1. Introduction

Throughout the years, humankind has discovered the power of advanced technologies to improve production and efficiency. Since the first Industrial Revolution (Industry 1.0), people have used technologies as a medium of advancement. For example, they used technologies to improve mechanical power in the 1780s using resources like steam, water, and fossil fuels [

1]. During Industry 2.0 in the 1870s, manufacturers began to explore electrical energy to power mass production and assembly lines. Industry 3.0 in the 1970s, they began integrating information technologies (IT) and electronics to facilitate automation in production facilities. This development was then advanced in Industry 4.0, when the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing, and the Internet of Things (IoT) was realized. This led to the creation of smart cyber-physical systems (CPS), which connect the physical and virtual worlds in real-time [

2]. As a result, Skobelev and Borovik [

3] define Industry 4.0 as “as means to achieve a competitiveness of the industry through the reinforced integration of ‘cyberphysical systems’ (CPS) into productions” (p.307). This integration resulted in Cyber Physical Production Systems (CPPS), where machines can make intelligent decisions through advanced cooperation between manufacturing technologies and real-time communication systems.

Despite the rapid technological advancements discovered during Industry 4.0, the concept failed to account for the role of human resources. Skobelev and Borovik [

3] found that this period focused primarily on changes in human labor, causing significant dissatisfaction. The authors found that “the world of work in Industry 4.0 will still be inconceivable without human beings” (p.307). The need to determine how these technologies benefit people and society has led to the emergence of Industry 5.0. Xu et al. [

2] describe Industry 5.0 as a period that recognizes “the power of industry to achieve societal goals beyond jobs and growth, to become a resilient provider of prosperity” (p.530). This is achieved by ensuring that the production systems place the well-being of the industry worker, society, and planet at the center. The Industry 5.0 concept is based on the assumption that Industry 4.0 focused on digitization and paid less attention to humankind and the environment. Thus, Industry 5.0 aims to promote balanced development that respects environmental boundaries and upholds principles of social fairness and sustainability.

This systematic bibliometric literature review (LRSB) synthesizes findings from 53 sources on the ongoing transition from Industry 4.0 to 5.0. It explores both industrial revolutions, driving factors, and technologies, including the role of AI, optimization, and human values.

2. Materials and Research Methods

The researcher conducted a systematic bibliometric literature review (LRSB) using the PRISMA 2020 framework to identify and screen literature. These approaches ensure a rigorous and transparent process for identifying, selecting, and evaluating relevant academic literature. For instance, Linnenluecke et al. [

4] explain that LRSB minimizes bias through exhaustive literature searches that include a replicable, scientific, and transparent process. Utilizing the PRISMA 2020 framework helps improve the quality of the findings synthesized [

5]. Haddaway et al. [

6] indicate that the PRISMA model helps “ensure that the methods and results of systematic reviews are described in sufficient detail to allow full transparency.” The structured, replicable format supports comprehensive knowledge mapping in interdisciplinary domains such as artificial intelligence and industrial transformation.

As outlined by Rosário et al. [

7] and further expanded upon by Rosário [

8], the LRSB technique delivers a more methodical and in-depth examination of a given research field than what is typically found in standard literature reviews. A central focus of this method lies in the deliberate and precise selection of studies that “directly address the research question,” all while upholding a strong commitment to transparency. This structured rigor enables comprehensive scrutiny of each study’s approach, outcomes, and overall integrity.

The LRSB strategy operates through a systematic, protocol-driven framework designed to govern the identification and assessment of relevant sources. This framework is intended to bolster both the trustworthiness and significance of the information gathered. As illustrated in

Table 1 and explained in more detail by Rosário et al. [

7] and Rosário [

8], the methodology unfolds in three distinct stages, each comprising two specific steps.

The investigation relied on the Scopus database as the primary tool for identifying and selecting reputable academic sources, capitalizing on its recognized status within scholarly and scientific circles. The selection process was coupled with a thorough assessment of each study’s quality to ensure methodological soundness.

The decision to use Scopus exclusively in conducting the literature review is grounded in its extensive coverage, rigorous indexing standards, and advanced analytical features. Recognized as one of the most expansive and authoritative abstract and citation databases for peer-reviewed work, Scopus encompasses a broad range of disciplines. Its inclusion of journals, conference papers, and academic books from well-established publishers contributes to the scholarly rigor of the sources. Additionally, Scopus provides powerful capabilities such as citation analysis, bibliometric evaluations, and keyword mapping, all of which facilitate detailed examinations of research trajectories, author influence, and thematic evolution—critical elements for conducting a structured and data-rich literature review. The database’s use of standardized metadata and consistent indexing protocols further supports the dependability and reproducibility of the search process, making it especially apt for systematic and thematic investigations. For these reasons, relying on Scopus strengthens the integrity and coherence of the review process.

However, the exclusive dependence on Scopus is not without its drawbacks. Although it offers broad and high-quality coverage, this single-source approach can introduce certain limitations. For example, it may under-represent works published in specific regions, languages, or specialized domains, potentially resulting in “a twisted global perspective.” Similarly, an emphasis on frequently cited publications might inadvertently marginalize innovative or divergent research, while delays in indexing newly released materials could affect the review’s up-to-dateness. Hence, while Scopus serves as a solid foundation, it is essential to recognize its constraints to foster a more balanced and comprehensive view of the research field.

Furthermore, the scope of the search was limited to materials published up to April 2025, possibly excluding the most current findings. To maintain scholarly rigor, the review was confined to academic and scientific sources that had undergone peer-review, ensuring credibility and academic precision throughout.

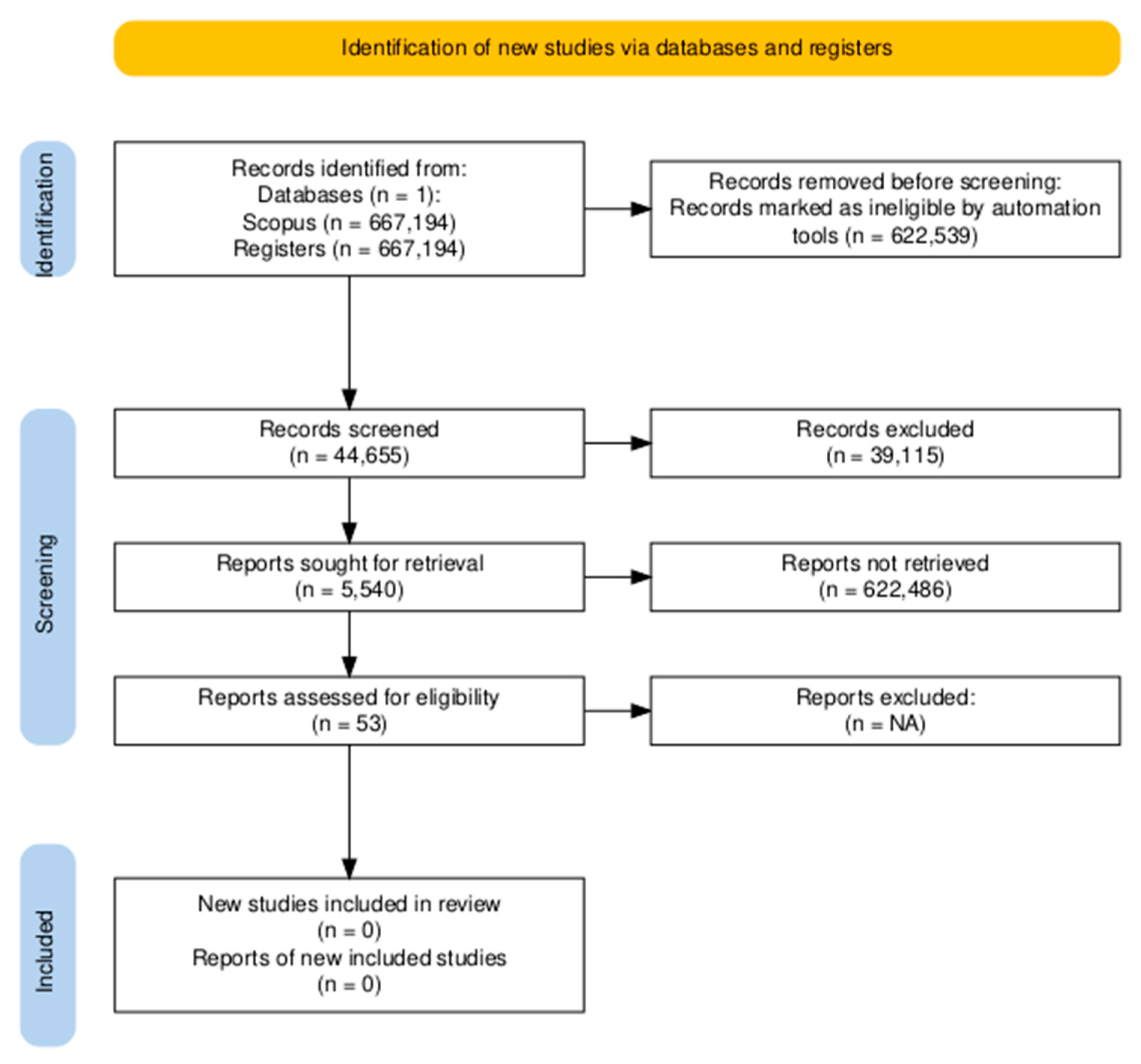

The initial query, TITLE-ABS-KEY “artificial intelligence”, yielded 667,194 documents. Then the keyword “Industry” was added to narrow the scope, reducing the pool to 44,655 papers. Further inclusion of the keyword “Industry 4.0” identified 5,540 relevant entries. However, the researcher intended to target the conceptual transition to Industry 5.0. Thus, the search was refined to include the keyword “Industry 5.0”, resulting in 376 documents. Finally, to emphasize the integration of AI in applied contexts such as smart manufacturing, the filter EXACTKEYWORD “Smart Manufacturing” was added. This narrowed the final dataset to 53 documents (N=53). This procedure ensures that the reviewed literature addresses the intersections of AI, industrial evolution, and value-driven innovation.

To uphold both the relevance and academic integrity of the materials considered in the final analysis, the research adopted a set of explicit inclusion and exclusion parameters (

Table 2). The review centered solely on peer-reviewed journal publications that explored the application of artificial intelligence to “enhancing marketing within a business context.”

In order to maintain a focused and coherent dataset, any works that did not directly pertain to artificial intelligence were systematically excluded. This methodical filtering ensured that the selected literature was not only of high academic quality but also directly aligned with the core aims of the research.

Further details outlining the search and selection methodology are presented in

Table 2.

A detailed content and thematic examination was undertaken by the researchers, employing the analytical structure proposed by Rosário et al. [

7], as well as Rosário [

8]. In order to include only sources of strong academic merit and direct relevance, the study applied stringent selection standards throughout the review process. The investigation focused on literature addressing themes such as AI, Optimization, and Human Values: “Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Industry 4.0 to 5.0,” with preference given to research that demonstrated close alignment with the study’s core objectives.

Each selected work was scrutinized for relevance, methodological soundness, and confirmation of peer-review publication status. The search for relevant keywords was conducted through a process of iterative refinement, employing Boolean operators to strike a balance between breadth and precision in the retrieved results.

By following this deliberate and filtered methodology, the resulting dataset was both academically rigorous and precisely attuned to the aims of the research. A diagrammatic overview of the selection process is illustrated in

Figure 1.

