This section discusses the topological optimization method. Subsequently, the process of training will be discussed. Finally, the evaluation environment for this research is described.

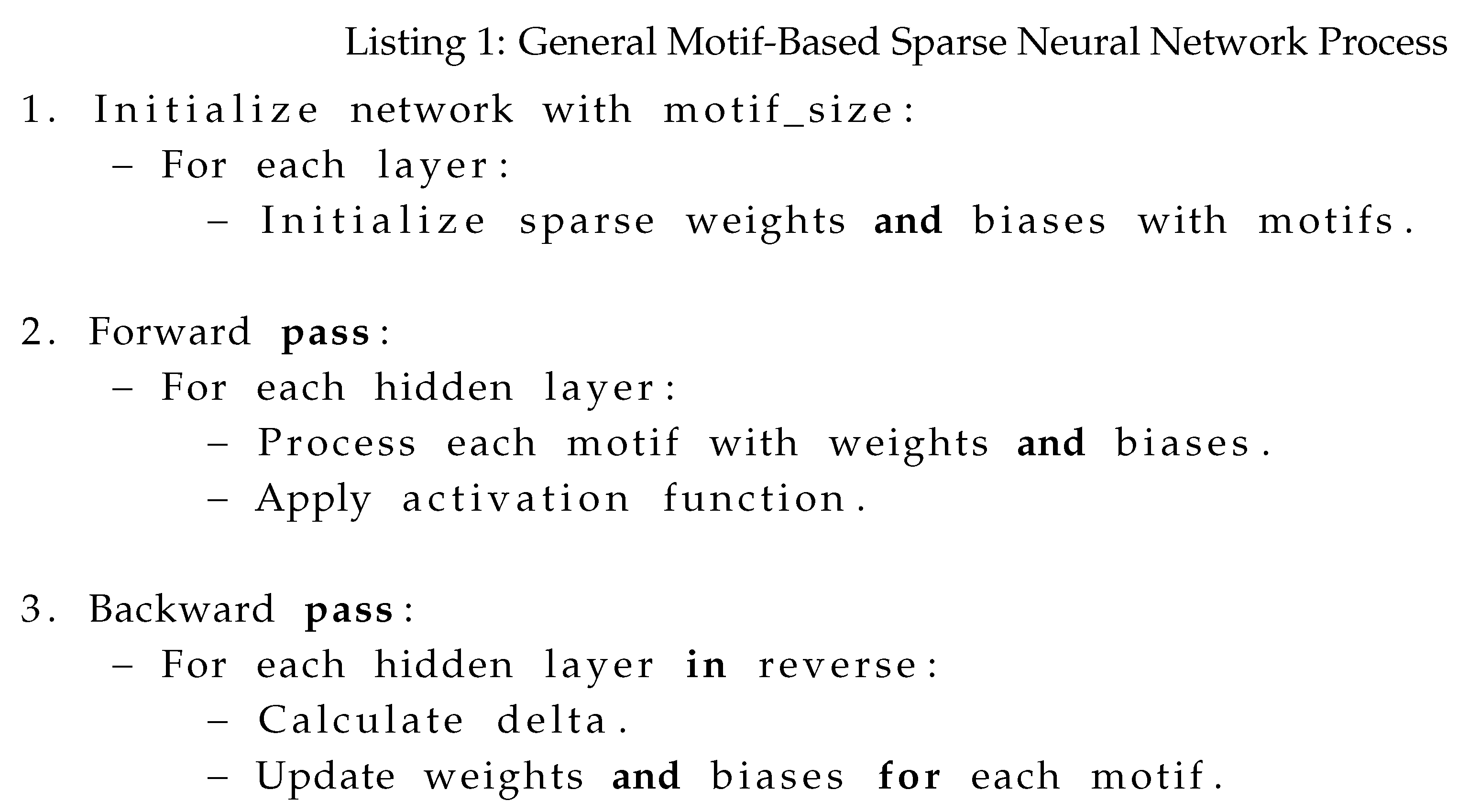

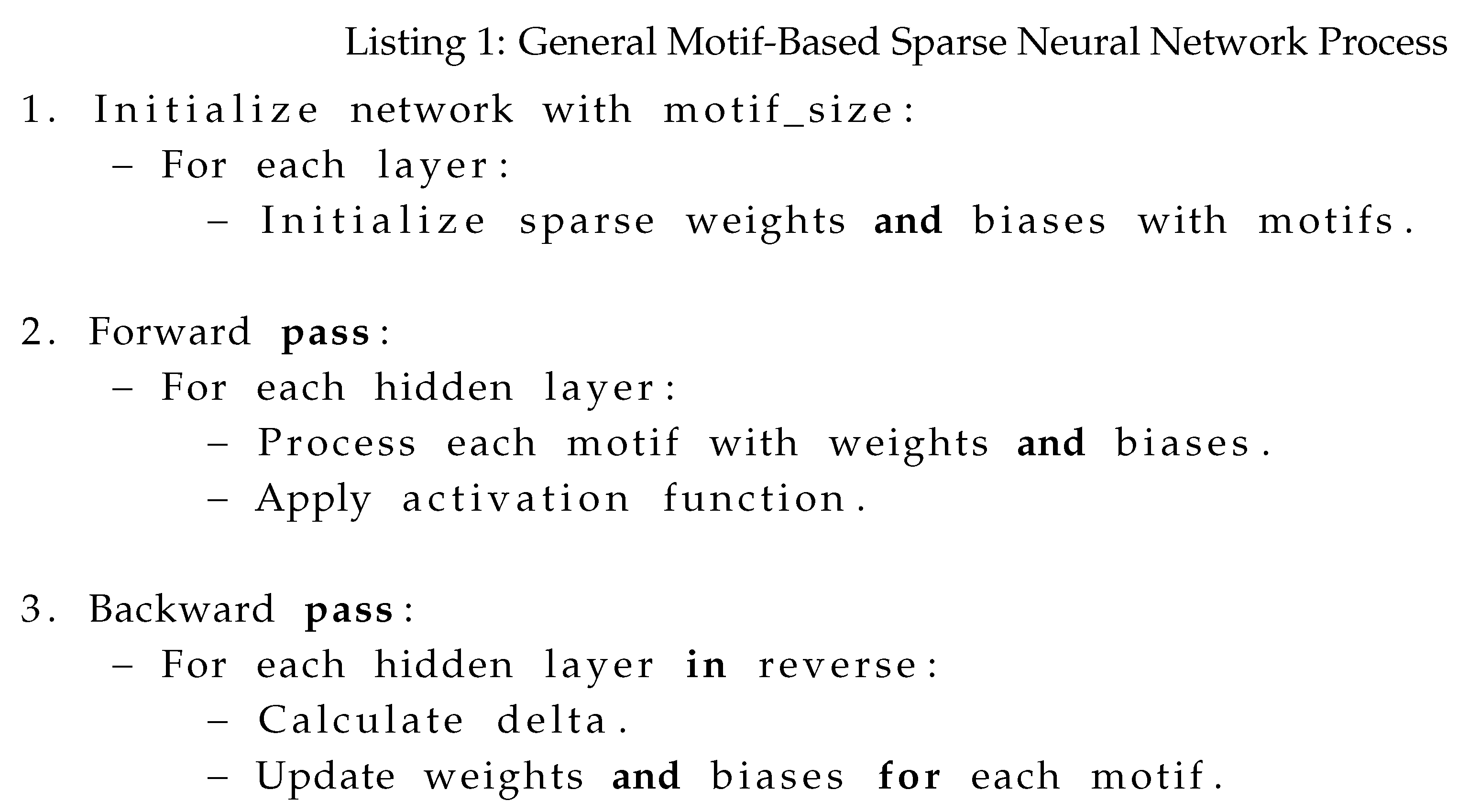

The core principle of motif-based structural optimization in SET involves assigning weights between neurons based on motifs during each training process, followed by distributing these weights to individual nodes. The following pseudo code is the general training process of the motif-based SET model:

This pseudo code outlines the process of network initialization, forward propagation, and backward propagation in the motif-based DNN model. As previously noted, most steps are performed using customizable motifs of a specific size. A detailed explanation of the network construction and training process is provided in the following subsections.

