Background

The idea that the heart has an emotional memory has been regarded for decades as symbolic and metaphorical than scientifically proven. While the heart is central to emotional experiences in many cultures and traditions—often seen as the seat of feelings—scientific research indicates that emotional memory and processing primarily involve the brain, particularly areas like the amygdala and hippocampus[

1]

Recent scientific developments have uncovered the presence of sensory neurons in the heart, which can communicate with the nervous system and influence emotional and physiological responses. The concept of “heart memory transfer” is an emerging field, and some studies suggest that the heart’s neural network might play a role in processing emotional information in ways that are not yet fully understood[

2].

The heart contains an extensive network of neurons known as the

intrinsic cardiac nervous system, sometimes called the “heart brain.” This network can process information and communicate with the central nervous system, influencing emotional states and physiological responses. Some researchers propose that this neural system might contribute to emotional memory, or at least affect how emotional experiences are felt and remembered[

3].

In this article, we aim to elucidate the intricate connections between the heart and brain, highlighting that the heart is much more than a mere pump.

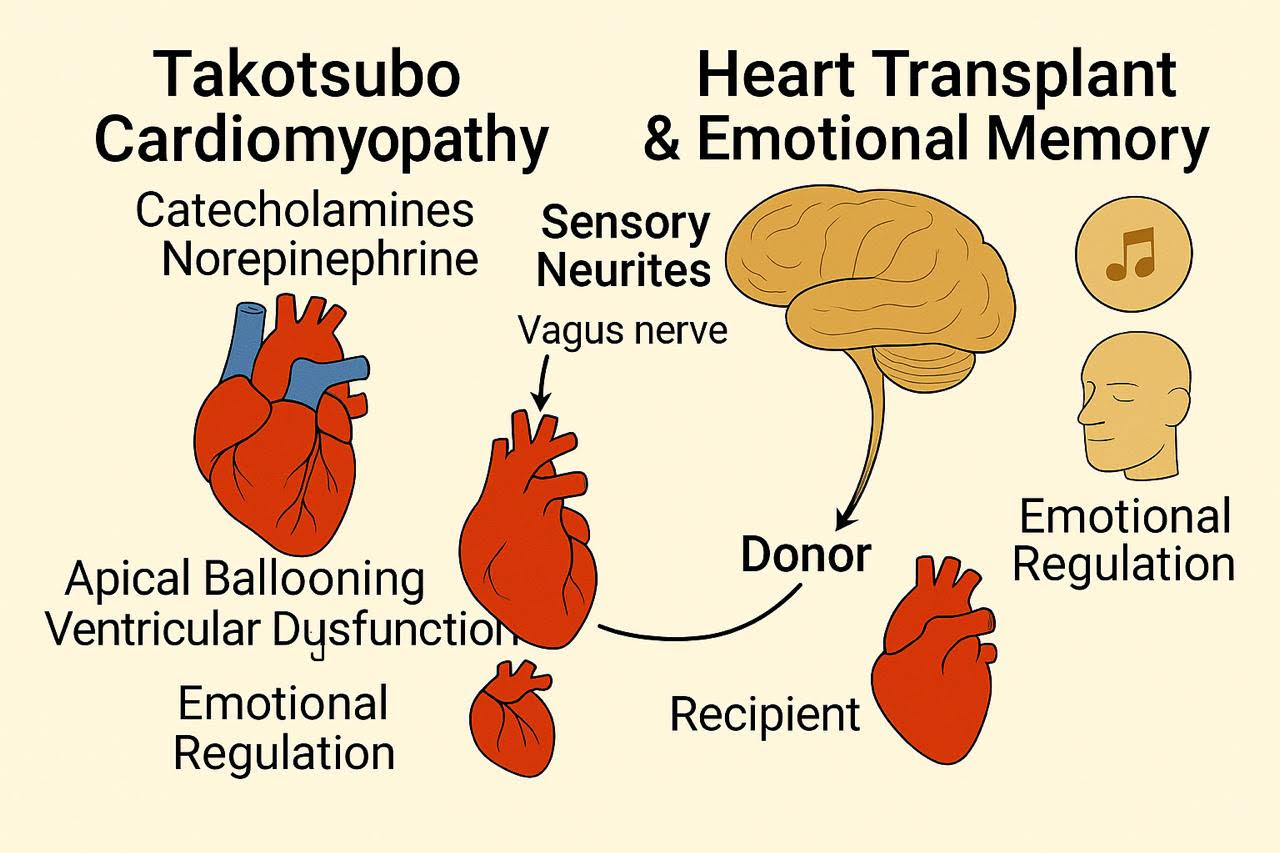

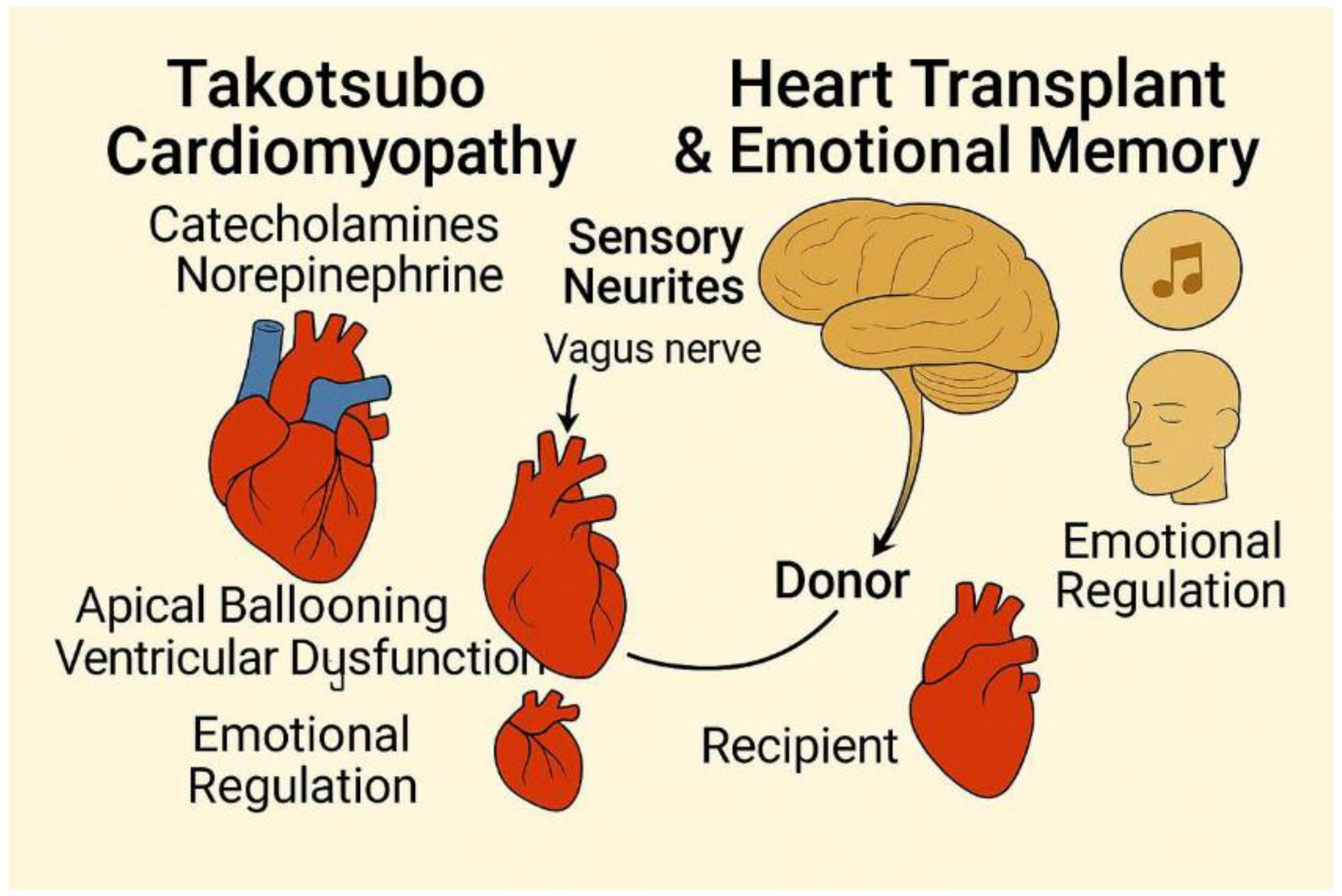

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract summarizing the main evidences of emotional connections of the brain.

