1. Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) exhibit unique optical properties due to their surface plasmon resonance (SPR), where conduction electrons on the particle surface collectively oscillate in response to specific light wavelengths. This phenomenon results in strong absorption and scattering of light, with the SPR peak’s position influenced by factors such as particle size, shape, aggregation state, and the surrounding medium’s refractive index. Incorporation of AuNPs into silica materials leads to nanocomposites which can be applied as catalysts or ceramic pigments. One of the oldest and most prominent red glass pigments is the Purple of Cassius, consisting AuNPs in silicate matrices using Sn

2+ as a reduction agent [

1,

2,

3]. The development of nanotechnology gives powerful instruments for the preparation of silica composites, containing gold nanoparticles using a wide variety of reduction agents or physicochemical techniques [

4,

5,

6]. By combining nanotechnological approaches with Mie theory based calculations nanocomposites with tunable optical and textural properties can be obtained. Moreover, silica doped with AuNPs, SiO

2:AuNPs, is a promising multifunctional material with potential applications in photothermal therapy, drug delivery and cell bioimaging [

7,

8].

Sol-gel technology is a method for producing materials, by a chemical process that involves the conversion of a solution (sol) into a solid (gel) phase. The process involves the hydrolysis and condensation reactions of metal alkoxides or metal salts in a liquid medium, usually water or alcohol. Sol-gel technology is used in a wide range of applications, including the production of ceramics, glasses, coatings, fibers and catalysts. One of its key advantages is the ability to form materials at relatively low temperatures, which is particularly beneficial for certain applications. An additional advantage of the sol–gel process lies in its ability to promote molecular-level homogenization of multicomponent systems, thereby enabling the formation of uniformly doped powders as well as bulk xerogels or aerogels, depending on the selected drying method [

9].

Recently, we developed a specific and efficient one-pot sol-gel method for preparing silica powders doped with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), using 1-dodecanethiol, tetraethoxysilane, and tetrachloroauric acid [

4,

7,

8]. The reduction occurs upon heating and the resulting powders become irreversibly red–pink colored. In this way, a red–purple ceramic pigment is produced without the use of Sn²⁺ as a reducing agent, unlike in the traditional synthesis of Purple of Cassius [

1,

5]. In our previous studies, certain aspects, such as the porosity of the obtained powders and the temperature required for ceramic pigment formation, have remained open questions. From a physicochemical point of view, thermal treatment may induce crystallization of the silicate matrix, as well as, agglomeration and coalescence of the gold nanoparticles, which could drastically alter the physical properties of the resulting nanocomposites. From the perspective of a physical description of the optical properties of ceramic pigments based on gold nanoparticles, the development of an appropriate algorithm—grounded in Mie theory for polydisperse powders, is more than necessary.

This study builds upon our previous work and aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the influence of temperature on the optical and textural properties of nanocomposites synthesised via a novel heating method. This approach employs 1-dodecanethiol, tetraethoxysilane, and tetrachloroauric acid as precursors, leading to the formation of highly porous SiO₂:AuNPs ceramic pigments at heating.

3. Discussion

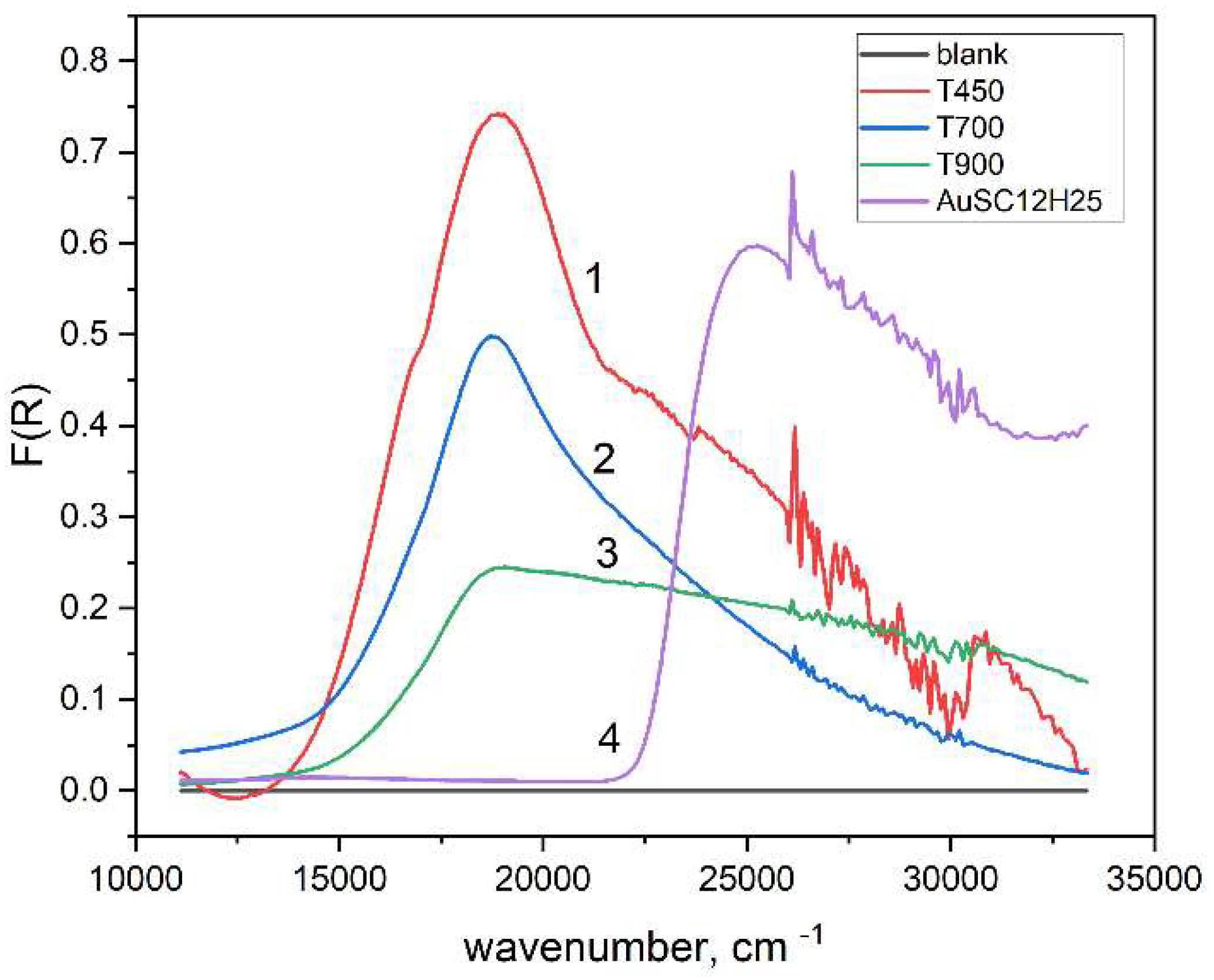

According to Mie’s theory, the red-violet color of AuNPs is attributed to the fraction with dimensions up to about 50 nm. The intensity of the absorption peaks depends on the number of nanoparticles, while the color depends on their size and surroundings. Mie’s theory explains optical properties via the dielectric permittivity of AuNPs, which depends on the wavenumber

through the Drude model. In this case the corresponding spectral intensity is well approximated via the Lorentzian function [

11,

14].

where

is the height of the

k-th peak with maximum at

and full width at half maximum (FWHM)

. From the latter one can calculate the mean free path

of electrons in a gold nanoparticle, where

is the speed of light and

is the Fermi velocity of gold. The maximum of the peak depends strongly on the medium around the particle via its dielectric constant

where

is the Langmuir plasmon frequency of gold. Because

is very high, only electrons can follow the resonant frequency in the surroundings. Thus, the corresponding high frequency dielectric constant

equals to the square of the refractive index. Hence, one can calculate

via Mie’s theory as well from the experimental spectra [

11].