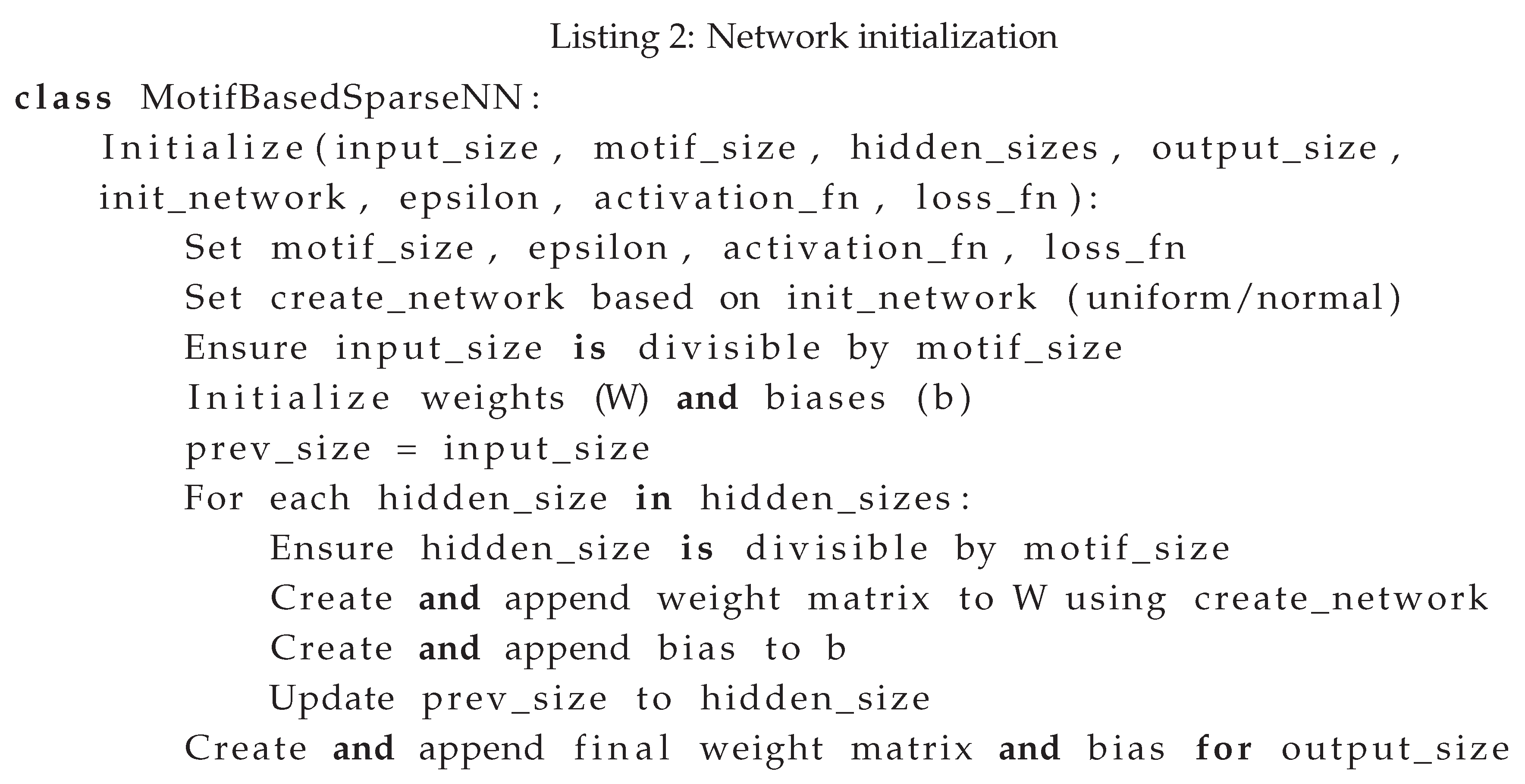

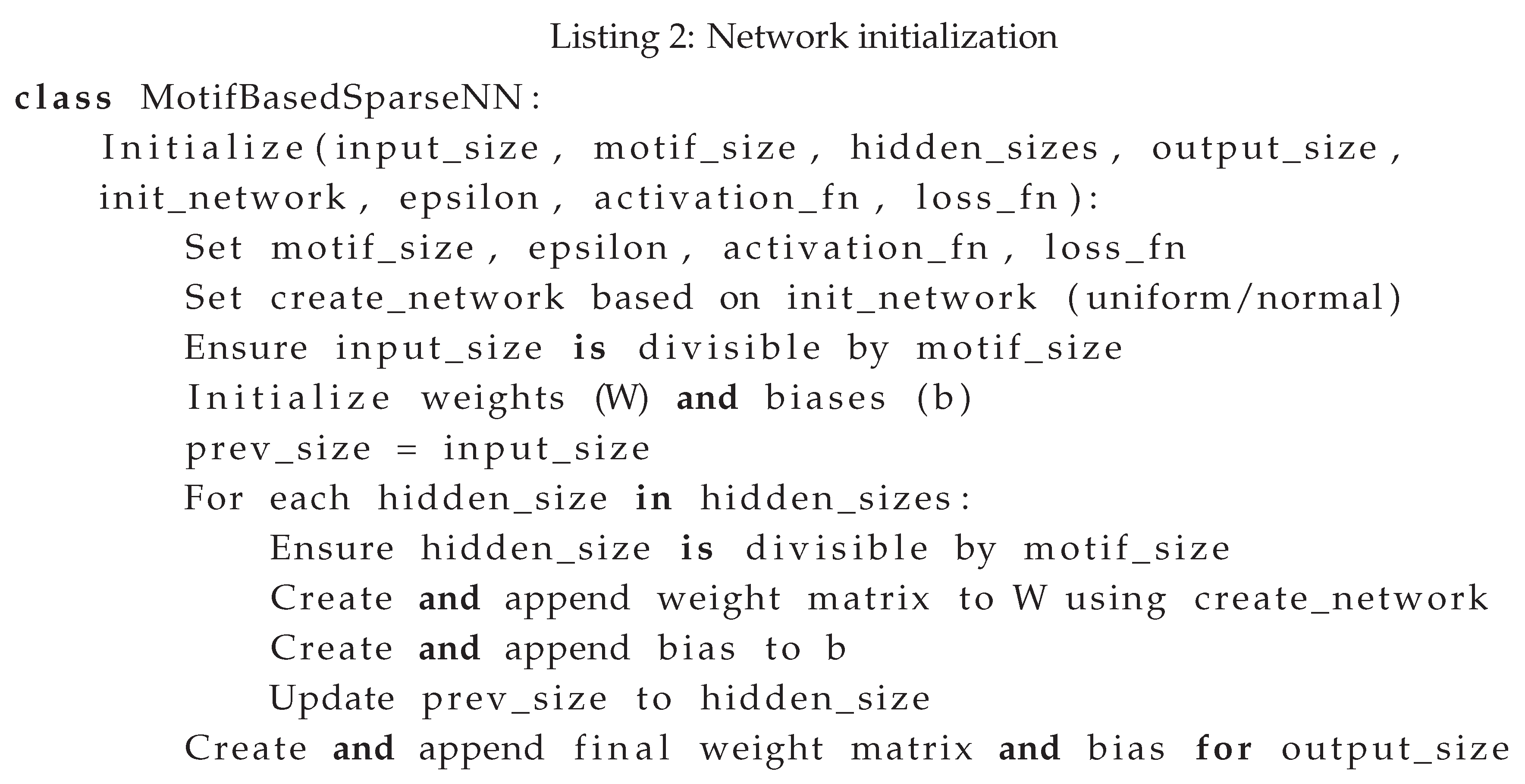

3.1. Network Construction

The general idea of using structural optimization based on motif is to group nodes with a certain size and train them together. Unlike simply reducing the number of neurons, each node in the motif-based optimized network participates in both training and retraining. The key difference lies in the process of assigning new weights to nodes, which is conducted according to a specific topology, thereby enhancing the network’s efficiency [

6,

14].

Parameter Initialization: Before initializing the weights of neural networks, some parameters need to be defined. The input size

X refers to the size of the features of the training data set that is selected as input. For instance, for the Fashion MNIST dataset, the number of pixels in the graph is 784 (28X28); therefore, the input size is 784. The motif size

m refers to the size of a topology or sub-network. Hidden size refers to the number of neurons for each hidden layer [

15]. Epsilon

is a parameter controlling the sparsity level of the network. The activation function

is used to introduce non-linearity into the model. The loss function

L measures the difference between the predicted outputs and the actual outputs [

16].

Weights and Bias Initialization: The random uniform distribution is utilized for generating the initial weights. The weights are assigned to each motif instead each node which will be more efficient. The He function is used here to set limitations for the weights [

17]. Erdős-Rényi is used for setting sparse weights masks which can remove or keep the initial weights. And for each layer, it creates a random bias vector

. The motif size also needs to be chosen such that the input size is divisible by the motif size. [

11]The pseudo code for network construction is shown as follows:

Comparing to the normal SET model, instead of initializing the weights and bias individually, the weights and bias initialization in this project are done by motifs, for instance 3 nodes as motif. The weights and bias are first assigned to each motif then each motif will assign the parameters to each node which are the same within each motif. Additionally the motif-size of the model can be customized. In this way, the efficiency of the network initialization will be largely improved.