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract summarizing the main evidences of emotional connections of the brain.

Main Body

I-A Vice-Versa Relationship Between the Heart and Brain

A-Witnesses from Heart Transplant Recipient

As of today, June 5th, 2025, approximately 3,500 to 4,000 heart transplants are performed worldwide each year. The United States accounts for the largest proportion, with around 2,500 to 3,000 transplants annually. Factors influencing these numbers include organ availability, advancements in surgical techniques, and improvements in post-transplant care, which have significantly enhanced survival rates and expanded eligibility criteria[

4].

Heart transplant recipients experiences have been reported in an interesting article by Pearsall et al. experiencing, displaying significant changes in their personalities, preferences, and behaviors that often mirror those of their donors. These changes include shifts in food preferences, artistic tastes, musical interests, and even career aspirations. Some recipients have described acquiring new skills or knowledge that align with the donor’s passions, such as being able to complete songs the donor wrote or developing a sudden love for classical music despite previously disliking it. These experiences suggest a transfer of personal history or emotional memory from the donor to the recipient[

5].

Beyond changes in preferences, some recipients have reported more profound connections to their donors, including sensory experiences and emotional insights. For instance, one recipient had dreams of seeing flashes of light in his face, mirroring the way the donor was killed by a gunshot. Others have described feeling the presence of their donor, experiencing their emotions, or even having conversations with them. These accounts suggest a deeper, more intimate connection that goes beyond mere behavioral changes[

6].

The families of both donors and recipients often corroborate these accounts, noting striking similarities between the recipients’ new behaviors and the donors’ personalities. These observations lend credibility to the recipients’ experiences and challenge conventional understandings of memory and identity. While the exact mechanisms behind these phenomena remain unclear, the consistent patterns reported across multiple cases suggest that cellular memory or systemic memory may play a role in the transfer of personal characteristics from donor to recipient [

4,

5,

7].

C. Improvement of Myocardial Stunning via Sensory Stimuli Particularly Music

Music therapy is gaining traction as a valuable supportive intervention in critical care, particularly for patients recovering from cardiac events like myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grafting. Its benefits stem from its ability to modulate the autonomic nervous system, promoting physiological stabilization, and to enhance psychological well-being, crucial for holistic cardiac recovery. Calming music demonstrably reduces sympathetic nervous system activity while bolstering parasympathetic responses, resulting in favorable cardiovascular outcomes: lowered heart rate, reduced blood pressure, and decreased respiratory rate. A systematic review highlighted music interventions’ ability to improve autonomic balance across various clinical settings, evidenced by statistically significant reductions in blood pressure and heart rate[

12]. The slow tempo of genres like classical or meditative music appears particularly effective in offering a safe and cost-effective adjunct to traditional cardiovascular support in the ICU.

Beyond physiological effects, music therapy significantly addresses psychological stressors commonly associated with acute cardiac events, such as anxiety and post-traumatic symptoms, which can negatively impact recovery. Meta-analyses of cardiac surgery patients have revealed that music exposure significantly reduces anxiety and pain compared to standard care[

13]. These therapeutic benefits are believed to arise from music engaging the brain’s emotional centers, stimulating the release of dopamine and oxytocin, and thus counteracting the physiological effects of stress. This translates to a decreased reliance on sedatives and analgesics, minimizing medication-related side effects and potentially accelerating recovery. Recent evidence continues to support these findings; a randomized controlled trial showed that music therapy significantly reduced pain, anxiety, agitation, and sedation requirements in cardiac ICU patients following coronary angiography[

14,

15].

The integration of structured music therapy into ICU care protocols for post-cardiac event patients offers promising clinical benefits, aligning with a holistic, patient-centered approach. While these findings support the standardization of music as an ICU nursing protocol component, further research is warranted. Future studies should focus on developing tailored music interventions that account for individual patient preferences, cultural backgrounds, and neurological responses to different musical styles to maximize therapeutic efficacy and promote personalized care.

