Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Physical performance tests

2.3.1. Anthropometric measurements

2.3.2. The 40m Speed Test

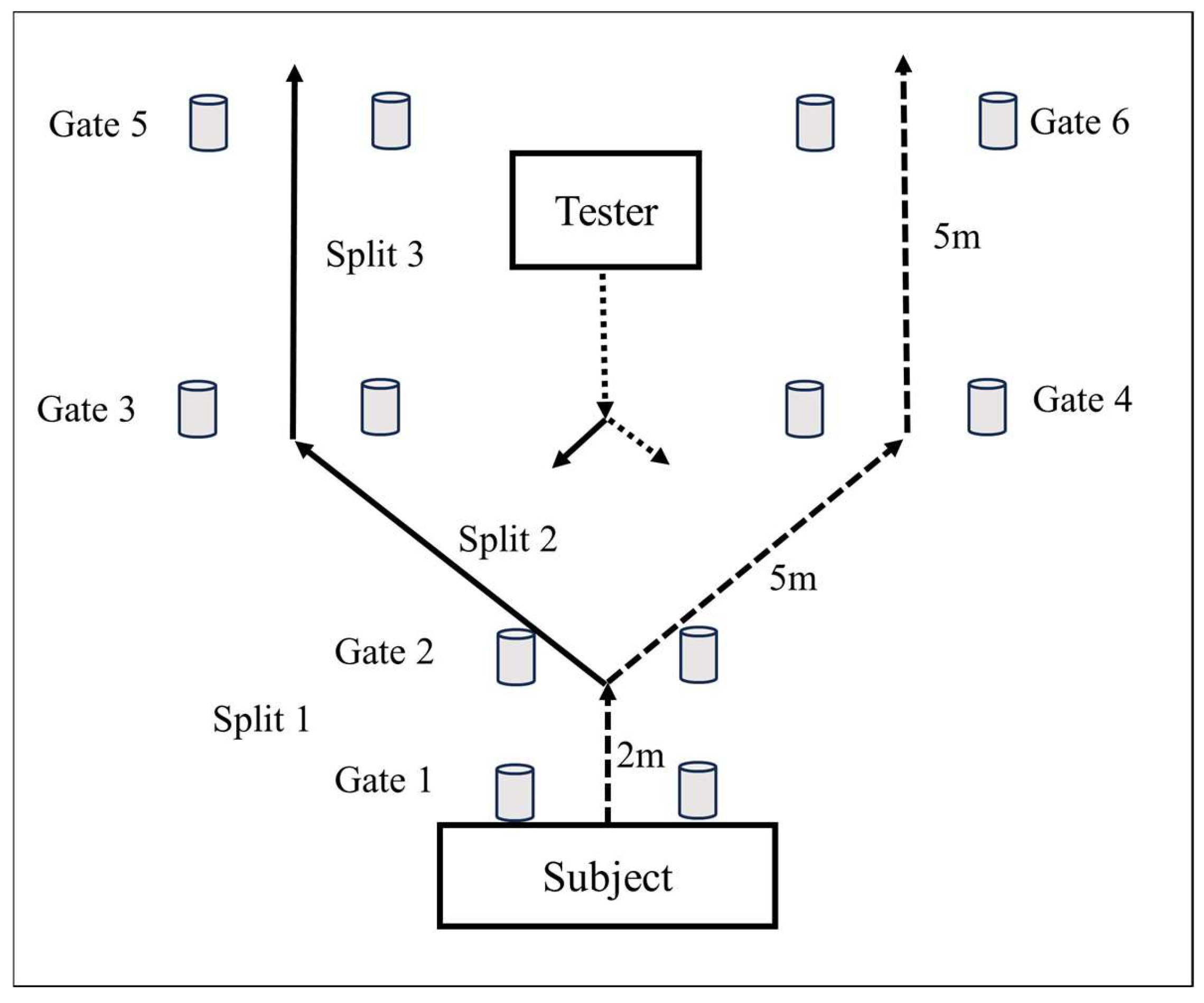

2.3.3. Reactive Agility Test (RAT)

- Step forward with the right foot and change direction to the left