In total, 53 scholarly and scientific publications retrieved from the Scopus database were analyzed through a blend of narrative techniques and bibliometric evaluation, adhering to the methodological framework outlined by Rosário et al. [

7] and Rosário [

8]. This dual-method approach facilitated an in-depth exploration of the material, emphasizing the discovery of “recurring themes and ensuing key findings” that were closely tied to the study’s central research questions.

Of the 53 documents selected, 25 were conference papers, 23 articles, and 5 Book chapters

In total, 53 scholarly and scientific publications retrieved from the Scopus database were analyzed through a blend of narrative techniques and bibliometric evaluation, adhering to the methodological framework outlined by Rosário et al. [

7] and Rosário [

8]. This dual-method approach facilitated an in-depth exploration of the material, emphasizing the discovery of “recurring themes and ensuing key findings” that were closely tied to the study’s central research questions. Of the 53 documents selected, 25 were conference papers, 23 articles, and 5 Book chapters.

3. Publication Distribution

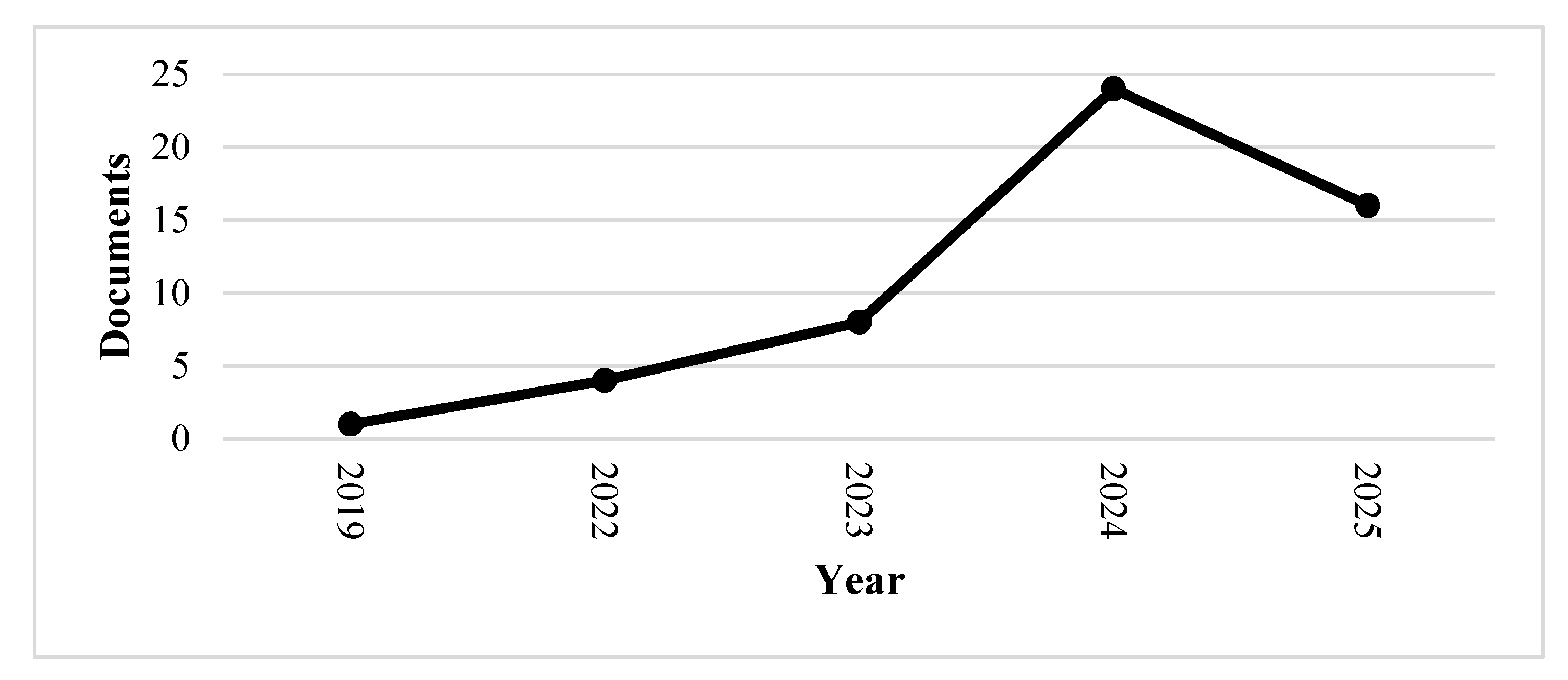

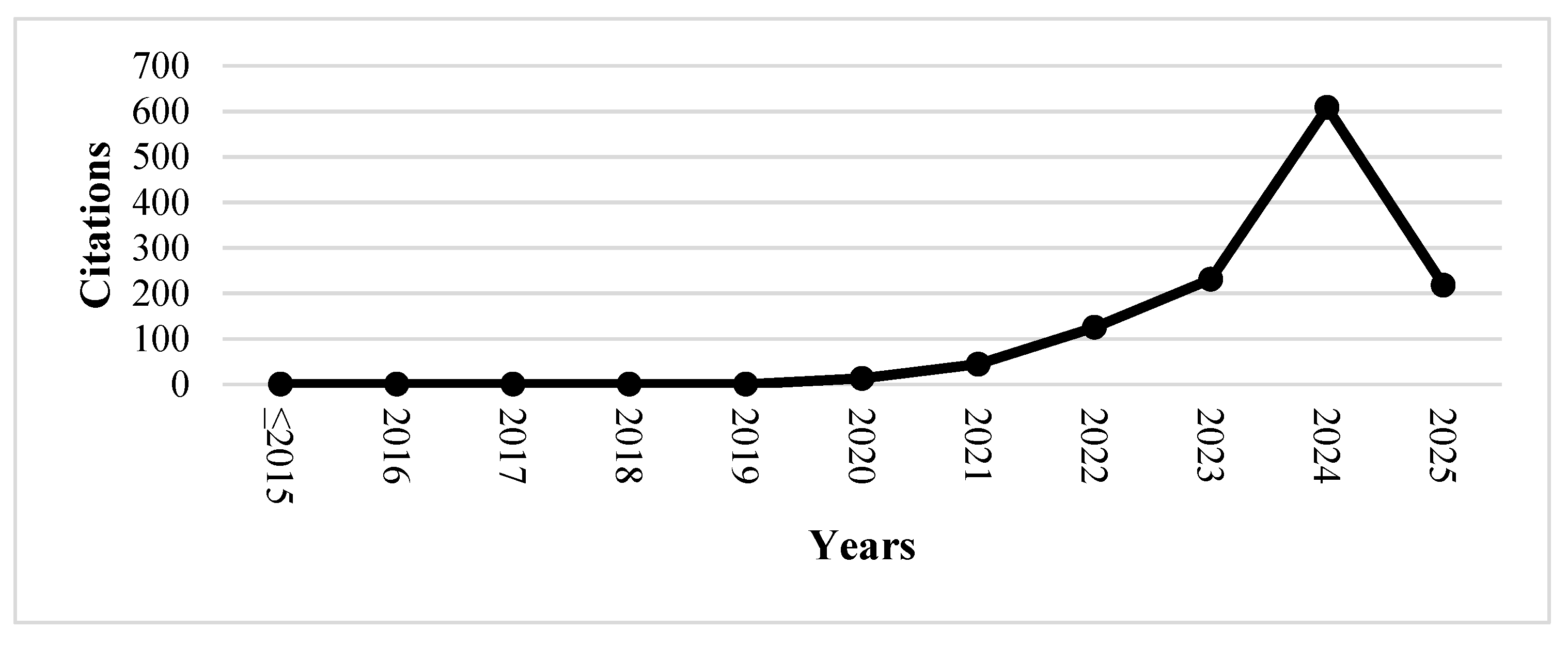

This part highlights the key themes and important terms that surfaced during the initial analysis. It draws from peer-reviewed studies focused on “AI, Optimization, and Human Values: Mapping the Intellectual Landscape from Industry 4.0 to 5.0,” covering research published up to April 2025. Notably, 2024 saw the greatest volume of peer-reviewed work in this area, with 24 publications. A summary of the literature up to April 2025 is illustrated in

Figure 2.

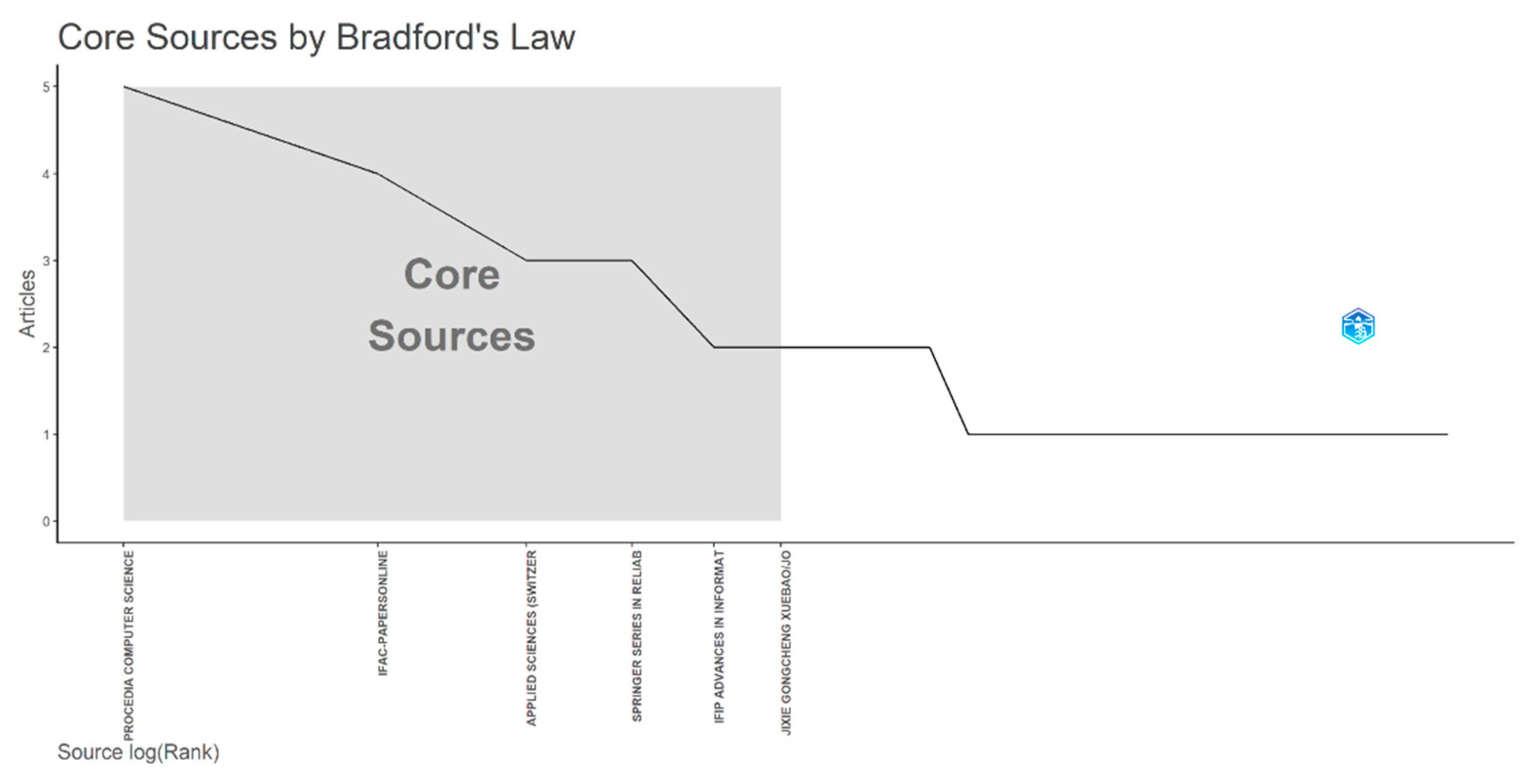

The publications were sorted out as follows: Procedia Computer Science (5); IFAC Papersonline (4); Springer Series In Reliability Engineering (3); Applied Sciences Switzerland (3); with 2 publications (Procedia CIRP; Lecture Notes In Networks And Systems; Journal Of Cleaner Production; Jixie Gongcheng Xuebao Journal Of Mechanical Engineering; IFIP Advances In Information And Communication Technology); and the remaining publications with 1 document.

