Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To assess the role of optimally sized and placed stationary ESSs (SESSs) in enhancing power system resilience.

- To investigate the optimal utilization of MESSs in providing emergency support during natural disasters.

- To highlight the effectiveness of stationary-mobile-integrated ESSs (SMI-ESSs) for improving resilience.

- To evaluate the impact on resilience by combining the ESSs with complementary characteristics to form hybrid energy storage systems (HESSs).

- To elaborate the correlation between resiliency indices and ESSs.

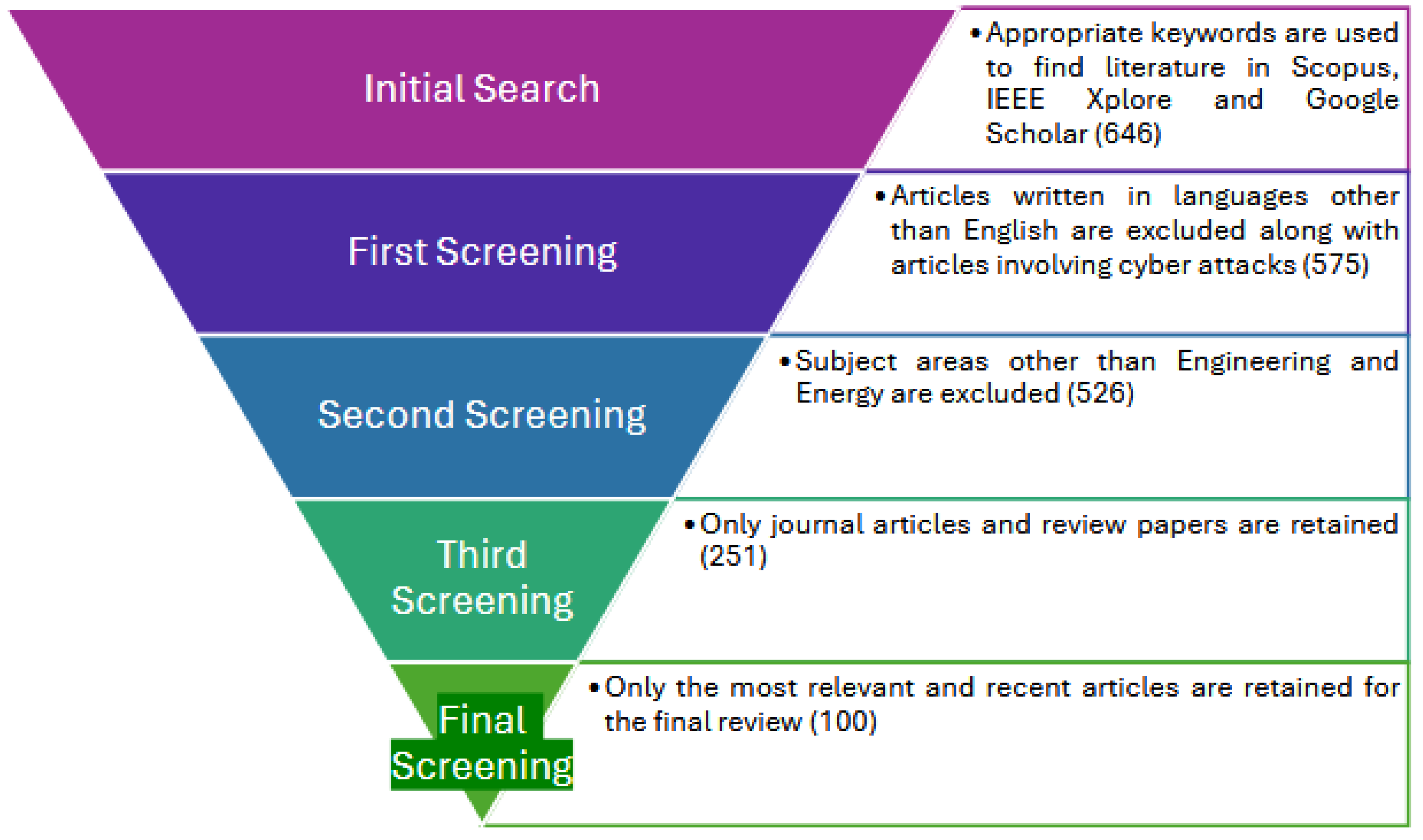

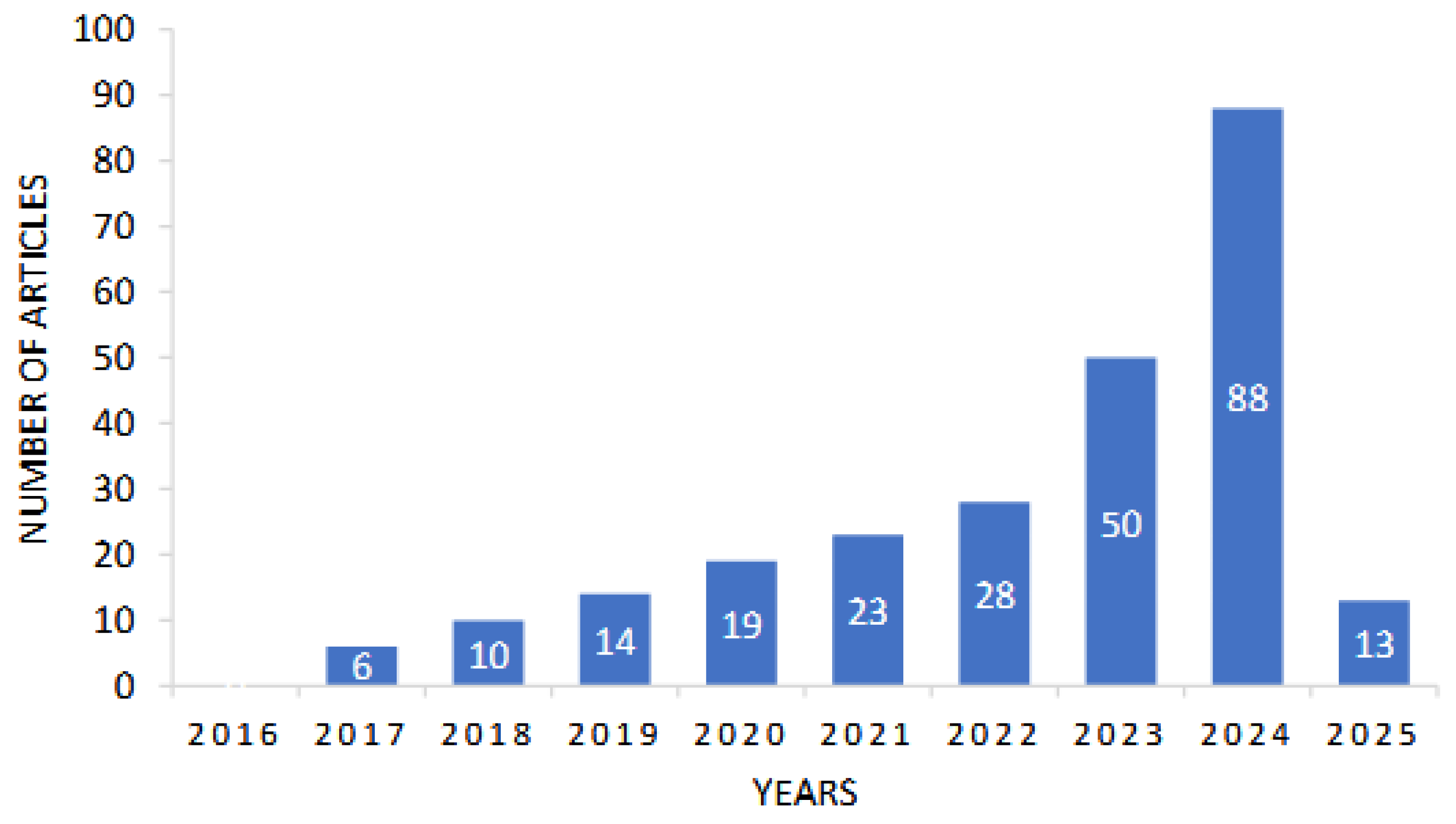

2. Literature Review Methodology

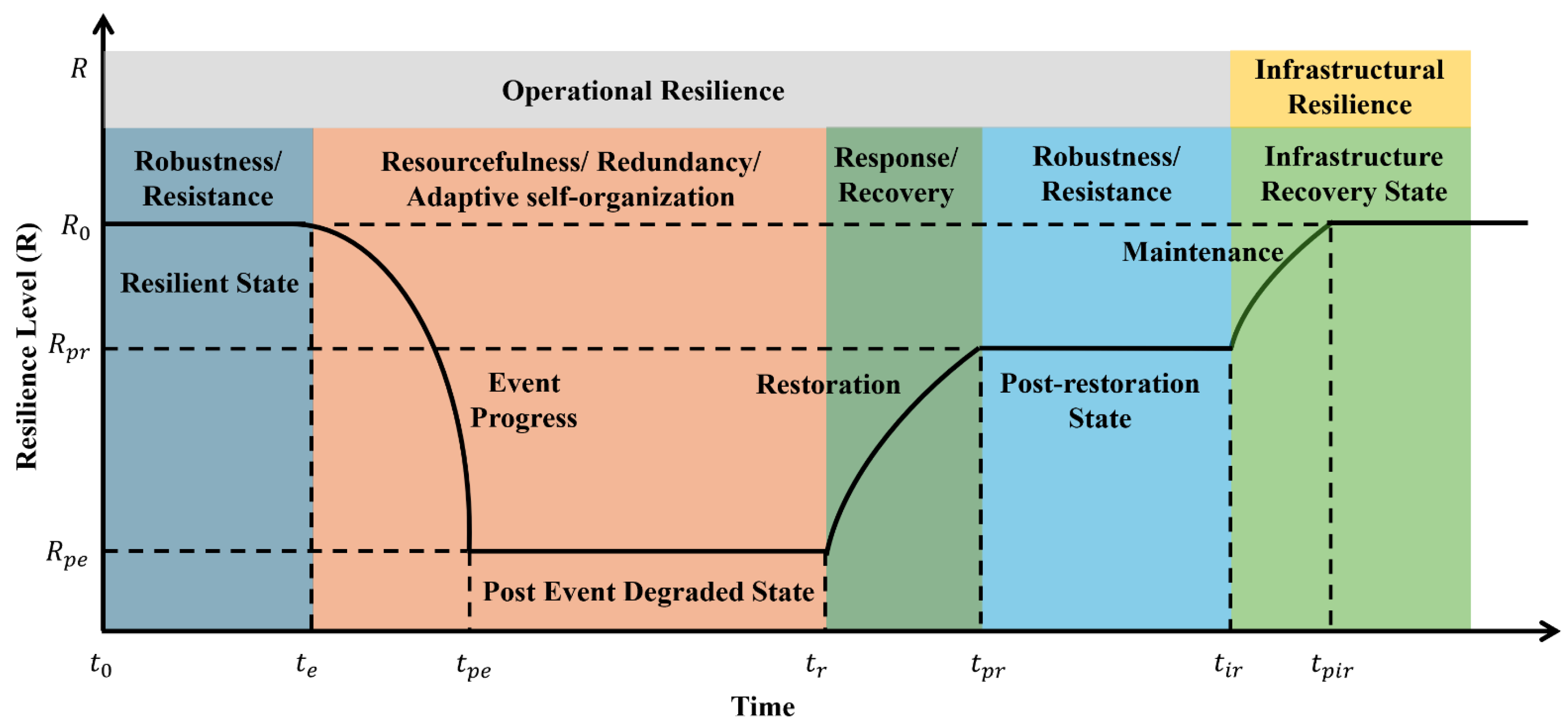

3. Power System Resilience

3.1. Definition and Indices

3.1.1. General Characteristics of Power System Resilience Indices

- Focus on high-impact, low-probability (HILP) events and their consequences, such as loss of load, financial losses, recovery costs, the number of affected individuals, critical load disruptions, and business interruptions;

- Be performance-oriented rather than solely attribute-based;

- Incorporate intrinsic uncertainties influencing response and planning activities;

- Be straightforward, applicable for both retrospective and predictive analysis, and highly consistent;

- Account for the spatial and temporal correlations of natural disasters in their impact on power system resilience ;

- Provide assessments at both the system-wide and component-specific levels.

3.1.2. Reliability-Based Indices

- Metric-K – estimates the expected number of line outages caused by destructive events.

- LOLP (Loss of Load Probability) – quantifies the probability of load loss during extreme conditions.

- EDNS (Expected Demand Not Supplied) – measures the anticipated shortfall in demand due to disruptions.

- Metric-G – evaluates the complexity of grid recovery following an event.

