1. Introduction

Claustrophobia, defined as an irrational fear of confined spaces, can significantly impact sufferers’ daily lives. Individuals with claustrophobia often avoid situations such as using elevators, public transportation, or even being in small rooms. These constraints, can limit their activities and reduce their quality of life [

1,

2]. One of the most reliable and widely used tools for assessing claustrophobia is the Claustrophobia Questionnaire (CLQ). Originally developed by Radomsky et al. (2001), the CLQ has been validated in various cultural and linguistic populations, demonstrating its reliability and validity across different contexts [

3,

4,

5]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the robust psychometric properties of the CLQ. For example, the French and English versions of the CLQ have shown strong reliability and validity in both clinical and research settings [

4]. Similarly, the Dutch version of the CLQ has been validated and confirmed to possess good psychometric properties [

5]. Additionally, the CLQ has been successfully adapted for use in other languages and populations, such as the Spanish and the Swedish, indicating its applicability across different cultural contexts [

6,

7].

Claustrophobia is a common challenge for individuals undergoing imaging examinations, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In these latter scenarios, patients with claustrophobia may experience severe anxiety or panic due to the enclosed space, restricted movement, and loud noise of the MRI machine [

8,

9]. These factors intensify discomfort and can disrupt the imaging process [

8]. Research shows that about 10% of patients undergoing MRI report claustrophobic reactions, and 2%-5% may even stop the procedure due to extreme anxiety [

10].

Recent studies emphasize the need for early identification of claustrophobia before MRI scans. This allows for interventions such as medication or alternative imaging methods to be implemented [

11]. Reliable assessment tools, like the Claustrophobia Questionnaire (CLQ), are vital for early recognition of claustrophobia and personalized management before and during the examination.

A recent study [

12] highlights the necessity of adapting the CLQ for use in Greek-speaking populations, confirming the tool’s validity and reliability. This research underscores the need for a reliable instrument to assess claustrophobia in Greek patients, particularly before procedures that could trigger anxiety, ensuring appropriate preparation and support.

Reliable and valid assessment of claustrophobia is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of the disorder. Despite the extensive international use of CLQ, there is a lack of data on the application and psychometric evaluation of the CLQ within the Greek population. Validating a questionnaire in a specific cultural context is crucial, as cultural and linguistic differences can influence the manifestation and reporting of symptoms. For instance, perceptions and attitudes towards confined spaces may vary significantly across cultures, affecting the validity of the questionnaire’s results. Additionally, validating of the CLQ in Greek will contribute to cross-cultural psychology, providing data that will facilitate comparisons between different cultural populations [

13]. Standardizing the CLQ in a Greek sample will improve the understanding and management of claustrophobia in Greece, providing a culturally sensitive tool that aligns with international research standards. This research will also offer valuable insights into the nature and extent of claustrophobia in the Greek population, enhancing therapeutic interventions and health policies [

14]. Furthermore, it will aid in developing more comprehensive and inclusive psychological assessments that consider cultural nuances and variations in symptomatology [

15].

Therefore, considering that the validation of the CLQ in local-speaking population is essential for the reliable and valid assessment of claustrophobia, the study aims to validate the CLQ in Greek-speaking population, providing a valuable tool for clinicians and researchers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We included 314 Greek-speaking individuals of both sexes, aged between 18-70 years old. Inclusion criteria were: Greek as the primary language; at least 3 years of education; age >17. Exclusion criteria were: major psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression; schizophrenia); dementia syndrome; alcohol or drug abuse. Additionally, we conducted a pilot study (n=50) to examine the test-retest reliability of the Greek CLQ. We created an online version of the study questionnaire through Google Forms, and we posted it on Facebook to inform users of the purpose and the design of the study. Thus, we obtained a convenience sample. All questions on the online study questionnaire were mandatory but individuals had the opportunity to terminate their participation at anytime. Since all the questions were mandatory, we did not have missing data. Confirmatory factor analysis requires at least 200 participants [

16], and, thus, our sample covered this requirement.

