1. Introduction

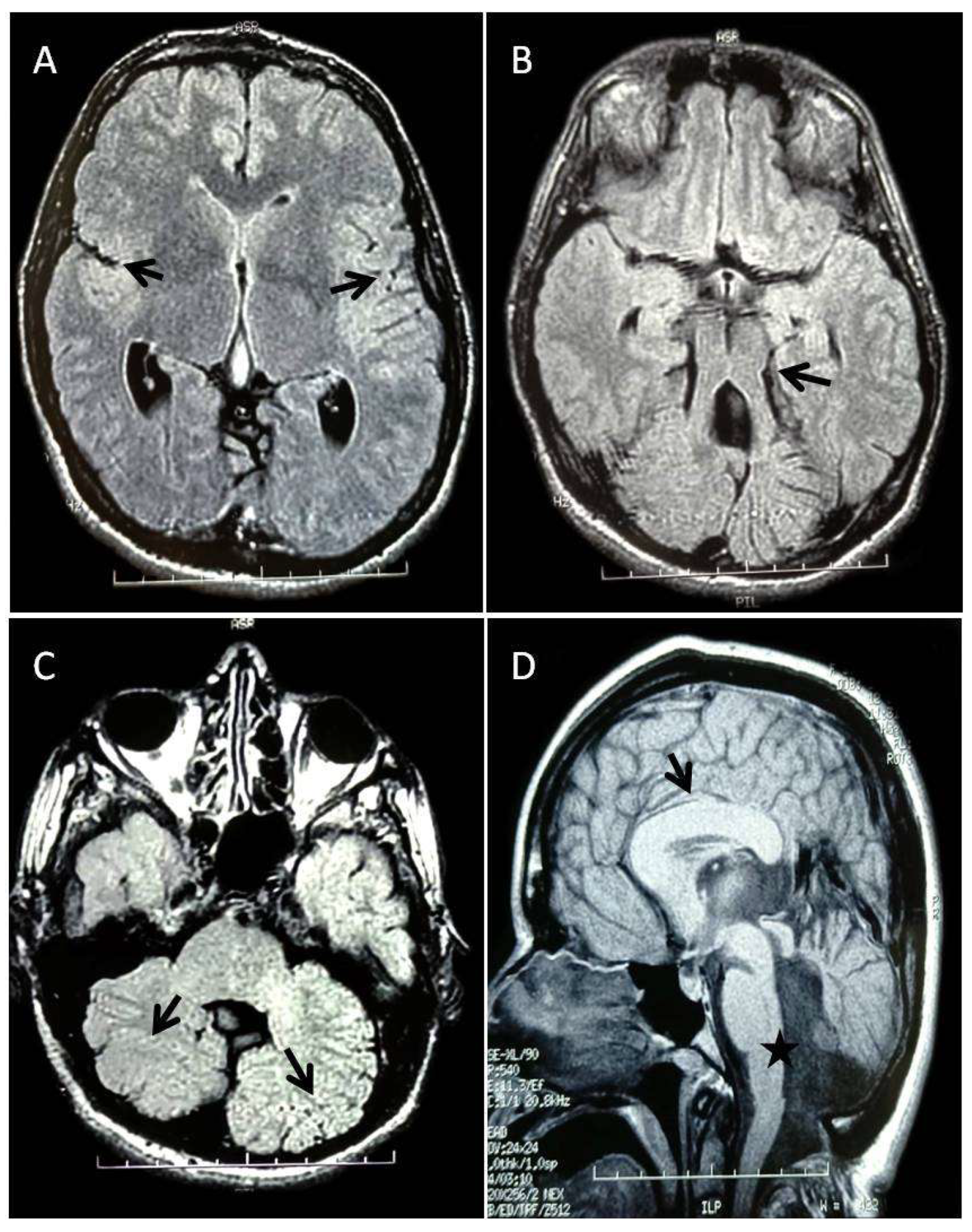

Joubert syndrome (JS, MIM 213300) is a rare clinical and genetic heterogeneous condition characterized by respiratory control disturbances, abnormal eye movements, ataxia, cognitive impairment, and the notable agenesis of the cerebellar vermis. The "molar tooth sign" (MTS), visible in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, serves as a diagnostic tool for JS and is characterized by thickened and horizontally oriented superior cerebellar peduncles, and deep interpeduncular fossa [

