Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Olink Proteomics Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Identification of Differentially Expressed Inflammation-Related Biomarkers

3.3. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Proteins

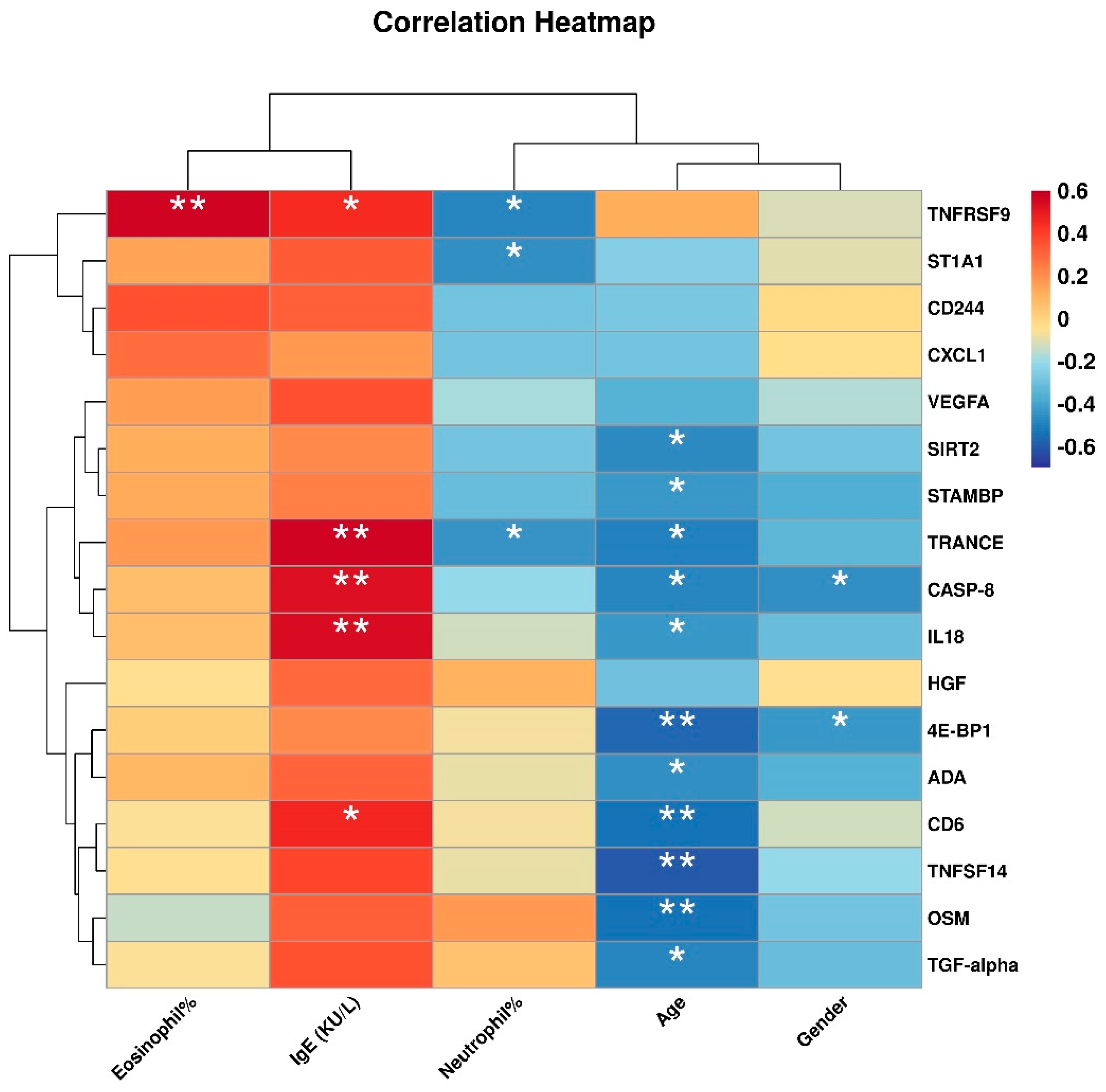

3.4. Correlation between Differentially Expressed Inflammation-Related Proteins and Clinical Features

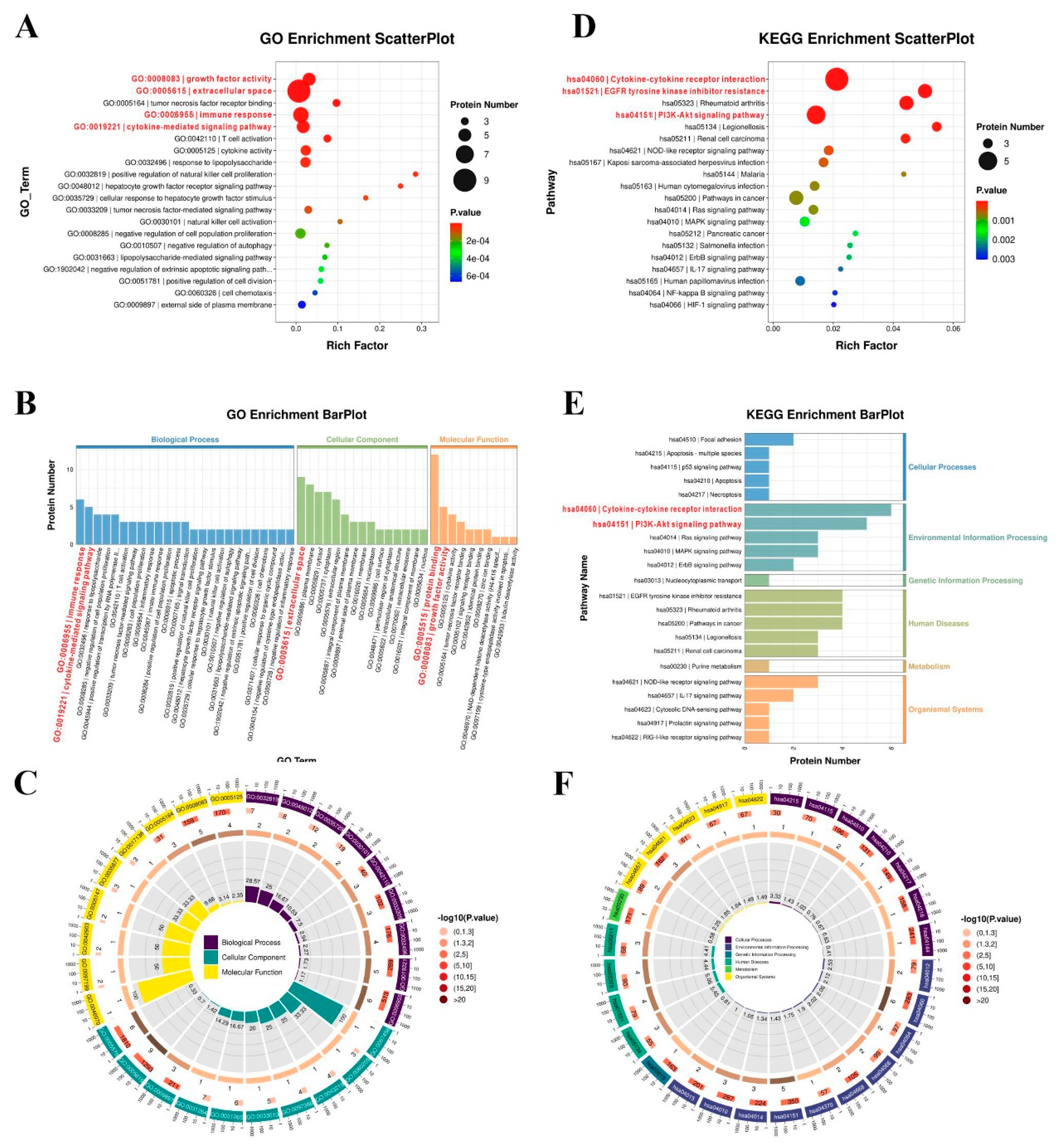

3.5. Function Enrichment of Differentially Expressed Proteins

