1. Introduction

Camel milk is a high-quality milk with high nutritional value and health benefits. Camel milk contains a variety of nutrients such as fat, protein, vitamins, lactose, etc. [

1,

2,

3]. Research has demonstrated that camel milk possesses several bioactive properties, including anti-cancer effects [

4] (Magjeed, 2005), hypoallergenic characteristics [

5] (Shabo et al., 2005), and anti-diabetic potential [

6] (Agrawal et al., 2003).

Camel milk has recently emerged on the international dairy market, largely due to advances in powdered milk production, which offers an effective means of preserving this highly perishable product for future use. Since camel milk is often produced in remote areas, far from consumer markets, dehydration presents the most efficient option for large-scale transportation. This method also helps retain the milk’s nutritional qualities. Among the available techniques, lyophilisation (freeze-drying) is considered one of the most efficient for producing milk powder.

Camel milk powder commands a premium market price of approximately €60-100 per kilogram, significantly higher than other dairy powders including cow, goat, and mare’s milk products. This presents substantial economic opportunities for camel-rearing regions, particularly for countries like Kazakhstan, where camel breeding has deep cultural and historical roots. The country’s vast territorial expanses provide ideal conditions for herd expansion, while existing pastoral traditions offer a strong foundation for commercial development. The combination of high market value and favourable production conditions makes camel milk powder an attractive commodity for pastoral economies with established camel farming infrastructure.

The process of transforming fresh camel milk into a powder form comes with a significant financial burden, requiring specialised tools and substantial technological investment. Vacuum sublimation drying has emerged as a leading technique for creating camel milk powder, demonstrating its ability to maintain both the nutritional content and desirable taste characteristics of the milk [

7].

However, freeze-drying (lyophilisation) remains more energy- and time-intensive than alternative drying methods, with current industrial systems requiring 20–35 hours to produce high-quality output. This economic and operational challenge drives ongoing research to improve process efficiency-particularly in reducing energy use and production costs. Numerical simulation of heat and mass transfer during lyophilisation offers a promising pathway for optimisation, which is the focus of this study.

Substantial improvements in freeze-drying process modelling have been achieved through three decades of development in numerical simulation techniques for simultaneous heat and mass transfer [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Liapis and Litchfield (1979) [

8] introduced an optimal control framework for freeze-drying, formulating the process as a time-minimisation problem with constraints on final moisture content. Their model considered radiator energy output and chamber pressure as control variables, laying the groundwork for subsequent dynamic modelling efforts. Building upon this, Liapis and Marchello (1984) [

9] expanded the modelling approach to encompass both primary and secondary drying stages. Their comprehensive analysis incorporated heat and mass transfer mechanisms, providing a more detailed understanding of the freeze-drying process dynamics. Tang, Liapis, and Marchello (1986) [

10] further advanced the field by developing a multi-dimensional model describing lyophilisation in vials. This model accounted for spatial variations and provided insights into the effects of vial geometry and product configuration on drying behaviour. Mascarenhas, Akay, and Pikal (1997) [

11] introduced a finite element analysis approach to simulate the freeze-drying process. Their computational model enabled the prediction of temperature and moisture profiles within the product, facilitating optimisation of process parameters. Nastaj and Witkiewicz (2009) [

12] focused on the mathematical modelling of primary and secondary vacuum freeze-drying stages under microwave heating. Their work highlighted the potential of microwave-assisted freeze-drying to reduce processing time while maintaining product quality. Georgiev et al. [

13] (2009) addressed the computational challenges associated with large-scale simulations by implementing adaptive time-stepping methods. Their approach improved the efficiency and accuracy of simulations, particularly for complex parabolic problems encountered in freeze-drying modelling. Zhang, Zhang, and He (2010) [

14] investigated the impact of a sample’s porous structure on vacuum freeze-drying. Their study emphasised the significance of microstructural characteristics in influencing drying kinetics and final product quality. Scutellà et al. (2017) [

15] developed a 3D mathematical model to understand atypical heat transfer observed in vial freeze-drying. Their model incorporated various heat transfer mechanisms, including conduction, convection, and radiation, providing a comprehensive tool for analysing and optimising the freeze-drying process.

Collectively, these studies have significantly contributed to the advancement of freeze-drying process modelling, offering valuable insights and tools for improving efficiency, product quality, and scalability in the pharmaceutical and food industries.

Key developments in recent research [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] have substantially improved our fundamental understanding of the transient heat and mass transfer mechanisms governing lyophilisation processes.

Numerical modelling of heat and mass transfer during milk freeze-drying in vials was investigated in [

16], with a focus on phase transitions and mass transport. The study highlighted the critical role of heat transfer and moisture removal in determining process efficiency, offering insights for optimising dairy industry applications.

A multiphase porous media model for predicting temperature and moisture distribution during freeze-drying was developed in [

17], contributing to enhanced process control. Further advancing this field, [

18] combined computational simulations with experimental validation to analyse vacuum freeze-drying of delicate materials, providing practical guidance for industries processing heat-sensitive products.

We extend the scope of our earlier work [

21] through three-dimensional modelling, systematic vapour pressure assessment, and detailed parametric investigations. This study investigates the heat and mass transfer dynamics during the vacuum sublimation drying of camel milk, employing numerical simulations and experimental validation. Gaining a comprehensive grasp of these underlying principles is crucial for refining the drying procedure, maximising its effectiveness, and guaranteeing the superior quality of the final product. Using computational models, our research seeks to uncover the intricate relationships between heat transfer, mass movement, and material characteristics as they occur during the drying phase.

Despite its advantages in preserving nutritional quality, vacuum freeze-drying is widely recognised as one of the most energy-intensive food processing methods, with specific energy consumption often exceeding that of conventional drying techniques. This poses challenges in terms of environmental impact and economic feasibility, especially in large-scale production. Therefore, optimising freeze-drying conditions to minimise energy input while maintaining product quality is essential. This study aims to contribute toward energy-efficient process design by systematically analysing the influence of drying parameters on both drying performance and energy consumption.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we experimentally investigate the freeze-drying process of camel milk and present a numerical method supported by a modeling tool and governing equations. To validate the proposed model, numerical results are compared with experimental data.

