1. Introduction

Bioinformatics as a field is critically dependent on complex computational algorithms for the analysis of increasingly voluminous biological datasets. Within this context, the reproducibility of results and the operational efficiency of these algorithms are paramount, underpinning both scientific integrity and effective resource management. This report details a study centered on the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST+), a foundational software package in bioinformatics, which addresses pressing issues related to computational reproducibility and performance.

A central problem confronting computational biology is the variability in how different C/C++ compilers and the underlying computer architectures implement floating-point mathematics. These subtle, yet potentially impactful, differences are often inherent in compiler design choices or specific hardware implementations. They can lead to divergent numerical results from ostensibly identical calculations, a concern particularly pronounced in numerically intensive software such as versions of BLAST+. Such discrepancies possess the capacity to undermine the reliability of scientific findings. Concurrently, as biological datasets continue to expand, the performance characteristics of tools like BLAST+ become increasingly critical. Inefficiencies can translate into prohibitive computational costs and unacceptably extended analysis durations.

This report employs a multi-faceted approach to examine these concerns. The main focus is on the general expectations and putative reproducibility of machine code of BLAST+, and scientific software in general, by a range of C/C++ compilers across diverse hardware platforms, with a specific emphasis on variations in floating-point arithmetic and their consequent impact on analytical results. Recommendations include the identification and characterization of performance bottlenecks in software through systematic profiling and code. Targeted optimization strategies includes code restructuring, the judicious use of faster mathematical function libraries, and leveraging machine-specific code, such as Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions. These recommendations contribute to a better understanding of factors affecting the continued reliability and performance of bioinformatics software.

2. Background and Significance

2.1. The Challenge of Floating-Point Arithmetic in Compilers

Different versions and types of C/C++ compilers, notably the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) (Stallman 2003), are known to exhibit inconsistencies in their handling of floating-point mathematics. This behavior, which can sometimes be mischaracterized as a software bug, is often a direct consequence of specific design choices made within the compiler or varying levels of adherence to different aspects of floating-point standards, such as IEEE 754. Floating-point arithmetic is inherently sensitive not only to the precision of the values involved and the nature of the arithmetic operations themselves but also to how undefined values (e.g., Not-a-Number (NaN), infinity) and subnormal numbers are represented and processed. Prior experience in computationally intensive fields, such as software-based video rendering, has highlighted similar precision-related issues that are notoriously difficult to debug. Prior review of the extant scientific literature indicated a notable lack of comprehensive surveys specifically addressing this problem within the domain of bioinformatics software.

2.2. Performance Optimization Precedents

Computational efficiency in demanding applications, for instance, video and audio compression or rendering, has frequently been achieved through the application of low-level optimization techniques (Abrash 1997). These techniques prominently include Instruction-Level Parallelism (ILP), which seeks to utilize the multiple execution pipelines available within modern Central Processing Units (CPUs), particularly their Floating Point Units (FPU). Another key technique is Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD), which employs specialized CPU instructions (e.g., Intel's SSE2, AVX) designed to perform the same operation on multiple data elements simultaneously, typically using wide registers (e.g., 128-bit, 256-bit) (Liu et al. 2013; Rao and Fisher 1993; Alpern et al. 1995). Such methodologies can significantly reduce the number of clock cycles required for critical computational segments.

2.3. Significance for BLAST+ and Bioinformatics

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) provides BLAST+ as a web service for conducting biological sequence database searches (Camacho et al. 2009; NCBI Resource Coordinators 2016). Consequently, any improvements realized in the performance of BLAST+ directly translate to reduced CPU usage and, by extension, lower operational costs for maintaining this vital public resource. A significant increase in performance, for example, a doubling of speed, could potentially halve the server infrastructure costs. The optimization strategies explored within this report are designed to complement existing parallelization efforts already implemented in BLAST+, such as multi-threading. BLAST+, having undergone numerous revisions and being subject to extensive use (as evidenced by over a large number of citations), serves as an ideal model system as a candidate of interest. Its inherent complexity and widespread adoption make it a highly suitable candidate for analyzing issues of computational reliability and performance.

