1. Introduction

Cancer treatment has involved the selection of antitumor drugs according to the cancer type in each organ. The effectiveness of antitumor drugs against various cancer types has been examined, and antitumor drugs have been prescribed according to the treatment guidelines for each cancer type [

1]. However, the effectiveness of antitumor drugs, as defined by clinical practice guidelines, is not always known. Cancer cells are heterogeneous, and the unique characteristics of each individual cancer cell strongly affect the efficacy of the prescribed antitumor agent [

2]. The "Precision Medicine Initiative" was announced in 2015 in the USA, which is developing into a new cancer treatment known as cancer genome medicine, which is not limited by the cancer type in each tissue [

3,

4].

FoundationOne® CDx Cancer Genomic Profile (FMI, Cambridge, MA, USA) and OncoGuide™ NCC oncopanel (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan) were approved in Japan, by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as cancer gene panel tests for solid tumors and have been covered by insurance in June 2019. Cancer gene panel testing has been initiated in Japan in clinical practice as a genomic cancer treatment. The genomic DNA extracted from sections of surgically removed tissues (solid tumors) are fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin, then used for cancer gene panel testing. However, the genomic DNA in tissues fragments after long-term storage; therefore, tissue sections stored for more than three years cannot be used for cancer gene panel testing. Therefore, these cancer gene panel tests cannot not performed on patients who underwent surgical treatment more than three years ago, who were transferred from another hospital, or from whom tissue sections could not be obtained.

Many clinical studies have analyzed various parameters of the cell-free DNA in liquid biopsies (human blood samples), such as variations in bases, copy numbers, and structure; DNA fragmentation; and DNA methylation. Methods have been developed to detect and monitor the onset and progression of cancer based on various cell-free DNA parameters [

5]. FoundationOne® CDx liquid (FMI) and Guardant360 CDx (Guardant Health, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) have been approved by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as cancer gene panel tests for use with human blood samples. Nucleotide mutations and copy number changes were detected in the cell-free DNA obtained from human blood samples. Therefore, cancer gene panel testing using human blood samples is the method of choice when tissue sections removed by surgical treatment are not available or have been stored for more than three years.

Our medical staff performed cancer gene panel testing from 2019 to March 2025 to identify new treatment strategies for approximately 5,500 cases of progressive and metastatic malignant tumors. The gene mutations and increased copy numbers detected through cancer gene panel testing were compared with the data from databases such as ClinVar (National Center for Biotechnology Information) [

6], OncoKB (an FDA-recognized human genetic variant database) [

7], and Catalogua Of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) [

8] to determine their involvement in the onset or progression of malignant tumors. However, KRAS gene mutations may be silent mutations or splicing donor sites, and such gene mutations do not affect the onset or progression of malignant tumors [

9]. Therefore, our medical staff re-examined whether the gene mutations detected using cancer gene panel testing were silent mutations or splice donor sites.

SDHB G642T was diagnosed as a variant of unknown significance (VUS) through cancer gene panel testing for a 41-year-old male patient with paraganglioma. However, this mutation was later discovered to cause a shift in the splicing site, preventing SDHB from being translated from the correct mRNA. In addition, BRCA2 631 3A>T was identified as a VUS from the results of cancer gene panel testing of a 47-year-old patient with right breast cancer. However, this mutation created a splicing site that prevented the correct BRCA2 mRNA from being produced for BRCA2. As such, the medical information displayed in databases such as ClinVar is not always accurate; therefore, genome databases must also be used to examine the effects of gene mutations. Furthermore, the information in these databases may not be applicable to the onset or progression of malignant tumors in Asian populations as the data were obtained from Western patients,. Therefore, medical information should be organized by race when creating a database.

2. Patients and Methods

Cancer Gene Panel Profiling

This multicenter, retrospective, observational study included patients who received cancer genome treatment at various cancer medical facilities in Kyoto, Japan. This clinical study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Central Ethics Review Board of the National Hospital Organization Headquarters, Meguro, Tokyo, Japan (approval number: NHO R4-04; approval date: November 18, 2020) and the Kyoto University School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan (approval number: M237; approval date: August 24, 2022). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cancer genome medicine was applied using cancer gene panel testing, which was approved by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare on June 3, 2019. Cancer gene panel testing involved the use of the OncoGuideTM NCC Oncopanel gene mutation analysis set (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan) and FoundationOne CDx cancer genome test (Foundation One CDx, Foundation One CDx, Foundation Medicine, Inc., Cambridge MA, USA).

