1. Introduction

Obesity is a complex and chronic disease that can potentially affect the quality of life in terms of decreasing physical health as well as their mental and social well-being. Despite the preventive interventions developed in recent years, the global prevalence and incidence of obesity continue to rise, to the extent that the World Health Organization (WHO) considers it an epidemic disease [

1]. In 2022, approximately 2.5 billion people were affected by overweight, including 890 million individuals with obesity. Currently, one in eight people has obesity, indicating that obesity rates have doubled among adults and quadrupled among adolescents compared to values from the 1990s [

2]. In some areas, the prevalence of obesity is expected to double by 2050 [

3].

Obesity is characterized by the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue, which may be attributed to genetic and/or socio-environmental factors. Classically, obesity was defined by a body mass index (BMI) above 30 kg/m², in contrast to overweight, which is defined by a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m² [

4]. However, BMI alone is often an insufficient biomarker, as it does not fully capture cardiometabolic risk. In contrast, the addition of BMI above 25 kg/m² and a waist-to-height ratio (WtHr) greater than 0.5 help optimize the stratification of obesity risk [

5,

6]. There is enough evidence highlighting the relationship between obesity and metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, endocrine disorders, mental health conditions, neoplastic, and renal diseases. Visceral obesity is also associated with an increased inflammation and risk of all-cause mortality [

7]. Currently, a new classification of obesity is referred to as adiposity-based chronic disease (ABCD), and it is based on its etiology, degree of adiposity, and associated health risks. The complications of obesity are determined by two pathological processes: fat mass disease and sick fat disease, with the second being related to endocrine and immune responses capable of activating the inflammatory response and causing organ damage [

8]

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a public health priority and a global concern, as it is projected to be among the top five causes of death by 2040. In many countries, the prevalence of CKD is underestimated by the insufficient screening measures to detect functional and structural renal abnormalities [

9]. The progressive increase in the number of patients with CKD is also explained by the rise in cases of hypertension, metabolic syndrome (MS), and diabetes mellitus (DM) [

10]. Thereby, Chang and cols. described that elevated BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-height ratio are independent risk factors for a drop-in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and mortality in individuals with and without prior kidney disease [

11].

The objective of this review is to focus in the importance of inflammation and the pathophysiological processes involved in the relationship between obesity and the development of kidney disease. Additionally, the various existing treatments and those currently under clinical trials are discussed.

