1. Introduction

Climate and ecological emergencies are exacerbating the problems related to provision and control of water resources. Water scarcity, droughts, floods, pollution and extreme weather events are especially threatening isolated and poor communities. United Nations Agenda 2030 addresses a specific Sustainable Development Goal (SDG # 6) to the general problem of “Clean water and sanitation”, highlighting that the availability of clean water is strictly connected to many health issues. Unfortunately, as dramatically illustrated in the latest United Nations report [

1], the actions to meet the SDG have not yielded any significant improvement in any of the 8 targets (with no one being met or on track, and one even regressing since 2015), while the general Agenda itself at halfway is globally failing at all scales [

1]. Nevertheless, the attention of global policies remains mostly addressed to large-scale interventions, with systemic water-related actions involving large communities and socio-economic infrastructures. On the other hand, many small communities or groups struggle worldwide every day for getting clean water at a local small scale, with difficulty in water provision that can be relevant in a wide range of situations: isolated villages that do not have access to uncontaminated water, overcrowded urban sectors in megalopolis slums, groups of people living within or close to an armed conflict area, public structures hosting children or other fragile people groups such as schools, hospitals, infirmaries or shelters. For them, the access to safe drinking and sanitation water is a matter of everyday survival. For example, Dharavi slum in Mumbai, India, counts for about 1,000,000 dwellers, with an astonishing population density of 418,000 people per km

2 (

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharavi), and contaminated water is one of the major causes of diseases and deaths. In this work

, we present a sustainability assessment of an innovative portable solar still which has been specifically designed to be used by small groups of people in situations where the only accessible water is either salty or contaminated, and both transportation and electricity provision is uncertain or insecure. The solar still design takes into account several sustainability factors. It is made of cheap and durable materials, does not requires specific maintenance nor any training to be operated, and the only used energy source is a small photovoltaic (PV) module (power < 20 W). As described in the following, the solar still has been set up and tested in different places worldwide, using some original technical solutions allow to reach surprisingly high performances. By the Emergy accounting method, in this work we show some intrinsic sustainability characteristics of the apparatus, compared with industrial larger-scale methods commonly used for water desalination and purification. In the spirit of H.T. Odum’s work and legacy, the use of emergy accounting provides a privileged perspective for realizing an integrated sustainability assessment, allowing to determine the actual contributions of both environment and humans in the operation of the solar still.

2. Materials and Methods

The solar still. The solar still, named SOLWA™ (from SOLar WAter), was developed some years ago [

2], yet it has never been the object so far of a quantitative assessment such as that provided by the emergy accounting method. Nevertehless, it has already drawn the interest of several nongovernmental and intergovernmental organisations, such as the United Nations, which awarded the solar still SOLWA™ within the programme IDEASS, Innovation for Development and South-South Cooperation (

www.ideassonline.org).

