1. Introduction

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been established as a cause of acute anterior uveitis, usually with unilateral presentation, with possible sectoral iris atrophy, pigment dispersion, and secondary ocular hypertension [

1,

2,

3]. Its main differential diagnoses include pigment dispersion syndrome, Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, and acute bilateral or unilateral iris transillumination syndrome (BAIT/UAIT). These entities can usually be distinguished clinically with careful evaluation of medical history, laterality, iris atrophy pattern, as well as the existence or lack of inflammatory findings, this being especially stressed when discerning herpetic uveitis from BAIT/UAIT4. The latter presents similarly to herpetic uveitis, albeit almost always bilaterally, with acute onset of ocular pain, redness, and photophobia. However, it is characterized by diffuse pigment dispersion from the iris pigment epithelium (IPE), its deposition in anterior chamber structures, and the absence of keratic precipitates, anterior chamber inflammatory cells, or vitritis [

4,

5,

6]. While the etiopathogenesis of BAIT/UAIT is still not fully understood, it has been attributed to toxic effect of systemic or local antibiotic therapy, most commonly fluoroquinolones, on IPE [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Given the existence of antecedent viral infections in two thirds of these patients, viral etiology has also been suggested to play a role [

5,

12].

We report a case of acute anterior uveitis due to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), developing clinically from a typical herpetic uveitis into an acute iris transillumination-like syndrome with pigmentary glaucoma necessitating cataract surgery, vitrectomy, and glaucoma filtration surgery.

2. Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with redness, pain and blurred vision in her left eye. Her ocular history included amblyopia in the right eye, and LASIK performed for high myopia 12 years prior on the left eye. Her systemic history included Hashimoto thyroiditis, an episode of pericarditis 4 years prior, and an episode of viral pneumonia 2 years prior. She was otherwise healthy, took no antibiotics or other medications, had no recent vaccinations, and experienced no other symptoms or a viral prodrome. At the time of the initial evaluation, her best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was hand motion (HM) in the right, amblyopic eye, and 20/40 in the left eye. Her intraocular pressure (IOP) measured 12 mmHg in the right eye and 14 mmHg in the left eye on Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT). Her left eye was documented (only textually, no available photodocumentation) to show ciliary injection, fine keratic precipitates, and anterior chamber cells, with normal pupils and no other pathological findings except for a mild nuclear cataract. No signs of vitritis were noted, and dilated fundus exam showed slightly tilted optic disc with myopic fundus tessellation but was otherwise normal. The right eye showed no signs of inflammation or any other pathological finding aside from a dense nuclear cataract, fundus tessellation, and a slightly tilted optic disc.

The general ophthalmologist who saw the patient applied a subconjunctival dexamethasone injection and prescribed treatment with dexamethasone drops and ointment, tropicamide drops, and oral ibuprofen. Over the course of one month, the patient reported almost complete resolution of symptoms, her left eye BCVA improved to 20/25, and signs of inflammation regressed, with few keratic precipitates and no cells in the anterior chamber. The treatment was tapered and subsequently discontinued. However, within a couple of days since treatment cessation, the patient returned complaining of blurred vision once again. Her left eye BCVA was now 20/50, and slit lamp examination revealed diffuse pigmented precipitates on the corneal endothelium and the anterior iris surface, an abundant convection current of dispersed pigment in the anterior chamber, as well as dense pigment deposition on the anterior hyaloid membrane and posterior lens capsule in the visual axis and temporally (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Additionally, the IOP of the left eye was now elevated and measured 31 mmHg. No corneal infiltration or non-pigmented keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells, vitritis, or posterior synaechiae were noted. The patient was given another subconjunctival dexamethasone injection, restarted on topical dexamethasone and tropicamide, with added dorzolamide/timolol drops, and referred to a uveitis specialist.

Upon referral, a mid-dilated, irregular pupil with poor light reaction was additionally noted, with the iris showing pronounced sectoral transillumination defects in the upper temporal quadrant (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). A working diagnosis of UAIT syndrome seemed possible for the abundance of pigment dispersion and a current lack of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber or vitritis. However, given the likely differential diagnosis of herpetic uveitis, especially due to previously described findings and a good response to dexamethasone treatment, as well as a typical finding of sectoral iris transillumination and stellate morphology of pigmented corneal precipitates, the patient was started on oral acyclovir (5 x 800 mg daily) with continued topical therapy and dexamethasone injections. Anterior chamber tap for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to test for Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 and 2, Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), returning positive for HSV-1.

