Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

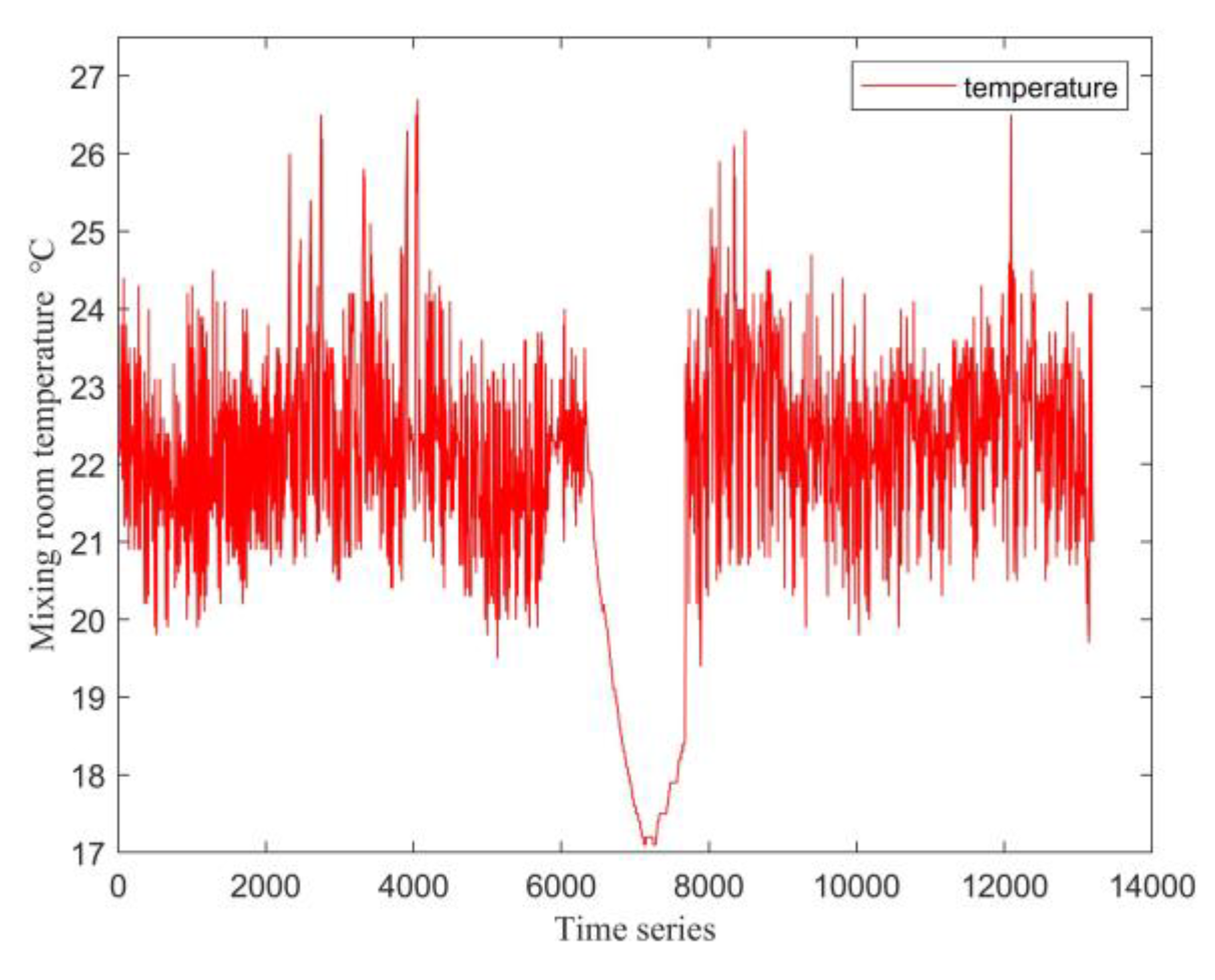

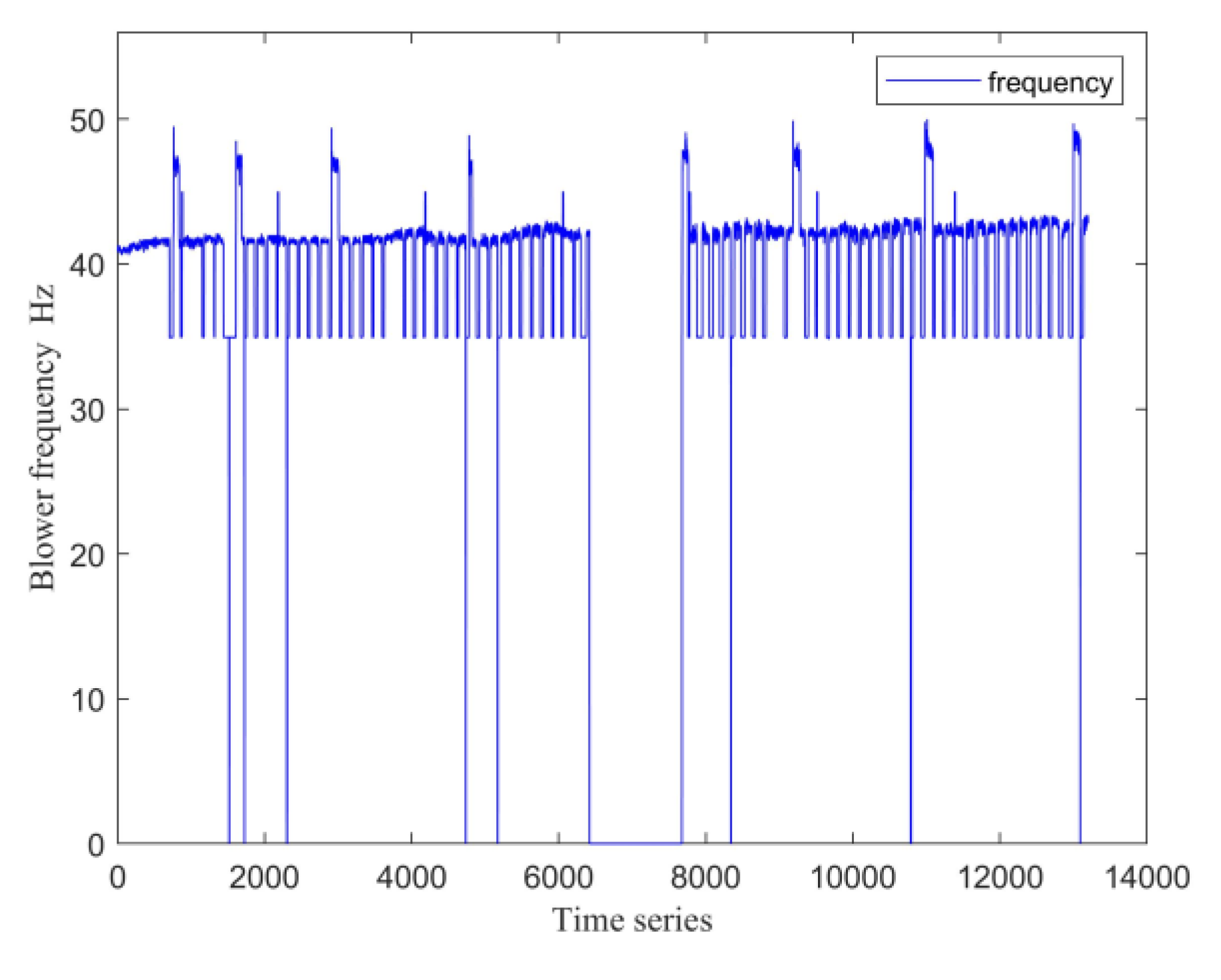

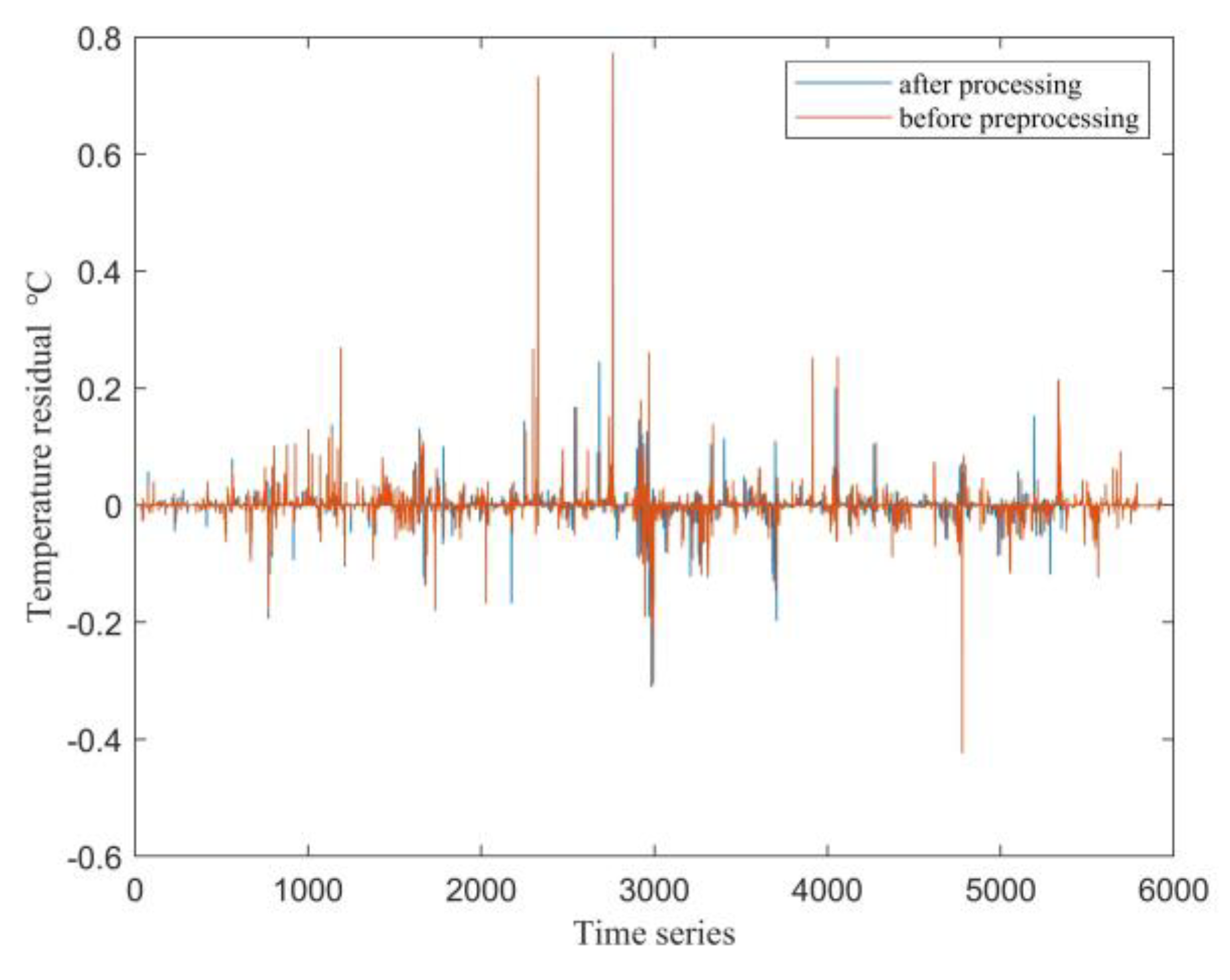

2.1. Data Preprocessing

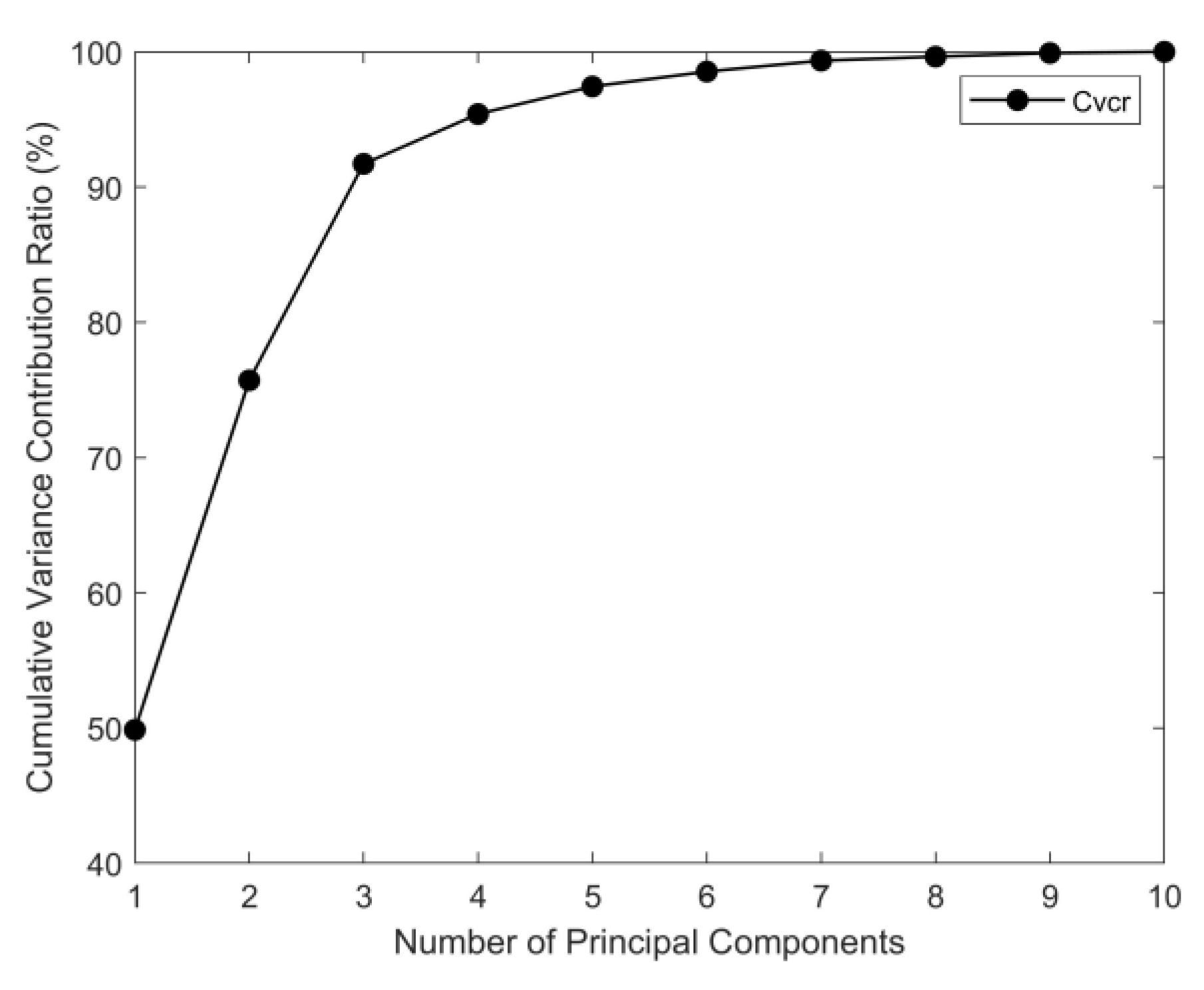

2.2. Feature Selection and Principal Component Analysis

2.3. Nonlinear State Estimation Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data Preprocessing Effects

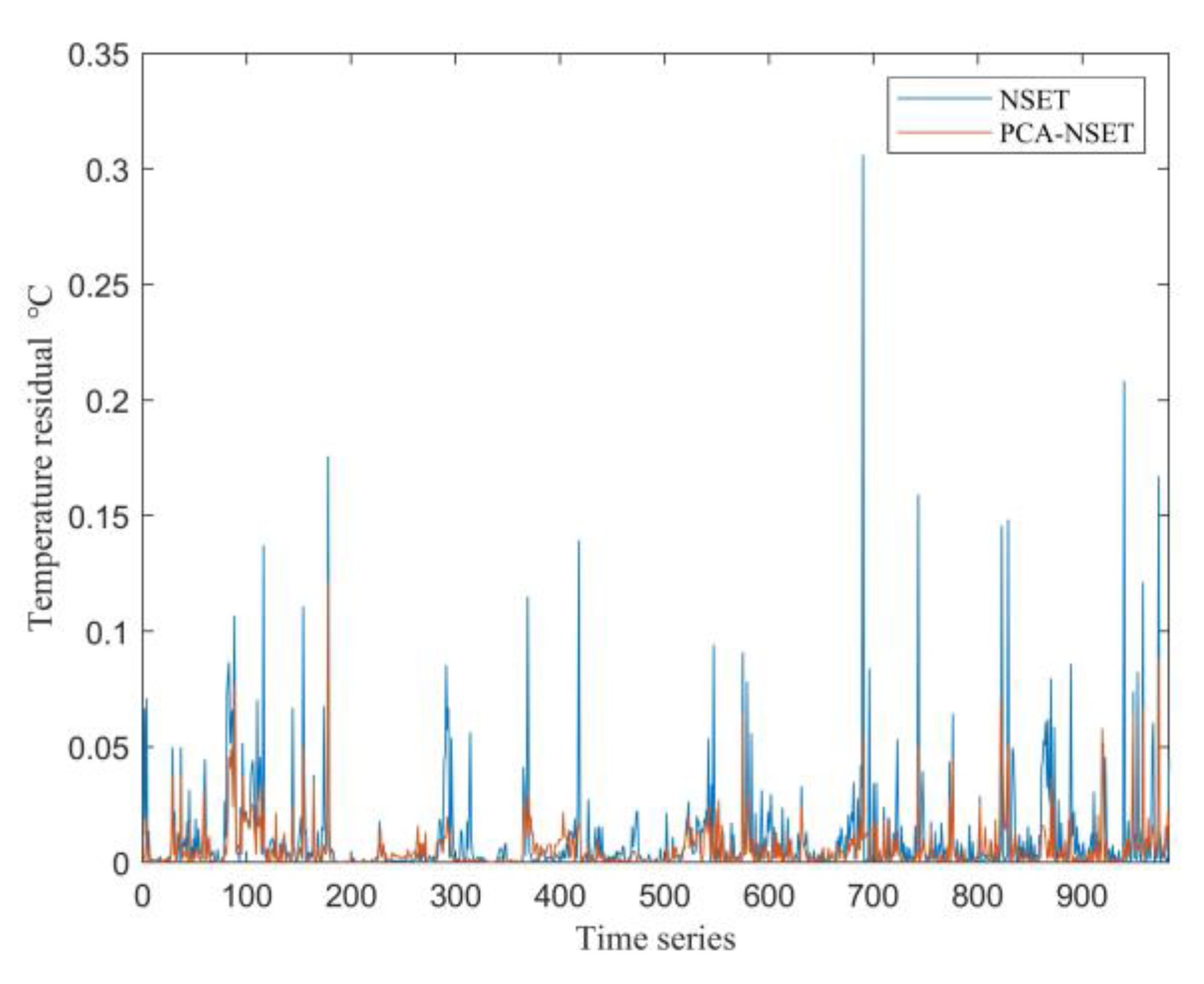

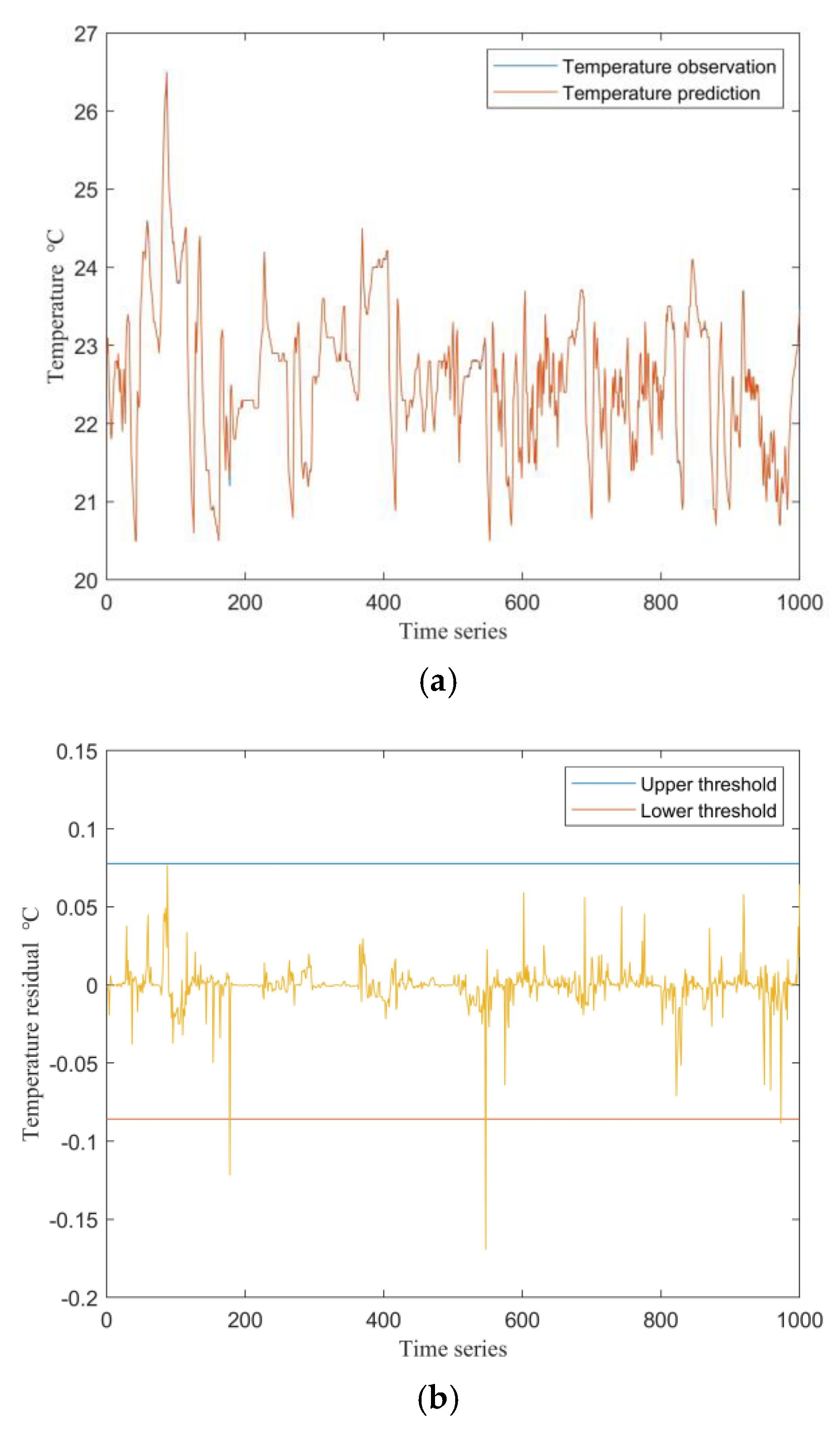