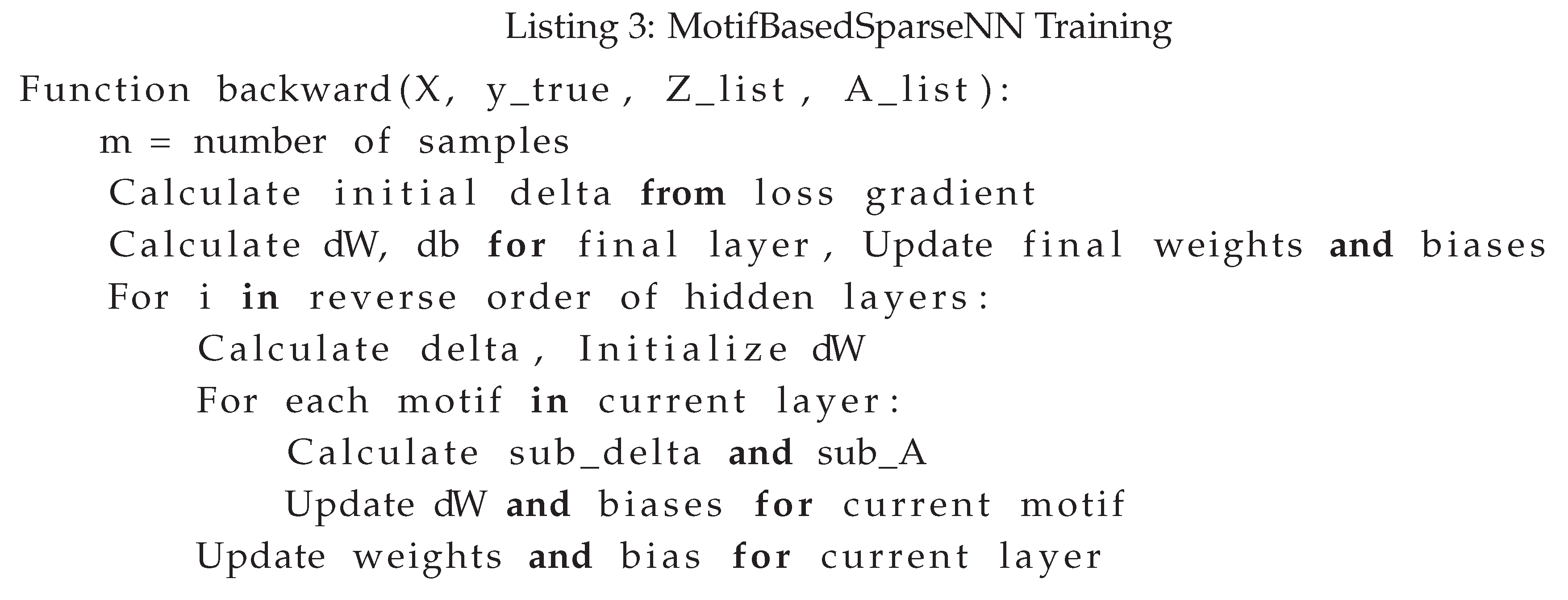

3.2. Training Process

This subsection will show the process of the motif-based model training which is the core of the whole project.

Forward Propagation: The forward function is similar to normal forward propagation in other models; the only difference in this project is that the nodes involved in the forward propagation process are trained in small groups [

18] which will improve the total efficiency. The process is shown as following equations,

representing the linear combination of

i layer,

for the activation function for each layer(ReLu, Softmax, Sigmoid),

for weight matrix for

i layer,

for bias [

19]. For each motif in layer

i:

For the output layer, the Softmax is chosen as the activation function because it converts raw model outputs into probabilities, ensuring they sum to 1. This is crucial for multi-class classification, providing clear and interpretable probabilities for each class.

Backward Propagation: In the process of backward propagation, the output layer error

needs to be calculated first, where

is the output of the network and

is the true label:

Then the gradient for the output layer and each hidden layer needs to be computed in a reversed order:

For each hidden layer

i from

to 1:

Motif-based computation for each hidden layer, a zero matrix

is initialized. And for each motif

j in layer

i, each submatrix

from weight matrix

is extracted:

The sub-delta and sub-activation for each motif are calculated:

Update gradients for each motif and node individually:

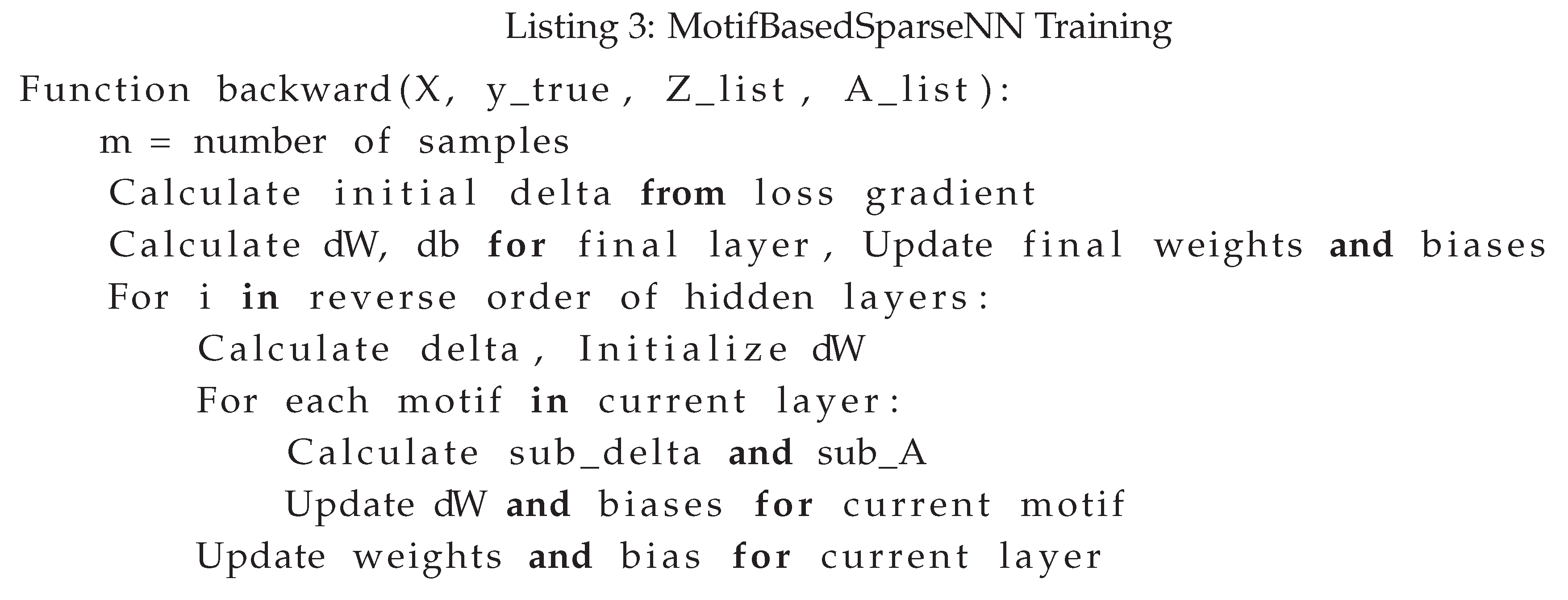

In the end of backward propagation, the weights and bias are updated for each layer.The pseudo code of back propagation is shown as following:

Followed by forward propagation, the backward propagation training will also be trained by motifs in each layer, each motif will assign the retrained results to each node. Therefore, the