2.1. Experimental Study

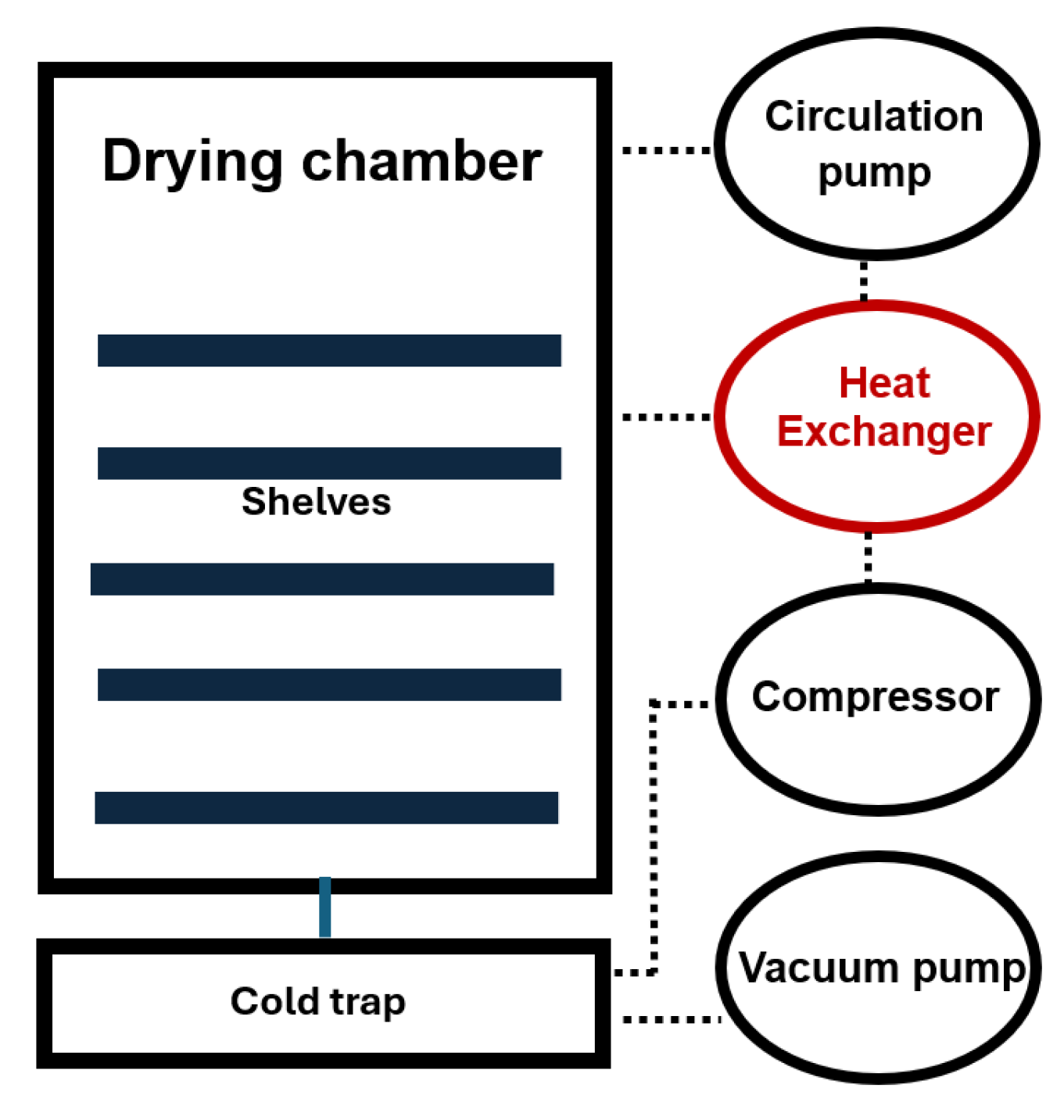

Experiments were performed using a shelf-type vacuum freeze-dryer (model ZLGJ-300) as the primary apparatus, shown in

Figure 1. In detail, equipment information provided in reference [

27]. The sample is introduced into a drying chamber, where, at reduced temperatures and pressures, the ice present within the sample transforms directly into water vapour. This vapour is subsequently channeled through a vacuum network to a designated condensation chamber for collection.

Camel milk was poured into stainless steel trays cm at depths of 4-8 mm and placed in the freeze-drying chamber. A temperature probe was inserted into the sample to monitor core temperature. Samples were pre-frozen at for 3 hours, after which the chamber pressure was reduced to 95 Pa to initiate sublimation, with heat supplied through the shelves. Moisture loss was assessed by weighing samples every 3 hours, and moisture content was calculated from mass reduction.

Experiments were conducted using sample thicknesses of 4, 6, and 8 mm under chamber pressures of 95, 105, and 115 Pa. Preliminary trials with thicknesses greater than 8 mm showed that the final moisture content exceeded 7%, which is unacceptable by industrial standards, and the drying time was excessively long. As a result, sample thicknesses above 8 mm were excluded from this study.

Temperature and pressure were logged every 3 minutes during drying. The complete sublimation process lasted 22–25 hours, depending on sample thickness. Drying was considered complete when the sample’s weight stabilised, indicating the removal of free moisture. A visual of the dried product is shown in

Figure 2.

Structural changes such as cracks, observed in

Figure 2, arise from mechanical stresses due to uneven drying and shrinkage between frozen and dried layers. Although the current model assumes a rigid porous matrix, these deformations can affect heat and mass transfer by altering vapor pathways and surface exposure. Cracks may enhance mass transfer but increase heat loss, while flakes can act as thermal barriers. Future models could address these effects using a poromechanical framework.

Measurement of Moisture Content. To monitor moisture content during vacuum sublimation drying of mare’s milk, we used the Evlas-2M moisture analyser, a precise instrument for analysing moisture in food and biological samples. Dried samples were collected every 3 hours, cooled to room temperature, and weighed before and after drying using a high-precision balance. Moisture content was calculated as:

where.

- is the mass of the sample before drying (wet mass),

is the mass of the sample after complete drying (dry mass). Measurements were averaged over three trials, confirming a final moisture content below 4%, in line with industry standards. The analyzer was regularly calibrated, and results were used to validate the numerical model.

