Introduction

Portland cement remains the most widely used material in the construction industry. However, its production is a major contributor to CO₂ emissions, raising serious environmental concerns. The cement sector alone accounts for approximately 7–8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Despite these issues, Portland cement possesses unique properties that make it difficult to be replaced [

1,

2]. In recent years, alkali-activated materials (AAMs) have emerged as promising alternatives. These materials are synthesized by reacting with aluminosilicate precursors and highly alkaline solutions. AAMs exhibit several advantageous properties, including thermal and mechanical resistance, chemical resistance (e.g., to acidic environments), high compressive and flexural strength, low shrinkage, and the ability to cure at ambient temperature [

3].

The properties of alkali-activated materials are highly dependent on the type of raw materials used in their synthesis [

3]. The first material to be evaluated is the aluminosilicate source, which is mainly responsible for achieving an adequate SiO₂/Al₂O₃ ratio. This ratio directly influences the final strength of the alkali-activated product. Many materials are currently being used as aluminosilicate sources, such as fly ash, glass waste, mining residues, clays, soils, synthetic reagents, and other types of waste [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The combination of different aluminosilicate sources is a common strategy to attain a more appropriate SiO₂/Al₂O₃ molar ratio, optimized for the requirements of specific applications. Although synthetic materials can be used for this purpose, it is not ideal, as it makes the process more expensive.

Moreover, when using clay minerals such as kaolinite, it is necessary to convert them into metakaolinite through thermal treatment at temperatures between 500–800 °C. This treatment is favorable for increasing the reactivity of the mineral [

14].

Another fundamental component of alkali-activated materials is the alkaline activator, which is responsible for controlling the SiO₂/Na₂O ratio. This ratio also contributes to both the mechanical properties and the curing time. Commercial reagents are commonly used for this purpose, such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (KOH), calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)₂], and sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃). Although commercial activators confer favorable properties to the final products, their use increases production costs. Alternatively, certain industrial waste materials—such as red mud, a byproduct of the Bayer process with high alkalinity, and carbide slag, a residue from the chlor-alkali industry—can serve as effective alkaline activators [

15,

16].

Although the advantages of alkali-activated materials are significant, it is important to evaluate whether the raw material compositions, elements such as Na, Al, Si, and others, may be released into the environment when used in construction applications. Considering the benefits of alkali-activated materials and the essential components for their synthesis, the present study aims to produce an alkali-activated material from Amazon bauxite tailings—a source of aluminosilicate (kaolinite)—without converting it into metakaolinite, thereby reducing the energy required for synthesis, and using only sodium hydroxide as the alkaline activator. Furthermore, this research evaluates the potential release of metals (Al, Cd, Na, Si, Ti, among others) and metalloids (As) from the alkali-activated material into the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

The sample used in this study (ALB-1) is representative of Bauxite Washing Clay and was sourced from Mineração Paragominas S.A., located in the municipality of Paragominas. Sampling was carried out by company personnel. Additionally, commercial-grade Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) was employed as the alkaline activator.

2.2. Sample Characterization

2.2.1. Mineralogical Composition

The sample was ground following the powder method to determine the mineralogical phases and subjected to X-ray diffraction. The analysis was carried out using a BRUKER diffractometer, model D2 PHASER, with a θ/θ goniometer, radius: 141.1 nm, copper anode with a characteristic emission line of 1.54 Å / 8.047 keV (Cu-Kα1), and a maximum power of 300 W (30 kV × 10 mA). The detector used was the Linear Lynxeye with a 5° 2θ aperture and 192 channels. All analyses were performed at the Laboratory of Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Applications (LAMIGA-UFPA) of the Geosciences Institute at UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2.2.2. Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of sample ALB-1 was determined by X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (XRF) using fused pellets. The pellets were prepared at a ratio of 0.8 g of sample to 8 g of flux (lithium tetraborate), with the addition of approximately 5 mg (15%) lithium bromide as a releasing agent. The analyses were carried out in a commercial laboratory.

Loss on ignition (LOI) was determined gravimetrically by calcining previously dried samples at 1000 °C.

2.2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

This technique was used as a complementary analysis to the XRD results, aiding in the characterization of the raw samples. Approximately 0.0015 g of each sample was mixed with 2 g of potassium bromide (KBr, Merck). The mixture was homogenized using an agate mortar and pestle. Pellets were then formed using 14 mm steel molds and pressed under 8 Kbar pressure using a manual Specac 8 press. The analyses were carried out using a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer, in the spectral range of 400–4000 cm⁻¹. This procedure was conducted at LAMIGA-UFPA of the Geosciences Institute at UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2.2.4. TG/DSC

Thermal analysis of the sample was performed using a NETZSCH STA 449 F5 Jupiter simultaneous thermal analyzer, equipped with a vertical cylindrical furnace, nitrogen flow of 50 mL/s, a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and a temperature range from 30 °C to 1100 °C. This procedure was carried out at LAMIGA-UFPA of the Geosciences Institute at UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2.3. Geopolymer Synthesis, Hexagonal Paver Production, and Technological Tests