- Step forward with the left foot and change direction to the right

2.3.4. Sports Vision Test (SVT)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

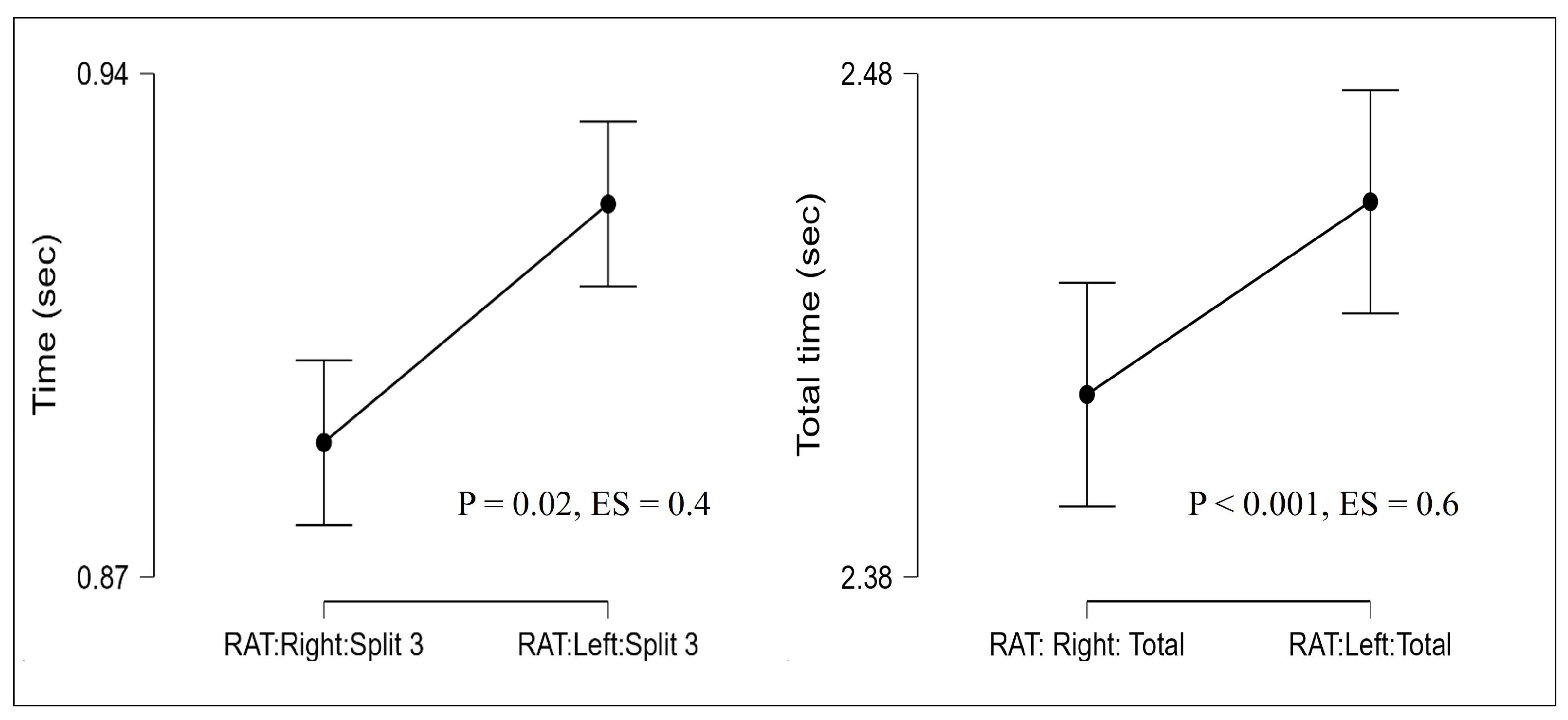

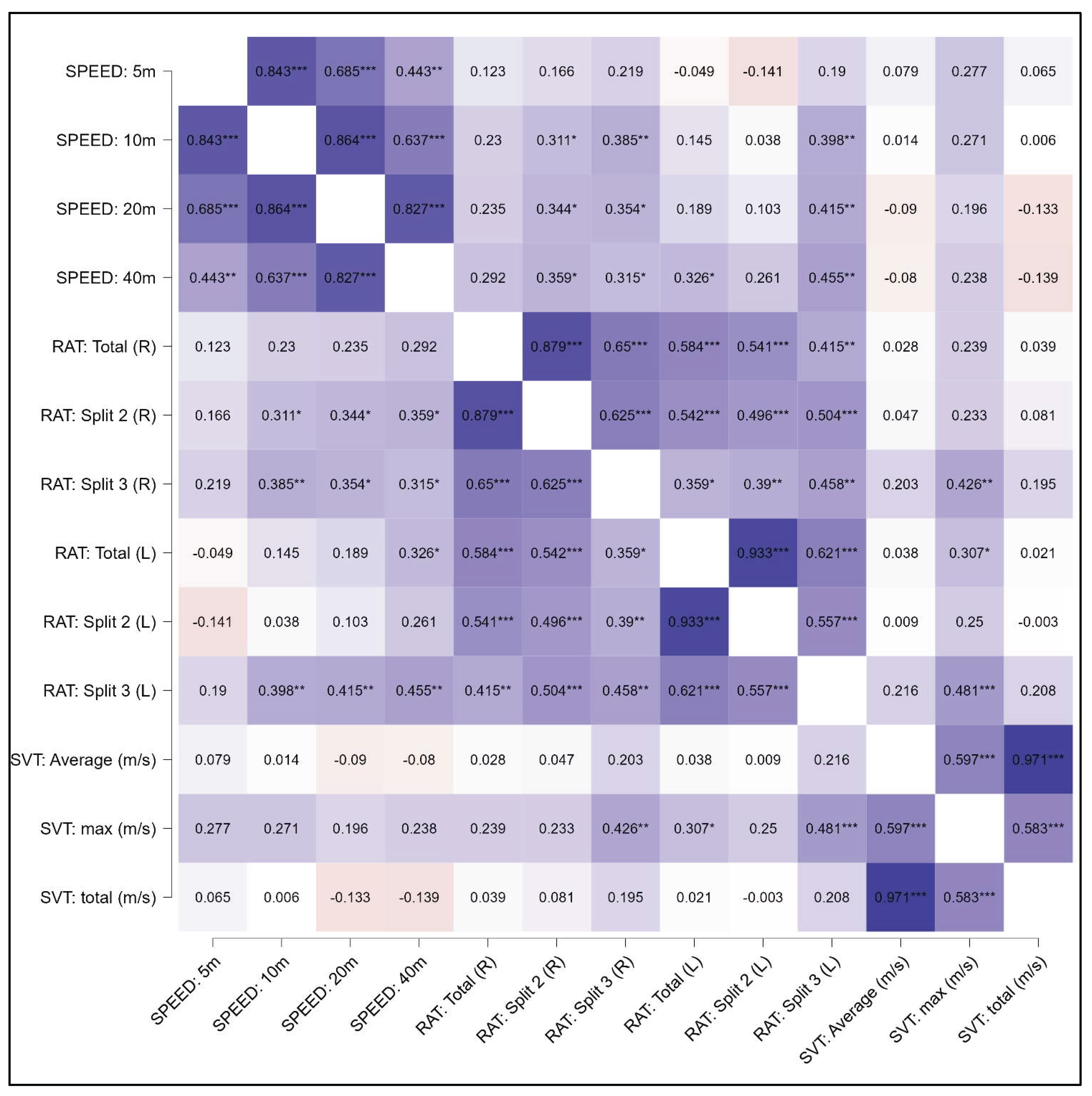

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RAT | Reactive Agility Test |

| SVT | Sports Vision Test |

| COD | Change of Direction |

| NWU | North-West University |

References

- Faude, O.; Koch, T.; Meyer, T. Straight Sprinting Is the Most Frequent Action in Goal Situations in Professional Football. J Sports Sci 2012, 30, 625–631, doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.665940. [CrossRef]