2. Obesity and the Development of Chronic Kidney Disease

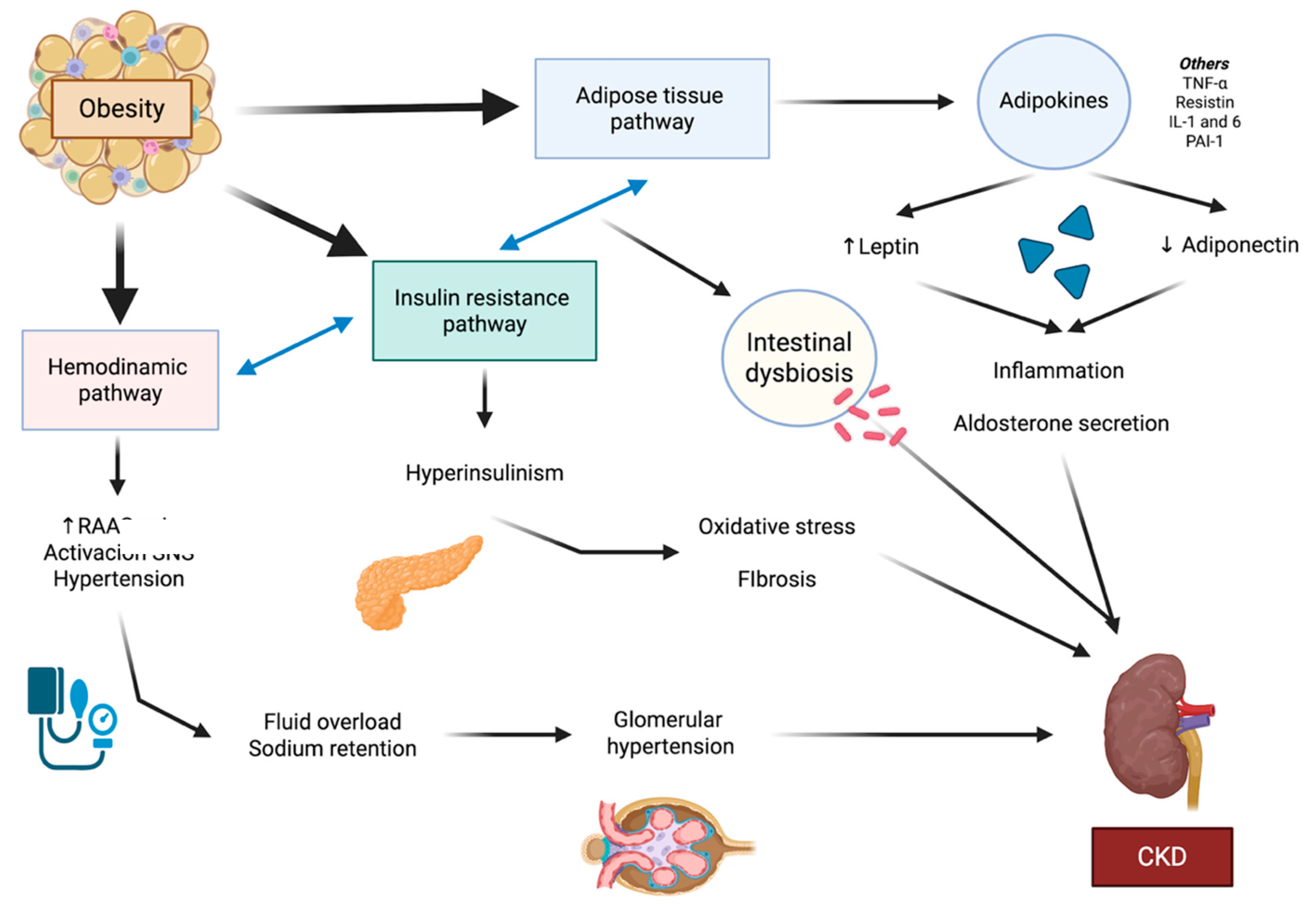

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of kidney disease, as it creates an environment of intraglomerular hypertension conditioned by many pathways. García-Carro and cols. defined three main groups explaining the pathophysiological mechanisms of kidney disease in obesity: the hemodynamic, adipose tissue-related and the insulin resistance-hyperinsulinism [

12]. It is important that the previously mentioned pathways interact with each other and adapt to factors related to other comorbidities such as age, and sex (

Figure 1).

2.1. The Hemodynamic Pathway

The hemodynamics of individuals with obesity are compromised in part secondary to the pathological hyperfiltration process associated with increased metabolic demands, the activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) axis, the affinity of angiotensin II (Ang-II) receptors, fluid overload, and the positive feedback of the sympathetic nervous system [

12].

The pathophysiological process includes vasodilation of the afferent arterioles and vasoconstriction of the efferent arterioles, associated with a reduction in tubuloglomerular feedback responsible for the vasoconstriction of the afferent arterioles [

13]. The alteration of renal sympathetic nervous system is also explained by the activation of the chemoreceptors in the carotid bodies and, consequently, increased sympathetic activity [

14,

15]. Moreover, proximal tubular sodium reabsorption is increased, leading to diminished distal sodium delivery and stimulating the macula to increase renin secretion, thereby contributing to the perpetuation of the vicious cycle of hypertension of fluid overload [

16].

2.2. Adipose Tissue-Related Pathway

Excessive accumulation of fat in patients with obesity enhances the endocrine and paracrine capabilities of adipocytes [

17]. Visceral adipocytes also contain angiotensinogen, and their activity directly depends on the increase in BMI related to fat [

18]. Adipocytes are responsible for the secretion of adipokines. Among the most important adipokines are leptin, adiponectin, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), resistin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 [

19].

Adiponectin normally promotes the oxidation of fatty acids and regulates glucose metabolism. Adiponectin levels also appear to be directly linked to renal function, and it is primarily found in the arterial endothelium, smooth muscle cells of the kidneys, and capillary endothelium [

20]. In patients with obesity there is an independent inverse association between albuminuria and adiponectin levels in nondiabetic individuals with overweight or obesity [

21]. Thus, low levels of adiponectin also correlate with impaired fatty acids metabolism and insulin resistance. Studies in mice have shown that the deletion of adiponectin is associated with podocyte dysfunction, interstitial fibrosis, and albuminuria [

22].

Unlike adiponectin, leptin levels are elevated in individuals with obesity and CKD, which represents a greater risk of hypertension, inflammation, and fibrosis [

23]. Leptin enhances hypertension through the activation of the RAA axis and increased sympathetic activity. Leptin also enhances fatty acid oxidation, inflammatory cytokines secretion such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, exacerbating renal inflammation and fibrosis [

24]. Studies have found that hyperleptinemia may contribute to the development of glomerulosclerosis and exert profibrotic effects on mesangial cells [

23].

The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome has been described in diabetes and obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG), as hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia activate the inflammasome through reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial damage, and stress [

25,

26]. At the renal level, the inflammasome acts in both the tubuleinterstitium and glomeruli, promoting albuminuria through fibrosis and podocyte effacement [

27].

Finally, the intestinal microbiota has been also identified as a key factor in the development of diseases such as obesity, DM, CKD, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancer, due to its regulatory role in energy and immune balances [

28]. Intestinal dysbiosis can be both caused and exacerbated by uremia, making CKD a contributing factor that is part of the vicious cycle of ongoing damage to the microbiota, alongside pro-inflammatory processes [

29]. It has been observed that children with obesity present elevated levels of

Bacteroides compared to the control group, and that quantitative and qualitative alterations of the intestinal microbiota are common in patients with CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [

30,

31].

2.3. Insulin Resistance-Hyperinsulinism Pathway

Insulin resistance is directly related to the fat mass of individuals and the secretory activity of adipokines. The pro-inflammatory state of obesity inhibits insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) signaling pathways in adipose and muscle tissue, as well as limiting the activity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which is responsible for the process of fat storage and lipid synthesis in adipose tissue [

32].

Excessive insulin secretion favors insulin to interfere with the selective activity of podocytes and the cytoskeleton, reducing endothelial nitric oxide production, facilitating the filtration of albumin and promoting oxidative stress through NADPH oxidase and AKT/mTOR intracellular pathway or glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) [

33,

34]. Furthermore, insulin promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis by enhancing the formation of type IV collagen and TGF-β in the renal tubules [

35].

