Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

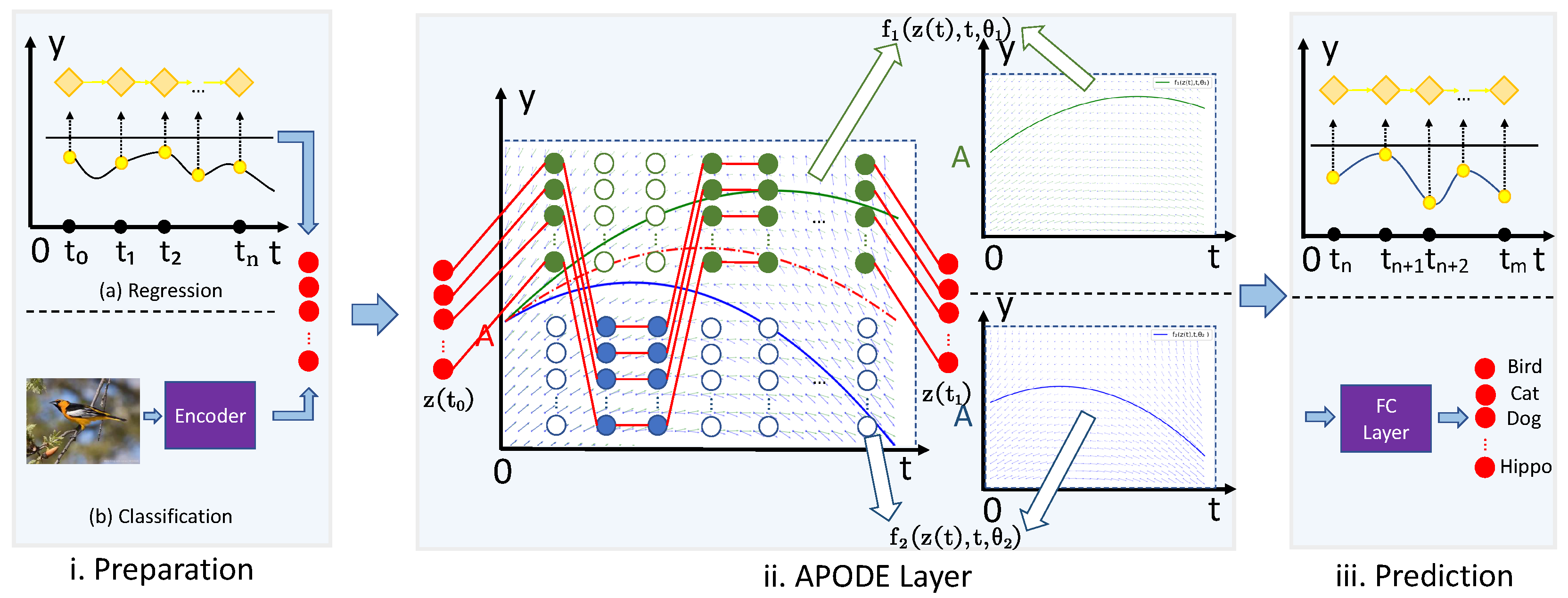

1. Introduction

- We propose an Alternate Propagating neural ODE model, namely APODE, which has achieved better robustness against one-dynamic-function-based NODEs.

- We provide theoretical proof and conduct experiments to verify that APODE improves expressive ability than traditional NODEs.

- We conduct experiments on classification and regression tasks to verify the effectiveness of APODE. Experimental results demonstrate that our APODE excels in achieving better robustness.

