1. Introduction

The proliferation of online content has underscored the critical need for robust and accurate automated systems to detect offensive language, including hate speech, toxicity, and cyberbullying [

1,

2]. Such systems are vital for maintaining healthy digital ecosystems, protecting users from harm, and enforcing community guidelines. However, offensive language is a complex linguistic phenomenon, often characterized by subtlety, indirectness, irony, and high dependence on socio-cultural context [

3,

4,

5]. These nuances make its detection a formidable challenge, even for state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) [

6].

LLMs, such as GPT-4 [

7], Llama series [

8], and PaLM [

9], have demonstrated remarkable capabilities across a wide range of natural language understanding tasks. Their potential for offensive language detection is significant, given their ability to capture intricate semantic and contextual information. However, finetuning these massive models for specific downstream tasks like offensive language detection can be computationally prohibitive due to the sheer number of parameters involved. This has spurred the development of Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) techniques [

10,

11,

12].

Among PEFT methods, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

13] has emerged as a particularly effective and popular approach. LoRA injects trainable low-rank matrices into the layers of a pretrained LLM, freezing the original weights. This drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters while often achieving performance comparable to full finetuning. LoRA has been successfully applied to various tasks, including instruction following [

8] and domain adaptation.

Despite its successes, standard LoRA possesses inherent limitations when faced with highly nuanced tasks like detecting subtle offensive language. Firstly, LoRA typically employs a fixed, predetermined rank for its decomposition matrices across all targeted layers and for all inputs. This static allocation may not be optimal, as different layers or different types of input instances might benefit from varying degrees of adaptation [

14]. Some offensive expressions might be overt and require minimal adjustment from the base LLM, while others, like microaggressions or sarcastic abuse, might necessitate more substantial, fine-grained parameter shifts. Secondly, the LoRA update matrices are inherently dense. This means all parameters within the low-rank projection are updated, potentially leading to an inefficient use of the limited parameter budget when only a sparse subset of features truly needs adjustment for a specific nuance.

To address these limitations, we propose Dynamic Sparse LoRA (DS-LoRA), an innovative extension to LoRA tailored for capturing the subtle nuances of offensive language. DS-LoRA introduces two key enhancements:(i) We incorporate lightweight, learnable gating mechanisms that dynamically scale the contribution of each LoRA module based on the input instance. This allows the model to “decide" how much each LoRA adaptation should influence the output for a given piece of text, effectively focusing (ii) We apply L1 regularization to the LoRA matrices during training. This encourages sparsity within the low-rank update matrices themselves, compelling the model to learn which specific low-rank components are crucial for the task and pruning away redundant ones. By combining dynamic gating with parameter-level sparsity, DS-LoRA aims to create a more adaptive, parsimonious, and ultimately more effective finetuning strategy. This approach enables the LLM to make highly selective and targeted adjustments, better attuned to the specific characteristics of the input text, which is crucial for distinguishing subtle offensive content from benign statements. We evaluate DS-LoRA by finetuning the recently two LLMs on established benchmark datasets for offensive language detection. The experimental results demonstrate that DS-LoRA significantly outperforms standard LoRA and other strong baselines. Our contributions are threefold:

We propose DS-LoRA, a novel PEFT method that integrates dynamic gating and learned sparsity into the LoRA framework, specifically designed for nuanced NLP tasks.

We demonstrate through extensive experiments that DS-LoRA significantly outperforms standard LoRA and other competitive baselines in detecting offensive language, especially in challenging cases involving subtlety and context-dependency, while maintaining or improving parameter efficiency.

We provide an analysis of the learned gate behaviors and sparsity patterns, offering insights into how DS-LoRA achieves its performance gains and contributing to a better understanding of adaptive finetuning mechanisms.

2. Related Work

The automatic detection of offensive language has been a focal point of NLP research for over a decade, driven by the need to moderate online content and mitigate online harm [

15]. Early approaches often relied on lexicon-based methods and traditional machine learning models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Logistic Regression, coupled with engineered features like TF-IDF, n-grams, and sentiment scores [

16]. While these methods provided initial successes, they often struggled with the implicit and context-dependent nature of offensive language, lacking the capacity to capture deeper semantic understanding. The advent of deep learning brought significant advancements, with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

17], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) like LSTMs and GRUs [

18], and attention-based models [

19] demonstrating improved performance by learning hierarchical feature representations directly from text. More recently, pretrained transformer-based models such as BERT [

20], RoBERTa [

21], and their derivatives have set new benchmarks in offensive language detection by leveraging large-scale unsupervised pretraining to learn rich contextual embeddings [

22,

23]. Despite their power, finetuning these models for specific tasks still presents challenges, particularly in adapting them to the nuances of offensiveness without catastrophic forgetting or requiring extensive labeled data for every subtle variation.