1,

2]. However, the MTS is present in many other disorders, the so called Joubert related disorders, such as Dekaban–Arima, COACH, Senior-Loken, and Orofaciodigital IV syndromes [

3]. A part from the MTS, additional brain anomalies have been described in JS individuals, such as occipital encephalocele, corpus callosum agenesis and dysgenesis, ventriculomegaly, neural migration defects, hypothalamic hamartoma and abnormal folial organisation of the cerebellar hemispheres [

4,

5].There is also almost always a delay in the acquisition of psychomotor milestones, and many patients also present with intellectual disability (ID) [

6]. However, cognitive abilities fall within a variable spectrum, ranging from a normal intelligence quotient to severe impairment of motor, language, and adaptive functioning. Cognitive deficits are often associated with behavioral and autism spectrum disorders, as well as sleep disturbances [

7]. In addition to these central nervous system (CNS) features, some individuals with JS may exhibit ocular issues (like chorioretinalcoloboma and progressive retinal dystrophy), kidney problems (nephronophthisis), liver abnormalities (such as ductal plate malformation and fibrosis), and/or skeletal issues (dystrophy and polydactyly) [

4]. JS shares genetic and phenotypic overlap with the more severe Meckel-Gruber Syndrome (MKS), often characterized by the co-occurrence of occipital encephalocele, cystic-dysplastic kidney disease, liver fibrosis, and perinatal lethality [

8]. JS is included in the disorders called ciliopathies, a group of genetic disorders characterized by defects in the structure or function of the cilia, which are microtubule-based organelles projecting from the surface of the most differentiated cells. These cilia play essential roles in various cellular processes, serving as environmental sensors that transduce sensory, chemical, or mechanical signals. Additionally, cilia are involved in crucial signalling pathways during development and homeostasis [

9]. Indeed, defects in the primary cilium can lead to a wide range of clinical phenotypes, and in fact ciliopathies can affect nearly every major body system, including brain, eyes, liver, kidneys, skeleton and limbs [

10].

Based on the clinical features observed in patients, JS is classified into 8 different several subtypes[

11,

12].

In the purely neurological or classical JS, the most frequently observed neurological symptoms include: irregular breathing rhythms, rapid respiration, obstructive sleep apnea, reduced muscle tone, unusual movements of the eyes and tongue, cognitive impairment, and problems with coordination such as ataxia. There is JSwith ocular involvement in which eye abnormalities commonly involve atypical retinal development, coloboma, involuntary eye movements (nystagmus), misalignment of the eyes (strabismus), and drooping eyelids (ptosis).There is JS with renal involvement that typically includes isolated nephronophthisis, a combination of nephronophthisis and cystic dysplasia, or presentations resembling autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.There are also forms of JS with both ocular and renal involvement referred to as Senior-Løken Syndrome.There are also forms of JS with hepatic involvement (also known as JS Type 7 / Meckel Syndrome Type 5 / COACH Syndrome) characterized bycongenital hepatic fibrosis and may present with portal hypertension, elevated liver enzymes, cholangitis, gastro-esophageal varices, and thrombocytopenia. A less frequently observed subtypeis JS with oral-facial-digital features, in which clinical signs may include craniofacial abnormalities such as cleft lip and/or palate, a midline groove of the tongue, hamartomas of the tongue or gums, hypertelorism, micrognathia, and extra digits (polydactyly), often postaxial and typically affecting both hands and feet. Another subtype of JS is characterized by abnormalities of the corpus callosum. Finally, JS with Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, characterized by skeletal dysplasia, including a narrow thoracic cage, short ribs, shortened tubular bones, a “trident-shaped” acetabular roof, rhizomelic limb shortening, cone-shaped epiphyses, brachydactyly, and often polydactyly.