The steady climb in publication numbers between 2022 and 2024 shows how academic interest in artificial intelligence and related technologies has gathered momentum, with a particularly sharp rise starting in 2024. Several factors have driven this growth: rapid advancements in technology, greater funding opportunities, a stronger institutional push toward digital innovation, and the swift integration of AI into everyday life. Moreover, the spread of AI into areas like healthcare, marketing, business, optimization, and the study of human values has drawn in researchers from a variety of fields, widening the conversation around AI. Together, these developments highlight how the field has grown from a budding interest into a well-established and influential area of academic study. It’s also important to note that the apparent decline in 2025 publications stems simply from the fact that only research between January and April was considered.

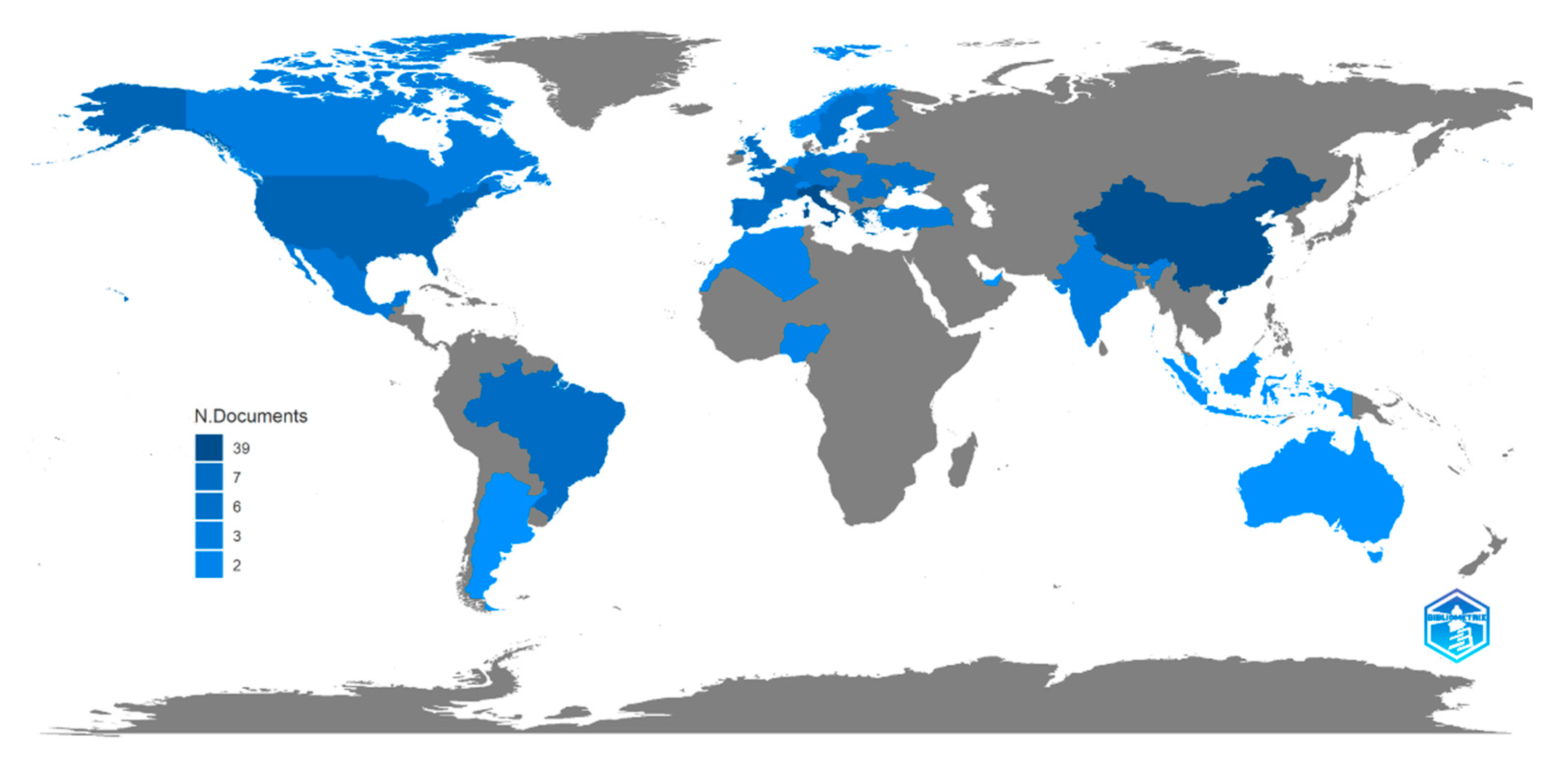

In contrast,

Figure 3 showcases the countries that have made the most significant scientific contributions within specific research areas. Italy, China, Slovenia, and Greece emerge as the top contributors, distinguished by their high volume of publications. Their strong presence in the research landscape highlights the important role these nations play in pushing forward advancements and expanding knowledge within their respective field.

Table 3 and

Figure 3 illustrate the top 10 countries leading research efforts in the fields under study. A closer look at the global spread of research on the integration of AI, Optimization, and Human Values — particularly within the context of Industry 4.0 and 5.0 — reveals that Italy, China, Slovenia, Greece, and several others have made notable contributions. This widespread engagement reflects growing international momentum, fueled by rapid technological progress, heightened investments in digital innovation, and rising demand for smart solutions tailored to Industry 4.0 and 5.0 environments. The active participation of both developed nations and emerging economies like Brazil highlights the strategic importance of this research area, as industries and institutions worldwide increasingly adopt intelligent technologies. Altogether, the findings point to a vibrant and evolving research landscape shaped by the intersection of technology, economic policy, and global market needs. This study also sheds light on the countries prioritizing intelligent Industry 4.0 and 5.0 solutions, offering a window into their academic and research agendas.

Expanding on the most influential contributors, Bradford’s Law points to six major publications — shaded in grey in

Figure 4 — that form the core sources within the field, together representing 11% of the total scientific output. According to this principle, when a new research topic begins to attract attention, a small cluster of journals tends to publish the majority of early work. These journals temporarily dominate the landscape until interest spreads and more publications begin covering the topic. Over time, a central group of journals emerges as the primary platforms for scholarship in the area. Within this group, three journals stand out in particular, with the first three publications becoming especially critical to the field’s development. These journals not only anchor scholarly discussions but also serve as key hubs where researchers connect, reference one another’s work, and drive the collective advancement of knowledge.

The subject areas represented in the 53 academic documents reflect a strong inter-disciplinary foundation, with the most relevant contributions coming from Engineering (37); Computer Science (34); Mathematics (10); Physics and Astronomy (6); Decision Sciences (6); Business, Management and Accounting (6); Materials Science (4); Energy (4); Chemical Engineering (4); Social Sciences (2); Medicine (2); Environmental Science (2); Arts and Humanities (2); Chemistry (1); and Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology (1), further underscore the growing interest in the AI, Optimization, and Human Values of Industry 4.0 to 5.0.

The most cited work within this body of literature is the article titled ‘Industry 5.0 and Human-Robot Co-working’, which has received 504 citations. Published in the Procedia Computer Science, a journal with no ranking assigned yet journal with an SJR of 0,47 and an H-index of 152, this article serves as a pivotal reference in the field. Its primary aim is to deliver a comprehensive study on the possible issues related to collaborative work between humans and robots from the organizational and human employee perspective.

In

Figure 5, we can analyse citation changes for documents published until April 2025. The period ≤2015-2025 shows a positive net growth in citations with an R2 of 52%.

Figure 5 citation changes for documents published until April 2025

The h-index serves as a way to gauge both the influence and productivity of research work. It is determined by finding the highest number of publications that have each been cited at least that same number of times. In the analysis carried out, 25 documents satisfied this standard, with each receiving at least 10 citations. This metric offers a window into the impact and visibility of research within its field. Altogether, citations for all scientific and academic documents published up to April 2025 amounted to 1,240 (

Appendix A), although it’s worth noting that 25 out of 28 documents had not yet received any citations.

A particularly influential piece, Industry 5.0 and Human-Robot Co-working, has emerged as a cornerstone in its field, as shown by its consistently rising citation numbers. Published at a crucial time when interest in AI and human values was gaining momentum, its strong impact can be credited to a rigorous methodological approach. The study combined bibliometric analysis, conceptual mapping, and intellectual network analysis to chart key developments. It successfully brought together fragmented strands of research, outlined major thematic clusters, and suggested future directions, establishing itself as an essential reference for scholars. Its appearance in a prestigious journal further boosted both its visibility and academic weight, helping explain its widespread citation across multiple disciplines. Additionally, the R² value presented in the corresponding figure — measuring the regression trend between publication year and citation growth — stands at 0.520. This indicates a strong, predictable linear rise in citations over time, underscoring the article’s growing influence and lasting relevance in the field.