The emergence of LLMs with tens to hundreds of billions of parameters has further revolutionized the field, but their sheer size makes full finetuning impractical for most applications [

24]. This has led to a surge in research on Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) techniques, which aim to adapt LLMs to downstream tasks by training only a small fraction of their parameters. Prominent PEFT methods include adapter tuning [

11,

25], which inserts small, trainable adapter modules between the layers of a frozen pretrained model; prompt tuning [

11,

26], which learns soft prompts (continuous embeddings) prepended to the input; and prefix-tuning [

12], which prepends trainable prefix vectors to the keys and values in attention layers. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [

27], central to our work, posits that the change in weights during adaptation has a low intrinsic rank and thus can be represented by low-rank decomposition matrices. This significantly reduces trainable parameters while achieving strong performance. Building upon LoRA, several variants have been proposed, such as LoRA-FA [

27] which freezes matrix A and only trains B, QLoRA [

28] which quantizes the pretrained model and uses LoRA for finetuning, and AdaLoRA [

14] which adaptively allocates the rank budget among weight matrices based on their importance scores. However, these methods typically maintain dense LoRA matrices and often employ static configurations for rank or adaptation strategy, potentially overlooking the benefits of instance-specific dynamic adjustments and explicit parameter-level sparsity for tackling nuanced tasks. Our DS-LoRA method directly addresses these aspects by integrating dynamic input-dependent gating and promoting sparsity within the LoRA updates.

3. Methodology

In this section, we first briefly review the standard Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique. We then introduce our proposed Dynamic Sparse LoRA (DS-LoRA), detailing its core components: input-dependent gating and LoRA parameter sparsification. Finally, we describe the overall model architecture and training procedure.

3.1. Preliminaries: LoRA

LLMs typically consist of multiple layers, with matrix multiplications being a core operation (e.g., in attention mechanisms and feed-forward networks). Full finetuning of an LLM involves updating all its weights

. LoRA [?] hypothesizes that the change in weights during adaptation,

, has a low intrinsic rank. Therefore, LoRA freezes the pretrained weights

and injects a trainable rank decomposition module representing

. Specifically, for a given layer, the update

is approximated by two smaller matrices,

and

, where

is the rank of the adaptation. The forward pass of a LoRA-adapted layer becomes:

where

is the input,

is the output, and

s is a scaling factor, often set to

, where

is a hyperparameter. Only

A and

B are trained, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters. Matrix

A is typically initialized with a random Gaussian distribution, and

B is initialized to zero, so

is zero at the beginning of training, ensuring that the adaptation starts from the pretrained model’s state.

3.2. DS-LoRA

Our proposed DS-LoRA enhances standard LoRA by introducing two key mechanisms: (1) an input-dependent gating mechanism to dynamically control the influence of each LoRA module, and (2) L1 regularization to promote sparsity within the LoRA matrices A and B.

3.2.1. Input-Dependent Gating Mechanism

To allow the model to adapt its LoRA contributions based on the specific input instance, we introduce a learnable gating mechanism for each LoRA module. Given an input x to a LoRA-adapted layer, a small gate controller network computes a scalar gate value . This gate value then modulates the output of the LoRA path.

The gate controller

is implemented as a small Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). For an input

(which is the input to the original linear transformation

), the gate value is computed as:

or, in a simpler form without a hidden layer if

is set to 0:

where

(or just

) are learnable parameters of the gate controller, and

is the sigmoid function, ensuring the gate value is bounded between 0 and 1. We detach

x before feeding it to

(

) to prevent the gate’s gradients from directly influencing the representation

x being processed by the main LoRA path, simplifying learning dynamics. The gate parameters are trained jointly with the LoRA matrices.

The modified forward pass with the gating mechanism is:

This allows the LoRA update to be scaled down (when

) for inputs where the pretrained model is already sufficient or the specific LoRA adaptation is not beneficial, and scaled up (when

) when the adaptation is crucial.

