Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

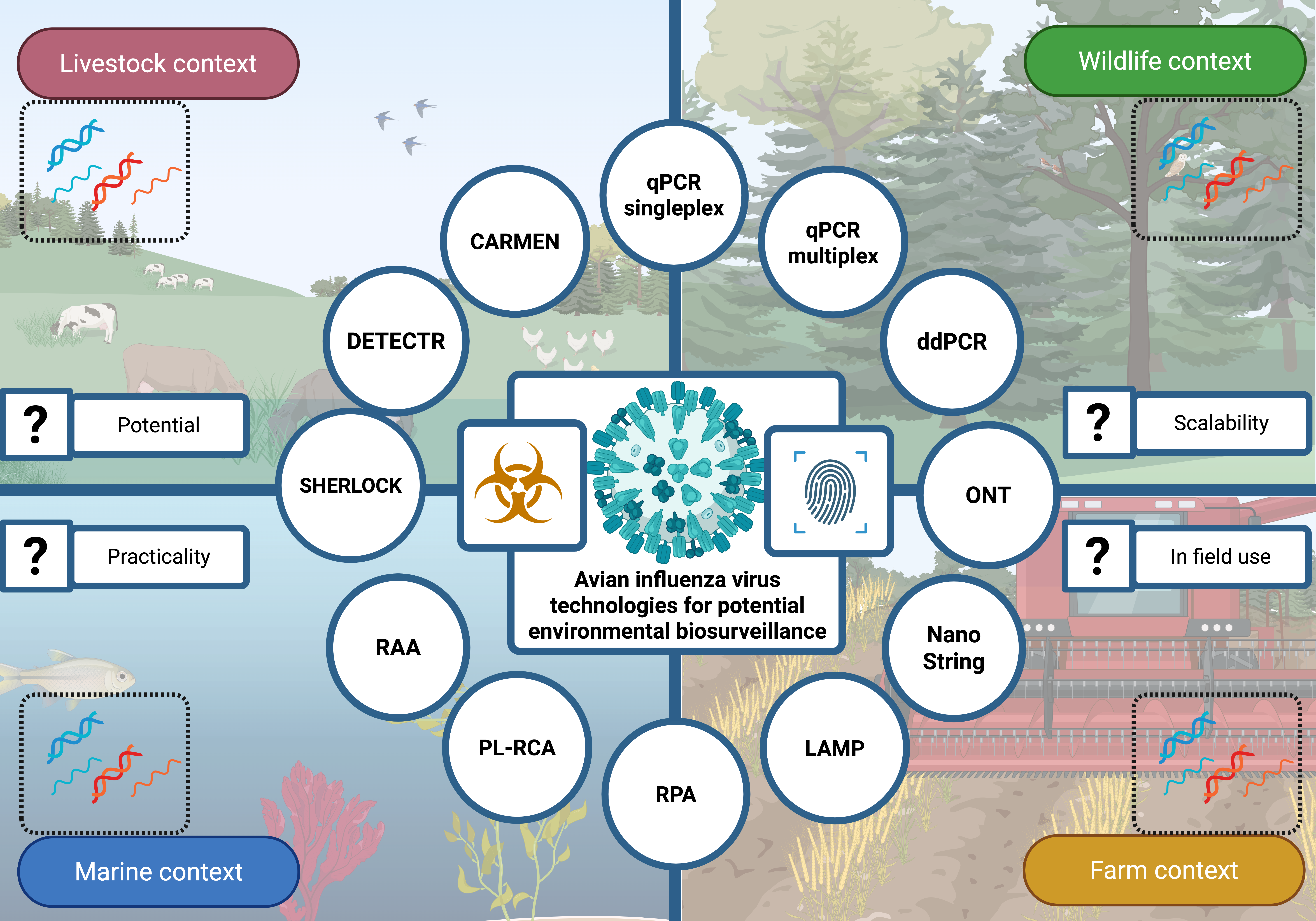

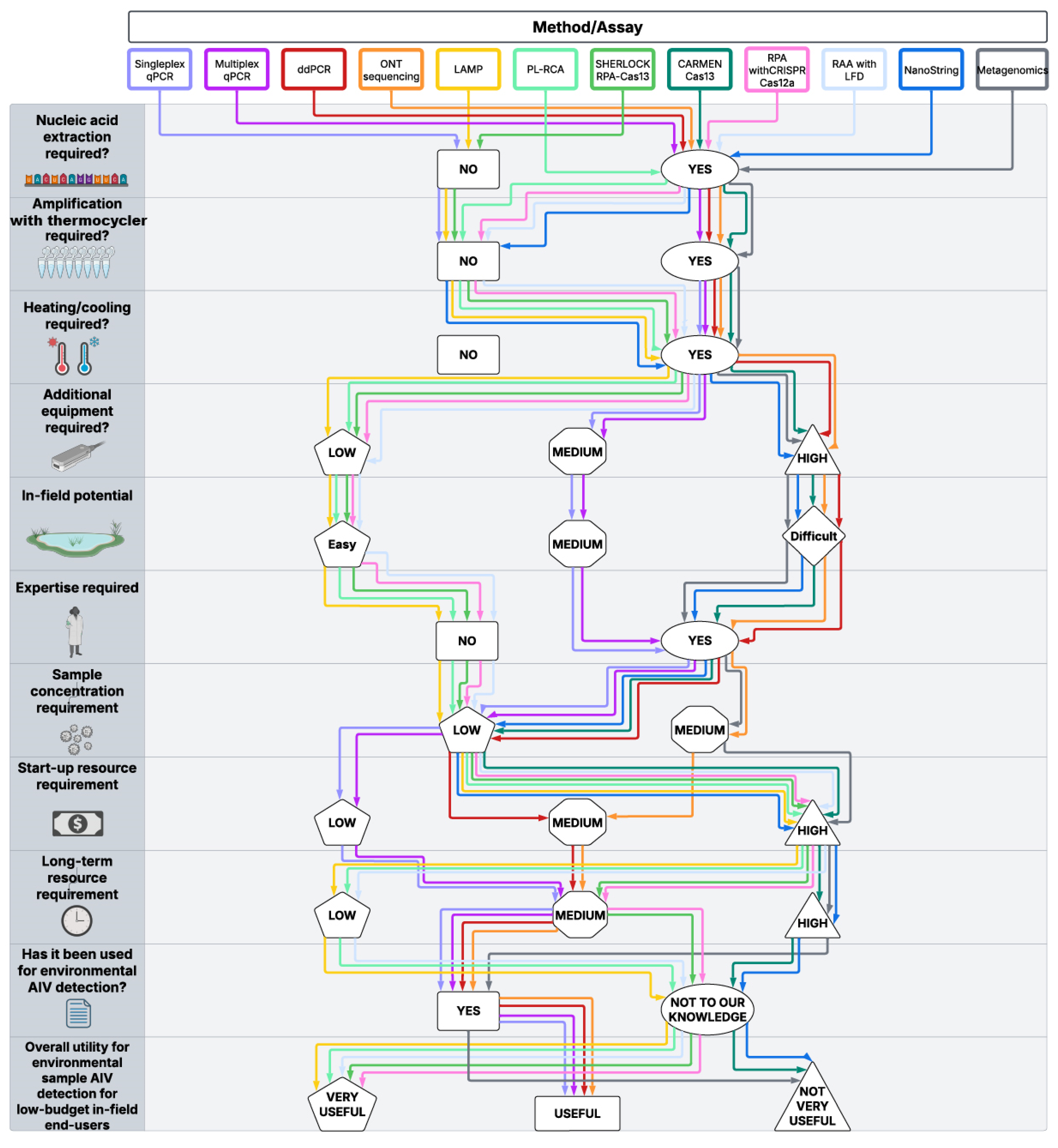

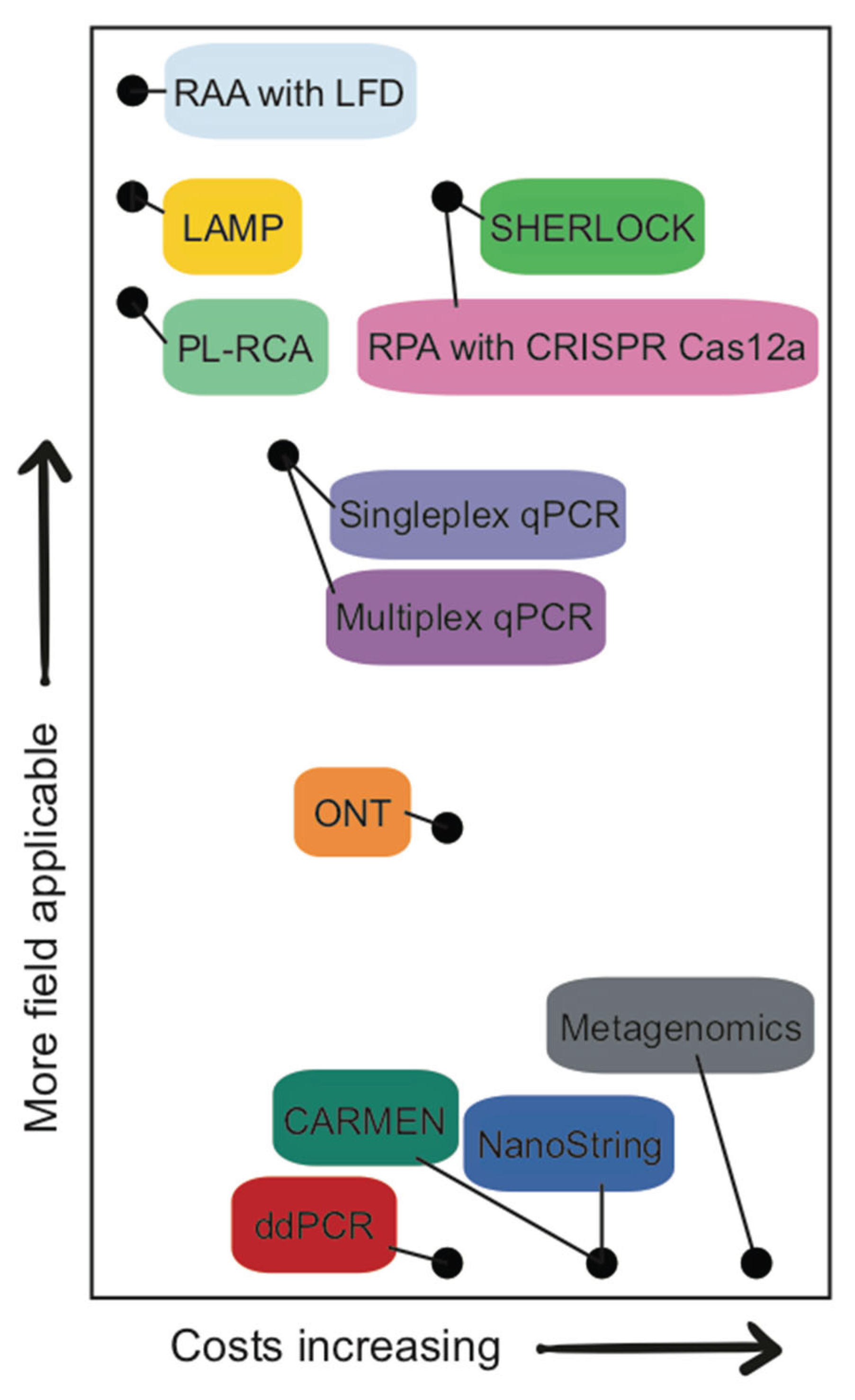

2. An Overview of Current Detection Methods for Monitoring Viruses in the Environment

2.1. Nucleic Acid Extraction

2.2. Amplification with Thermocycler

2.3. Heating and Cooling

2.4. Additional Equipment Required

2.5. In-Field Potential

2.6. Expertise

2.7. Sample Concentration

2.8. Start-Up and Long-Term Resources

2.9. Proven Use on Environmental AIV Samples

3. Application of These Methods to Avian Influenza Virus Environmental Detection

4. Limitations of Environmental Sampling for Viruses

5. Recommendations for Environmental Biosurveillance of Viruses

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, C. M., C. Myhrvold, S. G. Thakku, C. A. Freije, H. C. Metsky, D. K. Yang, and J. Kehe. 2020. Massively multiplexed nucleic acid detection with Cas13. Nature 582, 7811: 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlhoch, C., F. Baldinelli, A. Fusaro, and C. Terregino. 