The mutation information of 324 genes was analyzed using the FoundationOne CDx cancer genome profile, using the genomic DNA of the tumor tissue samples (including cytology samples) obtained from the patients with solid cancer and in the cell-free DNA of the plasma separated from the whole-blood samples of the patients with solid cancer. The mutation information of 114 genes was analyzed using the OncoGuideTM NCC Oncopanel with the genomic DNA of the tumor tissue specimens (including cytology specimens) obtained from the patients with solid cancers. In addition, the program was used to analyze the mutation information of 114 genes in the cell-free DNA of the plasma separated from the whole-blood samples of patients with solid cancer. We determined whether the genomic mutations in the tumor tissue samples were germline mutations.

A total of 5504 novel treatments were investigated using cancer genome panel testing (FoundationOne® CDx test: n = 4135; OncoGuideTM NCC Oncopanel test, Riken Genesis, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan, n = 1369) at Japanese national universities from December 2019 to May 2025.

3. Results

The results obtained from the cancer gene panel tests performed by our medical staff are mainly based on the medical information in ClinVar. However, some of the medical information in ClinVar does not reflect specific pathogenic variants in Asian, including Japanese, populations [

10]. Therefore, the detection of genetic cancers in a family may be missed. Therefore, medical staff must reverify the medical information in ClinVar.

A silent mutation is a base mutation that changes the DNA sequence of a gene but does not result in a change in the amino acid sequence of a protein [