- Caldbeck, P.; Dos’Santos, T. How Do Soccer Players Sprint from a Tactical Context? Observations of an English Premier League Soccer Team. J Sports Sci 2022, 40, 2669–2680, doi:10.1080/02640414.2023.2183605. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, O.J.; Drust, B.; Ade, J.D.; Robinson, M.A. Change of Direction Frequency off the Ball: New Perspectives in Elite Youth Soccer. Science and Medicine in Football 2022, 6, 473–482, doi:10.1080/24733938.2021.1986635. [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Rayner, R.; Talpey, S. It’s Time to Change Direction on Agility Research: A Call to Action. Sports Medicine 2021, 7, doi:10.1186/s40798-021-00304-y. [CrossRef]

- Ade, J.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Bradley, P.S. High-Intensity Efforts in Elite Soccer Matches and Associated Movement Patterns, Technical Skills and Tactical Actions. Information for Position-Specific Training Drills. J Sports Sci 2016, 34, 2205–2214, doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1217343. [CrossRef]

- Casanova, F.; Oliveira, J.; Williams, M.; Garganta, J. Expertise and Perceptual-Cognitive Performance in Soccer: A Review. Revista portuguesa de Ciencias do Desporto 2009, 9, 115–122.

- Scharfen, H.E.; Memmert, D. The Relationship between Cognitive Functions and Sport-Specific Motor Skills in Elite Youth Soccer Players. Front Psychol 2019, 10, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00817. [CrossRef]

- Klatt, S.; Smeeton, N.J. Processing Visual Information in Elite Junior Soccer Players: Effects of Chronological Age and Training Experience on Visual Perception, Attention, and Decision Making. Eur J Sport Sci 2022, 22, 600–609, doi:10.1080/17461391.2021.1887366. [CrossRef]

- Young, W.B.; Dawson, B.; Henry, G.J. Agility and Change-of-Direction Speed Are Independent Skills: Implications for Training for Agility in Invasion Sports. Int J Sports Sci Coach 2015, 10, 159–169.

- Dos’santos, T.; Mcburnie, A.; Thomas, C.; Comfort, P.; Jones, P.; Corresponding, #; Dos, T.; Santos, ’ Biomechanical Comparison of Cutting Techniques: A Review and Practical Applications. Strength Cond J 2019, 4.

- Horníková, H.; Jeleň, M.; Zemková, E. Determinants of Reactive Agility in Tests with Different Demands on Sensory and Motor Components in Handball Players. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11, doi:10.3390/app11146531. [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, A.T., W.N., K.A.P., B.D.M., T.P.S. and D.V.J. Generic and Sport-Specific Reactive Agility Tests Assess Different Qualities in Court-Based Team Sport Athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2014, 3, 206–213.

- Trajković, N.; Sporiš, G.; Krističević, T.; Madić, D.M.; Bogataj, Š. The Importance of Reactive Agility Tests in Differentiating Adolescent Soccer Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, doi:10.3390/ijerph17113839. [CrossRef]

- Andrašić, S.; Gušić, M.; Stanković, M.; Mačak, D.; Bradić, A.; Sporiš, G.; Trajković, N. Speed, Change of Direction Speed and Reactive Agility in Adolescent Soccer Players: Age Related Differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, doi:10.3390/ijerph18115883. [CrossRef]

