Introduction

Chitosan is a natural polysaccharide derived from the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects, known for being non-toxic, biodegradable, and biocompatible. These properties have led to its widespread use in medicine, particularly as a hemostatic agent[

1] due to its ability to rapidly initiate clot formation. Although rare, chitosan has been shown to provoke a potent immune response in certain contexts, and isolated cases of allergic or inflammatory reactions have been reported [2, 3].

In obstetrics, Chitosan-tamponade are used as intrauterine tamponades to manage postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) [

4], particularly when standard conservative measures are insufficient or to avoid further escalation[

5]. The product is applied vaginally, where it exerts local hemostatic control within the uterine cavity [

6]. Despite its established safety profile, a new cluster of cases suggests that in rare instances, systemic immune-mediated complications may occur after intrauterine Chitosan exposure.

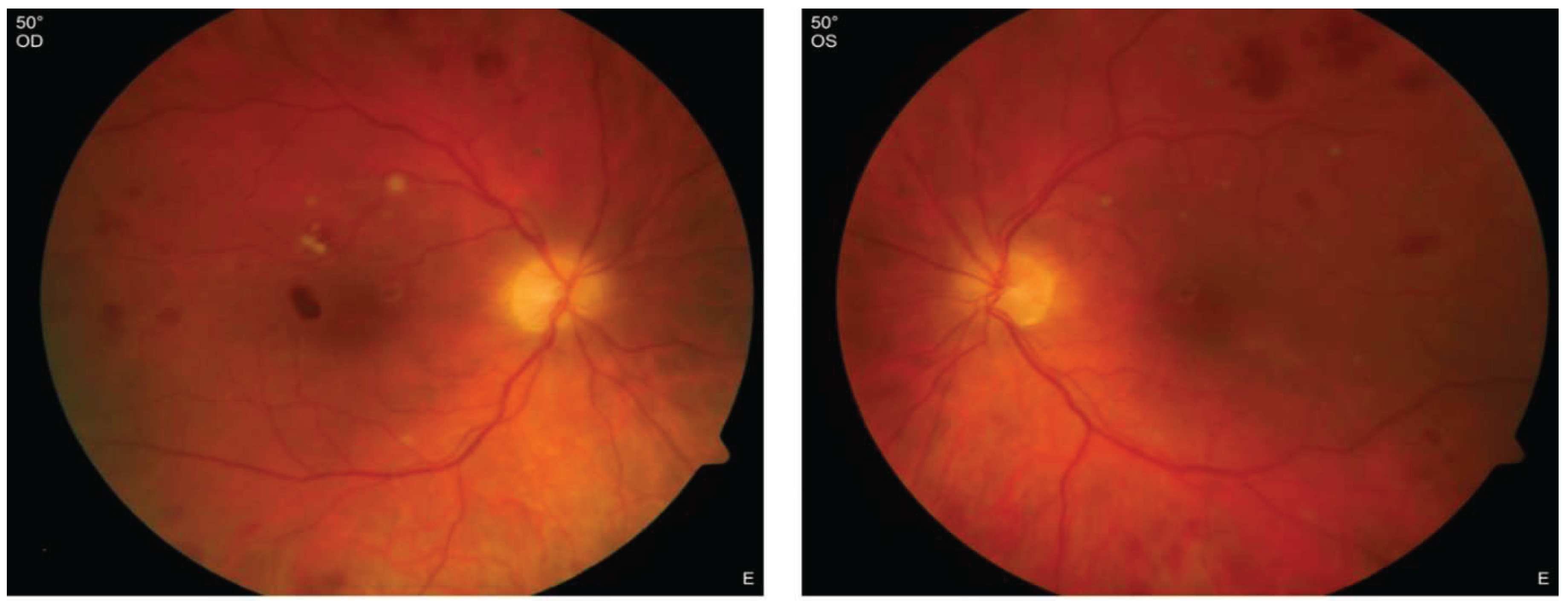

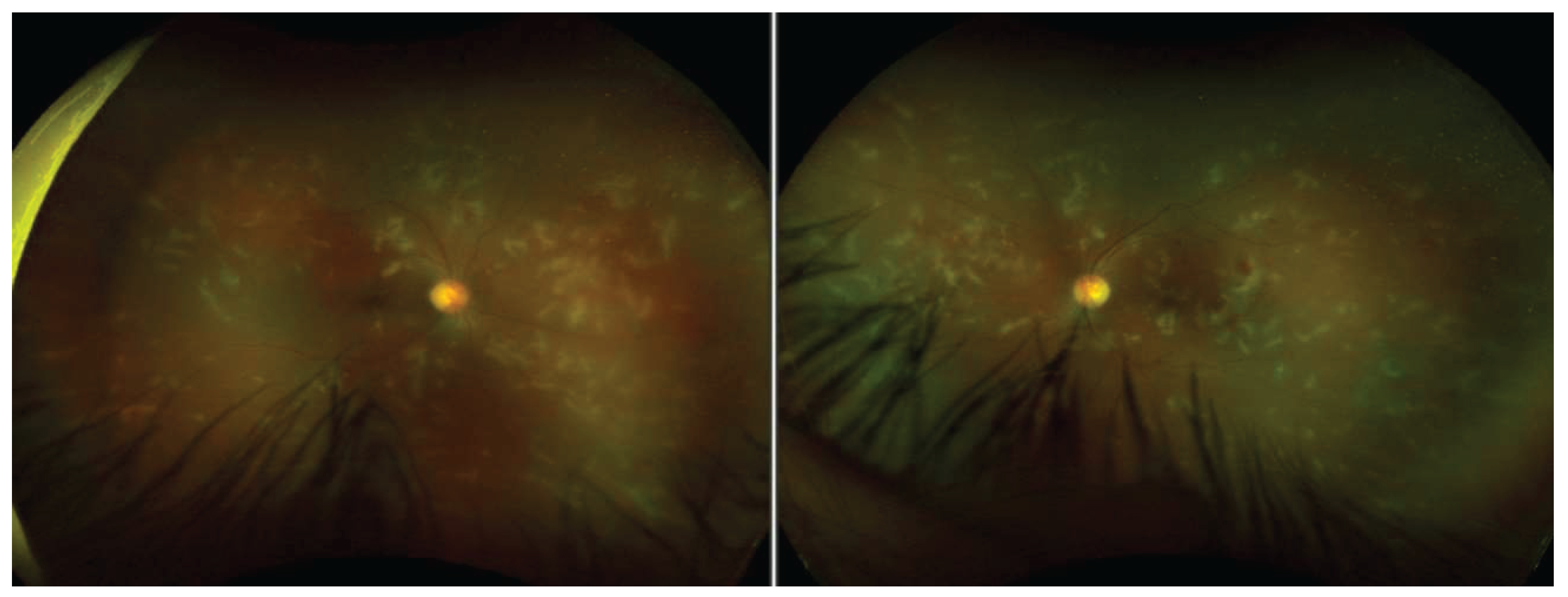

In late 2024, we reported a series of patients who developed acute bilateral uveitis, retinal vasculitis, and vestibulocochlear dysfunction shortly after cesarean delivery managed with Chitosan-tamponade. [

7] Initially, due to the combination of ocular and audiovestibular symptoms, the clinical picture was interpreted as suggestive of Cogan’s syndrome. However, the classical hallmarks [

8]—especially interstitial keratitis and progressive cochlear deterioration — were largely absent.

This interpretation was constructively challenged in a scholarly exchange with the ophthalmology department of a German academic center, whose team had concurrently observed a similar constellation of symptoms in their own patients. In their experience, women undergoing gynecological surgery with substantial blood loss—also managed with Chitosan-tamponade—developed fulminant intraocular inflammation, panuveitis, retinal vasculitis, papilledema, and transient hearing loss. Like our cases, these patients lacked interstitial keratitis, and none progressed to long-term cochlear dysfunction. This was a key distinction from typical Cogan’s syndrome type I, which is defined by progressive sensorineural hearing loss and interstitial keratitis as a sine qua non for diagnosis. [

9]

This academic center additionally initiated a survey among international uveitis experts in late 2023, which did not yield further reports of similar observations, reinforcing the hypothesis that this syndrome may be specific to a particular patient population or surgical setting. Notably, although chitosan is used extensively in trauma and military medicine, no analogous neurosensory syndromes have been reported to date.