3.1.3. Indices Based on Resilience Features

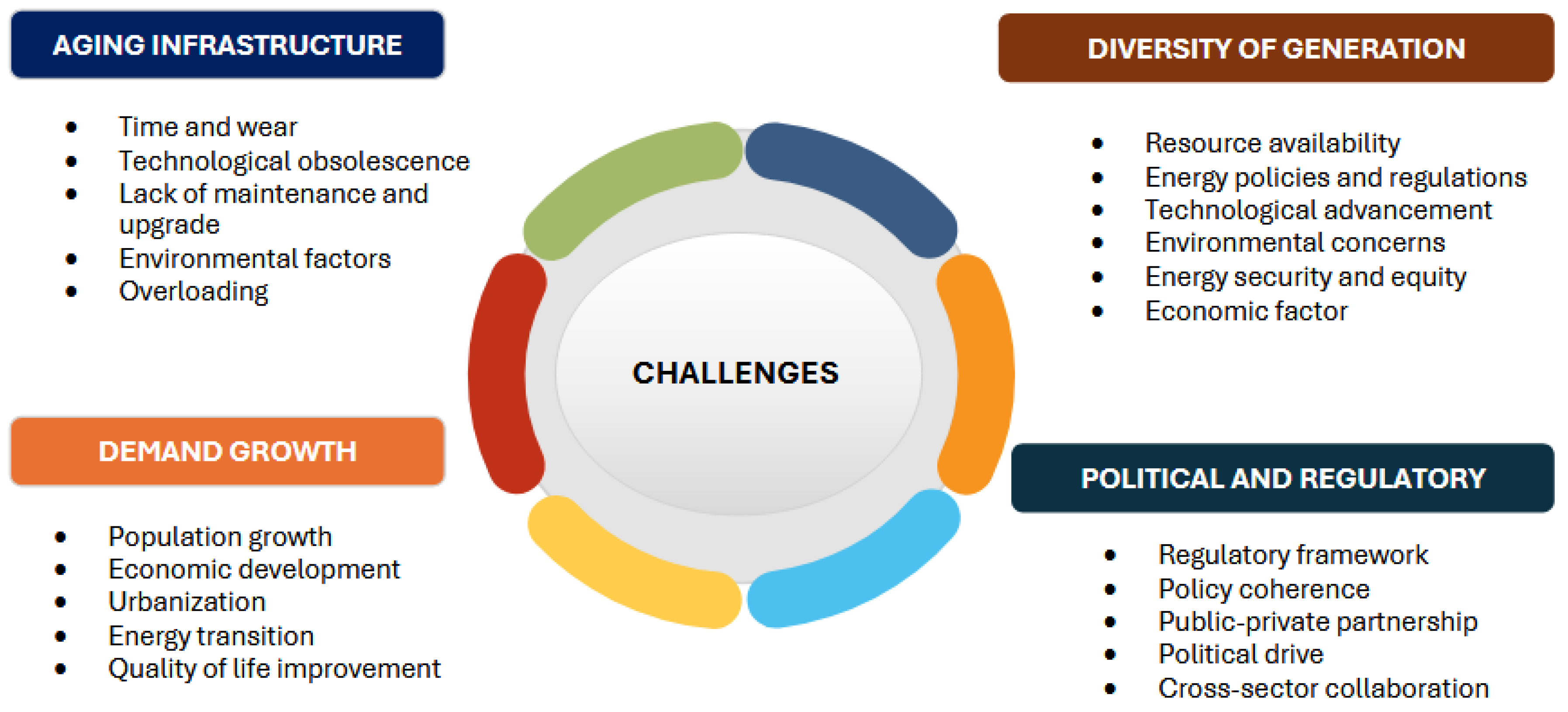

3.2. Challenges Associated with Power System Resilience

3.2.1. Aging Infrastructure

3.2.2. Growing Demand

3.2.3. Diversity of Generation

3.2.4. Political and Regulatory

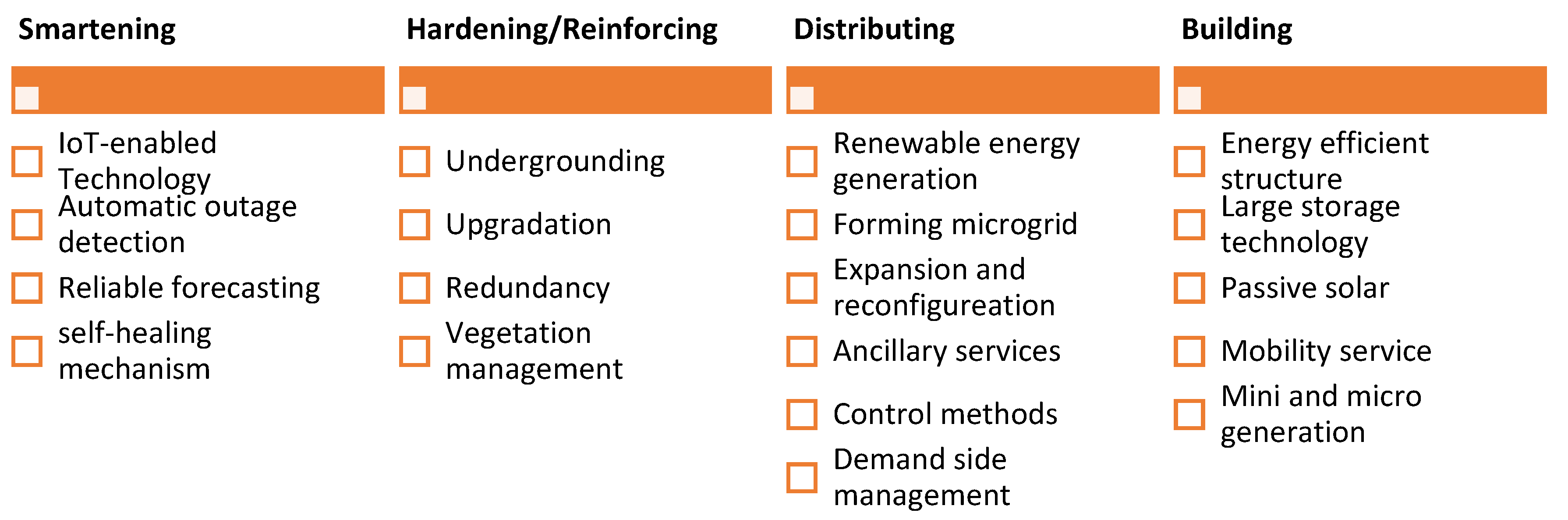

3.3. Measures to Enhance Power System Resilience

3.3.1. Smartening

3.3.2. Hardening/Reinforcing

3.3.3. Distributing

3.3.4. Building

4. Role of Energy Storage Systems in Enhancing Resilience

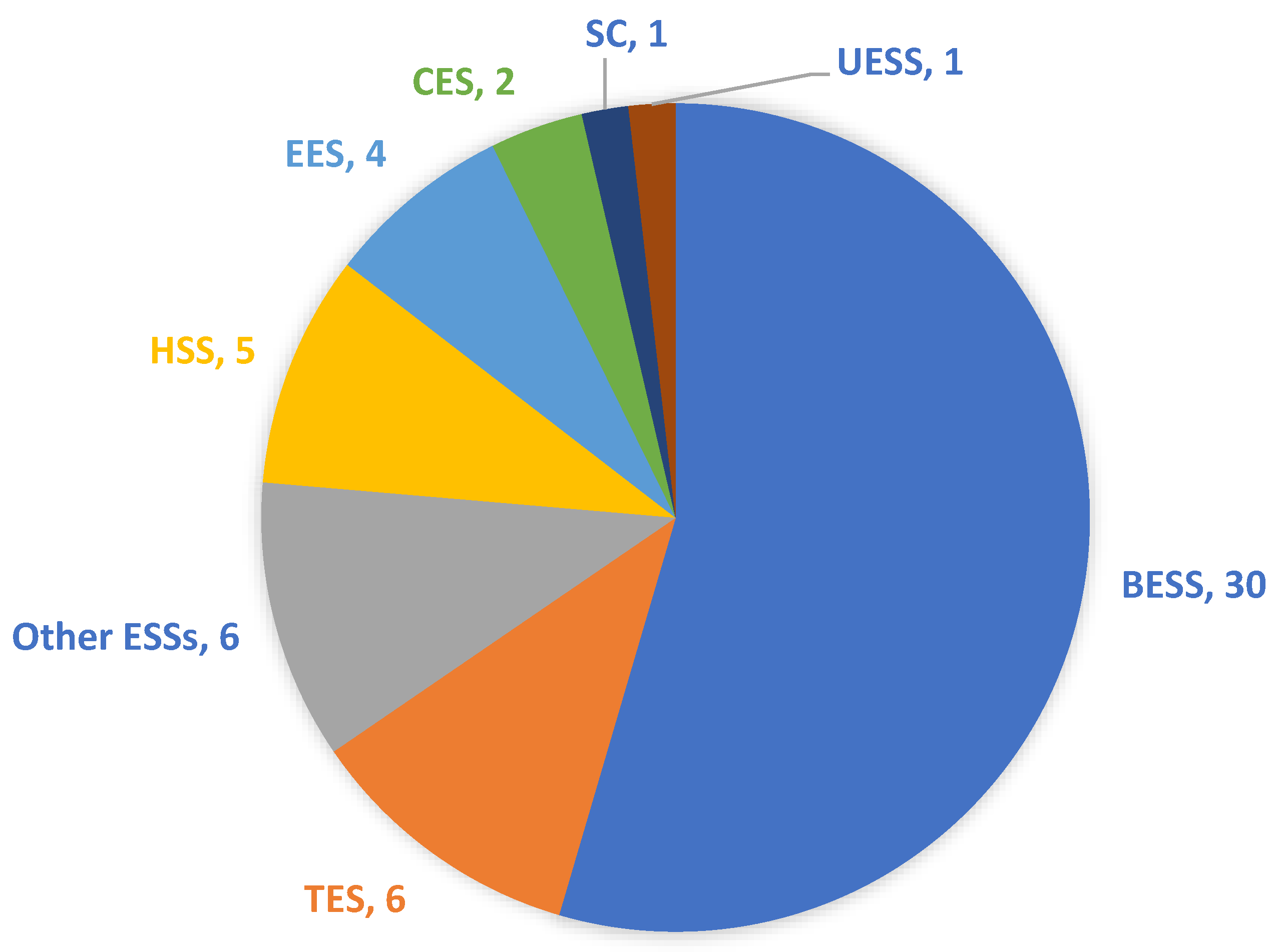

4.1. Role of Stationary Energy Storage Systems (SESSs)

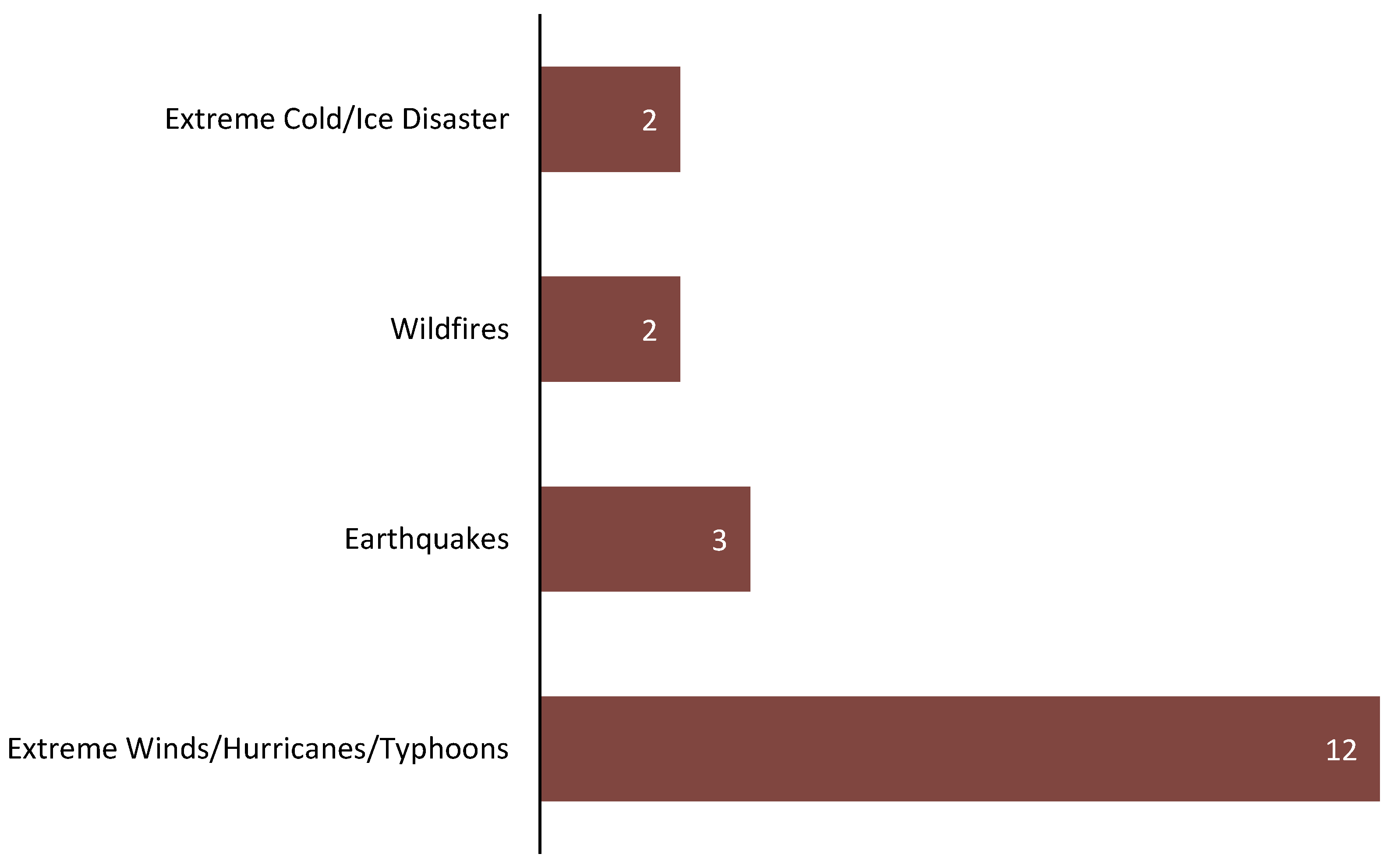

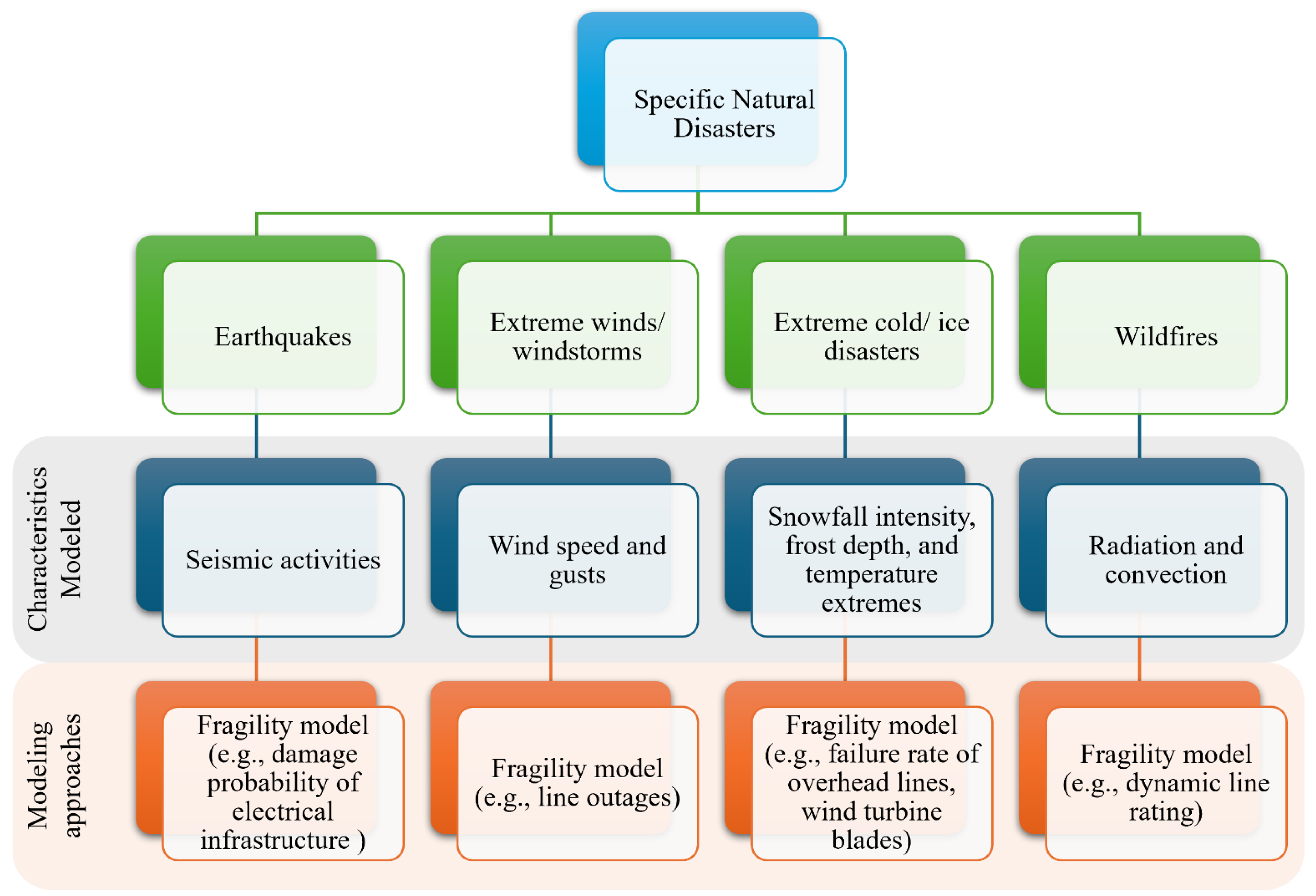

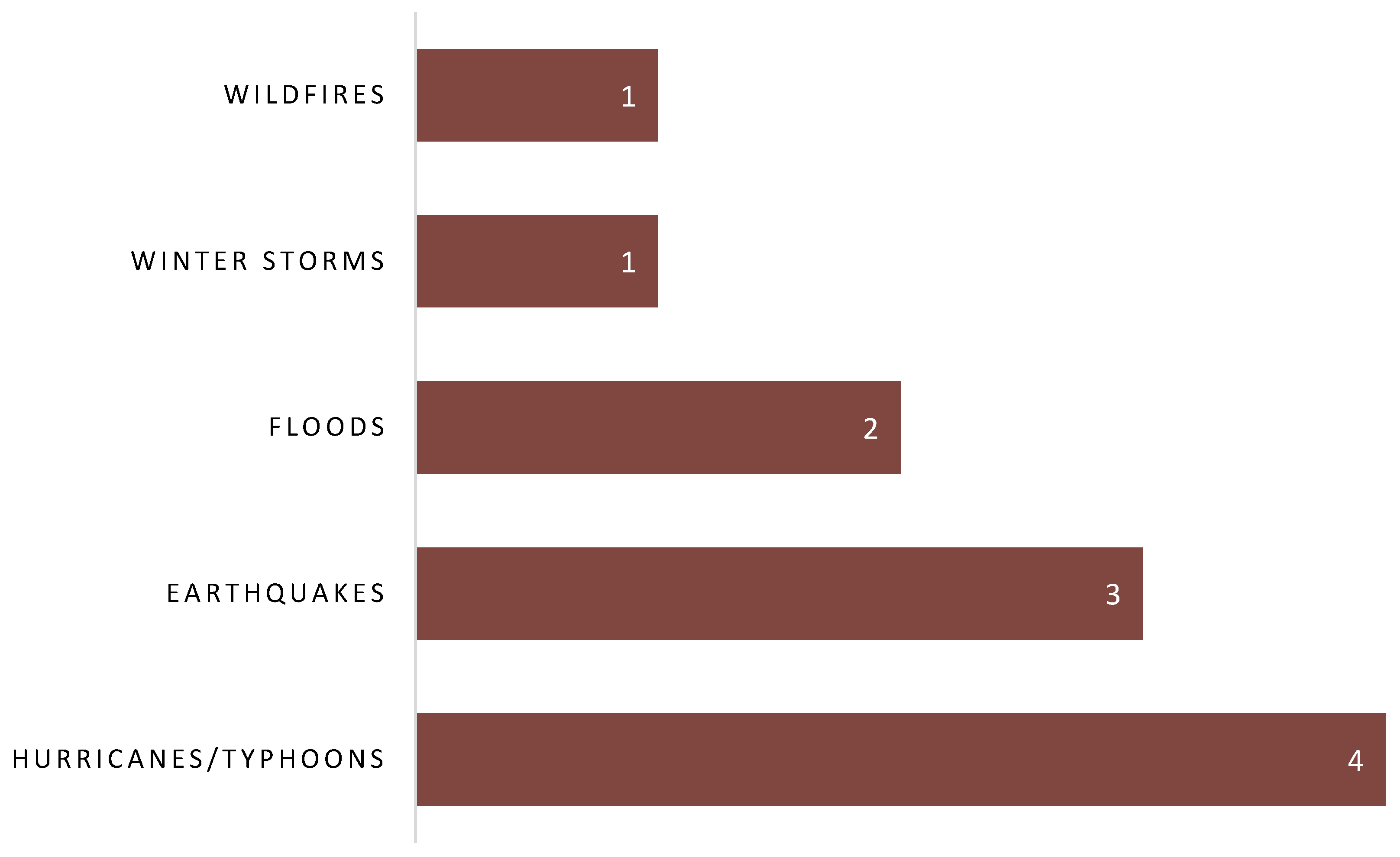

4.1.1. Specific Natural Disasters

4.1.2. Community-Level Solutions

4.1.3. Behind the Meter Energy Storage

4.1.4. Integrated Energy Systems (IESs)

4.1.5. Other Resiliency-Related Applications of SESSs

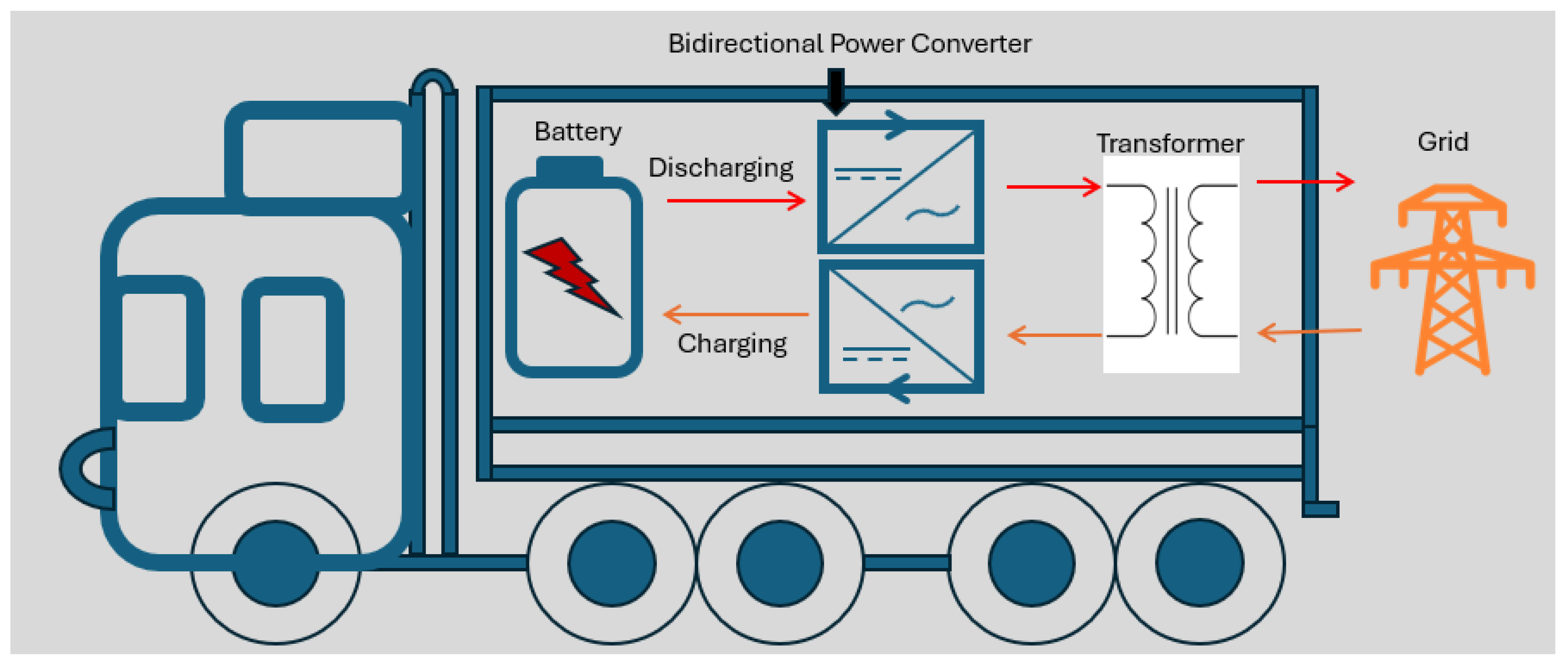

4.2. Role of Mobile Energy Storage Systems (MESSs)

4.2.1. MESSs in Specific Natural Disasters

4.2.2. MESSs in Generalized Extreme Events

4.3. Role of Stationary-Mobile Integrated ESSs (SMI-ESSs)

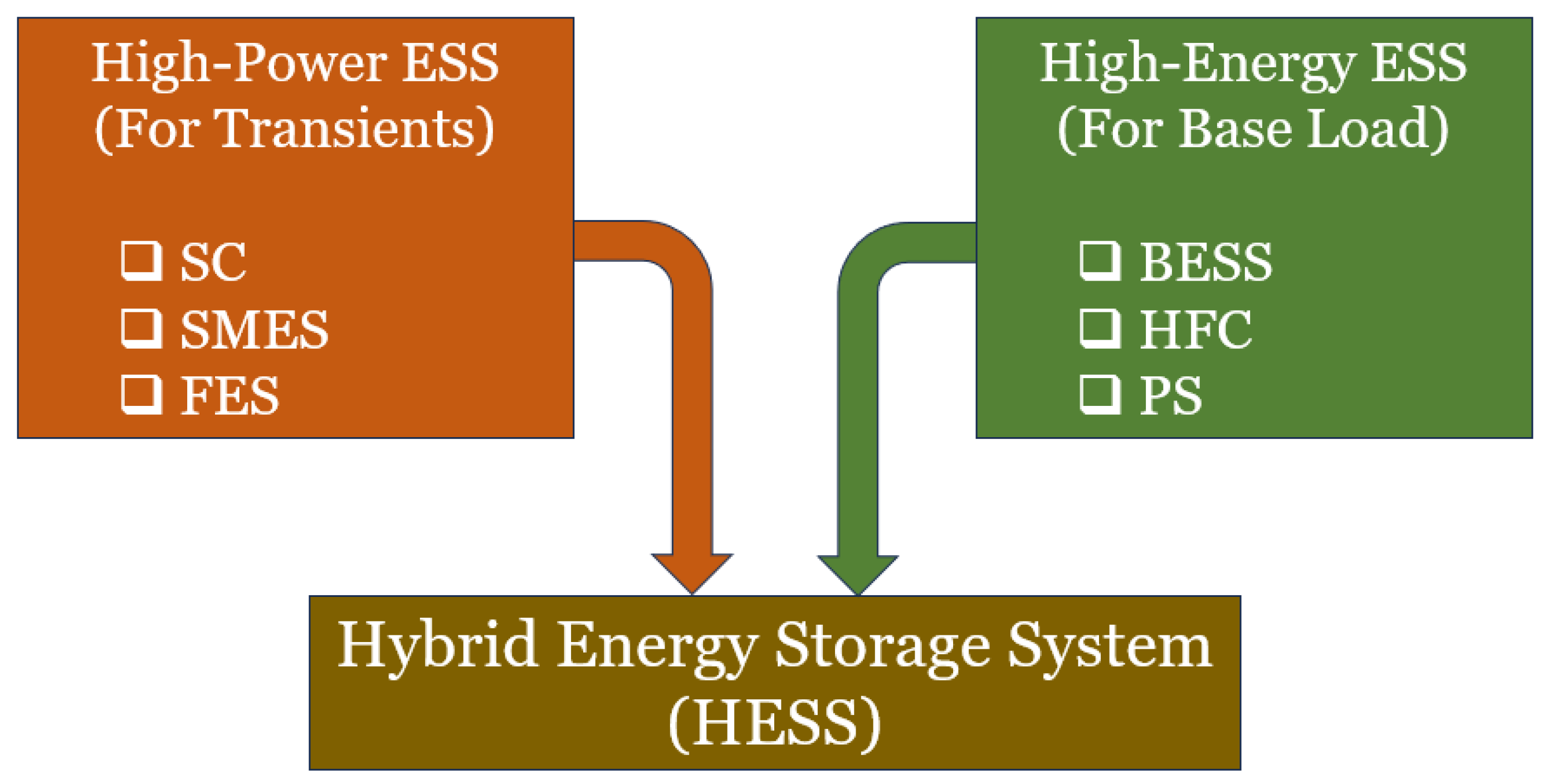

4.4. Role of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems (HESSs)

4.5. Correlation Between Resilience Indices and ESSs

5. Impact of Natural Disasters on ESSs

6. Conclusions

- A combination of system hardening and operational techniques has been shown to be more cost effective and resilient than applying these techniques in isolation.

- Although, underground ESSs (UESSs) are more expensive than above-the-ground ESSs, they become economically justifiable in case of severe extreme events.

- The combined optimization for resilience and economy provides superior results than optimizing resilience and economy in isolation.

- The use of home batteries (i.e., BTM ESS) along with grid side ESSs provides enhanced resilience as compared to the use of grid-side ESSs alone.

- CBES has been shown to be more cost-effective than DBES to enhance resilience against grid outage events for residential customers as it has a higher capacity and can participate in energy arbitrage.

- BESSs combined with run-of-river hydropower plants can enhance power system resilience by enabling localized bottom-up black start, allowing faster restoration of critical loads compared to conventional top-down methods. Rail-based MESSs are well-suited to the resilience enhancement solutions that require a large storage capacity, typically transmission level schemes.

- The adoption of an hourly demand-based variable minimum SOC for ESSs, as opposed to a fixed threshold, has been shown to be more effective in enhancing resilience, albeit with increased costs.

- The public transportation infrastructure is sometimes damaged by extreme events. Therefore, while designing MESSs to enhance resilience, proper consideration must be given to the real-time road condition and traffic congestion for a more accurate design. Moreover, repair crews can provide more economical solution by clearing the road obstacles for MESSs compared to the cases without crews.

- The combined use of MESSs and MEGs proves to be more cost-effective than MESSs, MEGs, or SESSs alone

- Joint resilience enhancement of multi-energy systems has been shown to be more effective than isolated efforts targeting either the power or heat network individually.

- A combination of stationary and mobile ESSs in the form of SMI-ESSs has been shown to be more effective in improving resilience than utilizing only stationary or mobile ESSs.

- The identification of critical loads to adopt flexible load shedding is a useful tool to increase resilience of the critical infrastructure.

- For LIB cells, the internal temperature is linearly related to the external temperature, which is about 1.1 times the external temperature plus 1.61°C. This relationship is independent of battery’s SOC. However, thermal runaway occurs at lower temperatures for higher SOCs in LIBs.

- If a wildfire burns an EV containing LIBs or a home ESS with LIBs, partially damaged battery packs must be carefully identified and managed during recovery efforts, as they can pose a risk of secondary ignition even months after the initial fire.