The mechanisms of renal disease in obesity. Three pathways have been described: hemodynamic, adipose tissue, and insulin resistance. These three pathways interact with each other, secreting adipokines and cytokines, activating the sympathetic nervous system, and promoting the pathological activation of the RAAS. All three pathways lead to renal damage, as the pro-inflammatory state and profibrotic factors favor glomerular hyperfiltration and, consequently, promote endothelial, podocyte, and tubular damage, increasing albuminuria excretion. RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. SNS: sympathetic nervous system. CKD: chronic kidney disease. TNF- α: tumor necrosis factor-α. IL: interleukin. PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor 1.

3. Obesity and Kidney

Obesity is one of the modifiable risk factors for the development of CKD. There is evidence linking obesity to CKD. According to reports, 14 individuals per 1000 adults in the United States have obesity associated with CKD. Additionally, between 20% and 30% of individuals with obesity suffer from kidney disease, and more than 20% of adults with ESRD are diagnosed with morbid obesity [

36]. Besides, obesity is a factor that complicates access to kidney transplantation in patients with ESRD, as the risk of complications increases compared to recipients with a normal BMI [

37,

38].

Remarkably, the previously mentioned inflammatory mechanisms contribute to changes in renal structure, both due to the accumulation of ectopic fat and the increase of fat within the renal sinus [

39]. Furthermore, obesity is also a risk factor for renal lithiasis and renal neoplasms. Nephrolithiasis is associated with low urinary pH, increased urinary oxalate, uric acid, and other electrolytes, while insulin resistance promotes the production of insulin-like growth factor 1, which may exert stimulating effects on the growth of various types of tumor cells [

40].

ORG represents the structural manifestation of renal damage directly attributable to excess body weight; histologically, it is characterized by structural alterations in both the glomerulus and the renal interstitium [

41,

42]. Despite the fact that the prevalence of obesity is continuously increasing, only a proportion of individuals with obesity develop ORG. This suggests that predisposing factors, such as genetic susceptibility or low nephron mass, modulate the individual vulnerability of patients to chronic damage [

43]. The albuminuria associated with ORG may present with objective clinical findings such as hypertension and/or edema, or it may be asymptomatic [

44]. Since the presence of albuminuria indicates existing renal damage, recent experimental studies are advancing transcriptomic analysis to facilitate the prompt diagnosis of ORG through non-invasive biomarkers [

45].

ORG is characterized glomerulomegaly, focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Glomerulomegaly is defined as the diffuse enlargement of glomerular size and is interpreted as a compensatory mechanism in response to increased demand for renal function [

18]. Morphologically, an enlargement of the glomeruli compared to the mean glomerular diameter of patients without obesity, adjusted for age and sex [

42]. Additionally, it is accompanied by mesangial expansion and podocyte hypertrophy with foot process fusion [

18]. Perihilar predominant FSGS is characterized by partial and heterogeneous podocyte effacement, with proteinuria generally in the subnephrotic range. The clinical manifestations of the ORG are often variable [

46]. Obesity also promotes the deposition of lipids in mesangial cells, podocytes, and renal tubules, which in turn enhances fibrosis and tubulointerstitial atrophy [

47,

48]. Finally, metabolic stress, combined with factors such as hypertension or dysfunction of the renin-angiotensin axis, promotes fibrosis through the activation of TGF-β and other profibrotic pathways [

18].

4. Obesity and Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome

Cardiovascular disease is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in individuals with obesity. The cardiometabolic risk depends on the distribution of fat, with visceral adipose tissue representing the highest associated risk [

49]. Remote and local adipose tissue also exert pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory effects in certain organs [

50]. Obesity accelerates the process of atherosclerosis through various mechanisms, including insulin resistance and inflammation. Thus, atherosclerosis promotes the development of cardiovascular disease, such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and dead [

51].

The development of atherosclerosis begins in childhood, with endothelial dysfunction and damage to the tunica being its initial steps. Consequently, the endothelium expresses adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), which are responsible for recruiting inflammatory cells such as monocytes and lymphocytes. The recruited monocytes mature into macrophages that uptake cholesterol particles. The resulting inflammatory response leads to the secretion of interleukins, which promote the synthesis of extracellular matrix, consolidating and propagating the development of atheromatous plaques [

52].

Obesity is one of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as the pro-inflammatory state exacerbates vascular damage and the recruitment of inflammatory cells. Obesity is also associated with metabolic distress. Several studies have shown that a high BMI and/or the accumulation of abdominal fat increase cholesterol deposits in the coronary arteries and raise the risk of other comorbidities such as heart failure, atrial fibrillation, sleep apnea, and stroke [

53].