2. Preliminaries

3. Related Work

4. Model Architecture

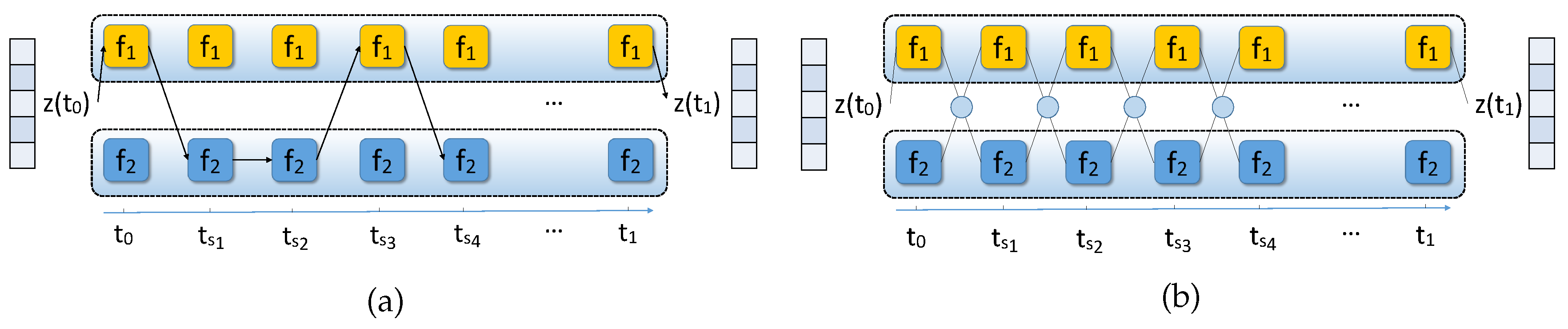

4.1. Alternate Propagating Neural ODEs

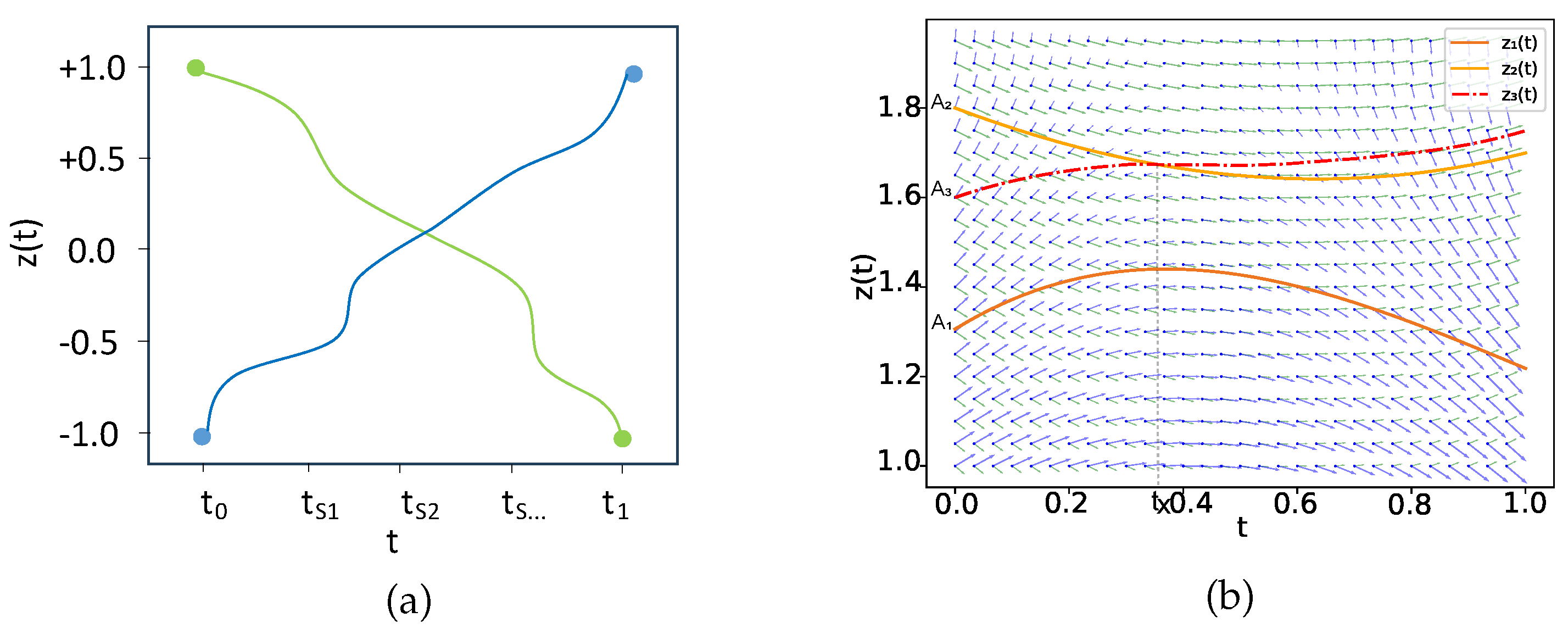

4.2. Insights into the Properties of APODE

4.3. Multiple Dynamic Functions of APODE

5. Discussion

6. Experiments

| Gaussian noise | Adversarial attack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mnist | =100 | FGSM-0.3 | FGSM-0.5 | PGD-0.2 | PGD-0.3 |