2.4. Benefits of Open Source Development Practices

The source code for BLAST+ has traditionally been distributed as downloadable archives. A transition of its development infrastructure to a web-based version control repository, as in GitHub, is beneficial. The platform fosters greater community engagement, facilitates collaborative development efforts, and improves overall transparency in the software lifecycle. Version control systems enable meticulous tracking of all code modifications, thereby simplifying the debugging process by allowing for straightforward reversion to previous stable states. This approach is often more effective than traditional debugging methods that rely on extensive logging. Past versions of BLAST+ codebase exhibits a mixture of C and C++ programming styles (Jordan 1990) and employs a somewhat convoluted build system based on autotools, characterized by static makefiles rather than dynamically generated ones. The establishment of a public repository empowers maintainers and contributors to collaboratively refactor the code towards consistent standards, improve bug tracking mechanisms, and facilitate the porting of the software to a wider array of computational platforms.

3. Key Aspects of Interest

3.1. Analysis of Validation and Reproducibility Needs

The enhancement of efficiency and reproducibility in bioinformatic algorithms necessitates a synergistic collaboration between biologists and computer scientists. For a project of the scale and complexity of BLAST+, the availability of a robust set of test files and a standardized validation procedure is essential. This is critical not only for ensuring algorithmic correctness but also for verifying the integrity of the compiled binary across diverse computational environments. This approach mirrors the bootstrapping procedure commonly employed in GCC builds, where the compiler is compiled multiple times to validate its own code and to optimize itself during each iteration (Stallman 2009). Given the extensive and continual use of BLAST+ in the scientific community (e.g., Friedman 2011), the application of a similarly rigorous validation methodology is highly warranted. A contribution of this study is the analysis of requirements for such a verification workflow, applicable not only to BLAST+ but also to other bioinformatics software, thereby highlighting inherent issues in building bioinformatics software and strategies for improvement.

3.2. Exploration of Advanced Performance Optimization for BLAST+

BLAST+ employs heuristic approaches to perform local sequence alignment, a fundamental task in bioinformatics. It is important to identify and analyze the performance-critical sections (bottlenecks) within any bioinformatics software codebase and an exploration of advanced optimization techniques applicable to these areas. One key aspect is the consideration of vectorization through the use of SIMD instruction sets and the exploitation of CPU pipeline concurrency. This strategy is analogous to enhancements previously made to the Smith-Waterman algorithm (Smith and Waterman 1981; Liu et al. 2013), leading to expectations of performance gains at the instruction level, thereby complementing existing multi-threading parallelization strategies already present in many software suites today.

4. Approaches and Methodologies

4.1. Examination of Reproducibility in Bioinformatics Software

The core issue of non-identical binary builds arises from the same source code due to variations in compilers or compiler versions was addressed through empirical testing and analysis. The investigation into reproducibility involves compiling and executing software under a defined test matrix. This matrix encompasses various C/C++ compilers (e.g., different GCC versions), multiple computer platforms (including x86-64 systems), and diverse BLAST+ parameter settings. A robust set of input sequence files, varying in attributes such as length, composition (amino acids, nucleic acids), and complexity, are utilized in the case of BLAST+'s functionalities. The critical E-value statistic, a measure of statistical significance in sequence alignments, serves as a primary focus for comparing outputs across these different conditions. A bioinformatic pipeline, comprising batch scripts and auxiliary software, is often employed to manage the testing workflow from input processing through to result comparison. Observed discrepancies in floating-point math outputs were documented to understand their origins and impact.

4.2. Analysis of Performance and Low-Level Optimization Techniques

Drawing inspiration from successes in computationally demanding fields such as video rendering (Abrash 1997), the use of hand-coded assembly or compiler intrinsics for FPU and SIMD units is discussed below. The GNU Gprof tool is a common tool for preliminary profiling to identify potential performance bottlenecks by measuring time spent in different functions during execution with representative datasets. Based on this, targeted optimization strategies can be considered. These included SIMD vectorization, where Intel’s SSE2/AVX instructions are applicable via compiler intrinsics or inline assembly to parallelize calculations. For computationally expensive functions, such as logarithmic calculations, the use of lookup tables or faster approximation algorithms is possible and applicable. Furthermore, built-in functions provided by compilers that offer access to machine-level optimizations are another avenue of interest. Manual or compiler-guided reordering of code lines within critical loops or blocks is also recommended as a means to improve instruction pipelining and cache utilization.