3.2.2. LoRA Parameter Sparsification

While LoRA reduces the “number" of parameters, the LoRA matrices

A and

B are typically dense. We hypothesize that for nuanced tasks, only a sparse subset of these low-rank adaptation parameters might be truly necessary. To encourage sparsity in

A and

B, we incorporate an L1 regularization term into the overall training loss. The L1 penalty is defined as:

where the sum is over all LoRA modules

i applied in the model,

denotes the L1 norm (sum of absolute values of the elements), and

is a hyperparameter controlling the strength of the sparsity penalty. This penalty encourages many elements in

and

to become zero during training, leading to a sparser effective

and potentially improving generalization and interpretability by focusing on the most impactful parameter adjustments.

3.2.3. DS-LoRA Layer Forward Pass

The complete forward pass for a DS-LoRA layer combines the original weight computation, the gated LoRA path, and the scaling factor:

All parameters of are frozen. The trainable parameters for each DS-LoRA layer are those in A, B, and its corresponding gate controller .

3.3. Model Architecture and Training

3.3.1. Base Model and DS-LoRA Application

We apply DS-LoRA to the query () and value () projection matrices within the self-attention sub-layers of each Transformer block. These matrices are common targets for LoRA due to their significant role in shaping the attention mechanism’s behavior. The original weights of Llama-3, except for the newly introduced DS-LoRA parameters (LoRA matrices and gate controller parameters), are kept frozen during training. For offensive language detection, we append a linear classification head on top of the LLMs, which takes the hidden state corresponding to the last input token and projects it to the number of target classes (e.g., offensive vs. non-offensive).

3.3.2. Training Objective

The model is trained to minimize a composite loss function

:

is the standard cross-entropy loss for the offensive language classification task:

where

N is the batch size,

C is the number of classes,

is the true label (1 if sample

j belongs to class

c, 0 otherwise), and

is the model’s predicted probability for sample

j belonging to class

c.

is the L1 sparsity regularization term defined in Equation

5.

The hyperparameter balances the contribution of the classification objective and the sparsity constraint.

3.3.3. DS-LoRA Finetuning Algorithm

The overall finetuning process using DS-LoRA is summarized in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 DS-LoRA Finetuning Algorithm |

-

Require:

Pretrained LLM (e.g., Llama-3 8B) -

Require:

Training dataset

-

Require:

LoRA rank r, LoRA alpha , L1 sparsity coefficient

-

Require:

Learning rate , number of epochs E, batch size

-

Require:

Target modules for DS-LoRA (e.g., in attention layers) - 1:

Initialize DS-LoRA parameters: - 2:

for all target linear layers in do

- 3:

Initialize LoRA matrices A (Kaiming uniform) and B (zeros) - 4:

Initialize gate controller parameters (e.g., Xavier uniform) - 5:

Replace with DS-LoRA layer (Eq. 6) - 6:

end for - 7:

Freeze all original parameters in . - 8:

Let be the set of all trainable parameters ( parameters). - 9:

Initialize optimizer (e.g., AdamW) for . - 10:

for epoch = 1 to E do

- 11:

Shuffle

- 12:

for each batch in do

- 13:

Compute model output

- 14:

Compute classification loss

- 15:

Compute L1 sparsity loss (Eq. 5) over all matrices. - 16:

Compute total loss

- 17:

Perform backpropagation:

- 18:

Update using the optimizer. - 19:

end for

- 20:

end for - 21:

return Trained model

|

4. Experimental Setup

This section details the experimental setup used to evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed DS-LoRA for nuanced offensive language detection. We describe the base models, datasets used for training and evaluation, evaluation metrics, baseline methods, and implementation details.

4.1. Base Models

We selected two recent and powerful open-source Large Language Models (LLMs) as base models for our experiments to demonstrate the generalizability of DS-LoRA:

Llama-3 8B Instruct: A decoder-only transformer model from Meta AI with 8 billion parameters. We specifically use the instruction-tuned variant, which has been aligned for better instruction following and safety, providing a strong foundation for downstream task adaptation.

Gemma 7B Instruct: A decoder-only transformer model from Google with 7 billion parameters, also an instruction-tuned variant. Gemma models are built using similar architectures and techniques as Google’s Gemini models. .

For both models, we utilize their official Hugging Face Transformers library [

29] implementations. During finetuning with DS-LoRA or other PEFT methods, the original weights of these base models are kept frozen, and only the adaptation parameters are updated. A linear classification head is added on top of the base model’s last hidden state output to predict the offensive language class.