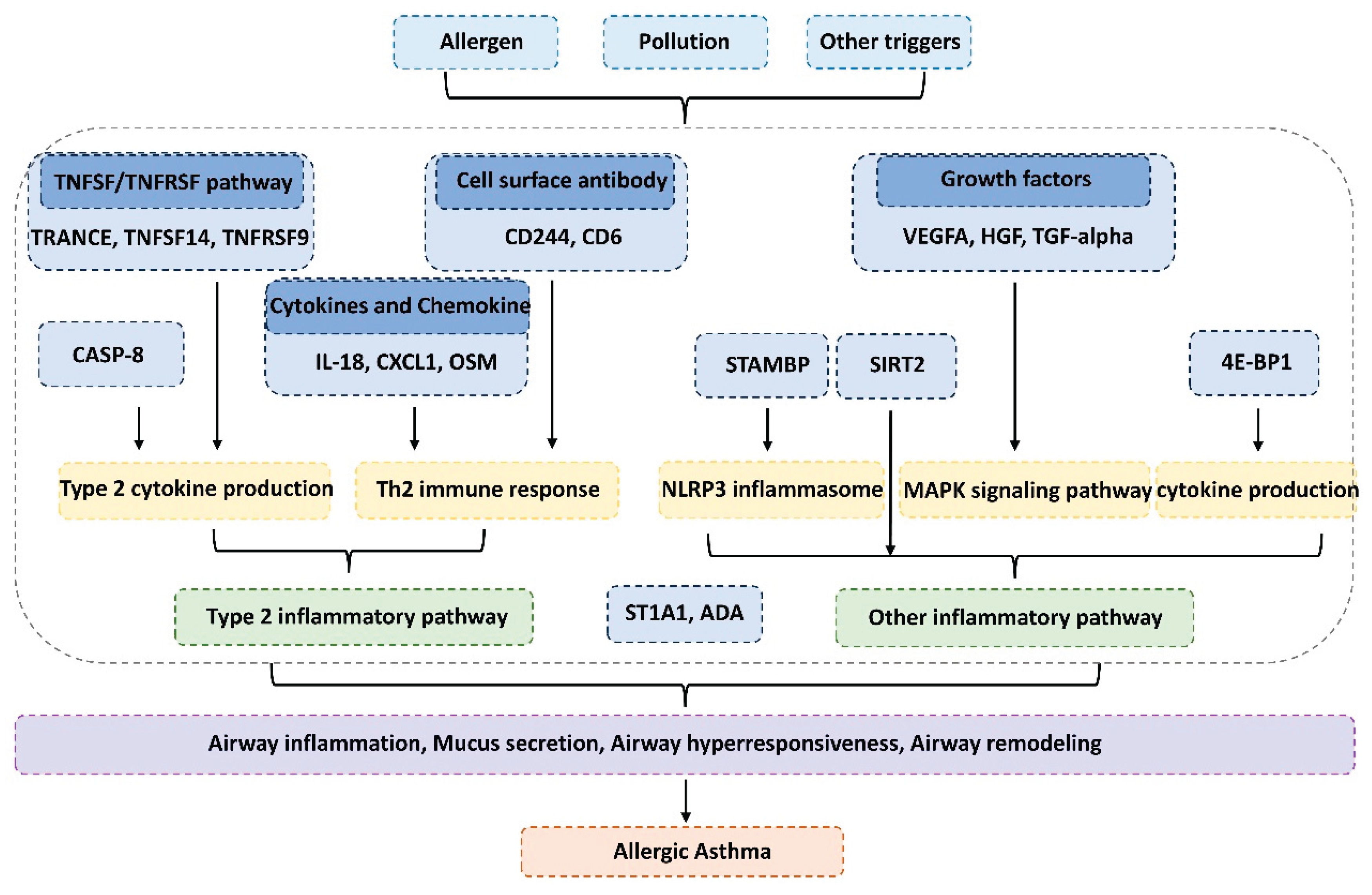

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pandey R, Parkash V, Kant S, Verma AK, Sankhwar SN, Agrawal A, et al. An update on the diagnostic biomarkers for asthma. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2021, 10:1139-1148. [CrossRef]

- Kaur R, Chupp G. Phenotypes and endotypes of adult asthma: Moving toward precision medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 144:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Tiotiu A. Biomarkers in asthma: state of the art. Asthma Research and Practice 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Stewart E, Wang X, Chupp GL, Montgomery RR. Profiling cellular heterogeneity in asthma with single cell multiparameter CyTOF. J Leukoc Biol 2020, 108:1555-1564. [CrossRef]

- Barnes PJ. Targeting cytokines to treat asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 2018, 18:454-466. [CrossRef]

- Anand, M.P. Unveiling Asthma’s Complex Tapestry: Insights from Diverse Perspectives. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2798. [CrossRef]