4.3. BLAST+ Source Code Management and Build System Analysis

An older version of the BLAST+ source code (e.g., version 2.6.0+ was originally available from ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/blast+/LATEST/) was the primary target of interest. Other legacy versions of BLAST+ (e.g., the 2.2.x branch) were also consulted for insights into software modularity and potential simplifications of their build systems. The automake-based build procedure, with its noted reliance on hard-coded paths within shell scripts and its use of static Makefiles, is analyzed. The more standard Cygwin build script serves as a valuable reference point in this analysis. The need to streamline the build process, potentially by refactoring Makefiles to be more dynamic and by reducing dependencies on hard-coded elements, with the ultimate aim of achieving a standard configure && make <target> workflow, is identified. Inspired by the PCRE library (a dependency of legacy BLAST+), which includes a robust test suite, the necessity for a similar comprehensive suite of input and output files for BLAST+ to validate its correctness across different versions and builds was established.

4.4. Testing Environment and Tools Utilized

Testing was conducted on common x86-64 platforms (running Linux and Windows). A range of compilers, including multiple versions of GCC and Microsoft Visual C++, were used or considered.

Initial testing experiences involved building BLAST+ version 2.6.0 (Camacho et al. 2009) with GCC compiler version 5.4.0 within 32-bit Cygwin for win32 development system (Cygwin 2017), targeting Windows. A notable issue encountered was the failure of the ReleaseMT (multithreading) build of BLAST+ to compile in Cygwin. This was attributed, based on GCC bug reports, to the use of the compiler option -Wall with GCC version 4.7 and higher, specifically related to a pragma line in the blast_kappa.cpp source file. The suggested workaround, using the parameter option -Wno-unknown-pragmas, confirmed this diagnosis. Consequently, BLAST+ was compiled without multithreading by modifying the configure script with without-openmp and without-mt, followed by executing make all_r to build all binaries. These options served to control for any potential deficits in Cygwin's handling of POSIX multithreading, which relies on a translation layer to standard win32 analogs, and also to control for problems that multithreading can introduce when compiling with optimization (Batty et al. 2015).