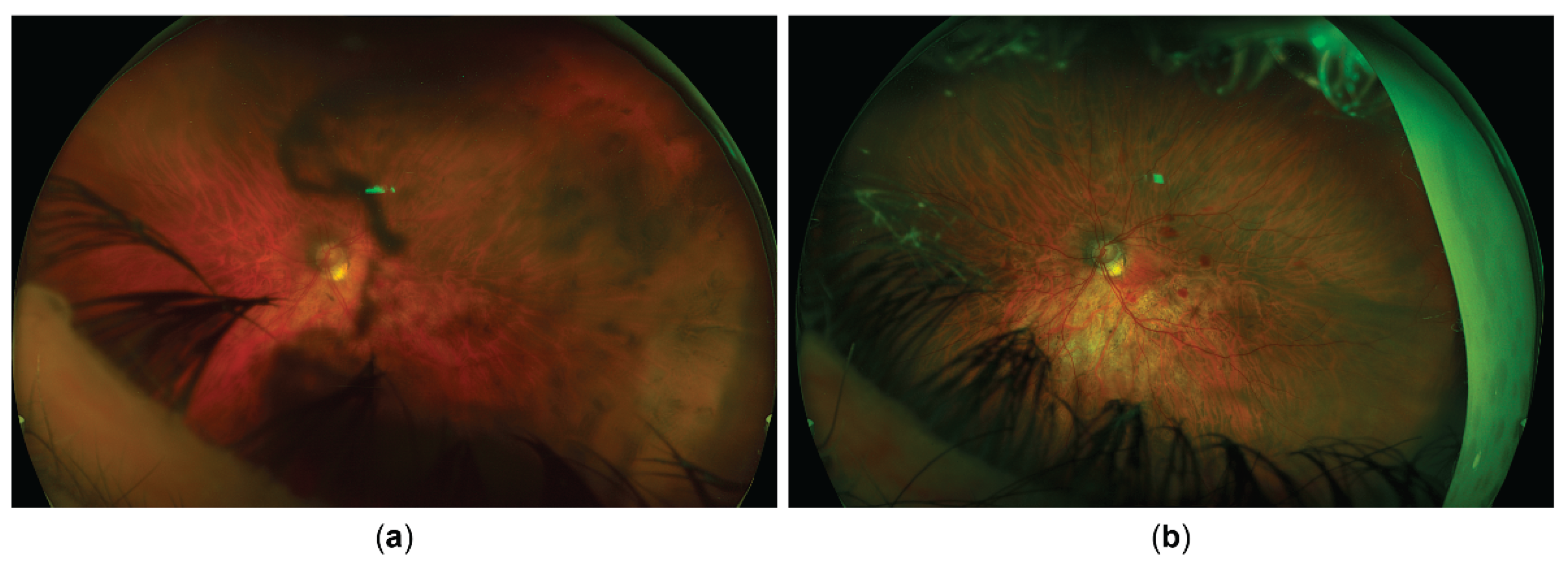

Despite the treatment, and despite continuous lack of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber or vitreous, BCVA further deteriorated to 20/400 due to retrolental pigment deposition. The transillumination defects progressed to encompass the entire iris, and gonioscopy showed an open angle with circumferential dense pigmentation obscuring all structures (

Figure 3). Intraocular pressure mounted, prompting the addition of brimonidine and bimatoprost drops with oral acetazolamide, which maintained IOP variably between 14 and 28 mmHg as measured by GAT. However, discrete retinal arterial pulsations could occasionally be seen at the optic disc of the left eye, indicating an even higher IOP than measured, keeping in mind post-LASIK issues in IOP measurement [

13,

14].

The patient underwent a combined cataract phacoemulsification surgery with pars plana vitrectomy to remove the pigment obstructing the visual axis. Despite unremarkable surgical course, on postoperative day one, the eye was hypotonic with multiple choroidal detachments and several intraretinal hemorrhages. The choroidal detachments, intraretinal hemorrhages, and hypotony resolved within several days, with BCVA rising to 20/125, and with IOP rising again and prompting the continuation of previous IOP-lowering therapy. The IOP measurements continued varying between 16 and 30 mmHg, and as the exact measurement of IOP was compromised due to post-LASIK status of the eye, further clinical decisions were aided by digital tonometry and observing the status of the optic disc via fundoscopy and OCT. As thinning of neuroretinal rim and retinal nerve fiber layer was noted, and as signs of corneal decompensation with epithelial edema developed (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), reducing BCVA to CF, the patient underwent Ahmed glaucoma valve implant. Postoperatively, IOP values reduced to measurements between 6 and 13 mmHg, with partial resolution of corneal edema, and BCVA improvement to 20/400.