| CNN | 98.7±0.1 | 54.2±1.1 | 15.8±1.3 | 32.9±3.7 | 0±0 |

| ODENet | 99.4±0.1 | 71.5±1.1 | 19.9±1.2 | 64.7±1.8 | 13.0±0.2 |

| Neural SDE | 98.9±0.1 | 72.1±1.6 | 22.4±1.0 | 70.1±1.1 | 15.5±0.9 |

| TisODE | 99.6±0.1 | 75.7±1.4 | 26.5±3.8 | 67.4±1.5 | 13.2±1.0 |

| SODEF | 99.5±0.1 | 71.5±1.2 | 23.5±1.8 | 69.8±1.4 | 15.5±1.1 |

| SONet | 99.5±0.1 | 72.8±1.9 | 20.4±1.0 | 66.7±0.9 | 13.6±1.0 |

| APODE (OURS) | 99.3±0.1 | 75.7±0.5 | 28.4±1.2 | 77.4±0.4 | 28.9±1.4 |

| TisODE + APODE (OURS) | 99.6±0.1 | 80.4±0.1 | 40.9±1.8 | 78.5±0.1 | 37.5±3.6 |

| Gaussian noise | Adversarial attack | ||||

| SVHN | =35 | FGSM-5/255 | FGSM-8/255 | PGD-3/255 | PGD-5/255 |

| CNN | 90.6±0.2 | 25.3±0.6 | 12.3±0.7 | 32.4±0.4 | 14.0±0.5 |

| ODENet | 95.1±0.1 | 49.4±1.0 | 34.7±0.5 | 50.9±1.3 | 27.2±1.4 |

| Neural SDE | 95.3±0.1 | 56.6±1.1 | 40.8±1.1 | 59.7±0.6 | 42.6±0.3 |

| TisODE | 94.9±0.1 | 51.6±1.2 | 38.2±1.9 | 52.0±0.9 | 28.2±0.3 |

| SODEF | 95.0±0.1 | 55.1±1.1 | 38.8±1.5 | 59.9±0.9 | 33.6±0.7 |

| SONet | 94.8±0.2 | 52.3±0.8 | 36.9±0.9 | 55.7±1.4 | 30.5±0.9 |

| APODE (OURS) | 95.9±0.2 | 58.3±0.2 | 42.6±0.7 | 70.2±0.3 | 49.1±0.4 |

| TisODE + APODE (OURS) | 93.2±0.1 | 58.8±0.1 | 44.2±0.1 | 69.5±0.1 | 50.2±1.6 |

| Gaussian noise | Adversarial attack | ||||

| Cifar10 | =35 | FGSM-5/255 | FGSM-8/255 | PGD-3/255 | PGD-5/255 |

| CNN | 72.2±0.3 | 16.5±1.0 | 6.0±0.4 | 29.8±1.5 | 11.4±0.9 |

| ODENet | 73.5±0.2 | 20.0±0.7 | 9.3±0.1 | 30.8±1.1 | 13.2±0.4 |

| Neural SDE | 72.8±0.2 | 22.7±0.1 | 14.1±1.0 | 33.9±1.3 | 19.3±0.7 |

| TisODE | 73.2±0.4 | 19.6±0.5 | 8.4±0.3 | 30.8±1.2 | 12.2±0.9 |

| SODEF | 73.8±0.2 | 21.3±0.3 | 10.7±0.3 | 37.4±1.0 | 25.1±0.8 |

| SONet | 73.9±0.4 | 22.8±0.4 | 11.4±0.6 | 35.1±0.8 | 23.7±0.6 |

| APODE (OURS) | 74.3±0.3 | 29.5±0.7 | 16.2±0.2 | 50.8±1.6 | 33.8±0.7 |

| TisODE + APODE (OURS) | 74.2±0.2 | 30.1±1.4 | 16.2±0.8 | 49.8±0.5 | 32.5±0.2 |

6.1. Experimental Details

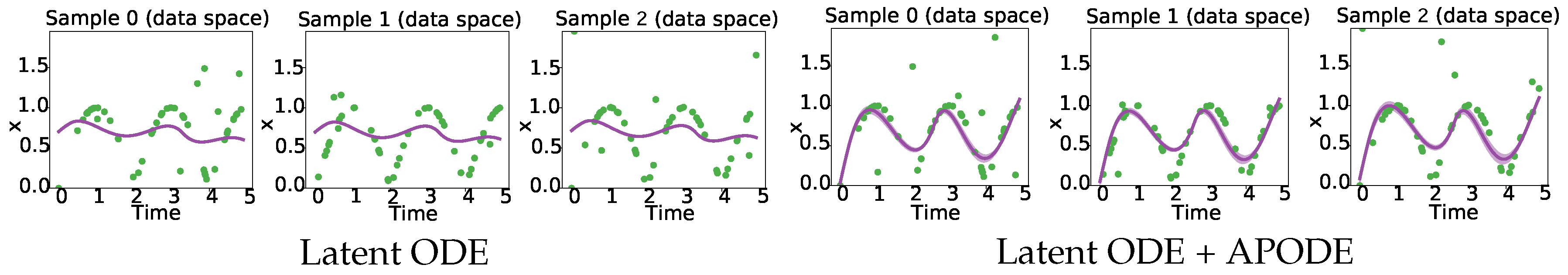

- Toy dataset: We generate trajectories consisting of 50 time points within the interval [0, 5]. We evaluate the performance of APODE in experimental settings where datasets with noise data make up around 10% of the total data. The noise perturbations are sampled from a uniform distribution, with values fluctuating within the range of 0 to 2.

