Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Objective

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. CYP2C9

4.2. CYP2C19

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vidovic S, Skrbic R, Stojiljkovic MP, et al. Prevalence of five pharmacologically most important CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 allelic variants in the population from the Republic of Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 2021;72(3):129-134. [CrossRef]

- Sangkuhl K, Claudio-Campos K, Cavallari LH, et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C9. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;110(3):662-676. [CrossRef]

- Miners JO, Birkett DJ. Cytochrome P4502C9: an enzyme of major importance in human drug metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998;45(6):525-38. [CrossRef]

- Botton MR, Whirl-Carrillo M, Del Tredici AL, et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C19. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;109(2):352-366. [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Oleszkiewicz B, Wiela-Hojenska A. CYP2C19 polymorphism in relation to the pharmacotherapy optimization of commonly used drugs. Pharmazie 2018;73(11):619-624. [CrossRef]

- PHARMGKB. CYP2C9 Drug Label Annotations. (https://www.pharmgkb.org/gene/PA126/labelAnnotation).

- PHARMGKB. CYP2C19 Drug Label Annotations. (https://www.pharmgkb.org/gene/PA124/labelAnnotation).

- UNFPA. Asian and the Pacific. Population trends. (https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/topics/population-trends-9).

- Bottern J, Stage TB, Dunvald AD. Sex, racial, and ethnic diversity in clinical trials. Clin Transl Sci 2023;16(6):937-945. [CrossRef]

- Clark LT, Watkins L, Pina IL, et al. Corrigendum to ;;Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers''. [Current Problems in Cardiology, Volume 44, Issue 5 (2019) 148-172]. Curr Probl Cardiol 2021;46(3):100647. [CrossRef]

- Alrajeh K, AlAzzeh O, Roman Y. The frequency of major ABCG2, SLCO1B1 and CYP2C9 variants in Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women subgroups: implications for personalized statins dosing. Pharmacogenomics 2023;24(7):381-398. [CrossRef]

- Alrajeh KY, Roman YM. The frequency of major CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms in women of Asian, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander subgroups. Per Med 2022;19(4):327-339. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Lauschke VM. Worldwide Distribution of Cytochrome P450 Alleles: A Meta-analysis of Population-scale Sequencing Projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;102(4):688-700. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JA, Caudle KE, Gong L, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Pharmacogenetics-Guided Warfarin Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;102(3):397-404. [CrossRef]

- Lima JJ, Thomas CD, Barbarino J, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C19 and Proton Pump Inhibitor Dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;109(6):1417-1423. [CrossRef]

- Lee CR, Luzum JA, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022;112(5):959-967. [CrossRef]

- Chenchula S, Atal S, Uppugunduri CRS. A review of real-world evidence on preemptive pharmacogenomic testing for preventing adverse drug reactions: a reality for future health care. Pharmacogenomics J 2024;24(2):9. [CrossRef]

- Swen JJ, van der Wouden CH, Manson LE, et al. A 12-gene pharmacogenetic panel to prevent adverse drug reactions: an open-label, multicentre, controlled, cluster-randomised crossover implementation study. Lancet 2023;401(10374):347-356. [CrossRef]

- Celinscak Z, Zajc Petranovic M, Setinc M, et al. Pharmacogenetic distinction of the Croatian population from the European average. Croat Med J 2022;63(2):117-125. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen RS, Brasch-Andersen C, Sim SC, et al. Linkage disequilibrium between the CYP2C19*17 allele and wildtype CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 alleles: identification of CYP2C haplotypes in healthy Nordic populations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66(12):1199-205. [CrossRef]

- Buzoianu AD, Trifa AP, Muresanu DF, Crisan S. Analysis of CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3 and VKORC1 -1639 G>A polymorphisms in a population from South-Eastern Europe. J Cell Mol Med 2012;16(12):2919-24. [CrossRef]

- Skadric I, Stojkovic O. Defining screening panel of functional variants of CYP1A1, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 genes in Serbian population. Int J Legal Med 2020;134(2):433-439. [CrossRef]

