1. Introduction

In a natural environment water, food, and energy cycles occur as both medium of storage and transmission, and include biotic and abiotic components. This includes physical, chemical, and other natural factors in accordance with ecosystem characteristics. These factors—climate, geology, topography, hydrology—ultimately form the background of human existence. A suitable infrastructure that support processes "inflow-stock-supply" (ISS) of existential resources is essential to support civilization sustainability. To understand the complex interactions of climate and sustainability, understanding the long-term shifts in climate history becomes crucial.

Water, an integral component of climate, sustains life on Earth and has also been changing across generations. It is a natural resource with a unique value and awareness that allows it to sense even minute imbalances in the life-sustaining systems. However, water, food, and energy form an integrated and interdependent nexus at the heart of sustainable development [

1]. Existence and prosperity of mankind depends on access to good quality water, which has been the key to any sustainable civilization [

2]. The same applies to food, the supply and quality of which depend on the quantity and quality of water. Water is thus the basis for all civilizations since it represents the most evident point of interaction between natural history and the history of humankind [

3]. The story of water is thus a story of civilizations, conditioned by climate, hydrology, geomorphology, and biology. Through water, we are physically and spiritually connected to each other and connected to living beings and the non-living environment on Earth. Such vision of the role of water is a prerequisite for the sustainability of society.

This study examines long- and short-term relationships between climate variability, water civilization and history in the region of Dalmatia in Croatia (

Figure 1). The study hypothesizes that climate crises are fundamentally water crises—and, by extension, civilization crises. With this hypothesis, this study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the functioning of natural and social systems during climate change period and their interdependence, and contribute to historical awareness and sensitivity in the discussion of water culture and civilization. The topic is complex, multidisciplinary, and hence challenging because historical data are general and modest. Literature that comprehensively addresses this topic is rare, so for the purposes of the research, a methodology and tools that simplify the assessment of changes and impacts were applied. The study focuses on the period from 750 BCE to 900 CE, exploring how climate, natural systems and water-centered civilization interacted over time, and why.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

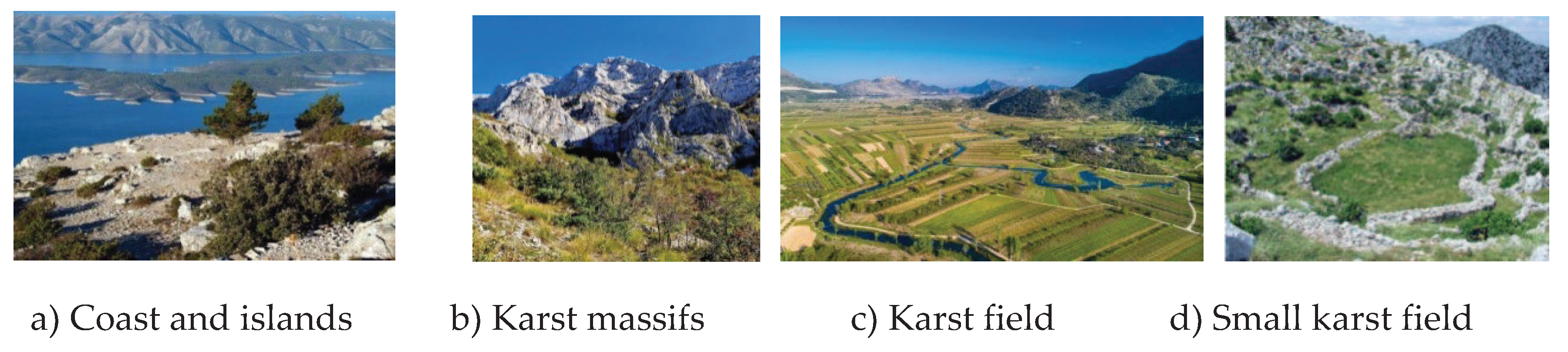

Dalmatia is a regional term referring to the area of the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea, which encompasses the catchment area of the rivers Zrmanja, Krka, Cetina and Neretva, coast and islands (

Figure 1). The territory of today's region of Dalmatia is approximately 400 km long and 70 km wide, and includes 942 islands or islets, while the mainland coastal strip is about 1,200 km long. The name Dalmatia comes from the tribes called

Delmati, who lived in the area of the Illyrian region. The Romans, after defeating the Dalmatians in 29 BCE, renamed their province of Illyricum to the Province of Dalmatia (

Figure 1) [

4].

According to the Köppen classification, the climate is type C in the coastal area and islands (moderately warm rainy climate) and type D in the hinterland (snowy rainy) [

5]. Insolation and temperature increase from north to south and from the mainland to the islands. The average annual humidity values at the coast and in the continent are 70% and 80%, respectively. Annual precipitation is 800–1600 mm, and increases with the distance from the coast and with the height of the terrain. The coast gets most of its rainfall in winter, while inland areas receive more rainfall during the warmer months.

The geology and lithology of the area consists of a karst substratum of limestone and dolomite rocks of various shapes. Karst area is formed by dissolving limestone with water (corrosion), which contains carbon dioxide (CO

2); in doing so, calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) turns into calcium bicarbonate (Ca(HCO

3)

2), which is water soluble. Karst is an open system that quickly exchange-export energy, matter, and entropy with environment. The karst hydrogeological system maintains a low entropy state by increasing entropy at its discharge points in the environment. Thus, disorder (kinetic activity) is driven by groundwater levels—the lower the water level or flow, the lower the disorder [

6]. This characteristic sustains the karst hydrological system in dry periods.

Surface erosion and exogenous processes change the surface forms of the relief and deep erosion and endogenous processes create cracks in the interior of the limestone massif [

7]. Corrosion changes rock surfaces (erodes and dissolves) and the resulting cracks widen and connect to a network of underground cavities and channels, creating a specific groundwater system, that is in contact with seawater. Groundwater exchanges water and heat energy with seawater, influencing its salinity and temperature, as well as surrounding terrestrial environment. The area is thus rich in marine biota, forming a specific local climate while mitigating temperature extremes.

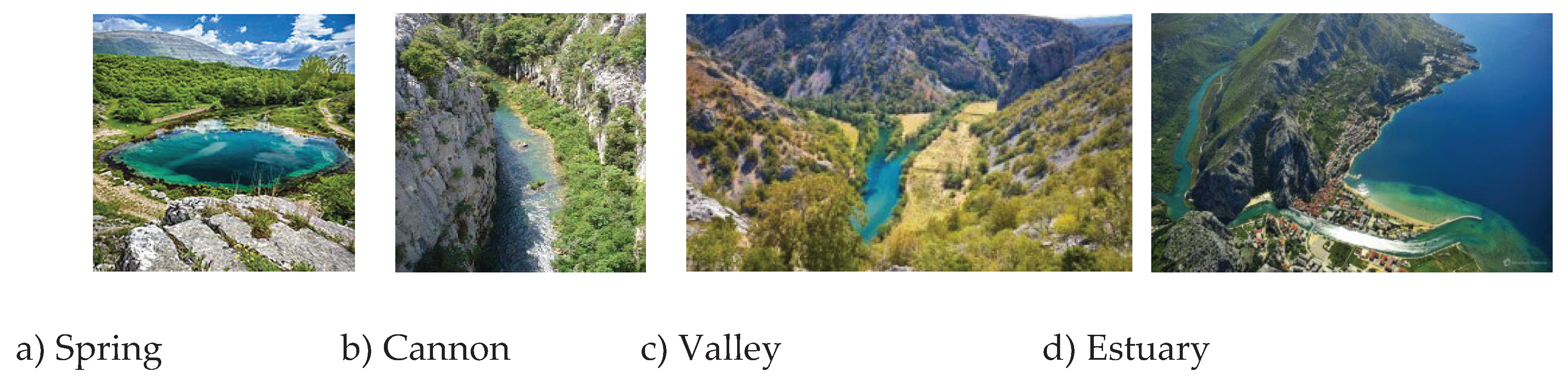

The force of gravity and water flow form canyons, valleys, sinkholes, and estuary. The karst area is poor in fertile (deep) soil and biota. River valleys, karst fields, river deltas and coastal alluvial plains show sediment accumulation (