JS shows predominantly an autosomal recessive inheritance, caused by biallelic variants affecting about 40 known genes. There are two exceptions to this pattern, when the associated mutation is located in the X-chromosomal

OFD1 gene [

13], or when heterozygous variants identified in the

ZNF423 gene lead to autosomal dominant inheritance [

14]. The prevalence of JS at birth is estimated at approximately 1.7:100,000 liveborns[

15].

Human tectonic

TCTN3 gene is 30.7-Kb long, mapped to chromosome 10q24.1, consists of 14 exons and encodes for TCTN3, a 607-aminoacid long membrane protein, that localizes to the primary cilium and is essential for the activation of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signalling pathway, and neural tube development [

16,

17]. Mutations in

TCTN3 gene can lead to the development of several diseases, including JS type 18 (OMIM 614815), Orofaciodigital syndrome IV (OFD type IV, OMIM 258860), and Meckel-Gruber Syndrome (MKS, OMIM 249000).

Previously, only 5 variants (three missense, one splicing and one frameshift) in the

TCTN3 gene have been identified as causative of JS [

4,

18,

19,

20,

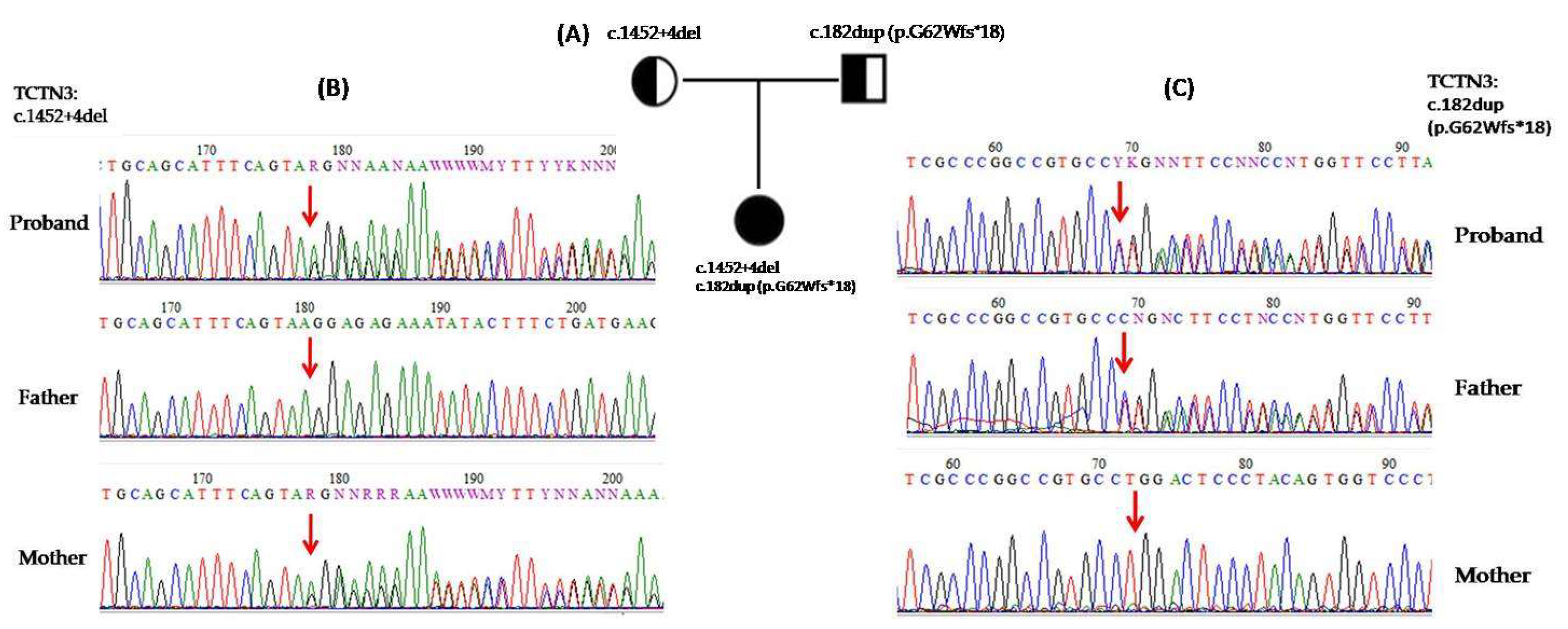

21]. In this report, we present a Caucasic proband with the MTS, thickened corpus callosum, ataxia, and ID. Molecular analysis through whole-exome sequencing (WES) revealed the heterozygous variants c.182dup (p.G62Wfs*18) and c.1452+4del in

TCTN3 gene. This case expands the clinical phenotype and genotype of TCTN3- associated diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Examination

The patient was presented to our institute for comprehensive diagnostic assessment to further investigate the underlying condition.

Comprehensive clinical and instrumental evaluations were performed, includingadaptive and cognitive profile, neurological examination, neuroradiological imaging (brain MRI), neurophysiological studies (EEG), and medical imaging (ultrasound examination of abdominal cavity).

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis

After informed consent, blood samples were collected from the patient and her parents, and DNA was extracted using standard protocols. To investigate the genetic cause of the disease, WES was performed in the patient. Nextera Flex for Enrichment Sample Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were sequenced in an Illumina NextSeq500 using a 2 × 150 paired-end reads protocol. The raw reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37/hgl9), and an integrative genomics viewer (IGV) was used to visualize the binary alignment map (BAM) files. The variants were identified through the GATK pipelineand further annotated with ANNOVAR (