- Dorado P, Berecz R, Norberto MJ, Yasar U, Dahl ML, A LL. CYP2C9 genotypes and diclofenac metabolism in Spanish healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003;59(3):221-5. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Diz P, Estany-Gestal A, Aguirre C, et al. Prevalence of CYP2C9 polymorphisms in the south of Europe. Pharmacogenomics J 2009;9(5):306-10. [CrossRef]

- Dorji PW, Tshering G, Na-Bangchang K. CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A5 polymorphisms in South-East and East Asian populations: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2019;44(4):508-524. [CrossRef]

- Ustare LAT, Reyes KG, Lasac MAG, Brodit SE, Jr., Baclig MO. Single nucleotide polymorphisms on CYP2C9 gene among Filipinos and its association with post-operative pain relief via COX-2 inhibitors. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2020;11(2):31-38. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33240461).

- Sun B, Wen YF, Culhane-Pera KA, et al. Differences in Predicted Warfarin Dosing Requirements Between Hmong and East Asians Using Genotype-Based Dosing Algorithms. Pharmacotherapy 2021;41(3):265-276. [CrossRef]

- Wen YF, Culhane-Pera KA, Thyagarajan B, et al. Potential Clinical Relevance of Differences in Allele Frequencies Found within Very Important Pharmacogenes between Hmong and East Asian Populations. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40(2):142-152. [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad T, Ghosh K, Shetty S. VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genotype distribution in Asian countries. Thromb Res 2014;134(3):537-44. [CrossRef]

- Jose R, Chandrasekaran A, Sam SS, et al. CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms: frequencies in the south Indian population. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2005;19(1):101-5. [CrossRef]

- Xie HG, Prasad HC, Kim RB, Stein CM. CYP2C9 allelic variants: ethnic distribution and functional significance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002;54(10):1257-70. [CrossRef]

- Soga Y, Nishimura F, Ohtsuka Y, et al. CYP2C polymorphisms, phenytoin metabolism and gingival overgrowth in epileptic subjects. Life Sci 2004;74(7):827-34. [CrossRef]

- Vu NP, Nguyen HTT, Tran NTB, et al. CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism in the Vietnamese population. Ann Hum Biol 2019;46(6):491-497. [CrossRef]

- Geisler T, Schaeffeler E, Dippon J, et al. CYP2C19 and nongenetic factors predict poor responsiveness to clopidogrel loading dose after coronary stent implantation. Pharmacogenomics 2008;9(9):1251-9. [CrossRef]

- Ragia G, Arvanitidis KI, Tavridou A, Manolopoulos VG. Need for reassessment of reported CYP2C19 allele frequencies in various populations in view of CYP2C19*17 discovery: the case of Greece. Pharmacogenomics 2009;10(1):43-9. [CrossRef]

- Scordo MG, Caputi AP, D'Arrigo C, Fava G, Spina E. Allele and genotype frequencies of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 in an Italian population. Pharmacol Res 2004;50(2):195-200. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Xie Y, Zhang D, et al. CYP2C19 gene polymorphism in Ningxia. Pharmacol Rep 2023;75(3):705-714. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Qin S, Xie J, et al. Genetic polymorphism analysis of CYP2C19 in Chinese Han populations from different geographic areas of mainland China. Pharmacogenomics 2008;9(6):691-702. [CrossRef]

- Zuo LJ, Guo T, Xia DY, Jia LH. Allele and genotype frequencies of CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 in Han, Uighur, Hui, and Mongolian Chinese populations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2012;16(2):102-8. [CrossRef]

- Yamada S, Onda M, Kato S, et al. Genetic differences in CYP2C19 single nucleotide polymorphisms among four Asian populations. J Gastroenterol 2001;36(10):669-72. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein JA, Ishizaki T, Chiba K, et al. Frequencies of the defective CYP2C19 alleles responsible for the mephenytoin poor metabolizer phenotype in various Oriental, Caucasian, Saudi Arabian and American black populations. Pharmacogenetics 1997;7(1):59-64. [CrossRef]