Figure 2). This is why food production in Dalmatia has been quite difficult. However, in summer, agricultural products are supplied to the dry coastal area from the area of continental climate during warm summer period. In winter, coastal products are supplied to the cold continental area. This also applies to livestock that seasonally migrate to areas where grazing conditions are more favorable. That is why, in principle, in Dalmatia, food, water, and wood (energy) supply was not particularly vulnerable to climate change.

The river network owing to high geopotential energy is simple and favorable for the production of hydro power (

Figure 3). From the hydrogeological point of view, a very permeable karst substratum with a complex system of underground water circulation, retention, and outflow of water prevails in the region [

7]. Water flow is maximal in the winter, when the flow changes rapidly, and the least in the dry summer. River deltas in this region absorb runoff from both floods (from rivers) and storms (from the ocean) creating nutrient-rich brackish water that support a diversity of habitats—from uplands to the open waters of the Adriatic Sea. Due to the matrix structure of the lowest part of the aquifer, characterized by a diffuse flow of water, flow in dry summer period is stable and less sensitive to climate, thus ensuring a reliable water supply [

6]. As exploitation of groundwater by dug or drilled wells in hinterland karst is risky, the springs, rivers and well in alluvial zones are mostly captured for water supply. However, rainwater harvesting has been the traditional technique for water supply.

2.2. Scientific Method

Materials required to compile history for a cognitive framework are organized to assess the long- and short-term relationship between climate variability and civilization history [

8]. Then, learning about the history and defining the theory are carried out. By using intuitive and logical knowledge, an effort is made to understand the past in order to explore the future.

The interpretation of changes and interrelationships is viewed qualitatively by applying the concept of thermodynamics of living and social system, because thermodynamic laws unmistakably define variability and sustainability of the system [9, 10]. The climate not only influences the water regime, but also humans, society and the economy, and the driving system into or out of a critical state (maximal entropy). Nature and humans create cycles and “stocks” and “flow” of water, food, and energy of biotic or abiotic components. The strategy of man-made a concept is to satisfy the "predictable" anthropogenic consumption in accordance with the "unpredictable" natural supply. Hence, “stock”, natural or man-made, is considered as a key element for sustainability realization in which systems maintain themselves in organized states far from thermodynamic equilibrium with respect to their environments. Stocks are entropy-dissipative structure: a technology that neutralize (entropic) perturbations during stable climate periods and upgrade the system order during critical climate periods.

Coevolution of historical climatology and human history is seen through the evolution of: water culture and water civilization. Essentially, this had been mostly about “vision”, or a society's ability to ensure reliable water supply for people and the economy, especially concerning water and food sustainability in climatically unfavorable years. Both factors are shaped by the natural system and by the culture and civilization of the society. Therefore, they are accepted as a "cumulative indicator" of the sustainability of civilization, or framework for condition of existence. That includes "existential needs" of nature and man arising from nature itself, and "non-existential needs" which can be physical, ethical, moral, religious, economic, intellectual and similar in nature, depending on the culture and development of society. Man can never give up "existential needs" while "non-existential needs" are practiced if the existing state of the natural and socio-political system allows it. Thus, understanding the link between climate, water culture, and civilization helps analyze social dynamics and historical development.

2.3. Climatic Sensitivity of the Dalmatian Carst Landscape and Water Resources

2.3.1. Climate Change

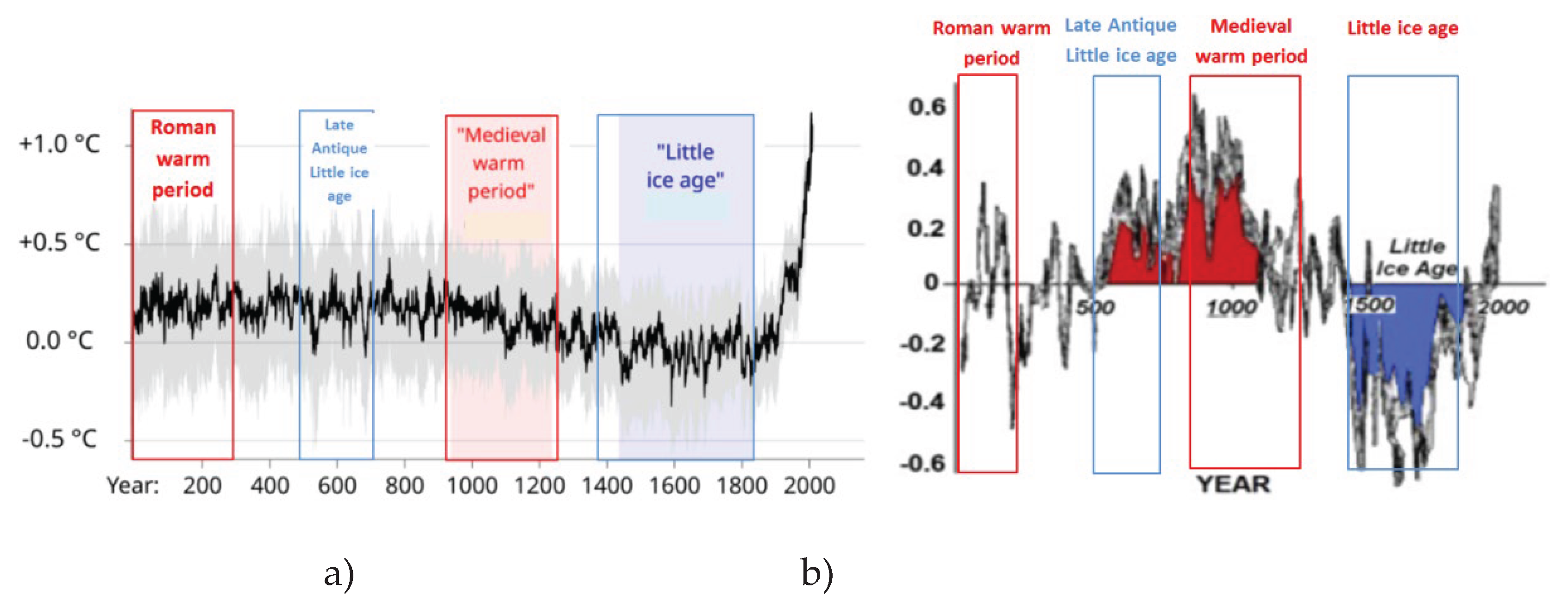

Previous studies have discussed an entire series of reconstructions of temperature and precipitation in the Late Holocene period in order to expand knowledge about the history of climate change (

Figure 4). The results depend on the data used for the reconstruction, so there is no complete agreement on the changes ([11-13]).

