1. Introduction

Covert channels in computer systems exploit shared resources to transmit information covertly between processes. Traditional cache based covert channels often suffer from low throughput and high error rates due to the unpredictable nature of cache access times and system interference. Covert channels between cross-core sender and receiver processes are more noisy and harder to establish. Earlier investigations by [

1,

2,

3] laid the groundwork for understanding covert channels by analyzing the MESI cache coherence protocol’s effects on last-level caches (LLC). Their approaches primarily relied on accessing a single cache line per bit transmission with normal page size, without incorporating huge pages.

Building upon this foundational research, our method introduces the use of huge pages and facilitates access to multiple cache lines concurrently. This novel approach is designed to enhance both the accuracy and throughput of covert channels, capitalizing on the combined benefits of prefetching and huge pages.

For a cross-core covert channel, the sender and receiver processes are on different cores. Only shared cache between the sender and the receiver is the LLC. Cache coherence events provide a mechanism to signal or encode the data from a receiver to a sender. A sender within a software enclave such as Intel SGX enclave may have access to private data of value to the receiver. All the information channels are typically monitored in a secure domain such as a software enclave [

4,

5,

6,

7] or secure world domain of ARM Trust Zone [

8,

9]. These covert channels avoid such dynamic information channel monitoring to exfiltrate secret data. How such secret data is acquired in the sender domain is not a focus of this paper.

Prefetching plays a critical role in optimizing memory access, but serves to activate specific cache coherence events in covert channels. Prefetchers, through instructions such as PREFETCHW, enable data to be proactively loaded into the L1 cache. This proactive behavior reduces memory access latency, improves cache utilization, and interacts with the MESI (Modified, Exclusive, Shared, Invalid) cache coherence protocol to maintain data consistency across cores. For instance, PREFETCHW can transition cache lines to the Modified state, preparing them for faster subsequent write operations while maintaining coherence. These operations enable side-channel and covert-channel vulnerabilities through observable changes in cache states. Covert channels, by leveraging the interplay between prefetching and cache coherence protocols, can exploit these microarchitectural optimizations to improve their effectiveness.

Huge pages, on the other hand, address memory management challenges by significantly reducing the number of TLB entries required for address translation. With larger page size such as 2 MB or 1 GB, a TLB entry covers a broader range of memory addresses, minimizing TLB misses and reducing address translation overhead. This optimization is particularly effective for memory-intensive applications with spatial locality, as it lowers latency and improves system efficiency by decreasing the frequency of page table walks and translations. Spatial locality also is likely to reduce the page fault frequency further improving performance. Additionally, huge pages are commonly employed in cryptographic systems and secure data transmission to improve performance and predictability when handling secret or sensitive data, making them a natural fit for covert communication channels that rely on timing stability.

The combination of prefetching and huge pages amplifies these individual benefits leading to enhanced covert channel efficiency. Huge pages facilitate more effective prefetchers, enabling data fetching across larger contiguous memory regions with fewer interruptions driven by page faults. This integration ensures faster address translations, higher cache hit rates, and reduced latency, resulting in significantly improved throughput and accuracy in covert channels. Our proposed approach capitalizes on the strengths of prefetching and huge pages to enhance covert channel performance, demonstrating notable improvements in throughput and accuracy while addressing associated challenges in a controlled computing environment.

2. Background

2.1. Software Prefetcher

A software prefetcher is a mechanism that allows a program to explicitly request the fetching of data from memory into the cache before it is accessed. The purpose is to hide memory latency by ensuring that data is already available in the cache when needed by the CPU. Software prefetching is typically initiated by inserting special prefetch instructions (e.g., PREFETCH in x86 or PLD in ARM) into the program code. These instructions act as hints to the processor that specific memory locations will likely be accessed soon, prompting the prefetcher to load the data into the appropriate cache level [

10].

The mechanism of software prefetching involves several steps. First, programmers or compilers strategically place prefetch instructions at points in the code where memory access patterns are predictable, such as in loops that iterate over large datasets. For instance, in a loop processing an array, a prefetch instruction can be placed a few iterations ahead to ensure data is available when needed. Once executed, these instructions trigger the processor to fetch the specified memory location from main memory into the cache. On x86 architectures, instructions like PREFETCHW are used to prepare cache lines for future writes, while PREFETCHT0 brings data into the L1 cache. Similarly, ARM architectures utilize PLD for data prefetching and PLI for prefetching instructions. The fetched data is then stored in a specified cache level, such as L1, L2, or L3, depending on the type of prefetch instruction used. This operation is non-blocking, meaning it does not stall the CPU while waiting for the data to be fetched; the processor continues executing other instructions, allowing the prefetcher to asynchronously load the data into the cache [

11].

Software prefetching can handle both read and write operations. For example, the

__builtin_prefetch instruction in x86 architectures is versatile and explicitly prepares cache lines for future writes by transitioning them to the

modified state within the MESI protocol [

12]. Prefetching does not alter the data itself; it merely ensures that the data is readily available in the cache for subsequent operations, thereby enhancing efficiency without compromising data integrity.

The advantages of software prefetching are significant. It reduces memory latency by preloading data into the cache, thus minimizing delays when the data is accessed. By ensuring frequently accessed data is present in the appropriate cache level, it improves cache utilization and reduces cache misses. This also minimizes pipeline stalls caused by memory access delays, leading to smoother instruction execution. Software prefetching is particularly effective in workloads with predictable access patterns, such as matrix operations prevalent in AI/ML applications, image processing, and large-scale numerical simulations [

13]. By leveraging software prefetching effectively, programmers and compilers can achieve substantial performance gains in memory-intensive applications.

In our baseline tests in

Section 3.2, enabling software prefetching reduced the average memory access latency and provided a performance improvement of approximately 13%.

2.2. Huge Pages

A huge page is a memory management feature in modern operating systems that allows the mapping of large, contiguous memory regions using a single page table entry. Unlike the standard memory page size, which is typically 4 KB, huge pages can have much larger sizes, such as 2 MB or 1 GB, depending on the system architecture and configuration. By mapping larger memory regions with fewer TLB entries, huge pages offer significant performance and efficiency advantages for memory-intensive applications [

14,

15].

