Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multi-Criteria Decision Making/Aiding

2.2. Data Acquisition

- — normalized value of criterion for alternative i

- — original (raw) value for alternative i

- — maximum value across all alternatives

2.3. Criteria Preparation

2.3.1. State Level

2.3.2. LGA Level

- Road Access. These data were obtained from the geoBoundaries open database [46]. Using these data [47], each LGA was analyzed for the presence of major roads (e.g., highways, motorways, expressways). The goal was to identify at least two roads to ensure alternative routing options. If a suitable major road was found within the LGA, a value of "1" was assigned to its row. If no such road was found, neighboring LGAs were examined. If a major road was found in a neighboring LGA, a value of "2" was assigned instead. This procedure was repeated for all 774 LGAs. The best scenario was when both columns for a given LGA contained a "1", indicating direct access to two major roads. The worst scenario was when no major roads were found within the LGA or its surroundings.

- Shipping Infrastructure Proximity The same administrative data from geoBoundaries was used[47], together with the locations of the ports and the aiports [48,49]. To obtain normalized values, the centroid of each LGA was calculated, and the Euclidean distance to the nearest port and airport in Nigeria was measured.

- Health Infrastructure [50] The national database of healthcare facilities was used to count the number of relevant healthcare centers in each LGA. Facilities not directly involved in vaccine provision, such as research institutes, teaching hospitals, and veterinary clinics, were excluded.

- Population Density [36] Population density, calculated as the number of people per square kilometer, was included as a standalone criterion due to its direct relevance to service coverage and demand.

- Vaccine-Preventable Cases [51] Some disease data, such as AFP (no vaccine for some diseases causing it) or cholera (only mid-term immunization), were excluded from our criteria. We considered only conditions that are proven to be long-term vaccine-preventable.

- Security Risks [52] was treated as a critical criterion, reflecting the impact of regional instability on project feasibility. The dataset includes reports of serious incidents, such as armed insurgencies, road blockades, and drone attacks, but excludes minor crimes. In high-risk regions, such instability significantly affects the viability of the vaccine distribution infrastructure.

2.3.3. Data Deficits

2.3.4. Weights

- – the normalized weight assigned to the ranked criterion,

- n – total number of criteria,

- – the rank position of the criterion (with being the most important),

- k – index of summation from j to n.