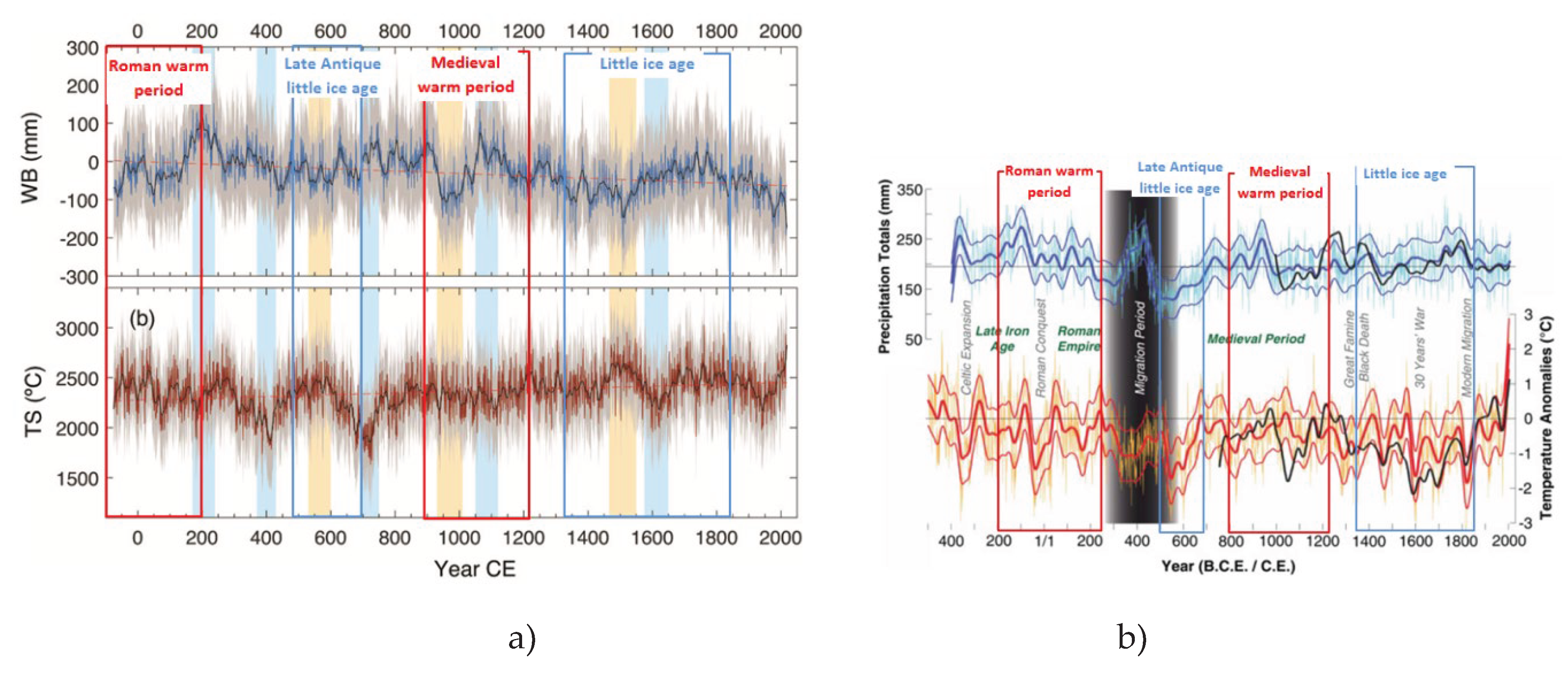

Changes in temperature and precipitation impact hydrology, agriculture, food production, and energy or wood supply—key elements for survival. In this region, key climate factors influencing crop yields include summer temperature anomalies, the cumulative daily temperature above 10°C during the growing season (TS), and the water balance (WB), defined as precipitation minus potential evapotranspiration [

14]. While TS and WB are negatively correlated, each shows substantial independent variation that affects crop yields, food availability, and society (

Figure 5a).

Warm periods are more stable, with a slightly smaller range of temperature changes, while colder periods are more unstable and have a larger range of oscillations. However, precipitation indicates significantly greater randomness/ stochasticity than temperature and is therefore more difficult to assess and predict (

Figure 5b). As average temperatures at Earth's surface rise, that will intensify Earth's water cycle, and more evaporation occurs, which, in turn, increases overall precipitation as well as frequent and intense storms. Therefore, a warming climate is expected to increase precipitation, while cooling reduces the same. However, locally, it may be very specific due to other factors (elevation, distance from the sea/water, vegetation) and, therefore, it may also contribute to drying in some land areas. Such changes affect the behavior and survival of biota, people and civilizations (

Figure 5). It turns out that low temperatures generally create unfavorable periods of "dark ages", while warmer ages bring prosperity and progress.

2.3.2. The Impact of Climate Change on Earth’s Abiotic Components

In the area of Dalmatia, hilly karst massifs, limestone and dolomite rocks predominate, which under the influence of the climate create slopes with creep processes and wash processes, but relatively slowly and little, creating bare limestone rocks in the higher parts of the hills. Simultaneously, through erosion and other geomorphological processes, broken and loose material is transported to lower terrain, where it accumulates and creates a plateau with diverse habitat and soil favorable for the development of biocenosis and agriculture. Fast and significant changes occur locally, mostly during periods of heavy precipitation which last several days or weeks, in the form of landslide, collapse of slopes and similar phenomena of movement of slope materials under the influence of water. It is a local threat that arises swiftly and violently with catastrophic and immediate results.

Climate simultaneously changes the hydrological and hydraulic characteristics of river systems, especially high temperatures and droughts, as well as heavy rains and floods. For people, both extremes are an existential threat. Agricultural droughts pose a threat to agriculture, while hydrological droughts pose a direct threat to humans. Drought is a process that occurs slowly and the duration is difficult to predict. In karst terrain, floods most often occur in karst fields, which regularly flood in winter. Floods are generated quickly and are difficult to avoid, so living outside the threatened area is a reliable solution.

The physiochemical processes in the karst water system (temperature and oxygen regulation, and nutrient cycling) that refers to the fundamental interactions and transformations that take place at the interface between physical and chemical properties of substances is specific and relatively stable. The contact time between water and the physical environment in a karst is generally short, because a karst is an extremely fluid system and it is longest in the deep parts of the aquifer (matrix). The water quality is therefore good, the temperature is stable, and the water is drinkable if it is not polluted. That is why waters in Dalmatia have been considered favorable for human consumption. Unfortunately, karst water systems are open and hence, vulnerable to pollution and are characterized by sudden and large changes in turbidity which last for a short time during periods of high flow [

17].

2.3.3. The Impact of Climate Change on Earth’s Biotic Components

Climate change is the driving shift behind species distribution, abundance, and reorganization of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and food hierarchy system, as well as food production. Animals and plants migrate to a more suitable climate to change their existing ecosystem, both, in terms of area of departure and destination. The risk to areas increase, leading to their decline or extinction, depending on the level and speed of change and adaptation capacity (autonomous adaptive capacity). This also applies to domestic animals, so climate change has caused the migration of nomadic peoples from endangered pastures to less endangered areas, which leads to conflicts and wars, that is, the struggle for survival since humans also migrate to more suitable climate (planned adaptive capacity).