The mechanism of huge pages starts with their integration into the virtual memory system. Operating systems allocate memory regions for huge pages by reserving contiguous blocks of physical memory. These regions are then mapped to virtual addresses through page table entries, significantly reducing the number of entries required for large datasets [

16]. For example, a 2 MB huge page replaces 512 standard 4 KB pages in the page table, reducing the frequency of page table walks and address translations.

Huge pages are particularly effective in minimizing Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) misses. The TLB is a hardware cache that stores recently used virtual-to-physical address mappings, and it has a limited number of entries. By using huge pages, a single TLB entry can map a much larger memory region. It reduces the likelihood of TLB misses leading to improved performance. This reduction in TLB pressure is especially advantageous for workloads with large memory footprints, such as databases, high-performance computing (HPC) applications, and virtualization [

17].

Another benefit of huge pages is improved memory access performance. With fewer page table entries and reduced TLB misses, the latency associated with memory access is significantly decreased. This enhancement is critical for memory-intensive tasks that rely on rapid access to large datasets. Additionally, huge pages optimize cache utilization by enabling better spatial locality. Larger contiguous memory mappings align with prefetching and caching mechanisms, ensuring that data is fetched and utilized more efficiently [

18]. This spatial locality also leads to lower page fault rate.

However, huge pages are not without limitations. One significant drawback is the potential for increased memory fragmentation [

19]. Since huge pages require large contiguous memory blocks, their allocation can lead to fragmentation, reducing the availability of smaller memory blocks for other processes. Moreover, managing huge pages can be complex and may require administrative privileges to configure. In some cases, huge pages are "pinned," meaning they cannot be swapped out, which can reduce the flexibility of memory management. Similarly, if the application does not have enough spatial locality to support huge pages, it could lead to significant thrashing degrading the program performance.

Typical applications that leverage huge pages include databases like Oracle and PostgreSQL, which benefit from reduced TLB misses during operations on large datasets [

20]. High-performance computing workloads and virtualization systems also use huge pages to optimize memory access patterns and minimize latency. Similarly, large-scale machine learning and AI applications rely on huge pages to handle their substantial memory requirements efficiently [

16].

For example, on Linux systems, huge pages can be enabled and configured using the hugepages subsystem or libraries like libhugetlbfs. The standard page size of 4 KB can be replaced with 2 MB huge pages (default for x86) or even 1 GB pages, depending on hardware support and system configuration. By enabling huge pages, developers and system administrators can unlock substantial performance improvements for memory-bound applications [

15].

Our baseline evaluation in

Section 3.2 shows that using huge pages reduced the average memory access latency, resulting in a 22% improvement. When combined with software prefetching, the memory latency decreased by 24%, indicating a synergistic effect from both techniques.

2.3. Cache Architecture and Coherence Protocols: MESI

Modern x86 processors feature a hierarchical cache architecture consisting of L1, L2, and L3 caches. The L1 and L2 caches are fast, private to each CPU core, and handle requests rapidly. The L3 cache, or last-level cache (LLC), is shared among cores, slower, and larger, operating on fixed-size data blocks known as cache lines.

Memory access in this hierarchical architecture begins with the CPU checking the L1 data cache for the requested data. If the data is found (a cache hit), it is retrieved rapidly. If the data is not in the L1 cache (a cache miss), the search proceeds to the L2 cache, and subsequently to the L3 cache if necessary. When the data is not available in any cache level, it is fetched from main memory, incurring significant latency. This process highlights the critical role of the cache hierarchy in reducing memory access time and enhancing overall system performance.

Many modern Intel processors use an extension of the MESI protocol such as MESIF for Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-6500 CPU. Cache coherence protocols like MESI (Modified, Exclusive, Shared, Invalid) are crucial for maintaining data consistency across caches in multi-core processors. This protocol helps to ensure that multiple cores can manage shared data without integrity or consistency issues by transitioning cache lines through various states based on access patterns and data ownership changes:

Modified (M): The cache line is present only in one core cache, has been modified (dirty), and is not in sync with the LLC.

Exclusive (E): The cache line is present only in one core cache, has not been modified, and is exclusive to that cache.

Shared (S): The cache line is present in multiple core caches but has not been modified, reflecting uniformity across caches.

Invalid (I): The cache line is not valid in any core cache.

This hierarchical architecture works in tandem with the MESI protocol to optimize both performance and consistency, ensuring efficient data sharing and synchronization across multi-core systems.

2.4. Contention-Based and State-Based Cross-Core Cache Attacks

Contention-based attacks, also known as stateless attacks, involve passively observing the latency in accessing specific cache hardware components, such as the ring interconnect or L1 cache ports, to infer the victim’s activity.

State-based attacks, on the other hand, involve manipulating the state of cache lines or sets. In this type of attack, the attacker deliberately sets the cache to a particular state and allows the victim to operate, potentially altering this state [

2,

3]. The attacker then re-examines the cache to deduce the victim’s actions based on the changes in cache states. State-based attacks are also known as eviction-based or stateful attacks and are more prevalent in research and application of cache based side-channels.

Our focus is on these stateful applications, particularly those that manipulate cache states to infer data transmission or changes due to other processes’ activities.

2.5. Cache Coherence Covert Channels

Covert channels exploit these coherence protocols by manipulating the state of cache lines to create detectable timing variations that can encode and transmit information secretly:

1. State-based Timing Differences: Access times vary significantly based on the state of the cache line. For instance, a line in the ’Modified’ state in one core’s cache being read by another core will result in longer latency as the line must be fetched from the owning core’s cache and updated in the LLC and the requesting core’s cache.

2. Prefetching and Coherence State Manipulation: Prefetch instructions (e.g., PREFETCHW) are used to deliberately alter the state of a cache line. This instruction can prefetch data into a cache and set it to ’Modified’, preparing it for faster subsequent write operations but also changing the coherence state detectably, which can be exploited in a covert channel to signal a ’1’ or ’0’ based on whether the prefetch operation took longer (indicating a state change) or shorter (indicating no state change).

