1. Introduction

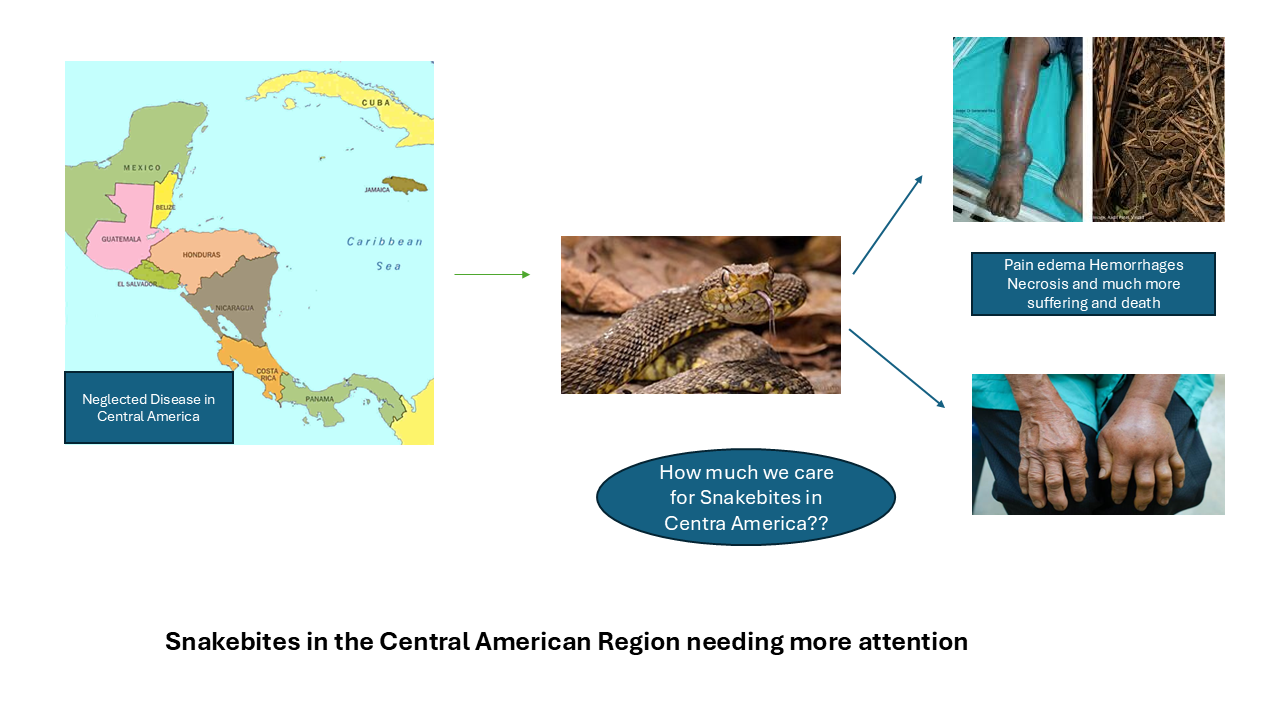

Snakebites were recently included as part of the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) to be addressed as a priority by the Sustainable Development Goals. The delay incorporating Snakebites as a priority for Public Health Initiative is not because of an emerging importance; it has been around because of the overlapping of humans and snake habitats caused by activities such as agriculture, pasturing and livestock farming in different parts of the world. Commercial farming has open vast areas of land in tropical and subtropical regions for human activity and unplanned encounters of humans and snakes (venomous and non-venomous) occur because of this. Consequentially accidental bites can occur causing disease, death and disability. [

1,

2]

According to recent Global estimates there are around 63,400 cases of snakebites per year. The greater proportion of venomous snakebites is reported in South-Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa and represent an important part of their healthcare demand. Areas in the Americas and Australia are also affected by snakes with different levels of Institutional response [

2,

3,

4] which is reflected in the surveillance of this program, the management of cases and mortality. The global estimates include information for Central American countries (see

Table 1)

According To Harrison (2009) people dedicated to farming activities and extraction of silviculture products have an increased risk to enter in contact with poisonous snakes since their hands, feet and legs get in contact with areas where the snake lives or moves in forested areas. [

5]

Central America is a narrow strip of land between North America and South America, with access to the Caribbean and the Pacific coasts, In Central America , variation in climate conditions leads to the presence of different venomous snakes species causing different clinical manifestations (depending on the different components of their venoms) [

6]

According to Gutierrez (2016) a large proportion of venomous snakebites are caused by Bothrops asper in Central America. Envenoming caused by this species has been better documented in Costa Rica but information from other Central American countries is available but less complete [

6,

7].

Crotalus simus is also reported as one of the main venomous snakes in inland and dry forest areas, and Coral snakes of the genus Micrurus (family Elapidae) are more relevant as cause of these ophidian accidents along the Pacific coast and reported as associated to 1% of the snakebites. [

6,

8,

9]

Particular issues to consider about Snakebites in Central America

1.1. Occupational Risk for Snakebites (Ophidian Accidents) in Central America

A large proportion of the venomous snakebites in Central America are associated with agricultural activities and can be considered under the scope of occupational risk and the affected population having an increased vulnerability to this condition and its complications [

10]

Morbidity/ Mortality caused by Snakebites in Central America is attributed to snake-species grouped in two families: Viperidae and Elapidae. According to the recorded clinical information this reflect a fraction of the real cases due to under-recording of cases.

The lack of information and under-reporting corresponds to the lack of information of the population of the snake populations and the traumatic experience associated to the encounter with these reptiles. [

11,

12]

1.2. Clinical Manifestations of Snakebites Caused by the Frequent Viperidae and Elapidae Species in Central America

The clinical manifestations associated to each type of snakebite can include some different symptomatology, the most frequently mentioned belong to the Viperidae family. Documented symptoms for this type of envenoming are among the most common manifestations.