2022. Avian influenza, a new threat to public health in Europe? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 28, 2: 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. J. 2001. Newcastle disease. British poultry science 42, 1: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, N., A. Dayaram, J. Axtner, K. Tsangaras, M. L. Kampmann, A. Mohamed, and A. D. Greenwood. 2021. Non-invasive surveys of mammalian viruses using environmental DNA. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 12, 10: 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerwald, M. R., A. M. Goodbla, R. P. Nagarajan, J. S. Gootenberg, O. O. Abudayyeh, F. Zhang, and A. D. Schreier. 2020. Rapid and accurate species identification for ecological studies and monitoring using CRISPR-based SHERLOCK. Molecular Ecology Resources 20, 4: 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, K. G., A. E. Lachenauer, A. Nitido, S. Siddiqui, R. Gross, B. Beitzel, and S. B. Mehta. 2020. Deployable CRISPR-Cas13a diagnostic tools to detect and report Ebola and Lassa virus cases in real-time. Nature communications 11, 1: 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, D., K. W. Christison, G. D. Stentiford, L. S. Cook, and H. Hartikainen. 2023. Environmental DNA/RNA for pathogen and parasite detection, surveillance, and ecology. Trends in Parasitology 39, 4: 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beng, K. C., and R. T. Corlett. 2020. Applications of environmental DNA (eDNA) in ecology and conservation: opportunities, challenges and prospects. Biodiversity and Conservation 29, 7: 2089–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, P., B. Hayes, F. Filaire, L. Lèbre, T. Vergne, M. Pinson, and J.-L. Guérin. 2023. Optimizing environmental viral surveillance: bovine serum albumin increases RT-qPCR sensitivity for high pathogenicity avian influenza H5Nx virus detection from dust samples. Microbiology Spectrum 11, 6: e03055-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A., Z. Fatima, M. Ruwali, C. S. Misra, S. S. Rangu, D. Rath, and S. Hameed. 2022. CLEVER assay: A visual and rapid RNA extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 based on CRISPR-Cas integrated RT-LAMP technology. Journal of Applied Microbiology 133, 2: 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y., J. Yang, L. Wang, L. Ran, and G. F. Gao. 2024. Ecology and evolution of avian influenza viruses. Current biology 34, 15: R716–R721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billington, C., G. Abeysekera, P. Scholes, P. Pickering, and L. Pang. 2021. Utility of a field deployable qPCR instrument for analyzing freshwater quality. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 4, 4: e20223. [Google Scholar]