3. Design of Multi-Line Prefetch Covert Channel with Huge Pages

3.1. Overview of the Multi-Line Prefetch Attack Implementation

The multi-line prefetch covert channel represents an advanced microarchitectural technique leveraging the timing behavior of the PREFETCHW instruction to establish covert channel communication. This enhanced implementation significantly extends the capabilities of the original attack [

1] by introducing multi-line encoding and decoding, enabling higher bandwidth and more flexible communication compared to the original approach, which could only encode a single bit of information per iteration.

We assume that the two essential parties in the attack, the sender and the receiver, are two unprivileged processes running on the same processor with multiple CPU cores. The sender and receiver can be launched on separate physical cores using tools such as taskset. Furthermore, these processes can share data, such as through shared libraries or page deduplication. This setup mirrors prior attacks, ensuring shared memory access while maintaining isolation between processes. Additionally, the sender and receiver must agree on predefined channel protocols, including synchronization mechanisms, core allocation, data encoding, and error correction protocols. These agreements are critical for maintaining the consistency and accuracy of the covert channel.

When huge pages are enabled, the multi-line prefetch covert channel gains significant advantages, particularly in scenarios involving n cache lines. Huge pages reduce TLB misses by mapping larger memory regions with fewer entries, enabling the prefetcher to operate more efficiently. This optimization allows the sender to access multiple cache lines within the same page, reducing latency and improving throughput. The larger contiguous memory provided by huge pages enhances the precision of timing measurements, leading to better accuracy and reduced error rates. Furthermore, the combination of huge pages and multi-line prefetching ensures that more data can be encoded and decoded in fewer iterations, thereby increasing the bandwidth and stealth of the attack.

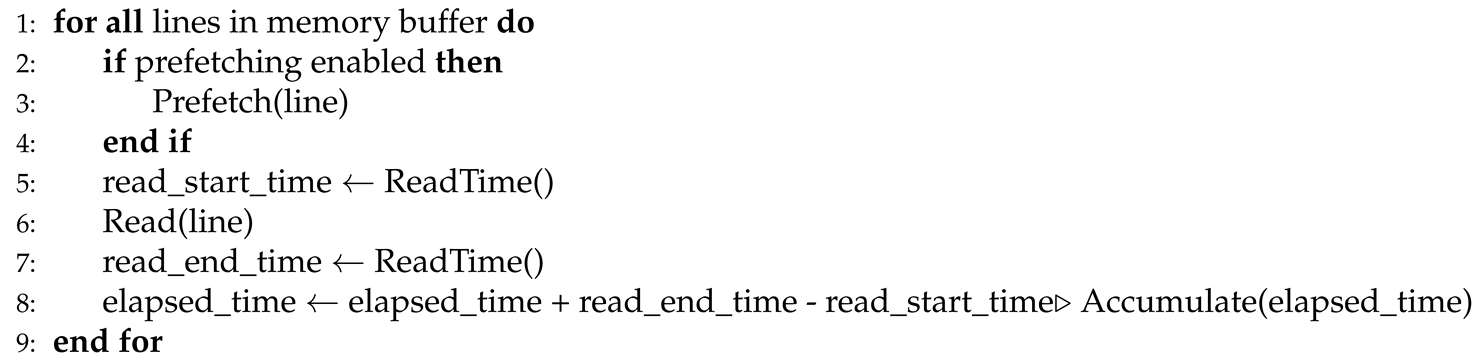

3.2. Baseline Performance Comparison with Prefetching and Huge Pages

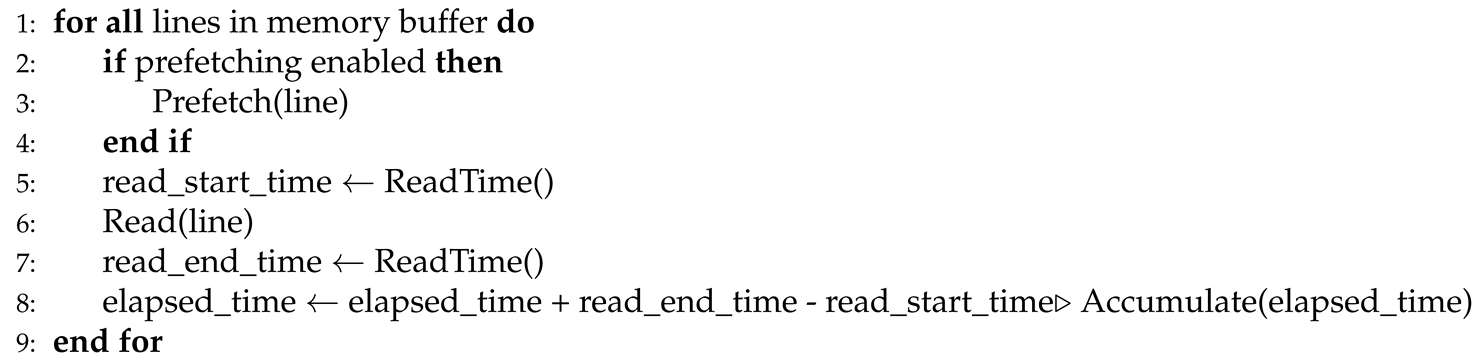

To establish a baseline for evaluating the performance impact of huge pages and software prefetching, we measure the average memory access latency over a 32 KB region (comprising 512 cache lines, each 64 bytes in size). As shown in Algorithm 1, we test four configurations: with and without huge pages, and with and without software prefetching. The resulting latency measurements are summarized in

Table 1.

|

Algorithm 1 Timing Measurement per Cache Line |

|

Huge Pages Only: Enabling huge pages alone reduces the average access latency by approximately 22% compared to the baseline. This is primarily due to the reduced TLB pressure and improved memory translation efficiency provided by 2MB page mappings.

Prefetching Only: Applying software prefetching without huge pages results in a 13% latency reduction. The prefetch instruction (__builtin_prefetch()) helps bring the cache lines closer to the processor ahead of access, thereby reducing stalls.