2.3.5. Thresholds

3. Results and Discussion

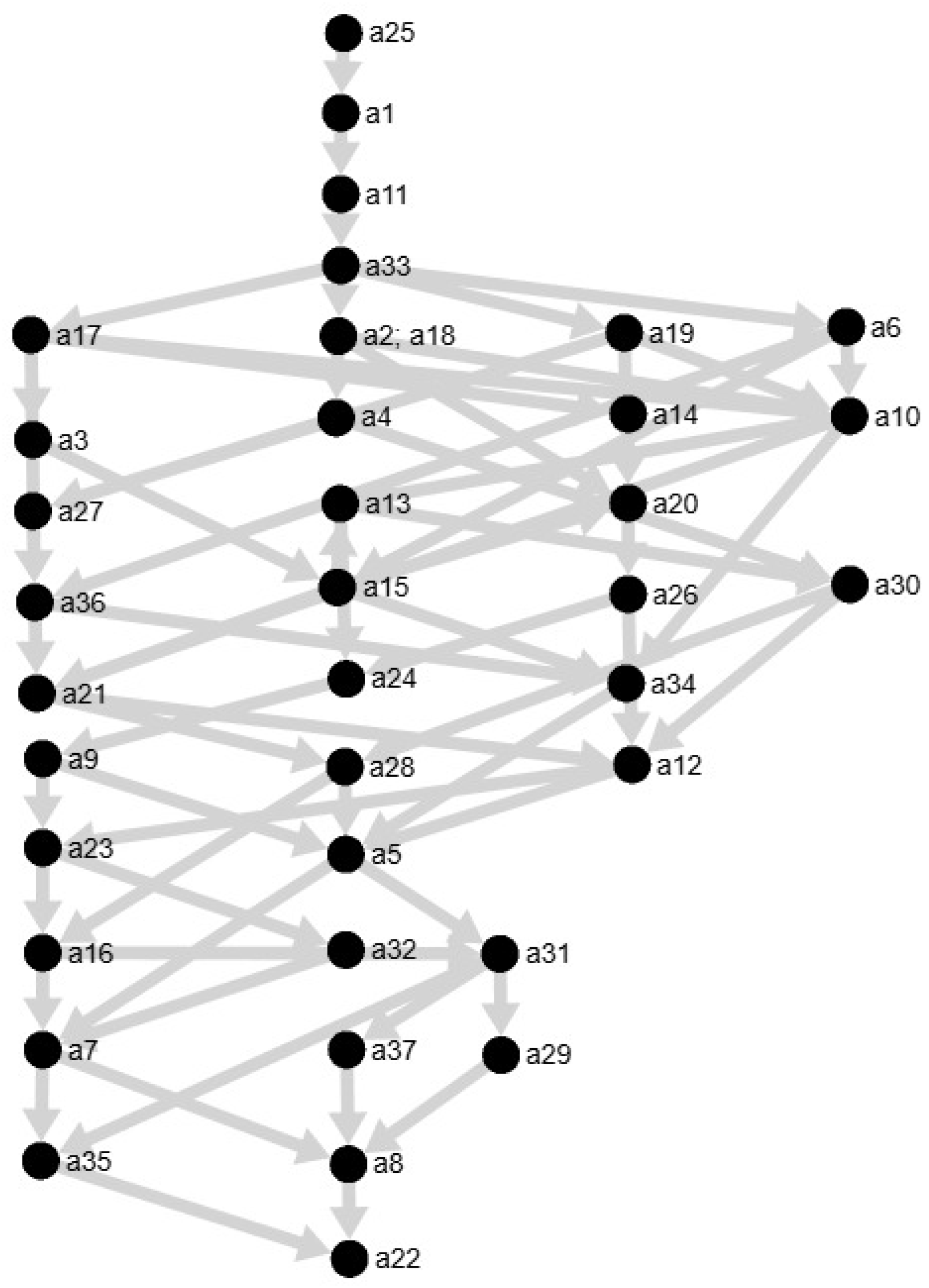

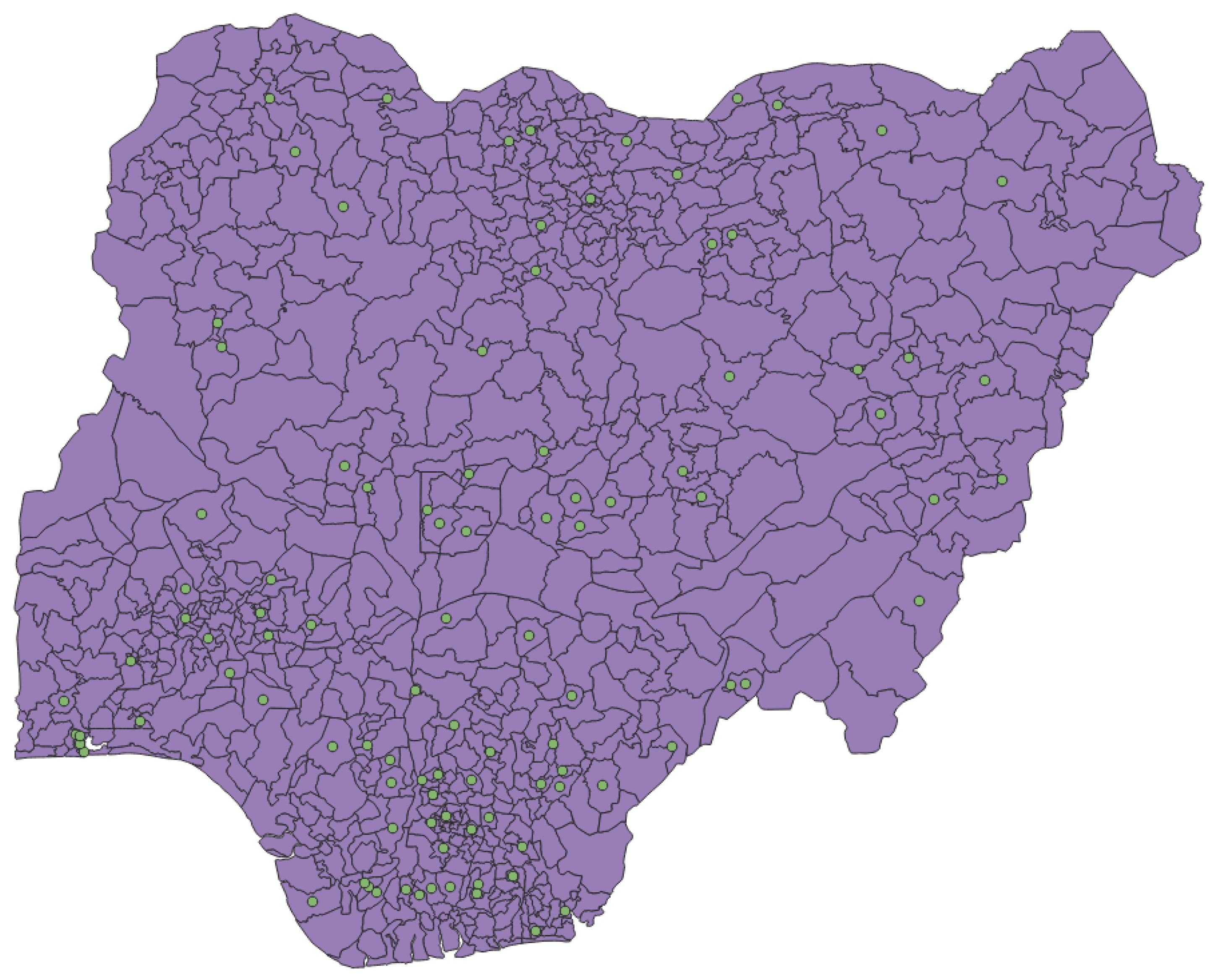

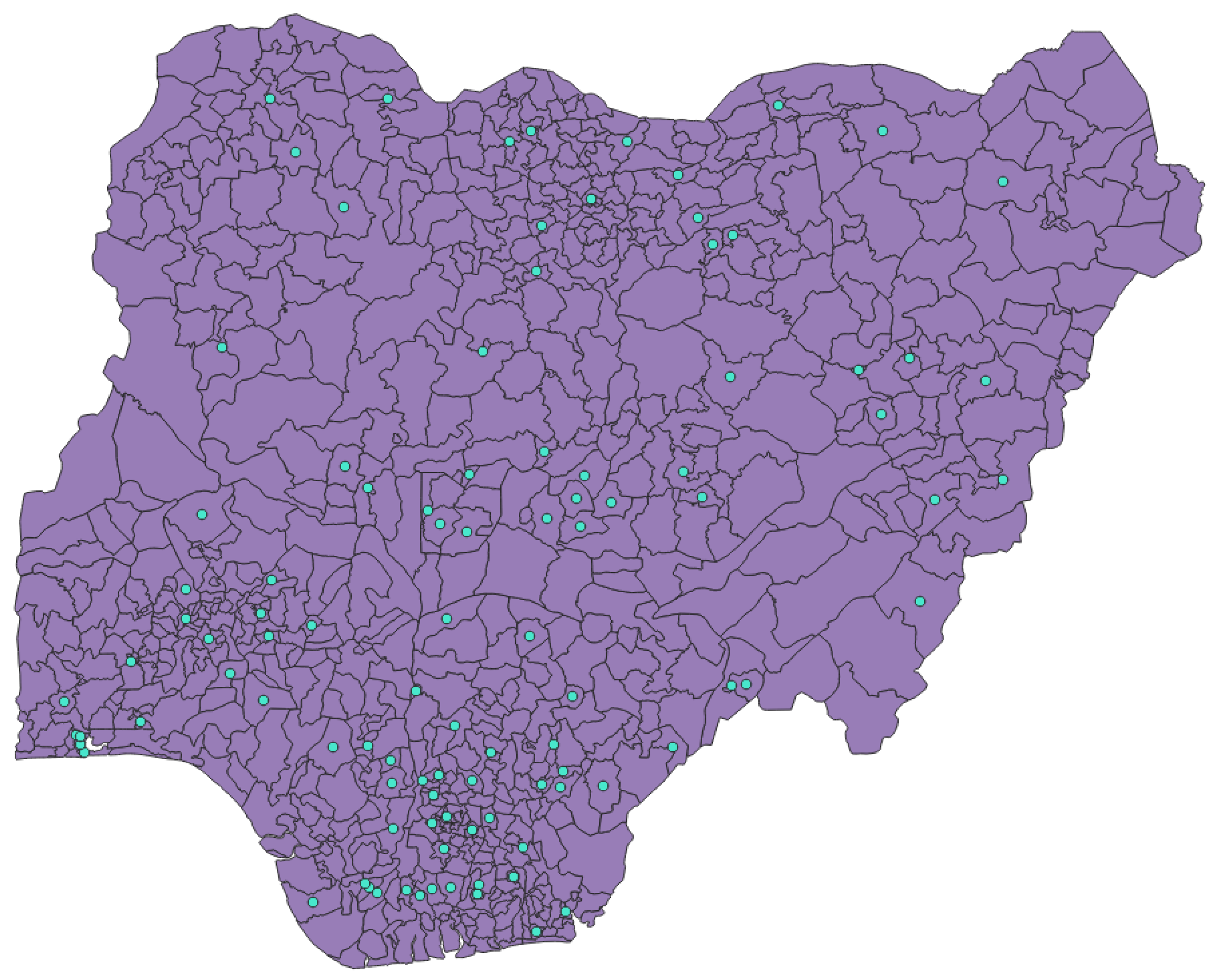

3.1. State Level Distribution

- A fairness rule: each state must receive at least one center.

- A needs-based rule: the remaining 63 centers are distributed according to ELECTRE III results.

- A capacity constraint: no state can get more than 4 centers.

- Kaduna and Jigawa States receive 3 centers under Method 1, but 4 in Method 2 — indicating that a needs-only approach would heavily favor them, possibly at the expense of spatial equity.

- Yobe State is also impacted, method 2 placed 1 center less in it. This is an even more significant difference due to the lower spread of centers in the north-eastern part of Nigeria (which Yobe State is a part of) compared to the rest of the country.