- Vaeyens, R.; Lenoir, M.; Williams, A.M.; Philippaerts, R.M. Mechanisms Underpinning Successful Decision Making in Skilled Youth Soccer Players: An Analysis of Visual Search Behaviors. J Mot Behav 2007, 39, 395–408, doi:10.3200/JMBR.39.5.395-408. [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Garganta, J.; Oliveira, J.; Casanova, F. The Contribution of Perceptual and Cognitive Skills in Anticipation Performance of Elite and Non-Elite Soccer Players. International Journal of Sports Science 2014, 2014, 143–151, doi:10.5923/j.sports.20140405.01. [CrossRef]

- Yepes, M.M.; Feliu, G.M.; Bishop, C.; Gonzalo-Skok, O. Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Agility Testing in Team Sports: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2022, 2035–2049.

- Hornikova, H.; Skala, F.; Zemkova, E. Sport-Specific Differences in Key Performance Factors among Handball, Basketball and Table Tennis Players. Int J Comput Sci Sport 2023, 22, 31–41, doi:10.2478/ijcss-2023-0003. [CrossRef]

- Gabbett, T.J.; Kelly, J.N.; Sheppard, J.M. Speed, Change of Direction Speed, and Reactive Agility of Rugby League Players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2008, 1, 174–181.

- Senel, O.; Eroglu, H. Correlation between Reaction Time and Speed in Elite Soccer Players. J Exerc Sci Fit 2006, 4, 126–130.

- Ricotti, L.; Rigosa, J.; Niosi, A.; Menciassi, A. Analysis of Balance, Rapidity, Force and Reaction Times of Soccer Players at Different Levels of Competition. PLoS One 2013, 8, 1–21, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077264. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, N. Prediction of Talent in Youth Soccer Players: Prospective Study over 4-6 Years. Football Science 2011, 8, 1–7.

- Kida, N.; Oda, S.; Matsumura, M. Intensive Baseball Practice Improves the Go/Nogo Reaction Time, but Not the Simple Reaction Time. Cognitive Brain Research 2005, 22, 257–264, doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.09.003. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, G.B. Visual Performance Evaluation. Sports vision: Vision care for the enhancement of sports performance 2007, 45–83.

- Ellison, P.H.; Sparks, S.A.; Murphy, P.N.; Carnegie, E.; Marchant, D.C. Determining Eye-Hand Coordination Using the Sport Vision Trainer: An Evaluation of Test-Retest Reliability. Research in Sports Medicine 2014, 22, 36–48, doi:10.1080/15438627.2013.852090. [CrossRef]

- Knöllner, A.; Memmert, D.; von Lehe, M.; Jungilligens, J.; Scharfen, H.E. Specific Relations of Visual Skills and Executive Functions in Elite Soccer Players. Front Psychol 2022, 13, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.960092. [CrossRef]

- Coh, M.; Vodiˇ, J.; Car, V.; Zvan, M.; Jožef, J.J.; Jožefšimenko, J.; Stodolka, J.; Rauter, S.; Ma´, K.; Ckala, M.; et al. Are Change-of-Direction Speed and Reactive Agility Independent Skills Even When Using the Same Movement Pattern? The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2018, 32, 1929–1936.

- Zemková, E. Differential Contribution of Reaction Time and Movement Velocity to the Agility Performance Reflects Sport-Specific Demands. Human Movement 2016, 17, 94–101, doi:10.1515/humo-2016-0013. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, S.; Ringhof, S.; Neumann, R.; Woll, A.; Rumpf, M.C. Validity and Reliability of Speed Tests Used in Soccer: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2019, 14, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220982. [CrossRef]

- Veale, J.; Pearce, A.; Carlson, J.; John, S. Reliability and Validity of a Reactive Agility Test for Australian Football. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2010, 5, 239–248.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates, 2013;

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New Effect Size Rules of Thumb. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 2009, 8, 597–599, doi:10.22237/jmasm/1257035100. [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.M. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate through Multivariate Techniques: From Bivariate through Multivariate Techniques.; 2nd ed.; Sage, 2013;

- Bergmann, F.; Gray, R.; Wachsmuth, S.; Höner, O. Perceptual-Motor and Perceptual-Cognitive Skill Acquisition in Soccer: A Systematic Review on the Influence of Practice Design and Coaching Behavior. Front Psychol 2021, 12.