Combined Optimization: The combination of huge pages and prefetching yields the lowest average latency (1.88 cycles). This configuration effectively leverages both reduced TLB pressure from huge pages and improved cache readiness from prefetching, making it the most efficient strategy for minimizing access latency in our setup.

3.3. Setup and Configuration

System Configuration: We utilize a local machine with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-6500 CPU operating at maximum clock speed of 3.60GHz with Ubuntu 24.04 OS. The system supports prefetching and utilizing huge pages, enhancing performance and memory management capabilities.

Software Environment: We develop sender and receiver programs that operate on the same physical machine to eliminate external interference. The programs are implemented in C using compiler-supported prefetching instructions, such as __builtin_prefetch in GCC, to manipulate cache states.

Huge Pages Setup: To enhance memory access patterns and overall performance, we configured the system to use 2MB huge pages by enabling the Linux hugepages subsystem. This included resizing the shared file to 2MB, updating the mmap system call with the MAP_HUGETLB flag to allocate memory backed by huge pages, and mounting the hugetlbfs filesystem to support these allocations.

3.4. Multi-Line Encoding for Flexible Communication

In this improved implementation, messages are encoded by selectively accessing n cache lines during each iteration, leading to bit transmissions. Each accessed cache line contents do not matter. It is the count of accessed cache lines that encodes information and not the actual cache line contents. From a domain of 512 cache lines, if cache lines are accessed, the encoded value is m leading to or 9-bit message transmission. In summary, the number of accessed lines is the message, rather than the contents of cache lines. This coarser encoding leads to better noise tolerance. This multi-line encoding significantly increases the bandwidth compared to the binary encoding of traditional Prefetch implementations. The count of accessed lines corresponds to a specific message, enhancing the flexibility of the encoding mechanism. For example:

Accessing 1 cache line encodes Message 1.

Accessing 2 cache lines encodes Message 2.

Accessing n cache lines encodes Message n.

3.5. Fine-Grained Decoding Mechanism

The receiver measures the timing of PREFETCHW operations across all n cache lines and decodes the message by comparing measured latencies to pre-calibrated thresholds. For example:

If the measured timing exceeds T1 but is less than T2, it corresponds to Message 1 (1 cache line accessed).

If the timing exceeds T2 but is less than T3, it corresponds to Message 2 (2 cache lines accessed).

This fine-grained decoding allows the receiver to infer multi-bit data, improving efficiency and accuracy in covert communication.

3.6. Workflow for Multi-Line Encoding and Decoding

Sender Workflow: Wait for Receiver: The sender waits for the receiver_done_flag to ensure the receiver has processed the previous iteration.

The sender encodes a value by accessing cache lines for . For example, to transmit the value 3, the sender accesses 3 cache lines. In order to amplify the signal further, for cache accesses, we access m buckets of cache lines instead, where each bucket consists of b cache lines. Hence the total number of cache lines accessed for encoding a value m then is . This also places another constraint that which in our case is 512 lines. We experimented with bucket sizes which yielded as the best choice for the accuracy.

Time Operation: The sender uses rdtscp() for precise timing.

Signal Completion: The sender updates the receiver_done_flag to notify the receiver to start decoding.

Receiver Workflow:

Wait for Sender: The receiver waits for the receiver_done_flag which indicates that the sender has completed its encoding.

Decode Message: The receiver measures the timing of its PREFETCHW operations across all 512 L1 cache lines and decodes the message by comparing the measured timings against calibrated thresholds (T1 to Tn). The timing differences are influenced by the cache coherence protocol and the state transitions of the cache lines. When the PREFETCHW instruction is executed, it modifies the state of the cache line to M (Modified). The latency observed during this operation depends on whether the state of the cache line is M or S (Shared):

If the sender has not accessed the cache line, it remains in the M state when the receiver prefetches again. In this scenario, the PREFETCHW operation does not cause any state change and completes quickly.

If the sender accessed the cache line, the state transitions to S. When the receiver prefetches the same cache line, the PREFETCHW operation needs to inform the LLC to invalidate the copy in the sender’s private cache and transition the state back to M. This additional step increases the latency.

For example, in one experiment, the receiver observed that the PREFETCHW operation took approximately 130 cycles when the state transitioned from S to M, as the LLC had to invalidate the sender’s copy of the cache line. In contrast, when the cache line remained in the M state, the PREFETCHW operation completed in around 70 cycles since no state change was required. These timing differences are exploited by the receiver to infer whether the sender accessed the cache line, enabling it to infer the number of sender accessed cache lines, which divided by the bucket size b decodes the message accurately.

Store Decoded Message: The receiver stores the decoded message for further processing or logging.

Signal Readiness: The receiver sets the receiver_done_flag to notify the sender to start the next iteration.