- Extreme cold has negative impacts on the operation and degradation of LIBs. Improved modeling and performance enhancement approaches have been discussed in the literature.

7. Future Research Directions

- (a)

- The current literature lacks comprehensive research on modeling the combined occurrence of multiple natural disasters and their collective impact on power systems. As an example in this regard, firestorm as a combination of wildfire and windstorm can be mentioned. Future studies should focus on developing robust resilience enhancement strategies that account for such multi-hazard scenarios.

- (b)

- Most of the research works have considered generalized natural disasters for planning resilience enhancement strategies. However, to obtain more practical insights, accurate models of typical natural disasters—encompassing their probability of occurrence, progression, and impact on the power system—must be evaluated.

- (c)

- The impact of extreme winds on the speed of MESSs needs to be modeled with more accuracy to improve the resilience enhancement results.

- (d)

- HESSs can produce improved results than the individual ESSs in terms of improving the resilience of power systems. However, the promising research on HESSs for resilience enhancement calls for the design and evaluation of more comprehensive ESS combinations, particularly HESSs comprising more than two ESS types.

- (e)

- Future research can assess the feasibility of FES and SC as community ESSs.

- (f)

- Instead of relying on fixed efficiency of ESSs, dynamic efficiency can be considered in the future to perform rolling optimization for the deployment of MESSs considering prediction errors regarding extreme events.

- (g)

- The role of MESSs for enhancing resilience is well-evaluated. However, their efficacy and economic feasibility under normal circumstances need to be evaluated in the future research.

- (h)

- The impact of large-scale penetration of EVs as MESSs on the resilience and stability of power systems can be assessed in future research.

- (i)

- SMI-ESSs provide improved resilience when their sizing and placement are optimized in a coordinated manner. However, few research works have been published on this strategy and further research is needed on this relatively new approach for resilience improvement.

- (j)

- The deployment of BESSs using GIS and multi-criteria decision-making process results in superior resilience and cost-effectiveness as compared to the decision-making without GIS and multi-criteria considerations. The deployment of other ESSs using GIS-informed decision-making can be evaluated in future research works.

- (k)

- (l)

- The impact of wildfire on outdoor BESSs needs to be modeled and considered during resiliency planning studies. This involves the calculations of heat transfer from wildfire to the BESSs and generating warning signals for precautionary measures to prevent the BESSs from thermal runaway and ultimately from escalating the wildfires.

- (m)

- The impact of probabilistic weather parameters on the behavior of an ongoing wildfire must be accurately modeled. Based on this, fire fragility models of DN equipment should reliably predict potential damage, leading to the development of a mechanism that suggests dynamic preventive actions for the safety of power equipment and operating staff.

- (n)

- Few studies have discussed the role of ESSs in mitigating the impacts of extreme cold weather on power systems. More research, especially on the role of HESSs and MESSs in improving resilience against extreme cold weather, is suggested.

- (o)

- Along with identification of partially damaged LIBs, global standard operating procedures (SOPs) need to be established for safely removing wildfire-damaged LIBs and EVs containing LIBs from the wildfire-impacted area, as well as for their quarantine period and disposal.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| 2S-ADRO | Two-stage adaptive distributionally robust optimization |

| A-CAES | Adiabatic-Compressed Air Energy Storage |

| ADN | Active Distribution Network |

| ALOL | Avoided Loss of Load |

| AMGs | Active Microgrids |

| B&B | Branch and Bound |

| BEBs | Battery Electric Buses |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| BSS | Battery-Swapping Station |

| BTM | Behind the Meter |