1.3. Viperidae Species

Bothrops asper is the main representative of this family in Central America. The envenoming caused by

B. asper is able to cause damage in several organic systems and those described as more relevant are at local level. Cytotoxic effects cause extensive tissular destruction in the area around the primary bite compromising cutaneous, subcutaneous and muscular tissue [

13,

14].

Regarding the muscle damage, frequent outcome of such local pathology skeletal muscle regeneration deficiencies, which cause muscle dysfunction, muscle loss and fibrosis .In the long term this results in varied levels of disability [

15]. The deficient regeneration of the muscle remains a matter of research and one of the hypotheses is that Snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMP) -induced basement membrane damage, in micro vessels, muscle fibers and nerves, is the main culprit for the poor regenerative outcome [

15,

16]. At the systemic level the cardiovascular system is the most affected

Crotalus simus. Venoms from adult specimens of C. simus from Costa Rica present high proteolytic, hemorrhagic, and edematogenic activity and are devoid of neurotoxic activity. Local symptoms may be severe, with pain, massive swelling, blistering, and necrosis. [

13,

17]

Systemic effects are relatively mild or moderate involving hemostatic disturbances (hypofibrinogenemia), spontaneous systemic bleeding, renal failure and neurotoxicity may occur but are less frequent. [

18,

19]

Elapidae species

The envenoming by local Elapidae species like those in the genus Micrurus present neurotoxic manifestations provoked by a neuromuscular blockage predominantly induced by post-synaptic acting low-molecular-mass neurotoxins as mentioned by Gutierrez, some of these clinical features include initially mild pain, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. As the venom spreads, more severe symptoms can appear, such as muscle weakness, paralysis (descending paralysis with bulbar findings appearing first., difficulty breathing, and neurological issues like slurred speech and drowsiness.[

20,

21]

Treatment of snakebites

The health systems in Central America use antivenoms produced in laboratories using a mixture of the venoms of the most common venomous snakes in the Region. The laboratory in charge of the production in Central America is in Costa Rica which uses venoms of local snake species (to make them more specifics to the chemical structure, producing a more complete neutralizations of the toxin effects). Some antivenoms are imported from Mexico, Argentina and other laboratories in South America which can be effective attenuating the toxin effects as well. Each country assign antivenom supply to hospitals of secondary and tertiary level (located in main cities) where the product can be kept under low temperature (cold chain) but sometimes a few hours from the critical spots (in rural and distant areas) where most of the snakebites occur which represent an obstacle for its opportune use and reduces its impact on the toxin effects . As a shared problem due to its cost and cold-chain requirements, many countries do not have enough antivenom for their at-risk population. [

22]

The most distant communities recur to the use of natural products (derived from plants and animal structures) known for some effect on some symptoms basically pain and inflammatory reactions but with less tested effect on other clinical manifestations such as alterations on coagulation, hemorrhages, effects on distant organs, and in the case of elapid toxins (in Coral snakes) on neurological symptoms (peripheral and central). There are recent efforts to study scientifically the effect of some active principles of plants in the venom’s effects. In Central America there has been a particular interest in identifying ethnomedicine products with effect on the hemorrhagic effects of Bothrops asper giving his role in envenoming, however the results has been very limited [

23]

It's important to get a sense of how much findings and studies on this area coincide across countries and regions and to identify gaps in knowledge that need to be solved.

2. Methods

The question to be answered is What are the main epidemiological features of the Snakebites in the countries of Central America and the time between the ophidian accident and the initial health care by the institutional system?

A review of recent publications on Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of snakebites published on Central America snakebites was conducted to identify common species of venomous snakes, and the symptomatology reported in the cases and the demographics of the population affected by the event.

Different databases were reviewed including PUBMED, Scielos and Lilacs. Studies published in English and Spanish were included. Given the limited number of publication on the Region we included publication since 1950 to the current years and publications retrieved from University Journal in the Region where available

Retrospective studies, case reports and case series from countries in Central America including Panama were included, and the objective was to identify the common symptoms and correspondence to the snakes species and their main toxins. Further the casuistic data gathered by researchers in the different countries including the demographics, symptomatology and outcomes are described.

3. Results

During the search we found that authors describing the situation of the snakebites in the different countries refer to similar information about the demographics of the victims of this accidental event, there is not scientific confirmation of the species causing the envenoming but a self-report of the common names for the snake and frequently that information is also absent. The symptoms are described in a similar way across different country studies, and some identify patterns of ophidian accident and responsible species according to ecological and climactic areas

3.1. Belize

We didn’t find specific publications referring to Snakebites in the Belize, and the government don’t issue information on this topic. However, there are educational materials for military personnel about the type of venomous snakes including Bothrops species, different crotalids’ and Elapidae snakes.

In the press they mentioned an attack by an unidentified snake to a 14 year boy, with a bite to the leg and causing local effects. He was treated in a nearby clinic without any further complications beyond local symptoms like edema, reddening and the local lesion on the patient leg.[

24]. Estimates have been calculated by GBD and are included in

Table 1.

3.2. Guatemala

Six different publications were identified for Guatemala. Wellman (2020) did a review of different studies done in Guatemala finding that venomous snakebites were reported as causing a series of hemorrhagic manifestations and coagulopathies with additional manifestation of compartmental syndrome, renal failure and Shock. Those patients who died (a subsample of 7) had reports in the necropsy including the clinical findings: cerebral hemorrhages, renal necrosis and hepatic cirrhosis). Several inconvenient occurred in the studies when trying to identify the responsible species for the snakebite but those identifies included basically 4 species: B. asper, A. Bilineatus bihaentis, Porthidium ophiomegas and C. durissus [25,26.27]

Letona(2012) mentioned

B. asper, C.simus, M. nigrocinctus and A. mexicanus snakes as responsible of ophidian accident in Guatemala.. Medical reports included 7377 snakebites from 2001 to 2010 most of them from locations in the lowland of Guatemala.