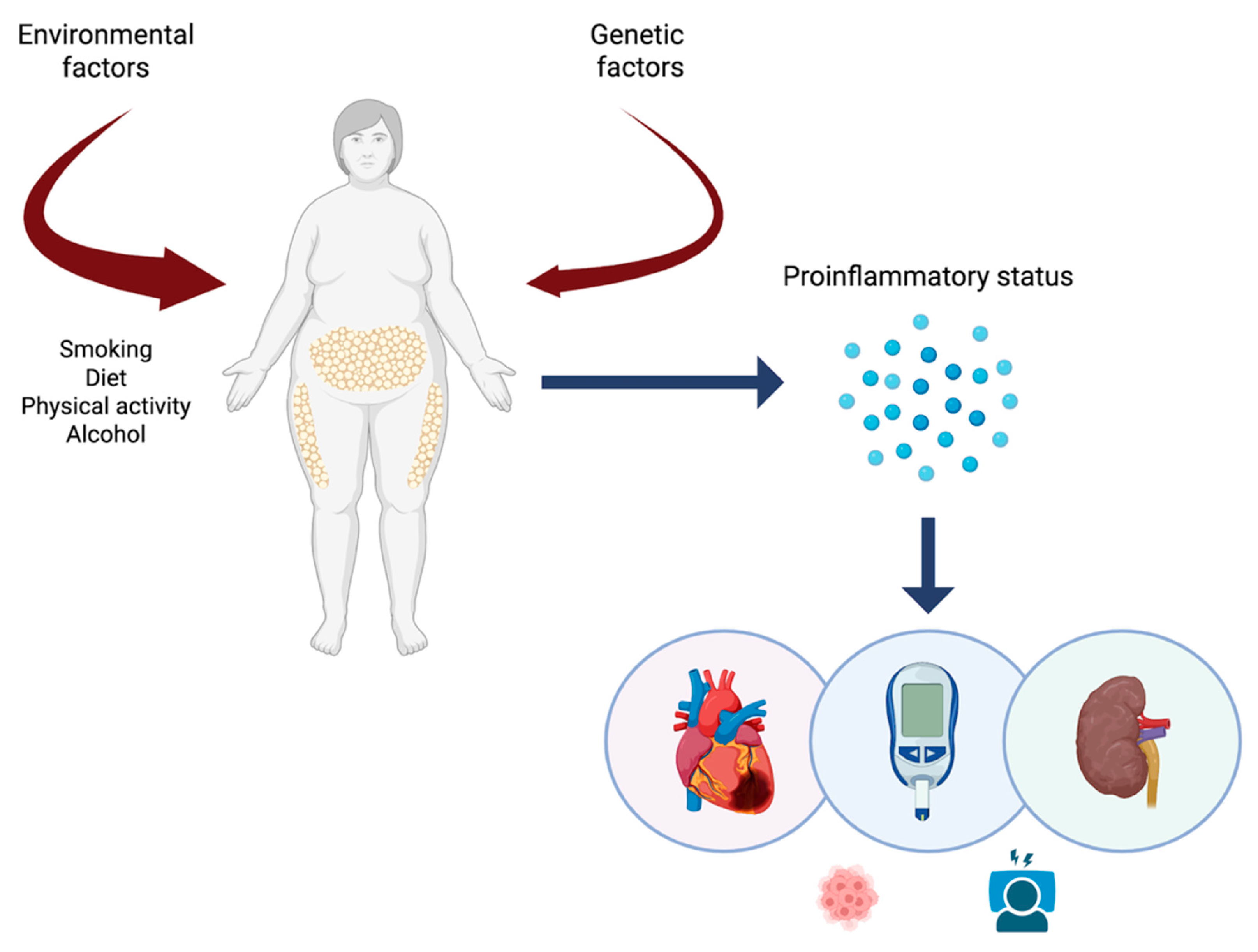

Obesity, cardiovascular and renal diseases are currently encompassed within a syndrome known as cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome (CKM) (

Figure 2). The main objective of the description of this new syndrome is to focus on the pro-inflammatory state within a set of pathologies with similar pathophysiological phenomena, stratify risk, and optimize treatments and preventive measures [

54].

The cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is the result of diseases affecting the organs and systems previously discussed, following exposure to environmental and/or genetic factors. These factors promote a pro-inflammatory state, triggering chronic pathologies based on inflammation and fibrosis. In addition to increasing cardiovascular and renal risk, obesity interferes with sleep physiology and increases the risk of developing neoplasms. All these clinical manifestations are part of a vicious cycle where inflammation is the cornerstone of the pathological process.

5. Obesity, Diabetes and Their Link with Kidney Disease

DM has been rising over the past decade, with an estimated 643 million people diagnosed in 2023. However, this does not account for the undiagnosed patients with Type 2 DM (T2DM) who are unaware that they have this condition in part ascribed to delays in diagnosis or lack of access to diagnostic tools [

36]. T2DM is the most common type of diabetes worldwide, accounting for 90% of cases, and is the result of decreased pancreatic beta-cell function and increased insulin resistance. Although genetics play a role, it is now established that unhealthy lifestyles and lower socioeconomic status are among the main factors that contribute to the development of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus [

55].

DM has a significant impact on quality of life and increases cardiovascular and overall mortality. There is a higher risk of macrovascular complications such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, while microvascular complications include diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic neuropathy [

55,

56]. The increase in adipose tissue in obesity leads to the previously mentioned pro-inflammatory state, promoting insulin resistance. As a result, the pancreas adjusts to insulin resistance by initially increasing the number of beta-cells. However, the microenvironment created by obesity—characterized by hypoxia, mitochondrial dysfunction, and fibrosis—increases oxidative stress, resulting in beta-cell dysfunction and eventually leading to reduced beta-cell mass [

55].