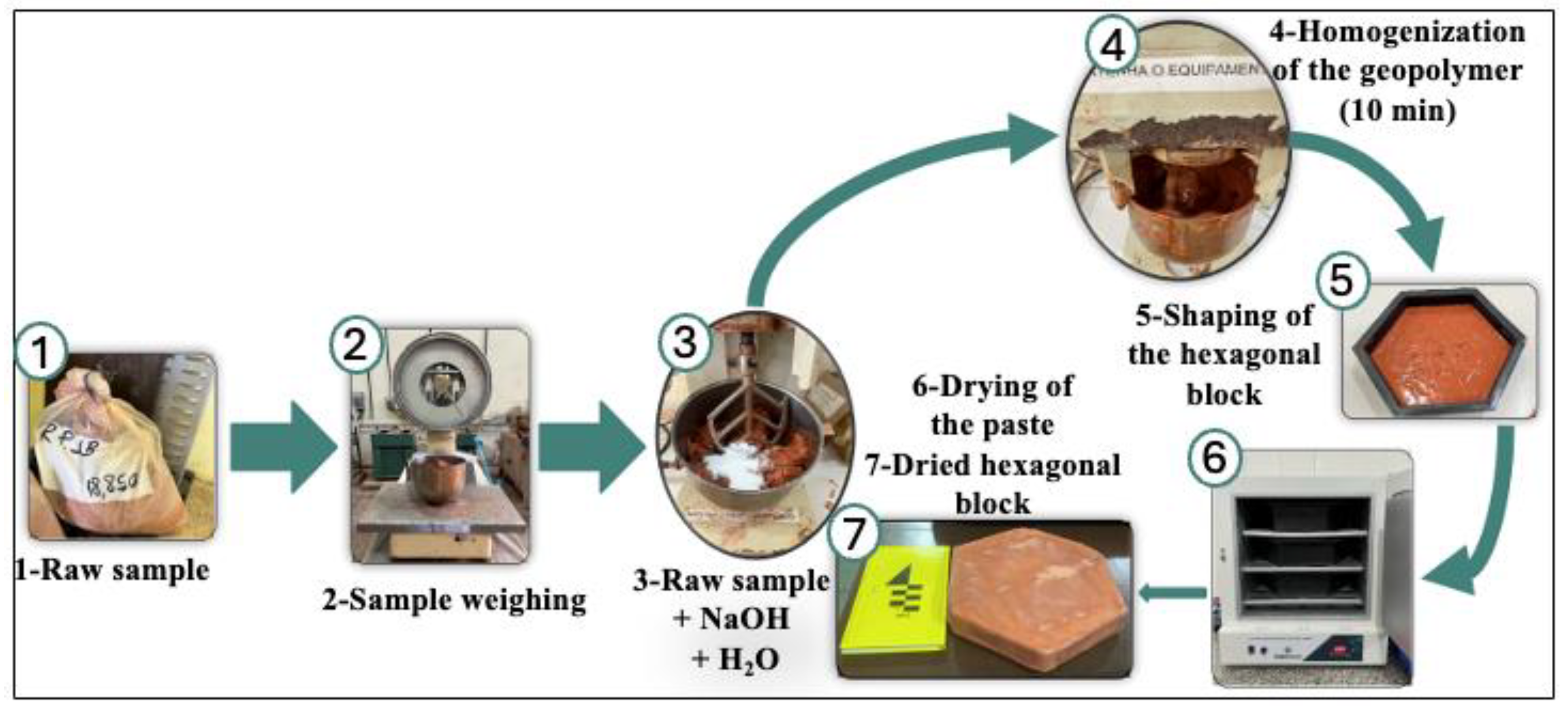

2.3.1. Production of Hexagonal Pavers (25 cm × 25 cm)

Figure 1 illustrates the process of production of hexagonal Pavers (ALK-1). A mixture containing 2.0 kg of ALB, 200 g of NaOH (to maintain a Na/Al molar ratio of 0.6), and 460 mL of water was prepared to obtain a solid-to-liquid ratio of 34.5%, as established in a previous study [

17]. All components were transferred to a mortar mixer and homogenized for approximately 10 minutes. The resulting paste was then cast into hexagonal molds. Drying was performed in an electric oven at two temperatures: 40 °C for 1 week and 50 °C for 3 weeks.

2.4. Geopolymer Testing

All technological tests and leaching assays were performed in triplicate using specimens with dimensions of 20 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm prepared from the hexagonal block (

Figure 2).

2.4.1. Water Absorption and Apparent Porosity

These parameters were evaluated following the ASTM C20-00 standard [

18].

2.4.2. Compressive Strength

Compressive strength tests were conducted using a universal testing machine, model 300/15 kN, Servo-plus Evolution from MSTEST, with a loading rate of 1 MPa/s. The test started at 1 N and ended at 30% of the maximum load. The test was performed at the Concrete Laboratory of the School of Architecture at UFPA, of the Technology Institute at UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2.4.3. Leaching Test and Analysis of Leachates

The leaching test was performed using a method adapted from the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards - ABNT 10005. The solution used was 0.1 M HNO₃. The test involved immersing triplicate specimens in the acid solution for 7 (experiment 1, 2, and 3), 14 (experiment 4, 5, and 6), 21 (experiment 7, 8, and 9), and 28 days (experiment 10, 11, and 12). At the end of each cycle, the solution was collected and replaced with a fresh one to proceed to the next cycle. The leachates were analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). Based on the sample composition and the NaOH reagent, the analytes selected were Al, As, Ca, Cd, Cr, Fe, Mg, Mn, Na, Ni, Pb, Si, and Ti. The analytical curve was prepared in an acidic medium (2% v/v HNO₃), with concentrations of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/L. The method of analyte addition and recovery was used to validate the measurements.

2.4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Images were obtained from the ALK-1 sample using a HITACHI TM-3000 scanning electron microscope, coupled with an energy-dispersive spectrometer – EDS, SWIFT ED-3000, from Oxford Instruments. The analyses were performed at LAMIGA-UFPA of the Geosciences Institute at UFPA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