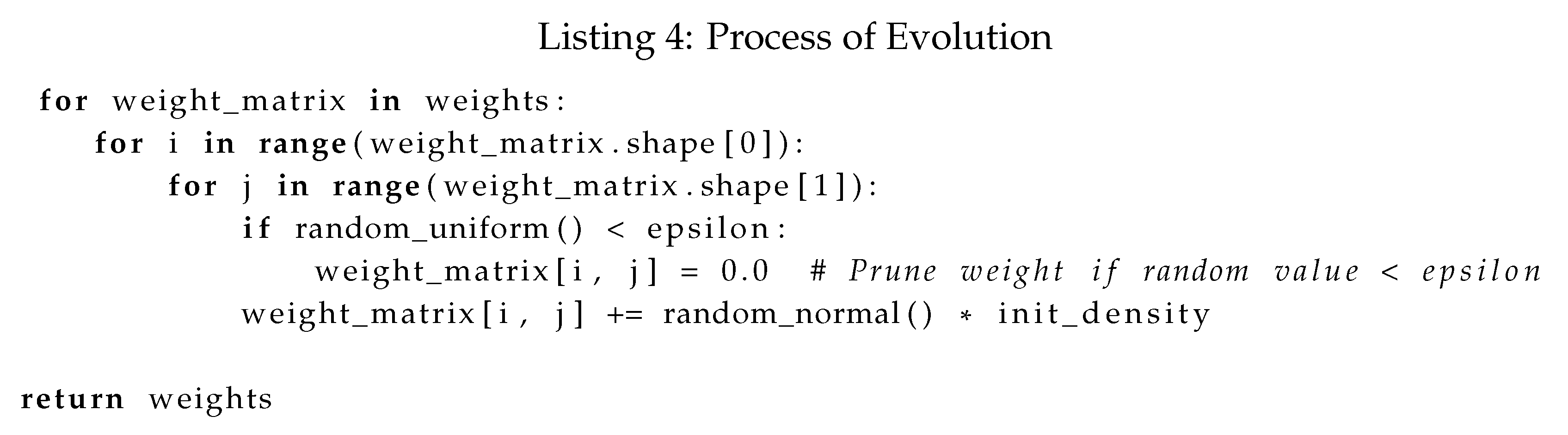

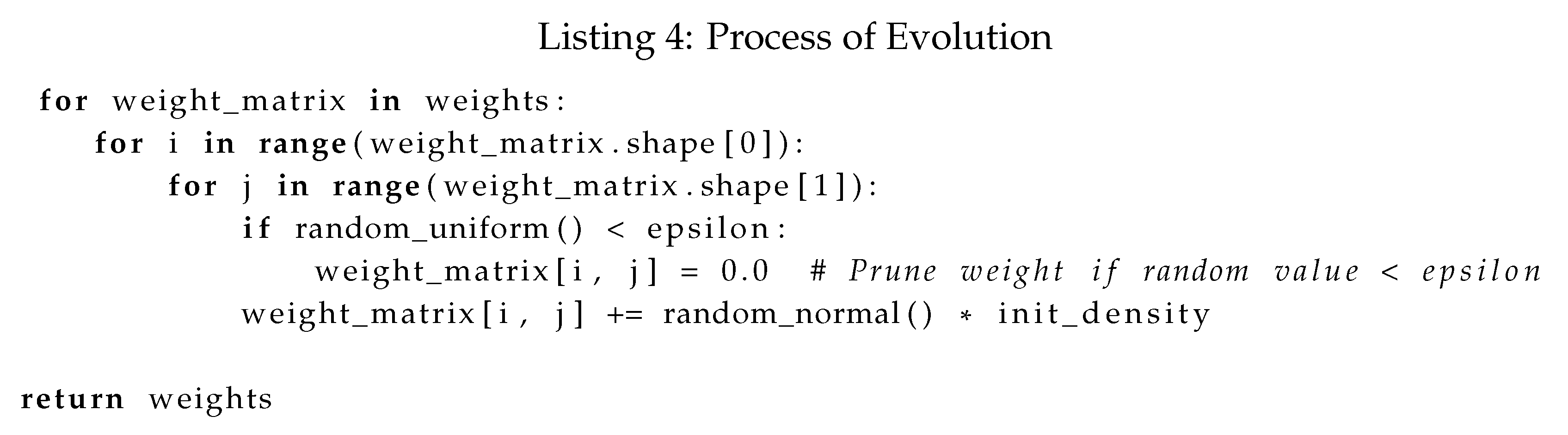

3.3. Process of Evolution

The core of the SET algorithm involves evolution, where weights close to zero are pruned and new weights are assigned [

3]. The pseudo-code for this process is provided below:

4. Experiment

This section outlines the experimental process, starting with data preparation, followed by experimental design and evaluation. The aim is to assess the efficiency and accuracy of the motif-based sparse neural network compared to the benchmark model.

4.1. Data Preparation

In this research, the Fashion MNIST (FMNIST) and Lung datasets are used as benchmark datasets to evaluate the performance and efficiency of the model [

20]. The FMNIST dataset (shown in

Figure 4) is widely recognized as a benchmark for testing deep learning architectures. It is a dataset of Zalando’s article images—which consists of a training set of 60,000 samples and a test set of 10,000 samples. Each sample is a 28x28 grayscale image associated with a label from one of 10 classes [? ]. This study loads the images using TensorFlow’s FMNIST module, normalizes pixel values to

, and applies one-hot encoding to the categorical labels. Optionally, it standardizes data using scikit-learn’s StandardScaler and stores preprocessed data in compressed .npz files for efficient access and reuse. This pipeline ensures the dataset is ready for machine learning tasks, facilitating robust model training and evaluation.

The Lung dataset also contains grayscale X-ray scans indicating five lung conditions, represented as five distinct labels. A sample from the Lung dataset is shown in

Figure 5. The dataset is initially loaded and its labels are converted into one-hot encoded format. Subsequently, the dataset is split into training and testing sets, reserving one-third for testing purposes. Feature normalization is then performed using StandardScaler library, ensuring consistent scaling across the dataset.

The properties of two datasets are shown in

Table 1.

4.2. Design of the Experiment

As mentioned above, in this experiment Fashion MNIST and Lung are the two benchmark datasets used to test the accuracy and performance of the motif-base sparse neural network model. The benchmark model is set as the SET model [

3]. To evaluate the performance and resource utilization of the model on the datasets, a comprehensive experimental setup was implemented. This setup includes data preprocessing steps such as standardization and one-hot encoding, as well as model initialization and training procedures. Functions were incorporated to retrieve CPU and GPU information to monitor hardware usage. The start and end times of the training process were recorded to calculate the total execution time [

21]. Finally, the results, including test accuracy and resource details, were saved to a file for thorough analysis. This approach ensures a detailed and reproducible evaluation of the model’s performance and resource efficiency.

Design of FMNIST Testing: the Fashion MNIST has 784 features which is the input size for the neural network, therefore, the motif size is set as 1 for benchmark model, 2 and 4 for model testing. The number of neurons for each hidden layer is 3000 [

15,

22]. To further test the efficiency and show the differences of each motif-size model, a simpler version of DNN model is developed with 2 hidden layers and each one with 1000 neurons.

The Lung dataset has 3312 features which is the input size for the neural network and divisible by 1, 2 and 4. Therefore, 4 motif sizes are designed for testing. Like the FMNIST dataset, a simpler version of model with 2 hidden layers( 1000 neurons for each ) is designed and will be tested. In order to ensure the rigor of the experiment, the control variable method was applied here, the number of epochs is set to 300, the learning rate is set to 0.05, sparsity is set to 0.1.

To better evaluate the performance of each motif-size model, a comprehensive score (

S) that combines the percentage reduction in running time (

) and the percentage reduction in accuracy (

) is designed [

23]. Typically, for a DNN model, accuracy is significantly more important than efficiency [

24,

25]. Therefore, the accuracy reduction is weighted at 90% and the running time reduction is weighted at 10%. The comprehensive score is calculated using the following formula:

where:

D In these equations:

S is the comprehensive score.

is the percentage of running time reduction.

is the percentage of accuracy reduction.

is the running time observed for benchmark model.

T is the running time for the specific motif-size model.

is thebenchmark model accuracy.

A is the accuracy for the specific motif-size model.

5. Results

This section first presents the final results for each dataset and each motif size model. Furthermore, the model with the best overall performance for each dataset is identified, addressing the research question in

1 by providing exact accuracy and efficiency metrics.

5.1. Experiment Results

This subsection presents and analyzes the results for both the FMNIST and Lung datasets.

5.1.1. Results of FMNIST

In this test, 300 epochs were run with 3 hidden layers (3000 neurons for each). The result is shown in

Table 2, when the motif size is set to 1 the total running time is 25236.2 seconds, with an accuracy of 0.761. When the motif size is set to 2, the total running time is 14307.5 and the accuracy is 0.723. Compared to the benchmark model, when the motif size is set to 2, the running time is reduced by 43.3%, while the accuracy decreases by 3.7%. When the motif size is set to 4, the total running time is 9209.3 seconds and the accuracy is 0.692. Comparing to the benchmark model, the efficiency is improved by 73.7% with 9.7% drop in accuracy.

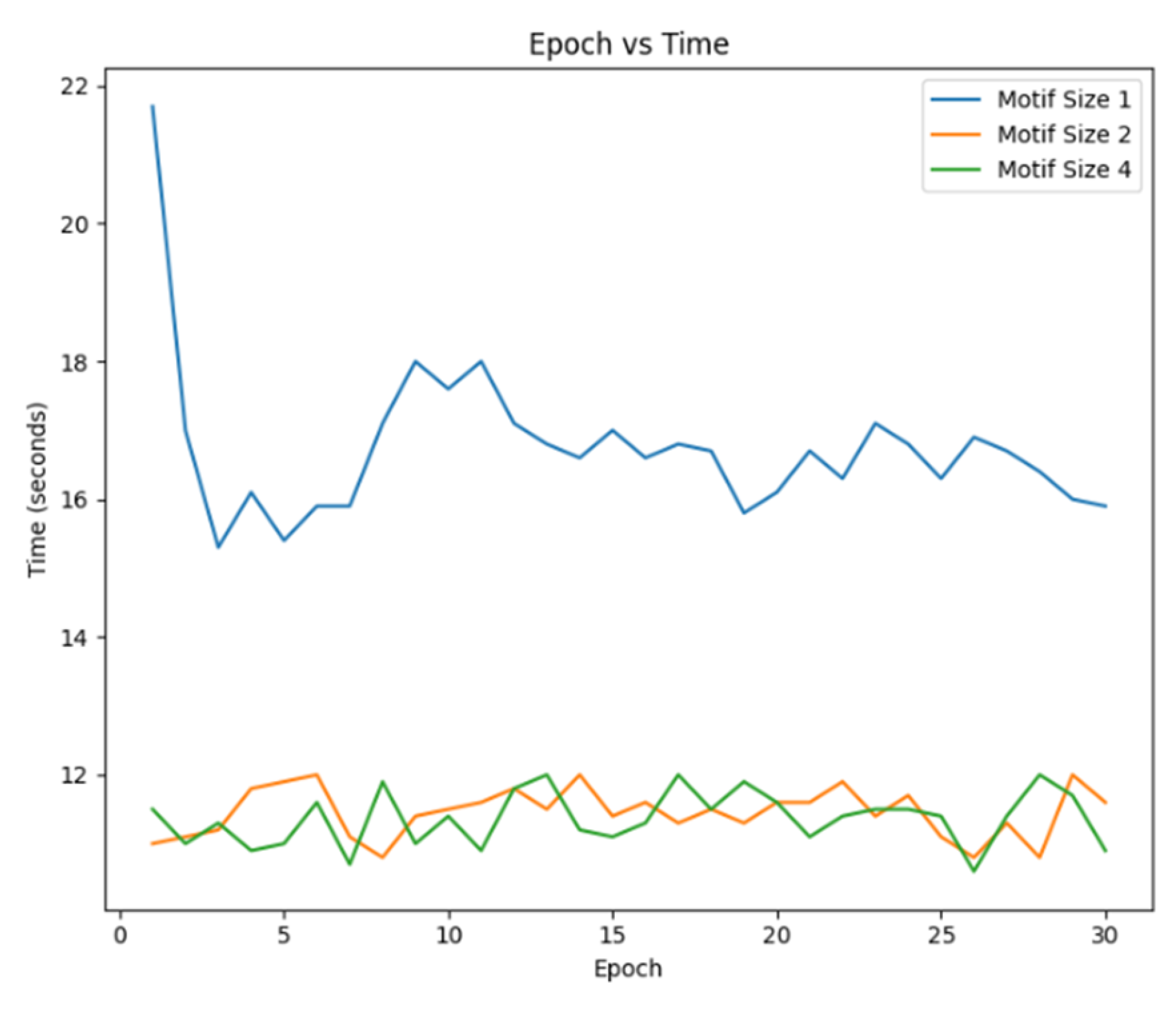

To further validate the efficiency of each motif size, a simpler model is established for testing the running time which has 2 hidden layers and each one of them has 1000 neurons.