http://wannovar.wglab.org). Variants classified as benign were excluded. The remaining variants were then assessed and categorized based on their potential clinical significance as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or variants of uncertain significance (VUS), according to the following criteria: (i) nonsense or frameshift variants in genes known to cause disease through haploinsufficiency or loss-of-function mechanisms; (ii) missense variants located in critical or functional domains; (iii) variants affecting canonical splice sites and (iv) variants classified or predicted as pathogenic or deleterious in ClinVar.In accordance with the pedigree and the phenotype, priority was given to rare variants [<1% in public databases, including 1000 Genomes project (

http://1000genomes.org),Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC,

http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD,

https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) containing 125,748 exome], that were fitting a recessive (e.g., compound heterozygous or homozygous) or a de novo model. Deleterious single nucleotide variants were predicted by Mutation Taster (

http://www.mutationtaster.org/, accessed on 1 October 2024) and SpliceRover (

http://bioit2.irc.ugent.be/rover/splicerover, accessed on 1 October 2024) prediction softwares.

2.3. Sanger Sequencing

PCR primers for exons 1 and 12 of the TCTN3 gene were designed by the software Vector NTI Advance 10.3.0 (Informax, Frederick,MD, USA) to verify the variants through Sanger sequencing.Reference sequences applied were TCTN3 gene, (NM_015631.6), TCTN3 protein (NP_056446.4). PCR reactions were carried out using the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μL reaction volumes containing 200 ng genomic DNA, 1X PCR reaction buffer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 μM of each primer and TaqDNA polymerase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were used. PCR cycling conditions used for the amplification included an initial denaturation step at 94˚C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94˚C, 45 s at 58˚C, 40 s at 72˚C and a final extension step at 72˚C for7 min.

Sequencing of PCRproducts was performed using BigDye Terminator reactions (ABI) in both forward and reverse orientations and an ABI 3130 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Patient sequence data were aligned for comparison with corresponding wild-type sequence.