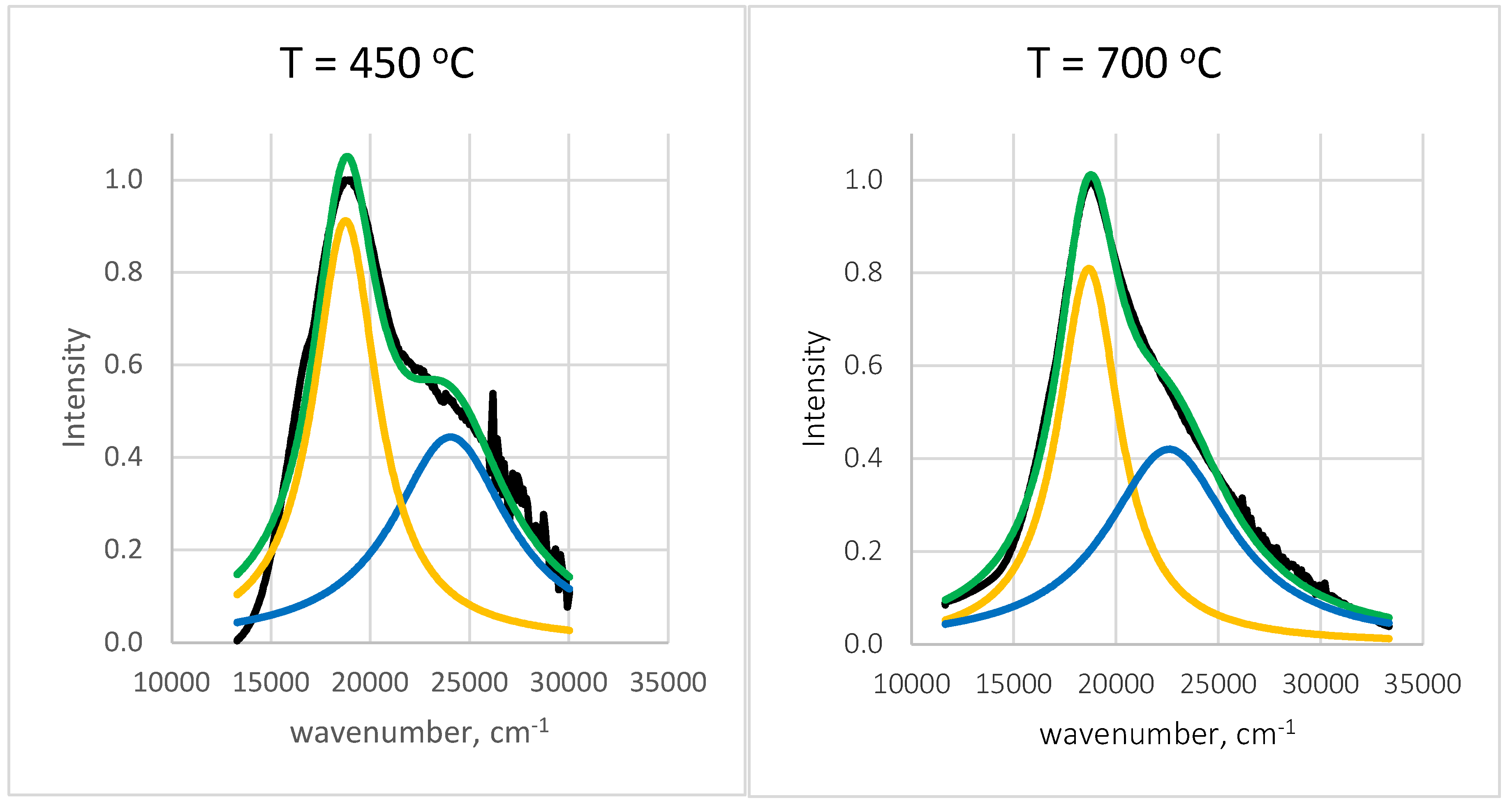

The spectra from

Figure 11 are fitted using a superposition of two Lorentzian functions, each representing a population of gold nanoparticles with distinct sizes and surrounding environments.

The results of the conducted procedure are summarized in

Table 2:

As is seen, the two Lorentzian peaks are slightly affected by temperature. The first one corresponds to gold nanoparticles with mean free path nm surrounded by a medium with refractive index , while the second lower peak corresponds to nm and . Obviously, the larger AuNPs are in close contact with the SiO2 matrix, which possesses a refractive index about , while the smaller ones are distributed in some pores. The areas of the two Lorentzian peaks are commensurable, which means equal volume fraction of the two kinds of gold nanoparticles.