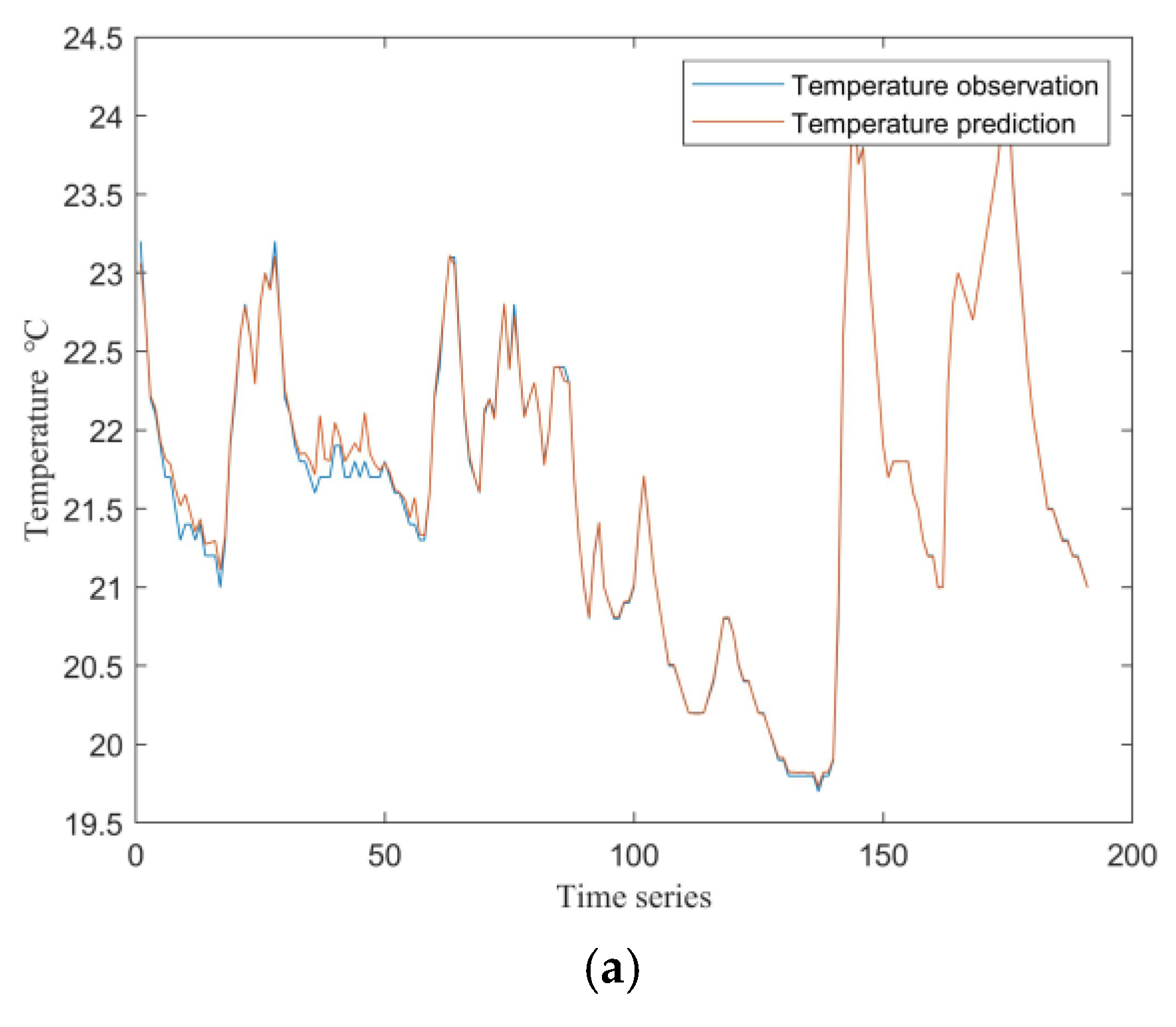

3.2. Model Comparison and Fault Detection Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qin, S. Joe. Survey on data-driven industrial process monitoring and diagnosis. Annual Reviews in Control 36.2 (2012): 220-234. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L.H., Russell, E.L., & Braatz, R.D. Fault diagnosis in chemical processes using Fisher discriminant analysis, discriminant partial least squares, and principal component analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 50.2 (2000): 243-252. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shiyu, & Qin, S. Joe. A new subspace identification approach for modeling and control of HVAC systems. Control Engineering Practice 16.7 (2008): 796-808. [CrossRef]

- Li, Wei, et al. Data-driven HVAC system modeling and prediction: A review. Energy and Buildings 209 (2020): 109656. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Bin, et al. “A review on fault detection and diagnosis for HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 72 (2014): 154-162. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Shoubin, et al. “A review on advances in data-driven fault detection and diagnosis for building energy systems.” Energy and Buildings 248 (2021): 111174. [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, V., et al. “A review of process fault detection and diagnosis: Part I: Quantitative model-based methods.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 27.3 (2003): 293-311. [CrossRef]

- Alcala, C.F., & Qin, S. Joe. “Detection and diagnosis of process faults based on principal component analysis.” Journal of Process Control 19.10 (2009): 1793-1803.

- Russell, E.L., Chiang, L.H., & Braatz, R.D. “Data-driven techniques for fault detection and diagnosis in chemical processes.” Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S. Joe. “Statistical process monitoring: basics and beyond.” Journal of Chemometrics 17.8-9 (2003): 480-502. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., et al. “A practical approach for model-based fault detection and diagnosis in HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 216 (2020): 109942. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., et al. “Review on data-driven modeling and optimization for building energy systems.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 137 (2021): 110591. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., & He, S. “Fault detection and diagnosis for building air handling units using machine learning and expert knowledge.” Energy and Buildings 219 (2020): 110007. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Xiang, et al. “A data-driven approach for fault detection and diagnosis in building HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 218 (2020): 110018. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., & Qin, S. Joe. “Multivariate statistical monitoring using dynamic principal component analysis.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 40.15 (2001): 3382-3401.