- Gulati S, Yadav A, Kumar N, et al. Frequency distribution of high risk alleles of CYP2C19, CYP2E1, CYP3A4 genes in Haryana population. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2014;37(3):1186-93. [CrossRef]

- Anichavezhi D, Chakradhara Rao US, Shewade DG, Krishnamoorthy R, Adithan C. Distribution of CYP2C19*17 allele and genotypes in an Indian population. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012;37(3):313-8. [CrossRef]

- Ghodke Y, Joshi K, Arya Y, et al. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19 in Maharashtrian population. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22(12):907-15. [CrossRef]

- Shalia KK, Shah VK, Pawar P, Divekar SS, Payannavar S. Polymorphisms of MDR1, CYP2C19 and P2Y12 genes in Indian population: effects on clopidogrel response. Indian Heart J 2013;65(2):158-67. [CrossRef]

- Kubota T, Chiba K, Ishizaki T. Genotyping of S-mephenytoin 4'-hydroxylation in an extended Japanese population. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996;60(6):661-6. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima-Uesaka H, Saito Y, Maekawa K, et al. Genetic variations and haplotypes of CYP2C19 in a Japanese population. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2005;20(4):300-7. [CrossRef]

- Lee SS, Lee SJ, Gwak J, et al. Comparisons of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms between Korean and Vietnamese populations. Ther Drug Monit 2007;29(4):455-9. [CrossRef]

- Kim KA, Song WK, Kim KR, Park JY. Assessment of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms in a Korean population using a simultaneous multiplex pyrosequencing method to simultaneously detect the CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, and CYP2C19*17 alleles. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010;35(6):697-703. [CrossRef]

- Roh HK, Dahl ML, Tybring G, Yamada H, Cha YN, Bertilsson L. CYP2C19 genotype and phenotype determined by omeprazole in a Korean population. Pharmacogenetics 1996;6(6):547-51. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Yang X, Chen H, et al. A pangenome reference of 36 Chinese populations. Nature 2023;619(7968):112-121. [CrossRef]

- Kiffmeyer WR, Langer E, Davies SM, Envall J, Robison LL, Ross JA. Genetic polymorphisms in the Hmong population: implications for cancer etiology and survival. Cancer 2004;100(2):411-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou SF, Liu JP, Chowbay B. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab Rev 2009;41(2):89-295. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta D, Choudhury A, Basu A, Ramsay M. Population Stratification and Underrepresentation of Indian Subcontinent Genetic Diversity in the 1000 Genomes Project Dataset. Genome Biol Evol 2016;8(11):3460-3470. [CrossRef]

- Theken KN, Lee CR, Gong L, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020;108(2):191-200. [CrossRef]

- Roman Y. Bridging the United States population diversity gaps in clinical research: roadmap to precision health and reducing health disparities. Per Med 2025:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Vo V, Lopez G, Malay S, Roman YM. Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Asian Americans: Perspectives on the Role of Acculturation in Cardiovascular Diseases Health Disparities. J Immigr Minor Health 2024;26(2):409-420. [CrossRef]

- Roman, YM. Race and precision medicine: is it time for an upgrade? Pharmacogenomics J 2019;19(1):1-4. [CrossRef]

| Medication Name | Genes | PGX Level |

|---|---|---|

| Siponimod | CYP2C9 | Testing Required |

| Celecoxib | CYP2C9 | Actionable PGx |

| Dronabinol | CYP2C9 | Actionable PGx |

| Fosphenytoin | CYP2C9, HLA-B | Actionable PGx, Informative PGx |

| Glimepiride | CYP2C9 | Actionable PGx |

| Glyburide | CYP2C9 | Actionable PGx |

| Losartan | CYP2C9, CYP3A4 | Actionable PGx |

| Phenytoin | CYP2C9, HLA-B | Actionable PGx |

| Warfarin | CYP2C9, VKORC1 | Actionable PGx |

| Meloxicam | CYP2C9 | Informative PGx, Criteria Not Met |

| Prasugrel | CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A5 | Informative PGx, No Clinical PGx |