Bothrops asper was the main responsible for most snakebites in Northern Guatemala (in the Caribbean basin) while

Crotalus simus was more frequent in the Southern part (Pacific basin). Envenoming caused by snakes of the genre

Micrurus were few and 2 were reported in 2017 [

28]

The victims of snakebites described by Letona were found with more frequency in the age range of 10-19 yeas, most of them males living in rural areas and dedicated to farming activities, but some suffered the bite at home or close to it. Women suffered a lower number of bites doing domestic work, collecting lumber and getting water for their family needs.[

28]

A different study conducted by Guerra Centeno (2016) analyzed 305 clinical charts in two regional hospitals of Guatemala of Ophidian accidents during the years 2008-2013, one serving population of the central and Southern provinces of Guatemala (Hospital Escuintla) and the other hospital and San Benito in Peten serving patients of the North and central part of Guatemala. 187 patients were male (61.3% of the total) and dedicated to agricultural activities., 32% of the victims were farming while they experienced the event, 27.8 were at home, and a smaller proportion suffered the event while walking on the road or paths between home and agricultural fields. The events were reported as occurring. with similar frequency during daytime and nighttime. The mean age of victims was 25.2. The lower limbs were bitten with more frequency.[

29]

The mean time to reach the hospital after the event was 5.6 hours and the author find it related to the difficult transportation, remote location of occurrence, economic factors (no money to start mobilizing to the hospital) and the stops to look for assistance by traditional healers and natural medicine people.

There was a difference in the species identified as responsible of the events. In the Northern Hospital

Bothrops asper was the most frequent one (88.5% of the cases were related to this species) while in the Southern Hospital (Escuintla) tat species has less importance and it was related to only to 13.3 % of cases while Crotalus simus was responsible for 28.8 % of cases, Agkistrodon bilineatus was responsible for 37.5% of the snakebites, coral snakes (Micrurus sp) was present in 13.3% of the cases.[

29]

The epidemiology of the snakebites in Guatemala seems to correspond to descriptions given by authors in other countries in the Central American region. Similar human and institutional characteristics can be an explanation to those similarities [

22,

30]

3.3. Honduras

In Honduras there are reports of snakebites caused by the most common species and there are some few case reports reflecting the natural history of snakebites after 24 hours. The studies were conducted through the review of clinical charts in 6 hospitals, four of them of local and regional coverage, two of them with National coverage

A total of 14 studies were identified, three of them in pediatric population and the rest in general population. Those with a pediatric population had as a median age of of 11 years, and those in general population had a mean of 18 years.. A common pattern in the studies were the hemorrhagic symptoms (in seven hospitals), followed by pain and edema, and neurological manifestations in one. There were more males than females in those patients exposed to snakebites [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]

Those hospitals in the northern regions had more reports of ophidian accidents caused by

Bothrops asper, while in the rest of the country cases were distributed among other Bothrops species, Crotalus simus and other crotaline species, less than 5% of cases had a record of encounters with coral snakes (Micrurus sp). [

31,

32]

As described in studies done in the other Central American countries the victims of snakebites were coming from rural locations and dedicated to farming, or domestic activities or students walking rural roads and paths [

30]. One of the inconveniences for the opportune attention in the hospital was the time they required to get there. Two studies marked a range from 3-5 hours and two more provided a media of 5.4 hrs [

22,

30].

A case reported an envenoming after a Bothrops asper bite and the most relevant manifestations included headache, dizziness, weakness, epistaxis and paresthesia, distal coldness, prolonged 5-second capillary filling and dry mucous membranes, patient evolving after the second day to tachycardia, tachypnea dyspnea, pleural effusion and hemothorax. The patient improved his condition after treatment with antivenom (34,].

Patients described in the different studies tended to be younger, male and rural dwellers usually farmers who suffered bites in the limbs especially the lower ones, with symptomatology of haemato-toxicity [

35,

36]

In Honduras in a hospital located in the central dry valley of Comayagua were more reports of snakebites caused by

Crotalus simus, Micrurus sp and

Bothrops nasutus and

Bothriechis marchi and a small number by

Bothrops asper reported in the Hospital Sta Teresa [

32]

An author in agricultural topics mentioned that in the western part of Honduras

Crotalus simus and Bothrops aspermore frequently are identified as the most common causes of Snakebites and he emphasizes that the envenoming is a concern in the human and veterinary health. Since the study was done in the community in extra-hospital settings, the mortality of farmers in three(3) during the year of study (2011) and those dedicated to work with livestock were also affected [

37]

3.4. El Salvador

El Salvador is a country located in the dry Pacific Corridor of Central America where the Bothrops asper is not found but the importance as main cause of snakebites envenoming is attributed to Crotalus simus, while there are other snakes with a secondary role in these events. As an important information, El Salvador has its territory as part of the Pacific basin with no humid forest.[

38]

According to statistics kept by the Ministry of Health in El Salvador 1130 snakebites were reported in the SIMMOW (National System of information on Morbidity and Mortality) _for the period 2014–2019, with a mean of 188.3 cases per year, and a range of 161 cases (2017) to 215 cases. Snakebites are a obligatory notifiable event and its reported regularly. [

39]

A different study using data from the Epidemiological Surveillance System was conducted by Chirino-Molina (2025), she used information from 2011 to 2022 , and included “all people of any age and sex bitten by a poisonous snake and presenting a clinical condition of progressive edema around the area of the bite, dizziness, hypotension (mild to severe), with or without any of the following symptoms: hemorrhages, paresthesia, necrosis in the bitten area, ptosis (mono or bi-palpebral).