4.2. Datasets

We conduct experiments on widely recognized public benchmark datasets for offensive language detection, chosen to cover a range of offensive phenomena and annotation schemes:

OLID [

30]: This dataset, from SemEval-2019 Task 6, contains English tweets annotated for three hierarchical levels. We focus on Sub-task A: Offensive language identification (OFF vs. NOT). This task requires identifying whether a tweet contains any form of offensive language, including insults, threats, and profanity. We use the official training, development, and test splits.

HateXplain [

23]: This dataset provides fine-grained annotations for English posts from Twitter and Gab, distinguishing between hate speech, offensive language, and normal language. Crucially, it also includes human-annotated rationales (token-level explanations) for each classification, which, while not directly used for training our classification model, underscores the dataset’s focus on nuanced and explainable offensiveness. We use the three-class classification task (hate, offensive, normal) and also report a binary offensive vs. normal version for comparison.

For all datasets, we adhere to the standard training, validation, and testing splits provided by the dataset creators to ensure fair comparison with prior work. Preprocessing steps include minimal cleaning, such as normalization of user mentions and URLs, and tokenization using the respective base model’s tokenizer.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of our models, we use standard classification metrics:

Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified instances.

Precision: The proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions.

Recall: The proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances.

F1-Score (Macro and Weighted): The harmonic mean of precision and recall. We report both Macro-F1 (unweighted average across classes, crucial for imbalanced datasets) and Weighted-F1 (average weighted by class support). For binary tasks, we specifically focus on the F1-score for the “offensive" or “hate speech" class when it’s the minority and primary target.

Given that offensive language is often a minority class, F1-score (especially Macro-F1 or F1 for the positive class) and Recall for the offensive class are particularly important indicators of a model’s practical utility.

4.4. Baselines

We compare DS-LoRA against several strong baselines and existing PEFT methods:

Zero-Shot LLM: The base Llama-3 8B and Gemma 7B models without any finetuning, using carefully crafted prompts to perform offensive language classification in a zero-shot manner.

Full Finetuning: Full finetuning of the base LLMs. Due to computational constraints, this might be limited to finetuning only the top few layers or a smaller version of the model as an indicative upper bound.

LoRA [

13]: The original LoRA implementation applied to the same target modules (

) as DS-LoRA, using various ranks (

r) for comparison.

Adapters [

31]: Finetuning using Houlsby adapters inserted into the Transformer layers.

QLoRA [

28]: If comparing parameter efficiency with quantization, QLoRA provides a strong baseline for memory-efficient finetuning.

For all PEFT methods, including DS-LoRA and standard LoRA, we tune relevant hyperparameters (e.g., rank r, LoRA , learning rate, adapter bottleneck dimension) on the development set of each dataset.

4.5. Implementation Details

For DS-LoRA and standard LoRA, we target the query () and value () projection matrices in the self-attention mechanisms of all Transformer layers. The LoRA rank r is explored in the set . The LoRA scaling factor is typically set to or r. For DS-LoRA, the gate controller is implemented as a two-layer MLP with a hidden dimension of or a simple linear layer if , with ReLU activation in the hidden layer and a sigmoid output. The L1 sparsity regularization coefficient is tuned from the set . We train for a maximum of to 10 epochs, depending on the dataset size, with early stopping based on the validation set’s Macro-F1 score. Batch sizes are chosen based on GPU memory constraints, typically ranging from 4 to 16 per GPU. Experiments are run on 4 NVIDIA A100.

5. Results and Analysis

In this section, we present the empirical results of our proposed DS-LoRA compared against baseline methods on the OLID and HateXplain datasets. We then conduct ablation studies to understand the contribution of DS-LoRA’s key components and provide further analysis into its behavior.

5.1. Main Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the performance of DS-LoRA and baseline methods on the OLID and HateXplain datasets, respectively. We report Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and Macro-F1. All PEFT methods were applied to both Llama-3 8B and Gemma 7B base models.

As

Table 1 and

Table 2, DS-LoRA consistently outperforms all baseline methods across both datasets and for both Llama-3 8B and Gemma 7B base models. On OLID, DS-LoRA (Llama-3 8B) achieves a Macro-F1 of 81.3%, an improvement of 1.2% over standard LoRA. Notably, the F1-score for the "Offensive" class sees a more significant gain of 1.8% (77.7% vs 75.9%), highlighting DS-LoRA’s enhanced ability to correctly identify the target minority class. Similar trends are observed for the Gemma 7B model.