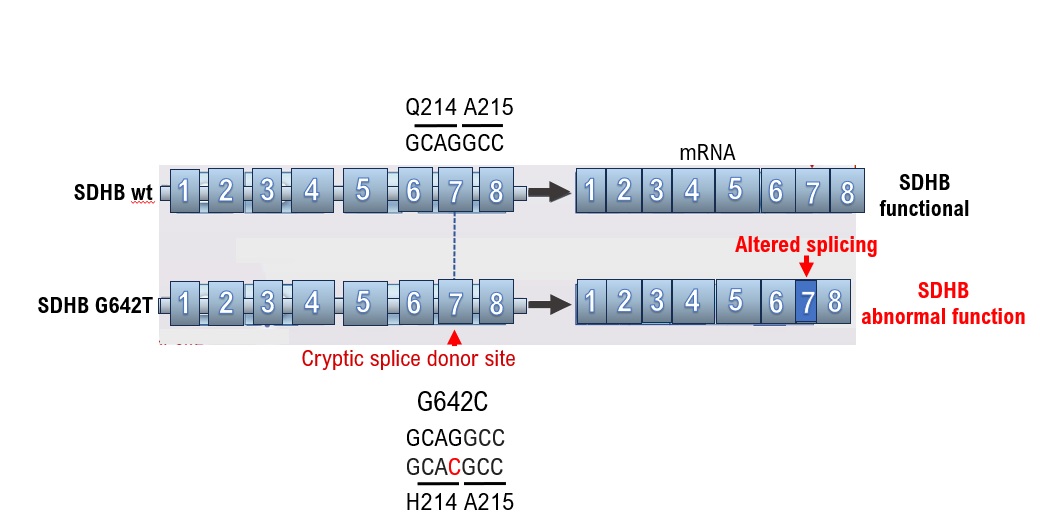

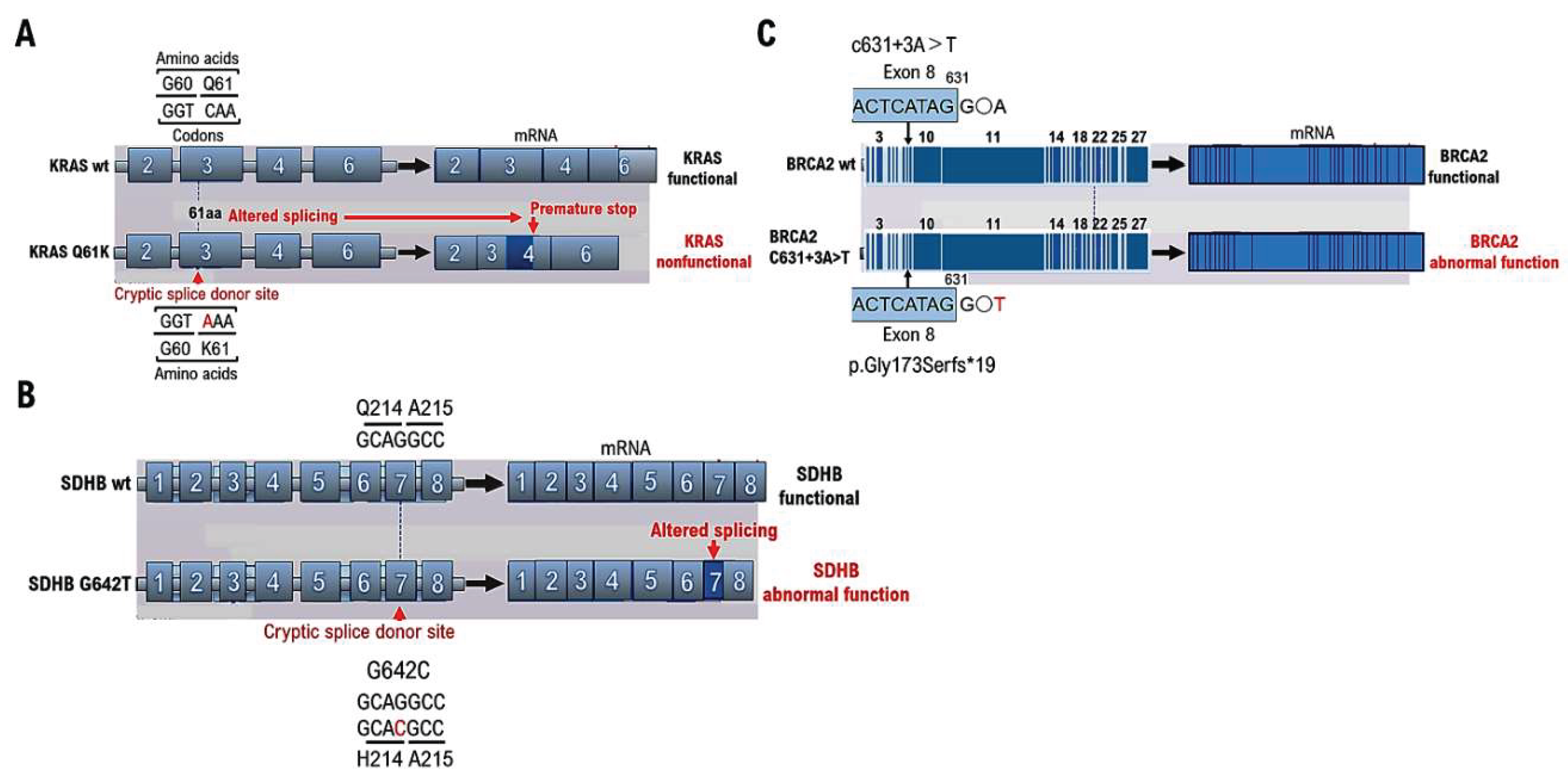

11] and has no effect on the organism. Missense mutations alter a single amino acid and have serious consequences if the change alters the function of the protein. However, the KRAS mutations detected through cancer gene panel testing at cancer genome medical facilities may be classified as VUSs using ClinVar. However, even silent KRAS gene mutations create a base sequence that indicates the start of a new intron

note1, which can lead to splicing (

Figure 1A). The primary protein structure is substantially altered in such cases; therefore, the gene mutation is not a VUS but a pathogenic variant. Therefore, caution is required when determining VUSs using ClinVar, as gene mutations resulting from gene mutation mechanisms may become splicing sites.