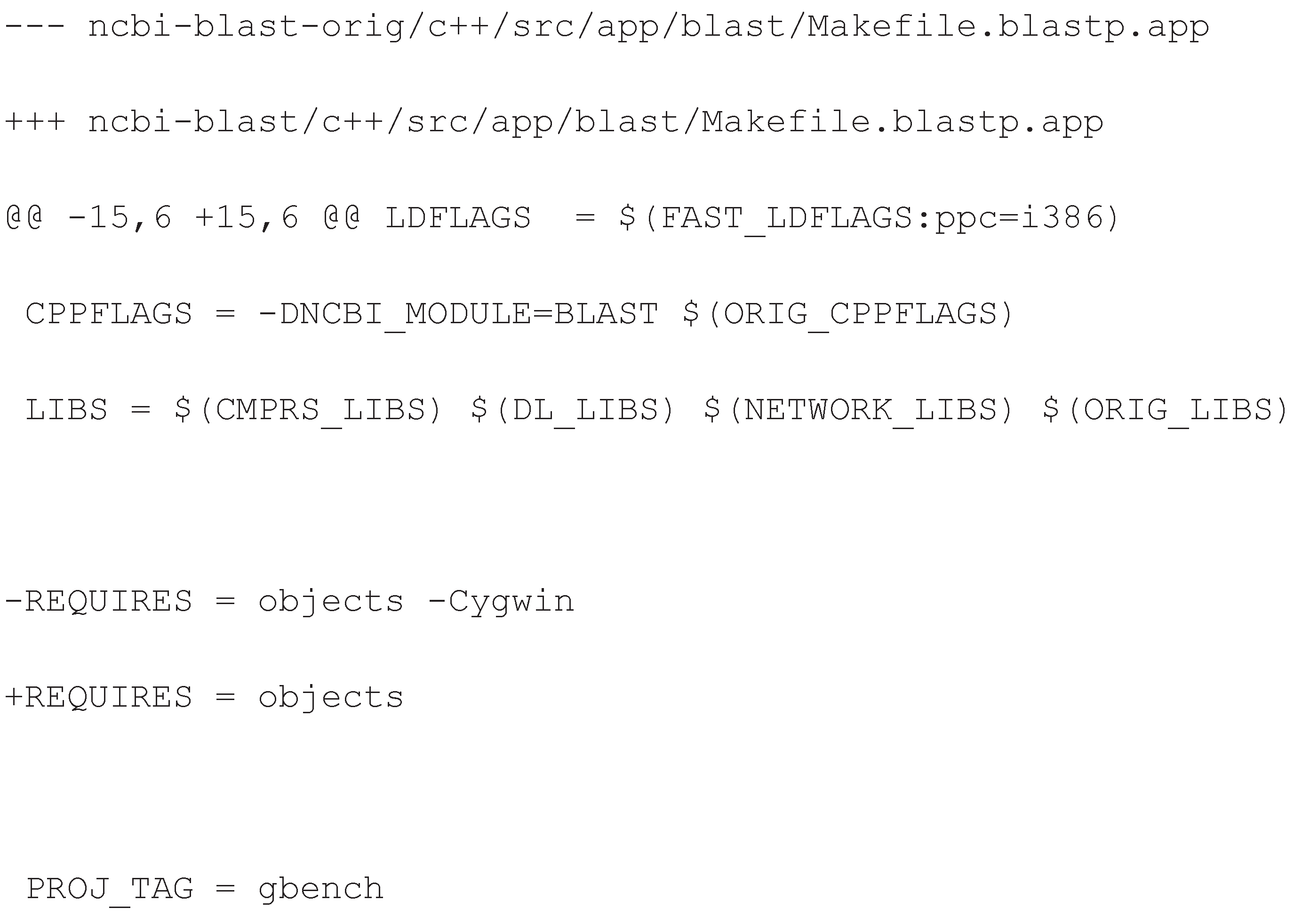

It was also observed that not all binaries within the BLAST+ package build successfully under Cygwin without modification. Removing a specific dependency, as illustrated by the patch file for blastp shown in

Figure 1, allowed these binaries to build and function as expected.

5. Analysis of Floating-Point Inconsistencies

5.1. Compiler Optimizations and IEEE 754 Adherence

Inconsistencies in floating-point arithmetic frequently arise from the manner in which compilers optimize code and their specific level of adherence to the IEEE 754 standard (IEEE 1985). For instance, on 32-bit x86 systems, Floating Point Units (FPUs) often internally utilize 80-bit precision, commonly referred to as "long double." When these high-precision values are moved to 64-bit CPU registers or memory locations (typically "double" precision), truncation can occur. Compiler optimizations can significantly alter the sequence and nature of these movements between registers and memory, leading to different levels of precision being retained at various stages of computation, and thus, to potentially different final results.

Furthermore, GCC intrinsic math functions may exhibit behaviors concerning rounding methods or the handling of non-normal values that differ from those of standard library functions (e.g., GNU libm) or other compilers like Microsoft Visual C++. These differences, particularly noticeable in legacy 32-bit builds, can manifest as slight variations in the mantissa of floating-point numbers. While seemingly minor, these can cascade in complex calculations, potentially leading to significant errors such as division-by-zero or severe performance degradation. Compiler flags can sometimes mitigate these issues. For example, the GCC float-store option forces floating-point variables to be stored in memory rather than being kept in FPU registers, which can ensure a consistent level of precision, albeit often at a performance cost. The excess-precision=standard option in GCC can also help align behavior, particularly for non-arithmetic functions, as noted by Monniaux (2008) in his discussion of discrepancies in the sin(p) calculation between Pentium 4 x87/Mathematica and GNU libc on x86_64. On modern x64 platforms, the use of advanced instruction sets, such as SSE2, for floating-point math is generally recommended for better adherence to the IEEE 754 standard. Alternatively, FPU precision can be explicitly lowered. However, it is important to note that compiler built-in functions might still override standard library behavior in certain cases. Monniaux (2008) also highlighted that even seemingly innocuous changes to source code, such as the addition of logging statements, can alter register allocation and instruction ordering by the compiler. This can lead to different floating-point outcomes despite the C/C++ source code being semantically identical. Such issues are further complicated in the context of multi-threaded applications (Batty et al. 2015).