Therefore, obesity and diabetes have a bidirectional and intertwined relationship enhanced by kidney disease: obesity decreases the function of beta-cells, thereby increasing insulin resistance, which in turn leads to hyperglycemia and consequently to T2DM. Conversely, patients with T2DM who have higher baseline insulin resistance can contribute to obesity due to elevated insulin levels and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis [

55]. There is also a correlation between obesity and DM in the risk of development of kidney and cardiovascular diseases [

57].

6. Challenges of New Managements of Obesity and Kidney Disease

6.1. Lifestyle Interventions and Traditional Drugs

Glucose monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, and regular exercise should be the first option and the cornerstones of treatment. Many overweight individuals and patients with obesity might also reverse this condition or delay diseases progression [

58].

Traditionally, the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs) has served as a fundamental treatment to slow the deterioration of renal function by reducing the state of renal hyperfiltration, as demonstrated by the RENAAL (losartan) and IDNT (ibersartan) studies. However, the residual risk, despite standard treatments, continued to be a risk factor for major adverse events [

59,

60].

6.2. The emerging Treatments of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: Incretin-Based Therapies and Gliflozins

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a gastrointestinal peptide secreted by the intestinal tract that enhances insulin release and decreases glucagon concentration under normal physiological conditions. Therefore, it represents a class of drugs based on the entero-insular axis, capable of modulating insulinotropic activity [

61]. GLP-1 receptor agonists work by decreasing gastric emptying, increasing sensation of fullness hence improving weight loss in addition to lifestyle changes [

62].

The benefits of GLP-1 are numerous. Firstly, they have been described as playing an important role in controlling inflammation and reducing endothelial dysfunction. Additionally, they improve lipid metabolism and lower blood pressure due to their natriuretic effect [

63,

64]. Their cardiac benefits reducing major adverse cardiac events (MACE) have also been reflected in several studies, such as: LEADER trial (Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes) [

65], SUSTAIN-6 (Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes With Semaglutide in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes) [

66], REWIND trial (Dulaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes) [

67], HARMONY Outcomes (Effects of Albiglutide on Major Cardiovascular Events In Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus) [

68], SELECT trial (Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes) [

69], and SOUL trial (Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Type 2 Diabetes) [

70].

Additionally, the renal benefits of GLP-1 have been described in patients with obesity with or without T2DM through studies such as the AMPLITUDE-O trial (Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Efpeglenatide in Type 2 Diabetes), which demonstrated a reduction in albuminuria and less deterioration of renal function in the efpeglenatide group [

71]. Additionally, the AWARD-7 trial (Dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD) demonstrated a reduction in insulin use in patients treated with dulaglutide and a lower incidence of the combined endpoint of progression to ESKD or reduction in glomerular filtration rate [

72]. The LEADER and SUSTAIN-6 trials demonstrated a reduction in MACE as well as a decrease in the progression of CKD due to a reduction in albuminuria [

65,

66]. The FLOW trial (Effect of semaglutide versus placebo on the progression of renal impairment in people with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease) demonstrated that subcutaneous semaglutide was associated with a risk reduction in MACE in patients with overweight or obesity and established cardiovascular disease without a history of diabetes [

73]. The SMART (Semaglutide in patients with overweight or obesity and chronic disease without diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical) trial also established that semaglutide treatment for 24 weeks resulted in a clinically meaningful reduction in albuminuria in patients with overweight/obesity and non-diabetic CKD [

74].

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), also called gliflozins or flozins, have proven to be a fundamental pillar in the treatment of CKM syndrome due to their inhibition of sodium and glucose reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubule, promoting urinary glucose excretion and osmotic diuresis [

75]. The success of this class of drugs is based on an insulin-independent mechanism that involves Na+/K+-ATPase and subsequently the transport of glucose across the basolateral membrane to enter the bloodstream [

76].

There are sufficient clinical trials demonstrating the effectiveness of SGLT-2 inhibition in the treatment of hyperglycemia, while also enhancing blood pressure control, promoting weight loss, and reducing the risk of developing MACE [

77]. From a renal perspective, the CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes with Establised Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation) [

78], DAPA-CKD (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease) [

79], and EMPA-KIDNEY (Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease) trials have shown a reduction in major adverse renal events (MARE), including decreases in albuminuria, mortality, and progression to CKD [

80].

Although it is not a group of drugs focused in obesity, finerenone is a highly selective non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; its binding blocks the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators involved in the expression of pro-inflammatory and profibrotic factors. The FIDELIO-DKD (Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes) and FIGARO-DKD (Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes) studies demonstrated a reduction in MACE and MARE, with a significant reduction in albuminuria levels compared to the control group [

81,

82].

6.3. Bariatric Surgery and Alternative Weight Loss Procedures

Bariatric surgery allows good long-term outcomes such as reduction in body weight, reduction of cardiovascular diseases, better glycemic control and enhanced quality of life [

83]. This surgery is offered to people with BMI ≥ 40 Kg/m

2 that struggle to lose weight even with improvements in lifestyle and exercise, or people that have a BMI of 35 or higher with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, T2DM or MS. Several studies have demonstrated improvements in eGFR and inflammatory biomarkers, as well as remission of albuminuria, following bariatric surgery [

84,

85,

86,

87]. Nevertheless, these invasive procedures are often associated with long-term side effects [

84,

88,

89]. Other procedures such as gastric emptying systems or intragastric balloons have been proposed to achieve weight loss and therefore better glycemic control. However, studies regarding the long-term efficacy and safety of these devices are scarce [

90].