- Guida G, Bagnasco D, Carriero V, Bertolini F, Ricciardolo FLM, Nicola S, et al. Critical evaluation of asthma biomarkers in clinical practice. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pasha MA, Hopp RJ, Habib N, Tang DD. Biomarkers in asthma, potential for therapeutic intervention. J Asthma 2024, 61:1376-1391. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki A, Okazaki R, Harada T. Neutrophils and Asthma. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1175. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Lin J, Li Z, Wang M. In what area of biology has a “new” type of cell death been discovered? BBA - Reviews on Cancer 2023, 1878. [CrossRef]

- Popović-Grle S, Štajduhar A, Lampalo M, Rnjak D. Biomarkers in Different Asthma Phenotypes. Genes 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Januskevicius A, Vasyle E, Rimkunas A, Malakauskas K. Integrative Cross-Talk in Asthma: Unraveling the Complex Interactions Between Eosinophils, Immune, and Structural Cells in the Airway Microenvironment. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2448. [CrossRef]

- Szefler SJ, Wenzel S, Brown R, Erzurum SC, Fahy JV, Hamilton RG, et al. Asthma outcomes: Biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:S9-S23. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal N, Kraft M. Novel biomarkers in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dostert C, Grusdat M, Letellier E, Brenner D. The TNF Family of Ligands and Receptors: Communication Modules in the Immune System and Beyond. Physiol Rev 2019, 99:115-160. [CrossRef]

- de Groot AF, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, van der Burg SH, Kroep JR. The anti-tumor effect of RANKL inhibition in malignant solid tumors – A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2018, 62:18-28. [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama T, Salter BM, Emami Fard N, Machida K, Sehmi R. TNF Superfamily and ILC2 Activation in Asthma. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kaur D, Chachi L, Gomez E, Sylvius N, Brightling CE. Interleukin-18, IL-18 binding protein and IL-18 receptor expression in asthma: a hypothesis showing IL-18 promotes epithelial cell differentiation. Clin Transl Immunology 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Thawanaphong S, Nair A, Volfson E, Nair P, Mukherjee M. IL-18 biology in severe asthma. Front Med 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Xu M-H, Yuan F-L, Wang S-J, Xu H-Y, Li C-W, Tong X. Association of interleukin-18 and asthma. Inflammation 2016, 40:324-327. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Gao Y, Ding P, Wu T, Ji G. The role of CXCL family members in different diseases. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Woo YD, Koh J, Kang H-R, Kim HY, Chung DH. The invariant natural killer T cell–mediated chemokine X-C motif chemokine ligand 1–X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 axis promotes allergic airway hyperresponsiveness by recruiting CD103+ dendritic cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 142:1781-1792.e1712. [CrossRef]

- Headland SE, Dengler HS, Xu D, Teng G, Everett C, Ratsimandresy RA, et al. Oncostatin M expression induced by bacterial triggers drives airway inflammatory and mucus secretion in severe asthma. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14:eabf8188. [CrossRef]

- Esnault S, Bernau K, Floerke HL, Dendooven A, Delaunay E, Dill-McFarland KA, et al. Oncostatin-M Is Produced by Human Eosinophils and Expression Is Increased in Uncontrolled Severe Asthma. Allergy 2024, 80:1154-1157. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar RS, Minai-Fleminger Y, Seaf M, Gutgold A, Shikotra A, Barber C, et al. CD48 on blood leukocytes and in serum of asthma patients varies with severity. Allergy 2016, 72:888-895. [CrossRef]

- Branicka O, Jura-Szołtys E, Rogala B, Glück J. sCD48 is elevated in non-allergic but not in allergic persistent rhinitis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2021, 43:724-730. [CrossRef]

- McArdel SL, Terhorst C, Sharpe AH. Roles of CD48 in regulating immunity and tolerance. Clin Immunol 2016, 164:10-20. [CrossRef]

- A E El-Shazly, M Henket, P P Lefebvre, R Louis. 2B4 (CD244) is involved in eosinophil adhesion and chemotaxis, and its surface expression is increased in allergic rhinitis after challenge. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2011, 24(4):949-60. [CrossRef]

- Henriques SN, Oliveira L, Santos RF, Carmo AM. CD6-mediated inhibition of T cell activation via modulation of Ras. Cell Commun Signal 2022, 20. [CrossRef]