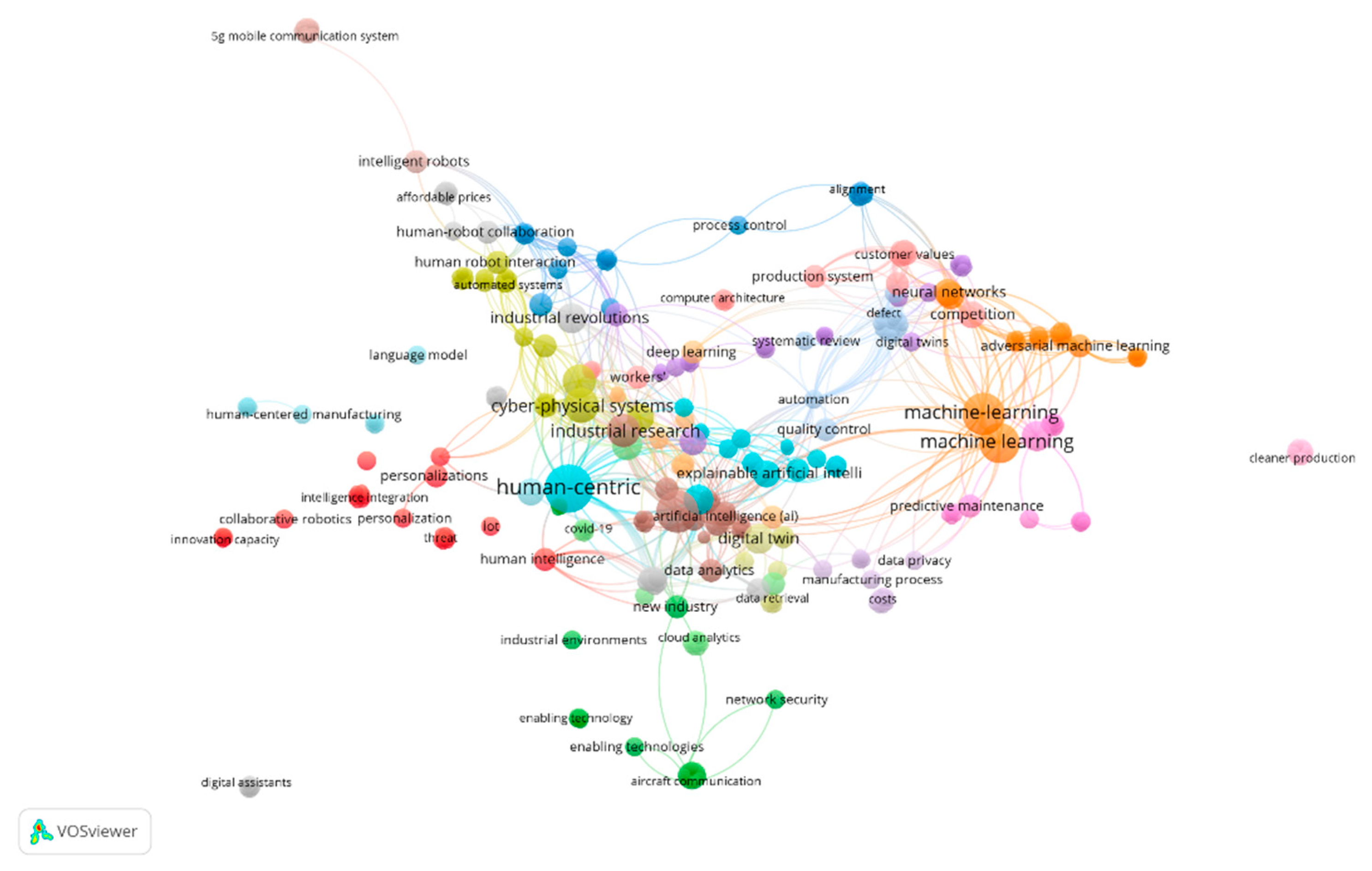

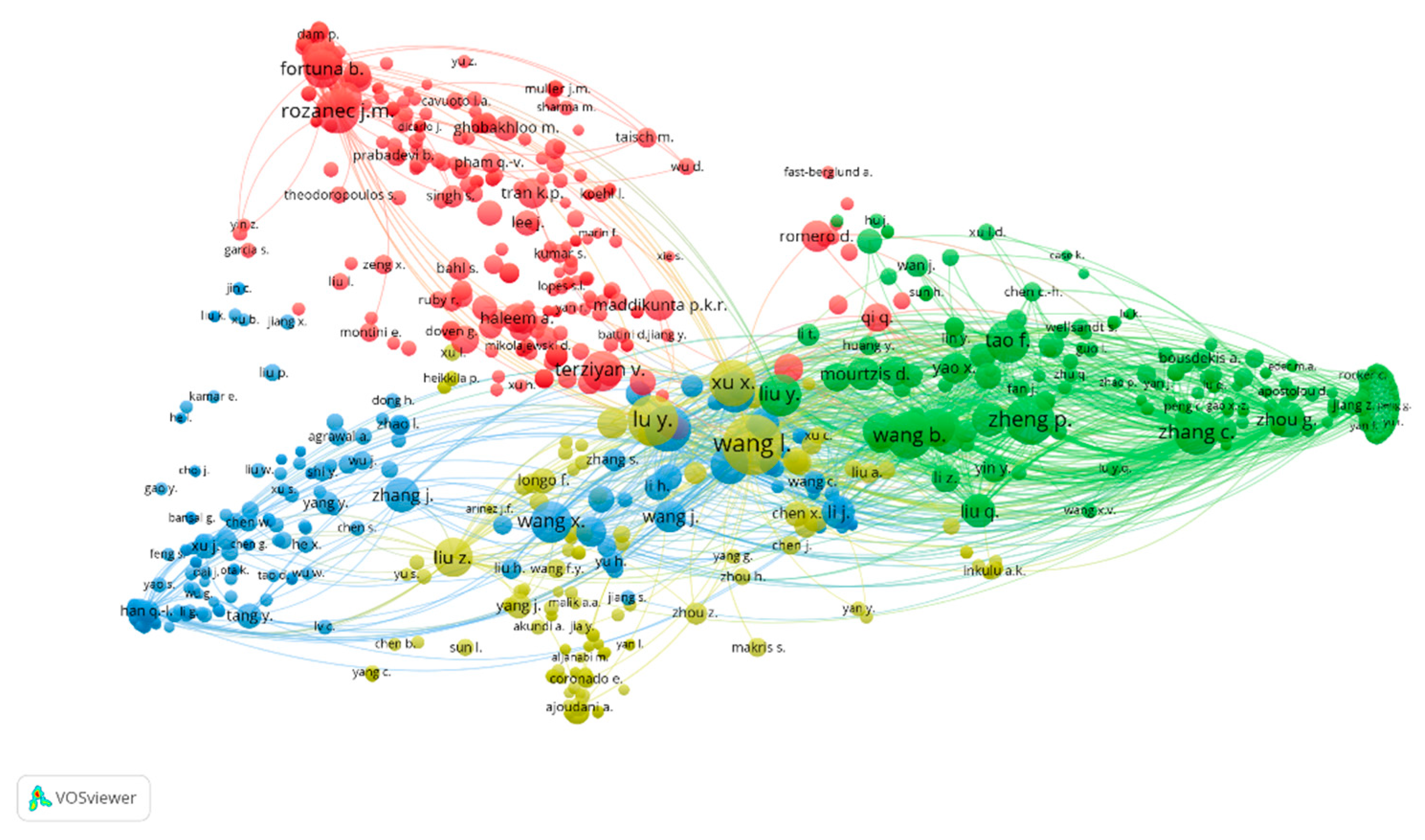

In addition, by applying the main keywords ‘AI, Optimization, and Human Values: Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Industry 4.0 to 5.0’, the bibliometric analysis shed light on key research trends and emerging indicators, as depicted in

Figure 6. These insights were derived using VOSviewer software, focusing specifically on primary search terms such as ‘artificial intelligence,’ ‘industry,’ ‘industry 4.0,’ ‘industry 5.0,’ and ‘smart manufacturing’.

The keyword co-occurrence network uncovers how research around AI, optimization, and human values is largely anchored in major technological themes, particularly the mapping of the intellectual evolution from Industry 4.0 to 5.0 — the core focus of the field. Surrounding clusters shed light on the practical applications of these concepts, particularly in areas like smart manufacturing and next-generation industrial solutions.

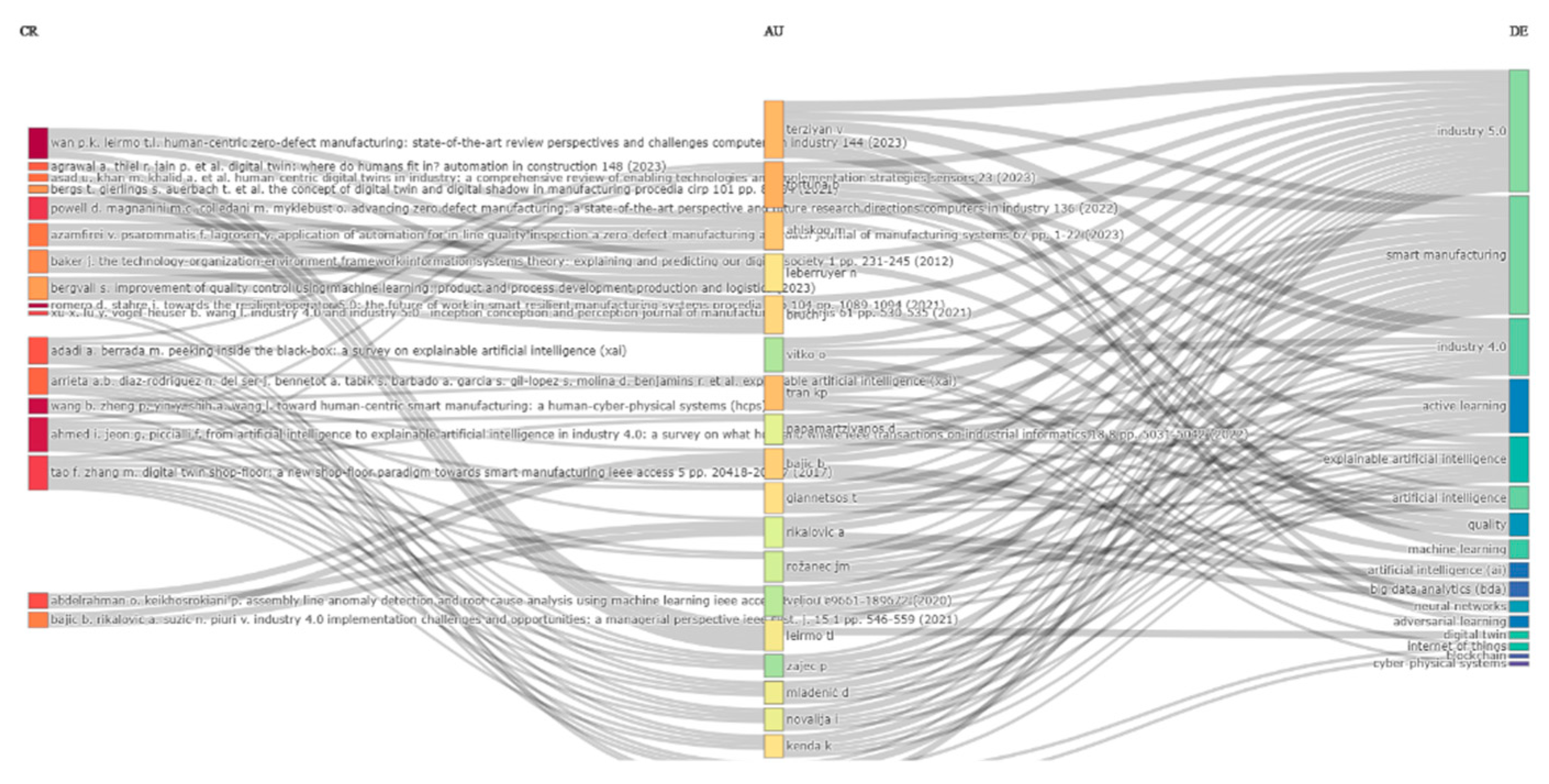

This study draws on a thorough review of academic and scientific literature that explores how AI, optimization, and human values are shaping the intellectual landscape between Industry 4.0 and 5.0. A three-field plot centers on the main area of study, where ‘AU’ stands for authors, pointing to the principal researchers involved, while also illustrating their links with ‘CR’ (cited references) and ‘DE’ (author keywords). To better understand how key terms interrelate across the examined studies, a network diagram was generated using Bibliometrix software.

Figure 7 offers a visual snapshot of these connections, clearly mapping how significant ideas and research directions are intertwined within the field.