The performance gains are even more pronounced on the more challenging HateXplain dataset, which features finer-grained distinctions. For Llama-3 8B, DS-LoRA achieves a Macro-F1 of 72.0%, surpassing standard LoRA by 1.8%. The F1-scores for both “Hate" (66.5% vs 64.0%) and “Offensive" (70.1% vs 67.5%) classes show substantial improvements It suggests that the dynamic gating and sparsity mechanisms in DS-LoRA are particularly beneficial for capturing the subtle cues that differentiate these categories. These results indicate that DS-LoRA’s adaptive nature allows it to make more precise adjustments to the base LLM, which is crucial for nuanced classification tasks. The number of trainable parameters for DS-LoRA is only marginally higher than standard LoRA (due to the small gate controller) but remains significantly lower than partial full finetuning or standard adapter approaches with larger bottleneck dimensions.

5.2. Ablation Studies

To understand the individual contributions of the key components of DS-LoRA: input-dependent gating (Gate) and L1 sparsity regularization (L1), we conduct ablation studies on the OLID dataset using Llama-3 8B as the base model. The results are presented in

Table 3.

The ablation results in

Table 3 clearly demonstrate that both the input-dependent gating mechanism and L1 sparsity regularization contribute positively to DS-LoRA’s performance. Adding only the gating mechanism to standard LoRA (‘LoRA + Gate‘) improves the F1(Offensive) score by 1.2% and Macro-F1 by 0.8%. This suggests that dynamically scaling LoRA module contributions based on input characteristics is highly beneficial. Similarly, incorporating only L1 sparsity (‘LoRA + L1 Sparsity‘) provides a modest improvement, indicating that encouraging sparser LoRA update matrices helps in refining the adaptation. The full DS-LoRA model, combining both components, achieves the best performance, underscoring the synergistic effect of dynamic gating and learned sparsity.