| Medication Name | Genes | PGX Level |

|---|---|---|

| Mavacamten | CYP2C19 | Testing Required, Informative PGx |

| Amitriptyline | CYP2C19, CYP2D6 | Actionable PGx |

| Carisoprodol | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx |

| Citalopram | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx |

| Clobazam | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx |

| Clopidogrel | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx, Informative PGx |

| Escitalopram | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx, Informative PGx |

| Lansoprazole | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx |

| Pantoprazole | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx, Informative PGx |

| Voriconazole | CYP2C19 | Actionable PGx, Informative PGx |

| Diazepam | CYP2C19, CYP3A4 | Informative PGx |

| Omeprazole | CYP2C19 | Informative PGx, No Clinical PGx |

| Phenytoin | CYP2C19 | Informative PGx |

| Prasugrel | CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A5 | Informative PGx, No Clinical PGx |

| Ticagrelor | CYP2C19 | Informative PGx, No Clinical PGx |

| Esomeprazole | CYP2C19 | No Clinical PGx |

| Drospirenone, ethinyl estradiol | CYP2C19 | No Clinical PGx |

| Lacosamide | CYP2C19 | No Clinical PGx |

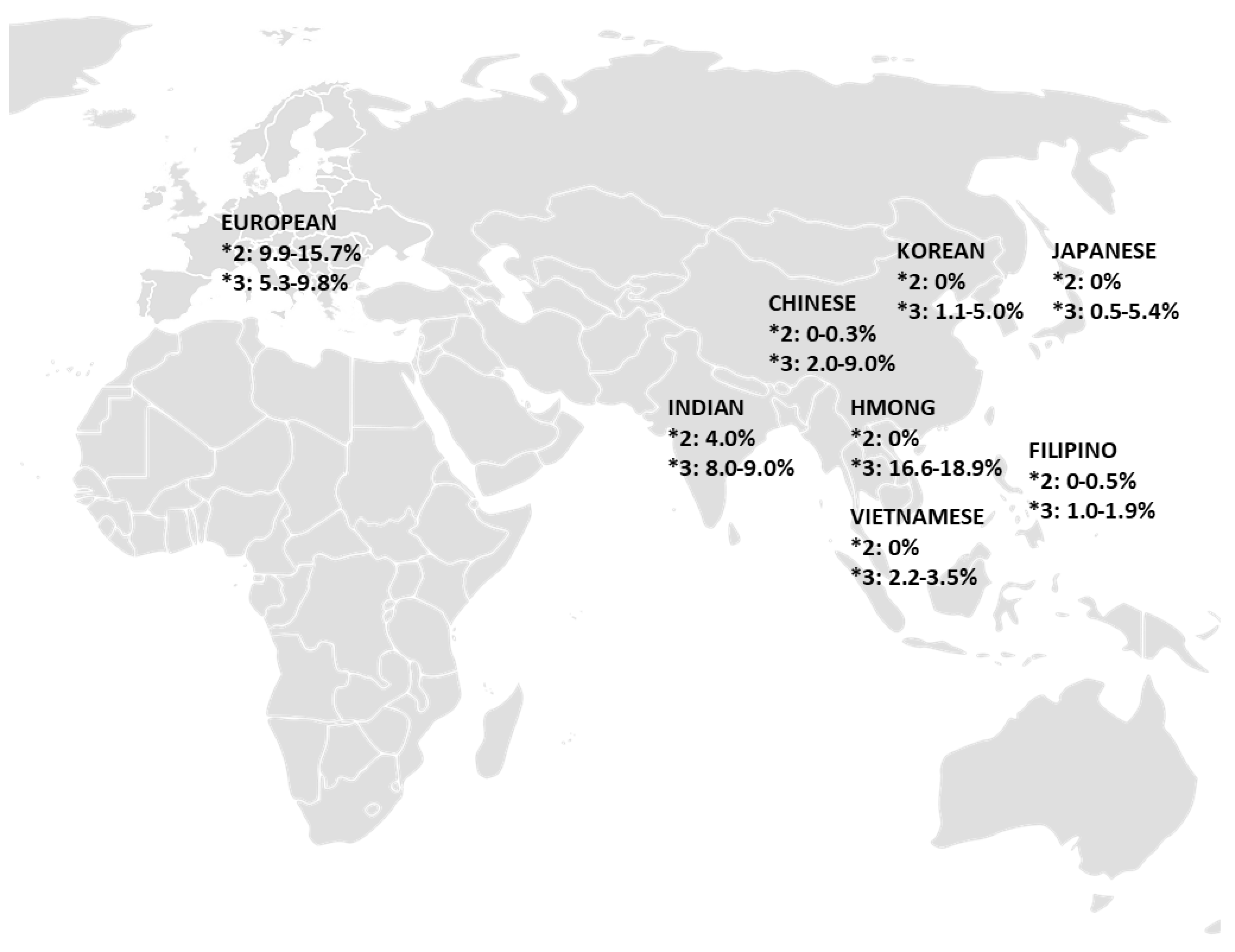

| Population | CYP2C9 Allele Frequency (%) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C9*2 | 2C9*3 | 2C9*5 | 2C9*8 | 2C9*11 | ||

| Overall European (Range) | 9.9 – 15.7 | 5.3 – 9.8 | ||||

|

14.7 | 7.6 | [19] | |||

|

12.1 | 5.3 | [20] | |||

|

9.9 | 6.5 | [20] | |||

|

11.3 | 9.3 | [21] | |||

|

11.7 | 8.1 | [22] | |||

|

15.6 | 9.8 | [23] | |||

|

15.7 | 7.8 | [24] | |||

| Overall Asian (Range) | 0 – 4.0 | 0.5 – 18.9 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 – 0.05 | |