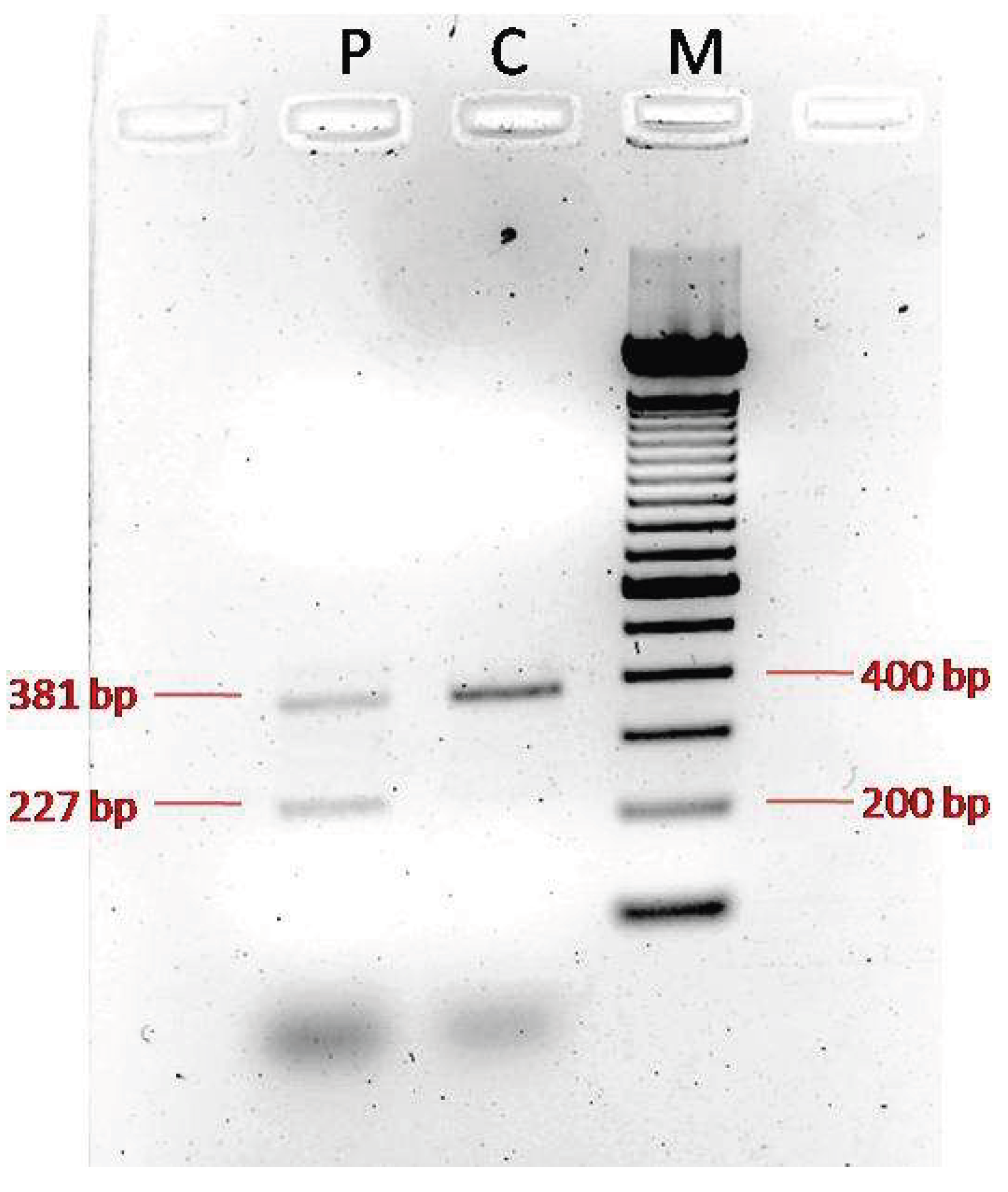

2.4. cDNA Analysis

RNA extraction from leucocytes of peripheral blood was performed using RNeasy Mini Handbook (Qiagen, Germantown, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA quality and quantity were checked by spectrophotometry. To avoid any genomic DNA contamination during PCR, a brief incubation of the samples at 42◦C with a specific Wipeout buffer (QuantiTect Reverse Transcription, Qiagen, Germantown, USA) was carried out. Retrotranscription of 500 ng of total RNA from sample was then performed in a final volume of 20 μL and generated cDNA for sequencing. PCR was performed on the cDNA with primers designed on exon 10 and exon 13 (TCTN3 forward primer 5’-CTCAATGACCCTCTTACAGAGCC-3; and TCTN3 reverse primer: 5’-TGGCACTGGTATAGGAATCGAA-3’). The resulting products were run on 1% agarose gel. All reactions were performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