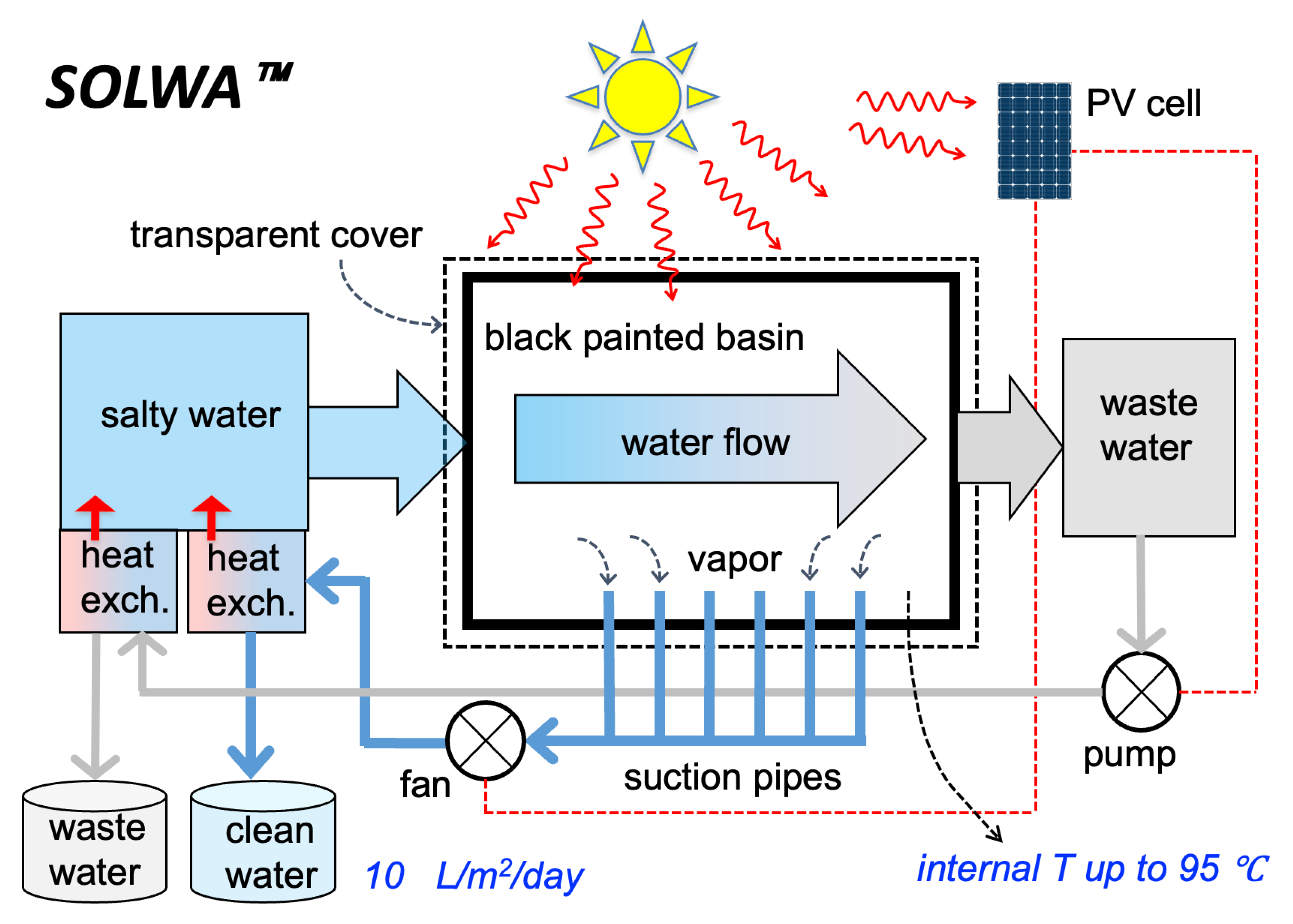

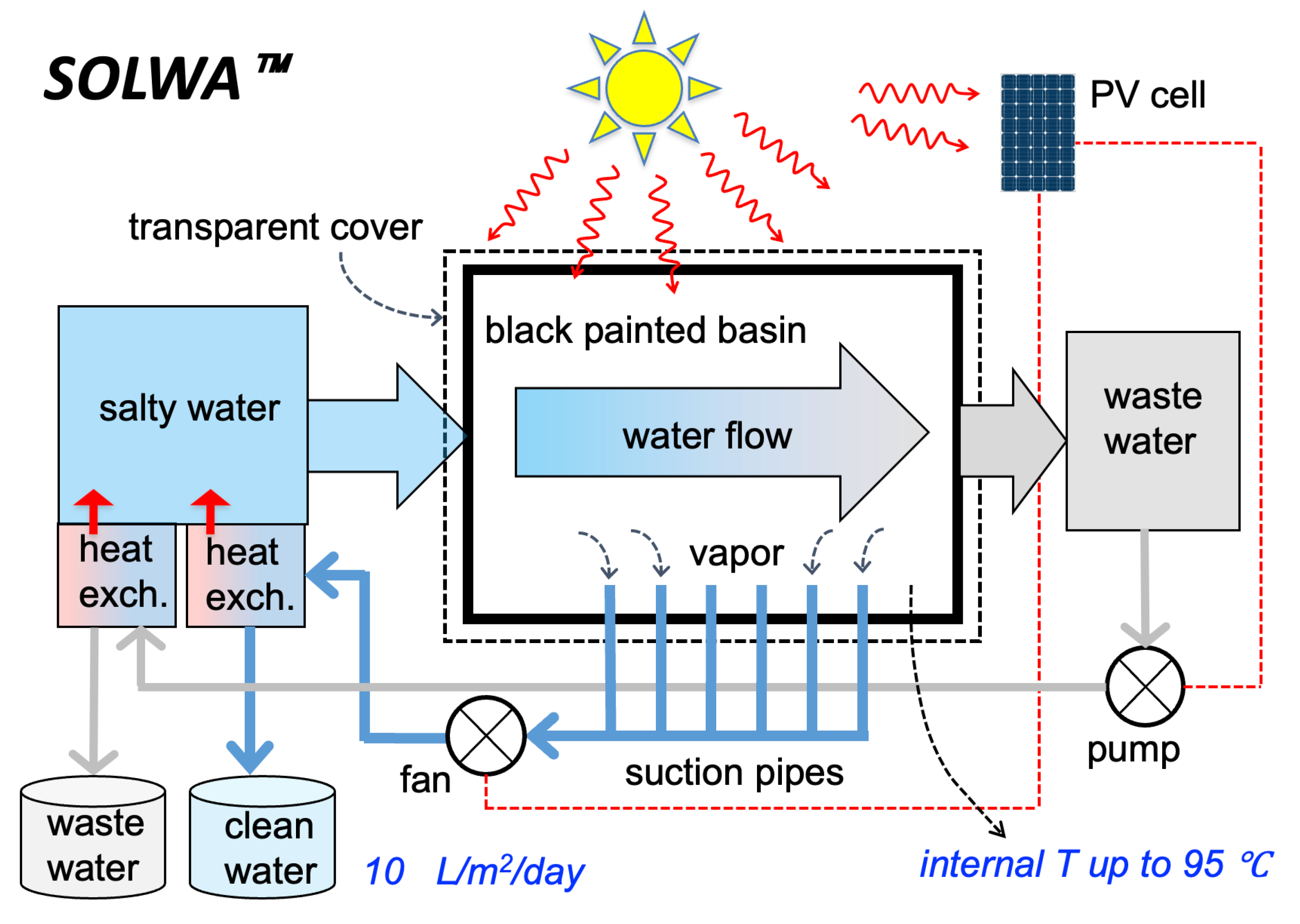

Figure 1 illustrates the basic features of SOLWA™.

Its fundamental operation is based on the exploitation of the greenhouse effect, like for classical solar stills. Solar radiation penetrates through a transparent cover and is absorbed by a darkened basin, allowing purified or desalinated evaporated water to be collected and used. The distinguishing characteristic of SOLWA™ is the incorporation of new enhanced technological solutions, shown in

Figure 1.

First, a controllable continuous water flow is realized throughout the operation and the extraction, helping to prevent scaling and stagnation. Water flow is controlled by properly setting the slope of the black basin of the solar still, in order to maximize the operation efficiency depending on the specificity of the situation. Enhanced evaporation rate is obtained by continuously remove moist air routed into copper suction pipes. The condensation of vapor inside these pipes releases heat back into the incoming saline solution, enhancing the system’s overall efficiency. A small fan at the solar still’s inlet supports circulation, powered entirely by a photovoltaic panel, ensuring complete operational autonomy without reliance on external power sources. In particular, the photovoltaic panel powers both a fan and a small water pump, that makes the residual waste water enter a second heat exchanger and release the heat to the incoming water at the entrance of the apparatus, thus further enhancing the efficiency.

As indicated in

Figure 1, the air temperature inside the solar still can typically reach 95°C, while the exiting brine, which can reach temperatures near 100°C, is not discarded but redirected through a counterflow heat exchanger, transferring heat to the incoming contaminated or seawater. This configuration also addresses several common issues associated with traditional solar stills, in particular, it prevents the formation of vapor condensation on the cover, since humidity is carried out by the suction pipes, preserving the sunlight transmission into the apparatus. Moreover, algae or bacteria growth on the covering, which could contaminate the purified water, is also prevented. These solutions overccome the problems related to very low efficiency, as well as the need for continuous maintenance.

SOLWA™ is an adaptable apparatus, which can be designed tailoring its parameters and characteristics on the basis of contingent environment. The factors that are taken into account in the solar still design, based on the respective actual context, are summarized in

Table 1.