- Semitekolou M, Xanthou G. Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule: A Novel Regulator of Allergic Inflammation in the Airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 197:973-975. [CrossRef]

- Gomułka K, Liebhart J, Lange A, Mędrala W. Vascular endothelial growth factor-activated basophils in asthmatics. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2020, 37:584-589. [CrossRef]

- Kim J-H. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor as a marker of asthma exacerbation. Korean J Intern Med 2017, 32:258-260. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Miao X, Zhu L, Liu J, lin Y, Xiang G, et al. Autocrine TGF-alpha is associated with Benzo(a)pyrene-induced mucus production and MUC5AC expression during allergic asthma. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2022, 241. [CrossRef]

- Fang Q, Wu W, Xiao Z, Zeng D, Liang R, Wang J, et al. Gingival-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate allergic asthma inflammation via HGF in animal models. iScience 2024, 27. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi Y, Ueki S, Konno Y, Ito W, Takeda M, Nakamura Y, et al. The effect of hepatocyte growth factor on secretory functions in human eosinophils. Cytokine 2016, 88:45-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Zhu C, Liao Y, Zhou M, Xu W, Zou Z. Caspase-8 in inflammatory diseases: a potential therapeutic target. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Pang J, Vince JE. The role of caspase-8 in inflammatory signalling and pyroptotic cell death. Semin Immunol 2023, 70. [CrossRef]

- Brusilovsky M, Rochman M, Rochman Y, Caldwell JM, Mack LE, Felton JM, et al. Environmental allergens trigger type 2 inflammation through ripoptosome activation. Nat Immunol 2021, 22:1316-1326. [CrossRef]

- Qi X, Gurung P, Malireddi RKS, Karmaus PWF, Sharma D, Vogel P, et al. Critical role of caspase-8-mediated IL-1 signaling in promoting Th2 responses during asthma pathogenesis. Mucosal Immunol 2017, 10:128-138. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Zhou T, Pan G, He J, et al. STAMBP is Required for Long-Term Maintenance of Neural Progenitor Cells Derived from hESCs. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2024, 20:1932-1943. [CrossRef]

- Bednash JS, Johns F, Patel N, Smail TR, Londino JD, Mallampalli RK. The deubiquitinase STAMBP modulates cytokine secretion through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell Signal 2021, 79. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yang J, Hong T, Chen X, Cui L. SIRT2: Controversy and multiple roles in disease and physiology. Ageing Res Rev 2019, 55. [CrossRef]

- Lee YG, Reader BF, Herman D, Streicher A, Englert JA, Ziegler M, et al. Sirtuin 2 enhances allergic asthmatic inflammation. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Shi G. Roles of sirtuins in asthma. Respir Res 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Qin X, Jiang B, Zhang Y. 4E-BP1, a multifactor regulated multifunctional protein. Cell Cycle 2016 15:781-786. [CrossRef]

- William M, Leroux L-P, Chaparro V, Lorent J, Graber TE, M’Boutchou M-N, et al. eIF4E-Binding Proteins 1 and 2 Limit Macrophage Anti-Inflammatory Responses through Translational Repression of IL-10 and Cyclooxygenase-2. J Immunol 2018, 200:4102-4116. [CrossRef]

- Isvoran A, Peng Y, Ceauranu S, Schmidt L, Nicot AB, Miteva MA. Pharmacogenetics of human sulfotransferases and impact of amino acid exchange on Phase II drug metabolism. Drug Discov Today 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Sharma J, Menon BK, Vijayan VK, Bansal SK. Changes in Adenosine Metabolism in Asthma. A Study on Adenosine, 5’-NT, Adenosine Deaminase and Its Isoenzyme Levels in Serum, Lymphocytes and Erythrocytes. Open J Respir Dis 2015, 05:33-49. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Allergic asthma (n=10) | Non-allergic asthma (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male/Female) | 7/3 | 3/12 |

| Female (%) | 30% | 80% |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 53.0 ± 20.6 | 63.7 ± 13.6 |

| Neutrophil (%) (mean ± SD) | 60.2 ± 10.1 | 74.8 ± 12.5 |

| Eosinophil (%) (mean ± SD) | 7.61 ± 8.87 | 1.52 ± 1.71 |

| Allergen-specific IgE (KU/L) (mean ± SD) | 657.8 ± 474.4 | 191.8 ± 164.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).