5.3. Analysis of DS-LoRA Components

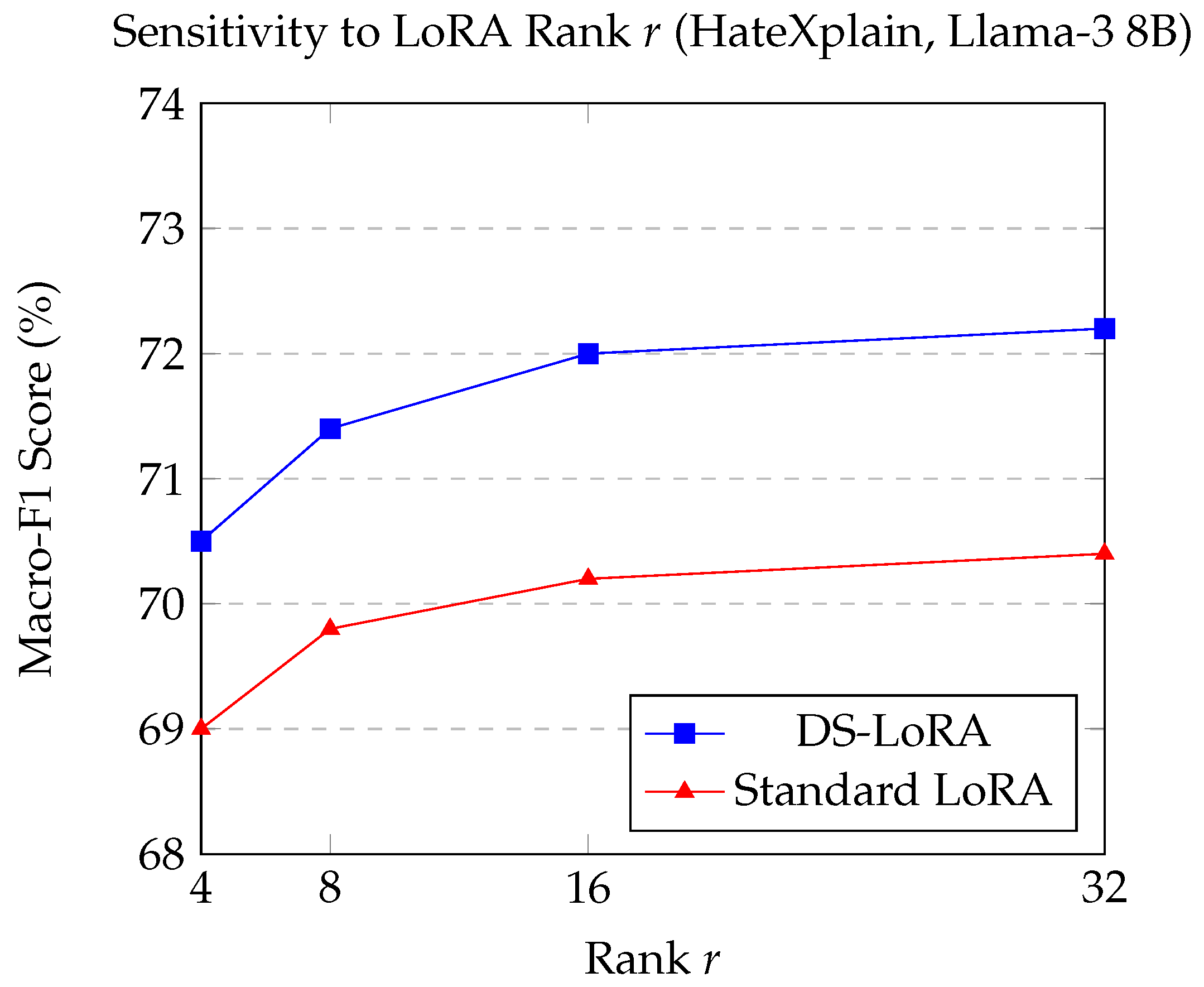

5.3.1. Sensitivity to LoRA Rank r

We investigate the performance of DS-LoRA and standard LoRA across different LoRA ranks (

) on the HateXplain dataset (Macro-F1) using Llama-3 8B.

Figure 1 illustrates the results.

Figure 1 shows that DS-LoRA consistently outperforms standard LoRA across all tested ranks. Both methods generally improve with increasing rank, but DS-LoRA exhibits a stronger performance curve and its advantage over standard LoRA is maintained. This suggests that even with a larger adaptation capacity (higher

r), the dynamic gating and sparsity of DS-LoRA enable more effective utilization of that capacity. Interestingly, DS-LoRA with

already surpasses standard LoRA with

, indicating potential for achieving comparable or better results with fewer parameters in some configurations.