| C&CG | Column-and-Constraint Generation |

| CAES | Compressed Air Energy Storage |

| CBES | Community Battery Energy Storage |

| CES | Cooling Energy Storage |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| CIES | Community Integrated Energy System |

| CVaR | Conditional Value-at-Risk |

| DBES | Distributed Battery Energy Storage |

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| DN | Distribution Network |

| DRHO | Dual Rolling Horizon Optimization |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DRO | Distributionally Robust Optimization |

| DS | Distribution System |

| DSM | Demand Side Management |

| EBs | Electric Buses |

| EDNS | Expected Demand Not Supplied |

| EENS | Expected Energy Not Supplied |

| EES | Electrical Energy Storage |

| EH | Energy Hub |

| ELNS | Expected Load Not Supplied |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| EMT | Electromagnetic Transient |

| ENS | Energy Not Supplied/Served |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| EVPs | Electric Vehicle Parking Lots |

| EVs | Electric Vehicles |

| FES | Flywheel Energy Storage |

| FI | Fragility Index |

| FLS | Forced Load Shedding |

| GCNs | Graph Convolutional Networks |

| GFL | Grid-Following |

| GFM | Grid-Forming |

| GIS | Geographical Information System |

| H-EIES | Hydrogen-Electricity Integrated Energy System |

| HESS | Hybrid Energy Storage System |

| HFC | Hydrogen Fuel Cell |

| HILP | High-Impact, Low-Probability |

| HPO | Hunting Prey Optimization |

| HSS | Hydrogen Storage System |

| HV | High-Voltage |

| IEHS | Integrated Electricity and Heat System |

| IES | Integrated Energy System |

| IGDT | Information-Gap Decision Theory |

| LA | Los Angeles |

| LIB | Lithium-Ion Battery |

| LLI | Lost Load Index |

| LLR | Load Loss Rate |

| LOLE | Loss of Load Expectation |

| LOLF | Loss of Load Frequency |

| LOLP | Loss of Load Probability |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| LPSP | Loss of Power Supply Probability |

| MEGs | Mobile Emergency Generators |

| MEMG | Multi-Energy Microgrid |

| MERs | Mobile Energy Resources |

| MESS | Mobile Energy Storage System |

| MG | Microgrid |

| MIP | Mixed-Integer Programming |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MINLP | Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming |

| MIQCP | Mixed-Integer Quadratically Constrained Programming |

| MISOCP | Mixed-Integer Second-Order Cone Programming |

| MMES | Mobile Multi-Energy Storage |

| MMG | Multi-Microgrid |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MRI | Microgrid Resilience Index |

| MV | Medium-Voltage |

| MVI | Microgrid Voltage Index |

| NMGs | Networked Microgrids |

| NPC | Net Present Cost |

| OWFs | Offshore Wind Farms |

| P2H | Power-to-Hydrogen |

| P2P | Peer-to-Peer |

| PEV | Plug-in Electric Vehicle |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| PHEVs | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| PS | Pumped Storage |

| PSPSs | Public Safety Power Shutoffs |

| PVDG | Photovoltaic Distributed Generation |

| PV-ES-CS | PV-Energy Storage-Charging Station |

| REI | Restoration Index |

| RTS | Reliability Test System |

| RF | Resilience Function |

| RI | Resilience Index |

| RO | Robust Optimization |

| SC | Supercapacitor |

| SCW | Severe Convective Weather |

| SDN | Smart Distribution Network |

| SDRO | Stochastic Distributionally Robust Optimization |

| SESS | Stationary Energy Storage System |

| SFL | Shuffled Frog Leaping |

| SMES | Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage |

| SMI-ESS | Stationary-Mobile Integrated Energy Storage System |

| SMIP | Stochastic Mixed-Integer Programming |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SOCP | Second-Order Cone Programming |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedure |

| SRO | Stochastic Robust Optimization |

| TBES | Transportable Battery Energy System |

| TES | Thermal Energy Storage |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| UC | Unit Commitment |

| UESS | Underground Energy Storage System |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| VPP | Virtual Power Plant |

| VSG | Virtual Synchronous Generator |

| WRAP | Withstand, Recover, Adapt, and Prevent |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