The study included 1503 records and after excluding duplicates and files of foreign patients, the final total was 1472 records. Demographic information was included in a new Microsoft excell 2019 and a key variable: time between the event (bite) and clinical attention was included.[

40]

A total of 61% of the patients were male and 83.2% from rural locations. Patients included ages from 1-98 years with a median of 28 years for males and 27 for female. It seems the age of patients is older than in other countries.

Greater frequency of events occur from May to September which correspond to the rainiest season in El Salvador

This study identified as the responsible species for the snakebites the following families: Elapidae and Viperidae, from previous studies they reported

Crotalus simus and other species such as

Parthenium ophriomegas, Cerrophidion wilsoni and Micrurus nigrocinctus [

40]

Gutierrez (2020) described that in the period 2014- 2019, the official records included 4 deaths for a case fatality rate of 0.44 % ; incidence of snakebites and mortality because of it were considered the lowest in the region.[

38]

3.5. Costa Rica

Costa Rica identifies Bothrops asper as the main cause of snakebites in that country affecting young adults and causing local effects and hemorrhagic manifestations, edemas, hypotension and other systemic disorders (cardiovascular shock, acute renal failure).

B. asper has been associated to wet lowland regions in Costa Rica as well as in countries with similar ecological characteristics. Previous studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of this Neglected disease in the last years of the twentieth century and first years of the current century. From 1993 -2006 there were 48 fatalities due to snakebites. Mortality rates ranged from 0.02 per 100,000 population in 2006 to 0.19 per 100,000 population in 1993. The most affected age groups were those of 20-29, 40-49 and 50-59 years, and fatal cases predominated in males over females by a ratio of 5:1. [

41]

A recent study completed by Sasa and Segura (2020) in 6 hospitals reviewed the charts of a total of 475 victims of snakebites attended in the selected hospitals of the country in 2012 and 2013.The incidence rate for the country during the two studied years was 9.44 and 10.76 per 100,000 inhabitants per year and the incidence of the snakebite differs between months (χ2 ¼ 30.93, df ¼ 11, P < 0.001), showing a peak between May–July and another in October–November . this study showed an association to agricultural activities, much less to recreational activities, but accidents could occur in peri domiciliary spaces as well [

42]

Historically Costa Rica has prioritized better snakebites management and at the same time the development of the antivenom production and the raise of public awareness of this Ophidian accident in the regions of the country[

43]

3.6. Panama

Jutzy et al (1953) reported in Panama a series of 23 patients who suffered snakebites caused by

Bothrops spp and in seven cases the outcome was fatal with shock and hemorrhages of the Central Nervous system [

44]

Panama was considered the country with highest incidence of snakebites in a Velez paper (2017), the authors identifying characteristics of the venoms in 4 regions, with a profile of lethal, hemorrhagic, in vitro coagulant, defibrinogenating, edema-forming, myotoxic and indirect hemolytic activities, with subtle quantitative variations between samples of some regions [

45,

46]

Human accidents by B. asper are characterized by prominent local tissue damage, i.e. edema, myonecrosis, dermonecrosis, blistering, and hemorrhage, and by systemic manifestations, i.e. coagulopathies, bleeding in various organs, hemodynamic alterations which can lead to cardiovascular shock, and acute kidney injury. [

46,

47]

In Panama a study conducted in Veraguas province found that Bothrops asper is responsible of close to half of the ophidic events, and the rainy season is the time with higher frequency, with the venom causing frequent damage to feet, toes and hands according to the area in closer contact to the bite [

48]

Another study analyzed the effects of the reference venom of B. asper from Panama at local and systemic, which is consistent to the venoms of the Viperidae family. This venom possesses lethal, hemorrhagic, myotoxic, edema-forming, defibrinating and in vitro coagulant activities. This toxicological profile is similar to the one previously described for B. asper venoms from other Central American countries and from Mexico as well.[

49]

3.7. Nicaragua

Several studies have been conducted in Nicaragua one of them by Campbell and Lamar who find the main species involved in this event were Crotalus simus and Bothrops asper, and most fatal events were reported in areas of the East and center regions [

50]. Similar findings are stated by Hansson (2010) who also found a 5-year incidence of 56 snakebites per 100,000 inhabitants. 34 reported fatal snakebites in Nicaragua in 2005–2009, 0.6 fatal cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 5 years and a 1% case fatality rate.[

51]

Seasonal variation which is most pronounced in the east part of the country where the incidence almost triples between the lowest (May) and highest (December) months were described by Hansson in the 2010 publication [

51]

Moreno Avellano (2000) described as the most affected age group those from 12 to 20, living in rural areas and working the agriculture having a clear male predominance. The event affected the lower limbs in 71% of the cases and the rest in upper limbs; the mean time to reach a hospital was 8 hours and the mean stay in the hospital was 4 days in a recovered condition. ; 89% of them received treatment with antivenom The most common snake species in his study was

Crotalus durissus and the most common symptoms included pain and edema, bleeding, paresthesia’s and vomiting. [

52]

Studies in Central America has been oriented some to clarify the epidemiology of the snakebites but some of them have provided information on mortality without placing emphasis in some epidemiological parameters, He have selected some of them to prepare the following table (see

Table 2)

4. Discussion

Snakebites constitute an important health problem in the Central American Region but as a neglected problem requires to be better and more complete descriptions, and the development of plan to improve accessibility to medical attention and antivenom since according to the different publications the time between the bite and the arrival to health facilities can take from several hours to longer than one day, time enough for the venom to destroy tissue around the bite zone, cause hemorrhages or coagulation disorders that may affect multiple organs even the Central Nervous systems by causing endocranial hemorrhages, and in the case of snakes of the Micrurus genre motor, sensitive and sensorial damages.