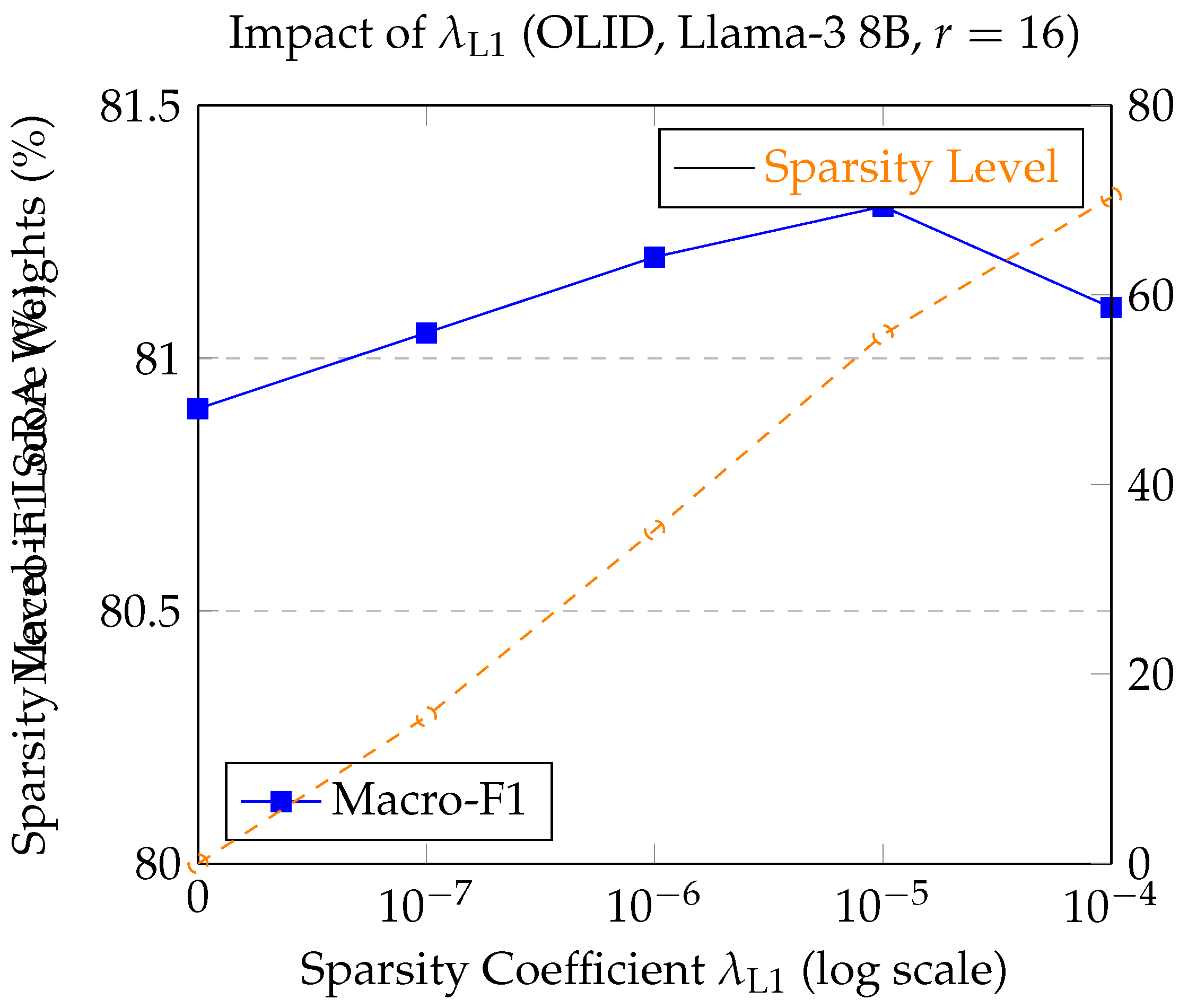

5.3.2. Impact of Sparsity Coefficient

We analyze the effect of the L1 sparsity coefficient on DS-LoRA’s performance (Macro-F1, OLID, Llama-3 8B, ) and the resulting sparsity level in LoRA matrices (percentage of zero-valued weights in A and B).

Figure 2 illustrates that increasing

generally leads to higher sparsity in the LoRA

A and

B matrices. Performance (Macro-F1) initially improves with moderate sparsity, peaking around

, which achieves over 50% sparsity in LoRA weights while delivering the best F1 score. This suggests that a significant portion of parameters in standard dense LoRA might be redundant or even detrimental for this nuanced task. However, excessively high

(e.g.,

) can lead to over-sparsification and a slight degradation in performance, indicating a trade-off between parsimony and model capacity. The optimal

effectively prunes less important LoRA parameters, allowing the model to focus on the most discriminative low-rank updates.

5.3.3. Qualitative Analysis of Gate Activations

To further investigate the behavior of the dynamic gating mechanism, we analyzed the average gate activation values (

) for DS-LoRA modules across different layer groups of the Llama-3 8B model, conditioned on the ground-truth input category from the HateXplain dataset.

Table 4 presents these average activations, including the standard deviation to indicate variance.

Several key observations emerge from

Table 4. Firstly, across all layer groups, inputs categorized as “Normal" consistently exhibit the lowest average gate activations (e.g., overall model average of

), suggesting that DS-LoRA appropriately reduces the LoRA module contributions when the base model’s pretrained knowledge is likely sufficient. This conserves parameter updates for benign inputs. Secondly, inputs identified as “Hate Speech" trigger significantly higher average gate activations (overall model average of

), particularly in the middle layers (average of

). This indicates that the model learns to engage the LoRA adaptations more strongly when encountering highly offensive content that requires specialized adjustments from the base model’s representations. Inputs classified as “Offensive (Non-Hate)" generally show gate activations between those for “Normal" and “Hate Speech" categories.