Several prototypes have been constructed and tested in different contexts in Paraguay, Colombia, Senegal, Mozambique, Burkina Faso, Palestine, Peru, India, Yemen. For each case, the structure was designed such to optimize the clean water provision depending on the specific need, the environmental inputs, the availability of materials, the social context and the state of the water to be purified of desalinated.

Figure 2 shows some of these prototypes.

Emergy assessment. Emergy accounting (EMA) is drawing an ever increasing interest as a quantitative metric to evaluate the integrated sustainability of systems [

3]. Its originality makes it suitable to account for the actual real contribution of environment in the realization of products or services, and for the long term sustainability of the system at issue from a systemic perspective. The basis of emergy theory is the main work of Howard T. Odum [

4], who first introduced the idea of accounting all the resource flows in terms of the new quantity called emergy (from “energy memory”), attributing to each element in a system (i.e., stocks and flows) a quantity of energy computed as the sum of all the available energy (in the same form of solar equivalent energy) used directly or indirectly for the creation of the respective element. The determination of a family of emergy-based indicators [

5] allows to evaluate how much a system relies on the provision of ecosystemic services, and on the balance between renewable and non-renewable resources, including human contributions in terms of labor and services. This also addresses a powerful tool for comparing different scenarios or different solutions for environmental and socio-economic issues, thanks to a systemic approach that automathically takes into account synergies and trade-offs linking the system with its environment and with further systems with which it exchanges resources. Moreover, emergy accounting may address the existence of systemic leverage points, either negative or positive, useful in terms of policy-making procedures and environmental planning actions. Generally speaking, emergy assessment shifts the attention from the user-side perspective to the supply-side one, computing the overall upstream investment coming from both Nature and human-based activities. This allows to overcome sustainability metrics based on anthropocentric concepts, including monetary ones, taking back the description of a system sustainability on calculations ultimately derived from the principles of Thermodynamics. From an operational point of view, EMA uses complete inventories of all resource contributions to a system operation by converting each quantity in the same unit of solar emergy. The conversions are made using a list of coefficients (Unit Emergy Values, UEVs) constantly updated and published by the Environmental Protection Agency of the USA [

6]. It is worth noting that also other metrics uses similar inventories (yet not expressed under the same unit), in particular, the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methods. Nevertheless, LCA provides information about the resource and environmental cost of a given product or process accounting for matter and energy flows occurring under human control, whereas environmental services and flows which are not associated to significant matter and energy carriers, such as labor and information, are typically not included. This allows to address mainly the Environmental and monetary impacts (pollution, income) in the user-side perspective. Conversely, EMA measures the environmental performances of the system on a global scale, taking into account also all the “free” environmental inputs as well as the indirect environmental support embodied in human labor and services. The environmental cost to produce resources addresses therefore the degree of their renewability and availability, making the emergy method an ideal counterpart complementary to LCA analyses.

3. Results

Figure 3 shows the emergy diagram of the basic SOLWA™ solar still, while

Table 2 reports the corresponding emergy table. Numbers and data are taken form the prototype assembled and used in the village of Trujillo, Peru, where the availability of fresh water was compromised by contamination due to pollution derived from industrual plants present in the region. In particular, the solar still was mounted and operated on the rooftop of a primary school, which needs water for food preparation, drinking and sanitation all day long for the children.

Table 2 reports also the result in terms of specific emergy (sej/litre) of the treated water.

4. Discussion

A first comment should be addressed to labor. In the system at issue, it has to be considered of endogenous nature [

16], a situation shared by all the other cases where we used SOLWA™. In fact, labor is not “imported” as an external resource, but can be done by anybody in the community using the solar still, since it does not require any technical skill nor training. As a matter of fact, it is provided for free and it is limited to an estimated reference time of 10 min/day. This means that labor is not directly linked to the general economy sustaining the community, since it does not involve monetary transactions. Therefore, as Odum himself used to suggest, it can be calculated from the assessment of the metabolic energy consumption. Nevertheless, even if labor calculated in this way accounts for much less emergy than using money-to-emergy value conversion, labor remains by far the major emergy contribution to the solar still operation. Independently of whether it is considered as an internal, external or renewable resource, the assessment indicates therefore that SOLWA™ is designed to comparatively minimise all the emergy contributions by non-human sources. We may say that, contrary to other usual systems and situations, technology solutions have been designed ab initio towards sustainability rather than economic efficiency. Literature reports only very few papers dedicated to the emergy accounting of purification/desalination systems [