II-Anatomical Explanations of Heart-Brain Connections

A-The Amygdala Connections with Cardiovascular Centers in the Brain Stem

The intricate interplay between the brain and heart forms a dynamic, bidirectional communication system that profoundly influences both emotional and physiological states. A key component in this circuit is the amygdala, a limbic system structure responsible for processing emotional stimuli and modulating autonomic functions, notably heart rate and blood pressure (1). This regulation is achieved through complex neural networks encompassing both the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system, allowing for a nuanced control of cardiac activity[

3,

16,

17].

The central nucleus of the amygdala, a critical hub within this system, possesses direct anatomical links to brainstem regions governing cardiovascular control, including the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMNV) (1). These connections facilitate the amygdala’s ability to directly influence cardiac function. Furthermore, functional MRI (fMRI) studies have demonstrated that fluctuations in heart rate are correlated with changes in amygdala activity, underscoring the presence of a tightly regulated feedback loop between emotional processing and cardiovascular function (2). This suggests that emotional experiences can rapidly and directly impact heart function, and conversely, that signals from the heart can influence emotional processing in the brain[

18].

Given its central role in emotional regulation, the amygdala significantly influences heart rate variability (HRV), a well-established marker of autonomic nervous system balance and adaptability (3). Higher HRV generally indicates greater autonomic flexibility and better cardiovascular health, while reduced HRV is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events.

B-A New Breakthrough: Sensory Neurites of the Heart

Sensory neurites, recently discovered in the heart, are specialized nerve fibers that play a vital role in regulating cardiac activity and are implicated in both memory transfer and decision-making. With approximately 40,000 cells present in the heart, these neurites form an intrinsic neural system that integrates extrinsic innervation inputs and influences short-term and long-term memory functions[

2,

3,

19].

These sensory neurites modulate their effects by transmitting neural signals through ascending pathways via the vagus nerve and spinal cord, ultimately reaching the amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, and cerebral cortex. By influencing these brain regions, the sensory neurites can impact various types of decisions, including physiological, behavioral, and psychological ones. The potential mechanisms involve modulating cognition and mood regulation.

The sensory neurites act as transducers, converting mechanical and chemical stimuli into electrical signals. Mechano-sensory neurites respond to physical changes such as muscle deformation, while chemosensory neurites detect changes in the chemical environment, such as adenosine release during ischemia. These signals are then transmitted to the brain, where they can influence perception, emotions, and decision-making processes. This suggests that the heart can contribute not only to physiological regulation but also to cognitive and emotional processes through these sensory neurites[

20].

Conclusion

The evidence presented challenges the conventional view of the heart as a mere circulatory organ, revealing its intricate involvement in emotional and cognitive processes through neuroanatomical connections. Reports of personality changes in heart transplant recipients and the functionality of intrinsic cardiac sensory neurites suggest a role for the heart in memory and decision-making. Recognizing the heart’s active role in the heart-brain axis opens new avenues for exploring therapeutic interventions targeting the interplay between emotional and physiological health, particularly in managing stress-related cardiovascular conditions and promoting holistic patient care. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms and clinical implications of this dynamic two-way communication system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AFA; Methodology, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; software, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; investigation, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; resources, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA, data curation, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; writing—original draft preparation, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; writing—review and editing, AFA, BO, NK, TS, MS, MA, LAS, RA; supervision, AFA; project administration, AFA; funding acquisition, (non-applicable). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

not applicable as this study is a hypothesis/Review article.

Informed Consent Statement

not applicable as this study is a viewpoint/editorial

Data Availability Statement

All data is made available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

To the peacekeepers in every part of the world, in every community, every family and every tiny relationship. Peace keeping might sometimes look like weakness, but it requires utmost strength.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The manuscript is submitted under Creative Commons Licensing CC-BY-NC-ND

List of Abbreviations

| AR |

Adrenergic receptors |

| TCM |

Takatsubo cardiomyopathy |

| LV |

Left Ventricle |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| NTS |

Nucleus Tractus solitarius |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic resonance imaging |

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

References

- Rosen M. The heart remembers. Cardiovasc Res [Internet]. 1998 Dec 1;40(3):469–82. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cardiovascres/article-lookup/doi/10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00208-9. [CrossRef]

- Durães Campos I, Pinto V, Sousa N, Pereira VH. A brain within the heart: A review on the intracardiac nervous system. J Mol Cell Cardiol [Internet]. 2018 Jun;119:1–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022282818301007. [CrossRef]