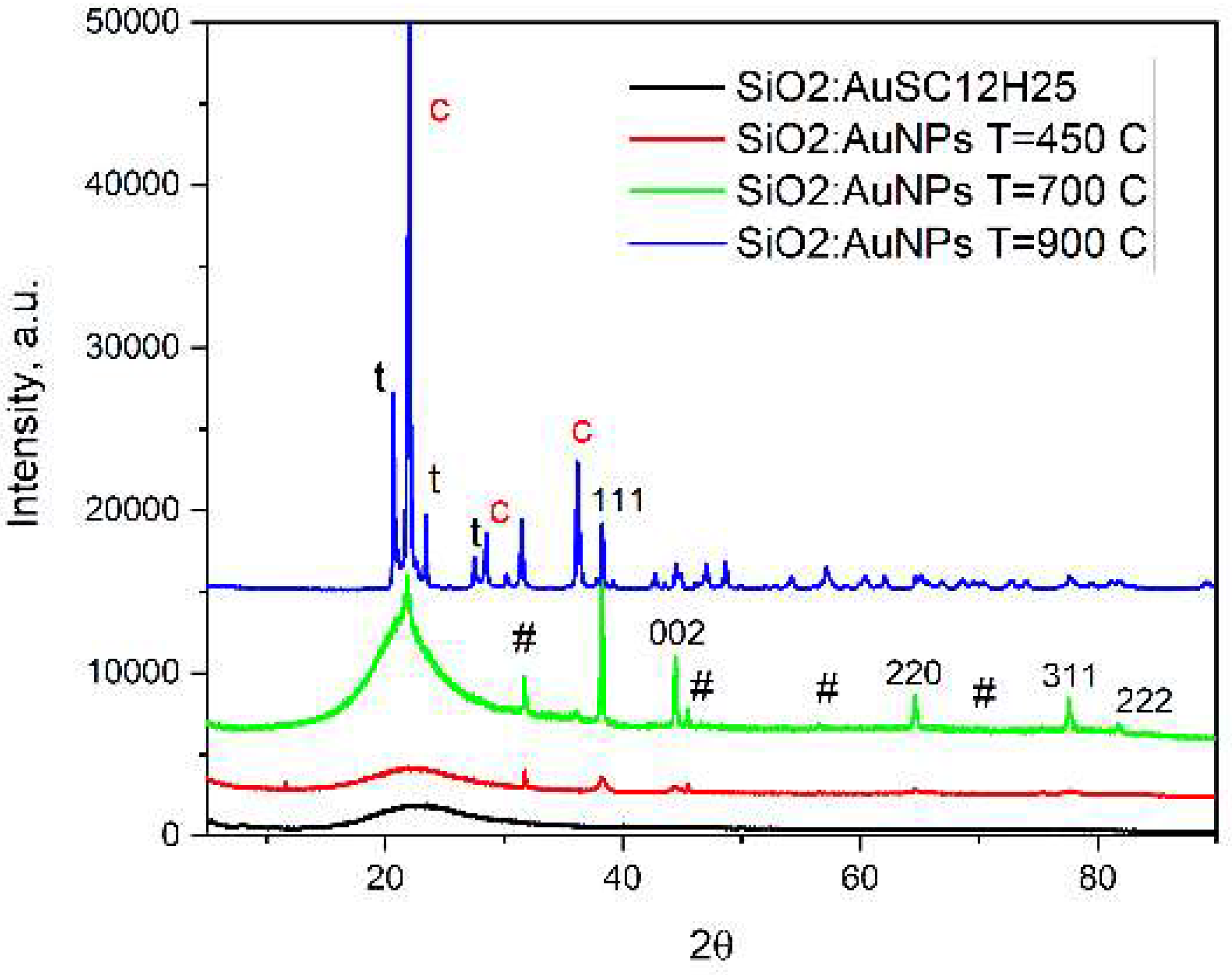

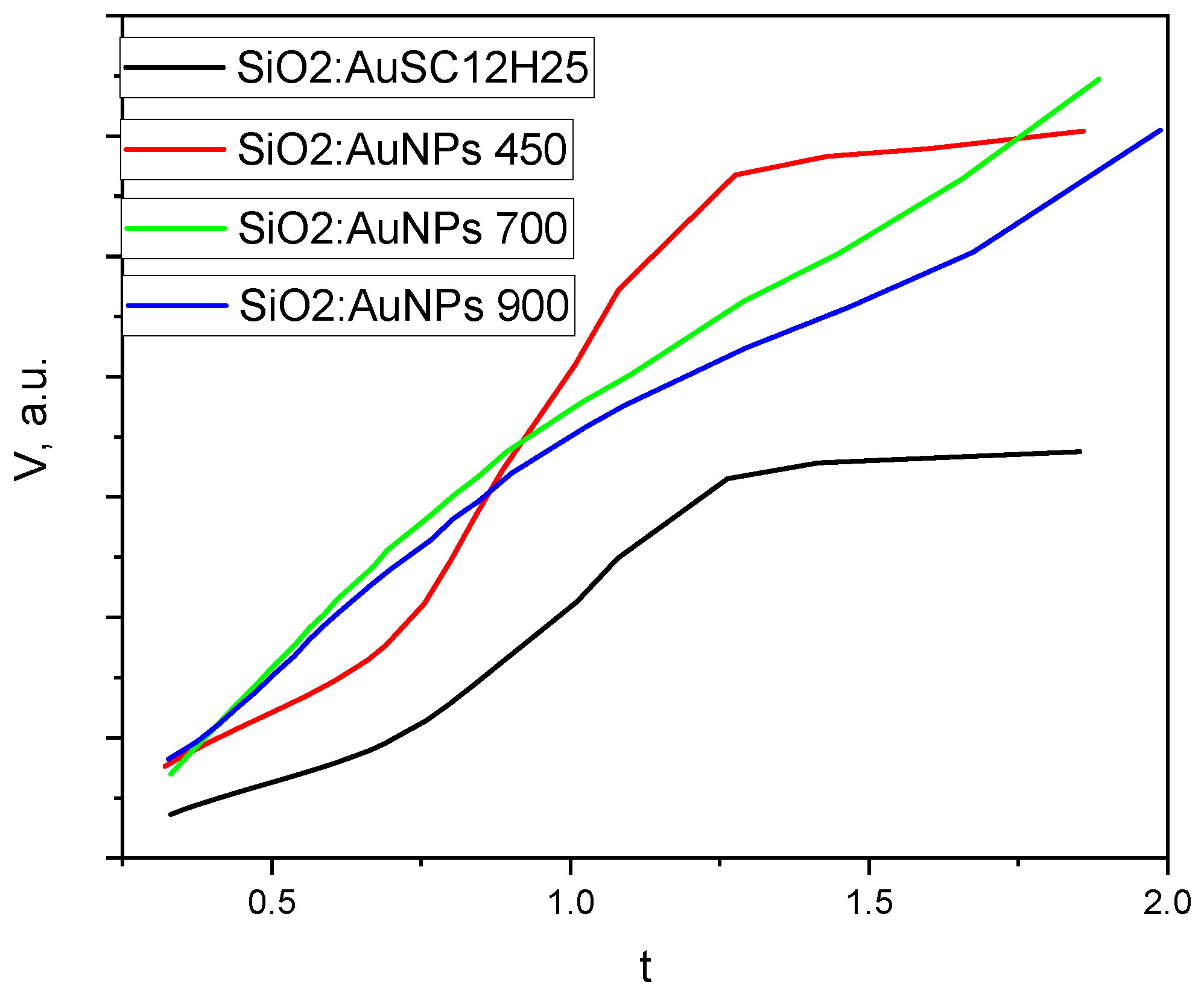

At heating of SiO

2:Au-SC

12H

25, an irreversible decomposition reaction of Au-SC

12H

25 takes place, which produces AuNPs (Au

0) and volatile organosulfur products. It follows, that the sintering temperature plays a crucial role for the physical properties of the obtained nanocomposite. It is well established, that the formation of gold particles during reduction follows the Finke–Watzky mechanistic model, which is characterized by a slow nucleation, followed by a rapid chemical reaction and crystal growth [

15,

16]. In our case, the effect of temperature is two-fold: its’ increase induces the size-dependent melting of gold nanoparticles followed by coalescence. As a result the fraction of “giant nanocrystals” observable by TEM, which do not contribute significantly to the absorption intensity of the SPR peak at 530 nm. Our results (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) indicate that low heating temperatures prevent nanoparticle agglomeration, thereby increasing their concentration and consequently enhancing the absorption intensity in such samples. The increase in sintering temperature also leads to a change in the silicate matrix. While at 450 °C the matrix is amorphous, at 900 °C it becomes crystalline (

Figure 1,

Table 1). In our view, this sample heated at 900

oC represents the first successful attempt to obtain cristobalite doped with gold nanoparticles. The occurrence of monoclinic low tridimite nanocrystals, accompanying the crystallization of cristobalite is in accordance with the results published in [

17,

18,

19]. From a general physico-chemical point of view, the formation of metastable silica phases at cooling is explained by the Ostwald’s rule of stages [

18]. The densification of the powders (

Table 1, calculated densities) at heating is combined with a drastical decrease of their specific surface area and porosity, combined with a low temperature crystalization of the silica matrix. The pore diameter decreases twice at increased heating temperature, showing the matrix densification after heating. The amorphous samples here posses a high specific surface area (200-330 m

2/g), typical of aerogel-like silicate materials, and show promise as potential catalysts or glaze pigment [

20]. The catalytic properties of SiO

2:AuNPS for different chemical reactions are well known [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. An intriguing trend is observed in

Table 1 regarding the thermal behavior of the samples. Upon heating to 450 °C, the specific surface area increases, likely due to the combustion of the organic component. A similar approach—thermal decomposition or evaporation of organic components—is commonly employed in the synthesis of mesoporous, thermally insulating aerogel materials, often utilizing natural raw materials [

21]. At higher temperatures, however, a significant decrease in surface area occurs as a result of powder densification. This densification also affects the pore structure, with the average pore diameter decreasing from approximately 10 nm to around 5 nm. Furthermore, the pore size distribution curve shifts, indicating changes in the uniformity and range of pore sizes as a function of temperature.