Our study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [

17]. The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens granted approval for our study protocol (724/25-10-2023). All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Procedure

We applied the forward-backward translation method to translate the English CLQ into Greek. Additionally, we followed the suggested procedure for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires [

18]. In short, two independent scholars translated the English CLQ into Greek and reached a consensus. Then, two other scholars translated the Greek CLQ back into English and reached a consensus. We compared the final English CLQ with the original English CLQ and confirmed its linguistic accuracy. Afterward, we examined the face validity of the Greek CLQ by performing cognitive interviews [

19] with ten individuals. We did not identify linguistic issues, and no changes were necessary during this step. Participants confirmed the clarity of the 26 items. We obtained permission from CLQ developers to translate and validate the tool in Greek. Data collection occurred in January 2024.

2.3. Measures

The Claustrophobia Questionnaire (CLQ [3]): The CLQ contains 26 items measuring levels of claustrophobia on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all anxious) to 4 (extremely anxious) [

3]. The CLQ comprises two factors: suffocation (14 items) and restriction (12 items). Total scores range from 0 to 104, with higher scores indicating higher levels of claustrophobia.

The Fear Survey Schedule-III (FSS-III [20]): The FSS-III measures specific fears, including three items that assess claustrophobic fear (FSS-III-CL): “I am afraid of crowds,” “I am afraid of being in an elevator,” and “I am afraid of enclosed spaces.” Responses are on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all afraid) to 4 (extremely afraid). The FSS-III-CL score ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating higher levels of claustrophobic fear. We used the validated Greek version of the FSS-III-CL [

21], which showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.803 in our study.

The NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI-NL [22]): This inventory assesses five personality traits, but we used the 12 items measuring neuroticism. Responses are on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of neuroticism. We used the validated Greek NEO-FFI-NL-N [

23], which had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.824 in our study.

The Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI [24]): The STAI includes 40 items measuring state (STAI-S) and trait (STAI-T) anxiety on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (almost always). Scores range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher anxiety levels. We used the validated Greek STAI, which showed Cronbach’s alpha of 0.934 for trait anxiety and 0.854 for state anxiety in our study [

25].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages), and continuous variables as means (standard deviations, SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the distribution of continuous variables and parametric statistics were applied following data normal distribution.

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the previously reported factor structure of the CLQ in Greek. We employed CFA to examine the construct validity of the CLQ. Since CLQ data are on an ordinal scale we used the weighted least squares method [

26]. Developers of the CFA suggest a two-factor model of the questionnaire: 14 items load onto a suffocation factor and 12 items load onto a restriction factor [

3]. We calculated chi-square/degree of freedom (x

2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), normed fit index (NFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). We adopted criteria for fit from previous studies: x2/df < 5, RMSEA < 0.10, and for all other indices > 0.90 [

27,

28]. Moreover, we calculated standardized regression weights between the 26 items of the CLQ and the two factors. CFA was conducted using the AMOS version 21 (Amos Development Corporation, 2018).

If more than 85% of participants achieved the lowest (1) or highest possible score (5) on the 26 items of the CLQ, respectively, we considered ceiling or floor effects [

29].

To further evaluate the discriminant validity of the CLQ, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) score and the Composite Reliability (CR) score. Acceptable values for the AVE score are higher than 0.50 [

30], while for the CR score are higher than 0.70 [

30,

31].

We examined the convergent validity of the Greek CLQ by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the CLQ scores and scores on FSS-III-CL, NEO-FFI-NL-N, STAI-S (state anxiety), and STAI-T (trait anxiety). We examined the divergent validity of the Greek CLQ using the Fisher r-to-z transformation. In particular, we compared the correlations of the Greek CLQ with other measures of claustrophobia (FSS-III-CL), questionnaires assessing neuroticism (NEO-FFI-NL-N), state anxiety (STAI-S), and trait anxiety (STAI-T). Since the FSS-III-CL measures claustrophobic fear and the CLQ measures levels of claustrophobia we expected higher correlation between CLQ and FSS-III-CL than correlation between CLQ and STAI.

To assess the reliability of the CLQ in the test-retest study, we employed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). We utilized a two-way mixed-effects model with absolute agreement, calculating ICCs, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values. Excellent reliability is indicated by ICC values exceeding 0.90 [

32].

To evaluate the internal reliability of the Greek CLQ, we computed Cronbach’s alpha for all 26 items, as well as Cronbach’s alpha with individual items removed. A Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.70 was deemed acceptable [

33]. Additionally, we determined corrected item-total correlations to gauge the Greek CLQ’s reliability, with values ≥0.30 considered acceptable [

34].