5.2. Subnormal Numbers and Special Values

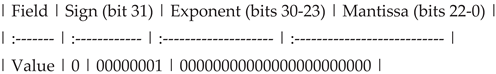

The IEEE 754 standard defines subnormal (or denormal) numbers to represent values that are smaller than the smallest "normal" floating-point number, effectively filling the numerical gap that would otherwise exist near zero. For a standard 32-bit single-precision floating-point number (comprising 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 23 mantissa bits, generally represented as ± m × 2

e), normal numbers have an exponent field ranging from 1 to 254. This biased exponent (typically with a bias of 127) yields effective exponents from -126 to +127. The smallest positive normal float is effectively 2 x 2

-126, where the binary exponent field is 00000001. The bit-field representation for such a value (approximately, assuming the stored mantissa is all zeros for simplicity, as normal numbers have an implicit leading '1' bit not stored in the mantissa field) is shown in

Table 1.

Subnormal numbers, in contrast, are characterized by an exponent field that is all zeros. For these numbers, the effective exponent is fixed at a special minimal value (e.g., -126 for single precision, but with an implicit leading '0' for the mantissa, rather than '1'). This convention allows for the representation of values down to 2 x 2-149 for single precision, although this comes at the cost of lost precision in the mantissa. Values smaller than the lowest subnormal number trigger an underflow event. The treatment of subnormal numbers can vary between compilers. For instance, legacy versions of the Intel C Compiler provides options that can affect precision in the case of subnormal values. While preserving precision might seem beneficial, if it implies using more than the standard 32 bits of information for a single-precision float, it can lead to results inconsistent with other C/C++ compilers. In another scenario, if an Intel C compiler is set for optimization levels such as O1 or higher and an SSE option is chosen, it may flush all, or nearly all, subnormal values to zero (a behavior controlled by FTZ/DAZ flags). This is a performance optimization, but it fundamentally changes the arithmetic behavior and serves as another example of how floating-point math can differ among compilers. These floating-point issues extend beyond the handling of subnormal numbers, but this example effectively illustrates the problems inherent in binary computation and the significant effects of compiler optimizations. The E-value calculation in BLAST+, being a critical statistic derived from floating-point operations, is identified as a key metric for observing such divergences.

5.3. Impact of 32-bit versus 64-bit Architectures on Floating-Point Stability

The distinction between 32-bit and 64-bit software builds is highly relevant to the study of floating-point errors. Standard 64-bit floating-point numbers (double-precision) offer significantly more precision and a wider dynamic range than their 32-bit counterparts (single-precision). A double-precision number typically uses 11 bits for the exponent and 52 bits for the mantissa, compared to 8 exponent bits and 23 mantissa bits for single-precision. This increased bit allocation inherently makes 64-bit computations less susceptible to the rapid accumulation of rounding errors, which can become pronounced in iterative algorithms or when subtracting nearly equal numbers.

The behavior of the x87 Floating-Point Unit (FPU), with its internal 80-bit extended-precision registers, further illustrates this point. When an 80-bit intermediate result is stored back into memory as a 32-bit single-precision float, a substantial amount of precision is lost. While storing to a 64-bit double-precision variable also involves precision loss from 80 bits, the loss is considerably less severe. Consequently, sequences of operations that might maintain acceptable accuracy in a 64-bit build could exhibit significant divergence or instability in a 32-bit build due to this more aggressive truncation.