7. Conclusions

Obesity is associated with diseases that increase the morbidity and mortality of individuals. While obesity is related to the development of cardiovascular diseases and their associated complications, CKD is of vital importance, as it represents the continuation of the vicious cycle of inflammation, with bidirectional deleterious effects. Currently, obesity-focused treatments also benefit patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and CKD. The key to these new treatments is breaking the toxic cycle of inflammation in order to reduce its adverse effects in both the short and long term. The treatment of CKM syndrome aims to improve the associated comorbidities of obesity through a holistic approach.

Funding

This research was funded by ISCIIII-FEDER and ISCIII RETICS REDinREN, grant number PI21/01292 and PI24_00852, ERA PerMed JTC2022 grant number AC22/00029, Río Hortega CM23/00213, Marató TV3 421/C/2020, Marató TV3 215/C/2021, and RICORS RD21/0005/0016. Enfermedad Glomerular Compleja del Sistema Nacional de Salud (CSUR), enfermedades glomerulares complejas.

Acknowledgments

Juan León-Román performed this work within the basis of his thesis at the Departamento de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

JLR and MJS collaborated on the original idea and review design. JLR, MJS, AE, SND, TA, MLM and JRF contributed to the review of papers. JLR, MJS, AE, SND, TA, MLM, AC, AL and JRF wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Figures were created in BioRender.

https://BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

M.J.S. reports personal fees from NovoNordisk, Jansen, Mundipharma, AstraZeneca, Esteve, Fresenius, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Vifor, ICU, Pfizer, Bayer, Travere Therapeutics, GE Healthcare and grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the current study. J.R.F. reports personal fees from NovoNordisk, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Merck, Bayer, Sanofi, Eurofarma, outside the current study. AC has received speaking fees from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Menarini and research grants from Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk and Menarini. Member of the DMC of Boehringer Ingelheim. AL declares having received fees for conferences from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Pronokal; for clinical trials from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly and Novo Nordisk; grants and scholarships for research from Diputació de Lleida, Instituto de Salud Carlos III and Pfizer; by Advisory Board from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pronokal and by being contracted by the Institut Català de la Salut (ICS).

References

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; Roux CW le Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. The Lancet. 2024, 404, 972–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. News-room fact-sheets detail obesity and overweight. Online, URL: https://www who int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. 2020.