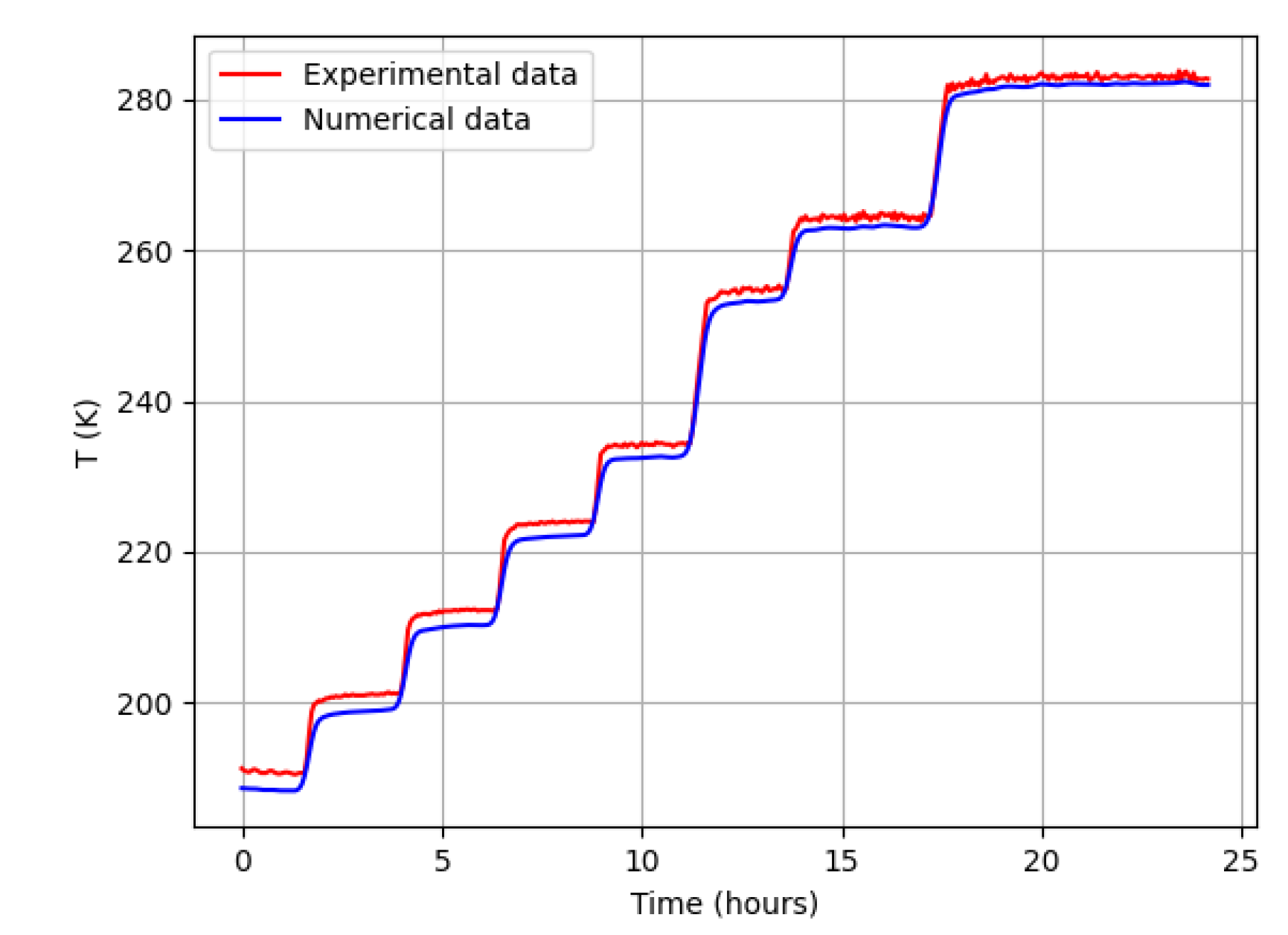

Experiment and Simulation Verification During the sublimation stage, the temperature was increased stepwise until reaching the target value. These stepwise changes were incorporated into the numerical simulation.

Figure 3 shows the comparison between simulated and experimental temperature profiles during both the primary and secondary drying stages for the 6 mm thick sample. The temperature was measured at the central part of the tray with the camel milk.

Figure 3 demonstrates a strong correlation between the numerical simulation results and the experimental temperature data. In the simulation, both cooling and heating from beneath the tray were implemented using a stepwise function.

To quantify the accuracy of the model, the coefficient of determination (

) was calculated using the following formula:

where

are the experimental temperature measurements,

are the simulated values, and

is the average of the experimental data. An

value of 0.94 was achieved during the sublimation and drying stages, indicating excellent agreement. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the model accurately reproduces the temperature evolution, confirming its reliability in capturing the heat and mass transfer dynamics of the sublimation drying process.