From the history of these countries, we see the relationship between the subsistence agriculture as well as the emergence of the commercial agriculture specially in the Caribbean Coast where Bothrops asper lives, bringing closer the human and snake’s habitat leading to the undesirable encounters and accidents.

It's important to have a population better informed about the types of snakes and the expected clinical damage of the ophidian accident, this knowledge seems to be unevenly distributed in the population of the different countries, being Costa Rica the country with more advantages because of the local production of anti-venoms, access to the clinics and better knowledge among the population.

Two areas that need to be considered are the adequate supply of antivenom where they are required (according to the epidemiological data) and the frequency of accidents caused by the different species to avoid problems and spoil of the inadequate antivenom.

Knowing that in many locations access to medical facilities is difficult many people rely on local treatments usually based on plants extracts, these products require more research of their real benefit of this type of treatment and in those cases where there is a body of knowledge supporting it, processes of knowledge translation should be conducted.

Information taken from the patients needs to be accurate and complete (as much as possible) to complete an adequate profile of the victims of ophidian accidents to feed the decision making of the health systems in the countries affected by this neglected disease.

Not all patients receive treatment with antivenom and in optimistic calculations the coverage reaches less than 80%, one of the reasons for this deficit in the treatment is lack of clarity of the protocols for the management of these patients or the total absence of them in the medical facilities [

25]

Since this health condition has the intervention of snakes it’s important to inform adults and educate children about the risks of an encounter with reptiles and also the need to familiarize themselves with the features of the most common poisonous snakes in the different regions of Central America, and if possible, to desensitize the population of the impact caused to have the possibility to identify it. This fact can facilitate the early and specific management of cases, and the prevention of avoiding accidents.

Clinical records usually keep information about the snakebite and the immediate management in medical facilities but the sequela to the envenoming is not well recorded and conditions like physical disability and mental trauma can remain as an individual and social problem with an impact not qualified nor quantified even when there are estimates by international organizations. There are acute consequences of the snakebites in productivity and school attendance but sometimes when treatment doesn’t solve all the physical problems there is a reduction in the capacity of performing daily functions in daily life and in economic productive activities. In Central America and especially in the most distant community’s mortality and disability are difficult to avoid the first one or treat and decrease the second. [

53]. The Ministries of Health in Central America must address this problem of their neglected population as it’s the case in other regions of the world [

54,

55]

5. Conclusions

Snakebites constitute a worldwide problem, and Central America is not an exception to this neglected problem but it’s not well known except in small research groups. The increasing overlap of the habitat of multiple snakebites species and the rural habitat of human population leads to an increasing risk of suffering snakebites. The health services need to respond to the Ophidian accidents knowing the epidemiology of the problems analyzing these interactions between the reptiles and the communities that follow similar pattern across the Central American countries, observing the coincidence of different ecosystems and the relative predominance of certain species, pattern of clinical symptoms and the need to be ready with more specific antivenoms to prevent tissular damages, bleeding disorder and neurological impact among the most frequent clinical manifestations.

With the exception of El Salvador the most frequent Ophidian accident is caused by the attack of the Bothrops asper snake (its preferred habitat are the humid lowlands along the Caribbean coast and some inlands with similar characteristics.

From the data reviewed by the researchers in the different countries the anatomic areas with more frequent exposure to the snakebites are the limbs specially the lower limbs (feet, legs and occasional thighs), The upper limbs are exposed through the manipulation of tree branches, bushes, soil or crops during agricultural routines. Any preventive program has to devise methods to protect or cover those areas starting with the avoidance of vulnerable sandals or being barefoot in areas of risk.

Given the remoteness of many villages and hamlets affected by snakebites, Central America requires to bring treatment facilities closer to those rural areas, and to learn more about the traditional practices to treat snakebites to verify its real value and the need to systematize it to provide effective care to those iess accessible localities

Future Directions

The governments in Central America need to prioritize the problem of Snakebites as part of the third sustainable development goal related to Neglected Tropical Diseases involving not only the Health sector but also the Education, and productive one since they result affected by this type of accidents. Snakebites as An occupational risk first and disease should count with more protection prior to any exposure and prevision on what to do once accidents have occurred.

The academic sector needs to stimulate more research on the ecology of the disease, the toxinology of the main reported venoms in the region, and from the clinical perspective the events of disease reported in the population and to promote actively the collection and analysis of venoms to produce more specific antivenoms.

Accessibility to venoms for the population requires identifying areas closer to the most frequent places of accidents, and to train the medical personnel in those sites to use it according to official guidelines

The study of natural products is already impulse in some countries, it’s required to stimulate this type of studies in graduate programs to identify alternatives

The aspiration for the governments and communities should be to have a world free of mortality and with the preventions taken to avoid morbidity caused by the ophidian accidents.

Author Contributions

EFC conceptualize the project , went over the databases, extracted the information, wrote the first draft and analyze the data taken from the databases, ISF read the document, revised the document and the original information, provided observations and work on new ideas for strengthening the recommendations. We both have read the document and take responsibility for it.

Funding

“This research received no external funding” given that there was no need to use additional resources to those in our academic use.

Informed Consent Statement

There was not direct interaction with human subjects or individualized information that require special consent.