- Bivins, A., D. Kaya, W. Ahmed, J. Brown, C. Butler, J. Greaves, and S. Sherchan. 2022. Passive sampling to scale wastewater surveillance of infectious disease: Lessons learned from COVID-19. Science of the Total Environment 835: 155347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, H. A., X. Pochon, U. von Ammon, N. Gemmell, J.-A. L. Stanton, G.-J. Jeunen, and A. Zaiko. 2021. Towards the optimization of eDNA/eRNA sampling technologies for marine biosecurity surveillance. Water 13, 8: 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykin, L. M., P. Sseruwagi, T. Alicai, E. Ateka, I. U. Mohammed, J.-A. L. Stanton, and J. Erasto. 2019. Tree lab: Portable genomics for early detection of plant viruses and pests in sub-saharan africa. Genes 10, 9: 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, J. P., X. Deng, G. Yu, C. L. Fasching, V. Servellita, J. Singh, and A. Sotomayor-Gonzalez. 2020. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nature biotechnology 38, 7: 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A., K. S. Schaefer, A. Tsang, H. A. Yi, J. B. Grimm, A. L. Lemire, and K. Ritola. 2021. Direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using high-contrast pH-sensitive dyes. Journal of biomolecular techniques: JBT 32, 3: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. L., and C. L. Hewitt. 2025. A holistic marine biosecurity risk framework that is inclusive of social, cultural, economic and ecological values. Marine Policy 172: 106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. S., E. Ma, L. B. Harrington, M. Da Costa, X. Tian, J. M. Palefsky, and J. A. Doudna. 2018. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 360, 6387: 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-S., Y.-L. Yang, H.-Y. Wang, T.-K. Guo, R.-M. Azeem, C.-W. Shi, and J.-Z. Wang. 2024. CRISPR/Cas13a-based genome editing for establishing the detection method of H9N2 subtype avian influenza virus. Poultry Science 103, 10: 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croville, G., M. Walch, A. Sécula, L. Lèbre, S. Silva, F. Filaire, and J.-L. Guerin. 2024. An amplicon-based nanopore sequencing workflow for rapid tracking of avian influenza outbreaks, France. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, E. F., C. M. Peterse, J. M. Koelewijn, A.-M. R. van der Drift, R. F. van der Beek, E. Nagelkerke, and W. J. Lodder. 2022. The detection of monkeypox virus DNA in wastewater samples in the Netherlands. Science of the Total Environment 852: 158265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, E. M., N. O. I. Cogan, A. J. Gubala, P. T. Mee, K. J. O’Riley, B. C. Rodoni, and S. E. Lynch. 2022. Rapid, in-field deployable, avian influenza virus haemagglutinin characterisation tool using MinION technology. Scientific reports 12, 1: 11886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., Y. Cao, X. Wan, B. Wang, A. Sun, H. Wang, and H. Gu. 2022. Nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing for the rapid and precise detection of pathogens among immunocompromised cancer patients with suspected infections. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 12: 943859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J., X. Xu, Y. Deng, X. Zheng, and T. Zhang. 2024. Comparison of RT-ddPCR and RT-qPCR platforms for SARS-CoV-2 detection: Implications for future outbreaks of infectious diseases. Environment International 183: 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J. A., K. Yetsko, L. Whitmore, J. Whilde, C. B. Eastman, D. R. Ramia, and B. Burkhalter. 2021. Environmental DNA monitoring of oncogenic viral shedding and genomic profiling of sea turtle fibropapillomatosis reveals unusual viral dynamics. Communications Biology 4, 1: 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.-T., and E. K. Lipp. 2005. Enteric viruses of humans and animals in aquatic environments: health risks, detection, and potential water quality assessment tools. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews 69, 2: 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X., Q. Wang, B. Ma, B. Zhang, K. Sun, X. Yu, and M. Zhang. 2023. Advances in detection techniques for the H5N1 avian influenza virus. International journal of molecular sciences 24, 24: 17157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, G. K., R. E. Bumgarner, B. Birditt, T. Dahl, N. Dowidar, D. L. Dunaway, and T. Grogan. 2008. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nature biotechnology 26, 3: 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J. S., O. O. Abudayyeh, M. J. Kellner, J. Joung, J. J. Collins, and F. Zhang. 2018. Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science 360, 6387: 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D. W., E. K. Lipp, M. R. Mclaughlin, and J. B. Rose. 2001. Marine Recreation and Public Health Microbiology: Quest for the Ideal Indicator: This article addresses the historic, recent, and future directions in microbiological water quality indicator research. Bioscience 51, 10: 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, G., X. Roche, A. Brioudes, S. von Dobschuetz, F. O. Fasina, W. Kalpravidh, and L. Sims. 2021. A literature review of the use of environmental sampling in the surveillance of avian influenza viruses. Transboundary and emerging diseases 68, 1: 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M., S. Liu, Y. Xu, A. Li, W. Wu, M. Liang, and T. Wang. 2022. CRISPR/Cas12a technology combined with RPA for rapid and portable SFTSV detection. Frontiers in Microbiology 13: 754995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, L. E., C. E. Givens, E. A. Stelzer, M. L. Killian, D. W. Kolpin, C. M. Szablewski, and R. L. Poulson. 