The statistical threshold was set at p-value < 0.05. All previously reported analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

Participants were 314 Greek-speaking individuals aged 18-70 years old. The mean age was 39.3 years (SD 12.1), while the median age was 38 years. In our sample, 69.1% (n=217) were females and 30.9% (n=97) were males. Demographic characteristics of our sample are shown in

Table 1.

Levels of claustrophobia were higher among females than males. In particular, mean total CLQ score was 38.4 (SD; 23.2) and 24.4 (SD; 18.3) for females and males (p-value<0.001), respectively. Moreover, mean score on suffocation factor was 14.8 (SD; 12.1) for females and 8.6 (SD; 9.5) for males (p-value<0.001). Mean score on restriction factor was 23.5 (SD; 13.2) for females and 15.6 (SD; 10.9) for males (p-value<0.001). There were no significant correlations between age and CLQ score (r=0.041, p-value=0.468), score on suffocation factor (r=0.039, p-value=0.494), and score on restriction factor (r=0.037, p-value=0.516).

3.2. Factor Structure

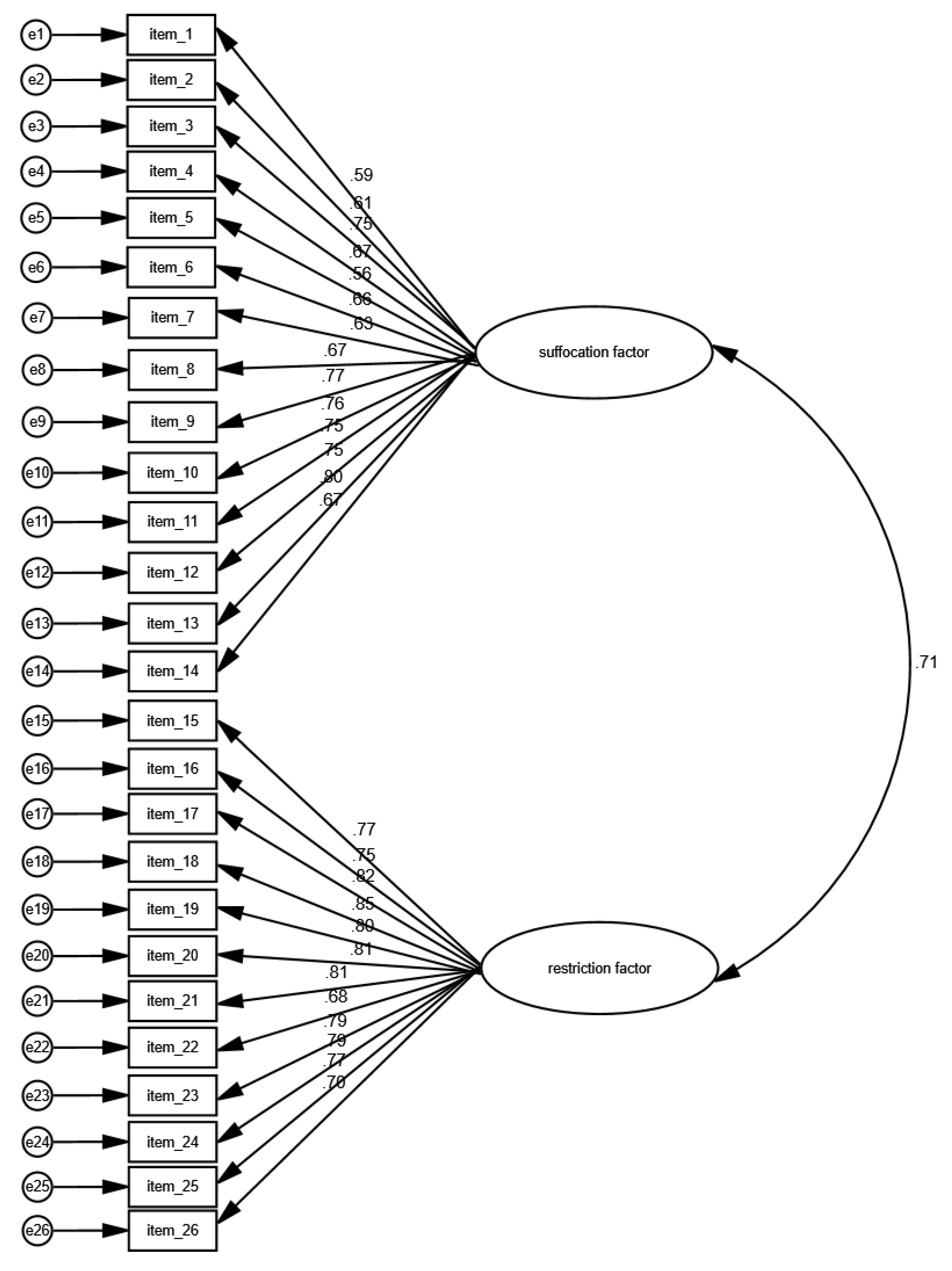

Figure 1 shows the results from the CFA for the Greek CLQ. All indices showed good fit of the two-factor model. In particular, x

2/df was 1.199, RMSEA was 0.025, GFI was 0.936, AGFI was 0.904, TLI was 0.989, IFI was 0.992, NFI was 0.955, and CFI was 0.992. Moreover, correlation between the suffocation factor and the restriction factor was 0.71 (p < 0.001). Standardized regression weights between the 26 items of the CLQ and the two factors ranged from 0.559 to 0.854. Thus, the Greek CLQ confirmed the two-factor model structure of the original version of the questionnaire.

We did not find ceiling or floor effects on our data. To further evaluate the discriminant validity of the CLQ, we calculated the AVE score and the CR score for the two factors. AVE for the suffocation factor was 0.573, while for the restriction factor was 0.543, which are both higher than acceptable value of 0.50. Moreover, the CR score for the suffocation factor was 0.949, while for the restriction factor was 0.954, which are higher than acceptable value of 0.70. Additionally, the AVE for each construct is greater than the squared correlations with other constructs. Thus, the discriminant validity of the Greek version of the CLQ was acceptable.

3.3. Convergent Validity

