Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Clinical Applications and Discussion

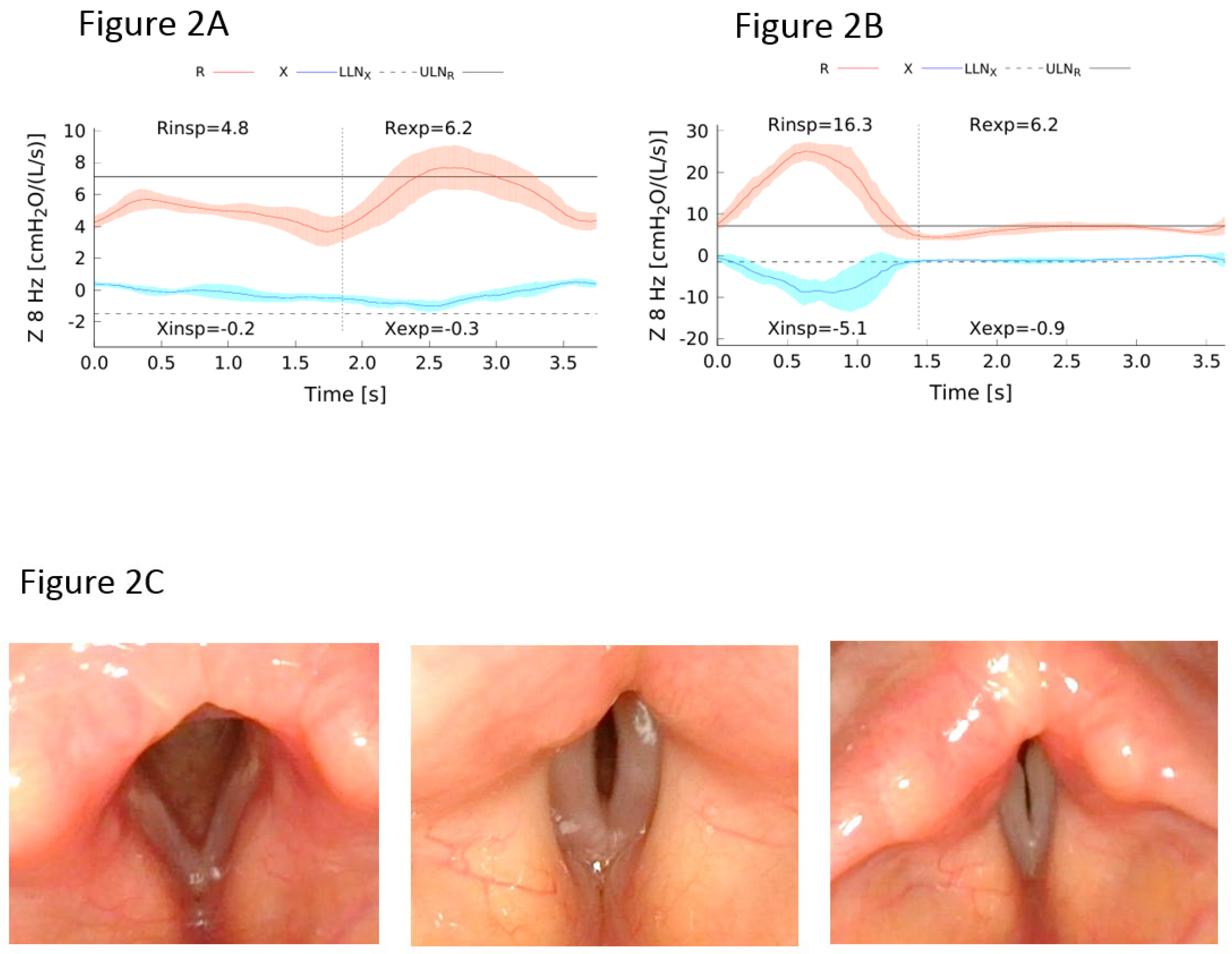

Lung Function Evaluation

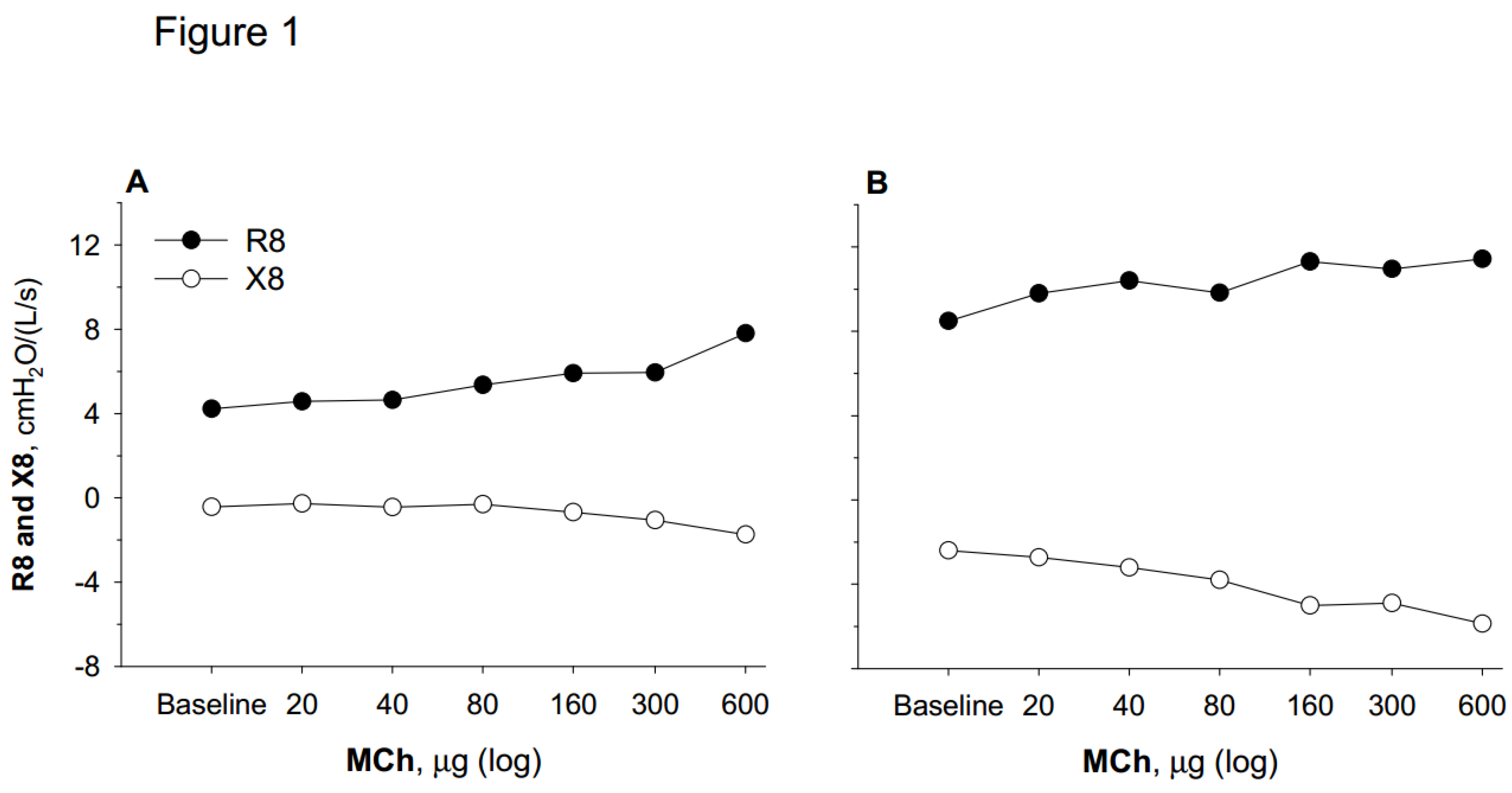

Bronchodilator Response and Hyperresponsiveness

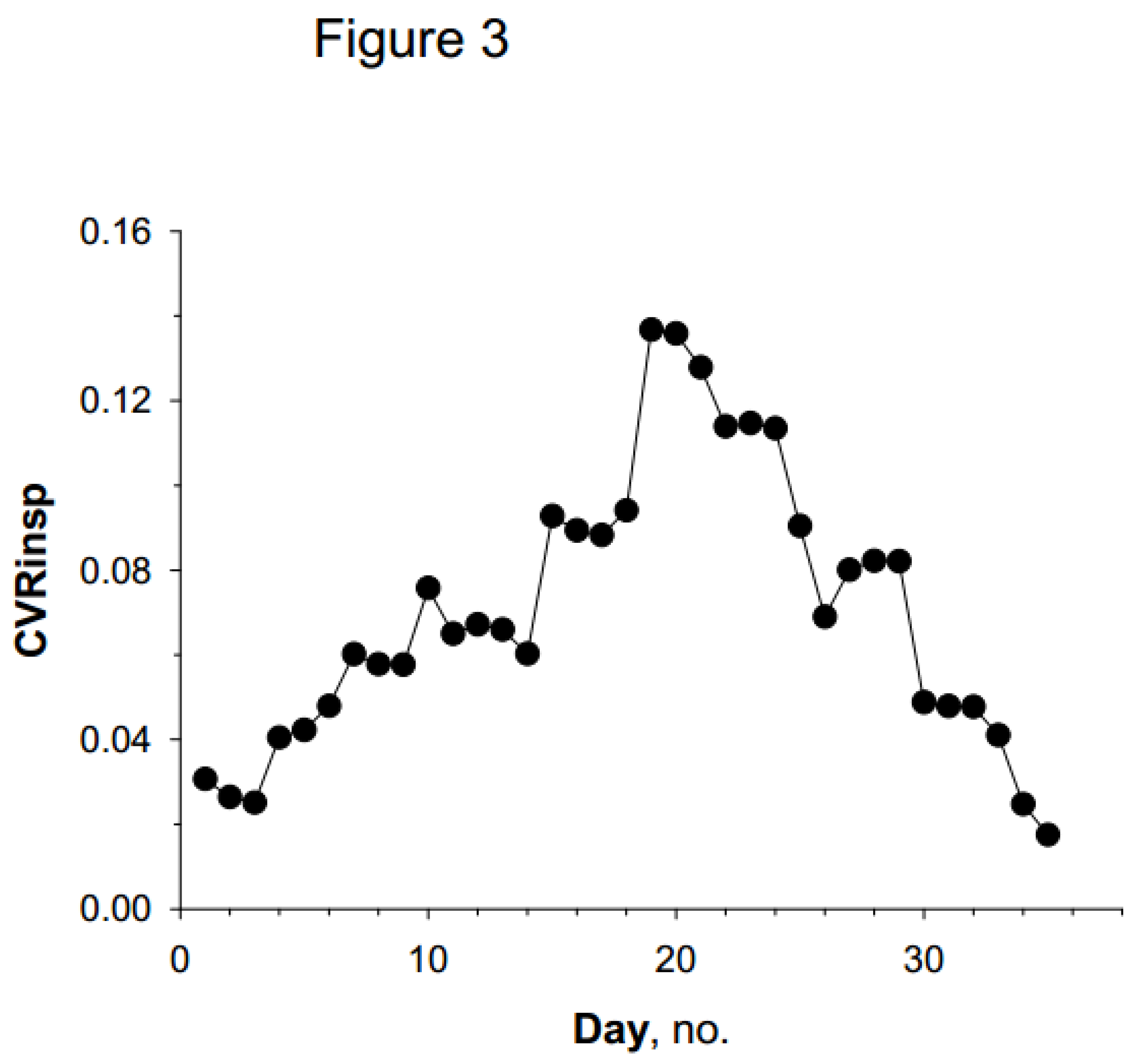

Temporal Variability of Asthma

Conclusions and Future Directions

References

- Beydon, N. , Davis, S.D.; Lombardi, E.; Allen, J.L.; Arets, H.G.M.; Aurora, P.; Bisgaard, H.; Davis, G.M.; FM; Eigen, H.; Gappa, M.; et al.; American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Working Group on Infant and Young Children Pulmonary Function Testing. (2007). An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 1304–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, E.A.; Kuehni, C.E.; Turner, S.; Goutaki, M.; Holden, K.A.; de Jong, C.C.M.; Lex, C.; Lo, D.K.H.; Lucas, J.S.; Midulla, F.; et al. European Respiratory Society clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in children aged 5-16 years. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2004173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elenius, V.; Chawes, B.; Malmberg, P.L.; Adamiec, A.; Ruszczyński, M.; Feleszko, W.; Jartti, T. Lung function testing and inflammation markers for wheezing preschool children: A systematic review for the EAACI Clinical Practice Recommendations on Diagnostics of Preschool Wheeze. EAACI Preschool Wheeze Task Force for Diagnostics of Preschool Wheeze. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.; Latzin, P.; Verbanck, S.; Hall, G.H.; Horsley, A.; Gappa, M.; Thamrin, C.; Arets, H.G.M.; Aurora, P.; I. Fuchs, S.I.; et al. Consensus statement for inert gas washout measurement using multiple- and singlebreath tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 41, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlin, G. , Eber, E.; Aurora, P.; Lødrup Carlsen, K.C.L.; Ratjen, F.; Dankert-Roelsee, J.E.; Ross-Russell,R.I.; Turner, S.; F. Midulla, F.; Baraldi, E.; et al. Paediatric respiratory disease: past, present and future. Paediatric Assembly contribution to the celebration of 20 years of the ERS. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60: 2101499.

- Merkus, P.J.F.M.; Stocks, J.; Beydon, N.; Lombardi, E.; Jones, M.; McKenzie, S.A.; Kivastik, J.; Arets, B.G.M.; Stanojevic, S. Reference ranges for interrupter resistance technique: the Asthma UK Initiative. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, C.; Simpson, S.J.; Lombardi, E.; Parri, N.; Cuomo, B.; Palumbo, M.; Maurizio de Martino, M.; Shackleton, C.; Verheggen, M.; Tania Gavidia MIH, T.; et al. Respiratory impedance and bronchodilator responsiveness in healthy children aged 2–13 years. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, J.; Stanojevic, S.; Welsh, L.; Lum, S.; Badier, M.; Beardsmore,C.; Custovic, A.; Nielsen, K.; Paton, J.; Tomalak, W.; et al. Reference equations for specific airway resistance in children: the Asthma UK initiative. Eur. Respir. J. 2010 36, 622–629. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, K.A.; Stanojevic, S.; Chavez, L.; Johnson, N.; Bowerman, C.; Hall, G.L.; Latzin, P.; O’Neill, K.; Robinson, P.D.; Stahl. , M.; et al. on behalf of the contributing GLI MBW task force members. Global Lung Function Initiative reference values for multiple breath washout indices. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2400524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Viegi, G.; Brusasco, V.; Crapo, R.O.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; van der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; Hankinson, J.; et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, H.J.; Ferkol, T.W. The global burden of respiratory disease-impact on child health. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2014, 49, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Townshend, J.; Brodlie, M. Diagnosis and management of asthma in children. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2022, 6, e001277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/GINA-2024-Strategy-Report-24_05_22_WMS.pdf.

- Hyatt, R.E. Forced expiration. In: Macklem PT, Mead J (eds). Handbook of Physiology. Section 3, vol. III, part 1. The respiratory system. Mechan ics of breathing. American Physio logical Society, Bethesda 1986; 295-314.

- Perrem, L.; Wilson, D.; Dell, S.D.; and Ratjen, F. Development and Validation of an Algorithm for Quality Grading of Pediatric Spirometry: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gochicoa-Rangel, L.; Vargas, C.; García-Mujica, M.; Bautista-Bernal, A.; Salas-Escamilla, I.; Perez Padilla, R.; Torre-Bouscoulet, L. Quality of Spirometry in 5-to-8-Year-Old Children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plas, K.; P Vooren, P. The "opening" interruptor. A new variant of a technique for measuring respiratory resistance. Eur. J. Respir. Dis. 1982, 63, 449–548. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, J.H.; Baconnier, P.; Milic-Emili, J. A theoretical analysis of interrupter technique for measuring respiratory mechanics. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988, 64, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y.; Bridge, P.D.; Dundas, I.; Pao, C.S.; Healy, M.I.R.; McKenzie, S.A. Repeatability of airway resistance measurements made using the interrupter technique Thorax 2003, 58, 344–347. [CrossRef]