2023. Environmental surveillance and detection of infectious highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in Iowa wetlands. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 10, 12: 1181–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, L. E., E. A. Stelzer, R. L. Poulson, D. W. Kolpin, C. M. Szablewski, and C. E. Givens. 2024. Development of a Large-Volume Concentration Method to Recover Infectious Avian Influenza Virus from the Aquatic Environment. Viruses 16, 12: 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huver, J., J. Koprivnikar, P. Johnson, and S. Whyard. 2015. Development and application of an eDNA method to detect and quantify a pathogenic parasite in aquatic ecosystems. Ecological applications 25, 4: 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S., D. S. Dandy, B. J. Geiss, and C. S. Henry. 2021. Padlock probe-based rolling circle amplification lateral flow assay for point-of-need nucleic acid detection. Analyst 146, 13: 4340–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, M. M., M. M. Diagne, M. H. D. Ndione, M. A. Barry, N. K. Ndiaye, D. E. Kiori, and M. Fall. 2025. Genetic and Molecular Characterization of Avian Influenza A (H9N2) Viruses from Live Bird Markets (LBM) in Senegal. Viruses 17, 1: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P., T. G. Aw, W. Van Bonn, and J. B. Rose. 2020. Evaluation of a portable nanopore-based sequencer for detection of viruses in water. Journal of Virological Methods 278: 113805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. A. 2021. Global plant virus disease pandemics and epidemics. Plants 10, 2: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, H., T. Iida, K. Aoki, S. Ohno, and T. Suzutani. 2005. Sensitive and rapid detection of herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus DNA by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 43, 7: 3290–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y., J. Wang, W. Zhang, Y. Xu, B. Xu, G. Qu, and G. Su. 2023. RNA extraction-free workflow integrated with a single-tube CRISPR-Cas-based colorimetric assay for rapid SARS-CoV-2 detection in different environmental matrices. Journal of Hazardous Materials 454: 131487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawato, Y., T. Mekata, M. Inada, and T. Ito. 2021. Application of environmental DNA for monitoring Red Sea bream Iridovirus at a fish farm. Microbiology Spectrum 9, 2: e00796-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfir, R., and B. Genthe. 1993. Advantages and disadvantages of the use of immunodetection techniques for the enumeration of microorganisms and toxins in water. Water Science and Technology 27, 3–4: 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchinski, K. S., M. Coombe, S. C. Mansour, G. A. P. Cortez, M. Kalhor, C. G. Himsworth, and N. A. Prystajecky. 2024. Targeted genomic sequencing of avian influenza viruses in wetland sediment from wild bird habitats. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 90, 2: e00842-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumblathan, T., Y. Liu, G. K. Uppal, S. E. Hrudey, and X.-F. Li. 2021. Wastewater-based epidemiology for community monitoring of SARS-CoV-2: progress and challenges. ACS Environmental Au 1, 1: 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalli, M. A., J. S. Langmade, X. Chen, C. C. Fronick, C. S. Sawyer, L. C. Burcea, and W. J. Buchser. 2021. Rapid and extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 from saliva by colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clinical Chemistry 67, 2: 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Y. Dai, Y. Liu, Z. Ren, H. Guo, Z. Li, and S. Zhang. 2022. Rapid PCR-based nanopore adaptive sequencing improves sensitivity and timeliness of viral clinical detection and genome surveillance. Frontiers in Microbiology 13: 929241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, S. 2024. Wastewater surveillance for influenza A virus and H5 subtype concurrent with the highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus outbreak in cattle and poultry and associated human cases—United States, May 12–July 13, 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, T., J. Melnick, and M. Estes. 1995. Environmental virology: from detection of virus in sewage and water by isolation to identification by molecular biology-a trip of over 50 years. Annual review of microbiology 49: 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J., L. Zuo, D. He, Z. Fang, N. Berthet, C. Yu, and G. Wong. 2023. Rapid detection of Nipah virus using the one-pot RPA-CRISPR/Cas13a assay. Virus research 332: 199130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, C. S., S. S. Rangu, R. D. Phulsundar, G. Bindal, M. Singh, R. Shashidhar, and D. Rath. 2022. An improved, simple and field-deployable CRISPR-Cas12a assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Applied Microbiology 133, 4: 2668–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msemburi, W., A. Karlinsky, V. Knutson, S. Aleshin-Guendel, S. Chatterji, and J. Wakefield. 2023. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 613, 7942: 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, K. B., and F. A. Faloona. 1987. [21] Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. In Methods in enzymology. Elsevier: Vol. 155, pp. 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrvold, C., C. A. Freije, J. S. Gootenberg, O. O. Abudayyeh, H. C. Metsky, A. F. Durbin, and L. A. Parham. 2018. Field-deployable viral diagnostics using CRISPR-Cas13. Science 360, 6387: 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabeshima, K., S. Asakura, R. Iwata, H. Honjo, A. Haga, K. Goka, and M. Onuma. 2023. Sequencing methods for HA and NA genes of avian influenza viruses from wild bird feces using Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 102: 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, G., and Y. Kawaoka. 2024. Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus outbreak in cattle: the knowns and unknowns. Nature Reviews Microbiology 22, 9: 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M., Y. Zhou, F. Li, H. Deng, M. Zhao, Y. Huang, and L. Zhu. 2022. Epidemiological investigation of swine Japanese encephalitis virus based on RT-RAA detection method. Scientific reports 12, 1: 9392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T., H. Okayama, H. Masubuchi, T. Yonekawa, K. Watanabe, N. Amino, and T. Hase. 2000. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 12: e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwe, M. K., N. Jangpromma, and L. Taemaitree. 2024. Evaluation of molecular inhibitors of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). Scientific reports 14, 1: 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldstone, M. B. 2020. Viruses, plagues, and history: past, present, and future. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parameswari, B., P. Anbazhagan, A. Rajashree, G. Chaitra, K. Sidharthan, S. Mangrauthia, and B. Bhaskar. 2025. Development of reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid diagnostics of Peanut mottle virus. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 31, 1: 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepenburg, O., C. H. Williams, D. L. Stemple, and N. A. Armes. 2006. DNA detection using recombination proteins. PLoS biology 4, 7: e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, S., D. Calderón-Franco, and T. Abeel. 2024. Portable In-Field DNA Sequencing for Rapid Detection of Pathogens and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Proof-of-Concept Study. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, P. I., V. Gamarra-Toledo, J. R. Euguí, and S. A. Lambertucci. 2024. Recent changes in patterns of mammal infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus worldwide. Emerging Infectious Diseases 30, 3: 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J., N. D. Grubaugh, S. T. Pullan, I. M. Claro, A. D. Smith, K. Gangavarapu, and N. A. Beutler. 2017. Multiplex PCR method for MinION and Illumina sequencing of Zika and other virus genomes directly from clinical samples. Nature protocols 12, 6: 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rački, N., T. Dreo, I. Gutierrez-Aguirre, A. Blejec, and M. Ravnikar. 2014. Reverse transcriptase droplet digital PCR shows high resilience to PCR inhibitors from plant, soil and water samples. Plant methods 10: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Córdova, C., D. Morales-Jadán, S. Alarcón-Salem, A. Sarmiento-Alvarado, M. B. Proaño, I. Camposano, and D. Coello. 2023. Fast, cheap and sensitive: Homogenizer-based RNA extraction free method for SARS-CoV-2 detection by RT-qPCR. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 13: 1074953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A., N. Kumar, C. P. Singh, and M. Singh. 2023. Environmental DNA (eDNA): Powerful technique for biodiversity conservation. Journal for Nature Conservation 71: 126325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, J. J., M. Ormond, and Y. Keynan. 2021. Extraction-free RT-LAMP to detect SARS-CoV-2 is less sensitive but highly specific compared to standard RT-PCR in 101 samples. Journal of Clinical Virology 136: 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriver, M., U. von Ammon, C. Youngbull, X. Pochon, J.-A. L. Stanton, N. J. Gemmell, and A. Zaiko. 2024. Drop it all: extraction-free detection of targeted marine species through optimized direct droplet digital PCR. PeerJ 12: e16969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. J., and A. M. Osborn. 2009. Advantages and limitations of quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)-based approaches in microbial ecology. FEMS microbiology ecology 67, 1: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.-A. L., A. Muralidhar, C. J. Rand, and D. J. Saul. 2019. Rapid extraction of DNA suitable for NGS workflows from bacterial cultures using the PDQeX. Biotechniques 66, 5: 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijk, R., A. van den Ouden, J. Louwerse, K. Čurová, R. Burggrave, B. McNally, and G. de Vos. 2023. Ultrafast RNA extraction-free SARS-CoV-2 detection by direct RT-PCR using a rapid thermal cycling approach. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 107, 1: 115975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temin, H. M., and S. Mizutami. 1970. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus.