3. Results

3.1. Raw Sample

3.1.1. Mineralogy by XRD, Chemical Composition, FTIR Spectroscopy, and Thermal Analysis (TG/DSC)

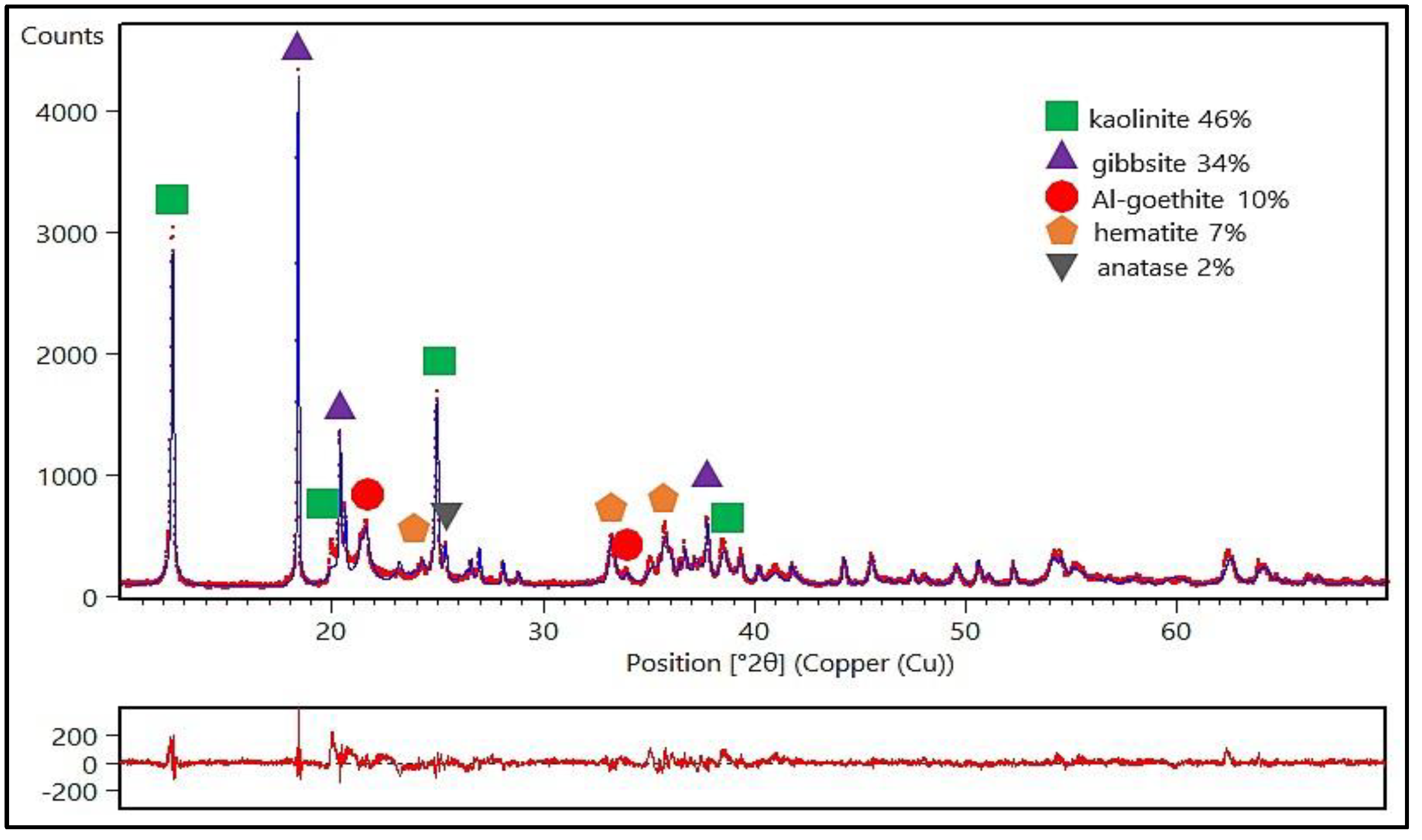

Figure 3 shows the X-ray diffractogram of sample ALB-1. It can be observed that the sample is composed of characteristic peaks of minerals such as kaolinite (46%), gibbsite (34%), Al-goethite (10%), hematite (7%), and anatase (2%). This mineralogical composition is well-established for Bauxite Washing Clay samples. In the present study, which focuses on the synthesis and application of geopolymer, one of the most relevant aspects regarding the sample’s mineralogy is the predominance of kaolinite, the main aluminosilicate mineral used for geopolymer production [

19,

20,

21].

Table 1 shows the chemical composition of the ALB-1 sample. The major constituents are Al

2O

3, SiO

2, and Fe

2O

3, which together represent more than 80% of the total oxide composition. This content is associated with the mineralogy of the sample. Al

2O

3 is present in kaolinite, gibbsite, and Al-goethite, SiO

2 is essentially from kaolinite, while Fe

2O

3 is derived from hematite and goethite. The remaining percentage relates to the loss on ignition (LOI: 18.73%) and a minor quantity of other compounds.