- Ng, M.; Gakidou, E.; Lo, J.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, N.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2025, 405, 813–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, K.; Kuah, R.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Lam, T.K.T. Obesity and the kidney: mechanistic links and therapeutic advances. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 321–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Després, J.P. Body Fat Distribution and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2012, 126, 1301–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto L, Dicker D, Frühbeck G, Halford JCG, Sbraccia P, Yumuk V, et al. A new framework for the diagnosis, staging and management of obesity in adults. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 2395–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Lin, Q.; Chen, K.; Zheng, F.; Wu, J.; et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7, e2415051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeck, G.; Busetto, L.; Dicker, D.; Yumuk, V.; Goossens, G.H.; Hebebrand, J.; et al. The ABCD of Obesity: An EASO Position Statement on a Diagnostic Term with Clinical and Scientific Implications. Obes Facts. 2019, 12, 131–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, K.J.; Kovesdy, C.; Langham, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Jha, V.; Zoccali, C. A single number for advocacy and communication—worldwide more than 850 million individuals have kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1048–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.R.; Grams, M.E.; Ballew, S.H.; Bilo, H.; Correa, A.; Evans, M.; et al. Adiposity and risk of decline in glomerular filtration rate: meta-analysis of individual participant data in a global consortium. BMJ 2019, 364, k5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carro, C.; Vergara, A.; Bermejo, S.; Azancot, M.A.; Sellarés, J.; Soler, M.J. A Nephrologist Perspective on Obesity: From Kidney Injury to Clinical Management. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, K.A.; Kramer, H.; Bidani, A.K. Adverse renal consequences of obesity. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2008, 294, F685–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Qin, Z.; Hua, F. Adiponectin protects obesity-related glomerulopathy by inhibiting ROS/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammation pathway. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; do Carmo, J.M.; da Silva, A.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, M.E. Obesity-Induced Hypertension. Circ Res. 2015, 116, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdomo, C.M.; Cohen, R.V.; Sumithran, P.; Clément, K.; Frühbeck, G. Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults. The Lancet. 2023, 401, 1116–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soták, M.; Clark, M.; Suur, B.E.; Börgeson, E. Inflammation and resolution in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; do Carmo, J.M.; da Silva, A.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, M.E. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: mechanistic links. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019, 15, 367–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffa, J.F.; McAinch, A.J.; Poronnik, P.; Hryciw, D.H. Adipokines as a link between obesity and chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2013, 305, F1629–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyciński, J.; Dziedziejko, V.; Puchałowicz, K.; Domański, L.; Pawlik, A. Adiponectin in Chronic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyvis, K.; Verrijken, A.; Wouters, K.; Van Gaal, L. Plasma adiponectin level is inversely correlated with albuminuria in overweight and obese nondiabetic individuals. Metabolism. 2013, 62, 1570–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Bae, E.H.; Hu, A.; Liu, G.C.; Zhou, X.; Williams, V.; et al. Deletion of the gene for adiponectin accelerates diabetic nephropathy in the Ins2 +/C96Y mouse. Diabetologia. 2015, 58, 1668–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine, R.V. Increased Serum Leptin Indicates Leptin Resistance in Obesity. Clin Chem. 2011, 57, 1461–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Rui H liang Yang, M.; Sun L jun Dong H rui Cheng, H. CD36-Mediated Lipid Accumulation and Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Lead to Podocyte Injury in Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy. Mediators Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rampanelli, E.; Orsó, E.; Ochodnicky, P.; Liebisch, G.; Bakker, P.J.; Claessen, N.; et al. Metabolic injury-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation dampens phospholipid degradation. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, B.; Shen, W.; Fang, X.; Wu, Q. The NLPR3 inflammasome and obesity-related kidney disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2018, 22, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Kimura, T.; Namba, T.; Matsuda, J.; et al. High-Fat Diet–Induced Lysosomal Dysfunction and Impaired Autophagic Flux Contribute to Lipotoxicity in the Kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017, 28, 1534–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, H.; Han, M.; Ren, X.; et al. Obesity and chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2023, 324, E24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovre, D.; Shah, S.; Sihota, A.; Fonseca, V.A. Managing Diabetes and Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018, 47, 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkov, V.A.; Zharikova, A.A.; Demchenko, E.A.; Andrianova, N.V.; Zorov, D.B.; Plotnikov, E.Y. Gut Microbiota as a Source of Uremic Toxins. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Contreras, B.E.; Morán-Ramos, S.; Villarruel-Vázquez, R.; Macías-Kauffer, L.; Villamil-Ramírez, H.; León-Mimila, P.; et al. Composition of gut microbiota in obese and normal-weight Mexican school-age children and its association with metabolic traits. Pediatr Obes. 2018, 13, 381–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneth, B. Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance in Patients with Obesity. Endocrines. 2024, 5, 153–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coward, R.; Fornoni, A. Insulin signaling. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015, 24, 104–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, G.I.; Hale, L.J.; Eremina, V.; Jeansson, M.; Maezawa, Y.; Lennon, R.; et al. Insulin Signaling to the Glomerular Podocyte Is Critical for Normal Kidney Function. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piwkowska, A.; Rogacka, D.; Kasztan, M.; Angielski, S.; Jankowski, M. Insulin increases glomerular filtration barrier permeability through dimerization of protein kinase G type Iα subunits. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2013, 1832, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, M.; Roth, G.A.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abate, K.H.; Abate, Y.H.; et al. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024, 403, 2162–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, D.L.; Simpkins, C.E.; Thompson, R.E.; Locke, J.E.; Warren, D.S.; Montgomery, R.A. Obesity Impacts Access to Kidney Transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008, 19, 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, C.; Schold, J.D. Measuring Transplant Center Performance: the Goals Are Not Controversial but the Methods and Consequences Can Be. Curr Transplant Rep. 2017, 4, 52–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, A.P.J.; Ruggenenti, P.; Ruan, X.Z.; Praga, M.; Cruzado, J.M.; Bajema, I.M.; et al. Fatty kidney: emerging role of ectopic lipid in obesity-related renal disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P.; Furth, S.L.; Zoccali, C.; Tao Li, P.K.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Benghanem-Gharbi, M.; et al. Obesity and kidney disease: hidden consequences of the epidemic. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 260–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agati, V.D.; Chagnac, A.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Levi, M.; Porrini, E.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; et al. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: clinical and pathologic characteristics and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016, 12, 453–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, N.; Okabayashi, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Yokoo, T. The Renal Pathology of Obesity. Kidney Int Rep. 2017, 2, 251–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, S.; Chinnadurai, R.; Al-Chalabi, S.; Evans, P.; Kalra, P.A.; Syed, A.A.; et al. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: A current review. Obes Sci Pract. 2023, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambham, N.; Markowitz, G.S.; Valeri, A.M.; Lin, J.; D’Agati, V.D. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: An emerging epidemic. Kidney Int. 2001, 59, 1498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Díaz, M.; López-Martínez, M. The Role of miRNAs as Early Biomarkers in Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy: Implications for Early Detection and Treatment. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, W.; Lemley, K.V. A Potential Role for Mechanical Forces in the Detachment of Podocytes and the Progression of CKD. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015, 26, 258–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, A.P.J.; Ruggenenti, P.; Ruan, X.Z.; Praga, M.; Cruzado, J.M.; Bajema, I.M.; et al. Fatty kidney: emerging role of ectopic lipid in obesity-related renal disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, M.; Armengol, M.P.; Pey, I.; Farré, X.; Rodríguez-Martínez, P.; Ferrer, M.; et al. Integrated miRNA–mRNA Analysis Reveals Critical miRNAs and Targets in Diet-Induced Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinas, K.C.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Antoniades, C.; Blüher, M.; Gorter, T.M.; Hanssen, H.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: an ESC clinical consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 4063–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, M.D.; West, H.W.; Antoniades, C. Adipose Tissue in Cardiovascular Disease: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation. Annu Rev Physiol. 2024, 86, 175–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2021, 592, 524–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Almahmeed, W.; Bays, H.; Cuevas, A.; Di Angelantonio, E.; le Roux, C.W.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: mechanistic insights and management strategies. A joint position paper by the World Heart Federation and World Obesity Federation. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023, 148, 1606–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7, e009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, O.; Reyes-García, R.; Modrego-Pardo, I.; López-Martínez, M.; Soler, M.J. Are we ready for an adipocentric approach in people living with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease? Clin Kidney J. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Butryn, M.L. Lifestyle modification approaches for the treatment of obesity in adults. Am Psychol. 2020, 75, 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Grunfeld, J.P.; Keane, W.F.; Kurokawa, K.; et al. The losartan renal protection study — rationale, study design and baseline characteristics of RENAAL (Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan). Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2000, 1, 328–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J. The role of angiotensin II receptor blockers in preventing the progression of renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens. 2002, 15, 123S–128S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Wang, Q.W.; Yang, X.Y.; Yang, W.; Li, D.R.; Jin, J.Y.; et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity: Role as a promising approach. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1085799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.R.; Drucker, D.J. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: cardiovascular benefits and mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023, 20, 463–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez Fernández, A.B.; Vergara Arana, A.; Olivella San Emeterio, A.; Azancot Rivero, M.A.; Soriano Colome, T.; Soler Romeo, M.J. Cardiorenal syndrome and diabetes: an evil pairing. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 10, 1185707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Fontalvo, J.; Reina, M.; Soler, M.J.; Unigarro-Palacios, M.; Castañeda-González, J.P.; Quintero, J.J.; et al. Kidney effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 (GLP1): from molecular foundations to a pharmacophysiological perspective. Brazilian Journal of Nephrology 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016, 375, 311–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016, 375, 1834–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019, 394, 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.B.; Hernandez, A.F.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Granger, C.B.; Janmohamed, S.; Jones, N.P.; et al. Harmony Outcomes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the effect of albiglutide on major cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus—Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am Heart J. 2018, 203, 30–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023, 389, 2221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, D.K.; Marx, N.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Deanfield, J.E.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Pop-Busui, R.; et al. Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in High-Risk Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Sattar, N.; Rosenstock, J.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Pratley, R.; Lopes, R.D.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Efpeglenatide in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021, 385, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Lakshmanan, M.C.; Rayner, B.; Busch, R.S.; Zimmermann, A.G.; Woodward, D.B.; et al. Dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (AWARD-7): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 605–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gragnano, F.; De Sio, V.; Calabrò, P. FLOW trial stopped early due to evidence of renal protection with semaglutide. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2024, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apperloo, E.M.; Gorriz, J.L.; Soler, M.J.; Cigarrán Guldris, S.; Cruzado, J.M.; Puchades, M.J.; et al. Semaglutide in patients with overweight or obesity and chronic kidney disease without diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nat Med. 2025, 31, 278–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Jacobs-Cacha, C.; Llorens-Cebria, C.; Ortiz, A.; Martinez-Diaz, I.; Martos, N.; et al. Enhanced Cardiorenal Protective Effects of Combining SGLT2 Inhibition, Endothelin Receptor Antagonism and RAS Blockade in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 12823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Jacobs-Cachá, C.; Soler, M.J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors: beyond glycaemic control. Clin Kidney J. 2019, 12, 322–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordan, L.; Gaita, L.; Timar, R.; Avram, V.; Sturza, A.; Timar, B. The Renoprotective Mechanisms of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (SGLT2i)—A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Jardine, M.J.; Neal, B.; Bompoint, S.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; et al. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019, 380, 2295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020, 383, 1436–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group, Herrington WG, Staplin N, Wanner C, Green JB, Hauske SJ, et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 117–27.