- Kebbi State stands out with the largest relative reduction: 2 centers in Method 1 vs. just 1 in Method 2 — a 50% cut. Such a reduction may severely affect service coverage in a sparsely populated region, such as Kebbi State.

- All other states have consistent results through both methods, confirming an adequate level of prioritization in these.

3.2. LGA Level Distribution

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MINLP | Multi-objective mixed-integer nonlinear programming |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear programming |

| MCLP | Maximal Covering Location Problem |

| SEIRD | Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Recovered, Deceased |

| MCDM/A | Multi-Criteria Decision Making/Aiding |

| FCT | Federal Capital Territory |

| LGA | Local Government Area |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| AFP | Acute Flaccid Paralysis |

References

- Okesanya, O.; Olatunji, G.; Olaleke, N.; Mercy, M.; Ilesanmi, A.; Kayode, H.; Manirambona, E.; Ahmed, M.; Ukoaka, B.; Lucero-Prisno III, D. Advancing Immunization in Africa: Overcoming Challenges to Achieve the 2030 Global Immunization Targets. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 2024, Volume 15, 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Mihigo, R.; Okeibunor, J.; Anya, B.; Mkanda, P.; Zawaira, F. Challenges of immunization in the African Region. The Pan African medical journal 2017, 27, 12. [CrossRef]

- D, N. Routine immunization services in Africa: back to basics. Journal of Vaccines & Immunization 2013, 1, 6–12. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, R.O.f.A. Key lessons from Africa’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout, 2021.