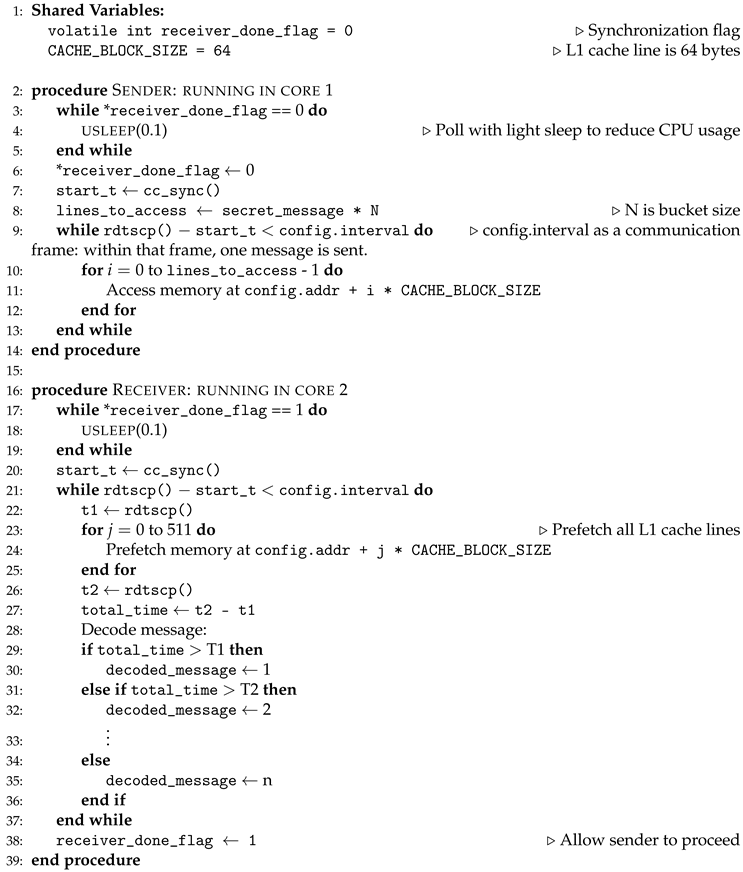

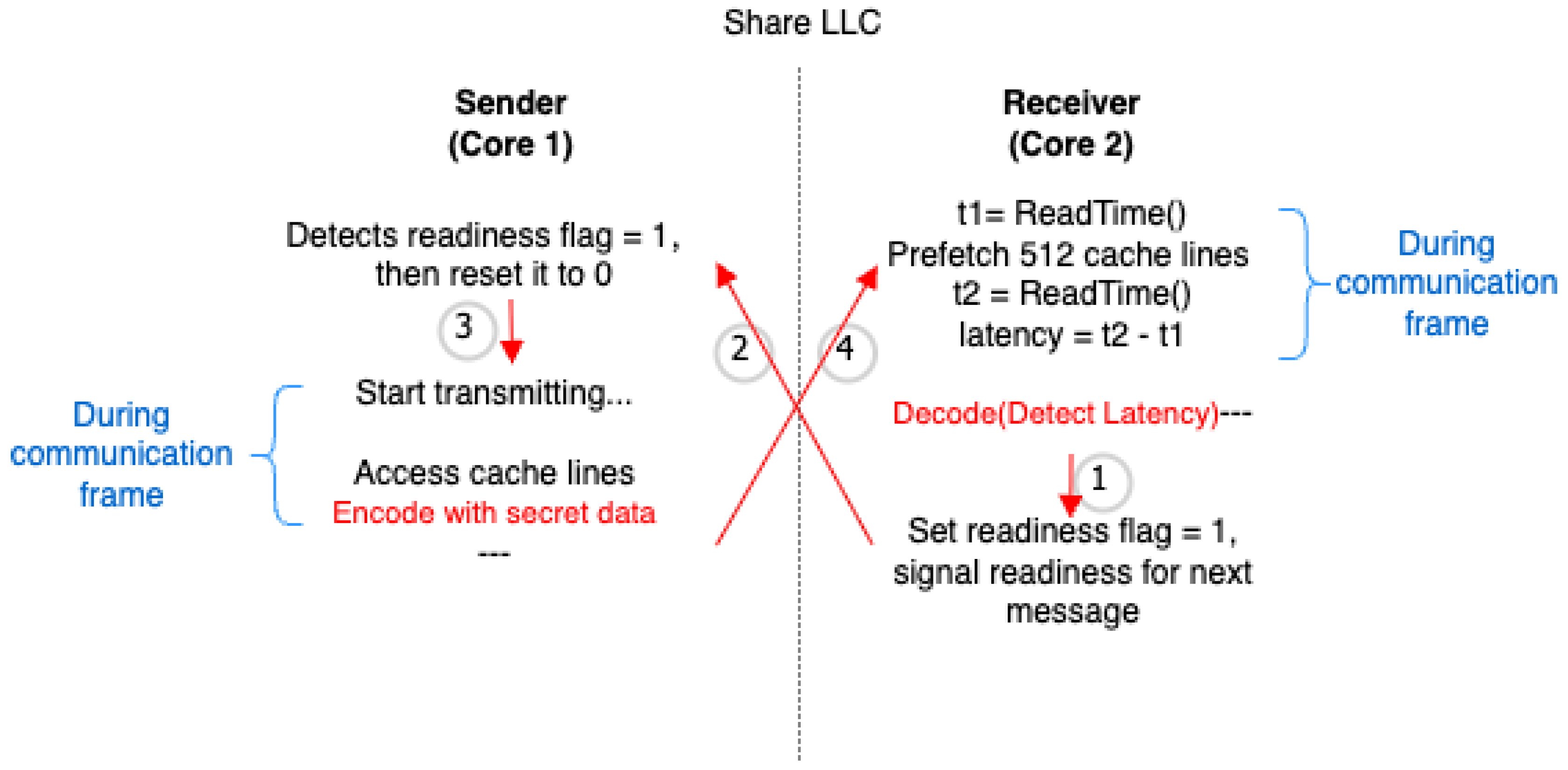

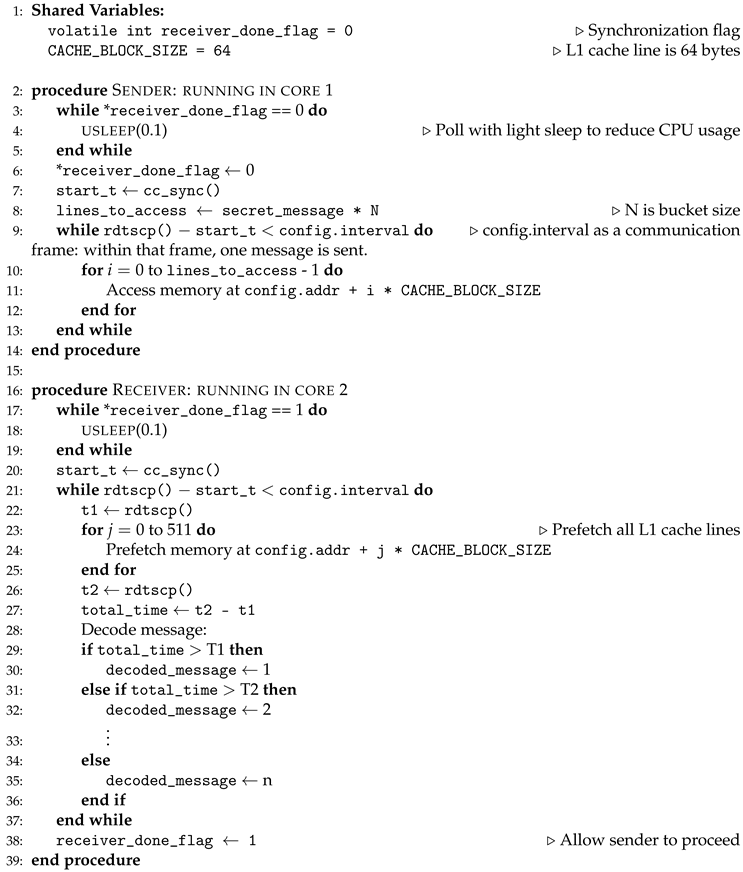

The protocol is shown in

Figure 1 and Algorithm 2. The sequence of interactions (Labeled Edges) is: 1. Receiver sets receiver_done_flag = 1 after initial prefetch measurement. 2. Sender detects receiver_done_flag = 1, resets it to 0. 3. Sender accesses memory lines (encoded with secret data) during config.interval. 4. Receiver prefetches memory lines and measures timing (affected by sender’s cache state). 5. Receiver sets receiver_done_flag = 1 to signal readiness for the next message.

|

Algorithm 2 Covert Channel Communication via Prefetch-Based Encoding |

|

Alternative Encoding Approach:

In addition to the shared-memory read-only configuration, we explored a second encoding approach where both sender and receiver are granted write permissions to the shared memory. In this configuration, the receiver observes longer latencies during PREFETCHW operations due to state transitions from I (Invalid) to M (Modified), instead of the S to M transition in the read-only setup. This change occurs because the sender writes to the shared memory, transitioning cache lines to the I state from the receiver’s perspective. When the receiver executes PREFETCHW, the coherence protocol must perform additional operations to bring the line back into the M state, resulting in higher timing overhead.

While this alternative provides slightly higher decoding accuracy due to the more pronounced timing gap between accessed and unaccessed lines, it results in lower throughput because of the increased latency in the decoding phase. Therefore, the choice between these two configurations—read-only versus writable shared memory—represents a tradeoff between accuracy and transmission speed.

3.7. Synchronization and Timing Optimizations

Lightweight Flag-Based Coordination: The sender and receiver synchronize using a shared memory flag (e.g., receiver_done_flag) to coordinate the encoding and decoding of each message. This approach avoids race conditions while minimizing busy waiting. To improve timing precision, both parties poll this flag while adaptively adjusting their polling intervals based on a locally maintained timestamp obtained via rdtscp(). This hybrid approach balances responsiveness and CPU efficiency, using short delays (e.g., usleep(0.1)) to avoid excessive spinning.

Limitations in Secure Environments: In our current setting, both sender and receiver operate outside of secure enclaves, allowing unrestricted access to high-resolution timers such as

rdtscp(). However, in trusted execution environments like Intel SGX or AMD SEV, access to precise timers is either restricted or unavailable. This makes

rdtscp-based synchronization infeasible for enclave-resident senders wishing to transmit sensitive data covertly. In these cases, time captured through loop based counters and measurements based on some other atomic activities [