Given the clinical overlap yet key differences from Cogan's syndrome, we now suspect that we are observing a distinct immune-mediated syndrome, temporally associated with intrauterine chitosan exposure and characterized by acute vasculitic inflammation affecting the retina and inner ear. In contrast to Cogan’s syndrome, this newly observed entity appears to be self-limiting, responsive to systemic steroids, and not associated with long-term neurosensory deficits. Nonetheless, the severity of acute symptoms and the potential for irreversible damage demand heightened clinical awareness.

We propose the designation CAVES (Chitosan-Associated Vasculitis with Eye and Sensorineural symptoms) to describe this condition. This name underscores both the suspected immunological trigger and its characteristic organ involvement.

In the following section, we present clinical findings of the affected patients. These patients share striking clinical and procedural similarities, further supporting the existence of a recognizable clinical entity and underscoring the need for further investigation.

Case Series

All patients experienced blurred vision within the first two days postoperatively. Two out of three patients subsequently developed hearing loss and vertigo, accompanied by auricular pain, within 1–2 days. The third patient, who received systemic corticosteroid treatment immediately after her initial presentation, did not exhibit any auditory symptoms. Notably, before the administration of corticosteroids, the two affected patients demonstrated a rapidly evolving clinical presentation.

Full clinical details and comprehensive case presentations are available in our previous publication. [

7]

The clinical manifestations observed in our patients included:

Patients reported headaches, blurred and poor vision, tearing, floaters, and a central scotoma in both eyes; hearing impairment, tinnitus, sore auricle, and vertigo

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was significantly reduced and fluctuating: down to 0,05-0.4

Anterior Segment:

mildly swollen eyelids and injected conjunctiva

corneal infiltrates (only one patient)

anterior chamber cells at 2–3+ and miosis, later fibrin reaction and posterior synechiae s at 2-3+ and miosis, later fibrin reaction and posterior synechiae

Posterior Segment:

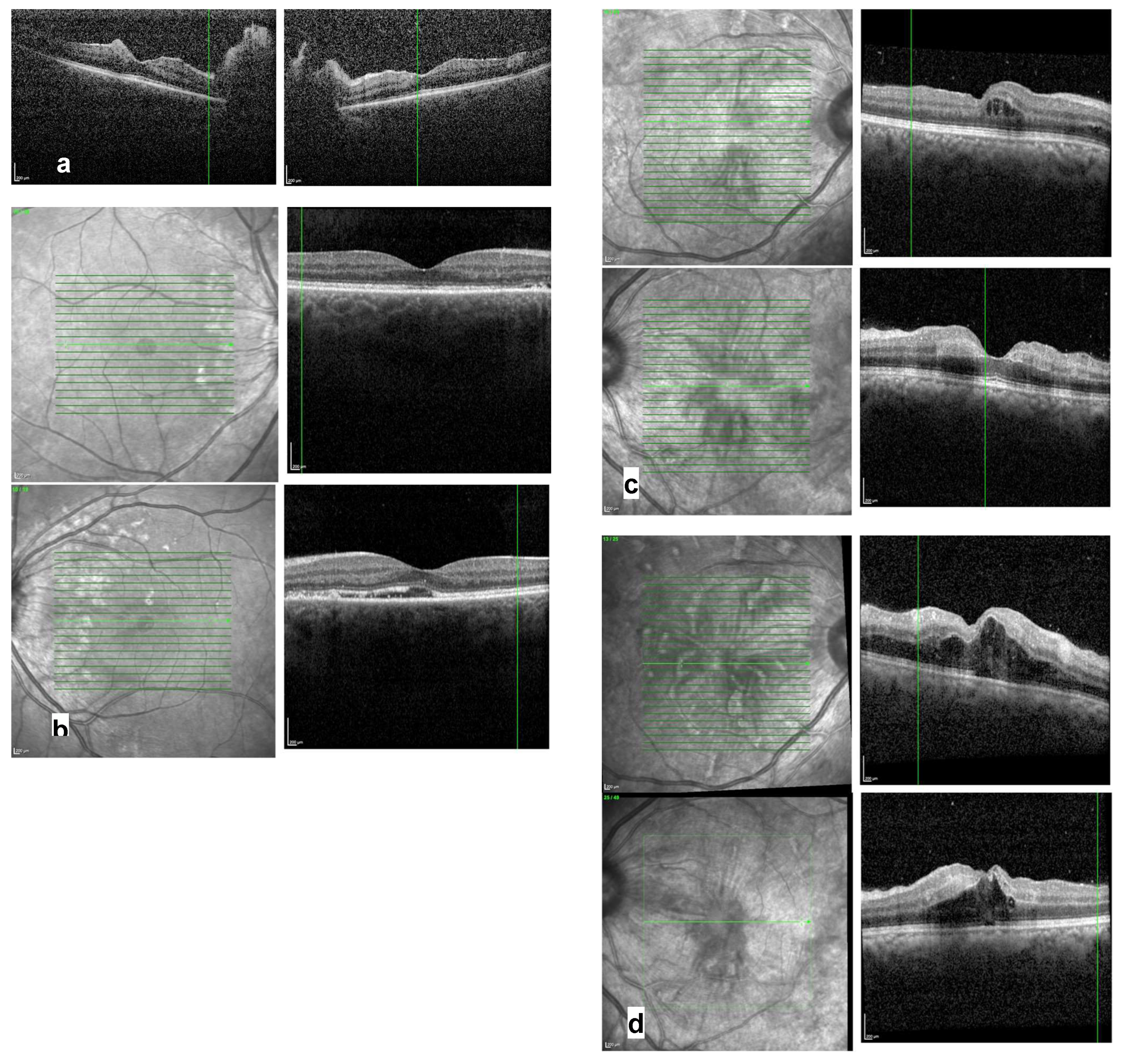

Optical coherence tomography (OCT):

prominent optic disc and hyperreflective lesions within the inner layers, indicative of retinal bleeding (see

Figure 3a)

subretinal fluid and a slightly irregular photoreceptor layer (see

Figure 3b)

irregularities in the inner layers and mild thickening of the parafoveolar retina (see

Figure 3c) intraretinal fluid (see

Figure 3d)