The indigenous biota in the karst region of Dalmatia (sclerophyll forests and maquis or macchies) is resistant to climate variability since the Mediterranean climate has such characteristics that the biota has adapted and achieved natural resistance to climate variability. However, this does not apply to cereals and other cultivated and imported less resistant plant species. Climate change cycles are unpredictable, and unfavorable conditions, especially perennial ones, have a devastating effect on civilizations. There is an increase in the mortality rate of the population, which reduces the number of people needed for defense (army) and work, thus weakening the society as a whole.

2.3.4. Volcanoes, Cause Climate Change and Impacts

Throughout history, the greatest sudden threats to biota, crop production and human’s health and existence have been large volcanic eruptions [

18]. Volcanic eruptions modify environments physically and chemically with serious consequences for the biota, locally and globally. In general, volcanic activity releases ash and/or gas into the atmosphere that Earth’s temperature either gets too hot or cold for the biota. If the ash particles are really small (<2 microns) then they block out incoming sunlight and Earth cools and reduce sunlight and photosynthesis. If they are bigger than 2 microns (but still pretty small) then they let sunlight in but don’t let heat radiation from the surface out, and Earth undergoes warming. However, the ash and dust ejected during an eruption can block sunlight, reducing the amount of photosynthesis that can occur. This can lead to a temporary decrease in the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by plants. Global effects generate only large explosive eruptions that put the ash into stratosphere so it will not get rained out very quickly and will be around long enough to have a climatic effect [

19]. Ultimately, volcanoes, especially several of them in succession over several years, change the climate and have profound effects on geological processes, hydrological behavior, terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, depending on the strength and distance from the site of the explosion, and most of all on the availability of food for domestic animals and humans.

2.3.5. Climate Change and Oceanography

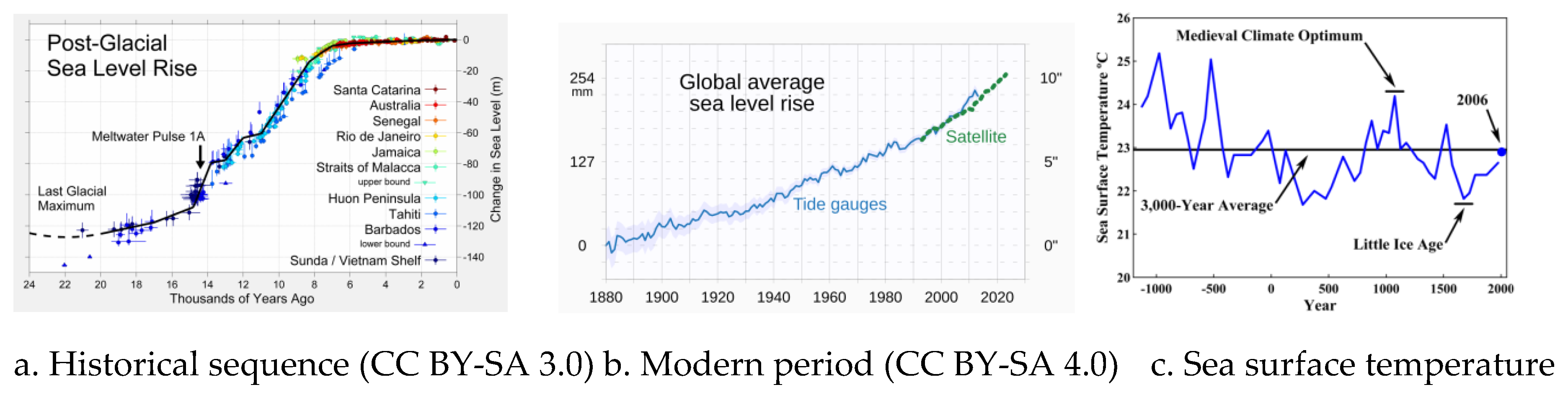

Another important natural factor of change in Dalmatia is the rise in mean sea level (MSL) and change in sea surface temperature (

Figure 6). The main cause of the MSL rise is warming and the resultant melting of glaciers, the same as in the case of climate. It is a natural process that changes the seashore and hydromorphological features of river systems [

20]. The MSL rise affects coastal cities and the coastal infrastructure. These are very slow transformation processes, unlike climate. MSL rise influence the geopotential energy of the river system, the water and sediment regime, or the entropy of the river system. In the last 20,000 years, MSL has been rising steadily, by more than 120 m,

Figure 6a.

In the last 4,000 years, the rise was minute and had a slow but little impact on nature and humans, because people and biota had enough time to adapt to the changes. However, from 1880 to 2000, the growth accelerated to a rate of about 1.8 mm per year (

Figure 6b) [

21]. Due to the slow and small growth in the last 2000 years, about 1.5 m, and as such imperceptible in the short life span of population (about 30 years), this phenomenon did not have a significant impact on the civilizations in Dalmatia, which cannot be said for the current trend of changes.

Similar to changes in air temperature, sea surface temperatures are also changing, thereby causing changes in the volume of sea water and sea level (

Figure 6c). Rising temperature modify sea food chain and so diversity and number of spices and sea food productivity and local climate. Sea temperature on the eastern Adriatic coast is less sensitive to changes in air temperature owing to ocean stabilization mechanism, strong winds and the local vertical mixing of water caused by them, and a substantial inflow of karst surface and groundwater, including under sea springs that has a stable water temperature of around 15 ℃. This means that in warm climate periods, these processes cooled the sea surface (freshwater rises to the surface of the sea), and in cold ones, they heated it. In addition, along the eastern coast of the Adriatic, sea currents bring sea from the warm Mediterranean basin and thus contribute to mitigating local temperature variability. Therefore, we can assume that the coastal sea of Dalmatia is less sensitive to climate change.

From what has been presented, it follows that climate change affects the availability and quality of potable water, food, air, and the places of shelter, i.e. cities, and thus human nature, health, and well-being. This leads to dissatisfaction and unrest (growth of social entropy), which causes significant socio-economic and political problems, leading to changes in culture and relations between people. Survival depended on the intensity of changes, the culture of water and the development of water civilization, and the advancement of technologies. Global climate change has typically occurred very slowly, over hundreds of years or more, and suddenly, in rare cases, due to major volcanic activity, major floods, and long-term droughts.

3. Evolution of Climate Change, Water Civilization and Livelihood Sustainability

3.1. Period from 750 BCE to 200 BCE

In the period from 750 BCE to 200 BCE, the cool and wet period of founded Rome (753 BCE) prevailed. It was a period after the Greek Dark Ages (≈ 1150 BCE to 800 BCE) that characterized decline, famine, and a reduction in population. MSL was about 2.0 m lower than today and the rise was significantly slower than in the previous period (

Figure 6a). The hydrology, geomorphology, ecosystems and biology, i.e. biogeomorphic system was consistent with a slightly cooler Mediterranean climate than today, and a karst landscape, as presented in

Section 2.