Table 2 presents the average running time per epoch. The running time for the first 30 epochs is recorded and shown in

Figure 7, which corroborates the results mentioned above.

Table 2.

Result of each motif size (FMNIST)

Table 2.

Result of each motif size (FMNIST)

| Motif Size |

Running Time (s) |

Accuracy |

Average Running Time (s) |

| Motif Size:1 (SET) |

25236.2 |

0.7610 |

17.73 |

| Motif Size:2 |

14307.5 |

0.7330 |

9.14 |

| Motif Size:4 |

9209.3 |

0.6920 |

6.74 |

Taking both efficiency and performance into consideration, the comprehensive score for each motif size is then given by:

For motif size 4:

According to the result, When the motif size is set to 2, the model has the best overall performance with 43.3% efficiency improvement and 3.7% accuracy drop which outperforms the benchmark model 1.1% in overall performance.

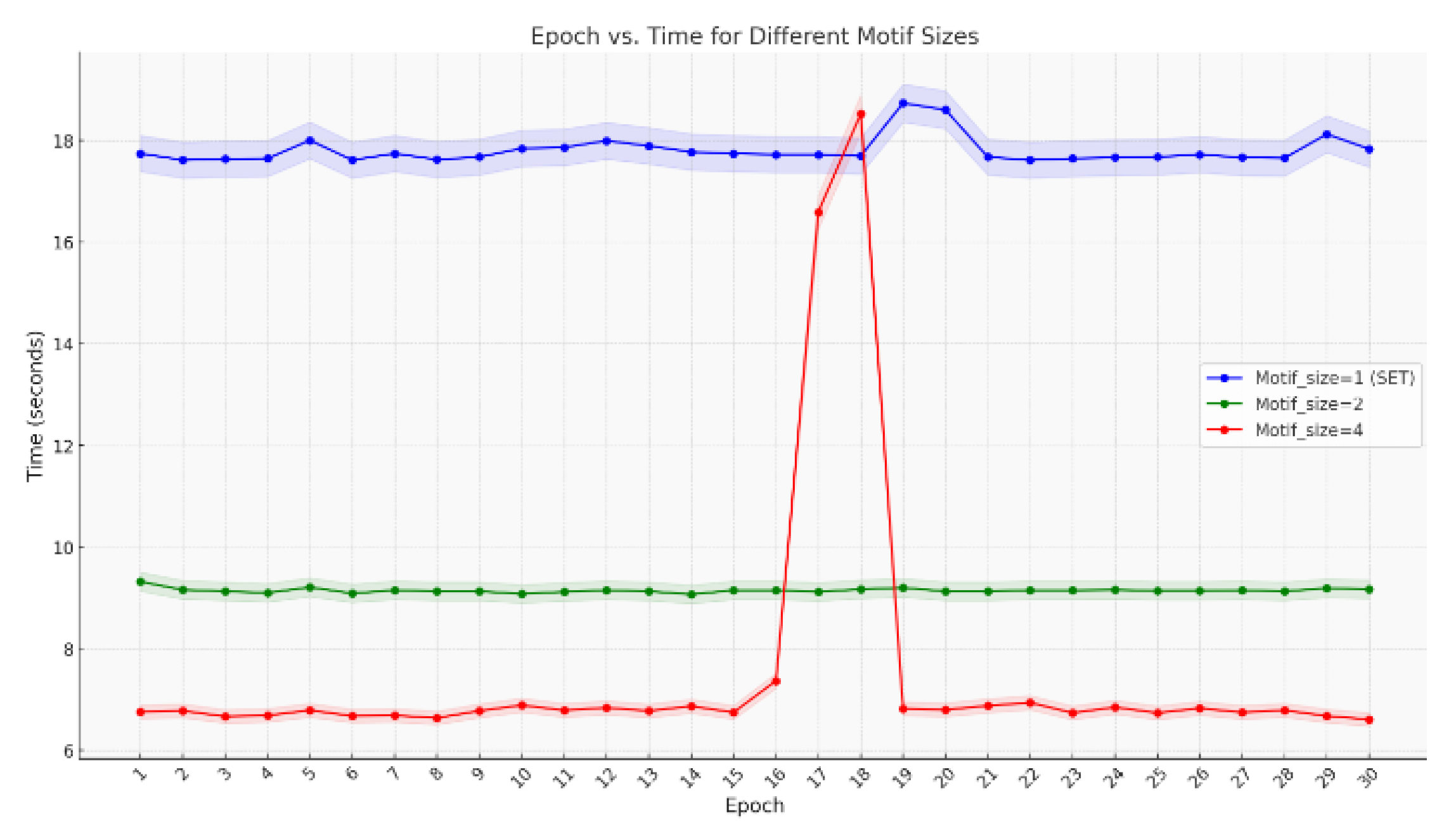

5.1.2. Result of Lung

For the Lung dataset, 300 epochs were also conducted with 3 hidden layers, each containing 3000 neurons. The results are presented in

Table 2. When the motif size is set to 1, the total running time is 4953.2 seconds with an accuracy of 0.937. When the motif size is set to 2, the total running time is 3448.7 seconds, and the accuracy is 0.926. Compared to the benchmark model, with a motif size of 2, the running time is reduced by 30.4%, and the accuracy is 1.2% lower. When the motif size is set to 4, the total running time is 3417.3 seconds, and the accuracy is 0.914. This configuration improves efficiency by 31.0% compared to the benchmark model, with a 2.5% decrease in accuracy.

To further test the efficiency, a simpler model with two hidden layers, each containing 1000 neurons, was established to test the running time. The average running time per epoch is presented in

Table 2. The running times for the first 30 epochs are recorded and displayed in

Figure 7, which corroborate the results mentioned previously. The data in

Table 2 and

Figure 6 illustrate the efficiency results for each motif size model. Both the motif size 2 and motif size 4 models demonstrate significant and comparable improvements in efficiency. However, the motif size 2 model exhibits better accuracy performance and lower standard error, indicating a more stable evolution process. Consequently, the motif size 2 model outperforms others when considering both efficiency and accuracy factors.

Figure 6.

Efficiency of Lung dataset for each motif size model

Figure 6.

Efficiency of Lung dataset for each motif size model

Figure 7.

FMNIST Efficiency Test

Figure 7.

FMNIST Efficiency Test

Table 3.

Datasets Properties

Table 3.

Datasets Properties

| Name |

Features |

Type |

Samples |

Classes |

| FMNIST |

784 |

Image |

70000 |

10 |

| Lung |

3312 |

Microarray |

203 |

5 |

From the results, it can be referred that the motif-based model has a very significant improvement in efficiency but with some accuracy loss as well. Here, the comprehensive score equation is applied to calculate the overall performance score for each motif size model:

For motif size 4:

According to the results, the model with motif size as 2 has the best overall performance. The motif-base optimized model has an improvement of 30.4% in efficiency and a drop of 2.5% percent in accuracy and this model 2.2% outperforms the benchmark model (SET) in overall performance.

From the results given above, it can be told that for both FMNIST and Lung dataset, the model with motif size as 2 has a better overall performance in both efficiency, stability and accuracy. Further analysis on the results will be given in the next section.

5.2. Result Analysis

In the process of training and testing the performance of the model, it was found that the precision of the Lung dataset is much higher than that of FMNIST in the very first phase (first 30 epochs). This is mainly due to the number of features (3312 features) in Lung being almost four times as many as the number in FMNIST (784 features). And the lung data set only has 5 output labels, FMNIST on the other hand has 10 output labels [

20].

According to the results, for both Lung and FMNIST datasets, the model with a motif size set to 2 had the best overall performance: high efficiency, high accuracy maintained and relatively stable evolution processes. It is observed that the efficiency improvement from the reference models to the models with motif size of 2 is larger than the improvement from the motif 2 models to the motif 4 models. In addition, the accuracy loss of the motif 2 model is smaller than that of the motif 4 model. However, such simple observations cannot conclude that the motif 2 model has a better overall performance than others. Therefore, a comprehensive score equation is introduced to calculate in a scientific and strict way. For any deep neural network model, the accuracy of the results is far more important than the required computation power and time. Therefore, the efficiency weight in the comprehensive score is set as 0.1 and the precision weight is set to 0.9. However, the results and analysis indicate that the overall performance of a motif-based DNNs model may differ when it comes to different types of datasets, projects and research purposes.