Data Availability Statement

Databases are available online without any restrictions.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the support provided by Neiby and Milan Fernandez supporting the tasks to move ahead this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harrison RA, Casewell NR, Ainsworth SA, Lalloo DG. The time is now: a call for action to translate recent momentum on tackling tropical snakebite into sustained benefit for victims. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(12):835–8. [CrossRef]

- Chippaux JP. Incidence and mortality due to snakebite in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(6):e0005662. [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik S, Zwi AB, Norton R, Jagnoor J. How and why snakebite became a global health priority: a policy analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2023 Aug;8(8):e011923. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- GBD 2019 Snakebite Envenomation Collaborators. Global mortality of snakebite envenoming between 1990 and 2019. Nat Commun 13, 6160 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Harrison RA, Hargreaves A, Wagstaff SC, Faragher B, Lalloo DG. Snake envenoming: a disease of poverty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009 Dec 22;3(12):e569. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Russell FE, Walter FG, Bey TA, Fernandez MC. Snakes and snakebite in Central America. Toxicon. 1997 Oct;35(10):1469-522. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, J. M. (2016). Understanding and confronting snakebite envenoming: The harvest of cooperation. Toxicon, 109, 51-62. [CrossRef]

- Neri-Castro E, Bénard-Valle M, Paniagua D, V Boyer L, D Possani L, López-Casillas F, Olvera A, Romero C, Zamudio F, Alagón A. Neotropical Rattlesnake (Crotalus simus) Venom Pharmacokinetics in Lymph and Blood Using an Ovine Model. Toxins (Basel). 2020 Jul 17;12(7):455. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jowers, M.J., Smart, U., Sánchez-Ramírez, S. et al. Unveiling underestimated species diversity within the Central American Coralsnake, a medically important complex of venomous taxa. Sci Rep 13, 11674 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Centeno, D. (2015). Ética sobre el envenenamiento por serpiente en el agro paisaje de Guatemala. Ciencia, Tecnologí a Y Salud, 2(1), 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Fernández C, E.A., Youssef, P. Snakebites in the Americas: a Neglected Problem in Public Health. Curr Trop Med Rep 11, 19–27 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chippaux JP. Incidence and mortality due to snakebite in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Jun 21;11(6):e0005662. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saravia P, Rojas E, Arce V, Guevara C, López JC, Chaves E, Velásquez R, Rojas G, Gutiérrez JM. Geographic and ontogenic variability in the venom of the neotropical rattlesnake Crotalus durissus: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Rev Biol Trop. 2002 Mar;50(1):337-46. [PubMed]

- Arroyo C, S. Solano, A. Segura, M. Herrera, R. Estrada, M. Villalta, M. Vargas, J.M. Gutiérrez, G. Leon. Cross-reactivity and cross-immunomodulation between venoms of the snakes Bothrops asper, Crotalus simus and Lachesis stenophrys, and its effect in the production of polyspecific antivenom for Central America. Toxicon, 138 (2017), pp. 43-48. [CrossRef]

- Hernández R, Cabalceta C, Saravia-Otten P, Chaves A, Gutiérrez JM, Rucavado A. Poor regenerative outcome after skeletal muscle necrosis induced by Bothrops asper venom: alterations in microvasculature and nerves. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19834. Epub 2011 May 24. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2011;6(7). doi: 10.1371/annotation/9caa2be8-b5e6-4553-8575-f0b575442172. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutiérrez JM, Escalante T, Hernández R, Gastaldello S, Saravia-Otten P, Rucavado A. Why is Skeletal Muscle Regeneration Impaired after Myonecrosis Induced by Viperid Snake Venoms? Toxins (Basel). 2018 May 1;10(5):182. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutierrez JM, Dos Santos MC, Furtado MF, Rojas G. Biochemical and pharmacological similarities between the venoms of newborn Crotalus durissus durissus and adult Crotalus durissus terrificus rattlesnakes. Toxicon 1991, 29, 1273-1277. [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, R.; Marín, O.; Mora-Medina, E.; Alfaro, E. A. El accidente ofídico por cascabela (Crotalus durissus durissus) en Costa Rica Acta Méd. Costarric. 1981, 24, 211– 214.

- Gutiérrez, J. M. Snakebite envenomation in Central America In Handbook of venoms and toxins of reptiles; Mackessy, S. P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2009; pp 491− 507.

- Gutiérrez, J.M. Current challenges for confronting the public health problem of snakebite envenoming in Central America. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 20, 7 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hessel MM, McAninch SA. Coral Snake Toxicity. [Updated 2023 Mar 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519031/.

- Sant’Ana Malaque, C.M., Gutiérrez, J.M. (2015). Snakebite Envenomation in Central and South America. In: Brent, J., Burkhart, K., Dargan, P., Hatten, B., Megarbane, B., Palmer, R. (eds) Critical Care Toxicology. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Giovannini P, Howes MR. Medicinal plants used to treat snakebite in Central America: review and assessment of scientific evidence. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;199:240–56. [CrossRef]

- https://lovefm.com/boy-hospitalized-after-snake-bite-in-southern-belize/.

- Wellmann, I. A., & Guerra-Centeno, D. (2020). Envenenamientos por mordedura de serpiente en Guatemala: revisión de literatura. Ciencia, Tecnologí a Y Salud, 7(2), 251–264. [CrossRef]

- Yee-Seuret, S., Vargas-González, A., & Hernández-Torres, L. (2012). Mordeduras por serpientes venenosas en Guatemala. Revista Electrónica de Portales Medicos.com. Recuperado de https://www.portalesmedicos.com/publicaciones/articles/4946/1/Mordeduras-por-serpientes-venenosas-en-Guatemala.html.