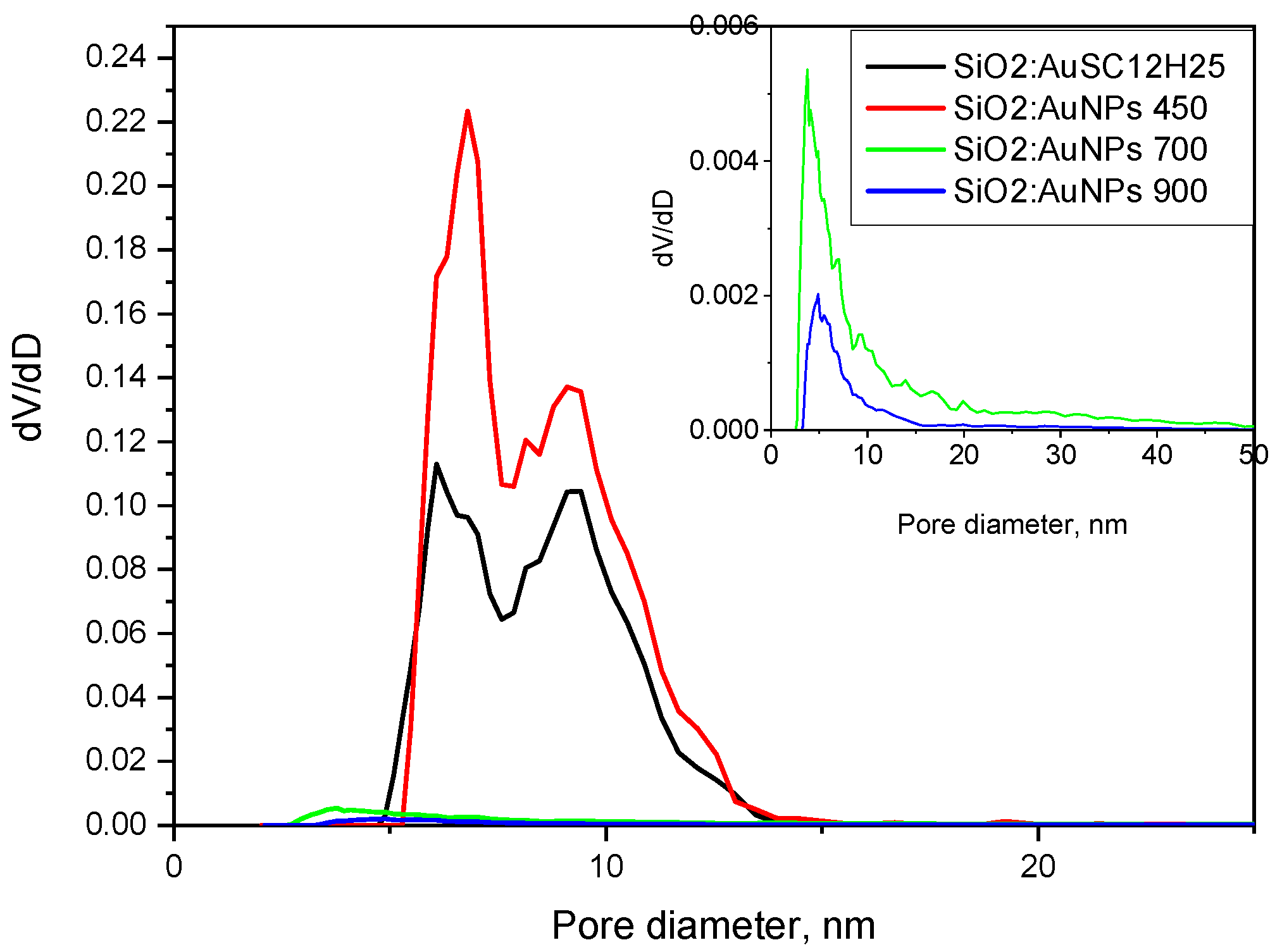

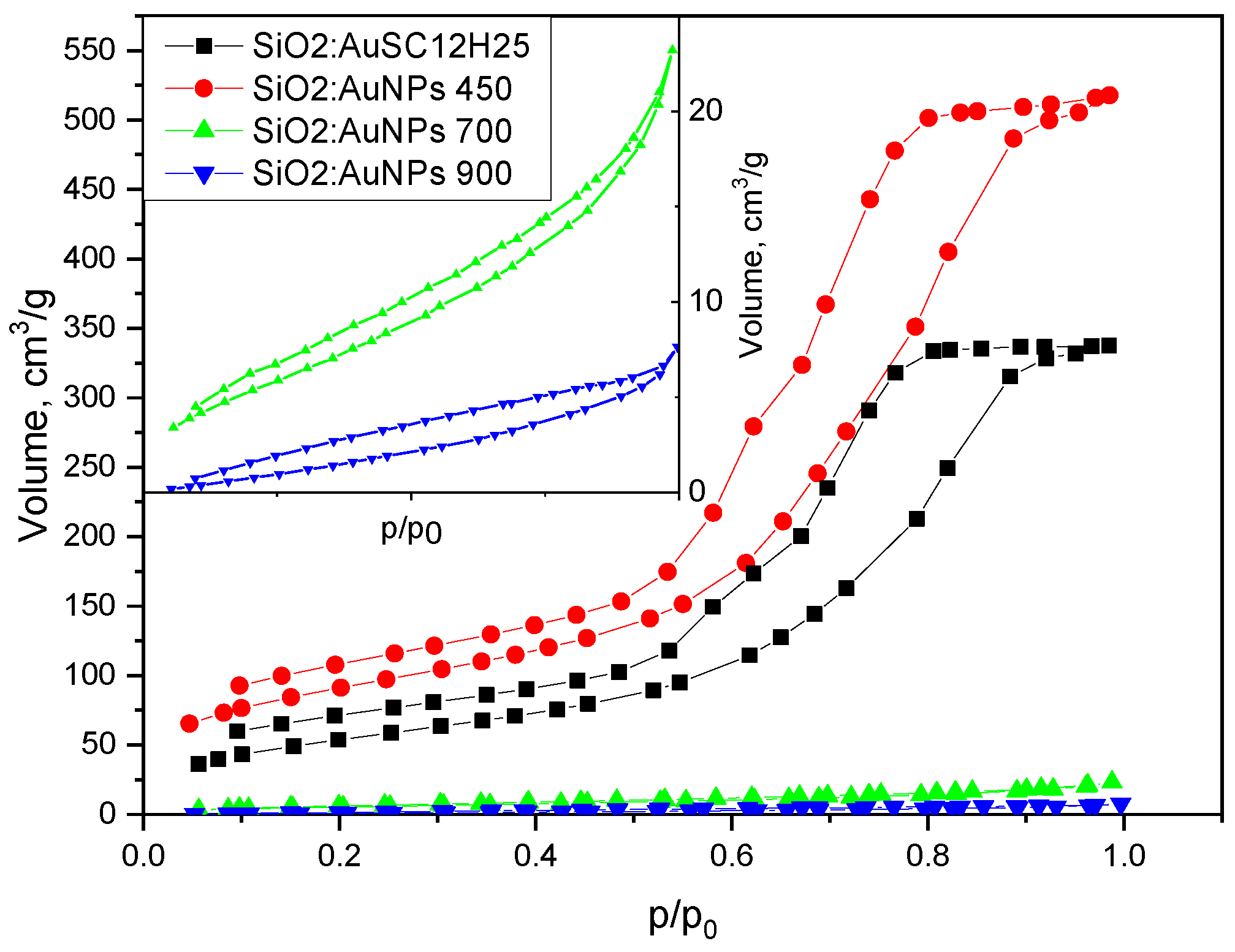

An analysis of the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) reveals that all samples exhibit hysteresis loopsm characteristic of Type IV isotherms, which are typical for mesoporous materials with pore diameters in the range of 2–50 nm (IUPAC classification) [

27,

28,

29,

30]. A t-plot was constructed using the de Boer standard isotherm (Harkins–Jura or de Boer model), as shown in

Figure 12 [

31,

32]. The sample isotherm is plotted versus the standard isotherm and the deviations are interpreted in the following paragraphs. Both the non-heated sample and the sample annealed at 450 °C display H2(b)-type hysteresis loops [

28], typically associated with complex pore structures and pore size polydispersity. This type of loop indicates a closed-pore morphology, often with “ink-bottle” shaped pores, where narrow necks restrict desorption. Such structures result in complete pore filling at high relative pressures and steep desorption branches due to delayed evaporation from the pore interiors. These features are consistent with the pore size distribution data (

Figure 8), which show that the non-heated sample has an average pore diameter of 10 nm and a bimodal distribution with peaks at 6 and 9.4 nm. The sample annealed at 450 °C exhibits a slightly smaller average pore diameter (9.7 nm), with peaks centered at 6.8 and 9 nm. The reduced pore size contributes to the increased specific surface area observed in the thermally treated sample. In contrast, the samples annealed at 700 °C and 900 °C still exhibit Type IV isotherms but with markedly different hysteresis loop types. These samples show significantly reduced specific surface areas (21 and 9 m²/g, respectively) and smaller average pore diameters (6.9 and 5 nm, respectively) compared to those treated at lower temperatures. The sample heated at 700 °C displays an H3-type hysteresis loop, commonly attributed to slit-like pores formed between plate-like particles or aggregates. The sample annealed at 900 °C exhibits a H4-type hysteresis, which shares similar structural origins with H3 but is generally associated with narrow slit-shaped pores and mesoporous materials. Notably, both samples lack saturation at high relative pressures, suggesting the presence of non-rigid porous frameworks capable of structural swelling [

28]. The low closure points of the hysteresis loops further imply a broad pore size distribution. These interpretations are supported by the calculated t-curves (

Figure 12).