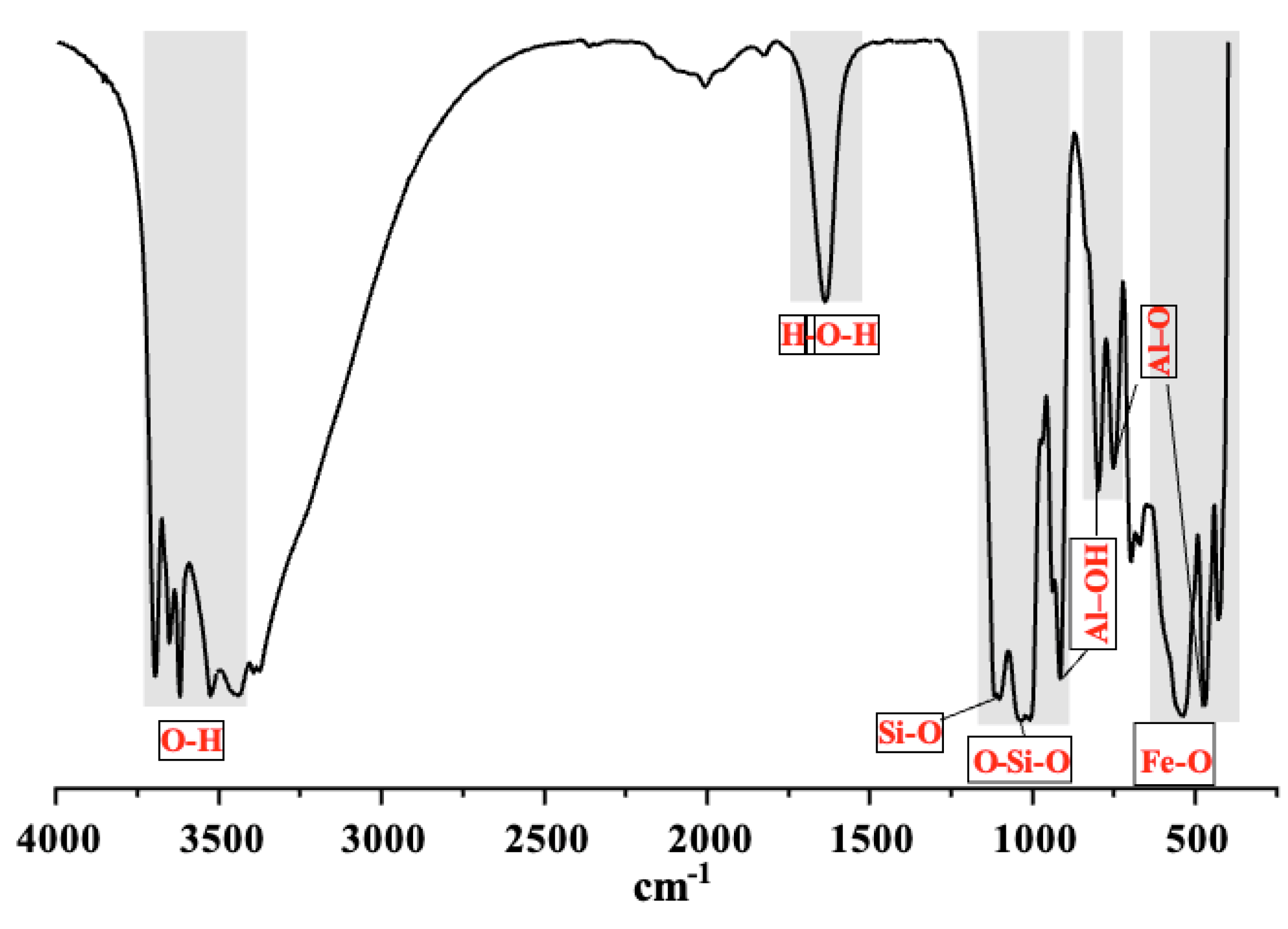

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum is shown in

Figure 4. The absorption bands at 3437, 3525, 3620, and 3695 cm⁻¹ are associated with the O–H bond present in kaolinite, gibbsite, and water [

19]. The band at 1635 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the vibrational mode of water molecules. The absorption near 1100 cm⁻¹ is characteristic of the Si–O stretching bond in kaolinite. The band at 1010 cm⁻¹ is also attributed to kaolinite and corresponds to the symmetric stretching of the Si–O–Si bond. The bands at 468 and 750 cm⁻¹ are related to the symmetric stretching of the Al–O bond. The bands at 912 cm⁻¹ and 796 cm⁻¹ are assigned to the angular deformation of the Al–OH bond and translational vibration of the –OH group in gibbsite, respectively. The absorption at 538 cm⁻¹ is related to the angular deformation of the Fe–O bond in hematite.

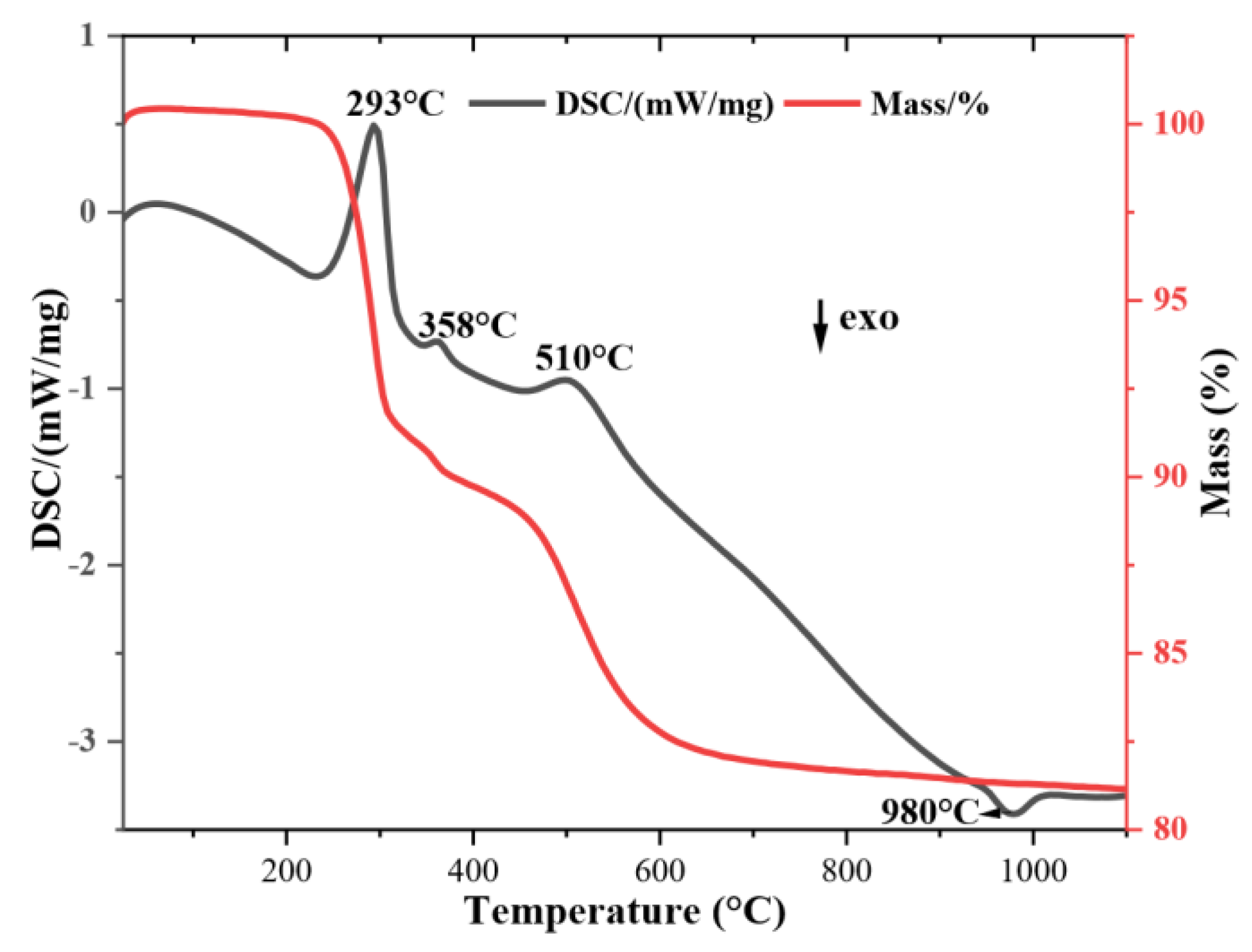

Figure 5 presents the TG/DSC curves of the ALB-1 sample. The curves show characteristic events of the minerals identified by XRD. Three endothermic and one exothermic event were observed. The first endothermic peak at 293 °C corresponds to the release of structural water from gibbsite. The second peak, at 358 °C, confirms the presence of goethite, characterized by the release of constitutional water. The third endothermic event at 510 °C is associated with the dehydroxylation of kaolinite, leading to the formation of metakaolinite [

22,

23]. The only exothermic event observed at 980 °C, corresponds to the crystallization of mullite [

22].