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL) are rare endocrine hypertensive diseases that are often curable [

12]. However, the signs and symptoms of PPGL are nonspecific and diverse. Furthermore, PPGL are difficult to differentiate from panic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and other diseases. Therefore, medical staff should consider PPGL during diagnosis. PPGL were incidentally discovered during imaging tests for other diseases. Test results must be carefully examined using random urine metanephrine and normetanephrine measurements, magnetic resonance imaging, and metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy because PPGL are asymptomatic [

13]. Genetic mutations are present in approximately 30% of PPGL cases. Mutation testing should be performed for the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A gene for suspected von Hippel–Lindau disease, particularly in cases where tumors occur in families with PPGL, tumors develop at a young age, and hereditary tumor syndrome is suspected [

13,

14].

Testing for succinate dehydrogenase complex iron sulfur subunit B (SDHB) mutations is recommended for tumors with no multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A gene mutations and von Hippel–Lindau disease is ruled out. SDHB is a subunit of succinate dehydrogenase involved in the TCA cycle [

15]. The SDHB mutation G642C was determined to be a VUS as a result of a cancer gene panel test (GenMinTOP) on a 41-year-old male patient with PPGL (

Figure 1B). PPGL onset was early in life, despite the lack of known family history of PPGL; therefore, we performed further genomic analyses. As a result, we found that mutation of the base G642C in the gene could have caused splicing abnormalities, when checking the annotation content of the results of the cancer gene panel test, although the amino acid Q214H mutation was a VUS (

Figure 1B). The results of RNA sequencing were analyzed using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)

note 2, and splicing was confirmed to have occurred due to base mutations. As in this case, splicing may occur because of base mutations even if the amino acid mutation (Q214H) is determined to be a VUS using ClinVar. Therefore, the presence of pathogenic variants should be reconfirmed based on medical information such as the age at the onset of malignant tumors and family history.

Approximately 5–10% of breast cancers are hereditary [

16]; however, a detailed professional evaluation is required to verify if the breast cancer case is hereditary. Hereditary breast cancer is possible in people with early-onset breast cancer (onset age of 35 years or younger), bilateral or multiple breast cancer, male breast cancer, and both ovarian and breast cancer, even in the absence of a family history of breast or ovarian cancer [

17]. In our case, multiple family members had breast cancer, suggesting hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility genes (BRCAI and BRCA2) was performed before the onset of ovarian cancer (HBOC) using BRAC Analysis (Myliad Co., Ltd. MA, USA) to prescribe risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy [

18] and a PARP inhibitor (i.e., olaparib). The c631+3A>T mutation was identified as a VUS through ClinVar analysis (

Figure 1C). However, we found that the c631+3A>T base mutation resulted in p.Gly173SerFs*19, which was identified as a pathogenic variant when examined using the Medical Genomics Reviews Knowledge base for genomic medicine in Japanese (MGenReviews; National Institute of Global Health and Medicine, National Health Research Organization/National Center for Global Health and Medicine) [

19], a database that compiles the results of analyses of mutations specific to Japanese people.

4. Discussion

FoundationOne® CDx Cancer Genomic Profile (FMI, Cambridge, MA, USA) and OncoGuide™ NCC oncopanel (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan) were approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan as cancer gene panel tests for solid tumors and were covered by insurance as of June 2019. Subsequently, cancer gene panel testing was initiated in Japan to guide genomic cancer treatment. Our medical staff performed cancer gene panel testing from 2019 to March 2015 to identify new treatment strategies for approximately 5,500 cases of progressive and metastatic malignant tumors. A silent mutation does not result in a change in the amino acid sequence of a protein, even if occurring in the DNA sequence of a gene, and does not affect the organisms. Missense mutations alter a single amino acid and may have serious consequences if the change alters protein function. In addition, the gene mutations detected by cancer gene panel testing at cancer genome medical facilities have been determined as VUSs using ClinVar. However, new splicing may occur due to genetic mutation even if a mutation is silent due to genetic mutation. The primary structure of the protein considerably changes in such cases; these gene mutations are pathogenic variants rather than VUSs. Therefore, genetic mutations are resulting in new splice sites.