- Rosen MR, Binah O, Marom S. Cardiac Memory and Cortical Memory. Circulation [Internet]. 2003 Oct 14;108(15):1784–9. [CrossRef]

- Bunzel B, Schmidl-Mohl B, Grundböck A, Wollenek G. Does changing the heart mean changing personality? A retrospective inquiry on 47 heart transplant patients. Qual Life Res [Internet]. 1992 Aug;1(4):251–6. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00435634. [CrossRef]

- Pearsall P, Schwartz GE., Russek LG. Changes in heart transplant recipients that parallel the personalities of their donors. Integr Med [Internet]. 2000 Mar;2(2–3):65–72. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1096219000000135. [CrossRef]

- Nour El Hadi S, Zanotti R, Danielis M. Lived experiences of persons with heart transplantation: A systematic literature review and meta-synthesis. Hear Lung [Internet]. 2025 Jan;69:174–84. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0147956324002036. [CrossRef]

- Liester MB. Personality changes following heart transplantation: The role of cellular memory. Med Hypotheses [Internet]. 2020;135(June 2019):109468. [CrossRef]

- Singh T, Khan H, Gamble DT, Scally C, Newby DE, Dawson D. Takotsubo Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Emerging Concepts, and Clinical Implications. Circulation [Internet]. 2022 Mar 29;145(13):1002–19. [CrossRef]

- Wilkhoo HS, Visvanathan H, Chatterjee S, Hussain S, Gundaniya P, Francis V, et al. Current Clinical Perspectives on Takotsubo Syndrome: Comprehensive analysis of Diagnosis, Management, and Pathophysiology. Int J Cardiovasc Acad [Internet]. 2024 Nov 13; Available from: https://ijcva.org/articles/current-clinical-perspectives-on-takotsubo-syndrome-comprehensive-analysis-of-diagnosis-management-and-pathophysiology/doi/ijca.2024.63825. [CrossRef]

- Ghadri JR, Sarcon A, Diekmann J, Bataiosu DR, Cammann VL, Jurisic S, et al. Happy heart syndrome: role of positive emotional stress in takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1;37(37):2823–9. [CrossRef]

- Stiermaier T, Eitel I. Happy heart syndrome–The impact of different triggers on the characteristics of takotsubo syndrome. Trends Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2025 Apr;35(3):197–201. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1050173824001099. [CrossRef]

- Loomba RS, Arora R, Shah PH, Chandrasekar S, Molnar J. Effects of music on systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate: a meta-analysis. Indian Heart J [Internet]. 2012 May;64(3):309–13. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0019483212600947. [CrossRef]

- Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet [Internet]. 2015 Oct;386(10004):1659–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615601696. [CrossRef]

- Luis M, Doss R, Zayed B, Yacoub M. Effect of live oud music on physiological and psychological parameters in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract [Internet]. 2019 Sep 20;2019(2):e201917. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31799291. [CrossRef]

- Santos KVG dos, Dantas JK dos S, Fernandes TE de L, Medeiros KS de, Sarmento ACA, Ribeiro KRB, et al. Music to relieve pain and anxiety in cardiac catheterization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon [Internet]. 2024 Jul;10(13):e33815. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844024098463. [CrossRef]

- Miller M. Emotional Rescue: The Heart-Brain Connection. Cerebrum [Internet]. 2019;2019. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32206169.

- Cirillo M. The Memory of the Heart. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis [Internet]. 2018 Nov 11;5(4):55. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2308-3425/5/4/55. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Tudusciuc O, Mamelak AN, Ross IB, Adolphs R, Rutishauser U. Neurons in the human amygdala selective for perceived emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(30). [CrossRef]

- Achanta S, Gorky J, Leung C, Moss A, Robbins S, Eisenman L, et al. A Comprehensive Integrated Anatomical and Molecular Atlas of Rat Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System. iScience [Internet]. 2020 Jun;23(6):101140. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2589004220303254. [CrossRef]

- Hoebart C, Kiss A, Podesser BK, Tahir A, Fischer MJM, Heber S. Sensory Neurons Release Cardioprotective Factors in an In Vitro Ischemia Model. Biomedicines [Internet]. 2024 Aug 15;12(8):1856. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/12/8/1856. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).