3.2. Alkali Activated Specimen (ALK-1)

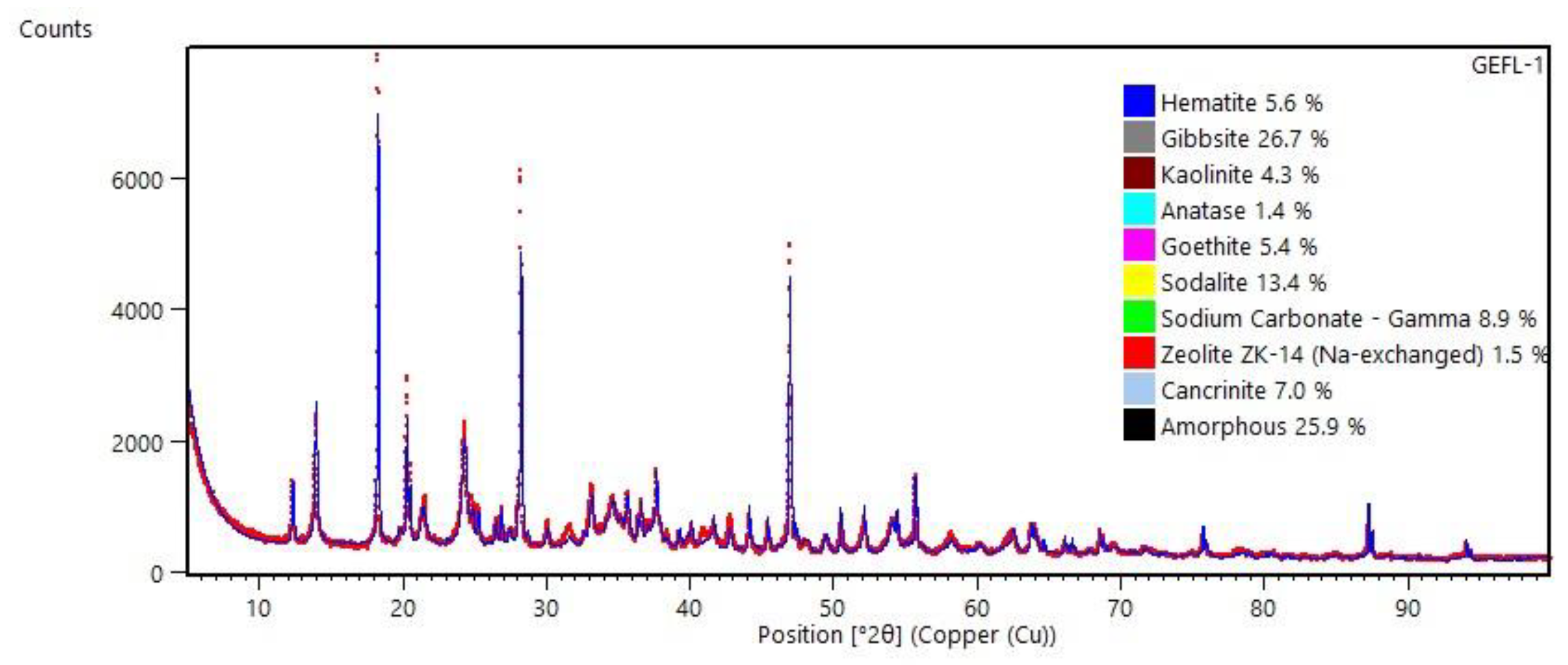

3.2.1. Crystalline and Amorphous Phases After XRD

The mineralogical composition of the block (ALK-1) is shown in

Figure 6. The results indicate the persistence of all minerals present in the raw sample: kaolinite, gibbsite, hematite, goethite, and anatase. However, their relative contents significantly decreased compared to the original sample. Kaolinite, for example, which initially constituted approximately 46% of the sample, was reduced to 4.3%. This reduction confirms that most of the kaolinite reacted with NaOH solution, resulting in the formation of zeolite ZK-14 (1.5%), sodalite (13.4%), cancrinite (7%), and amorphous phases (25.9%) [

19,

22]. This composition suggests that the resulting alkali-activated material can be classified as a hybrid product, composed of both crystalline phases (ZK-14 and cancrinite) and amorphous phases. The presence of crystalline phases contributes to improved refractory properties [

24]. Additionally, the presence of sodium carbonate suggests that part of the product reacted with atmospheric CO₂. This phenomenon can be mitigated by curing the material in a controlled humidity environment.