4. Discussion

In this study, we report a Caucasian proband with the MTS, thickened corpus callosum, ataxia, and ID. Molecular analysis through WES revealed two heterozygous variants in the

TCTN3 gene. Homozygous variants in

TCTN3 have been associated with JS type 18. They have also been reported in the etiology of OFD type IV and MKS-like lethal phenotypes, where most variants were protein truncating and associated with a more severe phenotype. The latter includes brain anomalies, corpus callosum agenesis,vermian hypoplasia, absent olfactory system, cystic kidney, severe skeletal dysplasia, facial dysmorphisms with a lobulated tongue, four limbs polydactyly, ductal plate proliferation in the liver, and occipital encephalocele[

18,

22,

23].

Phenotypic variability due to variants in the

TCTN3 gene can be explained by the type of identified variant. It can be hypothesized that missense and splice site variants produce hypomorphic alleles and cause milder clinical features, such as JS due to the residual activity of the protein [

18,

20].Nonsense or frameshifting deletion variants may result in an absent or truncated protein, causing a more severe phenotype, as observed in OFD type IV and MKS-like lethal syndromes.

To date, 27 variants have been identified on HGMD Professional database (18 disease-causing variants and 9 variants of uncertain significance). Previously, only 5 mutations, three missense mutations, one splicing and one frameshift in the

TCTN3 gene have been identified as causative of JS [

4,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Of these variants, Bachmann-Gagescu (2015) [

4] reported the c.3G>A (p.M1I) homozygous pathogenic variant in one patient with coloboma. Thomas (2012) [

18] reported two siblings of 13 and 6 years with the c.940G>A (p.G314R) homozygous variant, showing agenesis of the cerebellar vermis and MTS. Furthemore this family exhibited additional features such, severe cyphoscoliosis in both affected siblings, camptodactyly and joint laxity in the older one, and a horseshoe kidney along with a ventricular septal defect in the younger. Ben-Salem (2014) [

19] reported an unrelated family from Middle East featuring JS with a digenic inheritance [(p.R479S) in

TCTN3 gene and (p.I641N) in AH1 gene]. Huppke (2015) [

20], instead, reported a patient with the c.853-1G>T homozygous variant of

TCTN3gene, causing an alteration of the acceptor splice site, with skipping of exon 7 and an in frame-deletion of 10 amino acids. The patient presented with agenesis of the cerebellar vermis and MTS, scoliosis, polydactyly, breathing abnormalities, ataxia, hypotonia, and ID. Finally, Huang (2022) [

21], reported a foetus with the c.1441dupT (p.C481Lfs*133) homozygous variant, diagnosed as JS by prenatal MRI and ultrasound, showing typical MTS, agenesis of the cerebellar vermis, polydactyly, malformation of cortical development, and posterior fossa dilation.

The variants identified in our patient, c.182dup (p.G62Wfs*18) and c.1452+4del, to the best of our knowledge, have not yet been reported in individuals with TCTN3-related conditions. The first variant creates a premature translational stop signal in the

TCTN3 gene: it is expected to result in the absent or disrupted protein product and/or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. For the second variant, since no functional studies had been performed, we tried to understand the impact of the c.1452+4del variant on the coding sequence of the transcript. Amplification of the proband’s cDNA and a normal control produced distinct patterns. As expected, the normal control cDNA amplification yielded a single clear 381 bp wild-type band. Instead, PCR of the cDNA derived from the proband showed two bands, a normal 381 bpone and an aberrant 227 bpother one, confirming the skipping of exon 12, eventually suggesting an abnormal protein product. Unfortunately, it was not possible to sequence the isolated bands, and consequently it was not possible validate the consequences on transcript level. These variants are in exons 1 and exon/intron border 12 respectively, that are part of the extracellular domain and are conserved in higher primates and rodents (

http://www.uniprot.org/blast/), indicating that these are not rare polymorphisms and most probably represent the variants underlying the phenotype observed in the patient.