- Maltez, J. C. (1994). Accidente ofídico: Estudio retrospectivo, clínico, antropológico y epidemiológico, realizado en el departamento de Guatemala, Región Sur, del 1 de enero de 1987 al 31 de diciembre de 1992, Guatemala (Tesis de licenciatura). Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.

- Letona, C. A. (2012). Guía de animales ponzoñosos de Guatemala: Manejo del paciente intoxicado (Tesis de licenciatura). Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.

- Guerra-Centeno, D. (2016). Perfil epidemiológico del accidente ofídico en las tierras bajas de Guatemala. Ciencia, Tecnología y Salud, 3(2), 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Matute-Martínez CF, Sánchez-Sierra LE, Barahona-López DM, LaínezMejía JL, Matute-Martínez FJ, Perdomo-Vaquero R. Caracterización de pacientes que sufrieron mordedura de serpiente, atendidos en Hospital Público de Juticalpa, Olancho. Rev Fac Cienc Med. 2016;13(1):18–26.

- Laínez Mejía JL, Barahona López DM, Sánchez Sierra LE, Matute Martínez CF, Córdova Avila CN, Perdomo Vaquero R. Caracterización de pacientes con mordedura de serpiente atendidos en Hospital Tela, Atlantida - Characterization of patients with snake bite treated in Tela, Atlántida Hospital. Rev Fac Cienc Méd (Impr.). 2017;14(1):9–17.

- Izaguirre Gonzalez AI, Matute Martinez CF, Barahona Lopez DM, Sanchez-Sierra LE, Perdomo-Vaquero R. Clinical epidemiological characterization of snakebites at the Hospital Sta Teresa de Comayagua 2014-2015. Rev Med Hondur. 2017;85: 21–6.

- Ponce Orellana CP. Caracterizacion Epidemiológica y Clinica de Pacientes con envenenamiento por mordedura de serpiente en Pediatria de Enero 2015 a Junio 2016.Medical specialty Thesis. Universidad Nacional de Honduras; 2016. p. 71.

- Pinto LJ, Lee Fernández L, Gutiérrez JM, Simón DS, Ceballos Z, Aguilar LF, Sierra M. Case Report: Hemothorax in Envenomation by the Viperid Snake Bothrops asper. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019 Mar;100(3):714-716. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cerrato Contreras RS. Mordeduras de Serpiente in Hospital Leonardo Martinez Valenzuela 1981-1985. Medical specialty Thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras1989.p 94.

- Cerna Rodríguez, Darwin Alexis (2023) Características epidemiológicas y complicaciones asociadas a mordeduras de serpiente en el hospital materno infantil, Tegucigalpa. MDC. Honduras, en el periodo comprendido de agosto 2018 a septiembre 2019. Medical specialty thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, Managua.

- Aleman B, de Clerck E, Fenegan B, Casanoves B, Garcia J. Caracterización de Reptiles y percepción local hacia las serpientes en la subcuenca del rio Copan, Honduras. Agroforesteria en las Americas. 2011;48:103–17. CATIE, Turrialba, Costa Rica.

- Gutiérrez JM, Castillo L, de Naves KMD, Masís J, Alape-Girón A. Epidemiology of snakebites in El Salvador (2014-2019). Toxicon. 2020 Oct 30;186:26-28. Epub 2020 Jul 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud de El Salvador, 2013. Lineamientos Técnicos para la Prevención y Atención de Personas Mordidas por Serpiente. Ministerio de Salud, San Salvador, El Salvador (2013), p. 40.

- Chirino Molina W Y,Mendoza Rodríguez E W,Gavidia Leiva C M. Epidemiology of venomous snake bites in El Salvador from 2011 to 2022. Alerta. 2025;8(1):47-54. [CrossRef]

- Fernández P, Gutiérrez JM. Mortality due to snakebite envenomation in Costa Rica (1993-2006). Toxicon. 2008 Sep 1;52(3):530-3. Epub 2008 Jun 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasa M, Segura Cano SE. New insights into snakebite epidemiology in Costa Rica: A retrospective evaluation of medical records. Toxicon X. 2020 Jul 30;7:100055. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montoya-Vargas W, Gutiérrez JM, Quesada-Morúa MS, Morera-Huertas J, Rojas C, Leon-Salas A. Preliminary assessment of antivenom availability and management in the public health system of Costa Rica: An analysis based on a survey to pharmacists in public health facilities. Toxicon X. 2022 Oct 22;16:100139. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jutzy DA, Biber SH, Elton NW, Lowry EC. A clinical and pathological analysis of snake bites on the Panama Canal Zone. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1953 Jan;2(1):129-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez SM, Salazar M, Acosta de Patiño H, Gómez L, Rodriguez A, Correa D, Saldaña J, Navarro D, Lomonte B, Otero-Patiño R, Gutiérrez JM. Geographical variability of the venoms of four populations of Bothrops asper from Panama: Toxicological analysis and neutralization by a polyvalent antivenom. Toxicon. 2017 Jun 15;132:55-61. Epub 2017 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D.A. Warrell. Snake bite. Lancet, 375 (2010), pp. 77-88. [CrossRef]

- R. Otero-Patiño .Epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects of Bothrops asper bites. Toxicon, 54 (2009), pp. 998-1011. [CrossRef]

- Pecchio M, Suárez JA, Hesse S, Hersh AM, Gundacker ND. Descriptive epidemiology of snakebites in the Veraguas province of Panama, 2007-2008. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2018 Oct 1;112(10):463-466. Erratum in: Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019 Dec 1;113(12):845. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz040. PMID: 30165536. [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Arjona, Alina, Acosta-de-Patiño, Hildaura, Martínez-Cortés, Víctor, Correa-Ceballos, David, Rodríguez, Abdiel, Gómez-Leija, Leandra, Vega, Natalia, Gutiérrez, José-María, & Otero-Patiño, Rafael. (2021). Toxicological, enzymatic, and immunochemical characterization of Bothrops asper (Serpentes: Viperidae) reference venom from Panama. Revista de Biología Tropical, 69(1), 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.A.; Lamar W.W. (2004). The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publishing Associates. pp. 870 pp. 1500.