The t-plots for SiO₂:AuNPs and SiO₂:AuNPs_450 show significant deviations from the linear trend at high relative pressures, consistent with mesoporous oxide materials exhibiting capillary condensation. In contrast, the t-curves for SiO₂:AuNPs_700 and SiO₂:AuNPs_900 conform relatively well to a straight line, with only minor deviations at intermediate and high pressures. The lower adsorbed volume at high relative presure might be connected to the presence of some mesopores in the gels. This near-linear behavior resembles that of a Type II isotherm, typically observed for non-porous or macroporous materials [

28], and suggests metastability in the adsorbed multilayer and delayed condensation due to high pore curvature radii and a non-rigid gel structure. The findings are consistent with the phase analysis of the sample SiO₂:AuNPs_900. Cristobalite and tridymite have layered structures and low specific surface areas due to microporosity – 2 m

2/g and 2,8 to 7.4 m

2/g respectively, together with a density about 2.30 g/cm

3 [

33,

34].

4. Materials and Methods

The following chemicals were used for the syntheses of the nanocomposite materials: absolute ethanol (EtOH), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), tetrachloroauric acid tri-hydrate (HAuCl

4⋅3H

2O), 1-dodecanethiol (DDT), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and distilled water. All chemicals were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. The chemicals were of analytical grade. The catalyst used in this study consists of water (H

2O), ethanol (EtOH) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Reflectance measurements were performed on a spectrometer PE Lambda 35 (PerkinElmer LLC, USA) with a Spectralon

®-coated integrating sphere and the Kubelka–Munk function F(R) was calculated from the diffuse reflectance R for all samples [

35]. The spectral features were analyzed by a Lorentzian fit to extract peak position (xc), full width at half maximum (FWHM) and integrated absorption intensities (A). Labsphere Spectralon ™ Diffuse Reflectance white and black standards SRS-99–010, SRS-02–010 and a Ho

2O

3 powder were used as a reference.

The structure and microstructure of all samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction with Cu-Kα (1.5418 Å) radiation (Empyrean, Malvern Panalytical X-ray diffractometer), at a step of 2θ = 0.05

o and counting time 4 s/step. The mean crystallite sizes are calculated using Scherrer’s equation from the 111 peak of Au. The x-ray diffraction data are analyzed using the PowderCell software [

36].

TEM analyses were performed using an electron microscope JEOL, model JEM 2100 at 200 kV with LaB

6 filament, manufactured in Japan and CCD camera - Gatan Orius 1000. The model of the STEM – EDAX is Oxford Instruments, model X-Max 80T. The results of the TEM image analysis, are conducted using the ImageJ software [

37]. Over 20 images containing a total of more than 300 crystals were analyzed.