The Sankey diagram offers a visual snapshot of theme frequency, with the size of each box representing how often a topic appears, while the connecting lines illustrate the relationships and transitions between them. The thickness of these lines signals the strength of the connection, showing how closely different themes are related. As Xiao et al. [

9] describe, this method provides a clear way to trace the flow and development of major topics throughout the analysis. In

Figure 7, the most prominent keywords include “industry 5.0” (with 20 incoming flows and no outgoing flows), “smart manufacturing” (15 incoming flows and no outgoing flows), and “industry 4.0” (11 incoming flows and no outgoing flows). These keywords are closely associated with the most highly cited references in the field.

In conclusion, the three-field plot captures the intellectual framework of research on AI, Optimization, and Human Values: Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Industry 4.0 to 5.0 by illustrating the connections between cited references, leading authors, and major research themes. The strong alignment between key references and keywords points to a field that remains closely centered on these core topics. However, the relatively sparse appearance of regulatory and theoretical terms hints at areas that have yet to be fully explored, signaling promising directions for future research aimed at deepening both the conceptual and societal understanding of the field.

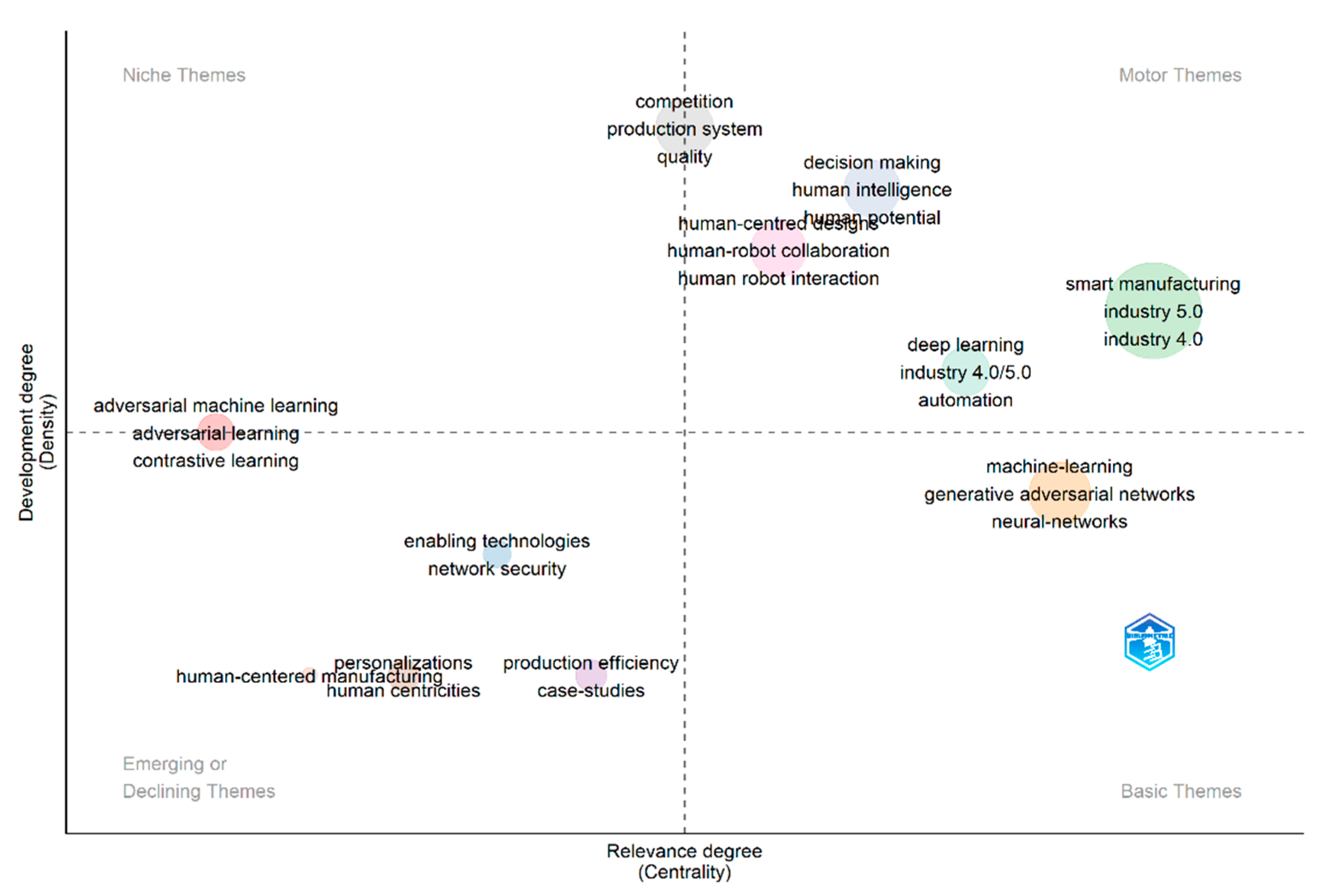

Figure 8 provides a detailed visual map of the relationships between major terms appearing in the academic literature, showcasing how frequently used keywords are interconnected. This analysis sheds light on the core themes that researchers have been exploring and points to potential directions for future inquiry. Alongside this, the figure reveals a wide network of co-citations and thematic groupings, offering deeper insight into citation patterns and reinforcing the overall conclusions drawn from the study.

The thematic map was developed based on defined parameters, including a minimum cluster frequency of 50 per thousand documents, five labels per cluster, a label font size of 3, and a baseline scaling factor of 0.3. A dividing line on the map separates thematic relevance (centrality) from developmental progress (density). As shown in

Figure 8, the map is organized into four quadrants, each marked by colored circles representing different thematic areas. In the upper-right quadrant lie the field’s central themes—topics that are not only well-developed but also highly relevant. These areas are characterized by both strong connectivity and internal coherence, indicating their foundational role in the broader research landscape.

The bottom-right quadrant features core and interdisciplinary themes that hold substantial importance but are still in the early stages of development. These areas show high centrality but low density, highlighting their potential to shape future research directions. In contrast, the bottom-left quadrant points to topics that may be either up-and-coming or fading out, characterized by both low density and limited centrality. These could signal emerging interests or subjects that are gradually losing traction. Meanwhile, the top-left quadrant includes highly specialized topics with strong internal focus but weaker connections to the broader field. Their high density and low centrality suggest they occupy more niche or peripheral spaces within the overall research landscape.

This framework offers a clear snapshot of how various research themes are situated within the field, shedding light on both firmly established areas and those that may hold promise for future investigation.

In summary, the keyword co-occurrence map reveals a technocentric research structure, with core themes focused on “artificial intelligence, industry, industry 4.0, industry 5.0 and smart manufacturing”, indicating a strong emphasis on AI technologies, optimization and human values.

When we look at

Figure 9, which covers 53 documents, we see that on the lower right side of the axis, where the basic and cross-cutting research themes of the period in question are concentrated, “machine-learning”, “generative adversarial networks”, and “neural-networks” appear as the main themes.

On the upper right side are the driving themes of the period, in which “decision making”, “human intelligence”, “human potential”, “human-robot”, “human-robot collaboration”, and “human robot interaction” are the central themes.

On the upper left side of the axis, we see that as peripheral themes, there are “customer-service”, “inventory control”, and “inventory management”, and it can be understood that this theme is on the way to becoming an emerging or declining theme.

In the lower left corner, which corresponds to emerging or declining themes, are: “enabling technologies” and “network security”, “production efficiency” and “case studies”, which are basic and transversal themes, emerging or declining themes. Finally in the bottom right corner, basic themes “machine-learning”, generative adversarial networks”, and “neural-networks”.

Furthermore,

Figure 10 illustrates a substantial network of co-citations and interconnected units, offering a more in-depth examination of cited references. This visualization enhances the understanding of citation patterns and strengthens the overall conclusions of the study.

As shown, the co-citation network reveals a tightly knit core of influential studies that form the backbone of research on AI, Optimization, and Human Values: Mapping the Intellectual Landscape of Industry 4.0 to 5.0. These works are frequently cited together and tend to focus on common themes such as “artificial intelligence,” “industry,” “industry 4.0,” “industry 5.0,” and “smart manufacturing,” signaling a strong conceptual alignment across the field. The pattern of co-citations suggests that this is a mature and cohesive area of study, with scholars consistently building on a shared body of knowledge to develop and refine theoretical frameworks. Meanwhile, the presence of peripheral nodes hints at emerging or specialized topics, pointing to a research landscape that is both well-established and continually evolving.

4. Theoretical Perspectives

4.1. Understanding Industry 4.0

Industry 4.0, or the Fourth Industrial Revolution, marks a major transformation in industrial production systems through the convergence of digital, physical, and biological technologies. Skobelev and Borovik [

3] defined it as “an umbrella term used to describe a group of connected technological advances that provide a foundation for increased digitization of the business environment” (p.307). Similarly, De Souza et al. [

10] describe Industry 4.0 as “integrating machines and devices with sensors and related software to predict, control and plan better business” (p.145). Industry 4.0 technologies empowered companies to improve product quality and efficiency of the manufacturing processes. The Industry 4.0 concept was formally introduced during the 2011 Hannover Fair Event. It was part of the German government’s strategic initiative to enhance manufacturing competitiveness by embracing advanced digitalization. However, its roots can be traced to the technological advancements of the late 20th century, such as the rise of embedded systems and networked communication.

Industry 4.0 is distinguished from its predecessors through various advancements, including automation, computerization, emphasis on cyber-physical integration, and real-time data responsiveness. Boursali et al. [

11] explain that various changes, like increased data volumes, connectivity, and computational power, drove this development. Where Industry 3.0 focused on electronics and IT for automation, Industry 4.0 integrates these elements with artificial intelligence, sensors, decentralized decision-making, and inter-machine communication. Skobelev and Borovik [

3] further identify other components of Industry 4.0, including business intelligence capabilities, human-machine interactions, analytics, and smart manufacturing. These advancements mark a paradigmatic shift toward intelligent, adaptive systems capable of evolving autonomously within complex and volatile production environments. The transition is both technical and socio-economic, with implications for labor markets, organizational models, and global value chains. This makes Industry 4.0 a critical site for examining the interplay between technology and human values.

4.1.1. Key Components

Industry 4.0 entails several foundational components that interlink physical production with digital technologies. These elements provide the architecture through which factories and production systems become increasingly autonomous, responsive, and efficient. Their integration underpins the operational transformation that distinguishes Industry 4.0 from traditional industrial models. These components include.

4.1.1.1. Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS)

Cyber-Physical Systems represent the foundational architecture of Industry 4.0 that enables a seamless interface between the digital and physical domains. CPS are engineered systems wherein computational elements are deeply embedded into physical processes and interact with them through sensors, actuators, and control algorithms [

12]. These systems gather data and interpret and respond to environmental stimuli in real time, often with a degree of autonomy. According to Skobelev and Borovik [

3], the intelligence of CPS lies in its capacity for adaptive feedback loops by continuously analyzing, learning, and optimizing operations based on dynamic conditions. CPS in industrial applications range from precision manufacturing and energy management to robotics and supply chain coordination [

12]. They underpin the evolution from static production models to agile, self-configuring systems capable of real-time decision-making. CPS challenges traditional notions of control hierarchies by distributing intelligence across the production network, creating a decentralized and resilient operational paradigm.