Moreover, on modern 64-bit (x64) architectures, compilers often default to using SSE/AVX instruction sets for scalar floating-point arithmetic, even for double and float types. These instruction sets operate on 128-bit or wider registers and are generally designed for stricter adherence to IEEE 754 semantics regarding rounding and handling of special values, compared to the older x87 FPU instruction set which might still be a factor in some 32-bit compilation modes or for long double types. This can lead to more consistent and predictable floating-point behavior in 64-bit builds.

Although official BLAST+ releases are now commonly 64-bit, the above inclusion of 32-bit build testing (as exemplified by the initial Cygwin/w32 work) is valuable for an understanding of numerical precision in scientific software. The lower precision of 32-bit environments can act as a "stress test," potentially exposing classes of numerical instability or compiler-specific floating-point handling quirks more readily than in a 64-bit environment where higher precision might mask such issues. Understanding these behaviors in a more constrained precision environment provided crucial insights into the robustness of the algorithms and informed best practices for ensuring numerical stability across a wider range of platforms. For sensitive calculations like BLAST+'s E-value, the differences in precision between 32-bit and 64-bit builds, or even among different 32-bit compilation environments, are observable for detection of the more pronounced discrepancies in output, underscoring the importance of comparative analysis.

5.4. Legacy Context and Software Applicability

Within this report, certain software components and development environments were discussed in contexts that bear relevance to understanding legacy code or older computational paradigms. It is important to frame these discussions appropriately and to acknowledge the limitations when considering more recent software that was not part of this report.

BLAST+ 2.2.x Branch: The report mentions (

Section 4.3) that legacy versions of BLAST+, specifically the 2.2.x branch, were consulted. This was done in a historical context, primarily to gain insights into aspects like software modularity and the relative simplicity of older build systems compared to the contemporary BLAST+ (version 2.6.0+) codebase that was the main subject of the build and performance analysis. The characteristics and potential numerical behaviors of this specific older BLAST+ codebase (2.2.x) are rooted in the development practices and compiler/hardware environments prevalent at the time of its active development. As such, direct extrapolation of findings specific to the BLAST+ 2.2.x branch to very recent, unreviewed versions of BLAST+ or other modern bioinformatics tools should be approached with caution, as these newer tools would have evolved under different design principles and technological constraints.

32-bit Build Environments (e.g., Cygwin/w32 for BLAST+ 2.6.0): The use of a 32-bit Cygwin/w32 development system to build a contemporary version of BLAST+ (2.6.0), as detailed in

Section 4.4 and 5.3, also touches upon legacy considerations. While the BLAST+ version itself was current at the time of testing, compiling it for a 32-bit architecture was intended to simulate or explore behaviors pertinent to older computational environments where 32-bit processing was standard, or in specialized applications where it might still be used. This approach served as a valuable "stress test" for floating-point behavior due to the inherently lower precision of 32-bit floating-point types (

Section 5.3).

x87 Floating-Point Unit (FPU): The discussion of the x87 FPU (

Section 5.1 and 5.3) is primarily historical. The x87 FPU was the standard for floating-point operations on earlier x86 architectures, and its unique characteristics (e.g., 80-bit internal precision, specific instruction set) influenced floating-point results on those legacy systems. While an understanding of x87 behavior is crucial for analyzing older code or for specific 32-bit compilation modes where it might still be invoked (especially for long double types), modern 64-bit applications and compilers predominantly utilize SSE/AVX instruction sets for floating-point arithmetic. These newer instruction sets generally offer more consistent adherence to IEEE 754 standards.

Applicability to Recent, Unreviewed Code:

The analyses presented in this report, particularly those concerning specific build issues (e.g., the Cygwin patch for BLAST+ 2.6.0) and the observed floating-point behaviors, are grounded in the versions of software (BLAST+ 2.6.0, GCC 5.4.0, etc.) and the specific build environments detailed.

It is crucial to emphasize that these findings, especially those derived from 32-bit builds or considerations of older FPU behaviors, provide a historical and contextual understanding of potential numerical sensitivities. While the principles of floating-point arithmetic and compiler optimizations remain relevant, the specific manifestations of errors or inconsistencies can differ significantly in more recent software versions that were not reviewed as part of this study. Modern codebases, particularly those developed primarily for 64-bit architectures and compiled with the latest compilers, would likely benefit from different default settings, more mature SSE/AVX utilization by compilers, and potentially different algorithmic approaches to numerical stability. Therefore, the direct applicability of the specific observations made herein to unreviewed, recent code requires careful consideration and would necessitate a separate, dedicated investigation of that specific software.