3. Discussion

Herpetic uveitis can lead to significant pigment dispersion and iris transillumination defects, especially in cases with systemic immunosuppression, when even bilateral presentation is possible [

3]. In such cases, the distinction between herpetic uveitis and acute iris depigmentation syndrome can become problematic by means of clinical signs alone, and indicative medical history is instrumental. So far, as we know it, only a few acute iris transillumination-like cases have been described with confirmed HSV association15,16. This contrasts with the vast majority of BAIT/UAIT cases, which seem to have a distinct etiopathogenesis, primarily implicating a toxic effect of fluoroquinolones or other drugs on iris pigment epithelium [

7]. And although viral etiology, including herpes viral infection, has also been suggested to play a role in BAIT/UAIT, conclusive evidence is lacking, with anterior chamber PCR for herpes virus family being negative in almost all published cases [

4,

5,

6,

12,

15]. A conclusion could be drawn that cases with confirmed HSV association could be misinterpreted as (within the scope of) iris transillumination syndrome due to having not been seen in the inflammatory phase, as in the case described by Gonzalez Martinez et al. [

16], or due to significant discrepancy between the amount of iris epithelial pigment dispersion and signs of inflammation, as in the case reported by Dastrup et al. [

17]. This is reinforced by the reported history, although non descriptive, of precedent acute iritis in the former case, and by the finding of keratic precipitates in the latter. Both studies acknowledge the herpetic etiology as uncommon for this syndrome. However, given the suggested role of viral infections in the BAIT/UAIT, the studies imply the possible existence of a common pathway for virally mediated iris pigment loss. Our case also illustrates such a possibility through a well-documented shift from a clinical picture typical of herpetic uveitis to one suggestive of UAIT. However, while the apparent lack of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber or vitritis in the latter phase could have been taken as an indication of this alternative diagnosis, it seems more likely steroid treatment had masked the clinical findings and simply blurred the lines between two separate entities.

Regardless, the unabated progression of IPE atrophy and pigment dispersion during the phase with no visible inflammation suggests a distinct pathophysiological process either unrelated to general inflammatory activity, such as direct viral cytopathic effect, or related to its inappropriate modulation. This opens the question of possible iatrogenic exacerbation of such processes. As already mentioned, herpetic uveitis in systemic immunosuppression can manifest bilaterally and with more severe sequelae, as steroid treatment without adequate antiviral treatment can reduce the host's ability to control viral replication, potentially worsening cytopathic damage [

3]. It is of interest to note that manifestations of ocular herpetic disease such as retinal necrosis or iris atrophy are supposed to result from a combination of direct viral cytopathic effect on multiple cell types, including endothelial cells, and intense immune-mediated inflammation leading to occlusive vasculitis [

18,

19]. Although our patient was treated only with topical and subconjunctival steroids, and was otherwise immunocompetent, these were at first used without appropriate antiviral treatment, which may have led to uncontrolled viral replication and a delayed exacerbation mimicking UAIT due to acute ischemic damage and necrosis of IPE. Unfortunately, we opted not to take any intraoperative iris sample for histological analysis. In the study of Gonzalez Martinez et al., the histology of the enucleated eye showed pronounced absence of IPE and iris dilator muscle, with extensive necrosis and focal vascular occlusion of iris sphincter muscle, but no evidence of active vasculitis or nuclear viral cytopathic changes typical of herpes virus infection [

16]. Also, the inflammatory infiltrate in the uveal tract was extremely mild and predominantly lymphocytic. The authors mentioned possible limitations due to sampling, and possible modification of histological findings due to topical steroids administered to the patient. We should stress that their patient presented in the late, quiet phase, several months after the initial iritis phase (n.b. also treated with topical steroids and no antivirals), which very likely influenced any histological findings.