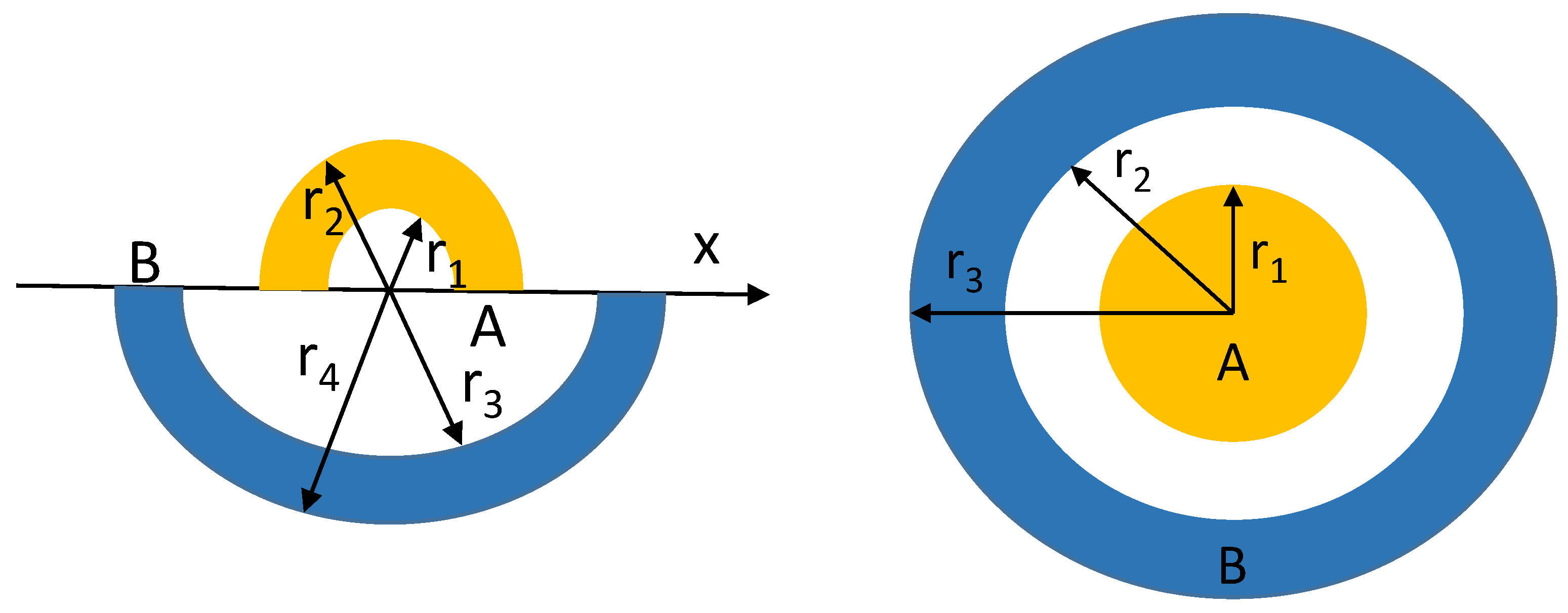

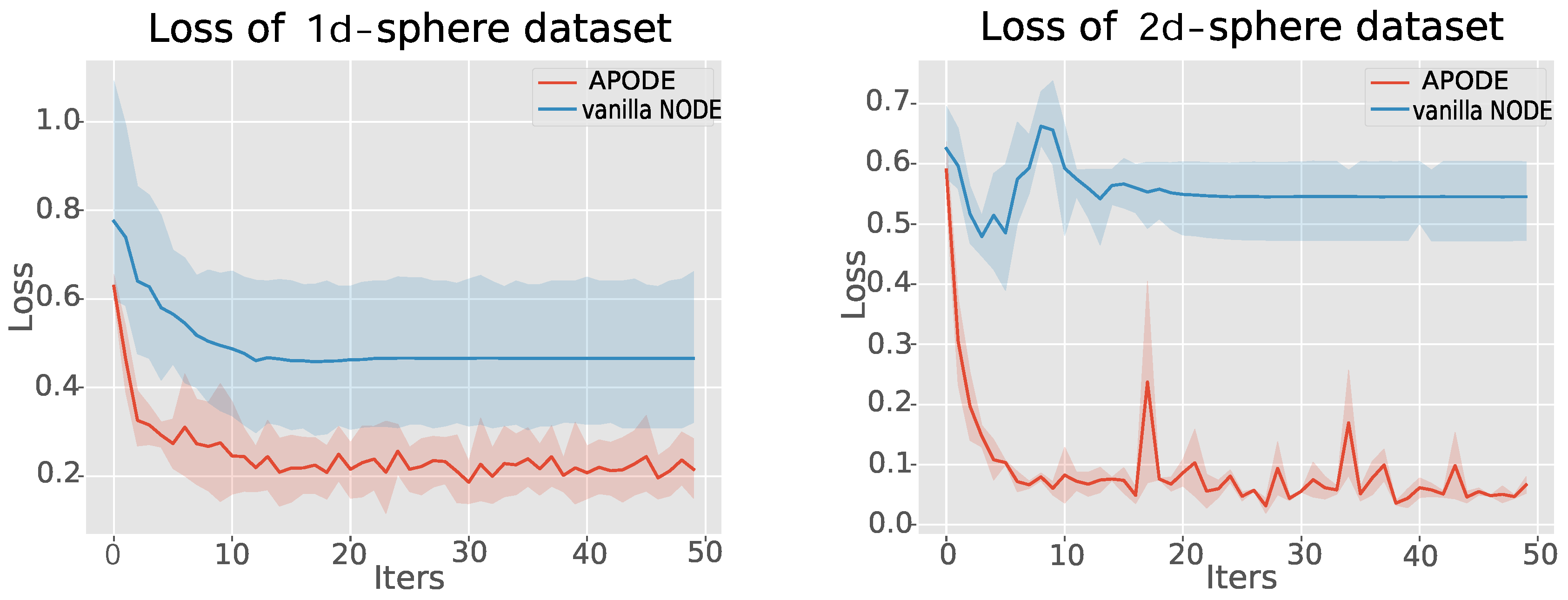

- 1d and 2d sphere datasets: We conduct experiments on two concentric annulus problems, including 1d and 2d sphere datasets.