Dalmatia was inhabited by the Delmati and other Illyrian tribes (

Figure 1). At the beginning of the 4th century BCE, the first Greek colonies and cities were established, the island of Vis and Hvar in 385 BCE, and later in the central area between the Zrmanja and Neretva rivers, where Greeks founded the Issaean state. This marked the beginning of the period of Greek culture and civilization in Dalmatia, which was a great advancement over the existing tribal civilization. Greek cities were well-organized urban areas built according to ancient rules: proper arrangement of streets, public, and private facilities and infrastructure [

23]. All cities were located along the coast with ports, as all Greek transport relied on sea routes. The Greeks in Dalmatia inherited a water culture and water civilization modeled after their homeland. Public wells were built in apartment blocks to tap groundwater that float on seawater. Along with the wells, they used cisterns for rainwater. Hydraulically appropriate places like springs (Issa, Pharos) or rivers (Salona) were captured. In the Dalmatian Greek cities, an aqueduct and piped water supply network with fountains were not built as in larger Greek cities. Plumbing systems were put into place to safeguard against health and sanitation problems. Public and private toilets were built with drainage pipes consisted of terra cotta as well as limestone and could carry sewage water to the sea. Pipes have been used to carry rainwater down from the roofs of buildings to cisterns or street.

Water, food, and energy needs were low due to the small population and limited economy. Throughout this period, climate and the local natural environment were not limiting factors for society development. Supply and use balanced technologies, like food magazines and water reservoirs, were aligned with the natural seasonality of inflow-stock-supply (ISS) processes that support livelihood sustainability. In the context of climate change, none significant water-induced disasters are not reported.

After the Greeks in the 3rd century BCE, the area of Dalmatia was reconquered by the Illyrians, who were defeated by the Romans around 220 BCE, and took control of the Greek colonies and cities [

4].

3.2. Period between 200 BCE and 440 CE

3.2.1. Climate and Environment Evolution

The period between 200 BCE and 440 CE is the “Roman warm period”, a period favorable for living and development that lasted until 250 CE [

24]. Exceptional climate stability from 100 BCE to 200 CE characterized the centuries of the rise of the Roman Empire. It was warmer than later centuries. Level of solar activity was particularly stable and low level of volcanic activity also prevailed. Mean July temperatures were at least 1°C above mid-twentieth-century temperatures [

24].

MSL was about 1.5 m lower than today and the rise slowed even more compared to the previous period. Climate and hydro-morphological processes shaped the karst landscape and biophysical environment according to an established natural pattern, with minor oscillations, as presented in

Section 2. Gradually climate shifted away from the stability of the first centuries toward a broadly cooling, drier climate in the turbulent third centuries. Three major volcanic eruptions from c. 235 to 285 caused short-term climatic instability, with cooling and reduced solar energy, which triggered famine, political, military and, monetary crises that peaked from 250–290 CE. Reduction of solar radiation and long-wave heat radiation from nearby surface contribute to the cooler climate regime that modify condition of existences and reduce food availability and increase water-induced geo-hazards (flood and drought). In the eastern and southern Roman provinces, including province of Dalmatia, climate changes were not significant [

24].

Shortly before this period, 165–189 CE, the Antonine Plague occurred, leading to catastrophic results for the Roman populace [

25]. From 249–270 CE the new Plague of Cyprian occurred. The high mortality of the population caused by diseases and food shortages led to a lack of manpower, which weakened the economy (silver and food production) and recruitment of soldiers drastically weakened the Roman Empire. On the other hand, the problems that occurred in Dalmatia were more of a local nature, such as landslides and collapses of hillsides, soil erosion and floods, which were caused by heavy rainfall. The most significant regional problems were summer droughts. The socio-political problems and instability in Rome spread throughout the Empire and affected the civilization in Dalmatia.

3.2.2. Sociopolitical Evolution

In 36 BCE the Romans founded the province of Illyricum and after the defeat of the Delmati in 29 BCE the province of Delmati with its capital at Salona. The Roman province of Dalmatia shared the socio-political and economic development of the Roman Empire from then on.

After an unstable third century, a relatively stable fourth century occurred that experienced warming during its second half [

24]. Climatic instability continued into the 5th century, causing increasing migrations of Germanic peoples into the Empire. After years of persecution and bans, Christianity became the official religion in Empire (380 CE). However, it did not strengthen the Empire and did not contribute to resolving the crisis but rather worsened it, which together with climatic variability caused instability and division in the Empire that led to the final division and collapse of the Western Empire (476 CE) [

26]. During that critical period, Julius Nepos, who was considered by some to be the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire (474–475 CE) and supported in power by Byzantium, ruled in Salona, the capital of Dalmatia. In 480 CE, he was murdered in Diocletian’s palace in present-day Split, making Dalmatia the residence of the last Roman Emperor, which clearly shows that the socio-political situation and water-induced disasters in Dalmatia was less pronounced than in the rest of the Empire in context of climate change.

3.2.3. Sociocultural Evolution, Water Culture, and Water Civilization

The Roman period in Dalmatia was a period of the greatest advancement of culture and civilization, as well as water culture and water civilization. Roman government system ensured a stable organization of society and care for the supply of resources such as water, food and energy, and the development of non-material and material civilization. This refers to a highly developed urban and residential culture, the construction of cities and infrastructure, the education of specialized human capital, a well-organized army, the development of a complex social structure and religious system, written language, record keeping, and technology.

In the 2nd century, about one third of the population lived in cities [

26]. Water civilization therefore played an important role in the lives of the Romans, from providing necessary drinking water, supplying bath complexes, to the flow of water in large public fountains. Water civilization encompasses both material elements (infrastructure) and intangible ones (regulations, institutions, education, and human capital). Water had to be constantly present in cities and people's homes to satisfy natural needs and achieve security of life, because for the Romans, water was food, health and medicine, and ensured a whole range of other personal needs, primarily maintaining personal and urban hygiene, health, safety, and the atmosphere of nature that the flow of water in urban areas creates [27-30].

Every public building and housing block in the city was equipped with a public fountain. Such an urban water planning concept was supposed to demonstrate the "equality" of citizens in the use of public facilities. This is an important social measure that has supported health security and livelihood sustainability. To meet demand of society the Romans adopted various technologies from the Greeks and Etruscans, continually refining them through practical engineering [

31]. They applied variety of dissipative structures in order to support sustainability.

Technological processes are based on natural energy. Gravity and low-pressure technology were mostly used for water transport, using channels and pipes made of lead, stone, and terra cotta [

32]. Siphons and high-pressure pipe systems were built where deemed necessary. In a flow-through water supply system, stocks of water were not required; therefore, climate variability did not affect the system capacity and water quality. In the case of rainwater use, reservoirs were necessary. The same applies to intermittent watercourses.

Roman water culture was passed down through generations and was present throughout the Roman Empire, including in Dalmatia. It did not have one rigid form, but took shape in different scopes and forms, based on local climatic and social norms and values in a certain area. However, it always shaped the sense of belonging and personal identity of Roman civilization and did not depend exclusively on material status, because water was a common good that was used in accordance with the Water Act and Roman law that respected social, economic and environmental constraints. Permanent (natural) water was the public property and the use of water at public fountains and in public baths was free and private water was paid for [

33]. It is an important non-material measure of water civilization that boosted the economy and sustainability of society. In addition, lawyers developed the concept of joint ownership, i.e. "common good" ("res communes omnium") in which resources, e.g. air, water in rivers, lakes and seas and the sea coast, were not only open to everyone, but in a way, they were owned by everyone. This regulation significantly facilitates the management of water-induced geo-disasters.