4. Conclusions

Both our case and the previously mentioned cases highlight the unusual unilateral acute iris transillumination-like presentation of HSV-1 uveitis. However, this only implies a pathway for HSV-1 mediated iris pigment loss, which potentially could be shared with other viruses, but this remains theoretical. Also, current clinical evidence for acute iris transillumination syndrome favors an alternative, toxic mechanism as the likely cause of IPE damage, discerning it from the one postulated for HSV-1 related IPE loss. This would allow us only to use the moniker of acute iris transillumination-like in cases like these, and to clearly discern these entities. When clinical signs alone are not distinctive enough, aqueous tap and PCR testing for herpes viruses offers additional support. However, as it can yield false negatives, it should be viewed as confirmatory rather than excluding, and indicative medical history should remain instrumental. More importantly, the possibility of complications such as the ones described here arising from using steroid treatment alone or with delayed antiviral treatment should be considered, and it may be prudent to apply a low threshold for immediate introduction of antiviral treatment in any case of uveitis unattributed to other clear causes, especially if clinical signs are consistent with possible herpetic etiology. Additionally, testing for antiviral resistance should be made readily available in complicated and unresponsive cases, so antiviral treatment can be timely adjusted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, G.M., A.V., M.Z.G., Z.V.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, M.Z.G., Z.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No institutional review board statement was required.

Informed Consent Statement

A written consent to publish the case report was obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the report are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Liesegang, T. J. Herpes Simplex Virus Epidemiology and Ocular Importance. Cornea. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Chan, N. S. W.; Chee, S. P. Demystifying Viral Anterior Uveitis: A Review. Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2019. [CrossRef]

- de-la-Torre, A.; Valdes-Camacho, J.; Foster, C. S. Bilateral Herpes Simplex Uveitis: Review of the Literature and Own Reports. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 25 (4). [CrossRef]

- Tugal-Tutkun, I. Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129 (10), 1312. [CrossRef]

- Tuğal-Tutkun, İ.; Altan, Ç. Bilateral Acute Depigmentation of Iris (BADI) and Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination (BAIT)-An Update. Turkish J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 52 (5). [CrossRef]

- Perone, J. M.; Chaussard, D.; Hayek, G. Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination (BAIT) Syndrome: Literature Review. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tranos, P.; Lokovitis, E.; Masselos, S.; Kozeis, N.; Triantafylla, M.; Markomichelakis, N. Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination Following Systemic Administration of Antibiotics. Eye 2018, 32 (7). [CrossRef]

- Gonul, S.; Eker, S. Unilateral Acute Iris Transillumination Syndrome Following Uneventful Phacoemulsification Surgery with Intracameral Moxifloxacin. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30 (7–8). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, C.; Puerto, B.; López-Caballero, C.; Contreras, I. Unilateral Acute Iris Depigmentation and Transillumination after Glaucoma Surgery with Mitomycin Application and Intracameral Moxifloxacin: Acute Iris Depigmentation after Intracameral Moxifloxacin. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Reports 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- Zubicoa, A.; Echeverria-Palacios, M.; Mozo Cuadrado, M.; Compains Silva, E. Unilateral Acute Iris Transillumination like Syndrome Following Intracameral Moxifloxacin Injection. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Kawali, A. A.; Dakappa, S. S.; Mahendradas, P.; Kurian, M.; Kharbanda, V.; Shetty, R.; Gangi Setty, S. R. Aqueous Humor Tyrosinase Activity Is Indicative of Iris Melanocyte Toxicity. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 162. [CrossRef]

- Kawali, A.; Mahendradas, P.; Shetty, R. Acute Depigmentation of the Iris: A Retrospective Analysis of 22 Cases. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54 (1). [CrossRef]

- Berrett, G. B.; Hogg, J.; Innes, W. Retinal Arterial Pulsation as an Indicator of Raised Intraocular Pressure. SAGE Open Med. Case Reports 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Helmy, H.; Hashem, O. Intraocular Pressure Calculation in Myopic Patients after Laser-Assisted in Situ Keratomileusis. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Altan, C.; Basarir, B.; Bayraktar, S.; Tugal-Tutkun, I. Bilateral Acute Depigmentation of Iris (BADI) and Bilateral Acute Iris Transillumination (BAIT)Following Acute COVID-19 Infection. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2023, 31 (6). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Martinez, O. G.; Shields, C. L.; Shields, J. A.; Chévez-Barrios, P.; Walley, D. R.; Eagle, R. C.; Milman, T. Unilateral Acute Iris Transillumination Syndrome with Glaucoma and Iris Pigment Epithelium Dispersion Simulating Iris Melanoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Reports 2023, 32. [CrossRef]

- Dastrup, B. T.; Cantor, L.; Moorthy, R. S.; Vasconcelos-Santos, D.; Rao, N. An Unusual Manifestation of Herpes Simplex Virus-Associated Acute Iris Depigmentation and Pigmentary Glaucoma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Viejo-Borbolla, A. Pathogenesis and Virulence of Herpes Simplex Virus. Virulence 2021, 12 (1). [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Spencer, D. B.; Mochizuki, M. Therapy for Acute Retinal Necrosis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2008, 23 (4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).