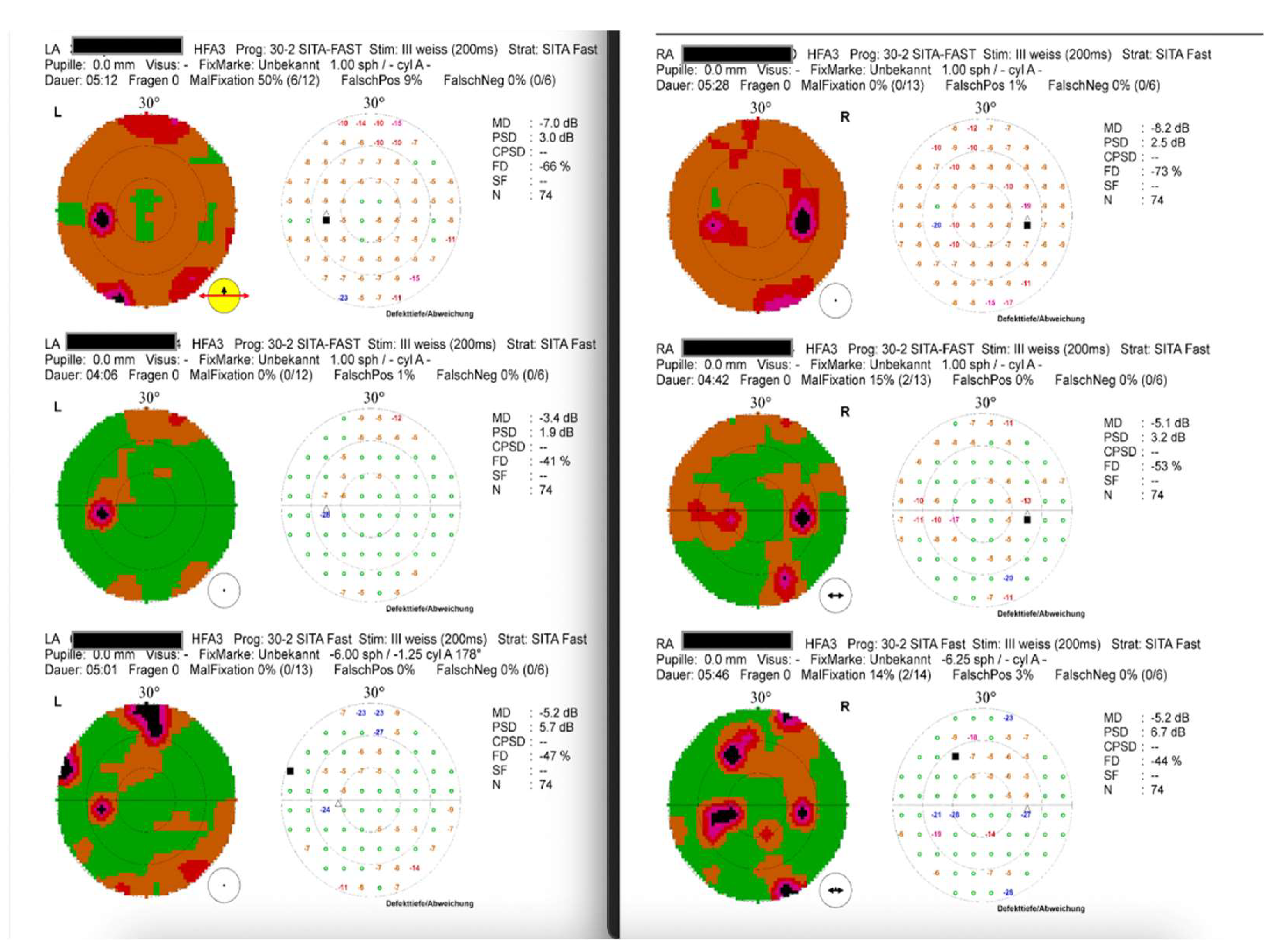

Visual Field (static perimetry 30-2): general reduction of sensitivity and paracentral scotomata (see

Figure 4a); later at follow-up, recovery of general sensitivity, but persisting scotomata (see

Figure 4)

ENT-Examination:

tenderness, swelling, and redness of the ear concha, without involvement of the earlobe and tympanic membrane