- Thalinger, B., K. Deiner, L. R. Harper, H. C. Rees, R. C. Blackman, D. Sint, and K. Bruce. 2021. A validation scale to determine the readiness of environmental DNA assays for routine species monitoring. Environmental DNA 3, 4: 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisza, M. J., B. Hanson, J. R. Clark, L. Wang, K. Payne, M. C. Ross, and J. J. Cormier. 2024. Virome Sequencing Identifies H5N1 Avian Influenza in Wastewater from Nine Cities. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Vogels, C. B., M. I. Breban, I. M. Ott, T. Alpert, M. E. Petrone, A. E. Watkins, and J. Goes de Jesus. 2021. Multiplex qPCR discriminates variants of concern to enhance global surveillance of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS biology 19, 5: e3001236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., H. Chen, K. Lin, Y. Han, Z. Gu, H. Wei, and R. Jin. 2024. Ultrasensitive single-step CRISPR detection of monkeypox virus in minutes with a vest-pocket diagnostic device. Nature communications 15, 1: 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N., B. Zheng, J. Niu, T. Chen, J. Ye, Y. Si, and S. Cao. 2022. Rapid detection of genotype II African swine fever virus using CRISPR Cas13a-based lateral flow strip. Viruses 14, 2: 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M. K., D. Duong, B. Shelden, E. M. Chan, V. Chan-Herur, S. Hilton, and B. J. White. 2024. Detection of hemagglutinin H5 influenza A virus sequence in municipal wastewater solids at wastewater treatment plants with increases in influenza A in spring, 2024. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, M. K., A. H. Paulos, A. Zulli, D. Duong, B. Shelden, B. J. White, and A. B. Boehm. 2023. Wastewater detection of emerging arbovirus infections: Case study of Dengue in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 11, 1: 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y. P., S. Othman, Y. L. Lau, S. Radu, and H. Y. Chee. 2018. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a versatile technique for detection of micro-organisms. Journal of Applied Microbiology 124, 3: 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., X. Cao, Y. Meng, D. Richards, J. Wu, Z. Ye, and A. J. deMello. 2022. DropCRISPR: A LAMP-Cas12a based digital method for ultrasensitive detection of nucleic acid. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 211: 114377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, A., A. Shahid, A. Shamim, S. H. Khan, and M. I. Arshad. 2023. The SHERLOCK platform: an insight into advances in viral disease diagnosis. Molecular Biotechnology 65, 5: 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y., X. Wu, A. Gu, L. Dobelle, C. A. Cid, J. Li, and M. R. Hoffmann. 2021. Membrane-based in-gel loop-mediated isothermal amplification (mgLAMP) system for SARS-CoV-2 quantification in environmental waters. Environmental Science & Technology 56, 2: 862–873. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).