- United Nations. 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Preamble. Technical report, United Nations, 2015.

- Sarley, D.; Mahmud, M.; Idris, J.; Osunkiyesi, M.; Dibosa-Osadolor, O.; Okebukola, P.; Wiwa, O. Transforming vaccines supply chains in Nigeria. Vaccine 2017, 35. [CrossRef]

- Utazi, C.E.; Olowe, I.D.; Chan, H.M.; Dotse-Gborgbortsi, W.; Wagai, J.; Umar, J.A.; Etamesor, S.; Atuhaire, B.; Fafunmi, B.; Crawford, J.; et al. Geospatial Variation in Vaccination Coverage and Zero-Dose Prevalence at the District, Ward and Health Facility Levels Before and After a Measles Vaccination Campaign in Nigeria. Vaccines 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Vahdani, B.; Mohammadi, M.; Thevenin, S.; Gendreau, M.; Dolgui, A.; Meyer, P. Fair-split distribution of multi-dose vaccines with prioritized age groups and dynamic demand: The case study of COVID-19. European Journal of Operational Research 2023, 310, 1249–1272. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bidkhori, H.; Rajgopal, J. Optimizing vaccine distribution networks in low and middle-income countries. Omega (United Kingdom) 2021, 99. [CrossRef]

- Bozorgi, A.; Fahimnia, B. Transforming the vaccine supply chain in Australia: Opportunities and challenges. Vaccine 2021, 39. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.Y.; Haidari, L.A.; Prosser, W.; Connor, D.L.; Bechtel, R.; Dipuve, A.; Kassim, H.; Khanlawia, B.; Brown, S.T. Re-designing the Mozambique vaccine supply chain to improve access to vaccines. Vaccine 2016, 34. [CrossRef]

- Prosser, W.; Spisak, C.; Hatch, B.; McCord, J.; Tien, M.; Roche, G. Designing supply chains to meet the growing need of vaccines: evidence from four countries. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Adida, E.; Dey, D.; Mamani, H. Operational issues and network effects in vaccine markets. European Journal of Operational Research 2013, 231. [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, M.; Tavana, M.; Meraj, A.; Mina, H. An inventory-location optimization model for equitable influenza vaccine distribution in developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 2021, 39. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, S.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z. Locate vaccination stations considering travel distance, operational cost, and work schedule. Omega (United Kingdom) 2021, 101. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Claypool, E.; Norman, B.A.; Rajgopal, J. Coverage models to determine outreach vaccination center locations in low and middle income countries. Operations Research for Health Care 2016, 9, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Miura, F.; Leung, K.Y.; Klinkenberg, D.; Ainslie, K.E.; Wallinga, J. Optimal vaccine allocation for COVID-19 in the Netherlands: A data-driven prioritization. PLoS Computational Biology 2021, 17. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Dutta, R.; Ghosh, P. Optimal time-varying vaccine allocation amid pandemics with uncertain immunity ratios. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 15110–15121. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Raut, R.D.; Rofin, T.M.; Chakraborty, S. A comprehensive and systematic review of multi-criteria decision-making methods and applications in healthcare, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Undermind AI. Undermind – Research co-pilot for experts, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.undermind.ai/.

- Aina, M.; Igbokwe, U.; Jegede, L.; Fagge, R.; Thompson, A.; Mahmoud, N. Preliminary results from direct-to-facility vaccine deliveries in Kano, Nigeria. Vaccine 2017, 35. [CrossRef]

- Roy, B. The outranking approach and the foundations of electre methods. Theory and Decision 1991, 31, 49–73. [CrossRef]

- Zak, J. The application of the multiple criteria decision making/aiding methodology to evaluation and redesign of logistics systems. Decision Making in Manufacturing and Services 2019, 13, 33–54. [CrossRef]

- Free Software Foundation. GNU General Public License, Version 3. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.html, 2007.