- Shang, Chuanbo, & You, Qingchun. “A hybrid intelligent method for fault detection and diagnosis of HVAC systems based on PCA and Fuzzy ARTMAP neural network.” Building and Environment 196 (2021): 107792. [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, V. “Process fault detection and diagnosis: past, present and future.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 27.3 (2003): 293-311. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., et al. “Nonlinear state estimation technique for wind turbine condition monitoring and fault diagnosis.” Renewable Energy 138 (2019): 636-648. [CrossRef]

- Li, Yan, et al. “Review of building energy modeling for control and operation.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 137 (2021): 110608. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Wei, et al. “A survey on data-driven fault detection and diagnosis for HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 225 (2020): 110322. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Li, et al. “Nonlinear state estimation for process monitoring and fault diagnosis: A review.” Journal of Process Control 87 (2020): 13-27. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., et al. “Data-driven techniques in fault detection and diagnosis for HVAC systems: A review.” Applied Energy 272 (2020): 115127. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., et al. “Model predictive control for the operation of building cooling systems: Review and future opportunities.” Applied Energy 179 (2016): 47-61. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., et al. “A survey of data-driven building fault detection and diagnosis.” Energy and Buildings 203 (2019): 109434. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Xiao, F. “A review on model predictive control for buildings.” Building and Environment 105 (2016): 301-312. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Steven X., et al. “Data-driven design of fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control systems.” Annual Reviews in Control 44 (2017): 84-105. [CrossRef]

- Li, Haibo, et al. “A hybrid PCA-based fault detection approach for building HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 141 (2017): 182-193. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., et al. “Data-driven fault detection for industrial processes based on stacked autoencoder and feature learning.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 59.30 (2020): 13471-13483.

- Sun, X., et al. “Dynamic principal component analysis for process monitoring and fault diagnosis: A review.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 58.34 (2019): 15506-15519.

- MacGregor, J.F., & Kourti, T. “Statistical process control of multivariate processes.” Control Engineering Practice 3.3 (1995): 403-414. [CrossRef]

- He, S., et al. “Nonlinear process monitoring based on kernel principal component analysis.” Chemical Engineering Science 56.2 (2001): 579-590.

- Kano, M., & Nakagawa, Y. “Data-based process monitoring, process control, and quality improvement: Recent developments and applications in chemical process industries.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 45 (2012): 104-116. [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, V. “A review of process fault detection and diagnosis: Part II: Qualitative models and search strategies.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 27.3 (2003): 313-326. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S. Joe. “Data-driven fault detection and process monitoring for complex chemical processes.” AIChE Journal 67.6 (2021): e17211. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Li, Q., & Zhou, J. “A review of artificial intelligence methods for data-driven fault detection and diagnosis in building HVAC systems.” Energy and Buildings 246 (2021): 111073. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., et al. “A novel data-driven method for building fault detection and diagnosis using improved principal component analysis and random forest.” Energy and Buildings 208 (2020): 109624. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., et al. “Fault detection and diagnosis for building air handling units using supervised machine learning and expert rules.” Applied Energy 254 (2019): 113673. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., et al. “A review of data-driven methods for HVAC system fault detection and diagnosis.” Energy and Buildings 212 (2020): 109807. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Leo H., et al. “Fault detection and diagnosis in industrial systems.” Springer, 2017.

- Yan, C., O’Brien, W., & Gunay, B. “A comprehensive review of monitoring-based commissioning: Recurrent faults, energy impacts, and future research needs.” Energy and Buildings 186 (2019): 84-100. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Operating Range | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| Supply air duct humidity | [13.4,73.2] | -0.280 |

| Supply air duct flow rate | [4912,11687] | -0.167 |

| Fan frequency | [34.8,50] | -0.181 |

| Workshop air flow rate | [57.5,22268] | -0.146 |

| Mixing room temperature | [18.8,26.7] | 1 |

| Mixing room humidity | [21,68.1] | -0.191 |

| Weighing room temperature | [18.8,25.7] | 0.831 |

| Weighing room humidity | [22.1,71.9] | -0.108 |

| Preprocessing room temperature | [19,26.4] | 0.900 |

| Preprocessing room humidity | [21.8,70.6] | -0.280 |

| Operating Parameter | Variance Contribution Rate | Cumulative Contribution Rate |

| Mixing room temperature | 0.4986 | 0.4986 |

| Preprocessing room temperature | 0.2584 | 0.757 |

| Weighing room temperature | 0.1601 | 0.9171 |

| Supply air duct humidity | 0.0368 | 0.9536 |

| Mixing room humidity | 0.0204 | 0.974 |

| Fan frequency | 0.0110 | 0.984 |

| Supply air duct flow rate | 0.0081 | 0.9921 |

| Preprocessing room humidity | 0.0029 | 0.995 |

| Workshop air flow rate | 0.0030 | 0.998 |

| Weighing room humidity | 0.0020 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).