- Peslin, R.; Fredberg, J.J. Oscillation Mechanics of the Respiratory System. Supplement 12. Handbook of Physiology, The Respiratory System, Mechanics of Breathing, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Oostveen, E.; MacLeod, D.; Lorino, H.; Farré, R.; Hantos, Z.; Desager, K.; Marchal, F.; ERS Task Force on Respiratory Impedance Measurements-. The forced oscillation technique in clinical practice: methodology, recommendations and future developments. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 1026–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.G.; Bates, J.; Berger, K.I.; Calverley, P.; de Melo, P.L.; Dellacà, R.L.; Farré, R.; Hall, G.L.; Ioan, I.; Irvin, C.G.; et. al. Technical standards for respiratory oscillometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1900753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.G. Clinical application of forced oscillation. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 14, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducharme, F.M.; Davis, G.M.; Ducharme, G.R. Pediatric reference values for respiratory resistance measured by forced oscillation. Chest 1998, 113, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, C.; Simpson, S.J.; Lombardi, E.; Parri, N.; Cuomo, B.; Palumbo, M.; de Martino, M.; Shackleton, C.; Verheggen, M.; Gavidia, T.; et al. Respiratory impedance and bronchodilator responsiveness in healthy children aged 2–13 years. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbanck, S.; Schuermans, D.; Van Muylem, A.; Paiva, M.; Noppen, M.; Vincken, W. Ventilation distribution during histamine provocation. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 83, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downie, S.R.; Salome, C.M.; Verbanck, S.; Thompson, B.; Berend, N.; King, G.G. Ventilation heterogeneity is a major determinant of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, independent of airway inflammation. Thorax 2007, 62, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, R.; Stanojevic, S.; Klingel, M.; Pizarro, M.E.; Hall, G.L.; Ramsey, K.; Foong, R.; Saunders, C.; Robinson, P.D.; Webster, H.; et al. A Systematic Approach to Multiple Breath Nitrogen Washout Test Quality. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, J.G.; Winkler, T.; Musch, G; Vidal Melo, M. F.; Layfield, D.; Tgavalekos, N.; Fischman, A.J.; Callahan, R.J.; Bellani, G.; Harris, R.S. Self-organized patchiness in asthma as a prelude to catastrophic shifts. Nature 2005, 434, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, T.; Venegas, J.G. Complex airway behavior and paradoxical responses to bronchoprovocation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 103, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tgavalekos, N.T.; Venegas, J.G.; Suki, B.; Lutchen, K.R. Relation between structure, function, and imaging in a three-dimensional model of the lung. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 31, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutting, S.; Chapman, D.G.; Farah, C.S.; Thamrin, C. Lung heterogeneity as a predictor for disease severity and response to therapy. Current Opinion in Physiology 2021, 22.

- Antonelli, A.; Crimi, E.; Gobbi, A.; Torchio, R.; Gulotta, C.; Dellaca, R.; Scano, G.; Brusasco, V.; Pellegrino, R. Mechanical correlates of dyspnea in bronchial asthma. Physiol. Rep. 2013, 1, e00166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Wilson, O.; Jenouri, G.; Rodarte, J.R. Lung mechanics during induced bronchoconstriction. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 81, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salome, C.M.; Thorpe, C.W.; Diba, C.; Brown, N.J.; Berend, N.; King, G.G. Airway re-narrowing following deep inspiration in asthmatic and nonasthmatic subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusasco, V; Pellegrino, R. Complexity of factors modulating airway narrowing in vivo: relevance to assessment of airway hyperresponsiveness. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 4305–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, C.L.; Kenyon, C.M.; Olivenstein, R.; Macklem, P.T.; Maksym, G.N. Homeokinesis and short-term variability of human airway caliber. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91: 1131-1141. [CrossRef]

- Gulotta, C.; Suki, B.; Brusasco, V.; Pellegrino, R.; Gobbi, A.; Pedotti, A.; Dellacà, R.L. Monitoring the Temporal Changes of Respiratory Resistance: A Novel Test for the Management of Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 185, 1330–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, A.; Gulotta, C.; Suki, B.; Mellano, E.; Pellegrino, R.; Brusasco, V.; Dellacà, R.L. Monitoring of respiratory resistance in the diagnosis of mild intermittent asthma Clin. Exper. Allergy. 2019, 49, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).