- Taherdoost, H.; Madanchian, M. A Comprehensive Overview of the ELECTRE Method in Multi Criteria Decision-Making. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- Zak, J. Multiple-Criteria and Group-Decision Making in the Fleet Selection Problem for a Public Transportation System. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia. Elsevier B.V., 2017, Vol. 27, pp. 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Ba̧czkiewicz, A.; Watrobski, J.; Sałabun, W. Towards MCDA Based Decision Support System Addressing Sustainable Assessment. Isd 2021.

- Pereira, V.; Dias, L.; Nepomuceno, O. J-ELECTRE v3.0 User Guide. Technical report, 2021.

- Figueira, J.; Mousseau, V.; Roy, B., Electre Methods. In Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer-Verlag, 2005; p. 133–153. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, E. A method for multiple pseudo-criteria decision problems. Computers & Operations Research 2001, 28, 1427–1439. [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Kadziński, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Słowiński, R. How to support the application of multiple criteria decision analysis? Let us start with a comprehensive taxonomy. Omega 2020, 96, 102261. [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, A.; Moussiopoulos, N. Application of ELECTRE III for the integrated management of municipal solid wastes in the Greater Athens Area. European Journal of Operational Research 1997, 97, 439–449. [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Madanchian, M. A Comprehensive Overview of the ELECTRE Method in Multi Criteria Decision-Making. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research 2023, 6, 5–16. [CrossRef]

- Gdowska, K.; Łygas, J. Multicriteria-Based Vaccine Distribution Center Planning in Nigeria Using ELECTRE III. RODBUK Cracow Open Research Data Repository 2025. [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, N.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Normalization techniques for multi-criteria decision making: Analytical hierarchy process case study. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 2016, Vol. 470. [CrossRef]

- Frommert, Holger. Geo-Ref Nigeria Administrative Data, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.geo-ref.net/en/nga.htm.

- Open Data for Africa. Open Data for Africa - Nigeria Portal, n.d. Retrieved from https://nigeria.opendataforafrica.org/.

- Gabriel Okeowo, I.F. State of States Report 2022, 2022. Retrieved from https://stateofstates.budgit.org/ reports/details?year=2022.

- National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria. National Bureau of Statistics - Report 1093, 2024-10-24. Retrieved from https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/1093.

- National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria. National Bureau of Statistics - Report 1123, n.d. Retrieved from https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/1123.

- Ohiare, S. Expanding electricity access to all in Nigeria: a spatial planning and cost analysis, 2015. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Nigeria Power Plants Dataset, 2023. Retrieved from https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/ dataset/0042336/Nigeria-Power-Plants.

- Oluseun Onigbinde, Vahyala Kwaga, E.O. State of States Report 2024, 2024. Retrieved from https://stateofstates.budgit.org/reports/details?year=2024.

- UNDP Nigeria.; National Bureau of Statistics. Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index 2022, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/nigeria/publications/nigeria-multidimensional-poverty-index-2022.

- Central Bank of Nigeria. CBN Statistical Bulletin, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/ Statbulletin.html.

- Runfola, D.; Anderson, A.; Baier, H.; Crittenden, M.; Dowker, E.; Fuhrig, S.; Goodman, S.; Grimsley, G.; Layko, R.; Melville, G.; et al. geoBoundaries: A global database of political administrative boundaries. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0231866. [CrossRef]

- GRID3. Nigeria - Local Government Area Boundaries (ADM2). https://data.grid3.org/datasets/grid3-nigeria-local-government-area-boundaries-1/explore?location=8.959048%2C8.685290%2C6.61, 2023. ISO-3166-1 (Alpha-3): NGA; Representative Year: 2022; Boundary Type: ADM2; Number of Units: 774; License: CC BY 4.0.

- Nigerian Ports Authority. Nigerian Ports Authority Official Website, n.d. Retrieved from https://nigerianports.gov.ng/.

- Okeke-Korieocha, I. Eight of 13 Nigerian Cargo Airports Inactive, 2022. Retrieved from https://businessday.ng/big-read/article/eight-of-13-nigerian-cargo-airports-inactive/.