References

- Dugan, J.; Mohagheghi, S.; Kroposki, B. Application of Mobile Energy Storage for Enhancing Power Grid Resilience: A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, A.M.; Tomsovic, K.L.; Caro, F.D.; Braun, M.; Chow, J.H.; Čukalevski, N.; Dobson, I.; Eto, J.; Fink, B.; Hachmann, C.; Hill, D.; Ji, C.; Kavicky, J.A.; Levi, V.; Liu, C.C.; Mili, L.; Moreno, R.; Panteli, M.; Petit, F.D.; Sansavini, G.; Singh, C.; Srivastava, A.K.; Strunz, K.; Sun, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, S. Methods for Analysis and Quantification of Power System Resilience. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2023, 38, 4774–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Pal, N.; Saini, D.K. Microgrid Control, Storage, and Communication Strategies to Enhance Resiliency for Survival of Critical Load. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 169047–169069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, S. California outages exceed 425,000 as wildfires continue to blaze. Available online: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/power-grid/outage-management/california-outages-exceed-425000-as-wildfires-continue-to-blaze/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Penn, B.J.D.G. a. I. Rising Frustration in Houston After Millions Lost Power in Storm. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/10/us/hurricane-beryl-texas-grid.html# (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Scanlan, S. 308,000 households lose power after Taiwan quake. Available online: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/news/5135776 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Brooks, B. US South, Midwest face 'generational' flood threat after severe storms, two dead. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/warning-generational-floods-storms-hit-us-midwest-south-2025-04-03/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Lofton, J. Northern Michigan ice storm was ‘orders of magnitude worse’ than Blizzard of 1978. Available online: https://www.mlive.com/news/2025/04/northern-michigan-ice-storm-was-orders-of-magnitude-worse-than-blizzard-of-1978.html (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Abdolahi, A.; Samadi Gharehveran, S.; Shirini, K. Optimizing Energy Storage Solutions for Grid Resilience:A Comprehensive Overview. In Energy Storage Devices - A Comprehensive Overview, Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Mossa, M.A.; Bajaj, M. Eds. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2025.

- Mishra, D.K.; Eskandari, M.; Abbasi, M.H.; Sanjeevikumar, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. A detailed review of power system resilience enhancement pillars. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 230, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, L.; Zhao, X.; Tong, L.; Wang, L.; Ding, J.; Ding, Y. Energy storage for black start services: A review. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials 2022, 29, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugrin, E.D.; Castillo, A.R.; Silva-Monroy, C.A. Resilience Metrics for the Electric Power System: A Performance-Based Approach; Sandia National Lab. (SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States): United States, 2017; p Medium: ED.; Size: 49 p.

- Watson, J.-P.; Guttromson, R.; Silva-Monroy, C.; Jeffers, R.; Jones, K.; Ellison, J.; Rath, C.; Gearhart, J.; Jones, D.; Corbet, T.; Hanley, C.; Walker, L.T. Conceptual Framework for Developing Resilience Metrics for the Electricity, Oil, and Gas Sectors in the United States; Sandia National Lab. (SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States): United States, 2014; p Medium: ED.; Size: 104 p.

- Izadi, M.; Hosseinian, S.H.; Dehghan, S.; Fakharian, A.; Amjady, N. A critical review on definitions, indices, and uncertainty characterization in resiliency-oriented operation of power systems. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 2021, 31, e12680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.S.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Surinkaew, T.; Islam, S. Resiliency Assessment and Enhancement of Renewable Dominated Edge of Grid Under High-Impact Low-Probability Events—A Review. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 7578–7598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P. The Grid: Stronger, Bigger, Smarter?: Presenting a Conceptual Framework of Power System Resilience. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2015, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Wilkinson, S.; Dawson, R.J.; Fowler, H.J.; Kilsby, C.; Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P. Integrated Approach to Assess the Resilience of Future Electricity Infrastructure Networks to Climate Hazards. IEEE Systems Journal 2018, 12, 3169–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Shahidehpour, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, B. Integrated Planning of Electricity and Natural Gas Transportation Systems for Enhancing the Power Grid Resilience. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 4418–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shahidehpour, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Bie, Z. Microgrids for Enhancing the Power Grid Resilience in Extreme Conditions. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2017, 8, 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, B.; Xie, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Q. Availability-based engineering resilience metric and its corresponding evaluation methodology. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2018, 172, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- COUNCIL, N.I.A. CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE RESILIENCE FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS; 2009.

- Abbasi, S.; Barati, M.; Lim, G.J. A Parallel Sectionalized Restoration Scheme for Resilient Smart Grid Systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 10, 1660–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanian, P.; Aslan, S.; Dehghanian, P. In Quantifying power system resiliency improvement using network reconfiguration, 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), 6-9 Aug. 2017, 2017; 2017; pp 1364-1367.

- Panteli, M.; Trakas, D.N.; Mancarella, P.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Power Systems Resilience Assessment: Hardening and Smart Operational Enhancement Strategies. Proceedings of the IEEE 2017, 105, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, M.; Mancarella, P.; Trakas, D.N.; Kyriakides, E.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Metrics and Quantification of Operational and Infrastructure Resilience in Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 4732–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C.C. Resilience-Oriented Critical Load Restoration Using Microgrids in Distribution Systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Mei, S.; Huang, S.; Xu, Y. Resilience-Oriented Pre-Hurricane Resource Allocation in Distribution Systems Considering Electric Buses. Proceedings of the IEEE 2017, 105, 1214–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavousi-Fard, A.; Wang, M.; Su, W. Stochastic Resilient Post-Hurricane Power System Recovery Based on Mobile Emergency Resources and Reconfigurable Networked Microgrids. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 72311–72326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, C.C.; Wang, Z.; Mo, K.; Schneider, K.P.; Tuffner, F.K.; Ton, D.T. DGs for Service Restoration to Critical Loads in a Secondary Network. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 10, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O'Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthquake Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Liu, W.; Zeng, B.; Hui, H.; Li, F. Enhancing distribution system resilience against extreme weather events: Concept review, algorithm summary, and future vision. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2022, 138, 107860. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Guo, J.; Jian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Tang, W. In Dynamic Assessment of Resilience of Power Transmission Systems in Ice Disasters, 2018 International Conference on Power System Technology (POWERCON), 6-8 Nov. 2018, 2018; 2018; pp 7-13.

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, C.; Cai, Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Pecht, M. Maximizing Network Resilience against Malicious Attacks. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L. Multi-dimensional hurricane resilience assessment of electric power systems. Structural Safety 2014, 48, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiskens, D.S.S.A.I. Evaluating Resilience of Electricity Distribution Networks via A Modification of Generalized Benders Decomposition Method. In 2020.

- Devendra Shelar, S.A. Ian Hiskens, Resilience of Electricity Distribution Networks - Part II: Leveraging Microgrids. In 2019.

- Ayyub, B.M. Practical Resilience Metrics for Planning, Design, and Decision Making. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering 2015, 1, 04015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.M. HTGR Resilient Control System Strategy; Idaho National Lab. (INL), Idaho Falls, ID (United States): United States, 2010; p Medium: ED.

- Luo, D.; Xia, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, B.; Yu, H.; Wu, Q. Evaluation Method of Distribution Network Resilience Focusing on Critical Loads. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 61633–61639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, H.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M. Enhancing Power System Resilience Through Hierarchical Outage Management in Multi-Microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2869–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, S.; Reddy, T.A. Sustainability of integrated energy systems: A performance-based resilience assessment methodology. Applied Energy 2018, 228, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P.; Chanda, S.; Srivastava, A.K. A Novel Metric to Quantify and Enable Resilient Distribution System Using Graph Theory and Choquet Integral. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2018, 9, 2918–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Dehghanian, P. Energy Storage Planning for Enhanced Resilience of Power Distribution Networks Against Earthquakes. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2020, 11, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Mohanpurkar, M.U.; Hovsapian, R. Quantifying Power Distribution System Resiliency Using Code-Based Metric. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2018, 54, 3676–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, M.; Cody, C. Resilience in Regulated Utilities; NARUC Grants & Research: November 2013, 2013.

- Raoufi, H.; Vahidinasab, V.; Mehran, K. Power Systems Resilience Metrics: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Outlook. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Ramasamy, A.K.; Verayiah, R.; Bastia, S.; Dash, S.S.; Cuce, E.; Khan, T.M.Y.; Soudagar, M.E.M. Power system resilience and strategies for a sustainable infrastructure: A review. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 105, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, K.; Wolińska, A. The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture – A review. CATENA 2023, 231, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shahidehpour, M.; Aminifar, F.; Alabdulwahab, A.; Al-Turki, Y. Networked Microgrids for Enhancing the Power System Resilience. Proceedings of the IEEE 2017, 105, 1289–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Dabbaghjamanesh, M.; Farughian, A.; Khosravi, A. Effective Management of Energy Internet in Renewable Hybrid Microgrids: A Secured Data Driven Resilient Architecture. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 1896–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Dai, C.; Wu, L.; Liu, T. Robust Network Hardening Strategy for Enhancing Resilience of Integrated Electricity and Natural Gas Distribution Systems Against Natural Disasters. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 5787–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loma-Osorio, I.; Borge-Diez, D.; Herskind Sejr, J.; Rosales-Asensio, E. Enhancing commercial building resiliency through microgrids with distributed energy sources and battery energy storage systems. Energy and Buildings 2024, 325, 114980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, K.; Davoudi, M. Electric vehicles for improving resilience of distribution systems. Sustainable Cities and Society 2018, 36, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Asensio, E.; de Simón-Martín, M.; Rosales, A.-E.; Colmenar-Santos, A. Solar-plus-storage benefits for end-users placed at radial and meshed grids: An economic and resiliency analysis. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 128, 106675. [Google Scholar]

- Alizad, E.; Hasanzad, F.; Rastegar, H. A tri-level hybrid stochastic-IGDT dynamic planning model for resilience enhancement of community-integrated energy systems. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 117, 105948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashanizadeh, B.; Shourkaei, H.M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M. Short-term resilience-oriented enhancement in smart multiple residential energy system using local electrical storage system, demand side management and mobile generators. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Ghasemi, A. Stochastic scheduling of resilient interconnected energy hubs considering peer-to-peer energy trading and energy storages. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, H. a.; Jalilvand, A.; Bagheri, A.; Rabiee, A. Hybridization of planning and operational techniques for resiliency improvement of electrical distribution networks against multi-scenario natural disasters based on a convex model. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 237, 111043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, M.; Kalantar, M. Enhance the resilience of distribution system against direct and indirect effects of extreme winds using battery energy storage systems. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 76, 103486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati-Oskuee, M.-R.; Gholizadeh-Roshanagh, R.; Najafi-Ravadanegh, S. Robust expansion planning of reliable and resilient smart distribution network equipped by storage devices. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 229, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian, S.; Kazemi, A. Resilience enhancement of active distribution networks in the presence of wind turbines and energy storage systems by considering flexible loads. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 48, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Shi, W.; Fang, R.; Wu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Underground energy storage system supported resilience enhancement for power system in high penetration of renewable energy. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Tang, W.; Long, C. Allocation method of coupled PV-energy storage-charging station in hybrid AC/DC distribution networks balanced with economics and resilience. IET Renewable Power Generation 2024, 18, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wen, F. Data-Driven Stochastic-Robust Planning for Resilient Hydrogen-Electricity System with Progressive Hedging Decoupling. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, V.B.; Saini, D.K.; Sharma, M. Techno-economic hardening strategies to enhance distribution system resilience against earthquake. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 213, 107682. [Google Scholar]

- Gilasi, Y.; Hosseini, S.H.; Ranjbar, H. Resilience-oriented planning and management of battery storage systems in distribution networks. IET Renewable Power Generation 2023, 17, 2575–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayarshad, H.R.; Sabarshad, O.; Amjady, N. Evaluating resiliency of electric power generators against earthquake to maintain synchronism. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 210, 108127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Dehghanian, P. Powering Through Wildfires: An Integrated Solution for Enhanced Safety and Resilience in Power Grids. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2022, 58, 4192–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Hossein Hosseinian, S.; Dehghan, S.; Fakharian, A.; Amjady, N. Resiliency-Oriented operation of distribution networks under unexpected wildfires using Multi-Horizon Information-Gap decision theory. Applied Energy 2023, 334, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Islam, S. Prediction of fire danger index using a new machine learning based method to enhance power system resiliency against wildfires. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2024, 18, 4008–4022. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Shakhawat, N.S.B.; Aslam, M.U.; Miah, M.S. Wildfire Impacts on Security of Electric Power Systems: A Survey of Risk Identification and Mitigation Approaches. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 173047–173065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehveran, S.S.; Zadeh, S.G.; Rostami, N. Resilience-oriented planning and pre-positioning of vehicle-mounted energy storage facilities in community microgrids. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Razeghi, G.; Samuelsen, S. Utilization of Battery Electric Buses for the Resiliency of Islanded Microgrids. Applied Energy 2023, 347, 121295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rousis, A.O.; Qiu, D.; Strbac, G. A stochastic distributed control approach for load restoration of networked microgrids with mobile energy storage systems. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 148, 108999. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, S.; Amjady, N. A new optimal power flow approach for wind energy integrated power systems. Energy 2017, 134, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjady, N.; Rashidi, A.A.; Zareipour, H. Stochastic security-constrained joint market clearing for energy and reserves auctions considering uncertainties of wind power producers and unreliable equipment. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 2013, 23, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, M.; Amjady, N.; Bagheri, B.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Robust Resiliency-Oriented Operation of Active Distribution Networks Considering Windstorms. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 35, 3481–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Dehghanian, P.; Darestani, Y.; Su, J. Parameterized Wildfire Fragility Functions for Overhead Power Line Conductors. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2024, 39, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufakis, E.I.; Tsarabaris, P.T.; Katsanis, J.S.; Karagiannopoulos, C.G.; Bourkas, P.D. A Wildfire Model for the Estimation of the Temperature Rise of an Overhead Line Conductor. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2010, 25, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State of Victoria Department of Environment, L. Water and Planning Victorian Neighbourhood Battery Initiative; 2020.