The texture characteristics of the aerogel powders were determined by low temperature (77.4 K) nitrogen adsorption in a Quantachrome Instruments NOVA 1200e (Boynton Beach, FL, USA) instrument. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were analyzed to evaluate the following parameters: the specific surface areas (S

BET) were determined on the basis of the BET equation, and the total pore volumes (Vt) and associated average pore diameters Dav were estimated at a relative pressure close to 0.99. All the samples were outgassed for 16 h in vacuum at 150

oC before the measurements. The pore size distributions (PSD) were calculated by Nonlocal Density Functional Theory (NLDFT) [

38].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and T.S.; methodology, R.T., D.S. and N.D.; investigation, L.M., D.S., N.D., T.S. and R.T.; resources, T.S.; data curation, D.S., S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G. , R.T., L.M., N.D, D.S.; visualization, R.T., N.D., D.S.; supervision, T.S. and S.G.; project administration, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

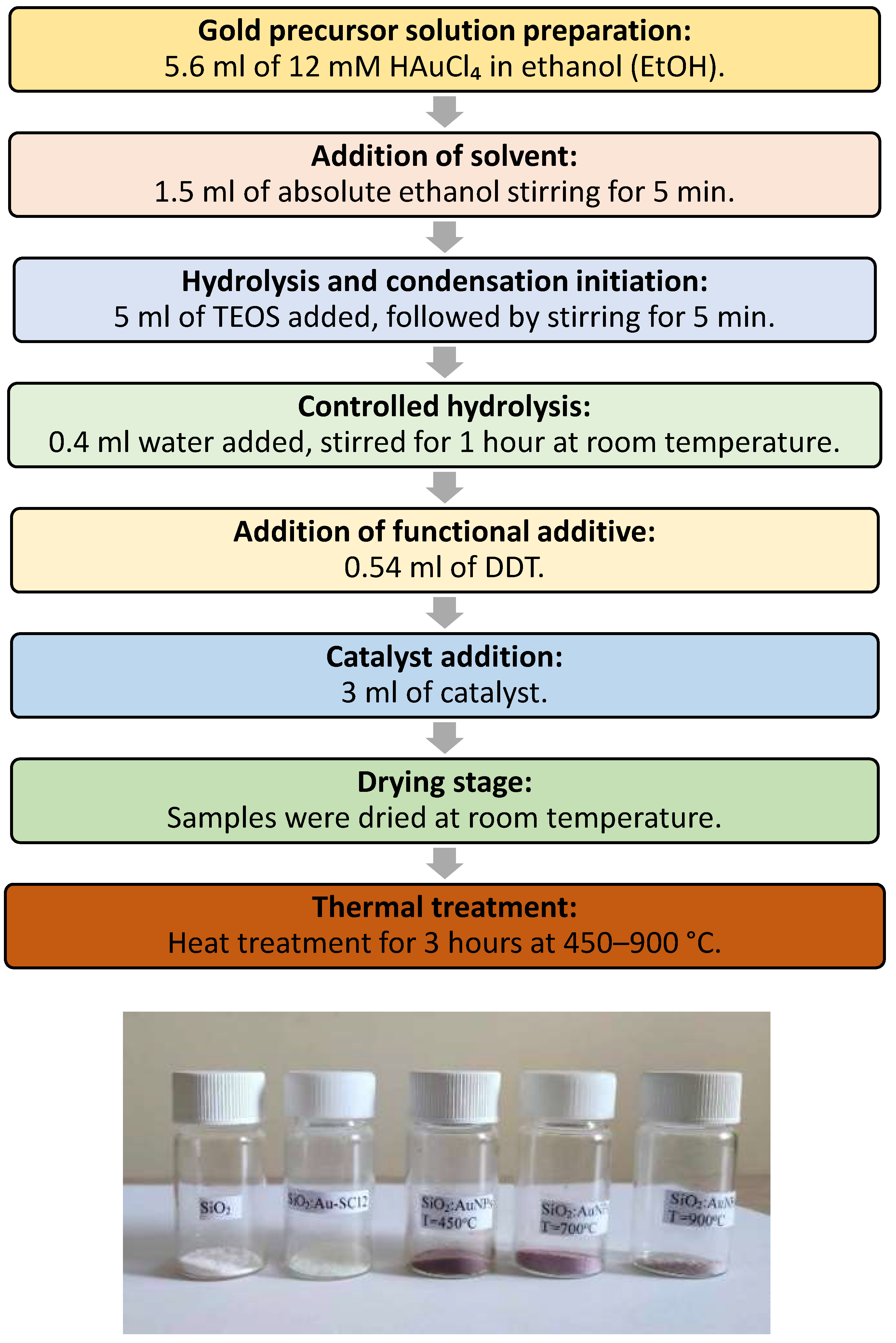

Figure 1.

Preparation scheme for SiO2:AuNPs at heating, starting from SiO2:AuSC12H25 and photographs of the obtained ceramic pigments.

Figure 1.

Preparation scheme for SiO2:AuNPs at heating, starting from SiO2:AuSC12H25 and photographs of the obtained ceramic pigments.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction results of the investigated samples. Sample notations: NaCl 01–080–3939 traces are designated with #. Peaks from Au 01–073–9564 are indexed (hkl). The peaks from tetragonal low cristobalite, (ICSD 34932) and monoclinic low tridymite, (ICSD 176) are designated with c and t, respectivelly (blue curve, T=900 oC).

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction results of the investigated samples. Sample notations: NaCl 01–080–3939 traces are designated with #. Peaks from Au 01–073–9564 are indexed (hkl). The peaks from tetragonal low cristobalite, (ICSD 34932) and monoclinic low tridymite, (ICSD 176) are designated with c and t, respectivelly (blue curve, T=900 oC).