The phenotype observed in our patient is characterized by severe ID, ataxic gait, hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis and MTS, thickened corpus callosum, abnormal cerebellar hemisphere, dystonic movements, strabismus and nystagmus. While agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) has been reported in 3% of patients with JS, [

4], thickened corpus callosum has never been reported. Moreover, thickened corpus callosum has never been identified in patients with pathogenic variants of the

TCTN3 gene.

Although ACC is a common brain malformation in people with ID and neurodevelopmental disorders, and has been linked to more than 300 genes, thickened corpus callosum has been associated with a few genes. Thickening of the corpus callosum has been reported with de novo postzygotic or germline variants in the

AKT3, PIK3R2, PIK3CA, HERC1, MTORgenes. These ones play a role in cell growth and proliferation, and are the molecular cause of Megalencephaly-Capillary Malformation Syndrome (MCAP), a rare genetic syndrome characterized by primary megalencephaly, cutaneous vascular malformations, prenatal overgrowth, connective tissue dysplasia, digital anomalies, and body asymmetry. Distinctive brain imaging features associated with MCAP include a thickened corpus callosum, polymicrogyria, lateral ventricles asymmetry, hydrocephalus, an enlarged cerebellum leading to crowding of the posterior fossa, and cerebellar tonsillar herniation or ectopia [

24,

25]. The phenotype observed in this syndrome is due to variants that affect the PI3K/Akt and mTOR signaling pathways. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is responsible for controlling important cellular responses like cell growth and proliferation, survival, migration, and metabolism [

26].

TCTN3 belongs to Tectonic family proteins, that include TCTN1, TCTN2, and TCTN3, a group of proteins existing in the cilium transition zone (TZ). TCTN proteins are considered to play a vital role in trafficking proteins into the cilia and are required for ciliary development and ciliogenesis. Furthermore, they play a key role in many signaling pathways including Shh, crucial for development and tissue homeostasis [

27]. The Shh pathway influences cellular fate by controlling the PI3K/Akt and mTOR signaling pathways. It could be hypothesized that variants of the

TCTN3 gene cause deregulation of the Shh pathway, and indirectly also of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. In fact, studies on mutated mice demonstrated that Tctn3

KO-/- result in abnormal expression of Shh signaling pathway-related genes and also cause abnormal neural tube patterning and neuronal apoptosis [

17].

This work confirms the data which suggest a broad clinical spectrum of

TCTN3 variants, ranging from mild to lethal phenotypes [

28]. In fact our patient presents a thickened corpus callosum, but on the contrary does not show renal and cardiac anomalies, thus confirming the phenotypic heterogeneity associated with variants of

TCTN3 gene.

In summary, we report an additional patient with clinical signs of JS with two novel variants in the TCTN3 gene and the presence of thickened corpus callosum, expanding the phenotype-genotype spectrum associated with TCTN3, highlighting the importance of considering a wide variability of clinical signs when a TCTN3-associated syndrome is suspected, given the crucial role of the TCTN3 gene in differentiation, migration and neuronal proliferation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.G. and C.S.; methodology, M.L.G.; software, M.L.G.; validation, M.L.G., M.G. and S.S.P.; formal analysis, M.L.G. and C.S.; investigation, M.L.G., M.G. and S.S.P.; resources,F.D.D.B., R.P. and C.S.; data curation, M.L.G., E.B. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.G. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, M.L.G., E.B., C.S. and C.R.; visualization, C.S. and C.R.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.R.; funding acquisition, C.R.