All of the above applies in Dalmatia. Numerous UWS with long aqueducts and more complex hydro technical structures were built [

34]. All settlements had a system for collecting wastewater and stormwater, that is, a combined sewage system [34, 35].

In the sparsely populated rugged and surface water-poor karst interior, puddles were formed to collect water. Today they are called "Roman wells" because the water is used from a dug and arranged, stone-walled and built well, rather than a puddle [

36]. Other groundwater exploitation solutions were also used, such as dug masonry wells. The use of rainwater was the most widespread form of individual water supply. Where acceptable, intermittent surface waters and water springs were tapped using the storages. Roman engineers had a pragmatic solution for all locations where people resided. Therefore, it can be assumed that climate change has not significantly affected the supply of potable water, which cannot be said for irrigation and food production.

The "Roman warm period" is a period in Dalmatia in which water management developed intensively and ensured the survival of people and a high standard of living in the karst hydrological environment. That is why the Roman civilization in Dalmatia left numerous water structures and systems adapted to the Mediterranean climate, karst environment and water resources.

3.2.4. The Evolution of Sustainability

The Roman warm period was favorable for nature and humans for a long time, so the Empire grew stronger and expanded. During that period, Roman civilization exhibited an acute awareness of environmental stewardship and resource management. However, climatic variability that occurred during the period of large volcanic eruptions in the 3rd century caused an unfavorable state in the natural environment, which led to an unstable situation in a society that was at the peak of its development. Thus, unpredictable negative external forces caused negative internal forces that created disorder in resources supply and destabilized the Roman civilization. Disorder caused by solar energy variation spread to the biotic and abiotic environment and eventually affected the socio-political system in the long run. This essentially caused dissipation of energy in cooler environment that affected sustainability of food and bio-energy dynamic of food chain, primary production and food for man, as well as animals. An "incoming solar radiation" created a one-way flow of energy in the environment and affected existing concepts of ISS of water and materials in nature and society.

Roman civilization was not ready for such sudden and unpredicted climate changes, which caused food shortages and other problems in the empire and surroundings. In addition to hunger, a major problem was diseases and epidemics that occurred and spread throughout the empire, causing high mortality rates and a reduction in labor force. The problems that arose outside the borders prompt the immigration of barbarians into the empire. Immigrants changed Roman culture and civilization, which further weakened the empire. The Roman culture and technology had no answer to these. The duration of the climate crisis over a period of several years creates a longer-term disorder in the multilayer energy, water, food ISS systems and thus the growth of instability in society. There was lack of free energy for the rapid improvement of the production of food and economy, because everything was based on natural energy, which had its own natural law of behavior to keep far away from thermodynamic equilibrium.

In addition, the knowledge and technological capital needed to support the economy of the Empire and finances were increasingly absent in the new socio-cultural environment. Knowledge could not be effectively transferred to the incoming population, thereby slowing and weakening adaptation. Excluding access to knowledge and technology was especially costly—often prohibitively so. As a result, the Empire fragmented, moving away from the ancient vision of harmony between humans and nature, and with it, the decline of traditional water culture and civilization, ultimately reducing societal sustainability. The situation in Dalmatia deteriorated more slowly due to high natural autonomous capacity and low sensitivity, as well as low demand.

3.3. Period between 400 and 900 CE

3.3.1. Climate and Environment Evolution

The period between 440 and 900 CE (The Late Antique Little Ice Age), was known as the "Dark Age and cool period". This period was characterized by marked cooling and due to a supposed period of decline in culture and science. A significant cooling occurred in 540 CE. The period coincides with three large volcanic eruptions in 535/536 CE, 539/540 CE and 547 CE which changed the energy balance on Earth’s atmosphere [

24]. This had reduced solar radiation and cooled the environment, which impacted hydrological, natural and man-made systems; similar to what happened in the 3rd century. Temperature significantly fluctuated until about 630 CE, that in the second part of seventh century when climate began to be wormer and wet, from 650–750 CE, began period of gradual recovery and growth [

24].

In the period from 550–950 CE the cumulative daily sum of temperature above 10°C (TS) during growing season sharply decreased and then increasing. The water balances (WB) fluctuated a lot, but did not have very pronounced trends (

Figure 5). These data indicate that temperature conditions for yields of many important crops in the region were variable and generally unfavorable, and more favorable in the period from 650–750 CE.

The MSL was about 1.5 m lower than today and the sea level rise was slow, so the increasing accumulation of sediment in the deltas and the coastal zone resulted in the expansion of the land into the sea and the growth of alluvial terrain in the river valleys and coastal zone. A hydrology, geomorphology, ecosystems and biology process, i.e. bio-geomorphic system was consistent with the Mediterranean climate and karst environment for which the temperature was lower than in the previous period. The decrease in air temperature in Dalmatia was not as great as in continental Europe, due to ocean current that transports warm water from the Mediterranean Sea along the eastern Adriatic coast. The interchange of dry and extremely rainy periods created conditions for increased soil erosion and greater transport of bottom and suspended sediment into the accumulation zones of the river system. As a result, weather instability changed the karst landscape in Dalmatia, i.e. increased the barrenness of karst hills and expanded alluvial plateaus, which was beneficial because fertile soil expanded in the plateaus.

3.3.2. Sociopolitical Evolution

In Northern and Central Europe, a lack of food for people and domestic animals led to hunger and disease, causing great famine, conflicts and new migrations that further destabilized the Roman Empire (

Figure 4).

The cooling event of 536 CE has been identified as a major environmental moment in the history of the Roman Empire [

24]. The mortality rate of the population increased even more around 541 CE when Justinian's plague (pandemic) appeared and spread in waves through the former Empire. Cooler temperatures and changing hydroclimate affected the distribution and abundance of hosts and vectors that spread disease (e.g., plague). These impacts compounded over time, destabilizing the socio-political system, fragmenting power, and contributing to the decline of ancient culture.

Dalmatia was ruled by Byzantium which establishes the region "

The Theme of Dalmatia" [

4]. The socio-political system changed abruptly with the arrival of the Avars and Slavs, who conquered Dalmatia around 614 CE and destroyed Roman cities and infrastructure, which results in completely collapsed ancient culture and civilization. This has significantly reduced society's ability to adapt to climate change. The main driver of these migrations was drought in Central Asia, prompting people to seek new pastures [

24].

After the defeat of the Avars at Constantinople (626 CE), Emperor Heraclius (610 – 641 CE) invited the Slavic-Antic Croats from White or Greater Croatia (the area around Krakow in Poland) to liberate Dalmatia from the Avars and settle there, which they did around 630 CE [

4]. They took control of the entire mainland area of Dalmatia, except for the area around coastal cities which, together with the islands, remained under Byzantine rule. The cold climate ultimately led to Dalmatia being split into two administrative units with distinct cultural and civilizational traits: Ancient-Byzantine and Barbarian Croatia which has reduced the long-term ability of society to implement vulnerability management strategy.

3.3.3. Sociocultural Evolution, Water Culture and Water Civilization

Byzantium was a monarchy in which the emperor ruled in accordance with the law, the

Corpus Iuris Civilis (Collection of Civil Laws), which was also applied in the "

theme of Dalmatia" [

26]. Thus, water law was kept in practice and supported the development of non-material and material water civilizationthat that could respond to climate and water-induced threats.