- Scharfen, H.E.; Memmert, D. Cognitive Training in Elite Soccer Players: Evidence of Narrow, but Not Broad Transfer to Visual and Executive Function. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 2021, 51, 135–145, doi:10.1007/s12662-020-00699-y. [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, L.G.; Erickson, G. Sports Vision Training: A Review of the State-of-the-Art in Digital Training Techniques. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2018, 11, 160–189.

- Mann, D.T.Y.; Williams, A.M.; Ward, P.; Janelle, C.M. Perceptual-Cognitive Expertise in Sport: A Meta-Analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2007, 29, 457–461.

- Clark, J.F.; Ellis, J.K.; Bench, J.; Khoury, J.; Graman, P. High-Performance Vision Training Improves Batting Statistics for University of Cincinnati Baseball Players. PLoS One 2012, 7, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029109. [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.W.; Kramer, A.F.; Basak, C.; Prakash, R.S.; Roberts, B. Are Expert Athletes “expert” in the Cognitive Laboratory? A Meta-Analytic Review of Cognition and Sport Expertise. Appl Cogn Psychol 2010, 24, 812–826, doi:10.1002/acp.1588. [CrossRef]

- Zemková, E.; Hamar, D. Association of Speed of Decision Making and Change of Direction Speed With The Agility Performance. Functional Neurology, Rehabilitation, and Ergonomics • 2017, 7, 10–15.

- Buscemi, A.; Mondelli, F.; Biagini, I.; Gueli, S.; D’Agostino, A.; Coco, M. Role of Sport Vision in Performance: Systematic Review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2024, 9.

- Presta, V.; Vitale, C.; Ambrosini, L.; Gobbi, G. Stereopsis in Sports: Visual Skills and Visuomotor Integration Models in Professional and Non-Professional Athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18.

- Sheppard, J.M.; Young, W.B.; Doyle, T.L.A.; Sheppard, T.A.; Newton, R.U. An Evaluation of a New Test of Reactive Agility and Its Relationship to Sprint Speed and Change of Direction Speed. J Sci Med Sport 2006, 9, 342–349, doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.019. [CrossRef]

- Salmoni, A.W., S.R.A. and W.C.B. Knowledge of Results and Motor Learning: A Review and Critical Reappraisal. Psychol Bull 1984, 3, 355.

- Matlák, J., F.M., K.V., S.G., P.E., K.B., K.B., L.G. and R.L. Relationship between Cognitive Functions and Agility Performance in Elite Young Male Soccer Players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2022, 10–1519.

- Stølen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisløff, U. Physiology of Soccer An Update; 2005; Vol. 35;.

| Physical test | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Speed: 5m (s) | 1,05 ± 0.05 |

| Speed: 10m (s) | 1,79 ± 0.06 |

| Speed 20m (s) | 3,08 ± 0.1 |

| Speed: 40m (s) | 5,51 ± 0.2 |

| RAT: Right: Total (s) | 2,42 ± 0.11 |

| RAT: Right: Split 2 (s) | 1,01 ± 0.07 |

| RAT: Right: Split 3 (s) | 0,89 ± 0.21 |

| RAT: Left: Total (s) | 2,45 ± 0.13 |

| RAT: Left: Split 2 (s) | 1,02 ± 0.08 |

| RAT: Left: Split 3 (s) | 0,92 ± 0.2 |

| SVT: minimum (ms-1) | 0,28 ± 0.1 |

| SVT: maximum (ms-1) | 0,52 ± 0.2 |

| SVT: average (ms-1) | 0,36 ± 0.12 |

| SVT: total (ms-1) | 7,11 ± 2.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).