6. Observed Outcomes and Discussion

The execution of this research yielded several significant observations and insights. A validated understanding of potential reproducibility issues in BLAST+ across different compilation environments was achieved, particularly highlighting the sensitivity of floating-point calculations. Preliminary performance profiling indicated specific areas within BLAST+ that could benefit from targeted optimization. The analysis of 32-bit versus 64-bit builds confirmed that lower-precision environments can exacerbate numerical instabilities, providing a clearer picture of algorithmic robustness. The investigation into the issue underscores the subtle but significant impact of compiler and hardware choices, including architectural bitness, on scientific software outputs. Furthermore, the analysis of the BLAST+ build system and comparison with open-source best practices highlights areas for continued modernization that benefits the wider bioinformatics community. These findings contribute to a further understanding of the challenges in maintaining reliable and efficient bioinformatics software.

7. Conclusion

This investigation addressed fundamental challenges in computational bioinformatics related to the reproducibility of scientific results and the performance of critical software tools. By focusing on legacy versions of BLAST+ as a case study, this work developed insights into testing floating-point arithmetic consistency and analyzing performance characteristics. The outcomes, including a nuanced understanding of 32-bit versus 64-bit floating-point behaviors, legacy software contexts, and build system complexities, contribute to the broader scientific community's efforts to improve the reliability and efficiency of essential bioinformatics infrastructure, thereby fostering more robust and cost-effective scientific discovery.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgement

Original content by the author, which was further adapted and enhanced by an AI Assistant, Gemini 2.5 Pro Preview, a model of artificial intelligence by Google (version 05/06/2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrash M (1997) Michael Abrash's Graphics Programming Black Book. Coriolis Group Books, Scottsdale, AZ, USA.

- Alpern B, Carter L, Gatlin KS (1995) Microparallelism and high performance protein matching, Proceedings of the 1995 ACM/IEEE Supercomputing Conference, San Diego, California.

- Appel AW, Ginsburg M (1997) Modern compiler implementation in C. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Batty M, Memarian K, Nienhuis K, Pichon-Pharabod J, Sewell P (2015) The Problem of Programming Language Concurrency Semantics. In: Vitek J. (eds) Programming Languages and Systems. ESOP 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9032.

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, et al. (2009) BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC bioinformatics 10.1: 421.

- Cygwin. (2017, ). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:26, March 15, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cygwin. 24 February.

- Friedman R (2011) Genomic organization of the glutathione S-transferase family in insects. Mol Phylogenet Evol 61: 924-32.

- IEEE standard for Binary floating-point arithmetic for microprocessor systems (1985).

- Jordan D (1990) Implementation benefits of C++ language mechanisms. Communications of the ACM 33: 61-4.

- Liu Y, Wirawan A, Schmidt B (2013) CUDASW++ 3.0: accelerating Smith-Waterman protein database search by coupling CPU and GPU SIMD instructions. BMC Bioinformatics 14: 117.

- Monniaux D (2008). The pitfalls of verifying floating-point computations. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. ACM 30: 12.

- NCBI Resource Coordinators (2016) Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Research 44: D7–D19.

- Numerical Computation Guide (2001) Sun Microsystems.

- Rau BR, and Fisher JA (1993) Instruction-level parallel processing: history, overview, and perspective. The Journal of Supercomputing 7.1-2 : 9-50.

- Smith TF, Waterman MS (1981) Identification of Common Molecular Subsequences. Journal of Molecular Biology 147: 195–7.

- Stallman R (2003) Free software foundation (FSF). In Encyclopedia of Computer Science (4th ed.), Anthony Ralston, Edwin D. Reilly, and David Hemmendinger (Eds.). John Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, UK 732-733.

- Stallman RM (2009) Using the Gnu Compiler Collection: A Gnu Manual for Gcc Version 4.3.3. CreateSpace, Paramount, CA.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).