- Oskouei, M.Z.; Mehrjerdi, H. Multi-Stage Proactive Scheduling of Strategic DISCOs in Mutual Interaction With Cloud Energy Storage and Deferrable Loads. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2023, 14, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramara, S.; Khezri, R.; Haque, M.H. Resiliency-Oriented Economic Sizing of Battery for a Residential Community: Cloud Versus Distributed Energy Storage Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 1963–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, D.; Li, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Tu, R.; Zhou, Y. City-scale information modelling for urban energy resilience with optimal battery energy storages in Hong Kong. Applied Energy 2025, 378, 124813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeimozafar, M.; Monaghan, R.F.D.; Barrett, E.; Duffy, M. A review of behind-the-meter energy storage systems in smart grids. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 164, 112573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanocco, C.; Flora, J.; Rajagopal, R.; Boudet, H. When the lights go out: Californians’ experience with wildfire-related public safety power shutoffs increases intention to adopt solar and storage. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 79, 102183. [Google Scholar]

- Angizeh, F.; Ghofrani, A.; Zaidan, E.; Jafari, M.A. Resilience-Oriented Behind-the-Meter Energy Storage System Evaluation for Mission-Critical Facilities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 80854–80865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedi, A.Z.G.; Armand, M.J.; Akbari, E.; Moosanezhad, J.; Khorasani, F.; Raeisinia, M. A non-linear resilient-oriented planning of the energy hub with integration of energy storage systems and flexible loads. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Ahmarinejad, A.; Tabrizian, M.; Bidgoli, M.A. Resilience enhancement of integrated electricity-gas-heating networks through automatic switching in the presence of energy storage systems. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhai, Q.; Guan, X. Risk-constrained planning of rural-area hydrogen-based microgrid considering multiscale and multi-energy storage systems. Applied Energy 2023, 334, 120682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Han, H.; Wei, Z.; Zang, H.; Sun, G.; Chen, S. Resilience-oriented planning of integrated electricity and heat systems: A stochastic distributionally robust optimization approach. Applied Energy 2024, 353, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Z.; Lin, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, J. Optimal Configuration of Multi-Energy Storage in an Electric–Thermal–Hydrogen Integrated Energy System Considering Extreme Disaster Scenarios. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y. Integrated optimization of a regional integrated energy system with thermal energy storage considering both resilience and reliability. Energy 2022, 261, 125333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, A.; Shayeghi, H.; Siano, P.; Safari, A. A multi-objective resilience-economic stochastic scheduling method for microgrid. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 131, 106974. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Deng, X.; Chen, H.; Islam, M.R. A two-layer optimal configuration approach of energy storage systems for resilience enhancement of active distribution networks. Applied Energy 2023, 350, 121720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Alharthi, Y.Z.; Safaraliev, M. A techno-economic model for flexibility-oriented planning of renewable-based power systems considering integrated features of generator, network, and energy storage systems. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Liao, J.-T.; Yang, H.-T. Three-stage resilience enhancement via optimal dispatch and reconfiguration for a microgrid. Frontiers in Energy Research 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarpour, P.; Nazar, M.S.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Resiliency assessment of the distribution system considering smart homes equipped with electrical energy storage, distributed generation and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, G. A three-stage robust model for resilient DERs planning in distribution networks. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Rojas, D.; Mashlakov, A.; Brester, C.; Niska, H.; Kolehmainen, M.; Narayanan, A.; Honkapuro, S.; Nardelli, P.H.J. Weather-Driven Predictive Control of a Battery Storage for Improved Microgrid Resilience. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 163108–163121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. Coordinated Distributionally Robust Optimal Allocation of Energy Storage System for HV-MV Distribution Network Resilience Enhancement. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Shittu, E. Optimizing energy storage capacity for enhanced resilience: The case of offshore wind farms. Applied Energy 2025, 378, 124718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momen, H.; Jadid, S. A novel microgrid formation strategy for resilience enhancement considering energy storage systems based on deep reinforcement learning. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 100, 113565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushal, T.R.B.; Illindala, M.S. Decision Support Framework for Resilience-Oriented Cost-Effective Distributed Generation Expansion in Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2021, 57, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.N.V.; Bhende, C.N.; Srivastava, A.K. Intelligent Control of Battery Storage for Resiliency Enhancement of Distribution System. IEEE Systems Journal 2022, 16, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraibi, W.A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Hosseini, S.H.; Abapour, M. A resilience-oriented optimal planning of energy storage systems in high renewable energy penetrated systems. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 67, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Muyeen, S.M.; Mousavi, S.A. Development of new reliability metrics for microgrids: Integrating renewable energy sources and battery energy storage system. Energy Reports 2023, 10, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, T.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Arun, S.; Thanikanti, S.B.; Nwulu, N. Optimizing virtual power plant allocation for enhanced resilience in smart microgrids under severe fault conditions using the hunting prey optimization algorithm. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 6094–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, L.; Panteli, M.; Parvania, M. Coordinated recovery of interdependent power and water distribution systems. IET Smart Grid 2024, 7, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Peng, X.L.; Li, T.Y.; Hsu, Y.C.; Tseng, C.C.; Prokhorov, A.V.; Mokhlis, H.; Chua, K.H.; Tripathy, M. Grid Resilience Enhancement and Stability Improvement of an Autonomous DC Microgrid Using a Supercapacitor-Based Energy Storage System. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, J. Photovoltaic-penetrated power distribution networks’ resiliency-oriented day-ahead scheduling equipped with power-to-hydrogen systems: A risk-driven decision framework. Energy 2024, 299, 131115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Gevorgian, V.; Koralewicz, P.; Alam, S.M.S.; Mendiola, E. Regional Power System Black Start with Run-of-River Hydropower Plant and Battery Energy Storage. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, M.; Ghassemi, M. Optimal planning of microgrids for resilient distribution networks. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 128, 106682. [Google Scholar]

- Niknami, A.; Tolou Askari, M.; Amir Ahmadi, M.; Babaei Nik, M.; Samiei Moghaddam, M. Resilient day-ahead microgrid energy management with uncertain demand, EVs, storage, and renewables. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2024, 20, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jian, L.; Wang, W.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dastbaz, P. The role of energy storage systems in resilience enhancement of health care centers with critical loads. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Yin, Z.; Xiao, G.; Fan, B.; Wang, P. A Two-Stage Robust Approach for Resilient Unit Commitment With Rail-Based Mobile Energy Storage Under Diffusional Uncertainties. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J. An allocative method of stationary and vehicle-mounted mobile energy storage for emergency power supply in urban areas. Energy Storage 2024, 6, e681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, H. Enhancing resilience and sustainability of distribution networks by emergency operation of a truck-mounted mobile battery energy storage fleet. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2023, 34, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Tan, W.S.; Wu, Y.K. Resilience Oriented Unit Commitment Considering Transportable Energy System Under Typhoon Impact. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 2673–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.E.; Marzband, M.; Ikpehai, A.; Abusorrah, A. Optimal stochastic scheduling of plug-in electric vehicles as mobile energy storage systems for resilience enhancement of multi-agent multi-energy networked microgrids. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltan, G.; Pirouzi, S.; Azarhooshang, A.; Rezaee Jordehi, A.; Paeizi, A.; Ghadamyari, M. Storage-integrated virtual power plants for resiliency enhancement of smart distribution systems. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Li, G. Resilience enhancement strategies for power distribution network based on hydrogen storage and hydrogen vehicle. IET Energy Systems Integration 2024, (S1), 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee Jordehi, A.; Mansouri, S.A.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Iqbal, A.; Marzband, M.; Jurado, F. Industrial energy hubs with electric, thermal and hydrogen demands for resilience enhancement of mobile storage-integrated power systems. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenoğlu, A.K.; Erdinç, O. Post-Event restoration strategy for coupled distribution-transportation system utilizing spatiotemporal flexibility of mobile emergency generator and mobile energy storage system. Electric Power Systems Research 2021, 199, 107432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.Y.; Hussain, A.; Baek, J.-W.; Kim, H.-M. Optimal Operation of Networked Microgrids for Enhancing Resilience Using Mobile Electric Vehicles. Energies 2021, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Liang, H.; Bittner, M. Stochastic Planning for Power Distribution System Resilience Enhancement Against Earthquakes Considering Mobile Energy Resources. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 15, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ding, T.; Mu, C.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, M. A distributionally robust resilience enhancement model for transmission and distribution coordinated system using mobile energy storage and unmanned aerial vehicle. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2023, 152, 109256. [Google Scholar]

- Bayani, R.; Manshadi, S. An Agile Mobilizing Framework for V2G-Enabled Electric Vehicles under Wildfire Risk. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgen, B.G.; Garcia, M.; Yip, J.J.; Arguello, B.; Pierre, B.J.; Kutanoglu, E.; Hasenbein, J.J.; Santoso, S. Three-Stage Optimization Model to Inform Risk-Averse Investment in Power System Resilience to Winter Storms. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 135117–135134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.K.; Ghadi, M.J.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Hossain, M.J. Active distribution system resilience quantification and enhancement through multi-microgrid and mobile energy storage. Applied Energy 2022, 311, 118665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Arefifar, S.A. IoT-Based Mobile Energy Storage Operation in Multi-MG Power Distribution Systems to Enhance System Resiliency. In Energies, 2022; Vol. 15.

- Rahimi Sadegh, A.; Setayesh Nazar, M.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Optimal resilient allocation of mobile energy storages considering coordinated microgrids biddings. Applied Energy 2022, 328, 120117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qian, T.; Li, W.; Zhao, W.; Tang, W.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z. Mobile energy storage systems with spatial–temporal flexibility for post-disaster recovery of power distribution systems: A bilevel optimization approach. Energy 2023, 282, 128300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazzaq Oraibi, W.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Hosseini, S.H.; Abapour, M. Multi Microgrid Framework for Resilience Enhancement Considering Mobile Energy Storage Systems and Parking Lots. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani Gargari, M.; Tarafdar Hagh, M.; Ghassem Zadeh, S. Preventive scheduling of a multi-energy microgrid with mobile energy storage to enhance the resiliency of the system. Energy 2023, 263, 125597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noutash, A.; Kalantar, M. Resilience Enhancement with Transportable Storage Systems and Repair Crews in Coupled Transportation and Distribution Networks. Sustainable Cities and Society 2023, 99, 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; He, Y. A Two-Stage Stochastic Programming Model for Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks With Mobile Energy Storage Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2024, 39, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, T. Two-Stage Optimization of Mobile Energy Storage Sizing, Pre-Positioning, and Re-Allocation for Resilient Networked Microgrids with Dynamic Boundaries. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ruan, G.; Zhong, H. Resilient distribution network with degradation-aware mobile energy storage systems. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 230, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhou, B.; Yang, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, J. Computing Optimal Resilience-Oriented Operation of Distribution Systems Considering Heterogenous Consumer-Side Microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, H.; Wang, X.; Shu, D.; Yang, J.; Yu, P.; Zhu, M.; Tao, J. Disaster management approaches for active distribution networks based on Mobile Energy Storage System. Electric Power Systems Research 2025, 239, 111242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Shen, Y.; Xie, X. A novel robust optimization method for mobile energy storage pre-positioning. Applied Energy 2025, 379, 124810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchana, K.; Murali Krishna, T.; Yuvaraj, T.; Sudhakar Babu, T. Enhancing Smart Microgrid Resilience Under Natural Disaster Conditions: Virtual Power Plant Allocation Using the Jellyfish Search Algorithm. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, S.; Moshtagh, J. Distribution system restoration after extreme events considering distributed generators and static energy storage systems with mobile energy storage systems dispatch in transportation systems. Applied Energy 2022, 310, 118507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.; Sriram, U.; Mohammadi, J. In Sharing Mobile and Stationary Energy Storage Resources in Transactive Energy Communities, 2021 IEEE Madrid PowerTech, 28 June-2 July 2021, 2021; 2021; pp 1-6.