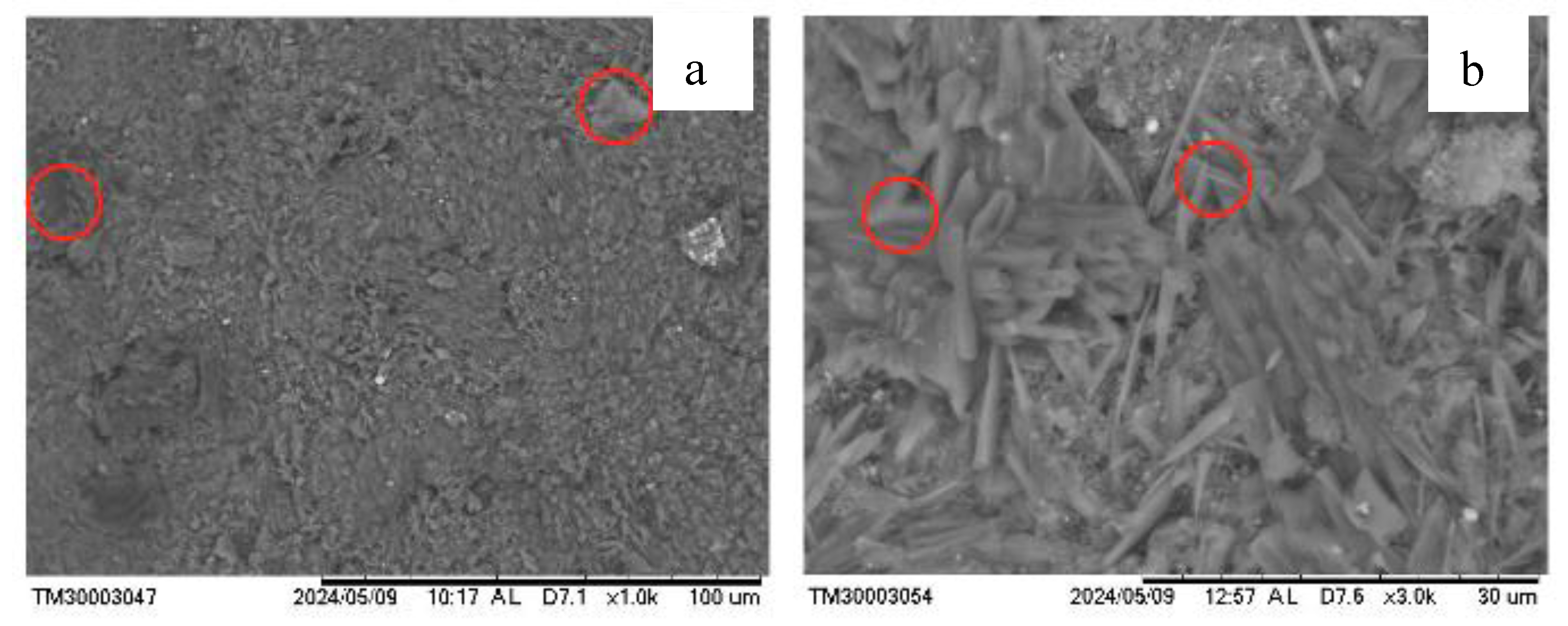

3.2.2. Microscopical Texture Features by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of the geopolymer, as observed by SEM, is shown in

Figure 7. The presence of an amorphous gel phase is evident, indicating successful geopolymer formation. Some larger particles suggest an incomplete reaction. In Figure b, rod-like structures are observed, likely corresponding to cancrinite crystals [

25,

26], as well as polycrystalline porous agglomerates that may be related to sodalite [

24,

27]. The formation of needle-like structures may result from the later stages of the transitional gel phase, possibly indicating the progressive crystallization or organization of the gel components [

5].

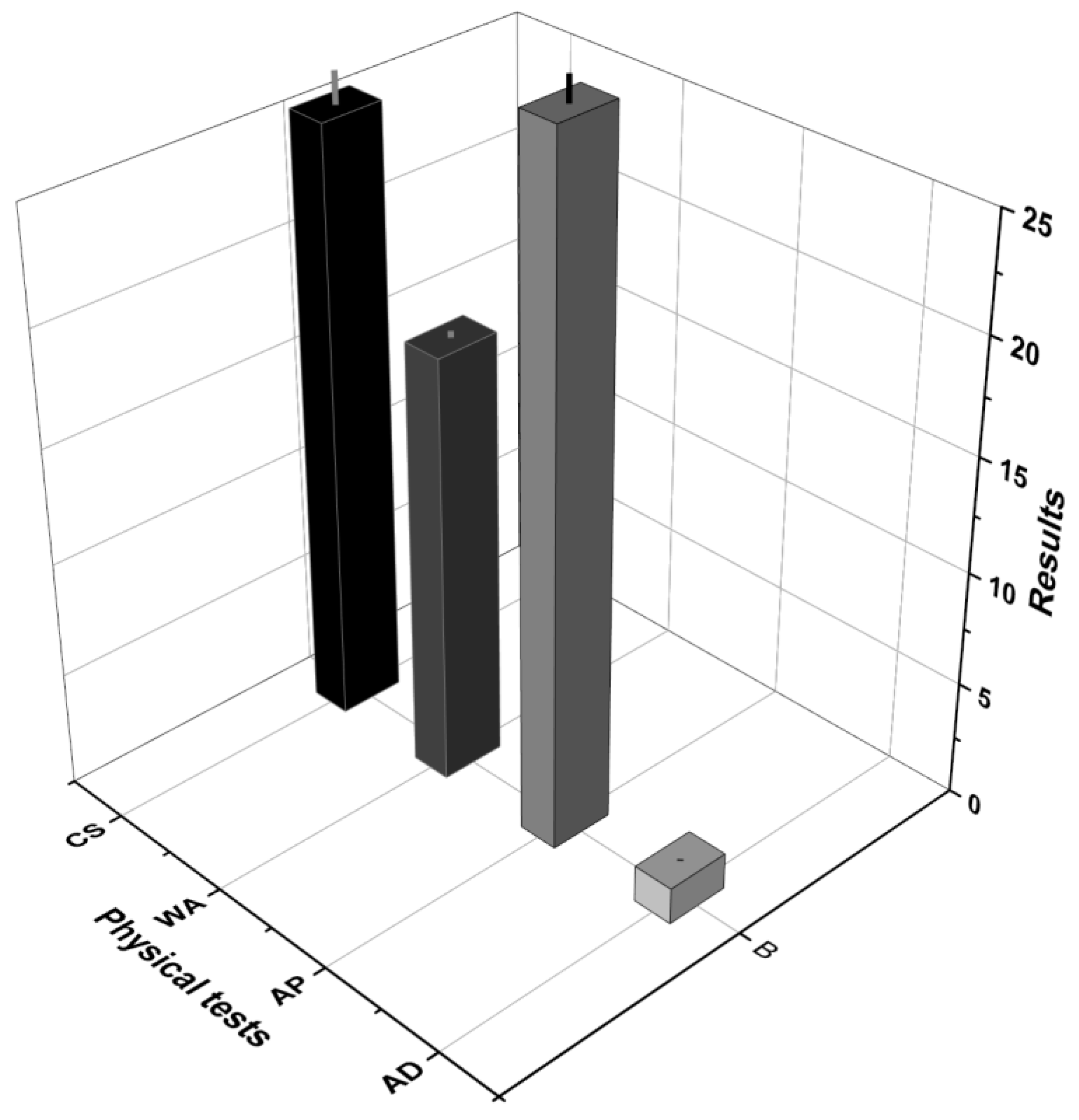

3.2.3. Technological Properties

Figure 8 presents the results for apparent density (AD), apparent porosity (AP), water absorption (WA), and compressive strength (CS). The geopolymer exhibited an apparent density of 1.60 g/cm³ ± 0.04, indicating good compaction with the defined NaOH and water ratios. Apparent porosity was 29.78% ± 1.06. Water absorption was 18.61% ± 0.25, which is favorable when compared to the standard limits for tiles and bricks (20–22%). The compressive strength reached 25.83 MPa ± 1.33, which is considered high, especially considering that the ALB-1 sample was not thermally treated to convert kaolinite into metakaolinite and no external source of SiO₂ was added during synthesis.