The rest of the coastal area and hinterland of ancient Dalmatia, called "Prijadranska Croatia", were ruled by Croatian national rulers (620 – 1102 CE). Thus, in the area between the Zrmanja and Cetina rivers, the Croatian state developed, as did new cities with a Croatian population and culture. The type of ruling was early feudalism. The territory of the Croatian state was dominated by an agrarian civilization, a low culture of housing and urbanization, and illiteracy because the society lacked its own script and was without scientific and technological education. There was no organized system for managing society and the supply of water, food, and energy.

Water culture was low, as was water civilization, so the need for water was small and hygienic living conditions were inadequate, favoring the spread of disease. Water had no greater cultural importance for society, so water civilization did not shape a sense of collective identity and social organization as it did in Rome. People lived in small fortified towns on the hills; locations that could not be supplied by surface and groundwater by gravity, only by rainwater. Cities modeled after ancient urbanism was not built. Water-induced geo-disasters in the context of climate change (floods and droughts) were a constant threat that jeopardized livelihood security.

Water civilization heritage in Dalmatia after the Roman period is difficult to find, which clearly speaks of the cultural and civilizational decline that occurred in late Ancient Little Ice Age in the Dalmatian region.

3.3.4. The Evolution of Sustainability

In this cold period, solar energy transformation into potential energy of food was reduced and affected operation of life (condition of existence). The greatest impact came from reduced light intensity caused by volcanic eruptions. Unfavorable climatic conditions, crop failure and increase of climate change induced geo-disasters contributed to reduction of population and migrations. Both caused divisions and increased unrest in society. Additionally, there was continuous de-urbanization and a decline in civic culture and civilization. Roman water culture and the concept of the common good were practiced less and less („res communes omnium“). A new feudal structure of society was gradually implemented. Natural resources were not open to everyone, but only to the owners, a small number of people (lords and church). With this, the foundations of equality in society and the Roman culture of identity disappeared, thus creating dissatisfaction among the people. That was the dark age of water culture and water civilization in Europa and Dalmatia. The ISS system for water, food and energy supply, as well as adaptive and resilient measures to mitigate the impact was not organized at the state level. As a result, life in in cities was insecure and short.

Karst environment, biotic and abiotic, was adapting to new “condition of existence” (autonomous adaptation) and supported new energy transformation into potential energy of food, especially permanent crops (grapes, olives, nuts, citrus, figs, carobs), so that in the wider natural environment, there were generally enough subsistence resources. This was supported by the warm Mediterranean Sea and karst water resources. Bushes and scrubland—such as thyme, juniper, rosemary, and lavender—along with plants with waxy leaves and deep roots for moisture retention, offered the main grazing areas for domestic animals. The regional annual summer migration of domestic animals from the coastal area to the interior, and back in the fall, was planned adaptive measure that ensured food resources for people and livestock. This was a flexible practice that integrated positive climate impacts and minimized negative ones, and reduced the need for stocks of food, water and energy and support sustainability.

It follows that in this climatically cold period in Dalmatia, people and the newly created society in the territory of the Empire were caught by external natural and climate induced internal forces, which weakened social organization, identity, society and thus sustainability. External cool weather and internal fragmentation of society, a mixture of barbaric and ancient civilization, influenced culture, civilization in newly created communities and lack of water culture and water civilization did not create an adequate response to climate volatility.

The ISS system and planned adaptive measures was based on individual solutions, not on common ones at state level. There was a lack of strong and well-organized government and institutions. There was no culture and technology progress necessary to develop appropriate ISS concept and adaptive and resilient strategies to manage the newly emerging processes, since adequate institutional environment to support literacy, education and human capital development missing. Water was not at the foundation of society in Croatian Dalmatia, while the ancient significance of water in the Byzantine “theme of Dalmatia” gradually weakened. This eventually led to the further fragmentation of the society and a departure from the ancient vision of the coexistence of man and nature, and this ancient water culture and civilization increased accumulation of entropy and decreased sustainability.

4. Discussion

In Dalmatia, civilization as well as water civilization began with the barbarians (Illyrians) after the Greek Dark Age (800 BCE), and after 1000 years ended again with the barbarian Slavs in the post-Roman period (800 AD), a society of low values regarding the importance of water for society. During that period, it also experienced the greatest degree of development of culture and civilization in a Roman Warm Period (250 BCE to 400 AD), and a major setback in the Late Antique Ice Age. So, it could be concluded that the warm period for Dalmatia was a favorable period for the development of culture and civilization, and ice ages were unfavorable.

Long-term, common changes in temperature and precipitation have changed Earth's processes and civilizations over a long period of time, while short-term ones (volcanic eruptions) quickly and with serious consequences for biota, that affect civilizations. That happens mostly because of significant reduction in light intensity which reduces the rate of photosynthesis and hence production of oxygen and carbohydrates that plants use for energy and growth. Additional problems and disorder were created by diseases reinforced by food shortages, what rapidly reduced the population. Water was not a critical resource, but it was a lack of sustainability vision, strategy, and adaptation measures.

Karst areas display a complex response to climate change and exhibit different resistance to extreme weather. Karst landscape is characterized by thin soil, high infiltration capacity and low water holding capacity and the karst ecosystem exhibits higher sensitivity to climate change. However, autonomous adaptive capacity of biota is generally high and may reduce vulnerability to changes in precipitation and temperature; this depends significantly on the internal climate zones characteristics, distance from the sea and altitude, as well as the wider environment characteristics with which it exchanges energy.

The two climate areas of river systems in Dalmatia river basins (type C and D) were crucial for survival because natural processes and water resources complemented each other across climate borders and thus reduced tensions and growth of entropy in climatically unfavorable periods. Free energy and water spread from one area to another and thereby supported the energy and water balance that strengthened sustainability. Karst, as an open system, has fast water communication between river basin climate acres, which supported the stability of the ICC process, i.e. sustainability.

However, every process in nature as well as society increases entropy thus, establishing a distinction between the past and future. Therefore, the second Law establishing an arrow of time; the increases of entropy distinguish future from past. Although destruction of order always prevails in the system in or near thermodynamic equilibrium, the construction of order (new environment) may occur in a system far from equilibrium, but other primarily immaterial factors could have had an influence, such as scientific, cultural, spiritual, religious, developing adaptive and resilient strategies and measure and other characteristics of civilization.

Whether civilization will collapse or improve sustainability strongly depends on the database, knowledge base, available technology, and energy to support adaptation and sustainability of natural and socio-political system (vision, strategy and entropy/disorder dissipative structures). An advanced civilization that rationally analyzes and observes the natural processes and the resulting changes in nature and society will be able to generate knowledge, technologies and energy, and defend itself implementing appropriate dissipative measures. However, if supernatural interpretations of the resulting changes and solutions/answers prevail in the resulting disorder, then it is impossible to defend and preserve the existing civilization. Energy and water in such a society is not subject to the climate risk management process and dissipative structures cannot be implemented. This happened in the area of Dalmatia during the migration period.

The return to a rational understanding of Earth’s processes and the environment takes a long time (centuries), until the moment when a sufficiently strong resistance motivated by the catastrophic results of the existing ineffective civilization is not called into question. For a society powered only by natural energy a simple rule applies to a complex socio-political problem caused by climate; cool, dry and unstable climate equals higher famine and disorder in society, while warm, wet and stable climate favorable.