An integrated approach that includes both epigenetic and genetic factors has been developed for identifying early cancer signals [

20]. Another approach that combines multiple cell-free DNA features and provides details on cancer onset and genomes was devised to improve the detection of cancer onset [

21,

22]. Therefore, the cancer genome, in addition to surgically removed tissues, is tested using liquid biopsies in cancer genome medicine. A Korean research team is investigating a next-generation sequencing platform based on cell-free DNA analysis, the AlphaLiquid® Screening Platform [

23]. Whole-genome methylation sequencing (WGMS) was used to quantify the DNA methylation patterns in the CpG regions throughout the genome. The results of the clustering analysis of data obtained from patients with cancer and healthy individuals enabled their differentiation as well as the estimation of the tissues in which the cancer originated. This platform simultaneously analyzes whole-genome DNA methylation sites, copy number alterations, and fragment patterns in noninvasively isolated cell-free DNA samples using WGMS. In particular, this platform employs enzymatic methylation conversion technology for DNA methylation analysis, which minimizes the damage caused by fragmentation and coverage bias, and enables the acquisition of highly accurate data [

24].

Gene mutations play a major role in the development of cancer and malignant tumors. However, the base sequences of genes change within the human body to adapt to long-term differences in the environment, such as differences in diet and temperature [

25]. Consequently, the gene sequences differ among races, suggesting the involvement of pathogenic variants during the development and progression of cancer and malignant tumors differs among races. The databases used in clinical practice to re-examine pathogenic variants include ClinVar (National Center for Biotechnology Information), OncoKB (an FDA-recognized human genetic variant database), and Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC, which are based on data obtained from Western patients. Therefore, a database of the pathogenic variants for each race must be build. New treatments for progressive and metastatic malignant tumors are being developed using cancer gene panel testing. However, the types of antitumor agents that can be used against pathogenic variants, which are identified based on various factors, are limited. Several clinical studies have investigated the efficacy of new regimens for advanced and metastatic malignant tumors to improve current cancer treatment.

5. Conclusion

Cancer gene panel testing has led to considerable advances in personalized cancer treatment. However, the results of cancer genome panel testing depend on a database built from the medical information of patients in Europe and the United States. Human genes differ with race; therefore, test results are not always correct. Unexpected splicing can occur because of base mutations that can cause intron start signals. Therefore, medical staff must carefully examine the test results. Additionally, database of cancer genomes that includes gene mutations specific to Asian populations must be built.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval and Consent to Participate

This research on human cancer genome information derived from results of cancer genome gene panels was conducted at the Kyoto University, its affiliated hospitals, and the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center in accordance with institutional guidelines (IRB approval no. 50-201504, NHOKMC-2023-2, and H31-cancer-2). All patients were briefed on the clinical study and agreed to take part in the present study by providing informed consent for participation. Our clinical research complied with the Helsinki Statement. Ethics committee name: IRB of the National Hospital Organization Headquarters (approval code: H31-cancer-2; approval date: November 09, 2019, and June 17, 2013). Ethics committee name: IRB of Kyoto University (approval code: R34005; approval date: August 01, 2022).

Ethical compliance with human study

This study involves research with human participants and was approved by the institutional ethics committee(s) and IRBs. This manuscript contains personal and/or medical information and a case report/case history about an identifiable individual; therefore, it has been sufficiently anonymized in line with our anonymization policy. The authors obtained direct consent from the patient. The authors attended research ethics education through the Education for Research Ethics and Integrity (APRIN e-learning program (eAPRIN)) agency. The completion numbers for the authors are AP0000151756, AP0000151757, AP0000151769, and AP000351128. This study involves research with animal materials and was approved by the institutional ethics committee(s) and IRBs (Ethics Committee for research with animals in National Hospital Oaganization Headquarter; Meguro, Tokyo, Japan). Ethics committee name: IRB of the National Hospital Organization Headquarters (approval code: H31-1-2; approval date: November 09, 2019, and June 17, 2023, approved code: R07-1-2).

ARRIVE checklist documentation

We never use live animals, the protocol of our research does not involve any live animals.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors.

Author Contributions

TH, and Ik were involved in the study design, data collection, data review and interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH, and IK were involved in the literature search, study design, data collection, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH, and IK were involved in data collection and interpretation. TH, and IK were involved in data collection and interpretation and manuscript writing. TH, and IK were involved in the study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. TH and IK were the medical leads for AstraZeneca, and they participated in the data collection and evaluation and manuscript writing and editing. TH and IK were the lead physicians and were involved in the study design and conduct, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript review.