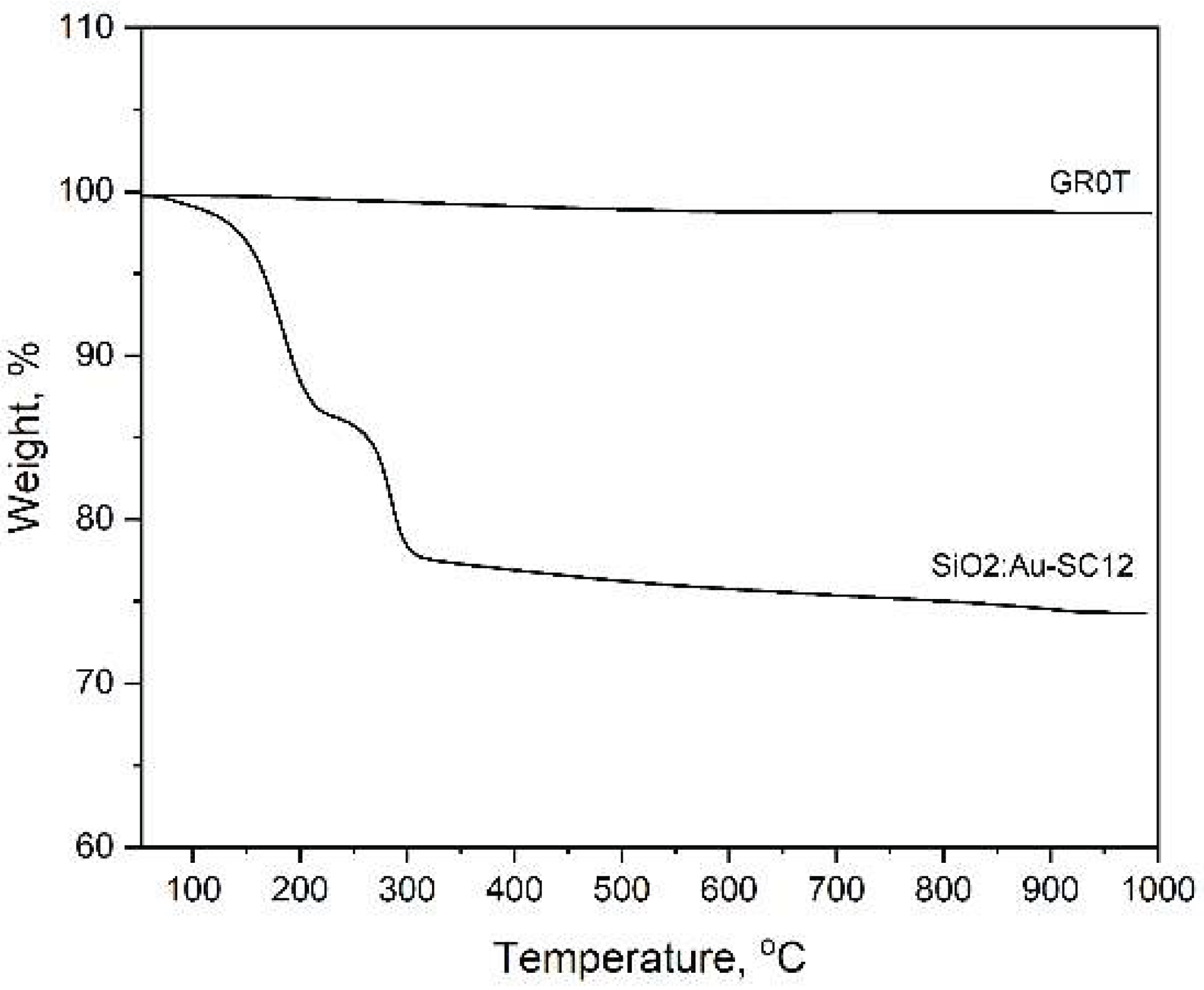

Figure 3.

TG curves of a sample obtained by thermal treatment of 1-dodecanethiol embedded in a silicate gel (bottom curve). The upper curve represents the reference sample, consisting of pure silica, heated at 700 oC (GR0T).

Figure 3.

TG curves of a sample obtained by thermal treatment of 1-dodecanethiol embedded in a silicate gel (bottom curve). The upper curve represents the reference sample, consisting of pure silica, heated at 700 oC (GR0T).

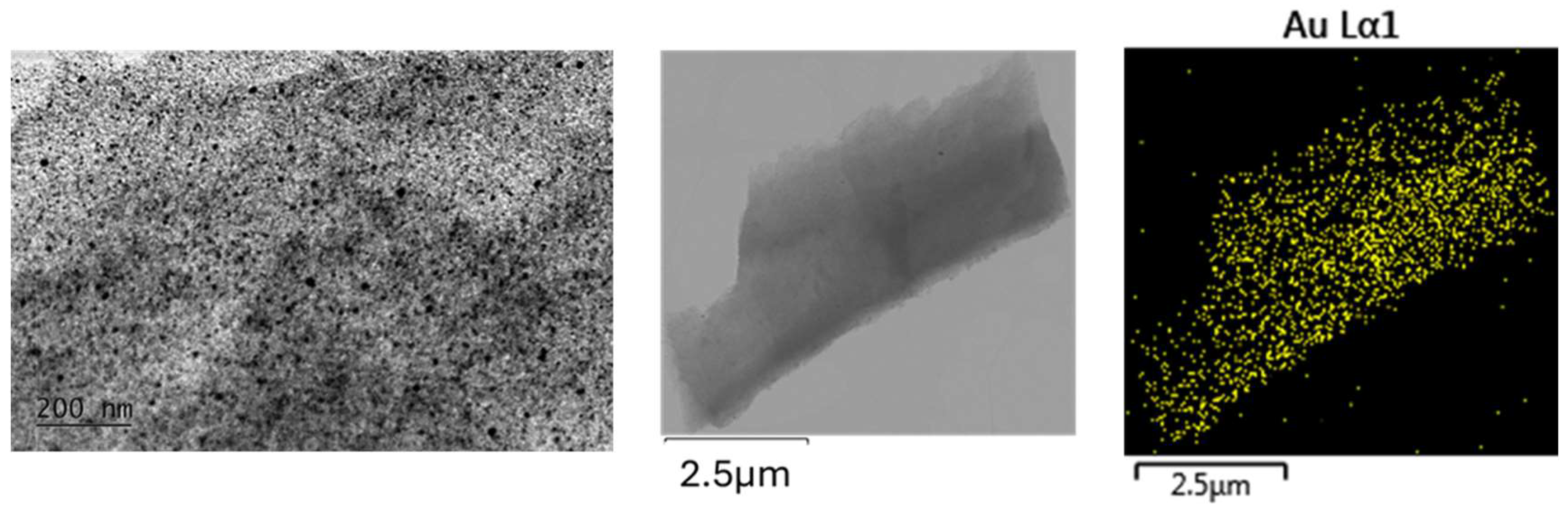

Figure 4.

TEM image at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS of nanocomposites obtained at a temperature of T = 450 °C. The nanocrystallites exhibit sizes well below 40 nm.

Figure 4.

TEM image at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS of nanocomposites obtained at a temperature of T = 450 °C. The nanocrystallites exhibit sizes well below 40 nm.

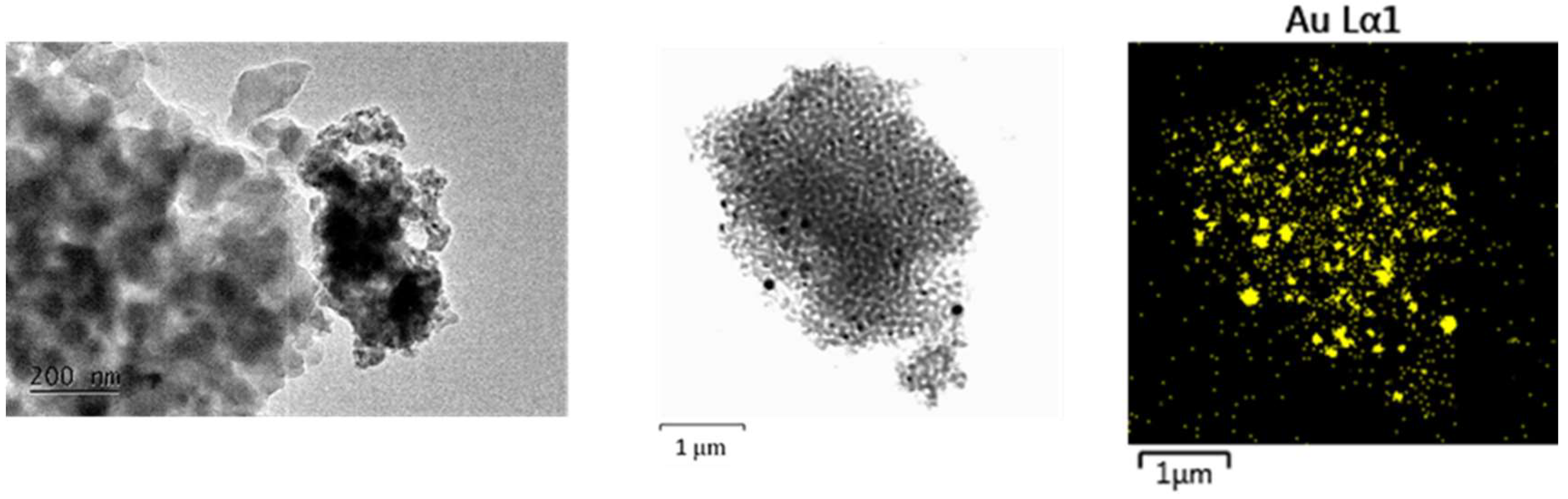

Figure 5.