2.2. Numerical Method

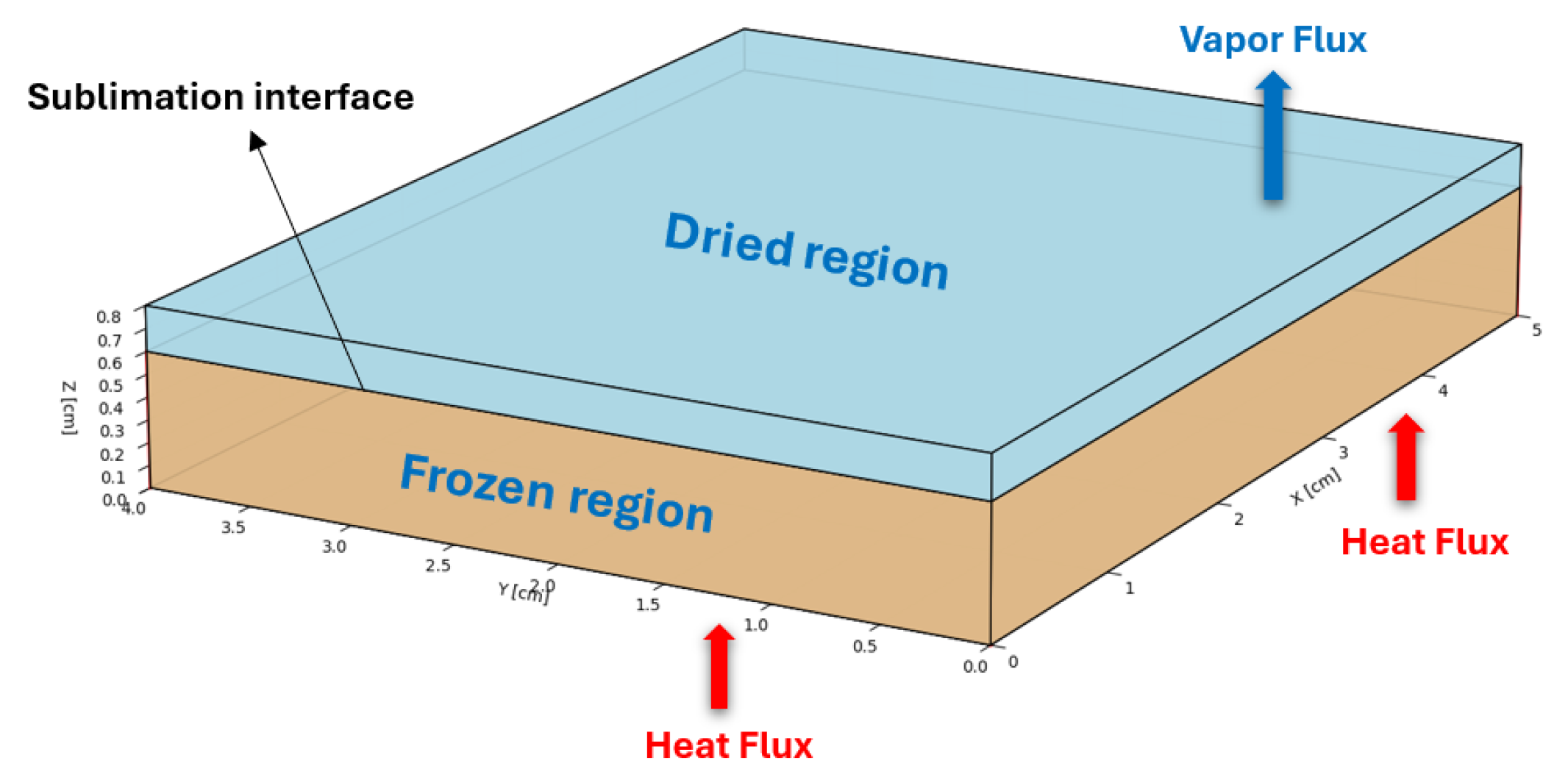

Owing to the symmetry of the trays and to reduce computational time, a computational domain of 5 × 4 × 0.8 cm is considered, as shown in

Figure 4. The drying process divides the computational space into two regions: an uppermost, desiccated layer and a lower, frozen layer. As sublimation occurs, the boundary between these zones gradually moves downward, causing the dry area to expand. The initial drying phase ends when this sublimation front reaches the bottom of the tray.

To simplify the modelling process, several assumptions were adopted based on prior studies [

22]. It is assumed that the solid matrix remains structurally stable throughout the process. A thin, idealised interface separates the frozen and dried regions. Vapour transport in the dried layer is described by Darcy’s law. Additionally, the porous structure is considered to remain intact as long as the temperature stays below the glass transition point.

2.2.1. Governing Equations

A computational model simulating the vacuum freeze-drying process for camel milk focuses on the interconnected nature of heat and mass movement within a porous material transforming its state. This model divides the system into two key areas: a frozen region made up of ice and the solid base material, and a dry region containing vapour and the solid base material. The transition of ice directly into vapour at their boundary causes the dry layer to expand while the frozen layer shrinks.

Heat Transfer. The temperature field

in the porous medium is governed by the energy conservation equation:

where

is the effective volumetric heat capacity,

is the effective thermal conductivity,

is the Darcy velocity of vapour, and

accounts for the latent heat absorption due to sublimation.

Vapour Transport Vapour mass transfer

u (m/s) is derived from Darcy’s law, expressed as:

where

is the permeability of the dried porous medium,

is the dynamic viscosity of water vapour, and

is the vapour pressure. The relationship between vapour pressure and vapour density is maintained via the ideal gas approximation.

The corresponding water vapour pressure

is calculated from the vapour density

using the ideal gas law:

Here, R is the universal gas constant and is the molecular weight of water vapour.

Sublimation Interface and Phase Change. The sublimation interface is tracked using a moving boundary approach based on the Clausius–Clapeyron relation:

where

is the sublimation temperature,

is the latent heat of sublimation,

is a reference pressure, and

is the vapour pressure at the interface.

The progression of the sublimation front is dictated by the principle of mass balance:

where

is the interface position and

is the normal vector pointing outward from the frozen domain. This equation ensures that vapour flux at the interface corresponds to the rate of ice removal due to sublimation.

2.2.2. Initial and Boundary Conditions

Initially, we assume the pressure in the dehydrated area mirrors the drying chamber’s pressure. Furthermore, we treat the sample as having a consistent temperature and composition throughout both the dried and frozen sections at the beginning of the sublimation drying procedure. Consequently, the starting parameters are:

where

represents the chamber pressure (in Pascals), and

denotes the initial temperature (in Kelvin) of the sample material at the start of the sublimation drying process.

The mass transfer (in terms of pressure and vapour flux) boundary conditions are: At the top surface:

Since water vapour is produced at the sublimation interface, the vapour flux boundary condition is established at this interface:

where

represents the position of the sublimation interface. In this study, sublimation occurs in both the x- and y-directions. The heat transfer boundary conditions:

Bottom boundary: convective heat flux from the shelf:

where

h is the heat transfer coefficient, and

is the shelf temperature.

Top and lateral boundaries: convective and radiative heat losses:

where

is the ambient heat transfer coefficient,

is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, and

is the emissivity of the surface.

The heat transfer boundary conditions in the sublimation interface:

where

is the sublimation interface temperature (in Kelvin).

2.3. Parameters and Thermal Physical Properties

The absence of trustworthy experimental results for camel milk’s thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat capacity necessitates estimations of these properties derived from the milk’s established composition.

There are studies in the literature that have reported the composition of camel milk. However, slight variations in constituent content have been observed among these studies, attributed to differences in region, feeding practices, and sampling times. In this work, we adopt the results of Konuspaeva [

23], as our samples originate from the same geographical area. The typical composition of camel milk is as follows in [

23]: water ∼87.47%, fat ∼3.50%, protein ∼3.21%, lactose ∼4.65%, and ash: ∼0.840%. Based on the given composition of mare’s milk, the following solid matrix properties have been estimated:

W/m·K (thermal conductivity), kg/m³ (density), J/kg·K (specific heat capacity).

To account for how thermophysical properties change across a space during sublimation, we use average properties calculated for each volume. These average properties are linked to the local ice saturation level, symbolized as S, which ranges from a state of complete freezing (S=1) to a state of complete dryness (S=0), with values in between signifying the area where sublimation is actively occurring.

The concept of effective volume-averaged density and heat capacity can be expressed effectively through the following definitions:

Similarly, the effective thermal conductivity, calculated using the parallel model of heat conduction in porous media, is given by:

By setting

, one obtains the thermophysical properties corresponding to the fully dried state of the product, as referenced in [

17].

Table 1 presents a summary of the parameters employed in the numerical simulation.

Numerical simulation A three-dimensional computational model, built within the COMSOL Multiphysics 6.3 platform, was employed to simulate the freeze-drying process. This model utilized the finite element method to tackle the intricate interplay of heat and mass transfer within a porous structure, specifically focusing on frozen milk undergoing vacuum freeze-drying. The simulation accurately represented heat conduction and vapour movement through the frozen milk matrix by integrating the "Heat Transfer in Porous Media" and Darcy’s Law modules.