Funding

This clinical research was performed using research funding from the following: Japan Society for Promoting Science for TH (grant no. 19K09840), START-program Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) for TH (grant no. STSC20001), National Hospital Organization Multicenter Clinical Study for TH (grant no. 2019-Cancer in general-02), and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant no. 22ym0126802j0001), Tokyo, Japan. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on various websites and have also been made publicly available. More information can be found in the first paragraph of the Results section. The transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at

Informed Consent Statement

This research includes clinical/human materials, therefore Informed consent is required.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Yoshiihiro Kawaoka at The Institution of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo for providing clinical research information. The authors also want to acknowledge all medical staff for clinical research at Kyoto University School of Medicine and the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center. We also appreciate Chugai Pharma Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (Kitaku, Tokyo, Japan) and Sysmex Corporation. (Kobe, Hyogo, Japan) for providing medical imformation.

Notes

| Note 1 |

Intron base sequence: Intron locations must be determined to remove introns via RNA splicing. Rules exist for the base sequence of introns, and almost all introns (> 99%) start with GU and end with AG, which is called the GU-AG rule. The 5' side of the GU sequence (the 5' end of the intron) is called the 5' splice site, and the 3' side of the AG sequence (the 3' end of the intron) is called the 3' splice site. Another important sequence is the branch site, located 18–40 nucleotides upstream of the 3’ splice site. The consensus sequence for the branch site in yeast is UACUAAC and YNYYRAY in animals, with adenine (A), shown in red, being the branch site. Downstream of the branching site is a region of consecutive pyrimidines (C and U). |

| Note 2 |

Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) is a tool for visualizing next-generation sequencing mapping results and annotation information. IGV has been used for confirming the level of gene expression from RNA-seq mapping results, searching for single-nucleotide polymorphisms from whole-genome sequencing results, and narrowing candidate regions for cis-regulatory sequences from ChiP-seq and ATAC results. |

References

- Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, Sherman RE, Aberle LH, Tasneem A. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. JAMA. 2012 May 2;307(17):1838-47. [CrossRef]

- Vasan N, Baselga J, Hyman DM. A view on drug resistance in cancer. Nature. 2019 Nov;575(7782):299-309. [CrossRef]

- Modell SM, Citrin T, Kardia SL. Laying Anchor: Inserting Precision Health into a Public Health Genetics Policy Course. R. Healthcare (Basel). 2018 Aug 3;6(3):93. [CrossRef]

- Kurian AW, Abrahamse P, Furgal A, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Hodan R, Tocco R, Liu L, Berek JS, Hoang L, Yussuf A, Susswein L, Esplin ED, Slavin TP, Gomez SL, Hofer TP, Katz SJ. Germline Genetic Testing After Cancer Diagnosis. JAMA. 2023 Jul 3;330(1):43-51. [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Villanueva M, Hidalgo-Pérez L, Rios-Romero M, Cedro-Tanda A, Ruiz-Villavicencio CA, Page K, Hastings R, Fernandez-Garcia D, Allsopp R, Fonseca-Montaño MA, Jimenez-Morales S, Padilla-Palma V, Shaw JA, Hidalgo-Miranda A. Cell-free DNA analysis in current cancer clinical trials: a review. Br J Cancer. 2022 Feb;126(3):391-400. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?term=.

- https://www.oncokb.org/.

- https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/login.

- Lu J, Zhou C, Pan F, Liu H, Jiang H, Zhong H, Han B. Role of silent mutations in KRAS -mutant tumors. Chin Med J (Engl). 2025 Feb 5;138(3):278-288. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Li R, Li X. Report of a child with Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome due to a novel variant of ASXL3 gene and a literature review. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2024 Aug 10;41(8):966-972. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi Y, Chhoeu C, Li J, Price KS, Kiedrowski LA, Hutchins JL, Hardin AI, Wei Z, Hong F, Bahcall M, Gokhale PC, Jänne PA. Silent mutations reveal therapeutic vulnerability in RAS Q61 cancers. Nature. 2022 Mar;603(7900):335-342. [CrossRef]