3.2.4. Leaching Test

The concentrations of leached elements after 7, 14, 21, and 28 days are shown in

Table 2. The concentrations of As, Ca, Cr, Fe, Mg, Mn, Ni, and Pb were below the detection limit of the equipment, indicating that if released, these elements are present in concentrations lower than 0.001 mg/L (e.g., the detection limit for Pb). In contrast, Al, Cd, Na, Si, and Ti were detected in all leaching cycles. Cadmium concentrations remained constant throughout the cycles, ranging from 0.02 to 0.03 mg/L. Titanium was detected only at 7 days (5.33 mg/L). Silicon was released along all cycles, with concentrations of 3.93 mg/L (7 days), 66.52 mg/L (14 days), 29.20 ± 0.38 mg/L (21 days), and 46.76 ± 0.08 mg/L (28 days). Aluminum concentrations ranged from 26.27 ± 16.24 mg/L (21 days) to 36.34 ± 10.16 mg/L (28 days), with the highest release at the longest testing period. Sodium showed the highest concentrations, ranging from 1375.31 ± 9.74 mg/L (7 days) to 513.77 ± 11.30 mg/L (28 days), with the highest leaching at the shortest time.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Properties

The synthesis parameters adopted in this study—including water content, NaOH concentration, and curing time and temperature—proved effective for producing alkali-activated pastes with desirable technological properties. Specifically, the materials demonstrated good compaction, adequate density, and low values of water absorption (WA) and apparent porosity (DA), indicating a well-structured matrix.

The compressive strength results align with findings from other studies [

8,

28] that utilized NaOH and alternative alkaline activators. Some studies have reported compressive strengths of up to 12.2 MPa after 90 days of curing with NaOH as the activator [

13], while others have reached values as high as 32.97 MPa [

29]. The compressive strength obtained in this study is considered adequate, suggesting that the product could be used as an additive for cement or even as a partial substitute for concrete [

30,

31].

For our study, this performance can be attributed, in part, to the presence of zeolitic phases in the precursor, which are known to enhance durability and weathering resistance [

32]. Within the context of using bauxite residue as the aluminosilicate source, the data suggest that costly additives, such as commercial silica or sodium silicate, may be unnecessary for achieving satisfactory mechanical performance.

Moreover, the physical performance observed is particularly noteworthy when compared to literature that reports high-strength materials typically based on metakaolin and synthesized under elevated temperatures. In contrast, the approach adopted here eliminated the need for thermal activation and still resulted in a structurally competent product [

14,

33,

34,

35], highlighting its potential for more sustainable and cost-effective applications.

4.2. Leaching Test

Elevated release levels of certain elements may suggest a moderate dissolution of the geopolymeric gel—mainly composed of Al, Si, and Na—under mildly acidic conditions. This elemental release may also be influenced by the concentration of the alkali activator, which increases the pH of the medium and contributes to the leaching of these elements, as previously reported by [

36]. Similar to other studies, this product does not release toxic metals, such as lead, chromium, and arsenic [

31]. Although the concentrations of Al, Na, and Si exceeded the regulatory limits established by CONAMA Resolutions 454/12 and 420/09, parameters such as temperature, simulated rainfall, and granulometry must be evaluated, as these elements may be released into the environment depending on local application conditions. Furthermore, the potential impact on human health should be carefully assessed [

31,

37,

38].

In this context, the release also could be attributed to the high alkalinity of the solution, as not all the Na present in the alkaline solution reacts directly with the aluminosilicate precursor.

5. Conclusions

The bauxite washing residue sample is predominantly composed of aluminum- and silica-rich minerals (kaolinite and gibbsite), which are favorable for geopolymer synthesis.

The direct geopolymerization process, carried out without thermal pretreatment or external silica addition, demonstrated promising technological potential, as evidenced by low water absorption and substantial mechanical strength. These characteristics suggest that the resulting product could serve as an excellent and eco-friendly alternative for applications in the construction sector.

Regarding the release of metals and metalloids, the most prominent elements detected were Al, Si, and Na—major constituents of the geopolymeric matrix. The leaching behavior of these elements requires further investigation to ensure environmental safety. Additionally, a broader range of parameters must be assessed to fully understand the conditions that may trigger the leaching of all analyzed elements.

Based on the results presented, the material studied shows promising potential for use in paving block production, pending further investigation into environmental implications.

Acknowledgments

To Hydro Paragominas for sample disposable during the project 4486 HYDRO/UFPA/FADESP; To CNPQ for financial support (Grant nr. 304.967/2022-0).

Author Contributions

Igor Alexandre Rocha Barreto: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization; Marcondes Lima da Costa: Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Funding