Table 2 illustrates the correlations between the Greek CLQ and other questionnaires used in the study. A strong correlation was observed between the Greek CLQ and the FSS-III-CL (r = 0.744, p < 0.001), while a moderate correlation was found with the NEO-FFI-NL-N (r = 0.394, p < 0.001), the STAI-S (r = 0.302, p < 0.001), and the STAI-T (r = 0.383, p < 0.001). A similar pattern of correlations was identified when CLQ suffocation and restriction factors were considered separately.

3.4. Divergent Validity

The Greek CLQ correlated higher with the FSS-III-CL than with the NEO-FFI-NL-N [z = 6.77, p < 0.001], the STAI-S [z = 8.08, p < 0.001], and the STAI-T [z = 6.93, p < 0.001]. The suffocation factor of the CLQ correlated higher with the FSS-III-CL than with the NEO-FFI-NL-N [z = 7.05, p < 0.001], the STAI-S [z = 7.35, p < 0.001], and the STAI-T [z = 6.99, p < 0.001]. The restriction factor of the CLQ correlated higher with the FSS-III-CL than with the NEO-FFI-NL-N [z = 4.60, p < 0.001], the STAI-S [z = 6.53, p < 0.001], and the STAI-T [z = 4.93, p < 0.001].

3.5. Reliability Analysis

ICC for the CLQ score in test-retest study was 0.986 (95% CI = 0.975 to 0.992, p < 0.001). Additionally, ICC for the suffocation factor was 0.964 (95% CI = 0.936 to 0.979, p < 0.001), and the restriction factor was 0.986 (95% CI = 0.975 to 0.992, p < 0.001). Therefore, the reliability of the CLQ was excellent.

Cronbach’s alpha for the CLQ score, the suffocation factor, and the restriction factor were 0.956, 0.926, and 0.949, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for the CLQ score did not increase after elimination of each single item. Corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.494 to 0.770 (

Table 3). Thus, the internal consistency reliability of the CLQ was excellent.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to validate the Greek version of the CLQ by assessing its psychometric properties in a Greek sample. The findings suggest that the Greek version of the CLQ demonstrates robust psychometric properties, aligning with prior validations conducted in different languages and cultural settings. [

3,

5,

7,

22,

35].

A claustrophobia questionnaire could be an effective tool in clinical practice, helping to assess the severity of the condition and identify specific triggers. By using such questionnaires, clinicians can develop personalized treatment plans that address the patient’s unique needs [

36]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or gradual exposure therapy are commonly used approaches that aim to reduce anxiety by slowly desensitizing the individual to their fears, helping them regain control over their life [

3,

37].