Initially, the model presumed a completely frozen state, monitoring phase transitions through a Phase Change Interface. This feature relied on temperature-based criteria to pinpoint the boundary of sublimation. To accommodate the mesh distortion caused by volume shrinkage during ice sublimation, a Deformed Geometry component was integrated into the system. The underside experienced a defined heat input, mimicking the heat transfer from a shelf, with the sides and top edges insulated thermally. Simulations were conducted over a 24-hour period, employing a Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) method for time progression. For improved solver reliability, a distinct method was implemented, involving two separate stages: a pressure stage and a temperature stage. Each stage utilized PARDISO, a direct linear solver, to find solutions. Nonlinear acceleration was facilitated through Anderson acceleration, employing a damping factor of 0.9, with Jacobian revisions executed at each time interval. Termination criteria for the simulation were established through bespoke formulas, designed to halt the process when the sublimation boundary reached the base of the simulated region. Thermal and material characteristics were implemented using a homogenized porous media model, incorporating newly determined values for both dry camel milk and ice.

Mesh Independence Study. For precision and dependability, a structured mesh was created using triangular elements, spanning the base of the 3D model and extending vertically. To precisely capture thermal variations, a boundary layer mesh with four enhanced layers was incorporated near regions of significant thermal influence. A globally refined mesh setting, designated as "Finer," was employed, with an even finer setting, "Extra fine," applied to critical edges. A hyperelastic smoothing technique was utilized during deformation to prevent the need for remeshing.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of the Movement of the Sublimation Front

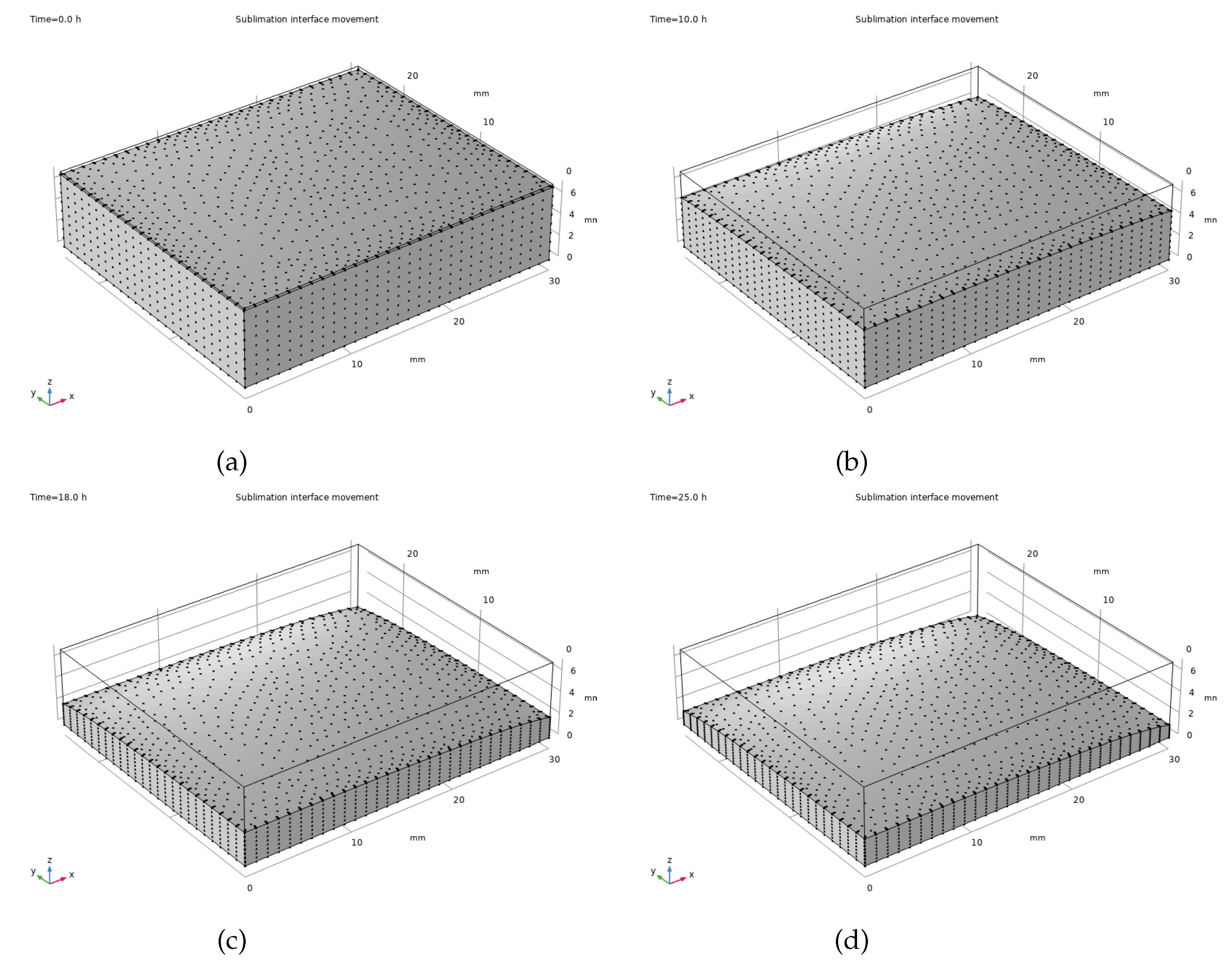

A defined group of factors was chosen to model heat and mass transfer processes within camel milk during the freeze-drying procedure. This baseline encompassed a 8 mm sample depth, a shelf temperature of -20 degrees Celsius, and a reduced chamber pressure of 105 pascals.

Standard conditions reveal a clear pattern of the sublimation front’s movement, as depicted in

Figure 5. The grey-shaded area, symbolizing the frozen portion, steadily diminishes, retreating towards the sample’s base while the dried layer grows.

In the early stages of drying, vapour readily escapes from the top, causing the dried area to expand quickly. But as drying progresses, the growing gap between the sublimation point and the surface slows down vapour movement, thus decelerating the movement of the dried interface. Eventually, the ice crystals left at the sample’s base become extremely difficult to sublimate, requiring substantial energy to eliminate completely.