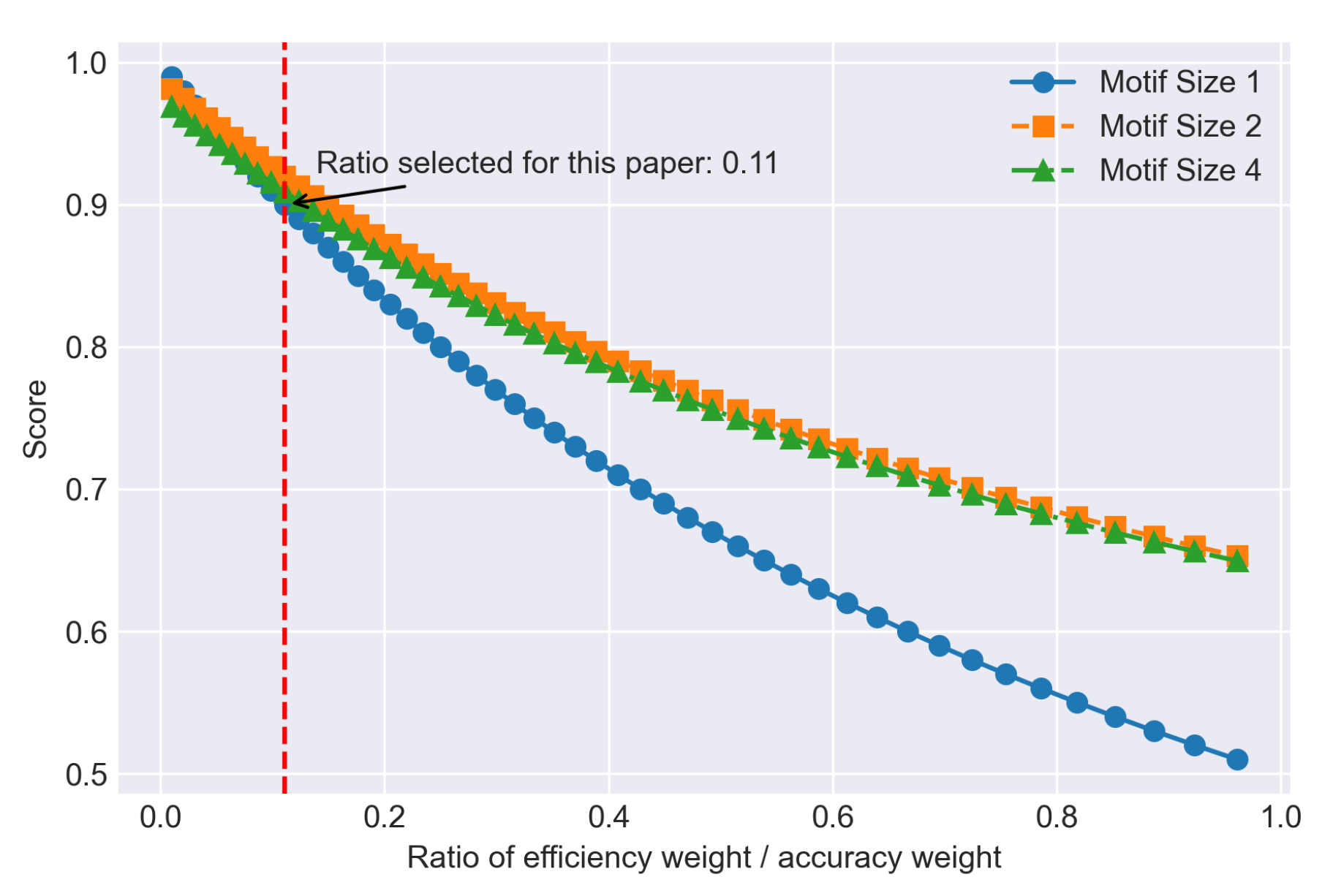

5.3. Trade-off Relationship

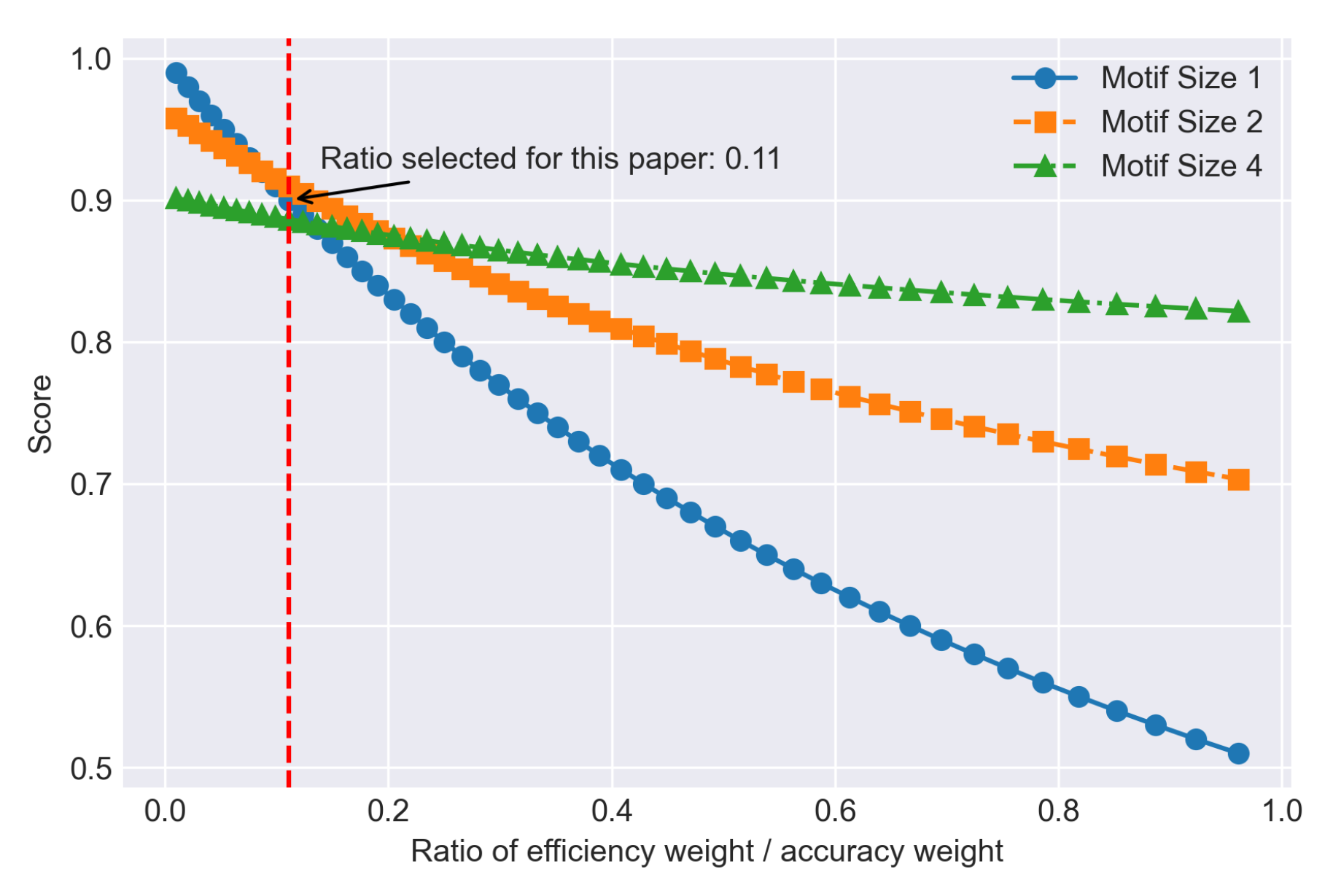

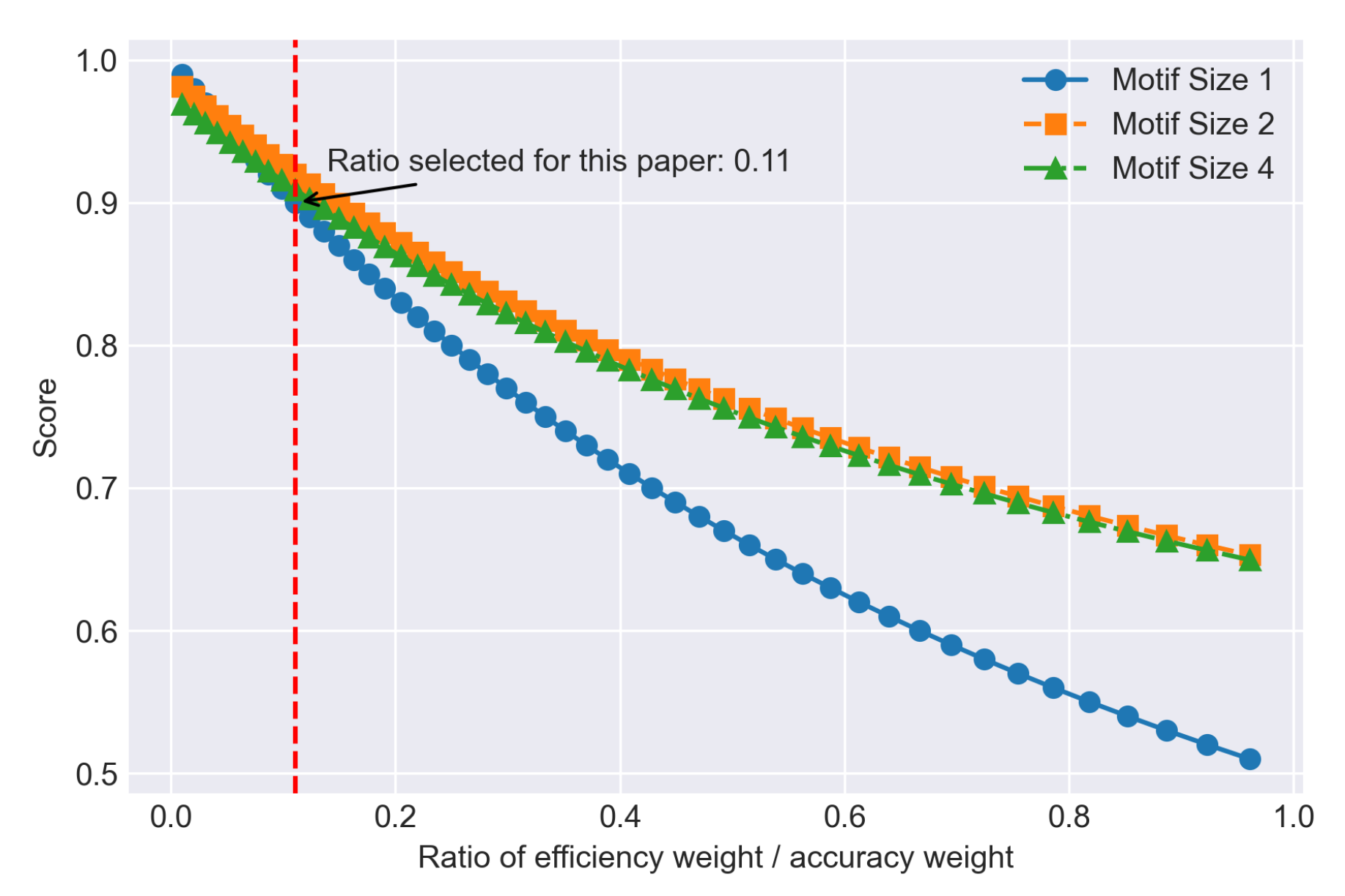

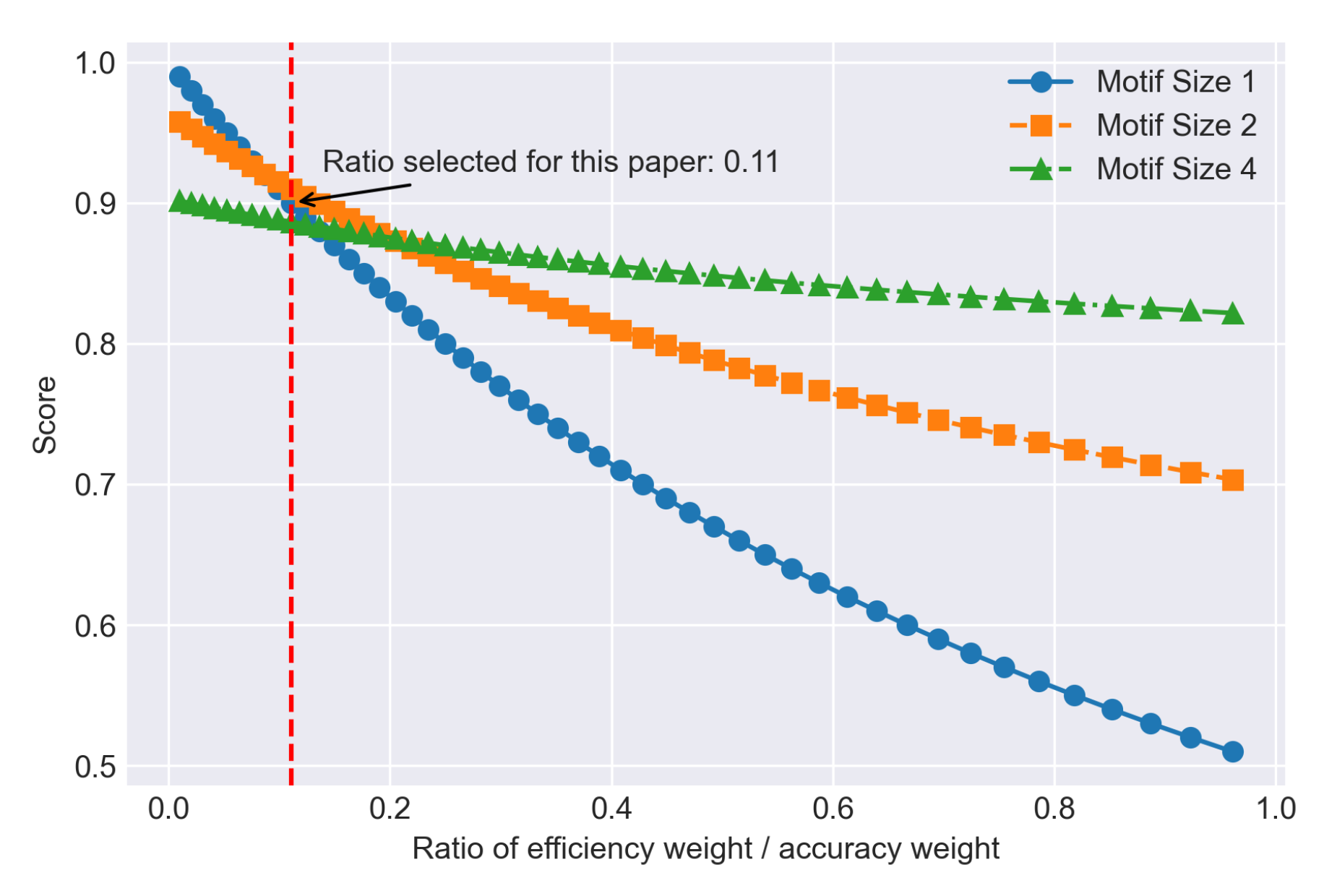

Therefore, in this section,"trade-off relationship between the efficiency-accuracy weight ratio and the comprehensive score for each motif size will be discussed.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 are plotted to better demonstrate the relationship, showing that as long as the efficiency is a factor to be considered (efficiency-accuracy weight ratio greater than 0.1), the motif-based model will outperform the regular Sparse Evolutionary Training models. In the common sense, the accuracy of a deep neural network is more important than model efficiency, however in the real life, efficiency can also be a crucial factor that determines if a DNN model is good [

10]. Balancing efficiency and accuracy is crucial in practical applications, as efficient models can provide real-time performance and resource optimization, which are essential in various scenarios such as mobile devices, real-time video analysis, and autonomous driving [

26,

27].

Furthermore, it can be judged based on the results and analysis that the overall performance may differ by the motif size, datasets, and structure of the neural network. This illustrates the significance of motif-based models when efficiency needs to be taken into consideration and the overall performance of different motif size models may vary when the purposes or scenarios of the project change.

Figure 8.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in Lung

Figure 8.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in Lung

Figure 9.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in FMNIST

Figure 9.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in FMNIST

5.4. Application Scenarios

To explore the potential applications of this algorithm, relevant scenarios will be introduced in this subsection. As mentioned above, motif-based models are well suited for scenarios that require high efficiency and immediate feedback [

28]. Based on the advantages of these models, they can be applied in the following situations:

Mobile Devices: In mobile devices, computational resources and battery life are critically limited. Motif-based models, due to their efficiency, can provide high-quality predictions without significantly consuming device resources, making them suitable for mobile applications and embedded systems [

29].

Autonomous Driving: Autonomous vehicles need to process large amounts of sensor data in a very short time to make driving decisions. Motif-based models can significantly reduce the computation time while maintaining accuracy.