4.1.1.2. Internet of Things (IoT)

The Internet of Things (IoT) serves as the connective tissue of Industry 4.0 by embedding communication capabilities into physical devices and enabling their integration into broader networks. IoT connects machines, sensors, vehicles, and even products within industrial environments [

3]. This allows for the exchange of data across the value chain. Moreover, this real-time visibility into operations facilitates predictive maintenance, adaptive resource allocation, and enhanced traceability, significantly reducing downtime and inefficiencies [

13]. IoT enables horizontal and vertical system integration from the shop floor to the cloud and from suppliers to end-users. Xu et al. [

2] explain that it also supports cognitive capabilities when integrated with analytics and AI, enabling devices to interpret and act upon information. This digital nervous system transforms manufacturing facilities into intelligent ecosystems, capable of responding to changes in demand, environmental conditions, or supply constraints with unprecedented agility.

4.1.1.3. Internet of Services

The Internet of Services (IoS) in Industry 4.0 represents a shift from product-centric to service-oriented manufacturing. It enables models such as “product-as-a-service,” in which ownership is replaced by usage-based service agreements, thus aligning production capabilities more closely with customer needs. Reis and Gonçalves [

14] explain that IoS brought about concepts like Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA), which “reorganize software applications and infrastructure into a set of interacting services” (p.2). This evolution facilitates mass customization, real-time collaboration, and platform-based competition. Through SOAs and cloud computing, the IoS allows manufacturing functions such as design, simulation, monitoring, and maintenance to be offered on demand [

3]. This increases the efficiency of resource utilization and decentralizes innovation by empowering smaller firms to access sophisticated capabilities without heavy infrastructure investment.

4.1.1.4. Smart Factory

The Smart Factory is the operational manifestation of Industry 4.0 principles. It is characterized by its adaptability, efficiency, and deep integration of information and communication technologies. It represents an environment where machines, systems, and humans are connected through CPS and IoT [

15]. This results in real-time communication, data-driven decision-making, and process optimization. In a smart factory, production systems are no longer rigid; they are self-organizing and capable of responding dynamically to fluctuating demands, system anomalies, or customization requirements [

3,

16]. Autonomous robots coordinate with manufacturing execution systems, while AI algorithms optimize real-time production schedules. Digital twins replicate physical systems virtually to simulate and test scenarios without interrupting real operations [

17]. Thus, the smart factory serves as a testbed for human-machine collaboration, raising new questions about human oversight, trust in autonomous systems, and the ethical deployment of emerging technologies.

4.2. Key Technologies in Industry 4.0

The realization of Industry 4.0 relies on multiple advanced technologies that facilitate its fundamental transformations. These technologies are the enablers of its key components and allow for the digitization, automation, and optimization of industrial processes. They include:

4.2.1. Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and CPS

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), when combined with CPS, creates the technological infrastructure for real-time, autonomous industrial operations. IIoT refers to the application of IoT technologies in industrial settings, such as manufacturing, logistics, and utilities, where reliability, low latency, and data security are paramount [

13,

18]. While CPS provides the intelligence and actuation, IIoT enables widespread connectivity and data transmission across heterogeneous devices [

12]. This integration allows for end-to-end visibility and control of industrial processes, from raw material sourcing to product delivery. IIoT and CPS support the development of cyber-resilient systems capable of responding to both physical disturbances and cyber threats, thus ensuring continuity and reliability in critical infrastructure.

4.2.2. Additive Production (3D - the Printing)

Additive manufacturing or 3D printing is a transformative production technology that aligns closely with the customization and flexibility goals of Industry 4.0. Jiang et al. [

19] explain that the structure of additive manufacturing involves building objects layer by layer from digital models. This allows for creating complex geometries, lightweight structures, and rapid prototyping with minimal material waste. 3D printing facilitates decentralized and on-demand production in industrial contexts, reducing dependence on global supply chains and large-scale inventories [

20,

21]. Moreover, integrating 3D printing with AI and IoT enables real-time quality assurance and adaptive control of production parameters, further enhancing its utility in high-mix, low-volume environments.

4.2.3. Big Data

Big Data is the analytical engine of Industry 4.0 that enables organizations to derive actionable insights from vast and diverse data sources. Industries generate data from machines, sensors, enterprise systems, and customer interactions [

22]. The data volume, variety, velocity, and veracity pose a significant challenge. However, big data analytics employs machine learning, natural language processing, and real-time processing to convert raw data into predictive and prescriptive intelligence [

23]. For instance, Özdemir and Hekim [

24] found that predictive maintenance algorithms can forecast equipment failures, while demand forecasting tools optimize inventory and logistics. Furthermore, big data enables closed-loop manufacturing by continuously feeding performance data into design and production processes.

4.2.4. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI in Industry 4.0 provides systems with the cognitive ability to interpret data, learn from patterns, and make autonomous decisions. In manufacturing, AI algorithms are employed in process optimization, defect detection, quality assurance, and robotic control [

25]. Machine learning models can identify inefficiencies in production lines, recommend corrective actions, or adjust operational parameters in real time. AI also plays a central role in human-machine interaction, enabling systems to understand natural language commands or adapt to human behavior [

26,

27]. In addition, AI introduces strategic capabilities such as design innovation, customer personalization, and adaptive logistics.

4.2.5. Collaborative Robots (CoBot)

Collaborative robots, or CoBots, are designed to work safely and efficiently alongside human workers. They enable hybrid workflows that combine the precision and endurance of machines with human judgment and dexterity [

28]. Unlike traditional industrial robots operating in isolated environments, CoBots are equipped with advanced sensors, force control, and safety protocols that allow for physical proximity and human interaction [

29]. This opens up new possibilities for flexible automation, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises that require adaptable and cost-effective solutions. According to Demir et al. [

30], CoBots are employed in tasks such as assembly, packaging, and quality inspection, where their ability to learn from demonstration and adjust to context proves invaluable. The integration of CoBots reflects a broader trend toward human-centric automation, where the goal is not to replace workers but to augment their capabilities and ensure safer, more engaging work environments.

4.2.6. Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality technologies provide immersive environments that enhance training, simulation, and design processes within Industry 4.0. VR in manufacturing facilitates virtual prototyping, ergonomic assessments, and operator training without disrupting actual production [

3]. Engineers can interact with digital twins of products or systems, allowing for iterative testing and optimization before physical deployment. VR also supports collaborative design across geographically dispersed teams by offering a shared virtual space for real-time interaction [

12]. When integrated with AI and real-time data, VR enables predictive visualization. This allows users to foresee system behaviors under different scenarios. However, its effectiveness depends on the integration of accurate data models and user-centric design to ensure that immersive experiences translate into meaningful industrial outcomes.

3.3. The Emergence of Industry 5.0

The Industry 5.0 concept has emerged as a way of addressing the various gaps associated with Industry 4.0 technologies. For instance, Akundi et al. [

23] found that the data in the cloud under Industry 4.0 technologies is not adequately protected, and the expert systems aren’t fully developed to be applied in all sectors. In addition, this industrial revolution focused on technological advances without paying adequate attention to its impacts on society and the planet. Thus, Alimam et al. [

13] indicate that the Industry 5.0 technologies aim to mitigate the risks through collaborative tools that improve human-machine cooperation. As a result, Zizic et al. [

31] explain that Industry 5.0 is characterized by three key drivers: human-centric approach, sustainability, and resilience. Similarly, Xu et al. [

2] identify these 3 components as the core values of Industry 5.0. The human-centric approach entails placing the human needs at the center of production systems and processes. Sustainability focuses on reducing waste and environmental impacts. It advocates for reusing, repurposing, and recycling natural resources. Resilience entails creating robust industries through adaptable manufacturing capacities and flexible processes.

The European Commission formally articulated the concept of Industry 5.0 in 2021, highlighting its role as a complement to Industry 4.0 rather than as a successor. According to the Commission, Industry 5.0 is not a technological advancement; instead it provides “regenerative purpose and directionality to the technological transformation of industrial production for people–planet–prosperity” [

31] (p.4). This means that Industry 5.0 aims to rebalance productivity objectives with values such as inclusivity, human dignity, and planetary health. Despite progress made through Industry 4.0, the Commission notes that it creates technological monopoly and contributes to wealth inequality. As a result, this industrial revolution does not provide the right framework for achieving Europe’s 2030 goals. On the other hand, Industry 5.0 integrates technology, people, society, business, environment, processes, and cultures [

32,

33]. These considerations help create sustainable development, ensuring that technological advancements do not compromise the well-being of societies and the environment.

3.4. Factors Driving the Shift Towards Industry 5.0

More companies worldwide are embracing the principles and technologies of Industry 5.0. For example, there have been increased concerns over the impact of technologies like AI on human labor. In addition, consumers worldwide are questioning businesses’ sustainability initiatives. These issues are pushing enterprises to re-evaluate their systems and processes to accommodate other crucial principles advocated for in Industry 5.0. These factors include:

3.4.1. Human-Machine Collaboration

Industry 5.0 reconceptualizes the relationship between humans and machines, not as a dichotomy but as a dynamic collaboration. Unlike Industry 4.0, which prioritized automation and minimized human intervention, Industry 5.0 seeks to reintegrate human resources into complex production systems [

34]. Industries are achieving this goal through collaborative robotics, advanced AI interfaces, and augmented decision-making frameworks. This shift is driven by the recognition that human cognitive and emotional capabilities, such as empathy, creativity, and moral reasoning, are irreplaceable in tasks that require adaptability, personalization, or complex problem-solving [

30,

35]. Human-machine collaboration involves technologies designed to complement human strengths rather than replace them, such as CoBots that adapt to human gestures or AI systems that enhance, not dictate, human decision-making. This integration improves productivity while also safeguarding the dignity and agency of the worker, which are central tenets of Industry 5.0.

3.4.2. Ethical Considerations

The ethical implications of AI and automation have catalyzed a growing movement toward human-centric innovation. Concerns over data privacy, algorithmic bias, surveillance capitalism, and labor displacement have underscored the inadequacies of a purely efficiency-driven technological model [

36,

37]. Industry 5.0 addresses these issues by embedding ethical governance frameworks into the design and deployment of digital technologies [

37]. This involves ensuring transparency, accountability, and explainability in AI systems, while also upholding principles such as fairness, inclusivity, and social justice [

38,

39]. Moreover, regulatory and normative pressures demand that industrial systems function efficiently and align with democratic values and societal expectations. As such, ethical foresight becomes a strategic imperative within Industry 5.0 ecosystems rather than a constraint.

3.4.3. Sustainability

Sustainability has become a central driver of systemic transformation in Industry 5.0. Industry 4.0 is characterized by environmental externalities, such as high energy consumption, material waste, and carbon-intensive supply chains [

40]. These have exposed the need for production models that are both technologically advanced and ecologically responsible. Industry 5.0 integrates digital technologies with sustainability goals by promoting circular economy practices, resource efficiency, and carbon-neutral operations [

41,

42]. AI and IoT systems are employed to optimize energy use, predict maintenance needs, and reduce waste, while digital twins and life-cycle analysis tools enable the design of regenerative processes. Oladeinde and Ojo [

33] indicate that the shift reflects a broader societal and regulatory demand for industries to transition from extractive to restorative paradigms. These reinforce Industry 5.0’s alignment with global climate targets and environmental stewardship.