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yi, Z.; Xu, D. Planning of Stationary-Mobile Integrated Battery Energy Storage Systems under Severe Convective Weather. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, A.A.; Abdeltawab, H.; Mohamed, Y.A.R.I. Towards Resilient Self-Proactive Distribution Grids Against Wildfires: A Dual Rolling Horizon-based Framework. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, A.A.; Shaaban, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.; Zeineldin, H.H.; El-Saadany, E.F. A Dynamic Optimal Battery Swapping Mechanism for Electric Vehicles Using an LSTM-Based Rolling Horizon Approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 15218–15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xie, D.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. Resilience enhancement of a multi-energy distribution system via joint network reconfiguration and mobile sources scheduling. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- J. I, L.; Dominguez, E.; Wu, L.; Alcaide, A.M.; Reyes, M.; Liu, J. Hybrid Energy Storage Systems: Concepts, Advantages, and Applications. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2021, 15, 74–88. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.U.; Shakhawat, N.S.B.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Miah, M.S.; Amin, B.M.R. Hybrid Energy Storage Modeling and Control for Power System Operation Studies: A Survey. Energies 2024, 17, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, M.A.; Yakub, A.O.; Rabiu, A.; Owolabi, A.B.; Ogunlowo, Q.O.; Yahaya, A.; Na, W.-H.; Kim, M.-H.; Kim, H.-T.; Lee, H.-W. Dynamic modeling and techno-economic assessment of hybrid renewable energy and thermal storage systems for a net-zero energy greenhouse in South Korea. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2024, 26, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutikno, T.; Arsadiando, W.; Wangsupphaphol, A.; Yudhana, A.; Facta, M. A Review of Recent Advances on Hybrid Energy Storage System for Solar Photovoltaics Power Generation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 42346–42364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, F.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, Q.; Xiao, X.; Zong, Y.; Huang, C. Enhancing resilience of DC microgrids with model predictive control based hybrid energy storage system. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 128, 106738. [Google Scholar]

- Bazdar, E.; Nasiri, F.; Haghighat, F. Resilience-centered optimal sizing and scheduling of a building-integrated PV-based energy system with hybrid adiabatic-compressed air energy storage and battery systems. Energy 2024, 308, 132836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Shahidehpour, M. DC microgrids: Economic operation and enhancement of resilience by hierarchical control. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2014, 5, 2517–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Qin, B.; Hong, S.; Cai, Q.; Li, F.; Ding, T.; Li, H. Optimal planning of hybrid hydrogen and battery energy storage for resilience enhancement using bi-layer decomposition algorithm. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 110, 115367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Woo, H.; Noh, J.; Dehghanian, P.; Zhang, X.; Choi, S. Optimization of energy storage scheduling considering variable-type minimum SOC for enhanced disaster preparedness. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 93, 112366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemifar, S.M.A.; Joorabian, M.; Javadi, M.S. Two-layer robust optimization framework for resilience enhancement of microgrids considering hydrogen and electrical energy storage systems. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33597–33618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, J.; Gao, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Han, X.; Cao, Y.-c.; Lu, L.; Wen, J.; Cheng, S.; Ouyang, M. Effect of preload forces on multidimensional signal dynamic behaviours for battery early safety warning. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2024, 92, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, E. The LA fires burned a lot of lithium-ion batteries. What does that say about a clean energy future? Available online: https://laist.com/news/climate-environment/la-fires-lithium-ion-batteries-clean-energy-future (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- EVs in Wildfires…The New Safety Risks As Recovery Begins. Available online: https://www.evfiresafe.com/post/evs-in-wildfires (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Prada, L. Burning EV Batteries Are Delaying LA Wildfire Clean-Up. Available online: https://www.vice.com/en/article/burning-ev-batteries-are-delaying-la-wildfire-clean-up/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Kwon, B. Ignition and Burning Behavior of Modern Fire Hazards: Firebrand Induced Ignition and Thermal Runaway of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Ph.D. Case Western Reserve University, United States -- Ohio, 2023.

- Joshi, T.; Azam, S.; Lopez, C.; Kinyon, S.; Jeevarajan, J. Safety of Lithium-Ion Cells and Batteries at Different States-of-Charge. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2020, 167, 140547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; He, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Experimental study on the thermal behaviors of lithium-ion batteries under discharge and overcharge conditions. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2018, 132, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Liu, X.; Sun, R.; Shi, D.; Liu, B.; Xiao, P.; Zhi, M.; Wang, Z. Relationship between interior temperature and exterior parameters for thermal runaway warning of large-format LiFePO4 energy storage cells with various heating patterns and heating powers. Applied Thermal Engineering 2025, 269, 126062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamenu, L.; Lee, H.S.; Latifatu, M.; Kim, K.M.; Park, J.; Baek, Y.G.; Ko, J.M.; Kaner, R.B. Lithium-silica nanosalt as a low-temperature electrolyte additive for lithium-ion batteries. Current Applied Physics 2016, 16, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Qi, X.; Song, D.; Ruan, H. Review of Low-Temperature Performance, Modeling and Heating for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2023, 16, 7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Knapp, M.; Darma, M.S.D.; Fang, Q.; Wang, X.; Dai, H.; Wei, X.; Ehrenberg, H. An improved electro-thermal battery model complemented by current dependent parameters for vehicular low temperature application. Applied Energy 2019, 248, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Huang, W.; Liu, S. A Temperature and Current Rate Adaptive Model for High-Power Lithium-Titanate Batteries Used in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 67, 9492–9502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HILP Event | Year | Number of power outages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles (LA) Wildfire | 2025 | 425,000 | [4] |

| Hurricane Beryl in Texas | 2024 | 2,700,000 | [5] |

| Hualien Earthquake in Taiwan | 2024 | 308,000 | [6] |

| US Spring Storm and Flood Event | 2024 | 400,000 | [7] |

| Northern Michigan Ice Storm | 2025 | 100,000 | [8] |

| Ref. | Type of SESS | Objective | Resilience Index/ Resilience Metric |

Event | Optimization Model |

Test System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [93] | BESS and Electric Vehicle Parking lots (EVPs) | To optimize MG operation cost and resilience function (RF) | Timely awareness capability, fragility index (FI), restoration index (REI), MG voltage index (MVI) and lost load index (LLI) | Natural disasters | A bi-level resilience-oriented stochastic scheduling, MILP | IEEE 33-bus |

| [54] | BESS | To minimize the cost of energy throughout the life cycle of project | Cost of interruption | Hurricane | MILP | 3 critical infrastructures in New York city (high schools, fire stations, and residences) |

| [55] | HSS | To minimize the total unserved load | Unserved load | Hurricane, earthquake, and extreme cold weather | LP | A community integrated energy system (CIES) |

| [56] | BESS | To minimize operation costs and LPSP | LPSP | Hurricanes | 3-stage optimization, shuffled frog leaping (SFL) algorithm for all stages | IEEE 33-bus |

| [57] | BESS | To maximize profit and minimize load shedding | The ratio of energy served during emergency response time to the expected energy demand | Windstorms | Stochastic optimization mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) | 3 EHs |

| [58] | BESS | To minimize Line hardening cost and load shedding cost | Mechanical strength of pole multiplied by the sum of pole and distribution line failure rates against windstorm | Windstorms | Mixed-integer quadratically constrained programming (MIQCP) | IEEE 33-bus |

| [59] | BESS | To increase RI and minimize penalty cost | The ratio of power injection by the total number of batteries to the total demand for critical loads | Extreme winds | 2-step linear programming (LP) optimization problem | DS of Urmia city |

| [62] | UESS | To minimize operation cost and load shedding cost | Load shedding cost | Ice storm, typhoon | 2-stage optimization MILP | Modified IEEE reliability test system (RTS)-79 |

| [63] | BESS | To minimize cost and maximize resilience | Reduction in power outage loss | Typhoon | A bi-level model that balances the economics and resilience | Coupled PV-ES-CS for restoration,Different topologies of hybrid AC/DC system |

| [64] | HSS | To minimize the investment and load shedding costs | Cost of load shedding | Typhoons | A tri-layer SRO,min-max-min model | H-EIES composed of a 24-bus power grid and a 5-node hydrogen network |

| [65] | BESS and EVs | To minimize the cost for establishing energy storage units, underground cables, and communication infrastructure for BESS | The ratio of energy served during emergency response time to the expected energy demand | Earthquake | MINLP | 156-bus DS of Dehradun district, India |

| [66] | BESS | To minimize the weighted sum of planning cost and normal/emergency operation cost | Load curtailment cost | Earthquake | MILP | IEEE 33-bus |

| [68] | ESS | To minimize operation cost | Load shedding cost | Wildfires | MILP | IEEE 33-bus |

| [81] | BESS | To minimize operating cost, maximize reserve index | Reserve index | Unexpected event | Multi-stage resilience-promoting proactive strategy,MILP | IEEE 69-bus |

| [82] | BESS | To minimize NPC | Outage duration | Grid outages due to extreme weather | Stochastic model for optimal sizing of CBES | A typical South Australian residential community feeder with 500 end-users |

| [83] | BESS | To minimize the demand-weighted distance between demand nodes and PV-BESS facilities, considering energy resilience | Cost of power outage | Extreme weather event | Capacitated p-Median Problem for optimal deployment of BESS | Yau Tsim Mong District in Hong Kong having residential and non-residential buildings |

| [86] | BTM-ESS | To minimize total operation cost | Avoided loss of load(ALOL) | Extreme weather events | MILP | 24 mission-critical facilities |

| [114] | BESS | To minimize cost | Unserved load | Unpredicted power outages | LP | A hospital in Iran |

| [92] | TES | To minimize system operation cost and required storage capacity | Energy satisfaction rate as the ratio of load shedding to load demand | Extreme weather events | 2-stage Rolling window optimization model | A regional IES located in Lin-gang Special Area of Shanghai, China |

| [94] | BESS | To minimize cost, maximize fault recovery | Resilience score is based on the node voltage deviation, fault recovery rate, and network loss rate. | Extreme weather-driven multi faults | 2-layer optimization model: outer layer as MILP and inner layer as mixed-integer second-order cone programming (MISOCP) | modified IEEE 33-bus and 118-bus test systems |

| [95] | ESS | To minimize operation cost | Cost of load shedding | Unplanned outage | Two-layer flexibility-oriented planning model | Modified two-region IEEE 24-bus test system and an operational test system in China |

| [100] | ESS | To maximize economy and resilience | Three planning RIs: voltage violation risk of bus, coverage rate of reserve power supply, reliability of power supply pathsOne operational RI: weighted load loss | Extreme event | A two-stage coordinated distributionally robust optimization (DRO) (integrating deep learning with optimization) | IEEE 14-bus and 33-bus, modified IEEE 123-bus |

| [101] | BESS | To minimize resilience cost for planning the backup BESSs |

Resilience cost | HILP events causing short to medium-term outages | 2-stage stochastic programming | Case-1 is derived from a real OWF network called Banc de Guérance, France, Case-2 and Case-3 involve OWFs comprising 80 WTs at FINO3 research platform, Germany |

| [96] | BESS | To optimize minimum load supply, total supplied energy, and recovery to degradation slope ratio | Three RIs: minimum load supply, total supplied energy, and recovery-to-degradation slope ratio | Extreme weather events | Three-stage resilience optimal dispatch and reconfiguration strategy | A practical large-scale manufacturing campus MG in Taiwan |

| [97] | Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), EES and TES | To minimize operation cost in day-ahead and real-time | The ratio of the total served load in contingency conditions and the difference between the total served load in normal conditions and the total served load in contingency conditions | External shock | 2-level multi-stage stochastic optimization | IEEE 33-bus and123-bus test systems |

| [60] | BESS | To minimize planning and operation cost, cost of ENS and DN reconfiguration, and the proposed RI | RI is based on the supplied active power and the priority of loads | Extreme winds | 3-level optimization problem | 138-bus distribution test network |

| [98] | BESS | To minimize investment and operation cost | Unsupplied load, critical load shedding | Natural disasters | 3-stage optimization model for min-(max-min)-(max-min) mixed-integer programming (MIP) | IEEE 33-bus and 135-bus test systems |

| [99] | BESS | To minimize cost and maximize resilience | A daily resilience metric | Extreme weather events | Convex stochastic optimization with chance constraints | A substation in Finland |

| [102] | ESS | To maximize the restored load | The ratio of restored loads to the total system demand during the study period | Natural disasters | MILP,a two-level DRL | Modified IEEE 37- bus and 123-bus networks |