Construct validity of the Greek CLQ was evaluated using CFA. An analysis of the questionnaire confirmed its two-factor structure (suffocation and restriction). The fit indices (χ2/df < 5, RMSEA < 0.10, GFI, AGFI, TLI, IFI, NFI, and CFI > 0.90) were within acceptable ranges, indicating that the Greek version maintains the structural integrity of the original CLQ [

3]. The significant correlation between the two factors further supports the original bidimensional framework. Convergent validity was established by examining the Pearson correlation coefficients between the CLQ and other established measures of anxiety and personality traits, including the Fear Survey Schedule-III (FSS-III-CL), the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI-NL), and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The CLQ showed strong correlations with the FSS-III-CL and moderate correlations with the NEO-FFI-NL and STAI, confirming its excellent convergent validity [

4,

21,

22]. Divergent validity was assessed using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation, comparing the correlation strengths between the CLQ and FSS-III-CL with those between the CLQ and NEO-FFI-NL and STAI. The stronger correlations with the FSS-III-CL compared to the other measures confirmed the CLQ’s specificity in measuring claustrophobia distinctly from general anxiety and personality traits [

20,

23]. The reliability of the Greek CLQ was assessed through internal consistency and test-retest reliability measures. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.956, with the suffocation factor at 0.926 and the restriction factor at 0.949, indicating excellent internal consistency. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the overall scale was 0.986, demonstrating high test-retest reliability and stability over time [

32]. These results align with those from previous CLQ validations in different languages, further supporting its reliability across diverse cultural contexts [

5,

7,

22,

23,

24].

A claustrophobia assessment tool can be extremely useful for patients scheduled for an MRI scan, as it helps identify those who are more likely to experience high anxiety during the procedure. When these patients are identified ahead of time, healthcare professionals can take steps like administering sedative medications or opting for an open MRI scanner to make the experience more manageable [

38,

39,

40]. This not only makes the process easier for the patient, but also helps avoid cancellations or delays, ultimately leading to better overall patient care [

41,

42].

Beyond its clinical value, such a tool holds significant importance in research settings. Being able to measure claustrophobia levels allows researchers to select appropriate participants for functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies focusing on claustrophobia, gaining insights into brain regions such as the amygdala and insular cortex, which are involved in fear and spatial awareness [

43,

44]. Understanding these neural mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted interventions.

Furthermore, an assessment tool allows researchers to measure the effectiveness of different therapeutic interventions, such as CBT, relaxation techniques, or virtual reality exposure. Using fMRI to track changes in brain activity, researchers may evaluate how these interventions impact claustrophobic responses. Studies have found that patients who practice breathing control or focus on positive thoughts during MRI scans show reduced activity in brain areas linked to anxiety [

45,

46]. Thus these tools provide a vital baseline for comparing brain activity before and after various coping strategies [

47].

While this study achieves promising results, it has a few limitations that should be recognized. Firstly, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to response biases. Secondly, cultural differences may influence the interpretation of claustrophobic experiences and responses, and while the CLQ has been validated in various contexts, subtle cultural nuances may still affect the outcomes. Moreover, we did not examine the criterion validity of the CLQ. Last but not least, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes assessing changes in CLQ sensitivity over time, which longitudinal studies could do.

As a result of the validation of the Greek version of the CLQ for Greek-speaking populations, a reliable and valid tool for the assessment of claustrophobia is now available. This instrument can be used effectively in both clinical settings and research studies to diagnose and evaluate claustrophobia, thereby improving treatment outcomes and contributing to the field of cross-cultural psychology. The strong psychometric properties of the Greek CLQ support its use in comparative studies across different cultural groups, enhancing our understanding of how claustrophobia manifests and is experienced globally [

15,

17].

5. Conclusion

A number of excellent psychometric properties have been demonstrated by the Greek version of the CLQ, including construct validity, convergent and divergent validity, and reliability. These findings are consistent with previous validations of the CLQ in other languages and cultural contexts. Consequently, the Greek CLQ is a valuable tool for clinicians and researchers, aiding in the accurate assessment and treatment of claustrophobia. Future research should explore the application of the CLQ in diverse populations to further validate its use and enhance its applicability across various cultural settings.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Approval Number: 724/25-10-2023). The study complies with all relevant institutional, national, and international regulations regarding research involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. All participants provided written informed consent for the publication of anonymized data presented in the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request. For requesting data, please write to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this work. A completed and signed Declaration of Competing Interests form has been submitted separately as required by the journal.