3.4.4. Growing Cybersecurity Concerns

Cybersecurity has emerged as a critical vulnerability as industrial systems become increasingly digitized and interconnected. For example, cybersecurity vulnerabilities cost the global economy approximately US

$ 945 billion in 2020 [

43]. Integrating AI, IoT, and cloud-based infrastructures in Industry 4.0 has expanded the attack surface of industrial environments, exposing them to sophisticated threats such as ransomware, data breaches, and AI-driven cyberattacks. Industry 5.0 acknowledges that robust cybersecurity is foundational for system integrity and public trust in emerging technologies [

15]. The shift includes developing resilient architectures that integrate zero-trust models, AI-based threat detection, and real-time incident response mechanisms. Moreover, Shkarupylo et al. [

44] explain emphasize human factors in cybersecurity, such as awareness, behavior, and ethical responsibility. This practice reinforces the Industry 5.0 ethos that technological systems must be secure, transparent, and accountable by design.

3.4.5. Need for Resilient and Time-Sensitive Systems

Recent global disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical instability, have exposed the fragility of global supply chains and real-time industrial systems. For example, Vilko and Hallikas [

45] found that during the pandemic, most companies struggled with uncertainties related to suppliers’ delivery times, product availability, access to raw materials, and price stability. Industry 5.0 responds to these challenges by prioritizing resilience and temporal sensitivity in the design of industrial infrastructure [

46]. This includes deploying edge computing, decentralized decision-making, and AI-driven predictive analytics to enable systems that can adapt in real time to changing conditions. The focus is on efficiency, robustness, adaptability, and recovery capacity. Systems are expected to self-correct, reroute, and continue operations despite external shocks or internal failures [

2,

47]. Such design philosophies ensure that Industry 5.0 environments are technologically sophisticated and capable of sustaining essential operations during crises, reflecting a shift from optimization to antifragility.

3.4.6. Increasing AI Education and Workforce Preparedness

As AI becomes deeply embedded in industrial functions, workforce preparedness has emerged as a key factor in the transition to Industry 5.0. Unlike previous industrial revolutions that displaced labor through automation, Industry 5.0 seeks to empower workers through upskilling, reskilling, and continuous learning [

48]. Governments, academic institutions, and industry leaders are investing in AI education initiatives that promote digital literacy, systems thinking, and ethical reasoning. Integrating AI into vocational training, lifelong learning platforms, and participatory design processes ensures workers can meaningfully contribute to and benefit from technological advancements [

46,

49]. This focus on human capacity building reflects Industry 5.0’s commitment to inclusive growth and equitable access to the benefits of digital transformation.

3.4.7. Demand for Co-Creation and Co-Production

Industry 5.0 emphasizes participatory innovation, where stakeholders, including workers, customers, and communities, are actively involved in the co-creation and co-production of goods and services. This shift stems from growing demand for personalized products, localized solutions, and socially embedded production processes [

41]. Industries leverage AI, digital fabrication tools, and open innovation platforms to respond more effectively to user needs while building a sense of ownership and agency among stakeholders. Co-creation enhances innovation outcomes by incorporating diverse perspectives and contextual knowledge into design and development processes [

41,

50]. This approach aligns with the values of democratization and decentralization that characterize Industry 5.0, moving away from top-down engineering toward collaborative, iterative, and human-informed systems.

3.4.8. Need for Advanced Quality Control Systems

The complexity of modern manufacturing processes and the demand for high customization and minimal defects reflect the importance of advanced quality control systems. Industry 5.0 introduces AI-powered visual inspection tools, real-time monitoring, and predictive quality analytics to detect anomalies and maintain high standards throughout production [

12,

51]. These systems automate quality control and integrate human oversight and domain expertise to fine-tune AI models, validate outcomes, and ensure compliance with both technical and ethical standards. The convergence of precision technology with human judgment enhances operational efficiency, customer satisfaction, and product trustworthiness [

49,

52]. This aligns with Industry 5.0’s holistic focus on the quality of products, processes, experiences, and relationships.

3.5. Key Technologies Enabling the Evolution from Industry 4.0 to 5.0 in Relation to AI, Optimization, and Human Values

Industries are shifting from the automation-centric framework of Industry 4.0 to the human-centric and ethical paradigm of Industry 5.0. As a result, the enabling technologies are becoming increasingly interdisciplinary, while their core functionalities reveal a dominant alignment. This includes advancements in artificial intelligence capabilities, performance and resource optimization, and deepening human value integration in industrial systems. Below is an exploration of the common technologies classified in these 3 dominant aspects;

3.5.1. Artificial Intelligence

The AI domain represents the core intellectual engine of Industry 5.0. It advances automation, cognition, creativity, and contextual decision-making. Technologies under this category push the boundaries of how machines learn, reason, and generate content in collaboration with human users.

3.5.1.1. Generative AI and Explainable AI

Generative AI, such as GPT-based models and diffusion networks, is redefining design, engineering, and customer-facing applications. It achieves this through its capacity to produce content, code, and schematics autonomously [

53]. Generative AI’s significance in Industry 5.0 lies in its potential for co-creation, allowing human operators to ideate with machines in real-time [

54,

55]. Conversely, Explainable AI (XAI) addresses one of the most pressing concerns of post-automation systems: the opacity of machine reasoning. Das and Rad [

56] indicate that XAI provides tools, techniques, and algorithms that generate high-quality content that is easy for humans to understand and interpret. It helps non-AI experts and end-users understand the internal operations of AI innovations, thus empowering them to use tools to generate more accurate results [

15,

49]. Generative and Explainable AI technologies empower industrial creativity and enforce the trustworthiness and regulatory compliance essential in a human-centric industrial era.

3.5.1.2. Machine Learning

Machine Learning (ML) forms the analytical backbone of Industry 5.0 systems. ML enables pattern recognition, prediction, and autonomous adaptation across dynamic industrial environments [

28]. ML algorithms are applied in predictive maintenance, energy efficiency modeling, and demand forecasting, offering continuous optimization based on real-time data. Terziyan and Vitko [

21] indicate that its deep integration into manufacturing and logistics workflows ensures responsiveness, scalability, and resource-aware operations. Its human-centric applications, such as adaptive learning systems and emotion recognition, are key in personalizing workspaces and user interactions.

3.5.1.3. Cyber-Physical Systems and Digital Twins

Cyber-physical systems (CPS) and digital twins embody the convergence of physical and digital realms through sensor integration, real-time data streams, and intelligent control mechanisms. In Industry 5.0, these systems are automated, context-aware, and cooperative, making them vital to AI-driven orchestration of smart environments [

12]. Digital twins extend this functionality by providing dynamic, real-time replicas of physical assets or processes, allowing predictive simulations, enhanced diagnostics, and remote collaboration [

57,

58]. Their integration with AI enhances resilience, flexibility, and cognitive augmentation in system design and operation.

3.5.1.4. Optimization

Optimization technologies are the engines of efficiency and resilience in Industry 5.0. These tools focus on improving throughput, minimizing waste, and supporting agile reconfiguration of complex systems under resource constraints, uncertainty, or shifting objectives. They include:

3.5.1.4.1. Sensor Technologies

Sensor technologies help collect real-time, high-fidelity data for optimized decision-making in Industry 5.0. Their integration with AI-driven systems enables predictive management of industrial processes, facilitating real-time responses to operational variables such as temperature, pressure, and machine status [

59]. Advanced sensors can also monitor environmental and worker health parameters, ensuring operational efficiency and safety. Morales Matamoros et al. [

51] explain that they enhance optimization by enabling continuous, automated workflow adjustments, reducing waste, and maximizing system throughput. The high degree of interconnectivity and data sharing among sensors also allows for distributed decision-making, ensuring that systems can quickly adapt to changes in demand, resource availability, or environmental conditions.

3.5.1.4.2. Multi-Objective Optimization and Edge Computing

Multi-objective optimization (MOO) is essential for navigating modern industrial systems’ complex, often conflicting goals that require balancing parameters like energy consumption, production speed, and waste minimization. MOO algorithms generate solutions that maximize efficiency across these criteria, providing decision-makers with optimal alternatives that support better strategic planning [

40,

60]. On the other hand, edge computing processes data locally near the generation source. When combined, MOO and edge computing enable real-time optimization with minimal latency and reduced dependency on centralized cloud infrastructure [

60,

61]. This decentralized approach improves responsiveness and scalability, which is crucial for managing the intricate dynamics of smart factories and real-time production systems in Industry 5.0. Edge computing further enhances this by enabling data processing at the source, ensuring faster decision-making and enabling autonomous systems to operate efficiently even in remote or resource-constrained environments.

3.5.1.4.3. Next-Gen Communication Technologies

Next-generation communication technologies, such as 5G and beyond, are critical enablers of the ultra-low latency, high-bandwidth connectivity required for seamless coordination across highly distributed industrial systems. According to Özdemir and Hekim [

24], these communication networks allow for uninterrupted, fast-paced data transfer between devices, sensors, and systems, which is foundational for real-time decision-making and collaborative robotics. With 5G’s potential for faster, more reliable communication, manufacturing processes can achieve near-instantaneous synchronization across geographically dispersed operations, supporting complex tasks like just-in-time inventory and real-time process monitoring [

62]. This facilitates smart factories where processes are continuously optimized based on immediate operational feedback. Moreover, the high bandwidth and low latency of next-gen networks are pivotal for ensuring effective integration of AI, IoT, and cyber-physical systems in Industry 5.0, paving the way for a more interconnected, adaptive industrial ecosystem.

3.5.1.4.4. Life Cycle Assessment Models

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) models are essential tools in Industry 5.0 for understanding the full environmental and economic impact of products and processes throughout their life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal. Turner et al. [

63] explain that these models are increasingly integrated with optimization algorithms, enabling real-time environmental performance tracking and facilitating decisions that minimize negative ecological impacts. LCA is particularly relevant to sustainability goals, as it ensures that resource use, energy consumption, and waste production are optimized at every stage of the product life cycle [

64]. Industry 5.0 systems embed LCA into production planning, leading to operational efficiency and driving sustainable innovation. This aligns with the growing demand for circular economy models, where products are designed with recyclability and resource efficiency in mind. Integrating LCA into AI-driven optimization frameworks provides a powerful mechanism for balancing economic profitability with environmental responsibility.

3.5.1.5. Human Values

Human-centric technologies in Industry 5.0 emphasize the integration of human well-being, empowerment, and ethical decision-making into the design and deployment of industrial systems. This industrial revolution advocates for a technology-enhanced collaboration between humans and machines, optimizing worker experiences and operational outcomes. The various technologies associated with these goals include:

3.5.1.5.1. Wearable Technologies

Wearable technologies, such as smartwatches, exoskeletons, and biometric monitoring devices, significantly enhance human capabilities and ensure health and safety within industrial environments. These devices collect real-time physiological data like heart rate, fatigue levels, and environmental information like temperature and air quality [

20]. This provides actionable insights to improve both individual and organizational performance. Wearables used in Industry 5.0 facilitate personalized worker assistance, where the system adapts to the needs and status of each operator. These technologies are crucial in hazardous or physically demanding industries, enabling workers to perform tasks with increased ergonomics and safety [

12,

46]. They also contribute to data-driven decision-making by providing workers and managers with continuous feedback on their performance, ensuring that operational adjustments can be made swiftly to optimize productivity while safeguarding worker welfare.