| [103] | BESS (Lead-Acid Battery) | To minimize investment and operation cost, and maximize resilience | Expected energy not supplied (EENS) | Extreme events | MILP | IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [104] | BESS | To minimize energy mismatch between resources and loads | Apparent power resiliency metric | Natural disaster | MILP | IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [61] | BESS | To minimize investment and operation costs | Energy not served | Windstorms | Stochastic MILP | Modified IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [105] | BESS and EVPs | To minimize investment and operation cost | Power curtailment cost, reduced load shedding | Natural disasters | Stochastic MILP | IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [106] | BESS | - | MRI assesses the MG’s ability to recover from interruptions | Forced outages | - | A proposed MG model |

| [107] | BESS | To minimize the operating cost of VPPs and ENS | Reciprocal of the system’s loss (0 to infinite) | Severe weather events | Two-stage stochastic optimization | IEEE 85-bus radial DS |

| [108] | BESS | To minimize water and energy demand curtailment | Energy curtailment cost | Extreme weather | MINLP model reformulated as a MISOCP model | IEEE 33-bus DN |

| [109] | SC | - | The modified short-term RI involving deviation in stored energy of DC-link capacitor due to deviation in DC-link voltage | Severe weather conditions | - | An autonomous DC MG |

| [110] | HSS | To minimize normal and resilience costs | Downside risk mean value ($) | Natural disaster | MILP | IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [111] | BESS | - | Black start capability | - | - | A 5.5 MVA hydropower generator in rural power system, USA |

| [112] | BESS | To maximize resiliency, emphasizing critical loads, and minimizing generation capacity requirement | Served critical load | Natural Disasters | MILP | IEEE 37-bus and IEEE 123-bus test systems |

| [113] | BESS | To minimize operational cost | Cost of load shedding | Natural disaster | Two-step optimization, MILP | A 33-bus MG |

| [87] | EES-TES-CES | To minimize planning and operation cost | Forced load shedding (FLS) | Emergency conditions (Islanding, outages) | MINLP | A generic EH |

| [88] | EES, TES, CES | To minimize operation cost | Cost of load shedding | Extreme weather | MINLP | IEEE 33-bus DS |

| [89] | HSS-TES-BESS | Minimize planning and operation cost | LPSP, Cost of load shedding | Plateau climatic conditions | MINLP reformulated as MILP (Via Data-driven linear regression) |

A real-world rural energy system in Southwestern China |

| [90] | Integrated ESSs | Minimize planning and operation cost | Load shedding cost | Hurricane | An SDRO model reformulated as three-level min-max-min model |

IEEE 33-bus DS |

| [91] | HSS-EES-TES | Minimize planning and operation cost | Cost of load shedding | Hurricanes | A two-layer capacity configuration optimization model | A typical electrothermal hydrogen-IES |

| Ref | Mobile Energy Resources (MERs) | Objective | Resilience Index/ Resilience Metric |

Event | Optimization Model/ Formulation |

Test System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [122] | MESS | - | Expected load not supplied (ELNS) | Hurricane | Stochastic MILP | IEEE 24-bus DN with industrial EHs containing combined heat and power (CHP) units |

| [115] | Rail-based MESS | To minimize power generation cost, mobile battery degradation and transportation cost, and load shedding cost | EENS | Hurricanes | Two-stage robust resilient UC | IEEE RTS-79 with a 6-node railway network |

| [118] | Rail-based MESS (Sodium Sulphur battery) | To minimize the cost of load shedding | Cost of load shedding | Typhoon | Two-stage robust UC | IEEE RTS-24 and 118 bus systems |

| [121] | Hydrogen vehicles as MESS | To minimize power loss, operation and load shedding cost | Cost of load shedding | Typhoons | MILP | IEEE 33-bus DN |

| [125] | MESS and MEG | To minimize investment cost and cost of interruption, minimize expected loss of load | Loss of load | Earthquake | Risk-averse two-stage stochastic bi-level programming | IEEE 37-node test feeder and IEEE 123-node test feeder |

| [120] | EVs as MESS | To minimize operating and shut down cost | EENS | Floods and earthquakes | Hybrid stochastic-robust approach | IEEE 69-bus test system |

| [126] | MESSs and UAVs | To minimize investment and operation cost | Cost of load shedding | Earthquake | Multi-period distributionally robust resilience enhancement model | IEEE 39-bus TS and three modified IEEE 33-bus DSs |

| [72] | MESS (Vehicle-mounted BESS) | To minimize normal and emergency operation cost | Cost of load shedding | Floods | A bi-stage stochastic MISOCP | 15-bus, 33-bus, 85-bus DS |

| [127] | EVs as MESS | To minimize cost of load shedding, EV battery degradation cost, and monetary incentive to EV owners for emergency service relocation | Cost of load shedding | Wildfires | MIP, GCNs for predicting binary values for MIP | MMG community |

| [128] | MESS (BESS) | To minimize the conditional value-at-risk (CVaR) of future costs, shortfall, and unserved energy during storm | Unserved energy | Winter storms | 3-stage stochastic MILP | Texas-focused case study based on the ACTIVS 2000-bus synthetic grid |

| [123] | MESS-MEG | To maximize load restoration, minimize fuel cost, minimize battery aging cost | Load restoration | Extreme weather event | MIQCP | 15-bus DS |

| [124] | EVs as MESSs | To minimize operational cost and maximize resilience | RI calculated by using the survived load without EVs and survival load with EVs | Natural Disasters | MILP | An MMG system |

| [129] | MESSs | To minimize operational cost and maximize critical load restoration | 4 resilienceIndices: WRAP | Extreme weather events | A two-stage MIP model | IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [130] | MESS | To minimize power loss | A multi-stage event-based system resiliency index | Extreme events | Nonlinear programming | PG & E 69-bus MMG power DN |

| [131] | MESS | To maximize self-healing index, minimize allocation cost for MESSs, minimize unserved load | Self-healing index and coordinated gain index | External shocks | MILP | IEEE 123-bus test system |

| [119] | PEVs as MESSs | To minimize operating cost of networked MEMGs | Resilience enhancement factor | Extreme events | Stochastic hierarchical EMS optimization | 4 MEMGs |

| [74] | MESS | To minimize cost of load shedding and power mismatch between MGs | Cost of load shedding, critical load shedding, total load shedding | Extreme events | A three-stage stochastic optimization formulated as MILP | NMGs |

| [117] | MESS (Truck-mounted BESS) | To minimize operation cost | Load shedding cost | Extreme events | 2-stage MILP | IEEE 33-bus DS |

| [132] | MESS | To minimize load loss and voltage offset | Loss of load | Extreme events | Bilevel optimization, MILP | Modified IEEE 33-bus DS |

| [133] | MESSs and PEV-Parking Lots | To minimize operation cost | Interruption cost | Extreme events | MIQCP | IEEE 33-bus DS |

| [134] | MESSs, MEGs, Portable renewable generators | To minimize operation cost | ENS | Natural catastrophe | MILP | A typical 10-bus MG |

| [135] | MESS | To minimize operational cost | Load shedding cost | Extreme events | MILP | Modified IEEE 69-bus, 24-node Sioux Falls’ TN |

| [73] | BEBs as MESSs | - | Loss of load | Fault event | - | 20 MW-class MG at University of California Irvine |

| [136] | MESS | To minimize investment and operation cost | Load loss rate (LLR), cost of load shedding | Extreme weather events | A two-stage stochastic mixed-integer programming (SMIP) | Modified IEEE 33-bus, IEEE 123-bus test systems |

| [137] | MESSs | To minimize outage duration and operation cost | Load shedding | Natural disasters | Two-stage optimization, MILP | IEEE 33-bus and 69-bus DN |

| [138] | MESS | To maximize DS resilience and minimize degradation cost | Load interruption cost | Extreme event | MILP | IEEE 33-bus and 118-bus test systems |

| [139] | MMESs | To minimize operation cost | Customer interruption cost | Large area disaster | MILP | Modified IEEE 33-bus test system |

| [140] | MESSs | To minimize pre-allocation cost for MESSs, minimize MESS scheduling cost, and cost of load shedding | Load shedding cost | Extreme natural disaster | RO-MILP | IEEE 33-bus DN |

| [141] | MESSs (Truck-mounted BESSs) and EVs | To minimize pre-allocation cost for MESSs, minimize loss of load | Loss of load | Extreme weather event | RO-MILP | IEEE 33-bus and IEEE 141-node test systems |

| [142] | EVs as MESS | To maximize RI, reliability index, stability index, minimize emission index | Reciprocal of the system’s loss performance | Extreme weather conditions | Weighted sum multi-objective optimization model (Nonlinear programming) | IEEE 34-bus and Indian 52-bus radial DSs |

| Ref. | ESSs | Objective | Resilience Index/ Resilience Metric |

Event | Optimization Model/ Formulation |

Test System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [145] | SMI-BESS | To minimize investment and operation cost under normal and extreme weather | Load loss | Strong wind, hail, lightning | 2S-ADRO with max-min optimization formulation | 62-node and 25-node DNs in the SCW area of the southeast coast of China |

| [116] | SESS and truck-mounted BESS | To minimize the weighted ENS index and total investment cost | Weighted ENS | Severe climate phenomenon | Nonlinear programming | Three adjacent geographical zones each comprising four sub-areas. |

| [146] | BSS, mobile diesel generator, MESS | To minimize load shedding and operational costs | Loss of load | Wildfires | MINLP | Modified IEEE 38-bus and IEEE 123-bus balanced DNs |

| [148] | BESSs, MESSs, MEGs, and EVs | To maximize the total weighted sum of the supplied electric and thermal load | Total load served | Natural disasters | MILP | Multi-energy DS (modified IEEE 33-bus DN and a 20-node heat network), a real-scale Southern California Edison 56-bus DN |

| Ref. | HESS | Objective | Resilience Index/ Resilience Metric |

Event | Optimization Model/ Formulation |

Test System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [153] | SMES-BESS | To minimize DC-bus voltage deviation | DC-bus voltage stability | Unplanned MG operation mode switching, short circuit fault in the utility grid | MPC for sharing power between ESSs | A DC MG |

| [154] | A-CAES-BESS | To minimize investment and operation cost | LPSP | Extreme weather events | A two-stage optimization model | A university building in Montreal, Canada having building-integrated PV-based energy systems |

| [156] | HSS- BESS | To minimize operation cost | A formula of RI based on load loss | Extreme events | MILP | Modified IEEE RTS-96 |

| [157] | HSS-BESS | To minimize operation costs | Blackout time | Extreme weather events, typhoons, and wildfires | Second-order cone programming (SOCP) | IEEE 123-bus test system |

| [158] | EES and HSS | To minimize operation cost | Ratio of supplied load to total demand, FLS | Emergency conditions (Line outage, islanding) | A decentralized two-layer framework based on RO, MILP | 118-bus AND having four MGs |

| Ref. | Resiliency Index (RI) Definition | Range | Storage Type | Impacts of ESSs on Resiliency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [93] | A function of timely awareness capability regarding the event occurrence (ϑ), FI, REI, MVI, and LLI. | For sufficient resilience, FI, MVI, and LLI should be near to 0, and REI should be close to 1. | BESSs and EVPs | EVPs and ESSs reduce load curtailments and thereby improve MG resilience. They can serve as redundant resources, thereby enhancing REI. |

| [65] | The ratio of energy served during emergency response time to the expected energy demand. | 0 to 1. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS and EVs | Energy Storage Units are used for optimal hardening of the grid that provides effectual capacity addition to enhance RI |

| [86] | ALOL | 0 to 100%. | BTM-ESS (Battery and EV) | Optimal operation of BTM-ESS recovers some/all parts of critical loads to enhance RI |

| [99] | The dependency index is used as the RI. It is an index that means ‘‘a linkage or connection between two infrastructures, through which the state of one infrastructure influences or is correlated to the state of the other.’’ | 0 to 1. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | Day ahead scheduling of BESS is used for outage prevention which is directly related to enhancing RI (the withstanding capacity of the grid) |

| [59] | The ratio of power injection by the total number of batteries to the total demand for critical loads. | 0 to 1. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | BESSs are placed optimally to curtail less critical loads which maximizes RI. |

| [97] | The ratio of the total served load in contingency conditions and the difference between the total served load in normal conditions and the total served load in contingency condition | 0 to infinity. A higher value represents better resiliency. | PHEVs, EES and TES | PHEVs, EES, and thermal storage increase the served loads in contingency conditions which directly enhances RI. |

| [57] | The ratio of energy served during emergency response time to the expected energy demand. | 0 to 1. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | BESSs with other local resources are rescheduled to serve maximum loads during emergency response which directly enhances RI. |

| [94] | Resilience score is based on the node voltage deviation, fault recovery rate and network loss rate. | 0-to-100-mark system. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | BESS improves fault recovery performance that increase resilience score |

| [106] | MRI assesses the MG’s ability to recover from interruptions | 0 to 1. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | BESS integration reduces outage hours and lost energy that significantly improves MRI. Larger BESS provides higher MRI. |

| [102] | The ratio of restored loads to the total system demand during the study period | 0% to 100%. A higher value represents better resiliency. | BESS | Optimal scheduling of ESS maximizes the restored load, thereby enhancing RI. |