TEM at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS mapping microanalysis of gold nanoparticles dispersed in a silicate matrix. Heating temperature T=700 oC.

Figure 5.

TEM at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS mapping microanalysis of gold nanoparticles dispersed in a silicate matrix. Heating temperature T=700 oC.

Figure 6.

TEM at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS mapping microanalysis of different sized nanoparticles in crystalline SiO2:AuNPs, heating temperature T = 900 oC AuNPs.

Figure 6.

TEM at 20k magnification and STEM - EDS mapping microanalysis of different sized nanoparticles in crystalline SiO2:AuNPs, heating temperature T = 900 oC AuNPs.

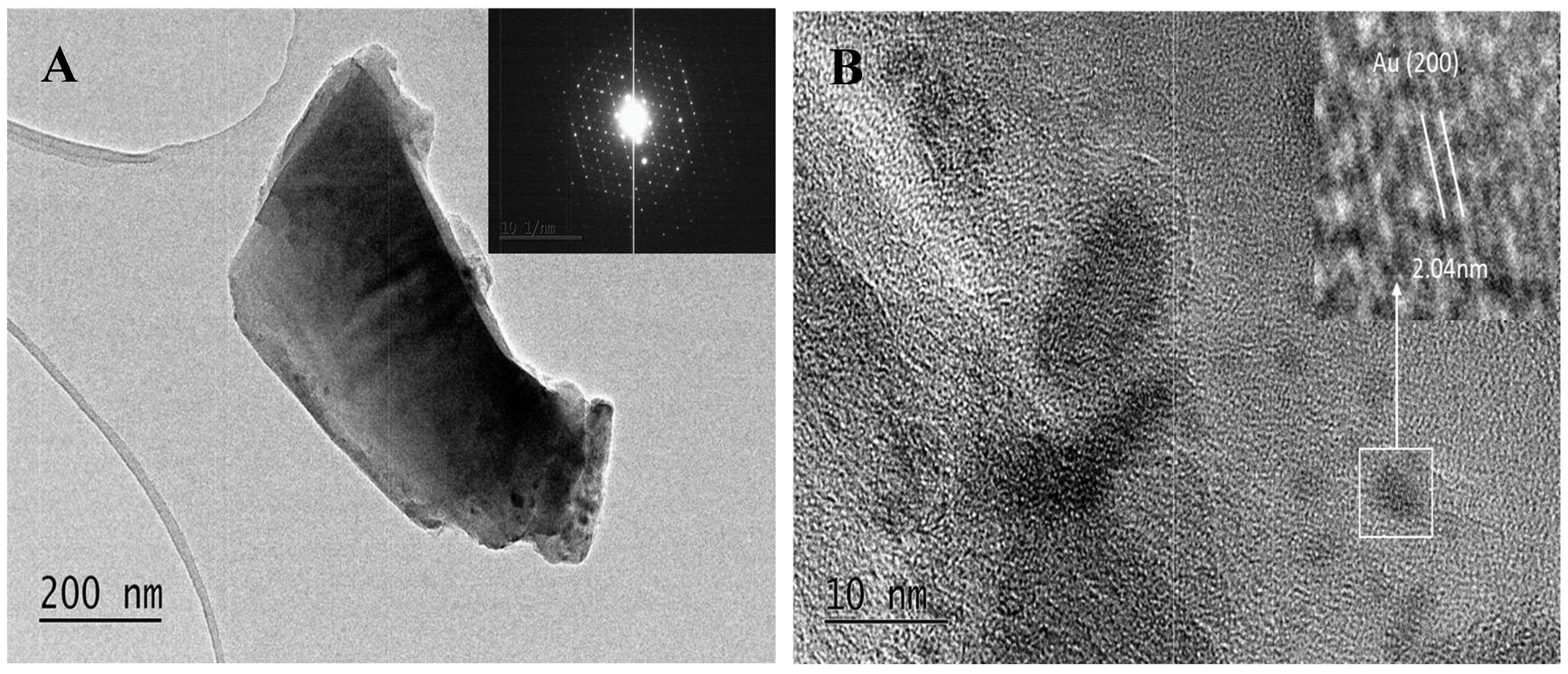

Figure 7.

TEM micrograph (A) at 20k magnification and selected area electron diffraction (inset) and HRTEM (B) micrograph of crystalline SiO2:AuNPs, heating temperature T = 900 oC.

Figure 7.

TEM micrograph (A) at 20k magnification and selected area electron diffraction (inset) and HRTEM (B) micrograph of crystalline SiO2:AuNPs, heating temperature T = 900 oC.

Figure 10.

Differential reflectance spectra (reference SiO2 powder) of micropowders, heated at different temperatures. Samples: 1 – SiO2:AuNPs, T=450 oC; 2 - SiO2:AuNPs, T=450 oC; 3 – T=900oC; 4 – SiO2:AuSC12H25.

Figure 10.

Differential reflectance spectra (reference SiO2 powder) of micropowders, heated at different temperatures. Samples: 1 – SiO2:AuNPs, T=450 oC; 2 - SiO2:AuNPs, T=450 oC; 3 – T=900oC; 4 – SiO2:AuSC12H25.

Figure 11.

Deconvolution spectral results of normalized diffuse reflectance spectra for samples annealed at different temperature. Black lines represent experimental data.

Figure 11.

Deconvolution spectral results of normalized diffuse reflectance spectra for samples annealed at different temperature. Black lines represent experimental data.

Figure 12.

T-plot for the samples. Heating temperatures are shown.

Figure 12.

T-plot for the samples. Heating temperatures are shown.

Table 1.

Textural properties of the investigated gels. The doping level of Au is 0.03% in all samples. The densities ρcalc are obtained using the values for amorphous silica and cristobalite, 2.19 g/cm3 and 2.30 g/cm3, respectively.

Table 1.

Textural properties of the investigated gels. The doping level of Au is 0.03% in all samples. The densities ρcalc are obtained using the values for amorphous silica and cristobalite, 2.19 g/cm3 and 2.30 g/cm3, respectively.

| Sample |

SBET,

m2/g |

Vt,

cm3/g |

Dav

nm |

T

oC |

ρcalc g/cm3

|

| SiO2:AuSC12H25 |

204 |

0.52 |

10.0 |

- |

1.02 |

| SiO2:AuNPs |

330 |

0.80 |

9.7 |

450 |

0.8 |

| SiO2:AuNPs |

21 |

0.04 |

6.9 |

700 |

2.01 |

| SiO2:AuNPs |

9 |

0.01 |

5.0 |

900 |

2.24 |

Table 2.

Photophysical parameters of the investigated nanocomposites extracted from their diffuse reflectance spectra.

Table 2.

Photophysical parameters of the investigated nanocomposites extracted from their diffuse reflectance spectra.

| Т [°C] |

|

[cm-1] |

[cm-1] |

|

[cm-1] |

[cm-1] |

| 450 |

0.91 |

18761 |

3911 |

0.44 |

24048 |

7095 |

| 700 |

0.81 |

18668 |

3666 |

0.42 |

22599 |

7457 |