|

0 – 0.3 | 2.0 – 9.0 | 0 | 1.8 | 0.05 | [25] |

|

0 – 0.5 | 1.0 – 1.9 | [11,26] | |||

|

0 | 16.6 – 18.9 | [27,28] | |||

|

4.0 | 8.0 – 9.0 | [29,30] | |||

|

0 | 0.5 – 5.4 | 0 | [11,25,29,31,32] | ||

|

0 | 1.1 – 5.0 | 0 | 0 | [11,25,29,31] | |

|

0 | 2.2 – 3.5 | [25,33] | |||

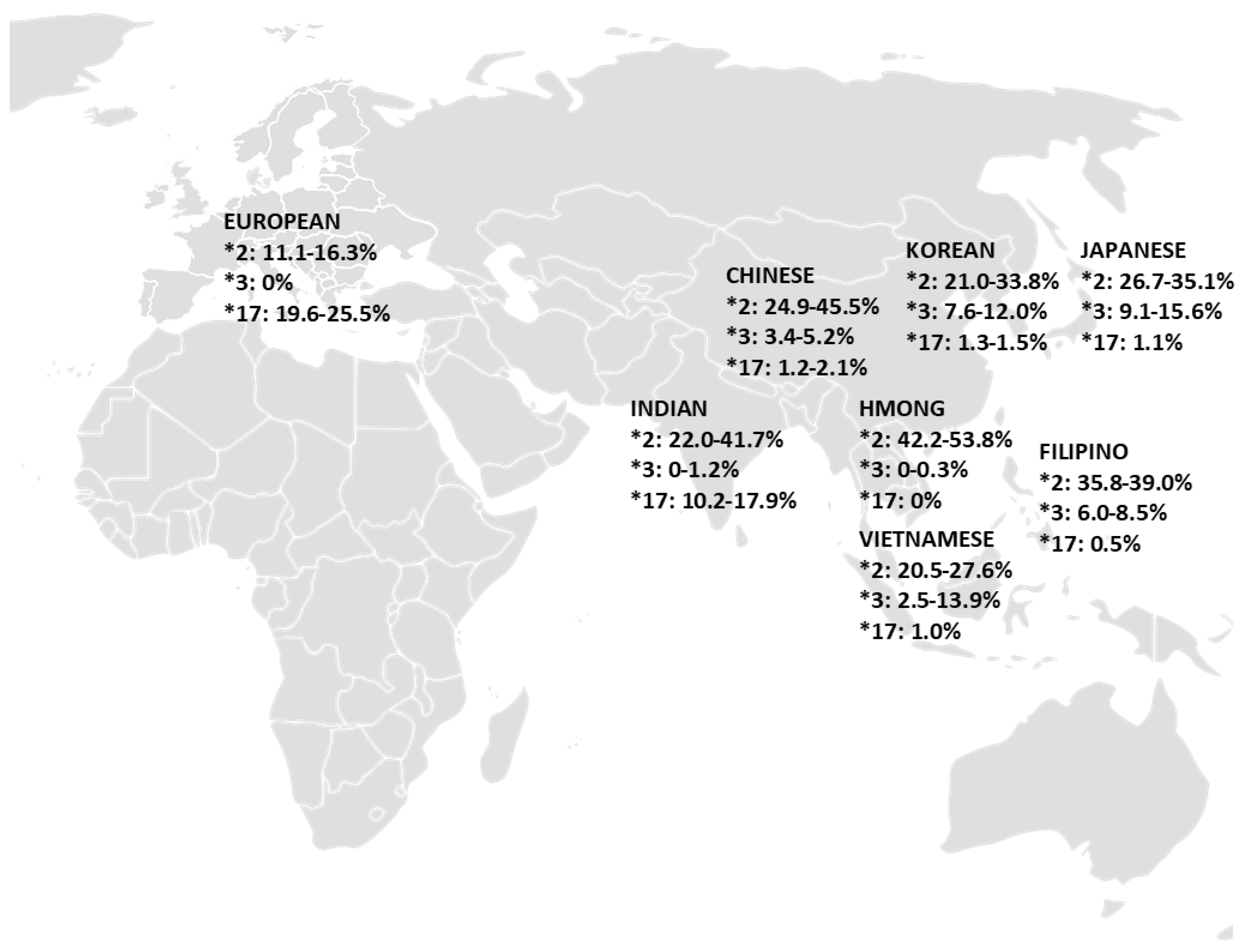

| Population | CYP2C19 Allele Frequency (%) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C19*2 | 2C19*3 | 2C19*17 | ||

| Overall European (Range) | 11.1 – 16.3 | 0 | 19.6 – 25.5 | |

|

0 | 23.9 | [19] | |

|

15.0 | 20.1 | [20] | |

|

15.2 | 0 | 25.5 | [34] |

|

13.1 | 0 | 19.6 | [35] |

|

11.1 | 0 | [36] | |

|

15.2 | 22.0 | [20] | |

|

16.3 | 22.2 | [22] | |

| Overall Asian (Range) | 20.5 – 53.8 | 0 – 15.6 | 0 – 17.9 | |

|

24.9 – 45.5 | 3.4 – 5.2 | 1.2 – 2.1 | [25,37,38,39,40] |

|

35.8 – 39.0 | 6.0 – 8.5 | 0.5 | [12,41] |

|

42.2 – 53.8 | 0 – 0.3 | 0 | [28] |

|

22.0 – 41.7 | 0 – 1.2 | 10.2 – 17.9 | [30,42,43,44,45] |

|

26.7 – 35.1 | 9.1 – 15.6 | 1.1 | [12,25,40,46,47] |

|

21.0 – 33.8 | 7.6 – 12.0 | 1.3 – 1.5 | [12,25,48,49,50] |

|

20.5 – 27.6 | 2.5 – 13.9 | 1.0 | [25,33,40,48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).