The higher engagement in middle layers for ’Hate Speech’ is particularly noteworthy. These layers in LLMs are often associated with capturing more complex semantic relationships and abstract features. The increased LoRA activity here might suggest that DS-LoRA is making crucial fine-grained adjustments in these intermediate representations to better distinguish severe forms of offensive language from merely offensive or benign content. This layer-specific and category-specific dynamic modulation of LoRA pathways supports our hypothesis that the gating mechanism enables a more targeted and efficient use of the adaptation parameters, contributing to the improved performance on nuanced distinctions.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we introduced DS-LoRA, an enhanced parameter-efficient finetuning method incorporating input-dependent gating and L1 sparsity regularization to improve nuanced offensive language detection in LLMs. Our experiments on the OLID and HateXplain datasets demonstrated that DS-LoRA significantly outperforms standard LoRA and other baselines, particularly in discerning subtle offensive nuances, while maintaining comparable parameter efficiency. Ablation studies and analyses of gate activations and learned sparsity confirmed the efficacy of DS-LoRA’s components in enabling more targeted and adaptive model adjustments. We believe DS-LoRA offers a valuable advancement for finetuning LLMs on complex, context-sensitive tasks, and future work will explore its broader applicability and further refinements to its adaptive mechanisms.

References

- Fortuna, P.; Nunes, S. A survey on automatic detection of hate speech in text. Acm Computing Surveys (Csur) 2018, 51, 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, R.T.; Naicker, N.; Olugbara, O.O. Detecting hate speech on twitter network using ensemble machine learning. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T.; Warmsley, D.; Macy, M.; Weber, I. Automated hate speech detection and the problem of offensive language. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, 2017, Vol. 11, pp. 512–515.

- Van Bruwaene, D.; Huang, Q.; Inkpen, D. A multi-platform dataset for detecting cyberbullying in social media. Language Resources and Evaluation 2020, 54, 851–874. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhu, S. Cross-lingual offensive speech identification with transfer learning for low-resource languages. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2022, 101, 108005. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xu, S.; Sun, H.; Pan, L.; Cui, M.; Du, J.; Jin, R.; Branco, A.; Xiong, D.; et al. Multilingual Large Language Models: A Systematic Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.11072 2024.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–113.

- He, J.; Zhou, C.; Ma, X.; Berg-Kirkpatrick, T.; Neubig, G. Towards a unified view of parameter-efficient transfer learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.04366 2021.

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021, pp. 3045–3059.

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2021, pp. 4582–4597.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3.

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Bukharin, A.; Karampatziakis, N.; He, P.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, T. Adalora: Adaptive budget allocation for parameter-efficient fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10512 2023.

- Pradhan, R.; Chaturvedi, A.; Tripathi, A.; Sharma, D.K. A review on offensive language detection. Advances in Data and Information Sciences: Proceedings of ICDIS 2019 2020, pp. 433–439.

- Nobata, C.; Tetreault, J.; Thomas, A.; Mehdad, Y.; Chang, Y. Abusive language detection in online user content. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th international conference on world wide web, 2016, pp. 145–153.

- Gambäck, B.; Sikdar, U.K. Using convolutional neural networks to classify hate-speech. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the first workshop on abusive language online, 2017, pp. 85–90.

- Badjatiya, P.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, M.; Varma, V. Deep learning for hate speech detection in tweets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th international conference on World Wide Web companion, 2017, pp. 759–760.

- Pamungkas, E.W.; Patti, V. Cross-domain and cross-lingual abusive language detection: A hybrid approach with deep learning and a multilingual lexicon. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics: Student research workshop, 2019, pp. 363–370.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 2019.

- Caselli, T.; Basile, V.; Mitrović, J.; Granitzer, M. Hatebert: Retraining bert for abusive language detection in english. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.12472 2020.

- Mathew, B.; Saha, P.; Yimam, S.M.; Biemann, C.; Goyal, P.; Mukherjee, A. Hatexplain: A benchmark dataset for explainable hate speech detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 14867–14875.

- Zhu, S.; Pan, L.; Xiong, D. FEDS-ICL: Enhancing translation ability and efficiency of large language model by optimizing demonstration selection. Information Processing & Management 2024, 61, 103825. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, T.; Xue, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Tang, J. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning for Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.13787 2025.

- Xie, T.; Li, T.; Zhu, W.; Han, W.; Zhao, Y. PEDRO: Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning with Prompt DEpenDent Representation MOdification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.17834 2024.

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Shi, S.; Chu, X.; Li, B. Lora-fa: Memory-efficient low-rank adaptation for large language models fine-tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.03303 2023.

- Dettmers, T.; Pagnoni, A.; Holtzman, A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 10088–10115.

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing: system demonstrations, 2020, pp. 38–45.

- Zampieri, M.; Malmasi, S.; Nakov, P.; Rosenthal, S.; Farra, N.; Kumar, R. Predicting the type and target of offensive posts in social media. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.09666 2019.

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 2790–2799.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).