6.2. Research Questions

6.3. RQ1: Robustness Analysis

6.4. RQ2: Functions NODEs Cannot Represent

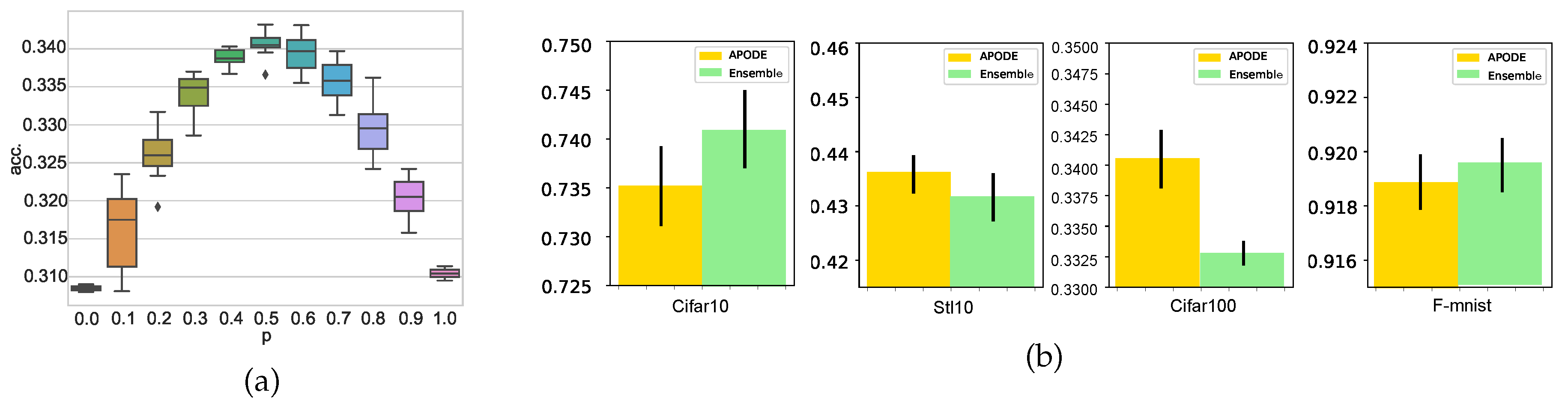

6.5. RQ3: Examination on Ensemble Property of APODE

6.6. RQ4: Results for Time Series Datasets with Noise

7. Conclusion

References

- Ruiz-Balet, D.; Zuazua, E. Neural ode control for classification, approximation, and transport. SIAM Review 2023, 65, 735–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linot, A.J.; Burby, J.W.; Tang, Q.; Balaprakash, P.; Graham, M.D.; Maulik, R. Stabilized neural ordinary differential equations for long-time forecasting of dynamical systems. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 474, 111838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.T.; Rubanova, Y.; Bettencourt, J.; Duvenaud, D.K. Neural ordinary differential equations. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, W.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, L. A survey on green deep learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.05193. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.Z.; Zuo, T.Y.; Law, R.; Wu, E.Q.; Song, A. Neural Network Ensemble With Evolutionary Algorithm for Highly Imbalanced Classification. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lian, C.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, B.; Su, Y. An aggregated convolutional transformer based on slices and channels for multivariate time series classification. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovanev, Y.; Hvatov, A. On the balance between the training time and interpretability of neural ODE for time series modelling. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.03304. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Du, J.; Tan, V.Y.; Feng, J. On robustness of neural ordinary differential equations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.05513. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, T.; Si, S.; Cao, Q.; Kumar, S.; Hsieh, C.J. Neural sde: Stabilizing neural ode networks with stochastic noise. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02355. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Q.; Song, Y.; Ding, Q.; Tay, W.P. Stable neural ode with lyapunov-stable equilibrium points for defending against adversarial attacks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 14925–14937. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Benner, P. Neural ordinary differential equations with irregular and noisy data. Royal Society Open Science 2023, 10, 221475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinot, R.; Ettedgui, R.; Rizk, G.; Chevaleyre, Y.; Atif, J. Randomization matters how to defend against strong adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 7717–7727.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Shi, Z.; Osher, S. Resnets ensemble via the feynman-kac formalism to improve natural and robust accuracies. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Pinot, R.; Meunier, L.; Araujo, A.; Kashima, H.; Yger, F.; Gouy-Pailler, C.; Atif, J. Theoretical evidence for adversarial robustness through randomization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Lipton, Z.C.; Bernstein, J.; Kossaifi, J.; Khanna, A.; Anandkumar, A. Stochastic activation pruning for robust adversarial defense. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01442. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, E.; Doucet, A.; Teh, Y.W. Augmented neural odes. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.01681. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Behl, H.S.; Dupont, E.; Torr, P.H.; Namboodiri, V. Steer: Simple temporal regularization for neural odes. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10711. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, L. Shapes and diffeomorphisms; Vol. 171, Springer, 2010.