References

- Vadakkan C, Siddiqui W. Claustrophobia. [Updated 2023 Feb 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542327/.

- Björkman-Burtscher, I.M. Claustrophobia—empowering the patient. Eur Radiol 31, 4481–4482 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Radomsky AS, Rachman S, Thordarson DS, McIsaac HK, Teachman BA. The Claustrophobia Questionnaire. J Anxiety Disord. 2001 Jul-Aug;15(4):287-97. PMID: 11474815. [CrossRef]

- Radomsky, A. S., Ouimet, A. J., Ashbaugh, A. R., Paradis, M. R., Lavoie, S. L., & O’Connor, K. P. (2006). Psychometric properties of the French and English versions of the Claustrophobia Questionnaire (CLQ). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(6), 818–828. [CrossRef]

- Van Diest I, Smits D, Decremer D, Maes L, Claes L. The Dutch Claustrophobia Questionnaire: psychometric properties and predictive validity. J Anxiety Disord. 2010 Oct;24(7):715-22. PMID: 20558033. [CrossRef]

- Valls MM, Palacios AG, Botella C. Psychometric properties of the Claustrophobia Questionnaire in Spanish population. Psichothema. 2003;15(4):673-678.

- Carlbring P, Söderberg M. Swedish translation of the CLQ. Uppsala University; 2001.

- Hudson DM, Heales C, Meertens R. Review of claustrophobia incidence in MRI: A service evaluation of current rates across a multi-centre service. Radiography (Lond). 2022 Aug;28(3):780-787. PMID: 35279401. [CrossRef]

- D.M. Hudson, C. Heales, S.J. Vine, Radiographer Perspectives on current occurrence and management of claustrophobia in MRI, Radiography, Volume 28, Issue 1, 2022, Pages 154-161, ISSN 1078-8174. [CrossRef]

- Dantendorfer K, Wimberger D, Katschnig H, Imhoff H. Claustrophobia in MRI scanners. Lancet. 1991 Sep 21;338(8769):761-2. PMID: 1679897. [CrossRef]

- Rentmeester C, Bake M, Dall C. Claustrophobia-Related Anxiety During MR Imaging Examinations. Radiol Technol. 2022 Sep;94(1):53-57. PMID: 36347608.

- Skalidis I, Arangalage D, Kachrimanidis I, Antiochos P, Tsioufis K, Fournier S, Skalidis E, Olivotto I, Maurizi N. Metaverse-based cardiac magnetic resonance imaging simulation application for overcoming claustrophobia: a preliminary feasibility trial. Future Cardiol. 2024 Mar 11;20(4):191-195. PMID: 38699964; PMCID: PMC11285275. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006 Dec;8(6):458-63. PMID: 17162825. [CrossRef]

- Karaivazoglou K, Konstantopoulou G, Kalogeropoulou M, Iliou T, Vorvolakos T, Assimakopoulos K, Gourzis P, Alexopoulos P. Psychological distress in the Greek general population during the first COVID-19 lockdown. BJPsych Open. 2021 Feb 24;7(2):e59. PMID: 33622422; PMCID: PMC7925978. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Kwon JH. Moderation effect of emotion regulation on the relationship between social anxiety, drinking motives and alcohol related problems among university students. BMC Public Health. 2020 May 18;20(1):709. PMID: 32423398; PMCID: PMC7236287. [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling; 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, 2016.

- General Assembly of the World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Coll Dent. 2014 Summer;81(3):14-8. PMID: 25951678.

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011 Apr;17(2):268-74. PMID: 20874835. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, K. Cognitive Interviewing Methodologies. Clin Nurs Res 2021, 30, 375–379. [CrossRef]

- WOLPE J, LANG PJ. A FEAR SURVEY SCHEDULE FOR USE IN BEHAVIOUR THERAPY. Behav Res Ther. 1964 May;2:27-30. PMID: 14170305. [CrossRef]

- Mellon, R. A Greek-Language Inventory of Fears: Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure of Self-Reports of Fears on the Hellenic Fear Survey Schedule. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 22, 123–140 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou G, Kokkinos CM, Spanoudis G. Searching for the “Big Five” in a Greek context: the NEO-FFI under the microscope. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36(8):1841-1854. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1983.