3.5.1.5.2. Human-Robot Collaboration

Human-robot collaboration (HRC) in Industry 5.0 represents a shift from automation to augmentation. In this case, robots and humans work together to enhance productivity, creativity, and efficiency [

35]. Traditional industrial robots performed tasks independently. On the contrary, collaborative robots (CoBots) are designed to work safely alongside humans, responding to human actions and sharing tasks based on their complementary strengths [

28,

29]. This partnership can take various forms, such as robots assisting with heavy lifting, precision tasks, or hazardous processes, while humans focus on creative, supervisory, or problem-solving roles. These HRC systems improve operational efficiency and worker satisfaction by reducing the physical strain on human operators and allowing for a more flexible production environment [

19]. Furthermore, these collaborative systems enhance human values by promoting worker safety, inclusive job designs, and supporting continuous learning and worker autonomy within industrial settings.

4. Conclusions

The transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 represents a fundamental shift in how industries operate, driven by the integration of advanced technologies and a focus on human-centric values. Industry 4.0 is characterized by cyber-physical systems, the Internet of Things (IoT), and smart manufacturing. It emphasized automation, efficiency, and data-driven decision-making to optimize industrial processes. Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data play pivotal roles in streamlining operations and improving system efficiency. However, the evolving work environment alongside growing concerns about sustainability, worker well-being, and ethical considerations has led to the emergence of Industry 5.0. This industrial revolution seeks to integrate human values into technological progress. It prioritizes human-machine collaboration, the importance of ethical decision-making, and the need for sustainable practices within industrial operations. As a result, Industry 5.0 is reshaping how technology and human labor coexist in the manufacturing environment.

There are various factors contributing to the emergence of Industry 5.0. These include the desire for more resilient, adaptive systems that respond to real-time challenges and a growing emphasis on sustainability and ethical decision-making. AI education and workforce preparedness are critical to ensuring workers have the necessary skills to navigate this evolving landscape. Concurrently, integrating cutting-edge technologies, such as wearable devices, human-robot collaboration, and next-gen communication systems, supports the vision of a human-centered industrial future. These technologies enhance operational efficiency and promote worker safety, autonomy, and engagement, thus creating a more inclusive and sustainable industrial ecosystem. Furthermore, the emphasis on optimization technologies, including multi-objective optimization, sensor technologies, and edge computing, allows industries to make real-time, data-driven decisions that balance economic, environmental, and social outcomes.

From a theoretical standpoint, this research enriches the existing discourse by systematically mapping the intellectual evolution from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0, emphasizing the interdependence between technological innovation and human-centered values. It contributes to the academic literature by clarifying how artificial intelligence and optimization frameworks are being reshaped to incorporate ethical, environmental, and social dimensions within industrial transformation. Moreover, it refines the conceptual understanding of key technological enablers—such as cyber-physical systems, generative AI, and life cycle assessment models—by situating them within the broader context of resilience, sustainability, and collaborative intelligence.

Practically, this study provides valuable guidance for industry leaders, policymakers, and technology developers. It offers an evidence-based perspective on how to transition from automation-centric systems to inclusive production models that prioritize human well-being, transparency, and adaptability. The findings encourage the adoption of co-creative strategies, integration of ethical AI tools, and investment in workforce reskilling. By framing technology as a means to enhance rather than replace human capabilities, this research supports the design of industrial ecosystems that are not only efficient but also socially responsible and future-resilient.

While this study provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving industrial paradigm, several avenues remain open for deeper inquiry. One critical area involves the exploration of ethical AI integration across diverse industrial settings, particularly in sectors with limited regulatory frameworks or high socio-environmental impact. Future research could also investigate how human-machine collaboration evolves under different cultural and organizational contexts, with attention to user trust, agency, and long-term cognitive effects.

Another promising direction lies in the development of metrics that quantify the societal value generated by Industry 5.0 practices, beyond traditional productivity benchmarks. Scholars might also examine the implications of emerging technologies—such as quantum computing, bio-digital interfaces, or synthetic cognition—within the human-centric frameworks proposed by Industry 5.0. Finally, longitudinal case studies assessing the real-world adoption of Industry 5.0 principles could offer critical insights into the barriers and enablers of sustainable and ethical innovation in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and R.R.; methodology, A.R. and R.R.; software, A.R. and R.R.; validation, A.R. and R.R.; formal analysis, A.R. and R.R.; investigation, A.R. and R.R.; resources, A.R. and R.R.; data curation, A.R. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R. and R.R.; visualization, A.R. and R.R.; supervision, A.R. and R.R.; project administration, A.R. and R.R.; funding acquisition, A.R. and R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author receives financial support from the Research Unit on Governance, Competi-tiveness and Public Policies (UIDB/04058/2020) + (UIDP/04058/2020), funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Editor and the Referees. They offered extremely valuable suggestions or improvements. The authors were supported by the GOYCOPP Research Unit of Universidade de Aveiro and ISEC Lisboa, Higher Institute of Education and Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2015 to 2025.

Table A1.

Overview of document citations period ≤2015 to 2025.

| Documents |

|

≤2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2021 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

Total |

| Reviewing human-robot collaboration in manufacturing: Opportunities and challenges in the context of industry 5.0 |

2025 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

| Artificial Intelligence of Things Infrastructure for Quality Control in Cast Manufacturing Environments Shedding Light on Industry Changes |

2025 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

| Industry 4.0 technologies for sustainability within small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review and future directions |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

| AI’s effect on innovation capacity in the context of industry 5.0: a scoping review |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

| Toward a Human-Cyber-Physical System for Real-Time Anomaly Detection |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| Human in the AI loop via XAI and active learning for visual inspection |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| Human-machine Collaborative Additive Manufacturing for Industry 5.0 |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Digital Twins for Industry 5.0: Unlocking the Human Potential |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Exploring the Potential Network Vulnerabilities in the Smart Manufacturing Process of Industry 5.0 via the Use of Machine Learning Methods |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Artificial Intelligence in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Requirements and Barriers |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Toward human-centered intelligent assistance system in manufacturing: challenges and potentials for operator 5.0 |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

| Enhancing wisdom manufacturing as industrial metaverse for industry and society 5.0 |

2024 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

53 |

19 |

83 |

| Towards new-generation human-centric smart manufacturing in Industry 5.0: A systematic review |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

76 |

38 |

116 |

| Towards Human Digital Twins to enhance workers’ safety and production system resilience |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

7 |

16 |

| Digital Triplet Paradigm for Brownfield Development towards Industry 5.0: A Case Study of Intelligent Retrofitting for Oil and Gas Boosting Plant in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) Context |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

| Wearable Technology for Smart Manufacturing in Industry 5.0 |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

10 |

| Artificial Intelligence for Smart Manufacturing in Industry 5.0: Methods, Applications, and Challenges |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

14 |

2 |

19 |

| Explainable Articial Intelligence for Cybersecurity in Smart Manufacturing |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

| Industry 5.0 and Human-Centered Approach. Bibliometric Review |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

6 |

| Human-centric artificial intelligence architecture for industry 5.0 applications |

2023 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

13 |

82 |

33 |

129 |

| Enriching Artificial Intelligence Explanations with Knowledge Fragments |

2022 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

10 |

| State of Industry 5.0—Analysis and Identification of Current Research Trends |

2022 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

63 |

147 |

42 |

277 |

| Industry 5.0: From Manufacturing Industry to Sustainable Society |

2022 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

5 |

14 |

| Evaluation of AI-Based Digital Assistants in Smart Manufacturing |

2022 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

12 |

| Industry 5.0 and Human-Robot Co-working |

2019 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

44 |

96 |

125 |

180 |

46 |

504 |

| |

Total |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

44 |

125 |

231 |

609 |

218 |

1,24 |

References

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N. A Literature Review of the Challenges and Opportunities of the Transition from Industry 4.0 to Society 5.0. Energies 2022, 15, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. Journal of manufacturing systems 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skobelev, P.O.; Borovik, S.Y. On the way from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: From digital manufacturing to digital society. Industry 4.0 2017, 2, 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian journal of management 2019, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA 2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell systematic reviews 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosário, A.T.; Fernandes, F.; Raimundo, R.G.; Cruz, R.N. Determinants of Nascent Entrepreneurship Development. In A. Carrizo Moreira and J. Dantas (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Nascent Entrepreneurship and Creating New Ventures, 2021, (pp. 172–193). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T. Generative AI and Generative Pre-Trained Transformer Applications: Challenges and Opportunities. In S. Hai-Jew (Ed.), Making Art With Generative AI Tools, 2024, (pp. 45–71). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, K.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. The assembly process and co-occurrence network of soil microbial community driven by cadmium in volcanic ecosystem. Resources, Environment and Sustainability 2024, 17, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.O.; Ferenhof, H.A.; Forcellini, F.A. Industry 4. 0 and Industry 5.0 from the Lean perspective. Int. J. Manag. Knowl. Learn, 2022, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Boursali, A.E.; Benderbal, H.H.; Souier, M. Integrating AI with Lean Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0/5.0: Current Trends and Applications. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 2024.

- Bajic, B.; Rikalovic, A.; Suzic, N.; Piuri, V. Toward a Human-Cyber-Physical System for Real-Time Anomaly Detection. IEEE Systems Journal 2024, 18, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimam, H.; Mazzuto, G.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Bevilacqua, M. Digital Triplet Paradigm for Brownfield Development towards Industry 5.0: A Case Study of Intelligent Retrofitting for Oil and Gas Boosting Plant in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) Context. Proceedings - 2023 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence and Computing, Autonomous and Trusted Vehicles, Scalable Computing and Communications, Digital Twin, Privacy Computing and Data Security, Metaverse, SmartWorld/UIC/ATC/ScalCom/DigitalTwin/PCDS/Metaverse 2023.

- Reis, J.Z.; Gonçalves, R.F. The role of internet of services (ios) on industry 4.0 through the service oriented architecture (soa). In Advances in Production Management Systems. Smart Manufacturing for Industry 4.0: IFIP WG 5.7 International Conference, APMS 2018, Seoul, Korea, August 26-30, 2018, Proceedings, 2018, Part II (pp. 20–26). Springer International Publishing.

- Bac, T.P.; Ha, D.T.; Tran, K.D.; Tran, K.P. Explainable Articial Intelligence for Cybersecurity in Smart Manufacturing. In Springer Series in Reliability Engineering, 2023, (Vol. Part F4, pp. 199–223). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Mentzas, G.; Apostolou, D.; Wellsandt, S. Evaluation of AI-Based Digital Assistants in Smart Manufacturing. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 2022.

- Leirmo, T.L. Digital Twins for Industry 5.0: Unlocking the Human Potential. Procedia CIRP, 2024a.

- Boyes, H.; Hallaq, B.; Cunningham, J.; Watson, T. The industrial internet of things (IIoT): An analysis framework. Computers in industry 2018, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, B. Human-machine Collaborative Additive Manufacturing for Industry 5.0. Jixie Gongcheng Xuebao/Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2024, 60, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Tran, K.P. Artificial Intelligence for Smart Manufacturing in Industry 5.0: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. In Springer Series in Reliability Engineering, 2023, (Vol. Part F4, pp. 5–33). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Terziyan, V.; Vitko, O. Context-Aware Machine Learning for Smart Manufacturing. Procedia Computer Science 2025, 253, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jia, Y. Innovation and development of cultural and creative industries based on big data for industry 5.0. Scientific Programming, 2022, 2022, 2490033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]