Financial Trading: In high-frequency trading and financial market prediction, motif-based models can provide rapid market predictions.

Smart Home: Smart home devices must respond quickly to user commands and environmental changes. Motif-based models can efficiently process sensor data and user commands.

6. Discussion

In this paper, the concept of motif-base structural optimization is proposed. Based on SET-MLP, feature engineering benchmark model, the motif-based models were designed, tested and the one with the best performance was selected. According to the results found above, the motif-based model with feature engineering indeed has a very significant improvement in reduction of required computation cost and a noticeable drop in accuracy. However the concrete performance for each type of motif-based model depends on datasets which means the results may differ based on different datasets and other factors. Therefore, this section will also discuss these variations. Additionally, the trade-off relationship between efficiency and accuracy is a very crucial part in this project which will be discussed in detail.

6.1. Result Analysis

In the process of training and testing the performance of the model, it was found that the precision of the Lung dataset is much higher than that of FMNIST in the very first phase (first 30 epochs). This is mainly due to the number of features (3312 features) in Lung being almost four times as many as the number in FMNIST (784 features). And the Lung dataset only has 5 output labels, the FMNIST on the other hand has 10 output labels [

20].

According to the results, for both Lung and FMNIST datasets, the model with a motif size set to 2 had the best overall performance: high efficiency, high accuracy maintained and relatively stable evolution processes. It is observed that the efficiency improvement from the reference models to the models with motif size of 2 is larger than the improvement from the motif 2 models to the motif 4 models. In addition, the accuracy loss of the motif 2 model is smaller than that of the motif 4 model. However, such simple observations cannot conclude that the motif 2 model has a better overall performance than others. Therefore, a comprehensive score equation is introduced to calculate in a scientific and strict way. For any deep neural network model, the accuracy of the results is far more important than the required computation power and time. Therefore, the weight of efficiency in the comprehensive score is set as 0.1 and the weight of accuracy is set to 0.9. However, the results and analysis indicate that the overall performance of a motif-based DNNs model may differ when it comes to different types of datasets, projects and research purposes.