5. Conclusions

This study used an inductive approach, starting with the collection and organization of historical data to build a cognitive orientation, and concluding with a theory that supported the observation and results. The goal was to understand the past in order to better anticipate the future. Inductive learning was seen as an appropriate approach for assessing the interaction and evolution of the history of climate-water-civilization-sustainability interrelationships. This enables us to define the concept and develop the theory.

The laws of thermodynamics were applied to generalize the processes and states of the natural and anthropogenic systems and their interactions and interdependence. These principles support climate risk assessments and help develop sustainability indicators, including water culture, water civilization, and the ISS as a dissipative structure. The central measure of adaptation was the "stock" which can be quantified. The duration of the inflow-supply balancing period is critical for strengthening sustainability of dissipative structure and reducing entropy and it must be long enough to bridge expected period of climate variability. Vision and sustainability strategy must support the ISS system’s capability to capture water, energy, and materials from the environment, enabling society to survive and evolve across climate periods and into the future.

Given the interdependence of water, energy, food, and climate, it follows that water culture and civilization response, i.e., knowledge of human-water interactions, may possibly be a suitable cumulative indicator for the assessment of civilization sustainability in the context of climate change. This reflects a vision of coexistence between humanity and nature. Sustainability is a driving force of condition of existence that must accommodate both the metabolic system (maintaining normal functioning) and the information system (interconnected set of components of management, decision, and knowledge structures) within an appropriate conceptual framework (formal theories) adapted to expected climatic conditions. We hope that the results and developed methodology of the study will be suitable and useful in other regions facing both historical and contemporary climate challenges.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing. Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eloise M.Biggs et al., Sustainable development and the water–energy–food nexus: A perspective on livelihoods, Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 54, December 2015, Pages 389-397. [CrossRef]

- Tvedt, T.; Jakobsson, E. Introduction: Water History Is World History. 2006. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336233029_Introduction_Water_History_is_World_History (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Brooks, D.R.The Extended Synthesis: The Law of the Conditions of Existence, Evo Edu Outreach (2011) 4:254–261. [CrossRef]

- Novak, G. The past of Dalmatia I and II (in Croatian), Marjan tisak, Split, Hrvatska, 2004.

- Koppen’s Climate Classification, https://blogmedia.testbook.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/koppen-1360be25.pdf. (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Margeta, J. Water abstraction management under climate change: Jadro spring Croatia. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 16, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanovic, P. Water Resources Engineering in Karst; CRC Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burney,S.; Aqil, M.; Saleem, H. Inductive and Deductive Research Approach. 2008, 10. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian K. Biological catalysis of the hydrological cycle: life’s thermodynamic function, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 8, 1093–1123, 2011 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/8/1093/2011/. [CrossRef]

- Poudel, R.; McGowan, J.; Georgiev, G.Y.; Haven, Gunes, E.; Zhang, H.. Thermodynamics 2.0: Bridging the natural and social sciences, Published:19 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Holland, D. Bias and Concealment in the IPCC Process: The “Hockey-Stick” Affair and its Implications. Energy & Environment, 18(7), 2007, 951-983. (Original work published 2007). [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Climate change. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_change. (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Loehle, C. A 2000 Year Global Temperature Reconstruction Based on Non-Tree Ring Proxies. Energy & Environment, 18, 2007, 1049-1058. ona knjiga kritika Lohle 2007. [CrossRef]

- Max C. A. Torbenson et al, Central European Agroclimate over the Past 2000 Years, Journal of Climate, Volume 36, July 2023, pp. 4429-4441, American Meteorological Society. [CrossRef]

- Trnka, M.; Kysely,J.; Možny, M.; Dubrovsky, M. Changes in central-European soil-moisture availability and circulation Max C. A. Torbenson et al, Central European Agroclimate over the Past 2000 Years, Journal of Climate, Volume 36, July 2023., pp. 4429-4441, American Meteorological Society. [CrossRef]

- Tadeusz Niedźwiedź et al, The Historical Time Frame (Past 1000 Years), in the The BACC II Author Team, Second Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin, Regional Climate Studies, 2015, Springer Open, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Margeta J.; Fistanić I. Water quality modeling of Jadro spring, Water Sci. Technology, 2004; 50(11):59-66.

- Volcanoes, https://volcano.oregonstate.edu/faq/how-do-volcanoes-affect-plants-and-animals, (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Blong, R.J.. Volcanic hazards: A source book on the effects of eruptions: Academic Press, Orlando, Florida, 1984, 424 p.

- Margeta, J. Historic socio-hydromorphology co-evolution in the Delta of Neretva. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Sea level rise, https://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea level rise (assessed 10.05.2024).

- Climate Change and the Fall of the Late Roman Empire, Compiled by Lewis Loflin, https://www.sullivan-county.com/id6/hungry.htm.

- Štambuk, I. Urban planning and architecture of the Greek city of Phaoros (in Croatian, “Urbanizam i arhitektura grčkog grada Phaorosa”), Prilozi povijesti otoka Hvara, Vol. XV No. 1, 2022.

- McCormick, M.; Buntgen, U.; Cane, M.A.; Cook, E.R.; Harper, K.; Huybers, P.; Litt, T.; Manning, S.W.; Mayewski, P.A.; Alexander, F.M.; et al. More Climate Change during and after the Roman Empire: Reconstructing the Past from Scientific and Historical Evidence. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 2012, 169–220. [Cross Ref].

- Wikipedia, Antonine Plague. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonine_Plague, (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Cravetto, E. History, Book 5. The Late Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages, 2007, (Croatian edition, Jutarnji list, Povijest, Knjiga 5. Kasno Rimsko Carstvo i Rani Srednji vijek, 2007.

- Pliny the Elder. The Natural History of Pliny; Bostock, J., Riley, H., Bohn, H.G., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Vitruvius; Warren, H.L. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture (1914); Paperback—September 10; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2010.

- Frontinus, S.J.; Herschel, C. The Two Books on the Water Supply of the City of Rome of Sextus Julius Frontinus: Water Commissioner of the City of Rome A.D. 97: A Photographic . . . in Latin; Also a Translation into English by Clements Herchel, Boston, Massachusetts; Nabu Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2010.

- Margeta, J. Lead was an acceptable material for Roman water supply, Water History, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wikander, Ö. Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Volume 2, Brill, Leiden-Boston-Koln, 2000, ISSN l 385-920X, ISBN 90 04 11123 9.

- Hodge, T. Roman water aqueducts & water supply. Bristol Classical Press, 2002, London.

- Bannon, C.J. Fresh Water in Roman Law: Rights and Policy Article in The Journal of Roman Studies · August 2017.

- Marasović, K.; Margeta, J.; Perojević, S. Ancient water supply systems in Delmacija, in Croatian, Sabor hrvatskih graditelja 2016, 857-878.

- Margeta, J.; Marasović K.; Perojević, S.; Katić, M.; Bojanić, D. Ancient water systems of the city of Salona and Diocletian's Palace and their impact on the sustainability of urban environments, in Croatian, Hrvatske zaklade za znanost IP-11-2013, Zagreb.

- Wells Rajčice, https://croatiatravelreviews.com/bunari-rajcica-rimski-bunari/, (accessed on 2 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).