17] (and references therein). Moreover, the use of solar stills is anyway limited by their low efficiency and low yield, with one only emergy accounting study [

14] on a solar still about the same scale of SOLWA™. Compared to the transformity reported by Gude for a comparable solar still, that of SOLWA™ is almost one order of magnitude lower (5.24E+13 versus 3.45E+14 sej/m

3), indicating a much higher efficiency in producing clean water than other more conventional methods. Thus, in the case of SOLWA™, the technological set up allows to improve not only the yield per area and the economic efficiency, but also the resource use efficiency measured by EMA, pointing out a suitable solution at the local community scale. As concerns the traditional emergy indicators usually addressed to determine the sustainability performances of a systrem, they are scarcely indicative. Besides the Transformity, the three indicators most commonly used to assess the performances of a system are the Emergy Yield Ratio (EYR), the Environmental Loading Ratio (ELR) and the Emergy Sustainability Index (EYR/ELR). EYR is the ratio of the emergy yield from a process to the emergy invested, a measure of the ability of a process to exploit and make available local resources by investing outside resources. The obtained values for SOLWA™ are 1.32 and about 1.00 without and with Labor and Services, respectively. These values apparently address low performances for the system, but Odum himself warned about the attribution of a direct meaning to this indicator, that can tell us different things depending on the specificity of the system. Indeed, SOLWA™ cannot be considered as a productive system in the same sense usually attributed to several analyzed products or services. In fact, the contribution of SOLWA™ to the community economy should be accounted for in terms of opportunity cost saving, since the solar still allows to save significant resources for the Trujillo School, that without it should have to activate expensive procedures to get the clean water anyway, given its environmental and socio-economic situation. ELR is the ratio of nonrenewable to renewable emergy use, an indicator of the pressure of a transformation process on the environment. In our study, the obtained values for ELR are about 3 and 194 without and with labor, respectively, indicating the ineffectiveness of this indicator to describe a system that does not carry any significant pressure on the environment, whether labor is accounted or not. This confirms that how to compute and into which category to include human labor in EMA is still matter of debate [

18,

19], since the very meaning of the flows categories defined to evaluate the emergy indicators are, in the case of labor, much system-dependent. The uncertainty in the significance of these indicator values reflects also in the ESI index, that results in our case lower than 1.

5. Conclusions

Emergy accounting has been applied to the SOLWA™ solar still. The apparatus configuration is characterized by some peculiarities that make it suitable for the provision of fresh water in small communities, namely:

no need for external power source network or fuel (PV cell power <20 W);

no need for frequent maintenance;

easiness of building up and operation (no need for trained personnel);

low cost, almost limited to the building up investement some hundreds USD);

adaptability to specific needs of small communities;

portability;

flexible design (materials, size, heating, depending on the specific use and site).

Specific emergy of purified water results of 1.01E+12 sej/m3 without L&S and 5.24E+13 sej/m3 with L&S, much lower than similar more conventional solar stills. In the 6th SDG perspective, SOLWA™ story also addresses some further comments: first of all, SOLWA™ is economically very convenient for needy and poor communities, yet without generating profit. Second, its adaptability makes it useful for local peculiar situations, while it cannot constitute a basic element for water provision networks. These facts drew the attention of NGOs and public institutions (UN), but at the same time prevented SOLWA™ to enter any market or political planning. Also in the framework of the UN 2030 Agenda, this indicates the need to elaborate policy-making actions specific at small scales, since neglecting the local situations of small communities can affect in the long term the social and economical stability of entire regions. A final comment must be made on the legacy of H.T. Odum’s theory, applied to a system that is not aimed at profitable production. The presented results in this case address a system that exploits resource flows in a much sustainable way, minimizing the energy carried by environmental inputs, at the same time using human-based resources that are outside market dynamics. The donor-side perspective at the basis of the emergy theory appears to be the natural framework for computing the energy investments for the solar still functioning, whereas more popular methods, like those based on Life Cycle Assessment and Exergy Analysis, result unable to capture all the aspects related to the sustainability of a system.

Author Contributions

F.G.: conceptualization, methodology, writing and original draft preparation; P.F.: conceptualization, validation, investigation and formal analysis; L.C. and F.S.: review and editing; S.C.: data curation, review and editing.