- eHealth Africa. Nigeria Health Care Facilities (Primary, Secondary and Tertiary). https://gis-geonetwork.ehealthafrica.org/geonetwork/srv/en//metadata.show?uuid=e297dd24-1a09-42ac-b332-de07fd2a66d0, 2017. Spatial extent: 7.14°E–7.99°E, 4.82°N–6.04°N. Temporal extent: 2017-11-01 to 2018-12-31. Last updated: 2020-10-06.

- UNICEF Nigeria.; NEMA. NCDC EPIDEMICS DATA 2018 NATIONAL - UNICEF/NEMA Repository, 2024. Retrieved from https://nema-data-repository-unicef.hub.arcgis.com/documents/eb23ef00239f4b6293d82 adf6c170b28/about.

- UNICEF Nigeria.; NEMA. NGA 2024 Acled - UNICEF/NEMA Repository, 2024-10-24. Retrieved from https://nema-data-repository-unicef.hub.arcgis.com/datasets/dc7bd179b61e44539375e48746b1d282/about.

- Roszkowska, E. Rank Ordering Criteria Weighting Methods – a Comparative Overview. Optimum. Studia Ekonomiczne 2013. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.; Bruen, M. Choosing realistic values of indifference, preference and veto thresholds for use with environmental criteria within ELECTRE. European Journal of Operational Research 1998, 107. [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System: Documentation. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project, 2024. Retrieved from https://www.qgis.org/resources/hub/#documentation.

| Type of criteria | Formula |

|---|---|

| Benefit | |

| Cost |

| Name of Criterion | Administrative Level | Criterion Type |

|---|---|---|

| Population Density | State | Benefit |

| Awareness and Water Access | State | Benefit |

| Health System Potential | State | Benefit |

| Electricity Access | State | Benefit |

| Economic Capacity | State | Benefit |

| Healthcare Disadvantages | State | Benefit |

| Road Access | LGA | Benefit |

| Shipping Infrastructure Proximity | LGA | Cost |

| Health Infrastructure | LGA | Benefit |

| Population Density | LGA | Benefit |

| Vaccine-Preventable Cases | LGA | Benefit |

| Security Risks | LGA | Cost |

| Combined Criterion | Componential Criteria | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness and Water Access | Citizens using improved sources of water [%] [37] Citizens literate [%] [37] Citizens who have heard of AIDS [%] [37] |

These criteria reflect general health awareness and access to basic needs. |

| Health System Potential | Health Spendings per Capita [₦] [38] Infant mortality (per 1000 births) [37] Population below the poverty line [%] [39] |

This group assesses both the quality of existing healthcare and the regional population’s needs. |

| Electricity Access | Access to Electricity [%] [40] Access to National Grid [%] [41] Sum of MW per 100,000 citizens [42] |

Cross-referencing these criteria exemplifies each region’s electrical capabilities. |

| Economic Capacity | GDP per capita [₦] [38] Fiscal performance rank [43] Unemployment Rate [%] [44] Domestic debt of state [₦ Billion] [45] |

These show the region’s stability and sustainability regarding more demanding infrastructural projects. |

| Healthcare Disadvantages | Reasons for not accessing any health facility [%] [40] Too expensive [%] Poor quality of care [%] |

This group highlights barriers that prevent people from using healthcare services in Nigeria. |

| Criterion | Importance | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| State level | ||

| Population Density | 1 | 0.41 |

| Economic Capacity | 2 | 0.24 |

| Electricity Access | 3 | 0.16 |

| Health System Potential | 4 | 0.10 |

| Healthcare Disadvantages | 5 | 0.06 |

| Awareness and Water Access | 6 | 0.03 |

| LGA level | ||

| Health Infrastructure | 1 | 0.41 |

| Population Density | 2 | 0.24 |

| Security Risks | 3 | 0.16 |

| Road Access | 4 | 0.10 |

| Vaccine-Preventable Cases | 5 | 0.06 |

| Shipping Infrastructure Proximity | 6 | 0.03 |

| Threshold | Formula used |

|---|---|

| q | |

| p | |

| v |

| Threshold Symbol |

Population Density |

Awareness and Water Access |

Health System Potential |

Electricity Access |

Economic Capacity |

Healthcare Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| p | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| v | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.37 |