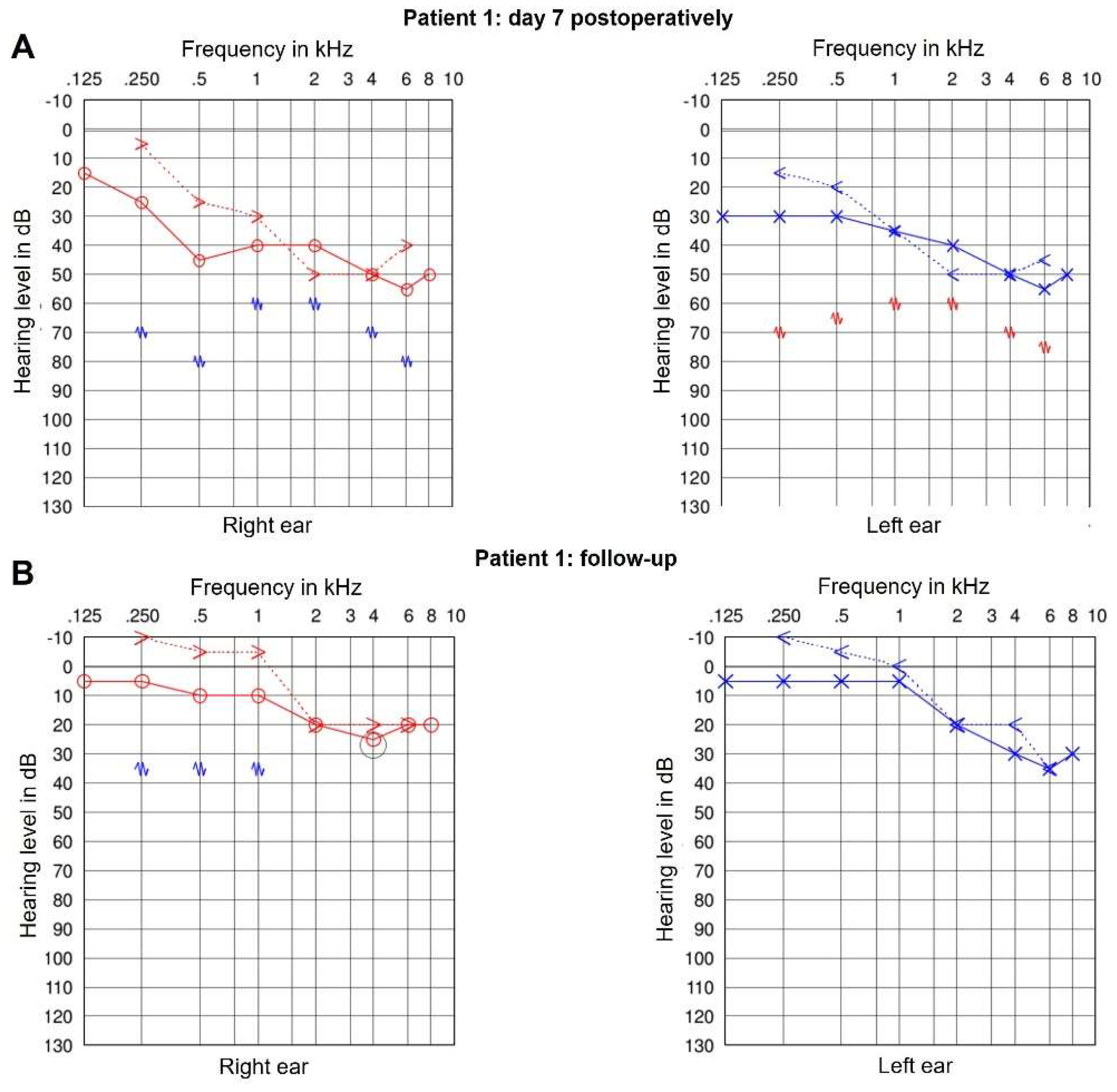

Audiometry:

moderate to severe pantonal/sensorineural hearing loss (see

Figure 5)

Treatment:

All our patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids, receiving 100–250 mg of prednisolone daily, followed by oral administration with gradual tapering. Two patients who developed anterior segment inflammation additionally received topical and periocular steroids, as well as cycloplegics.

Notably, the patient who received systemic steroids immediately did not develop hearing impairment and exhibited the mildest clinical presentation.

One patient in our case series showed disease progression despite systemic therapy and began to recover only after the removal of the Chitosan-tamponade, which had remained in place for an extended period.

Follow Up:

The most recent follow-up examinations for our three patients occurred at 4.5, 4, and 1 year after the initial diagnosis, respectively. All patients experienced either complete or near-complete recovery of vision. Additionally, hearing improved in all cases, although one patient continued to experience tinnitus.

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) returned to normal or was only minimally reduced (0.8–1.0). Ophthalmologic examination revealed minor pigment deposits on the lens surface and mild optic disc pallor, while both the anterior and posterior segments were otherwise unremarkable. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrated only mild residual irregularities in the middle or outer retinal layers. Static perimetry revealed persistent paracentral scotomas (

Figure 4c).

ENT evaluations were unremarkable. Audiometric testing indicated improved inner ear function; however, high-frequency hearing loss persisted above 1 kHz (

Figure 5b).

Characterisation of CAVES

CAVES is a newly identified, immune-mediated inflammatory syndrome occurring in the immediate postoperative period following intrauterine application of chitosan-based hemostatic agents. The syndrome typically manifests within 1 to 3 days after cesarean delivery in the context of significant intraoperative hemorrhage managed with Chitosan-tamponade. For a short summary of symptoms and findings (see

Table 1).

The ocular symptoms are among the earliest and most consistent findings. Patients report blurred or decreased vision, often accompanied by tearing, eye redness, and the perception of floaters. Ophthalmologic examination typically reveals signs of panuveitis, retinal vasculitis, and intraretinal fluid, with occasional presence of subretinal fluid. Visual field testing may demonstrate paracentral scotomata, and in rare cases, keratitis has also been observed, although its role within the syndrome remains unclear.

Auditory and vestibular symptoms usually emerge within a similar timeframe, either concurrently with or shortly after ocular complaints. These include bilateral ear pain (otalgia), sensorineural hearing impairment, tinnitus, and vertigo, pointing to inner ear involvement. ENT evaluation often confirms sensorineural, pantonal hearing loss and, in some cases, auricular perichondritis.

this characteristic constellation—acute bilateral ocular inflammation with retinal involvement, combined with rapidly progressive vestibulo-auditory dysfunction in the absence of systemic autoimmune disease—defines CAVES as a distinct clinical entity. The syndrome shows a favorable response to systemic corticosteroid therapy and does not appear to follow a progressive course, with most patients experiencing resolution of acute symptoms and only minimal residual deficits.