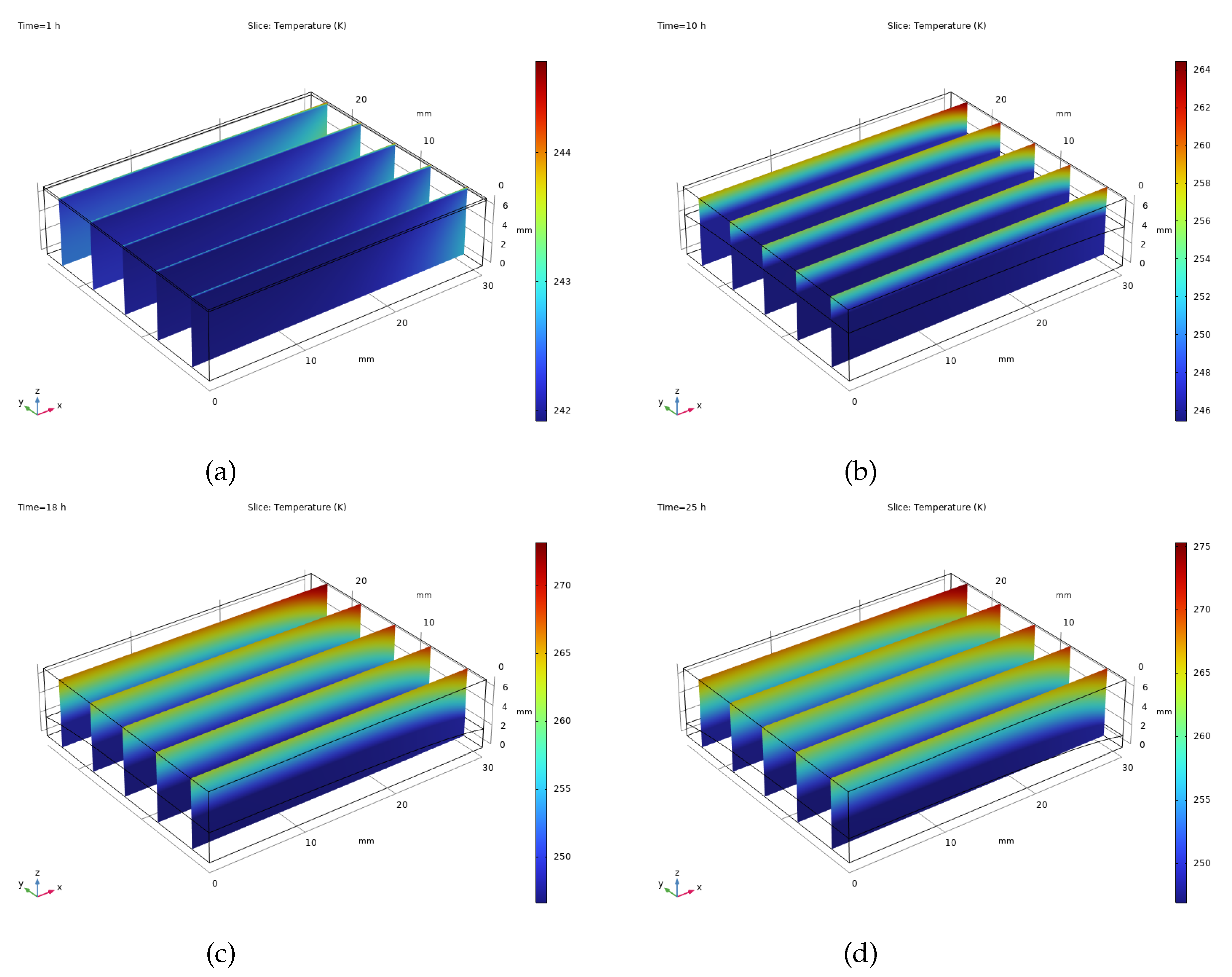

3.2. Heat and Mass Transfer Analysis

This research investigated temperature fluctuations and heat transfer patterns inside the drying chamber, revealing significant temperature differences during the initial drying stage through simulations. These disparities are a direct result of the high energy required for the transformation of ice into vapour.

Figure 6 illustrates how the temperature changes within camel milk samples during the freeze-drying process under typical circumstances. The heat emanating from the drying shelf penetrates the frozen portion of the sample, ultimately reaching the point where ice transitions directly into vapour, thus facilitating the drying.

The frozen and dried areas differ significantly in how they respond to heat. The frozen section, due to its higher thermal conductivity and ability to store heat, experiences more stable temperatures and heats up slowly. Conversely, the dry, porous layer readily absorbs radiant heat, leading to quicker, concentrated heating.

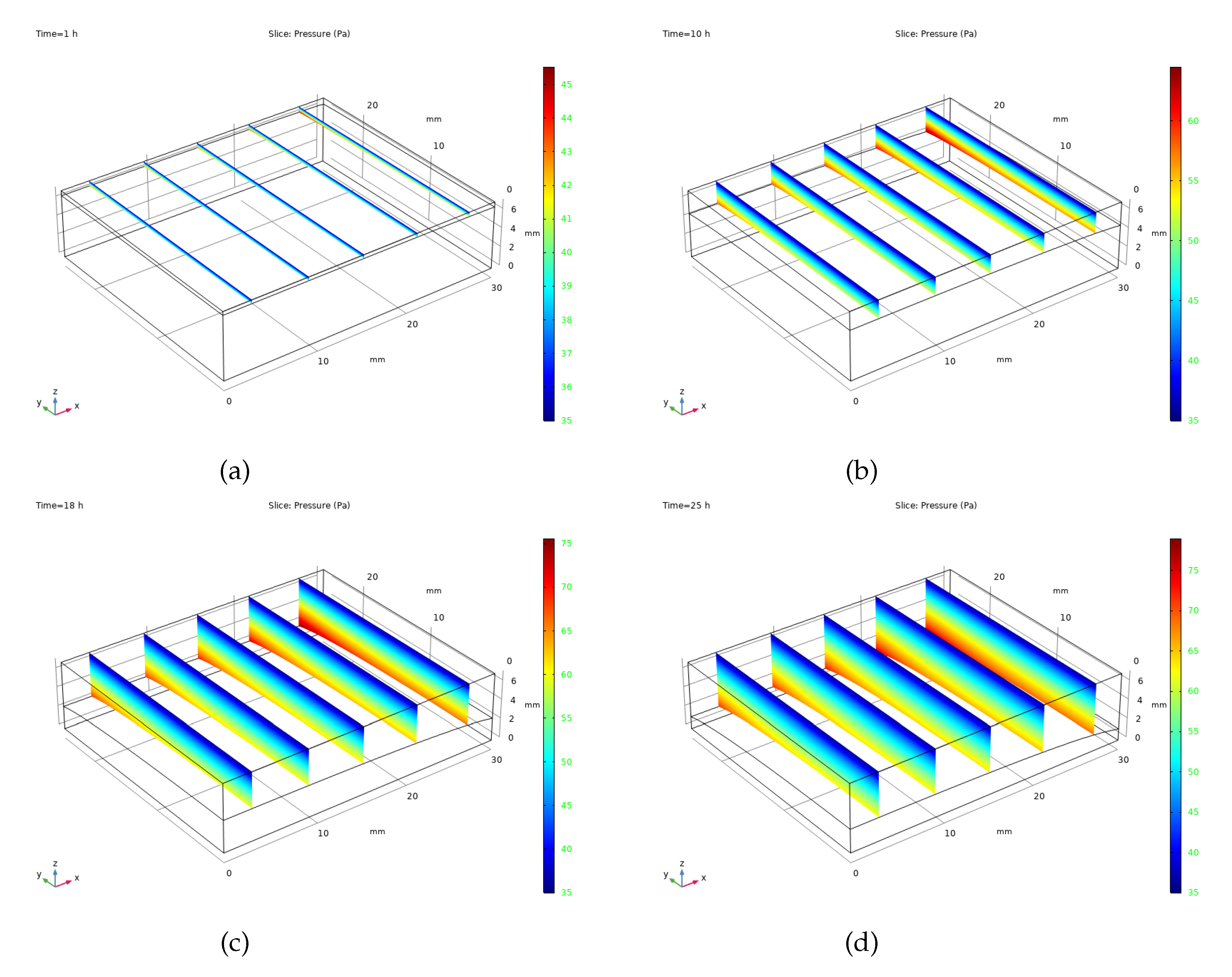

The vapour pressure patterns found in camel milk during standard freeze-drying are illustrated in