| Threshold Symbol |

Road Access |

Shipping Infrastructure Proximity |

Health Infrastructure |

Population Density |

Vaccine-Preventable Cases |

Security Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| p | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| v | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| State name | State ID | Ascend. | Descend. | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abia | a1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Adamawa | a2 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 |

| Akwa Ibom | a3 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 8.5 |

| Anambra | a4 | 3.0 | 17.0 | 10.0 |

| Bauchi | a5 | 19.0 | 25.0 | 22.0 |

| Bayelsa | a6 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 |

| Benue | a7 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| Borno | a8 | 25.0 | 29.0 | 27.0 |

| Cross River | a9 | 18.0 | 16.0 | 17.0 |

| Delta | a10 | 9.0 | 14.0 | 11.5 |

| Ebonyi | a11 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Edo | a12 | 16.0 | 21.0 | 18.5 |

| Ekiti | a13 | 12.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 |

| Enugu | a14 | 13.0 | 6.0 | 9.5 |

| FCT | a15 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.5 |

| Gombe | a16 | 20.0 | 24.0 | 22.0 |

| Imo | a17 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| Jigawa | a18 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 |

| Kaduna | a19 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| Kano | a20 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 |

| Katsina | a21 | 11.0 | 21.0 | 16.0 |

| Kebbi | a22 | 27.0 | 29.0 | 28.0 |

| Kogi | a23 | 20.0 | 22.0 | 21.0 |

| Kwara | a24 | 17.0 | 15.0 | 16.0 |

| Lagos | a25 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Nasarawa | a26 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 |

| Niger | a27 | 5.0 | 19.0 | 12.0 |

| Ogun | a28 | 12.0 | 24.0 | 18.0 |

| Ondo | a29 | 23.0 | 28.0 | 25.5 |

| Osun | a30 | 12.0 | 18.0 | 15.0 |

| Oyo | a31 | 21.0 | 26.0 | 23.5 |

| Plateau | a32 | 24.0 | 23.0 | 23.5 |

| Rivers | a33 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| Sokoto | a34 | 10.0 | 25.0 | 17.5 |

| Taraba | a35 | 26.0 | 27.0 | 26.5 |

| Yobe | a36 | 8.0 | 20.0 | 14.0 |

| Zamfara | a37 | 22.0 | 29.0 | 25.5 |

| State name | Method 1 | Method 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Abia | 4 | 4 |

| Adamawa | 4 | 4 |

| Bayelsa | 4 | 4 |

| Ebonyi | 4 | 4 |

| Imo | 4 | 4 |

| Lagos | 4 | 4 |

| Rivers | 4 | 4 |

| Jigawa | 3 | 4 |

| Kaduna | 3 | 4 |

| Akwa Ibom | 3 | 3 |

| Anambra | 3 | 3 |

| Delta | 3 | 3 |

| Ekiti | 3 | 3 |

| Enugu | 3 | 3 |

| FCT | 3 | 3 |

| Kano | 3 | 3 |

| Nasarawa | 3 | 3 |

| Niger | 3 | 3 |

| Yobe | 3 | 2 |

| Bauchi | 2 | 2 |

| Benue | 2 | 2 |

| Borno | 2 | 2 |

| Cross River | 2 | 2 |

| Edo | 2 | 2 |

| Gombe | 2 | 2 |

| Katsina | 2 | 2 |

| Kogi | 2 | 2 |

| Kwara | 2 | 2 |

| Ogun | 2 | 2 |

| Ondo | 2 | 2 |

| Osun | 2 | 2 |

| Oyo | 2 | 2 |

| Plateau | 2 | 2 |

| Sokoto | 2 | 2 |

| Taraba | 2 | 2 |

| Zamfara | 2 | 2 |

| Kebbi | 2 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).