Differentiation from Other Syndromes

When considering the differential diagnosis for the discussed cases, it is essential to distinguish the observed symptoms from other known syndromes. Initially diagnosed as Cogan's syndrome, our understanding evolved as we noted distinct differences and similarities (see

Table 2).

Discussion

We initially described three clinical cases involving young women in their late 20s to early 30s who presented within days after cesarean sections complicated by significant intraoperative bleeding managed with Chitosan-tamponade. All three patients reported visual symptoms—most commonly blurred vision or floaters—within the first 48 hours postoperatively. Two developed sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and auricular pain within days, while the third, who received systemic corticosteroids early, remained free of auditory symptoms. Strikingly, the progression of symptoms in the two untreated patients was rapid, with daily changes in both ocular and auditory findings before steroid therapy was initiated.

These cases initially raised the possibility of Cogan’s syndrome (CS), given the overlapping audiovestibular and ocular inflammation. However, critical features were inconsistent with this diagnosis. Notably, most of the patients didn´t exhibited interstitial keratitis—a sine qua non for CS diagnosis—and none developed progressive hearing loss, which is characteristic of classic CS. Moreover, retinal vasculitis, paracentral scotomas, and auricular perichondritis, all observed in our patients, are not typical of Cogan’s syndrome.

Further differentiation from Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome [10, 11] and Susac’s syndrome [

12]is warranted. VKH typically presents with bilateral granulomatous panuveitis and serous retinal detachments, accompanied by neurological and cutaneous manifestations, such as vitiligo and meningism’s—none of which were observed in our cohort. Susac’s syndrome includes encephalopathy and branch retinal artery occlusions (BRAO) with characteristic Gass plaques, neither of which were identified.

Initially, the differential diagnosis in our index case included Purtscher-like retinopathy [

13], given the temporal proximity to obstetric trauma and hypotensive events. However, the subsequent development of uveitis and auditory symptoms, alongside the lack of characteristic Purtscher findings such as cotton-wool spots or retinal whitening, made this diagnosis unlikely. A presumed contact lens–associated keratitis was also briefly considered in the presence of corneal findings.

The consistent clinical pattern emerging across multiple patients—blurred vision, panuveitis, retinal vasculitis, bilateral sensorineural symptoms, and a temporal association with Chitosan-tamponade use—suggests a novel immune-mediated response. Our hypothesis was reinforced by the clinical course of one of our patient, who improved shortly after removal of the Chitosan-tamponade and initiation of corticosteroids. Furthermore, none of the patients exhibited progressive disease. Symptoms resolved with anti-inflammatory treatment, and residual deficits were limited to static perimetric changes without functional deterioration.

Following the publication of our initial case series, additional reports from another medical center surfaced. These involved patients undergoing gynecologic surgery who similarly developed acute, fulminant intraocular inflammation including panuveitis, papilledema, macular edema, and occlusive vasculitis, as well as transient vestibulocochlear symptoms. Notably, none of these patients developed interstitial keratitis, further supporting the idea that this syndrome is not a variant of Cogan’s disease but rather a separate clinical entity. [

9]

We therefore propose the term CAVES to describe this syndrome. This designation reflects both the likely immunologic trigger and the characteristic organ involvement. While causality cannot be definitively established, the reproducibility, temporal pattern, and clinical similarity across patients support a possible causal relationship, although further mechanistic studies are required.

Other considerations include the nature of chitosan as a biologically active material capable of initiating robust immune responses. While chitosan is widely regarded as biocompatible and safe, particularly in trauma and military applications, its intrauterine use may pose unique immunologic risks—especially in the highly vascular, hormonally dynamic postpartum uterus. The possibility that systemic dissemination of chitosan or its breakdown products may incite a transient immune vasculitis warrants further investigation.

Shellfish allergy is primarily driven by tropomyosin, with recent studies showing that boiled shrimp extracts provoke stronger allergic responses than raw extracts or recombinant tropomyosin (rTM). In murine models, boiled extract induced the highest IgE and Th2 cytokine levels, correlating with more pronounced intestinal inflammation and sensitization rates. Human skin prick tests and immunoblots confirmed that heat-treated tropomyosin has greater allergenicity, and additional minor allergens such as hemocyanin and glycogen phosphorylase were also identified. [

14]

These findings are relevant to the possible role of chitosan in CAVES syndrome. As a heat-treated, crustacean-derived biopolymer, chitosan may mimic or amplify immune responses similar to shellfish allergens, particularly in sensitized individuals. While none of the CAVES patients reported shellfish allergy, subclinical sensitization or cross-reactivity cannot be excluded and should be explored further.