- Fountoulakis KN, Papadopoulou M, Kleanthous S, Papadopoulou A, Bizeli V, Nimatoudis I, Iacovides A, Kaprinis GS. Reliability and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y: preliminary data. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jan 31;5:2. PMID: 16448554; PMCID: PMC1373628. [CrossRef]

- Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016 Sep;48(3):936-49. PMID: 26174714. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner H, Homburg C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 1996;13(2):139–161. [CrossRef]

- Brown T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015., Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424-453. [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B.; Arifin, W.N.; Hadie, S.N.H. ABC of Questionnaire Development and Validation for Survey Research. EIMJ 2021, 13, 97–108. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research: 18 39–50.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3): 411–423.

- Koo TK, Li MY. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J Chiropr Med. 2016 Jun;15(2):155-63. Epub 2016 Mar 31. Erratum in: J Chiropr Med. 2017 Dec;16(4):346. PMID: 27330520; PMCID: PMC4913118. [CrossRef]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572. [CrossRef]

- De Vaus D. Surveys in Social Research. 5th ed. London: Routledge; 2004.

- Moradi, D., Eyvazpour, R., Hosseini, S.A.T., Donyatalab, Y., Rahimi, F. (2022). Fuzzy Cluster Analysis of Claustrophobia Questionnaire Data in Iranian Male and Female Educated Populations. In: Kahraman, C., Cebi, S., Cevik Onar, S., Oztaysi, B., Tolga, A.C., Sari, I.U. (eds) Intelligent and Fuzzy Techniques for Emerging Conditions and Digital Transformation. INFUS 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 307. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Björkman-Burtscher, I.M. Claustrophobia—empowering the patient. Eur Radiol 31, 4481–4482 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kampmann IL, Emmelkamp PM, Morina N. Meta-analysis of technology-assisted interventions for social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2016 Aug;42:71-84. PMID: 27376634. [CrossRef]

- Klaming R, Annese J. Functional anatomy of essential tremor: lessons from neuroimaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014 Aug;35(8):1450-7. PMID: 23620075; PMCID: PMC7964453. [CrossRef]

- Enders J, Zimmermann E, Rief M, Martus P, Klingebiel R, Asbach P, Klessen C, Diederichs G, Bengner T, Teichgräber U, Hamm B, Dewey M. Reduction of claustrophobia during magnetic resonance imaging: methods and design of the “CLAUSTRO” randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Imaging. 2011 Feb 10;11:4. PMID: 21310075; PMCID: PMC3045881. [CrossRef]

- Iwan, E., Yang, J., Enders, J. et al. Patient preferences for development in MRI scanner design: a survey of claustrophobic patients in a randomized study. Eur Radiol 31, 1325–1335 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Al-Shemmari AF, Herbland A, Akudjedu TN, Lawal O. Radiographer’s confidence in managing patients with claustrophobia during magnetic resonance imaging. Radiography (Lond). 2022 Feb;28(1):148-153. PMID: 34598898. [CrossRef]

- Dantendorfer K, Wimberger D, Katschnig H, Imhoff H. Claustrophobia in MRI scanners. Lancet. 1991 Sep 21;338(8769):761-2. PMID: 1679897. [CrossRef]

- Harris LM, Robinson J, Menzies RG. Evidence for fear of restriction and fear of suffocation as components of claustrophobia. Behav Res Ther. 1999 Feb;37(2):155-9. PMID: 9990746. [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller, G., Blinowska, K.J., Kaminski, M. et al. Processing of fMRI-related anxiety and bi-directional information flow between prefrontal cortex and brain stem. Sci Rep 11, 22348 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Silva AC, Lee JH, Aoki I, Koretsky AP. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI): methodological and practical considerations. NMR Biomed. 2004 Dec;17(8):532-43. PMID: 15617052. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Kariri, Hadi Dhafer et al., From theory to practice: Revealing the real-world impact of cognitive behavioral therapy in psychological disorders through a dynamic bibliometric and survey study, Heliyon, Volume 10, Issue 18, e37763. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez JC, McCrank E. Anxiety-related reactions associated with magnetic resonance imaging examinations. JAMA. 1993 Aug 11;270(6):745-7. PMID: 8336378. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).