- Kidger, P.; Foster, J.; Li, X.C.; Lyons, T. Efficient and accurate gradients for neural sdes. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 18747–18761. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Tran, D.; Ba, J. Batchensemble: an alternative approach to efficient ensemble and lifelong learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.06715. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi, O.; Rokach, L. Ensemble learning: A survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2018, 8, e1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yu, Z.; Cao, W.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Q. A survey on ensemble learning. Frontiers of Computer Science 2020, 14, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ning, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Ensemble-in-One: Learning Ensemble within Random Gated Networks for Enhanced Adversarial Robustness. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H.; Inkawhich, N.; Gardner, A.; Touchet, A.; Wilkes, W.; Berry, H.; Li, H. DVERGE: diversifying vulnerabilities for enhanced robust generation of ensembles. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 5505–5515. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.W. Iterative solution of games by fictitious play. Act. Anal. Prod Allocation 1951, 13, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. Journal of computer and system sciences 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, B.; Chuang, Z. Horizontal and vertical ensemble with deep representation for classification. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1306.2759. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Li, Y.; Pleiss, G.; Liu, Z.; Hopcroft, J.E.; Weinberger, K.Q. Snapshot ensembles: Train 1, get m for free. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.00109. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, E.A.; Levinson, N. Theory of ordinary differential equations; Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 1955.

- Stewart, J. Calculus; Cengage Learning, 2015.

- Claeskens, G.; Hjort, N.L.; et al. Model selection and model averaging. Cambridge Books 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, J.M.; Granger, C.W. The combination of forecasts. Journal of the operational research society 1969, 20, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, H.; Shanbhag, N. Adversarial vulnerability of randomized ensembles. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. 2022; pp. 4890–4917. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.06083. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Yao, Y. Adversarial robustness of stabilized neural ode might be from obfuscated gradients. In Proceedings of the Mathematical and Scientific Machine Learning. PMLR. 2022; pp. 497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images. Master’s thesis, University of Tront, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, Y.; Wang, T.; Coates, A.; Bissacco, A.; Wu, B.; Ng, A.Y. Reading digits in natural images with unsupervised feature learning 2011.

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R. Fashion-mnist: a novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07747. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

| PGD | ARC | |

| NODE | 64.7 | - |

| APODE* | 78.0 | 68.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).