Figure 7. This computational analysis, which simplifies the process by disregarding mass movement within the frozen portion, concentrates solely on how pressure changes within the dried area.

3.3. Parametric Study

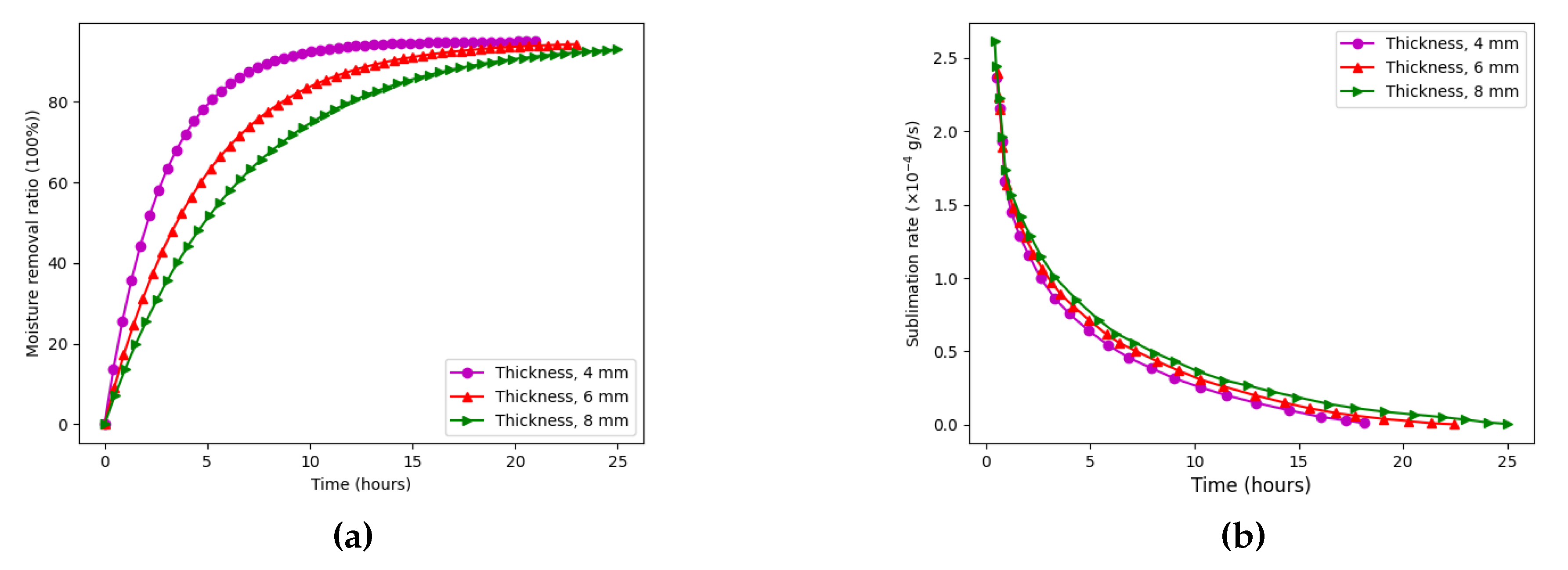

This subsection presents a comprehensive parametric analysis aimed at understanding how sample thickness and chamber pressure influence heat and mass transfer during the vacuum sublimation drying of camel milk.