21,

22] can serve as the time capture units.

Semaphore-Based Alternatives and Trade-offs: In such restricted environments, semaphores or barriers provide viable alternatives for synchronization. These primitives block the receiver until signaled by the sender, thus avoiding the need for polling and enabling more efficient CPU usage. However, these mechanisms typically rely on atomic operations or memory fences, which introduce additional microarchitectural side effects such as cache line invalidation and memory ordering constraints. Such effects may interfere with prefetch timing behavior and degrade the performance and accuracy of timing-based covert channels. As a result, while semaphores offer an enclave-compatible solution, their influence on cache state must be carefully considered when designing prefetch-based transmission mechanisms.

4. Results

4.1. Throughput and Accuracy

To evaluate the efficiency of our multi-line encoding covert channel, we measured both throughput and accuracy across different page sizes and encoding strategies. As shown in

Table 2, the read-only multi-line encoding achieved a throughput of approximately 4,623 KB/s with 4 KB pages and up to 4,940 KB/s with 2 MB huge pages, with an accuracy of up to 81.23%. The write-access encoding, which leverages

PREFETCHW to induce transitions from the

I to

M state rather than

S to

M, demonstrated slightly higher precision at 83.34%, although with slightly lower throughput—4,345 KB/s on 4 KB pages and 4,828 KB/s with 2MB huge pages.

Compared to the original single-line encoding approach from prior work [

1], which achieves a throughput of only 822 KB/s and transmits just a single bit per iteration, our multi-line encoding scheme provides a substantial improvement in both bandwidth and practicality. The original design cannot convey meaningful data efficiently due to its limited capacity. In contrast, our approach can encode and transmit 9 bits per iteration by accessing multiple cache lines, allowing for the efficient transmission of complex messages. Moreover, if greater decoding accuracy is desired, a bucket-based method can be employed: for example, transmitting message "1" by accessing 10 lines in one iteration, message "2" by accessing 20 lines, and so on. This technique trades throughput for enhanced resilience to noise and improved decoding reliability, offering flexibility between performance and accuracy.

While the reference paper [

1] achieved a reported accuracy of 96.2% using the single-line encoding scheme, our local reproduction under varying experimental conditions revealed a broader accuracy range of 60–80%. This divergence in results suggests potential sensitivity to environmental factors not fully replicated in our setup. To uphold transparency and avoid overstating outcomes, we have opted to omit accuracy metrics for [

1] results from the table, as they may not reliably reflect the scheme’s performance in generalized scenarios.