- Chung SM. J Yeungnam Screening and treatment of endocrine hypertension focusing on adrenal gland disorders: a narrative review. Med Sci. 2024 Oct;41(4):269-278. [CrossRef]

- Que FVF, Ishak NDB, Li ST, Yuen J, Shaw T, Goh HX, Zhang Z, Chiang J, Yeo SY, Chew LL, Thng CH, Ngeow J. Utility of Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging Surveillance in Children and Adults With Cancer Predisposition Syndromes: A Retrospective Study. JCO Precis Oncol. 2025 Mar;9:e2400642. [CrossRef]

- Shirali AS, Clemente-Gutierrez U, Huang BL, Lui MS, Chiang YJ, Jimenez C, Fisher SB, Graham PH, Lee JE, Grubbs EG, Perrier ND. Pheochromocytoma recurrence in hereditary disease: does a cortical-sparing technique increase recurrence rate? Surgery. 2023 Jan;173(1):26-34. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, Sun K, Lan Z, Song W, Cheng L, Chi W, Chen J, Huo Y, Xu L, Liu X, Deng H, Siegenthaler JA, Chen L. Tenofovir and adefovir down-regulate mitochondrial chaperone TRAP1 and succinate dehydrogenase subunit B to metabolically reprogram glucose metabolism and induce nephrotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2017 Apr 11;7:46344. [CrossRef]

- Lux MP, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: review and future perspectives. J Mol Med (Berl). 2006 Jan;84(1):16-28. [CrossRef]

- Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, Baker SM, Berlin M, McAdams M, Timmerman MM, Brody LC, Tucker MA. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 1997 May 15;336(20):1401-8. [CrossRef]

- Lee EG, Kang HJ, Lim MC, Park B, Park SJ, Jung SY, Lee S, Kang HS, Park SY, Park B, Joo J, Han JH, Kong SY, Lee ES.Different Patterns of Risk Reducing Decisions in Affected or Unaffected BRCA Pathogenic Variant Carriers. Cancer Res Treat. 2019 Jan;51(1):280-288. [CrossRef]

- https://mgen.ncgm.go.jp/.

- Hayashi T, Konishi I. Correlation of anti-tumour drug resistance with epigenetic regulation. Br J Cancer. 2021 Feb;124(4):681-682. [CrossRef]

- Cell-free DNA TAPS provides multimodal information for early cancer detection. Siejka-Zielińska P, Cheng J, Jackson F, Liu Y, Soonawalla Z, Reddy S, Silva M, Puta L, McCain MV, Culver EL, Bekkali N, Schuster-Böckler B, Palamara PF, Mann D, Reeves H, Barnes E, Sivakumar S, Song CX. Sci Adv. 2021 Sep 3;7(36):eabh0534. [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi A, Liu MC, Klein EA, Venn O, Hubbell E, Beausang JF, Gross S, Melton C, Fields AP, Liu Q, Zhang N, Fung ET, Kurtzman KN, Amini H, Betts C, Civello D, Freese P, Calef R, Davydov K, Fayzullina S, Hou C, Jiang R, Jung B, Tang S, Demas V, Newman J, Sakarya O, Scott E, Shenoy A, Shojaee S, Steffen KK, Nicula V, Chien TC, Bagaria S, Hunkapiller N, Desai M, Dong Z, Richards DA, Yeatman TJ, Cohn AL, Thiel DD, Berry DA, Tummala MK, McIntyre K, Sekeres MA, Bryce A, Aravanis AM, Seiden MV, Swanton C. Evaluation of cell-free DNA approaches for multi-cancer early detection. Cancer Cell. 2022 Dec 12;40(12):1537-1549.e12. [CrossRef]

- https://www.imbdx.com/eng/about/profiling.php.

- Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Vaisvila R, Ponnaluri VKC, Sun Z, Langhorst BW, Saleh L, Guan S, Dai N, Campbell MA, Sexton BS, Marks K, Samaranayake M, Samuelson JC, Church HE, Tamanaha E, Corrêa IR Jr, Pradhan S, Dimalanta ET, Evans TC Jr, Williams L, Davis TB. Genome Res. 2021 Jul;31(7):1280-1289. [CrossRef]

- Ames BN. Dietary carcinogens and anti-carcinogens. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1984;22(3):291-301. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).