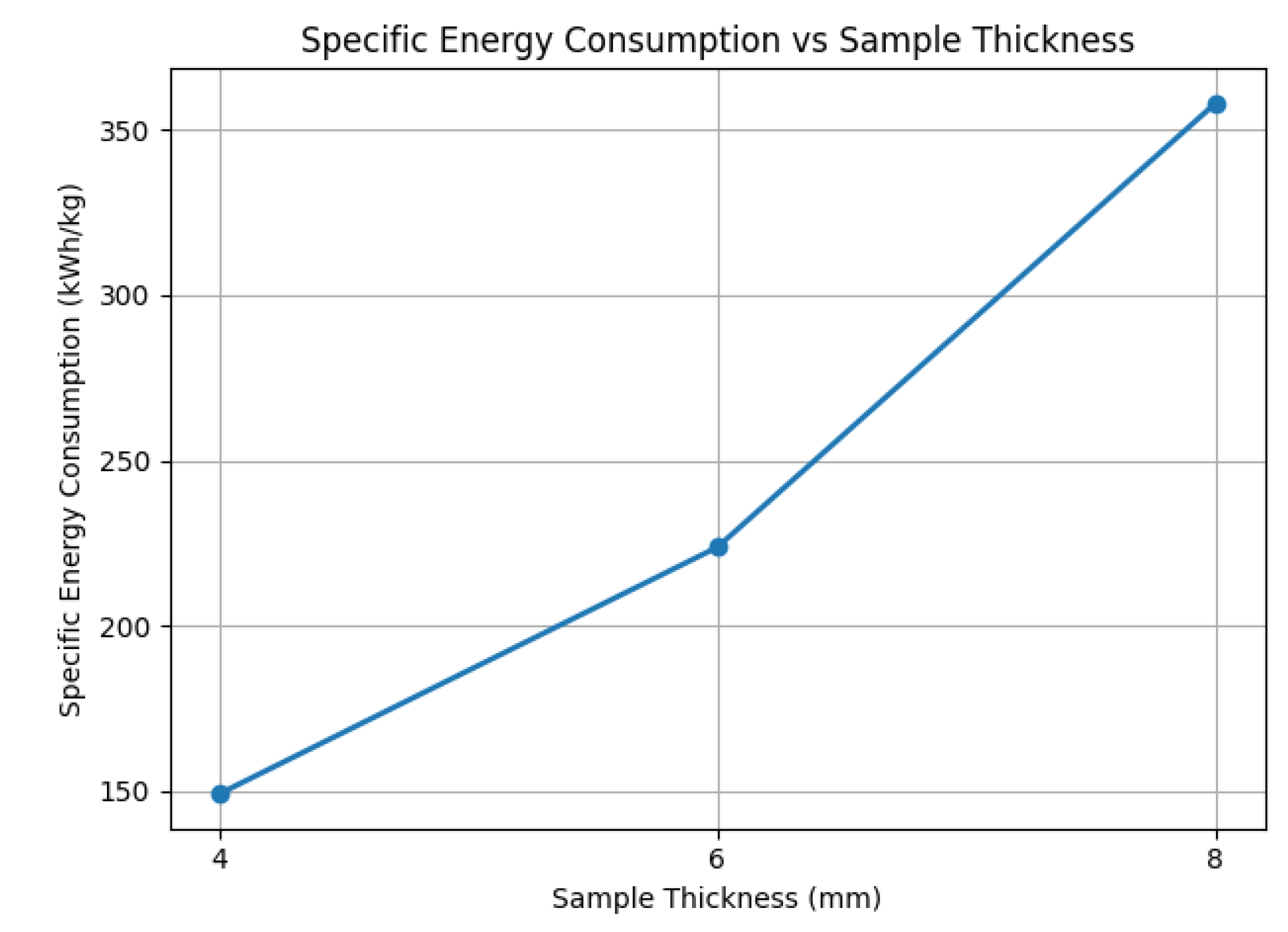

We first investigated the effect of sample thickness on moisture removal efficiency. Samples with thicknesses of 4 mm, 6 mm, and 8 mm were tested under constant conditions: a shelf temperature of C and a chamber pressure of 105 Pa.

Figure 8a illustrates the drying duration versus moisture removal ratio for the three sample thicknesses. A clear inverse relationship is observed: thinner samples dry significantly faster. Specifically, the 4 mm sample (pink line) reaches approximately 95% moisture removal in about 10 hours, while the 6 mm sample (red line) takes roughly 15 hours, and the 8 mm sample (green line) requires nearly 20 hours to achieve 90% removal. This is attributed to shorter vapor diffusion paths in thinner samples, facilitating faster moisture escape.

Figure 8b shows the corresponding sublimation rate. Interestingly, thicker samples exhibit higher peak sublimation rates, due to the greater initial water content and stronger vapor pressure gradients. However, this advantage is offset by prolonged drying times and higher energy demand, making thinner samples more desirable from an energy efficiency perspective.

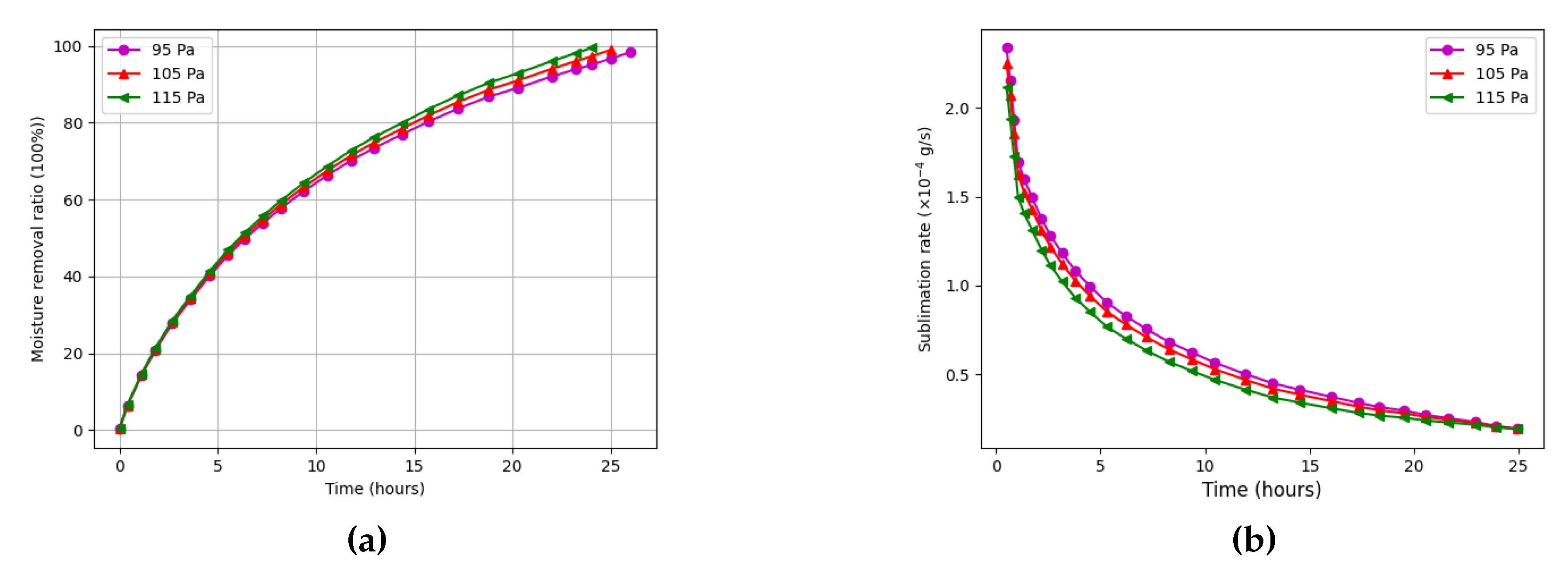

We also studied the impact of chamber pressure on the drying process.

Figure 9a shows that lowering the chamber pressure from 115 Pa to 95 Pa reduces the total drying time by approximately 30 minutes. This improvement is primarily due to enhanced vapor diffusion and a lower sublimation temperature at reduced pressure. However, it must be noted that operating the vacuum system at lower pressures incurs higher energy costs.

Figure 9b reveals that the sublimation rate initially increases with decreasing pressure, especially in the early stages. Yet, after approximately five hours, this advantage diminishes as the vapor pressure gradient stabilizes, and the sublimation rate levels off across all cases. This confirms that the benefit of pressure reduction is most significant during the early drying phase.

These findings indicate that both chamber pressure and sample thickness are critical control variables for improving drying efficiency. To meet international standards requiring final moisture content below 4%, it is advisable to maintain sample thicknesses below 8 mm. Furthermore, while reduced chamber pressures accelerate drying, their contribution to energy savings must be balanced against the increased operational cost of deeper vacuum levels.

From an industrial perspective, drying performance can be scaled by using larger trays or parallel tray systems within the chamber. However, the use of very thin layers in small trays may become energetically inefficient due to the higher relative overhead. Future work will focus on integrating predictive process control, energy monitoring, and optimization algorithms to enhance sustainability and reduce the carbon footprint of freeze-drying operations in dairy processing.