- Hansson E, Cuadra S, Oudin A, de Jong K, Stroh E, Torén K, Albin M. Mapping snakebite epidemiology in Nicaragua--pitfalls and possible solutions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010 Nov 23;4(11):e896. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moreno Avellan AJ (2000). Manejo de las Mordeduras de serpientes venenosas en pacientes atendidos en el servicio de Mediicina interna en el Hospital Escuela Oscar Danilo Rosales Arguello durante el periodo de Enero 1997-Noviembre 1999. Monografia. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua.

- Funes IF, Youssef P, et al.,2024. Snakebites and their Impact on Disability, Medical Research Archives, [online] 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Aglanu LM, Amuasi JH, Schut BA, Steinhorst J, Beyuo A, Dari CD, Agbogbatey MK, Blankson ES, Punguyire D, Lalloo DG, Blessmann J, Abass KM, Harrison RA, Stienstra Y. What the snake leaves in its wake: Functional limitations and disabilities among snakebite victims in Ghanaian communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 May 23;16(5):e0010322. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ, Habib AG, Harrison RA, Williams DJ, Warrell DA. Snakebite envenoming. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Sep 14;3:17063. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Oct 05;3:17079. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.79. PMID: 28905944. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Global mortality of snakebite envenoming between 1990 and 2019 in Central America.

Table 1.

Global mortality of snakebite envenoming between 1990 and 2019 in Central America.

| Country |

Mortality 2019 |

Death age standardized rate per 100 000 in 2019 |

% of Change from 1990 to 2019 |

YLLs age standardized rate per 100,000 in 2019 |

% change 1990-2019 |

| Guatemala |

10(7.9-13) |

0.08 (0.06 to 0.10) |

82(28 to 144%) |

2.97(0.22 to 3.71) |

47 (3 to 103) |

| El Salvador |

1.3 (<1-1.9) |

0.02 (0.1 to 0.03) |

222% (58 to 401%) |

0.88(0.49 to 1.3) |

150 (66 to 300%) |

| Honduras |

5.3 (3.0 - 8.4) |

0.07 (0.04 to 0.12) |

-53(-71 to -24%) |

2.68 (1.59 to 4.33) |

65 (-78 to-43%) |

| Nicaragua |

7.9 (4.9 -10.0) |

0.15 (0.10 to 0.19) |

-51 (-65 to –29) |

5.95 (3.53 to 7.88) |

57 % (-70 to -28) |

| Costa Rica |

3.9 (2.9-52) |

0.08 (0.06 to 0.10) |

-20(-43 to 9%) |

2.4 (1.75 to 3.24) |

-23(-46 to 5%) |

| Panama |

14 (11-19) |

0.35 (0.26 to 0.46) |

-50 -64 to 31%) |

14.96(11.21 to 19.81) |

-50 (-64 to -32) |

| Beliza |

<1(<1-1.1) |

0.27(0.22 to 0.33) |

444 (302-607) |

10.38 (8.39 to 12.51) |

372 (248 to 509) |

Table 2.

Ilustrative studies on Snakebites in Central America. Adapted from studies conducted and included since 1980-2020.

Table 2.

Ilustrative studies on Snakebites in Central America. Adapted from studies conducted and included since 1980-2020.

| Author |

Country |

Study year (s) |

# cases |

Mean age in years |

Common Symptoms |

Time from snakebite to medicalfacility

|

| Letona (2012) |

Guatemala |

2002-2010 |

7377 |

15 |

Local pain, edema and bleeding |

No specified |

| Guerra Otero (2016) |

Guatemala |

2008-2013 |

305 |

25.2 |

Local pain, hemorrhages |

5.6 hrs |

| Yee Seuret (2012) |

Guatemala |

2008-2011 |

87 |

19 |

Local pain, edema |

No specified |

| Izaguirre Gonzalez (2014) |

Honduras |

2014-2015 |

36 |

15 |

Local inflammation and G-I disorders |

No specified |

| Lainez Mejia (2017) |

Honduras |

2013-2015 |

84 |

28 |

Local pain and edema |

5.4 hrs |

| Ponce Orellana (2016) |

Honduras |

2015-2016 |

33 |

15 |

Local symptoms, Gastro-Intestinal and hematological disorders |

No specified |

| Gutierrez JH (2020) |

El Salvador |

2014-2019 |

1130 |

15 |

No specified |

No specified |

| Chirinos Molina (2025) |

El Salvador |

2011-2022 |

1472 |

28 |

No specified |

No specified |

| Fernandez P (2008) |

Costa Rica |

1993-2006 |

48 defunction cases |

No information |

|

|

| Sasa (2020) |

Costa Rica |

2012-2013 |

475 |

29 years |

Coagulation disorders, pain edema and local necrosis |

1-3 hrs |

| Jutzi (1953) |

Panama |

1953 |

23 |

Not included |

Shock and hemorrhages |

No specified, 7 patients died |

| Pecchio (2019) |

Panama |

2007-2008 |

390 |

Not included |

Local symptoms and hemorrhages |

|

| Hanson (2010) |

Nicaragua |

2005-2009 |

56 |

Not included |

No specified |

34 deaths were reported |

| Moreno Avellan ( |

Nicaragua |

1997-1999 |

72 |

28 |

Pain, edema, parestesias, hemorrhages |

8 hours. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).