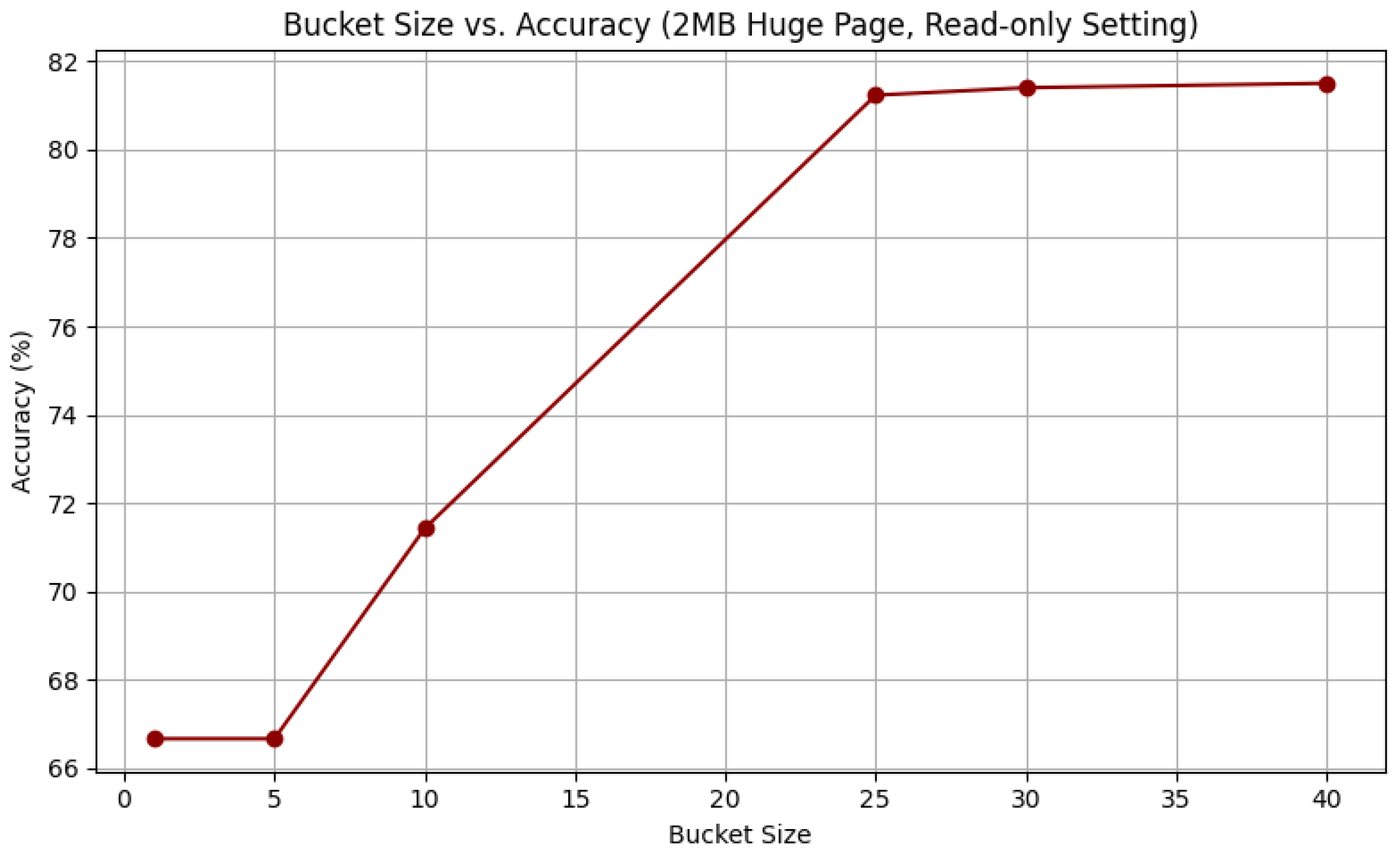

We further evaluated the influence of the bucket size on decoding accuracy under the read-only 2MB huge page setting. Our experiments show that as the bucket size increases, accuracy improves up to a point and then plateaus. Specifically, with a bucket size of 1 or 5, the accuracy remains at 66.67%; increasing the bucket size to 10 improves accuracy to 71.43%; and at a bucket size of 25, we achieve the peak accuracy of 81.23%. Further increases in bucket size beyond 25 yield no significant improvements, with accuracy remaining stable at 81.23%. This suggests that a moderate bucket size provides a good balance between throughput and accuracy.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between bucket size and accuracy.

Performance Comparison of High-Capacity Encodings: We further explored the trade-off between accuracy and throughput when transmitting messages of different lengths and cache line counts. The experiments in this section were conducted with the 2 MB huge page read-only setting.

Table 3 compares two schemes: (1) transmitting 10-bits messages using 1024 cache lines in a single iteration, and (2) transmitting 9-bits messages twice using 512 cache lines each time. The 10-bits scheme demonstrates higher overall accuracy due to a lower bit error rate, while the 9+9-bits scheme provides higher raw throughput but at the cost of increased error probability, resulting in a reduced chance of correctly decoding all bits.

These results indicate that if robustness and successful full-message decoding are the priorities, the 10-bits scheme with more cache lines is preferable. However, when maximizing bandwidth is critical and some errors are acceptable (or can be corrected), the 9+9-bits scheme may be beneficial.

To provide a more holistic evaluation of each encoding strategy, we introduce a composite metric that combines both throughput and decoding accuracy to compute the effective bandwidth in KB/s. This metric estimates the number of correct bits transmitted per second, capturing the real-world utility of the covert channel under noisy conditions.

For each scheme, we compute:

This reveals that while the 9+9-bit scheme achieves higher raw throughput, its effective bandwidth (factoring in accuracy) also remains superior to the 10-bit scheme. However, the 10-bit scheme retains an advantage in scenarios requiring reliable single-round decoding (e.g., short-lived channels with no retransmission). The choice ultimately depends on whether the application prioritizes raw speed or guaranteed correctness.

The adoption of huge pages further enhanced throughput and stability. Huge pages reduce TLB misses and maintain consistent memory access timing, benefiting both accuracy and stealth. Moreover, using varied numbers of cache-line accesses per iteration increases the unpredictability of access patterns, improving stealth against side-channel detection mechanisms. Unlike traditional binary encoding, our method minimizes observable LLC misses and system-level anomalies, making it more resilient against detection through performance monitoring tools.

Overall, the multi-line encoding approach not only provides higher throughput and accuracy but also expands the covert channel’s capacity for efficient, robust, and stealthy data exfiltration.