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020, 383, 2219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippatos, G.; Anker, S.D.; Agarwal, R.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G.L.; et al. Finerenone Reduces Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Analyses From the FIGARO-DKD Trial. Circulation. 2022, 145, 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, L.; Narbro, K.; Sjöström, C.D.; Karason, K.; Larsson, B.; Wedel, H.; et al. Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Mortality in Swedish Obese Subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007, 357, 741–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Díaz, M.; Serra, A.; Romero, R.; Bonet, J.; Bayés, B.; Homs, M.; et al. Effect of Drastic Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery on Renal Parameters in Extremely Obese Patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006, 17 (12_suppl_3), S213–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Lu, J.; Dai, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, S.; et al. Improvement of Renal Function After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2021, 31, 4470–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zou, J.; Ye, Z.; Di, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Renal Function in Obese Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0163907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.; Porrini, E.; Martin-Taboada, M.; Luis-Lima, S.; Vila-Bedmar, R.; González de Pablos, I.; et al. Renoprotective role of bariatric surgery in patients with established chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2021, 14, 2037–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, M.; Yousef, A.; Alkhawaldeh, I.; Al-Jafari, M.; Zuaiter, S.; Zein Eddin, S. Dumping Syndrome after Bariatric Surgery. Ann Ital Chir. 2024, 95, 522–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambioli, R.; Lepore, E.; Biondo, F.G.; Bertolani, L.; Unfer, V. Risks and limits of bariatric surgery: old solutions and a new potential option. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023, 27, 5831–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gulinac, M.; Miteva, D.G.; Peshevska-Sekulovska, M.; Novakov, I.P.; Antovic, S.; Peruhova, M.; et al. Long-term effectiveness, outcomes and complications of bariatric surgery. World J Clin Cases. 2023, 11, 4504–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).