6.2. Trade-off Relationship

Therefore, in this section,"trade-off relationship between the efficiency-accuracy weight ratio and the comprehensive score for each motif size will be discussed.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 are plotted to better demonstrate the relationship, showing that as long as the efficiency is a factor to be considered (efficiency-accuracy weight ratio greater than 0.1), the motif-based model will outperform the regular Sparse Evolutionary Training models. In the common sense, the accuracy of a deep neural network is more important than model efficiency, however in the real life, efficiency can also be a crucial factor that determines if a DNN model is good [

10]. Balancing efficiency and accuracy is crucial in practical applications, as efficient models can provide real-time performance and resource optimization, which are essential in various scenarios such as mobile devices, real-time video analysis, and autonomous driving [

26,

27].

What is more, it can be judged based on the results and analysis that the overall performance may differ by the motif size, datasets, structure of the neural network. This illustrates the significance of motif-based models when efficiency needs to be taken into consideration and the overall performance of different motif-size models may vary when the purposes or scenarios of the project change.

Figure 10.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in Lung

Figure 10.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in Lung

Figure 11.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in FMNIST

Figure 11.

Relationship between efficiency accuracy weight ratio and Comprehensive Score for each motif size in FMNIST

6.3. Application Scenarios

To explore the potential applications of this algorithm, relevant scenarios will be introduced in this subsection. As previously mentioned, motif-based models are well-suited for scenarios that require high efficiency and immediate feedback [

28]. Based on the advantages of these models, they can be applied in the following situations:

Mobile Devices: On mobile devices, computational resources and battery life are critically constrained. Motif-based models, due to their efficiency, can provide high-quality predictions without significantly consuming device resources, making them suitable for mobile applications and embedded systems [

29].

Autonomous Driving: Autonomous vehicles need to process large amounts of sensor data in a very short time to make driving decisions. Motif-based models can significantly reduce the computation time while maintaining accuracy.

Financial Trading: In high-frequency trading and financial market prediction, motif-based models can provide rapid market predictions.

Smart Home: Smart home devices need to quickly respond to user commands and environmental changes. Motif-based models can efficiently process sensor data and users’ commands.

7. Conclusions

This paper introduced the concept of motif-based structural optimization and demonstrated its application to the SET-MLP feature engineering benchmark model. Through extensive testing, it was shown that motif-based models significantly reduce computational costs while experiencing a slight decrease in accuracy. The analysis reveals that the Lung dataset, with more features and fewer output labels, achieved higher accuracy faster compared to the FMNIST dataset.

Among all the tested models, the motif size of 2 appeared to be the most optimal choice, offering a balance between efficiency and accuracy. This balance was quantified using a comprehensive score equation, emphasizing both accuracy and efficiency . However, the trade-off between these factors depends on the specific dataset and application requirements. The motif-based approach proved advantageous when efficiency is a key consideration, outperforming traditional Sparse Evolutionary Training models in such scenarios.

In conclusion, the models with motif size as 2 have the best overall performance(with a 43.3% improvement in efficiency and 3.7% drop in accuracy for FMNIST dataset testing, 30.4% improvement in efficiency and 1.2% decrease in accuracy for Lung dataset testing ) and the motif-based structural optimization approach is highly effective for applications where computational efficiency is critical. The study highlights the need to tailor the motif size to the specific characteristics of the dataset and the intended application, ensuring an optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency.

8. Reflection and Future Work

This paper investigates the structural optimization of SET using a rather simple motif-based method. From the experiment results on 2 different datasets and 6 types of models with different motif size models, conclusions are drawn in

7 that the models with motif size as 2 have the best overall performance and motif-based models usually have better overall performances than normal SET models when efficiency is an important factor. However, it still cannot be excluded that better structural optimization strategies exist. A dynamic motif size selection mechanism during training process may help improve the overall performance. The qualitative aspect of the results is, however, likely to not change and is the reason for choosing this simple mechanism. As with any experimental study, one should analyze the behaviour on many more datasets. What is more, more datasets and scenarios should be analyzed to check if such model has enough robustness and can be applied to various datasets and scenarios Last but not least, a comprehensive score equation is given in this paper to calculate the overall performance of a model. However, there is not a specific threshold to balance the efficiency and accuracy for a machine learning model at present which is a direction for the future work of this project.

References

- Ardakani, A.; Condo, C.; Gross, W.J. Sparsely-Connected Neural Networks: Towards Efficient VLSI Implementation of Deep Neural Networks, [1611.01427 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Bellec, G.; Kappel, D.; Maass, W.; Legenstein, R. Deep Rewiring: Training very sparse deep networks, [1711.05136 [cs, stat]]. [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, D.C.; Mocanu, E.; Stone, P.; Nguyen, P.H.; Gibescu, M.; Liotta, A. Scalable training of artificial neural networks with adaptive sparse connectivity inspired by network science. 9, 2383. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yin, B.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y. Topology Aware Deep Learning for Wireless Network Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2022, 21, 9791–9805. [CrossRef]

- Altman, N.S. An Introduction to Kernel and Nearest-Neighbor Nonparametric Regression. 46, 175–185. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Van der Lee, T.; Yaman, A.; Atashgahi, Z.; Ferraro, D.; Sokar, G.; Pechenizkiy, M.; Mocanu, D.C. Topological Insights into Sparse Neural Networks, [2006.14085 [cs, stat]]. [CrossRef]

- Milo, R.; Shen-Orr, S.; Itzkovitz, S.; Kashtan, N.; Chklovskii, D.; Alon, U. Network Motifs: Simple Building Blocks of Complex Networks. 298, 824–827. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal Brain Damage. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Morgan-Kaufmann, 1989, Vol. 2.

- Hassibi, B.; Stork, D.; Wolff, G. Optimal Brain Surgeon and general network pruning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, 1993, pp. 293–299 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding, 2016. arXiv:1510.00149 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.; Wang, X. Parameter efficient training of deep convolutional neural networks by dynamic sparse reparameterization.

- Yin, Z.; Shen, Y. On the Dimensionality of Word Embedding, 2018. arXiv:1812.04224 [cs, stat], . [CrossRef]

- Bin, Z.; Zhi-chun, G.; Wen, C.; Qiang-qiang, H.; Jian-feng, H. Topology Optimization of Complex Network based on NSGA-II. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 4th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chengdu, China, 2019; pp. 1680–1685. [CrossRef]

- Hayase, T.; Karakida, R. MLP-Mixer as a Wide and Sparse MLP. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cui, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Chen, K.; Zhu, J. Neural Network Meets DCN: Traffic-driven Topology Adaptation with Deep Learning. Proceedings of the ACM on Measurement and Analysis of Computing Systems 2018, 2, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need, 2023. arXiv:1706.03762 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. 286, 509–512. [CrossRef]

- Changpinyo, S.; Sandler, M.; Zhmoginov, A. The Power of Sparsity in Convolutional Neural Networks, 2017. arXiv:1702.06257 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2009, 10, 186–198. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R. Fashion-MNIST: a Novel Image Dataset for Benchmarking Machine Learning Algorithms, 2017. arXiv:1708.07747 [cs, stat], . [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, X.; Kroening, D.; Sharp, J.; Hill, M.; Ashmore, R. Testing Deep Neural Networks, 2019. arXiv:1803.04792 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Choi, J.; Wang, K.; Jha, S. Rethinking Diversity in Deep Neural Network Testing, 2024. arXiv:2305.15698 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Sophia, J.J.; Jacob, T.P. A Comprehensive Analysis of Exploring the Efficacy of Machine Learning Algorithms in Text, Image, and Speech Analysis. Journal of Electrical Systems 2024, 20, 910–921. [CrossRef]

- Swink, M.; Talluri, S.; Pandejpong, T. Faster, better, cheaper: A study of NPD project efficiency and performance tradeoffs. Journal of Operations Management 2006, 24, 542–562. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, L. Flexibility–efficiency tradeoff and performance implications among Chinese SOEs. Journal of Business Research 2010, 63, 356–362. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Kim, K.; Pan, J.; Han, K.J.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Performance-Efficiency Trade-Offs in Unsupervised Pre-Training for Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 7667–7671. ISSN: 2379-190X, . [CrossRef]

- Atashgahi, Z.; Sokar, G.; van der Lee, T.; Mocanu, E.; Mocanu, D.C.; Veldhuis, R.; Pechenizkiy, M. Quick and Robust Feature Selection: the Strength of Energy-efficient Sparse Training for Autoencoders. [CrossRef]

- The Theano Development Team.; Al-Rfou, R.; Alain, G.; Almahairi, A.; Angermueller, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Ballas, N.; Bastien, F.; Bayer, J.; Belikov, A.; et al. Theano: A Python framework for fast computation of mathematical expressions, 2016. arXiv:1605.02688 [cs], . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Du, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lan, H.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Guo, Q.; Chen, T.; Chen, Y. Cambricon-X: An accelerator for sparse neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), 2016, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).