5. Discussion

Our evaluation demonstrates that the proposed multi-line prefetch-based covert channel significantly outperforms previous single-line encoding schemes in throughput. However, several avenues remain for further enhancement of channel reliability, robustness, and stealthiness.

Accuracy Optimization: While our current implementation achieves up to 83.34% decoding accuracy with the write-access encoding and 81.23% with the read-only encoding, accuracy can be further improved through several techniques. First, tuning the synchronization intervals between sender and receiver can mitigate timing drift and system noise that degrade decoding precision. Second, our current use of a bucket-based message encoding strategy—where each message corresponds to a specific number of accessed cache lines—already improves robustness by reducing decoding ambiguity. Further increasing the bucket size (i.e., using larger groups of cache line accesses per message) can improve accuracy, especially under noisy conditions, at the expense of reduced throughput.

Machine Learning-Based Decoding: Integrating a lightweight machine learning model for classification of timing traces could further enhance decoding accuracy, especially in noisy or unpredictable environments. By training the model on observed timing patterns associated with different line access counts or cache states, the receiver can better distinguish between valid message values and false positives caused by system activity or cache noise.

Expanding Coherence Exploits: Our current design focuses on leveraging the MESI cache coherence protocol, primarily through read and write operations that trigger transitions from the Shared (S) state to the Modified (M) state, as well as from the Invalid (I) state to the Modified (M) state. Future work could investigate a broader range of MESI state transitions, including the Exclusive (E) state, which may display distinct timing characteristics or variations in coherence traffic patterns. These additional behaviors could potentially enhance the bandwidth of the covert channel, improve stealth by reducing observable system events, and offer greater flexibility in encoding strategies.

6. Conclusion

In this work, we present a high-throughput, cache-based covert channel leveraging multi-line encoding strategies and the MESI cache coherence protocol. By encoding messages across multiple cache lines per iteration and utilizing both read-only and write-access patterns, our approach significantly improves upon prior single-line encoding techniques. Notably, our implementation achieves up to 4,940 KB/s throughput with 2MB huge pages and attains decoding accuracies of 81.23% (read-only) and 83.34% (write-based), outperforming prior single-line Prefetch+Prefetch attacks that are limited to 822 KB/s and binary messages.

We demonstrate that huge pages enhance channel stability and performance, and our encoding method supports richer message transmission—up to 9 bits per iteration—while retaining low detectability. Furthermore, we explore trade-offs between throughput and accuracy using a bucket-based encoding method, and we identify tuning opportunities such as synchronization timing and bucket size adjustment.

Future directions include applying machine learning models to improve decoding robustness, experimenting with other cache state transitions (e.g., E to M, I to E), and evaluating more sophisticated cache activities such as atomic operations or flushes. These extensions could further increase the stealth, bandwidth, and adaptability of covert communication in shared-memory systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xinyao Li; Methodology, Xinyao Li; Formal analysis, Xinyao Li; Writing—original draft, Xinyao Li; Writing—review & editing, Akhilesh Tyagi; Project administration, Akhilesh Tyagi; Funding acquisition, Akhilesh Tyagi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Guo, Y.; Zigerelli, A.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. Adversarial prefetch: New cross-core cache side channel attacks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1458–1473.

- Trippel, C.; Lustig, D.; Martonosi, M. MeltdownPrime and SpectrePrime: Automatically-synthesized attacks exploiting invalidation-based coherence protocols. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03802 2018.

- Fogh, A. “Row hammer, java script and MESI 2016.

- Götzfried, J.; Eckert, M.; Schinzel, S.; Müller, T. Cache Attacks on Intel SGX. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th European Workshop on Systems Security, New York, NY, USA, 2017; EuroSec’17. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Kim, J. A Novel Covert Channel Attack Using Memory Encryption Engine Cache. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Design Automation Conference 2019, New York, NY, USA, 2019; DAC ’19. [CrossRef]

- Lantz, D. Detection of side-channel attacks targeting Intel SGX. Master’s thesis, Linköping University, 2021.

- Miketic, I.; Dhananjay, K.; Salman, E. Covert Channel Communication as an Emerging Security Threat in 2.5D/3D Integrated Systems. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Zhang, P.; Kim, D.; Park, J.; Lee, C.H.; Zhao, Z.; Doupé, A.; Ahn, G.J. Prime+Count: Novel Cross-world Covert Channels on ARM TrustZone. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2018; ACSAC ’18, p. 441–452. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tyagi, A. Cross-World Covert Channel on ARM Trustzone through PMU. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S. A survey of recent prefetching techniques for processor caches. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2016, 49, 1–35.

- Zhang, Z. Lecture Notes on Cache Prefetching, 2005. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Oren, N. A Survey of prefetching techniques. Relatório Técnico Julho De 2000.

- Chen, Y.; Xue, H. Optimizing Memory Performance with Explicit Software Prefetching. ACM Digital Library 2016. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Ashwathnarayana, S. Understanding Huge Pages 2023. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Red Hat. Chapter 9. What huge pages do and how they are consumed by applications, n.d. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- TechOverflow. Advantages and disadvantages of hugepages, 2017. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Luo, T.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z. Improving TLB performance by increasing hugepage ratio. In Proceedings of the 2015 15th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing. IEEE, 2015, pp. 1139–1142.

- Easyperf. Performance Benefits of Using Huge Pages for Code, 2022. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Panwar, A.; Prasad, A.; Gopinath, K. Making huge pages actually useful. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, 2018, pp. 679–692.

- Fan, R. A Comprehensive Guide to Using Huge Pages in Oracle Databases, 2023. Accessed: January 7, 2025.

- Dutta, S.B.; Naghibijouybari, H.; Abu-Ghazaleh, N.; Marquez, A.; Barker, K. Leaky buddies: cross-component covert channels on integrated CPU-GPU systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 48th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture. IEEE Press, 2021, ISCA ’21, p. 972–984. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Drean, J.; Behrens, J.; Yan, M. There’s always a bigger fish: a clarifying analysis of a machine-learning-assisted side-channel attack. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 49th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISCA ’22, p. 204–217. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).