Funding

S.C. contributed to this study within the RETURN Extended Partnership and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (National Recovery and Resilience Plan – NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3 – D.D. 1243 2/8/2022, PE0000005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| LCA |

Life Cycle assessment |

| EMA |

Emergy Accounting |

| EYR |

Emergy Yield Ratio |

| ELR |

Environmental Loading Ratio |

References

- Sachs, J.D., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the future. Sustainable development report 2024. SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Franceschetti, P.; Gonella, F. New solar still with the suction of wet air: a solution in isolated areas. J. Fund. Renewable Energy and Appl. 2012, 2, R120315. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Webber, M.; Chen, J. Bibliometric and visualized analysis of emergy research. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 90, 285-293. [CrossRef]

- Odum, H.T. Environmental Accounting, Emergy and Environmental Decision Making. Wiley: New York, US, 1996.

- Brown, M.T.; Ulgiati, S. Emergy-based indices and ratios to evaluate sustainability: monitoring economies and technology toward environmentally sound innovation. Ecol. Eng. 1997, 9, 51-69.

- De Vilbiss, C.; Arden, S.; Brown, M.T.; Campbell, D.; Ma, X.; Ingwersen, W. The unit emergy value (UEV) library for characterizing environmental support in Life Cycle Assessment. U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC, 2024. https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?dirEntryId=364052&Lab=CESER.

- Brown, M.T.; Campbell, D.E.; De Vilbiss, C.; Ulgiati, S. The geobiosphere emergy baseline: a synthesis. Ecol. Model. 2016, 339, 92-95. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Ulgiati, S. Assessing the global environmental sources driving the geobiosphere: a revised emergy baseline. Ecol. Model. 2016, 2016339, 126-132. [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.; Amer, M.; Tatarinov, F; Segev, L.; Rotenberg., R.; Yakir, D. “Solar Panels Forest” and its radiative forcing effect: preliminary results from the Arava Desert. EGU2020-18924, updated on 29 Jun 2023. [CrossRef]

- De Vilbiss, C.; Brown, M.T. The emergy characterization factor library for characterizing environmental support in life cycle assessment. Final technical report to the USEPA. In School of Sustainable Infrastructure and Environment, College of Engineering; Center for Environmental Policy, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, 2015.

- Wu, Z.; Di, D.; Wang, H.; Wu, M.; He, C. Analysis and emergy assessment of the eco-environmental benefits of rivers. Ecol. Ind. 2019, 106, 105472. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Buranakarn, V. Emergy indices and ratios for sustainable material cycles and recycle options. Res. Conserv. Recycling 2003, 38, 1-22.

- Corcelli, F.; Ripa, M.; Ulgiati, S. End-of-life treatment of crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. An emergy-based case study. J. Cleaner Prod. 2017, 161, 1129-1142. [CrossRef]

- Gude, V.G.; Mummaneni, A.; Nirmalakhandan N. Emergy, energy and exergy analysis of a solar powered low temperature desalination system. Desalination and Water Treatment 2017, 74, 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, S.; Cohen, M.J.; King, D.M.; Brown, M.T. Creation of a global emergy database for standardized national emergy synthesis. In Proceedings of the 4th Biennial Emergy Research Conference; Brown, M.T., Ed.; Center for Environmental Policy, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, 2007.

- Kamp, A.; Morandi, F.; Østergård, H. Development of concepts for human labour accounting in emergy assessment and other environmental sustainability assessment methods. Ecol. Ind. 2016, 60, 884-892. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, L. Emergy analysis of seawater desalination system in coastal areas: a case study in Qingdao of China. Env. Develop. Sust. 2024, 26, 14281-14293. [CrossRef]

- Ulgiati, S.; Bargigli, S; Raugei, M. Dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s of emergy synthesis: material flows, information and memory aspects, and performance indicators. In Emergy Synthesis. Theory and Applications of the Emergy Methodology; Brown, M.T., Campbell, D., Comar, V., Huang, S.L., Rydberg, T., Tilley, D.R., Ulgiati, S., Eds; Center for Environmental Policy, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, 2005.

- Ulgiati, S.; Brown, M.T. Labor and services as information carriers in Emergy-LCA accounting. J. Env. Accounting Manag. 2014, 2, 163-170. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).