We acknowledge several limitations. First, the number of reported cases remains small, though likely underdiagnosed due to the transient nature of symptoms and the challenges of performing full ophthalmologic or otologic assessments in acutely ill postpartum patients. Indeed, many were too weak or otherwise unable to undergo detailed evaluations at the time of presentation. Second, the absence of biopsy or histopathologic confirmation limits our ability to define the exact immunopathogenesis. Third, other co-factors such as blood transfusions or underlying coagulation disorders may play a synergistic role.

To address the possibility of underreporting, we have implemented a postoperative screening protocol in our institution for all patients treated with intrauterine Chitosan-tamponade. This includes routine ophthalmologic and audiometric evaluation between postoperative days 3 and 4. We encourage other centers to consider similar measures, especially in cases of significant intraoperative bleeding requiring tamponade.

Finally, it remains uncertain whether the inflammatory reaction is specific to vaginal chitosan tamponade following cesarean section, or if similar risks exist in other gynecologic or even non-gynecologic procedures involving chitosan. The exclusive appearance of this syndrome in postpartum women may also reflect a unique interplay between immune modulation, trauma, and hormonal status in this population.

We have issued a call for similar case reports and are currently preparing an extended case series that includes additional cases from three other hospitals. If you have encountered similar cases, we encourage you to contact us.

Conclusion

CAVES appears to represent a previously unrecognized, self-limiting immune vasculitic syndrome temporally associated with intrauterine chitosan-exposure. While rare, its acute and potentially vision-threatening course demands early recognition and prompt steroid therapy. Further multicenter collaboration is essential to determine incidence, pathogenesis, and risk mitigation strategies.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided individual written informed consent for the use of their clinical data and photographs for publication. Due to the retrospective nature of the analysis and the anonymization of patient data, consultation with an ethics committee was not required under local regulations.

References

- Zhang, K., et al., Layered nanofiber sponge with an improved capacity for promoting blood coagulation and wound healing. Biomaterials, 2019. 204: p. 70-79. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., et al., Anaphylaxis induced by intra-articular injection of chitosan: A case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep, 2022. 10(12): p. e6596. [CrossRef]

- Zaharoff, D.A., et al., Chitosan solution enhances both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to subcutaneous vaccination. Vaccine, 2007. 25(11): p. 2085-94. [CrossRef]

- Dueckelmann, A.M., et al., Uterine packing with chitosan-covered gauze compared to balloon tamponade for managing postpartum hemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2019. 240: p. 151-155. [CrossRef]

- Leichtle, C., et al., Chitosan-covered tamponade for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a registry-based cohort study assessing outcomes and risk factors for treatment failure. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2025. 25(1): p. 120. [CrossRef]

- Carles, G., et al., Uses of chitosan for treating different forms of serious obstetrics hemorrhages. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod, 2017. 46(9): p. 693-695. [CrossRef]

- Mala, N., G. Zweigart, and L.S. Fiedler, Multidisciplinary unravelling Cogan's syndrome post-C-section: insights into diagnosis, treatment and a possible identified new trigger. BMJ Case Rep, 2024. 17(12). [CrossRef]

- Iliescu, D.A., et al., COGAN'S SYNDROME. Rom J Ophthalmol, 2015. 59(1): p. 6-13.

- Pleyer, U.e.a. Commentary 2025. Available from: https://casereports.bmj.com/content/17/12/e261520.responses#commentary.

- Joye, A. and E. Suhler, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2021. 32(6): p. 574-582. [CrossRef]

- Greco, A., et al., Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Autoimmun Rev, 2013. 12(11): p. 1033-8. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S., et al., Susac's Syndrome: An Updated Review. Neuroophthalmology, 2020. 44(6): p. 355-360. [CrossRef]

- Serhan, H.A., et al., Purtscher's and Purtscher-like retinopathy etiology, features, management, and outcomes: A summative systematic review of 168 cases. PLoS One, 2024. 19(9): p. e0306473. [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.S., et al., Shrimp Extract Exacerbates Allergic Immune Responses in Mice: Implications on Clinical Diagnosis of Shellfish Allergy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2024. 66(2): p. 250-259. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).