This research was supported by Hydro Company and the Dean of Research and Graduate Studies (PROPESP) of the Universidade Federal. do Par. (UFPA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are included within the article and/or supporting materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adjei, S.; Elkatatny, S.; Aggrey, W.N.; Abdelraouf, Y. Geopolymer as the Future Oil-Well Cement: A Review. J Pet Sci Eng 2022, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, U.; İlkentapar, S.; Karahan, O.; Uzal, B.; Atiş, C.D. A New Parameter Influencing the Reaction Kinetics and Properties of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers: A Pre-Rest Period before Heat Curing. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulayt, A.; Gounni, A.; El Alami, M.; Hakkou, R.; Hannache, H.; Gomina, M.; Moussa, R. Thermo-Physical Characterization of a Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Incorporating Calcium Carbonate: A Case Study. Mater Chem Phys 2020, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, H.; Mostofinejad, D. Microstructural Characterization of Alkali-Activated Concrete Using Waste-Derived Activators from Industrial and Agricultural Sources: A Review. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jiang, E.; Li, K.; Shi, H.; Chen, C.; Yuan, C. Study on the Alkali-Activated Mechanism of Yellow River Sediment-Based Ecological Cementitious Materials. Materials 2025, 18, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Kou, Z.; Tang, C.; Shi, Z.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, K. Recent Progress in Synthesis of Zeolite from Natural Clay. Appl Clay Sci 2023, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Martinho, A.; Oliveira, J.P. Recycling of Reinforced Glass Fibers Waste: Current Status. Materials 2022, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksar Najafi, E.; Jamshidi Chenari, R.; Arabani, M. THE POTENTIAL USE OF CLAY-FLY ASH GEOPOLYMER IN THE DESIGN OF ACTIVE-PASSIVE LINERS: A REVIEW. Clays Clay Miner 2020, 68, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, N.; Badiei, M.; Samsudin, N.A.; Mohammad, M.; Razali, H.; Hui, D. Clean Technology Option Development for Smart and Multifunctional Construction Materials: Sustainable Geopolymer Composites. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Qi, T.; Vogrin, J.; Huang, Q.; Wu, W.; Vaughan, J. The Effect of Leaching Temperature on Kaolinite and Meta-Kaolin Dissolution and Zeolite Re-Precipitation. Miner Eng 2021, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, T.; Guo, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, P. Effect of the SiO2/Al2O3 Molar Ratio on the Microstructure and Properties of Clay-Based Geopolymers: A Comparative Study of Kaolinite-Based and Halloysite-Based Geopolymers. Clays Clay Miner 2022, 70, 882–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of Fly Ash Vitrified Slag (FVS) Dosage and Alkali Content on the Reaction of Alkali-Activated Material (AAM). Mater Today Commun 2025, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Han, Y.; Jia, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z. Study on Mechanical Properties and Curing Reaction Mechanism of Alkali-Activated-Slag Solidified Port Soft Soil with Different Activators. Materials 2025, 18, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glid, M.; Sobrados, I.; Rhaiem, H. Ben; Sanz, J.; Amara, A.B.H. Alkaline Activation of Metakaolinite-Silica Mixtures: Role of Dissolved Silica Concentration on the Formation of Geopolymers. Ceram Int 2017, 43, 12641–12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.; Li, H.; Liu, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, H.; Wan, Z.; Wu, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L. Improved Macro-Microscopic Characteristic of Gypsum-Slag Based Cementitious Materials by Incorporating Red Mud/Carbide Slag Binary Alkaline Waste-Derived Activator. Constr Build Mater 2024, 428, 136425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Duan, G.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Pang, H.; Zhang, J. Comparison of Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of GGBS-Based Cementitious Materials Activated by Different Combined Alkaline Wastes. Constr Build Mater 2024, 422, 135784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I.; Lima, M. Use of the Clayey Cover of Bauxite Deposits of the Amazon Region for Geopolymer Synthesis and Its Application in Red Ceramics. Constr Build Mater 2021, 300, 124318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C20-00 Standard Test Methods for Apparent Porosity, Water Absorption, Apparent Specific Gravity, and Bulk Density of Burned Refractory Brick and Shapes by Boiling Water. American Society for Testing and Materials 2015, 00, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. Study on Mechanical Properties and Hydration Characteristics of Bauxite-GGBFS Alkali-Activated Materials, Based on Composite Alkali Activator and Response Surface Method. Materials 2025, 18, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.Z.; Cizer, Ö.; Pontikes, Y.; Heath, A.; Patureau, P.; Bernal, S.A.; Marsh, A.T.M. Advances in Alkali-Activation of Clay Minerals. Cem Concr Res 2020, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Yuan, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Deng, L.; Liu, D. Geopolymerization of Halloysite via Alkali-Activation: Dependence of Microstructures on Precalcination. Appl Clay Sci 2020, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, S. Dispersion, Properties, and Mechanisms of Nanotechnology-Modified Alkali-Activated Materials: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synthesis and Characterization of Kaolinite-Based Geopolymer-Alkaline.

- Ren, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Du, P.; Zhang, X. Regulation of the Composition of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer: Effect of Zeolite Crystal Seeds. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Aksenov, S.M.; Rastsvetaeva, R.K. Structural Chemistry, IR Spectroscopy, Properties, and Genesis of Natural and Synthetic Microporous Cancrinite- and Sodalite-Related Materials: A Review. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2021, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, I.V.; Doyle, A.M.; Amedlous, A.; Mintova, S.; Tosheva, L. Scalable Solvent-Free Synthesis of Aggregated Nanosized Single-Phase Cancrinite Zeolite. Mater Today Commun 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Aksenov, S.M.; Pekov, I.V. Infrared Spectroscopy as a Tool for the Analysis of Framework Topology and Extra-Framework Components in Microporous Cancrinite- and Sodalite-Related Aluminosilicates. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2023, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Játiva, A.; Corominas, A.; Etxeberria, M. Durable Mortar Mixes Using 50% of Activated Volcanic Ash as A Binder. Materials 2025, 18, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaičiukynienė, D.; Liudvinavičiūtė, A.; Bistrickaitė, R.; Boiko, O.; Vaičiukynas, V. Alkali-Activated Slag Repair Mortar for Old Reinforced Concrete Structures Based on Ordinary Portland Cement. Materials 2025, 18, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, R.M.; Potharaju, M.; Srinivas, V.; Kanaka Durga, S.; Rathnamala, G.V.; Paudel, A. Compressive and Flexural Strength of Concrete with Different Nanomaterials: A Critical Review. J Nanomater 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Nie, Q.; Dai, X.; Wan, Z.; Zhong, J.; Ma, Y.; Huang, B. Developing Alkali-Activated Controlled Low-Strength Material (CLSM) Using Urban Waste Glass and Red Mud for Sustainable Construction. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, B.C.; Pedroti, L.G.; Vieira, C.M.F.; Marvila, M.; Azevedo, A.R.G.; Franco de Carvalho, J.M.; Ribeiro, J.C.L. Application of Eco-Friendly Alternative Activators in Alkali-Activated Materials: A Review. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Godinho, D. dos S.; Pelisser, F.; Bernardin, A.M. High Temperature Performance of Geopolymers as a Function of the Si/Al Ratio and Alkaline Media. Mater Lett 2022, 311, 131625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Mozgawa, W. Zeolite Layer on Metakaolin-Based Support. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2019, 282, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Ma, Z. Effect of Ground Concrete Waste as Green Binder on the Micro-Macro Properties of Eco-Friendly Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Mortar. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, V.Q.; Jayarathne, A.; Gallage, C.; Dawes, L.; Egodawatta, P.; Jayakody, S. Leaching Characteristics of Metals from Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCA) and Reclaimed Asphalt Pavements (RAP). Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrela, F.; Díaz-López, J.L.; Rosales, J.; Cuenca-Moyano, G.M.; Cano, H.; Cabrera, M. Environmental Assessment, Mechanical Behavior and New Leaching Impact Proposal of Mixed Recycled Aggregates to Be Used in Road Construction. J Clean Prod 2021, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotti, A.; Plizzari, G.; Sorlini, S. Leaching Behaviour of Construction and Demolition Wastes and Recycled Aggregates: Statistical Analysis Applied to the Release of Contaminants. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).